Ἀχαιοὺς ὡς δοκεῖς ἀναρπάσαι: For  in the sense ‘seize by storm’ or ‘ravage’ (people) see Hdt. 8.28

in the sense ‘seize by storm’ or ‘ravage’ (people) see Hdt. 8.28

9.59.2, Batr. 264

οὗτος

9.59.2, Batr. 264

οὗτος  ἐπαπείλει, D. H. 5.22.3, 5.44.4, 7.4.1 (LSJ s.v.

ἐπαπείλει, D. H. 5.22.3, 5.44.4, 7.4.1 (LSJ s.v.  III).

III).

122. ‘For the man is fiery and of towering boldness.’

The verse combines, and translates into tragic language, Polydamas’ descriptions of Achilles at Il. 13.746

and 18.262

and 18.262

αἴθων γὰρ ἁνήρ: Of the human temperament αἴθων, ‘fiery, burning’, is first attested in Sept. 447–8  … / αἴθων …

… / αἴθων …  and Ai. 221/2 ἀνδρὸς αἴθονος (with Finglass on 221/2–222/3), 1088

and Ai. 221/2 ἀνδρὸς αἴθονος (with Finglass on 221/2–222/3), 1088  all of which could have been in our poet’s mind (cf. Fraenkel, Rev. 231, Hutchinson on Sept. 448). Οne also thinks of the many fire similes that are applied to Homeric heroes, especially perhaps Il. 13.53 (~ 13.330, 688, 17.88, 18.154, 20.423) ϕλογὶ εἴκελος (ἀλκήν) and, of Achilles, Il. 20.371–2

all of which could have been in our poet’s mind (cf. Fraenkel, Rev. 231, Hutchinson on Sept. 448). Οne also thinks of the many fire similes that are applied to Homeric heroes, especially perhaps Il. 13.53 (~ 13.330, 688, 17.88, 18.154, 20.423) ϕλογὶ εἴκελος (ἀλκήν) and, of Achilles, Il. 20.371–2

/ εἰ

/ εἰ

(H. Fränkel, Die homerischen Gleichnisse, Göttingen 1921, 49–52).

(H. Fränkel, Die homerischen Gleichnisse, Göttingen 1921, 49–52).

For the etymology and semantics of  (< αἴθομαι, αἴθω) see O. Levaniouk, HSPh 100 (2000), 25–51 (26–36), who argues convincingly that ‘fiery, burning’ (LSJ s.v. I) takes precedence over all other meanings which have been assigned to the word (LSJ s.v. II of metals: ‘flashing, glittering’, III of animals: ‘red-brown, tawny’).

(< αἴθομαι, αἴθω) see O. Levaniouk, HSPh 100 (2000), 25–51 (26–36), who argues convincingly that ‘fiery, burning’ (LSJ s.v. I) takes precedence over all other meanings which have been assigned to the word (LSJ s.v. II of metals: ‘flashing, glittering’, III of animals: ‘red-brown, tawny’).

καὶ πεπύργωται θράσει: literally ‘and towers in boldness’ (cf. LSJ s.v.  II). The closest parallels are Or. 1567–8 οὗτος σύ … /

II). The closest parallels are Or. 1567–8 οὗτος σύ … /  HF 238 … οἷς

HF 238 … οἷς

(with Bond) and Pers. 192 χἢ μὲν τῇδ᾽ ἐπυργοῦτο στολῇ (of a horse). In all these places ‘lofty pride’ is the predominant notion, although here at least it gives cause for real concern. So Ajax is called a πύργος in Od. 11.556 (~ Callin. fr. 1.18–21 IEG). Cf. A. W. H. Adkins, HSPh 81 (1977), 74 with n. 48, H. Bernsdorff, ZPE 158 (2006), 3 and, for the motif in general, West, IEPM 454–5.

(with Bond) and Pers. 192 χἢ μὲν τῇδ᾽ ἐπυργοῦτο στολῇ (of a horse). In all these places ‘lofty pride’ is the predominant notion, although here at least it gives cause for real concern. So Ajax is called a πύργος in Od. 11.556 (~ Callin. fr. 1.18–21 IEG). Cf. A. W. H. Adkins, HSPh 81 (1977), 74 with n. 48, H. Bernsdorff, ZPE 158 (2006), 3 and, for the motif in general, West, IEPM 454–5.

Murray, Porter1, Zanetto and Jouan read  (VaLgB) on the hypothesis (stated by the first two)271 that

(VaLgB) on the hypothesis (stated by the first two)271 that  intruded from Or. 1568. But the instrumental dative with

intruded from Or. 1568. But the instrumental dative with  always refers to an external ‘force’ (add E. Suppl. 997–8, Ion TrGF 19 F 63.1 and Ar. Pax 749–50 to the examples quoted), and in view also of Il. 18.262 οἷος

always refers to an external ‘force’ (add E. Suppl. 997–8, Ion TrGF 19 F 63.1 and Ar. Pax 749–50 to the examples quoted), and in view also of Il. 18.262 οἷος  (above), our poet would have had no reason to change the phrase. Yet the process of corruption may have been the same, since χερί stands at the end of Or. 1567.

(above), our poet would have had no reason to change the phrase. Yet the process of corruption may have been the same, since χερί stands at the end of Or. 1567.

123–4. ‘No, let us allow the army to sleep quietly by their shields (and rest) from the toils of deadly warfare.’

ἀλλά: 70–1n. Aeneas suggests the exact opposite of Hector’s ‘call for action’.

Cf. 20–2 (n.) οὐκ οἶσθα δορὸς πέλας

Cf. 20–2 (n.) οὐκ οἶσθα δορὸς πέλας  /

/  /

/  and 739–40

and 739–40  Unlike the Thracians in our play (762–9, 792nn.), the Trojans keep their equipment well-ordered and ready for use (cf. Il. 10.75–7, 150–3, 471–3).

Unlike the Thracians in our play (762–9, 792nn.), the Trojans keep their equipment well-ordered and ready for use (cf. Il. 10.75–7, 150–3, 471–3).

ἐκ κόπων ἀρειϕάτων: ‘(to get a rest) from … ’, as implied in εὕδειν. More clearly S. El. 231

For  in tragedy cf. Eum. 913–14

in tragedy cf. Eum. 913–14  … / …

… / …  A. fr. 146b

A. fr. 146b  (~ fr. 147 ἀρείϕατον λῆμα?), E. Suppl. 603–4

(~ fr. 147 ἀρείϕατον λῆμα?), E. Suppl. 603–4  / ϕόνοι and E. fr. 741a ]. .

/ ϕόνοι and E. fr. 741a ]. . [. . . .]

[. . . .] .[. .]

.[. .]

[. Epic ἀρηΐϕατος means ‘slain in war’ (Il. 19.31, 24.415, Od. 11.41, Heraclit. 22 B 24 DK,272 Opp. Hal. 3.562), and while the dramatists used the word almost like ἄρειος (Sideras, Aeschylus Homericus, 50, Collard on E. Suppl. 603–7), we need not suppose that the second element lost all its force. Some association with ‘killing’ probably remained (Porter on 124 [with ‘Addenda et Corrigenda’ (21929), lv], FJW on A. Suppl. 633).

[. Epic ἀρηΐϕατος means ‘slain in war’ (Il. 19.31, 24.415, Od. 11.41, Heraclit. 22 B 24 DK,272 Opp. Hal. 3.562), and while the dramatists used the word almost like ἄρειος (Sideras, Aeschylus Homericus, 50, Collard on E. Suppl. 603–7), we need not suppose that the second element lost all its force. Some association with ‘killing’ probably remained (Porter on 124 [with ‘Addenda et Corrigenda’ (21929), lv], FJW on A. Suppl. 633).

Klyve (on 124) prefers  (Δ) to

(Δ) to  (Λ). The latter indeed appears as a gloss on πόνος and the like (FJW on A. Suppl. 209), but must be the lectio difficilior here. In 763–4 the Thracians are said to have slept

(Λ). The latter indeed appears as a gloss on πόνος and the like (FJW on A. Suppl. 209), but must be the lectio difficilior here. In 763–4 the Thracians are said to have slept  /

/

125–30. On Aeneas’ role in proposing to send out a spy and its relationship to Iliad 10 see 85–148n. In tragedy cf. Sept. 36–8 σκοποὺς

and Hcld. 337–8

and Hcld. 337–8

125–6a. κατάσκοπον δὲ πολεμίων: likewise 140 (n.) … πολεμίων κατάσκοπον and 809 …  (of the Greeks, i.e. with a subjective genitive). Owing mainly to its theme (Ritchie 218), Rhesus has six further cases of

(of the Greeks, i.e. with a subjective genitive). Owing mainly to its theme (Ritchie 218), Rhesus has six further cases of  (129, 505, 524, 592, 645, 657), which, like

(129, 505, 524, 592, 645, 657), which, like  and κατασκοπέω, probably entered later dramatic idiom from prose. Cf. Phil. 45, Hec. 239 (= Rh. 505), Hel. 1607, Ba. 838, 916, 956, 981, fr. tr. adesp. 712.13,273 Lyc. 784, Ar. Thesm. 588 (paratragic), Antiph. fr. 274.2 PCG, Men. Peric. 295 (Pritchett, GSW I, 130, who is wrong to say that

and κατασκοπέω, probably entered later dramatic idiom from prose. Cf. Phil. 45, Hec. 239 (= Rh. 505), Hel. 1607, Ba. 838, 916, 956, 981, fr. tr. adesp. 712.13,273 Lyc. 784, Ar. Thesm. 588 (paratragic), Antiph. fr. 274.2 PCG, Men. Peric. 295 (Pritchett, GSW I, 130, who is wrong to say that  occurs once in Homer).

occurs once in Homer).

126b–7. κἂν μὲν αἴρωνται ϕυγήν: 53–5n. Wecklein in his edition (~ Textkritische Studien, 14) wrote ἄρωνται, but the durative aspect of the present is desired here. The MSS’ ϕυγῇ, corrected by Stephanus (Annotationes, 116), may have arisen after 54 …  Stephanus) or from

Stephanus) or from  in 125.

in 125.

Ἀργείων στρατῷ: 56–8n.

128–30a. ἐς δόλον τιν᾽: Cf. 91–2 …  /

/

ϕρυκτωρία: 53–5n.

ϕρυκτωρία: 53–5n.

130b. τήνδ᾽᾽ ἔχω γνώμην, ἄναξ: Such short, affirmative statements often conclude a speech in drama: e.g. Ag. 582, A. fr. 47a.21 (Diktyoulkoi)

Eum. 710, Or. 1203

Eum. 710, Or. 1203  Phil. 389 λόγος λέλεκται πᾶς, Men. Epitr. 292 εἴρηκα τόν γ᾽ ἐμὸν λόγον (Collard, ‘Supplement’, 376). Cf. Athena at 640

Phil. 389 λόγος λέλεκται πᾶς, Men. Epitr. 292 εἴρηκα τόν γ᾽ ἐμὸν λόγον (Collard, ‘Supplement’, 376). Cf. Athena at 640

O’s  makes no sense here. The phrase fills the same position in Alc. 1107, followed by 1108 νίκα νυν·

makes no sense here. The phrase fills the same position in Alc. 1107, followed by 1108 νίκα νυν·  ἁνδάνοντά μοι ποιεῖς, which shares two words with Rh. 137 νικᾷς,

ἁνδάνοντά μοι ποιεῖς, which shares two words with Rh. 137 νικᾷς,

131–6 ~ 195–200. This is the first of two pairs of separated but responding stanzas in Rhesus. Yet unlike 454–66 ~ 820–32 (n.), which spans nearly half the play, the present pair remains confined to one ‘act’ (85–223). Among other tragic instances of divided song (Hipp. 362–72 ~ 669–79, Or. 1353–65 ~ 1537–48, Phil. 391–402 ~ 507–18, OC 833–43 ~ 876–86),274 the closest in form and function is Phil. 391–402 ~ 505–18, where twice within the long first epeisodion (Phil. 219–675) the chorus support Neoptolemus (cf. Phil. 146–9  /

/  τῶνδ᾽ οὑκ μελάθρων, /

τῶνδ᾽ οὑκ μελάθρων, /

/

/  παρὸν θεραπεύειν). Similarly here the sentries intervene at important stages in the plot (Ritchie 328). With Aeneas’ proposal to dispatch a spy the action is about to take a major turn (85–148n.), and it will be the passionate strophe that tips the scales (131–6, 137–46nn.). The antistrophe, on the other hand, comes when everything is settled (or so it appears). The chorus praise Dolon for his audacity and the glorious reward he has secured. Only a touch of scepticism hints at the disaster ahead (195–200n.).

