The Play

Scene and Setting

The stage represents Hector’s bivouac in the temporary camp which the Trojans set up at the end of Iliad 8. The skene is ignored, as part of the realistic setting on the open plain and perhaps a tribute to early-fifth-century dramatic technique (Introduction, 40–1).215 Of the two eisodoi, the one to the audience’s right leads to the main body of Trojans and further to the seashore with the Achaean ships; the one to the left leads to the Thracian camp, Troy and Mt. Ida, from which the Shepherd and Rhesus arrive (L. Battezzato, CQ n.s. 50 [2000], 367–8).

The time is indicated by Rh. 5–6 (n.) οἳ τετράμοιρον νυκτὸς  /

/  στρατιᾶς προκάθηνται. This corresponds to the beginning of Iliad 10 in the same way as the choral song 527–64 (n.) adapts Il. 10.251–3

στρατιᾶς προκάθηνται. This corresponds to the beginning of Iliad 10 in the same way as the choral song 527–64 (n.) adapts Il. 10.251–3  γὰρ

γὰρ  ἄνεται, ἐγγύθι δ᾽ ἠώς, / ἄστρα δὲ

ἄνεται, ἐγγύθι δ᾽ ἠώς, / ἄστρα δὲ  προβέβηκε,

προβέβηκε,  δὲ

δὲ

μοιράων,

μοιράων,  δ᾽

δ᾽  (on Homer’s three night watches as opposed to the five in Rhesus see 538–45n.). At 985 (983–5n.) the sunrise heralds the end of the nocturnal play.

(on Homer’s three night watches as opposed to the five in Rhesus see 538–45n.). At 985 (983–5n.) the sunrise heralds the end of the nocturnal play.

Hector is first seen lying on his ‘leaf-strewn couch’ (9), surrounded by his attendants (2–3) in a sort of ‘opening tableau’ (cf. Taplin, Stagecraft, 134–6). Other tragedies that began with the parodos also had the main character silent on stage before: A. Niobe, Myrmidons (both mocked by ‘Euripides’ in Ar. Ran. 911–20) and the spurious Prometheus Unbound (O. P. Taplin, HSPh 76 [1972], 58–76). Hector is neither lost in grief (like Niobe and Achilles) nor has he been tormented for endless years, but perhaps our poet wished to show briefly the peace of the victorious night before rapid action initiates the fatal chain of events.

1–51. A chorus of Trojan sentries hurries in from the audience’s right in order to wake Hector and tell him important news (1–10). Some agitated dialogue (11–22) is followed by a call to arms (23–33: strophe) and, after further complaints from Hector (34–40), the actual report (41–51: antistrophe).

The anapaestic-lyric composition (below) leads the spectators in medias res. But it soon becomes clear that we have here a dramatisation of Iliad 10, which tells the story from the Trojan perspective. As the convocation of Hector’s assembly at Il. 10.299–302 did not offer much material, our poet modelled his parodos on the ‘Homeric’ opening episode (Il. 10.1–202).216 The watchfires and noise are transferred to the Greek camp (23–51, 41–3a, 41–2, 44–8nn.), the fearful commotion now lies on the Trojan side (15, 17–18, 36–7a nn.). Several echoes in language and content underline the inversion. In particular, the chorus’ initial conversation with Hector matches Agamemnon’s rousing of Nestor in Il. 10.73–101 (7, 11–14, 15nn.). Like the sentries, he had been worried by the activities in the enemy camp and found Nestor, as later Diomedes, sleeping in the open and under arms (20–2n.). Even the structural parallelism of Iliad 10 is to some extent reproduced in the choral song. For while the strophe recalls in greater detail the Greek preparations at the beginning of the book (23–51n.), the rally of their army described in the antistrophe mirrors the Trojan gathering that is shown on stage (R. S. Bond, AJPh 117 [1996], 265). And part of Rh. 44–8 probably depends on Dolon’s assumption of a meeting by Agamemnon’s ship at Il. 10.325–7.

Within this framework the parodos resembles a (Euripidean) messenger scene with many of its typical elements: the question for the addressee (2–6), a general announcement (4), a short counter-question, here multiplied in Hector’s confusion (11–22), and the request for the full account in 38–9 (cf. Strohm 266–9, 273 with n. 1). But as in 728–55 (n.) the scheme is varied to give an effective picture of human fallibility and nocturnal tumult (Strohm 258–66, 272–3, H. Parry, Phoenix 18 [1964], 284–5, Introduction, 4–5). When the sentries finally get a chance to speak, they recommend action instead of telling the ‘news in brief ’ (23–33),217 and their message proper (41–51) mainly consists of visual and aural impressions, nothing sure (76–7, 79). This is far from the clear and well-structured report in anapaests that Hecuba receives from the Trojan Women about the imminent sacrifice of Polyxena (Hec. 105–40). Rather we may compare the Phrygian’s aria (Or. 1368–1502), where regular iambic questions from the coryphaeus punctuate ‘a not entirely  account’ (Willink on Or. 1366–1502). Similarly, at Hec. 658–725 (which moves from trimeters through mixed speech and lyric back to trimeters)

the usual introduction is transferred to a situation that for the moment cannot be clarified. The maidservant does not know how Polydorus died, and thus no messenger speech is to come (Strohm 267–8, 272–3).

account’ (Willink on Or. 1366–1502). Similarly, at Hec. 658–725 (which moves from trimeters through mixed speech and lyric back to trimeters)

the usual introduction is transferred to a situation that for the moment cannot be clarified. The maidservant does not know how Polydorus died, and thus no messenger speech is to come (Strohm 267–8, 272–3).

Formally our scene is unlike any prologue we know. Of Euripides’ plays only Iphigenia in Aulis (as it stands) and Andromeda begin with anapaests, but the former (IA 1–48 + 115–62) constitute a recitative (and later partly melic) actors’ dialogue,218 the latter (E. frr. 114–16) a monody of the heroine, interspersed with repetitions from the invisible Echo. For genuine opening parodoi we have to go back to Aeschylus: Persians (1–154), Supplices (1–175ef), Myrmidons (fr. 131), Nereids (fr. 150),219 Niobe (cf. Ar. Ran. 911–15) and [A.] Prometheus Unbound (frr. 190–2). In Persians the Old Councillors can hardly supply more preliminary information, and in Myrmidons, Niobe (?) and Prometheus Unbound the chorus address a person already on stage (‘Scene and Setting’, 114). The last example may have been close to Rhesus, if the initial anapaests were followed not by regular song, but by an epirrhematic dialogue with Prometheus as in the parodos of Prometheus Bound (Griffith, Prometheus Bound, 287–8, 290). What remains unique in our case is the form and degree of interaction between chorus and actor, which sets the tone for the rest of the play (cf. Introduction, 39–40).

It is evident that no iambic prologue has been lost. Anything like the two fragments cited in Hyp. (b) 64.29–65.47 = Rh. 430.26–431.44 Diggle would have caused doublets and greatly impaired the effect of the parodos. Our poet aimed at ‘novelty and excitement’ (Taplin, Stagecraft, 63), for which he was willing to forgo absolute coherence of plot.220 His view of men’s incapacity to understand their world is likewise admirably introduced by the opening we have. Hectic movement that bears little fruit recurs in the epiparodos: 675–91 (n.).

1–10. The chorus’ agitation is reflected in their speech. Short asyndetic clauses rarely occupy more than one anapaestic dimeter (note especially the sequence of disyllabic imperatives in 1 and 7–9), Hector is asked first to raise himself and then to open his eyes (7–8), and his name is postponed to an emphatic position at the beginning of the last verse (10). Some scholars thus wished to make the chorus enter σποράδην and/or to attribute different verses to different members or groups. But the marching anapaests, unlike perhaps the lyrics of 675–82 (675–91n.), favour an ordered entrance, and the language displays even fewer signs of possible division than the introduction to the epiparodos. In 23–33 (23–51n.) asyndeton and hysteron proteron also mark the excitement of the chorus as a whole (cf. Hutchinson on Sept. 78–181 [pp. 56–7]).

1–6. ‘Come to Hector’s sleeping-place! Which of the king’s squires or soldiers is awake? Let him receive a report of the disturbing news (from those) who are placed before the entire army on the fourth watch of the night.’

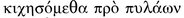

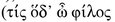

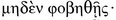

This is the transmitted text and punctuation, supported also by the scholia (cf. 1, 5–6nn.), which yield plausible syntax and an individually well-documented sequence of choral self-exhortation (1n.), proxy question for the recipient of the message (2–3, 4nn.) and explicit information on the speaker’s identity (5–6n.). Several modern editors, however, have been worried by the ‘unconnected’ relative οἵ (5) – though their remedies all entail linguistic and interpretative problems of their own. Stiblinus’ popular τις for  (2) not only ‘offends by its position in the sentence [and] … at the beginning of an anapaestic dimeter’ (J. Diggle, Eikasmos 9 [1998], 44 n. 22), but also creates a weak alternative between one of Hector’s shield-bearers (ὑπασπιστῶν) and the chorus (τευχοϕόρων in this case) as bringers of the news: 1–6 Βᾶθι πρὸς εὐνὰς

(2) not only ‘offends by its position in the sentence [and] … at the beginning of an anapaestic dimeter’ (J. Diggle, Eikasmos 9 [1998], 44 n. 22), but also creates a weak alternative between one of Hector’s shield-bearers (ὑπασπιστῶν) and the chorus (τευχοϕόρων in this case) as bringers of the news: 1–6 Βᾶθι πρὸς εὐνὰς  /

/

βασιλέως,

βασιλέως,  / δέξαιτο νέων

/ δέξαιτο νέων  / οἳ … (Wecklein)221 or, with an impossibly harsh parenthesis, Βᾶθι

/ οἳ … (Wecklein)221 or, with an impossibly harsh parenthesis, Βᾶθι  εὐνὰς

εὐνὰς  /

/

/ ἢ τευχοϕόρων / – δέξαιτο νέων κληδόνα μύθων – / οἳ … (Zanetto). Others went further still. Paley and Feickert, for example, replace

/ ἢ τευχοϕόρων / – δέξαιτο νέων κληδόνα μύθων – / οἳ … (Zanetto). Others went further still. Paley and Feickert, for example, replace  (3) with εἰ from the second ed. Hervagiana (1544) and so must accept a (potential) optative where ordinary usage from Homer on would have a subjunctive after αἴ κε / ἐάν (KG II 534–5 n. 16; cf. SD 631 on the strong hypothetical sense of this εἰ, which may justify the contruction here). No one has endorsed Nauck’s transposition of verse 4 after 9 (Euripideische Studien II, 167) and his δέξαι

(3) with εἰ from the second ed. Hervagiana (1544) and so must accept a (potential) optative where ordinary usage from Homer on would have a subjunctive after αἴ κε / ἐάν (KG II 534–5 n. 16; cf. SD 631 on the strong hypothetical sense of this εἰ, which may justify the contruction here). No one has endorsed Nauck’s transposition of verse 4 after 9 (Euripideische Studien II, 167) and his δέξαι  for δέξαιτο, which brings an unwelcome end to the series of asyndeta (1–10n.). In view of all these objections, and other problematic variations on the paradosis (5–6n.), a slightly ill-prepared relative clause seems to be a tolerable deficiency, especially when it gains support from a doubtful Phoenissae passage (5–6, 12nn.).

for δέξαιτο, which brings an unwelcome end to the series of asyndeta (1–10n.). In view of all these objections, and other problematic variations on the paradosis (5–6n.), a slightly ill-prepared relative clause seems to be a tolerable deficiency, especially when it gains support from a doubtful Phoenissae passage (5–6, 12nn.).

1. Βῆθι πρὸς εὐνὰς τὰς Ἑκτορέους: a choral self-exhortation (cf. ΣΣV Rh. 1 [II 326.2, 18–19 Schwartz = 77 a1, a2 Merro]) of the type ‘stage-direction embodied in the text’ (Collard on E. Suppl. 271 (–2) βᾶθι, τάλαιν᾽ … /  καὶ

καὶ

βαλοῦσα). With

verbs of motion also e.g. A. Suppl. 832, HF 119–20, 124–6 (parodos), S. fr. 314.64, 68, 190, 196, 201 (Ichneutae) and Ar. Lys. 302–3, 321 (the parodoi of the male and female semi-choruses respectively). See Schadewaldt, Monolog und Selbstgespräch, 215–16, Kaimio, Chorus, 129–37 and FJW on A. Suppl. 808–10 (III, p. 156). Similar imperatives occur in the ‘comic-satyric’ search-scene 675–91 (675b, 677, 685nn.).

βαλοῦσα). With

verbs of motion also e.g. A. Suppl. 832, HF 119–20, 124–6 (parodos), S. fr. 314.64, 68, 190, 196, 201 (Ichneutae) and Ar. Lys. 302–3, 321 (the parodoi of the male and female semi-choruses respectively). See Schadewaldt, Monolog und Selbstgespräch, 215–16, Kaimio, Chorus, 129–37 and FJW on A. Suppl. 808–10 (III, p. 156). Similar imperatives occur in the ‘comic-satyric’ search-scene 675–91 (675b, 677, 685nn.).

