II. Plot And Myth

Rhesus is the only surviving Attic drama, except for Euripides’ satyr-play Cyclops, where we also possess the epic version and can compare the two in a productive way.21 As will be seen (and has already been demonstrated by Ritchie), the poet essentially keeps to Iliad 10, developing hints from it in many of his more original scenes. At the same time, however, he has enhanced his adaptation by including other motifs from Homer and the Epic Cycle, as well as divergent information about of Dolon and especially Rhesus, taken from Hellenic sources and Thracian cult. The result is an exciting representation of what happened on the Trojan side that night, particularly after the narrative returned to the Greeks at Il. 10.526.22

1. The Greek Tradition

(a) Iliad 10 and Homer

This section analyses the action of Rhesus in relation to its epic models. For greater detail the reader is referred to the commentary, especially the scene introductions.

In terms of plot-construction, the parodos (1–51) and first epeisodion (52–223) show all the techniques our poet employed. For lack of an adequate precedent among the Trojans in ‘Homer’, the sequence of 1–148 has been devised as a mirror-image of Il. 10.1–179, which describes the anxious commotion in the Greek naval camp. Yet after a closely adapted introductory scene (1–51, 23–5 1nn.), other Iliadic material comes in. Hector’s speech in 52–75 largely follows that of his epic self at Il. 8.497–541, with only the occasional nod to Iliad 10 there and in the ensuing dialogue with the coryphaeus (52–84, 56–69, 82–3nn.). Conversely, Aeneas advising Hector to dispatch a scout before attacking the Greeks in the dark (85–148) corresponds to Menelaus in Il. 10.37–41, whereas his actual character and words are based on Polydamas in Iliad 12, 13 and 18 (85–148, 105–30nn.).

With the two Dolon scenes (149–94 + 201–23) the plot turns to the Trojan assembly in Il. 10.299–337. But again the narrative has been expanded from elsewhere in Homer and, for the first time, an external source. The ‘guessing-game’ by which Dolon elicits the promise of Achilles’ horses as a reward for his expedition is informed by the proxy negotiations between Agamemnon and Achilles in Iliad 9, and the animals themselves are described after Il. 16.149–51 + 23.276–8 (cf. 149–94, 185–8nn.). Dolon’s wolf-disguise and four-footed walk (208–13), on the other hand, go back to a parallel tradition attested in vase paintings since the early fifth century BC and were doubtless considered more effective than his semi-military outfit in Il. 10.333–5 (cf. 201–23n.).

Even concerning Rhesus, our poet used what was available in Iliad 10. The epic Thracian is a nonentity, a sleeping source of booty for Odysseus and Diomedes, but the memorable description of his god-like appearance and snow-white horses (Il. 10.435–41) has been incorporated into the Shepherd’s report of his approach (301–8) and is further elaborated in the chorus’ ‘cletic hymn’ and entry announcement (342–79, 380–7nn.). Likewise, the position Hector assigns to Rhesus and his men in 518–20 (cf. 613–15) matches that of Il. 10.434, a telling detail after different precedents (including the  in Iliad 3) had to be invoked for the encounter between Hector and the Thracian king (388–526, 388–453, 467–526nn.).

in Iliad 3) had to be invoked for the encounter between Hector and the Thracian king (388–526, 388–453, 467–526nn.).

Adaptation of Iliad 10 continues with a series of worried remarks about Dolon’s absence (523–6, 557–61, 557–8nn.), shortly before Odysseus and Diomedes arrive carrying his spoils (591–3n.). Their entry dialogue (565–94) contains several allusions to the spy’s interception and death (Il. 10.339–468),23 which allow the audience to reconstruct his fate. Knowledge of Rhesus, however, has to come from Athena, since Dolon never set eyes on him. The goddess’ role in 595–641 (n.) seems closer to Pindar’s version of the Rhesus myth (pp. 11–12), but her conversation with Odysseus and Diomedes is replete with echoes of Iliad 10, and a new stage in the action is reached when the heroes divide their ‘duties’ between killing the Thracians and leading away the marvellous steeds (Rh. 622–3 ~ Il. 10.479–81).