παρὸν θεραπεύειν). Similarly here the sentries intervene at important stages in the plot (Ritchie 328). With Aeneas’ proposal to dispatch a spy the action is about to take a major turn (85–148n.), and it will be the passionate strophe that tips the scales (131–6, 137–46nn.). The antistrophe, on the other hand, comes when everything is settled (or so it appears). The chorus praise Dolon for his audacity and the glorious reward he has secured. Only a touch of scepticism hints at the disaster ahead (195–200n.).

It is noteworthy, though not surprising, that most separated odes in tragedy belong to the iambo-dochmiac class. Like many astrophic lyrics (‘act-dividing’ or not), their individual stanzas are designed as spontaneous outbursts in response to the preceding scene or speech, and the audience, after hearing the strophe, will not automatically expect an antistrophe to follow later in the play. One partial exception to this ‘rule’ is Rh. 454–66 ~ 820–32, which combines iambo-dochmiacs with a longer dactylo-epitrite run.

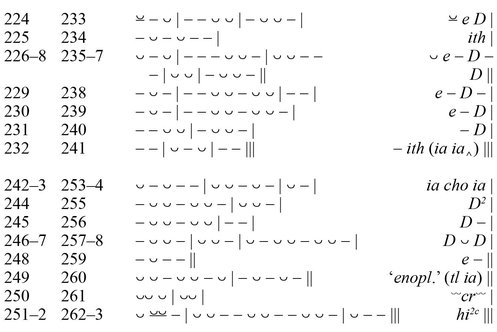

Metre

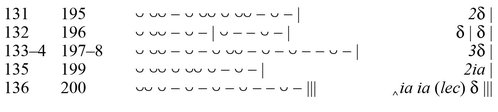

131–6 ~ 195–200. Dochmio-iambic (cf. above). Apart from the slightly unusual verse 131 (131/195n.), the composition is plain, with strict metrical responsion throughout. The two most common forms of dochmiac ( - and

- and  -) predominate.

-) predominate.

Notes

131/195 The strophe (131) has split resolution in the final element of the first dochmiac, which is very rare, especially in forms other than

(L. P. E. Parker, CQ n.s. 18 [1968], 267–8, Diggle, Euripidea, 378 n. 53, with HF 1070, Tro. 253 and maybe Andr. 842). Equally notable, if of less rhythmical import, is the four-syllable ‘overlap’ between the two dochmiacs (τάδε δοκεῖ, τάδε με|ταθέμενος νόει), caused by the long participle and paralleled only at Sept. 692–3 … ἵμερος ἐξοτρύ- / νει

(L. P. E. Parker, CQ n.s. 18 [1968], 267–8, Diggle, Euripidea, 378 n. 53, with HF 1070, Tro. 253 and maybe Andr. 842). Equally notable, if of less rhythmical import, is the four-syllable ‘overlap’ between the two dochmiacs (τάδε δοκεῖ, τάδε με|ταθέμενος νόει), caused by the long participle and paralleled only at Sept. 692–3 … ἵμερος ἐξοτρύ- / νει  Phoen. 176 (though see Diggle’s apparatus and Mastronarde [p. 177]) and again HF 1070

Phoen. 176 (though see Diggle’s apparatus and Mastronarde [p. 177]) and again HF 1070

(making it closest in shape to our line).275

(making it closest in shape to our line).275

The responding word-end after the second long (131 τάδε δοκεῖ | … ~ 195  | …) may be the reason why some have preferred (or envisaged) the analysis ‸ia | lec (cf. Schroeder2 167, Ritchie 299, Dale, MATC III, 150, Zanetto 66). ‘But the sequel should leave us in no doubt that the verse is dochmiac’ (Willink, ‘Cantica’, 26 n. 19 = Collected Papers, 565 n. 19).

| …) may be the reason why some have preferred (or envisaged) the analysis ‸ia | lec (cf. Schroeder2 167, Ritchie 299, Dale, MATC III, 150, Zanetto 66). ‘But the sequel should leave us in no doubt that the verse is dochmiac’ (Willink, ‘Cantica’, 26 n. 19 = Collected Papers, 565 n. 19).

133–4/197–8 The continuous run of dochmiacs makes line-division a mere typographical choice.

135/199 Willink (‘Cantica’, 26 = Collected Papers, 565) calls this a ‘characteristic “sub-dochmiac” iambic dimeter (tolerant of split resolutions) ’. But while cola of the shape  - are indeed frequent with dochmiacs (West, GM 112), nothing invites us to believe that the context would make them more susceptible to ‘splits’. Of the cases Willink cites (also ed. Orestes, 113 and CQ n.s. 49 [1999], 420 = Collected Papers, 289), some are textually suspect or admit of alternative scansions (Sept. 157 ~ 165, Or. 329 ~ 345, 1253 ~ 1273),276 others have no (real) split resolutions at all (Ag. 1091 ~ 1096, Cho. 155, Hipp. 878,277 Hec. 1031, Rh. 693 ~ 711). Moreover, the phenomenon occurs in various surroundings.

- are indeed frequent with dochmiacs (West, GM 112), nothing invites us to believe that the context would make them more susceptible to ‘splits’. Of the cases Willink cites (also ed. Orestes, 113 and CQ n.s. 49 [1999], 420 = Collected Papers, 289), some are textually suspect or admit of alternative scansions (Sept. 157 ~ 165, Or. 329 ~ 345, 1253 ~ 1273),276 others have no (real) split resolutions at all (Ag. 1091 ~ 1096, Cho. 155, Hipp. 878,277 Hec. 1031, Rh. 693 ~ 711). Moreover, the phenomenon occurs in various surroundings.

136/200 The line should be taken as ‸ia ia (lec) δ, not δ ia | ‸ia with Conomis (Hermes 92 [1964], 46), Diggle, Kovacs, Liapis and, hesitantly, Pace (Canti, 24) and Feickert.  - is not unusual (especially in Aeschylus), but never, it seems, ends a stanza or ode. And if the lecythion here is iambic instead of catalectic trochaic (see West, GM 99–100), there is no objection to having it run over in synartesis, as also, against Diggle, at E. El. 1153–4 ~ 1161–2 ‸ia ia (lec)

- is not unusual (especially in Aeschylus), but never, it seems, ends a stanza or ode. And if the lecythion here is iambic instead of catalectic trochaic (see West, GM 99–100), there is no objection to having it run over in synartesis, as also, against Diggle, at E. El. 1153–4 ~ 1161–2 ‸ia ia (lec)  (Willink, ‘Cantica’, 26 = Collected Papers, 565–6). For the clausular dochmiac preceded by 2ia | or lec | cf. Cho. 944–5 and Med. 1281 ~ 1292.

(Willink, ‘Cantica’, 26 = Collected Papers, 565–6). For the clausular dochmiac preceded by 2ia | or lec | cf. Cho. 944–5 and Med. 1281 ~ 1292.

As in Rh. 454–66 ~ 820–32 (p. 293), responsion extends to the wording with a series of structural and/or phonetic echoes, doubtless reflecting musical phrases: 131  … τάδε ~ 195 μέγας … μεγάλα, 134

… τάδε ~ 195 μέγας … μεγάλα, 134  ~ 198

~ 198  136 δαίεται ~ 200 ϕαίνεται. Also, Rh. 131 ~ 195 may be included in the list of examples where word-repetition in dochmiacs does not (quite) follow a specific pattern (Diggle, Euripidea, 296–7, 376–8).278

136 δαίεται ~ 200 ϕαίνεται. Also, Rh. 131 ~ 195 may be included in the list of examples where word-repetition in dochmiacs does not (quite) follow a specific pattern (Diggle, Euripidea, 296–7, 376–8).278

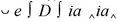

131–6. Like Phil. 391–402 ~ 507–18 and Rh. 454–66, this choral strophe replaces the normal two- or three-trimeter comment after a major speech. As such, it stands out for its bias and the freedom with which the sentries criticise Hector’s judgement. Their lack of deference, especially for a chorus of soldiers, has been considered dramatically superfluous and even a reflection of Macedonian army ἰσηγορία (cf. Introduction, 19, 20; also Liapis on 137). But Hector is bound to accept Aeneas’ plan (or the plot could not return to Iliad 10), and by giving the chorus a vital role, our poet characterises his general as not only rash, but also susceptible to pressure from below (85–148, 137–46nn.). We shall see manifestations of both traits throughout the play.

131. τάδε δοκεῖ, τάδε … νόει: Dawe’s δόκει (apud Diggle) would reinforce the chorus’ appeal (and the linguistic parallelism), but the imperative of this verb usually takes an infinitive construction (e.g. PV 436–7, S. El. 312–13, Alc. 53, Rh. 665, 940; implied at Ar. Thesm. 208), and we should expect a reaction to Aeneas’ speech first. Cf. Liapis, ‘Notes’, 54.

μεταθέμενος: ‘change one’s mind, retract’ (LSJ s.v. μετατίθημι II 4 a). Hn alone is right here against Ω’s  (Introduction, 50). 132. ‘I do not like a general excercising his authority in a way that risks disaster.’

(Introduction, 50). 132. ‘I do not like a general excercising his authority in a way that risks disaster.’

The sentries turn into personal criticism what has been expressed in a gnomic fashion or context at Phoen. 599

E. Suppl. 508–9

E. Suppl. 508–9  / νεώς τε ναύτης (with Collard on 508b–10) and E. fr. 194.3–4 ἐγὼ γὰρ

/ νεώς τε ναύτης (with Collard on 508b–10) and E. fr. 194.3–4 ἐγὼ γὰρ

/

/  . Their exceptional frankness (131–6n.) is reminiscent of Archil. fr. 114 IEG

. Their exceptional frankness (131–6n.) is reminiscent of Archil. fr. 114 IEG

/

/

(where note the verbal overlaps with our passages in the first and fourth line). For another Archilochian echo see 166n.

(where note the verbal overlaps with our passages in the first and fourth line). For another Archilochian echo see 166n.

σϕαλερά: i.e. ‘likely to make one stumble / trip’ (LSJ s.v.  I), since the chorus fear that Hector will lead the army astray (cf. 110–11). But with persons especially it is often difficult to distinguish between this active sense of

I), since the chorus fear that Hector will lead the army astray (cf. 110–11). But with persons especially it is often difficult to distinguish between this active sense of  and the middle-passive ‘ready to fall, uncertain, fallible’ (cf. LSJ s.v. II, III, Stockert on IA 21).

and the middle-passive ‘ready to fall, uncertain, fallible’ (cf. LSJ s.v. II, III, Stockert on IA 21).

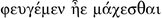

δ᾽᾽ stands for γάρ as not infrequently in poetry and very seldom in prose (GP 169–70). Cf. 182, 618, 626, 635, 647, 852, 965.

comes close to βίη

comes close to βίη  and the like (KG I 280–1): ‘generals in their position of authority’. For κράτος more directly of powerful individuals see 821–3n.

and the like (KG I 280–1): ‘generals in their position of authority’. For κράτος more directly of powerful individuals see 821–3n.

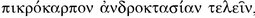

133–6. ‘For what is better than to have a swiftly-pacing spy go near the ships (to see) why the enemy are burning watch-fires in front of their naval station?’

133–5a. ταχυβάταν: a hapax, albeit of regular formation. Cf. A. fr. 280 (Hsch. α 8338 Latte) αὐριβάτας, ‘swift-striding’, Pers. 1072, Bacch. 3.48 ἁβροβάτης, ‘soft-stepping’, and also e.g. [Arist.] Phgn. 813a 7, 9 ταχυβάμων. It may have been in tragic use before Rhesus.

κατόπταν: 631–2n. Given the form, Hsch. κ 1840 Latte

belongs either here or to 557–8 ναῶν / …

belongs either here or to 557–8 ναῶν / …  (Wecklein: -ταν Ω).

(Wecklein: -ταν Ω).

135b–6. ὅτι ποτ᾽ ἄρα … / … δαίεται: The indirect question, which easily attaches to the verbal noun κατόπταν (Porter on 134 ff.), seems to have been inspired by Il. 9.75–7  /

/

(sc.

(sc.

. The particle ἄρα adds a sense of urgency or excitement (GP 39–40, LSJ s.v. B 2).

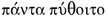

. The particle ἄρα adds a sense of urgency or excitement (GP 39–40, LSJ s.v. B 2).

