εἰκάσαι … πάρα: In addition to 802–3 (above), cf. Cho. 976–7 ὡς ἐπεικάσαι πάθει / πάρεστιν, OC 1503–4 πάντα γὰρ … / … εἰκάσαι πάρα, S. fr. 269c.22 (with Radt on 21–24) and Hel. 421–2 αὐτὰ δ᾽ εἰκάσαι / πάρεστι ναὸς ἐκβόλοις ἁμπίσχομαι.331

γε μήν: 196n.

285. γάρ: See 284–6n. In contrast to many other messenger-speeches, the particle here does not introduce the story proper (I. J. F. de Jong, in NAGP, 180–1; cf. 762–3a n.), but merely marks νυκτὸς … στρατόν as the ‘object’ of εἰκάσαι. Similarly Pers. 254–5 ὅμως δ᾽ ἀνάγκη πᾶν ἀναπτύξαι πάθος, / Πέρσαι· στρατὸς γὰρ πᾶς ὄλωλε βαρβάρων, Ag. 266–7, OT 345–9, Phil. 915–16, Cyc. 313–15, Hec. 1180–2, Ar. Pl. 76–8.

οὔτι ϕαῦλον ἐσβαλεῖν στρατόν: Cf. E. El. 760 … οὔτοι βασιλέα ϕαῦλον κτανεῖν and, for the Euripidean quality of the construction, 197b–8n. Euripides was also among the first authors, and the only one of the three tragedians, to use the ‘everyday’ ϕαῦλος and its noun extensively (32 cases as against one in Aeschylus and two in Sophocles: Pers. 520, S. frr. 41, 771.3). Rhesus has it again at 599 and 769.

ἐσβαλεῖν στρατόν: Diggle (Euripidea, 515) for ἐμβαλεῖν … (Ω). His interpretation as ‘to come upon’ cannot be upheld (284–6n.), also because ‘intransitive εἰσβάλλω is normally followed by an accusative denoting the place or area entered’ (Cyc. 99, Hipp. 1198, Andr. 968, Ba. 1045, Phaeth. 168 Diggle = E. fr. 779.1), not a person or personal collective like στρατόν (Liapis, ‘Notes’, 62). Both ἐμβάλλω and εἰσβάλλω, however, are used (with or without στρατιάν or the like) for ‘to throw an army into’ = ‘make an inroad, invade’ (LSJ s.vv. ἐμβάλλω II 1, εἰσβάλλω I, II 1). Of these the latter seems to be the more common and also bears the neutral sense ‘to bring in’, which is required here: Hdt. 2.14.2 τότε σπείρας ἕκαστος τὴν ἑωυτοῦ ἄρουραν ἐσβάλλει ἐς αὐτὴν ὗς, E. El. 78–9 ἐγὼ δ᾽ ἅμ᾽ ἡμέρᾳ / βοῦς εἰς ἀρούρας ἐσβαλὼν σπερῶ γύας. The corruption of ἐσβ- to ἐμβ- is paralleled at Hdt. 4.125.4 (which has ἐμβ- in the same paragraph), 5.15.1 and 9.13.2 (cf. LSJ s.v. ἐμβάλλω II 1). For our passage Chr. Pat. 2096 μορϕῇ γὰρ οὔτι ϕαῦλον εἰσβαλεῖν τινά (~ 2452 … εἰσβαλεῖν ἔϕην) may or may not represent a MSS variant. In any event the author altered the meaning and construction to suit his own text.

286. This is the only trimeter in Rhesus with more than one resolution, inspired perhaps by Med. 1321–2 τοιόνδ᾽ ὄχημα πατρὸς Ἥλιος πατήρ / δίδωσιν ἡμῖν, ἔρυμα πολεμίας χερός (Ritchie 267–8; cf. Klyve on 286). For the π-alliteration see 282–3n.

κλυόντα: so West rightly for present κλύοντα (Ω) because the participle ‘is subordinated to an aorist main verb denoting a simultaneous or consequent action’ and ‘a single specific occasion of cognition is in question’ (BICS 31 [1984], 177, 178). Cf. 109–10a n.

287–9. ‘But he frightened us peasants, who live among the crags of Ida in our land’s ancestral dwellings, as he came to the thickets at night, the haunts of wild animals.’

ἀγρώσταις: 266n.

κατ᾽  λέπας: Here λέπας is employed ‘not in the older sense … of a naked cliff or summit … but rather [as] a collective term

for the broken country where forest, rock, and upland pasture mix’ (Dodds on Ba. 677–8 (Αγ.)

λέπας: Here λέπας is employed ‘not in the older sense … of a naked cliff or summit … but rather [as] a collective term

for the broken country where forest, rock, and upland pasture mix’ (Dodds on Ba. 677–8 (Αγ.)  / μόσχων

/ μόσχων  cf. 264–341n.). So also Andr. 295, E. fr. 411.2

cf. 264–341n.). So also Andr. 295, E. fr. 411.2  (… ) λέπας, Phoen. 24, Ba. 751–2, 1045. Differently 921–2a (n.)

(… ) λέπας, Phoen. 24, Ba. 751–2, 1045. Differently 921–2a (n.)  ἐς

ἐς  / Πάγγαιον.

/ Πάγγαιον.

αὐτόρριζον ἑστίαν χθονός: literally ‘the self-rooted hearth of our land’ (i.e. ‘where we put down our roots’), and so probably an allusion to Dardanus’ ancient foundation at the foot of Mt. Ida: Il. 20.216–18 κτίσσε δὲ Δαρδανίην, ἐπεὶ οὔ

/ ἐν

/ ἐν  πεπόλιστο,

πεπόλιστο,

/

/

Hellanic. FGrHist 4 F 25a. This interpretation, which most scholars have adopted from the Renaissance on, is supported by A. Suppl. 370–2 (Chorus to Pelasgus)

Hellanic. FGrHist 4 F 25a. This interpretation, which most scholars have adopted from the Renaissance on, is supported by A. Suppl. 370–2 (Chorus to Pelasgus)  … /

… /

/

/  , ἑστίαν χθονός and several places where ἑστία denotes a geographical focal point: E. fr. 944 καὶ Γαῖα

, ἑστίαν χθονός and several places where ἑστία denotes a geographical focal point: E. fr. 944 καὶ Γαῖα  ·

·

/

/

,332 Call. Del. 325

,332 Call. Del. 325

,

,  , Plb. 5.58.4, D. S. 4.19.2 (LSJ s.v. ἑστία I 5; cf. Feickert on 288). αὐτόρριζος is first found here, and not again before the first century BC. It usually means ‘together with the roots’ (e.g. D. S. 4.12.5, Babr. 36.1–2), but ‘self-rooted’ recurs at Opp. Hal. 2.464–6 (of the swordfish) καὶ

, Plb. 5.58.4, D. S. 4.19.2 (LSJ s.v. ἑστία I 5; cf. Feickert on 288). αὐτόρριζος is first found here, and not again before the first century BC. It usually means ‘together with the roots’ (e.g. D. S. 4.12.5, Babr. 36.1–2), but ‘self-rooted’ recurs at Opp. Hal. 2.464–6 (of the swordfish) καὶ

/… αὐτόρριζον … /

/… αὐτόρριζον … /  and Nonn. D. 40.469–70 αἷς ἔνι

and Nonn. D. 40.469–70 αἷς ἔνι  /

/  … ἔρνος

… ἔρνος  Par. 1.64, 19.224. In view of the Aeschylean parallel for ἑστίαν χθονός (above), Fraenkel (Rev. 238) may be right to associate the word with the same poet (who has numerous αὐτο- compounds). Cf. PV 1046–7

Par. 1.64, 19.224. In view of the Aeschylean parallel for ἑστίαν χθονός (above), Fraenkel (Rev. 238) may be right to associate the word with the same poet (who has numerous αὐτο- compounds). Cf. PV 1046–7

/

/  (~ Il. 9.541–2

(~ Il. 9.541–2

/ αὐτῇσιν ῥίζῃσιν). Pindar applied

/ αὐτῇσιν ῥίζῃσιν). Pindar applied  to an aboriginal place: Pyth. 4.15 (Cyrene)

to an aboriginal place: Pyth. 4.15 (Cyrene)  , 9.8 (Libya)

, 9.8 (Libya)

τρίταν (LSJ s.v. ῥίζα II 1).

τρίταν (LSJ s.v. ῥίζα II 1).

Other renderings are less convincing. Paley’s ‘on the very foot of the mountain’ is feeble and not borne out by the later usage of αὐτόρριζος. J. T. Sheppard (CR 28 [1914], 87–8) compares Hsch. α 8492 Latte (~ fr. tr. adesp. 201)  ·

·

333 and assigns to the shepherds ‘a hearth rock-rooted on the mountains’, if they do not actually live in caves (cf.

333 and assigns to the shepherds ‘a hearth rock-rooted on the mountains’, if they do not actually live in caves (cf.  Rh. 288 [II 333.25–6 Schwartz = 91 Merro], Liapis on 287–9). That the latter contradicts 273

τὰς

Rh. 288 [II 333.25–6 Schwartz = 91 Merro], Liapis on 287–9). That the latter contradicts 273

τὰς  and 293 need not be an objection (185n.). But the description of humble peasant abodes seems less apposite here than a modest expression of pride in the land of Troy.

and 293 need not be an objection (185n.). But the description of humble peasant abodes seems less apposite here than a modest expression of pride in the land of Troy.

δρυμὸν … ἔνθηρον: an accusative of direction (KG I 311–12, SD 67–8). For  note Il. 8.47

note Il. 8.47  … πολυπίδακα,

… πολυπίδακα,  (cf. Il. 14.283, 15.151, h.Ven. 68) and, in terms of language, S. fr. 314.221–2 (Ichneutae) θῆρες,

(cf. Il. 14.283, 15.151, h.Ven. 68) and, in terms of language, S. fr. 314.221–2 (Ichneutae) θῆρες,  [τό]νδε

[τό]νδε  / ἔν[θ]

/ ἔν[θ]  ὡρμήθητε σὺν

ὡρμήθητε σὺν  ;

;

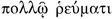

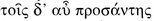

290. Θρῄκιος  : The verb ῥέω suggests a great multitude of men (as described in 309–13) that inexorably moves forward like a stream. It here recalls Sept. 79–80

: The verb ῥέω suggests a great multitude of men (as described in 309–13) that inexorably moves forward like a stream. It here recalls Sept. 79–80  … /

… /

and the equivalent use of

and the equivalent use of  at Pers. 88

at Pers. 88  , 412

, 412  , Ant. 128–9 καί

, Ant. 128–9 καί  /

/

(itself echoing Aeschylus) and IT 1437

(itself echoing Aeschylus) and IT 1437  … στρατοῦ. In a non-military context see E. fr. 146.1 < × - ∪ > πᾶς δὲ

… στρατοῦ. In a non-military context see E. fr. 146.1 < × - ∪ > πᾶς δὲ  λεώς.

λεώς.

Within the narrative,  … στρατός anticipates information gained only as the army drew nearer and could be overheard (294–5). But the Shepherd had already mentioned their provenance and that Rhesus was their lord (279–81).

… στρατός anticipates information gained only as the army drew nearer and could be overheard (294–5). But the Shepherd had already mentioned their provenance and that Rhesus was their lord (279–81).

291b–3. ‘And struck with alarm, we drove our flocks to the heights, in case any of the Argives was coming to plunder and to destroy your folds …’

The shepherds’ worries are realistic. Achaean raids were common (Feickert on 293), and on one occasion Aeneas only just escaped Achilles, who had come after the Trojan cattle grazing on Mt. Ida: Il. 20.90–1 (with Edwards on 89–93), 20.187–90, Cypria (Arg. p. 78 (11) GEF). For peasants and their livestock mountains presented a natural refuge in case of an invasion (V. D. Hanson, Warfare and Agriculture in Classical Greece, Pisa 11983, 95–7 ~ Berkeley et al. 21998, 114–16).

