reinforces the first

reinforces the first  and so the character of the whole clause as the conclusion to be drawn from the previously observable ‘signs’ (GP 213–14, G. Wakker, Conditions and Conditionals …, Amsterdam 1994, 351 n. 100 = NAGP, 216 n. 17). Similarly e.g. Pers. 433–4 αἰαῖ,

and so the character of the whole clause as the conclusion to be drawn from the previously observable ‘signs’ (GP 213–14, G. Wakker, Conditions and Conditionals …, Amsterdam 1994, 351 n. 100 = NAGP, 216 n. 17). Similarly e.g. Pers. 433–4 αἰαῖ,

/

/

(the Queen upon hearing about the battle of Salamis), Sept. 655, Ar. Thesm. 1227–9, Eccl. 1163.

(the Queen upon hearing about the battle of Salamis), Sept. 655, Ar. Thesm. 1227–9, Eccl. 1163.

καί τις προδρόμων ὅδε γ᾽ ἐστὶν ἀστήρ: Musgrave (Exercitationes, 95 ~ II [1778], on 538) for the MSS’  (Δ:

(Δ:

423 The phrase probably echoes Ion fr. 745 PMG ἀοῖον

423 The phrase probably echoes Ion fr. 745 PMG ἀοῖον  /

/  μείναμεν, ἀελίου /

μείναμεν, ἀελίου /

Bentley) πρόδρομον, the beginning of a dithyramb well enough known to be alluded to in Ar. Pax 835–7. For πρόδρομος, ‘precursor’, cf. also Ar. fr. 346.1 PCG

Bentley) πρόδρομον, the beginning of a dithyramb well enough known to be alluded to in Ar. Pax 835–7. For πρόδρομος, ‘precursor’, cf. also Ar. fr. 346.1 PCG

and Eub. fr. 75.13 PCG

and Eub. fr. 75.13 PCG

ἄριστον (LSJ s.v. I 3). In other tragedy the adjective tends to mean ‘rushing forward’: Sept. 80 (with Hutchinson), 211, Ant. 108. The Herald at IA [424–5]

ἄριστον (LSJ s.v. I 3). In other tragedy the adjective tends to mean ‘rushing forward’: Sept. 80 (with Hutchinson), 211, Ant. 108. The Herald at IA [424–5]  δὲ πρόδρομος … /

δὲ πρόδρομος … /  combines the notions of speed and advance movement.

combines the notions of speed and advance movement.

Again the star in question is not specified (cf. 527–30, 534nn.), but as in Ion fr. 745 PMG (above), Venus presents itself.

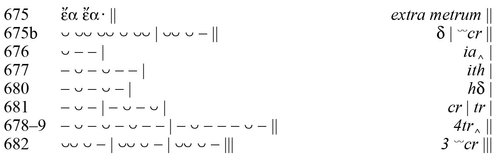

538–45. With a view to naming the overdue relief contingent, the chorus now recall the rota of night watches as established by lot (543–5n.). The transmitted speaker distribution in this lively anapaestic dialogue, which roughly corresponds to 557–64 (n.), largely coincides with what can be deduced from the text. Division into semi-choruses would be the most economic solution, but utterances by up to four individual choreutae cannot be ruled out (Liapis on 538–45).

The generally accepted order of night-watches, already advocated by Aristarchus (ΣV Rh. 540 [II 341.15–16 Schwartz = 107 Merro]),424 is 1. Paeonians, 2. Cilicians, 3. Mysians, 4. Trojans, 5. Lycians. There is hardly a problem in transferring the leadership of Mygdon’s son Coroebus from the Phrygians to the Paeonians (539n.), nor does the fact that the Cilicians are not said to have roused the Mysians affect our understanding of the passage (Feickert on 538–45). Crates of Mallus, by contrast, who assigns the first watch to the Phrygians (οἱ  Κόροιβον), the second to the Paeonians and then equates the Cilicians with the Mysians for the third (ΣV Rh. 5 [II 326.13–327.4 Schwartz = 78.7–15 Merro]425 = Crates fr. 88.21–30 Broggiato), is severely criticised in the remaining ΣV Rh. 5 (II 327.4–15 Schwartz = 78.15–27 Merro). Even apart from the erroneous reference to the Mysians of Thrace (Il. 13.4–7) – Crates meant the Anatolian branch (Il. 2.858–61) located near the Homeric Cilicians around Thebe (Il. 6.395–7, 414–16) – one does not see why our poet should have confused these peoples (540–2n.) or, if he did, why he expressed himself in such unclear terms. Moreover, a guard turn taken by the Phrygians under Coroebus would contradict their identification with the Trojans elsewhere in Rhesus (32n.).

Κόροιβον), the second to the Paeonians and then equates the Cilicians with the Mysians for the third (ΣV Rh. 5 [II 326.13–327.4 Schwartz = 78.7–15 Merro]425 = Crates fr. 88.21–30 Broggiato), is severely criticised in the remaining ΣV Rh. 5 (II 327.4–15 Schwartz = 78.15–27 Merro). Even apart from the erroneous reference to the Mysians of Thrace (Il. 13.4–7) – Crates meant the Anatolian branch (Il. 2.858–61) located near the Homeric Cilicians around Thebe (Il. 6.395–7, 414–16) – one does not see why our poet should have confused these peoples (540–2n.) or, if he did, why he expressed himself in such unclear terms. Moreover, a guard turn taken by the Phrygians under Coroebus would contradict their identification with the Trojans elsewhere in Rhesus (32n.).

Except for the Cilicians, who do not play an important part in the Iliad (540–2n.), all the Trojan allies here are also mentioned in Il. 10.428–31

Κᾶρες καὶ Παίονες

Κᾶρες καὶ Παίονες  / καὶ

/ καὶ  καὶ Καύκωνες δῖοί τε

καὶ Καύκωνες δῖοί τε  · /

· /

δ᾽ ἔλαχον

δ᾽ ἔλαχον  Μυσοί

Μυσοί

/ καὶ Φρύγες

/ καὶ Φρύγες  καὶ Μῃόνες ἱπποκορυσταί. Dolon’s list again largely ‘tallies with that of the ‘middle distant’ allies named in the Trojan Catalogue’ (Hainsworth on Il. 10.428–31; cf. Il. 2.840–77, Rh. 539, 540–2, 543–5nn.).

καὶ Μῃόνες ἱπποκορυσταί. Dolon’s list again largely ‘tallies with that of the ‘middle distant’ allies named in the Trojan Catalogue’ (Hainsworth on Il. 10.428–31; cf. Il. 2.840–77, Rh. 539, 540–2, 543–5nn.).

ΣV Rh. 5 (II 326.7–10 Schwartz = 77.1–78.4 Merro) records a set of five night watches already for Stesichorus (fr. 268 PMGF) and, depending on the reconstruction of the text, also Simonides (fr. 644 PMG = 317 Poltera), while Homer divided night and day into three parts: Il.

10.252–3  δὲ

δὲ  νύξ / τῶν

νύξ / τῶν  μοιράων,

μοιράων,  δ᾽ ἔτι μοῖρα

δ᾽ ἔτι μοῖρα  (cf. ΣA Il. 10.252 [III 48.16–49.1 Erbse]

(cf. ΣA Il. 10.252 [III 48.16–49.1 Erbse]  γὰρ

γὰρ  καθ᾽

καθ᾽

),426 Od. 12.312, 14.483, Il. 21.111

),426 Od. 12.312, 14.483, Il. 21.111

ἠὼς

ἠὼς  δειέλη ἢ μέσον ἦμαρ. In real life the number of shifts probably depended on the circumstances (e.g. Xen. Cyr. 5.3.44, Aen. Tact. 1.8, 22.4–5), but four are specially attested (Aen. Tact. 18.21, Arr. An. 5.24.2, Curt. 7.2.19) and became standard in the Roman army (Prop. 4.4.63–4, Veget. Epit. rei mil. 3.8.17; cf. Plin. N.H. 10.21.47).

δειέλη ἢ μέσον ἦμαρ. In real life the number of shifts probably depended on the circumstances (e.g. Xen. Cyr. 5.3.44, Aen. Tact. 1.8, 22.4–5), but four are specially attested (Aen. Tact. 18.21, Arr. An. 5.24.2, Curt. 7.2.19) and became standard in the Roman army (Prop. 4.4.63–4, Veget. Epit. rei mil. 3.8.17; cf. Plin. N.H. 10.21.47).

538. ‘Who was summoned to take the first watch’?

has been variously derived from (a) κηρύσσω τινί τι, which in the passive retains its accusative object, while the dative of the person is turned into a nominative (KG I 125, SD 241; cf. Thuc. 1.126.11 οἱ

ἐπιτετραμμένοι

ἐπιτετραμμένοι  ϕυλακήν); or (b) κηρύσσω τινά with an accusative of direction (

ϕυλακήν); or (b) κηρύσσω τινά with an accusative of direction ( ϕυλακήν), analogous to e.g. Il. 2.51 (~ 443) κηρύσσειν ἀγορήνδε (πόλεμόνδε)

ϕυλακήν), analogous to e.g. Il. 2.51 (~ 443) κηρύσσειν ἀγορήνδε (πόλεμόνδε)  κομόωντας

κομόωντας  and 10.195 Ἀργείων βασιλῆες, ὅσοι κεκλήατο βουλήν (LSJ s.v.

and 10.195 Ἀργείων βασιλῆες, ὅσοι κεκλήατο βουλήν (LSJ s.v.  II 1 with Suppl. [1996]). The first construction is unparalleled with κηρύσσω, but may still be easier than the second, since in order to serve as a ‘goal of motion’,

II 1 with Suppl. [1996]). The first construction is unparalleled with κηρύσσω, but may still be easier than the second, since in order to serve as a ‘goal of motion’,  should carry a notion of place, as do ἀγορή,

should carry a notion of place, as do ἀγορή,  and

and  above (cf. BK on Il. 2.51). This, however, does not apply here where the order, not the position, of the watches is at issue.

above (cf. BK on Il. 2.51). This, however, does not apply here where the order, not the position, of the watches is at issue.

Dobree’s  (Adversaria II [1833], 87 = IV [1874], 84), taken as middle in sense (cf. Schwyzer 760–1, Wackernagel, Vorlesungen über Syntax I, 137–9 = Lectures on Syntax, 179–81), would reduce the linguistic difficulty. But the error would be hard to explain in this context, which also favours the paradosis on independent grounds: the

(Adversaria II [1833], 87 = IV [1874], 84), taken as middle in sense (cf. Schwyzer 760–1, Wackernagel, Vorlesungen über Syntax I, 137–9 = Lectures on Syntax, 179–81), would reduce the linguistic difficulty. But the error would be hard to explain in this context, which also favours the paradosis on independent grounds: the  (implied in the verb) probably oversaw the drawing of the lots (cf. Il. 7.181–9) and subsequently proclaimed its result (Liapis on 538).

(implied in the verb) probably oversaw the drawing of the lots (cf. Il. 7.181–9) and subsequently proclaimed its result (Liapis on 538).

539. Μυγδόνος υἱόν … Κόροιβον: Coroebus first appears in the Little Iliad (fr. 24 GEF = Paus. 10.27.1, describing Polygnotus’ murals in the Cnidian Lesche at Delphi). He came to Troy to marry Cassandra (cf. Verg. Aen. 2.341–6) and died fighting within the city walls, at the hands of varying Greek heroes. His father Mygdon ruled over the Phrygians (Il. 3.184–9), whom according to Pausanias (10.27.1) the poets called ‘Mygdones’ after him. In view of his non-Greek name (von Kamptz, Homerische Personennamen, 135, 328–9) and the ‘conspicuous’ tomb he possessed near Stektorion (Paus. 10.27.1), it would not have been difficult to regard him as the eponym of Mygdonia on the south coast of the Propontis (cf. Horsfall on Verg. Aen. 2.342). The original branch of the Thracian tribe which gave the region its name settled east of the river Axius, whence Mygdon’s son could have become the leader of the neighbouring Paeonians (Vater on 526 [p. 208]; cf. Ammendola on 538–39 and Porter on 539).