‘in front of’ or ‘face to face’ (LSJ s.v. ἀντίπρῳρος 2). Compounds with

‘in front of’ or ‘face to face’ (LSJ s.v. ἀντίπρῳρος 2). Compounds with  were often used ‘metaphorically to indicate simply the forward end of something’ (Fraenkel on Ag. 235). Yet in the context here, and despite the fact that ships were drawn ashore stern first, one also recalls the literal meaning, common in the historians, ‘with the prow towards’ (LSJ s.v. 1; cf. Denniston on E. El. 846). For κατά (with accusative), ‘along, opposite’, see LSJ s.v. B I 3, KG I 477–8, SD 473–4 and e.g. Rh. 371, 421 κατ᾽ ὄμμα, 409, 491, 511 κατὰ στόμα.

were often used ‘metaphorically to indicate simply the forward end of something’ (Fraenkel on Ag. 235). Yet in the context here, and despite the fact that ships were drawn ashore stern first, one also recalls the literal meaning, common in the historians, ‘with the prow towards’ (LSJ s.v. 1; cf. Denniston on E. El. 846). For κατά (with accusative), ‘along, opposite’, see LSJ s.v. B I 3, KG I 477–8, SD 473–4 and e.g. Rh. 371, 421 κατ᾽ ὄμμα, 409, 491, 511 κατὰ στόμα.

for the Achaean naval camp recurs in 244, 448, 582, 591, 602 and 673. The accusatives at 244 and 602 prove it to be neuter as in Thuc. 3.6.2 and presumably 6.49.4  δὲ ἐπαναχωρήσαντας. Later a masculine form is attested and the preferences of authors vary. As a technical term the word is otherwise confined to prose.

δὲ ἐπαναχωρήσαντας. Later a masculine form is attested and the preferences of authors vary. As a technical term the word is otherwise confined to prose.

δαίεται: The assonance with δαΐοις is noteworthy (Feickert on 135), particularly since καίεται, after Il. 9.77 (above), would have scanned as well (and was indeed conjectured by Hartung [17 (1852), 123]). It is unclear, however, whether δάϊος and  are related (GEW, DELG s.v. δήιος) and/or whether the ancients saw them that way.

are related (GEW, DELG s.v. δήιος) and/or whether the ancients saw them that way.

137–46. Hector betrays his military weakness by giving in not to Aeneas’ (apparently) sound advice, but to the majority of the ranks (85–148, 131–6nn.). His entire response, moreover, is built on Aeneas’ plan for action (123–30), except that the inverse position and extended treatment of a possible enemy escape (126–7 ~ 143–6) show that this topic is still foremost in his mind. Numerous verbal echoes (140, 141–2, 143–5a, 145b–6nn.) bear further witness to his lack of independent thought.

137. νικᾷς: Bothe (5 [1803], 288) for  (Ω, Chr. Pat. 498). With this very small change, rejected by Zanetto (Feickert) and Jouan,279 our verse becomes an appropriate first reply to Aeneas’ speech (Bothe; cf. M. Fantuzzi, BMCR 2006.02.18, on 137) and largely conforms to the rule that ‘characters do not … allude to what is said in choral odes’ (Stevens, Andromache, 114, who notes OT 216 as an exception). The expression follows E. Suppl. 947–8

(Ω, Chr. Pat. 498). With this very small change, rejected by Zanetto (Feickert) and Jouan,279 our verse becomes an appropriate first reply to Aeneas’ speech (Bothe; cf. M. Fantuzzi, BMCR 2006.02.18, on 137) and largely conforms to the rule that ‘characters do not … allude to what is said in choral odes’ (Stevens, Andromache, 114, who notes OT 216 as an exception). The expression follows E. Suppl. 947–8

γὰρ εὖ / Θησεύς and Hyps. fr. 20/21.13 Bond = E. fr. 754b.13

γὰρ εὖ / Θησεύς and Hyps. fr. 20/21.13 Bond = E. fr. 754b.13

(init. suppl. Wilamowitz). In both these passages the speaker gracefully concedes a point after brief discussion, which throws into even sharper relief the bathos in Hector’s change of mind.

(init. suppl. Wilamowitz). In both these passages the speaker gracefully concedes a point after brief discussion, which throws into even sharper relief the bathos in Hector’s change of mind.

‘since everybody agrees on this.’ The verb brings out the contrast with Il. 12.80 = 13.748

‘since everybody agrees on this.’ The verb brings out the contrast with Il. 12.80 = 13.748  ,

,  (105–30n.).

(105–30n.).  of collective opinion seems to be Herodotean: 4.145.5

of collective opinion seems to be Herodotean: 4.145.5  δὲ ἕαδε

δὲ ἕαδε

, 4.153, 4.201.2, 6.106.3, 9.19.1 (LSJ s.v.

, 4.153, 4.201.2, 6.106.3, 9.19.1 (LSJ s.v.  II with Suppl. [1996], where Hdt. 7.172.1 and 9.5.2 belong under I).

II with Suppl. [1996], where Hdt. 7.172.1 and 9.5.2 belong under I).

138–9. Hector remains preoccupied with the idea that the army could have been disturbed by their nocturnal assembly (17–18, 87–9nn.). Fear of creating a commotion recurs in ‘Arist.’ fr. 159.9–12 Rose (Aporemata Homerica)280 as one reason why at Il. 10.194–253 the Greek chiefs meet outside the wall (cf. Fantuzzi, in I luoghi, 254–5 and Ancient Scholarship, 49–53, who improbably advocates a common source for Rhesus and ‘Aristotle’).

κοίμα: Pierson (Verisimilium I, 81).  (

( Va) is wrongly defended by Ammendola (on 138–9), Ebener (WZRostock 12 [1963], 205) and Zanetto (Ciclope, Reso, 139). As at 662

Va) is wrongly defended by Ammendola (on 138–9), Ebener (WZRostock 12 [1963], 205) and Zanetto (Ciclope, Reso, 139). As at 662

(Δ: κοσμ- Λ), the idea of ‘putting to rest, calming’ is needed here, and κοσμέω in a military context generally means ‘order’ or ‘marshal’ troops (LSJ s.v. I 1, Liapis on 138–9). The error may be a simple misreading or an unconscious alteration to a more common phrase.

(Δ: κοσμ- Λ), the idea of ‘putting to rest, calming’ is needed here, and κοσμέω in a military context generally means ‘order’ or ‘marshal’ troops (LSJ s.v. I 1, Liapis on 138–9). The error may be a simple misreading or an unconscious alteration to a more common phrase.

τάχ᾽ ἂν στρατός / κινοῖτ᾽᾽: 17–18n.

140. πέμψω πολεμίων κατάσκοπον: Cf. 125–6 κατάσκοπον δὲ  … / πέμπειν δοκεῖ μοι (137–46nn.). For κατάσκοπος see 125–6a n.

… / πέμπειν δοκεῖ μοι (137–46nn.). For κατάσκοπος see 125–6a n.

141–2. ‘And if we learn of some trick on the enemy’s part, you will hear everything and be present to know the report.’

κἂν μέν τιν᾽ ἔχθρων μηχανὴν πυθώμεθα resumes 129 μαθόντες  (137–46nn.).

(137–46nn.).

πάντ᾽ ἀκούσῃ καὶ παρὼν εἴσῃ λόγον: a somewhat tautological variation on the idea that first-hand knowledge is preferable to a later report: Pers. 266–7 καὶ

πάντ᾽ ἀκούσῃ καὶ παρὼν εἴσῃ λόγον: a somewhat tautological variation on the idea that first-hand knowledge is preferable to a later report: Pers. 266–7 καὶ  γε κοὐ

γε κοὐ  /… ϕράσαιμ᾽ ἄν (with Garvie), Cho. 851–4 (Diggle, Euripidea, 81 n. 60). The participle

/… ϕράσαιμ᾽ ἄν (with Garvie), Cho. 851–4 (Diggle, Euripidea, 81 n. 60). The participle  in such cases nearly equals αὐτός, which may or may not also be present (P. von der Mühll, MH 19 [1962], 202–3). Cf. 179 (n.) καὶ

in such cases nearly equals αὐτός, which may or may not also be present (P. von der Mühll, MH 19 [1962], 202–3). Cf. 179 (n.) καὶ  γ᾽ αὐτὸς αἱρήσῃ παρών.

γ᾽ αὐτὸς αἱρήσῃ παρών.

Almost the reverse formulation is found at 640–1 (n.) … ὃν δὲ χρὴ παθεῖν / οὐκ οἶδεν οὐδ᾽ ἤκουσεν ἐγγὺς  λόγου.

λόγου.

λόγον: i.e. the spy’s report. λόγους (Δ) perhaps goes back to a scribe who thought of the following ‘deliberations’ (cf. Liapis on 140–2).

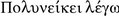

143–5a. ‘But if they are rushing off in flight and put to sea, listen out, expecting the trumpet to sound, since I shall not wait.’

ἐὰν δ᾽᾽ ἀπαίρωσ᾽ ἐς ϕυγὴν ὁρμώμενοι: Cf. 126 … κἂν

(137–46n.). ἐς

(137–46n.). ἐς  here goes with ὁρμώμενοι, as in e.g. Hdt. 7.179 προϊδόντες δὲ οὗτοι τὰς νέας τῶν

here goes with ὁρμώμενοι, as in e.g. Hdt. 7.179 προϊδόντες δὲ οὗτοι τὰς νέας τῶν  ἐς

ἐς  ὥρμησαν, Thuc. 3.112.5, Xen. HG 5.3.2 and Tim. Pers. fr. 791.173–5 PMG = Hordern ὁ δὲ …

ὥρμησαν, Thuc. 3.112.5, Xen. HG 5.3.2 and Tim. Pers. fr. 791.173–5 PMG = Hordern ὁ δὲ …  ἐσ- /

ἐσ- /  Βασιλεὺς εἰς

Βασιλεὺς εἰς  ὁρ- /

ὁρ- /  στρατόν.

στρατόν.

σάλπιγγος αὐδὴν προσδοκῶν καραδόκει: so also Hector at 988–9a (n.) πανοὺς δ᾽ ἔχοντας  μένειν Τυρσηνικῆς /

μένειν Τυρσηνικῆς /  αὐδήν. In tragedy the use of the σάλπιγξ to sound the charge or to call the Athenians to assembly (Eum. 567–70) is transferred to the Heroic Age, although ΣAbT Il. 18.219 (IV 474.17–20, 475.36–7, 40–2 Erbse) and ΣAGeT Il. 21.388 (V 216.30–217.35 Erbse) correctly observe that Homer does not grant his own knowledge of the instrument to his characters (West, Ancient Greek Music, 119; cf. P. Krentz, in V. D. Hanson [ed.], Hoplites: The Classical Greek Battle Experience, London – New York 1991, 113, 115–6).

αὐδήν. In tragedy the use of the σάλπιγξ to sound the charge or to call the Athenians to assembly (Eum. 567–70) is transferred to the Heroic Age, although ΣAbT Il. 18.219 (IV 474.17–20, 475.36–7, 40–2 Erbse) and ΣAGeT Il. 21.388 (V 216.30–217.35 Erbse) correctly observe that Homer does not grant his own knowledge of the instrument to his characters (West, Ancient Greek Music, 119; cf. P. Krentz, in V. D. Hanson [ed.], Hoplites: The Classical Greek Battle Experience, London – New York 1991, 113, 115–6).

rarely refers to ‘sounds other than the human voice’ (Liapis on 143–5). But the trumpet’s signal just replaces a verbal call to arms.

καραδόκει: ‘wait for’ (< κάρα +  , ‘receive with outstretched head’?). The verb is frequent in Euripides (never Aeschylus or Sophocles), both in this neutral sense and with the extended notion of ‘waiting for the outcome of (e.g. a battle) before deciding how to proceed’ (LSJ s.v., Mastronarde on Med. 1117). The wording here resembles Med. 1116–17 ϕίλαι, πάλαι τοι προσμένουσα

, ‘receive with outstretched head’?). The verb is frequent in Euripides (never Aeschylus or Sophocles), both in this neutral sense and with the extended notion of ‘waiting for the outcome of (e.g. a battle) before deciding how to proceed’ (LSJ s.v., Mastronarde on Med. 1117). The wording here resembles Med. 1116–17 ϕίλαι, πάλαι τοι προσμένουσα  / καραδοκῶ

/ καραδοκῶ

and Hel. 739–40

and Hel. 739–40  ἐμοὺς

ἐμοὺς  /

/  οἳ μένουσί μ᾽.

οἳ μένουσί μ᾽.