θάμβει: essentially ‘astonishment, awe’. The connotation of ‘alarm’ is even stronger in Hec. 177–9  / καρύξασ᾽ οἴκων μ᾽

/ καρύξασ᾽ οἴκων μ᾽  / θάμβει τῷδ᾽ ἐξέπταξας; To the discussion of the word family by FJW on A. Suppl. 570 add ἀθαμβής, ‘devoid of awe’, i.e. ‘reckless, fearless’, in e.g. Ibyc. 286.11 PMGF, Phryn. Trag. TrGF 3 F 2, Bacch. 15.58, Lyc. 558, Plut. Lyc. 16.4 (Jebb on Bacch. 14[15].57–8, M. Nöthiger, Die Sprache des Stesichorus und des Ibycus, Zurich 1971, 177–8) and Democritus’ ideal of philosophical

/ θάμβει τῷδ᾽ ἐξέπταξας; To the discussion of the word family by FJW on A. Suppl. 570 add ἀθαμβής, ‘devoid of awe’, i.e. ‘reckless, fearless’, in e.g. Ibyc. 286.11 PMGF, Phryn. Trag. TrGF 3 F 2, Bacch. 15.58, Lyc. 558, Plut. Lyc. 16.4 (Jebb on Bacch. 14[15].57–8, M. Nöthiger, Die Sprache des Stesichorus und des Ibycus, Zurich 1971, 177–8) and Democritus’ ideal of philosophical  (68 A 169, B 4, 215, 216 DK).

(68 A 169, B 4, 215, 216 DK).

πρὸς ἄκρας: For ἄκρα, ‘summit, height’, cf. Alc. fr. 48.13 Voigt … ]ν  (?), S. fr. 271.1–2 ῥεῖ γὰρ (sc. ὁ

(?), S. fr. 271.1–2 ῥεῖ γὰρ (sc. ὁ  ) ἀπ᾽ ἄκρας /

) ἀπ᾽ ἄκρας /  , Or. 871, Thuc. 7.3.3.

, Or. 871, Thuc. 7.3.3.

: Like 843 … ὥς τις Ἀργείων μολών, this is a variation on …

: Like 843 … ὥς τις Ἀργείων μολών, this is a variation on …  (149–50n.). The object clause

(149–50n.). The object clause  …

…  depends on

depends on  …

…  as a verbal expression of fear.

as a verbal expression of fear.

λεηλατήσων: literally ‘to drive away booty’ (λεία + ἐλαύνω), and so particularly of (or including) cattle: e.g. Ai. 342–3, Hec. 1142–3, Xen. Cyr. 1.4.17, HG 2.4.4. It is combined with  at Hell. Oxy. 24.1, 24.6 Chambers, Plb. 4.26.4 and Plut. Cam. 23.1.

at Hell. Oxy. 24.1, 24.6 Chambers, Plb. 4.26.4 and Plut. Cam. 23.1.

294–7. Reassured by the sound of non-Greek voices (294–5), the Shepherd goes to question the foreign explorers – in Thracian (296–7). The fact that different peoples speak different languages or dialects, or that individuals speak more than their native tongue (see already Il. 2.803–4, 867, 4.437–8, Od. 19.175, h.Ven. 113–16) is conventionally ignored in tragedy, except when calling attention to it ‘serves some special purpose’ (FJW on A. Suppl. 118–19 = 129–30, who refer to Thomson and Fraenkel on Ag. 1061).334 The Shepherd’s proficiency here is probably meant to reflect not only the alleged racial ties between Thracians and Phrygians (below), but also the pan-barbarian opposition to the Greeks, which Hector and Rhesus’ charioteer invoke (404–5, 833–4nn.). In that latter sense linguistic (and dialectal) variance is played out at Pers. 401–7 and Sept. 169–70 (with Hutchinson on 170).

The Phrygians were known to have migrated into Anatolia from the Balkans and Thrace: Hdt. 7.73, Xanth. FGrHist 765 FF 14, 15, Strabo 10.3.16 (cf. P. Carrington, AS 27 [1977], 117–26). They did not, however, speak a common language; indeed Thracian and Phrygian may not even belong to the same Indo-European sub-group (R. D. Woodard – C. Brixhe, in R. D. Woodard [ed.], The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World’s Ancient Languages, Cambridge 2004, 12, 780). Genuine ‘Thracians in Asia’ were the Bithynians and related tribes (Pherecyd. FGrHist 3 F 27, Hdt. 1.28, 3.90.2, 7.75.2, Xen. An. 6.4.1–2). Their area of settlement along the Propontis and south-western Black Sea was close enough to the Troad to allow for contact on various levels. A Trojan peasant speaking Thracian, therefore, was conceivable also in historical times.

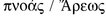

294–5. One may compare Philoctetes’ relief at finally hearing Greek: Phil. 234–5 ὦ

τὸ καὶ

τὸ καὶ  /

/  τοιοῦδ᾽

τοιοῦδ᾽  (Klyve on 294).

(Klyve on 294).

πρὶν δή: ‘until (indeed) …’, as in Andr. 1145–8 ἐν

/ ἔστη … δεσπότης … /

/ ἔστη … δεσπότης … /

/ δεινόν τι καὶ ϕρικῶδες, Hdt. 1.13.2, 4.157.2, Thuc. 1.118.2, 3.29.1, 3.104.6 (GP 220). The use of

/ δεινόν τι καὶ ϕρικῶδες, Hdt. 1.13.2, 4.157.2, Thuc. 1.118.2, 3.29.1, 3.104.6 (GP 220). The use of  with the indicative depending on an affirmative clause in the past is rare (KG II 453–4, SD 655), and often a negative force can still be detected in the main verb, a predicative adjective or in thought (cf. Jebb on OT 776). In tragedy it also occurs at A. fr. 83 (?), PV 480–3, OT 775–8, Alc. 127–9, Med. 1171–5, Hec. 130–40, IA 489–90 and Rh. 568–9. All except the last example mark a decisive turning point in the narrated action (Dawe on OT 776).

with the indicative depending on an affirmative clause in the past is rare (KG II 453–4, SD 655), and often a negative force can still be detected in the main verb, a predicative adjective or in thought (cf. Jebb on OT 776). In tragedy it also occurs at A. fr. 83 (?), PV 480–3, OT 775–8, Alc. 127–9, Med. 1171–5, Hec. 130–40, IA 489–90 and Rh. 568–9. All except the last example mark a decisive turning point in the narrated action (Dawe on OT 776).

δι᾽ ὤτων … / ἐδεξάμεσθα: ‘received with our ears’ = ‘heard’. Cf. Ba. 1086–7 αἳ δ᾽ ὠσὶν  /

/  καὶ

καὶ  , E. El. 110–11

, E. El. 110–11  /

/  …

…  , and, for δι᾽

, and, for δι᾽  / ὠτός, Cho. 56, 451, S. El. 737, 1437, OT 1387, Ant. 1188, S. fr. 858.2, Med. 1139, Rh. 565-6

/ ὠτός, Cho. 56, 451, S. El. 737, 1437, OT 1387, Ant. 1188, S. fr. 858.2, Med. 1139, Rh. 565-6  κενὸς

κενὸς  / στάζει δι᾽ ὤτων, Theoc. 14.27.

/ στάζει δι᾽ ὤτων, Theoc. 14.27.

καὶ μετέστημεν ϕόβου: similar verse-ends in Eum. 900 … καὶ  , Alc. 21 … καὶ μεταστῆναι βίου, Hel. 856 … καὶ μεταστήτω κακῶν and Ba. 944 … ὅτι μεθέστηκας ϕρενῶν.

, Alc. 21 … καὶ μεταστῆναι βίου, Hel. 856 … καὶ μεταστήτω κακῶν and Ba. 944 … ὅτι μεθέστηκας ϕρενῶν.

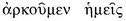

296–7. ‘And I went and asked those scouting a path ahead for their lord, addressing them in Thracian.’

depends on ὁδοῦ or possibly προυξερευνητὰς ὁδοῦ together. There is no need to alter the text, as Kovacs did by adopting Morstadt’s ἔναντα (Beitrag, 20 n. 2), and several other scholars have proposed (Wecklein, Appendix, 50, to which add his own ἀν᾽ αὐτούς [SBAW I (1897), 494]). The Shepherd may assume that the army was led by a ‘lord’ – or ἄνακτος is spoken with hindsight, like 290 (n.) …  .

.

προυξερευνητάς: The noun is a hapax. But  occurs at Phoen. 92 (the Old Servant to Antigone) ἐπίσχες, ὡς ἂν προυξερευνήσω στίβον, which probably inspired the formation here (Fraenkel, Rev. 231, 234, against Ritchie 150, 207). For military scouting (cf. Xen. Cyr. 5.4.4, 6.3.2 προδιερευνάω, διερευνητής) the verb is used in Aen. Tact. 15.5

occurs at Phoen. 92 (the Old Servant to Antigone) ἐπίσχες, ὡς ἂν προυξερευνήσω στίβον, which probably inspired the formation here (Fraenkel, Rev. 231, 234, against Ritchie 150, 207). For military scouting (cf. Xen. Cyr. 5.4.4, 6.3.2 προδιερευνάω, διερευνητής) the verb is used in Aen. Tact. 15.5

,

,  <ἀτάκτους>, προεξερευνῶντάς

<ἀτάκτους>, προεξερευνῶντάς  καὶ

καὶ  . See further F. S. Russell, Information Gathering in Classical Greece, Ann Arbor 1999, 10–22.

. See further F. S. Russell, Information Gathering in Classical Greece, Ann Arbor 1999, 10–22.

ὁδοῦ: so rightly V.  (

( ) cannot meaningfully be construed with either ἄνακτος or

) cannot meaningfully be construed with either ἄνακτος or  and may easily have intruded from the context. στρατόν or -ός stand at the end of 285 and 290.

and may easily have intruded from the context. στρατόν or -ός stand at the end of 285 and 290.

: 294–7n. πρόσϕθεγγμα, ‘address’, is frequent in tragedy and mainly used in the plural, as here: e.g. Ag. 903,

Cho. 876, A. fr. 47a.7 (Diktyoulkoi), Ai. 500, Phil. 235, Hcld. 573, Hec. 413, Or. 75, E. fr. 309a. For the double γ (as also in 608 ϕθέγγματος) see West, ed. Aeschylus, LII.

: 294–7n. πρόσϕθεγγμα, ‘address’, is frequent in tragedy and mainly used in the plural, as here: e.g. Ag. 903,

Cho. 876, A. fr. 47a.7 (Diktyoulkoi), Ai. 500, Phil. 235, Hcld. 573, Hec. 413, Or. 75, E. fr. 309a. For the double γ (as also in 608 ϕθέγγματος) see West, ed. Aeschylus, LII.

298–9. The Shepherd asks the traditional question for the general’s name and descent, leaving out the country of origin, which he has already established (294–7). The information was imparted to the audience at 278–81.

τίνος κεκλημένος: 279n.

σύμμαχος: The leader of an army not speaking Greek (294–5n.) can be assumed to be an ally.

300–1a. ὧν ἐϕιέμην μαθεῖν: The relative pronoun is governed by ἐϕιέμην, with a genitive, as usual (44–7a n.), and  follows either as an epexegetic infinitive (Bruhn, Anhang, § 137, SD 361–2), or we explain the whole construction by attraction of the object to the main verb (KG II 276–7 with n. 1). So also Pl. Rep. 437b1–2 τὸ

follows either as an epexegetic infinitive (Bruhn, Anhang, § 137, SD 361–2), or we explain the whole construction by attraction of the object to the main verb (KG II 276–7 with n. 1). So also Pl. Rep. 437b1–2 τὸ  τινος

τινος  and e.g. h.Cer. 283–4 οὐδέ τι

and e.g. h.Cer. 283–4 οὐδέ τι  / μνήσατο τηλυγέτοιο

/ μνήσατο τηλυγέτοιο  , Pi. Ol. 3.33–4 (δένδρεα …) τῶν νιν

, Pi. Ol. 3.33–4 (δένδρεα …) τῶν νιν

… / … ϕυτεῦσαι, Med. 1399–1400 ὤμοι, ϕιλίου χρῄζω στόματος /

… / … ϕυτεῦσαι, Med. 1399–1400 ὤμοι, ϕιλίου χρῄζω στόματος /  .