As another late ally unable to save Troy, Coroebus bears some similarity to Rhesus and may thus have been brought in here against chronology.

540–2. τίς γὰρ ἐπ᾽ αὐτῷ; For this use of ‘progressive’ γάρ in a question, by which the speaker, ‘having been satisfied on one subject, wishes to learn something further’ (GP 81), cf. e.g. Ag. 630–1, Ai. 99–101 (Ἀθ.)  ἅνδρες,

ἅνδρες,  τὸ σὸν ξυνῆκ᾽ ἐγώ. / (Αι.) θανόντες

τὸ σὸν ξυνῆκ᾽ ἐγώ. / (Αι.) θανόντες  τἄμ᾽

τἄμ᾽  ὅπλα. / (Αθ.) εἶἑν· τί γὰρ

ὅπλα. / (Αθ.) εἶἑν· τί γὰρ

ὁ τοῦ

ὁ τοῦ  ; IT 531–3, Ar. Av. 298–9 (GP 82–3). The general force of the particle appears to be resultative: ‘Because so-and-so is the case, I now ask …’ (KG II 335–6).

; IT 531–3, Ar. Av. 298–9 (GP 82–3). The general force of the particle appears to be resultative: ‘Because so-and-so is the case, I now ask …’ (KG II 335–6).

Κίλικας probably refers to (or would have been taken to refer to) the historical Cilicians of south-eastern Asia Minor, not the small Iliadic people inhabiting the Adramyttian plain (Il. 6.395–7). Despite Hector’s marriage to Andromache, the daughter of their king Eetion, they are never mentioned as Trojan allies and get sad prominence only as victims of one of Achilles’ raids (especially Il. 1.366–9, 6.414–28; cf. Kirk on 6.395–7) .

Παίων / στρατός: Under a different leader, this host is introduced at Il. 2.848–50 αὐτὰρ Πυραίχμης ἄγε Παίονας  /

/

Ἀμυδῶνος,

Ἀμυδῶνος,

εὐρὺ ῥέοντος, / Ἀξιοῦ,

εὐρὺ ῥέοντος, / Ἀξιοῦ,

ἐπικίδναται αἶαν. Pyraichmes falls in battle with Patroclus (Il. 16.287–8) and is replaced by Asteropaios, who claims the river Axius as his grandfather (Il. 21.140–3, 157–60) and puts up a remarkable fight with Achilles (Il. 21.139–204). After his death the Paeonians retreat in confusion (Il. 21.205–11).

ἐπικίδναται αἶαν. Pyraichmes falls in battle with Patroclus (Il. 16.287–8) and is replaced by Asteropaios, who claims the river Axius as his grandfather (Il. 21.140–3, 157–60) and puts up a remarkable fight with Achilles (Il. 21.139–204). After his death the Paeonians retreat in confusion (Il. 21.205–11).

Μυσοὶ δ᾽ ἡμᾶς: For the Mysians (occupying northern central Asia Minor) see Il. 2.858–61 (with Kirk on 858). Their counterparts from opposite the Propontis, who were later called Μοισοί or Moesi, did not take part in the Trojan war: Il. 13.4–7 (with Janko).

The Trojans are serving on the fourth watch, as they themselves stated in 5–6 (n.).

543–5. ‘Then is it not high time to go and rouse the Lycians to take the fifth watch according to the lot’s apportionment?’

These verses are almost literally repeated at 562–4 (n.), where they mark the chorus’ exit and, together with the present passage, give the effect of an ephymnium.

οὔκουν: 161–2a n. V and O here have οὐκ οὖν, on which see GP 424, 439–40.

Λυκίους: The Lycians are not only the most significant Trojan allies in the Iliad, but also among the geographically remotest and therefore stand at the very end of the Catalogue: Il. 2.876–7  δ᾽

δ᾽

/

/

,

,

δινήεντος. Sarpedon is mentioned in 29 (28–9n.). As in 224–6 (224–5n.) Λυκίας / ναὸν

δινήεντος. Sarpedon is mentioned in 29 (28–9n.). As in 224–6 (224–5n.) Λυκίας / ναὸν  / Ἄπολλον, the audience may here have been reminded of ‘wolf-men’, at least on the second occasion (562–4), when the chorus had just been discussing Dolon’s fate (557–61n.).

/ Ἄπολλον, the audience may here have been reminded of ‘wolf-men’, at least on the second occasion (562–4), when the chorus had just been discussing Dolon’s fate (557–61n.).

ϕυλακήν: literally ‘as the fifth’, perhaps with a final undertone comparable to that of

ϕυλακήν: literally ‘as the fifth’, perhaps with a final undertone comparable to that of  with the accusative of a noun of action: cf. e.g. Hes. Op. 20

with the accusative of a noun of action: cf. e.g. Hes. Op. 20  καὶ

καὶ

ὅμως

ὅμως  ἔργον ἔγειρεν, Od. 12.439

ἔργον ἔγειρεν, Od. 12.439  δ᾽

δ᾽

ἀνέστη, Xen. Cyr. 1.2.9 ὅταν δὲ ἐξίῃ

ἀνέστη, Xen. Cyr. 1.2.9 ὅταν δὲ ἐξίῃ

(LSJ s.v.

(LSJ s.v.  C III 1). This would still differ from a true accusative of direction (Feickert on 545), which might be possible with ἐγείρω, but seems again ruled out here by πέμπτην (538n.).

C III 1). This would still differ from a true accusative of direction (Feickert on 545), which might be possible with ἐγείρω, but seems again ruled out here by πέμπτην (538n.).

καιρός: 10n.

κλήρου κατὰ μοῖραν probably reflects contemporary Greek army practice, although no other information on the subject survives. For the Romans cf. Plb. 6.35.11, 6.36.1 (cavalry-men doing allotted rounds) and especially Jos. BJ 5.510–11

(sc. ϕυλακήν) δ᾽

(sc. ϕυλακήν) δ᾽  οἱ

οἱ

ἡγεμόνες.

ἡγεμόνες.  δ᾽ οἱ

δ᾽ οἱ

ὕπνους, καὶ δι᾽

ὕπνους, καὶ δι᾽  νυκτὸς

νυκτὸς

[τὰ]

[τὰ]

ϕρουρίων.

ϕρουρίων.

546–50. ‘Listen – I hear her! The nightingale, killer of her son, is sitting in her blood-stained nest by the Simois and singing her sorrowful melody with a voice of so many notes.’

Among the sounds accompanying daybreak, the nightingale’s song is also mentioned at Phaeth. 67–70 Diggle = E. fr. 773.23–6  δὲ δένδρεσι λεπ- / τὰν

δὲ δένδρεσι λεπ- / τὰν  ἁρμονίαν /

ἁρμονίαν /  γόοις /

γόοις /

(with Diggle on 70 [pp. 101–2] + AC 65 [1996], 193–4). More often in tragedy it transcends pure scene-description by serving –on the model of Od. 19.518–24 – as a paradigm of female grief and lamentation: e.g. A. Suppl. 57–76, Ag. 1140–9, Ai. 624–34, S. El. 103–9, 147–9, 1074–7, Hel. 1107–12 (A. Barker, in P. Murray – P. Wilson [eds.], Music and the Muses. The Culture of ‘Mousikē ’ in the Classical Athenian City, Oxford 2004, 189–91).

(with Diggle on 70 [pp. 101–2] + AC 65 [1996], 193–4). More often in tragedy it transcends pure scene-description by serving –on the model of Od. 19.518–24 – as a paradigm of female grief and lamentation: e.g. A. Suppl. 57–76, Ag. 1140–9, Ai. 624–34, S. El. 103–9, 147–9, 1074–7, Hel. 1107–12 (A. Barker, in P. Murray – P. Wilson [eds.], Music and the Muses. The Culture of ‘Mousikē ’ in the Classical Athenian City, Oxford 2004, 189–91).

The Attic tale of Aēdōn-Procne was already known to Hesiod (Op. 568–9 [with West on 568], fr. 312; cf. Sapph. fr. 135 Voigt) and received its canonical form in S. Tereus (frr. 580–595b). On this, and the possible variant behind Od. 19.518–24 (Σ Od. 19.518 [II 683.19–27 Dindorf] = Pherecyd. FGrHist 3 F 124 = fr. 124 Fowler), see P. M. C. Forbes Irving, Metamorphosis in Greek Myths, Oxford 1990, 248–9 and A. H. Sommerstein – D. Fitzpatrick, in Sophocles. Selected Fragmentary Plays I, 142–9 (Tereus).

The ‘violent beauty of the Nightingale passage’ (G. H. Macurdy, AJPh 64 [1943], 410) should not be understood as foreshadowing the deaths and sufferings that inform the latter part of our play. As in Phaethon, its significance is restricted to the immediate context of the ode. Cf. Diggle on Phaeth. 70 (pp. 100–1) and Collard on Phaeth. 63–101 (p. 226).

καὶ μάν: ‘calling attention to something just seen or heard’ (GP 356–7; cf. G. Wakker, in NAGP, 227–9), as in e.g. Sept. 245 καὶ μὴν  γ᾽ ἱππικῶν ϕρυαγμάτων, Andr. 820–1, Ion 201–2, Ar. Ran. 285. Typical of drama, this usage of

γ᾽ ἱππικῶν ϕρυαγμάτων, Andr. 820–1, Ion 201–2, Ar. Ran. 285. Typical of drama, this usage of

is closely akin to that in entry announcements (85–6n.).

is closely akin to that in entry announcements (85–6n.).

The MSS have καὶ μὴν. Diggle introduced the Doric form appropriate to lyrics.

Σιμόεντος ἡμένα κοίτας / ϕοινίας: the same combination of a spatial-cognate accusative (with verbs of ‘resting’) and a partitive-local genitive as at OT 161 Ἄρτεμιν, ἃ κυκλόεντ᾽ ἀγορᾶς θρόνον εὐκλέα θάσσει(with Dawe2 on 161). Each case construction, if separate, is com  (with Dawe2 on 161). Each case construction, if separate, is common in tragedy. For the accusative see e.g. Ag. 182–3

(with Dawe2 on 161). Each case construction, if separate, is common in tragedy. For the accusative see e.g. Ag. 182–3  … / … σέλμα σεμνὸν ἡμένων, OT 2, Phil. 144–5, Andr. 117, E. Suppl. 987 (KG I 313–14 n. 13, SD 76), for the genitive Pi. Pyth. 4.56 Νείλοιο

… / … σέλμα σεμνὸν ἡμένων, OT 2, Phil. 144–5, Andr. 117, E. Suppl. 987 (KG I 313–14 n. 13, SD 76), for the genitive Pi. Pyth. 4.56 Νείλοιο

(‘to the rich precinct of Cronus’ son by the Nile’), Phil. 489, Ion 154–5

(‘to the rich precinct of Cronus’ son by the Nile’), Phil. 489, Ion 154–5

/ πτανοὶ

/ πτανοὶ  κοίτας, 892, Hyps. fr. I iv.21, 24–5 Bond = E. fr. 752h.21, 24–5.

κοίτας, 892, Hyps. fr. I iv.21, 24–5 Bond = E. fr. 752h.21, 24–5.

Poetic (and real) nightingales favour river-banks: Alcm. (?) fr. 10 (a).6–7 PMGF ἄκουσα τᾶν ἀηδ[όνων ταὶ] / παρ᾽  [ῥοαῖσ(ι) … (suppl. Page), A. Suppl. 62–4 ἀηδόνος, / ἅτ᾽

[ῥοαῖσ(ι) … (suppl. Page), A. Suppl. 62–4 ἀηδόνος, / ἅτ᾽

[τ᾽]

[τ᾽]  /

/  νέον οἶτον

νέον οἶτον  (with FJW on 63 and for the text West, Studies, 129–30), [Mosch.] 3.9–10, Ant. Lib. 11.11. Here her nest is ‘blood-stained’ – not from the battles raging before Troy (G. H. Macurdy, AJPh 64 [1943], 410, Feickert on 547), but, implicitly, from the murder of her child. 427

(with FJW on 63 and for the text West, Studies, 129–30), [Mosch.] 3.9–10, Ant. Lib. 11.11. Here her nest is ‘blood-stained’ – not from the battles raging before Troy (G. H. Macurdy, AJPh 64 [1943], 410, Feickert on 547), but, implicitly, from the murder of her child. 427

ὑμνεῖ: ΣV Rh. 547 (II 341.21–2 Schwartz = 108 Merro) records  as a γράϕεται-variant. This could stand with

as a γράϕεται-variant. This could stand with  … μέριμναν (below), but looks rather like a gloss by someone who, like the scholiast, took

… μέριμναν (below), but looks rather like a gloss by someone who, like the scholiast, took  ϕοινίας to be the object of the verb. See also Liapis, ‘Notes’, 79–80.