ὡς οὐ μενοῦντά μ᾽: For the accusative absolute with ‘subjective’  and the participle of a non-impersonal verb see KG II 95–6, SD 402–3. Unequivocal tragic parallels are rare: OT 100–1 ἀνδρηλατοῦντας,

and the participle of a non-impersonal verb see KG II 95–6, SD 402–3. Unequivocal tragic parallels are rare: OT 100–1 ἀνδρηλατοῦντας,

/ λύοντας,

/ λύοντας,  χειμάζον πόλιν, Ion 964–5 σοὶ δ᾽ ἐς

χειμάζον πόλιν, Ion 964–5 σοὶ δ᾽ ἐς  δόξ᾽

δόξ᾽  τέκνον; / –

τέκνον; / –  θεὸν

θεὸν

γ᾽

γ᾽  γόνον, Phoen. 1461–2

γόνον, Phoen. 1461–2  ἐμόν, / οἳ δ᾽

ἐμόν, / οἳ δ᾽  ἐκεῖνον. S. El. 882 (with Finglass) and Phoen. 714 (with Mastronarde) allow other analyses, while OC 380–1 and Hcld. 693 are corrupt (Ll-J/W, Sophoclea, 227–9, Second Thoughts, 120–1,281 Diggle, Euripidea, 225–6, Wilkins on Hcld. 693).

ἐκεῖνον. S. El. 882 (with Finglass) and Phoen. 714 (with Mastronarde) allow other analyses, while OC 380–1 and Hcld. 693 are corrupt (Ll-J/W, Sophoclea, 227–9, Second Thoughts, 120–1,281 Diggle, Euripidea, 225–6, Wilkins on Hcld. 693).

145b–6. Hector just expands on Aeneas at 127

(137–46n.).

(137–46n.).

προσμείξω: ‘I will go close up to (their slipways)’: Thuc. 3.22.1  προσέμειξαν

προσέμειξαν  πολεμίων, 7.70.2 ἐπειδὴ δὲ οἱ

πολεμίων, 7.70.2 ἐπειδὴ δὲ οἱ

(LSJ s.v.

(LSJ s.v.  II 3). Murray restored the classical -μείξ- for -μίξ- (LSJ s.v.

II 3). Murray restored the classical -μείξ- for -μίξ- (LSJ s.v.  A I [morphology], West, ed. Aeschylus, XLVIII, Threatte II, 623–4).

A I [morphology], West, ed. Aeschylus, XLVIII, Threatte II, 623–4).

νεῶν /  : similarly 673 (672b–3a n.)

: similarly 673 (672b–3a n.)  ναυστάθμων. The

ναυστάθμων. The  were channels or stone slips for drawing up or launching ships, not ‘windlasses’, as in LSJ s.v. I 1. Cf. Hdt. 2.154.5

were channels or stone slips for drawing up or launching ships, not ‘windlasses’, as in LSJ s.v. I 1. Cf. Hdt. 2.154.5  δὲ

δὲ  χώρων ἐν

χώρων ἐν  δὴ οἵ

δὴ οἵ  νεῶν …

νεῶν …  μέχρι

μέχρι  ἦσαν, 2.159.1, Thuc. 3.15.1 καὶ

ἦσαν, 2.159.1, Thuc. 3.15.1 καὶ  παρεσκεύαζον

παρεσκεύαζον  ἐν

ἐν  ἐκ

ἐκ  Κορίνθου ἐς τὴν

Κορίνθου ἐς τὴν  θάλασσαν, A. R. 1.375 ἐν δ᾽

θάλασσαν, A. R. 1.375 ἐν δ᾽  ξεστὰς

ξεστὰς  ϕάλαγγας, and see L. Casson, Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World, Princeton 11971, Baltimore – London 21995, 363–4. In Il. 2.153 the οὐροί (‘trenches, channels’) must be cleared out before the ships can be put to sea again.

ϕάλαγγας, and see L. Casson, Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World, Princeton 11971, Baltimore – London 21995, 363–4. In Il. 2.153 the οὐροί (‘trenches, channels’) must be cleared out before the ships can be put to sea again.

ἐπ᾽ Ἀργείων στρατῷ: 56–8n. Both  with dative (Δ) and with accusative (Λ) can be used ‘in hostile sense’ (LSJ s.v. B I 1 c, C I 4, KG I 503, 505, SD 468, 470), but the former is expected when the goal of motion has already been specified with νεῶν / ὁλκοῖσι.

with dative (Δ) and with accusative (Λ) can be used ‘in hostile sense’ (LSJ s.v. B I 1 c, C I 4, KG I 503, 505, SD 468, 470), but the former is expected when the goal of motion has already been specified with νεῶν / ὁλκοῖσι.

147–8. νῦν γὰρ ἀσϕαλῶς ϕρονεῖς harks back to 132. Strohm (259) compares the rather more chilling Ba. 924 (Dionysus to Pentheus) … νῦν δ᾽ ὁρᾷς ἃ  σ᾽ ὁρᾶν.

σ᾽ ὁρᾶν.

δ᾽᾽ ἔμ᾽: The implied contrast with Hector favours the emphatic pronoun (Bothe [II (1826), 90], Chr. Pat. 1932 pars codd.) over the enclitic δέ μ᾽ (Ω, Chr. Pat. 1932 codd. pler.). See Feickert on 148 and, for the use of the different forms in general, KG I 557, SD 186–7.

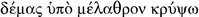

149–94. After Aeneas’ departure, Hector asks for a volunteer to spy on the Greeks (149–53). Dolon agrees on the condition that he be given a suitable reward (154–63). The following dialogue (164–83) reveals that Achilles’ horses are the object of his desire. Hector politely grants the wish, although he himself had set an eye on the splendid pair (184–94).

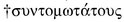

Together with 201–23 (n.) the scene dramatises Hector’s assembly in Il. 10.299–337. Several points and expressions have direct equivalents in the epic (149–50, 154–5, 156–7a, 186, 189b–90nn.), while at the same time our poet adapted the material to suit his own literary and theatrical needs (cf. Ritchie 67). Most importantly, Dolon himself here raises the subject of a reward (161–2a, 162b–3nn.). In that way, he gives a clearer impression of being driven by gain (although Hector admits that he is only demanding his due), and his request initiates the elaborate ‘guessing-game’ (below), which like a priamel leads up to his fantastic goal (182–3n.). Hector, by contrast, advertises the expedition as a patriotic service (151, 152–3nn.). This new motif – developed perhaps from Il. 10.421–2  γὰρ ἐπιτραπέουσι ϕυλάσσειν· / οὐ γάρ σϕιν παῖδες σχεδὸν εἵαται οὐδὲ

γὰρ ἐπιτραπέουσι ϕυλάσσειν· / οὐ γάρ σϕιν παῖδες σχεδὸν εἵαται οὐδὲ  (Strohm 259, 265)282 – helps to elevate not only his own status and that of the mission, but also Dolon’s compared to Iliad 10. Before we notice his mercenary streak, a natural ability for

(Strohm 259, 265)282 – helps to elevate not only his own status and that of the mission, but also Dolon’s compared to Iliad 10. Before we notice his mercenary streak, a natural ability for  (as reflected in his name) and ‘love for his city’ replace mere swiftness (Il. 10.316

(as reflected in his name) and ‘love for his city’ replace mere swiftness (Il. 10.316  ποδώκης) as qualifications for the undertaking (158–9a n.). In addition, our poet has suppressed the potentially prejudicial fact that he was the only son among five sisters (Il. 10.317),283 while keeping allusions to his father’s nobility and wealth (159b–60, 169–70, 170, 178nn.). One wonders whether his ugliness (Il. 10.316) was represented by the mask (Jouan, XXIX).

ποδώκης) as qualifications for the undertaking (158–9a n.). In addition, our poet has suppressed the potentially prejudicial fact that he was the only son among five sisters (Il. 10.317),283 while keeping allusions to his father’s nobility and wealth (159b–60, 169–70, 170, 178nn.). One wonders whether his ugliness (Il. 10.316) was represented by the mask (Jouan, XXIX).

Characterisation by way of Homeric reminiscence continues in the negotiations about the reward. They are modelled on the proxy exchange between Agamemnon and Achilles in Il. 9.115–61 / 225–306 / 308–429, where the latter is offered and rejects in turn gold (Rh. 169–70, 170, 178nn.), treasures (171–2n.), spoils (171–2, 179nn.), a royal bride (167– 8, 167nn.) and political power short of the king’s position (165–6n.). Both quarrel and contestants lack the Iliadic dimensions, but Hector shows himself a ‘better Agamemnon’ for being able to subordinate his desire for Achilles’ horses (184n.) to the benefit of Troy (M. Fantuzzi, in I luoghi, 260–1; cf. R. S. Bond, AJPh 117 [1996], 258).284 The ‘guessing-game’ itself is more familiar from comedy than extant tragedy (e.g. Ar. Ach. 414–31, Vesp. 71–88, Ran. 52–67) as a means of playing with the audience’s expectations and keeping them in suspense as to the actual result.285

The scene therefore serves a dual purpose. It has powerful stage-effects and offers a more balanced picture of Hector and Dolon than Il. 10.299–337. They are not equals (167–8n.), but neither is Dolon wholly debased, nor does Hector live up to his Homeric self. The comparison with Iliad 9 also reduces to proportion the Trojan aspirations for that night. A scouting mission will not win the war, and Dolon in particular overrates himself.

Two questions of stagecraft are of interest here: 1. Where does Dolon come from? and 2. Does Hector stay or leave after 194?

The first can confidently be answered in favour of an entry by an eisodos. To have Dolon present already as part of Hector’s silent retinue would lead to a procedure unparalleled in Greek drama (Ritchie 113–14; cf. J. P. Poe, Philologus 148 [2004], 26). ‘Minor characters do not step out of their anonymity just like that, as it were, in order to become a well-defined dramatis persona for one short scene’ (Kannicht on Hel. 1621–41 [p. 423]). In Helen this is one of several arguments against the introduction of a male servant instead of the chorus-leader (L) to bar Theoclymenus’ way into the palace (1626–41), and Danaus in A. Suppl. 1–176, Cassandra in Ag. 810–1072 and Alcestis’ son in Alc. 233–393, all of whom could have been identified before they are named or speak, do not support such a practice either (contrary to Liapis on 154 ff.; cf. S. Perris, G&R 59 [2012], 157–8).

A conventional side-entry, by contrast, presents no serious problems. Hector’s words can easily be imagined to reach the backstage area, which to the audience’s right represents the Trojan camp (Ritchie 114–

15). His initial appeal at 149–50 (n.)  ἐν λόγῳ / θέλει … μολεῖν; resembles that of Apollo for help with searching his stolen cattle at S. fr. 314.39–40 (Ichneutae)

ἐν λόγῳ / θέλει … μολεῖν; resembles that of Apollo for help with searching his stolen cattle at S. fr. 314.39–40 (Ichneutae)

/ μαριλοκαυ]τῶν ἐν λόγῳ παρ[ίσταται (suppl. Diggle, Wilamowitz).286 After four more lines Silenus, followed by the satyr-chorus (63), bursts in. Similarly, Hector’s repetitions here may partly be designed to give Dolon time to arrive. Even for slower eisodos entries five to seven lines seem to have sufficed, if the newcomer was already becoming visible during the call and spoke his first words before reaching centre-stage. Note HF 514–19 (with Bond), Hyps. fr. 60 i.16–21 Bond = E. fr. 757.847–52 and Ar. Ach. 566–72 (with Olson, lxix). There remains the slight peculiarity of an entry just after another major character (i.e. Aeneas) exited within the same epeisodion. Poe (Philologus 148 [2004], 30) compares Ai. 989 / 1047, Phil. 1260 / 1263 and Or. 716 / 729,287 the last two in late-fifth-century plays and with equally few intervening lines. Our poet also used the device for Paris’ surprise appearance at 642 (595–641n.; cf. O. P. Taplin, GRBS 12 [1971], 41–2 n. 38).

/ μαριλοκαυ]τῶν ἐν λόγῳ παρ[ίσταται (suppl. Diggle, Wilamowitz).286 After four more lines Silenus, followed by the satyr-chorus (63), bursts in. Similarly, Hector’s repetitions here may partly be designed to give Dolon time to arrive. Even for slower eisodos entries five to seven lines seem to have sufficed, if the newcomer was already becoming visible during the call and spoke his first words before reaching centre-stage. Note HF 514–19 (with Bond), Hyps. fr. 60 i.16–21 Bond = E. fr. 757.847–52 and Ar. Ach. 566–72 (with Olson, lxix). There remains the slight peculiarity of an entry just after another major character (i.e. Aeneas) exited within the same epeisodion. Poe (Philologus 148 [2004], 30) compares Ai. 989 / 1047, Phil. 1260 / 1263 and Or. 716 / 729,287 the last two in late-fifth-century plays and with equally few intervening lines. Our poet also used the device for Paris’ surprise appearance at 642 (595–641n.; cf. O. P. Taplin, GRBS 12 [1971], 41–2 n. 38).

