411b–12. ‘For these (favours) you have spurned your great debt of gratitude, and when your friends are in trouble, you come to our help too late.’

Words and rhetoric resemble Admetus’ demand for parental recognition at Alc. 660–1 …

(less close Medea at Med. 488–90), while Achilles begins with the Achaeans’ lack of gratitude in Il. 9.316–17 …

(less close Medea at Med. 488–90), while Achilles begins with the Achaeans’ lack of gratitude in Il. 9.316–17 …

(+ 318–19). Cf. 388–453, 406–11a nn.

(+ 318–19). Cf. 388–453, 406–11a nn.

λακτίσας πολλὴν χάριν: literally ‘you have kicked …’. So also Ag. 381–4

, PV 651–2

, PV 651–2

and Eum. 110

and Eum. 110  (with Sommerstein).

(with Sommerstein).

ὕστερος βοηδρομεῖς: 333n. Personal ὕστερος (OQgV) is required in the sense ‘later, too late’ (LSJ s.v. A II 2, 3), whence also 443 (n.)  ὕστερος μὲν ἦλθον … (corr. Cobet) and 453 …

ὕστερος μὲν ἦλθον … (corr. Cobet) and 453 …  (-ος V: -ον

(-ος V: -ον  ). The (adverbial) accusative here (VLgE) was easy after 333 …

). The (adverbial) accusative here (VLgE) was easy after 333 …  . V even continues with the infinitive.

. V even continues with the infinitive.

413–18. Hector’s complaint that the Trojans and their other allies have endured the hardships of war, while Rhesus led an easy life (and now has come to receive a share in the spoils: 325–6) has a precedent in Achilles’ accusation of Agamemnon as only ever having profited from his exploits (Il. 9.321–43). Cf. D. Sansone, BMCR 2013.03.13 and 388–453n.

413–14a. δ᾽᾽: strongly adversative (GP 166–7), contrasting 404–5.

ἡμῖν ἐγγενεῖς πεϕυκότες: Cf. OC 1167–8

, and see 404–5n. Many editors before Murray read Valckenaer’s ἐν γένει (Diatribe, 105 n. 7), which, however, seems to be restricted to family ties: Cho. 287, OT 1016, 1430, Alc. 904, Dem. 23.72, 57.28, [Dem.] 47.70, 60.7. Unfortunately, the text of Dicaeog. TrGF 52 F 1b.3

, and see 404–5n. Many editors before Murray read Valckenaer’s ἐν γένει (Diatribe, 105 n. 7), which, however, seems to be restricted to family ties: Cho. 287, OT 1016, 1430, Alc. 904, Dem. 23.72, 57.28, [Dem.] 47.70, 60.7. Unfortunately, the text of Dicaeog. TrGF 52 F 1b.3  is insecure.

is insecure.

πάλαι: 321b–2a n.

414b–15. ἐν χωστοῖς τάϕοις: ‘… in grave mounds’, such as were heaped over the pyre or, in the case of major individual heroes, the urn or coffin containing their bones: Il. 6.418–19, 7.328–37, 23.234–57, 24.788–801 (Hector), Od. 11.74–8, 12.11–15, 24.71–84 (Achilles and Patroclus), Rh. 959 (959–60n.) καὶ νῦν  . Cf. M. Andronikos, Arch. Hom. W 32–4, 107–21.

. Cf. M. Andronikos, Arch. Hom. W 32–4, 107–21.

(‘heaped up’) occurs only here in classical Greek (later e.g. Lyc. 698, 1064, Plb. 4.61.7, Strabo 11.2.7). But it may have been current to judge by the compounds in Cho. 351–2

(‘heaped up’) occurs only here in classical Greek (later e.g. Lyc. 698, 1064, Plb. 4.61.7, Strabo 11.2.7). But it may have been current to judge by the compounds in Cho. 351–2  and Ant. 848–9 πρὸς ἕργμα (v.l. ἕρμα)

and Ant. 848–9 πρὸς ἕργμα (v.l. ἕρμα)  ἔρ- / χομαι

ἔρ- / χομαι  ποταινίου. The verb

ποταινίου. The verb  is also regular in tragedy.

is also regular in tragedy.

πίστις οὐ σμικρὰ πόλει (‘no small pledge of loyalty to our city’) echoes the second half of Hipp. 1037 ὅρκους παρασχών,  σμικράν, θεῶν, which comes shortly after 1031 (= 1075, 1191) … εἰ

κακὸς

σμικράν, θεῶν, which comes shortly after 1031 (= 1075, 1191) … εἰ

κακὸς  (cf. 394b–5n.). For the nominative in apposition to the sentence, expressing a judgement, cf. e.g. Tro. 489–90 τὸ

(cf. 394b–5n.). For the nominative in apposition to the sentence, expressing a judgement, cf. e.g. Tro. 489–90 τὸ

κακῶν, /

κακῶν, /  Ἑλλάδ᾽ εἰσαϕίξομαι (KG I 284, SD 617). This is preferable to Bothe’s

Ἑλλάδ᾽ εἰσαϕίξομαι (KG I 284, SD 617). This is preferable to Bothe’s  οὐ

οὐ

(5 [1803], 293), which, following nominatives, would signify a result (257b–60n.).

(5 [1803], 293), which, following nominatives, would signify a result (257b–60n.).

416–18a. ‘… whereas others stand fast in armour and by their horse-drawn chariots, patiently enduring the wind’s cold blasts and the sun-god’s thirsty flame …’

The pairing of winter cold and summer heat resembles the account of the Argive Herald at Ag. 563–6  δ᾽

δ᾽  οἰωνοκτόνον, /

οἰωνοκτόνον, /  παρεῖχ᾽ ἄϕερτον

παρεῖχ᾽ ἄϕερτον  , / ἢ θάλπος, εὖτε πόντος ἐν μεσημβριναῖς / κοίταις ἀκύμων

, / ἢ θάλπος, εὖτε πόντος ἐν μεσημβριναῖς / κοίταις ἀκύμων  (Paley on 417). But one also recalls Odysseus’ account of a freezing night before Troy at Od. 14.471–502 (especially 475–7). For the language here cf. E. fr. 78a (below).

(Paley on 417). But one also recalls Odysseus’ account of a freezing night before Troy at Od. 14.471–502 (especially 475–7). For the language here cf. E. fr. 78a (below).

ἱππείοις ὄχοις: 301b–2n. The phrase may go back to Il. 5.794

ἱππείοις ὄχοις: 301b–2n. The phrase may go back to Il. 5.794  δὲ τόν

δὲ τόν  ἄνακτα

ἄνακτα  καὶ ὄχεσϕιν, just as A. Suppl. 183

καὶ ὄχεσϕιν, just as A. Suppl. 183  ἵπποις καμπύλοις τ᾽ ὀχήμασιν (with FJW) has more closely been adapted from Il. 4.297 (= 5.219, 9.384, 12.119, 18.237)

ἵπποις καμπύλοις τ᾽ ὀχήμασιν (with FJW) has more closely been adapted from Il. 4.297 (= 5.219, 9.384, 12.119, 18.237)  καὶ ὄχεσϕιν. Similarly Il. 5.107 πρόσθ᾽ ἵπποιιν

καὶ ὄχεσϕιν. Similarly Il. 5.107 πρόσθ᾽ ἵπποιιν  ὄχεσϕιν. Mycenean Greek has feminine i-qi-ja meaning ‘chariot’ (LSJ Suppl. [1996] s.v.

ὄχεσϕιν. Mycenean Greek has feminine i-qi-ja meaning ‘chariot’ (LSJ Suppl. [1996] s.v.  IV).

IV).

ψυχρὰν ἄησιν: The noun otherwise appears only at E. fr. 78a (Alcmeon)  ἄπεπλον, ὦ δύστηνε,

ἄπεπλον, ὦ δύστηνε,  ἔχεις σέθεν. / – ἐν

ἔχεις σέθεν. / – ἐν  καὶ θέρος διέρχομαι (where Phot. α 448 Theodoridis glosses ἄησιν with χειμῶνα) and Phaeth. 255 Diggle = E. fr. 781.46

καὶ θέρος διέρχομαι (where Phot. α 448 Theodoridis glosses ἄησιν with χειμῶνα) and Phaeth. 255 Diggle = E. fr. 781.46  ἄησις. More commonly

ἄησις. More commonly  in Aeschylus (Ag. 1418, Eum. 905), Sophocles (Ai. 674) and later poetry (e.g. Call. Aet. fr. 75.36 Harder, Nonn. D. 2.529

in Aeschylus (Ag. 1418, Eum. 905), Sophocles (Ai. 674) and later poetry (e.g. Call. Aet. fr. 75.36 Harder, Nonn. D. 2.529  ).

).

δίψιόν τε πῦρ θεοῦ: ‘thirsty’ because the blazing summer sun drains all moisture from the land. Cf. Opp. Hal. 3.47–8  δὲ

δὲ  … δίψιον ὥρην / Σειρίου (unless this generally means ‘parched’), Nonn. D. 1.237 δίψιος … κύων (i.e. Sirius), 12.287. Conversely, dry ground has traditionally been called (πολυ)δίψιος: e.g. Il. 4.171 πολυδίψιον Ἄργος, Alc. 560, Ag. 495

… δίψιον ὥρην / Σειρίου (unless this generally means ‘parched’), Nonn. D. 1.237 δίψιος … κύων (i.e. Sirius), 12.287. Conversely, dry ground has traditionally been called (πολυ)δίψιος: e.g. Il. 4.171 πολυδίψιον Ἄργος, Alc. 560, Ag. 495  κόνις, Ant. 246–7 (with Griffith on 245–7), 429, Call. Aet. fr. 137c.10 Harder

κόνις, Ant. 246–7 (with Griffith on 245–7), 429, Call. Aet. fr. 137c.10 Harder  δ[ί]ψιον ἄστυ γε . […].

δ[ί]ψιον ἄστυ γε . […].

For θεός = ‘the sun-god’ see 330–1n. ( θεοῦ).

θεοῦ).

418b–19. ‘… not (reclining) on soft bedding, like you, and toasting one another in many deep draughts.’

Heavy drinking (of beer and undiluted wine) was a vice traditionally ascribed to northern barbarians: Archil. fr. 42 IEG (Thracians and Scythians), Anacr. fr. 356 (b) PMG, Ar. Ach. 141, Hdt. 6.84, Pl. Leg. 637d2–e7 (who observes that it does not diminish their martial prowess), Call. Aet. fr. 178.11–12 Harder, Hor. Carm. 1.36.13–14 neu multi Damalis meri / Bassum Threicia vincat amystide. Cf. Hall, Inventing the Barbarian, 18, 133–4.

The ‘bedding’ here also implies a charge of luxuriousness, which Rhesus includes in his defence at 438–9 (n.).

ἄμυστιν is an internal accusative with

ἄμυστιν is an internal accusative with  (below), in which

(below), in which  marks a frequently repeated action (LSJ s.v. A II 2; cf. 438–9n.).

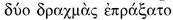

marks a frequently repeated action (LSJ s.v. A II 2; cf. 438–9n.).  – from ἀμυστί (< α privative + μύω), ‘without closing one’s mouth’ (Schwyzer 623 with n. 10) – denotes (1) a long draught and (2) a cup that lends itself to being drained at one go: Ath. Epit. XI 783d (III 22.15–19 Kaibel), ΣV Rh. 419 (II 337.6–10 Schwartz = 99 a1 Merro) and, for further references, Kassel–Austin on Cratin. fr. 322 PCG. Both meanings have been advocated here.367 But the first better suits the grammatical construction, and the passage from a play Auge, quoted by ΣV Rh. 419 (above) in support of ‘cup’, actually favours a series of deep draughts: σὺν τῷ

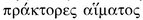

– from ἀμυστί (< α privative + μύω), ‘without closing one’s mouth’ (Schwyzer 623 with n. 10) – denotes (1) a long draught and (2) a cup that lends itself to being drained at one go: Ath. Epit. XI 783d (III 22.15–19 Kaibel), ΣV Rh. 419 (II 337.6–10 Schwartz = 99 a1 Merro) and, for further references, Kassel–Austin on Cratin. fr. 322 PCG. Both meanings have been advocated here.367 But the first better suits the grammatical construction, and the passage from a play Auge, quoted by ΣV Rh. 419 (above) in support of ‘cup’, actually favours a series of deep draughts: σὺν τῷ  καὶ πυκνὰς

καὶ πυκνὰς  (~ Cyc. 416–18 ὁ δ᾽ … / ἐδέξατ᾽ ἔσπασέν <τ᾽> ἄμυστιν

(~ Cyc. 416–18 ὁ δ᾽ … / ἐδέξατ᾽ ἔσπασέν <τ᾽> ἄμυστιν  /

/  ).368 Likewise at Ar. Ach. 1229 καὶ πρός γ᾽ ἄκρατον ἐγχέας ἄμυστιν ἐξέλαψα predicative ‘in one draught, without taking breath’ is preferable to a separate object ‘cup’ (Olson).