ϕοινίας to be the object of the verb. See also Liapis, ‘Notes’, 79–80.

πολυχορδοτάτᾳ / γήρυϊ emphasises the variety of the nightingale’s song, already famed at Od. 19.521

(Diggle on Phaeth. 67 f. with further references). Cf. especially Med. 196–7 μούσῃ καὶ πολυχόρδοις / ᾠδαῖς, Lyr. adesp. fr. 947 (b) PMG

(Diggle on Phaeth. 67 f. with further references). Cf. especially Med. 196–7 μούσῃ καὶ πολυχόρδοις / ᾠδαῖς, Lyr. adesp. fr. 947 (b) PMG

… / τερπνοτάτων μελέων

… / τερπνοτάτων μελέων

(with ‘strings’ for ‘notes’, as here) and Theoc. 16.44–5 εἰ μὴ θεῖος

(with ‘strings’ for ‘notes’, as here) and Theoc. 16.44–5 εἰ μὴ θεῖος  ὁ Κήιος αἰόλα

ὁ Κήιος αἰόλα  /

/  ἐς πολύχορδον. To the audience

ἐς πολύχορδον. To the audience  may also have suggested the (notorious) intricacies of the ‘New Music’: Pherecr. fr. 155 PCG, Pl. Rep. 399c7–d5, Phaenias fr. 32 Wehrli, Artemon fr. 11 FHG IV 342, [Plut.] De mus. 18.1137a–b, 20–21.1137f (probably after Aristoxenus). See Denniston apud Page on Med. 196 and in general West, Ancient Greek Music, 356–72. Barker (in Music and the Muses, 185–204) takes the Nightingale in Ar. Birds as an emblem of that ‘new’ style.

may also have suggested the (notorious) intricacies of the ‘New Music’: Pherecr. fr. 155 PCG, Pl. Rep. 399c7–d5, Phaenias fr. 32 Wehrli, Artemon fr. 11 FHG IV 342, [Plut.] De mus. 18.1137a–b, 20–21.1137f (probably after Aristoxenus). See Denniston apud Page on Med. 196 and in general West, Ancient Greek Music, 356–72. Barker (in Music and the Muses, 185–204) takes the Nightingale in Ar. Birds as an emblem of that ‘new’ style.

παιδολέτωρ / …  : Cf. particularly S. El. 107

: Cf. particularly S. El. 107  …

…  (where the adjective is a hapax) and, perhaps under Euripidean influence, Nonn. D. 48.748

(where the adjective is a hapax) and, perhaps under Euripidean influence, Nonn. D. 48.748

(~ Med. 848–9

(~ Med. 848–9  … /

… /  παιδολέτειραν). Feminine

παιδολέτειραν). Feminine  also occurs in Sept. 726 and Med. 1393 (again of Medea). It may be an Aeschylean coinage, taken over by Euripides (Ritchie 167).

also occurs in Sept. 726 and Med. 1393 (again of Medea). It may be an Aeschylean coinage, taken over by Euripides (Ritchie 167).

Apart from, perhaps, the metaphor at Archil. fr. 263 IEG (= Hsch. α 1501 Latte), this is the only case of  for

for  before the Hellenistic age: Theoc. 8.38, Call. Lav. Pall. 94, Aet. fr. 1.16 Pf.

before the Hellenistic age: Theoc. 8.38, Call. Lav. Pall. 94, Aet. fr. 1.16 Pf.  [

[ ]

]

μελιχρ[ό]τεραι (suppl. Housman, prob. Pfeiffer), Noss. Ep. 10.3 Gow–Page HE, Posidipp. Ep. 37.6 Austin–Bastianini. Similarly ἀδονίς in Theoc. Ep. 4.11 Gow and [Mosch.] 3.46.

μελιχρ[ό]τεραι (suppl. Housman, prob. Pfeiffer), Noss. Ep. 10.3 Gow–Page HE, Posidipp. Ep. 37.6 Austin–Bastianini. Similarly ἀδονίς in Theoc. Ep. 4.11 Gow and [Mosch.] 3.46.

μελοποιὸν … μέριμναν: Dindorf (III.2 [1840], 611) for the MSS’  … μέριμνα (μελω- … μερίμνᾳ Q), which is impossible to construe. μέριμνα as the subject of ὑμνεῖ and

… μέριμνα (μελω- … μερίμνᾳ Q), which is impossible to construe. μέριμνα as the subject of ὑμνεῖ and  cannot be excused by reference to Bacch. 19.8–11 ὕϕαινέ νυν … / … τι καινὸν / … /

cannot be excused by reference to Bacch. 19.8–11 ὕϕαινέ νυν … / … τι καινὸν / … /  Κηΐα μέριμνα (i.e. the poet), and the chain of three attributes (including adjectival ἀηδονίς!) that would depend on the single noun seems intolerable. Placing

Κηΐα μέριμνα (i.e. the poet), and the chain of three attributes (including adjectival ἀηδονίς!) that would depend on the single noun seems intolerable. Placing  … μέριμνα in apposition to

… μέριμνα in apposition to  / … ἀηδονίς (D. Ebener, WZRostock 12 [1963], 205) is ruled out by the word-order (Feickert on 550), and the problem of metaphorical μέριμνα for the nightingale’s (as opposed to a human poet’s) compositional pursuits would remain. Both interpretations, moreover, entail taking

/ … ἀηδονίς (D. Ebener, WZRostock 12 [1963], 205) is ruled out by the word-order (Feickert on 550), and the problem of metaphorical μέριμνα for the nightingale’s (as opposed to a human poet’s) compositional pursuits would remain. Both interpretations, moreover, entail taking  as an isolated local genitive with

as an isolated local genitive with  and

and

as the object of

as the object of  .428

.428

Reiske (Animadversiones, 89) had already written μέριμναν, but Dindorf’s text (adopted by Murray, Diggle, Kovacs, Feickert and Liapis) achieves a better distribution of epithets. The error was easy – from the preceding nominatives as well as, perhaps, the more natural application of  to the ‘maker of the song’ (LSJ s.v. I). Note, however, Hec. 917–18

to the ‘maker of the song’ (LSJ s.v. I). Note, however, Hec. 917–18  /

/  (‘sacrifice leading to dances’). At Hipp. 1428–9 ἀεὶ δὲ

(‘sacrifice leading to dances’). At Hipp. 1428–9 ἀεὶ δὲ  ἐς σὲ

ἐς σὲ  / ἔσται μέριμνα (a possible model of our passage) the adjective retains its proper force.

/ ἔσται μέριμνα (a possible model of our passage) the adjective retains its proper force.

It may be significant that μέριμνα occurs (in a different context) at Phaeth. 87 Diggle = E. fr. 773.43. On our poet’s fondness for adjectives in  see 651n.

see 651n.

551–3. ‘And they are already grazing their flocks on Mount Ida. I plainly hear the voice of the shepherd’s pipe, sounding through the night.’

In both expression and content these lines closely resemble Phaeth. 71–6 Diggle = E. fr. 773.27–32  δ᾽

δ᾽  / κινοῦσιν

/ κινοῦσιν

… 75 = 31

… 75 = 31  δ᾽ εἰς ἔργα κυνα- / γοὶ

δ᾽ εἰς ἔργα κυνα- / γοὶ  θηροϕόνοι, which also come immediately after the nightingale motif at Phaeth. 67–70 Diggle = E. fr. 773.23–6 (546–50n.).

θηροϕόνοι, which also come immediately after the nightingale motif at Phaeth. 67–70 Diggle = E. fr. 773.23–6 (546–50n.).

δέ: Cf. Phaeth. 75 Diggle = E. fr. 773.31 (above). On the time-scale of Rhesus, it is the shepherds whose activities merit comment.

δέ: Cf. Phaeth. 75 Diggle = E. fr. 773.31 (above). On the time-scale of Rhesus, it is the shepherds whose activities merit comment.

νυκτιβρόμου / σύριγγος likewise acknowledges the early hour. Pierson’s  (Verisimilium I, 33–4) for νυκτιδρόμου (Δ: νυκτὶ δρόμου Λ) has won general acceptance, despite being a new formation after

(Verisimilium I, 33–4) for νυκτιδρόμου (Δ: νυκτὶ δρόμου Λ) has won general acceptance, despite being a new formation after  and its kind (e.g. Hel. 1351

and its kind (e.g. Hel. 1351  αὐλόν, Ba. 156, Ar. Nub. 313, Arch. Ep. 17.5 Gow–Page GPh

αὐλόν, Ba. 156, Ar. Nub. 313, Arch. Ep. 17.5 Gow–Page GPh

μελίβρομον). Pace (in Scritti Gallo, 458–9), who wishes to preserve the thinly-attested νυκτιδρόμος (Orph. H. 9.2, SB 4127.14), must either, by hypallage, take the genitive with ἰάν or write

μελίβρομον). Pace (in Scritti Gallo, 458–9), who wishes to preserve the thinly-attested νυκτιδρόμος (Orph. H. 9.2, SB 4127.14), must either, by hypallage, take the genitive with ἰάν or write  and in any case achieves much weaker sense in a stanza that deals with the sounds of early dawn (527–64n.). The confusion of

and in any case achieves much weaker sense in a stanza that deals with the sounds of early dawn (527–64n.). The confusion of  and δ is rare, but not unheard of (FJW on A. Suppl. 547, 599, where add particularly HF 1212 δρόμον Reiske: βρόμον L) For

and δ is rare, but not unheard of (FJW on A. Suppl. 547, 599, where add particularly HF 1212 δρόμον Reiske: βρόμον L) For  and its cognates in the context of music see also Pi. Nem. 11.7

and its cognates in the context of music see also Pi. Nem. 11.7  δέ

δέ  βρέμεται καὶ ἀοιδά, S. fr. 314.284 (Ichneutai)

βρέμεται καὶ ἀοιδά, S. fr. 314.284 (Ichneutai)

, Ba. 160–1, Pae. Delph. 1.12 (CA 85 = Furley–Bremer II 85), h.Merc. 452 ἱμερόεις βρόμος

, Ba. 160–1, Pae. Delph. 1.12 (CA 85 = Furley–Bremer II 85), h.Merc. 452 ἱμερόεις βρόμος  and S. fr. 513 (Poimenes).

and S. fr. 513 (Poimenes).

By the later fifth century both σῦριγξ and  could be used to denote the ‘multiple-stem’ panpipe (West, Ancient Greek Music, 109–10 with n. 122). Willink’s assertion that at Or. 145–6 ἆ ἆ σύριγγος

could be used to denote the ‘multiple-stem’ panpipe (West, Ancient Greek Music, 109–10 with n. 122). Willink’s assertion that at Or. 145–6 ἆ ἆ σύριγγος  πνοὰ /

πνοὰ /  δόνακος, ὦ ϕίλα,

δόνακος, ὦ ϕίλα,  μοι (and elsewhere in

Euripides) the singular meant a simple reed-pipe, is disproved by PV 574

μοι (and elsewhere in

Euripides) the singular meant a simple reed-pipe, is disproved by PV 574  … δόναξ (‘made with wax’, i.e. held together by it, as the parts of the pan-pipe were).

… δόναξ (‘made with wax’, i.e. held together by it, as the parts of the pan-pipe were).

