οὐ μὲν οὖν: Reiske (Animadversiones, 90) for the transmitted οὐ μενῶ. In this juncture οὖν emphasises adversative μέν (GP 475).

ἆ: here an expression of protest (‘Stop!’), followed by a prohibition, as in OT 1147 ἆ,  κόλαζε, πρέσβυ, τόνδ’, Phil. 1300, Alc. 526, Hipp. 503 (with Barrett on 503–4), Hel. 445 (with Kannicht) and Ar. Pl. 127, 1052. It is often doubled, which may have given rise to the MSS error, corrected by Musgrave (on 689). For further details see 747–9n.

κόλαζε, πρέσβυ, τόνδ’, Phil. 1300, Alc. 526, Hipp. 503 (with Barrett on 503–4), Hel. 445 (with Kannicht) and Ar. Pl. 127, 1052. It is often doubled, which may have given rise to the MSS error, corrected by Musgrave (on 689). For further details see 747–9n.

ϕίλιον ἄνδρα: On  , ‘friendly’, as opposed to ‘(of an) enemy’, see 11n. ΣV Rh. 683 (II 342.10–11 Schwartz = 108 Merro) notes Ὀδυσσεὺς

, ‘friendly’, as opposed to ‘(of an) enemy’, see 11n. ΣV Rh. 683 (II 342.10–11 Schwartz = 108 Merro) notes Ὀδυσσεὺς  εἶναι Τρωϊκός.

εἶναι Τρωϊκός.

688. καὶ …  in questions usually expresses surprise (GP 211). Here it is rather indignation or impatience: ‘Well, and what is the watchword? ’

in questions usually expresses surprise (GP 211). Here it is rather indignation or impatience: ‘Well, and what is the watchword? ’

σῆμα: 12, 521–2nn.

Φοῖβος: 521–2n.

ἴσχε πᾶς δόρυ: 680, 687nn.

689–91. Odysseus’ last trick formally reverses the more typical misdirection of a character by the chorus-leader: Cyc. 675–88 (below), IT 1293–1301, Ar. Thesm. 1217–26.

689. The situation and wording most closely resemble Cyc. 684–5 (Χο.) καί  γε. / (Κυ.)

γε. / (Κυ.)  πῃ,

πῃ,  ; (Χο.)

; (Χο.)

λέγω (cf. Seaford on 685). It makes little difference which semi-chorus speaks οἶσθ᾽

λέγω (cf. Seaford on 685). It makes little difference which semi-chorus speaks οἶσθ᾽  βεβᾶσιν ἅνδρες;

βεβᾶσιν ἅνδρες;

ὅπῃ, ‘which way’ (S. fr. 314.166–7 [Ichneutae] εἰ μὴ … ἐξιχνεύσε[τε] /  βοῦς ὅπῃ βεβᾶσι …, Ar. Ach. 198, Ai. 867–8 πᾷ πᾷ / πᾷ γὰρ οὐκ ἔβαν ἐγώ;), is favoured by the MSS and seems both more relevant and a better preparation for

βοῦς ὅπῃ βεβᾶσι …, Ar. Ach. 198, Ai. 867–8 πᾷ πᾷ / πᾷ γὰρ οὐκ ἔβαν ἐγώ;), is favoured by the MSS and seems both more relevant and a better preparation for  than

than  (Aldina, ὅπο P vel Pc), ‘to what destination’. The two words tend to be confused.

(Aldina, ὅπο P vel Pc), ‘to what destination’. The two words tend to be confused.

690–1. Leaving this couplet to a single speaker (with Λ) avoids having an opposition pending at the end of the scene.  in 691 then becomes ‘self-correcting’ (GP 7–8).

in 691 then becomes ‘self-correcting’ (GP 7–8).

690. ἕρπε πᾶς: 680, 687nn.

βοὴν ἐγερτέον; Cf. Or. 1353–5 ἰὼ ἰὼ ϕίλαι, /

βοὴν ἐγερτέον; Cf. Or. 1353–5 ἰὼ ἰὼ ϕίλαι, /  ἐγείρετε,

ἐγείρετε,  καὶ

καὶ  /

/  μελάθρων,

μελάθρων,  ὁ πραχθεὶς ϕόνος / μὴ

ὁ πραχθεὶς ϕόνος / μὴ

ϕόβον, where the final clause shares two further words with Rh. 691 (below). The

ϕόβον, where the final clause shares two further words with Rh. 691 (below). The  is a ‘formal cry for help … which a person in distress must utter if he is to merit assistance’ (Diggle, Euripidea, 480 with n. 178).

is a ‘formal cry for help … which a person in distress must utter if he is to merit assistance’ (Diggle, Euripidea, 480 with n. 178).

691. At Il. 10.420–1 the allies are also said to be asleep. Here the coryphaeus probably fears that waking them might cause a nocturnal panic (15, 17–18, 36–7a nn.), which is difficult to suppress and hence dangerous (δεινόν).

… ταράσσειν δεινὸν ἐκ νυκτῶν ϕόβῳ: In addition to the possible echo of Or. 1354–5 (690n.), the formulation may have been influenced by Cho. 288–9 καὶ

… ταράσσειν δεινὸν ἐκ νυκτῶν ϕόβῳ: In addition to the possible echo of Or. 1354–5 (690n.), the formulation may have been influenced by Cho. 288–9 καὶ  καὶ μάταιος ἐκ

καὶ μάταιος ἐκ  / κινεῖ, ταράσσει. For ἐκ νυκτῶν, ‘at night’, see 13–14n.

/ κινεῖ, ταράσσει. For ἐκ νυκτῶν, ‘at night’, see 13–14n.

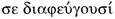

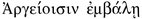

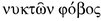

692–727. After the Greeks’ narrow escape the chorus eagerly follow the ‘new’ track (689–90) in pursuit of their elusive quarry. Baffled at first as to the identity of the bold intruder (692–703), they soon settle on Odysseus as a likely candidate (704–9) and, in the antistrophe, underpin this claim with their recollection of his spying expedition to Troy (710–21). Yet certainty is neither attainable nor practically relevant for these sentries so that in 722–7 they merely conclude with an anticipation of Hector’s wrath (808–19n.).

With its recitative-style choral epirrhemata this epiparodos proper structurally resembles Rh. 527–64 and Alc. 86–111 (the centre part of the parodos), where only the anapaestic tail-pieces do not correspond in length and changes of speaker (cf. 527–64n.). Among the tragic ‘search-scenes’ (675–91n.), one may also compare the ode and semi-lyric lamentation-amoibaia between the chorus and Tecmessa in Ai. 879–90 + 891–914 ~ 925–36 + 936–60 (Ritchie 295). This likewise starts with excited τίς-questions in the strophe (Ai. 879–87 ~ Rh. 692–6) and gains support as a possible source from the echoes of the Ajax prologue in 595–674 (n.).

Metre

692–703 ~ 710–21. Iambo-dochmiac. As in e.g. Sept. 98–107 (100, 103, 106), Alc. 213–25 ~ 226–37 (221 ~ 233) and HF 875–921 (880, 894, 905), there seems to be no emotional difference between the regular lyrics and the iambic trimeters (with Attic vocalisation) in 697 ~ 715 and 701 ~ 719 (cf. Bond on HF 875–921, Willink, ‘Cantica’, 41 = Collected Papers, 579). Still their mode of delivery is debated, and some have seen them closer to spoken verse (especially Dale, LM2 207–8; more reserved Fraenkel, Agamemnon III, p. 539, Denniston–Page on Ag. 1072–1330 [p. 165], Barrett, Collected Papers, 388, 390, 392–3).

704–9 ~ 722–7. Iambic trimeters enclosing bacchiacs / syncopated iambics. In contrast to the irregular anapaests at 538–45 + 557–64 (nn.), the distribution of speakers here responds exactly, although their respective number (three at least in 704–9, two in 722–7) cannot be firmly established (cf. Liapis on 704–9, 704–5, 722–7, who improbably follows Paley and Wilamowitz in dividing 704–5 and 722–3 between two choreutae).