βῆθι: Diggle for  (Ω). The intrusion of Doric α in recitative anapaests is not uncommon (Diggle, Textual Tradition, 122). In Rhesus cf. 22, 538, 558, 734, 751, 995.

(Ω). The intrusion of Doric α in recitative anapaests is not uncommon (Diggle, Textual Tradition, 122). In Rhesus cf. 22, 538, 558, 734, 751, 995.

πρὸς εὐνὰς τὰς Ἑκτορέους: Owing to the central significance of Hector’s bivouac (‘Scene and Setting’, 114), variants of this phrase occur throughout the play: 87–8  … /

… /  σὰς πρὸς εὐνάς, 574 εὐνὰς … τάσδε πολεμίων, 575–6 Ἕκτορος / κοίτας, 580–1, 605–6, 631, 660. The ‘proper name’ adjective Ἑκτορέους – with Aeolic -ρε- for *-ρι- (Chantraine, GH I, 170, LfgrE s.v. Νεστόρεος) and here uniquely of two terminations – immediately sets an epic tone (Il. 2.416, 10.46, 24.276, 579, Il. Parv. fr. 29–30.2 GEF). Similarly Rh. 44–5

σὰς πρὸς εὐνάς, 574 εὐνὰς … τάσδε πολεμίων, 575–6 Ἕκτορος / κοίτας, 580–1, 605–6, 631, 660. The ‘proper name’ adjective Ἑκτορέους – with Aeolic -ρε- for *-ρι- (Chantraine, GH I, 170, LfgrE s.v. Νεστόρεος) and here uniquely of two terminations – immediately sets an epic tone (Il. 2.416, 10.46, 24.276, 579, Il. Parv. fr. 29–30.2 GEF). Similarly Rh. 44–5  … σκηνάν, 258–9, 386, 762. For εὐναί of soldiers’ temporary or permanent resting-places in the field cf. e.g. Ag. 559, Thuc. 3.112.3 and Pl. Rep. 415e4 (LSJ s.v. εὐνή I 2 b, S. Perris, G&R 59 [2012], 153–4 with n. 18).

… σκηνάν, 258–9, 386, 762. For εὐναί of soldiers’ temporary or permanent resting-places in the field cf. e.g. Ag. 559, Thuc. 3.112.3 and Pl. Rep. 415e4 (LSJ s.v. εὐνή I 2 b, S. Perris, G&R 59 [2012], 153–4 with n. 18).

2–3. Hector’s attendants (below) are addressed first, according to protocol: cf. Xen. An. 2.3.2 οἳ δ᾽ (sc. οἱ κήρυκες) ἐπεὶ ἦλθον πρὸς  προϕύλακας,

προϕύλακας,

ἐπειδὴ δὲ

ἐπειδὴ δὲ  οἱ προϕύλακες,

οἱ προϕύλακες,  … εἶπε τοῖς προϕύλαξι

… εἶπε τοῖς προϕύλαξι  τοὺς κήρυκας

τοὺς κήρυκας  ἄχρι ἂν

ἄχρι ἂν  (Feickert on 2 [pp. 103–4]). Where the skene is involved, a messenger can ask those inside to fetch the desired person: IT 1284–7 (~ 1304–6), Phoen. 1067–9 ὠή,

(Feickert on 2 [pp. 103–4]). Where the skene is involved, a messenger can ask those inside to fetch the desired person: IT 1284–7 (~ 1304–6), Phoen. 1067–9 ὠή,  ἐν πύλαισι

ἐν πύλαισι  κυρεῖ; / ἀνοίγετ᾽, ἐκπορεύετ᾽ Ιοκάστην δόμων. /

κυρεῖ; / ἀνοίγετ᾽, ἐκπορεύετ᾽ Ιοκάστην δόμων. /  μάλ᾽ αὖθις. The latter is followed by a call to Jocasta herself (Phoen. 1070–1),222 as we have it for Hector in 7–10.

μάλ᾽ αὖθις. The latter is followed by a call to Jocasta herself (Phoen. 1070–1),222 as we have it for Hector in 7–10.

ὑπασπιστῶν … βασιλέως: i.e. ‘squires’ (literally ‘shield-bearers’) or ‘subordinate fighting comrades’ (ΣΣVL Rh. 2 [II 326.5–6, 20–1 Schwartz = 77 a1, a2 Merro]), as at Pi. Nem. 9.34 Χρομίῳ … ὑπασπίζων, Hdt. 5.111.1–4, Hcld. 216, Phoen. 1213  παῖς

παῖς  σέθεν (with Mastronarde), Xen. An. 4.2.20, HG 4.5.14, 4.8.39 and, of the whole infantry, A. Suppl. 182 ὄχλον …

σέθεν (with Mastronarde), Xen. An. 4.2.20, HG 4.5.14, 4.8.39 and, of the whole infantry, A. Suppl. 182 ὄχλον …  (with FJW [II, pp. 147–8]). This term from hoplite warfare (Pritchett, GSW I, 49–51, Hanson, Western Way of War, 61–3) is easily transferred to the Homeric world, where anonymous ‘attendants’ are regularly charged with such

tasks as carrying arms (Il. 5.48, 6.52–3, 7.121–2, 13.600, 709–11). On the social range of the epic

(with FJW [II, pp. 147–8]). This term from hoplite warfare (Pritchett, GSW I, 49–51, Hanson, Western Way of War, 61–3) is easily transferred to the Homeric world, where anonymous ‘attendants’ are regularly charged with such

tasks as carrying arms (Il. 5.48, 6.52–3, 7.121–2, 13.600, 709–11). On the social range of the epic  see P. A. L. Greenhalgh, BICS 29 (1982), 81–90, and H. van Wees, in I. Morris – B. Powell (eds.), A New Companion to Homer, Leiden 1997, 670–3.

see P. A. L. Greenhalgh, BICS 29 (1982), 81–90, and H. van Wees, in I. Morris – B. Powell (eds.), A New Companion to Homer, Leiden 1997, 670–3.

The juncture  … βασιλέως, reminiscent as it is of the later technical term for the personal guards of the Macedonian kings

… βασιλέως, reminiscent as it is of the later technical term for the personal guards of the Macedonian kings  οἱ βασιλικοί), may or may not have a northern Greek connection (Introduction, 19, 20).

οἱ βασιλικοί), may or may not have a northern Greek connection (Introduction, 19, 20).

For Hector as  (‘monarch’) see 388–9n.

(‘monarch’) see 388–9n.

ἄγρυπνος: Cf. Rh. 824 ἄγρυπνον  and PV 358

and PV 358  ἦλθεν αὐτῷ

ἦλθεν αὐτῷ

(on which see further 8, 824–6nn.). Like ἀγρυπνέω (‘Thgn.’ 471) and

(on which see further 8, 824–6nn.). Like ἀγρυπνέω (‘Thgn.’ 471) and  (Ar. Lys. 27), the adjective does not recur in poetry before the Hellenistic age.

(Ar. Lys. 27), the adjective does not recur in poetry before the Hellenistic age.

τευχοϕόρων: here ‘ordinary soldiers’ (ΣΣVL Rh. 2 [II 326.6, 21 Schwartz = 77 a1, a2 Merro]) and so probably referring to the more distant members of Hector’s λόχος (26n.).  is a metrical variant form of

is a metrical variant form of  (Cho. 627, E. Suppl. 654, Rh. 267), with o- instead of s-stem composition (Schwyzer 440; cf. KB II 331–2), as in

(Cho. 627, E. Suppl. 654, Rh. 267), with o- instead of s-stem composition (Schwyzer 440; cf. KB II 331–2), as in  (Ar. Ran. 441/2, later) as against

(Ar. Ran. 441/2, later) as against  (Ba. 703, IA 1544) and

(Ba. 703, IA 1544) and  (Hsch. σ 80 Hansen) as against σακεσϕόρος (Bacch. 13.104, Ai. 19, Phoen. 139).

(Hsch. σ 80 Hansen) as against σακεσϕόρος (Bacch. 13.104, Ai. 19, Phoen. 139).

4. δέξαιτο: The subject is Hector (from 1 Ἑκτορέους and 2 βασιλέως). The third (as well as second) person optative expressing a polite command is mainly epic (KG I 229–30, SD 322) and so may add the appropriate tone here. Attic examples of the idiom are few: Xen. An. 3.2.37 εἰ μὲν οὖν  τις

τις  ὁρᾷ,

ὁρᾷ,

δὲ μή, Χειρίσοϕος

δὲ μή, Χειρίσοϕος

…

…  δὲ

δὲ  ἑκατέρων

ἑκατέρων

ἐπιμελοίσθην, 6.6.18

ἐπιμελοίσθην, 6.6.18

(v.l. σῴζεσθέ τε) ἀσϕαλῶς,

(v.l. σῴζεσθέ τε) ἀσϕαλῶς,  θέλει

θέλει  and, with a proverbial force, Ar. Vesp. 1431 ἔρδοι τις

and, with a proverbial force, Ar. Vesp. 1431 ἔρδοι τις

Pl. Rep. 362d6 οὐκοῦν … ἀδελϕὸς ἀνδρὶ παρείη. Ritchie (181) wrongly adds PV 1047, 1048 and 1050 (concessive).

Pl. Rep. 362d6 οὐκοῦν … ἀδελϕὸς ἀνδρὶ παρείη. Ritchie (181) wrongly adds PV 1047, 1048 and 1050 (concessive).

νέων κληδόνα μύθων: Cf. Hel. 1250  ξένε, λόγων μὲν

ξένε, λόγων μὲν  ἤνεγκας

ἤνεγκας  (LSJ s.v.

(LSJ s.v.  II 1), Med. 173–5 πῶς ἂν … / …

II 1), Med. 173–5 πῶς ἂν … / …

/ δέξαιτ᾽ ὀμϕάν and Tro. 230–1 καὶ μὴν … ὅδ᾽ … /

/ δέξαιτ᾽ ὀμϕάν and Tro. 230–1 καὶ μὴν … ὅδ᾽ … /  223

223  μύθων ταμίας, where

μύθων ταμίας, where  (like

(like  here) has the familiar sense of ‘unexpected, strange, disagreeable’ (cf. 589–90n.).the

here) has the familiar sense of ‘unexpected, strange, disagreeable’ (cf. 589–90n.).the

5–6. The (natural) position of the sentries mirrors that of the Greeks 5-6. The (natural) position of the sentries mirrors that of the Greeks at Il. 10.126–7  ἴομεν· κείνους δὲ

ἴομεν· κείνους δὲ  / ἐν ϕυλάκεσσ᾽, ἵνα γάρ

/ ἐν ϕυλάκεσσ᾽, ἵνα γάρ

(~ 10.180–93).

(~ 10.180–93).

οἳ … προκάθηνται: The lack of an antecedent, such as παρ᾽  (ΣΣV Rh. 4, 5 [II 326.19, 327.17 Schwartz = 77, 79 Merro]) or τούτων (cf. KG I 357–8, 394–5, SD 94–5), is much harsher than with other ‘substantival’ relative clauses (KG II 352, 401, 440, SD 640), but mitigated somewhat by our expectation of hearing the source of the news. A telltale parallel exists in the possibly interpolated Phoen. 1602–4 πέμπει δέ με / μαστὸν

(ΣΣV Rh. 4, 5 [II 326.19, 327.17 Schwartz = 77, 79 Merro]) or τούτων (cf. KG I 357–8, 394–5, SD 94–5), is much harsher than with other ‘substantival’ relative clauses (KG II 352, 401, 440, SD 640), but mitigated somewhat by our expectation of hearing the source of the news. A telltale parallel exists in the possibly interpolated Phoen. 1602–4 πέμπει δέ με / μαστὸν

/ οὗ

/ οὗ  224where ‘the antecedent … has to be inferred from πέμπει …

224where ‘the antecedent … has to be inferred from πέμπει …  (Pearson on 1604).

(Pearson on 1604).

Klyve’s supplement <παρὰ τῶν ϕυλακῶν> before οἵ is weak and not borne out by the variants  (Δ et ΣV) and

(Δ et ΣV) and  (Λ) at the end of 5. Although the words could indeed annotate each other (cf. Hsch.

(Λ) at the end of 5. Although the words could indeed annotate each other (cf. Hsch.  918, 972 Hansen–Cunningham),

918, 972 Hansen–Cunningham),  is more likely to be right. Unlike

is more likely to be right. Unlike  (LSJ s.v. I 2), it is well-attested in the sense ‘watch of the night’ (LSJ s.v.

(LSJ s.v. I 2), it is well-attested in the sense ‘watch of the night’ (LSJ s.v.  I 4) and recurs thus at 527, 538 and 543 = 562. Λ also copied πόλεως Τροίας into the middle of 6.

I 4) and recurs thus at 527, 538 and 543 = 562. Λ also copied πόλεως Τροίας into the middle of 6.