).368 Likewise at Ar. Ach. 1229 καὶ πρός γ᾽ ἄκρατον ἐγχέας ἄμυστιν ἐξέλαψα predicative ‘in one draught, without taking breath’ is preferable to a separate object ‘cup’ (Olson).

δεξιούμενοι: literally ‘greeting (one another) with the right hand’ (LSJ s.v. I with Suppl. [1996]). Of toasting also Men. Dysc. 948 ἐδεξιοῦτ᾽

I with Suppl. [1996]). Of toasting also Men. Dysc. 948 ἐδεξιοῦτ᾽  κύκλῳ. The symposiastic order was from left to right (362b–5a n.).

κύκλῳ. The symposiastic order was from left to right (362b–5a n.).

420–1. Like Polynices at Phoen. 494–6 ταῦτ᾽ αὔθ᾽ ἕκαστα, μῆτερ,

ἔνδιχ᾽,

ἔνδιχ᾽,  , Hector resumes the introductory theme of his speech (388–453, 394b–5nn.). Mastronarde (on Phoen. 494–6) observes

the intricate verbal ring composition between Phoen. 469–72 and 494–6, which is lacking here.

, Hector resumes the introductory theme of his speech (388–453, 394b–5nn.). Mastronarde (on Phoen. 494–6) observes

the intricate verbal ring composition between Phoen. 469–72 and 494–6, which is lacking here.

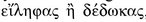

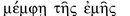

… / … μέμϕομαί σοι: ‘This I blame you for’, as in Ar. Nub. 525–6 ταῦτ᾽ οὖν ὑμῖν μέμϕομαι / τοῖς σοϕοῖς (LSJ s.v. μέμϕομαι 2). The internal accusative pronoun (as always with

… / … μέμϕομαί σοι: ‘This I blame you for’, as in Ar. Nub. 525–6 ταῦτ᾽ οὖν ὑμῖν μέμϕομαι / τοῖς σοϕοῖς (LSJ s.v. μέμϕομαι 2). The internal accusative pronoun (as always with  τινί τι) here doubles as a ‘proper’ accusative object to

τινί τι) here doubles as a ‘proper’ accusative object to  (cf. KG II 561–3, SD 708–9).

(cf. KG II 561–3, SD 708–9).

ὡς ἄν: 72–3n.

καὶ λέγω κατ᾽᾽ ὄμμα σόν: 370–2a n. In particular cf. E. El. 910 (Electra to the murdered Aegisthus) θρυλοῦσ᾽ ἅ γ᾽

and Ar. Ran. 626 αὐτοῦ μὲν οὖν, ἵνα σοι κατ᾽ ὀϕθαλμοὺς λέγῃ.

and Ar. Ran. 626 αὐτοῦ μὲν οὖν, ἵνα σοι κατ᾽ ὀϕθαλμοὺς λέγῃ.

422–3. ‘I am like this myself; I cleave a straight path in my speech, and I am not a duplicitous man.’

While Rhesus almost literally repeats Hector’s declaration of sincerity in 394–5, Eteocles recalls his brother only vaguely, and with no express acknowledgement, at Phoen. 503  γὰρ οὐδέν, μῆτερ,

γὰρ οὐδέν, μῆτερ,  ἐρῶ (388–453, 394b–5, 420–1nn.). Yet in both cases we have a captatio benevolentiae for the defence: Rhesus will speak the truth, and Eteocles must be excused if he is too blunt (cf. Mastronarde on Phoen. 503).

ἐρῶ (388–453, 394b–5, 420–1nn.). Yet in both cases we have a captatio benevolentiae for the defence: Rhesus will speak the truth, and Eteocles must be excused if he is too blunt (cf. Mastronarde on Phoen. 503).

εὐθεῖαν  κέλευθον: Two metaphors converge in this phrase. The ‘path of words’ was common in poetry and prose from Homer on (cf. West, IEPM 43–4)369 and so was the association of ‘straightness’ with justice and, more generally, honesty (LSJ s.vv. εὐθύς A 2, ἰθύς (A) I 2, Liapis on 422–3; especially Hipp. 491–2

κέλευθον: Two metaphors converge in this phrase. The ‘path of words’ was common in poetry and prose from Homer on (cf. West, IEPM 43–4)369 and so was the association of ‘straightness’ with justice and, more generally, honesty (LSJ s.vv. εὐθύς A 2, ἰθύς (A) I 2, Liapis on 422–3; especially Hipp. 491–2  τάχος διιστέον,

τάχος διιστέον,  εὐθὺν

εὐθὺν  λόγον). Verbal inspiration may have come from E. fr. 124.2–5 (Andromeda) ~ Ar. Thesm. 1099–1101

λόγον). Verbal inspiration may have come from E. fr. 124.2–5 (Andromeda) ~ Ar. Thesm. 1099–1101

,370 with a similar expression already used figuratively at A. Suppl. 806–7 ἀμϕυγᾶς τίν᾽

,370 with a similar expression already used figuratively at A. Suppl. 806–7 ἀμϕυγᾶς τίν᾽  ; (for the text see FJW on 806). The origin of this idiom lay in ‘cutting a road’ (LSJ

; (for the text see FJW on 806). The origin of this idiom lay in ‘cutting a road’ (LSJ  (A) VI 2 a, J. Chadwick, Lexicographica Graeca …, Oxford 1996, 276–7: Thuc. 2.100.2 ὁδοὺς εὐθείας ἔτεμε) rather than ploughing, as could be the case with places like Od. 3.174–5

(A) VI 2 a, J. Chadwick, Lexicographica Graeca …, Oxford 1996, 276–7: Thuc. 2.100.2 ὁδοὺς εὐθείας ἔτεμε) rather than ploughing, as could be the case with places like Od. 3.174–5  … / τέμνειν, 13.88, h.Cer. 383

… / τέμνειν, 13.88, h.Cer. 383

(Mastronarde on Phoen. 1 [p. 142], Dunbar on Ar. Av. 1398–1400, J. Chadwick, BICS 39 [1994], 7).

(Mastronarde on Phoen. 1 [p. 142], Dunbar on Ar. Av. 1398–1400, J. Chadwick, BICS 39 [1994], 7).

Despite E. fr. 124.3 (above), Nauck’s  (less likely τέμνειν) for the MSS’

(less likely τέμνειν) for the MSS’  (Euripideische Studien II, 173–4) seems inescapable here, since explanations after

(Euripideische Studien II, 173–4) seems inescapable here, since explanations after  or τοιόσδε normally follow in an asyndetic main clause (infinitive at IA 502–3). To his list of examples (Cyc. 524 τοιόσδ᾽ ὁ δαίμων· οὐδένα βλάπτει βροτῶν, Or. 895–6 [895–7 del. Dindorf], E. fr. 196.1–3) Liapis added Andr. 173–6, E. Suppl. 881–7 and E. fr. 322.1–3 (‘Notes’, 71–2), while no satisfactory parallel for the participle exists (Ag. 312–13 τοιοίδε τοί μοι λαμπαδηϕόρων νόμοι, /

or τοιόσδε normally follow in an asyndetic main clause (infinitive at IA 502–3). To his list of examples (Cyc. 524 τοιόσδ᾽ ὁ δαίμων· οὐδένα βλάπτει βροτῶν, Or. 895–6 [895–7 del. Dindorf], E. fr. 196.1–3) Liapis added Andr. 173–6, E. Suppl. 881–7 and E. fr. 322.1–3 (‘Notes’, 71–2), while no satisfactory parallel for the participle exists (Ag. 312–13 τοιοίδε τοί μοι λαμπαδηϕόρων νόμοι, /  διαδοχαῖς

διαδοχαῖς  is a distributive apposition to the sentence [Fraenkel on 313, KG II 107, SD 403–4]). The corruption was easy by assimilation to the preceding εὐθείαν λόγων.

is a distributive apposition to the sentence [Fraenkel on 313, KG II 107, SD 403–4]). The corruption was easy by assimilation to the preceding εὐθείαν λόγων.

κοὐ διπλοῦς  ἀνήρ: 394b–5n.

ἀνήρ: 394b–5n.

424–5. ‘I was more vexed, more distressed by sorrow in my heart, than you at being absent from this land.’

ἐγὼ δέ: The particle here ‘marks the transition from the introduction … to the opening of the speech proper’ (GP 170–1). So especially after  (e.g. Ant. 1196, Alc. 681, Phoen. 473).

(e.g. Ant. 1196, Alc. 681, Phoen. 473).

μεῖζον: thus rightly ΔQ. The neuter plural (L) is not used as an adverb.

τῆσδ᾽ ἀπὼν χθονός goes with both  and, as a phrasal verb of feeling,

and, as a phrasal verb of feeling,  … ἐτειρόμην (KG II 53–4, SD 392–3).

… ἐτειρόμην (KG II 53–4, SD 392–3).

λύπῃ πρὸς ἧπαρ … ἐτειρόμην recalls Il. 22.242  ἐμὸς ἔνδοθι

ἐμὸς ἔνδοθι  πένθεϊ

πένθεϊ  (~ Od. 2.70–1), Od. 1.340–2

(~ Od. 2.70–1), Od. 1.340–2  δ᾽

δ᾽  / λυγρῆς, ἥ

/ λυγρῆς, ἥ  μοι αἰὲν ἐνὶ

μοι αἰὲν ἐνὶ  / τείρει (cf. 750–1a, 799nn.) and, in the juxtaposition of

/ τείρει (cf. 750–1a, 799nn.) and, in the juxtaposition of  and ἧπαρ, Ag. 791 δῆγμα δὲ λύπης οὐδὲν ἐϕ᾽ ἧπαρ προσικνεῖται. By the early fifth century BC the liver had come to be regarded as the organ affected by deep emotions: also Ag. 432

and ἧπαρ, Ag. 791 δῆγμα δὲ λύπης οὐδὲν ἐϕ᾽ ἧπαρ προσικνεῖται. By the early fifth century BC the liver had come to be regarded as the organ affected by deep emotions: also Ag. 432  πρὸς ἧπαρ, Cho. 271–2, Eum. 135, Ai. 938

πρὸς ἧπαρ, Cho. 271–2, Eum. 135, Ai. 938  ἧπαρ, οἶδα, γενναία

ἧπαρ, οἶδα, γενναία  (with Kamerbeek, Finglass), Hipp. 1070 (with Barrett on 1070–1), E. Suppl. 599

(with Kamerbeek, Finglass), Hipp. 1070 (with Barrett on 1070–1), E. Suppl. 599  .371

.371

There is no need to suspect  ἧπαρ here (Nauck, Euripideische Studien II, 174) or to take it attributively with

ἧπαρ here (Nauck, Euripideische Studien II, 174) or to take it attributively with  (cf. Feickert on 425). Previous motion ‘towards’ the liver can easily be deduced from

(cf. Feickert on 425). Previous motion ‘towards’ the liver can easily be deduced from  (LSJ s.v.

(LSJ s.v.  C I 2 a, KG I 540–1, 543–4, SD 433–4 on the ‘pregnant’ use of prepositions).

C I 2 a, KG I 540–1, 543–4, SD 433–4 on the ‘pregnant’ use of prepositions).

δυσϕορῶν: a forceful verb (W. S. Barrett, in R. Carden [ed.], The Papyrus Fragments of Sophocles, Berlin – New York 1974, 217–18, Hutchinson on Sept. 780 ‘… may denote being swept along by sinister or painful feelings … by madness, grief, or rage’), which here, however, looks like a verse filler.

