A Glossary of Grammatical Terms

This section is intended to refresh your memory of grammatical terms or to clear up difficulties you may have had in understanding them. Before you work through the grammar, you should have a reasonably clear idea what the parts of speech and parts of a sentence are. This is not for reasons of pedantry, but simply because it is easier to talk about grammar if we agree upon terms. Grammatical terminology is as necessary to the study of grammar as the names of automobile parts are to garagemen.

This list is not exhaustive, and the definitions do not pretend to be complete, or to settle points of interpretation that grammarians have been disputing for the past several hundred years. It is a working analysis rather than a scholarly investigation. The definitions given, however, represent most typical American usage, and should serve for basic use.

The Parts of Speech

English words can be divided into eight important groups: nouns, adjectives, articles, verbs, adverbs, pronouns, prepositions, and conjunctions. The boundaries between one group of words and another are sometimes vague and ill-felt in English, but a good dictionary, like the Webster Collegiate, can help you make decisions in questionable cases. Always bear in mind, however, that the way a word is used in a sentence may be just as important as the nature of the word itself in deciding what part of speech the word is.

Nouns. Nouns are the words for things of all sorts, whether these things are real objects that you can see, or ideas, or places, or qualities, or groups, or more abstract things. Examples of words that are nouns are cat, vase, door, shrub, wheat, university, mercy, intelligence, ocean, plumber, pleasure, society, army. If you are in doubt whether a given word is a noun, try putting the word “my,” or “this,” or “large” (or some other adjective) in front of it. If it makes sense in the sentence the chances are that the word in question is a noun. [All the words in italics in this paragraph are nouns.]

Adjectives. Adjectives are the words which delimit or give you specific information about the various nouns in a sentence. They tell you size, color, weight, pleasantness, and many other qualities. Such words as big, expensive, terrible, insipid, hot, delightful, ruddy, informative are all clear adjectives. If you are in any doubt whether a certain word is an adjective, add -er to it, or put the word “more” or “too” in front of it. If it makes good sense in the sentence, and does not end in -ly, the chances are that it is an adjective. (Pronoun-adjectives will be described under pronouns.) [The adjectives in the above sentences are in italics.]

Articles. There are only two kinds of articles in English, and they are easy to remember. The definite article is “the” and the indefinite article is “a” or “an.”

Verbs. Verbs are the words that tell what action, or condition, or relationship is going on. Such words as was, is, jumps, achieved, keeps, buys, sells, has finished, run, will have, may, should pay, indicates are all verb forms. Observe that a verb can be composed of more than one word, as will have and should pay, above; these are called compound verbs. As a rough guide for verbs, try adding -ed to the word you are wondering about, or taking off an -ed that is already there. If it makes sense, the chances are that it is a verb. (This does not always work, since the so-called strong or irregular verbs make forms by changing their middle vowels, like spring, sprang, sprung.) [Verbs in this paragraph are in italics.]

Adverbs. An adverb is a word that supplies additional information about a verb, an adjective, or another adverb. It usually indicates time, or manner, or place, or degree. It tells you how, or when, or where, or to what degree things are happening. Such words as now, then, there, not, anywhere, never, somehow, always, very, and most words ending in -ly are ordinarily adverbs. [Italicized words are adverbs.]

Pronouns. Pronouns are related to nouns, and take their place. (Some grammars and dictionaries group pronouns and nouns together as substantives.) They mention persons, or objects of any sort without actually giving their names.

There are several different kinds of pronouns. (1) Personal pronouns: by a grammatical convention I, we, me, mine, us, ours are called first person pronouns, since they refer to the speaker; you and yours are called second person pronouns, since they refer to the person addressed; and he, him, his, she, her, hers, they, them, theirs are called third person pronouns since they refer to the things or persons discussed. (2) Demonstrative pronouns: this, that, these, those. (3) Interrogative, or question, pronouns: who, whom, what, whose, which. (4) Relative pronouns, or pronouns which refer back to something already mentioned: who, whom, that, which. (5) Others: some, any, anyone, no one, other, whichever, none, etc.

Pronouns are difficult for us, since our categories are not as clear as in some other languages, and we use the same words for what foreign-language speakers see as different situations. First, our interrogative and relative pronouns overlap, and must be separated in translation. The easiest way is to observe whether a question is involved in the sentence. Examples: “Which [int.] do you like?” “The inn, which [rel.] was not far from Cadiz, had a restaurant.” “Who [int.] is there?” “I don’t know who [int.] was there.” “The porter who [rel.] took our bags was Number 2132.” This may seem to be a trivial difference to an English speaker, but in some languages it is very important.