τετράμοιρον … ϕυλακήν: ‘the fourth watch’ out of five (538–45, 540–2nn.), as if it was  … (ΣV Rh. 5 [II 326.10–13, 327.3–4, 13–19 Schwartz = 78–9.4–7, 14–15, 25–31 Merro]). Properly, τετράμοιρος, a classical hapax, ought to mean ‘fourfold’ (i.e. ‘having four parts’: cf. Ag. 872 χθονὸς τρίμοιρον

… (ΣV Rh. 5 [II 326.10–13, 327.3–4, 13–19 Schwartz = 78–9.4–7, 14–15, 25–31 Merro]). Properly, τετράμοιρος, a classical hapax, ought to mean ‘fourfold’ (i.e. ‘having four parts’: cf. Ag. 872 χθονὸς τρίμοιρον  and Xen. An. 7.2.36, 7.6.1, HG 6.1.6 τετραμοιρία = ‘fourfold pay’) or ‘a quarter’ (i.e. ‘the fourth part of four’: cf. Nic. Th. 106, 712 (τὸ) τετράμορον, with ΣΣ 106a, 710–13 τετράμοιρον). But the required sense comes close to (τὸ) δίμοιρον = ‘two thirds’ (i.e. ‘two parts out of three’), first found in A. Suppl. 1069–70 τὸ

and Xen. An. 7.2.36, 7.6.1, HG 6.1.6 τετραμοιρία = ‘fourfold pay’) or ‘a quarter’ (i.e. ‘the fourth part of four’: cf. Nic. Th. 106, 712 (τὸ) τετράμορον, with ΣΣ 106a, 710–13 τετράμοιρον). But the required sense comes close to (τὸ) δίμοιρον = ‘two thirds’ (i.e. ‘two parts out of three’), first found in A. Suppl. 1069–70 τὸ  κακοῦ / καὶ τὸ δίμοιρον

κακοῦ / καὶ τὸ δίμοιρον  (LSJ s.v. δίμοιρος I 1). Presumably our poet also wished to refer to the allotment of shifts to the different contingents: 538–45 and especially 545 = 564 (543–5n.)

(LSJ s.v. δίμοιρος I 1). Presumably our poet also wished to refer to the allotment of shifts to the different contingents: 538–45 and especially 545 = 564 (543–5n.)  κατὰ μοῖραν.

κατὰ μοῖραν.

προκάθηνται: a military verb particularly (LSJ s.v. I 2), and not attested anywhere else in poetry.

7–8. For the hysteron proteron see 1–10, 23–51 and 25–5a nn.

7. ὄρθου κεϕαλὴν πῆχυν ἐρείσας: an adaptation of Il. 10.80  δ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ἐπ᾽ ἀγκῶνος,

δ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ἐπ᾽ ἀγκῶνος,  ἐπαείρας, as was already noted by ΣV Rh. 7 (II 327.25–6 Schwartz = 79 Merro). In tragedy cf. Ag. 2–4

ἐπαείρας, as was already noted by ΣV Rh. 7 (II 327.25–6 Schwartz = 79 Merro). In tragedy cf. Ag. 2–4  … )

… )  κοιμώμενος

κοιμώμενος  ἄγκαθεν κυνὸς δίκην /

ἄγκαθεν κυνὸς δίκην /  κάτοιδα νυκτέρων

κάτοιδα νυκτέρων  (with Fraenkel on 3) and, for the language, Alc. 388 ὄρθου

(with Fraenkel on 3) and, for the language, Alc. 388 ὄρθου  …, Hcld. 635 ἔπαιρέ νυν σεαυτόν,

…, Hcld. 635 ἔπαιρέ νυν σεαυτόν,

κάρα, Hipp. 198 …

κάρα, Hipp. 198 …  κάρα, Ba. 933 (Ritchie 205). Also 789 (n.)

κάρα, Ba. 933 (Ritchie 205). Also 789 (n.)  κρᾶτα.

κρᾶτα.

8. λῦσον βλεϕάρων γοργωπὸν ἕδραν: literally ‘Open the grim-eyed seat of your lids’. Unlike  in this application (LSJ s.v. I 1 b), the periphrasis

in this application (LSJ s.v. I 1 b), the periphrasis  for ‘eyes’ has no parallel except 554–6 (n.) θέλγει δ᾽ ὄμματος ἕδραν / ὕπνος· ἅδιστος γὰρ

for ‘eyes’ has no parallel except 554–6 (n.) θέλγει δ᾽ ὄμματος ἕδραν / ὕπνος· ἅδιστος γὰρ  ἀῶ. It can hardly be compared to Tro. 556–7 Περ- /

ἀῶ. It can hardly be compared to Tro. 556–7 Περ- /  ἕδρας (Ritchie 213) or E. El. 458

ἕδρας (Ritchie 213) or E. El. 458  … ἴτυος

… ἴτυος  (with Denniston), nor do we get help from e.g. Pl. Tim. 67b5

(with Denniston), nor do we get help from e.g. Pl. Tim. 67b5

and 72c 1–2

and 72c 1–2  δ᾽

δ᾽  …

…  (LSJ s.v.

(LSJ s.v.  I 3). Hermann (Opuscula III, 292) suggested lexical conflation of Hipp. 290 στυγνὴν ὀϕρῦν

I 3). Hermann (Opuscula III, 292) suggested lexical conflation of Hipp. 290 στυγνὴν ὀϕρῦν  and E. El. 739–41

and E. El. 739–41  …)

…)  /

/  ἕδραν ἀλλάξαν-

ἕδραν ἀλλάξαν-  Hsch. γ 850 Latte γοργωπὸν ἕδραν·

Hsch. γ 850 Latte γοργωπὸν ἕδραν·  [καὶ] καθέδραν. ἢ

[καὶ] καθέδραν. ἢ  shows an early need of elucidation.

shows an early need of elucidation.

Hector’s ‘Gorgon’s eyes’ go back to Il. 8.348–9  … / Γοργοῦς

… / Γοργοῦς  ἔχων, which also inspired Parthenopaeus at Sept. 537 γοργὸν δ᾽

ἔχων, which also inspired Parthenopaeus at Sept. 537 γοργὸν δ᾽  (~ Phoen. 146–7). γοργωπός perhaps comes from PV 356 ἐξ

(~ Phoen. 146–7). γοργωπός perhaps comes from PV 356 ἐξ  δ᾽

δ᾽

where ἄγρυπνος follows in 358 (cf. 2–3n.). But Euripides was also fond of this and related adjectives: Suppl. 322 γοργὸν ὄμμ᾽ (Wecklein for γοργὸν ὣς L; cf. Diggle, Studies, 12–13, where add West, Studies, 311–12 on the text of PV 901–3), HF 131–2

where ἄγρυπνος follows in 358 (cf. 2–3n.). But Euripides was also fond of this and related adjectives: Suppl. 322 γοργὸν ὄμμ᾽ (Wecklein for γοργὸν ὣς L; cf. Diggle, Studies, 12–13, where add West, Studies, 311–12 on the text of PV 901–3), HF 131–2  αἵδε … / ὀμμάτων αὐγαί, 868, 990, 1266, Ion 210, Or. 260–1, Hyps. fr. 18.3 Bond = E. fr. 754a.3. In general see Leumann, Homerische Wörter, 154–5.

αἵδε … / ὀμμάτων αὐγαί, 868, 990, 1266, Ion 210, Or. 260–1, Hyps. fr. 18.3 Bond = E. fr. 754a.3. In general see Leumann, Homerische Wörter, 154–5.

9. χαμεύνας ϕυλλοστρώτους: Despite the very different context, one is reminded of the bed of leaves Odysseus assembled for himself in Od. 5.482–91.

(for the accentuation see Fraenkel on Ag. 1540, Radt on S. fr. 175) is a mainly poetic noun, which denotes a humble couch (Ag. 1540, E. fr. 676.1 [Sciron], Ar. Av. 816) or, as here, an open bivouac (cf. 852–3 χαμεύνας … Ῥήσου, Theoc. 13.33–5, A. R. 3.1193, 4.883).

(for the accentuation see Fraenkel on Ag. 1540, Radt on S. fr. 175) is a mainly poetic noun, which denotes a humble couch (Ag. 1540, E. fr. 676.1 [Sciron], Ar. Av. 816) or, as here, an open bivouac (cf. 852–3 χαμεύνας … Ῥήσου, Theoc. 13.33–5, A. R. 3.1193, 4.883).

The previously unattested  may have been coined after Cyc. 386–7

may have been coined after Cyc. 386–7  / ἔστρωσεν

/ ἔστρωσεν

Pierson: ἔστησεν L). A third-declension form occurs in Theoc. Ep. 3.1 Gow

Pierson: ἔστησεν L). A third-declension form occurs in Theoc. Ep. 3.1 Gow  πέδῳ.

πέδῳ.

10. Ἕκτορ: 1–10n.

καιρὸς γὰρ ἀκοῦσαι: Cf. E. fr. 727a.66 .]μω[.]  καιρὸς [… For the semantic range of

καιρὸς [… For the semantic range of  see Barrett on Hipp. 386–7, J. R. Wilson, Glotta 58 (1980), 177–204, CQ n.s. 31 (1981), 418–20, W. H. Race, TAPA 111 (1981), 197–213 and M. Trédé, Kairos. L’à-propos et l’occasion …, Paris 1992, especially 25–73.

see Barrett on Hipp. 386–7, J. R. Wilson, Glotta 58 (1980), 177–204, CQ n.s. 31 (1981), 418–20, W. H. Race, TAPA 111 (1981), 197–213 and M. Trédé, Kairos. L’à-propos et l’occasion …, Paris 1992, especially 25–73.

11–14. Hector wakes. His first reply mirrors, and adapts to his excitable character, Nestor’s confident questions at Il. 10.82–5 τίς δ᾽ οὗτος

κατὰ  ἀνὰ

ἀνὰ

/

/  δι᾽ ὀρϕναίην, ὅτε θ᾽

δι᾽ ὀρϕναίην, ὅτε θ᾽

/

/  τιν᾽

τιν᾽  διζήμενος,

διζήμενος,  τιν᾽ ἑταίρων; / ϕθέγγεο, μηδ᾽ ἀκέων ἐπ᾽ ἔμ᾽ ἔρχεο. τίπτε δέ σε χρεώ; Thoas displays similar irritation at the messenger’s repeated attempts to call him out of the temple: IT 1307–8

τιν᾽ ἑταίρων; / ϕθέγγεο, μηδ᾽ ἀκέων ἐπ᾽ ἔμ᾽ ἔρχεο. τίπτε δέ σε χρεώ; Thoas displays similar irritation at the messenger’s repeated attempts to call him out of the temple: IT 1307–8

θεᾶς τόδ᾽

θεᾶς τόδ᾽  βοήν, / πύλας ἀράξας καὶ

βοήν, / πύλας ἀράξας καὶ  πέμψας

πέμψας  (cf. 2–3n.).

(cf. 2–3n.).

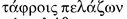

11. τίς ϕθόγγος; – τίς ἀνήρ; This is the text of Δ, with Barnes’ ἦ for  (V:

(V:  O) and Diggle’s parenthesis (Euripidea, 429 n. 40), which fits Hector’s confusion even better than the traditional punctuations

O) and Diggle’s parenthesis (Euripidea, 429 n. 40), which fits Hector’s confusion even better than the traditional punctuations  ὅδ᾽; ἦ

ὅδ᾽; ἦ  (e.g. Paley, Jouan) or τίς ὅδ᾽;

(e.g. Paley, Jouan) or τίς ὅδ᾽;  (Wecklein, Murray, Porter). For the framing question Diggle compares Or. 1269–70 ὅδ᾽ … πολεῖ …

(Wecklein, Murray, Porter). For the framing question Diggle compares Or. 1269–70 ὅδ᾽ … πολεῖ …  and Ba. 578–9 τίς ὅδε,

and Ba. 578–9 τίς ὅδε,  πόθεν ὁ κέλαδος / ἀνά μ᾽ Εὐίου;

πόθεν ὁ κέλαδος / ἀνά μ᾽ Εὐίου;

Zanetto and Feickert read τίς ὅδ᾽; ἦ ϕίλος εἶ; ϕθέγγου, τίς ἀνήρ with Barnes (II [1694], 109), and after the Aldine (τίς ὅδ᾽

and Tr3

and Tr3

ὅστις ἀνήρ;). But the errors in Λ rather point to Δ as the original than vice versa (Paley on 11), and Il. 10.85

ὅστις ἀνήρ;). But the errors in Λ rather point to Δ as the original than vice versa (Paley on 11), and Il. 10.85  (taken up in 12 θρόει and 14 ἐνέπειν χρή) is not sufficient an argument for preferring to ϕθόγγος.

(taken up in 12 θρόει and 14 ἐνέπειν χρή) is not sufficient an argument for preferring to ϕθόγγος.