426–42. As in the case of Rhesus’ Thracian battles (406–11a n.), there is no evidence that this Scythian war was anything but our poet’s invention – which Parthenius took over in Erot. Path. 36.1  δὲ καὶ Ῥῆσον,

δὲ καὶ Ῥῆσον,  ,

,  ἰέναι προσαγόμενόν τε καὶ δασμὸν ἐπιτιθέντα (434–5n., Introduction, 17, 44–5). Similarly, Menelaus excuses himself with the necessity to defend Sparta in Andr. 732–8, and Polymestor in Hec. 962–7 declares that, when Hecuba came to the Greek camp, he had been away in inland Thrace (Burnett, ‘Smiles’, 30 with n. 52 [p. 181]).372

ἰέναι προσαγόμενόν τε καὶ δασμὸν ἐπιτιθέντα (434–5n., Introduction, 17, 44–5). Similarly, Menelaus excuses himself with the necessity to defend Sparta in Andr. 732–8, and Polymestor in Hec. 962–7 declares that, when Hecuba came to the Greek camp, he had been away in inland Thrace (Burnett, ‘Smiles’, 30 with n. 52 [p. 181]).372

The Scythians lived beyond the Danube, whose lower stretch our poet appears to regard as the north-eastern border of Rhesus’ realm (as it was for the historical kingdom of the Odrysae). Thus if they attacked him by the Bosporus (cf. 436–7n.), ‘they were alarmingly deep into his territory’ (Liapis on 428–9). Rhesus’ apparent detour to the Black Sea also fits his arrival via Mt. Ida to the south-east of Troy (284–6n.).

426–8a. ‘But a country bordering on mine, the Scythian people, started a war on me as I was about to make the journey across to Ilium.’

ἀγχιτέρμων: ‘near the border, neighbouring’ (LSJ s.v.). Before Rhesus the adjective is attested only at S. fr. 384

Blaydes). Later Theodect. TrGF 72 F 17.1, Lyc. 729, 1130 and, in prose, Xen. Hier. 10.7

Blaydes). Later Theodect. TrGF 72 F 17.1, Lyc. 729, 1130 and, in prose, Xen. Hier. 10.7  . Pollux (6.113) calls it

. Pollux (6.113) calls it  (‘dithyrambic in style, high-flown’).

(‘dithyrambic in style, high-flown’).

Σκύθης λεώς: The apposition of a people’s name to the country they inhabit  γαῖά μοι) seems to be unparalleled.

γαῖά μοι) seems to be unparalleled.

: here simply ‘journey …’ (ΣV Rh. 427 [II 337.11–13 Schwartz = 100 Merro]), as in IT 1111–12 ζαχρύσου

: here simply ‘journey …’ (ΣV Rh. 427 [II 337.11–13 Schwartz = 100 Merro]), as in IT 1111–12 ζαχρύσου

, IA 965–6

, IA 965–6  , εἰ

, εἰ  /

/  , 1261. Also

, 1261. Also  at Hel. 428, 474, 891, Ar. Ach. 28–9, Pherecr. fr. 87.2 PCG.

at Hel. 428, 474, 891, Ar. Ach. 28–9, Pherecr. fr. 87.2 PCG.

ξυνῆψε πόλεμον: Cf. Hdt. 1.18.2 ὁ τὸν πόλεμον … συνάψας, Thuc. 6.13.2 and, with the subject designating an external cause, Hel. 53–5

/…

/…  /

/

(LSJ s.v.

(LSJ s.v.  A II 1 b).

A II 1 b).

Euripides was extremely fond of  in nearly all its applications. Though used by the other dramatists and once by Pindar (Pyth. 4.247), the verb does not seem to have been part of the poetic tradition.

in nearly all its applications. Though used by the other dramatists and once by Pindar (Pyth. 4.247), the verb does not seem to have been part of the poetic tradition.

428b–9. Ἀξένου … / πόντου πρὸς ἀκτάς: Diggle and Kovacs rightly read  (better Ἀξένου) for the MSS’ εὐξένου with Markland (Euripidis dramata Iphigenia in Aulide et Iphigenia in Tauris, London 11771, 242–3) – as also in HF 410, IT 124–5, 395, 1388–9 and Andr. 1262 (Cobet). Even if one disputes the need for consistency in any given author or genre,

(better Ἀξένου) for the MSS’ εὐξένου with Markland (Euripidis dramata Iphigenia in Aulide et Iphigenia in Tauris, London 11771, 242–3) – as also in HF 410, IT 124–5, 395, 1388–9 and Andr. 1262 (Cobet). Even if one disputes the need for consistency in any given author or genre,  is the more poignant in all these places373 and would easily have been replaced by the later ‘default’ form. Cf. Pi. Pyth. 4.203–4

is the more poignant in all these places373 and would easily have been replaced by the later ‘default’ form. Cf. Pi. Pyth. 4.203–4  … /

… /  (

( - codd. pler.: εὐξ- C), and see n. 159, Bond on HF 410.

- codd. pler.: εὐξ- C), and see n. 159, Bond on HF 410.

Since Vasmer (1921)374 the original Greek Ἄξε(ι)νος for the Black Sea, first attested in Pi. Pyth. 4.203 (above), has been linked with common Iranian *axšaina-, ‘dark-coloured’, which is represented by Avestan axšaēna-, Old Persian axšaina- (marking the turquoise) and various terms for ‘blue’, ‘greenish’ or ‘dark gray’ in related languages (R. Schmitt, in H. M. Ölberg et al. [eds.], Sprachwissenschaftliche Forschungen. Festschrift für Johann Knobloch … , Innsbruck 1985, 409–12, who notes, however, the lack of first-hand evidence that the word was used of the Black Sea).375 False etymology as ‘inhospitable’ then led to the euphemistic change into Εὔξεινος, probably indeed by Ionian settlers (Strabo 7.3.6), as the vocalism suggests (W. S. Allen, CQ 41 [1947], 88; cf. Bond on HF 410). Hecataeus may have been the earliest author to use that name (FGrHist 1 FF 18a, b).

Θρῇκα πορθμεύσων στρατόν: so L and most editors. But the final-consecutive infinitive  (Q, Aldina) is attractive and has been adopted by Paley and Feickert (on 429). To the latter’s argument of lectio difficilior and the fact that an analogous pair of variants can be found at Med. 1303

(Q, Aldina) is attractive and has been adopted by Paley and Feickert (on 429). To the latter’s argument of lectio difficilior and the fact that an analogous pair of variants can be found at Med. 1303  (codd. pler.: ἐκσῶσαι

HOP2: [Π5])376 one may add that

(codd. pler.: ἐκσῶσαι

HOP2: [Π5])376 one may add that  would account even better for

would account even better for  in Δ (on its genesis from the future participle see 452–3n. with n. 168). The infinitive survives in IT 937–8 (Ορ.)

in Δ (on its genesis from the future participle see 452–3n. with n. 168). The infinitive survives in IT 937–8 (Ορ.)  κελευσθεὶς

κελευσθεὶς  ἀϕικόμην. / (Ιϕ.)

ἀϕικόμην. / (Ιϕ.)  ; (Elmsley: δράσειν L:

; (Elmsley: δράσειν L:  idem Elmsley) and Phaeth. 97–8 Diggle = E. fr. 773.53–4

idem Elmsley) and Phaeth. 97–8 Diggle = E. fr. 773.53–4  προσέβαν ὑμέναιον ἀεῖσαι /

προσέβαν ὑμέναιον ἀεῖσαι /  (cf. KG II 16–17, SD 362, Diggle, Euripidea, 324).

(cf. KG II 16–17, SD 362, Diggle, Euripidea, 324).

430–1. ‘There the spear drew thick streams of Scythian blood, (to run) into the ground, and Thracian gore mixed up with it.’

This grim depiction of the battle was clearly influenced by the Ghost of Darius’ prophecy of Plataea at Pers. 816–17

/

/  . But our poet supplanted the unique and not universally transmitted

. But our poet supplanted the unique and not universally transmitted  (v.l. αἱματοσταγής – but see Garvie on 816–17) with the more familiar and metrically easier αἱματηρός, which qualifies

(v.l. αἱματοσταγής – but see Garvie on 816–17) with the more familiar and metrically easier αἱματηρός, which qualifies  in the otherwise unrelated Alc. 850–1 (Heracles of Death drinking sacrificial blood) ἢν δ᾽ οὖν ἁμάρτω τῆσδ᾽ ἄγρας καὶ μὴ μόλῃ / πρὸς αἱματηρὸν πελανόν. The result of this ‘non-slavish’ form of borrowing (Fraenkel, Rev. 232; cf. Introduction, 35–6) still sounds disproportionate for Rhesus’ peripheral war (388–453n.).

in the otherwise unrelated Alc. 850–1 (Heracles of Death drinking sacrificial blood) ἢν δ᾽ οὖν ἁμάρτω τῆσδ᾽ ἄγρας καὶ μὴ μόλῃ / πρὸς αἱματηρὸν πελανόν. The result of this ‘non-slavish’ form of borrowing (Fraenkel, Rev. 232; cf. Introduction, 35–6) still sounds disproportionate for Rhesus’ peripheral war (388–453n.).

ἔνθ᾽: Like its temporal counterpart in 930, this marks a new development in the tale and so is demonstrative rather than relative. The usage is rare outside epic (LSJ s.v. ἔνθα I 1, 2). Certainly in drama only A. Suppl. 30–6  … ξὺν ὄχῳ

… ξὺν ὄχῳ  /

/  ·

·  , / … ὄλοιντο, although Andr. 21 and Phoen. 657 (at the beginning of a choral antistrophe) can hardly be different. See FJW on A. Suppl. 33.

, / … ὄλοιντο, although Andr. 21 and Phoen. 657 (at the beginning of a choral antistrophe) can hardly be different. See FJW on A. Suppl. 33.

αἱματηρὸς πελανός: Apart from Alc. 850–1 (above), cf. IT 300  αἱματηρὸν πέλαγος ἐξανθεῖν ἁλός, with predicative αἱματηρόν and the near-homophone

αἱματηρὸν πέλαγος ἐξανθεῖν ἁλός, with predicative αἱματηρόν and the near-homophone  at the same metrical position. πελανός can be ‘any thick liquid substance’ (LSJ s.v. I) and is applied to blood also in Eum. 265

at the same metrical position. πελανός can be ‘any thick liquid substance’ (LSJ s.v. I) and is applied to blood also in Eum. 265  ...

...  (where, as in Alcestis, the ritual connotation is important). It is a favourite word of Aeschylus and Euripides (Fraenkel on Ag. 96, Parker on Alc. 851).

(where, as in Alcestis, the ritual connotation is important). It is a favourite word of Aeschylus and Euripides (Fraenkel on Ag. 96, Parker on Alc. 851).

Θρῄξ τε συμμιγὴς ϕόνος: O alone has  here. On the basis of

here. On the basis of  ϕόνῳ, Matthiae (VIII [1824], 23, on 428) wrote Θρῃκὶ συμμιγὴς ϕόνῳ. But

ϕόνῳ, Matthiae (VIII [1824], 23, on 428) wrote Θρῃκὶ συμμιγὴς ϕόνῳ. But  τε is much less likely to have arisen by anticipation

(following

τε is much less likely to have arisen by anticipation

(following  especially) than

especially) than  as a dative falsely supplied with

as a dative falsely supplied with  (cf. Sept. 739–40

(cf. Sept. 739–40  πόνοι

πόνοι  / νέοι παλαιοῖσι

/ νέοι παλαιοῖσι  κακοῖς, S. fr. 398.3, Antiph. fr. 55.7–8 PCG).

κακοῖς, S. fr. 398.3, Antiph. fr. 55.7–8 PCG).

In classical Greek  is restricted ‘to poets and poetic prose’ (Dunbar on Ar. Av. 771–2).

is restricted ‘to poets and poetic prose’ (Dunbar on Ar. Av. 771–2).

432–3. τοι serves to emphasise the truth of what Rhesus has just explained. If translated at all, parenthetic ‘you (must) know’ would convey the point (GP 537–40).

πέδον / Τροίας: a ‘Euripidean’ juncture (Andr. 11, 58, Or. 522). Sophocles has Τροίας πεδία / -ίον five times in Philoctetes (920, 1297, 1332, 1376, 1435). Also Hec. 140 Τροίας πεδίων.

434–42. Nearly the whole long sentence hinges on  as the main verb: Rhesus negotiated all obstacles as quickly as possible and now ‘has come’.

as the main verb: Rhesus negotiated all obstacles as quickly as possible and now ‘has come’.