ἰάν: a rare word. Cf. Pers. 937  ἰάν, Hdt. 1.85.2 (oracle), Hipp. 585 ἰὰν μὲν κλύω,

ἰάν, Hdt. 1.85.2 (oracle), Hipp. 585 ἰὰν μὲν κλύω,  δ᾽ οὐκ ἔχω, where Weil’s emendation of

δ᾽ οὐκ ἔχω, where Weil’s emendation of  Hipp. 585 (II 75.13 Schwartz)

Hipp. 585 (II 75.13 Schwartz)  (ἰαχὰν

(ἰαχὰν  ) was confirmed by P. Oxy. 2224, and OT 1219 ἰὰν

) was confirmed by P. Oxy. 2224, and OT 1219 ἰὰν  Burges:

Burges:  codd. (see L1-J/W, Sophoclea, 108).

codd. (see L1-J/W, Sophoclea, 108).

κατακούω: The compound is found only here in tragedy. But Liapis (on 551–3) notes the contextually similar dialogue in Ar. Ran. 312–13 … (Δι.) οὐ  (Ξα.) τίνος; / (Δι.)

(Ξα.) τίνος; / (Δι.)  πνοῆς.

πνοῆς.

554–6. ‘Sleep casts its spell over the seat of my eyes; for it comes upon their lids most sweetly towards dawn.’

The antistrophe ends with a reminiscence of Pi. Pyth. 9.23–5

ἀῶ. Others also praised the pleasure of early-morning sleep: Alcm. 3 fr. 1.7 PMGF [ὕπνον

ἀῶ. Others also praised the pleasure of early-morning sleep: Alcm. 3 fr. 1.7 PMGF [ὕπνον  γλεϕάρων σκεδ[α]σεῖ

γλεϕάρων σκεδ[α]σεῖ  (apparently), Bacch. Pae. 4.76–8 οὐδὲ

(apparently), Bacch. Pae. 4.76–8 οὐδὲ

/

/

/ ἀῷος ὃς θάλπει κέαρ (ἀῷος Blass: ἆμος vel ἇμος Stob. 4.14.3), Mosch. 2.2–4 (Aphrodite sent Europa a dream) νυκτὸς

/ ἀῷος ὃς θάλπει κέαρ (ἀῷος Blass: ἆμος vel ἇμος Stob. 4.14.3), Mosch. 2.2–4 (Aphrodite sent Europa a dream) νυκτὸς  τρίτατον

τρίτατον  ἵσταται, ἐγγύθι δ᾽ ἠώς, / ὕπνος

ἵσταται, ἐγγύθι δ᾽ ἠώς, / ὕπνος

/

/

429 Luc. Merc.Cond. 24

429 Luc. Merc.Cond. 24

κώδωνι

κώδωνι

On the military realism of our lines see further 527–64n.

On the military realism of our lines see further 527–64n.

θέλγει … / ὕπνος: In Greek literature the concept of sleep as ‘spellbinding’ goes back to Il. 24.343–4 (of Hermes)  δὲ ῥάβδον,

δὲ ῥάβδον,

θέλγει /

θέλγει /  ἐθέλῃ,

ἐθέλῃ,  δ᾽

δ᾽  καὶ

καὶ  ἐγείρει (= Od. 5.47–8 ~ 24.2–4). Note also Or. 211 ὦ

ἐγείρει (= Od. 5.47–8 ~ 24.2–4). Note also Or. 211 ὦ

θέλγητρον, IA 142

θέλγητρον, IA 142

and, of a divinely imposed trance, Il. 13.434–5

and, of a divinely imposed trance, Il. 13.434–5  τόθ᾽

τόθ᾽

/ θέλξας ὄσσε ϕαεινά.

/ θέλξας ὄσσε ϕαεινά.

ὄμματος ἕδραν: By contrast with 8 (n.)

(where ‘the … seat of your lids’ = ‘eyes’), periphrastic ἕδρα has here lost most of its force. The virtual repetition may have been aided by

(where ‘the … seat of your lids’ = ‘eyes’), periphrastic ἕδρα has here lost most of its force. The virtual repetition may have been aided by  in the following line.

in the following line.

βλεϕάροις: Musgrave (on 556). Ω’s  is an epicising slip.

is an epicising slip.

πρὸς ἀῶ: The MSS’  was independently corrected by Blaydes (Adversaria, 7) and Headlam (CR 15 [1901], 102), the latter citing Pi. Pyth. 9.23–5 (above). Cf. further Ar. Eccl. 312

was independently corrected by Blaydes (Adversaria, 7) and Headlam (CR 15 [1901], 102), the latter citing Pi. Pyth. 9.23–5 (above). Cf. further Ar. Eccl. 312  ἕω, Theoc.

18.55 πρὸς ἀῶ and e.g. Ar. Lys. 1089, Eccl. 20

ἕω, Theoc.

18.55 πρὸς ἀῶ and e.g. Ar. Lys. 1089, Eccl. 20  ὄρθρον (LSJ s.v.

ὄρθρον (LSJ s.v.  C II). The genitive is not used in that temporal sense.

C II). The genitive is not used in that temporal sense.

557–64. As in 538–45 (n.), the section is divided between semi-choruses or single choreutae. The MSS run together 557–9, but change of speaker after 558 is indicated by the metrical pause (paroemiac). In 561 L has a paragraphos before  ἂν

ἂν

μοι. If the text is essentially correct, the comment would suit the speaker of 559. But more extensive corruption cannot be ruled out (560–1n.).

μοι. If the text is essentially correct, the comment would suit the speaker of 559. But more extensive corruption cannot be ruled out (560–1n.).

However we assign the utterances, the ‘ephymnium’ 543–5 ~ 562–4 (nn.) belongs to the same group or person.

557–61. While the chorus even verbally recall Hector’s order to watch out for Dolon (cf. 557–8n.), their weariness prevents them from acting on it. Far from being mere characterisation, however, the dialogue will again remind the audience of the spy’s fate and so prepare for the imminent entry of Odysseus and Diomedes (Fantuzzi, in Entretiens Hardt LII, 155).

557–8. The anxious query takes up Hector at 524–6. Its syntax, however, mirrors Il. 10.561–3  τρεισκαιδέκατον

τρεισκαιδέκατον

ἐγγύθι νηῶν, / τόν ῥα

ἐγγύθι νηῶν, / τόν ῥα  στρατοῦ ἔμμεναι

στρατοῦ ἔμμεναι  /

/

καὶ

καὶ  Τρῶες ἀγαυοί, and there are other points of contact with ‘Homer’ and Aeschylus (below).

Τρῶες ἀγαυοί, and there are other points of contact with ‘Homer’ and Aeschylus (below).

τί ποτ᾽᾽ οὐ πελάθει: Given the rarity of  (LSJ s.v.), this may be a reminiscence of A. fr. 132 (Myrmidons) = Ar. Ran. 1264–5 (+ 1267/71/75/77)

(LSJ s.v.), this may be a reminiscence of A. fr. 132 (Myrmidons) = Ar. Ran. 1264–5 (+ 1267/71/75/77)  Ἀχιλλεῦ,

Ἀχιλλεῦ,  ποτ᾽

ποτ᾽  ἀκούων, / ἰή,

ἀκούων, / ἰή,  οὐ

οὐ

ἀρωγάν; inspired either by Frogs or indeed primary acquaintance with Myrmidons (cf. Introduction, 34–5 with n. 53). Nauck’s

ἀρωγάν; inspired either by Frogs or indeed primary acquaintance with Myrmidons (cf. Introduction, 34–5 with n. 53). Nauck’s  (II3 [1871], XXXIV) then probably misses the point. Exact metrical responsion with 538 need not be restored, nor do we require the same verb as at 13–14 (n.). On the contrary,

(II3 [1871], XXXIV) then probably misses the point. Exact metrical responsion with 538 need not be restored, nor do we require the same verb as at 13–14 (n.). On the contrary,  would even be closer in sound to 526 πελάζει.

would even be closer in sound to 526 πελάζει.

σκοπός in the sense ‘spy’ or ‘scout’ is regularly used in Iliad 10 (38, 324, 342, 526, 561), but rare later (LSJ s.v. I 3,430 Pritchett, GSWI, 129). It is combined with  (-τήρ) at Sept. 36–7

(-τήρ) at Sept. 36–7  δὲ κἀγὼ καὶ

δὲ κἀγὼ καὶ  στρατοῦ / ἔπεμψα.

στρατοῦ / ἔπεμψα.

ναῶν / … κατόπτην: 523–5a n. At 133–5a (n.)  γὰρ

γὰρ

νεῶν /

νεῶν /  /

/  (…); the genitive depends on πέλας.

(…); the genitive depends on πέλας.

Wecklein rightly wrote

, which would easily have been ‘doricised’ under the influence of the preceding lyric (cf. 1n.).

, which would easily have been ‘doricised’ under the influence of the preceding lyric (cf. 1n.).

ὤτρυνε: 25n. The double accusative (with ἰέναι to be supplied) is paralleled in Il. 10.37–8 τίϕθ᾽ οὕτως, ἠθεῖε, κορύσσεαι; ἦ τιν᾽  /

ὀτρυνέεις Τρώεσσιν ἔπι σκοπόν; where Nicias’ ἔπι

/

ὀτρυνέεις Τρώεσσιν ἔπι σκοπόν; where Nicias’ ἔπι  (apud Hdn. I 232.16–17, II 69.5–6 Lentz =

(apud Hdn. I 232.16–17, II 69.5–6 Lentz =  II. 10.38 [III 10.9–10 Erbse]) for

II. 10.38 [III 10.9–10 Erbse]) for  or

or  (cf. West’s apparatus) is perhaps supported by

(cf. West’s apparatus) is perhaps supported by  here in 557. Similarly 642–3n. with n. 245.

here in 557. Similarly 642–3n. with n. 245.

559. χρόνιος: Unlike the epic-style adverbial accusative χρόνον (865n.), predicative χρόνιος, ‘for a long time’, is well established in tragedy (LSJ s.v. I 2; especially IA 1098–9

πόσιν, / χρόνιον ἀπόντα).

πόσιν, / χρόνιον ἀπόντα).

560–1. ‘Can he have run into a hidden ambush and perished? †Perhaps so.† I am afraid.’

ἀλλ᾽ ἦ: 36–7a n. Here ἀλλ᾽ ἦ, restored by Matthiae (VIII [1824], 28) for the MSS’ ἀλλ᾽  conveys the speaker’s natural reluctance to accept that Dolon may be dead.

conveys the speaker’s natural reluctance to accept that Dolon may be dead.

λόχον: 17–18n.

ἐσπαίσας (‘burst, rush in’) is rare in drama and elsewhere: OT 1252  γὰρ

γὰρ  Οἰδίπους, Xenarch. fr. 1.3 PCG

Οἰδίπους, Xenarch. fr. 1.3 PCG  τ᾽

τ᾽  Πελοπιδῶν, Ar. Pl. 804–5

Πελοπιδῶν, Ar. Pl. 804–5  γὰρ

γὰρ  σωρὸς εἰς

σωρὸς εἰς

/

/

431 and probably also Or. 1315 στείχει γὰρ

431 and probably also Or. 1315 στείχει γὰρ

(Wecklein cl. Rh. 560:

(Wecklein cl. Rh. 560:  codd:

codd:  432 The aorist and future invited corruption into forms of -πίπτειν. At OT 1252 most MSS read εἰσέπεσεν by phonetic confusion of αι and ε (cf. Dawe, STS I, 257), and in our passage O alone has the nearly correct

432 The aorist and future invited corruption into forms of -πίπτειν. At OT 1252 most MSS read εἰσέπεσεν by phonetic confusion of αι and ε (cf. Dawe, STS I, 257), and in our passage O alone has the nearly correct  (if with

(if with  attached to 559). VaΛ’s

attached to 559). VaΛ’s  will be another intrusive gloss, unless iotacism produced *εἰσπέσας, which someone then ‘improved’ to εἰσπεσών.

will be another intrusive gloss, unless iotacism produced *εἰσπέσας, which someone then ‘improved’ to εἰσπεσών.