With 190 Hector falls silent until he is addressed by the Shepherd in 264. The text gives no sign of a departure (J. P. Poe, Philologus 148 [2004], 27–8) and, unlike at 526, he has no off-stage business to attend to. From a dramaturgical perspective it is also desirable that he should stay. All messages and arrivals in Rhesus are directed at Hector’s εὐναί, except that, for good or ill, he misses the first three in the second half (Strohm 264–5, 269–70). This long-term contrast would be spoilt if after an unmotivated exit he had to return just in time to hear the news of Rhesus’ approach. That simultaneous entries from different directions are rare and usually better accounted for (Taplin, Stagecraft, 148–9, 177 with n. 1) is perhaps less relevant in an author who with the alternative solution too seems to have sacrificed convention to theatrical effect.

For Hector’s long silence Ritchie (117) adduces Hcld. 720–83 (Alcmena), E. Suppl. 381–512 + 513b–733 (Adrastus), HF 252–331 (Lycus), 1214–1404 (Amphitryon) and Phoen. 1356–1583 (Creon). The first bears some resemblance to our case as Alcmena watches the ancient Iolaus being led into battle (720–47), remains for the choral song (748–83) and then immediately receives the Messenger from the field (784–891). But only Phoen. 1356–1583 is similarly ill-rooted in the dramatic action. Creon fades into complete oblivion while the Messenger gives his report to the chorus and Antigone and Oedipus sing their lament. It is likely therefore that his presence in 1308–1581 (at least) was interpolated by someone able to tolerate the formal awkwardness for the pathos of bringing Menoeceus’ grieving father on stage (Fraenkel, Zu den Phoenissen, 71–86).288 If a fourth-century audience was more indulgent in this respect, our poet may have had his choice. Hector momentarily recedes to the margin so as to be in place when required again. The little choral strophe in 195–200 probably helped to structure the rearrangement of characters in the acting space (cf. Taplin, Stagecraft, 52–3).

149–53. Our poet has reduced Il. 10.303–12 to the simple question for a volunteer (149–94n.). Hector’s threefold repetition (with anaphoric τίς) and the growing impatience he betrays in 152–3 (n.) perhaps mirror the Trojans’ reserve at Il. 10.313 ὣς  ἐγένοντο

ἐγένοντο  (Ritchie 67). The lines also cover (part of) Dolon’s way onto stage (149–94n. [p. 175]).

(Ritchie 67). The lines also cover (part of) Dolon’s way onto stage (149–94n. [p. 175]).

149–50. Hector’s initial appeal corresponds almost exactly to Il. 10.303  κέν μοι τόδε

κέν μοι τόδε  + 307–8 ὅς

+ 307–8 ὅς  κε

κε  … / νηῶν

… / νηῶν  σχεδὸν ἐλθέμεν ἔκ

σχεδὸν ἐλθέμεν ἔκ  πυθέσθαι. And as in Il. 10.319–20 Ἕκτορ, ἔμ᾽

πυθέσθαι. And as in Il. 10.319–20 Ἕκτορ, ἔμ᾽  κραδίη καὶ

κραδίη καὶ  /

/  σχεδὸν ἐλθέμεν ἔκ

σχεδὸν ἐλθέμεν ἔκ  πυθέσθαι, the central words are resumed by Dolon in 154–5 (n.).

πυθέσθαι, the central words are resumed by Dolon in 154–5 (n.).

τίς δῆτα: For this use of  see GP 270. The particle ‘denotes that the question springs out of something which another person (or, more rarely, the speaker himself) has just said’ (GP 269).

see GP 270. The particle ‘denotes that the question springs out of something which another person (or, more rarely, the speaker himself) has just said’ (GP 269).

οἳ πάρεισιν ἐν λόγῳ: ‘who are at hand to hear my words’, as at S. fr. 314.39–40 (cited in 149–94n. [p. 175]), Ar. Ach. 513 …  γὰρ οἱ

γὰρ οἱ  ἐν λόγῳ, Av. 30 …

ἐν λόγῳ, Av. 30 …  οἱ

οἱ  ἐν

ἐν  (LSJ Suppl. [1996] s.v. λόγος VI 3 a) and, similarly, Rh. 641 (640–1n.) … ἐγγὺς ὢν λόγου. The parallels support

(LSJ Suppl. [1996] s.v. λόγος VI 3 a) and, similarly, Rh. 641 (640–1n.) … ἐγγὺς ὢν λόγου. The parallels support  (ΔQ) against

(ΔQ) against  (LQ1s) and by their distribution suggest that the idiom has colloquial roots (A. Meschini, in Scritti Diano, 217). Confusion of

(LQ1s) and by their distribution suggest that the idiom has colloquial roots (A. Meschini, in Scritti Diano, 217). Confusion of  and

and  , found in the reverse sense in 682 (n.), was particularly easy in the context here, and with Hector’s unit already mentioned in 26.

, found in the reverse sense in 682 (n.), was particularly easy in the context here, and with Hector’s unit already mentioned in 26.

κατόπτης: 631–2n.

ναῦς ἔπ᾽ Ἀργείων μολεῖν: Cf. 155, 221, 589 and, with different verbs, 203 …  ναῦς

ναῦς  Ἀργείων πόδα, 502 …

Ἀργείων πόδα, 502 …  ναῦς

ναῦς  Ἀργείων

ϕέρει. The juncture comes from Tro. 954 (

Ἀργείων

ϕέρει. The juncture comes from Tro. 954 ( …)

…)  οἴκους ναῦς

οἴκους ναῦς  (~ Andr. 401 αὐτὴ δὲ

(~ Andr. 401 αὐτὴ δὲ  ναῦς

ναῦς  ἔβην) and could, in Rhesus at least, be an attempt to reproduce the Iliadic (θοὰς / κοίλας) ἐπὶ

ἔβην) and could, in Rhesus at least, be an attempt to reproduce the Iliadic (θοὰς / κοίλας) ἐπὶ  (cf. Fenik, Iliad X, 27–8 n. 1).

(cf. Fenik, Iliad X, 27–8 n. 1).

151. τῆσδε γῆς εὐεργέτης: The patriotic motivation to the spying mission is new (149–94n.) and much invoked in the course of this scene (152–3, 154–5, 157b, 158–9a, 230b, 242–4a nn.). Of the dramatists, Euripides was especially fond of  / -ις and εὐεργετέω.

/ -ις and εὐεργετέω.

152–3. Apart from giving Dolon time to appear (149–94, 149–53nn.), Hector’s outburst at the lack of volunteers characterises him again as hot-tempered and prone to ill-conceived responses (as if he was expected to go reconnoitring himself!). He remains a long way from the heroic leader of the Iliad.

πόλει πατρῴᾳ συμμάχοις θ᾽᾽ ὑπηρετεῖν: 149–94, 151nn.

154–5. ‘I am willing to run this risk for our land and to go as a spy to the Argive ships.’

ἐγὼ … θέλω / … κατόπτης ναῦς ἔπ᾽ Ἀργείων μολεῖν: 149–50n. The repetition and choice of words imitate epic formular style. For  see 631–2nn.

see 631–2nn.

πρὸ γαίας: likewise Ion 278 and E. fr. 360.39 (of human sacrifice). Dolon soon abandons patriotism and openly asks for a ‘worthy reward’.

τόνδε κίνδυνον … / ῥίψας: a dicing metaphor (cf. ΣV Rh. 155 [II 331.17–18 Schwartz = 85 Merro] προκινδυνεύσας.

μεταϕορά and e.g. Phryn. PS 29.1–2 de Borries, Phot. κ 733 Theodoridis),289 as also in 183 (182–3n.)

μεταϕορά and e.g. Phryn. PS 29.1–2 de Borries, Phot. κ 733 Theodoridis),289 as also in 183 (182–3n.)  ἐν

ἐν

and 445b–6 (n.) …

and 445b–6 (n.) …  δ᾽

δ᾽  ἡμέρας /

ἡμέρας /

Ἀργείους Ἄρη. The formulation here has equivalents in Hcld. 148–9

Ἀργείους Ἄρη. The formulation here has equivalents in Hcld. 148–9  κίνδυνον

κίνδυνον  ἀμηχάνων / ῥίπτοντες, E. fr. 402.6–7 κίνδυνον μέγαν /

ἀμηχάνων / ῥίπτοντες, E. fr. 402.6–7 κίνδυνον μέγαν /  and Xen. Mem. 1.3.9

and Xen. Mem. 1.3.9  … ῥιψοκινδύνων. Similarly, Sept. [1028]

… ῥιψοκινδύνων. Similarly, Sept. [1028]  κἀνὰ κίνδυνον βαλῶ. Prose authors seem to prefer

κἀνὰ κίνδυνον βαλῶ. Prose authors seem to prefer  (LSJ s.v. II).

(LSJ s.v. II).

156–7a. Dolon’s confidence resembles Il. 10.324–7 σοὶ δ᾽ ἐγὼ οὐχ  ἔσσομαι οὐδ᾽

ἔσσομαι οὐδ᾽  δόξης· /

δόξης· /  γὰρ ἐς

γὰρ ἐς  εἶμι διαμπερές,

εἶμι διαμπερές,  ἂν

ἂν  /

/  Ἀγαμεμνονέην, ὅθι

Ἀγαμεμνονέην, ὅθι  μέλλουσιν

μέλλουσιν  /

/  βουλεύειν, ἢ

βουλεύειν, ἢ  (~ Il. 10.307–12), although the phrasing is closer to Il. 10.211–12 (Nestor)

(~ Il. 10.307–12), although the phrasing is closer to Il. 10.211–12 (Nestor)

καὶ

καὶ  εἰς

εἰς  / ἀσκηθής.

/ ἀσκηθής.

157b. ‘It is on these conditions that I take upon myself this task.’

᾽πὶ τούτοις sums up Dolon’s part of the promise (i.e. that he will undertake the expedition for his land and not return until he has learnt all he can) and thus ‘already establishes the basis for a contract’ (Jouan 61 n. 39). This notion is lost if, with Liapis (on 156–7), we take ἐπί as an indication ‘of an end or purpose’ (LSJ s.v. B III 2).

ὑϕίσταμαι πόνον: In a different martial context cf. E. Suppl. 188–9

ὑϕίσταμαι πόνον: In a different martial context cf. E. Suppl. 188–9  δὲ σή /

δὲ σή /  δύναιτ᾽ ἂν τόνδ᾽ ὑποστῆναι πόνον and 344–5 ὅθ᾽

δύναιτ᾽ ἂν τόνδ᾽ ὑποστῆναι πόνον and 344–5 ὅθ᾽  … /

… /  κελεύεις τόνδ᾽ ὑποστῆναι πόνον.

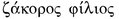

κελεύεις τόνδ᾽ ὑποστῆναι πόνον.

158–9a. ‘You are well named indeed, and you love your city, Dolon.’

Hector’s etymological pun is an unusual way of identifying a new character who has not been named. ‘Dolon’ implies δόλος, which not only makes him an ideal choice as a spy, but also suggests that he was at some point invented for that role (cf. Hainsworth on Il. 10.314, Rh. 201–23n.). On the ancient belief that a name reflects, or should reflect, the nature of its bearer see Dodds on Ba. 367, M. Griffith, HSPh 82 (1978), 84 n. 5 and on PV 85–6, Garvie on Pers. 65–72.

ἐπώνυμος μὲν κάρτα adapts Sept. 658  δὲ κάρτα,

δὲ κάρτα,  (~ Eum. 90 … κάρτα δ᾽ ὢν ἐπώνυμος). But the expression is typical of name-etymologies from Homer on (LSJ s.v. ἐπώνυμος I 1). In tragedy see also e.g. Sept. 405, 829–31, A. Suppl. 45–8 (νῦν δ᾽ ἐπικεκλομένα …)

(~ Eum. 90 … κάρτα δ᾽ ὢν ἐπώνυμος). But the expression is typical of name-etymologies from Homer on (LSJ s.v. ἐπώνυμος I 1). In tragedy see also e.g. Sept. 405, 829–31, A. Suppl. 45–8 (νῦν δ᾽ ἐπικεκλομένα …)  δ᾽ ἐπεκραίνετο μόρσιμος

δ᾽ ἐπεκραίνετο μόρσιμος  /

/  δ᾽ ἐγέννασεν (with FJW on 45 [II, pp. 43–5]), PV 848–51, Ai. 430–1, S. fr. 965, Phoen. 636–7, E. fr. 696.11–13. The practice became something of a mannerism – to the point that it attracted comic parody: Ar. Ran. 1192, frr. 342 PCG (~ E. fr. 182), 373 PCG (~ IT 32–3) and perhaps Anaxil. fr. 35 PCG (Rau, Paratragodia, 210–11, Kannicht on Hel. 13–5).