Notes

699–700/717–18 The single choriamb preceding two dochmiacs is noteworthy. A partial parallel exists in Hipp. 1275 (δ | cho). See Barrett on Hipp. 1268–82 (pp. 392–3).

706–8/724–6 For such bacchiacs, sharply divided by rhetorical pause or even change of speaker, cf. Sept. 104  ῥέξεις; προδώσεις, παλαίχθων, Eum. 788–90, Or. 173 (Χο.) ὑπνώσσει. (Ηλ.)

ῥέξεις; προδώσεις, παλαίχθων, Eum. 788–90, Or. 173 (Χο.) ὑπνώσσει. (Ηλ.)  ~ 194 (Χο.) δίκαι μέν. (Ηλ.)

~ 194 (Χο.) δίκαι μέν. (Ηλ.)  δ᾽ οὔ, Ba. 1177, 1181–2 ~ 1193, 1197–8 (West, Studies, 46 n. 49 ~ BICS 30 (1983), 70, Parker, Songs, 449).

δ᾽ οὔ, Ba. 1177, 1181–2 ~ 1193, 1197–8 (West, Studies, 46 n. 49 ~ BICS 30 (1983), 70, Parker, Songs, 449).

692. τίς ἀνδρῶν ὁ βάς; The ‘periphrasis’ with a substantival predicative participle (KG I 592 n. 4, 594, G. Björck, ΗΝ ΔΙΔΑΣΚΩΝ. Die peri-phrastischen Konstruktionen im Griechischen, Uppsala 1940, 90–1, W. J. Aerts, Periphrastica …, Amsterdam 1965, 21–2, 41–2) is almost as widespread in drama as it is elsewhere. Cf. Pers. 95–6, Ag. 1506, Ant. 248 τίς  ὁ τολμήσας τάδε; Alc. 530

ὁ τολμήσας τάδε; Alc. 530  ὁ κατθανών; Hipp. 449 (FJW on A. Suppl. 571–2 with further examples) and in comedy e.g. Ar. Nub. 133

ὁ κατθανών; Hipp. 449 (FJW on A. Suppl. 571–2 with further examples) and in comedy e.g. Ar. Nub. 133  ἐσθ᾽ ὁ κόψας τὴν θύραν;

ἐσθ᾽ ὁ κόψας τὴν θύραν;

693–4. ‘Who is this mightily bold fellow, who will boast of having escaped my grasp?’

Sense and syntax are restored by Madvig’s θρασύς (Adversaria critica I, 271) for θράσος (Ω).  then governs the participle instead of an impossible accusative object, and there is no need to interpret ὁ as the relative pronoun ὅ, which in the masculine singular is already rare in Homer and probably unparalleled in tragedy (KG I 587–8, Barrett on Hipp. 525–6).

then governs the participle instead of an impossible accusative object, and there is no need to interpret ὁ as the relative pronoun ὅ, which in the masculine singular is already rare in Homer and probably unparalleled in tragedy (KG I 587–8, Barrett on Hipp. 525–6).

For the form of the question cf. Il. 1.552  ἔειπες; Phil. 601 τίς ὁ

ἔειπες; Phil. 601 τίς ὁ  αὐτοὺς ἵκετ᾽; and OC 205

αὐτοὺς ἵκετ᾽; and OC 205  ὁ

ὁ  ἄγῃ; (KG I 626 n. 1, LSJ s.v. τις, τι B I 2). As in the preceding line, the article indicates familiarity with the subject.

ἄγῃ; (KG I 626 n. 1, LSJ s.v. τις, τι B I 2). As in the preceding line, the article indicates familiarity with the subject.

μέγα θρασύς: Adverbial μέγα for μάλα intensifying an adjective goes back to epic (on a possible origin see Leumann, Homerische Wörter, 119–20). It is almost completely absent from choral lyric (FJW on A. Suppl. 141 = 151), but regularly appears in tragedy (e.g. A. Suppl. 141, PV 647, OT 1343, Alc. 742) and some (mock-)elevated comic passages (Ar. Nub. 291, Cratin. fr. 360.1 PCG, fr. com. adesp. 1110.8 PCG).

ἐπεύξεται / … ϕυγών: The only other instance of ἐπεύχομαι, ‘boast’, with a predicative participle (cf. KG II 72 n. 2, SD 394) is Pl. Sph. 235c5–7  οὗτος

οὗτος  γένος

γένος  ἐπεύξηται

ἐπεύξηται  δυναμένων

δυναμένων  καθ᾽

καθ᾽  τε καὶ

τε καὶ  πάντα μέθοδον. In Homer the verb normally follows a personal military triumph (A. Corlu, Recherches sur les mots relatifs à l’idée de prière: d’Homère aux tragiques, Paris 1966, 133–4), whereas later all sorts of reasons may be supplied (h.Ven. 48, 286–7, Ag. 1262, 1394, 1474, Eum. 58, IT 508, Rh. 703). It is a nice touch of irony that the actual intruders have just escaped a second time – and with more to boast of than having entered the camp unseen.

πάντα μέθοδον. In Homer the verb normally follows a personal military triumph (A. Corlu, Recherches sur les mots relatifs à l’idée de prière: d’Homère aux tragiques, Paris 1966, 133–4), whereas later all sorts of reasons may be supplied (h.Ven. 48, 286–7, Ag. 1262, 1394, 1474, Eum. 58, IT 508, Rh. 703). It is a nice touch of irony that the actual intruders have just escaped a second time – and with more to boast of than having entered the camp unseen.

χέρα … ἐμάν: so Hn and Musgrave (on 696). χεῖρα (Ω) would produce an equally correct dochmiac in responsion with 712, but corruption into the prose form is more likely than the reverse. At 887 Valckenaer’s  for χεροῖν (Diatribe, 116) is metrically necessary.

for χεροῖν (Diatribe, 116) is metrically necessary.

695. πόθεν νιν κυρήσω; literally ‘Starting from what point shall I find him?’. On this use of  , where we would expect ποῦ, see 611–12n.

, where we would expect ποῦ, see 611–12n.

696–8. τίνι προσεικάσω: ‘To whom shall I compare him …?’, i.e. ‘Who can he possibly be, who …?’.  (‘compare, liken, refer to’) here gets a sense of equation, as in Sept. 430–1

(‘compare, liken, refer to’) here gets a sense of equation, as in Sept. 430–1  δ᾽

δ᾽  τε καὶ κεραυνίους βολάς /

τε καὶ κεραυνίους βολάς /  προσῄκασεν, Ag. 1131 κακῷ

προσῄκασεν, Ag. 1131 κακῷ  and also Hel. 68–70

and also Hel. 68–70  τῶνδ᾽

τῶνδ᾽

ἔχει κράτος; /

ἔχει κράτος; /  γὰρ οἶκος ἄξιος

γὰρ οἶκος ἄξιος  /

/  θ᾽ ἕδραι. See P. M. Smith, On the Hymn to Zeus in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, Chico 1980, 8–12, 79–91, who claims that ‘identification by comparison’ underlies nearly all uses of the verb.

θ᾽ ἕδραι. See P. M. Smith, On the Hymn to Zeus in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, Chico 1980, 8–12, 79–91, who claims that ‘identification by comparison’ underlies nearly all uses of the verb.

In a way analogous to Cho. 12–15 ποίᾳ  προσεικάσω; (‘To what misfortune shall I refer them?’) /

προσεικάσω; (‘To what misfortune shall I refer them?’) /  δόμοισι

δόμοισι  νέον, /

νέον, /  τὠμῷ τάσδ᾽ ἐπεικάσας

τὠμῷ τάσδ᾽ ἐπεικάσας  / χοὰς ϕερούσαις νερτέροις μειλίγματα; the chorus’ question prepares for their own suggestions at 699–701 and 704.

/ χοὰς ϕερούσαις νερτέροις μειλίγματα; the chorus’ question prepares for their own suggestions at 699–701 and 704.