.

301b–8. Rhesus’ description is largely based on Il. 10.436–41 τοῦ δὴ

· /

· /  , θείειν δ᾽

, θείειν δ᾽  . /

. /

/

/  , θαῦμα ἰδέσθαι, /

, θαῦμα ἰδέσθαι, /

/

/  ,

,  θεοῖσιν. But while Dolon there presents him as little more than a valuable target (to save himself by offering useful information: Il. 10.442–5), the Shepherd expresses genuine wonder, which foreshadows the ‘deification’ of Rhesus in the chorus’ eyes (264–341, 301b–2nn.). Details of the reworking and other passages that influenced the report are discussed in 301b–2, 303–4, 305–6a, 306b–8nn.

θεοῖσιν. But while Dolon there presents him as little more than a valuable target (to save himself by offering useful information: Il. 10.442–5), the Shepherd expresses genuine wonder, which foreshadows the ‘deification’ of Rhesus in the chorus’ eyes (264–341, 301b–2nn.). Details of the reworking and other passages that influenced the report are discussed in 301b–2, 303–4, 305–6a, 306b–8nn.

301b–2. ὁρῶ δέ: With this introduction ‘the Messenger not only stresses the fact that he was an eyewitness, but through his use of the historic present also asks our special attention for what he has seen and is about to recount’ (de Jong, Narrative in Drama, 44). Cf. E. Suppl. 651–3  /

/  /

/  δὲ … (where note

δὲ … (where note  in the preceding line), Or. 871, Ba. 680 (cf. 264–341n.) and, marking a fresh start in the story, Phoen. 1165, Or. 879. In a way, all that the Shepherd had said so far was preliminary to his portrayal of Rhesus’ approach.

in the preceding line), Or. 871, Ba. 680 (cf. 264–341n.) and, marking a fresh start in the story, Phoen. 1165, Or. 879. In a way, all that the Shepherd had said so far was preliminary to his portrayal of Rhesus’ approach.

ὥστε δαίμονα: In contrast to Il. 10.436–41 (301b–8n.), the comparison with a god here comes first and refers to Rhesus’ entire appearance. The wording is not far from the epic δαίμονι ἶσος (e.g. Il. 5.438, 16.705, 786, h.Cer. 235) – whereas the chorus later all but identify Rhesus with Zeus and Ares (Ritchie 69, Fenik, Iliad X, 26–7 n. 3; cf. 355–6, 357–9, 385–7nn.).

Comparative ὥστε is common in tragedy, and usually (as here and in 618) the verb has to be supplied from the main clause. Examples of full comparative clauses are few and often doubtful (GP 526–7, Ruijgh, Te épique, 991–8, Diggle, Euripidea, 321–3). Cf. 972–3n.

ἑστῶτ᾽ ἐν ἵπποις Θρῃκίοις τ᾽ ὀχήμασιν: Λ’s text (apart from  Q,

Q,  LcP) gains support from Il. 4.366 = 11.198 (of Diomedes and Hector respectively) ἑσταότ᾽

LcP) gains support from Il. 4.366 = 11.198 (of Diomedes and Hector respectively) ἑσταότ᾽

, which our poet evidently wished to recall. Editors before Murray preferred to read ἐν

, which our poet evidently wished to recall. Editors before Murray preferred to read ἐν  (Δ), with the horses expressed by an adjective, as in 416 παρ᾽

(Δ), with the horses expressed by an adjective, as in 416 παρ᾽  and Hcld. 845

and Hcld. 845  . But apart from losing the Homeric echo, the presence of two parallel epithets with

. But apart from losing the Homeric echo, the presence of two parallel epithets with  is awkward, especially since Θρῃκίοις is likely to qualify the horses as well as the chariot (cf. 616–17

is awkward, especially since Θρῃκίοις is likely to qualify the horses as well as the chariot (cf. 616–17  δὲ

δὲ  /

/  ). The mistake is a simplifying one by a scribe perhaps who was puzzled by the separate mention of animals and vehicle. This is regular in epic (or

). The mistake is a simplifying one by a scribe perhaps who was puzzled by the separate mention of animals and vehicle. This is regular in epic (or  / -οι alone stands for ‘horses and chariot’), but in tragedy recurs only at IA 83

/ -οι alone stands for ‘horses and chariot’), but in tragedy recurs only at IA 83

.335

.335

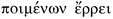

303–4. ‘And a golden collar enclosed the yoke-bearing necks of his horses, gleaming whiter than snow.’

χρυσῆ … πλάστιγξ: Properly the ‘scale of a balance’,  is here used for the collar that joined the horses to the yoke and allowed them to draw the chariot (Anderson, Ancient Greek Horsemanship, 3, 108 with plts. 14a, 16, 19, 31c). The metaphor arose by similarity. Hanging ready from the outer ends of the yoke, the collars could be likened to the scales of a balance (GEW, DELG s.v. πλάστιγξ); conversely ζυγόν / ζυγός (‘yoke’) came to denote various kinds of crossbars and specifically the beam of a balance or the balance itself (LSJ s.v. ζυγόν IV a). Porter (on 303) appropriately cites Pl. Rep. 550e7

is here used for the collar that joined the horses to the yoke and allowed them to draw the chariot (Anderson, Ancient Greek Horsemanship, 3, 108 with plts. 14a, 16, 19, 31c). The metaphor arose by similarity. Hanging ready from the outer ends of the yoke, the collars could be likened to the scales of a balance (GEW, DELG s.v. πλάστιγξ); conversely ζυγόν / ζυγός (‘yoke’) came to denote various kinds of crossbars and specifically the beam of a balance or the balance itself (LSJ s.v. ζυγόν IV a). Porter (on 303) appropriately cites Pl. Rep. 550e7

.

.

The same basic meaning for  has been recognised at Cho. 288–90 καὶ

has been recognised at Cho. 288–90 καὶ

,

,  , where an allusion to human scapegoats and the metal collar employed ‘in execution by apotympanismos’ appears to be made (Sommerstein,

Aeschylus II, 249 n. 64; cf. L. Battezzato, SCO 42 [1992], 71–4, West, apparatus 290).336 Our poet may even have had the passage in mind, given that Cho. 288–9 shares several words also with Rh. 691 (n.). The more widespread ζεύγλη, ‘half-collar’, and λέπαδνα, ‘yoke-straps’ (J. Wiesner, Arch. Hom. F 18–19, 53–5, 106–7), at any rate did not scan.

, where an allusion to human scapegoats and the metal collar employed ‘in execution by apotympanismos’ appears to be made (Sommerstein,

Aeschylus II, 249 n. 64; cf. L. Battezzato, SCO 42 [1992], 71–4, West, apparatus 290).336 Our poet may even have had the passage in mind, given that Cho. 288–9 shares several words also with Rh. 691 (n.). The more widespread ζεύγλη, ‘half-collar’, and λέπαδνα, ‘yoke-straps’ (J. Wiesner, Arch. Hom. F 18–19, 53–5, 106–7), at any rate did not scan.

adapts Il. 10.438 ἅρμα δέ οἱ χρυσῷ τε καὶ

(301b–8n.) and so refers to gold decoration, as presumably also of Rhesus’ armour at Il. 10.439 (305–6a, 340–1, 370–2a nn.). Hera’s chariot, by contrast, has a yoke and yoke-straps ‘of gold’ (Il. 5.729–31). The precious metal is characteristic of divine accoutrements (West, EFH 112, IEPM 153–4).

(301b–8n.) and so refers to gold decoration, as presumably also of Rhesus’ armour at Il. 10.439 (305–6a, 340–1, 370–2a nn.). Hera’s chariot, by contrast, has a yoke and yoke-straps ‘of gold’ (Il. 5.729–31). The precious metal is characteristic of divine accoutrements (West, EFH 112, IEPM 153–4).

αὐχένα ζυγηϕόρον / πώλων: Cf. A. fr. dub. 465.1  … ζυγηϕόρους, Hipp. 1183

… ζυγηϕόρους, Hipp. 1183

and HF 121

and HF 121  . Later prose has ζυγοϕόρος: Plut. De cup. div. 2.524a, [Athan.] In nat. praec. 28.905.38–9 Migne τὸν

. Later prose has ζυγοϕόρος: Plut. De cup. div. 2.524a, [Athan.] In nat. praec. 28.905.38–9 Migne τὸν  … αὐχένα (of an ox). For ᾱ (η) instead of ο in nominal o-stem composition see Schwyzer 438–9 with 439 n. 1.

… αὐχένα (of an ox). For ᾱ (η) instead of ο in nominal o-stem composition see Schwyzer 438–9 with 439 n. 1.

The enallage produced by  (Δ) is preferable to

(Δ) is preferable to  (Λ). Either reading, however, could have arisen by assimilation.

(Λ). Either reading, however, could have arisen by assimilation.

: Rhesus’ horses are λευκότεροι χιόνος in Il. 10.437 (301b–8n.), make Nestor compare them to sunrays (Il. 10.547) and shine though the night like a swan’s plumage at 616–18 (616–17, 618nn.). Only 356 ἥκεις

: Rhesus’ horses are λευκότεροι χιόνος in Il. 10.437 (301b–8n.), make Nestor compare them to sunrays (Il. 10.547) and shine though the night like a swan’s plumage at 616–18 (616–17, 618nn.). Only 356 ἥκεις

deviates, perhaps from literary reminiscence (185, 355–6nn.).

deviates, perhaps from literary reminiscence (185, 355–6nn.).

ἐξαυγής (with intensifying ἐξ-) is a hapax formed like e.g. τηλαυγής,  and

and  (<

(<  ). There is no reason to write εὐαυγεστέρων with Blaydes (Adversaria critica, 4), although Ba. 661–2

). There is no reason to write εὐαυγεστέρων with Blaydes (Adversaria critica, 4), although Ba. 661–2  …)

…)

/

/

(εὐαυγεῖς Hemsterhuys, ἐξαυγεῖς Elmsley) remains worth quoting (264–341n.).

(εὐαυγεῖς Hemsterhuys, ἐξαυγεῖς Elmsley) remains worth quoting (264–341n.).

305–6a. ‘On his shoulders his shield flashed with images inlaid with gold.’

Following Il. 10.439 τεύχεα δὲ χρύσεια  (301b–8, 340–1, 382nn.), Rhesus is equipped with a gold-decorated Thracian pelte, like Telamon at E. fr. 530.1–2 (Meleager)

(301b–8, 340–1, 382nn.), Rhesus is equipped with a gold-decorated Thracian pelte, like Telamon at E. fr. 530.1–2 (Meleager)

/

/  (sc. ἔχων) and Diomedes, lord of the flesh-eating horses, at Alc. 498

(sc. ἔχων) and Diomedes, lord of the flesh-eating horses, at Alc. 498

(~

Rh. 370–2a [n.]). In reality this small crescent-shaped shield was made of wood or wicker-work and covered with animal skin (often painted). Yet despite Aristotle apud

(~

Rh. 370–2a [n.]). In reality this small crescent-shaped shield was made of wood or wicker-work and covered with animal skin (often painted). Yet despite Aristotle apud  V Rh. 311 (II 334.1–7 Schwartz = 92 Merro) = fr. 498 Rose, a thin layer of bronze is also attested (Xen. An. 5.2.29), which in ‘poetic fantasy’ (Parker on Alc. 498) could have been replaced with gold. Later in Rhesus the pelte tends to be described in terms of the much larger and heavier hoplite shield (311–13, 383–4, 408–10a, 485–7nn.).

V Rh. 311 (II 334.1–7 Schwartz = 92 Merro) = fr. 498 Rose, a thin layer of bronze is also attested (Xen. An. 5.2.29), which in ‘poetic fantasy’ (Parker on Alc. 498) could have been replaced with gold. Later in Rhesus the pelte tends to be described in terms of the much larger and heavier hoplite shield (311–13, 383–4, 408–10a, 485–7nn.).