ϕθόγγος: ‘a friendly voice’ as against an enemy’s: Rh. 687 ἆ·

ϕθόγγος: ‘a friendly voice’ as against an enemy’s: Rh. 687 ἆ·  ἄνδρα μὴ θένῃς, PV 128–30

ἄνδρα μὴ θένῃς, PV 128–30

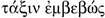

γὰρ ἅδε τάξις / … /

γὰρ ἅδε τάξις / … /  τόνδε πάγον, Hec. 858–9, E. Suppl. 372–3, Lyc. 1242. This usage of

τόνδε πάγον, Hec. 858–9, E. Suppl. 372–3, Lyc. 1242. This usage of  is common in the historians (LSJ s.v. I 1), but does not seem to occur anywhere else in poetry.

is common in the historians (LSJ s.v. I 1), but does not seem to occur anywhere else in poetry.

12. τί τὸ σῆμα; similarly Hyps. fr. 57.10 Bond = E. fr. 758a.10  τὸ

τὸ  [, where, however, σῆμα would mean an ordinary ‘sign’ (Bond). In the sense ‘watchword’ it appears only here and in 688.

[, where, however, σῆμα would mean an ordinary ‘sign’ (Bond). In the sense ‘watchword’ it appears only here and in 688.

θρόει: In anapaests also IA 143  θρόει (cf. Stockert, IA I, 79 n. 376, Introduction, 34), although it may be coincidence that this imperative is otherwise confined to lyrics (PV 608, Or. 187).

θρόει (cf. Stockert, IA I, 79 n. 376, Introduction, 34), although it may be coincidence that this imperative is otherwise confined to lyrics (PV 608, Or. 187).

Ritchie (290–1) wishes to add <(Xo.)  θάρσει>, which from a subsequent note in the margin would have produced 16 (16–19n.), since no reply is given and the dramatically relevant watchword revealed only at 521. But nothing must interrupt Hector’s breathless speech, and θάρσει would seem just as ‘pointless’ here as allegedly after 15. For unanswered questions in tragedy Fraenkel (Rev. 235) quotes Phoen. 376–8, which for precisely this reason were deleted by Usener (RhM N.F. 23 [1868], 155–6 = KS I, 141).225 It may have been ordinary fourth-century technique.

θάρσει>, which from a subsequent note in the margin would have produced 16 (16–19n.), since no reply is given and the dramatically relevant watchword revealed only at 521. But nothing must interrupt Hector’s breathless speech, and θάρσει would seem just as ‘pointless’ here as allegedly after 15. For unanswered questions in tragedy Fraenkel (Rev. 235) quotes Phoen. 376–8, which for precisely this reason were deleted by Usener (RhM N.F. 23 [1868], 155–6 = KS I, 141).225 It may have been ordinary fourth-century technique.

13–14. ἐκ νυκτῶν: ‘at night’. Cf. Rh. 17, 691 (n.), Thgn. 460, Cho. 288, Hp. Morb. Sacr. 15.4 and Xen. Cyr. 8.5.12. The idiom goes back to Od. 12.286–7 ἐκ νυκτῶν δ᾽ ἄνεμοι χαλεποί, δηλήματα νηῶν, / γίνονται, where both the plural and the preposition retain part of their original force (Heubeck on Od. 12.286, Garvie on Cho. 288; ‘out of the night’, with verbs of motion, is still possible in modern English). Analogous formations are Archil. fr. 122.3 IEG ἐκ μεσαμβρίης, S. El. 780  ἡμέρας (with Finglass) and e.g. fr. tr. adesp. 7.3, Xen. Cyr. 1.4.2 ἐκ νυκτός.

ἡμέρας (with Finglass) and e.g. fr. tr. adesp. 7.3, Xen. Cyr. 1.4.2 ἐκ νυκτός.

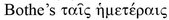

/ κοίτας πλάθουσ᾽: Our poet has a penchant for πελάζω and its cognates: 213

/ κοίτας πλάθουσ᾽: Our poet has a penchant for πελάζω and its cognates: 213  καὶνεῶν προβλήμασιν, 347, 526, 557–8 (n.) τί ποτ᾽ οὐ

καὶνεῶν προβλήμασιν, 347, 526, 557–8 (n.) τί ποτ᾽ οὐ  σκοπός …; 776, 777, 910–11 (n.), 920.

σκοπός …; 776, 777, 910–11 (n.), 920.  /

/  (II [1826], 84) need not be adopted in view of Andr. 1166–7

(II [1826], 84) need not be adopted in view of Andr. 1166–7

ἄναξ

ἄναξ  / …

/ …  πελάζει and maybe OC 1059–61

πελάζει and maybe OC 1059–61

ἐϕέσπερον /

ἐϕέσπερον /  νιϕάδος πελῶσ᾽ /

νιϕάδος πελῶσ᾽ /  ἐκ

ἐκ  (codd.: εἰς νομόν Hartung).226

(codd.: εἰς νομόν Hartung).226

15. ‘Cho. The army’s guards. Hect. Why are you carried away by alarm?’

The earliest extant cases of speaker change between two anapaestic metra are Med. 1397, 1398 and 1402; then Ba. 1372, 1379 (with Dodds on 1372–92), OC 173 and IA 3, 16, 140 – all, as here, in passages of high suspense. Rhesus allows the same in 540 and even divided metra (and feet?) in 16, 17–18 and 560–1 (nn.).

τί  θορύβῳ; In addition to noise, which could wake up others,

θορύβῳ; In addition to noise, which could wake up others,  here implies a degree of panic, as Hector suspects in 36–7 (Fantuzzi, in Ancient Scholarship, 42–6). Similarly Aeneas in 87–9 and, for the Greeks, 44–5 πᾶς δ᾽

here implies a degree of panic, as Hector suspects in 36–7 (Fantuzzi, in Ancient Scholarship, 42–6). Similarly Aeneas in 87–9 and, for the Greeks, 44–5 πᾶς δ᾽  προσέβα στρατὸς /…

προσέβα στρατὸς /…  σκηνάν (cf. 44–8n.).

σκηνάν (cf. 44–8n.).

The meaning of  wavers between ‘being carried along’ and ‘being carried away’, but with 16–18 left standing (16–19n.) the latter has more force. Of various mental states cf. Hipp. 197 μύθοις δ᾽

wavers between ‘being carried along’ and ‘being carried away’, but with 16–18 left standing (16–19n.) the latter has more force. Of various mental states cf. Hipp. 197 μύθοις δ᾽  ϕερόμεσθα, Andr. 729 ἄγαν ἐς τὸ

ϕερόμεσθα, Andr. 729 ἄγαν ἐς τὸ  ϕέρῃ, HF 1246 ποῖ

ϕέρῃ, HF 1246 ποῖ  θυμούμενος; and Hel. 1642 ἐπίσχες ὀργὰς αἷσιν οὐκ

θυμούμενος; and Hel. 1642 ἐπίσχες ὀργὰς αἷσιν οὐκ  ϕέρῃ. The metaphor lies in ‘motion over which one has no control’ (Barrett on Hipp. 191–7 [p. 198]), either by waves, winds or bolting horses (LSJ s.v.

ϕέρῃ. The metaphor lies in ‘motion over which one has no control’ (Barrett on Hipp. 191–7 [p. 198]), either by waves, winds or bolting horses (LSJ s.v.  B I 1; Cho. 1023–4 [with Garvie], PV 883–4).

B I 1; Cho. 1023–4 [with Garvie], PV 883–4).

16–19. ‘Cho. Have no fear! Hect. I have no fear. There is no ambush by night, is there? [Cho. No. Hect.] I mean, why have you left your posts and disturb the army if you do not have some message at night?’

Lines 16–18 have long aroused suspicion, not least because 17 is clearly corrupt. Diggle deletes the whole passage, at the possible price of a lacuna after 15 to prevent a hiatus that would mark period-end without catalexis and sense-pause (West, GM 95). Yet apart from 18 ~ 37b–8a (n.), it is hard to explain the intrusion of the lines, which are consistent with 34–5 and Aeneas’ opening questions at 87–9 and 91–2. Thus, far from being a scribal reconstruction (Ritchie 290–1), 16 (Χο.) θάρσει. (Εκ.) θαρσῶ should be retained as one of several echoes of the dubious anapaestic prologue of Iphigenia in Aulis (Introduction, 34) and 17–18 emended to restore the metre. The easiest, and generally accepted, solution is Dindorf’s excision of 17 … (Χο.) οὐκ ἔστι (Λ: οὐκέτι Δ) (Εκ.) … (III.2 [1840], 589), which anyone who missed an answer could have added. 227 Jackson (CQ 35 [1941], 45 n. 1 ~ Marginalia Scaenica, 12–13), less plausibly perhaps in this hectic dialogue, expands to … (Χο.) οὐκ ἔσθ᾽ <Ἕκτορ>. (Εκ.) τί σὺ γάρ … It is no objection that in either case there remains but a faint metron-diaeresis between ἐκ and νυκτῶν. The phenomenon is paralleled at Phil. 162 δῆλον ἔμοιγ᾽ ὡς | ϕορβῆς χρείᾳ, and even bolder overlaps are found in Pers. 47 δίρρυμά τε καὶ | τρίρρυμα τέλη and HF 449 δακρύων ὡς οὐ | δύναμαι κατέχειν (cf. Griffith, Authenticity of PV, 70–1, L. P. E. Parker, CQ n.s. 8 [1958], 86).228 Attempts that avoid the licence require more severe changes not warranted by the that avoid the licence require more severe changes not warranted by the surrounding text (see Wecklein, Appendix, 48).

16. (Χο.) θάρσει. (Εκ.) θαρσῶ: Cf. IA 2–3 (Αγ.) στεῖχε. (Πρ.) στείχω … / … (Αγ.) σπεῦδε. (Πρ.) σπεύδω (16–19n.). The inner-metric antilabe (15n.) is paralleled in Tr. 976–7 (Πρ.) … ἀλλ᾽ ἴσχε δακὼν / στόμα σόν. (Yλ.) πῶς ϕῄς, γέρον; ἦ ζῇ; 981–2, 991 and the partly corrupt IA 149 (Πρ.) ἔσται. (Αγ.) κλῄθρων δ᾽ †ἐξόρμα (lyric anapaests).

17–18. μῶν τις λόχος ἐκ νυκτῶν; is resumed in 91–2 μῶν τις πολεμίων ἀγγέλλεται / δόλος κρυϕαῖος ἑστάναι κατ᾽ εὐϕρόνην; and the words of 577 … μῶν λόχος βέβηκέ ποι; For μῶν (i.e. contracted μὴ οὖν) introducing apprehensive and/or surprised questions see Barrett on Hipp. 794, who contests the traditional assertion (e.g. KG II 525) that with this particle the speaker invariably expects a negative answer.

λόχος: ‘ambushing party’, as in 560 and e.g. Il. 8.521–2 ϕυλακὴ δέ τις ἔμπεδος ἔστω, / μὴ λόχος εἰσέλθησι πόλιν λαῶν ἀπεόντων (LSJ s.v. λόχος I 3 a, LfgrE s.v. B 3).

Only V is right here. The other MSS read δόλος (OQ et Tr3P2: δοῦλος <LP>), which may be an uncial misreading or a gloss. Conversely, a variant λόχος is attested at 92 (91–2n.).

ἐκ νυκτῶν: 13–14n.

τί σὺ γὰρ …; For the postponement of γάρ see GP 95–6. Its sense is causal-progressive (GP 81–2, 85): ‘I mean, why …’ or ‘Why else then …’

ϕυλακὰς προλιπὼν κινεῖς στρατιάν: one of our poet’s recurrent formulations: 37b–8a (n.) ϕυλακὰς δὲ λιπὼν / κινεῖς στρατιάν, 89 … καὶ κεκίνηται στρατός, 138–9 τάχ᾽ ἂν στρατός / κινοῖτ᾽, 678–9 κλῶπας οἵτινες … τόνδε κινοῦσι στρατόν. There is a realistic fear of panic – at night and close to the enemy (Thuc. 7.80.3). Cf. 15, 20–2, 36–7a, 691nn.

19. νυκτηγορίαν: This is our earliest attestation of the rare noun (cf. LSJ s.v.), which was probably formed after Sept. 28–9 λέγει μεγίστην προσβολὴν Ἀχαιΐδα / νυκτηγορεῖσθαι κἀπιβούλευσιν πόλῃ (‘to discuss by night’).229 The link is reinforced by νυκτηγοροῦσι in 89 and a number of other references to the prologue of Seven against Thebes (Introduction, 34).

20–2. ‘Do you not know that we are lying near the Argive host in full armour all night?’

The Trojans sleep ready for battle (cf. 123–4, 740), as do the Greeks in Il. 10.74–9, 150–6, with the enemy camp nearby (Il. 9.232–3, 10.100–1, 160–1, 221–2). The words recall Sept. 59–60 ἐγγὺς γὰρ ἤδη πάνοπλος Ἀργείων στρατός / χωρεῖ and so an essential point of comparison between the two plays: both Troy and Thebes have been under siege for a while, and the commander-in-chief employs a scout.

δορὸς … Ἀργείου: a favourite juncture of Euripides. Frequently, as here, δόρυ stands for the entire host: Hcld. 500 (Ἀργείων Elmsley: -εῖον L), 674, 834, 842, Tro. 8, Phoen. 1080, 1086, 1094 (Diggle, Euripidea, 442 n. 4, Mastronarde on Phoen. 1086).