δι᾽ ὄρϕνης: 41–2n. The local force of  , ‘through (and out of) the dark’, is a remnant of the ancient view, found in many languages, that night and darkness were substances, which could cover or occupy a space (R. Dyer, Glotta 52 [1974], 31–6). Similarly 773–4 (774n.)

, ‘through (and out of) the dark’, is a remnant of the ancient view, found in many languages, that night and darkness were substances, which could cover or occupy a space (R. Dyer, Glotta 52 [1974], 31–6). Similarly 773–4 (774n.)  δὲ

δὲ  στρατόν /

στρατόν /  δι᾽ ὄρϕνης.

δι᾽ ὄρϕνης.

ἀδειμάντῳ ποδί: a frequent tragic enallage, ‘whereby the feet of moving persons are assigned qualities properly pertaining to their owners’ (Liapis on 696–8, who quotes e.g. Ag. 907  σὸν

σὸν  …

…  πορθήτορα, Ant. 1144

πορθήτορα, Ant. 1144  and Alc. 611–12 καὶ

and Alc. 611–12 καὶ  ὁρῷ σὸν

ὁρῷ σὸν  γεραιῷ ποδί / στείχοντ᾽). Apparently a highly poetic word,

γεραιῷ ποδί / στείχοντ᾽). Apparently a highly poetic word,  occurs only four times before Rhesus (Pi. Nem. 10.17, Isthm. 1.12, Pers. 162, Cho. 771) and very rarely in later Greek (e.g. Nonn. D. 22.35

occurs only four times before Rhesus (Pi. Nem. 10.17, Isthm. 1.12, Pers. 162, Cho. 771) and very rarely in later Greek (e.g. Nonn. D. 22.35  ἀδειμάντοισι).

ἀδειμάντοισι).

διά τε τάξεων: 519–20n.

699–701. Ritchie (246–7) notes certain syntactical and phraseological affinities with Tro. 187–9 τίς μ᾽  νησαίαν

νησαίαν

/ δύστανον πόρσω Τροίας; and 241–2 αἰαῖ,

/ δύστανον πόρσω Τροίας; and 241–2 αἰαῖ,

χθονός; See also the elaborate chain of queries in Hec. 447–74.

χθονός; See also the elaborate chain of queries in Hec. 447–74.

Besides evoking three major Greek heroes (Achilles from Phthia / Thessaly, Ajax Locrus and the islander Odysseus) the chorus’ suspicions reflect fifth-century and later Athenian ideas of who could be credited with a bold and treacherous night-raid (699–700, 701nn; cf. Ammendola on 699–701, Porter on 701).

699–700. Θεσσαλός: The Thessalians were proverbially untrustworthy (Σrecc. Ar. Pl. 521g [III 4b.141 Chantry] ‘αἰεὶ  ἄπιστα’; cf. E. fr. 422, Dem. 1.21–2, 23.112 and, on the political incidents that inspired this belief, H.-J. Gehrke, Stasis …, Munich 1985, 185–9). Aristophanes (Pl. 520–1) accuses them, perhaps not unreasonably (Sommerstein on 521, 524), of habitual ἀνδραποδισμός, the kidnapping and selling of free persons or other people’s slaves.

ἄπιστα’; cf. E. fr. 422, Dem. 1.21–2, 23.112 and, on the political incidents that inspired this belief, H.-J. Gehrke, Stasis …, Munich 1985, 185–9). Aristophanes (Pl. 520–1) accuses them, perhaps not unreasonably (Sommerstein on 521, 524), of habitual ἀνδραποδισμός, the kidnapping and selling of free persons or other people’s slaves.

παραλίαν Λοκρῶν νεμόμενος πόλιν: Both East and West Locrians had a long-standing reputation for banditry (Thuc. 1.5.3, Hell. Oxy. 21.3 Chambers) and piracy (Thuc. 2.32.2; cf. Thuc. 2.26.1, D. S. 12.44.1), which in antiquity included seaborne attacks on coastal settlements (P. de Souza, Piracy in the Graeco-Roman World, Cambridge 1999, 1–42). On  see 475–6n.

see 475–6n.

701.  σποράδα κέκτηται βίον; Cf. Hcld. 84

σποράδα κέκτηται βίον; Cf. Hcld. 84  νησιώτην, ὦ ξένοι, τρίβω

νησιώτην, ὦ ξένοι, τρίβω  (Iolaus’ reply to the chorus’ questions on his homeland) and for adjectival

(Iolaus’ reply to the chorus’ questions on his homeland) and for adjectival  e.g. Pi. Pyth. 9.54–5 λαὸν … νασιώταν, Pers. 390

e.g. Pi. Pyth. 9.54–5 λαὸν … νασιώταν, Pers. 390  πέτρας, Tr. 658

πέτρας, Tr. 658  ἑστίαν. Of the tragedians Euripides especially liked to use nouns as attributes (KG I 272–3); in

ἑστίαν. Of the tragedians Euripides especially liked to use nouns as attributes (KG I 272–3); in  also Hcld. 699

also Hcld. 699  κόσμον, 800, El. 443

κόσμον, 800, El. 443

(with Denniston on 443–4) and Ion 1373

(with Denniston on 443–4) and Ion 1373  βίον. Likewise Rh. 715 (715–16n.)

βίον. Likewise Rh. 715 (715–16n.)  τις λάτρις.

τις λάτρις.

suggests an isolated, backward life (especially Arist. Pol. 1252b23–4  καὶ

καὶ  ᾤκουν), whether or not the islands themselves were meant to be ‘scattered through the Aegean’ (Porter on 701; cf. Pi. Pae. 5.38–40 [fr. 52e Sn.–M. = D5 Rutherford]

ᾤκουν), whether or not the islands themselves were meant to be ‘scattered through the Aegean’ (Porter on 701; cf. Pi. Pae. 5.38–40 [fr. 52e Sn.–M. = D5 Rutherford]

ϕερεμήλους / ἔκτισαν νάσους ἐρικυδέα

ϕερεμήλους / ἔκτισαν νάσους ἐρικυδέα  ἔσχον /

ἔσχον /  ).476 Islanders often suffered contempt from the mainland Greeks: e.g. Sol. fr. 2 IEG, Hcld. 84 (above), Andr. 14–15 τῷ νησιώτῃ Νεοπτολέμῳ δορὸς

).476 Islanders often suffered contempt from the mainland Greeks: e.g. Sol. fr. 2 IEG, Hcld. 84 (above), Andr. 14–15 τῷ νησιώτῃ Νεοπτολέμῳ δορὸς

(with Stevens), Hdt. 8.125.2, Thuc. 6.77.1, Dem. 23.211. Here suspicions of piracy, for which cf. Thuc. 1.8.1, [Dem.] 58.56 and Plut. Cim. 8.3–5, may again play a part.

(with Stevens), Hdt. 8.125.2, Thuc. 6.77.1, Dem. 23.211. Here suspicions of piracy, for which cf. Thuc. 1.8.1, [Dem.] 58.56 and Plut. Cim. 8.3–5, may again play a part.

702. τίς ἦν; πόθεν; ποίας πάτρας; 682n. The series of interrogatives is paralleled in Ion 258–9 τίς δ᾽ εἶ;  ; ἐκ ποίας

; ἐκ ποίας  / πέϕυκας; and E. El. 779–80 τίνες /

/ πέϕυκας; and E. El. 779–80 τίνες /  πορεύεσθ᾽ ἔστε τ᾽ (Musgrave: πορεύεσθέ τ᾽ L) ἐκ ποίας χθονός; (cf. Diggle, Studies, 98).

πορεύεσθ᾽ ἔστε τ᾽ (Musgrave: πορεύεσθέ τ᾽ L) ἐκ ποίας χθονός; (cf. Diggle, Studies, 98).

Hermann (Opuscula III, 307) restored syntax and metre by removing the miscellaneous unmetrical additions in both MSS families, which look like successive attempts to ‘fill up’ the asyndetic text.

703. ‘Whom does he declare to be the highest of the gods?’