Athena’s deception of Paris (642–67) is another invented episode. Yet one may argue that it presents a variation on the typical epic scene in which a god misleads a human in the guise of a mortal friend and in particular Athena’s deluding of Hector in Il. 22.222–305 (cf. 642–74n.). After the Trojan’s departure the goddess addresses the returning Greeks (668–74), just as in Il. 10.509–11 she had warned Diomedes to escape while they could.

The epiparodos (675–91 + 692–727) dramatises a single sentence in the epic source. The commotion caused by the searching chorus parallels that of the Trojans when, alerted by Hippocoon, they discover the massacre in the Thracian camp (Il. 10.523–4). Rhesus’ cousin has an equivalent in the Charioteer, who comes on stage, first to bewail his master and himself (728–55n.), then to give a highly idiosyncratic account of the attack (756–803n.). The latter adapts the authorial narrative of Il. 10.471–97, with two important modifications: (a) the Thracians ineptly rest in complete disorder (762–9n.), and (b) Rhesus’ climactic nightmare of Diomedes standing at his head (Il. 10.496–7) becomes an uncanny symbolic dream of the Charioteer (780–8n.).

With the circumstances of Rhesus’ death ends the straightforward application of Iliad 10. The following scene of accusations between Hector, the chorus and the Charioteer (804–81) mentions Odysseus as the presumable killer of both Rhesus and Dolon (861–6), but otherwise springs entirely from our poet’s mind. The same is true of the Muse’s apparition (882–982). As the mother of Rhesus she has no precedent in the epic, nor probably any earlier version of the myth (p. 13); instead the lament for her son is modelled on that of Thetis for Achilles in Il. 18.54–64 (cf. 890–914, 915–49nn.), while Rhesus’ background and translation to cultic honours are developed from parallels in the Epic Cycle, Sarpedon’s story and Thracian lore (pp. 13–14, 14–18). After a look ahead to Achilles’ death and funeral (Rh. 974–9 ~ Od. 24.58–64, Aethiopis Arg. p. 112 (4) GEF), she departs, leaving the humans to prepare for battle in a way that recalls both Il. 8.497–541 and the beginning of Iliad 11 (cf. 983–96n.).

It emerges that Rhesus moves through Iliad 10 almost in the order of events, making extensive use also of the ‘Greek part’.24 The material is skilfully integrated, and our poet takes care to return to the epic plot after each digression. Allusions to other Iliadic episodes centre on the surrounding books (8–12), with occasional references back and forward. We thus get a comprehensive picture not only of that single night, but also of the entire war, including Hector’s death and the fall of Troy.25 Some of the ‘cyclic’ echoes discussed in the next section work in the same direction.

(b) Other Sources

Not surprisingly, non-Homeric accounts have mainly been called upon in scenes that bear no direct relationship to Iliad 10. But they do not simply fill mythological gaps or provide pathos and additional dramatic interest; we also note shifts in the interaction between gods and men and an intention to go beyond the legend of Troy.

While our poet may or may not have had a written source for Dolon’s wolf-disguise (p. 9), his other models can be traced in the fragments of early epic, lyric and tragedy. The most important ones are two alternative tales about Rhesus, recorded in the scholia to Il. 10.435.