νυχίαν … / κοίτην … κατέχοντας: Cf. Ag. 1539–40 πρὶν τόνδ᾽ ἐπιδεῖν ἀργυροτοίχου / δροίτης κατέχοντα χάμευναν, of Agamemnon’s bath, called κοίταν … ἀνελεύθερον in Ag. 1518 (Denniston–Page on 1539–40).

For the ‘Doric’ κοίταν (Ω), corrected by Dindorf (III.2 [1840], 589), see 1n.

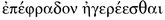

23–51. Instead of answering Hector’s questions, the chorus call for mobilisation in a strophe that shows no sign of their slowing down. As in 1–10 (n.), few of their highly asyndetic orders exceed one verse,230 and absolute logic is not always observed (25–5a n.). It takes another indignant cue from Hector (34–40n.) before the tension is relieved. The antistrophe tells in well-ordered form what has excited the sentries so much: watchfires in the Achaean camp and a rally in front of Agamemnon’s hut.

The ode continues to offer detailed reminiscences of ‘Homer’. At a deeper level than the parodos as a whole (1–51n.), most of the chorus’ instructions to Hector mirror the activities of the Greek chiefs in Il. 10.29–179: ‘take up your arms’ (Rh. 23 ~ Il. 10.29–37, 131–5, 148–9, 177–9), ‘rouse your friends and allies’ (Rh. 23–26, 31–3 ~ Il. 10.53–6, 72–3, 108–13, 125, 136–79) and even the respectful addresses in 28–9 (n.). Their observations, moreover, correspond exactly to those of Agamemnon at Il. 10.11–13 ἤτοι ὅτ᾽ ἐς πεδίον τὸ Τρωϊκὸν ἀθρήσειεν, / θαύμαζεν πυρὰ πολλά, τὰ καίετο  πρό, / αὐλῶν συρίγγων τ᾽ ἐνοπὴν ὅμαδόν τ᾽ ἀνθρώπων. Only the sounds of joy are replaced with such reactions as would be expected of a defeated host (44–8n.).

πρό, / αὐλῶν συρίγγων τ᾽ ἐνοπὴν ὅμαδόν τ᾽ ἀνθρώπων. Only the sounds of joy are replaced with such reactions as would be expected of a defeated host (44–8n.).

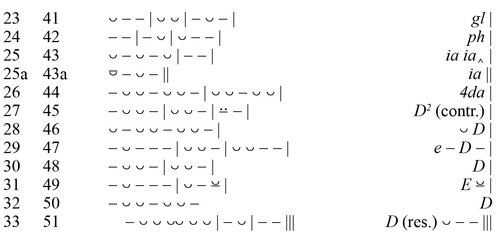

Metre

23–33 ~ 41–51. Aeolo-iambic, merging into dactyls and dactylo-epitrite. The last colon is exceptional (33/51n.), an exotic flourish perhaps to crown an unusually vivid scene.

34–40. Recitative anapaests (continued).

Notes

25–25a/43–43a The lines were rightly separated by Wilamowitz (GV 287–8 n. 2), Ritchie (297) and Willink (‘Cantica’, 23–4 = Collected Papers, 562–3). ‘Bacchiacs’ (ia‸) are all but invariably preceded or, as here, followed by word-end, i.e. stand first or last in a ‘minor period’ (L. P. E. Parker, CQ n.s. 26 [1976], 20 with n. 17).231 The syntax of 25–25a ὄτρυνον ἔγχος αἴρειν, ἀϕύπνισον also supports the division.

27/45 An ambiguous colon, effecting the transition from pure dactyls to dactylo-epitrite, and ‘harmonised’ with each by word-break after the third princeps (cf. Parker, Songs, 49–50). The context favours contracted D2 or 4da‸ (Dale, LM2 43) over a ‘dragged’ ibycean (

), such as Euripides liked to combine with ‘enoplians’ (Schroeder2 167, 182; cf. Willink, ‘Cantica’, 24 = Collected Papers, 563). But we have no certain means of deciding between the two, nor whether any difference would have been felt. A rare length in other tragedy (Parker on Alc. 568–605 Metre [p. 171]), the ‘prolonged hemiepes’ (D2) recurs at 244 ~ 255, 899 ~ 910 (contr.) and 902 ~ 913.

), such as Euripides liked to combine with ‘enoplians’ (Schroeder2 167, 182; cf. Willink, ‘Cantica’, 24 = Collected Papers, 563). But we have no certain means of deciding between the two, nor whether any difference would have been felt. A rare length in other tragedy (Parker on Alc. 568–605 Metre [p. 171]), the ‘prolonged hemiepes’ (D2) recurs at 244 ~ 255, 899 ~ 910 (contr.) and 902 ~ 913.

33/51 Analysis must start from the strophe, which, unlike the antistrophe, shows no obvious sign of textual corruption (33, 49–51nn.). The pattern of word-ends and the link by synartesis with 32 ~ 50 (ὡς), suggest further dactylo-epitrites, and resolved D (cf. Pi. Isthm. 3/4.63 [proper name]) + ba (527–64 ‘Metre’ 536–7/555–6 n.) seems more likely than Willink’s equally unique -  - (‘Cantica’, 25 = Collected Papers, 564).232 Diggle (Studies, 20), followed by Feickert, envisages syncopated iambics (‸ia ‸ia ia‸) or ‘cr cr ba’, but apart from creating split resolution in 33, this would leave us with the impossible sequence -

- (‘Cantica’, 25 = Collected Papers, 564).232 Diggle (Studies, 20), followed by Feickert, envisages syncopated iambics (‸ia ‸ia ia‸) or ‘cr cr ba’, but apart from creating split resolution in 33, this would leave us with the impossible sequence -

- (Parker, Songs, 47). Nothing is gained by Zanetto’s admission of Responsionsfreiheit between the paradosis of 33 and 51 (‸ia ‸ia ia‸ ~ ‸ia ia ia‸), a dubious licence anyway among syncopated and full iambo-trochaics in tragedy (Diggle, Euripidea, 314, against West, GM 103–4; cf. West, Studies, 109–10). For a summary of the treatments applied to our lines see G. Pace, QUCC n.s. 60 (1998), 133–5.

- (Parker, Songs, 47). Nothing is gained by Zanetto’s admission of Responsionsfreiheit between the paradosis of 33 and 51 (‸ia ‸ia ia‸ ~ ‸ia ia ia‸), a dubious licence anyway among syncopated and full iambo-trochaics in tragedy (Diggle, Euripidea, 314, against West, GM 103–4; cf. West, Studies, 109–10). For a summary of the treatments applied to our lines see G. Pace, QUCC n.s. 60 (1998), 133–5.

23–4. ὁπλίζου χέρα: 23–51n. The mainly Euripidean phrase (Alc. 34–5, Phoen. 267, Or. 926, 1222–3) reappears in 84 and 99 (n.).

συμμάχων / … βᾶθι πρὸς εὐνάς: 1, 23–51nn. With συμμάχων for σύμμαχον (Ω) Bothe (5 [1803], 283) and Hermann (Opuscula III, 300)  (Ω) Bothe (5 [1803], 283) and Hermann (Opuscula III, 300) restored metre and syntax.

(Ω) Bothe (5 [1803], 283) and Hermann (Opuscula III, 300) restored metre and syntax.

Ἕκτορ: The emphatic vocative (1–10n.) has the same position in the antistrophe (42). On such ‘isometric echoes’ see 131–6 ~ 195–200 ‘Metre’ (p. 167), 454–66 ~ 820–32 ‘Metre’ (p. 293) and 722n.

25–5a. Cf. 23–51 ‘Metre’ 25–25a/43–43a n. In their haste the sentries request arming before the allies are awake (1–10, 23–51nn.).

25. ὄτρυνον ἔγχος αἴρειν: Given the context (23–51n.), as well as the rarity of epic ὀτρύνω in tragedy, this may indeed be an allusion to Il. 10.54–5 ἐγὼ δ᾽ ἐπὶ Νέστορα δῖον / εἶμι καὶ ὀτρυνέω ἀνστήμεναι (Ritchie 65). Cf. 557–8 (n.).

Badham’s αἴρειν (Philologus 10 [1855], 336) should be read here, with Doric ναῶν (VQ et L1c vel Tr1: νηῶν Luv: νεῶν O) in 43. Porter, Ammendola, Schroeder2 (166), Zanetto (9, 66) and Pace (Canti, 21–2) retain ἀείρειν (Ω) with synizesis.233 But while the form itself is widely attested in tragic lyrics and anapaests (e.g. Pers. 660, Sept. 759, Ag. 1525, Alc. 450, Andr. 848, E. El. 873, Tro. 99, fr. tr. adesp. 482.5; Diggle, Studies, 65), it invites suspicion of ‘scribal epicism’ when not required by metre. Cf. Tr. 216–17 αἴρομαι οὐδ᾽ ἀπώσομαι / τὸν αὐλόν (αἴρομαι οὐδ᾽ Lloyd-Jones: ἀείρομ᾽ οὐδ᾽ codd.), with Ll-J/W, Sophoclea, 157, Second Thoughts, 91.234

25a. ἀϕύπνισον: a rare verb in classical Greek (cf. Eup. fr. 205.1 PCG ἀϕυπνίζεσθαι < > χρὴ πάντα θεατήν, Pherecr. fr. 204 PCG), but recommended by Atticist lexica (Phryn. Ecl. 195 Fischer, [Hdn.] Philet. recommended by Atticist lexica (Phryn. Ecl. 195 Fischer, [Hdn.] Philet. 53 Dain, Moeris α 124 Hansen).

26. πέμπε ϕίλους ἰέναι ποτὶ σὸν λόχον: ‘Send for your friends to join your company.’ On this rendering, absolute  , ‘send word’ (LSJ s.v. I 3), governs an infinitive clause as at Xen. HG 3.1.7 … πέμπουσιν οἱ ἔϕοροι ἀπολιπόντα Λάρισαν στρατεύεσθαι ἐπὶ Καρίαν, IA 360–2 καὶ πέμπεις … / … σῇ δάμαρτι παῖδα σήν / δεῦρ᾽ ἀποστέλλειν (~ IA 98–100, 115–19) or, identifying the messenger, Il. 24.117–19 αὐτὰρ ἐγὼ Πριάμῳ μεγαλήτορι

, ‘send word’ (LSJ s.v. I 3), governs an infinitive clause as at Xen. HG 3.1.7 … πέμπουσιν οἱ ἔϕοροι ἀπολιπόντα Λάρισαν στρατεύεσθαι ἐπὶ Καρίαν, IA 360–2 καὶ πέμπεις … / … σῇ δάμαρτι παῖδα σήν / δεῦρ᾽ ἀποστέλλειν (~ IA 98–100, 115–19) or, identifying the messenger, Il. 24.117–19 αὐτὰρ ἐγὼ Πριάμῳ μεγαλήτορι  ἐϕήσω, / λύσασθαι ϕίλον υἱὸν ἰόντ᾽ ἐπὶ νῆας Ἀχαιῶν, / δῶρα δ᾽ Ἀχιλλῆϊ ϕερέμεν, τά κε θυμὸν ἰήνῃ (with BK on 118) and Rh. 955–6 (954–6n.) τί μὴν ἔμελλον οὐ πέμψειν ϕίλοις / κήρυκας, ἐλθεῖν κἀπικουρῆσαι χθονί; The alternative (e.g. Kovacs,

ἐϕήσω, / λύσασθαι ϕίλον υἱὸν ἰόντ᾽ ἐπὶ νῆας Ἀχαιῶν, / δῶρα δ᾽ Ἀχιλλῆϊ ϕερέμεν, τά κε θυμὸν ἰήνῃ (with BK on 118) and Rh. 955–6 (954–6n.) τί μὴν ἔμελλον οὐ πέμψειν ϕίλοις / κήρυκας, ἐλθεῖν κἀπικουρῆσαι χθονί; The alternative (e.g. Kovacs,  ; The alternative (e.g. Kovacs,

Feickert, Liapis), namely to take ϕίλους as the object of πέμπε and ἰέναι as an infinitive of purpose (cf. Od. 14.396–7 ἕσσας με χλαῖνάν τε χιτῶνά τε εἵματα πέμψαι / Δουλίχιόνδ᾽ ἰέναι, Thuc. 4.132.3) is less natural in the context. We expect Hector’s people to be encamped with him (577), and his ‘friends and allies’ (Paley on 26) to require a summons (Il. 10.299–302).

; The alternative (e.g. Kovacs,

Feickert, Liapis), namely to take ϕίλους as the object of πέμπε and ἰέναι as an infinitive of purpose (cf. Od. 14.396–7 ἕσσας με χλαῖνάν τε χιτῶνά τε εἵματα πέμψαι / Δουλίχιόνδ᾽ ἰέναι, Thuc. 4.132.3) is less natural in the context. We expect Hector’s people to be encamped with him (577), and his ‘friends and allies’ (Paley on 26) to require a summons (Il. 10.299–302).