δ᾽ ἐγέννασεν (with FJW on 45 [II, pp. 43–5]), PV 848–51, Ai. 430–1, S. fr. 965, Phoen. 636–7, E. fr. 696.11–13. The practice became something of a mannerism – to the point that it attracted comic parody: Ar. Ran. 1192, frr. 342 PCG (~ E. fr. 182), 373 PCG (~ IT 32–3) and perhaps Anaxil. fr. 35 PCG (Rau, Paratragodia, 210–11, Kannicht on Hel. 13–5).

κάρτα (79n.) emphasises the appropriateness of the etymology, as do words like ὀρθῶς,  and εὐλόγως elsewhere (W. Headlam, On Editing Aeschylus. A Criticism, London 1891, 140–3, Diggle on Phaeth. 225 [p. 146], Collard on E. Suppl. 496–7a).

and εὐλόγως elsewhere (W. Headlam, On Editing Aeschylus. A Criticism, London 1891, 140–3, Diggle on Phaeth. 225 [p. 146], Collard on E. Suppl. 496–7a).

ϕιλόπτολις: See 149–94, 151nn. and, on ϕιλόπ(τ)ολις as a fifth- and fourth-century term of praise, Liapis on 158–60.

Epic -πτολις stands metri causa, always in the nominative or accusative singular, and in iambo-trochaic dialogue at the end of the line. The same applies to πτόλις, which does not occur in Sophocles (Page on Med. 641, FJW on A. Suppl. 699).

159b–60. Dolon’s reputable descent comes from Il. 10.314–15 (~ 378–81), where he is the son of the wealthy herald Eumedes. It would have been pointless to hint at the less favourable details (149–94n.), although our poet lowered the ‘Homeric’ standard (Il. 10.212–13, 307) by having Hector promise enhanced εὔκλεια for volunteering alone. At 197 the chorus more adequately speak of a  … εὐκλεής.

… εὐκλεής.

δὶς τόσως … εὐκλεέστερον: ‘twice as glorious’. Cf. Rh. 281 ἔγνως·  δὲ

δὲ  μ᾽ ἐκούϕισας, 757b (n.) … καίτοι

μ᾽ ἐκούϕισας, 757b (n.) … καίτοι  κακὸν

κακὸν  and especially Med. 1193–4 πῦρ δ᾽ … / … μᾶλλον δὶς τόσως ἐλάμπετο (with Mastronarde on 1194). Unlike Aeschylus, Euripides ap

and especially Med. 1193–4 πῦρ δ᾽ … / … μᾶλλον δὶς τόσως ἐλάμπετο (with Mastronarde on 1194). Unlike Aeschylus, Euripides ap  (with Mastronarde on 1194). Unlike Aeschylus, Euripides appears to have avoided using τόσος or τόσως without δίς (cf. Cyc. 147, Med. 1047, 1134, Hcld. 293, Hec. 392, El. 1092, fr. 995).290 This may also be true of Sophocles’ trimeters, if one can tell from a single instance (Ai. 277 δὶς τόσ᾽ … κακά) as against one other in lyrics (Ai. 184 τόσσον).

(with Mastronarde on 1194). Unlike Aeschylus, Euripides appears to have avoided using τόσος or τόσως without δίς (cf. Cyc. 147, Med. 1047, 1134, Hcld. 293, Hec. 392, El. 1092, fr. 995).290 This may also be true of Sophocles’ trimeters, if one can tell from a single instance (Ai. 277 δὶς τόσ᾽ … κακά) as against one other in lyrics (Ai. 184 τόσσον).

161–2a. ‘Well, ought one not to undertake a task and in undertaking it win a worthy reward?’

As Dolon is best seen to move from the general to the specific, the expression should not personally be referred to him with  (OΛgVgB, Chr. Pat. 1964) for μέν (V). The syntax resembles IT 810 οὔκουν

(OΛgVgB, Chr. Pat. 1964) for μέν (V). The syntax resembles IT 810 οὔκουν  μὲν

μὲν  σέ, μανθάνειν δ᾽ ἐμέ; and Phoen. 979 οὔκουν σὲ ϕράζειν εἰκός,

σέ, μανθάνειν δ᾽ ἐμέ; and Phoen. 979 οὔκουν σὲ ϕράζειν εἰκός,  δ᾽ ἐμέ;

δ᾽ ἐμέ;

οὔκουν: Denniston (GP 436). The MSS have  as introducing a statement (‘surely, then …’), which does not readily follow the previous sentence and, in any case, is too tame for Dolon here. Between interrogative

as introducing a statement (‘surely, then …’), which does not readily follow the previous sentence and, in any case, is too tame for Dolon here. Between interrogative  and οὔκουν, the latter is livelier and, with a few exceptions, perhaps to be restored in drama thoughout (GP 430–6). Likewise 481, 543, 585, 633.

and οὔκουν, the latter is livelier and, with a few exceptions, perhaps to be restored in drama thoughout (GP 430–6). Likewise 481, 543, 585, 633.

ἄξιον / μισθὸν ϕέρεσθαι: Cf. Il. 10.304 (Hector speaking)

οἱ ἄρκιος ἔσται and Rh. 182 (Dolon) χρὴ δ᾽ ἐπ᾽ ἀξίοις πονεῖν.

οἱ ἄρκιος ἔσται and Rh. 182 (Dolon) χρὴ δ᾽ ἐπ᾽ ἀξίοις πονεῖν.

162b–3. ‘For the profit attached to every action doubles (literally 162b-3. ‘For the profit attached to every action doubles (literally ‘generates as double’) the satisfaction.’

This is how most scholars understand the text. Dolon accepts εὔκλεια as one benefit to be gained from the spying expedition, but, as becomes clear in 182–3 (n.), he really just wants a material reward. His mercenary attitude and desire for the biggest possible gift tell against Palmer (CR 4 [1890], 229), Porter (on 163) and Pearson (CQ 11 [1917], 57–8), who see here an appeal for mutual recognition and translate χάριν with ‘favour’. Yet Pearson correctly noted the linguistic similarity to passages like Ai. 522 χάρις χάριν γάρ ἐστιν  τίκτουσ᾽ ἀεί, OT 231–2 τὸ γάρ / κέρδος

τίκτουσ᾽ ἀεί, OT 231–2 τὸ γάρ / κέρδος  χάρις

χάρις  and OC 1483–4 μηδ᾽

and OC 1483–4 μηδ᾽  ἄνδρ᾽ ἰδὼν / ἀκερδῆ χάριν μετάσχοιμί πως. Perhaps our poet was inspired by such topical formulations and used them to somewhat startling effect.

Or he genuinely wished Dolon to sound ambiguous in an attempt to win Hector to his course.291

ἄνδρ᾽ ἰδὼν / ἀκερδῆ χάριν μετάσχοιμί πως. Perhaps our poet was inspired by such topical formulations and used them to somewhat startling effect.

Or he genuinely wished Dolon to sound ambiguous in an attempt to win Hector to his course.291

τίκτει: Apart from Ai. 522 (above), cf. Sept. 437 καὶ τῷδε  κέρδος

κέρδος  τίκτεται.

τίκτεται.

164. κοὐκ ἄλλως λέγω: ‘… and I do not deny it’. Cf. Rh. 271 … οὐκ  λέγω, Hec. 302, E. El. 1035, Hel. 1106, Or. 709 and also Sept. 490 … οὐκ ἄλλως ἐρῶ, E. El. 226 … καὶ τάχ᾽ οὐκ ἄλλως ἐρεῖς. Euripides’ predilection for this phrase is reflected in Ar. Ran. 1140 (‘Aeschylus’ to ‘Euripides’) … οὐκ

λέγω, Hec. 302, E. El. 1035, Hel. 1106, Or. 709 and also Sept. 490 … οὐκ ἄλλως ἐρῶ, E. El. 226 … καὶ τάχ᾽ οὐκ ἄλλως ἐρεῖς. Euripides’ predilection for this phrase is reflected in Ar. Ran. 1140 (‘Aeschylus’ to ‘Euripides’) … οὐκ  (Ritchie 206–7, who adds Ar. Eccl. 440 …

(Ritchie 206–7, who adds Ar. Eccl. 440 …  δὲ

δὲ  ἄλλως λέγει;). Cf. Introduction, 30 n. 36.

ἄλλως λέγει;). Cf. Introduction, 30 n. 36.

The parallels tell against Nauck’s … κοὐκ  (II1 [1854], XXII), for which he relied on Chr. Pat. 1620 ναὶ

(II1 [1854], XXII), for which he relied on Chr. Pat. 1620 ναὶ  δίκαιον τοῦτο, κοὐκ

δίκαιον τοῦτο, κοὐκ  and 1968 … κοὐκ

and 1968 … κοὐκ  .292 Hector should utter a strong affirmation, not politely agree with his interlocutor (‘Yes … and your words are not beside the point’). Likewise 271 (λέγω O:

.292 Hector should utter a strong affirmation, not politely agree with his interlocutor (‘Yes … and your words are not beside the point’). Likewise 271 (λέγω O:  VΛ).

VΛ).

165–6. Hector instantly excludes the (unrealistic) prize of his royal power (3 8 8–9n.).293 In the negotiations of Il. 9.121–61 / 260–99 / 378–92 (cf. 149–94n.), Agamemnon finally offers Achilles a provincial kingdom (Il. 9.149–56) before admonishing him to respect his higher rank (160–1). Odysseus wisely omits this condition (291–9), although Achilles exploits the point in rejecting a princess bride: Il. 9.388–92 ~ Rh. 168 (167–8n.). Cf. R. S. Bond, AJPh 117 (1996), 257–8.

165. δέ: for οὖν or  (GP 170), as in Ba. 1118–20

(GP 170), as in Ba. 1118–20  τοι, μῆτερ, εἰμί,

τοι, μῆτερ, εἰμί,  σέθεν /

σέθεν /  … / οἴκτιρε

… / οἴκτιρε  με.

με.

πλὴν ἐμῆς τυραννίδος: Nauck (II1 [1854], XXII ~ Euripideische Studien II, 170) offered πλὴν  τυραννίδα on the analogy of 173 …

τυραννίδα on the analogy of 173 …  δ᾽ αἴτει πλὴν στρατηλάτας νεῶν. But there the accusative is more natural as ‘the implied object of

δ᾽ αἴτει πλὴν στρατηλάτας νεῶν. But there the accusative is more natural as ‘the implied object of  (Liapis, ‘Notes’, 55). And we need not avoid the repetition with τυραννίδος in 166.

(Liapis, ‘Notes’, 55). And we need not avoid the repetition with τυραννίδος in 166.

166. οὐ σῆς ἐρῶμεν … τυραννίδος: For the wording cf. Archil. fr. 19.3 IEG … μεγάλης δ᾽ οὐκ ἐρέω τυραννίδος. See also 132n.

: ‘… which guards the city’. The adjective recurs in 821 (Chorus to Hector)  ἐμοὶ μέγας

ἐμοὶ μέγας  (Vater: πολιοῦχον Ω), where it retains part of its association with tutelary deities (821–3n.). Here this notion is uniquely transferred to the abstract

τυραννίς. Feickert (on 166) suspects an allusion to Hector’s name, which since antiquity has been connected with ἔχω, ‘hold, rule, keep safe’ (von Kamptz, Homerische Personennamen, 26, 171, 261–2, Wathelet, Dictionnaire des Troyens I, 472, II, 1304–5). Cf. Pl. Crat. 393a1–b6 and the play on Athena

(Vater: πολιοῦχον Ω), where it retains part of its association with tutelary deities (821–3n.). Here this notion is uniquely transferred to the abstract

τυραννίς. Feickert (on 166) suspects an allusion to Hector’s name, which since antiquity has been connected with ἔχω, ‘hold, rule, keep safe’ (von Kamptz, Homerische Personennamen, 26, 171, 261–2, Wathelet, Dictionnaire des Troyens I, 472, II, 1304–5). Cf. Pl. Crat. 393a1–b6 and the play on Athena  at Ar. Thesm. 1136–41

at Ar. Thesm. 1136–41  … 1140

… 1140  ἔχει / καὶ κράτος

ἔχει / καὶ κράτος  μόνη.