χρυσοκολλήτοις τύποις: i.e. figures of beaten metal inlaid with gold (LSJ s.vv. τύπος IV, χρυσόκολλος, -κόλλητος). Even more perhaps than Telamon’s pelte (above), one recalls the blazons of the ‘Seven’ so elaborately described by the Scout in the course of Sept. 369–685; cf. particularly the gold-plated ones of Capaneus (434) and Polynices (644–5, 660–1). At Phoen. 1130–1 σιδηρονώτοις δ᾽ ἀσπίδος  / γίγας (

/ γίγας (

1:

1:

) the reading of the ancient wood tablet seems preferable to that of the MSS (J. M. Bremer, Mnemosyne IV 36 [1983], 300–1). Otherwise Mastronarde on Phoen. 1130.337

) the reading of the ancient wood tablet seems preferable to that of the MSS (J. M. Bremer, Mnemosyne IV 36 [1983], 300–1). Otherwise Mastronarde on Phoen. 1130.337

It is (for once) unlikely that  here was borrowed from the Sun’s chariot at Phoen. 2

here was borrowed from the Sun’s chariot at Phoen. 2  …

…  (e.g. Fraenkel, Rev. 234). Phoen. 1–2 are deleted by Haslam (GRBS 16 [1975], 149–74) as virtually unattested before the medieval tradition and stylistically otiose in combination with Phoen. 3 (cf. Mastronarde on Phoen. [1–2]). If the lines are early, their absence from ancient testimonia and papyri may indicate simply that they were not widely current (and probably unknown to Aristophanes of Byzantium), but they have perhaps a better claim to a later date.

(e.g. Fraenkel, Rev. 234). Phoen. 1–2 are deleted by Haslam (GRBS 16 [1975], 149–74) as virtually unattested before the medieval tradition and stylistically otiose in combination with Phoen. 3 (cf. Mastronarde on Phoen. [1–2]). If the lines are early, their absence from ancient testimonia and papyri may indicate simply that they were not widely current (and probably unknown to Aristophanes of Byzantium), but they have perhaps a better claim to a later date.  and

and  were regular in drama: S. fr. 378.3, E. fr. 587 (of a sword hilt), Antiph. frr. 105.2, 234.2 PCG (both paratragic). Similarly

were regular in drama: S. fr. 378.3, E. fr. 587 (of a sword hilt), Antiph. frr. 105.2, 234.2 PCG (both paratragic). Similarly  at Tr. 1261 and Men. fr. 275.1 PCG and

at Tr. 1261 and Men. fr. 275.1 PCG and  at S. fr. 314.375 (Ichneutae).

at S. fr. 314.375 (Ichneutae).

V has δίϕροις for  (ἵπποις Q), either by scribal recollection of Phoen. 2 (above) or from a marginal or interlinear parallel (Klyve on 305).

(ἵπποις Q), either by scribal recollection of Phoen. 2 (above) or from a marginal or interlinear parallel (Klyve on 305).

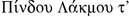

306b–8. ‘And a bronze Gorgon as on the goddess’ aegis was attached to the horses’ foreheads and rang forth terror with many bells.’

The narrative returns to the chariot in the widest sense: Il. 10.438 (301b–8n.). For the fearful noise of horse-trappings cf. e.g. the chorus at Sept. 123–4 διάδετοι δὲ < - > γενυῶν  /

/

(with West’s apparatus and Studies, 105) and 206–7

(with West’s apparatus and Studies, 105) and 206–7  τ᾽

τ᾽  /

/

. More specifically our poet seems to have recalled Sept. 385–6 ὑπ᾽ ἀσπίδος δὲ τῷ /

. More specifically our poet seems to have recalled Sept. 385–6 ὑπ᾽ ἀσπίδος δὲ τῷ /

, both here and at 383–4

(n.).338 His portrayal of a mighty foreign warrior bound to be killed at Troy was traditional, to judge by Ar. Ran. 962–3 (‘Euripides’ to ‘Aeschylus’)

, both here and at 383–4

(n.).338 His portrayal of a mighty foreign warrior bound to be killed at Troy was traditional, to judge by Ar. Ran. 962–3 (‘Euripides’ to ‘Aeschylus’)  , /

, /

(cf. Introduction, 33, 41).

(cf. Introduction, 33, 41).

ὡς ἐπ᾽ αἰγίδος θεᾶς: i.e. Athena, who in classical times is mainly associated with the aegis (as a kind of shawl, usually lined with snakes and bearing the Gorgoneion [Il. 5.738–42] in the middle). In Homer the aegis – a shield of metal and/or covered with goat-skin (αἰγ-)? – belongs to Zeus, who shakes it in anger (Il. 4.166–8). Athena uses it to spur on the Greeks (Il. 2.446–54), and Apollo to lead the Trojans into battle and rout the Achaeans (Il. 15.229–30, 308–11, 318–27, 360–6). So also the Gorgon’s heads on the frontlets of Rhesus’ horses are meant to frighten the enemy with the flash of polished bronze and the clang of the bells (fastened to the bridles and maybe the harness) as the animals move. Like a god (301b–2n.) going before his host, Rhesus will cause panic merely by being seen (and heard): 335 (n.)

.

.

The Gorgoneion was probably as common on horse frontlets (E. Pernice, Griechisches Pferdegeschirr im Antiquarium der Königlichen Museen, Berlin 1896, 28)339 as it was as a device on shields and other pieces of armour from the seventh century on (LIMC IV.1/2 s.v. Gorgo, Gorgones A 19, 72–4, 87, 89, B 147–9, 151, E 156–193, F 194–228). For the nature and various etymologies of the aegis see LfgrE s.v. αἰγίς E, B, Kirk on Il. 2.446–51, Janko on Il. 15.18–31 (p. 230), 308–11, Edwards on Il. 17.593–6.

ἐκτύπει ϕόβον: an internal accusative, as in Sept. 123–4, 385–6 (above) and Rh. 567–8a (n.) οὔκ,  /

/  .

.

309–10. The impression of an uncountable army (cf. 276

) is first given in the introduction to the Achaean catalogue at Il. 2.488–90. Tragic examples include Pers. 39–40 καὶ

) is first given in the introduction to the Achaean catalogue at Il. 2.488–90. Tragic examples include Pers. 39–40 καὶ

/

/

and the exchange between Iolaus and Hyllus’ Servant at Hcld. 668–9

and the exchange between Iolaus and Hyllus’ Servant at Hcld. 668–9

. In phrasing our verses resemble Pers. 429–30

. In phrasing our verses resemble Pers. 429–30

, where the ‘host of

troubles’ stems from the vast number of Persian soldiers that fell (Garvie on 429–32).

, where the ‘host of

troubles’ stems from the vast number of Persian soldiers that fell (Garvie on 429–32).

ἐν ψήϕου λόγῳ / θέσθαι: ‘count by reckoning with pebbles’, i.e. by using an abacus for exact computation (Paley on 309, Porter on 309–10). The periphrasis with θέσθαι (LSJ s.v.  B II 3) is unique and perhaps a little awkward in style (Fraenkel, Rev. 238). More regularly Ag. 570 … ἐν

B II 3) is unique and perhaps a little awkward in style (Fraenkel, Rev. 238). More regularly Ag. 570 … ἐν

and in particular

and in particular  in Hdt. 2.36.4, Ar. Vesp. 656 and Thphr. Char. 14.2. Med. 532

in Hdt. 2.36.4, Ar. Vesp. 656 and Thphr. Char. 14.2. Med. 532

, where

, where  alone means ‘set down, reckon’ (LSJ s.v. τίθημι A II 9 b), should not be compared.

alone means ‘set down, reckon’ (LSJ s.v. τίθημι A II 9 b), should not be compared.

δύναι᾽ ἄν: Δ has the correct generalising second person singular (‘you / one could not …’) with repeated ἄν (KG I 246–7, SD 306 with n. 1). The corruption into δυναίμην (Λ) is partly paralleled at Phoen. 407 (corr. Markland).

: causal-exclamatory: ‘so overwhelming it was to look upon’ (KG II 370–1, Barrett on Hipp. 877–80). The literal sense of

: causal-exclamatory: ‘so overwhelming it was to look upon’ (KG II 370–1, Barrett on Hipp. 877–80). The literal sense of  is ‘unapproachable’ (α + the root stem πλη- / πλα- of πελάζω), with a connotation of ‘terrible, monstrous’ (LSJ s.v. 1), which also suits an enormous host: Lyc. 569

is ‘unapproachable’ (α + the root stem πλη- / πλα- of πελάζω), with a connotation of ‘terrible, monstrous’ (LSJ s.v. 1), which also suits an enormous host: Lyc. 569

(of the Greeks coming to Troy). For a thing ‘too great for sense to grasp’ (Porter on 309–10) cf. Archestr. fr. 190.8–9 SH (describing Phoenician wine)

(of the Greeks coming to Troy). For a thing ‘too great for sense to grasp’ (Porter on 309–10) cf. Archestr. fr. 190.8–9 SH (describing Phoenician wine)

.

.

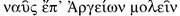

311–13. The Shepherd’s synopsis can profitably be compared to Ba. 781–5  /

/  τ᾽

τ᾽  ταχυπόδων

ταχυπόδων  /

/  /

/

(cf. 264–341n.). Both times ‘the military relationships of the time of writing … are obviously projected onto those of a distant past’ (Best, Thracian Peltasts, 12), but whereas Pentheus musters a typical Greek army, that of Rhesus reflects Thracian conditions, with the cavalry taking pride of place and peltasts supplanting the regular hoplite forces. It would be mistaken, therefore, to think here of the Thracian mercenaries whom the Athenians employed as light-armed skirmishing troops, let alone, as Liapis does, the later Macedonian peltasts with their somewhat larger and heavier shields (cf. Introduction, 19). We are dealing with poetic fiction, not absolute historical fact.

(cf. 264–341n.). Both times ‘the military relationships of the time of writing … are obviously projected onto those of a distant past’ (Best, Thracian Peltasts, 12), but whereas Pentheus musters a typical Greek army, that of Rhesus reflects Thracian conditions, with the cavalry taking pride of place and peltasts supplanting the regular hoplite forces. It would be mistaken, therefore, to think here of the Thracian mercenaries whom the Athenians employed as light-armed skirmishing troops, let alone, as Liapis does, the later Macedonian peltasts with their somewhat larger and heavier shields (cf. Introduction, 19). We are dealing with poetic fiction, not absolute historical fact.

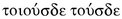

πολλοὶ μὲν … πολλὰ … / πολλοὶ δ᾽᾽ … πολὺς δ᾽: The anaphora emphasises the vastness of Rhesus’ army (Ammendola on 309–13). With lexical variation cf. Phoen. 113 ( …)

…)

ἵπποις, μυρίοις δ᾽ ὅπλοις

ἵπποις, μυρίοις δ᾽ ὅπλοις  For further effect ‘connexion is varied with asyndeton’ (GP 164).

For further effect ‘connexion is varied with asyndeton’ (GP 164).

311. ἱππῆς: Dindorf (PSG1, 222) restored the classical Attic form of the nominative plural ( ). In drama cf. E. Suppl. 666

). In drama cf. E. Suppl. 666

, Phoen. 1146–7

, Phoen. 1146–7

; 1191, Ar. Eq. 225, 242.

; 1191, Ar. Eq. 225, 242.

πελταστῶν τέλη: ‘divisions of peltasts’. Likewise Pers. 47 δίρρυμά  (with Garvie: ‘squadrons of two-poled and three-poled chariots’) and, in a broader sense, already Il. 10.470

(with Garvie: ‘squadrons of two-poled and three-poled chariots’) and, in a broader sense, already Il. 10.470

(LSJ s.v. τέλος I 10 a; cf. G. C. Richards, CQ 10 [1916], 196).

(LSJ s.v. τέλος I 10 a; cf. G. C. Richards, CQ 10 [1916], 196).

While Thracian peltasts are first mentioned by Thucydides (e.g. 2.29.5, 4.28.4, 5.6.4, 7.27.1), the Athenians appear to have been familiar with them from at least the latter half of the sixth century BC (Best, Thracian Peltasts, 4–16, who adds vase-paintings to the description of Xerxes’ Thraco-Bithynian allies at Hdt. 7.75.1; cf. 312–13n.). The use of the term thus provides no terminus post quem for the composition of Rhesus (Ritchie 83, 157), even apart from the Macedonian interpretation rejected in 311–13n.