ἐπεύχεται /

ἐπεύχεται /  ὕπατον θεῶν; sc. εἶναι. Both

ὕπατον θεῶν; sc. εἶναι. Both  (Hermann, Opuscula III, 307) and

(Hermann, Opuscula III, 307) and  <δ᾽>

<δ᾽>  (Porson on Phoen. 892, Bothe, 5 [1803], 297) restore normal dochmiac responsion with 721,477 but the former is preferable for keeping the asyndetic sequence of the previous line. For (ἐπ)εύχομαι, ‘declare’, with accusative and infinitive cf. particularly IT 508 τὸ κλεινὸν

(Porson on Phoen. 892, Bothe, 5 [1803], 297) restore normal dochmiac responsion with 721,477 but the former is preferable for keeping the asyndetic sequence of the previous line. For (ἐπ)εύχομαι, ‘declare’, with accusative and infinitive cf. particularly IT 508 τὸ κλεινὸν

(sc. εἶναι) and Pi. Pyth. 4.97–8

(sc. εἶναι) and Pi. Pyth. 4.97–8  γαῖαν …

γαῖαν …  /

/  ἔμμεν; The notion of personal pride inherent in either verb from Homer on (693–4n.) seems fitting here, where the different appellations of Zeus appear to correspond to national distinctions (Paley on 703; cf. below). Yet possibly an undertone of the sacral sense is to be discerned as well.

ἔμμεν; The notion of personal pride inherent in either verb from Homer on (693–4n.) seems fitting here, where the different appellations of Zeus appear to correspond to national distinctions (Paley on 703; cf. below). Yet possibly an undertone of the sacral sense is to be discerned as well.

τὸν ὕπατον θεῶν: i.e. Zeus, to judge by 456–7 (455b–7n.) ὕπατος / Ζεύς. Murray (The Rhesus of Euripides, Oxford 1913, 64), followed by Liapis (on 703), quotes Hdt. 5.66.1 for the idea that someone’s tribal affiliations may be deduced from a god his relatives worship (Carian Zeus in this case). But in general the identification of a man by his religion was not common in ancient Greece, perhaps because it mattered little to their form of polytheism by which name a deity was addressed (cf. J. Assmann, in S. Budick – W. Iser [eds.], The Translatability of Cultures …, Stanford 1996, 25–36, especially 31–2, 34–5). ΣV Rh. 703 (II 342.13 Schwartz = 109 Merro) paraphrases with  ἐστιν

ἐστιν  πάτριος θεός;

πάτριος θεός;

704. ἆρ᾽᾽ ἔστ᾽ Ὀδύσσεως  τίνος τόδε; See 722n.

τίνος τόδε; See 722n.

705. εἰ τοῖς πάροιθε χρὴ τεκμαίρεσθαι: Cf. Alc. 239–40 τοῖς τε πάροιθεν /  and OT 915–16

and OT 915–16  ἀνήρ / ἔννους

ἀνήρ / ἔννους  καινὰ τοῖς

καινὰ τοῖς  τεκμαίρεται.

τεκμαίρεται.

πάροιθε refers to the Palladion theft, the ‘Ptôcheia’ and the unidentified ambush by the Thymbraean altar, which (against epic chronology) Hector recalled in 501–9 (498b–509, 501–2, 503–7a, 503–5, 507b–9a nn.). The ‘Ptôcheia’ will gain further room in the antistrophe (710–21n.).

πάροιθε refers to the Palladion theft, the ‘Ptôcheia’ and the unidentified ambush by the Thymbraean altar, which (against epic chronology) Hector recalled in 501–9 (498b–509, 501–2, 503–7a, 503–5, 507b–9a nn.). The ‘Ptôcheia’ will gain further room in the antistrophe (710–21n.).

τί μήν; ‘What else indeed?’, meaning ‘Of course’. See GP 333, Fraenkel on Ag. 672, G. Wakker, in NAGP, 214–15 n. 13 and, for the supposedly Sicilian origin of this expression, A. F. Garvie, Aeschylus’ Supplices: Play and Trilogy, Cambridge 1969, 54–5, FJW on A. Suppl. 999.

706. δοκεῖς γάρ; ‘What! You think so?’. γάρ lends the question a surprised and incredulous tone, implying doubt about the justification of the previous speaker’s words (GP 77–8).

τί μὴν οὔ; sc. δοκῶ. The only other case of this elliptical answer is S. El. 1280 ξυναινεῖς; –  (Seidler:

(Seidler:  codd.); On

codd.); On  see Wakker (705n.).

see Wakker (705n.).

707. θρασύς: 498b–500n. (  … θρασύς).

… θρασύς).

γοῦν: ‘at any rate’, introducing a ‘part proof’ argument for Odysseus’ responsibility. Cf. e.g. OC 319–20 οὐκ  ἄλλη.

ἄλλη.  γοῦν ἀπ᾽

γοῦν ἀπ᾽  /

/  προσστείχουσα, Alc. 693–4 and IT 72–3 (GP 451–2).

προσστείχουσα, Alc. 693–4 and IT 72–3 (GP 451–2).

708. ‘Cho.3 What (act of) valour are you praising? Whom? Cho.1 Odysseus.’

Ὀδυσσῆ: likewise Pi. Nem. 8.26, based on Od. 19.136  (+ Il. 4.384 Τυδῆ, 15.339 Μηκιστῆ). It may be coincidence that the only tragic parallels for this contracted accusative singular come from Euripides: El. 439

(+ Il. 4.384 Τυδῆ, 15.339 Μηκιστῆ). It may be coincidence that the only tragic parallels for this contracted accusative singular come from Euripides: El. 439  (Heath: -

(Heath: - L), Phaeth. 237 Diggle = E. fr. 781.24

L), Phaeth. 237 Diggle = E. fr. 781.24  (with J. Diggle, AC 65 [1996], 197). At Alc. 25 Diggle and Parker adopt ἱερέα (BsLs) instead of

(with J. Diggle, AC 65 [1996], 197). At Alc. 25 Diggle and Parker adopt ἱερέα (BsLs) instead of  (BOVLP) in dialogue verse.

(BOVLP) in dialogue verse.

709. κλωπὸς … ϕωτός: 644–5n. In the light of 705 (n.),  must also allude to the theft of the Palladion (cf. 502 κλέψας). Accordingly,

must also allude to the theft of the Palladion (cf. 502 κλέψας). Accordingly,  here has a contemptuous undertone, as more often does

here has a contemptuous undertone, as more often does  in prose: e.g. Lys. 4.19 διὰ

in prose: e.g. Lys. 4.19 διὰ  καὶ

καὶ  ἄνθρωπον, 30.28

ἄνθρωπον, 30.28  ἐτέρους ἀνθρώπους

ἐτέρους ἀνθρώπους  (KG I 272, LSJ s.v.

(KG I 272, LSJ s.v.  I 4). The same applies to ἄνδρες in 645 (cf. Ar. Pax 1120

I 4). The same applies to ἄνδρες in 645 (cf. Ar. Pax 1120  …

…  ἀνήρ).

ἀνήρ).

αἱμύλον δόρυ: For  (‘wily’) of Odysseus in tragedy see 498b–500n. Here the epithet is transferred from the man to his weapon, as in e.g. Pers. 320–1

(‘wily’) of Odysseus in tragedy see 498b–500n. Here the epithet is transferred from the man to his weapon, as in e.g. Pers. 320–1  … πολύπονον δόρυ / νωμῶν, Hcld. 500 … ἐχθρὸν

… πολύπονον δόρυ / νωμῶν, Hcld. 500 … ἐχθρὸν  (Elmsley:

(Elmsley:  L), 932–3

L), 932–3  ἐκ

ἐκ  σὺν

σὺν  /

/  (with Wilkins on 932).

(with Wilkins on 932).

