CHAPTER 8

Writing Skills

“True ease in writing comes from art, not chance, as those move easiest who have learned to dance.”

—Alexander Pope

Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the basic difficulties in writing clearly, simply, and correctly.

- Identity the different purposes of writing.

- Learn to plan written communication by paying special attention to the needs and expectations of prospective readers.

- Know the essential principles of effective written communication.

- Develop an effective tone in written communication.

- Use appropriate words and language for writing correctly and effectively.

COMMUNICATION AT WORK

Shalini is an MBA student. She is required to write a paper on decision-making. After jotting down her ideas on the decision-making process in a notebook, she settles down to write her paper. She stares blankly at the white sheet of paper in front of her for a couple of minutes. Then she picks up her pen and starts by writing at the heading on top of the sheet: ‘decision-making’.

Once again, she pauses, questioning the wording of the heading. Should it be decision-making or decision-taking? Do we make decisions or take decisions? To resolve the issue, she consults a dictionary. The white sheet continues to lie before her, blank. The dictionary tells her that making is correct, not taking.

She resumes writing. After writing a few sentences describing her upbringing by her father and how he had never allowed her to choose anything or do anything freely on her own, she slumps back in her chair. She stops writing and re-reads what she has written. She decides that she does not quite like the beginning.

After taking a short break, she begins to write afresh. The initial lines are struck off the white sheet of paper. She wonders how to begin correctly. At that moment, her elder brother enters the room. He tells her that the only way to write is for her to first put down whatever thoughts she has. Only after writing down her ideas, should she re-read, revise, and polish the language. He explains to Shalini that every creative act, whether of writing or speaking, has a painful beginning.

THE ART OF WRITING

Writing is a mode of communicating a message for a specific purpose. It reveals one’s ability to think clearly and to use language effectively. A manager is responsible for a variety of written communications such as replies to clients, enquires, memos recording agreements, proposals for contracts, formal or informal reports to initiate action, and so on. A manager should be able to convey information, ideas, instructions, decisions, and welfare proposals in written form, in keeping with the level of the people who receive and read them. However, a manager’s objective in writing a particular document is only met when readers understand exactly what is intended to be communicated to them. A manager, therefore, should be able to write down his or her thoughts simply and concisely.

THE SKILLS REQUIRED IN WRITTEN COMMUNICATION

Effective writing does not come by chance. It does not just happen. There is a set of skills required to write simply, clearly, accurately, and concisely.

Writing skills are as essential as the other knowledge and skills that form an executive’s professional qualifications and requirements. The skills required for business writing are essentially the same as those required for general written communication. Business writers should carefully check the grammar, punctuation, and spellings; ensure that sentences and paragraphs are structured logically; and follow the principles of sound organization—clarity, simplicity, and directness.

1

Understand the basic difficulties in writing clearly, simply, and correctly.

THE PURPOSE OF WRITING

The first task for writing effectively is to identify the purpose of the communication. There are mainly two goals of communication in business situations—to inform and to persuade.

2

Identity the different purposes of writing.

Writing to inform

When the writer seeks to provide and explain information, the writing is called informative writing. It is also called expository writing because it expounds on or expresses ideas and facts. The focus of informative writing is the subject or the matter under discussion. Informative writing is found in accounts of facts, scientific data, statistics, and technical and business reports.

Informative writing presents information, not opinions. Its purpose is to educate and not persuade. It is written with maximum objectivity.

Informative writing presents information not opinions. Its purpose is to educate and not persuade. It is, therefore, written with maximum objectivity. For example, consider the passage in Communication Snapshot 8.1.

Exhibit 8.1 presents a list of questions that must be answered in the affirmative to determine if a piece of writing is effective.

Writing to Persuade

Persuasive writing aims at convincing the reader about a matter that is debatable; it expresses opinion rather than facts. This writing is also called argumentative, as it supports and argues for a certain viewpoint or position. The matter at hand generally has two or more sides to it. The writer seeks to influence and convince the reader to accept the position he or she has put forth.

Communication Snapshot 8.1

Informatory Writing

The passage in Exhibit 8A is a piece of informative or expository writing. It successfully transmits a message about ants to readers. In the passage, the writer’s opening sentence expresses the main idea. The subsequent sentences give information that supports the main idea, namely unusual facts about the social lives of ants.

As indicated, the purpose of the writer is to inform a reader objectively, with little bias. The information is logically arranged and clearly written.

Exhibit 8A

Ants

Ants have strange social lives. Like mediaeval feudal lords, some ants keep slaves to do their work. They attack other ants’ nests and capture them. The victorious ants bring back the defeated groups of ants to their own nests and force them to work as slaves. Surprisingly, ants do not live alone in their nests. Hundreds of other small creatures, like beetles and crickets, dwell with the ants in their houses as inmates. Some of these small creatures do useful work for the ants. They serve the ants by keeping the nests clean and performing other duties. However, others seem to live without doing anything in return. Why the ants allow them to stay in their nests is a puzzling question. Is it just benevolence or is it the feudal spirit of keeping a large retinue of servants?

Exhibit 8.1

Informative Writing: A Checklist

- Does the write-up focus on the subject under discussion?

- Does it primarily inform rather than persuade the reader?

- Does it offer complete and precise information?

- Can the information be proven?

- Does it present information logically and clearly?

- Does it flow smoothly?

Persuasive writing focuses on the reader. The writer attempts to change the reader’s thinking and bring it closer to his or her own way of thinking. Persuasive writing is found in opinion essays, editorials, letters to editors, business and research proposals, religious books, reviews, or literature belonging to a certain political party.