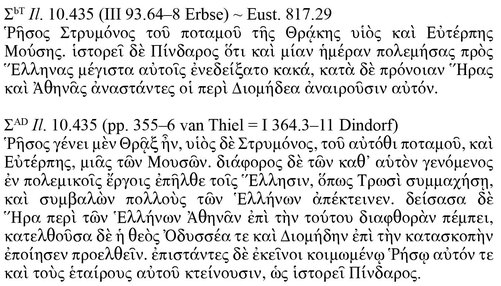

According to the first, which is ascribed to Pindar (fr. 262 Sn.–M.), the Thracian wrought havoc among the Greeks for one day until Athena, on Hera’s orders, incited Odysseus and Diomedes to kill him:

From there, it seems, stems Rhesus’ extravagant claim of being able to end the Trojan War in one day (447–53n.) and especially the expansion of Athena’s role from the benevolent force behind the Achaeans in Iliad 1026 to the coolly manipulative operator who leaves men little freedom to decide or act (565–94, 595–674, 595–641, 642–74nn.).27

The mythical pre-existence of Rhesus’ earlier campaigns (406–11a, 426–42nn.), on the other hand, is not guaranteed by the extended narrative of ΣAD Il. 10.435.28 Much of it reads like extrapolations from ‘Homer’, and it is possible that διάϕορος δὲ τῶν καθ᾽ αὑτὸν γενόμενος ἐν πολεμικοῖς ἔργοις also comes from our play rather than from Pindar or an unknown source.

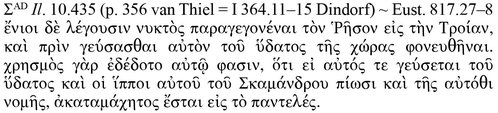

The same note continues to report an oracle that Rhesus would be invincible once he and his horses drank from the Scamander and the animals grazed on the local pastures:

Virgil used this version for his description of the Tyrian temple of Juno (Aen. 1.469–73), but without making Troy’s fall dependent on the fulfilment of the prophecy, as Servius and others did.29 In Rhesus there is a trace of the invincibility motif when Athena, somewhat unexpectedly, verifies the hero’s boasts by declaring that nobody will be able to stop him from sacking Greek camp if he survives his first night at Troy (600–4n. ; cf. 388–526, 595–641nn.).

Both sets of scholia begin by identifying Rhesus’ parents, Strymon and Euterpe, and the assumption that at least the Muse already belonged to Pindar’s treatment was essential to Fenik’s controversial reconstruction of an epic-cyclic narrative from Rhesus and the said variants (Iliad X, 5–63). But her very anonymity in the play and the fact that subsequent witnesses disagree about her name suggest that there was no fixed tradition,30 and our poet either invented the connection (by analogy with Orpheus?) or, less likely, followed some Thracian belief. He would probably have heard of Clio’s sanctuary near the μνημεῖον for Rhesus in Amphipolis (Marsyas II FGrHist 136 F 7 = ΣV Rh. 346 [II 335.12–13 Schwartz = 94.6–7 Merro]; cf. p. 15).

Still, in other ways, the Epic Cycle has had a defining influence on Rhesus. Episodes like the Palladion theft, the ‘Ptôcheia’ and perhaps the capture of Helenus (all from the Little Iliad) were brought forward in time to underline the Trojans’ contempt for Odysseus and the threat he poses to them (498b–509, 501–2, 503–7a, 507b–9a, 692–727, 710–21nn.).

In particular, however, we find pertinent overlaps between Rhesus’ dramatic personality and fate and those of Achilles, Cycnus, Penthesileia, Memnon, Eurypylus and Sarpedon, as portrayed in the Iliad, the Epic Cycle and tragedies based on their accounts.31 Four of these heroic figures (Cycnus, Penthesileia, Memnon, Eurypylus) form a group of foreign allies to Troy who arrived late or, in the case of Cycnus, at the very beginning of the war only to be killed in battle by Achilles or Neoptolemus. The analogies with Rhesus are obvious,32 and even if he was not part of that tradition from an early date, as Fenik argued, it is easy to see how his biography and theatrical representation came to share the following further elements with their and related tales:

- (1) a Trojan appeal for military assistance: Eurypylus and, from at least the early fourth-century BC, Memnon (399–403n.).

- (2) parental reluctance to let the son go to war, with divine foreknowledge of his death at Troy: (Eurypylus), Achilles (899–901, 934–5a nn.).