μόνη.

Outside Rhesus, the form  for

for  (here V:

(here V:  L) is attested in Pi. Dith. 4 fr. 70d.38–9 Sn.–M. [καὶ

L) is attested in Pi. Dith. 4 fr. 70d.38–9 Sn.–M. [καὶ  Γλαυ- /

Γλαυ- /  and Inscr. Cret. 4.171.14 (III BC). On

and Inscr. Cret. 4.171.14 (III BC). On  and

and  as proper names see LGPN II s.vv. and G. Pace, QUCC n.s. 65 (2000), 131 n. 19.

as proper names see LGPN II s.vv. and G. Pace, QUCC n.s. 65 (2000), 131 n. 19.

167–8. At Il. 9.141–8 ~ 283–90 Agamemnon promises Achilles one of his three daughters in wedlock, but the latter refuses with the deeply ironic suggestion that Agamemnon look for someone ‘more princely’ (βασιλεύτερος) than himself: Il. 9.388–92. The idea that one should not marry above one’s station is a commonplace for both men and women (e.g. Alcm. fr. 1.16–17 PMGF, Pi. Pyth. 2.34–6, PV 887–93, S. fr. 353, E. El. 930–7, E. frr. 214, 502) and gives Dolon an elegant excuse to reject Hector’s offer (Feickert on 168). In 197–8 (n.) the chorus will doubt the wisdom of demanding Achilles’ horses instead.

167. ‘Well then, marry and become related to Priam’s family.’

σὺ δ᾽ ἀλλά opens a fresh proposal (of equal merit). Formally, δ᾽  ‘is always followed by an imperative … and nearly always preceded by σύ’ (GP 10).

‘is always followed by an imperative … and nearly always preceded by σύ’ (GP 10).

Πριαμιδῶν γαμβρὸς γενοῦ: Cf. Il. 9.142 (Agamemnon speaking)  κέν μοι ἔοι and 284 (Odysseus)

κέν μοι ἔοι and 284 (Odysseus)  κέν οἱ ἔοις (167–8n.). In our passage

κέν οἱ ἔοις (167–8n.). In our passage  need not mean more than ‘relative by marriage’ (Liapis on 167).

need not mean more than ‘relative by marriage’ (Liapis on 167).

168. ἐξ ἐμαυτοῦ μειζόνων γαμεῖν: ‘to take a wife of nobler stock than myself’. Cf. Thgn. 189–90 καὶ ἐκ κακοῦ  / καὶ κακὸς ἐξ ἀγαθοῦ and especially Andr. 1279

/ καὶ κακὸς ἐξ ἀγαθοῦ and especially Andr. 1279  οὐ

οὐ  ἔκ

ἔκ

,294 Xen. Hier. 1.28

,294 Xen. Hier. 1.28  …

…  ἐκ

ἐκ  (LSJ s.v.

(LSJ s.v.  I 1). With

I 1). With  or

or  also e.g. Hcld. [299], Andr. 974–5, Or. 1676–7, Pl. Plt. 310c 10.

also e.g. Hcld. [299], Andr. 974–5, Or. 1676–7, Pl. Plt. 310c 10.

169–70. ‘Ten talents of gold’ are among the treasures that Agamemnon initially offers to give Achilles: Il. 9.122b, 126 = 264b, 268 (cf. Il. 19.247). In his response to Odysseus, the hero summarily dismisses all material gifts (Il. 9.378–87) and insinuates that he and his family themselves are rich (Il. 9.364–7, 400). On the wealth of Dolon’s father see 149–94, 159b–60, 170nn.

169. χρυσὸς πάρεστιν (Δ) must be read. Λ’s χρυσὸς γὰρ ἔστιν arose by confusion of Π and Γ, and Zanetto is wrong to take it as lectio difficilior on the assumption that with γάρ Hector expresses his assent: ‘Yes, you are right to refuse to marry above your station; but if you want gold, you only need to ask for it’ (Ciclope, Reso, 140 n. 22). If we render the paradosis by Denniston’s simple ‘Not, for … ’ (GP 73–4), the lack of connection with Dolon’s statement becomes obvious.

εἰ τόδ᾽᾽ αἰτήσεις γέρας: similarly 181 τί  μεῖζον τῶνδέ μ᾽

μεῖζον τῶνδέ μ᾽  γέρας;

γέρας;

170. ἀλλ᾽ ἔστ᾽ ἐν οἴκοις: ‘No, I have gold at home’, with  simply expressing opposition (GP 7). For the fact cf. Il. 10.378–9 ἔστι γὰρ ἔνδον /

simply expressing opposition (GP 7). For the fact cf. Il. 10.378–9 ἔστι γὰρ ἔνδον /  τε χρυσός τε

τε χρυσός τε  τε σίδηρος and for the language Rh. 178 ἔστι χρυσὸς ἐν δόμοις.

τε σίδηρος and for the language Rh. 178 ἔστι χρυσὸς ἐν δόμοις.

οὐ βίου σπανίζομεν: The expression is ordinary Greek (e.g. Hdt. 1.196.5), but may here have a Euripidean ring: E. Suppl. 240 οἱ δ᾽ …  βίου, El. 235

βίου, El. 235  τοῦ

τοῦ  βίου; E. fr. 285.11–12, Hec. 11–12 ἵν᾽ … /

βίου; E. fr. 285.11–12, Hec. 11–12 ἵν᾽ … /  βίου. In other tragedy only OT 1460–1 ἄνδρες εἰσίν, ὥστε μὴ /

βίου. In other tragedy only OT 1460–1 ἄνδρες εἰσίν, ὥστε μὴ /  σχεῖν … τοῦ βίου. The words σπάνις,

σχεῖν … τοῦ βίου. The words σπάνις,  and

and  are on the whole much rarer (or non-existent) in Aeschylus and Sophocles than in Euripides.

are on the whole much rarer (or non-existent) in Aeschylus and Sophocles than in Euripides.

is the first of several instances of the vitium Byzantinum in that MS (Introduction 49 n. 7).

171–2. Hector’s new question perhaps corresponds to the other valuables (tripods, cauldrons, prize-winning horses) Agamemnon has in store for Achilles (Il. 9.122a, 123–4 = 264a, 265–6). In Agamemnon’s speech this is followed by the promise of spoils (Il. 9.135–40 ~ 277–82), a topic which Dolon himself raises as the first explicit step to his desired reward (149–94n.).

171. τί δῆτα: 149–50n.

ὧν κέκευθεν  presumably echoes Il. 22.118

presumably echoes Il. 22.118  … ὅσα τε

… ὅσα τε  κέκευθεν, where Hector considers surrendering Helen, the goods Paris stole and half of Troy’s wealth (~ Il. 18.511–12).

κέκευθεν, where Hector considers surrendering Helen, the goods Paris stole and half of Troy’s wealth (~ Il. 18.511–12).  (OQ), not

(OQ), not  (VL), is the preferred tragic form, except in the epicising Andr. 103 (LSJ s.v.

(VL), is the preferred tragic form, except in the epicising Andr. 103 (LSJ s.v.  I, Diggle, Euripidea, 324 n. 9). For κέκευθε(ν) see also 620b–1n.

I, Diggle, Euripidea, 324 n. 9). For κέκευθε(ν) see also 620b–1n.

172. ξυναίνεσον: ‘promise, grant’. Cf. Ag. 483–4 γυναικὸς αἰχμᾷ  /

/  χάριν ξυναινέσαι (with Fraenkel on 484), Xen. An. 7.7.31 οἱ δὲ

χάριν ξυναινέσαι (with Fraenkel on 484), Xen. An. 7.7.31 οἱ δὲ  διὰ τὸ δεῖσθαι

διὰ τὸ δεῖσθαι  στρατιᾶς

στρατιᾶς  αὐτοῖς ταῦτα, Cyr. 8.5.20 (LSJ s.v. συναινέω 2). Our passage provides a particularly good example of how the basic meaning of the verb, ‘agree with, consent’ (LSJ s.v. 1), develops when the action responds to a request (H. L. Ahrens, Philologus Suppl. 1 [1860], 532).

αὐτοῖς ταῦτα, Cyr. 8.5.20 (LSJ s.v. συναινέω 2). Our passage provides a particularly good example of how the basic meaning of the verb, ‘agree with, consent’ (LSJ s.v. 1), develops when the action responds to a request (H. L. Ahrens, Philologus Suppl. 1 [1860], 532).

173.  στρατηλάτας νεῶν: 165n. Here πάντα is omitted as an ‘antecedent’ to πλήν, as in e.g. OT 118 θνῄσκουσι γάρ, πλὴν εἷς τις and 369–70 (Τε.)

στρατηλάτας νεῶν: 165n. Here πάντα is omitted as an ‘antecedent’ to πλήν, as in e.g. OT 118 θνῄσκουσι γάρ, πλὴν εἷς τις and 369–70 (Τε.)  τί γ᾽ ἐστὶ τῆς

τί γ᾽ ἐστὶ τῆς  σθένος. / (Οι.)

σθένος. / (Οι.)  ἔστι,

ἔστι,  σοί. The Greek commanders could fetch enormous ransoms: 177 (n.).

σοί. The Greek commanders could fetch enormous ransoms: 177 (n.).

174. ‘Kill them. I do not demand that you keep your hand off Menelaus. ’

Dolon may understand Hector’s motive to be primarily vengeance, but given his aim, the reply looks more like another rejection of conventional wealth. Thus at 176 (n.) he cannot seriously believe that high-ranking captives should work the fields.

Both syntax and verse-rhythm recall E. Suppl. 385  σ᾽

σ᾽  χάριν

χάριν  νεκρούς.

νεκρούς.

Μενέλεω σχέσθαι χέρα: For metrical reasons the simplex  replaces

replaces  in this common phrase (Od. 22.316

in this common phrase (Od. 22.316  μοι οὐ πείθοντο

μοι οὐ πείθοντο  χεῖρας ἔχεσθαι, Emp. 31 B 141 DK, A. Suppl. 755–6 οὐ

χεῖρας ἔχεσθαι, Emp. 31 B 141 DK, A. Suppl. 755–6 οὐ  … / …

… / …  χεῖρ᾽ ἀπόσχωνται, πάτερ, Eum. 350, Antiph. fr. 27.16 PCG, Crates Com. fr. 19.2 PCG, Pl. Smp. 213d3–4, 214d3–4). χέρα (Δ), rather than χέρας (Λ), connotes a powerful martial blow.

χεῖρ᾽ ἀπόσχωνται, πάτερ, Eum. 350, Antiph. fr. 27.16 PCG, Crates Com. fr. 19.2 PCG, Pl. Smp. 213d3–4, 214d3–4). χέρα (Δ), rather than χέρας (Λ), connotes a powerful martial blow.

175. οὐ μήν (‘Surely … not … ?’) ‘introduces, tentatively and half incredulously, an alternative suggestion’ (GP 334). Likewise Alc. 518 οὐ  γ᾽ ὄλωλεν Ἄλκηστις σέθεν;

γ᾽ ὄλωλεν Ἄλκηστις σέθεν;

τὸν  παῖδα: the ‘lesser’ Ajax.

παῖδα: the ‘lesser’ Ajax.  (V:

(V:  O) is preferable to

O) is preferable to  (Λ ὀϊλ-). Diggle, among recent editors, followed by Kovacs and (for Rhesus) Jouan, adopts the latter both here and at IA 193 and 263 (ὀϊλ- L). But the contraction of Homeric Ὀῑλ- (<

(Λ ὀϊλ-). Diggle, among recent editors, followed by Kovacs and (for Rhesus) Jouan, adopts the latter both here and at IA 193 and 263 (ὀϊλ- L). But the contraction of Homeric Ὀῑλ- (<  -) into Οἰλ- is odd and significantly perhaps not attested by our MSS. As in Pi. Ol. 9.112 Αἶαν …

-) into Οἰλ- is odd and significantly perhaps not attested by our MSS. As in Pi. Ol. 9.112 Αἶαν …  (v.l. ὀϊλ-), their epicising and unmetrical Ὀϊλέως is the likely response of scribes not familiar with the form in

(v.l. ὀϊλ-), their epicising and unmetrical Ὀϊλέως is the likely response of scribes not familiar with the form in  (also <

(also <  ). This further occurs in the Iliou Persis (Arg. p. 146 (1) GEF),295 ‘Hes.’ fr. 235.1 M.–W., Stes. fr. 226 PMGF and Lyc. 1150 and probably gained some currency in pre-Aristarchean Iliadic texts (cf. Nickau, Zenodotos, 36–42). The tragedians then had ample precedent for a variant of cretic or spondaic shape and no need to create one of their own. Fantuzzi (CPh 100 [2005], 272–3) is inconsistent when he defends

). This further occurs in the Iliou Persis (Arg. p. 146 (1) GEF),295 ‘Hes.’ fr. 235.1 M.–W., Stes. fr. 226 PMGF and Lyc. 1150 and probably gained some currency in pre-Aristarchean Iliadic texts (cf. Nickau, Zenodotos, 36–42). The tragedians then had ample precedent for a variant of cretic or spondaic shape and no need to create one of their own. Fantuzzi (CPh 100 [2005], 272–3) is inconsistent when he defends  here, but does not equally strongly support the conjecture

here, but does not equally strongly support the conjecture  by England and Wilamowitz (GV 283 n. 1) at IA 193 and 263.

by England and Wilamowitz (GV 283 n. 1) at IA 193 and 263.