710–21. Continuing the series of verbal reminiscences in the previous lines (707, 709nn.), this second account of the ‘Ptôcheia’ draws heavily on the vocabulary and syntax of 503–7a (n.). Note 711, 716 ~

503 ἔχων (‘with’), 712 στολᾷ ~ 503 στολήν, 715  τις

τις  ~ 503 ἀγύρτης, 717–19 πολλὰ δὲ τὰν /

~ 503 ἀγύρτης, 717–19 πολλὰ δὲ τὰν /  ἑστίαν Ἀτρειδᾶν

ἑστίαν Ἀτρειδᾶν  / ἔβαζε ~ 504–5 πολλὰ δ᾽ Ἀργείοις κακά / ἠρᾶτο. In addition to Od. 4.244–58 and the Cyclic tradition (Il. Parv. Arg. p. 122 (4) + frr. 8–10 GEF), there appears to be influence here from Athena’s transformation of Odysseus into a beggar in Od. 13.397–403 + 429–38. See M. Fantuzzi, MD 36 (1996), 182–3 and Rh. 710–11, 712–13a, 715–16nn.

/ ἔβαζε ~ 504–5 πολλὰ δ᾽ Ἀργείοις κακά / ἠρᾶτο. In addition to Od. 4.244–58 and the Cyclic tradition (Il. Parv. Arg. p. 122 (4) + frr. 8–10 GEF), there appears to be influence here from Athena’s transformation of Odysseus into a beggar in Od. 13.397–403 + 429–38. See M. Fantuzzi, MD 36 (1996), 182–3 and Rh. 710–11, 712–13a, 715–16nn.

710–14. ‘In the past too he came into our city, rheumy-eyed, wrapped in ragged clothes, with a sword hidden under his cloak.’

710–11. πάρος: 498b–509, 705nn.

ὕπαϕρον: ‘dim with tears, rheumy’ (cf. Hsch. υ 264 Hansen–Cunningham … τὸ  ἔχον

ἔχον  ἀϕρῷ) and so perhaps referring to conjunctivitis (a very common disease also associated with living in squalid conditions), like Latin lippus. This seems the most natural interpretation of the adjective here, which can be supported with ὕπαϕρος, ‘frothy’, in Gal. Cris. 1.5 (p. 78.4–5 Alexanderson) πτύσματα … ὕπαϕρα, ΣbT Il. 14.16 (III 565.48–9 Erbse) τὸ

ἀϕρῷ) and so perhaps referring to conjunctivitis (a very common disease also associated with living in squalid conditions), like Latin lippus. This seems the most natural interpretation of the adjective here, which can be supported with ὕπαϕρος, ‘frothy’, in Gal. Cris. 1.5 (p. 78.4–5 Alexanderson) πτύσματα … ὕπαϕρα, ΣbT Il. 14.16 (III 565.48–9 Erbse) τὸ  … τὸ μηδέπω

… τὸ μηδέπω

ἐκ κυμάτων παϕλαζόντων (cf. Eust. 964.50), probably Hp. de Arte 10.5 (fifth or fourth century BC) and ὑπαϕρίζω, ‘to foam a little’, in e.g. Eust. 586.8–9. The more frequent rendering ‘hidden, secret’ (ΣL Rh. 711 [II 342.27–8 Schwartz = 109 a2 Merro]

ἐκ κυμάτων παϕλαζόντων (cf. Eust. 964.50), probably Hp. de Arte 10.5 (fifth or fourth century BC) and ὑπαϕρίζω, ‘to foam a little’, in e.g. Eust. 586.8–9. The more frequent rendering ‘hidden, secret’ (ΣL Rh. 711 [II 342.27–8 Schwartz = 109 a2 Merro]  ὁ

ὁ  ϕανερός, ἐκ

ϕανερός, ἐκ  τῶν ὑπ᾽

τῶν ὑπ᾽  νηχομένων, ἢ τῶν

νηχομένων, ἢ τῶν  αἷς ἐπανθεῖ ἀϕρός, ΣV Rh. 711 [109 a1 Merro] ὕπουλον; cf. e.g. Hsch. υ 264 Hansen–Cunningham, Phot. υ 84 Thedoridis, Erot. υ 10 Nachmanson478) may in fact be due to mis- or overinterpretation of the prefix (Jouanna on Hp. de Arte 10.5 [p. 261]). ΣL Rh. 711 (II 342.29 Schwartz = 109 a2 Merro)

αἷς ἐπανθεῖ ἀϕρός, ΣV Rh. 711 [109 a1 Merro] ὕπουλον; cf. e.g. Hsch. υ 264 Hansen–Cunningham, Phot. υ 84 Thedoridis, Erot. υ 10 Nachmanson478) may in fact be due to mis- or overinterpretation of the prefix (Jouanna on Hp. de Arte 10.5 [p. 261]). ΣL Rh. 711 (II 342.29 Schwartz = 109 a2 Merro)  καταπληκτικός, ὁ μανικός shows that some here understood the word to be the neuter of

καταπληκτικός, ὁ μανικός shows that some here understood the word to be the neuter of  , ‘slightly stupid’ (Hdt. 4.95.2).

, ‘slightly stupid’ (Hdt. 4.95.2).

If the above explanation is right,  ὄμμ᾽ ἔχων can be taken to mirror the effect of Athena’s action at Od. 13.433 (~ 401) κνύζωσεν δέ οἱ ὄσσε

ὄμμ᾽ ἔχων can be taken to mirror the effect of Athena’s action at Od. 13.433 (~ 401) κνύζωσεν δέ οἱ ὄσσε  περικαλλέ᾽ ἐόντε (‘she dimmed his eyes …’; cf. Hsch. κ 3148 Latte κνυζοί· οἱ τὰ

περικαλλέ᾽ ἐόντε (‘she dimmed his eyes …’; cf. Hsch. κ 3148 Latte κνυζοί· οἱ τὰ  πονοῦντες). Hermann (on Hec. 238, 239) had already compared it to Hec. 240–1

πονοῦντες). Hermann (on Hec. 238, 239) had already compared it to Hec. 240–1  τ᾽ ἄπο /

τ᾽ ἄπο /

σὴν κατέσταζον γένυν (cf. 503–7a n.).

σὴν κατέσταζον γένυν (cf. 503–7a n.).

712–13a. ῥακοδύτῳ στολᾷ / πυκασθείς seems to have been phrased after Od. 22.488 ῥάκεσιν  ὤμους. In the Odyssey ῥάκος and ῥάκεα (which do not appear in the Iliad) almost exclusively refer to Odysseus’ beggar disguise on Ithaca (e.g. 13.434, 14.342, 349, 512). Regarding the ‘Ptôcheia’, cf. Ar. Vesp. 351 εἶτ᾽ ἐκδῦναι ῥάκεσιν κρυϕθεὶς ὥσπερ πολύμητις Ὀδυσσεύς.

ὤμους. In the Odyssey ῥάκος and ῥάκεα (which do not appear in the Iliad) almost exclusively refer to Odysseus’ beggar disguise on Ithaca (e.g. 13.434, 14.342, 349, 512). Regarding the ‘Ptôcheia’, cf. Ar. Vesp. 351 εἶτ᾽ ἐκδῦναι ῥάκεσιν κρυϕθεὶς ὥσπερ πολύμητις Ὀδυσσεύς.

ῥακόδυτος, ‘dressed in rags’ or here ‘ragged’, is elsewhere attested only in Hsch. κ 331 Latte  (Od. 18.41)· ῥακκοδύτους (sic). But Patristic and Byzantine Greek has

(Od. 18.41)· ῥακκοδύτους (sic). But Patristic and Byzantine Greek has  (‘beg’),

(‘beg’),  (‘beggar’) ans the collateral ῥακενδυτ-.

(‘beggar’) ans the collateral ῥακενδυτ-.

713b–14. ξιϕήρης / κρύϕιος ἐν πέπλοις: literally ‘secretly equipped with a sword under his cloak’. Cf. Or. 1125  ἐν πέπλοισι

ἐν πέπλοισι

ξίϕη, 1271–2

ξίϕη, 1271–2  /

/  ϕανεῖ, both of the plot to kill Helen, whose important role in the ‘Ptôcheia’ our poet suppressed (503–7a n.). For a more natural use of predicative

ϕανεῖ, both of the plot to kill Helen, whose important role in the ‘Ptôcheia’ our poet suppressed (503–7a n.). For a more natural use of predicative  see Hec. 993 καὶ

see Hec. 993 καὶ  γ᾽

γ᾽  σὲ

σὲ  ἐζήτει

ἐζήτει  and HF 598 ὥστ᾽ …

and HF 598 ὥστ᾽ …  χθόνα.