Secondly, there is an overlap between pronouns and adjectives. In some cases the word “this,” for example, is a pronoun; in other cases it is an adjective. This also holds true for his, its, her, any, none, other, some, that, these, those, and many other words. Note whether the word in question stands alone or is associated with another word. Examples: “This [pronoun] is mine.” “This [adj.] taxi has no springs.” Watch out for the word “that,” which can be a pronoun or an adjective or a conjunction. And remember that “my,” “your,” “our,” and “their” are always adjectives. [All pronouns in this section are in italics.]

Prepositions. Prepositions are the little words that introduce phrases that tell about condition, time, place, manner, association, degree, and similar topics. Such words as with, in, beside, under, of, to, about, for, and upon are prepositions. In English prepositions and adverbs overlap, but, as you will see by checking in your dictionary, there are usually differences of meaning between the two uses. [Prepositions in this paragraph are designated by italics.]

Conjunctions. Conjunctions are joining-words. They enable you to link words or groups of words into larger units, and to build compound or complex sentences out of simple sentence units. Such words as and, but, although, or, unless, are typical conjunctions. Although most conjunctions are easy enough to identify, the word “that” should be watched closely to see that it is not a pronoun or an adjective. [Conjunctions italicized.]

Words about Verbs

Verbs are responsible for most of the terminology in this short grammar. The basic terms are:

Conjugation. In many languages verbs fall into natural groups, according to the way they make their forms. These groupings are called conjugations, and are an aid to learning grammatical structure. Though it may seem difficult at first to speak of First and Second Conjugations, these are simply short ways of saying that verbs belonging to these classes make their forms according to certain consistent rules, which you can memorize.

Infinitive. This is the basic form which most dictionaries give for verbs in most languages, and in most languages it serves as the basis for classifying verbs. In English (with a very few exceptions) it has no special form. To find the infinitive for any English verb, just fill in this sentence: “I like to......... (walk, run, jump, swim, carry, disappear, etc.).” The infinitive in English is usually preceded by the word “to.”

Tense. This is simply a formal way of saying “time.” In English we think of time as being broken into three great segments : past, present, and future. Our verbs are assigned forms to indicate this division, and are further subdivided for shades of meaning. We subdivide the present time into the present (I walk) and present progressive (I am walking); the past into the simple past (I walked), progressive past (I was walking), perfect or present perfect (I have walked), past perfect or pluperfect (I had walked); and future into simple future (I shall walk) and future progressive (I shall be walking). These are the most common English tenses.

Present Participles, Progressive Tenses. In English the present participle always ends in -ing. It can be used as a noun or an adjective in some situations, but its chief use is in forming the so-called progressive tenses. These are made by putting appropriate forms of the verb “to be” before a present participle: In “to walk” [an infinitive], for example, the present progressive would be: I am walking, you are walking, he is walking, etc.; past progressive, I was walking, you were walking, and so on. [Present participles are in italics.]

Past Participles, Perfect Tenses. The past participle in English is not formed as regularly as is the present participle. Sometimes it is constructed by adding -ed or -d to the present tense, as walked, jumped, looked, received; but there are many verbs where it is formed less regularly: seen, been, swum, chosen, brought. To find it, simply fill out the sentence “I have .........” putting in the verb form that your ear tells you is right for the particular verb. If you speak grammatically, you will have the past participle.

Past participles are sometimes used as adjectives: “Don’t cry over spilt milk.” Their most important use, however, is to form the system of verb tenses that are called the perfect tenses: present perfect (or perfect), past perfect (or pluperfect), etc. In English the present perfect tense is formed with the present tense of “to have” and the past participle of a verb: I have walked, you have run, he has begun, etc. The past perfect is formed, similarly, with the past tense of “to have” and the past participle: I had walked, you had run, he had begun. Most of the languages you are likely to study have similar systems of perfect tenses, though they may not be formed in exactly the same way as in English. [Past participles in italics.]

Preterit, Imperfect. Many languages have more than one verb tense for expressing an action that took place in the past. They may use a perfect tense (which we have just covered), or a preterit, or an imperfect. English, although you may never have thought about it, is one of these languages, for we can say “I have spoken to him” [present perfect], or “I spoke to him” [simple past], or “I was speaking to him” [past progressive]. These sentences do not mean exactly the same thing, although the differences are subtle, and are difficult to put into other words.