ἂν

ἂν

Va)433 is too long by two syllables

Va)433 is too long by two syllables  but no fully satisfactory emendation has yet been made. Most recent editors accept Headlam’s διόλωλε; –

but no fully satisfactory emendation has yet been made. Most recent editors accept Headlam’s διόλωλε; –

μοι (CR 15 [1901], 103), which neatly restores metre and sense. ‘Absolute’

μοι (CR 15 [1901], 103), which neatly restores metre and sense. ‘Absolute’  ἄν in reply has contemporary parallels at Pl. Sph. 255c12 and Rep. 369a8, and could have prompted a scribe or corrector to supply

ἄν in reply has contemporary parallels at Pl. Sph. 255c12 and Rep. 369a8, and could have prompted a scribe or corrector to supply  for ‘clarification’. L’s inner-metric antilabe (16n.) also suits the excited, colloquial tone of the passage and, by approximate responsion with 540–1, leaves 562–4 to the same speaker as 543–5 (cf. 557–64n.). One may object, however, to the

general weakness of

for ‘clarification’. L’s inner-metric antilabe (16n.) also suits the excited, colloquial tone of the passage and, by approximate responsion with 540–1, leaves 562–4 to the same speaker as 543–5 (cf. 557–64n.). One may object, however, to the

general weakness of  So Herwerden (RPh n.s. 18 [1894], 85) wrote

So Herwerden (RPh n.s. 18 [1894], 85) wrote  – in fine tragic idiom (e.g. Ai. 838

– in fine tragic idiom (e.g. Ai. 838  Alc. 391, Hipp. 1350), though perhaps with too much pity for Dolon. Hermann’s

Alc. 391, Hipp. 1350), though perhaps with too much pity for Dolon. Hermann’s  (Opuscula III, 306), expanded by Diggle into

(Opuscula III, 306), expanded by Diggle into

merely transfers the ‘weakness’ to the entire sentence, not to mention the extreme rarity in tragedy of τάχα (‘soon’) with a potential optative (Ai. 1147–9 is a probable example). If, like Diggle, one wishes to give

merely transfers the ‘weakness’ to the entire sentence, not to mention the extreme rarity in tragedy of τάχα (‘soon’) with a potential optative (Ai. 1147–9 is a probable example). If, like Diggle, one wishes to give  a subject, West’s τὸ πᾶν (after PV 126 πᾶν μοι ϕοβερὸν τὸ προσέρπον) might be considered.

a subject, West’s τὸ πᾶν (after PV 126 πᾶν μοι ϕοβερὸν τὸ προσέρπον) might be considered.  was familiar to scholiasts and could have occurred to a scribe here when faced with some illegible letters.

was familiar to scholiasts and could have occurred to a scribe here when faced with some illegible letters.

On the whole, Headlam’s solution remains the best, but as deeper corruption cannot be ruled out, Diggle’s obeli are the appropriate response.

562–4. See 543–5 and 557–64nn. The statement with  reinforces the sentries’ intention to call for relief. As far as the Trojans are concerned, Dolon is forgotten until 863–5.

reinforces the sentries’ intention to call for relief. As far as the Trojans are concerned, Dolon is forgotten until 863–5.

After the sentries have left in the direction of the Trojan camp, the stage remains empty for a short while, before Odysseus and Diomedes enter by the same eisodos. The interval is necessary to avoid the impression that the two parties run into each other, but it also serves the important structural purpose of accentuating the dramatic turning point (Liapis, xxxvii-xxxviii and on 565–674). A technical parallel exists in Alc. 860, where Heracles, on his way to bring Alcestis back to life, must not meet Admetus and presumably the chorus (cf. below) returning from her funeral, and a brief gap in the action is much more likely than that Heracles simply exits ‘on the ‘wrong’ side; and probably no one in the audience noticed the incongruity’ (Taplin, Stagecraft, 385 n. 2).

The temporary departure of the chorus in mid-play (called μετάστασις by Poll. 4.108) is rare, but not unprecedented in fifth-century tragedy. In Eum. 231–43, the earliest surviving example,434 it helps to indicate the change of scene and, more importantly, visualises the Erinyes’ continuous pursuit on the Atridae’s ancient trail of blood (Taplin, Stagecraft, 380–1). Later, as here, the device mainly enables the playwright to put on a scene that could not be enacted in front of the chorus: Ai. 815–65 (Ajax’ suicide),435 Alc. 747–860 (Heracles’ decision to save Alcestis)436 and Hel. 386–514 (Menelaus’ first entry and conversation with Theoclymenus’ doorkeeper).437 Rhesus, however, is unique both formally and with regard to the plot in that the chorus depart after the equivalent of an act-dividing song (Taplin, Stagecraft, 376) and that their behaviour –all the worse for being in defiance of Hector’s order at 523–5 – actually helps the enemy ruse (Burnett, ‘Smiles’, 36, G. Paduano, Dioniso 55 [1984–85], 267).

565–94. Onto the vacated stage sneak Odysseus and Diomedes, with the novel (and doomed) intention of killing Hector in his bed (574–6, 580–1 – probably suggested by Il. 10.406–8 + 414–16, where Odysseus asks after, and Dolon betrays, Hector’s location).438 When they cannot find the Trojan commander, a brief discussion about the reasons (577–9) and their strategic options (580–93) ends with the decision to return to the ships (594).

The entry of two characters talking is rare in classical drama: Phil. 730, IT 67 (below), E. fr. 62a.5 and, in ‘mid-conversation’, Phil. 1222, Hipp. 601, IA 303, Ar. Nub. 1214, Av. 801, Lys. 1, Ran. 830 (O. P. Taplin, GRBS 12 [1971], 40, Stagecraft, 363–4; cf. Liapis on 565 ff.). The dialogue of the Greeks here at once reveals their uncharacteristic timidity (565–9 [568b–9n.], 577–8), as well as the more traditional contrast (exemplified by e.g. Il. 10. 383–4 + 446–57, 502–6) between Diomedes’ warlike impetuosity and the calmer prudence of his companion (cf. 582–94, 582–4, 589–90nn.). Yet as with the advice Aeneas and the chorus give Hector in 85–148 (n.), Odysseus’ apparently wiser plan to retreat is bound for disaster, except that in his case Athena will intervene to share her superior knowledge of Rhesus’ arrival (Strohm 260 n. 4, G. Paduano, SCO 23 [1974], 25–6, Rosivach 61–3; cf. 595–674, 595–641nn.).

The scene amounts to a second prologue (Fantuzzi, Entretiens Hardt LII, 156–9). A series of relevant echoes (discussed in the commentary) suggests that it was modelled on a combination of Orestes’ and Pylades’ cautious entry in IT 67–122, the arrival of Odysseus and Neoptolemus on Lemnos (Phil. 1–49) and, to a lesser degree, Polynices’ secret return to Thebes at Phoen. 261–73 + 361–4 (cf. G. Björck, Eranos 55 [1957], 15, Strohm 263 n. 6, Mastronarde on Phoen. 261–442, 269). In addition, the ‘clash of temperaments’ between Odysseus and Diomedes reproduces on a smaller scale heroic motifs from Il. 8.130–58.

565–6. ‘Diomedes, did you not hear – or is there a meaningless noise trickling through my ears? – a din of armour?’

Odysseus’ opening words bear a striking similarity to E. El. 747–8 ϕίλαι,

βροντῆς Διός; (Ritchie 245) as well as, closer to the present situation, Phoen. 269 ὠή, τίς

βροντῆς Διός; (Ritchie 245) as well as, closer to the present situation, Phoen. 269 ὠή, τίς

S. fr. 61 (Acrisius)

S. fr. 61 (Acrisius)

ἀκούετ᾽; ἢ μάτην ὑλῶ; / ἅπαντα γάρ τοι τῷ ϕοβουμένῳ ψοϕεῖ (of which the first line is quoted as a parallel to Phoen. 269–71 in gB) and perhaps S. fr. 314.204 (Ichneutae) οὐ[κ ε]ἰσακο[ύε]ις, ἢ κεκώϕη[σαι, perhaps S. fr. 314.204 (Ichneutae)

ἀκούετ᾽; ἢ μάτην ὑλῶ; / ἅπαντα γάρ τοι τῷ ϕοβουμένῳ ψοϕεῖ (of which the first line is quoted as a parallel to Phoen. 269–71 in gB) and perhaps S. fr. 314.204 (Ichneutae) οὐ[κ ε]ἰσακο[ύε]ις, ἢ κεκώϕη[σαι, perhaps S. fr. 314.204 (Ichneutae)  ψόϕον;] (suppl. Wilamowitz). For the vivid interlace of two independent questions by ‘διὰ μέσου’ parenthesis note also e.g. Cyc. 121

ψόϕον;] (suppl. Wilamowitz). For the vivid interlace of two independent questions by ‘διὰ μέσου’ parenthesis note also e.g. Cyc. 121  δ᾽ –

δ᾽ –  Hipp. 685–6, Hel. 1579–80 and Ba. 649 (KG II 602 n. 5, Diggle, Studies, 115–16, R. Renehan, CPh 87 [1992], 341–2).

Hipp. 685–6, Hel. 1579–80 and Ba. 649 (KG II 602 n. 5, Diggle, Studies, 115–16, R. Renehan, CPh 87 [1992], 341–2).

στάζει δι᾽ ὤτων finds its nearest parallel in Pi. Pyth. 4.136–8  δ᾽

δ᾽

(with Braswell on 136–7). The image of sound as a liquid also lies behind OT 1386–7

(with Braswell on 136–7). The image of sound as a liquid also lies behind OT 1386–7  δι᾽

δι᾽  ϕραγμός, Ar. Thesm. 18

ϕραγμός, Ar. Thesm. 18  (‘funnel’)

(‘funnel’)  διετετρήνατο, Pl. Phdr. 235c8–d1 and Rep. 411a5–8.

διετετρήνατο, Pl. Phdr. 235c8–d1 and Rep. 411a5–8.

Metaphorical  in tragedy is largely confined to lyrics: Ag. 179–80 στάζει δ᾽ …

in tragedy is largely confined to lyrics: Ag. 179–80 στάζει δ᾽ …  καρδίας / μνησιπήμων

καρδίας / μνησιπήμων  (with Fraenkel on 179), Ant. 959–60

(with Fraenkel on 179), Ant. 959–60  τε μένος, Hipp. 525–6 Ἔρως, Ἔρως, ὁ κατ᾽

τε μένος, Hipp. 525–6 Ἔρως, Ἔρως, ὁ κατ᾽  / στάζων

/ στάζων  (with Barrett); in iambic trimeters cf. S. fr. 373.2–3 (of Aeneas)

(with Barrett); in iambic trimeters cf. S. fr. 373.2–3 (of Aeneas)

For δι᾽

For δι᾽  see 294–5n.

see 294–5n.

567–8a. ‘No, it is harnesses, which hang from the rails of the horse-drawn chariots, sounding their clang of iron.’

For the practice of fastening one’s unyoked horses to the chariot for the night see 27 and 616–17nn. In the permanent Greek camp, where no precautions for an emergency sortie are required, the captured team of Rhesus will be bound to the manger near Diomedes’ hut (Il. 10.566–9).

πωλικῶν ἐξ ἀντύγων recalls Ai. 1030 (Hector) … πρισθεὶς ἱππικῶν  ἀντύγων, from the most likely interpolated end of Teucer’s first speech (see Finglass on Ai. [1028–39]), except that

ἀντύγων, from the most likely interpolated end of Teucer’s first speech (see Finglass on Ai. [1028–39]), except that  here is a genuine plural. Following Il. 5.262 (= 322)

here is a genuine plural. Following Il. 5.262 (= 322)  ἄντυγος

ἄντυγος  τείνας and Il. 10.474–5 ~ Rh. 616–17 (n.), the phrase goes attributively with

τείνας and Il. 10.474–5 ~ Rh. 616–17 (n.), the phrase goes attributively with  in a manner comparable to e.g. Pers. 611 βοός τ᾽

in a manner comparable to e.g. Pers. 611 βοός τ᾽  ἁγνῆς

ἁγνῆς

E. El. 794

E. El. 794  καθαροῖς

καθαροῖς  and IT 162 παγάς τ᾽ οὐρειᾶν ἐκ μόσχων. Cf. Diggle, Studies, 28–9, 69 (where the governing nouns are verbal abstracts), Willink on Or. 982–4

and IT 162 παγάς τ᾽ οὐρειᾶν ἐκ μόσχων. Cf. Diggle, Studies, 28–9, 69 (where the governing nouns are verbal abstracts), Willink on Or. 982–4  and 829–32n.

and 829–32n.