434–5. ‘But when I had sacked them, having taken their children as hostages and set an annual tribute to bring to my home …’

τῶνδ᾽ resumes the object of ἔπερσα (i.e. the Scythians), which has to be supplied from the context. For this ‘anaphoric’ use of  (rare in prose) cf. e.g. Sept. 424, PV 904, Ai. 28, Hec. 427 (KG I 646–7, SD 209).

(rare in prose) cf. e.g. Sept. 424, PV 904, Ai. 28, Hec. 427 (KG I 646–7, SD 209).

ὁμηρεύσας: transitive, ‘to take as a hostage’, only here (cf. 360–2a n.), though Aen. Tact. 10.23 has the middle in the sense ‘give hostages’. It is also our sole poetic attestation of the verb, save for Ba. 296–7 ὅτι θεᾷ θεός (Dionysus) /  ποθ᾽ ὡμήρευσε (with Dodds) and Antiph. fr. 115.2 PCG (cf. Fraenkel, Rev. 234). The noun ὅμηρος is found in Alc. 870, Or. 1189, Ba. 293, Ar. Ach. 327 and Lys. 244.

ποθ᾽ ὡμήρευσε (with Dodds) and Antiph. fr. 115.2 PCG (cf. Fraenkel, Rev. 234). The noun ὅμηρος is found in Alc. 870, Or. 1189, Ba. 293, Ar. Ach. 327 and Lys. 244.

The purpose of the hostages was to ensure that the Scythians accepted submission (ΣV Rh. 434 [II 338.20–1 Schwartz = 100 Merro]) and paid their annual tribute. Similarly e.g. Thuc. 1.108.3, 1.115.3, 3.90.4 and, in general, M. Amit, RFIC 98 (1970), 129–47, Olson on Ar. Ach. 326–7.

τάξας ἔτειον δασμὸν … ϕέρειν follows in asyndeton to mark the rapid sequence of events (Feickert on 435). Lenting’s τάξας <τ᾽> (Animadversiones, 74) would spoil that effect.

Unlike  for ‘tribute, payment’ (LSJ s.v. 1, 2), δασμός has a poetic heritage from epic and elegiac ‘division’ (< *δατ-σμος < δατέομαι: Il. 1.166, Hes. Th. 425, h.Cer. 86, ‘Thgn.’ 678) to ‘tribute’ in OT 36, OC 635 and S. fr. 730c.15. Of prose authors Xenophon alone made widespread use of the word. In particular see An. 5.5.10 διὸ

for ‘tribute, payment’ (LSJ s.v. 1, 2), δασμός has a poetic heritage from epic and elegiac ‘division’ (< *δατ-σμος < δατέομαι: Il. 1.166, Hes. Th. 425, h.Cer. 86, ‘Thgn.’ 678) to ‘tribute’ in OT 36, OC 635 and S. fr. 730c.15. Of prose authors Xenophon alone made widespread use of the word. In particular see An. 5.5.10 διὸ

οὗτοι τεταγμένον and Cyr. 8.6.8 δασμοὺς μέντοι

οὗτοι τεταγμένον and Cyr. 8.6.8 δασμοὺς μέντοι

καὶ τούτους.

καὶ τούτους.

The relative infrequency of  suggests that Parth. Erot. Path. 36.1 (quoted in 426–42n.) goes back to our passage instead of representing a separate tradition. ‘But Parthenius speaks in very unspecific

terms, and makes Rhesus sound like a second Achilles, winning over cities to his side before he joins the Greeks at Troy’ (Lightfoot, Parthenius, 555–6).

suggests that Parth. Erot. Path. 36.1 (quoted in 426–42n.) goes back to our passage instead of representing a separate tradition. ‘But Parthenius speaks in very unspecific

terms, and makes Rhesus sound like a second Achilles, winning over cities to his side before he joins the Greeks at Troy’ (Lightfoot, Parthenius, 555–6).

436–7. In addition to Xerxes’ return to Persia (388–453n.), we are reminded here of his fateful ‘yoking’ of the Hellespont at Pers. 65–72, 108–13, 721–4, 736–8 and 745–50 (cf. Hdt. 7.33–6, 8.117.1, 9.114.1). Darius I had the Bosporus bridged to bring his army across to Scythia (Hdt. 4.83–9).

ἥκω: 434–42n.

Πόντιον στόμα was a regular periphrasis for the Bosporus. Cf. e.g. Pers. 879 στόμωμα Πόντου, Pi. Pyth. 4.203 ἐπ᾽ Ἀξείνου στόμα, Hdt. 4.81.3 ἐπὶ  τοῦ Πόντου, 4.85.3, Thuc. 4.75.2, A. R. 1.2, 4.1002 (Gow on Theoc. 22.28).

τοῦ Πόντου, 4.85.3, Thuc. 4.75.2, A. R. 1.2, 4.1002 (Gow on Theoc. 22.28).

τὰ δ᾽ ἄλλα … γῆς … ὁρίσματα: ‘the other territories’, as in Hec. 16  μὲν οὖν

μὲν οὖν  ὄρθ᾽ ἔκειθ᾽ ὁρίσματα (Troy and the Troad) and Tro. 375

ὄρθ᾽ ἔκειθ᾽ ὁρίσματα (Troy and the Troad) and Tro. 375  ὅρι᾽ ἀποστερούμενοι. ‘Words meaning ‘boundaries’ … are commonly used with a gen[itive] of a country in contexts of leaving or entering … ; since in these contexts ὅροι χώρας differs little from χώρα, it was no long step to treating it as an equivalent of

ὅρι᾽ ἀποστερούμενοι. ‘Words meaning ‘boundaries’ … are commonly used with a gen[itive] of a country in contexts of leaving or entering … ; since in these contexts ὅροι χώρας differs little from χώρα, it was no long step to treating it as an equivalent of  in any context’ (Barrett on Hipp. 1158–9

in any context’ (Barrett on Hipp. 1158–9  Τροζηνίας). So also Hipp. 1459

Τροζηνίας). So also Hipp. 1459

Fitton:

Fitton:  vel

vel  codd.) and properly Andr. 968

codd.) and properly Andr. 968  πρὶν τὰ Τροίας

πρὶν τὰ Τροίας  ὁρίσματα.

ὁρίσματα.

438–9. ‘… no deep draughts on my part, as you loudly claim, nor resting on beds in all-golden palaces …’

The syntactic structure of Rhesus’ reply to 418–19 recalls Med. 555–7 (Jason to Medea) οὐχ, ᾗ  κνίζῃ, σὸν μὲν

κνίζῃ, σὸν μὲν  λέχος / … / οὐδ᾽ εἰς

λέχος / … / οὐδ᾽ εἰς  (Ritchie 244–5; cf. 388–453, 440–2nn.). But it presents a very harsh anacoluthon, in which the expected participle (δεξιούμενος from 419) is omitted and its object transferred to the parenthesis ὡς

(Ritchie 244–5; cf. 388–453, 440–2nn.). But it presents a very harsh anacoluthon, in which the expected participle (δεξιούμενος from 419) is omitted and its object transferred to the parenthesis ὡς  κομπεῖς. Attempts to posit a lacuna after 438 (Vater on 425) or otherwise to emend the text have failed,377 so that we are left with the assumption that ‘[t]he anacoluthon … is authorial’ (Liapis, ‘Notes’, 73).

κομπεῖς. Attempts to posit a lacuna after 438 (Vater on 425) or otherwise to emend the text have failed,377 so that we are left with the assumption that ‘[t]he anacoluthon … is authorial’ (Liapis, ‘Notes’, 73).

A closer parallel than Ba. 683–8  δὲ πᾶσαι

δὲ πᾶσαι

/ … 686 …

/ … 686 …  /

/

/ θηρᾶν καθ᾽

/ θηρᾶν καθ᾽  ἠρημωμένας (cited by Porter), where

the accusative and infinitive follows more easily on the verb of speaking (cf. Bruhn, Anhang, § 176, Jebb on Tr. 1238–9), is Theoc. 12.12–14

ἠρημωμένας (cited by Porter), where

the accusative and infinitive follows more easily on the verb of speaking (cf. Bruhn, Anhang, § 176, Jebb on Tr. 1238–9), is Theoc. 12.12–14  /

/  ,

,  (‘lover’),

(‘lover’),  χ᾽ Ὡμυκλαϊάζων, /

χ᾽ Ὡμυκλαϊάζων, /  ,

,  κεν ὁ

κεν ὁ  εἴποι,

εἴποι,  (‘beloved’). There the apposition has been ‘attracted’ into the second parenthesis to produce a formally identical result.

(‘beloved’). There the apposition has been ‘attracted’ into the second parenthesis to produce a formally identical result.

ὡς  κομπεῖς: For the exact phrase cf. Rh. 875–6 (n.)

κομπεῖς: For the exact phrase cf. Rh. 875–6 (n.)  ὁ

ὁ  οὐ γὰρ

οὐ γὰρ  σὲ

σὲ  / γλῶσσ᾽,

/ γλῶσσ᾽,  σὺ

σὺ  … and Or. 570–1 δράσας δ᾽

… and Or. 570–1 δράσας δ᾽  / δείν᾽,

/ δείν᾽,

κομπεῖς, τόνδ᾽ ἔπαυσα

κομπεῖς, τόνδ᾽ ἔπαυσα

.378 Porter (on 438) does well to distinguish our passages from the regular (metaphorical) sense of κομπέω, ‘to brag, boast’ (LSJ s.v. II). Applied to human speech, the original ‘din’ or ‘clash’ (LSJ s.v. I) just as easily covered a loud proclamation or complaint.

.378 Porter (on 438) does well to distinguish our passages from the regular (metaphorical) sense of κομπέω, ‘to brag, boast’ (LSJ s.v. II). Applied to human speech, the original ‘din’ or ‘clash’ (LSJ s.v. I) just as easily covered a loud proclamation or complaint.

The verb has a direct object also at PV 947 …

(LSJ s.v. II 2).

(LSJ s.v. II 2).

τὰς ἐμὰς ἀμύστιδας: 418b–19n. The plural was implied in 419  ἄμυστιν. With the possessive pronoun, however, it also reflects Hector’s contempt (cf. 866–7n.).

ἄμυστιν. With the possessive pronoun, however, it also reflects Hector’s contempt (cf. 866–7n.).

ἐν ζαχρύσοις δώμασιν: 370–2a n.  ζάχρυσον … πέλταν). Golden halls are a standard symbol of excessive (non-Greek) luxury: e.g. Pers. 3–4 καὶ

ζάχρυσον … πέλταν). Golden halls are a standard symbol of excessive (non-Greek) luxury: e.g. Pers. 3–4 καὶ

καὶ

καὶ  ἑδράνων ϕύλακες, 159

ἑδράνων ϕύλακες, 159  δόμους, Hel. 928 Φρυγῶν … πολυχρύσους δόμους (Hall, Inventing the Barbarian, 80–1, 127–8). In a wholly ‘barbarian’ context they are set against the austerity of the Trojan field (416–18a n.).

δόμους, Hel. 928 Φρυγῶν … πολυχρύσους δόμους (Hall, Inventing the Barbarian, 80–1, 127–8). In a wholly ‘barbarian’ context they are set against the austerity of the Trojan field (416–18a n.).

440–2. ‘No, I know what frozen blasts press heavily upon the Thracian sea and the Paeonians, having sleeplessly endured them in this cloak.’

‘Thrace was notorious for its snow and harsh winters’ (Olson on Ar. Ach. 138–40). 379 For Rhesus’ justification, which is added in the same way as that of Jason at Med. 559–65  … (388–453, 438–9nn.), our poet had again recourse to Persians – to produce a ‘mosaic passage’ similar to 430–1 (n.). The adjective

… (388–453, 438–9nn.), our poet had again recourse to Persians – to produce a ‘mosaic passage’ similar to 430–1 (n.). The adjective  is unique, like its parallel form κρυσταλλοπήξ, applied to the Strymon in Pers. 500–1 (cf. 388–453n.). By contrast,

is unique, like its parallel form κρυσταλλοπήξ, applied to the Strymon in Pers. 500–1 (cf. 388–453n.). By contrast,  (below) occurs elsewhere only in the much later Phoen. 45–6 …

(below) occurs elsewhere only in the much later Phoen. 45–6 …  δ᾽

δ᾽  / Σϕὶγξ ἁρπαγαῖσι

/ Σϕὶγξ ἁρπαγαῖσι  … (at the same verse position), while πορπάματα, ‘cloak held by a clasp (πόρπη)’ is restricted to the ends of E. El. 820 and HF 959. On the technique of supplementing a contextual echo with external material see

Introduction, 35–6, Fraenkel, Rev. 231, 233 and, for our lines in particular, A. Fries, CQ n.s. 60 (2010), 346–7 with nn. 11, 12.