While usage differs a little from language to language, if a language has both a preterit and an imperfect, in general the preterit corresponds to the English simple past (I ran, I swam, I spoke), and the imperfect corresponds to the English past progressive (I was running, I was swimming, I was speaking). If you are curious to discover the mode of thought behind these different tenses, try looking at the situation in terms of background-action and point-action. One of the most important uses of the imperfect is to provide a background against which a single point-action can take place. For example, “When I was walking down the street [background, continued over a period of time, hence past progressive or imperfect], I stubbed my toe [an instant or point of time, hence a simple past or preterit].”

Auxiliary Verbs. Auxiliary verbs are special words that are used to help other verbs make their forms. In English, for example, we use forms of the verb to have to make our perfect tenses: I have seen, you had come, he has been, etc. We also use shall or will to make our future tenses: I shall pay, you will see, etc. French, German, Spanish, and Italian also make use of auxiliary verbs, but although the general concept is present, the use of auxiliaries differs very much from one language to another, and you must learn the practice for each language.

Reflexive. This term, which sounds more difficult than it really is, simply means that the verb flexes back upon the noun or pronoun that is its subject. In modern English the reflexive pronoun always has -self on its end, and we do not use the construction very frequently. In other languages, however, reflexive forms may be used more frequently, and in ways that do not seem very logical to an English speaker. Examples of English reflexive sentences: “He washes himself.” “He seated himself at the table.”

Passive. In some languages, like Latin, there is a strong feeling that an action or thing that is taking place can be expressed in two different ways. One can say, A does-something-to B, which is “active;” or B is-having-something-done-to-him by A, which is “passive.” We do not have a strong feeling for this classification of experience in English, but the following examples should indicate the difference between an active and a passive verb: Active: “John is building a house.” Passive: “A house is being built by John.” Active: “The steamer carried the cotton to England.” Passive: “The cotton was carried by the steamer to England.” Bear in mind that the formation of passive verbs and the situations where they can be used vary enormously from language to language. This is one situation where you usually cannot translate English word for word into another language and make sense.

Impersonal Verbs. In English there are some verbs which do not have an ordinary subject, and do not refer to persons. They are always used with the pronoun it, which does not refer to anything specifically, but simply serves to fill out the verb forms. Examples: It is snowing. It hailed last night. It seems to me that you are wrong. It has been raining. It won’t do.

Other languages, like German, have this same general concept, but impersonal verbs may differ quite a bit in form and frequency from one language to another.

Working Verbs. In some languages, English and German, for example, all verb forms can be classified into two broad groups: inactive forms and working forms. The inactive verb forms are the infinitive, the past participle, and the present participle. All other forms are working forms, whether they are solitary verbs or parts of compound verbs. All working verbs share this characteristic: they are modified to show person or time; inactive verbs are not changed. Examples: We have sixteen dollars. We left at four o’clock. We shall spend two hours there. The guide can pick us up tomorrow. You are being paged in the lobby. They are now crossing the square. I have not decided. [The first two examples are solitary verbs; the last five are working parts of compound verbs.]

In English this idea is not too important. In German, however, it is extremely important, since working verbs and inactive forms often go in different places in the sentence. [Working verbs are placed in italics.]

Words about Nouns

Declensions. In some languages nouns fall into natural groups according to the way they make their forms. These groupings are called declensions, and making the various forms for any noun, pronoun, or adjective is called declining it.

Declensions are simply an aid to learning grammatical structure. Although it may seem difficult to speak of First Declension, Second, Third, and Fourth, these are simply short ways of saying that nouns belonging to these classes make their forms according to certain consistent rules, which you can memorize. In English we do not have to worry about declensions, since almost all nouns make their possessive and plural in the same way. In other languages, however, declensions may be much more complex.

Predicate Nominatives, Predicate Complements, Copulas. The verb to be and its forms (am, are, is, was, were, have been, etc.) are sometimes called copulas or copulating verbs, since they couple together elements that are more or less equal. In some languages the words that follow a copula are treated differently than the words that follow other verbs.