λόχον: ‘armed band’, ‘body of troops’ (LSJ s.v. λόχος I 3 b; cf. 577, 682, 844). The sense is post-Homeric,235 by extension either of the old ‘ambushing party’ (17–18n.), or by secondary derivation from *λέχω, ‘lay’ (Björck, Alpha Impurum, 292, comparing Swedish lag, ‘company’, and lägga, ‘lay’).

27. ‘Fit the horses with bridles!’

In temporary camps the unyoked horses were tied to their chariots at night, to have them close by in an emergency. Of the Trojans cf. Il. 8.543–4, Rh. 567–8a (n.) and of Rhesus Il. 10.473–5, Rh. 616–17 (n.).

ψαλίοις: a type of noseband, for which the modern technical term is ‘cavesson’, but here pars pro toto for the bridles, as in HF 380–2 τεθρίππων τ᾽ ἐπέβα / καὶ ψαλίοις ἐδάμασσε πώ- / λους Διομήδεος and, metaphorically, Cho. 961–2, PV 54.

The ψάλιον consisted of two U-shaped metal bands, one of which sat on the horse’s nose, the other near the back of its lower jaw. They were connected by vertical bars and provided means to attach the headgear, reins and/or a separate lead rope. Used with or without a bit, the device would increase control over the animal by preventing unwanted movements of the head or mouth (J. K. Anderson, JHS 80 [1960], 3–6, Ancient Greek Horsemanship, 60–1, M. A. Littauer, Antiquity 43 (1969), 291–5 with fig. 3 = M. A. Littauer – J. H. Crouwel, Selected Writings on Chariots, other Early Vehicles, Riding and Harness, Leiden et al. 2002, 491–5 with fig. 3 and plt. 208).

28–9. The polite appellations probably reflect Il. 10.67–9 (Agamemnon to Menelaus) ϕθέγγεο δ᾽, ᾗ κεν ἴῃσθα, καὶ ἐγρήγορθαι ἄνωχθι, / πατρόθεν ἐκ γενεῆς ὀνομάζων ἄνδρα ἕκαστον, / πάντας κυδαίνων … (Ritchie 65, Fantuzzi, in Entretiens Hardt LII, 149–51, I luoghi, 252–3; cf. Il. 10.87, 144, 159). Zeus’ son Sarpedon gets the matronymic, where a god’s name would be out of place.

Πανθοΐδαν: Polydamas or Euphorbus.236 The former plays a greater part in the Iliad and serves as a model for Aeneas in 105–30 (n.). Here, however, the famous patronym (e.g. Il. 13.756, 14.450, 18.250) is all that matters.

Bothe’s reinterpretation of the MSS’ Πανθοίδαν (5 [1803], 284) leaves an ordinary D-colon in responsion with 46. On the tetrasyllabic form see also West, ed. Iliad I, XXIII–XXIV.

τὸν Εὐρώπας: Sarpedon. Il. 6.198–9 make him a son of Zeus and Laodamia, whereas the common (and perhaps older) tradition gives him to Europa, the mother also of Minos and Rhadamanthys: e.g. ‘Hes.’ fr. 140 M.–W. = Bacch. fr. 10 Sn.–M. (ΣD Il. 12.397 [p. 392 van Thiel]),237 ‘Hes.’ fr. 141.11–14 M.–W., Hellanic. FGrHist 4 F 94 (ΣV Rh. 29 [II 327.22–4 Schwartz = 79 Merro]), A. (?) fr. 99.15–23 (Cares = Europa). The last passage is of particular interest for inviting comparison with the grieving Muse (cf. 882–9, 967–9nn., Introduction, 13–14).

Λυκίων ἀγὸν ἀνδρῶν: taken literally from Il. 7.13 (= 17.140) Γλαῦκος δ᾽  πάϊς, Λυκίων ἀγὸς ἀνδρῶν. For Sarpedon cf. Il. 5.647 Σαρπηδὼν Λυκίων ἀγός and 16.541 (~ 16.490) … Σαρπηδών, Λυκίων ἀγὸς ἀσπιστάων, which comes shortly after a reference to Polydamas Πανθοίδης (Il. 16.535).

πάϊς, Λυκίων ἀγὸς ἀνδρῶν. For Sarpedon cf. Il. 5.647 Σαρπηδὼν Λυκίων ἀγός and 16.541 (~ 16.490) … Σαρπηδών, Λυκίων ἀγὸς ἀσπιστάων, which comes shortly after a reference to Polydamas Πανθοίδης (Il. 16.535).

Tragic metre rarely accepts Homeric phrases of more than two words: Med. 425 ὤπασε θέσπιν ἀοιδάν (= Od. 8.498), Phaeth. 243 Diggle = E. fr. 781.30 δι᾽ ἀπείρονα γαῖαν (~ e.g. Il. 7.446, Od. 17.418). See M. Parry, HSPh 41 (1930), 97–8 = The Making of Homeric Verse, 285–6, who cites Andromache’s elegy (Andr. 103–16) as the obvious exception.

30. ποῦ σϕαγίων ἔϕοροι; i.e. the μάντεις (66) normally in charge of pre-battle σϕάγια. These were pure blood-sacrifices, performed in the field, for some last-minute divination and appeasement of the gods (Pritchett, GSW I, 109–15, III, 83–90, M. H. Jameson, in V. D. Hanson [ed.], Hoplites: The Classical Greek Battle Experience, London – New York 1991, 197–227, Liapis on 30 [with further literature]). The practice is not in Homer, but freely transferred back to the Heroic Age by tragedy: Sept. 230–1, Hcld. 399–409, 673, 819–22 (all with Wilkins), Phoen. 174 (with Mastronarde), 1109–12 (1104–40 del. Morus), Or. 1603.

ἔϕοροι (‘overseers’) evokes Pers. 25 στρατιᾶς πολλῆς ἔϕοροι rather than A. Suppl. 674–5 ἐϕόρους γᾶς / ἄλλους, OC 145 ὦ τῆσδ᾽ ἔϕοροι χώρας or fr. tr. adesp. 39 ἔϕορος οἰάκων. For other references to Persians, especially its parodos, see Introduction, 34 with n. 50.

31. γυμνήτων μόναρχοι: ‘leaders of the light-armed troops’. Cf. Rh. 312–13 πολὺς δ᾽ ὄχλος / γυμνὴς ἁμαρτῇ (where the more specialised archers are also mentioned separately), Phoen. 1147 γυμνῆτες ἱππῆς ἁρμάτων τ᾽ ἐπιστάται and, for the first time in Greek literature, Tyrt. fr. 11.35–8 IEG ὑμεῖς δ᾽, ὦ γυμνῆτες, ὑπ᾽ ἀσπίδος ἄλλοθεν ἄλλος / πτώσσοντες μεγάλοις βάλλετε χερμαδίοις / δούρασί τε ξεστοῖσιν ἀκοντίζοντες ἐς αὐτούς, / τοῖσι πανόπλοισιν πλησίον ἱστάμενοι (otherwise prose). Tyrtaeus’ description resembles that of the Locrian archers and slingers at Il. 13.712–22 (with Janko on 712–18).

The unique application of μόναρχος here may suggest that every contingent of Trojan allies was led by their respective ‘king’ (Porter, Feickert on 31). But perhaps it is just a lofty alternative to the common military use of ἄναξ: Pers. 383 ναῶν ἄνακτες (with Garvie on 378–9, 382–3), E. Suppl. 680–1 Φόρβας, ὃς μοναμπύκων ἄναξ / ἦν.

32–3. The peoples of the East had a reputation for archery, which already in the Iliad is more closely associated with the Trojans (F. H. Stubbings, in Companion to Homer, 518). Our poet appropriately gives the men ‘Asiatic’ bows (33n.) and, since Trojans are speaking, eschews the typical Greek contempt for their use in war (Il. 11.385–95 [with Hainsworth], Ai. 1120, Bond on HF 161, Garvie on Pers. 26; cf. 312–13, 510–11nn.).

32. τοξοϕόροι: substantival, as in Hdt. 1.103.1 … καὶπρῶτος διέταξε χωρὶς ἑκάστους εἶναι, τούς τε αἰχμοϕόρους καὶ τοὺς τοξοϕόρους καὶ τοὺς ἱππέας (and there only in classical prose). Elsewhere τοξοϕόρος is an epithet of archer gods or nations: e.g. Il. 21.483, Ar. Thesm. 970 (Artemis), h.Ap. 13, 126, Pi. Ol. 6.59 (Apollo), Tro. 804 (Heracles), Pi. Pyth. 5.41, Call. (?) fr. 786 Pf. (Cretans), Hdt. 9.43.2, ‘Sim.’ Ep. 46.2 FGE, Arist. Ep. 1.2 FGE = fr. 674.8 Rose (Persians / Medes), Nonn. D. 20.225 (Arabs).

Φρυγῶν: ‘Trojans’, as mostly in tragedy at least since Aeschylus (fr. 446) and generally in Rhesus. Cf. E. Hall, ZPE 73 (1988), 15–18, Inventing the Barbarian, 38–9. The Homeric Phrygians represent a separate allied force (Il. 2.862–3, 3.184–90, 10.431, 16.718–9; cf. h.Ven. 111–16).

33. ‘Span the horn-bound bows with strings.’

ζεύγνυτε κερόδετα τόξα νευραῖς: The verse does not respond with the paradosis at 51 (49–51n.). Emendation here, as was attempted already by Tr1 τόξα <γε> (Diggle, Euripidea, 513), could produce regular syncopated iambics (‸ia ia ia‸), but this is probably not what our poet desired (23–51 ‘Metre’ with 33/51 n.), and there are no other reasons to change the text. Dale’s ζεύγνυτ᾽ εὖ (MATC I, 95) and Willink’s ζεύγνυτ᾽ ὦ (‘Cantica’, 25 = Collected Papers, 564) both interrupt the rhythm after 32 ~ 50, while Ritchie’s τὰ (298) looks unduly specific in an ode that employs the article only where necessary (29 τὸν Εὐρώπας, 49 τὸ μέλλον). The state of 51, on the other hand, is easily explained by simplification of word-order and script.

κερόδετα: a hapax formed after χρυσόδετος (382) and the like. The meaning ‘bound with horn’ (cf. ΣL Rh. 33 [II 328.19–20 Schwartz = 80 Merro] τὰ κερουλκά, τὰ ὑπὸ κεράτων δεδεμένα) refers to the ‘composite’ or ‘Asiatic’ bow, whose stave was fitted with keratin on the inside and sinew on the outside to increase the flexibility, range and penetration of the weapon (Lorimer, Homer and the Monuments, 276–7, 290–2, 298, F. H. Stubbings, in Companion to Homer, 518–20, Snodgrass, Arms and Armour of the Greeks, 39–40). In Homer Pandarus’ bow (Il. 4.105–13) and maybe that of Odysseus (Od. 21.393–5) are meant to be of that type. More clearly Or. 268 δὸς τόξα μοι κερουλκά, δῶρα Λοξίου and, also of the Trojans, S. fr. 859 ϕίλιπποι καὶ κερουλκοί (‘drawing horn-tipped bows’), / σὺν σάκει δὲ κωδωνοκρότῳ παλαισταί (cf. 383–4n.).

34–40. Hector is angry at the lack of solid information. His exclamations and further impatient questions sum up what the audience too will think about the action so far.

34–5. For the antithesis Klyve compares Pers. 215–16 οὔ σε βουλόμεσθα μῆτερ οὔτ᾽ ἄγαν ϕοβεῖν λόγοις / οὔτε θαρσύνειν, which comes immediately after another potential model for our lines (below).

δείματ᾽ ἀκούειν: i.e. the chorus’ frightened call to arms. A final-consecutive infinitive is more frequent with θαῦμα, but note Pers. 210–11 ταῦτ᾽ ἐμοί τε δείματ᾽ ἔστ᾽ ἰδεῖν, / ὑμῖν τ᾽ ἀκούειν and Hdt. 6.112.3 τέως δὲ ἦν τοῖσι Ἕλλησι καὶ τὸ οὔνομα τὸ Μήδων ϕόβος ἀκοῦσαι (KG II 15, SD 364–5).

τὰ δὲ θαρσύνεις: Cf. 16 (Χο.) θάρσει. (Εκ.) θαρσῶ (with 16–19n.).

κοὐδὲν καθαρῶς prefigures 40 οὐδὲν τρανῶς ἀπέδειξας and 77 … οὐκ ἴσμεν τορῶς. Of the three adverbs καθαρῶς comes closest to ordinary Attic speech (LSJ s.v. καθαρός II 4) and in other tragedy occurs only at Hcld. 1055 (with Wilkins on 1053–5, against Barrett’s suspicion of these lines).

36–7a. ‘Why – are you frightened by the scourge of Cronus’ descendant, Pan, which induces trembling fear?’