… (at the same verse position), while πορπάματα, ‘cloak held by a clasp (πόρπη)’ is restricted to the ends of E. El. 820 and HF 959. On the technique of supplementing a contextual echo with external material see

Introduction, 35–6, Fraenkel, Rev. 231, 233 and, for our lines in particular, A. Fries, CQ n.s. 60 (2010), 346–7 with nn. 11, 12.

It would be possible (as some scholars do) to connect  predicatively with οἶδα: ‘No, I know that such frozen blasts as press heavily upon the Thracian sea … I have sleeplessly endured in this cloak’ (KG II 50–2, SD 394; cf. G. Pace, Lexis 27 [2009], 183–4, 185). But the circumstantial participle makes the statement more intense.

predicatively with οἶδα: ‘No, I know that such frozen blasts as press heavily upon the Thracian sea … I have sleeplessly endured in this cloak’ (KG II 50–2, SD 394; cf. G. Pace, Lexis 27 [2009], 183–4, 185). But the circumstantial participle makes the statement more intense.

πόντον Θρῄκιον (Λ:  ) seems to refer to the northern Aegean (rather than the Black Sea), which bore this designation from Homer on: Il. 23.229–30 οἳ δ᾽

) seems to refer to the northern Aegean (rather than the Black Sea), which bore this designation from Homer on: Il. 23.229–30 οἳ δ᾽  πάλιν

πάλιν  οἶκόνδε

οἶκόνδε  /

/  κατὰ

κατὰ  (i.e. Boreas and Zephyros, who blow from Thrace: Il. 9.4–6), Hdt. 7.176.1

(i.e. Boreas and Zephyros, who blow from Thrace: Il. 9.4–6), Hdt. 7.176.1

Θρῃκίου. This also accords better with the mention of the Paeonians, whose land lies west of Mt. Pangaeus. So Rhesus generally speaks of the hardships of his journey now. Cf. Liapis on 440–2.

Θρῃκίου. This also accords better with the mention of the Paeonians, whose land lies west of Mt. Pangaeus. So Rhesus generally speaks of the hardships of his journey now. Cf. Liapis on 440–2.

ϕυσήματα / κρυσταλλόπηκτα corresponds to 417  ἄησιν. The epithet, ‘congealed to ice, frozen’, is used here with the same ‘looseness of expression’ as English speaks of ‘frozen blasts’ (Porter on 441), unless, as a compound verbal adjective, it was meant to bear the causative sense ‘making freeze over’ (Feickert on 441, Liapis on 440–2 [p. 189]). Kirchhoff’s

ἄησιν. The epithet, ‘congealed to ice, frozen’, is used here with the same ‘looseness of expression’ as English speaks of ‘frozen blasts’ (Porter on 441), unless, as a compound verbal adjective, it was meant to bear the causative sense ‘making freeze over’ (Feickert on 441, Liapis on 440–2 [p. 189]). Kirchhoff’s  or

or  (I [1855], 556, on 430) would resolve the ambiguity and bring the expression even closer to Pers. 500–1 (above). But they leave the Paeonians strangely unaffected (except by ordinary storms) and weaken the ‘competition’ for the greatest discomfort in the field.

(I [1855], 556, on 430) would resolve the ambiguity and bring the expression even closer to Pers. 500–1 (above). But they leave the Paeonians strangely unaffected (except by ordinary storms) and weaken the ‘competition’ for the greatest discomfort in the field.

of strong winds is paralleled at Tro. 78–9

χάλαζαν

χάλαζαν  / πέμψει

/ πέμψει  αἰθέρος

αἰθέρος  and probably E. fr. 370.40 (Erechtheus) ϕόνια

and probably E. fr. 370.40 (Erechtheus) ϕόνια  (with Cropp). Yet with

(with Cropp). Yet with  preceding in the same line we also get a phonetic similarity to the foaming sea at Hipp. 1211 …

preceding in the same line we also get a phonetic similarity to the foaming sea at Hipp. 1211 …  ϕυσήματι. Euripides alone of the other tragedians has the word.

ϕυσήματι. Euripides alone of the other tragedians has the word.

Παίονάς τ᾽: 408–10a n. The upper-case initial and correct accentuation were given in the Aldine (παιόνας Ω)

ἐπεζάρει is J. J. Scaliger’s restoration of the MSS’ non-existent  (cf. C. Collard CQ n.s. 24 [1974], 249), which gains support from ΣVQ Rh. 441 (II 338.23 Schwartz ~ 101 Merro) ἐπεβάρει,

(cf. C. Collard CQ n.s. 24 [1974], 249), which gains support from ΣVQ Rh. 441 (II 338.23 Schwartz ~ 101 Merro) ἐπεβάρει,  (

( om. Q) and Hsch. ε 4304 Latte

om. Q) and Hsch. ε 4304 Latte  · ἐπεβάρει, ἐπέκειτο AS.

· ἐπεβάρει, ἐπέκειτο AS.  (where the codex unicus of Hesychius also seems to give -ζάτει). The true meaning and etymology of the verb are obscure. Apart from Phoen. 45–6 (above), it is attested in Σ Od. 22.9–12 (II 707.4–5 Dindorf)

(where the codex unicus of Hesychius also seems to give -ζάτει). The true meaning and etymology of the verb are obscure. Apart from Phoen. 45–6 (above), it is attested in Σ Od. 22.9–12 (II 707.4–5 Dindorf)

μεγάλου

μεγάλου  (v.l. ἐπιβαρῆσαι)

(v.l. ἐπιβαρῆσαι)

χωρίοις and, taken from some ancient text, the lemma of Hsch. ε 4303 Latte (= Phot. ε 1390 Theodoridis)

ἐπεζάρηκεν. ‘Fall upon’ or ‘oppress’ is clearly how authors and grammarians understood the word. The statement in Eust. 381.19–20 and 909.27–8 that it was Arcadian is not supported by the sound-patterns of this dialect (cf. Mastronarde on Phoen. 45).

χωρίοις and, taken from some ancient text, the lemma of Hsch. ε 4303 Latte (= Phot. ε 1390 Theodoridis)

ἐπεζάρηκεν. ‘Fall upon’ or ‘oppress’ is clearly how authors and grammarians understood the word. The statement in Eust. 381.19–20 and 909.27–8 that it was Arcadian is not supported by the sound-patterns of this dialect (cf. Mastronarde on Phoen. 45).

τοῖσδ᾽ … πορπάμασιν probably refers to the Thracian cloak called ζειρά (312–13n.), which Rhesus may be wearing on top of his armour (Liapis on 440–2 [p. 190]).

τοῖσδ᾽ … πορπάμασιν probably refers to the Thracian cloak called ζειρά (312–13n.), which Rhesus may be wearing on top of his armour (Liapis on 440–2 [p. 190]).

Porson (Appendix II, in J. Toup, Emendationes in Suidam et Hesychium … IV, Oxford 21790, 439–40; cf. G. Pace, Lexis 27 [2009], 185–6) corrected the paradosis  (Λ) and -πάσμ- (Δ).

(Λ) and -πάσμ- (Δ).  (always plural) belongs to the derivatives of feminine a-stem nouns (πόρπη) which show Doric vocalisation also in spoken verse (Nauck, Euripideische Studien II, 175, Björck, Alpha Impurum, 139–42, Rh. 513b–15n.). Thus the unanimous tradition at E. El. 820 and HF 959, as well as PV 61 πόρπασον and 141 προσπορπατός.

(always plural) belongs to the derivatives of feminine a-stem nouns (πόρπη) which show Doric vocalisation also in spoken verse (Nauck, Euripideische Studien II, 175, Björck, Alpha Impurum, 139–42, Rh. 513b–15n.). Thus the unanimous tradition at E. El. 820 and HF 959, as well as PV 61 πόρπασον and 141 προσπορπατός.

For ξύν (σύν) of clothing worn cf. Thuc. 2.70.3 and Xen. An. 4.5.33 (LSJ s.v. σύν A 4, KG I 466, SD 489). The old Attic ξύν (Λ) should be accepted on the premise that the MSS would hardly have replaced the later form (Barrett on Hipp. 40). Contrary to the evidence of inscriptions, from which  (-) had all but disappeared by 400 BC (Threatte I 553–4, II 768), Rhesus has an equal number of

(-) had all but disappeared by 400 BC (Threatte I 553–4, II 768), Rhesus has an equal number of  (-) and συν(-) in metrically indifferent positions. Especially telling is the variable use as a preposition (148, 468 σύν, 358, 471

(-) and συν(-) in metrically indifferent positions. Especially telling is the variable use as a preposition (148, 468 σύν, 358, 471  ),380 since ξυν- survived longer in literary texts.

),380 since ξυν- survived longer in literary texts.

443. The first verse-half is almost identical to Ar. Eccl. 381

νῦν ἦλθον,

νῦν ἦλθον,  αἰσχύνομαι (another reason to leave that line as it is transmitted in most MSS?). It may also have occurred in lost tragedies.

αἰσχύνομαι (another reason to leave that line as it is transmitted in most MSS?). It may also have occurred in lost tragedies.

ἀλλ᾽: in opposition to the preceding excuse, and so partly assentient (cf. GP 16–20): ‘But I did come late …’

ὕστερος: Cobet (Mnemosyne 11 [1862], 435–6) for  (ΩgV, Chr. Pat. 1728). See 411b–12n. At Ar. Eccl. 381 (above) one MS also has ὕστερον.

(ΩgV, Chr. Pat. 1728). See 411b–12n. At Ar. Eccl. 381 (above) one MS also has ὕστερον.

ἐν καιρῷ: 10, 52nn. Liapis favours ἐς καιρόν (after Chr. Pat. 1728 εἰς καιρόν) because ‘[t]ragic idiom seems to prefer ἐς καιρόν after verbs of motion’ (‘Notes’, 73). However, the passages he cites (Ai. 1168–9  μὴν ἐς

μὴν ἐς

/ πάρεισιν, Hipp. 899–900, Hec. 665–6, HF 701, Hel. 1081 ἐς καιρὸν ἦλθε, τότε δ᾽ ἄκαιρ᾽ ἀπώλλυτο, Phoen. 106, Or. 384, Rh. 52) all concern a new and/or urgent situation, often marking the entry of the character who has come ‘in time’ to learn

and possibly act on it. Rhesus, by contrast, claims to have arrived ‘at the right time’ to end a war that has already lasted for ten years (444–50). The distinction seems to be less pronounced between ἐς δέον (OT 1416, Ant. 386, Alc. 1101) and temporal ἐν δέοντι (Alc. 817, Or. 211–12, E. fr. 727c.39), more so again between εἰς καλόν and ἐν

/ πάρεισιν, Hipp. 899–900, Hec. 665–6, HF 701, Hel. 1081 ἐς καιρὸν ἦλθε, τότε δ᾽ ἄκαιρ᾽ ἀπώλλυτο, Phoen. 106, Or. 384, Rh. 52) all concern a new and/or urgent situation, often marking the entry of the character who has come ‘in time’ to learn

and possibly act on it. Rhesus, by contrast, claims to have arrived ‘at the right time’ to end a war that has already lasted for ten years (444–50). The distinction seems to be less pronounced between ἐς δέον (OT 1416, Ant. 386, Alc. 1101) and temporal ἐν δέοντι (Alc. 817, Or. 211–12, E. fr. 727c.39), more so again between εἰς καλόν and ἐν  (cf. Stevens, CEE 28).

(cf. Stevens, CEE 28).

If the above distinction is right, εἰς καιρόν does not suit Chr. Pat. 1728 either. It probably stems from a MS of Rhesus where ἐν καιρῷ had been corrupted to the commoner phrase.