- (3) grief and lament at his untimely demise: Sarpedon, Achilles, Memnon, Eurypylus (882–9, 908–9, 915–49, 967–9, 974–7nn.).

- (4) supernatural intervention for his body: Sarpedon, Memnon, Achilles (882–9, 962–6nn.).

- (5) childhood in the care of nymphs: Achilles (926–3 1n.).

- (6) a boastful attitude, splendid armour and perhaps a chariot displayed on stage: Cycnus, Memnon (301b–8, 380–7, 388–526nn. and pp. 1, 41).33

The overall pattern of Rhesus has been successfully compared to Aeschylus’(?) Cares = Europa,34 which arguably covered, from Europa’s perspective, the death of Sarpedon, his miraculous transfer to Caria and the ensuing funeral preparations 35 and so, like our play, supplied the tragic aftermath to a myth ‘begun’ in Homer. A. Nereids would be similar if it indeed stood third after Myrmidons and Phrygians and dealt with Achilles’ last battle and elevation to the Island of the Blessed (882–9, 915–49, 978–9nn.).

2. Rhesus of Thrace

While the Muse’s prediction of her son’s metamorphosis into a subterranean ‘man-god’ and Bacchus prophet on Mt. Pangaeus (962–73) remains our only evidence for a possible association of Rhesus with the Satrae’s oracle of Thracian Dionysus (cf. 962–82, 970–1, 972–3nn.), there can be no doubt that the hero played a considerable part in north-eastern Mediterranean myth and belief. Unfortunately, however, most sources are late and do not readily admit conclusions about actual religious practice.

One positive case is the Greek-style hero cult which, for a time at least, Rhesus received at Amphipolis. It was installed by the city’s founder Hagnon in 437/6 BC after a (probably Delphic) oracle had declared that he could colonise the site of Ennea Hodoi only if Rhesus’ bones were returned from Troy (Polyaen. 6.53). Despite the many picturesque details that riddle the story, 36 the event as such is generally accepted as historic and compared to the Spartans’ divinely ordained ‘theft’ of Orestes’ relics from Tegea (Hdt. 1.67–8)37 and that of Theseus when the Athenians seized Scyrus about 475 BC.38 Moreover, the description by Marsyas of Philippi of a Clio sanctuary in Amphipolis opposite a memorial for Rhesus (p. 13) has been partly confirmed by the excavation of the former, which from its style and the letters of a votive inscription (Εὔμητις | Ἡγησιστράτο |Κλεοῖ |ἀνέθηκεν) was dated to the early fourth century BC.39 Malkin, among others, indeed believes the herôon might go back to Hagnon ‘because the cult seems to have ceased after the citizens of Amphipolis transferred the title of oikist to Brasidas in 422 B.C., and turned against the “Hagnoneia” in anger’ (~ Thuc. 5.11.1).40

A note in Strabo (7 fr. 16a [II 366.5–7 Radt]) to the effect that Rhesus once ruled among the Odomantes, Edoni and Bisaltae41 strengthens his claim to being a ‘native’ of the lower Strymon area. Further east he is linked by Hippon. fr. 72. 5–7 IEG ἐπ᾽ ἁρμάτων τε καὶ Θρεϊκίων  / λευκῶν

/ λευκῶν  / ἀπηναρίσθη Ῥῆσος, Αἰνειῶν πάλμυς to Aenus at the mouth of the Hebrus,42 but it would be hazardous to infer local worship from that. More likely Hipponax meant

Θρῄκων βασιλεύς and chose the only Thracian town named in the Iliad (4.520) to stand for its entire country.43

/ ἀπηναρίσθη Ῥῆσος, Αἰνειῶν πάλμυς to Aenus at the mouth of the Hebrus,42 but it would be hazardous to infer local worship from that. More likely Hipponax meant

Θρῄκων βασιλεύς and chose the only Thracian town named in the Iliad (4.520) to stand for its entire country.43