ἐξαιτεῖς: OΛ. Most editors adopt ἐξαιτῇ (V), which they take to mean ‘demand / ask for yourself ’ (LSJ s.v. ἐξαιτέω II 1). Yet there are no parallels for this sense with an infinitive construction, as opposed to the more urgent and humble ‘beg, implore’ (Med. 969–71 ἀλλ᾽,  … / πατρὸς νέαν γυναῖκα … / ἱκετεύετ᾽, ἐξαιτεῖσθε μὴ ϕεύγειν χθόνα, Hec. 49–50, Ba. 360–3). For the active cf. OT 1255–7 ϕοιτᾷ γὰρ ἡμᾶς ἔγχος ἐξαιτῶν πορεῖν, / γυναῖκά τ᾽ οὐ γυναῖκα, μητρῴαν δ᾽ ὅπου / κίχοι διπλῆν ἄρουραν

… / πατρὸς νέαν γυναῖκα … / ἱκετεύετ᾽, ἐξαιτεῖσθε μὴ ϕεύγειν χθόνα, Hec. 49–50, Ba. 360–3). For the active cf. OT 1255–7 ϕοιτᾷ γὰρ ἡμᾶς ἔγχος ἐξαιτῶν πορεῖν, / γυναῖκά τ᾽ οὐ γυναῖκα, μητρῴαν δ᾽ ὅπου / κίχοι διπλῆν ἄρουραν  καὶ τέκνων.

καὶ τέκνων.

176. The verse recalls 74–5, where the question of ransom (173, 174, 177nn.) did not occur. Its plain, sententious style also contrasts with Hector’s elaborate threat.

γεωργεῖν is the prose alternative to γαπονεῖν (75). In drama γεωργός appears at A. fr. 46a.18 (ascribed to the satyr-play Diktyoulkoi), and γεωργέω at Ar. Lys. 1173, Eccl. 592, 651 and Ar. fr. 102.1 PCG. See Björck, Alpha Impurum, 115, 330–1.

χεῖρες εὖ τεθραμμέναι: The participial attribute is a set expression, which also belongs to everyday speech: E. El. 64–5 τί γὰρ τάδ᾽ … ἐμὴν μοχθέω χάριν /  ἔχουσα, πρόσθεν εὖ τεθραμμένη, E. fr. 111.2–3, Diod. Com. 3.3–4 PCG (both gnomic), Pl. Rep. 496b2, D. S. 3.43.1, Apollon. Lex. Hom. 79.13 Bekker εὐπηγέες· εὖ τεθραμμένοι.

ἔχουσα, πρόσθεν εὖ τεθραμμένη, E. fr. 111.2–3, Diod. Com. 3.3–4 PCG (both gnomic), Pl. Rep. 496b2, D. S. 3.43.1, Apollon. Lex. Hom. 79.13 Bekker εὐπηγέες· εὖ τεθραμμένοι.

177. ‘Which of the Achaeans then do you want to hold to ransom alive?’

ζῶντ᾽᾽ ἀποινᾶσθαι: The correct word-division is preserved in O (ζῶντ᾽ ἀποίνασθαι [sic]) and implied in the explanations of ΣV Rh. 177 (II 331.3–5 Schwartz = 85 Merro) ἄποινα λέγεται τὰ  … τίνα οὖν, ϕησί, τῶν Ἀχαιῶν λύτρα λαβὼν βούλει ἀπολῦσαι and ΣL Rh. 177 (II 331.30 Schwartz = 86 Merro) ἢ ἀπεμπολεῖν. The middle ἀποινάομαι from ἀποινάω, ‘release for a ransom’ (Hsch. α 6362 Latte ἀποινᾶν· ἀπολυτροῦν),296 is attested only here and at 464–6 (n.) τόδε γ᾽ ἦμαρ / …

… τίνα οὖν, ϕησί, τῶν Ἀχαιῶν λύτρα λαβὼν βούλει ἀπολῦσαι and ΣL Rh. 177 (II 331.30 Schwartz = 86 Merro) ἢ ἀπεμπολεῖν. The middle ἀποινάομαι from ἀποινάω, ‘release for a ransom’ (Hsch. α 6362 Latte ἀποινᾶν· ἀπολυτροῦν),296 is attested only here and at 464–6 (n.) τόδε γ᾽ ἦμαρ / …  πολυϕόνου / χειρὸς ἀποινάσαιο λόγχᾳ (fere codd.), where both metre and sense betray corruption and Diggle (Euripidea, 515–17) ingeniously wrote … ἄποιν᾽ ἄροιο σᾷ λόγχᾳ. Yet given the present context and the frequency of ἄποινα in Homer (Iliad only), it seems strange that ζῶντα ποινᾶσθαι gained such ground in the other MSS and scholia (cf. especially ΣL Rh. 177 [II 331.30 Schwartz = 86 Merro] ἀντὶ τοῦ τιμωρεῖσθαι).297

πολυϕόνου / χειρὸς ἀποινάσαιο λόγχᾳ (fere codd.), where both metre and sense betray corruption and Diggle (Euripidea, 515–17) ingeniously wrote … ἄποιν᾽ ἄροιο σᾷ λόγχᾳ. Yet given the present context and the frequency of ἄποινα in Homer (Iliad only), it seems strange that ζῶντα ποινᾶσθαι gained such ground in the other MSS and scholia (cf. especially ΣL Rh. 177 [II 331.30 Schwartz = 86 Merro] ἀντὶ τοῦ τιμωρεῖσθαι).297

At Il. 24.686–7 Hermes states that Priam’s life would be worth three times the amount he gave for Hector’s body. Fighting heroes (and spies) are not spared for ransom on the Iliadic battlefield (Pritchett, GSW V, 246).

178. καὶ πρόσθεν εἶπον: For the syntax cf. A. Suppl. 398–9 εἶπον δὲ καὶ πρίν, οὐκ ἄνευ δήμου τάδε / πράξαιμ᾽ ἄν (with FJW on 389), and for the tone and words OC 932–3 εἶπον μὲν οὖν καὶ πρόσθεν, ἐννέπω δὲ νῦν, / τὰς παῖδας ὡς τάχιστα δεῦρ᾽ ἄγειν τινά. The parataxis makes Dolon sound all the more impatient.

ἔστι χρυσὸς ἐν δόμοις: 169–70, 170nn. The verse ends like Med. 542 εἴη δ᾽ ἔμοιγε μήτε χρυσὸς ἐν δόμοις.

179–80. This new exchange shows significant overlaps with Ag. 577–9 Τροίαν ἑλόντες  Ἀργείων στόλος / θεοῖς λάϕυρα ταῦτα τοῖς καθ᾽ Ἑλλάδα / δόμοις ἐπασσάλευσαν ἀρχαῖον γάνος (Fraenkel, Rev. 232). The practice of hanging up enemy arms and armour in temples is often referred to in poetry: e.g. Il. 7.82–3, Sept. 277–8, Hcld. 695–9, Andr. 1121–2, E. El. 6–7, 1000–1, Tro. 573–6, Hdt. 5.95.1–2 (= Alc. fr. 401B b, test. 467 Voigt). Cf. Pritchett, GSW III, 277–95, V, 132–3 and Liapis on 180 (with further literature).

Ἀργείων στόλος / θεοῖς λάϕυρα ταῦτα τοῖς καθ᾽ Ἑλλάδα / δόμοις ἐπασσάλευσαν ἀρχαῖον γάνος (Fraenkel, Rev. 232). The practice of hanging up enemy arms and armour in temples is often referred to in poetry: e.g. Il. 7.82–3, Sept. 277–8, Hcld. 695–9, Andr. 1121–2, E. El. 6–7, 1000–1, Tro. 573–6, Hdt. 5.95.1–2 (= Alc. fr. 401B b, test. 467 Voigt). Cf. Pritchett, GSW III, 277–95, V, 132–3 and Liapis on 180 (with further literature).

179. καὶ μὴν … γ᾽᾽ marks the transition to a new point (GP 351–2). With μήν Hector asserts the truth of his proposition, which he may reasonably believe to counter Dolon’s expectations. See below (παρών) and in general G. Wakker, in NAGP, 209–31 (especially 213–16, 226–7, 229–30).

λαϕύρων: The distinction of Hsch. λ 440 Latte (~ Phot. λ 121 Theodoridis, Suda λ 158 Adler) between λάϕυρα as ‘what is taken from the enemy when still alive’ and  as ‘spoils from the dead’ (cf. 591–3, 619–20a nn.) is largely confirmed by Pritchett (GSW I, 54–8, V, 132–47). Outside tragedy (Sept. 278, 479, Ag. 578, Ai. 93, Tr. 645, HF 417, Tro. 1124) the word has one mid-fifth-century attestation in the Argive inscription SIG 56.9 = 42B.9 Meiggs–Lewis ϕαλύρōν (sic).

as ‘spoils from the dead’ (cf. 591–3, 619–20a nn.) is largely confirmed by Pritchett (GSW I, 54–8, V, 132–47). Outside tragedy (Sept. 278, 479, Ag. 578, Ai. 93, Tr. 645, HF 417, Tro. 1124) the word has one mid-fifth-century attestation in the Argive inscription SIG 56.9 = 42B.9 Meiggs–Lewis ϕαλύρōν (sic).

παρών emphasises αὐτός and the fact that Dolon is offered the privilege of choosing ‘in person’ his part of the spoils (cf. 141–2n.). Similarly Agamemnon to Achilles at Il. 9.139 (~ 281) Τρωϊάδας δὲ γυναῖκας ἐείκοσιν αὐτὸς ἑλέσθω.

180. θεοῖσιν … πασσάλευε πρὸς δόμοις: Fraenkel (on Ag. 579) notes that ‘this is a less harsh expression than’ the double dative at Ag. 578–9 θεοῖς … / δόμοις  (cf. 179–80n.). Here δόμοις (QL1s) is lectio difficilior to δόμους (ΔL) and further protected by PV 56 … πασσάλευε πρὸς πέτραις. The error has numerous parallels in our MSS (FJW on A. Suppl. 793 [III, pp. 142–3]).

(cf. 179–80n.). Here δόμοις (QL1s) is lectio difficilior to δόμους (ΔL) and further protected by PV 56 … πασσάλευε πρὸς πέτραις. The error has numerous parallels in our MSS (FJW on A. Suppl. 793 [III, pp. 142–3]).

181. τί δῆτα: 149–50n.

αἰτήσεις γέρας: 169n.

αἰτήσεις γέρας: 169n.

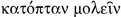

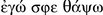

182–3. ‘The horses of Achilles. For one must work for a worthy reward, if one hazards one’s life in fortune’s game of dice.’

Dolon’s final revelation comes as a surprise, despite (or because of?) the extended build-up compared to his prompt request at Il. 10.321–3 ἀλλ᾽ ἄγε μοι τὸ σκῆπτρον ἀνάσχεο καί μοι ὄμοσσον, / ἦ μὲν τοὺς  τε καὶ ἅρματα ποικίλα χαλκῷ / δωσέμεν, οἳ ϕορέουσιν

τε καὶ ἅρματα ποικίλα χαλκῷ / δωσέμεν, οἳ ϕορέουσιν  Πηλείωνα. By reminding Hector of the risks and the need for ‘a worthy reward’ (154–5, 161–3), he confirms his materialistic approach to the task.

Πηλείωνα. By reminding Hector of the risks and the need for ‘a worthy reward’ (154–5, 161–3), he confirms his materialistic approach to the task.

ἵππους Ἀχιλλέως stands out for its initial position, followed by metrical and syntactical pause.

δ᾽᾽: 132n.