312–13. ἀτράκτων τοξόται: ‘shooters of arrows’. Our poet may have been inspired by A. fr. 139.2 (Myrmidons)

,340 although ἄτρακτος, ‘arrow’, also occurs at Tr. 714, Phil. 290, Thuc. 4.40.2 (below) and later Leon. Tarent. Ep. 92.4 Gow–Page HE. Originally the word means ‘spindle’, probably from an unattested IE verb ‘to twist, rotate’, which also lies behind Sanskrit tarku- (‘spindle’), Greek

,340 although ἄτρακτος, ‘arrow’, also occurs at Tr. 714, Phil. 290, Thuc. 4.40.2 (below) and later Leon. Tarent. Ep. 92.4 Gow–Page HE. Originally the word means ‘spindle’, probably from an unattested IE verb ‘to twist, rotate’, which also lies behind Sanskrit tarku- (‘spindle’), Greek  (‘unumwunden’) and Latin torquere (GEW, DELG s.v. ἄτρακτος). The metaphorical use for ‘arrow’ developed from similarity of form and movement (around its own axis). There is no sense of contempt involved, except perhaps at Thuc. 4.40.2 (a Spartan to an Athenian)

(‘unumwunden’) and Latin torquere (GEW, DELG s.v. ἄτρακτος). The metaphorical use for ‘arrow’ developed from similarity of form and movement (around its own axis). There is no sense of contempt involved, except perhaps at Thuc. 4.40.2 (a Spartan to an Athenian)

, where ‘spindle’ (a female instrument) stresses the prejudice of the cowardly archer (Hornblower on Thuc. 4.40.2; cf. 32–3n.).

, where ‘spindle’ (a female instrument) stresses the prejudice of the cowardly archer (Hornblower on Thuc. 4.40.2; cf. 32–3n.).

ὄχλος / γυμνής: i.e. slingers, stone- and/or javelin-throwers, mentioned separately from the archers, as at 31 (n.)  ;

;

ἁμαρτῇ: ‘together, at once’. Diggle and Kovacs rightly follow Wackernagel (Sprachliche Untersuchungen, 70–1) in writing  for Attic(?)

for Attic(?)  here (

here ( et O1c) and at Hec. 839. Aristarchus read ἁμαρτή in Homer (Il. 5.656, 18.571, 21.162, Od. 22.81),341 and for archaic and classical Attic

et O1c) and at Hec. 839. Aristarchus read ἁμαρτή in Homer (Il. 5.656, 18.571, 21.162, Od. 22.81),341 and for archaic and classical Attic  is attested at Sol. fr. 33.4 IEG, Hcld.

138 (L: ὁμ- Tr2) and Hipp. 1195 (

is attested at Sol. fr. 33.4 IEG, Hcld.

138 (L: ὁμ- Tr2) and Hipp. 1195 ( 8 [III BC]:

8 [III BC]:  ). The far more frequent verb seems to have made a fuller change early on, given that we have 17 undisputed cases of

). The far more frequent verb seems to have made a fuller change early on, given that we have 17 undisputed cases of  - in tragedy (including three augmented forms: PV 678, OC 1647, Ion 1151) as against one possible of ἁμαρτ- at E. fr. 680 (= Hsch. α 3456 + 3457 Latte). See also Barrett on Hipp. 1194–7.

- in tragedy (including three augmented forms: PV 678, OC 1647, Ion 1151) as against one possible of ἁμαρτ- at E. fr. 680 (= Hsch. α 3456 + 3457 Latte). See also Barrett on Hipp. 1194–7.

Θρῃκίαν ἔχων στολήν: The dress of strangers tends to be commented on as part of their national identification: A. Suppl. 234–7 ποδαπὸν  /

/  /

/  /

/

(with FJW on 234, 235), A. fr. 61 = Ar. Thesm. 136–42, Hec. 734–5, Hyps. fr. I iv.11–14 Bond = E. fr. 752h.11–14, Ar. fr. 311 PCG and, of Greeks, Phil. 223–4, Hcld. 130–1 (with Wilkins).

(with FJW on 234, 235), A. fr. 61 = Ar. Thesm. 136–42, Hec. 734–5, Hyps. fr. I iv.11–14 Bond = E. fr. 752h.11–14, Ar. fr. 311 PCG and, of Greeks, Phil. 223–4, Hcld. 130–1 (with Wilkins).

Thracian warriors typically wore a knee-length tunic covered by a heavy patterned cloak (ζειρά), soft leather boots and on their heads a fox-skin cap with earflaps (ἀλωπεκίς) – all primarily designed for protection against the cold. The accounts of Herodotus (7.75.1) and Xenophon (An. 7.4.4) are confirmed by artistic representations from the later sixth century on (Best, Thracian Peltasts, 6–8 with plts. 2, 3, 4 and, for further literature, Liapis on 311–13).

314–16. The implicit comparison between Rhesus and Achilles (as well as sometimes Ajax and Diomedes) becomes another leitmotif. After 335 (n.), it is resumed by the chorus (370–4, 460–2), Rhesus himself (491, 496–8), Athena (600–4) and the Muse (974–7), stressing Rhesus’ martial prowess and the Trojans’ reverent trust in him. Cf. G. Paduano, SCO 23 (1974), 19–21.

ϕεύγων … ἐκϕυγεῖν: This collocation ‘plays upon the conative aspect of the present and the complexive aspect of the aorist reinforced by … the preposition (‘get away’, ‘succeed in escaping’)’ (Mastronarde on Phoen. 1216  ). So in particular also Ar. Ach. 177

). So in particular also Ar. Ach. 177  and Pl. (?) Hp. Ma. 292a6–7 …

and Pl. (?) Hp. Ma. 292a6–7 …  .

.

οὔθ᾽ ὑποσταθεὶς δορί: Cf. 375b–7 (n.)  /

/  Ἥ- / ρας δαπέδοις χορεύσει. The ‘first’ aorist passive (ὑποσταθ-) looks like a concession to metre, when otherwise the intransitive middle

Ἥ- / ρας δαπέδοις χορεύσει. The ‘first’ aorist passive (ὑποσταθ-) looks like a concession to metre, when otherwise the intransitive middle  is the rule (LSJ s.v. ὑϕίστημι B with IV 1 ‘resist, withstand’; cf. Fraenkel, Rev. 239). Similarly e.g.

is the rule (LSJ s.v. ὑϕίστημι B with IV 1 ‘resist, withstand’; cf. Fraenkel, Rev. 239). Similarly e.g.  (LSJ s.v.

(LSJ s.v.  II 1, 3 ‘stand against, withstand, resist’), which in classical times has ἀντισταθ- only at Hdt. 5.72.2.

II 1, 3 ‘stand against, withstand, resist’), which in classical times has ἀντισταθ- only at Hdt. 5.72.2.

The coupling with  in our line is natural: Cyc. 198–200

in our line is natural: Cyc. 198–200

, /

, /  ,

,  /

/  , Phoen. 1470–1, Thuc. 1.144.4, 4.54.2, Plut. Demetr. 25.1.

, Phoen. 1470–1, Thuc. 1.144.4, 4.54.2, Plut. Demetr. 25.1.

317–18. ‘When the gods stand firm for our citizens, fortune moves easily towards success.’

This kind of translation suits both the context and the Greek better than anything implying a rapid change from misfortune (ξυμϕορά) to good luck (τἀγαθά). ‘The chorus mean, that Hector’s recent success, showing the favour of heaven to the Trojans, has now been crowned by this second piece of luck, the arrival of a powerful ally’ (Paley on 317). Yet unlike their commander, they remain conscious of the mutability of fate (332) and eventually are forced to recant their optimistic statement here: 882–4 (n.)  /

/

/

/  ;

;

Initially the expression resembles Pers. 601

…, and most words are used in comparable ways elsewhere (below). But one may wonder whether the whole sententia is in the best of Greek tragic style (Fraenkel, Rev. 238).

…, and most words are used in comparable ways elsewhere (below). But one may wonder whether the whole sententia is in the best of Greek tragic style (Fraenkel, Rev. 238).

εὐσταθῶσι: ‘to be steady, stable’ (LSJ s.v. 1), attested only here in classical Greek. The sense corresponds to that of  at Xen. HG 5.2.23

at Xen. HG 5.2.23

(LSJ s.v.

(LSJ s.v.  B II 2), rather than Plut. Aet. Rom. 72.281b

B II 2), rather than Plut. Aet. Rom. 72.281b

(of Roman augury), which commentators tend to quote. Paley and Feickert (on 317) suspect an allusion also to the belief that the gods leave a city which has fallen or is about to fall. Note particularly Sept. 217–18

(of Roman augury), which commentators tend to quote. Paley and Feickert (on 317) suspect an allusion also to the belief that the gods leave a city which has fallen or is about to fall. Note particularly Sept. 217–18  /

/

and 318–20 καὶ πόλεως ῥύτορες <ἔστ᾽> / εὔεδροί τε

and 318–20 καὶ πόλεως ῥύτορες <ἔστ᾽> / εὔεδροί τε  /

/  (with Hutchinson on 318–19). Other examples in Hutchinson on Sept. 304.

(with Hutchinson on 318–19). Other examples in Hutchinson on Sept. 304.

ἕρπει: for the course of time or events also e.g. Pi. Nem. 7.67–8

/

/  , Ai. 1087

, Ai. 1087  (i.e. good and bad fortune) and IT 476–7

(i.e. good and bad fortune) and IT 476–7  /

/

.

.

κατάντης: literally ‘downwards’, implying quick and easy movement on a way (Ar. Ran. 127), not the tipping of a balance, as Palmer (CR 4 [1890], 229) and others surmised. The word is again unique in tragedy. But its opposite  occurs metaphorically at Med. 303–5

occurs metaphorically at Med. 303–5  / […] /

/ […] /  (‘adverse, an obstacle’), 381, IT 1012–13 and Or. 790, while

(‘adverse, an obstacle’), 381, IT 1012–13 and Or. 790, while  (for ἀνέντες) has been proposed at HF 122 (see Bond on 121–3). Ritchie (215) adds Alc. 500

(for ἀνέντες) has been proposed at HF 122 (see Bond on 121–3). Ritchie (215) adds Alc. 500  (i.e. Heracles’ δαίμων).

(i.e. Heracles’ δαίμων).

ξυμϕορά: without a qualifying epithet in a good sense, as in Ag. 24, S. El. 1230 (with Finglass) and Sim. fr. 512 = 1 Poltera  συμϕοραῖς (quoted in Ar. Eq. 406).

συμϕοραῖς (quoted in Ar. Eq. 406).  ‘in itself [is] neither good

nor bad but used most frequently of unfavourable events’ (Fraenkel on Ag. 24).

‘in itself [is] neither good

nor bad but used most frequently of unfavourable events’ (Fraenkel on Ag. 24).

319–26. Confident as ever, Hector greets the news of Rhesus’ approach with a variation on the commonplace that friends are abundant in success (Feickert on 320). The indignant little speech foreshadows the first part of the agon (388–526, 388–453nn.), where Hector berates Rhesus for coming late, despite the many embassies he had sent: 399–403 (cf. the Muse at 935–7). Tensions between the Trojans and their allies occasionally surface in the Iliad and may have been a feature of the older epic tradition (Edwards on Il. 17.219–32; cf. 251b–2, 762–9, 859a nn.).

319–20.  τοὐμὸν εὐτυχεῖ δόρυ: 60b–2n.

τοὐμὸν εὐτυχεῖ δόρυ: 60b–2n.

καὶ Ζεὺς πρὸς ἡμῶν ἐστιν: Cf. 52–84, 317–18nn. and, for Hector’s failure to understand that the tide of war will turn, 983–96, 995b–6nn.

321–3. ‘But we do not need those who have not toiled with us all the long time that the violent winds of Ares were blowing with full force and rending the sails of our ship of state.’