444. αἰχμάζεις: Unlike αἰχμή, the verb is rare. Properly ‘to throw the spear’ (Il. 4.324), it acquired the general sense of ‘fight’: Pers. 755–6 τὸν δ᾽

/ ἔνδον αἰχμάζειν (‘play the warrior at home’), Ai. 97, Tr. 355 and absolute also Men. Sam. 628–9 εἰς Βάκτρα ποι /

/ ἔνδον αἰχμάζειν (‘play the warrior at home’), Ai. 97, Tr. 355 and absolute also Men. Sam. 628–9 εἰς Βάκτρα ποι /  Καρίαν

Καρίαν  αἰχμάζων ἐκεῖ. Cf. Sideras, Aeschylus Homericus, 76.

αἰχμάζων ἐκεῖ. Cf. Sideras, Aeschylus Homericus, 76.

445b–6. ‘… day after day you cast the dice in war against the Argives. ’

Our poet liked the dicing metaphor (154–5, 182–3nn.). Here cf. especially E. Suppl. 329–31  θ᾽ ὁρῶσα

θ᾽ ὁρῶσα  εὖ

εὖ  / ἔτ᾽

/ ἔτ᾽  ἄλλα

ἄλλα  ἐν

ἐν

/

/  (with Collard on 330–1a) and Hell. Oxy. 4.2 Chambers (below).

(with Collard on 330–1a) and Hell. Oxy. 4.2 Chambers (below).

ἡμέραν δ᾽ ἐξ ἡμέρας occurs at the same position in Henioch. fr. 5.13 PCG. Similarly Hdt. 9.8.1 ἐξ  ἐς

ἐς  and A. R. 1.861 εἰς ἦμαρ … ἐξ ἤματος. ‘Such phrases convey in all Greek literature the notion of succession, continuity’ (Headlam on Herod. 5.85

and A. R. 1.861 εἰς ἦμαρ … ἐξ ἤματος. ‘Such phrases convey in all Greek literature the notion of succession, continuity’ (Headlam on Herod. 5.85

ἐορτῆς; cf. Gow on Theoc. 18.15, Gygli-Wyss, Polyptoton, 69–71). It should thus be excluded from Fraenkel’s list of possible Ionisms (Rev. 239).

ἐορτῆς; cf. Gow on Theoc. 18.15, Gygli-Wyss, Polyptoton, 69–71). It should thus be excluded from Fraenkel’s list of possible Ionisms (Rev. 239).

… τὸν πρὸς Ἀργείους Ἄρη: Sallier’s ῥίπτεις (Histoire de l’Académie royale des inscriptions et belles-lettres 5 [1729], 125) is correct. With the transmitted

… τὸν πρὸς Ἀργείους Ἄρη: Sallier’s ῥίπτεις (Histoire de l’Académie royale des inscriptions et belles-lettres 5 [1729], 125) is correct. With the transmitted  (which may have been suggested by the ‘fall’ of dice) Rhesus’ comment would be intolerably negative (Liapis on 444–6) and the construction of

(which may have been suggested by the ‘fall’ of dice) Rhesus’ comment would be intolerably negative (Liapis on 444–6) and the construction of  unclear (LSJ s.v. II 1, Porter and Liapis take it as transitive. But at Antip. Sid. Ep. 32.13–14 and Mel. Ep. 15.2 Gow–Page HE the object is what is ‘set at stake’, which cannot well be said about ‘the war against the Argives’. Hence Feickert’s accusative of respect). In the reconstructed text we have an internal accusative (‘cast a throw in war … ’), as in 154–5 (n.) τόνδε κίνδυνον … /

unclear (LSJ s.v. II 1, Porter and Liapis take it as transitive. But at Antip. Sid. Ep. 32.13–14 and Mel. Ep. 15.2 Gow–Page HE the object is what is ‘set at stake’, which cannot well be said about ‘the war against the Argives’. Hence Feickert’s accusative of respect). In the reconstructed text we have an internal accusative (‘cast a throw in war … ’), as in 154–5 (n.) τόνδε κίνδυνον … /  and the parallels given there. Absolute

and the parallels given there. Absolute  reinforces the notion of dicing. Cf. Sept. 414 (quoted in 182–3n.), where Ares himself casts the dice of war.

reinforces the notion of dicing. Cf. Sept. 414 (quoted in 182–3n.), where Ares himself casts the dice of war.

On  by metonymy for war see LSJ s.v. II 1 (and cf. 239n.). Whatever the truth at Il. 5.909

by metonymy for war see LSJ s.v. II 1 (and cf. 239n.). Whatever the truth at Il. 5.909

(with West’s apparatus),

(with West’s apparatus),  (OQ) is the correct accusative in Attic and

(OQ) is the correct accusative in Attic and

(VL) a common error. This form, on the analogy of fourth-century and later -ην for -η in s-stem names (cf. Collard on E. Suppl. 928–9, Mastronarde on Phoen. 72), is never required by metre and appears to be absent from Attic inscriptions (LSJ s.v.

(VL) a common error. This form, on the analogy of fourth-century and later -ην for -η in s-stem names (cf. Collard on E. Suppl. 928–9, Mastronarde on Phoen. 72), is never required by metre and appears to be absent from Attic inscriptions (LSJ s.v.  I, Threatte II 274).

I, Threatte II 274).

κυβεύων: our only tragic example of the verb, although S. fr. 947.2 has κυβευτής. In the context of war also Hell. Oxy. 4.2 Chambers

| [

| [ ]

]

περὶ

περὶ  τῆς

τῆς  τοῖς μὲν | [σ]τρατηγοῖς ὠργίζοντο καὶ

τοῖς μὲν | [σ]τρατηγοῖς ὠργίζοντο καὶ

| [χο]ν ὑπολαμβάνοντες προπετῶς

| [χο]ν ὑπολαμβάνοντες προπετῶς  | [το]ὺς

| [το]ὺς  τὸν κίνδ[υ]νον καὶ κυ | [βε]ῦσαι

τὸν κίνδ[υ]νον καὶ κυ | [βε]ῦσαι

τῆς πόλεως.

τῆς πόλεως.

447–53. Without knowing it, Rhesus promises to fulfil the chorus’ wish at 368–9, although they hardly expected him to succeed in one day. The boast probably reflects the aristeia Rhesus enjoyed before his death in Pindar’s version of the myth (Introduction, 11–12, 595–641n.). The contradiction with his lengthy Scythian war (Valckenaer, Diatribe, 104–5) is likely to have passed unnoticed (Liapis on 447–9).

447–9a. ϕῶς ἓν ἡλίου: For  (ἡλίου) = ‘day’ cf. Pers. 261 καὐτὸς δ᾽

(ἡλίου) = ‘day’ cf. Pers. 261 καὐτὸς δ᾽  νόστιμον

νόστιμον  ϕάος – after the Odyssean formula … νόστιμον ἦμαρ ἰδέσθαι /

ϕάος – after the Odyssean formula … νόστιμον ἦμαρ ἰδέσθαι /  (3.233, 5.220, 6.311, 8.466) and also conveying a sense of salvation (Garvie on Pers. 261). In other such tragic periphrases (330–1n.) the notion of daylight remains stronger.

(3.233, 5.220, 6.311, 8.466) and also conveying a sense of salvation (Garvie on Pers. 261). In other such tragic periphrases (330–1n.) the notion of daylight remains stronger.

καταρκέσει: ‘will be fully sufficient’ (LSJ s.v.). The verb is very rare and in other drama found only at S. fr. 86.1 παῦσαι·  τοῦδε

τοῦδε  πατρός.

πατρός.

πύργους: 390–1a n.

ναυστάθμοις ἐπεσπεσεῖν: 135b–6n. Δ’s ναυστάθμους was an easy error between πύργους and  and given that

and given that  can also take the accusative, as at HF 34 …

can also take the accusative, as at HF 34 …  ἐπεσπεσὼν πόλιν. Liapis (on 447–9) seems too hasty in calling the dative ‘prosaic’ on account of that single tragic parallel. At OC 915, Hec. 1042 and Ba. 753 the verb stands absolute.

ἐπεσπεσὼν πόλιν. Liapis (on 447–9) seems too hasty in calling the dative ‘prosaic’ on account of that single tragic parallel. At OC 915, Hec. 1042 and Ba. 753 the verb stands absolute.

449b–50. θἠτέρᾳ: sc. ἡμέρᾳ. This form (found in Chr. Pat. 1732 cod. Vat. gr. 481) rather than Brunck’s θατέρᾳ (Euripidis tragoediae quatuor …, Strasbourg 1780, 372, on Hipp. 905) should be read for θ᾽ ἡτέρᾳ in  and the other MSS at Chr. Pat. 1732 (cf. Feickert on 449, Liapis on 449–50). In crasis of

and the other MSS at Chr. Pat. 1732 (cf. Feickert on 449, Liapis on 449–50). In crasis of  with the definite article Attic has ἁ̄τερ- and θἀ̄τερ- (from original ἅτερος: Schwyzer 401) in the masculine and neuter, while in the feminine (other than the nominative plural) only ἡτερ- and θἠτερ- are attested in inscriptions (Threatte I 431, II 345–7) and were declared correct by Pausanias the Atticist (θ 2 Erbse). Intermittent cases of feminine α-forms in ‘classical’ MSS (e.g. at OT 782, Tr. 272, Hipp. 894, Ar. Ach. 789, Henioch. fr. 5.16–17 PCG = Stob. 4.1.27) have no evidential value. In the later fourth century BC

(it seems)

with the definite article Attic has ἁ̄τερ- and θἀ̄τερ- (from original ἅτερος: Schwyzer 401) in the masculine and neuter, while in the feminine (other than the nominative plural) only ἡτερ- and θἠτερ- are attested in inscriptions (Threatte I 431, II 345–7) and were declared correct by Pausanias the Atticist (θ 2 Erbse). Intermittent cases of feminine α-forms in ‘classical’ MSS (e.g. at OT 782, Tr. 272, Hipp. 894, Ar. Ach. 789, Henioch. fr. 5.16–17 PCG = Stob. 4.1.27) have no evidential value. In the later fourth century BC

(it seems)  came to be seen as a legitimate alternative to ἕτερος, first in the masculine and neuter (Theophr. Vent. 53, Men. Mis. 164, fr. 491 PCG ὁ θάτερος, Lyc. 590, D. S. 14.22.5 τὸ δὲ θάτερον μέρος) and later also in the feminine (Luc. Bacch. 2, JTr. 11, Icar. 14, Hld. 1.2.2, 3.4.6). All three gender forms are common in late-antique and Byzantine Greek and could therefore have been introduced into our MSS (ἅτερος of three endings also occasionally appears). It follows that feminine ἁ̄τερ- and θἀ̄τερ- should not be accepted in classical Attic texts, let alone be introduced against the tradition.

came to be seen as a legitimate alternative to ἕτερος, first in the masculine and neuter (Theophr. Vent. 53, Men. Mis. 164, fr. 491 PCG ὁ θάτερος, Lyc. 590, D. S. 14.22.5 τὸ δὲ θάτερον μέρος) and later also in the feminine (Luc. Bacch. 2, JTr. 11, Icar. 14, Hld. 1.2.2, 3.4.6). All three gender forms are common in late-antique and Byzantine Greek and could therefore have been introduced into our MSS (ἅτερος of three endings also occasionally appears). It follows that feminine ἁ̄τερ- and θἀ̄τερ- should not be accepted in classical Attic texts, let alone be introduced against the tradition.

πρὸς οἶκον εἶμι: Cf. 368–9 ὦ ϕίλος,  μοι / … πράξας

μοι / … πράξας  ἐς οἶκον ἔλθοις (447–53n.).

ἐς οἶκον ἔλθοις (447–53n.).

συντεμὼν τοὺς σοὺς πόνους: ‘having cut short…’ Similarly S. fr. 941.16–17

/

/

καὶ

καὶ

and, of a pregnancy, Hdt. 5.41.2 τοῦ χρόνου συντάμνοντος.

and, of a pregnancy, Hdt. 5.41.2 τοῦ χρόνου συντάμνοντος.

451. ὑμῶν δὲ  τις ἀσπίδ᾽ ἄρηται χερί: Cf. 488 (n.) μόνος μάχεσθαι

τις ἀσπίδ᾽ ἄρηται χερί: Cf. 488 (n.) μόνος μάχεσθαι  …

…  and, for the expression, 492 (n.) οὐκ

and, for the expression, 492 (n.) οὐκ

ἀντᾶραι δόρυ, 495 … οὐ συναίρεται δόρυ. Of beginning a war e.g. Hcld. 313–14 καὶ

ἀντᾶραι δόρυ, 495 … οὐ συναίρεται δόρυ. Of beginning a war e.g. Hcld. 313–14 καὶ  ἐς

ἐς  ἐχθρὸν

ἐχθρὸν

/ μέμνησθέ μοι τήνδ᾽, Phoen. 433–4, Ba. 788–9.