The form of the  is discussed in 372b–3a n.

is discussed in 372b–3a n.

Cf. Sept. 385–6 ὑπ᾽ ἀσπίδος δὲ τῷ / χαλκήλατοι κλάζουσι

Cf. Sept. 385–6 ὑπ᾽ ἀσπίδος δὲ τῷ / χαλκήλατοι κλάζουσι  (LSJ s.v. κλάζω 3, KG I 309, SD 76–7), which in different ways also seems to have inspired Rh. 306b–8 and 383–4 (nn.).

(LSJ s.v. κλάζω 3, KG I 309, SD 76–7), which in different ways also seems to have inspired Rh. 306b–8 and 383–4 (nn.).

σίδηρον is Bothe’s (5 [1803], 296) and Paley’s (on 568) simple correction of the MSS’ σιδήρου. As a verb of sounding,  can hardly take a genitive on the analogy of ὄζω, πνέω and the like (KG I 356–7, SD 128–9), and other analyses (cf. Liapis, ‘Notes’, 82) do not appeal either.

can hardly take a genitive on the analogy of ὄζω, πνέω and the like (KG I 356–7, SD 128–9), and other analyses (cf. Liapis, ‘Notes’, 82) do not appeal either.

568b–9. ‘Fear came over me too, before I realised that it was the clatter of horse-trappings.’

Both expression and content resemble Sept. 245  γ᾽ ἱππικῶν

γ᾽ ἱππικῶν  and 249 δέδοικ᾽·

and 249 δέδοικ᾽·  ὀϕέλλεται. The latter supplies the rare

ὀϕέλλεται. The latter supplies the rare  (LSJ s.v. with Suppl. [1996], where add E. fr. 631.1–2), while δέδοικ᾽ may be echoed in ἔδυ

(LSJ s.v. with Suppl. [1996], where add E. fr. 631.1–2), while δέδοικ᾽ may be echoed in ἔδυ  (cf. Sept. 240

(cf. Sept. 240  It is instructive to relate the Greek heroes’ alarm at ultimately harmless enemy noises to that of the shy Theban chorus girls at the arrival of the Argive host (cf. A. Fries, CQ n.s. 60 [2010], 347–8, Introduction, 37).

It is instructive to relate the Greek heroes’ alarm at ultimately harmless enemy noises to that of the shy Theban chorus girls at the arrival of the Argive host (cf. A. Fries, CQ n.s. 60 [2010], 347–8, Introduction, 37).

τοι: ‘Revealing the speaker’s emotional or intellectual state (present or past)’, as often when intensifying a personal pronoun (GP 541–2). Of fear also e.g. Hipp. 433, Or. 544.

πρὶν ᾐσθόμην: For  with the indicative depending on an affirmative sentence in the past see 294–5n.

with the indicative depending on an affirmative sentence in the past see 294–5n.

570–1. This couplet betrays influence from both IT 67–8 (Ορ.) ὅρα,

(Ritchie 245) and Phil. 30–1 (Οδ.) ὅρα

(Ritchie 245) and Phil. 30–1 (Οδ.) ὅρα

of which the latter verse seems in turn to be mirrored in 574 (n.). The dramatic situation in each case is similar (565–94n.).

of which the latter verse seems in turn to be mirrored in 574 (n.). The dramatic situation in each case is similar (565–94n.).

570. Odysseus’ warning acknowledges the situation of Rhesus. In Il. 10.416–20 the Greeks learn from Dolon that there is no regular watch. Cf. Introduction, 39.

κατ᾽ ὄρϕνην: 41–2n.

571. τοι: ‘In response to a command’ (GP 541): ‘I will take care …’ See also 219–22a n.

τιθεὶς πόδα: 280n. The strong sense ‘plant the foot, step’, as opposed to simple ‘walk’, is appropriate to the Achaeans’ careful movements in the dark.

572–3. While the audience will have had visual confirmation of Dolon’s death in the wolf-skin Odysseus is carrying (591–3n.), this is the first explicit hint at his interception. The betrayal of the watchword, in addition to Hector’s position (cf. 565–94n.), is another innovation for the sake of the plot. In 675–91 (n.) it will help the Achaeans escape.

ἢν δ᾿᾿ οὖν ἐγείρῃς; ‘But if you do wake anyone …?’ ‘εἰ δ’ οὖν … is particularly used when a speaker hypothetically grants a supposition which he denies, doubts, or reprobates’ (GP 464–5). The particles after εἰ emphasise the adversative conditional clause (Paley on Ag. 1009 [1042]; cf. Fraenkel on Ag. 676).

σύνθημα: 521–2n.

521–2n. The development of σύμβολον from a physical token of identification to ‘prearranged signal, watchword’ (LSJ s.v. III 4 with Suppl. [1996]) is easy to understand. But the usage is rare and found only here in classical Greek.

521–2n. The development of σύμβολον from a physical token of identification to ‘prearranged signal, watchword’ (LSJ s.v. III 4 with Suppl. [1996]) is easy to understand. But the usage is rare and found only here in classical Greek.

κλυών: 109–10a, 286nn. The knowledge of the watchword stems from ‘one particular communication’ (M. L. West, BICS 31 [1984], 177). So also 858 κοὐδὲν πρὸς αὐτῶν οἶδα  κλυών.

κλυών.

574–9. The Greeks’ arrival at Hector’s bivouac looks like an adaptation of Phil. 26–42, where a cautious rather than fearful Odysseus asks Neoptolemus about Philoctetes’ temporarily deserted cave. More generally, the passage also recalls Orestes and Pylades discussing the layout of Artemis’ precinct in IT 69–76. Cf. 570–1, 574nn.

574–6. With this exchange contrast Odysseus’ confident statement in Il. 10.477–8 οὗτός τοι, Διόμηδες, ἀνήρ, οὗτοι δέ τοι ἵπποι, /  νῶϊν

νῶϊν

574. ‘Oh, I see this bivouac of the enemy here is deserted.’

ἔα: extra metrum. Mostly ἔα ‘expresses the speaker’s surprise [ΣA PV 114  at some novel, often unwelcome, impression on his senses’ (Fraenkel on Ag. 1256–7 [III, p. 580 n. 4]; cf. Page on Med. 1004, Stevens on Andr. 896, CEE 33 n. 81, Collard, ‘Supplement’, 362). Etymologically it is thus likely to be a composite interjection (SD 599–600, Kannicht on Hel. 71), ‘a gasp of astonishment, perhaps representing the sound of a sharp intake of breath’ (Dodds on Ba. 644), rather than a fossilised imperative of ἐάω. As a colloquialism it is much more common in Euripides than in Aeschylus and Sophocles.

at some novel, often unwelcome, impression on his senses’ (Fraenkel on Ag. 1256–7 [III, p. 580 n. 4]; cf. Page on Med. 1004, Stevens on Andr. 896, CEE 33 n. 81, Collard, ‘Supplement’, 362). Etymologically it is thus likely to be a composite interjection (SD 599–600, Kannicht on Hel. 71), ‘a gasp of astonishment, perhaps representing the sound of a sharp intake of breath’ (Dodds on Ba. 644), rather than a fossilised imperative of ἐάω. As a colloquialism it is much more common in Euripides than in Aeschylus and Sophocles.

εὐνὰς ἐρήμους τάσδε πολεμίων ὁρῶ: 1n. With ὁρῶ here supply οὔσας (KG II 66–7). The wording recalls Phil. 31 (Νε.) ὁρῶ

and 34

and 34  ὑπόστεγον; (574–9n.).

ὑπόστεγον; (574–9n.).

575–6. ‘Yet Dolon declared this to be Hector’s bivouac, against whom my sword is drawn.’

καὶ μὴν … γε: 184n.

1n. Add again οὔσας, as in 574 (n.) and on the model of Od. 19.477

1n. Add again οὔσας, as in 574 (n.) and on the model of Od. 19.477  ἔνδον ἔοντα, Alc. 812, 1012–13, Hel. 827, IA 802–3 and Rh. 952–3

ἔνδον ἔοντα, Alc. 812, 1012–13, Hel. 827, IA 802–3 and Rh. 952–3

ἔδει ϕράσαι / Ὀδυσσέως τέχναισι τόνδ᾽ ὀλωλότα. Probably because of the verb’s primary sense ‘show, make known’ (LSJ s.v. I 1), rather than ‘declare, tell’ the accusative and infinitive does not occur before the first century BC.

ἔδει ϕράσαι / Ὀδυσσέως τέχναισι τόνδ᾽ ὀλωλότα. Probably because of the verb’s primary sense ‘show, make known’ (LSJ s.v. I 1), rather than ‘declare, tell’ the accusative and infinitive does not occur before the first century BC.

ἐϕ᾽ ᾧπερ ἔγχος εἵλκυσται τόδε: similarly Il. 1.194 εἵλκετο δ᾽ ἐκ  μέγα ξίϕος … (from the famous passage in which Athena prevents Achilles from killing Agamemnon) and Ant. 1232–3 ξίϕους /

μέγα ξίϕος … (from the famous passage in which Athena prevents Achilles from killing Agamemnon) and Ant. 1232–3 ξίϕους /

Diomedes naturally has his sword at the ready, as Polynices does on his way through Thebes: Phoen. 267–8, 363–4 (cf. 565–94n.).

Diomedes naturally has his sword at the ready, as Polynices does on his way through Thebes: Phoen. 267–8, 363–4 (cf. 565–94n.).

577. ‘Now, what can that mean? The company has not gone off somewhere, has it?’

τί δῆτ᾽ ἂν εἴη; an impatient question (Dale on Hel. 91) with near-formulaic status in later tragedy and comedy: IA 843, Ar. Eccl. 24, 348–9  δῆτ᾽ ἂν εἴη; μῶν ἐπ᾽ ἄριστον γυνή / κέκληκεν αὐτὴν τῶν ϕίλων; Thesm. 847, Pl. 1152. But see also E. Suppl. 558 πῶς

δῆτ᾽ ἂν εἴη; μῶν ἐπ᾽ ἄριστον γυνή / κέκληκεν αὐτὴν τῶν ϕίλων; Thesm. 847, Pl. 1152. But see also E. Suppl. 558 πῶς  (with Collard on 558–63).

(with Collard on 558–63).

in questions is always continuative. The particle largely belongs to lively dialogue and is therefore, apart from Plato, exceedingly rare outside drama (GP 269–70).

μῶν: 17–18n. The question here expresses both alarm and surprise.

λόχος: Hector’s company, as at 26 (n.).

578. Diomedes’ assumption is symptomatic of the role real or imagined treachery plays in our drama (Rosivach 65–7 with n. 35).

μηχανὴν στήσων τινά: Cf. Andr. 995–6 τοία γὰρ

and see 91–2n.

and see 91–2n.  ἑστάναι).

ἑστάναι).

579. θρασὺς … θρασύς: The emphatic placement of a mostly disyllabic word at the beginning and end of an iambic trimeter is Euripidean: Alc. 722  Hcld. 307, Hipp. 327, Ba. 963, E. fr. 414.1 ϕειδώμεθ᾽ ἀνδρῶν εὐγενῶν, ϕειδώμεθα (Nauck, Euripideische Studien II, 184, Ritchie 238).439 Note also Hcld. 225

βλέψον πρὸς αὐτούς,

Hcld. 307, Hipp. 327, Ba. 963, E. fr. 414.1 ϕειδώμεθ᾽ ἀνδρῶν εὐγενῶν, ϕειδώμεθα (Nauck, Euripideische Studien II, 184, Ritchie 238).439 Note also Hcld. 225

βλέψον πρὸς αὐτούς,

and E. fr. 548.1 νοῦν

and E. fr. 548.1 νοῦν  θεᾶσθαι, νοῦν … Sophocles has two comparable instances in frr. 210.46 (lyric) and 753, Aeschylus none.