Persuasive writing is found in opinion essays, editorials, letters to editors, business and research proposals, religious books, reviews, or literature belonging to a certain political party.

Persuasive writing does more than just state an opinion—that is not enough. The opinion must be convincing. There must be supporting evidence or facts to back the writer’s opinion or point of view. Moreover, the writer’s point of view should be well argued, meaning his or her reasoning should be logical and clearly arranged. Let us consider the example of ‘Alternative Sources of Fuel’ shown in Communication Snapshot 8.2.

Exhibit 8.2 presents a list of questions that must be answered in the affirmative for a passage to be considered persuasive.

Communication Snapshot 8.2

Persuasive Writing

The case built in Exhibit 8B for considering alternative sources of fuel is well argued. The final paragraph clinches the argument for finding substitutes for fuel oil by convincing readers that, although it is not easy to solve the energy problem, the real need is ‘to find substitutes for fuel oil’ and ‘replacement energy forms are available to fill that need’.

Exhibit 8B

Alternative Sources of Fuel

Faced with today’s high energy costs and tremendous consumer demand, we need to find alternative energy forms. During the past five years, consumers have tried conservation as a means of defence against high fuel (petrol and home-heating) prices. They purchased smaller, more fuel-efficient cars and insulated their homes with storm windows and doors. While these conservation measures improved the efficiency of oil consumption, they had no effect on continually increasing oil prices. Since conservation alone is not the answer, what alternatives are available now?

One readily accessible substitute energy form is solar energy, produced by the sun. Solar collectors—made of insulation, serpentine tubing filled with water, and glass—absorb heat from the sun and distribute it to radiators or baseboard heaters. Hot water for bathing is available through this same process.

Gasohol is another alternate fuel. Gasohol is a mixture of 10 per cent alcohol and 90 per cent gasoline. Cars travel more efficiently on this fuel due to its high octane content. In fact, Henry Ford designed the Ford Model-T to run on pure alcohol. Gasohol should be carefully considered as an alternate fuel, because the alcohol needed is easily derived from just about anything, such as corn, wood, or organic garbage.

We could also look to another natural resource: the wind. Some experimentation is being conducted in the Midwest using windmills to generate electricity. As a matter of fact, at least one major store sells windmills across the country.

Coal and wood should also be considered as substitute fuels. People heated their homes with wood stoves and coal furnaces long before oil was available as a home-heating fuel. Although there are no easy or comfortable ways to get around our energy problems, comfort has to be placed after our real need, which is to find substitutes for fuel oil. Replacement energy forms are available to fill that need.

Exhibit 8.2

Persuasive Writing: A Checklist

- Does it focus on the reader?

- Does it basically seek to convince rather than inform?

- Does it support its argument by providing facts or valid reasons?

- Does it follow a logical arrangement of thought and reasoning?

- Does it evoke the intended response from the reader?

CLARITY IN WRITING

An important requirement for effective writing is to recognize the needs, expectations, fears, and attitudes of the audience or receiver and the reader of the written message. Written communication is one-way—from the sender to the receiver. The receiver cannot immediately clarify doubts or confusion if the message is unclear. Therefore, communicating clearly is especially important when it comes to written communication.

3

Learn to plan written communication by paying special attention to the needs and expectations of prospective readers.

A manager works out schemes and projects, a scientist or engineer solves a technical problem. As the ‘doer’, he or she is clear about what is in his or her mind. But the moment someone takes up a pen and starts writing to communicate ideas, he or she must keep in mind that the structure of his or her thoughts has to follow the structure of language, that is, the format of sentences, paragraphs, and the composition as a whole. Writers must follow the principles of unity and coherence that bind words into sentences, sentences into units or paragraphs, and paragraphs into essays (the full composition). When this transformation of thought into language is not effected under the guiding principles of language, the muddy clutter hides the meaning and makes it difficult to understand the writer’s thoughts.

When the transformation of thought into language is not effected under the guiding principles of language, the muddy clutter hides the meaning and makes it difficult to understand the writer’s thoughts.

Although the letter has remained the most common means of written communication for a very long period, its importance is frequently overlooked. Authors often dictate or write down a few scattered sentences in the hope that the reader will get the message. However, the message may be buried under a mountain of unnecessary words, or an unnatural style may conceal the writer’s true intentions. Instead of letting business letters be friendly, interesting, and persuasive, such writing makes them overly formal and dull.

Although the letter, for a long time, remained the most common means of written communication, its importance is frequently overlooked. Authors often dictate or write down a few scattered sentences in the hope that the reader will get the message.

Exhibit 8.3 shows a well-written sample letter that has the flavour of easy conversation. Notice the use of everyday words such as ‘hope’, ‘remember’, ‘regret’, ‘send’, ‘says’, ‘provide’, ‘charge’, ‘believe’, ‘make’, and so on that give the letter the simplicity of the spoken word.

The written word often gets cluttered with complex construction of sentences. Communication Snapshot 8.3 presents an example of a paragraph whose meaning is lost because of complex sentences. It also shows how this paragraph can be rewritten to bring clarity.

Exhibit 8.3

A Well-written Sample Letter

12 August, 2009

The Service Manager

Customer Satisfaction Division

Samsung India Limited

Nehru Place

New Delhi

Dear Sir,

I hope you remember our discussion last Monday about the servicing of the washing machine supplied to us three months ago. I regret to say the machine is no longer working. Please send a service engineer as soon as possible to repair it.