This is the earliest evidence for Pan being credited with causing ‘panics’ – those sudden, and generally groundless, terrors which could befall an army ‘both at night and in daytime’ (Aen. Tact. 27.1; cf. e.g. Hdt. 4.203.3, Thuc. 4.125.1, Ba. 302–5, Rh. 15, 17–18, 138–9, 691 [nn.], Pritchett, GSW III, 45, 162–3, E. L. Wheeler, GRBS 29 [1988], 153–88, P. Borgeaud, Recherches sur le dieu Pan, Geneva 1979, 137–75 = The Cult of Pan in Ancient Greece, Chicago – London 1988, 88–116, 228–39).238 Our poet cast the thought into the traditional metaphor of the scourge: Il. 12.37 Ἀργεῖοι δὲ Διὸς μάστιγι δαμέντες (with Hainsworth), 13.812 (with Janko on 312–16). Cf. West, EFH 116, Fantuzzi, in I luoghi, 253–4 and on τρομερᾷ / μάστιγι below.

ἀλλ᾽ ἦ: Heath (Notae sive lectiones, 94) for ἀλλ᾽ ἤ (Ω, lΣV [corr. Schwartz]), with which it tends to be confused (GP 28; cf. 560–1n.). ἀλλ᾽ ἦ ‘puts an objection in interrogative form, giving lively expression to a feeling of surprise or incredulity’ (GP 27). It normally introduces a reply, but may also come later, as here, when the thought is developed by the speaker himself (Barrett on Hipp. 858–9).

Κρονίου Πανός: Pan did not have a fixed genealogy in myth (cf. Roscher III.1, 1379–80). With Zeus as his father (Epimenid. 3 B 16 DK = ΣV Rh. 36 [II 329.6–7 Schwartz = 81.6–8 Merro], Σvet. Theoc. 1.3/4 c [28.1–3 Wendel]), Κρόνιος could be παππωνυμικόν (ΣV Rh. 36 [II 329.10 Schwartz = 81.10–11 Merro]), although this is not the ordinary way of referring to gods (unlike e.g. Achilles Αἰακίδης). More probably thus our poet followed a tradition ascribed to Aeschylus that (one of two) Pan(s) was Cronus’ son: ΣV Rh. 36 (II 329.10–11 Schwartz = 81.11–12 Merro) + Σvet. Theoc. 4.62/63 d.e (153.9–12 = 154.4–7 Wendel) = A. fr. 25b (one of the two Glaukoi), S. fr. 136 (Andromeda). In any case the epithet points to the antiquity of the Arcadian god (ΣV Rh. 36 [II 329.8–10 Schwartz = 81.8–10 Merro]). Cf. Wilamowitz, SPrAW IV (1929), 40 = KS V.2, 164.

τρομερᾷ / μάστιγι: In addition to Il. 12.37–8 and 13.812 (above), note Sept. 608 πληγεὶς θεοῦ μάστιγι παγκοίνῳ ᾽δάμη, Ag. 642 διπλῇ μάστιγι, τὴν Ἄρης ϕιλεῖ, PV 682 μάστιγι θείᾳ … ἐλαύνομαι and later Nonn. D. 10.4 οἰστρηθεὶς … μανιώδεϊ Πανὸς ἱμάσθλῃ, 10.13 Πανιάδος Κρονίης … δοῦπος ἱμασθλῆς. For active τρομερός (‘shiver-inducing’) cf. Ar. Av. 950 κλῇσον … τὰν τρομεράν, κρυεράν (sc. πόλιν) and A. R. 4.53 τρομερῷ δ᾽ ὑπὸ δείματι πάλλετο θυμός.

37b–8a. ϕυλακὰς δὲ λιπὼν / κινεῖς στρατιάν was athetised by Dobree (Adversaria II [1833], 87 = IV [1874], 84) as a doublet of 18, and numerous editors have followed him. Yet ‘the abandonment of their posts by the sentinels is prominent in Hector’s mind’ (Porter on 37; cf. 808–19n.), and so is the fear of nocturnal commotion in the camp (15, 17–18, 138–9nn.). Possibly, therefore, the phrase belongs to our poet (e.g. Ammendola on 36–7, D. Ebener, WZRostock 12 [1963], 205, Jouan 9 n. 12), rather than to someone who inserted a marginal note (Klyve on 16–18). A similar repetition in [652] (n.) ~ 279 looks more firmly like an interpolation, while 150 ~ 155 and 543–5 ~ 562–5 are unexceptionable for their literary and dramatic function in the text (149–50, 154–5, 543–5nn.).

38b–40. The words and sentence structure, if not the tone, recall Tro. 153–5 Ἑκάβη, τί θροεῖς; τί δὲ θωΰσσεις; / ποῖ λόγος ἥκει; διὰ γὰρ μελάθρων / ἄιον οἴκτους οὓς οἰκτίζῃ.

οὐδὲν τρανῶς ἀπέδειξας: 34–5n. Strohm (258 n. 3) here quotes Ai. 23 ἴσμεν γὰρ οὐδὲν τρανές, ἀλλ᾽ ἀλώμεθα, where human knowledge is similarly impaired by night (cf. 595–674, 656–60nn., Introduction, 4–5). Unlike its adjective, τρανῶς (‘clearly’) is attested three more times in classical tragedy (Ag. 1371 Eum. 45, E. El. 758).

41–3a. The tell-tale watchfires (1–51, 23–51nn.) are effectfully contrasted with the darkness of night (Klyve on 42–3). For the colometry at 43 see 23–51 ‘Metre’ 25–25a/43–43a n.

41–2. πύρ᾽᾽ αἴθει στρατὸς Ἀργόλας: Cf. 78 τίς γὰρ πύρ᾽ αἴθειν πρόϕασις Ἀργείων στρατόν; and 822–3 (821–3n.) … ὅτε σοι / ἄγγελος  ; and 822-3 (821-3n.) ...

; and 822-3 (821-3n.) ...  / ἦλθον ἀμϕὶ ναῦς πύρ᾽ αἴθειν. Reiske’s πύρ᾽ αἴθει(ν) (Animadversiones, 86) for the ‘false’ compound πυραίθει(ν) (KB II 260, 336–7, Schwyzer 726; cf. 790–1n.) in all three passages is confirmed by O’s πῦρ᾽ αἴθει here, as well as 78 πυρ᾽ αιθειν (Π2) and the double accent in the papyrus of Call. fr. 228.13 Pf. (πύραιθεῖν, corr. Pfeiffer).

/ ἦλθον ἀμϕὶ ναῦς πύρ᾽ αἴθειν. Reiske’s πύρ᾽ αἴθει(ν) (Animadversiones, 86) for the ‘false’ compound πυραίθει(ν) (KB II 260, 336–7, Schwyzer 726; cf. 790–1n.) in all three passages is confirmed by O’s πῦρ᾽ αἴθει here, as well as 78 πυρ᾽ αιθειν (Π2) and the double accent in the papyrus of Call. fr. 228.13 Pf. (πύραιθεῖν, corr. Pfeiffer).

Ἀργόλας: a poetic variant of Ἀργεῖος, also attested in E. fr. 630 and Ar. fr. 311.1 PCG.

Ἕκτορ: 23–4n.

πᾶσαν ἀν᾽ ὄρϕναν: ‘all through the dark night’. The preposition here is essentially local, as at Il. 14.80 οὐ γάρ τις νέμεσις ϕυγέειν κακόν, οὐδ᾽ ἀνὰ νύκτα, with its residue of a quasi-material conception of night: ‘out into the dark’ (R. Dyer, Glotta 52 [1974], 34; cf. 696–8, 774a nn.). This view is reinforced by Il. 8.553–63 (~ 10.11–13), which emphasise the quantity and distribution of the Trojan watchfires (1–51, 23–51nn.) and the way ὄρϕνη tends to denote darkness or obscurity rather than the time of night (e.g. Thgn. 1077–8 ὄρϕνη γὰρ τέταται· πρὸ δὲ τοῦ μέλλοντος ἔσεσθαι / οὐ ξυνετὰ θνητοῖς πείρατ᾽ ἀμηχανίης, Pi. Ol. 1.71, Hcld. 857–8, Ion 955). So Ritchie (181) is rightly critical about classing our phrase as a Homerism only on the basis of ‘temporal’ ἀνὰ νύκτα in Il. 14.80 (A. C. Pearson, CR 35 [1921], 56). For a comparable use of ‘spatial’ ἀνά in Attic he cites Thuc. 3.22.1 ἀνὰ τὸ σκοτεινὸν μὲν οὐ προϊδόντων αὐτῶν (LSJ s.v. ἀνά C I 2, SD 441).

Our poet’s sevenfold use of ὄρϕνη (also 69, 570, 587, 678–9, 697, 774) to stress the fact that is sinisterly dark (Ritchie 218–19) was probably inspired by Il. 10.83, 276, 386 νύκτα δι᾽ ὀρϕναίην (cf. Hainsworth on Il. 10.41). In classical tragedy only Euripides has the word (seven times), and it may be relevant that it also occurs in the ‘Euripidean’ monody at Ar. Ran. 1331 (cf. 662, 750–1a nn. and Introduction, 29–30 with n. 36). The adjective ὀρϕναῖος, however, is found in Ag. 21 (with Fraenkel).

43–3a. ‘… and the mooring places of the ships are gleaming with torches.’

διιπετῆ: a word of uncertain sense and etymology (cf. DELG s.v. διιπετής). Our poet follows Euripides and others who took it to mean ‘bright’, ‘clear’, ‘translucent’: Ba. 1267 (ὁ αἰθὴρ) λαμπρότερος ἢ πρὶν καὶ διιπετέστερος (P, testt.: διει- Elmsley), Hyps. fr. I iv.31 Bond =

E. fr. 752h.31 στατῶν γὰρ ὑδάτων [ν]ά̣ματ᾽ οὐ διειπετῆ and, apparently of fire, E. fr. 815 δμωσὶ<ν> δ᾽ ἐμοῖσιν εἶπον ὡς  / πυρίδες καὶ διηπετῆ

/ πυρίδες καὶ διηπετῆ  (= Erot. δ 27 Nachmanson).239 In Homer it only occurs in the verse-end formula … διιπετέος ποταμοῖο (Il. 16.174, 17.263, 21.268, 326, Od. 4.477, 581, 7.284; cf. ‘Hes.’ fr. 320 M.–W.), where ancient scholars explained it as ‘fallen from Zeus’ (i.e. ‘rain-fed’)240 or, after Euripides, as λαμπρός, διαυγής (e.g. ΣΣAbT Il. 16.174, 17.263 [IV 204.49–205.64, 380.90–2 Erbse], ΣΣ Od. 4.477, 7.284 [II 315.79–317.21 Pontani + I 348.10–11 Dindorf], Hsch. δ 1535, 1784 Latte). Yet it is doubtful whether a dative δι(ε)ι- (= διϝεί) could convey the ablatival notion present in the first definition (cf. later διοπετής: IT 977–8 διοπετὴς … ἄγαλμ᾽, E. fr. 971 ὁ δ᾽ … διοπετὴς ὅπως / ἀστὴρ ἀπέσβη). With an old locative (= διϝί), and the second part derived from πέτομαι instead of πίπτω, we could translate ‘flying in the sky’, although the origin from an Indo-European or Egyptian notion of celestial rivers is again disputed (see recently West, IEPM 350–1, R. Drew Griffith, AJPh 118 [1997], 353–362). In any case, this is how the poet of the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite understood the word (4 οἰωνούς … διιπετέας) and Alcman may have been inspired to the comparison in 3 fr. 3.65–7 PMGF [ἀλλὰ τὸ]ν πυλεῶν᾽ ἔχοισα / [ὥ] τις αἰγλά[ε]ντος ἀστήρ / ὠρανῶ διαιπετής (= *δια-, ‘flying along’: G. O. Hutchinson, Greek Lyric Poetry, Oxford 2001, 109). From that passage and/or possibly a lost one that applied δι(ε)ιπετής to a meteor (~ E. fr. 971 [above]), it is easy to see how the association with ‘brightness’ or ‘clarity’ evolved.

(= Erot. δ 27 Nachmanson).239 In Homer it only occurs in the verse-end formula … διιπετέος ποταμοῖο (Il. 16.174, 17.263, 21.268, 326, Od. 4.477, 581, 7.284; cf. ‘Hes.’ fr. 320 M.–W.), where ancient scholars explained it as ‘fallen from Zeus’ (i.e. ‘rain-fed’)240 or, after Euripides, as λαμπρός, διαυγής (e.g. ΣΣAbT Il. 16.174, 17.263 [IV 204.49–205.64, 380.90–2 Erbse], ΣΣ Od. 4.477, 7.284 [II 315.79–317.21 Pontani + I 348.10–11 Dindorf], Hsch. δ 1535, 1784 Latte). Yet it is doubtful whether a dative δι(ε)ι- (= διϝεί) could convey the ablatival notion present in the first definition (cf. later διοπετής: IT 977–8 διοπετὴς … ἄγαλμ᾽, E. fr. 971 ὁ δ᾽ … διοπετὴς ὅπως / ἀστὴρ ἀπέσβη). With an old locative (= διϝί), and the second part derived from πέτομαι instead of πίπτω, we could translate ‘flying in the sky’, although the origin from an Indo-European or Egyptian notion of celestial rivers is again disputed (see recently West, IEPM 350–1, R. Drew Griffith, AJPh 118 [1997], 353–362). In any case, this is how the poet of the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite understood the word (4 οἰωνούς … διιπετέας) and Alcman may have been inspired to the comparison in 3 fr. 3.65–7 PMGF [ἀλλὰ τὸ]ν πυλεῶν᾽ ἔχοισα / [ὥ] τις αἰγλά[ε]ντος ἀστήρ / ὠρανῶ διαιπετής (= *δια-, ‘flying along’: G. O. Hutchinson, Greek Lyric Poetry, Oxford 2001, 109). From that passage and/or possibly a lost one that applied δι(ε)ιπετής to a meteor (~ E. fr. 971 [above]), it is easy to see how the association with ‘brightness’ or ‘clarity’ evolved.