χθόνα.

In ξιϕήρης, which is not safely attested before Euripides (also Andr. 1114, El. 225, Ion 1153, 1258, Phoen. 363, Or. 1346, 1627) and does not recur until the first century BC, the kinship with  is still apparent, while elsewhere -ήρης has mostly lost its meaning (Wilamowitz on HF 243, J. Wackernagel, Progr. Univ. Basel (1889), 41 = KS II, 937). Cf. 226b–8n. (on τοξήρης).

is still apparent, while elsewhere -ήρης has mostly lost its meaning (Wilamowitz on HF 243, J. Wackernagel, Progr. Univ. Basel (1889), 41 = KS II, 937). Cf. 226b–8n. (on τοξήρης).

κρύϕιος: Bothe (3 [1824], 366) and Morstadt (Beitrag, 41) for the unmetrical  (Ω). Kaibeliani (kδ) in ‘responsion’ with normal dochmiacs are generally emended away (e.g. Sept. 233a ~ 239a, OT 657b ~ 686b, Or. 147b ~ 160b). This quite frequent MSS error may in part be due to the same tendency that caused unrecognised dochmiacs to be filled up to make iambic trimeters, however imperfect (Fraenkel on Ag. 478 with n. 2, Dodds on Ba. 1188 and, for kδ, Willink on Or. 1246–85 [p. 288]).

(Ω). Kaibeliani (kδ) in ‘responsion’ with normal dochmiacs are generally emended away (e.g. Sept. 233a ~ 239a, OT 657b ~ 686b, Or. 147b ~ 160b). This quite frequent MSS error may in part be due to the same tendency that caused unrecognised dochmiacs to be filled up to make iambic trimeters, however imperfect (Fraenkel on Ag. 478 with n. 2, Dodds on Ba. 1188 and, for kδ, Willink on Or. 1246–85 [p. 288]).

715–16. ‘And begging his bread he crept around, a vagabond menial, his head all rough and dirty.’

βίον δ᾽᾽ ἐπαιτῶν: Cf. OC 1364  καθ᾽ ἡμέραν

καθ᾽ ἡμέραν  and Hel. 790–1 (Με.) τοῖσδ᾽ (sc.

and Hel. 790–1 (Με.) τοῖσδ᾽ (sc.  πυλώμασιν), ἔνθεν ὥσπερ

πυλώμασιν), ἔνθεν ὥσπερ  ἐξηλαυνόμην. / (Ελ.)

ἐξηλαυνόμην. / (Ελ.)  ;In classical Greek ἐπαιτέω, originally ‘ask in addition’ (Il. 23.593), is otherwise attested only in OT 1416 and S. El. 1124 (middle), both times meaning ‘request urgently’, while later it becomes common for beggary. See LSJ s.v. 2 and especially the agent noun ἐπαίτης.

;In classical Greek ἐπαιτέω, originally ‘ask in addition’ (Il. 23.593), is otherwise attested only in OT 1416 and S. El. 1124 (middle), both times meaning ‘request urgently’, while later it becomes common for beggary. See LSJ s.v. 2 and especially the agent noun ἐπαίτης.

: in the literal sense (‘creep around’) also Sept. 17–19

: in the literal sense (‘creep around’) also Sept. 17–19  γὰρ νέους

γὰρ νέους  / … /

/ … /  and, of the lame Philoctetes, Phil. 206–7

and, of the lame Philoctetes, Phil. 206–7  στίβον

στίβον  ἀνάγ- / καν

ἀνάγ- / καν  (‘dragging along’).

(‘dragging along’).

ἀγύρτης τις λάτρις: For  in the sense ‘vagabond’ see 503–5n. and for λάτρις, hired servant’ (as against the much rarer ‘slave’), Wilamowitz on HF 823. The latter is popular with Euripides, as is the placing of one noun in an attributive relationship to an other (701n.).

in the sense ‘vagabond’ see 503–5n. and for λάτρις, hired servant’ (as against the much rarer ‘slave’), Wilamowitz on HF 823. The latter is popular with Euripides, as is the placing of one noun in an attributive relationship to an other (701n.).

It is tempting to suggest that our poet created his begging ‘vagabond menial’ from a combination of Od. 4.245 σπεῖρα κάκ᾽  ὤμοισι

βαλών, οἰκῆϊ ἐοικώς and its probable doublet 4.247–8 ἄλλῳ δ᾽ αὐτὸν ϕωτὶ κατακρύπτων ἤϊσκε / Δέκτῃ. In that case he would have been a precursor of Aristarchus, who understood ΔΕΚΤΗΙ to mean ἐπαίτῃ (‘beggar’), whereas in the Little Iliad, we are told, it was a proper name: Σ Od. 4.248 (II 254.84–9 Pontani) = Il. Parv. fr. 9 GEF. Cf. S. R. West on Od. 4.246–9, M. Fantuzzi, MD 36 (1996), 183–5, A. Fries, CQ n.s. 60 (2010), 349–50 (+ Introduction, 37), West, Epic Cycle, 196–7.

ὤμοισι

βαλών, οἰκῆϊ ἐοικώς and its probable doublet 4.247–8 ἄλλῳ δ᾽ αὐτὸν ϕωτὶ κατακρύπτων ἤϊσκε / Δέκτῃ. In that case he would have been a precursor of Aristarchus, who understood ΔΕΚΤΗΙ to mean ἐπαίτῃ (‘beggar’), whereas in the Little Iliad, we are told, it was a proper name: Σ Od. 4.248 (II 254.84–9 Pontani) = Il. Parv. fr. 9 GEF. Cf. S. R. West on Od. 4.246–9, M. Fantuzzi, MD 36 (1996), 183–5, A. Fries, CQ n.s. 60 (2010), 349–50 (+ Introduction, 37), West, Epic Cycle, 196–7.

ψαϕαρόχρουν: most likely ‘with rough skin, scabby’, though not necessarily implying baldness (ΣV Rh. 716 [II 342.4 Schwartz = 110 Merro]). The word appears only here and was probably coined for the occasion. Many adjectives in -χρως (-χροος, -χρωτος), often without direct reference to the skin, are first attested in Euripides, especially in the lyrics of his later plays: e.g. Hel. 215 χιονόχρῳ κύκνου πτερῷ, Phoen. 322–3 λευκόχροα … κόμαν, Hel. 1502–3 κυανόχροά τε κυμάτων / ῥόθια πολιὰ θαλάσσας, Phoen. 308–9 κυανόχρωτι χαί- / τας πλοκάμῳ (Mastronarde on Phoen. 138).

A possible model is ψαϕαρόθριξ, ‘rough-haired’ (of sheep), in h.Pan. 32.  (‘powdery, crumbling’) is generally rare in poetry before Hellenistic times: only Sept. 323 ψαϕαρᾷ

(‘powdery, crumbling’) is generally rare in poetry before Hellenistic times: only Sept. 323 ψαϕαρᾷ  and maybe Pl. Com. fr. 126 PCG ψαϕαρόν = ἁπαλόν. Later cf. especially Nic. Ther. 369 καὶ τόθ᾽ ὅγ᾽ ἐν χερσῷ τελέθει ψαϕαρός τε καὶ ἄχρους (i.e. the χέρσυδρος, an amphibious snake).

and maybe Pl. Com. fr. 126 PCG ψαϕαρόν = ἁπαλόν. Later cf. especially Nic. Ther. 369 καὶ τόθ᾽ ὅγ᾽ ἐν χερσῷ τελέθει ψαϕαρός τε καὶ ἄχρους (i.e. the χέρσυδρος, an amphibious snake).