The product warranty says that you provide spare parts and materials free, but charge for the engineer’s labour. This sounds unfair. I believe the machine’s failure is caused by a manufacturing defect. Initially, it made a lot of noise, and, later, it stopped operating entirely. As it is wholly the company’s responsibility to rectify the defect, I hope you will not make us pay for the labour component of its repair.

Thanking you,

Yours faithfully,

Mrs Roli Chaturvedi

Communication Snapshot 8.3

Examples of Clear and Unclear Writing

After reading Exhibit 8C, the only facts that a reader can be sure about are that the owners of the land were contacted on July 25 and that the president will be returning on August 25. The important information about the possible sale of the block is completely concealed by the excess of words. It is likely that the writer wanted to say something along the lines of Exhibit 8D.

Exhibit 8C

The Original Paragraph

When the owners were contacted on July 25, the assistant manager, Mr Rathi, informed the chief engineer that they were considering ordering advertising Block 25 for sale. He, however, expressed his inability to make a firm decision by requesting this company to confirm their intentions with regard to buying the land within one month, when Mr Jain, the president of the company, will have come back from a business tour. ‘This will be August 25’.

Exhibit 8D

The Revised Paragraph

The chief engineer contacted the owner on July 25 to enquire if Block 25 was on sale. He was informed by the assistant manager, Mr Rathi, that the company was thinking of selling the block. He was further told that decision would not be made until the president, Mr Jain, returned from a business tour on August 25. Mr Rathi asked the chief engineer to submit a written proposal for sale.

The purpose of business writing is to achieve the understanding and reaction needed in the quickest and most economical way. To do this one must follow the principles and structure of effective writing.

PRINCIPLES OF EFFECTIVE WRITING

Effective written communication is achieved by following the principles of (1) accuracy, (2) brevity and (3) clarity, in addition to others. As we have already discussed clarity, let us focus on the other important principles of effective writing here.

4

Know the essential principles of effective written communication.

Accuracy

To achieve accuracy, the writer should check and double-check:

- All facts and figures

- The choice of words

- The language and tone

For example, whether a communication is formal or informal, one should always write ‘between you and me’, not ‘between you and I’. In this case, the choice is simple as it is guided by the objective rules of grammar. But in other cases, word choice may not be as clearly indicated. The correct choice of words is determined by the appropriateness of the word for the subject, audience, and purpose of a particular piece of writing.

A message should be communicated correctly in terms of grammar, punctuation, and spelling. Of course, it is not always easy to be accurate in expression; however, some obvious pitfalls can be avoided by being alert to the following:

A message should be communicated correctly in terms of grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

- Follow the rules of grammar.

- Pay attention to punctuation marks.

- Check words for spelling and usage.

Only a few samples are given here to indicate the danger of overlooking the technical aspects of writing. Detailed study of the grammatical rules will be discussed in Appendix 1.

To avoid incorrect usage, it is important to check the suitability of the words used. Exhibit 8.4 presents a list of words that are often confused or used incorrectly.

Exhibit 8.4

Some Commonly Confused Words

Accept, Except: Accept, a verb, means to agree to something, to believe, or to receive. Except means ‘not including’ or ‘other than’.

Advice, Advise: Advice is a noun, and advise is a verb.

Affect, Effect: Most frequently, affect, which means to influence, is used as a verb, and effect, which means a result is used as a noun.

Ain’t: This is a non-standard way of saying ‘am not’, ‘has not’, ‘have not’, and so on.

All Right, Alright: The phrase all right has two words, not one. Alright is an incorrect form.

All Together, Altogether: All together means in a group, and altogether means entirely or totally.

Alot, A lot: Alot is an incorrect form of a lot.

Among, Between: Among is used to refer to three or more nouns and between is used for two nouns.

Amount, Number: Amount is used for things or ideas that are general or abstract and cannot be counted. Number is used for things that can be counted.

Anyone, Any One: Anyone means any person at all. Any one refers to a specific person or things in a group.

As, As If, Like: As is used in a comparison when there is an equality intended; as if is used when a supposed situation is there; and like is used when similarity is intended.

Assure, Ensure, Insure: Assure means to declare or promise; ensure means to make safe or certain; and insure means to protect with a contract of insurance.

Awful, Awfully: Awful is an adjective meaning ‘extremely unpleasant’. Awfully is an adverb used in informal writing to say ‘very’. It should be avoided in formal writing.

Beside, Besides: Beside is a preposition meaning ‘at the side of’, ‘compared with’, or ‘having nothing to do with’. Besides is a preposition meaning ‘in addition to’ or ‘other than’.

Breath, Breathe: Breath is a noun, and breathe is a verb.

Choose, Chose: Choose is the present tense of the verb, and chose is the past tense.

Compared to, Compared with: Use compared to to point out similarities between dissimilar items. Use compared with to show similarities and differences between similar items.

Data: This is the plural form of datum. In informal usage, data is used as a singular noun.

Different from, Different than: Different from is always correct, but some writers also use different than when a clause following this phrase. (For example, ‘This book is different from the others’. and ‘That is a different outcome than they expected’.)

Farther, Further: While some writers use these words interchangeably, dictionary definitions differentiate between them. Farther is used when actual distance is involved, and further is used to mean ‘to a greater extent’ or ‘more’.

Fewer, Less: Fewer is used for things that are countable (for example: fewer trains, fewer trees, fewer students). Less is used for ideas, abstractions, or things that are thought of collectively, not separately (for example: less gain, less furniture), and things that are measured by amount not number (for example: less tea, less money).

Good, Well: Good is an adjective and therefore describes only nouns. Well is an adverb and describes adjectives, other adverbs, and verbs.