θεᾶσθαι, νοῦν … Sophocles has two comparable instances in frr. 210.46 (lyric) and 753, Aeschylus none.

γάρ: 484n.

580–1. For the sentiment at this stage of the exploit cf. IT 94–7  δ᾽ ἱστορῶ, /

δ᾽ ἱστορῶ, /  … / τί δρῶμεν; ἀμϕίβληστρα γὰρ τοίχων

… / τί δρῶμεν; ἀμϕίβληστρα γὰρ τοίχων  /

/  (565–94n.).

(565–94n.).

τί δῆτ᾽ …  another type of set question in drama (cf. 577n.). With γάρ in the next sentence explaining why it was asked note also E. El. 967–9 (Ορ.)

another type of set question in drama (cf. 577n.). With γάρ in the next sentence explaining why it was asked note also E. El. 967–9 (Ορ.)  δρῶμεν; μητέρ᾽

δρῶμεν; μητέρ᾽  ϕονεύσομεν; / (Ελ.) … / (Ορ.)

ϕονεύσομεν; / (Ελ.) … / (Ορ.)  and Phoen. 740 τί

and Phoen. 740 τί  (Mastronarde on Phoen. 1615). Otherwise e.g. Cho. 899 Πυλάδη, τί δράσω; (like E. El. 967 at a critical point in the plot), Phil. 757, IT 1188, Ar. Pax 263, Ran. 277.

(Mastronarde on Phoen. 1615). Otherwise e.g. Cho. 899 Πυλάδη, τί δράσω; (like E. El. 967 at a critical point in the plot), Phil. 757, IT 1188, Ar. Pax 263, Ran. 277.

ηὕρομεν: Dindorf (III.2 [1840], 611) for εὕρ- (Ω), since the dramatists apparently never omitted the temporal augment in spoken verse (KB II 18). In our case the frequent scribal error was probably assisted by the post-classical shortening of  in the imperfect, aorist and perfect tenses of verbs beginning with αυ- and ευ- (Threatte I 384–5, II 482–3, 486; cf. Lautensach, Augment, 47–9). Likewise 611 (611–12n.), 614, 762, 763, 769, 779.

in the imperfect, aorist and perfect tenses of verbs beginning with αυ- and ευ- (Threatte I 384–5, II 482–3, 486; cf. Lautensach, Augment, 47–9). Likewise 611 (611–12n.), 614, 762, 763, 769, 779.

ἐν εὐναῖς: 1n.

ἐλπίδων δ᾽ ἡμάρτομεν: so also Med. 498 (plural for singular).

582–94. Despite the very different situation, which perhaps first recalls IT 102–4 (Ορ.)  ἐναυστολήσαμεν. /

ἐναυστολήσαμεν. /  (565–94, 589–90nn.), this part of the dialogue resembles Il. 8.138–56, where after a checking thunderbolt from Zeus Nestor suggests to Diomedes retreat for much the same reason as Odysseus gives here (582–4n.). Diomedes recognises the value of the advice (Il. 8.146), but shrinks from acting on it for fear that Hector may gloat over his apparent cowardice: Il. 8.147–50 ~ Rh. 589–90 (n.). Nestor then reassures him (Il. 8.153–6 ~ Rh. 591–3) and turns the chariot without further ado (Il. 8.157–8). Contrast the express consent of Diomedes in Rh. 594 (n.).

(565–94, 589–90nn.), this part of the dialogue resembles Il. 8.138–56, where after a checking thunderbolt from Zeus Nestor suggests to Diomedes retreat for much the same reason as Odysseus gives here (582–4n.). Diomedes recognises the value of the advice (Il. 8.146), but shrinks from acting on it for fear that Hector may gloat over his apparent cowardice: Il. 8.147–50 ~ Rh. 589–90 (n.). Nestor then reassures him (Il. 8.153–6 ~ Rh. 591–3) and turns the chariot without further ado (Il. 8.157–8). Contrast the express consent of Diomedes in Rh. 594 (n.).

582–4. In addition to IT 102–3 (582–94n.), cf. Nestor at Il. 8.139–44 ‘Τυδείδη, ἄγε δὴ αὖτε  ἔχε

ἔχε  ἵππους.

ἵππους.  τοι ἐκ Διὸς

τοι ἐκ Διὸς  / νῦν

/ νῦν  γὰρ τούτῳ (i.e. Hector)

γὰρ τούτῳ (i.e. Hector)  Ζεὺς κῦδος

Ζεὺς κῦδος

αὖτε καὶ ἡμῖν, αἴ κ᾽ ἐθέλησιν, / δώσει.

αὖτε καὶ ἡμῖν, αἴ κ᾽ ἐθέλησιν, / δώσει.  δέ κεν

δέ κεν  τι Διὸς νόον

τι Διὸς νόον  /

/  μάλ᾽ ἴϕθιμος,

μάλ᾽ ἴϕθιμος,  (582–94n.). The notion that fighting is pointless when a god supports the other side (583–4) also surfaces in Il. 2.111–16, 5.601–6, 9.18–23, 14.69–73, 16.119–21 and 20.97–8 (Fenik, Typical Battle Scenes, 164, 222).

(582–94n.). The notion that fighting is pointless when a god supports the other side (583–4) also surfaces in Il. 2.111–16, 5.601–6, 9.18–23, 14.69–73, 16.119–21 and 20.97–8 (Fenik, Typical Battle Scenes, 164, 222).

ναυστάθμων: 135b–6n. As the word is always plural in Rhesus, Δ’s ναυστάθμων  must be adopted.

must be adopted.

εὐτυχῆ: 52–84, 665–7, 882–4nn.

τύχην: perhaps a wordplay on εὐτυχῆ, rather than just an inevitable repetition.

585–6. The victims here are not chosen at random. Aeneas is the greatest Trojan warrior after Hector (85–148n.), whereas Paris gained obvious notoriety as the instigator of the whole conflict. Both, moreover, appear as characters in the play.

οὔκουν: 161–2a n. A statement (οὐκοῦν Ω) would be out of place here.

ἐπ᾽ Αἰνέαν: For this form of the name, rather than epic Αἰνείας, in tragedy (and Pindar) see 85–6n.

Φρυγῶν: 32n.

μολόντε: Canter’s correction of  is obvious in view of the dual participles at 590, 591, 595, 619 and 784 (784–6n.), which are all found in at least one MS and, except for 595 and 619, sanctioned by metre.

is obvious in view of the dual participles at 590, 591, 595, 619 and 784 (784–6n.), which are all found in at least one MS and, except for 595 and 619, sanctioned by metre.

χρή: Despite Liapis (‘Notes’, 83), there is no choice between  and

and  since Diomedes is not considering what they ought to be doing, but what they should do next. ‘The scribes of our manuscripts, or their exemplars, had a strange tendency to corrupt

since Diomedes is not considering what they ought to be doing, but what they should do next. ‘The scribes of our manuscripts, or their exemplars, had a strange tendency to corrupt  into

into  (Kannicht on Hel. 1405–9).

(Kannicht on Hel. 1405–9).

καρατομεῖν: At Alc. 1118 καὶ δὴ προτείνω, Γοργόν᾽  the present participle is Lobeck’s correction of the impossible καρατόμω(ι) in the MSS and scholia (II 243.15–17 Schwartz). See Dale and Parker on Alc. 1118, Fraenkel, Rev. 235 and, for καρατόμος in Rhesus (and the issue of beheading), 605–6n. The verb recurs in Lyc. 313, but otherwise is uncommon before the first century AD.

the present participle is Lobeck’s correction of the impossible καρατόμω(ι) in the MSS and scholia (II 243.15–17 Schwartz). See Dale and Parker on Alc. 1118, Fraenkel, Rev. 235 and, for καρατόμος in Rhesus (and the issue of beheading), 605–6n. The verb recurs in Lyc. 313, but otherwise is uncommon before the first century AD.

587–8. The first part of Odysseus’ question  looks like an echo of Nestor at Il. 10.82–4

looks like an echo of Nestor at Il. 10.82–4

Similarly Odysseus himself in Il. 10.141–2

Similarly Odysseus himself in Il. 10.141–2

τόσον ἵκει;

τόσον ἵκει;

πῶς οὖν: ‘ Well, how … ?’, with ‘progressive’ οὖν marking a new stage in the sequence of thought (GP 425–6).

ἐν ὄρϕνῃ: 41–2n.

ἀνὰ στρατόν: As a verse-end

ἀνὰ στρατόν: As a verse-end  στρατόν is Euripidean (Hec. 1110, Phoen. 1275, IA 538).

στρατόν is Euripidean (Hec. 1110, Phoen. 1275, IA 538).

τούσδ᾽: The strong deictic ὅδε can be applied to persons not on stage, but ‘vividly present to the speaker’s thought’ (H. Lloyd-Jones, CR n.s. 15 [1965], 242 = Academic Papers I, 398). Cf. Taplin, Stagecraft, 150–2, with Diggle (CR n.s. 29 [1979], 208), who adds that properly then the character(s) in question should have been mentioned before.440

589–90. In contrast to Pylades at IT 104–17 (cf. 582–94n.), who rightfully contradicts Orestes’ proposal to flee with reference to their honour (104, 114–15), Apollo’s oracle (105) and the long journey they have undertaken for it (116–17), Diomedes here displays the same sort of ‘heroic shame over prudent retreat’ as his epic self in Il. 8.146–50 ναὶ δὴ

γέρον, κατὰ μοῖραν ἔειπες, /

γέρον, κατὰ μοῖραν ἔειπες, /  καὶ θυμὸν ἱκάνει· /

καὶ θυμὸν ἱκάνει· /

Τρώεσσ᾽ ἀγορεύων, / ‘Τυδείδης

Τρώεσσ᾽ ἀγορεύων, / ‘Τυδείδης

/

/

τότε μοι χάνοι εὐρεῖα χθών (with Kirk, who compares Hector’s reply to his wife in Il. 6.441–3). Yet in the absence of any understanding for the other’s concern, the couplet here merely helps to emphasise Diomedes’ rashness in Rhesus (565–94n.).

τότε μοι χάνοι εὐρεῖα χθών (with Kirk, who compares Hector’s reply to his wife in Il. 6.441–3). Yet in the absence of any understanding for the other’s concern, the couplet here merely helps to emphasise Diomedes’ rashness in Rhesus (565–94n.).

αἰσχρόν γε μέντοι: likewise Or. 106 αἰσχρόν γε μέντοι

with γε μέντοι ‘introducing an objection in dialogue’ (GP 412). For military

with γε μέντοι ‘introducing an objection in dialogue’ (GP 412). For military  see 102–4, 756–7a nn.

see 102–4, 756–7a nn.

ναῦς ἔπ᾽ Ἀργείων μολεῖν: 149–50n.

πολεμίους νεώτερον: ‘… without having done the enemies any harm’. The closest dramatic parallels are Ba. 362–3 (κἀξαιτώμεθα …) τὸνθεὸν μηδὲννέον / δρᾶν and the paratragic (or perhaps even genuinely tragic) Ar. Eccl. 338 ὃ καὶ δέδοικα

πολεμίους νεώτερον: ‘… without having done the enemies any harm’. The closest dramatic parallels are Ba. 362–3 (κἀξαιτώμεθα …) τὸνθεὸν μηδὲννέον / δρᾶν and the paratragic (or perhaps even genuinely tragic) Ar. Eccl. 338 ὃ καὶ δέδοικα  τι δρᾷ

τι δρᾷ  (cf. Med. 37, Phoen. 155, 263–4). But the euphemism is common in poetry and prose (LSJ s.vv. νέος II 2,

(cf. Med. 37, Phoen. 155, 263–4). But the euphemism is common in poetry and prose (LSJ s.vv. νέος II 2,  II 1, cf. 4n.).