In English, an independent adjective (without a noun) that follows a copula is called a predicate adjective or predicate complement, while the nouns or pronouns that follow copulas are called predicate nominatives. In classical English grammar these words are considered (on the model of Latin grammar) to be in the nominative (or subject) case, and therefore we say It is I or It is he. As you can understand, since only a handful of pronouns have a nominative form that is distinguishable from other forms, the English predicate nominative is a minor point.

In some other languages, however, the predicate nominative may be important, if predicate nouns and adjectives have case forms. In German, for example, there are more elaborate rules for predicate complements and predicate nominatives, and there are more copulas than in English.

Agreement. In some languages, where nouns or adjectives or articles are declined, or have gender endings, it is necessary that the adjective or article be in the same case or gender or number as the noun it goes with (modifies). This is called agreement.

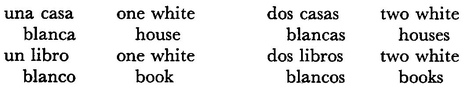

This may be illustrated from Spanish, where articles and adjectives have to agree with nouns in gender and number.

Here una is feminine singular and has the ending -a because it agrees with the feminine singular noun casa; blanca has the ending -a because it agrees with the feminine singular noun casa. blanco, on the other hand, and un, are masculine singular because libro is masculine singular.

Gender. Gender should not be confused with actual sex. In many languages nouns are arbitrarily assigned a gender (masculine or feminine, or masculine or feminine or neuter), and this need not correspond to sex. You simply have to learn the pattern of the language you are studying in order to become familiar with its use of gender.

Case. The idea of case is often very difficult for an English-speaker to grasp, since we do not use case very much. Perhaps the best way to understand how case works is to step behind words themselves, into the ideas which words express. If you look at a sentence like “Mr. Brown is paying the waiter,” you can see that three basic ideas are involved: Mr. Brown, the waiter, and the act of payment. The problem that every language has is to show how these ideas are to be related, or how words are to be interlocked to form sentences.

Surprisingly enough, there are only three ways of putting pointers on words to make your meaning clear, so that your listener knows who is doing what to whom. These ways are (i) word order (2) additional words (3) alteration of the word (which for nouns, pronouns, and adjectives is called case).

Word order, or the place of individual words in a sentence, is very important in English. For us, “Mr. Brown is paying the waiter” is entirely different in meaning from “The waiter is paying Mr. Brown.” This may seem so obvious that it need not be mentioned, but in some languages, like Latin, you can shift the positions of the words and come out with the same meaning for the sentence, apart from shifts of emphasis.

Adding other elements, to make meanings clear, is also commonly used in English. We have a whole range of words like to, from, with, in, out, of, and so on, which show relationships. Mr. Jones introduced Mr. Smith to the Captain is unambiguous because of the word to.

Altering the word itself is called case when it is done with nouns or pronouns or adjectives. Most of the time these alterations consist of endings that you place on the word or on its stem. Case endings in nouns thus correspond to the endings that you add to verbs to show time or the speaker. Examples of verb endings: I walk. He walks. We walked.

Case is not as important in English as it is in some languages, but we do use case in a few limited forms. We add an -’s to nouns to form a possessive; we add a similar -s to form the plural for most nouns; and we add (in spelling, though there is no sound change involved) an -’ to indicate a possessive plural. In pronouns, sometimes we add endings, as in the words who, whose, and whom. Sometimes we use different forms, as in I, mine, me; he, his, him; we, ours, and us.

When you use case, as you can see, you know much more about individual words than if you do not have case. When you see the word whom you automatically recognize that it cannot be the subject of a sentence, but must be the object of a verb or a preposition. When you see the word ship’s, you know that it means belonging to a ship or originating from a ship.

Many languages have a stronger case system than English. German, for example, has more cases than English (four, as compared to three maximum for English), and uses case in more situations than English does. What English expresses with prepositions (additional words) German either expresses with case alone or with prepositions and case.

Nominative, Genitive, Dative, and Accusative. If you assume that endings can be added to nouns or pronouns or adjectives to form cases, it is not too far a logical leap to see that certain forms or endings are always used in the same circumstances. A preposition, for example, may always be followed by the same ending; a direct object may always have a certain ending; or possession may always be indicated by the same ending. If you classify and tabulate endings and their uses, you will arrive at individual cases.

German happens to have four cases, which are called nominative, genitive, dative, and accusative. These names may seem difficult, but actually they are purely conventional. They are simply a short way of saying that in certain situations certain endings and stem changes are involved. It would be entirely as consistent to speak of the A case, the B case, the C case, or the D case.