Got, Have: Got is the past tense of ‘get’ and should not be used in place of have. Similarly, ‘got to’ should not be used as a substitute for ‘must’. ‘Have got to’ is an informal substitute for must.

Imply, Infer: Sometimes these two words are used interchangeably. However, imply means to suggest without stating directly. Infer means to reach an opinion from facts or reasoning.

Its, It’s: Its is a personal pronoun in the possessive case. It’s is a contraction for ‘it is’.

Kind, Sort: These two forms are singular and should be used with the words ‘this’ or ‘that’. Their plurals, kinds and sorts should be used with the words ‘these’ or ‘those’.

Lay, Lie: Lay is a verb that needs an object and should not be used in place of lie, a verb that takes no direct object.

OK, Okay: These can be used interchangeably in informal writing, but should not be used in formal or academic writing.

Such: This is an often overused word in place of ‘very’ or ‘extremely’. It should be avoided.

Sure: The use of sure as an adverb is informal. In formal writing, the adverb ‘surely’ is used.

That, Which: Use that for essential clauses and which for non-essential clauses.

Their, There, They’re: Their is a possessive pronoun; there means ‘in’, ‘at’, or ‘at that place’; they’re is the contraction for ‘they are’.

Theirself, Theirselves: These are incorrect forms that are sometimes used in place of ‘themselves’.

Use to: This is incorrect; ‘used to’ should be used instead.

Who, Whom: Who is used for the subject case; whom is used for the object case.

Who’s, Whose: Who’s is a contraction for ‘who is’; whose is a possessive pronoun.

Your, You’re: Your is a possessive pronoun; you’re is a contraction for ‘you are’. (Your feet are cold. You’re a great writer.)

Yours, Your’s: Yours is the correct possessive form; your’s is an incorrect version of ‘yours’.

Brevity

Brevity lies in saying only what needs to be said and leaving out unnecessary words or details. Being brief does not mean saying less that what the occasion demands. Brevity is not to be achieved at the cost of clarity. Nor is brevity to be gained by sacrificing proper English.

To achieve brevity, avoid wordiness. This can be done in the following ways:

Brevity lies in saying only what needs to be said and leaving out unnecessary words or details.

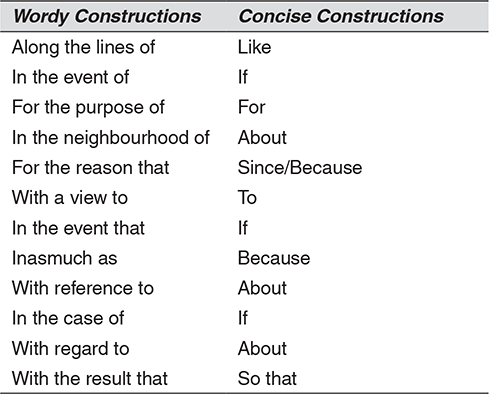

- Do not use four or six words when one or two will do. It is not necessary to qualify one word with another word that basically means the same thing. For instance, in the phrase, ‘worldwide recognition by all’, it would suffice to say just ‘worldwide’ or ‘by all’. Exhibit 8.5 lists phrases that are examples of wordiness; they can each be reduced to one or two words.

Exhibit 8.5

Examples of Wordy and Concise Constructions

- Wordiness can also be avoided by changing long clauses into phrases. Here are a few examples:

Wordy: The vast majority of farmers in India are poor in a greater or lesser degree. Concise: Most Indian farmers are quite poor. Wordy: The special difficulty in my case arises in relation to the fact that I live so far from my institute. Concise: I am specially handicapped by living so far from my institute. Wordy: In this connection, it is not without interest to observe that, in the case of many states, no serious measures have been taken with a view to putting the recommendations of the HRD minister into practice. Concise: Most states have done little to implement the HRD minister’s recommendations. Wordy: Mr Singh, who was a newcomer to the city mentioned earlier in this report, proved to be a very able administrator. Concise: Mr Singh, a newcomer to the above-mentioned city, proved to be a very able administrator. (Here a clause has been reduced to a phrase and a phrase reduced to a single word.) Wordy: She is so honest that she will not tell a lie. Concise: She is too honest to tell a lie. Wordy: The wind is so cold that we cannot go out at present. Concise: The wind is too cold for us to go out at present. - Drop ‘which’ and ‘that’ clauses when possible. For example:

Wordy: I need cards that are of formal type. Concise: I need formal cards. Wordy: She received a shirt that was torn. Concise: She received a torn shirt. Wordy: She cleared the debts that her husband had taken on. Concise: She cleared her husband’s debts. Wordy: I am sure that I shall be able to help you. Concise: I am sure I can help you. - Do not overuse the passive voice. For example:

Wordy: Technology can be used by children also. Concise: Children also can use technology. Wordy: The post of Prime Minister of India is held by Dr Manmohan Singh. Concise: Dr Manmohan Singh holds the Prime Ministership of India. Wordy: Many great lands had been seen by Ulysses. Concise: Ulysses saw many great lands.

Communication Snapshot 8.4

Rewriting a Letter

Exhibit 8E

A Wordy Letter

We are in receipt of your letter dated 25 June and have pleasure in informing you that the order you have placed with us will receive our best and immediate attention and that the fifteen ACs you require will be provided to you as soon as we are able to arrange for and supply them to you.

We are, however, very sorry to say that our stock of these ACs is, at this moment of time, quite short. Owing to the extremely hot summer and the consequent increase in demand, we have been informed by the manufacturers that they are not likely to be in a position to supply us with further stock for another three weeks or so.