Outside Byzantium, by contrast, the Suda (ρ 146 Adler) explicitly mentions a precinct of the naturalised epic hero: Ῥῆσος: … στρατηγὸς τῶν Βυζαντίων, τὰς οἰκήσεις ἔχων πρὸ  πόλεως ἐν τόπῳ ἐπιλεγομένῳ Ῥησίῳ, ἔνθα νῦν ὁ οἶκος τοῦ μεγάλου μάρτυρος Θεοδώρου γνωρίζεται,44 ἦλθεν εἰς συμμαχίαν τῶν

πόλεως ἐν τόπῳ ἐπιλεγομένῳ Ῥησίῳ, ἔνθα νῦν ὁ οἶκος τοῦ μεγάλου μάρτυρος Θεοδώρου γνωρίζεται,44 ἦλθεν εἰς συμμαχίαν τῶν  … This could be a mere deduction from the place name,45 were it not the case that churches frequently occupied former pagan sites and Appian (Mith. 1.1–2) reported a Greek tradition that part of Rhesus’ surviving force made a detour via Byzantium before settling with the rest in what would become Bithynia. And Herodotus (7.75.2) says the Bithynians were originally Thracians from the Strymon.

… This could be a mere deduction from the place name,45 were it not the case that churches frequently occupied former pagan sites and Appian (Mith. 1.1–2) reported a Greek tradition that part of Rhesus’ surviving force made a detour via Byzantium before settling with the rest in what would become Bithynia. And Herodotus (7.75.2) says the Bithynians were originally Thracians from the Strymon.

Philostratus (Her. 17.3–6) tells of a Rhesus who haunts Mt. Rhodope – breeding horses, marching in armour, hunting and protecting the mountain villages from pestilence, while groups of wild animals come to his altar for voluntary sacrifice. In the absence of parallel testimonies we cannot be sure how far the story represents true folklore or was re-created by the author from other myths or his own resources.46 It certainly looks as if he thought of the Thracian Hero or Horseman, an indigenous divinity (usually represented as a rider) who was venerated well into the Christian era and whose functions and activities are known from countless plaques and cult reliefs to have coincided with those of Rhesus in the Heroicus.47 Yet archaeological evidence for the identification

48 is lacking, despite the frequent syncretism of the Horseman with other deities – notably Apollo, Asclepius and Dionysus (below) – and such non-specific titles as Ἥρως, Κύριος or Δεσπότης, to which Ῥῆσος in the sense ‘King’ (n. 21) would also have belonged. All we can safely posit therefore is a generic affinity between Rhesus and the Hero as ancestor figures, without ruling out the possibility that Philostratus’ narrative was based on more than that. At the gates of Byzantium Rhesus may have had apotropaic qualities (like the Heros  ),49 and in view of his status as a cave-dwelling ‘prophet of Bacchus’, it is interesting to note the regular association also of the Thracian Horseman with Dionysus and/or the underworld.50 Significantly perhaps, as Perdrizet called to mind, the Pangaean Bacchus oracle was served by Bessi from western Rhodope.51

),49 and in view of his status as a cave-dwelling ‘prophet of Bacchus’, it is interesting to note the regular association also of the Thracian Horseman with Dionysus and/or the underworld.50 Significantly perhaps, as Perdrizet called to mind, the Pangaean Bacchus oracle was served by Bessi from western Rhodope.51

Finally, in a way that appears to be purely literary, and to a large degree dependent on our play (cf. pp. 44–5), Rhesus has been incorporated into the Cian legend of Arganthone. According to Parthenius of Nicaea (Erot. Path. 36),52 the hero’s earlier campaigns around the Propontis (Erot. Path. 36.1 ~ Rh. 426–42) also brought him to Mt. Arganthon, in the hope of winning the beautiful, reclusive hunting-maiden who bore its name. Having been successful by stealth, he one day follows a noble embassy to Troy (Erot. Path. 36.4 ~ Rh. 399–403, 839–40, 935–7, 954–7), although Arganthone, from dire premonitions, desperately tries to hold him back (Erot. Path. 36.4 ~ Rh. 900–1, 934–5). Like the Muse again, she is consumed by grief upon learning of his death (uniquely in battle with Diomedes, on the banks of the river whose eponym he would become)53 and, as a mortal woman, eventually passes away through self-starvation.