/ μέμνησθέ μοι τήνδ᾽, Phoen. 433–4, Ba. 788–9.

L. Dindorf (I [1825], 490 ~ W. Dindorf, III.2 [1840], 607) rightly wrote ἄρηται, since we do not want the durative aspect of Q’s αἰρέτω (cf. Liapis, ‘Notes’, 74) and otherwise the aorist subjunctive is required in prohibitions (KG I 220, SD 315). On the corruption of ἀρ- into αἰρ- (V) or αἱρ- (OL) see 53–5n.

452–3. ‘For I shall have the mightily proud Achaeans vanquished with my spear, latecomer though I am.’

… / πέρσας: The only way to understand the MSS text is as a case of

… / πέρσας: The only way to understand the MSS text is as a case of  + aorist participle to express a permanent result (Feickert on 452).381 This is otherwise unattested in the future (KG II 61–2, W. J. Aerts, Periphrastica … , Amsterdam 1965, 128–60), but would lend a strong and effective conclusion to Rhesus’ boasts.

+ aorist participle to express a permanent result (Feickert on 452).381 This is otherwise unattested in the future (KG II 61–2, W. J. Aerts, Periphrastica … , Amsterdam 1965, 128–60), but would lend a strong and effective conclusion to Rhesus’ boasts.

Emendation in any case is difficult (cf. Liapis, ‘Notes’, 73–5). Nauck’s  …

…  (II1 [1854], XXIII) presupposes a simple error by assimilation in πέρσας (after

(II1 [1854], XXIII) presupposes a simple error by assimilation in πέρσας (after  in 452 or

in 452 or  in 448)382 and the less easy corruption of

in 448)382 and the less easy corruption of  into ἕξω, but becomes somewhat tautologous with …

into ἕξω, but becomes somewhat tautologous with …  ὕστερος μολών (though not intolerably so for our poet?). Kirchhoff’s

ὕστερος μολών (though not intolerably so for our poet?). Kirchhoff’s  ἀρήξω, which would resemble the

beginning of Eum. 232 ἐγὼ δ᾽ ἀρήξω τὸν ἱκέτην τε ῥύσομαι, founders less on the absence of an explicit object383 than on the fact that Rhesus does not merely want to ‘succour’ (Nauck, Euripideische Studien II, 174). Diggle (apud Jouan) and Kovacs (Euripidea Tertia, 147) independently proposed ἥξω … πέρσας, which makes sense only if the main emphasis can fall onto the notion of the participle. This is not the case to judge by e.g. Alc. 488

ἀρήξω, which would resemble the

beginning of Eum. 232 ἐγὼ δ᾽ ἀρήξω τὸν ἱκέτην τε ῥύσομαι, founders less on the absence of an explicit object383 than on the fact that Rhesus does not merely want to ‘succour’ (Nauck, Euripideische Studien II, 174). Diggle (apud Jouan) and Kovacs (Euripidea Tertia, 147) independently proposed ἥξω … πέρσας, which makes sense only if the main emphasis can fall onto the notion of the participle. This is not the case to judge by e.g. Alc. 488  ἄρ᾽

ἄρ᾽

μενεῖς; Hec. 930–2, Tro. 460–1 and Rh. 156–7 καὶ πάντ᾽ Ἀχαιῶν ἐκμαθὼν βουλεύματα /

μενεῖς; Hec. 930–2, Tro. 460–1 and Rh. 156–7 καὶ πάντ᾽ Ἀχαιῶν ἐκμαθὼν βουλεύματα /  (Liapis, ‘Notes’, 75). Of Diggle’s other two suggestions, ἐξαρκέσω γὰρ … πέρσας (‘For I shall succour <you> by vanquishing …’) attracts the same doubts as Kirchhoff’s reading, whereas

(Liapis, ‘Notes’, 75). Of Diggle’s other two suggestions, ἐξαρκέσω γὰρ … πέρσας (‘For I shall succour <you> by vanquishing …’) attracts the same doubts as Kirchhoff’s reading, whereas  (Holzner)384 …

(Holzner)384 …  is not only too far from the paradosis, but also ill accords with …

is not only too far from the paradosis, but also ill accords with …  ὕστερος μολών. Nothing is gained by deleting 452–3 with Herwerden (RPh 18 [1894], 84–5) or, better, 451–3 (451 could hardly end the speech on its own). The lines do not look like an addition, and one would still have to account for the text as it stands. If an interpolator could write

ὕστερος μολών. Nothing is gained by deleting 452–3 with Herwerden (RPh 18 [1894], 84–5) or, better, 451–3 (451 could hardly end the speech on its own). The lines do not look like an addition, and one would still have to account for the text as it stands. If an interpolator could write  … πέρσας, perhaps our poet could too.

… πέρσας, perhaps our poet could too.

τοὺς μέγ᾽ αὐχοῦντας … / … Ἀχαιούς: Cf. Hcld. 353 εἰ σὺ μέγ᾽  , E. fr. 1007 αὐχοῦσιν μέγα, Andr. 463 μηδὲν τόδ᾽ αὔχει and also Xerxes at Hdt. 7.103.2 (of the Spartans willing to confront a Persian army ten times the size of their own) εἰ δὲ

, E. fr. 1007 αὐχοῦσιν μέγα, Andr. 463 μηδὲν τόδ᾽ αὔχει and also Xerxes at Hdt. 7.103.2 (of the Spartans willing to confront a Persian army ten times the size of their own) εἰ δὲ

ἐόντες καὶ

ἐόντες καὶ

…

…

,

,

εἰρημένος

εἰρημένος  (Ritchie 211–12). For the meaning of

(Ritchie 211–12). For the meaning of  (properly ‘feel confident’) see Fraenkel on Ag. 1497, Barrett on Hipp. 952–5 and Kannicht on Hel. 1366–8.

(properly ‘feel confident’) see Fraenkel on Ag. 1497, Barrett on Hipp. 952–5 and Kannicht on Hel. 1366–8.

δορί (56–8n.) is to be construed with  rather than

rather than  αὐχοῦντας. Cf. Rh. 472 … ἐκπέρσαι δορί and 478 …

αὐχοῦντας. Cf. Rh. 472 … ἐκπέρσαι δορί and 478 …  … δορί.

… δορί.

καίπερ ὕστερος μολών: 411b–12, 443nn.

454–66. Impressed with Rhesus’ words and appearance, the chorus sing a brief song of praise and exhortation. It is unusual not only for replacing the regular trimeter comment after an agon speech (388–526n.), but also, as Hermann (Opuscula III, 304, 308–9) demonstrated, for responding metrically with the sentries’ own defence against the charge of laxity in 820–32 (n.).385

The phenomenon of separated stanzas in drama has been discussed in 131–6 ~ 195–200n. In extant tragedy only Hipp. 362–72 ~ 669–79 with its intervening spoken passages, choral song (Hipp. 525–64) and semi-lyric amoibaion (Hipp. 565–600) can be compared to the present case. Yet it has often been felt (e.g. by Wilamowitz, GV 587, Ritchie 331, 332–3) that the extraordinary interval of 354 lines in this short play and the fact that it includes two lyric pieces (527–64, 675–82) as well as the temporary absence of the chorus (565–674) set Rhesus apart from anything known in Greek drama.

In both its structure and language the strophe echoes the preceding ‘Hymn to Rhesus’ (342–79), but is altogether more cautious in tone (cf. Klyve on 388–526 [p. 261]). Instead of invoking Adrasteia, as in 342–3 (342–5, 342–3nn.), the chorus pray that her father Zeus may not be angered by Rhesus’ boastful speech (455b–7n.). The following accolade (458–63) repeats the desired confrontation with Achilles and other, unnamed warriors (370–9), though partly in rhetorical questions (with a potential optative) rather than imperatives and statements in the future indicative (cf. 342–79n.). Only the final wish (464–6) corresponds exactly to 368–9 (n.).

It appears, therefore, that for all their admiration the chorus are somewhat sceptical of Rhesus’ ambitions (447–53) or, in other words, our poet felt that such excessive self-praise could not go unrestrained (just as Hector provides a corrective in the dialogue to come). Even if we are to take Rhesus seriously and he will fall victim only to divine whim (342–79, 388–526nn.), our sense of foreboding is further heightened by this ode.

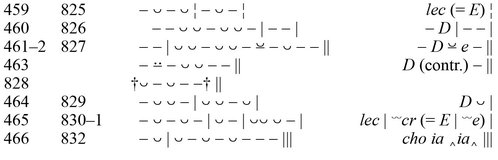

Metre

454–66 ~ 820–32. With the analysis and colometry adopted here we get a slightly unusual combination of dochmiacs with larger stretches of dactylo-epitrite metres (cf. Wilamowitz, GV 587). Yet the transition is made elegantly through the trimeter in 457 ~ 823 (beginning like a dochmiac of the form - ⋃ ⋃ - ⋃ -), a common ‘enoplian’ colon (458/824n.) and the lecythion (= E) at 459 ~ 825. Towards the end the rhythm returns to the earlier iambo-choriambics (466/832n.).

Notes

454/820  ἰώ responding with itself could also be extra metrum. But the resolved cretic neatly foreshadows the opening rhythm of the following verse.

ἰώ responding with itself could also be extra metrum. But the resolved cretic neatly foreshadows the opening rhythm of the following verse.

455/821 For a possible solution to the textual problems and lack of responsion see 821–3n.

456/822 Despite Conomis (Hermes 92 [1964], 30), the perfect correspondence, which even extends to word-ends, would seem to indicate that both lines are basically sound (for a textual interpretation of 822 see 821–3n.). The sequence ⋃ ⋃ ⋃ ⋃ ⋃ ⋃ ⋃ - is further attested among (iambo-)dochmiacs at Eum. 158 ~ 165, HF 1058  ἀδύνατά μοι and Tro. 311

ἀδύνατά μοι and Tro. 311  ὁ

ὁ  (~ 328 τυχαῖς. ὁ χορὸς ὅσιος) and usually interpreted as a resolved dochmius Kaibelianus.386 Alternatively, and in view of the word-divisions here, one could regard the colon as a dochmiac with two shorts for initial (or, at Tro. 311, second) anceps (Wilamowitz, GV 405, 588, L. P. E. Parker, CQ n.s. 18 [1968], 261 n. 3, Songs, 66). But other possible examples of

(~ 328 τυχαῖς. ὁ χορὸς ὅσιος) and usually interpreted as a resolved dochmius Kaibelianus.386 Alternatively, and in view of the word-divisions here, one could regard the colon as a dochmiac with two shorts for initial (or, at Tro. 311, second) anceps (Wilamowitz, GV 405, 588, L. P. E. Parker, CQ n.s. 18 [1968], 261 n. 3, Songs, 66). But other possible examples of  in tragedy are rare, and many scholars hesitate to admit it at all (especially Barrett, Add. on Hipp. 670 [p. 434], Diggle, Euripidea, 100–1, 167 with n. 28, 315). A well-balanced, if sceptical, record is given by R. Renehan, CPh 87 (1992), 344–6, and individual passages are defended by Bond on HF 878, Kannicht on Hel. 670 (‘Metrik’ [p. 180]), 670–1 and Dodds on Ba. 997–1001.

in tragedy are rare, and many scholars hesitate to admit it at all (especially Barrett, Add. on Hipp. 670 [p. 434], Diggle, Euripidea, 100–1, 167 with n. 28, 315). A well-balanced, if sceptical, record is given by R. Renehan, CPh 87 (1992), 344–6, and individual passages are defended by Bond on HF 878, Kannicht on Hel. 670 (‘Metrik’ [p. 180]), 670–1 and Dodds on Ba. 997–1001.

458/824 This colon, later named ‘cyrenaic’, also occurs in (iambo-) dochmiac settings at E. El. 586, 588, HF 1188, Ion 1448 and Phaeth. 276

Diggle = E. fr. 781.66.387 Elsewhere Euripides has the ‘dragged’ version ⋃ ⋃ - ⋃⋃ - ⋃ - - - (Ion 1494, Hel. 657, 680, 681, Hyps. fr. 64.94 Bond = E. fr. 759a.1615; cf. Tr. 647 ~ 655, and see Dale, LM2 171, Diggle, Euripidea, 107, 393).