We are extremely sorry not to be in a position to satisfy your requirements immediately, but we wish to assure you that we will always try to do everything we possibly can to see that your order for fifteen ACs is met as soon as possible. If you are not able to obtain the ACs you need from elsewhere, or if you are able to wait for them until the end of the next of month, you are requested to inform us in a timely manner.

Once again expressing our sincerest regret at our inability to fulfil your esteemed order on this occasion with our usual promptness and trusting you will continue to favour us in the future,

Yours truly,

![]()

Prem Ahuja

Exhibit 8F

The Rewritten Letter

Dear Sir,

We thank you for your order of 25th June, but regret that due to the exceptional demand for ACs thanks to the prolonged hot spell, we are currently out of stock of the brand you ordered. The manufacturers, however, have promised us further supply by the end of this month, and if you could wait until then, we would ensure the prompt delivery of the fifteen ACs you require.

We are sorry that we cannot meet your present order immediately.

Yours truly,

![]()

Prem Ahuja

Communication Snapshot 8.4 illustrates a wordy and tedious business letter and one way to make it more concise.

The letter in Exhibit 8E can be rewritten in a brief and concise form, as shown in Exhibit 8F.

Language, Tone, and Level of Formality

To ensure that a piece of writing is understood by the target audience, it is essential to use language that is commonly understood. The tone used should also reflect the appropriate level of formality for a particular context.

5

Develop an effective tone in written communication.

Standard English

‘Standard English’ includes the most commonly used and accepted words. It is considered ‘standard’ because it follows the norms laid down by the rules of grammar, sentence construction, punctuation, spelling, paragraph construction, and so on. It is the language used in formal writing, such as books, magazines, newspapers, letters, memos, reports, and other forms of academic writing. For example, ain’t, a contraction of ‘I am not’, ‘is not’ or ‘has not’, is usually considered unacceptable in written (and also spoken) English. It can, however, appear as slang or in informal writing.

Tone

After determining the purpose and audience of a piece of writing, one has to then choose the appropriate tone in terms of formality. Tone refers to feelings created by words used to communicate a message. The tone of a piece of writing basically depends on the relationship between the writer and those who receive the message. As discussed earlier, communications in an organization can be classified as upward, downward, or horizontal. It requires skill and competence on the part of the writer to use the appropriate tone based on the status of the reader or receiver. It is obvious that something written for one’s superiors will have a formal tone, whereas something written for one’s peers will be more informal.

Tone refers to feelings created by words used to communicate a message.

According to Muriel Harris, ‘The level of formality is the tone in writing and reflects the attitude of the writer toward the subject and audience’.1

The tone can be:

- Informal

- Semi-formal

- Strictly formal

Informal Tone

A writer uses an informal tone for social or personal communication and for informal writing. Deviations from standard English change the tone of writing from formal to informal or very formal. The informal tone includes the use of slang, colloquialisms, and regional words. The writer may also include contractions and incomplete sentences. An example of informal tone is: ‘The guy was damn annoyed because he couldn’t get a hang of the mumbo-jumbo’.

6

Use appropriate words and language for writing correctly and effectively.

- Colloquialisms: Colloquialisms are casual words or phrases used in informal writing. Some examples of colloquialisms are ‘guy’ for a person; ‘ain’t’ for am not, is not, or are not; ‘kids’ for children; ‘hubby’ for husband; ‘flunk’ instead of fail; ‘wannnabe’ for an avid fan who tries to emulate the person he or she admires; ‘whopping’ for huge (for example, ‘a whopping success’).

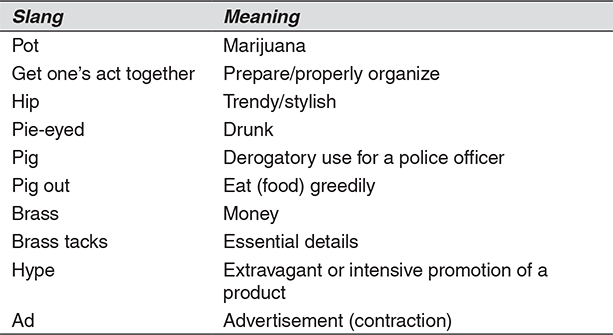

- Slang: Slang consists of informal words, phrases, or meanings that are not regarded as standard and are often used by a specific profession, class, and so on. Slang words, like colloquial words, are non-conventional. They are used in some special sense, but they exclude jargon and dialect-specific words. If a slang word acquires greater respectability, it moves into the category of colloquialism and may even reach the acceptability of standard English. For instance, ‘whodunit’ is a colloquial word that appears in the critical writing of Northrop Frye, an eminent contemporary critic. It is gradually acquiring acceptability and is used to refer to modern murder mysteries. Some slang words and phrases are shown in Exhibit 8.6.

Slang consists of informal words, phrases, or meanings that are not regarded as standard and are often used by a specific profession, class, and so on.

- Regional words: Regional words, as the term suggests, are used primarily in a particular geographic area. The richness of English lies in its openness to words from other areas and countries. Words such as ‘porch’, ‘verandah’, ‘portico’, ‘gherao’, ‘hartal’, ‘bazaar’, ‘bag’, ‘sack’, ‘tote’, or ‘phone’ form part of spoken and written English, sometimes as standard usage.

The richness of English lies in its openness to words from other areas and countries.

Words such as hype and ad are gaining wider acceptability among professionals and writers.

