I. The Play

Rhesus occupies a unique and important place in literary history for the following three reasons:

- (1) it is the only extant Greek tragedy that takes its plot from an episode in Homer, the spurious Iliad 10, also called Doloneia.3

- (2) if we reject Euripidean authorship (as most scholars now do), it is the only Greek tragedy surviving intact from the fourth century BC.

- (3) it has influenced several later authors, most notably Virgil in Aeneid 9, and found its way into the late-antique ‘Selection’ of Euripides’ ten most popular plays.

The play has been much maligned, especially by critics who wished to prove it spurious, for its episodic structure, extravagant stage-action, wooden characters and the ostensible lack of any intellectual or ‘tragic’ import.4 Part of this can hardly be denied. But we have to ask what the poet wanted to achieve and whether some of the play’s alleged flaws are not in fact explained by his dramatic intentions.

A delight in spectacle, perhaps in accordance with the theatrical expectations of the day, is obvious (cf. ch. III.3). The shortest of all Greek tragedies, Rhesus boasts two messenger scenes (264–341, 728–803), two agones (388–526, 804–81) and two divine epiphanies in the middle and at the end of the play (595–674, 882–982). Athena’s impersonation of another goddess, Aphrodite, and the Muse’s lament from the top of the skene have no precedents in classical drama, and the rapid movements of the chorus (1–51, 675–91) far surpass earlier choral prologues and search-scenes. If one further adds Rhesus’ ‘god-like’ splendour in his costume (301–8), the possibility of a chariot entry (380–7) and the rarity of having an entire play set in the darkness of night,5 it is no wonder that Rhesus became a success and was revived more than once during the fourth century BC (cf. p. 26).

Yet Rhesus is no tale of adventure, in contrast to its model, Iliad 10. The poet chose the perspective of the Trojans, who despite their recent victory and some further successes in the future, were destined to be overcome by the Greeks. The audience’s knowledge of this will have coloured their perception of Hector’s confidence and outspoken reliance on the support of Zeus or ‘fate’ (cf. 52–84, 319–20nn.), which remains unshaken by Rhesus’ death and the Muse’s revelation that it was divinely ordained (938–49; cf. 983–96n.).

The Thracian is presented as Troy’s greatest asset, a hero not only able to defeat Achilles (cf. 314–16n.), but also resembling him in much of his life and posthumous fate (pp. 10, 13–14). Crucially, however, neither Hector nor the chorus (who are much more enthusiastic about the unexpected ally) ever learn that, far from just boasting about his martial prowess (443–53) and being elevated to near-divine status (342–79, 380–7), he could really have changed the course of the war.6 This information Athena imparts to Odysseus and Diomedes as the reason why they should direct their assault at him (600–4). Again only the audience can measure the extent to which the Trojans are in danger.

If the Trojans are deluded about their situation, the two Greeks hardly appear in a better light, as they enter the enemy camp, timidly and prepared to retreat when they do not find Hector in the place Dolon indicated (565–94). It is a fine touch, rather than a mark of dramatic incompetence, that in Rhesus he leaves before the arrival of the Thracians and so cannot betray them to Odysseus and Diomedes. Instead Athena guides their steps before and after the attack (595–641, 568–74).7

More often than the Greeks, who effect a cunning escape in 675–91 (n.), the Trojans and their allies (in the person of Rhesus’ charioteer) are seen making false decisions or groping in the dark, literally as well as metaphorically (1–51, 52–84, 65–9, 85–148, 692–727, 728–55nn.). The night, frequently referred to for the sake of maintaining the theatrical illusion,8 thus becomes both a cause and symbol of human improvidence – unlike in Iliad 10, where it worries the Achaean leaders, but ultimately helps Odysseus and Diomedes to succeed.9

Dramatic meaning, action and structure are closely interrelated in Rhesus.10 The play falls into two halves. In the first part (1–564) we witness a build-up of Trojan confidence in the characters of Hector, Dolon and Rhesus, whereas the second (565–996) deals with the destruction of the high hopes set in and expressed by Dolon and the Thracian king. The agents of their death – Odysseus and Diomedes (with Athena in the background) – appear suddenly and unannounced, engaged in a conversation that in form and content resembles a second prologue (565–94n.).