Miscellaneous Terms

Comparative, Superlative. These two terms are used with adjectives and adverbs. They indicate the degree of strength within the meaning of the word. Faster, better, earlier, newer, more rapid, more detailed, more suitable are examples of the comparative in adjectives, while more rapidly, more recently, more suitably are comparatives for adverbs. In most cases, as you have seen, the comparative uses -er or “more” for an adjective, and “more” for an adverb. Superlatives are those forms which end in -est or have “most” prefixed before them for adjectives, and “most” prefixed for adverbs: most intelligent, earliest, most rapidly, most suitably.

Idiom. An idiom is an expression that is peculiar to a language, the meaning of which is not the same as the literal meaning of the individual words composing it. Idioms, as a rule, cannot be translated word by word into another language. Examples of English idioms: “Take it easy.” Don’t beat around the bush.” “It turned out to be a Dutch treat.” “Can you tell time in Spanish?”

The Parts of the Sentence

Subject, Predicate. In grammar every complete sentence contains two basic parts, the subject and the predicate. The subject, if we state the terms most simply, is the thing, person, or activity talked about. It can be a noun, a pronoun, or something that serves as a noun. A subject would include, in a typical case, a noun, the articles or adjectives which are associated with it, and perhaps phrases. Note that in complex sentences, each part may have its own subject. [The subjects of the sentences above have been italicized.]

The predicate talks about the subject. In a formal sentence the predicate includes a verb, its adverbs, predicate adjectives, phrases, and objects—whatever happens to be present. A predicate adjective is an adjective which happens to be in the predicate after a form of the verb to be. Example: “Apples are red.” [Predicates are in italics.]

In the following simple sentences subjects are in italics, predicates in italics and underlined. “Green apples are bad for your digestion.” “When I go to Spain, I always stop in Cadiz.” “The man with the handbag is travelling to Madrid.”

Direct and Indirect Objects. Some verbs (called transitive verbs) take direct and/or indirect objects in their predicates; other verbs (called intransitive verbs) do not take objects of any sort. In English, except for pronouns, objects do not have any special forms, but in languages which have case forms or more pronoun forms than English, objects can be troublesome.

The direct object is the person, thing, quality, or matter that the verb directs its action upon. It can be a pronoun, or a noun, perhaps accompanied by an article and/or adjectives. The direct object always directly follows its verb, except when there is also an indirect object present, which comes between the verb and the object. Prepositions do not go before direct objects. Examples: “The cook threw green onions into the stew.” “The border guards will want to see your passport tomorrow.” “Give it to me.” “Please give me a glass of red wine.” [We have placed direct objects in this paragraph in italics.]

The indirect object, as grammars will tell you, is the person or thing for or to whom the action is taking place. It can be a pronoun or a noun with or without article and adjectives. In most cases the words “to” or “for” can be inserted before it, if not already there. Examples: “Please tell me the time.” “I wrote her a letter from Barcelona.” “We sent Mr. Gonzalez ten pesos.” “We gave the most energetic guide a large tip.” [Indirect objects are in italics.]

Clauses: Independent, Dependent, Relative. Clauses are the largest components/that go to make up sentences./ Each clause, in classical grammar, is a combination of subject and predicate./ If a sentence has one subject and one predicate,/it is a one-clause sentence./ If it has two or more subjects and predicates, /it is a sentence of two or more clauses./

There are two kinds of clauses: independent (principal) and dependent (subordinate) clauses./ An independent clause can stand alone;/it can form a logical, complete sentence./ A dependent clause is a clause/that cannot stand alone;/it must have another clause with it to complete it./

A sentence containing a single clause is called a simple sentence./ A sentence with two or more clauses may be either a complex or a compound sentence./ A compound sentence contains two or more independent clauses,/and/these independent clauses are joined together with and or but./ A complex sentence is a sentence/which contains both independent and dependent clauses./

A relative clause is a clause/which begins with a relative pronoun: who, whom, that, which./ It is by definition a dependent clause,/ since it cannot stand by itself.

In English these terms are not very important except for rhetorical analysis,/since all clauses are treated very much the same in grammar and syntax. In some foreign languages like German, however, these concepts are important,/and they must be understood, /since all clauses are not treated alike. [Each clause in this section has been isolated by slashes./ Dependent clauses have been placed in italics;/independent clauses have not been marked./]