Slang and regional words constitute the texture of language and give colour and tone to communication. In the world of business, the main concern is to communicate with sincerity, courtesy, and a sense of mutual respect. The aim is to write or speak in simple and clear English using the language of everyday speech. The aim of business writing is to earn the goodwill of the reader. The writing should sound friendly and cooperative.

For this purpose special care should be taken to create a friendly and pleasant tone in business writing (letters/memos) by avoiding harsh and rude words.

Semi-formal Tone

The semi-formal tone lies somewhere between informal and academic. It is expressed mostly through standard English and is written according to the accepted rules of grammar, punctuation, sentence construction, and spelling, with a few contractions that add a sense of informality. The following sentence also has a semi-formal tone: ‘Much to their embarrassment and Mammachi’s dismay, Chacko forced the pretty women to sit at the table with him and drink tea’.

Strictly Formal Tone

The strictly formal tone is scholarly and uses words that are long and not frequently spoken in everyday conversation. The construction of the sentence and paragraph is also academic and literary in its tone.

The strictly formal tone is scholarly and uses words that are long and not frequently spoken in everyday conversation.

Positive Language

Business letters and memos should accentuate positive thoughts and expressions while stemming negative ones. Some tips to do so are:

- Avoid using words that underline the negative aspects of the situation.

- Write with a cool frame of mind. Do not write out of anger of excitement.

- Do not allow anger or harshness to creep into the writing.

- Focus on the positive when possible.

The following are examples of how, by substituting positive-sounding words and phrases for negative ones, the general tone (effect/impact) of each sentence can be changed without changing the message.

Negative: We have received your complaint.

Positive: We have received your letter.

(We receive letters. No one can mail a complaint.)

Negative: Your faulty fan motor will be replaced.

Positive: We are sending you a new fan motor with a one-year guarantee.

Negative: The delay in dispatching your order because of our oversight will not be longer than a week.

Positive: Your complete order will reach you by July 24.

To eliminate the accusing and insulting tone of the original sentence, substitute neutral words for words that are insulting or make the reader feel dishonest or unintelligent.

Insulting: Don’t allow your carelessness to cause accidents in the blast furnace.

Neutral: Be careful when you are working in the blast furnace.

Insulting: Because you failed to inform the members of the board about the agenda in time, the meeting had to be postponed.

Neutral: The meeting had to be postponed as the board members did not receive the agenda in time.

Remember that negative language regarding the situation is bound to distance the reader. To win the reader’s cooperation, one must emphasize solutions instead of criticizing the situation.

You-Attitude

In all writing, the author has a point of view. You-attitude is the reader’s point of view. In good business writing, especially letters, the author should write from the reader’s point of view, by viewing things as readers would. He or she should be able to see and present the situation as the reader would see it. Writers should try to convey an understanding of the reader’s position and present the information by visualizing how it will affect the feelings of readers.

In all writing, the author has a point of view. You-attitude refers to the reader’s point of view.

In the following examples, the focus is shifted from the author’s point of view to the reader’s point of view by emphasizing the benefits and interests of the reader in the given situation.

Author’s emphasis: I congratulate you on successfully completing the task.

Reader’s emphasis: Congratulations on successfully completing the task.

Author’s emphasis: To reduce office work and save time, we are introducing a new system of registration for you.

Reader’s emphasis: To facilitate the registration process, we are changing our system of registration.

Author’s emphasis: We are sending out interview calls next Monday.

Receiver’s emphasis: You should receive the interview letter by Thursday, August 12.

The change of emphasis in these examples is psychological. By giving importance to the reader’s concerns (his or her point of view) and benefits, one can develop a friendly tone.

Some guidelines for reflecting the ‘you’ point of view in business correspondence are:

- Empathize with the reader. Place yourself in his or her position.

- Highlight the benefits to the reader in the situation.

- Adopt a pleasant tone as far as possible.

- Avoid negative words and images. Do not use words that insult or accuse the reader.

- Offer helpful suggestions if possible.

- Use words that are familiar, clear, and natural. Avoid old-fashioned expressions or jargon.

Exhibit 8.7

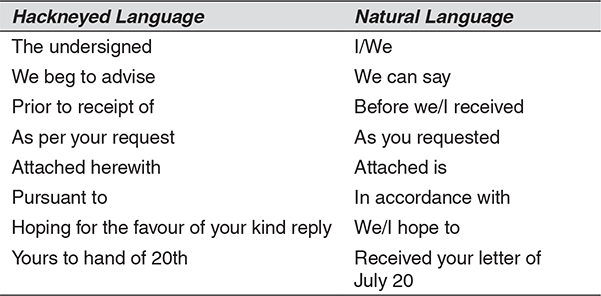

Old-fashioned Expressions

Natural Language

Letters and memos should be written in the language of everyday speech. They should avoid using clichés and hackneyed expressions. Archaic expressions will make the message dull and uninteresting for the reader. Exhibit 8.7 lists some examples of phrases that should be rewritten.

Consider the naturalness of the following sentence. Do we normally talk like this?

As per your request, we beg to inform you that we have booked a single room for you at our lodge for 4 days from 18 July to 21 July 2003.

This sentence lacks the spontaneity and liveliness of a natural response. It should be revised as:

As you desired, we have booked a room for you from 18 July to 21 July 2003.

The message should be brief. The specification of the room, single or double, need not be given here. Simply confirming the dates is sufficient.

Active Voice

There are two parts of a sentence—the subject and the predicate. The subject is that about which something is said; the predicate is whatever is said about the subject. In a sentence the subject is the main focus, the doer of an action. It is frequently positioned at the opening of the sentence.