321b–2a. οἵτινες πάλαι / μὴ ξυμπονοῦσιν: For πάλαι with a present tense for an action that continues from the past into the present (KG I 134–5, SD 273–4, LSJ s.v. I 1) cf. 329, 396 and 414. Only L has the correct indicative ξυμπονοῦσιν (ξυμπονῶσιν ΔQgB) with μή in a generalising relative clause (KG II 185–6, 422).

322b–3. ἡνίκ᾽ ἐξώστης Ἄρης / ἔθραυε  τῆσδε γῆς μέγας

τῆσδε γῆς μέγας  As in Sept. 62–4 σὺ δ᾽ ὥστε ναὸς κεδνὸς οἰακοστρόϕος / ϕάρξαι πόλισμα,

As in Sept. 62–4 σὺ δ᾽ ὥστε ναὸς κεδνὸς οἰακοστρόϕος / ϕάρξαι πόλισμα,

(with Hutchinson), the ‘Ship of State’ image (246–9a n.) is here amalgamated with that of Ares’ breath as a furious gale. The latter recurs twice in Seven against Thebes (112–15, 343–4 [~ Ant. 135–7, of Capaneus]) and has a precedent in the comparison of Ares to a storm-wind at Il. 20.51 αὖε δ᾽

(with Hutchinson), the ‘Ship of State’ image (246–9a n.) is here amalgamated with that of Ares’ breath as a furious gale. The latter recurs twice in Seven against Thebes (112–15, 343–4 [~ Ant. 135–7, of Capaneus]) and has a precedent in the comparison of Ares to a storm-wind at Il. 20.51 αὖε δ᾽  ἑτέρωθεν,

ἑτέρωθεν,

ἶσος (although the formula is also applied to humans: Il. 11.747 … κελαινῇ

ἶσος (although the formula is also applied to humans: Il. 11.747 … κελαινῇ  ἶσος, 12.375). It contrasts with the gentle, fragrant breeze of more benevolent gods, which is given a twist in 385–7 (n.).

ἶσος, 12.375). It contrasts with the gentle, fragrant breeze of more benevolent gods, which is given a twist in 385–7 (n.).

ἐξώστης of a wind that drives ships off course (ΣV Rh. 322 [II 334.10–11 Schwartz = 93 Merro], LSJ s.v. ἐξώστης 2) seems to be an Ionism: Hdt. 2.113.1, Hp. VM 9.4 (E. Fraenkel, Nomina agentis I, 241; cf. Fraenkel, Rev. 239, Rh. 810b–12a n.). The verb, however, was regularly so used in Attic: Cyc. 278–9  / σὴν γαῖαν ἐξωσθέντες ἥκομεν, Κύκλωψ, Thuc. 2.90.5, 7.52.2, 8.104.4 (LSJ s.v.

/ σὴν γαῖαν ἐξωσθέντες ἥκομεν, Κύκλωψ, Thuc. 2.90.5, 7.52.2, 8.104.4 (LSJ s.v.  II).

II).

ἔθραυε λαίϕη: As  (‘break in pieces, shatter’) is not entirely fitting for sails, there may be an echo of Eum. 553–7 τὸν

(‘break in pieces, shatter’) is not entirely fitting for sails, there may be an echo of Eum. 553–7 τὸν

ϕαμι … 555b ξὺν χρόνῳ καθήσειν / λαῖϕος, ὅταν λάβῃ πόνος, /

ϕαμι … 555b ξὺν χρόνῳ καθήσειν / λαῖϕος, ὅταν λάβῃ πόνος, /  (‘the yard-arm’, i.e. the crossbeam from which the sail was hung). V’s ‘durative’ imperfect is correct

(‘the yard-arm’, i.e. the crossbeam from which the sail was hung). V’s ‘durative’ imperfect is correct  OgB:

OgB:  Λ).

Λ).

μέγας πνέων: Cf. Thuc. 6.104.2 καὶ ἁρπασθεὶς ὑπ᾽  … ὃς

… ὃς  μέγας and, of a person identifying himself with a storm, Ar. Eq. 430

μέγας and, of a person identifying himself with a storm, Ar. Eq. 430  γάρ σοι

γάρ σοι  καὶ

καὶ  καθιείς. Tragic instances of

καθιείς. Tragic instances of  with μέγα /

with μέγα /  are metaphorical (Andr. 189, Tro. 1277, Ba. 640).

are metaphorical (Andr. 189, Tro. 1277, Ba. 640).

324. ἦν refers to the time at which Rhesus professed his allegiance.

325–6. ‘For he has come to the feast, without helping the hunters catch the prey or sharing our toils with his spear.’

The hunting metaphor looks proverbial, although it entered only the medieval gE (325). As the thought returns to the literal world of fighting, λεία acquires a trace of its ordinary meaning ‘booty’ (LSJ s.v. (B) 1), suggesting that Hector does not wish to share the spoils (and glory) of a war he believes he has won alone (cf. Feickert on 326).

κυνηγέταις: Elmsley1 (on Hcld. 694) proposed κυνηγέτης, which is also now found in gE. But unlike at Hcld. 694  οὖν

οὖν  τευχέων ἄτερ ϕανῇ;

τευχέων ἄτερ ϕανῇ;  Elmsley:

Elmsley:  L), the dative is more trenchant here (it was the Trojans who did all the hard work). Moreover, an assimilative error seems likelier with παρών in the same line.

L), the dative is more trenchant here (it was the Trojans who did all the hard work). Moreover, an assimilative error seems likelier with παρών in the same line.

οὐδὲ συγκαμὼν δορί: Cf. Hector at 396–7 πάλαι πάλαι  τῇδε συγκάμνειν χθονί / ἐλθόντα.

τῇδε συγκάμνειν χθονί / ἐλθόντα.

327–8. ἀτίζεις: 251b–2n.

κἀπίμομϕος: here active, ‘inclined to blame’ (LSJ s.v.  I). The adjective is passive (‘blameable, unlucky’) at Ag. 551–3 ταῦτα δ᾽ ἐν πολλῷ χρόνῳ /

I). The adjective is passive (‘blameable, unlucky’) at Ag. 551–3 ταῦτα δ᾽ ἐν πολλῷ χρόνῳ /  μέν

μέν  ἂν

ἂν  εὐπετῶς ἔχειν, /

εὐπετῶς ἔχειν, /  δ᾽

δ᾽  κἀπίμομϕα and, if correct, Cho. 829–30 καὶ πέραιν᾽ / οὐκ ἐπίμομϕον ἄταν (see West’s apparatus and Garvie on Cho. 827–30).

κἀπίμομϕα and, if correct, Cho. 829–30 καὶ πέραιν᾽ / οὐκ ἐπίμομϕον ἄταν (see West’s apparatus and Garvie on Cho. 827–30).

δέχου δέ: In view of 301 ὥστε δαίμονα (301b–8, 301b–2nn.), Strohm (270 with n. 5) compares the Herdsman at Ba. 769–70  δαίμον᾽ οὖν τόνδ᾽, ὅστις ἔστ᾽, ὦ δέσποτα, / δέχου

δαίμον᾽ οὖν τόνδ᾽, ὅστις ἔστ᾽, ὦ δέσποτα, / δέχου  (264–341n.).

(264–341n.).

329. The nearest parallel is Alc. 383  οἱ

οἱ  σέθεν. Ritchie (202 n. 1) fails to see the difference hinted at by Dale (on Alc. 383), namely that ἀρκέω here means ‘suffice’ not only in numerical terms, but also in the sense ‘to be strong enough’ (cf. Hcld. 574–6 καὶ δίδασκέ

σέθεν. Ritchie (202 n. 1) fails to see the difference hinted at by Dale (on Alc. 383), namely that ἀρκέω here means ‘suffice’ not only in numerical terms, but also in the sense ‘to be strong enough’ (cf. Hcld. 574–6 καὶ δίδασκέ  /

/  παῖδας, ἐς τὸ πᾶν σοϕούς, / ὥσπερ σύ,

παῖδας, ἐς τὸ πᾶν σοϕούς, / ὥσπερ σύ,  μᾶλλον·

μᾶλλον·  γάρ). But he rightly draws attention to the use of the article, which puts special emphasis on the person(s) concerned (Feickert on 329).

γάρ). But he rightly draws attention to the use of the article, which puts special emphasis on the person(s) concerned (Feickert on 329).

πάλαι: 321b–2a n. Λ’s πόλιν intruded from the end of 328.

330–1. πέποιθας … / πέποιθα: Hector’s misguided confidence is sustained to the end: 989b–92 (n.) ὡς … / …  /

/  Τρωσί θ᾽

Τρωσί θ᾽  ἐλευθέραν /

ἐλευθέραν /

στείχουσαν

στείχουσαν  ϕέρειν. For the ominous connotations of

ϕέρειν. For the ominous connotations of  in Rhesus see 65–6n.

in Rhesus see 65–6n.

τοὐπιὸν σέλας θεοῦ: Cf. Med. 352  ᾽πιοῦσα

᾽πιοῦσα  … θεοῦ, E. Suppl. 469 … πρὶν θεοῦ δῦναι σέλας and Tro. 860 ὦ καλλιϕεγγὲς

… θεοῦ, E. Suppl. 469 … πρὶν θεοῦ δῦναι σέλας and Tro. 860 ὦ καλλιϕεγγὲς  τόδε. Euripides had a penchant for attributive ἐπιών (‘coming, following’) and periphrases for sun- or daylight. The former is exemplified also by Alc. 173–4 τοὐπιόν / κακόν, IT 313, Or. 1659, IA 651, E. frr. 135.2, 1073.6,342 the latter by Alc. 722 τὸ

τόδε. Euripides had a penchant for attributive ἐπιών (‘coming, following’) and periphrases for sun- or daylight. The former is exemplified also by Alc. 173–4 τοὐπιόν / κακόν, IT 313, Or. 1659, IA 651, E. frr. 135.2, 1073.6,342 the latter by Alc. 722 τὸ  … τοῦ θεοῦ, Hcld. 749–50, Ion 1467 ἀελίου … λαμπάσιν and Or. 1025. Diggle (on Phaeth. 6, Euripidea, 405–6) cites further tragic cases for

… τοῦ θεοῦ, Hcld. 749–50, Ion 1467 ἀελίου … λαμπάσιν and Or. 1025. Diggle (on Phaeth. 6, Euripidea, 405–6) cites further tragic cases for  being replaced with θεός (properly ‘the relevant god’, i.e. the sun).

being replaced with θεός (properly ‘the relevant god’, i.e. the sun).

332. πόλλ᾽᾽ ἀναστρέϕει θεός: 317–18, 882–4nn. The idea of the gods ‘turning over’ the affairs of men is frequent in Euripides: E. Suppl. 331 ὁ γὰρ θεὸς  πάλιν (with

πάλιν (with  preceding, as here), Hipp. 981–2, Andr. 1007–8

preceding, as here), Hipp. 981–2, Andr. 1007–8  γὰρ ἀνδρῶν μοῖραν εἰς ἀναστροϕήν / δαίμων δίδωσι, E. fr. 301.1, Hel. 712–13 εὖ δέ

γὰρ ἀνδρῶν μοῖραν εἰς ἀναστροϕήν / δαίμων δίδωσι, E. fr. 301.1, Hel. 712–13 εὖ δέ

(sc. ὁ θεὸς) / ἐκεῖσε

(sc. ὁ θεὸς) / ἐκεῖσε  ἀναϕέρων, E. fr. 536. Elsewhere Eum. 650–1 (Zeus) τὰ δ᾽ ἄλλα πάντ᾽ ἄνω τε καὶ κάτω / στρέϕων

ἀναϕέρων, E. fr. 536. Elsewhere Eum. 650–1 (Zeus) τὰ δ᾽ ἄλλα πάντ᾽ ἄνω τε καὶ κάτω / στρέϕων  (with Sommerstein). Cf. Collard on E. Suppl. 330—1a and Liapis on 330–2 on the underlying ‘Wheel of Fortune’ image.

(with Sommerstein). Cf. Collard on E. Suppl. 330—1a and Liapis on 330–2 on the underlying ‘Wheel of Fortune’ image.