The spelling διειπετής (Elmsley on Ba. 1266) is found in Hyps. P. Oxy. 852 (II–III AD),241 Hsch. δ 1535 Latte (above) and recommended by the Alexandrian Zenodorus: Porph. ad Il. 16.174 (129.14–16 Sodano), Od. 4.477 (II 48.1–2 Schrader) = Σ Od. 4.477 (II 316.7–8 Pontani) Ζηνόδωρος δὲ διιπετῆ τὸν διαυγῆ ἀποδίδωσι· διὰ τοῦτο καὶ γράϕει διειπετῆ διὰ τῆς ει διϕθόγγου. If it was already current in fifth-century Athens (cf. the genuine dative-compound Διειτρέϕης [LGPN II s.v., Threatte II 230; Ar. Av. 798 (with Dunbar), 1442]), it could be what Euripides and our poet wrote. But the MSS and other evidence favour διι-, which a cautious editor may wish to retain (M. Fantuzzi, BMCR 2006.02.18, on 43).

ναῶν / … σταθμά: like our poet’s favourite  (135b–6n.). ναῶν is correct (25n.).

(135b–6n.). ναῶν is correct (25n.).

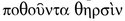

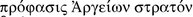

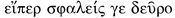

44–8. For the enemy noises (θορύβῳ) that worry the Trojans see 1–51 and 23–51nn. In Il. 9.1–15 the Greeks succumb to Φύζα (Panic), ‘sister of chilling  (2), before Agamemnon calls the host to assembly, and Dolon assumes something like that at Il. 10.325–7

(2), before Agamemnon calls the host to assembly, and Dolon assumes something like that at Il. 10.325–7  γὰρ ἐς στρατὸν

γὰρ ἐς στρατὸν  διαμπερές,

διαμπερές,  ἂν

ἂν  /

/  Ἀγαμεμνονέην, ὅθι που μέλλουσιν

Ἀγαμεμνονέην, ὅθι που μέλλουσιν  βουλεύειν, ἢ ϕευγέμεν

βουλεύειν, ἢ ϕευγέμεν  μάχεσθαι. Our poet may have looked at both passages in transferring his council back to the camp from the open field of Il. 10.194–273.

μάχεσθαι. Our poet may have looked at both passages in transferring his council back to the camp from the open field of Il. 10.194–273.

44–7a. Ἀγαμεμνονίαν: 1n. (πρὸς εὐνὰς τὰς Ἑκτορέους).

προσέβα … / … θορύβῳ: Cf. 15 (n.) …  ϕέρῃ θορύβῳ;

ϕέρῃ θορύβῳ;

νέαν τιν᾽᾽ ἐϕιέμενοι / βάξιν: ‘eager for some new announcement’ or, in view of the accusative instead of the regular genitive object with ἐϕίεμαι, ‘long for, desire’ (LSJ s.v. ἐϕίημι B II 2, SD 105; cf. 300

μαθεῖν), perhaps rather ‘urging some new announcement’ (D. J. Mastronarde, ElectronAnt 8 [2004], 28, Liapis on 44–7). Yet the difference in meaning is slight, and maybe ἐπι- could acquire such force as to demand an accusative, or at least tolerate one, when it suited the metre.242

μαθεῖν), perhaps rather ‘urging some new announcement’ (D. J. Mastronarde, ElectronAnt 8 [2004], 28, Liapis on 44–7). Yet the difference in meaning is slight, and maybe ἐπι- could acquire such force as to demand an accusative, or at least tolerate one, when it suited the metre.242

βάξις is here just ‘speech’, ‘utterance’ (cf. S. fr. 314.371–2 [Ichneutae] στρέϕου,  μύθοις,

μύθοις,  θέλεις / βάξιν

θέλεις / βάξιν  ἀπόψηκτον, S. El. 637–8 [of a prayer], Med. 1374), although perhaps with an air of authority, as from an oracle (Porter on 46, 47, Ammendola on 46).

ἀπόψηκτον, S. El. 637–8 [of a prayer], Med. 1374), although perhaps with an air of authority, as from an oracle (Porter on 46, 47, Ammendola on 46).

48. ναυσιπόρος στρατιά has a near-precedent at Ag. 987  στρατός. But our phrase was probably inspired by IA 171–3 (

στρατός. But our phrase was probably inspired by IA 171–3 ( … )

… )  στρατιὰν

στρατιὰν  ἐσιδοίμαν /

ἐσιδοίμαν /  ναυσιπόρους ἡ- / μιθέων, the only other passage where ναυσιπόρος, ‘seafaring’, occurs and, by extension, also refers to the Greek στρατιά (A. Fries, CQ n.s. 60 [2010], 348; cf. Introduction, 34, 36 and 261–3n.).

ναυσιπόρους ἡ- / μιθέων, the only other passage where ναυσιπόρος, ‘seafaring’, occurs and, by extension, also refers to the Greek στρατιά (A. Fries, CQ n.s. 60 [2010], 348; cf. Introduction, 34, 36 and 261–3n.).

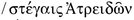

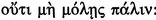

49–51. Fear of royal disapproval is common among tragic messengers (e.g. Ant. 223–43, Ba. 668–71 and especially Sept. 651–2  ἀνδρὶ

ἀνδρὶ  / μέμψῃ). But nowhere are the consequences

so disproportionate to the news. For had the sentries stayed on their posts, the enemy spies could not have entered the Trojan camp.

/ μέμψῃ). But nowhere are the consequences

so disproportionate to the news. For had the sentries stayed on their posts, the enemy spies could not have entered the Trojan camp.

ὑποπτεύων τὸ μέλλον: Cf. 79 (n.) οὐκ οἶδ᾽·  δ᾽ ἐστὶ κάρτ᾽

δ᾽ ἐστὶ κάρτ᾽  ϕρενί. Like its adjective,

ϕρενί. Like its adjective,  is mainly a prose word and otherwise limited to spoken verse: S. El. 43, IT 1036, Epich. fr. 113.10 PCG (cf. [Theoc.] 23.10). Here it suits the character and content of the soldiers’ song.

is mainly a prose word and otherwise limited to spoken verse: S. El. 43, IT 1036, Epich. fr. 113.10 PCG (cf. [Theoc.] 23.10). Here it suits the character and content of the soldiers’ song.

ἤλυθον: The epic aorist appears nowhere in Aeschylus and only once in Sophocles (Ai. 234 [recitative anapaests]), whereas Euripides freely uses it in lyric and sometimes also non-lyric parts: Med. 1108 (recitative anapaests), IA 1339, 1349 (4tr‸), El. 598, Tro. 374, fr. 451.2 (3ia). Cf. Neophr. fr. 1.1 (3ia), Rh. 263 (lyric), 660 (3ia). For the ‘collective’ singular see KG I 85, SD 242–3.

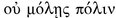

ὡς / μήποτέ τιν᾽ ἐς ἐμὲ μέμψιν εἴπῃς: 23–51 ‘Metre’ 33/51, 33nn. The text of Lindemann (Emendationes, 7) offers ‘slightly [more] agreeable word-divisions’ (Diggle, Studies, 20) than the reconstruction of Musgrave (on 23) and Bothe (5 [1803], 285):  ἐς ἐμέ τινα

ἐς ἐμέ τινα  εἴπῃς. It also accords better with the idea that the transmitted

εἴπῃς. It also accords better with the idea that the transmitted  τινα μέμψιν εἰς ἔμ᾽

τινα μέμψιν εἰς ἔμ᾽  (Π2Δ et Tr1: -εις Λ) arose when

(Π2Δ et Tr1: -εις Λ) arose when  was placed to follow unelided τινα.

was placed to follow unelided τινα.

52–84. After hearing the chorus’ observations, Hector quickly changes his mind about their nocturnal interruption. Oblivious of the rally at Agamemnon’s hut (44–7), he infers that the watchfires must be a trick – one frequently employed by historical generals to win time for retreat under the enemy’s eyes by feigning normal activities in the camp (e.g. Hdt. 4.134.3–135.2, Thuc. 7.80.1–3, Plb. 9.5.7, Jos. AJ 13.178).243 So for different reasons Hector himself comes round to proposing an attack (70–5), and it now falls to the coryphaeus to assume a warning tone in the brief stichomythia that concludes the exchange (76–84).

Much of the material for Hector’s speech stems from that of his epic self at Il. 8.497–541 (53–5, 56–69, 72–3nn.).244 But with subtle changes and allusions to other Iliadic episodes woven in (56–69, 56–8, 60b–2, 65–9, 82–3, 84nn.), our poet adapted it to the new situation and his own idea of the Trojan chief. In contrast to Rhesus, the Homeric Hector graciously gives in to dusk, despite his confidence that he was about to destroy the Achaean ships (Il. 8.498–502, 529–41). The Trojan fires were meant to prevent the enemy from escaping, or to catch them in the attempt and take revenge (Il. 8.507–16). Here their presence on the other side arouses Hector’s suspicion and provokes him to threaten similar measures in related words: 72–5 (72–3n.). One important addition to the speech is the seers, who have persuaded Hector not to prolong fighting into the night. The way he treats them recalls his attitude to Polydamas (56–69, 65–9, 84nn.), shortly before Aeneas assumes the role of this prudent counsellor (85–148n.). For the first time also we see an apparently wise suggestion courting disaster when continued battle would have forestalled the Greek spying attack.

Two other leitmotifs are introduced or reinforced in this passage. Like the seers, Hector’s repeated invocations of ‘god / fate’ and  (56–8, 60b–2, 63–4nn.) prefigure the later ‘intrusions of the supernatural order into our play’ (Rosivach 54–5, 64–5). Moreover, by evoking Zeus and his deceptive support for Troy, they bring out the delusion which lies at the base of Hector’s confidence. So it is fitting that his call to arms takes up that of the unthinking chorus (70–1, 84nn.), while the coryphaeus in giving sound advice falls back on the calm but uncertain message of the antistrophe: 77, 79 (n.).

(56–8, 60b–2, 63–4nn.) prefigure the later ‘intrusions of the supernatural order into our play’ (Rosivach 54–5, 64–5). Moreover, by evoking Zeus and his deceptive support for Troy, they bring out the delusion which lies at the base of Hector’s confidence. So it is fitting that his call to arms takes up that of the unthinking chorus (70–1, 84nn.), while the coryphaeus in giving sound advice falls back on the calm but uncertain message of the antistrophe: 77, 79 (n.).

52. In commending the chorus on their timely arrival, Hector treats them as just the dramatic persona they are (Introduction, 39–40). His words also reflect the topos, usually uttered by the messenger himself, that there is no reward for delivering bad news (Pers. 253 ᾤμοι, κακὸν μὲν

κακά, Ag. 636–49, Ant. 276–7, Phoen. 1214–18, fr. tr. adesp. 122; cf. Andr. 1084, Hec. 511–17). The diction resembles Tro. 238

κακά, Ag. 636–49, Ant. 276–7, Phoen. 1214–18, fr. tr. adesp. 122; cf. Andr. 1084, Hec. 511–17). The diction resembles Tro. 238  καινὸν

καινὸν  λόγον (~ Phoen. [1075]) and Hcld. 656 τί γὰρ

λόγον (~ Phoen. [1075]) and Hcld. 656 τί γὰρ  ϕόβου;

ϕόβου;

ἐς καιρὸν ἥκεις: 10n. The combination of (εἰς) καιρόν with a verb of motion is typical of Euripides (Ritchie 251–2). Π2 confirms  (Chr. Pat. 1870, 2389, 2390), which also has the appropriate ‘resultative’ sense: Tro. 238 (above), Alexis fr. 151.1 PCG, Hyps. fr. 60 i.27 Bond = E. fr. 757.858 (with Bond), E. fr. 495.7–9 (Captive Melanippe)

(Chr. Pat. 1870, 2389, 2390), which also has the appropriate ‘resultative’ sense: Tro. 238 (above), Alexis fr. 151.1 PCG, Hyps. fr. 60 i.27 Bond = E. fr. 757.858 (with Bond), E. fr. 495.7–9 (Captive Melanippe)  δ᾽ … / ἥσθησαν,

δ᾽ … / ἥσθησαν,  θ᾽· ‘εἶα

θ᾽· ‘εἶα  ἄγρα[ς]· / καιρὸν γὰρ ἥκετ᾽’· οὐδ᾽