Choose the active voice to help the reader understand the main message at the very beginning of the sentence. Passive voice is long-drawn because the ‘to be’ form of verb is used with the preposition ‘by’ and is then followed by the doer of the action. In passive voice, the main focus of the sentence, the subject (in the writer’s mind), is mentioned at the end of the sentence—by then the reader may become impatient and lose focus. For example, read the following sentences closely:

Choose the active voice to help the reader understand the main message at the very beginning of the sentence.

Active: Packaging often describes the product’s look and feel to the buyer.

Passive: The product’s look and feel are often described to the buyer by its packaging.

Read both the forms of the sentence together. You will find that the passive sentence reads slowly and moves heavily. It tells you about ‘packaging’ only at the end of the sentence. It first speaks about the product’s look and feel. Technically, the two sentences are talking about two different things. The passive-voice sentence tells the reader about a product’s look and feel and how they are described for the buyer through packaging. It indirectly talks about packaging. The active-voice sentence speaks more directly about packaging and its functions of describing a product’s look and feel to the buyer. The sentence is short and it grips the reader’s attention. Readers therefore usually prefer active voice for its directness, faster pace, and clarity.

Here are a few problems readers often face because of the use of passive voice:

- Passive voice in issuing instructions: Instructions should be clear, direct, and complete because passive voice may confuse the reader. The instruction may omit the ‘by’ preposition phrase and thereby leave the question ‘who should do it’ unclear. The doer of the action is left implied and is not clearly stated.

Unclear: The strike should be called off. [By whom? Not stated]

Clear: The strike should be called off by the union.

- Dropping the ‘by’ phrase: Often, the writer attempts to shorten the length of the passive-voice sentence by leaving out the ‘by’ phrase after the verb. This makes it difficult for the reader to understand the full process of the action as the sentence does not offer complete information.

Incomplete: To make these allocations, marketing managers use sales response functions that show how sales and profits would be affected.

Complete: To make these allocations, marketing managers use sales response functions that show how sales and profits would be affected by the amount of money spent in each application.

- Confusing use of dangling modifiers: The reader is often confused by the misplaced modifier in the passive construction. Therefore, avoid this form of passive construction and write in active form.

Unclear: Besides saving on mailing expenses, a double-digit response will be achieved by a customer database system.

Clear: Besides saving on mailing expenses, a customer database system will achieve a double-digit response.

Sexist Language

Sexist expressions and ideas should be avoided in business communication. Sexist language consists of words or phrases that show bias against the competence or importance of women. In today’s gender-sensitive age, business writing should scrupulously leave out all words that question women’s dignity, competence, or status.

Often the use of sexist language is unconscious—one may fail to realize that a certain phrase or word is an unfavourable reference to the abilities of women. However, such expressions are not acceptable to modern readers.

Consider the following guidelines to avoid sexist words and phrases:

Often the use of sexist language is unconscious—one may fail to realize that a certain phrase or word is an unfavourable reference to the abilities of women.

- Do not use ‘he’ as a generic pronoun. In the past, it has been customary to refer to people in general, or a group of persons, as male. ‘He’ is grammatically correct, but should be avoided in generic situations, especially job descriptions.

Sexist: A manager writes to his peers in an informal or semi-formal tone.

Revised: Managers write to their peers in an informal or semi-formal tone.

In this example, the number of the subject has been changed from singular to plural, and ‘their’ has been used as the pronoun, thus avoiding any hint of sexism. - In job descriptions, do not use words which suggest that all employees are of the same gender.

Sexist: An experienced professor is needed. He should…

Revised: An experienced professor is needed. He or she should…

Or

An experienced professor is needed. The person should be…

Sexist: The policeman should listen to the common man’s complaints.

Revised: The police officer should listen to the common man’s complaints.

Sexist: The stewardess explained the safety measures before take-off.

Revised: The flight attendant explained the safety measures before take-off.

- Do not use words that lower the dignity and status of women. Also never use slang words to refer to women.

Do not use words that lower the dignity and status of women. Also never use slang words to refer to women.

Sexist: The girls in the central office will endorse these papers.

Revised: The office assistants in the central office will endorse these papers.

Sexist: Do bring the little woman (slang for one’s wife) to the party.

Revised: Do bring your spouse to the party.

- Always refer to women and men in the same way.

Sexist: Denise Samrat, Dr Ian Campbell, and Dr Philip Kotler were members of the CRM panel.

Revised: Ms Denise Samrat, Dr Ian Campbell, and Dr Philip Kotler were members of the CRM panel.

Sexist: Women of this sector were represented by two doctors and one lady lawyer.

Revised: Women of this sector were represented by two doctors and one lawyer.

Finally, writing business letters clearly and accurately requires that the following points be kept in mind:

- A sentence is the smallest unit of a complete thought.

- Each sentence should have only one thought.

- Sentences and paragraphs should be constructed according to the principles of unity and coherence.

For instance, consider this sentence: ‘This activity makes no attempt to be a comprehensive test of accurate writing, but offers a valuable chance for you to test your own skill and identify areas of weakness’. This sentence talks about only one topic—‘a test of accurate writing’. Other ideas are related to the main subject.

In contrast, examine the following sentence: ‘I hasten to inform you that your complete order has been shipped on 10 April, the invoice will reach you with the goods’. This sentence is not correctly constructed. It has two separate thoughts, which should be expressed in separate sentences. A better version would be: ‘I hasten to inform you that your complete order has been shipped on 10 April. The invoice will reach you with the goods’.

SUMMARY

- This chapter shows that the ability to communicate information in a simple, concise, and accurate written form reflects a manager’s professional competence.