Fantuzzi (MD 36 [1996], 182–3) sees here an allusion to Odysseus’ miraculous ageing at the hands of Athena in Od. 13.431–2 ξανθὰς δ᾽ ἐκ κεϕαλῆς ὄλεσε τρίχας, ἀμϕὶ δὲ δέρμα / πάντεσσιν μελέεσσι παλαιοῦ θῆκε γέροντος. If so Od. 13.430 (~ 398) κάρψε μέν οἱ χρόα καλὸν ἐνὶ γναμπτοῖσι  (with κάρϕω = ‘dry up, wither’: cf. Hes. Op. 575, Archil. fr. 188.1–2 IEG) should also be taken into account.

(with κάρϕω = ‘dry up, wither’: cf. Hes. Op. 575, Archil. fr. 188.1–2 IEG) should also be taken into account.

πολυπινές: another classical hapax. For πίνος, ‘filth’ (on clothes or the body), cf. OC 1259, E. El. 305 and A. R. 2.200–1 (of Phineus) πίνῳ δέ οἱ αὐσταλέος χρώς / ἐσκλήκει. Similar compound adjectives in drama are δυσπινής (OC 1597, Ar. Ach. 426 ~ fr. tr. adesp. 42), κακοπινής (Ai. 381, metaphorically of Odysseus) and εὐπινής, ‘tidy’, in E. fr. 494.11 and Cratin. fr. 455 PCG.

717–19. The mythical background of Odysseus’ denunciations (by which he pretends to be a Greek deserter) is discussed in 503–5n.

πολλὰ δὲ τὰν / βασιλίδ᾽ ἑστίαν Ἀτρειδᾶν κακῶς / ἔβαζε: The construction with the adverb is equivalent to πολλὰ … κακὰ ἔβαζε (KG I 295, 323–4).  governs a double accusative also at Il. 9.58–9 ἀτὰρ πεπνυμένα βάζεις / Ἀργείων βασιλῆας, 16.207 ταῦτά μ᾽ … θάμ᾽ ἐβάζετε and Hipp. 118–19 εἴ τις σ᾽ … / μάταια βάζει.

governs a double accusative also at Il. 9.58–9 ἀτὰρ πεπνυμένα βάζεις / Ἀργείων βασιλῆας, 16.207 ταῦτά μ᾽ … θάμ᾽ ἐβάζετε and Hipp. 118–19 εἴ τις σ᾽ … / μάταια βάζει.

Adjectival βασιλίς is paralleled in IA 1305–6 Ἥρα δὲ Διὸς ἄνακτος / εὐναῖσι βασιλίσιν (sc. τρυϕῶσα). See 701n. and Introduction, 34.

δῆθεν: ‘as if …’, implying falsehood. The particle rarely precedes the phrase it qualifies, but cf. PV 986 ἐκερτόμησας δῆθεν ὥσ<τε> παῖδά με, Tr.  ᾽καλεῖτο, τῆς ἐκεῖνος οὐδαμά / βλάστας ἐϕώνει δῆθεν οὐδὲν ἱστορῶν, Or. 1119 ἔσιμεν ἐς οἴκους

᾽καλεῖτο, τῆς ἐκεῖνος οὐδαμά / βλάστας ἐϕώνει δῆθεν οὐδὲν ἱστορῶν, Or. 1119 ἔσιμεν ἐς οἴκους  ὡς θανούμενοι and Thuc. 1.127.1 τοῦτο δὴ τὸ ἄγος οἱ Λακεδαιμόνιοι ἐκέλευον ἐλαύνειν δῆθεν τοῖς θεοῖς πρῶτον τιμωροῦντες (GP 265–6).

ὡς θανούμενοι and Thuc. 1.127.1 τοῦτο δὴ τὸ ἄγος οἱ Λακεδαιμόνιοι ἐκέλευον ἐλαύνειν δῆθεν τοῖς θεοῖς πρῶτον τιμωροῦντες (GP 265–6).

720–1. ‘I wish he had perished, perished as he deserved, before setting foot on the Phrygians’ land!’

ὄλοιτ᾽ ὄλοιτο: In curses  has become so stereotyped that the optative can be used for an unrealisable wish in the past (KG I 228, SD 322). Likewise A. Suppl. 867–71 εἰ γὰρ δυσπαλάμως ὄλοιο / δι᾽ ἁλίρρυτον ἄλσος / … ἀλαθεὶς / Συρίαισιν αὔραις, Hipp. 407–9 ὡς ὄλοιτο παγκάκως / ἥτις

has become so stereotyped that the optative can be used for an unrealisable wish in the past (KG I 228, SD 322). Likewise A. Suppl. 867–71 εἰ γὰρ δυσπαλάμως ὄλοιο / δι᾽ ἁλίρρυτον ἄλσος / … ἀλαθεὶς / Συρίαισιν αὔραις, Hipp. 407–9 ὡς ὄλοιτο παγκάκως / ἥτις  ἄνδρας ἤρξατ᾽ αἰσχύνειν λέχη / πρώτη θυραίους and Hel. 1215 ὅπου κακῶς ὄλοιτο, Μενέλεως δὲ μή (with Kannicht on 1214–5). The anadiplosis has a match in Ion 705 (referring to the present).

ἄνδρας ἤρξατ᾽ αἰσχύνειν λέχη / πρώτη θυραίους and Hel. 1215 ὅπου κακῶς ὄλοιτο, Μενέλεως δὲ μή (with Kannicht on 1214–5). The anadiplosis has a match in Ion 705 (referring to the present).

πρὶν ἐπὶ γᾶν Φρυγῶν ποδὸς ἴχνος βαλεῖν: The clause is Euripidean in style. Cf. IT 752 μήποτε κατ᾽  ζῶσ᾽ ἴχνος θείην ποδός, El. 1344 δεινὸν γὰρ ἴχνος βάλλουσ᾽ ἐπὶ σοί (i.e. the Erinyes) and for ποδὸς ἴχνος = ‘foot’ also HF 125, Tro. 3, Ion 792, Phoen. 105 and E. fr. 530.7 (Ritchie 209–10).

ζῶσ᾽ ἴχνος θείην ποδός, El. 1344 δεινὸν γὰρ ἴχνος βάλλουσ᾽ ἐπὶ σοί (i.e. the Erinyes) and for ποδὸς ἴχνος = ‘foot’ also HF 125, Tro. 3, Ion 792, Phoen. 105 and E. fr. 530.7 (Ritchie 209–10).

Φρυγῶν: 32n.

722. The verse echoes 704 with almost corresponding word-ends and Ὀδυσσέως at the same metrical position. Likewise 24 ~ 42 Ἕκτορ (with 23–4n.).

εἴτ᾽ οὖν … εἴτε: ‘Whether, in point of fact, … or … ’, with οὖν marking indifference (GP 418–19). The combination is typical of tragedy and Plato.

ϕόβος μ᾽ ἔχει (or ϕόβος ἔχει με) also appears in A. Suppl. 379, Ag. 1243, S. fr. 314.278 (Ichneutae), Med. [356], Or. 1255 and Hyps. fr. 64 ii.76 Bond = E. fr. 759a.1597. In Euripides the periphrasis of a verb of feeling by way of its abstract noun with ἔχει (LSJ s.v. ἔχω (A) A I 8) has almost become a mannerism. Add Hec. 970, Or. 460 (~ 101), Ba. 828 (+ A. fr. 132c.12) αἰδώς μ ᾽ ἔχει, HF 515, IA 837, Ar. Thesm. 904 (‘Euripides’ speaking) ἀϕασία μ᾽ ἔχει, and see Kannicht on Hel. 558.