The essence of the story recurs in Stephanus of Byzantium (α 394 Billerbeck Ἀργανθών· ὄρος Μυσίας ἐπὶ τῇ Κίῳ, ἀπὸ Ἀργανθώνης Ῥήσου γυναικός), and Arrian presumably took Rhesus to be the father of Arganthone’s sons Thynus and Mysus (FGrHist 156 FF 59, 83). From that one can see most easily how the compound myth evolved ‘to explain the [ethnic] links between Thrace and Bithynia / Mysia and north-western Asia Minor generally’.54

Despite certain reservations, therefore, it is clear that Cicero (nat. deor. 3.45) was wrong to claim that Rhesus (and Orpheus), although born of Muses, were not considered deities and hence nowhere worshipped. 55 Our poet seems to have been aware of some genuinely Thracian cultic realities, which he used to dignify an unpromising tragic hero and perhaps to astonish his audience again at the end of the play. An easy connection would have been provided by Amphipolis, the goal of several further Athenian expeditions between 422 and 360/59 BC. Their military and economic aspirations for the lower Strymon valley ended only with the rise of the Macedonian kingdom (921–2a n.).

Appendix: The ‘Macedonian Theory’

In this context mention must be made of Liapis’ hypothesis that Rhesus was first produced in Macedon during the reign of Philip II or Alexander the Great (i.e. between ca. 350 and 330 BC).56 So late a dating does not seem to fit what little external evidence we possess (cf. pp. 27–8), but above all the theory rests on a series of arguments from the play which do not bear close examination. The Pangaean cult of Rhesus has already been established as of potential interest to the Athenians, and even if this were not the case, we know too little about fourth-century tragedy to tell whether a cult aition that bore no relationship to Attica would have been impossible. Six further points are put forward in JHS 129 (2009), 71–88 (n. 36):

- (1) The peltai borne by Rhesus and his people in 305–6, 311–13, 383–4, 409–10 and 485–7 ‘do not seem to be the small, light, crescent- or round-shaped shields’ (p. 74) normally connected with Thracian warriors (who to the Athenians were known as auxiliaries first in the Persian army and later in their own), but rather resemble the larger round Macedonian peltai carried by the main infantry troops.

- (2) Rh. 2 ὑπασπιστῶν … βασιλέως ‘recalls a Macedonian technical term, ὑπασπισταὶ οἱ βασιλικοί, which designated the Foot Guardsmen associated with the Macedonian king’ (p. 77). These apparently developed under Philip II.57

- (3) When in 26–7 πέμπε ϕίλους ἰέναι ποτὶ σὸν

, / ἁρμόσατε

, / ἁρμόσατε  ἵππους the sentries ask Hector ‘to send his ‘friends’ to his ‘own cavalry company’ and order that the horses be harnessed’ (p. 78), this may refer to the Macedonian heavy cavalry, called ἑταῖροι or ϕίλοι, and more specifically the king’s personal squadron (ἴλη ἡ βασιλική).

ἵππους the sentries ask Hector ‘to send his ‘friends’ to his ‘own cavalry company’ and order that the horses be harnessed’ (p. 78), this may refer to the Macedonian heavy cavalry, called ἑταῖροι or ϕίλοι, and more specifically the king’s personal squadron (ἴλη ἡ βασιλική). - (4) The chorus’ outspoken manner towards Hector (cf. 23–33, 76–7, 131–2) and his deference to their judgement (137) may reflect Macedonian ἰσηγορία, the traditional right of every soldier to express his own opinion.