- It discusses in detail the essentials of effective written communication—planning, identification of purpose, consideration of audience, choice of appropriate language, and use of effective tone.

- This chapter also provides tips and guidelines to help readers develop a good grasp of grammar, the use of words, and the construction of sentences, with the goal of strengthening their written communication skills.

CASE: ON WRITING WELL

In his famous book, On Writing Well, William Zinsser cautions potential writers about some common pitfalls of writing. Zinsser maintains that if the reader is unable to keep pace with the writer’s train of thought, it is not because the reader is lazy or dumb. Rather, this difficulty can be attributed to the author, who, because of the many forms of carelessness, has failed to keep the reader on the right track.

The ‘carelessness’ Zinsser alludes to may be of many kinds:

- Writers often write long-winding sentences and switch tenses mid-sentence. Also, a sentence may not logically flow from the previous sentence, although the writer knows the connection in his or her head. This makes it hard for the reader to make sense of what is being said, and they lose track.

- Sometimes, writers don’t take the trouble of looking up a key word, and end up using the wrong word. For example, the word ‘sanguine’ (confidently optimistic and cheerful) may be confused with ‘sanguinary’ (accompanied by bloodshed), which changes the meaning of a piece drastically.

- Surprisingly often, writers do not know what they are trying to say. So, they should always question themselves about what they are trying to say, and if they have said it. They should re-read the piece and ask themselves: ‘Will it be clear to a person who reads it for the first time’? If the answer to this question is ‘no’, it means that some ‘fuzz’ has crept into the writing.

Says Zinsser, ‘The clear writer is a person who is clearheaded enough to see this stuff for what it is: fuzz’. 2 He further adds that thinking clearly is an entirely conscious act. It’s not as if some people are clear thinkers and, therefore, clear writers, and others are born fuzzy and can’t hope to write well. The ability to write well comes from clear thinking and logic, which a writer should constantly aim to inculcate.

Unless Zinsser’s list of potential obstacles to clear writing is kept in mind, a writer runs the risk of turning in a piece where the reader is left wondering who or what is being talked about.

Questions to Answer

- What is fuzz? Explain Zinsser’s notion of fuzz with a few examples.

- Do you believe that some people are born writers? Give reasons for your answer.

REVIEW YOUR LEARNING

- Give at least three reasons for knowing and following the conventions of grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

- What is the difference between unity and coherence?

- What is the relationship between brevity and clarity?

- Give some important characteristics of effective writing in business.

- What is ‘you–attitude’ in business writing?

- Explain the function of tone in making communication truly effective.

- Define the role of the reader in determining the form and style of business letters.

- How do we make our writing natural?

- To what extent does clarity of writing depend on the clarity of thinking?

- Why should we avoid using jargon and clichés in business letters or memos?

REFLECT ON YOUR LEARNING

- Why do most of us find it difficult to convey our thoughts in written form? How can we overcome these difficulties?

- Do pre-writing thinking and post-writing revising help the writer? Please discuss.

- ‘It is simple to be difficult, but very difficult to be simple while writing’. Elucidate.

- How does extensive reading help in writing effectively?

- Reflect on the value of short and simple sentences in creating a lucid style.

APPLY YOUR LEARNING

- Change the following expressions into more natural language:

- Pursuant to

- Prior to the receipt of

- It has come to my attention

- The undersigned will

- Hoping for the favour of a reply

- Rewrite each of the following sentences to reflect more positive thoughts:

- To avoid further confusion and delay, our Assistant Engineer will visit your place and try to rectify the problem.

- I was not invited to the party, so I did not come.

- The company will not hold the wages you have earned.

- He left no plan untried.

- Do not let carelessness cause an accident when working on the machines.

- Change the following sentences from passive to active voice:

- I am sorry to find that you were not promoted this year.

- This is a suitable time for the new project to be started.

- I am extremely astonished at your behaviour.

- It is now time for the applications to be invited.

- The idle candidates were selected.

- Write the correct form of the verb given in brackets in the blank space.

- On _______ the news, the meeting was postponed. (receive)

- We were surprised to ______ our boss there. (find)

- By _______ early, they avoided traffic jams. (leave)

- Do not let me prevent you from _______ what is right. (do)

- He was charged with _______ into a house. (break)

SELF-CHECK YOUR LEARNING

From the given options please choose the most appropriate answer:*

- To complete the function of the written word, we require:

- three persons

- one person

- two persons

- four persons

- In business, the purpose of writing is mainly to:

- entertain

- inform

- persuade

- Both (b) and (c)

- Informative writing focuses primarily on the:

- reader

- subject under discussion

- latest news

- writer

- In writing business letters, one has to be:

- formal

- dull

- conventional

- friendly

- Technical accuracy of language means:

- direct narrative

- active voice

- correctness of grammar, spelling, and punctuation

- simplicity

- The principles of effective writing include:

- brevity

- clarity

- accuracy

- All of the above

- In a sentence, the verb agrees in number and person with its:

- object

- subject

- adverb

- preposition

- How many kinds of articles are there in English?

- Three: a, an, and the

- Two: definitive and indefinitive

- One: a

- Both (a) and (b)

- ‘There’, as an introductory subject:

- requires the verb to agree with its unreal subject

- requires the verb to agree with the real subject that comes after it

- requires the verb to agree with the object

- is always singular

- In issuing instructions, one should avoid the:

- passive voice

- active voice

- imperative form

- subjunctive form

ENDNOTES

- Muriel Harris, Guide to Grammar and Usage (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2002).

- William Zinsser, On Writing Well, New York: Harper, 1998.