460–2/826–7 Wilamowitz’ colometry (GV 587–8), which in the strophe also happens to be that of the MSS, has found favour with several scholars, most recently Liapis (on 454–66 ‘Metre’ [p. 196]). At the small cost of transposing the name Ἀχιλ(λ)εύς in 461 (461–3n.), he obtained straightforward dactylo-epitrites (for - D | - - | cf. Pi. Pyth. 1.2, Ar. Eccl. 576b and, in general, 527–64 ‘Metre’ 527–8/546–7n.), corresponding rhetorical and metrical break in strophe and antistrophe and more prominent positions for the verbal echo  (below) and the anaphora

(below) and the anaphora  … in 461–2. Compared to the traditional division of e.g. Wecklein, Murray, Diggle and Kovacs (460–1 … σέθεν κρείσσω.

… in 461–2. Compared to the traditional division of e.g. Wecklein, Murray, Diggle and Kovacs (460–1 … σέθεν κρείσσω.  ~ 826–7 … παγάς·

~ 826–7 … παγάς·  ||

||  ), this also removes one period-end after the long verse 460 ~ 826 (- D2 (contr.) | - - ||?).

), this also removes one period-end after the long verse 460 ~ 826 (- D2 (contr.) | - - ||?).

463/828 Our poet was fond of contracted D-cola. Cf. 535 ~ 554 (D - |) and 27 ~ 45, 899 ~ 910 (D2). The antistrophe here is incurably corrupt (827–8n.).

466/832 A rare clausular colon, which otherwise is found only at HF 1024 (again in juxtaposition to dochmiacs) and has variously been interpreted as cho ia ‸ia‸ or δ + ⋃ - - - (Diggle, Euripidea, 107–8, 395 with n. 108, 516). Yet here, where the preceding line is better taken as lec |  than hδ | δ and - ⋃ ⋃ - ⋃ - ⋃ - - - may be seen to echo 457 ~ 823 (cho ia ia‸), the iambo-choriambic analysis seems preferable.

than hδ | δ and - ⋃ ⋃ - ⋃ - ⋃ - - - may be seen to echo 457 ~ 823 (cho ia ia‸), the iambo-choriambic analysis seems preferable.

The responsion between 454–66 and 820–32, at least musically recognisable over the long distance, is underlined with a series of both strict and more liberal ‘isometric echoes’: 454 = 820  , 455 ϕίλα … ϕίλος ~ 821

, 455 ϕίλα … ϕίλος ~ 821  , 457 Ζεὺς θέλοι

, 457 Ζεὺς θέλοι  ~ 823 ἄγγελος ἦλθον

~ 823 ἄγγελος ἦλθον  ναῦς

ναῦς  αἴθειν (sentence structure), 459

αἴθειν (sentence structure), 459  ~ 825 οὔτ᾽ … οὔτ᾽, 461 (460)

~ 825 οὔτ᾽ … οὔτ᾽, 461 (460)  μοι ~ 827 (826)

μοι ~ 827 (826)  , 464 εἰ γάρ ~ 829 εἰ δέ. Among the other divided songs in tragedy this is proportionally matched only by Rh. 131–6 ~ 195–200 (n.). On such verbal correspondences in general see Bond on HF 763 ff. and West, GM 5 (with further literature).

, 464 εἰ γάρ ~ 829 εἰ δέ. Among the other divided songs in tragedy this is proportionally matched only by Rh. 131–6 ~ 195–200 (n.). On such verbal correspondences in general see Bond on HF 763 ff. and West, GM 5 (with further literature).

455a. ϕίλα θροεῖς: ‘You speak welcome words.’ Cf. e.g. Tr. 373 … εἰ δὲ  ϕίλα, Hec. 517, E. Suppl. 634, 643, Hdt. 7.104.1 οὐ

ϕίλα, Hec. 517, E. Suppl. 634, 643, Hdt. 7.104.1 οὐ  τοι ἐρέω.

τοι ἐρέω.

ϕίλος Διόθεν εἶ: For the concept of a ‘god-sent deliverer’ – here from the supreme patron deity of Troy – Liapis (on 455) compares Cho. 939–41  δ᾽

δ᾽  πᾶν

πᾶν  / θεόθεν

/ θεόθεν

ὡρμημένος (the chorus after Orestes’ killing of Aegisthus and Clytaemestra), which presumably inspired S. El. 69–70 (Orestes)

ὡρμημένος (the chorus after Orestes’ killing of Aegisthus and Clytaemestra), which presumably inspired S. El. 69–70 (Orestes)  γὰρ ἔρχομαι / δίκῃ

γὰρ ἔρχομαι / δίκῃ  πρὸς

πρὸς  ὡρμημένος.

ὡρμημένος.

455b–7. ‘Only may Zeus supreme wish to keep away irresistible resentment concerning your words.’

On the relationship of this invocation to that in 342–3 see 454–66n. The closest literary precedent is Pi. Ol. 13.24–6  / Ὀλυμπίας,

/ Ὀλυμπίας,  / γένοιο χρόνον ἅπαντα, Ζεῦ πάτερ.

/ γένοιο χρόνον ἅπαντα, Ζεῦ πάτερ.

Nothing has been lost after 455–7, as Wilamowitz (GV 587–8) and Zanetto (ed. Rhesus, 33, 68, Ciclope, Reso, 149 n. 64) presumed. Instead, after 821–3 (n.) we should delete the universally transmitted  στρατόν.

στρατόν.

μόνον: often in asyndeton to express ‘a reservation or an important prerequisite’ (Liapis on 455–7). In wishes to divinities also e.g. Cho. 244–5 <μόνον>  ξὺν

ξὺν  /

/  Ζηνὶ συγγένοιτό μοι, Phil. 528–9, Hipp. 522–3, E. Suppl. 1229–30 and Ar. Av. 1315

Ζηνὶ συγγένοιτό μοι, Phil. 528–9, Hipp. 522–3, E. Suppl. 1229–30 and Ar. Av. 1315  . Cf. Headlam on Herod. 2.89 and FJW on A. Suppl. 1012.

. Cf. Headlam on Herod. 2.89 and FJW on A. Suppl. 1012.

ϕθόνον ἄμαχον … / … θέλοι … εἴργειν: Cf. 343  (above). In tragedy ἄμαχος, ‘unconquerable, irresistible’, is restricted to lyrics and perhaps had an Aeschylean ring: Pers. 90, 856, Ag. 733, 769, Cho. 55 (otherwise only Ant. 799). But the comedians used it in spoken verse (e.g. Ar. Lys. 253, Antiph. fr. 7 PCG, Eub. fr. 117.2 PCG, Men. Dysc. 193, 775, 870), and it also occurs in prose (LSJ s.v. I with Suppl. [1996]).

(above). In tragedy ἄμαχος, ‘unconquerable, irresistible’, is restricted to lyrics and perhaps had an Aeschylean ring: Pers. 90, 856, Ag. 733, 769, Cho. 55 (otherwise only Ant. 799). But the comedians used it in spoken verse (e.g. Ar. Lys. 253, Antiph. fr. 7 PCG, Eub. fr. 117.2 PCG, Men. Dysc. 193, 775, 870), and it also occurs in prose (LSJ s.v. I with Suppl. [1996]).

ὕπατος / Ζεύς: Like Aeschylus and the lyric poets (Fraenkel on Ag. 55), but not, to our evidence, Sophocles and Euripides, our poet followed Homer in calling Zeus  here and in 703 (n.). Cf. Il. 19.258, Od. 19.303 (et al.)

here and in 703 (n.). Cf. Il. 19.258, Od. 19.303 (et al.)  , Il. 8.31, Od. 1.45 … ὕπατε κρειόντων, Il. 5.756, 8.22, 17.339 Ζῆν᾽ ὕπατον Κρονίδην (μήστωρα).

, Il. 8.31, Od. 1.45 … ὕπατε κρειόντων, Il. 5.756, 8.22, 17.339 Ζῆν᾽ ὕπατον Κρονίδην (μήστωρα).

458–60. ‘Neither before nor now have the ships from Argos brought (here) any man superior to you.’

Feickert (on 460) aptly compares Ai. 418–26 (Ajax)  / γείτονες ῥοαί / … / οὐκέτ᾽

/ γείτονες ῥοαί / … / οὐκέτ᾽  / τόνδ᾽

/ τόνδ᾽  … / … / οἷον

… / … / οἷον  /

/  στρατοῦ /

στρατοῦ /  χθονὸς

χθονὸς  ἀπὸ / Ἑλλανίδος. While shameless self-aggrandisement (Finglass on Ai. 421–6) is not at

issue here, we know that the chorus’ high hopes and panegyric have no basis in fact. They duly think of Achilles and Ajax in 461–3 (n.).

ἀπὸ / Ἑλλανίδος. While shameless self-aggrandisement (Finglass on Ai. 421–6) is not at

issue here, we know that the chorus’ high hopes and panegyric have no basis in fact. They duly think of Achilles and Ajax in 461–3 (n.).

τὸ δὲ νάϊον … δόρυ: The expression recalls epic δόρυ (…)  (Il. 15.410, 17.744, Od. 9.384, A. R. 3.582) and

(Il. 15.410, 17.744, Od. 9.384, A. R. 3.582) and  (Od. 9.498, h.Ap. 403, A. R. 2.79), though all of these refer to the ship’s planks. Metonymic δόρυ of the whole vessel is first attested in Sim. fr. 543.10 PMG = 271.9 Poltera and becomes very frequent in tragedy. Here the entire fleet is meant, as presumably also by IA 1494 δόρατα … νάϊ᾽ (Hartung [ναΐα]: δάϊα L).

(Od. 9.498, h.Ap. 403, A. R. 2.79), though all of these refer to the ship’s planks. Metonymic δόρυ of the whole vessel is first attested in Sim. fr. 543.10 PMG = 271.9 Poltera and becomes very frequent in tragedy. Here the entire fleet is meant, as presumably also by IA 1494 δόρατα … νάϊ᾽ (Hartung [ναΐα]: δάϊα L).

οὔτε πρίν τιν᾽ οὔτε νῦν: Nauck (II1 [1854], XXIII) for  πρὶν

πρὶν  νῦν τιν᾽ (Ω). This is the easiest, and no doubt correct, way to create responsion with 825. It ‘postulates only that

νῦν τιν᾽ (Ω). This is the easiest, and no doubt correct, way to create responsion with 825. It ‘postulates only that  was skipped after πριν and later restored in the wrong place’ (Willink, ‘Cantica’, 37 = Collected Papers, 576).

was skipped after πριν and later restored in the wrong place’ (Willink, ‘Cantica’, 37 = Collected Papers, 576).

461–3. In our play Rhesus is regularly contrasted with Achilles (314–16n.). To stress their meaning, the chorus here add Ajax – by all accounts ‘the second best fighter among the Greeks at Troy’ (Finglass on Ai. 421–6). Athena does likewise at 601–2, and when Hector has to tell Rhesus that Achilles is out of reach, he names Ajax (along with Diomedes) as coming next (497–8a n.).

πῶς μοι τὸ σὸν ἔγχος Ἀχιλλεὺς ἂν δύναιτο / …  ; With Wilamowitz’ colometry (454–66 ‘Metre’ 460–2/826–7n.) it is necessary to change the transmitted word-order

; With Wilamowitz’ colometry (454–66 ‘Metre’ 460–2/826–7n.) it is necessary to change the transmitted word-order  (V: -λλ- OΛ)

(V: -λλ- OΛ)  σὸν

σὸν  … in order to avoid hiatus after the second position in the verse. Apart from the metrical and rhetorical advantages of this arrangement (discussed above), there may also be a textual argument. While in Euripidean anapaests and lyrics epic Ἀχιλ- is lectio difficilior for Ἀχιλλ- (Hec. [94], 108, 128, El. 439, IT 436–7, IA 124, 128),388 it need not be the original here. The scribe of V had a tendency to write single for double consonants (with Ἀχιλλ- also 182, 491, 977;389 cf. Tro. 39, 264, 575, 623, 1124, Or. 1657). The same could have happened in the present passage, after Ἀχιλλεύς had been misplaced in an early source (either to normalise the word-order or because it was left out and wrongly reinserted from a note).