333–41. The transmitted line order and speaker distributions make no sense. 333 must belong to Hector (Ω), and 334–5, given to the coryphaeus and the Shepherd respectively, would follow well. But 336–8, which L alone rightly assigns to Hector, are no cogent reply to the preceding objections and at any rate cannot come immediately before Hector’s (Q) final decision to accept Rhesus as an ally (339–41).

Nauck’s transposition of 336–8 after 333 (Euripideische Studien II, 171–3) is the easiest solution. Hector still disapproves of tardy friends (333), but in order perhaps to avert the wrath of Zeus Ξένιος concedes admitting Rhesus as a guest (336–7n.). Further advice by the chorus-leader and the Shepherd (334–5n.) – for 339 (n.)  τ᾽ … καὶ σὺ … refers to two different persons – then persuades him to take the second step (339–41). If his change of mind seems even more abrupt than in the Aeneas scene (264–341n.), the imperfection must probably be laid at our poet’s door. But it is possible that a few lines were lost after 335 (n.), which in the way of Il. 16.278–83 (Patroclus) and 18.197–238 (Achilles) expanded on the fear Rhesus would strike into the Greek host. 343 Apart from making Hector’s reaction more plausible, a short speech by the

Shepherd would also fit the type of messenger who stays on to influence the course of the play (804–81n.). On the other hand, our poet may have intended a single put-down remark like that of Iolaus at Hcld. 687

τ᾽ … καὶ σὺ … refers to two different persons – then persuades him to take the second step (339–41). If his change of mind seems even more abrupt than in the Aeneas scene (264–341n.), the imperfection must probably be laid at our poet’s door. But it is possible that a few lines were lost after 335 (n.), which in the way of Il. 16.278–83 (Patroclus) and 18.197–238 (Achilles) expanded on the fear Rhesus would strike into the Greek host. 343 Apart from making Hector’s reaction more plausible, a short speech by the

Shepherd would also fit the type of messenger who stays on to influence the course of the play (804–81n.). On the other hand, our poet may have intended a single put-down remark like that of Iolaus at Hcld. 687  ἔμ᾽

ἔμ᾽  ἀνέξεται.

ἀνέξεται.

Zanetto’s transposition (cf. Ciclope, Reso, 145–6 n. 46) can be rejected at once. Placing 336–8 after 328 and giving 338 (punctuated as a question) to the coryphaeus does nothing to improve the logic of the passage. 329–35 awkwardly follow 338 (which is not answered by 329), and ‘Hector’s capitulation in 336–7 … would come as a complete surprise after only two lines of argumentation by the chorus (327–8)’ (Liapis, ‘Notes’, 66). The creation of straight stichomythia is a negligible advantage.

West (apud Klyve on 336–41 [p. 225]) proposed to treat 336–8 and 339–41 as alternative versions, one of which he would delete. From the subsequent ode it is evident that 336–8 could not stand on their own, since the chorus express hopes in Rhesus too high for him to have been admitted merely as a guest (Klyve). Without those lines the discussion would in a clear and coherent fashion centre on the question of military allegiance, and if there was a lacuna of the kind discussed above, Hector’s turn-about would appear no less abrupt than in Nauck’s correction of the paradosis. But it is difficult to explain how 336–8 could have entered the text, unless a redactor (desiring further conflict perhaps) interpolated them for a revival of the play.344 This, however, would have worked only after 333, bringing us back to the order restored by Nauck. Short of conclusive evidence, it seems best to accept it as what our poet wrote.

333. ‘I hate it if a man comes too late to help his friends.’

Hector’s summary complaint, which he repeats almost literally at 411b–12 (n.), resembles Ar. Ran. 1427–8 ~ E. frr. [886] [887] (‘Euripides’ on Alcibiades)  πολίτην, ὅστις ὠϕελεῖν

πολίτην, ὅστις ὠϕελεῖν  /

/  (Hamaker:

(Hamaker:  R, Suda σ 511:

R, Suda σ 511:  VAKL). The second verse-half echoes Phoen. 1432–3 …

VAKL). The second verse-half echoes Phoen. 1432–3 …  τέκν᾽, ὑστέρα

τέκν᾽, ὑστέρα  / πάρειμι. Euripides liked

/ πάρειμι. Euripides liked  (also Hcld. 339, El. 963, Or. 1290/1) and

(also Hcld. 339, El. 963, Or. 1290/1) and  (Hcld. 121, Hipp. 776, Or. 1356, 1476, 1510, 1622), which elsewhere before the Imperial period is found only in A. fr. 46c.6 (Diktyoulkoi?) and, perhaps as Euripidean imitations (Liapis on 333), Lyc. 923 and Ezek. 232. Its use here remains true to the basic ‘run in response to a call for help’ (Willink on Or. 1288–91).

(Hcld. 121, Hipp. 776, Or. 1356, 1476, 1510, 1622), which elsewhere before the Imperial period is found only in A. fr. 46c.6 (Diktyoulkoi?) and, perhaps as Euripidean imitations (Liapis on 333), Lyc. 923 and Ezek. 232. Its use here remains true to the basic ‘run in response to a call for help’ (Willink on Or. 1288–91).

336–7. ὃ δ᾽ οὖν is Nauck’s idiomatic reinterpretation of the transmitted ὅδ᾽  (Euripideische Studien II, 173), in which he rightly prefers

to leave the demonstrative accented (cf. West, ed. Aeschylus, XLIX). For ‘permissive’ δ᾽ οὖν (with a second- or third-person imperative) see GP 466–7; in mid-speech also OC 1205 and Ar. Lys. 491. The tone is petulant here, condescending in 868

(Euripideische Studien II, 173), in which he rightly prefers

to leave the demonstrative accented (cf. West, ed. Aeschylus, XLIX). For ‘permissive’ δ᾽ οὖν (with a second- or third-person imperative) see GP 466–7; in mid-speech also OC 1205 and Ar. Lys. 491. The tone is petulant here, condescending in 868  δ᾽ οὖν

δ᾽ οὖν  ταῦτ᾽, ἐπείπερ σοι δοκεῖ.

ταῦτ᾽, ἐπείπερ σοι δοκεῖ.

ξένος … πρὸς τράπεζαν … ξένων: The polyptoton, here emphasised by the way it frames the line, expresses the mutual ties (and duties) of hospitality: Cho. 702–3 τί γάρ / ξένου ξένοισίν  (~ Hdt. 7.237.3), Eum. 660–1 ἣ δ᾽ ἅπερ ξένῳ ξένη / ἔσωσεν ἔρνος, IA [604—6] and, in general, Denniston on E. El. 337, Gygli-Wyss, Polyptoton, 64–8, 112–15, 127 with n. 3, West, IEPM 113–14

(~ Hdt. 7.237.3), Eum. 660–1 ἣ δ᾽ ἅπερ ξένῳ ξένη / ἔσωσεν ἔρνος, IA [604—6] and, in general, Denniston on E. El. 337, Gygli-Wyss, Polyptoton, 64–8, 112–15, 127 with n. 3, West, IEPM 113–14

For τράπεζαν … ξένων cf. Od. 14.158 = 17.155 ξενίη …  and Ag. 401/2

and Ag. 401/2  τράπεζαν. See also 841b–2n.

τράπεζαν. See also 841b–2n.

338. ‘For he has utterly lost the gratitude of Priam’s sons.’

The sentiment corresponds to Men. fr. 702 PCG ἅμ᾽

χάρις / ἣν δεόμενος

χάρις / ἣν δεόμενος  ἀθάνατον ἕξειν ἔϕη, the first verse of which became proverbial early on (PCG VI.2, 347). This, and not our passage, appears to be alluded to in Eust. 822.4–5 (on Il. 10.519–25) ὀκνοῦσι γὰρ ἴσως

ἀθάνατον ἕξειν ἔϕη, the first verse of which became proverbial early on (PCG VI.2, 347). This, and not our passage, appears to be alluded to in Eust. 822.4–5 (on Il. 10.519–25) ὀκνοῦσι γὰρ ἴσως

νεηλύδων,

νεηλύδων,  ἀπώναντο. καὶ εἰ τοῦτο, ἄρα

ἀπώναντο. καὶ εἰ τοῦτο, ἄρα

ἐκ

ἐκ  (cf. Introduction 46 with n. 96).

(cf. Introduction 46 with n. 96).

διώλετο: ΔQ. Liapis alone prefers L’s ἀπώλετο, on the ground that  tends to emphasise ‘the role of an external agency’, while (ἀπ)όλλυμαι ‘can mean merely ‘to cease to exist, to fail” (‘Notes’, 67). But the stronger verb is desired here, suggesting that Rhesus himself has forfeited Hector’s gratitude (Paley on 338). Cf. Pers. 589–90 βασιλεία γὰρ

tends to emphasise ‘the role of an external agency’, while (ἀπ)όλλυμαι ‘can mean merely ‘to cease to exist, to fail” (‘Notes’, 67). But the stronger verb is desired here, suggesting that Rhesus himself has forfeited Hector’s gratitude (Paley on 338). Cf. Pers. 589–90 βασιλεία γὰρ  ἰσχύς (i.e. through Xerxes’ failure) as against the ‘neutral’ S. fr. 920 ἀμνήμονος γὰρ

ἰσχύς (i.e. through Xerxes’ failure) as against the ‘neutral’ S. fr. 920 ἀμνήμονος γὰρ  ὄλλυται χάρις, Hcld. 437–8 εἰ θεοῖσι δὴ

ὄλλυται χάρις, Hcld. 437–8 εἰ θεοῖσι δὴ  /

/  ἔμ᾽,

ἔμ᾽,  σοί γ᾽

σοί γ᾽  χάρις and E. fr. 736.5–6

χάρις and E. fr. 736.5–6  δ᾽ ἐν

δ᾽ ἐν  χάρις / ἀπόλωλ᾽,

χάρις / ἀπόλωλ᾽,

ἐκ

ἐκ  θάνῃ.

θάνῃ.

334–5. For the need to divide the couplet between two speakers see 333–41n. The sententious admonition not to scorn allies (334) suits the coryphaeus, who had already said as much in 327–8. And the Shepherd has personal experience of Rhesus’ fearsome effect (287–9, 306–8). See Nauck, Euripideische Studien II, 172–3.

334. ἐπίϕθονον: sc. ἐστίν (‘it is hateful …’). Cf. Hcld. 202–3 … καὶ γὰρ οὖν  / λίαν ἐπαινεῖν

/ λίαν ἐπαινεῖν  and Ar. Eq. 1274

and Ar. Eq. 1274

οὐδέν

οὐδέν  ἐπίϕθονον. The arrogance of rejecting an ally was likely to arouse resentment in both men and gods (Liapis on 334). See further 342–5, 342–3, 455b–7nn.

ἐπίϕθονον. The arrogance of rejecting an ally was likely to arouse resentment in both men and gods (Liapis on 334). See further 342–5, 342–3, 455b–7nn.

335. Two particular epic precedents exist. At Il. 16.278–83 Patroclus frightens the Trojans in Achilles’ panoply, and at Il. 18.197–238 the hero himself achieves that end, supernaturally enhanced by Athena in aspect and voice. Our poet thus resumes the connection of Rhesus with Achilles (314–16n.) in a way that intimates divine support for him.

It is possible that Aelius Aristides recalled Rhesus in Or. 1.106 Lenz–Behr (of Darius’ Persians)  δ᾽

δ᾽  παρασκευῆς καὶ

παρασκευῆς καὶ  ποιουμένων,

ποιουμένων,  ἐξαρκεῖν ἐδόκει

ἐξαρκεῖν ἐδόκει  μόνον (Vater on 325; cf. Introduction, 45).

μόνον (Vater on 325; cf. Introduction, 45).

ϕόβος: ‘an object of fear’, as in e.g. A. Suppl. 479  γὰρ ἐν

γὰρ ἐν  (i.e. Zeus), OC 1651–2

(i.e. Zeus), OC 1651–2  τινος /

τινος /  οὐδ᾽ ἀνασχέτου βλέπειν, Or. 1518 ὧδε

οὐδ᾽ ἀνασχέτου βλέπειν, Or. 1518 ὧδε  Τροίᾳ σίδηρος πᾶσι Φρυξὶν

Τροίᾳ σίδηρος πᾶσι Φρυξὶν  ϕόβος; (FJW on A. Suppl. 479) and Rh. 52 (n.) … καίπερ

ϕόβος; (FJW on A. Suppl. 479) and Rh. 52 (n.) … καίπερ  ϕόβον. The Iliadic parallels (above) tell against capitalising the noun with, tentatively, Liapis (‘Notes’, 67–8).