- (5) The introduction of Aeneas as an adviser to Hector (85–149), without any hint of ‘the strained relations’ between him and ‘the house of Priam’ (Il. 13.459–61, 20.178–86, 302–8), could have been meant to bring on stage and ‘cast in as glorious a light as possible the man who was by some accounts a mythical ancestor of certain Macedonians’, having founded ‘a number of cities in the region named Aenus and Aenia after him’ (p. 81).

- (6) The pro-barbarian attitude of Rhesus, combined with distinct hostility towards the Greeks and their patron goddess Athena (especially in 938–49) is ‘best … explained by the hypothesis that [the play] was produced before an audience wary of Athens, and of Greece as a whole’ (p. 83).

To each of these arguments one or more objections can be raised: (1) Thracians in drama are regularly equipped with peltai (e.g. Alc. 498 ~ Rh. 370–2, E. fr. 369.4, Ar. Lys. 563). At the same time tragedy tends to describe ‘mythical’ fighting in terms of contemporary hoplite warfare, transferring the appropriate gear and/or vocabulary to the epic heroes. This almost certainly also happened with regard to Rhesus and his men (cf. 305–6a, 311–13, 383–4, 485–7nn.). Note that 370–3 seems to presuppose a crescent-shaped shield (372b–3a n.).

(2) The lexical similarity, striking as it appears, may be coincidental, especially since the normal interpretation of the phrase as ‘the king’s squires’ (2–3n.) avoids a near-tautology with 3 ἢ τευχοϕόρων (‘ordinary soldiers’).58 It is possible, however, that ὑπασπισταί had a history of denoting the private retinue of the Macedonian nobility and king (as opposed to the later corps of 3000 (!) men), in which case a ‘northern’ allusion could exist.59

(3) Rh. 26 far more probably means ‘Send for your friends to join your company’, with absolute πέμπω, ‘send word’, governing an infinitive clause. In that case the allusion is to Il. 10.53–179 + 299–302, where the Greek chiefs and Hector respectively call together their most important companions (23–51, 26nn.).

Hector’s unit also appears in 577 (n.). As for the harnessing of the horses (27), there is no need to think of anything but Homeric chariot warfare. Aeneas warns of the risks should the vehicles get stuck in the Achaean trench (116–18n.).

(4) In 339–41 (339, 340–1nn.) Hector is equally deferential to the combined views of the coryphaeus and the Shepherd, who is no soldier. ‘Weak leadership’ and a propensity for peremtoriness, which Hector shows elsewhere (152–3, 264–341, 808–19nn.), do not exclude each other (indeed often go together), and a more active chorus of soldiers than in Ajax or Philoctetes needed something to say (cf. 131–6n.). Absolute realism was not upheld.

(5) In choosing a less obscure Trojan than Polydamas to caution Hector, our poet may have taken account of Aeneas’ Balkan links (85–148n.). But Thrace rather than Macedon suggests itself in a play about Rhesus, who according to Hippon. fr. 72.7 IEG was Αἰνειῶν πάλμυς. The Iliadic tensions between Aeneas and Hector are omitted, or probably never thought of, as irrelevant to the plot.

(6) Emphasis on ‘barbarian’ valour is natural in a tragedy (the only one we possess) that portrays the Trojans on the brink of victory over the Greeks. But for the audience their optimism is always coloured by the knowledge that the dawning day will bring a decisive turning-point in the war (cf. ch. I). Individual Trojans do not look so good either: Dolon’s bravery (154–223) can be assumed to have faltered in the face of Odysseus and Diomedes and Paris is easily hoodwinked by Athena (642–67).

The essential dominance of the Greek side throws a different light also on the Muse’s anger towards Athena, which is as understandable as it is futile. At 974–9 she can only anticipate the death of Athena’s protégé Achilles (after he has killed Hector), and whether she threatens Athens with cultural decline depends on the text and interpretation of 948–9 (n.). It seems improbable that ambitious Macedonians of the mid-fourth century BC would have liked to be associated with the failing Trojan cause.