The doubling of typical scenes fits into this pattern. Each half of the play contains a messenger speech, the one by the Shepherd (284–316) describing Rhesus’ glorious arrival, the one by the Charioteer (756–803) his inglorious death. The two agones likewise mirror each other. In the first one (388–526) Hector accuses Rhesus of tardiness in coming to his aid, in the second (804–81) he himself is accused by the Charioteer of having killed his ally (cf. 804–81, 833–81nn.). The scenic reversal, which illustrates the reversal in the Trojans’ fortune, is underlined by the distantly separated lyric stanzas 454–66 ~ 820–32 (nn.).11

Continuity, on the other hand, is visible in the parodos (1–51) and epiparodos (675–727), where each time the chorus act ‘in whirling motion – but with nothing at all as a result’.12 The epiphanies of Athena (595–674) and the Muse (882–982) are similar in function. Just as the Greeks are unable to achieve their goal without divine assistance, the Trojans need supernatural elucidation to solve the mystery of Rhesus’ death.

Regarding the poet’s use of leitmotifs, we have already seen how Hector persists in his belief that he is fated to prevail and how Rhesus is elevated by regular juxtaposition with Achilles (and Ajax). In addition, wolf-imagery characterises Dolon and produces an ironic contrast when, rather than taking the head of Odysseus or Diomedes (219–23n.) and getting Achilles’ horses as a reward, he himself is killed and robbed of his wolf-skin by the Greeks, whom subsequently the Charioteer in his dream pictures as wolves attacking Rhesus’team of horses (201–23, 780–8nn.). A similar paradox is created by the watchword, ‘Phoebus’, which (because of Dolon’s betrayal) not only fails to protect the Trojan camp, but actually helps the Achaeans to escape (521–2, 675–91nn.).13

Rhesus is simply, but carefully, constructed, with a whole network of visual and thematic correspondences between the scenes.14 Its unity does not lie in the Aristotelian principle of having one episode follow upon another with probability or necessity (cf. Poet. 1450b22–34, 1451b32–5), but in the idea of human fallibility and men’s dependence, for good or ill, on the will of the gods. This also constitutes the ‘tragedy’ of the play, as does the prospect of Hector’s death and the fall of Troy. In contrast to what we know of fifth-century drama, the characters on stage remain for the most part unaware of their fate,15 which also perhaps accounts for the absence of a true ‘tragic hero’ and the fact that none of the Trojans (as opposed to the Charioteer and the Muse) seems genuinely moved by Rhesus’ death. He is but an incident in the much larger tragedy of their war.

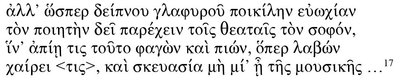

What then does Rhesus offer and where are its limitations? It is excellent theatre – not only in terms of stagecraft, but also for some impressive set pieces (the two messenger speeches and the Muse’s account of Rhesus’ past and future) and, it must be added, very competent, even beautiful, lyrics (the ‘Dawn-Song’, 527–64, stands out). For those who knew their Homer and were not too dazzled by the ‘spectacle’ it also afforded a deeply pessimistic outlook on the story of Troy and human life in general, which may have suited a period of restoration after the Peloponnesian Wars.16 That many of the characters (notably Hector, Dolon and Rhesus) are overdrawn, their conflicts pointless or not fully developed 17 and the language and scene composition heavily dependent on earlier sources18 is equally true, but should not prevent us from taking this poet seriously. His agenda is perhaps best described by the four lines Athenaeus (10.411b) quotes from the satyric Heracles of Astydamas II (TrGF 60 F 4):

A clever poet should supply his audience with

a rich feast that resembles an elegant dinner,

so everyone eats and drinks whatever he likes before

he leaves, and the entertainment doesn’t consist of a single course.20