II 1, cf. 4n.).  in this application has almost entirely lost its comparative force (KG II 306–7, SD 184–5).

in this application has almost entirely lost its comparative force (KG II 306–7, SD 184–5).

591–3. Odysseus is prepared to leave it at Dolon’s killing for that night. In terms of stagecraft, we learn from his reply that he is carrying Dolon’s wolf-skin – perhaps worn around his shoulders like Heracles’ lion skin – as a visible token of the deed. In view of 780–8 (780–8, 781–3, 787–8nn.), Ritchie (70, 76–7) and others suppose that he has actually donned it as a disguise, but in that case it would be more difficult to remove the costume unobtrusively before 675 so that the chorus and Hector (863–5) remain unaware of their scout’s death (cf. S. H. Steadman, CR 59 [1945], 6–7, Feickert on 593). The notion of Liapis (on 565 ff.) that Diomedes is wearing the hide rests on the unfounded assumption that he does not reappear with Odysseus in 675–91 (n.) and is also less probable on linguistic grounds (below). The epic Achaeans immediately dedicate the spoils to Athena and place them on a tamarisk to be collected on their return (Il. 10.458–68, 526–30).

πῶς δ᾽  δέδρακας; expressing an obvious objection to the preceding δράσαντε

δέδρακας; expressing an obvious objection to the preceding δράσαντε  (… νεώτερον). Likewise e.g. S. El. 922–3 (Ηλ.) οὐκ οἶσθ᾽ ὅποι

(… νεώτερον). Likewise e.g. S. El. 922–3 (Ηλ.) οὐκ οἶσθ᾽ ὅποι  οὐδ᾽ ὅποι γνώμης ϕέρῃ. / (Χρ.)

οὐδ᾽ ὅποι γνώμης ϕέρῃ. / (Χρ.)  δ᾽ οὐκ ἐγὼ κάτοιδ᾽ ἅ γ᾽ εἶδον ἐμϕανῶς; and Phil. 249–50 (Nauck, Euripideische Studien II, 176, Liapis on 591–3).

δ᾽ οὐκ ἐγὼ κάτοιδ᾽ ἅ γ᾽ εἶδον ἐμϕανῶς; and Phil. 249–50 (Nauck, Euripideische Studien II, 176, Liapis on 591–3).

ναυστάθμων / κατάσκοπον Δόλωνα: 523–5a n.  / … Δόλωνα). For

/ … Δόλωνα). For  see 135b–6n.

see 135b–6n.

τάδε / σκυλεύματ᾽: The use of  (‘this here’) supports Odysseus as the wearer of the wolf-skin. Cf. Diomedes referring to his sword as

(‘this here’) supports Odysseus as the wearer of the wolf-skin. Cf. Diomedes referring to his sword as  … τόδε (576) and the contrast between ‘yours’ and ‘mine’ in Od. 5.343–7 (Ino to Odysseus)

… τόδε (576) and the contrast between ‘yours’ and ‘mine’ in Od. 5.343–7 (Ino to Odysseus)

σχεδίην

σχεδίην

(KG I 641–3, SD 208, 209–10).

(KG I 641–3, SD 208, 209–10).

Whereas σκυλεύω, ‘strip / despoil a slain enemy’, is well attested in classical Greek, the noun (always plural) appears only once in Thucydides (4.44.5) and six times in Euripides (El. 314, Tro. 18, 1207, Ion 1145, Phoen. 857, 1475). On σκῦλον (-α) see 179 and 619–20a nn.

594. Wilamowitz (De Rhesi scholiis, 9 = KS I, 8) was right to attribute the line to Diomedes with VaQPr (no change of speaker marked in OL) and to write πείθεις instead of  since Athena’s question in 595–8 shows that the two Greeks are already on the retreat and must thus have reached an explicit agreement. Comparable cases of this ‘tragoediae consuetudo’ at or near the end of a scene are Rh. 339–41, 663–4 σύ τοί

since Athena’s question in 595–8 shows that the two Greeks are already on the retreat and must thus have reached an explicit agreement. Comparable cases of this ‘tragoediae consuetudo’ at or near the end of a scene are Rh. 339–41, 663–4 σύ τοί  πείθεις, Cho. 781–2

πείθεις, Cho. 781–2

/ γένοιτο δ᾽

/ γένοιτο δ᾽

E. El. 985–7 and IT 118–19 (Ορ.)

E. El. 985–7 and IT 118–19 (Ορ.)  εἶπας, πειστέον·

εἶπας, πειστέον·  χρεών, / ὅποι … (with the same kind of double asyndeton as here, effecting a conclusive matter-of-fact tone).

χρεών, / ὅποι … (with the same kind of double asyndeton as here, effecting a conclusive matter-of-fact tone).

πείθεις: See above. As elsewhere in Rhesus, the verb invites the suspicion that a wrong decision has been made (65–6n.).

Nauck (II1 [1854], XXII, Euripideische Studien II, 175–6), after Vater (on 578), correcting the grammatically and idiomatically dubious MSS variants εὖ δ᾽ εἴη

Nauck (II1 [1854], XXII, Euripideische Studien II, 175–6), after Vater (on 578), correcting the grammatically and idiomatically dubious MSS variants εὖ δ᾽ εἴη  (OΛ, Chr. Pat. 2009, 2038) and εὖ δ᾽ εἴη τύχη (Va). Cf. OT 1080–1

(OΛ, Chr. Pat. 2009, 2038) and εὖ δ᾽ εἴη τύχη (Va). Cf. OT 1080–1  Τύχης … /

Τύχης … /  OC 642

OC 642  Ζεῦ,

Ζεῦ,  1435, Alc. 1004 χαῖρ᾽, ὦ πότνι᾽,

1435, Alc. 1004 χαῖρ᾽, ὦ πότνι᾽,  δὲ δοίης, Andr. 750, Or. 667. On the presumably substantival use of

δὲ δοίης, Andr. 750, Or. 667. On the presumably substantival use of  in εὖ διδόναι and similar phrases see Fraenkel on Ag. 121 τὸ δ᾽

in εὖ διδόναι and similar phrases see Fraenkel on Ag. 121 τὸ δ᾽  νικάτω.

νικάτω.

595–674. This startling central scene comprises two separate strands of action, held together by Athena’s purpose and continuous presence on stage. Introduced as a divinity to check the Achaeans’ retreat and redirect them against Rhesus (of whose arrival they could not have learnt from Dolon), she is soon seen to demonstrate her support by distracting Paris in Aphrodite’s guise (642–67) and, as in Iliad 10, urging the Greeks to escape while they can (668–74n.). The result is an intricate and highly idiosyncratic combination of four themes particularly familiar from Homer: divine epiphany, assistance (both foreshadowed in Iliad 10), transformation and deceit.

Athena’s sudden, unannounced apparition must have surprised the audience as much as the characters on stage. Epiphanies rarely occur in the middle of a play. Our only surviving instance is Iris and Lyssa in HF 815–73,441 a scene that almost like a ‘second prologue’ prepares for the fundamental reversal of Heracles’ fortune. Consequently, the goddesses do not, as Athena here, interact with any of the characters, but merely talk to each other and (implicitly) the chorus, who in 815–21 had fearfully greeted their arrival. In lost tragedies Lyssa, probably on Dionysus’ order (Dodds, Bacchae2, xxx-xxxi), appeared in A. Xantriae (fr. 169) ἐπιθειάζουσα ταῖς Βάκχαις, and in a papyrus fragment attributed to S. Niobe (fr. 441a) Apollo speaks, while Artemis is killing the heroine’s daughters.442 Athena’s outburst in S. Ajax Locrus (fr. 10c) also seems to fit best in an intermediate position.443 The most notorious case, A. Psychostasia (TrGF III, 374–6), must be handled with care, for even if we do not follow Taplin (Stagecraft, 431–3) in totally rejecting the testimonial evidence, there is no proof that Zeus’ weighing of the souls took place in mid-play and not rather during the prologue.444

Like so many tragic deities, Athena most likely appears ‘on high’, stepping into sight on top of the skene; contrast the Muse, who uses the mechane (882–9n.). This is indicated by the suddenness of her entry and departure, which would be much diminished if she just walked up one of the eisodoi (D. J. Mastronarde, Cl. Ant. 9 [1990], 275;445 cf. S. Perris, G&R 59 [2012], 155 n. 23, 160–1). Since, moreover, the two sides at stage level represent the ways to the opposing Greek and Thracian camps, such an arrangement would conflict with the notion that she presumably comes straight down from Olympus (cf. R. S. Bond, AJPh 117 [1996], 269, although he confuses the directions of the camps).

A raised position – more obviously outside the characters’ vision –would also add a physical dimension to Athena’s invisibility, which cannot simply be due to the imaginary darkness. At 608–9 Odysseus identifies her by her voice, as he does in the Ajax prologue, where Athena is ἄποπτος, ‘out of sight’ (15), and we have other reasons for placing her ‘on high’.446 Similarly, at Hipp. 1391–3 (cf. Barrett on 1283) Hippolytus recognises Artemis only by her divine fragrance. In Paris’ case we lack decisive verbal clues as to whether he sees Athena or not, since her self-introduction as Cypris (646) could be interpreted either way. But the poet’s obvious intention of creating a distorted mirror image of the previous scene (642–74n.) and the fact that she cannot possibly change costume on stage clearly point to the latter. Her ‘transformation’ then need not have been more than a modulation of voice and perhaps a few characteristic poses and gestures for the audience’s pleasure.447

Ever since Valckenaer (Diatribe, 111) the prologue of Ajax (1–133) has been identified as the chief model for this scene. Apart from the general situation and various verbal echoes (A. D. Nock, CR 44 [1930], 173–4; cf. 608–10, 608–9a, 609b–10, 637b–9, 642–3, 649–50, 653–4a, 656–60, 668–9nn.), the episodes are almost identical in structure and sometimes comparable in content. Both open with a thirteen-line speech of Athena, which leads into dialogue with Odysseus and in our play also Diomedes (Ai. 1–90, Rh. 595–641). The first part of each conversation (Ai. 1–65, Rh. 595–626) mainly conveys information about the enemy, while the second (Ai. 66–90, Rh. 627–41) prepares for the following deception scenes. During Athena’s exchange with Paris (Rh. 642–67) the Achaeans are naturally absent, but in Ai. 91–117 Odysseus also recedes into the background, ignored by the goddess and invisible to the bewitched Ajax. When her victims have left in reliance on their divine ‘ally’, Athena briefly returns to her protégés (Ai. 118–33, Rh. 668–74), before the choruses (re-)enter in the parodos and epiparodos respectively.

The parallel helps to establish Odysseus’ dominance in the team and special relationship to Athena, which are not yet fully developed in Iliad 10 (609b–10, 668–74nn.). Otherwise comparison merely highlights the substantial differences in dramatic function and spiritual impact between the two scenes. Naturally for a prologue, most explanations given in Ai. 1–65 are aimed at the audience as well as Odysseus, whereas in Rhesus the only thing that is new to all is the hero’s genuine importance for the war (595–641, 600–4nn.). The Athena of Ai. 1–133 is severe and remote, a manifestation of divine power over men, which moves Odysseus to pity his greatest enemy. In our passage she may seem less dignified or even capricious, but the way she controls friend and foe alike goes far beyond Ajax and all else we know from epic and fifth-century tragedy (Strohm 260–1, 262–3; cf. e.g. Fenik, Iliad X, 23–4).

595–641. In bringing the story back to Iliad 10, Athena formally resembles the ‘complete-reversal dei ex machina’ of Philoctetes and Orestes, who intervene at the last possible minute to prevent an outcome that would be contrary to the mythical tradition (cf. Willink, Orestes, xxix–xxx). Neoptolemus and Philoctetes especially would have departed for the wrong destination, had not Heracles reminded them of Zeus’ purposes. But while in these plays the aberration comes from the human characters’ disposition and their failure or unwillingness to perceive the truth (A. Spira, Untersuchungen zum Deus ex machina bei Sophokles und Euripides, Kallmünz 1960, 144–5, 157), Odysseus and Diomedes here lack factual knowledge, which (as the plot is conceived) can only be supplied by a god.