ϕόβον. The Iliadic parallels (above) tell against capitalising the noun with, tentatively, Liapis (‘Notes’, 67–8).

ὀϕθείς: VΛ. O’s  arose from ἦλθε in 336.

arose from ἦλθε in 336.

339. ‘You give good advice, and you consider <what is advanta-geous > in time.’

σύ τ᾽ … καὶ σύ: 333–41, 334–5nn. The choice of words suggests that the chorus-leader is addressed first. Usually the last speaker gets that privilege and/or a clarifying vocative is added: IT 655–6 ἔτι γὰρ  ϕρήν, / σὲ

ϕρήν, / σὲ  σ᾽

σ᾽  γόοις (i.e. Pylades – Orestes), 1079 (Orestes – Pylades), OT 637 οὐκ εἶ

γόοις (i.e. Pylades – Orestes), 1079 (Orestes – Pylades), OT 637 οὐκ εἶ  τ᾽

τ᾽  σύ τε, Κρέον, τὰς σὰς στέγας, Ant. 724–5, 1340–4, Phoen. 568 (cf. Nauck, Euripideische Studien II, 172 n. 1). But on stage a turn of the head or some other gesture would have sufficed.

σύ τε, Κρέον, τὰς σὰς στέγας, Ant. 724–5, 1340–4, Phoen. 568 (cf. Nauck, Euripideische Studien II, 172 n. 1). But on stage a turn of the head or some other gesture would have sufficed.

καιρίως σκοπεῖς: For absolute σκοπέω, ‘look to, consider’, with an adverb or adverbial phrase cf. Phoen. 155 ὃ καὶ δέδοικα

θεοί (with Mastronarde), Pl. Smp. 219a1–2

θεοί (with Mastronarde), Pl. Smp. 219a1–2  … ἄμεινον σκόπει,

… ἄμεινον σκόπει,  and probably A. Suppl. 232

and probably A. Suppl. 232  κἀμείβεσθε

κἀμείβεσθε  (with FJW).

(with FJW).

Some scholars refer the phrase to the Shepherd’s observation of Rhesus’ coming: ‘… and you were keeping your eyes open at the right time’ (Morwood). But neither the context nor the tense of the verb recommend this view.

340–1. χρυσοτευχής: a hapax, which may have been coined for the occasion after Il. 10.439 τεύχεα δὲ χρύσεια (305–6a n.). Note the equally unparalleled E. Suppl. 999  Καπανέως.

Καπανέως.

ἀγγέλου λόγων ‘in view of what the messenger said’, as at Tro. 912–13 τῶν σῶν δ᾽ οὕνεχ᾽ …

ἀγγέλου λόγων ‘in view of what the messenger said’, as at Tro. 912–13 τῶν σῶν δ᾽ οὕνεχ᾽ …  / δώσω

/ δώσω  (Klyve on 340–1). The alternative, namely to refer the clause to

(Klyve on 340–1). The alternative, namely to refer the clause to  alone (‘as far as the messenger’s words are concerned’) has been discounted by Pearson (CQ 11 [1917], 60 + CQ 12 [1918], 79) on the ground that elsewhere this idiom indicates an entirely objective cause: e.g. S. El. 786–7 νῦν δ᾽

alone (‘as far as the messenger’s words are concerned’) has been discounted by Pearson (CQ 11 [1917], 60 + CQ 12 [1918], 79) on the ground that elsewhere this idiom indicates an entirely objective cause: e.g. S. El. 786–7 νῦν δ᾽  / οὕνεχ᾽ ἡμερεύσομεν, Phil. 774, OC 22, Hipp. 421–3

/ οὕνεχ᾽ ἡμερεύσομεν, Phil. 774, OC 22, Hipp. 421–3  … / … οἰκοῖεν

… / … οἰκοῖεν  /

/

μητρὸς οὕνεκ᾽ εὐκλεεῖς, Hel. 885–6, Phoen. 865–6, Or. 84 (LSJ s.v. ἕνεκα I 2). And while one need not perhaps be so strict (cf. W. H. Porter, CQ 11 [1917], 159–60), a half-sarcastic remark on Rhesus’ golden armour seems to be less relevant here than a (grudging) recognition of his potential value for Troy.

μητρὸς οὕνεκ᾽ εὐκλεεῖς, Hel. 885–6, Phoen. 865–6, Or. 84 (LSJ s.v. ἕνεκα I 2). And while one need not perhaps be so strict (cf. W. H. Porter, CQ 11 [1917], 159–60), a half-sarcastic remark on Rhesus’ golden armour seems to be less relevant here than a (grudging) recognition of his potential value for Troy.

On οὕνεκα as a preposition in drama see LSJ s.v. II, Barrett on Hipp. 453–6 and West, ed. Aeschylus, XLIX.

342–79. Even more than 224–63 (n.) this joyous ode which greets Rhesus’ imminent arrival shows the elements of a cletic hymn (cf. Fenik, Iliad X, 26–7 n. 3, Furley–Bremer, Greek Hymns I, 50–63). After an apotropaic prayer to Adrasteia (342–5, 342–3nn.) and declaring their intention to sing Rhesus’ praise (344–5n.), the chorus ‘invoke’ him as the son of the Thracian river god Strymon, whose waters impregnated a virgin Muse (346–8a, 348b–51a, 351b–4nn.). The so-called ‘eulogy’ distinguishes Rhesus with titles derived from different aspects of Zeus and with his dramatically most important attribute, the marvellous horses (355–6, 357–9nn.).

In the second strophe we get a nostalgic picture of Troy enjoying the pleasures of peace (360–7n.), which the chorus hope Rhesus will restore (368–9n.). This develops out of his identification with Zeus Ἐλευθέριος (357–9n.) and in the hymn takes the place of the usual myth and/or here inapplicable reminder of the god’s previous service. The actual ‘prayer’ occupies the final stanza – forcefully introduced by ἐλθὲ  (370–2a n.). As in the Shepherd’s imagination (315–16), Rhesus is to confront Achilles and thus, it is implied, to defeat the Greeks once and for all (370–5a, 373b–5a, 375b–7nn.). The confident imperatives and future indicatives (370, 377, 379) leave no doubt of the chorus’ trust at this point; contrast their misgivings in face of his arrogance upon arrival in 454–66 (n.).

(370–2a n.). As in the Shepherd’s imagination (315–16), Rhesus is to confront Achilles and thus, it is implied, to defeat the Greeks once and for all (370–5a, 373b–5a, 375b–7nn.). The confident imperatives and future indicatives (370, 377, 379) leave no doubt of the chorus’ trust at this point; contrast their misgivings in face of his arrogance upon arrival in 454–66 (n.).

Linguistically the hymnic style is evoked by anaphora (346–8a, 357–9nn.), a descriptive relative clause (351b–4n.), second-person invocations (355–6n.) and, reflecting choral-lyric rather than tragic practice, the syntactical overlap between the first strophe and antistrophe (348b–51a n.). All these set the tone for the unprecedented identification of a mortal with Zeus and, in the following anapaests, Ares ‘himself ’ (385–7n.).

By casting Rhesus’ arrival in the light of a divine epiphany, the chorus not only surpass the Shepherd’s excited description – including the epicising  in 301 (301b–2n.) – but also their earlier exaltation of Dolon (224–63), who after all required the help of Apollo and Hermes to succeed (cf. Klyve on 342–87 [pp. 229–31]). In the course of the ode both the Trojan hopes and the audience’s expectation of Rhesus reach their peak, although for the latter sinister undercurrents again come in.

The dazzling Thracian will no more ‘return home’ (367–9; cf. 450)345 than the hapless Dolon (235–7), and instead of witnessing symposia again, Troy will suffer the fate envisaged for the Greeks (357–9, 375b–7nn.).

in 301 (301b–2n.) – but also their earlier exaltation of Dolon (224–63), who after all required the help of Apollo and Hermes to succeed (cf. Klyve on 342–87 [pp. 229–31]). In the course of the ode both the Trojan hopes and the audience’s expectation of Rhesus reach their peak, although for the latter sinister undercurrents again come in.

The dazzling Thracian will no more ‘return home’ (367–9; cf. 450)345 than the hapless Dolon (235–7), and instead of witnessing symposia again, Troy will suffer the fate envisaged for the Greeks (357–9, 375b–7nn.).

If we had the choral response to Memnon’s arrival in A. Memnon (cf. 380–7n.) or to that of Cycnus in S. Poimenes (264–341, 388–526nn.), we might find that our poet went out of his way to elevate Rhesus before his fall (certainly with the lavish titles he bestowed on him). Yet it is not hybris and divine  that will prove his doom. Rhesus is as potent as the chorus wish and he himself will maintain, and has to die because Athena will not let him have his way (Klyve on 342–87 [p. 231]).

that will prove his doom. Rhesus is as potent as the chorus wish and he himself will maintain, and has to die because Athena will not let him have his way (Klyve on 342–87 [p. 231]).

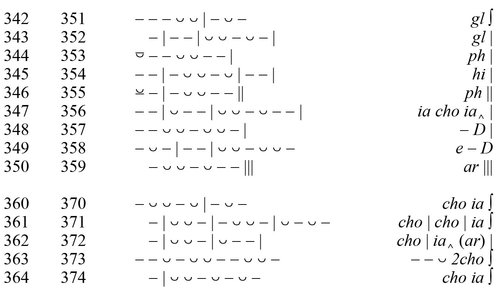

Metre

342–50 ~ 351–9. A sequence of aeolic, iambo-choriambic and dactylo-epitrite cola with an aristophanean clausula. The pattern again resembles the parodos (23–33 ~ 41–51) and in Euripides especially Tro. 1060–70 ~ 1071–81 (Ritchie 306–7). On the frequent combination of these metres see also West, GM 118–20.

360–9 ~ 370–9. Primarily iambo-choriambic and aeolic. With the colometry given here a ‘dove-tailed’ iambo-choriambic period (360–2/370–2n.) is followed by a variation on that scheme (363–5/373–5n.) and two aeolic elements with a iambo-choriambic close. But it is possible that the rhythm turns to ionic in the middle (363–5/373–5, 366–7/376–7nn.).

Notes

344/353 The strophe shows correption between  and ὅσον. The phenomenon does not often involve monophthongs (West, GM 12). In drama cf. particularly Ar. Vesp. 1065

and ὅσον. The phenomenon does not often involve monophthongs (West, GM 12). In drama cf. particularly Ar. Vesp. 1065  αἵδ᾽ – ‘highly unusual in trochaics’ (Parker, Songs, 247) because ‘the shortened syllable is practically always preceded or followed by a naturally short syllable’ (West, GM 11).

αἵδ᾽ – ‘highly unusual in trochaics’ (Parker, Songs, 247) because ‘the shortened syllable is practically always preceded or followed by a naturally short syllable’ (West, GM 11).

347/356 For choriambic trimeters in tragedy see 224–63 ‘Metre’ 242–3/253–4n. The first exponent of ia cho ia‸ is Anacr. fr. 384 PMG. Like other pendant cola, the verse need not be clausular (cf. Ag. 141, Ant. 806 ~ 823, Med. 432 ~ 439, Hel. 1452 ~ 1466).

350/359 The aristophanean, which is not elsewhere appended to dactylo-epitrite (Parker, Songs, 83), echoes the closing rhythm of 347 ~ 356 (above).

360–2/370–2 Various divisions are possible, not least because of the regular word-ends after the choriambs. The standard arrangement is cho ia cho | cho | ia ∫ cho | ia‸ |, but the double ‘dove-tailing’, by which the initial colon (cho ia) is first expanded (cho | cho | ia), then reduced (cho | ia‸), may be preferable also in view of the parallel evolution that seems to obtain in 363–5 ~ 373–5 (below).