724. δυσοίζων: a very rare verb, attested elsewhere only in Ag. 1316  δυσοίζω θάμνον ὡς ὄρνις ϕόβῳ and Rh. 805 (804–5n.) μηδὲν δυσοίζου. Both etymology and meaning are disputed, but it seems easiest to explain it as an irregular compound of οἴζω (< οἰοί: A. D. Adv. 128.7 Schneider; cf. Schwyzer 716 on -ζω as a mode of verbifying interjections that end in vowels), which denotes a sharp cry of distress or here rather indignation (ΣV Rh. 724 [II 342.16–17 Schwartz = 110 Merro] βλασϕημῶν. ἢ

δυσοίζω θάμνον ὡς ὄρνις ϕόβῳ and Rh. 805 (804–5n.) μηδὲν δυσοίζου. Both etymology and meaning are disputed, but it seems easiest to explain it as an irregular compound of οἴζω (< οἰοί: A. D. Adv. 128.7 Schneider; cf. Schwyzer 716 on -ζω as a mode of verbifying interjections that end in vowels), which denotes a sharp cry of distress or here rather indignation (ΣV Rh. 724 [II 342.16–17 Schwartz = 110 Merro] βλασϕημῶν. ἢ  καὶ λοιδορῶν). See further A. Debrunner,

IF 21 (1907), 273 and Fraenkel on Ag. 1316, who not quite justly compares the verbal adjective δυσβάϋκτος (< βαΰζω, βαύ) in Pers. 574.

καὶ λοιδορῶν). See further A. Debrunner,

IF 21 (1907), 273 and Fraenkel on Ag. 1316, who not quite justly compares the verbal adjective δυσβάϋκτος (< βαΰζω, βαύ) in Pers. 574.

725. τί δρᾶσαι: L. Dindorf ’s correction (I [1825], 492 ~ W. Dindorf, III.2 [1840], 617–18) of the MSS’ τί δρᾶς; (… δρᾶς δὴ; Tr1) is supported by the infinitive περᾶσαι in the following line. Wilamowitz’ τί δράσας; (on HF 540), accepted by Porter and Kovacs (‘At what ill fortune?’), can also be excluded for semantic reasons, since in this and similar questions δρᾶν always refers to a physical action by its subject (e.g. HF 540, 1136, 1187, Or. 849). Cf. D. J. Mastronarde, ElectronAnt 8 (2004), 22.

727. ἐς Φρυγῶν στρατόν: 32n. Similarly 846 Φρυγῶν στρατός.

728–55. Both metrically and in terms of content this ‘interlude’ forms a transition between the preceding, almost entirely lyric search-scene and the narrative-agonistic episode of 756–881. The sentries, still groping in the dark at first in the hope of catching an intruder (730), meet Rhesus’ badly injured Charioteer instead and with painful slowness, which again betrays their lack of visual (736–7) and mental (745–6) perception, make out his nationality and preoccupation. The humble Thracian meanwhile – a substitute for the king’s cousin Hippocoon (< ἵππος + κοέω: ‘he who looks after horses’), who in Il. 10.518–22 is woken by Apollo to discover the slaughter in the camp (Ritchie 74–5) – is so absorbed in his grief and agony that he does not even react to the coryphaeus’ question in 736. In this emotional isolation479 he resembles characters like Xerxes in Pers. 908–16, Oedipus in OT 1307–18, Creon in Ant. 1261–9, Antigone in Phoen. 1485–1529 and especially the mortally wounded Hippolytus (Hipp. 1347–88) with his comic counterpart Lamachus (Ar. Ach. 1190–1234),480 whose respective lamentations offer some striking verbal and structural similarities (731–2, 733, 734–5, 750–1a nn.). Nearly all these entries, including the parody in Acharnians, are preceded by an account of the catastrophic events off-stage (in Persians it is the prediction of Plataea by the Ghost of Darius), while here the Charioteer himself will bring the news of the Thracian disaster: 756–803 (n.). With the relatively uniform introductions to Euripidean messenger-speeches (1–51n.) the present passage shares only an equivalent of the ‘general announcement’ (728b, 732a), the ‘information in brief’ (735, 742–4, 747–8, 752–3) and the ‘question for the addressee’ (738–40) – all in so free an order and arrangement as not even the (semi-)lyric compositions of HF 910–21, Ba. 1024–42 and Phoen. 1335–55 display.481 Moreover, the chorus-leader fails to ask for a detailed report after 755, which gives the impression that the following speech is still directed at no one in particular (Strohm 272 with n. 2).

Influenced as it seems by two different scene types, the Charioteer’s entry at once points to his double function as victim and messenger so as to prepare for his unusually subjective narrative482 and stubborn belief in the Trojans’ guilt. Yet the reminiscence of great tragic heroes in misery adds a somewhat incongruous note, although it may have been intended to raise the Thracian’s importance and pathos, even beyond such individual figures as the Guard in Ant. 223–331 and 384–445.

Metre

Given the trochaic tetrameters catalectic of 730 and 732, the Charioteer’s lyric opening line 728b is best regarded with Diggle as a syncopated trochaic trimeter (tr tr | ‘sp’ ||) after extra-metric ἰὼ ἰώ (cf. 731 and 733a)483 or perhaps even a trochaic dimeter with ϕεῦ ϕεῦ again extra metrum (for other analyses see Willink, ‘Cantica’, 41–2 = Collected Papers, 580).484 His longer outbursts are set in recitative anapaests (733–5, 738–44, 747–53: cf. e.g. Pers. 908–16 and Hipp. 1347–69), to which the coryphaeus responds with pairs of iambic trimeters (736–7, 745–6, 754–5). Formally this alternation of actor’s laments and choral spoken verse most closely resembles such semi-lyric amoibaia as Ag. 1072–1113 (the first four strophic pairs of the Cassandra-scene), OT 1313–68 or indeed Pers. 249–89, where Xerxes’ messenger adheres to iambics while the shocked chorus reply in dochmiacs. Likewise in HF 910–21, Ba. 1024–42 and Phoen. 1335–55, which like our passage begins with 4tr‸, although most of the remainder (1338–53) should go with 1308–34 (n. 267), it is the recipients of the news who burst into short snatches of song.485 The reverse pattern here underlines again the exceptional status of the victim-messenger.

728b. δαίμονος τύχα βαρεῖα: Cf. Med. 671 ἄπαιδές ἐσμεν δαίμονός τινος τύχῃ, Hipp. 831–3 πρόσωθεν δέ ποθεν ἀνακομίζομαι / τύχαν δαιμόνων ἀμπλακίαισι τῶν / πάροιθέν τινος, IT 865 + 867 and E. fr. 37. In this type of expression  denotes the intervention of a known or unknown deity (LSJ s.v. I 1 a) with advantageous (e.g. Pi. Ol. 8.67, Pyth. 8.53, Nem. 4.6–8) or detrimental effect upon men.

denotes the intervention of a known or unknown deity (LSJ s.v. I 1 a) with advantageous (e.g. Pi. Ol. 8.67, Pyth. 8.53, Nem. 4.6–8) or detrimental effect upon men.

τύχα βαρεῖα also occurs in Sept. 332 βαρείας τοι τύχας προταρβῶ, Ai. 980 ὤμοι βαρείας ἆρατῆς ἐμῆς τύχης, Hipp. 818–19 (with Barrett on 818–20), E. El. 300–1 and Phaeth. 93–4 Diggle = E. fr. 773.49–50 (with Diggle on 94). Similarly Rh. 731–2 (n.)  ἰώ· / συμϕορὰ βαρεῖα Θρῃκῶν.

ἰώ· / συμϕορὰ βαρεῖα Θρῃκῶν.

729. ἔα ἔα: in Euripides nearly always extra metrum (675–82 ‘Metre’ 675n.). On the meaning and etymology of ἔα see 574n.

730. ‘Crouch down in silence, everyone! Perhaps somebody is falling within the cast of our net.’

σῖγα πᾶς ὕϕιζ᾽: Cf. 680, 687 (nn.) and, in a very similar situation, Ar. Ach. 238 σῖγα πᾶς. ἠκούσατ᾽, ἄνδρες, ἆρα τῆς εὐϕημίας; L. Dindorf’s σῖγα (I [1825], 492 ~ W. Dindorf, III.2 [1840], 618) for σίγα (VQ: σιγᾶ L) is required by syntax and metre – an easy corruption with parallels in e.g. Ar. Ach. 238 (above), Hec. 532 and Or. 140. On σῖγα, especially in imperatives, see E. Schwyzer, Glotta 12 (1923), 27–8 = KS 483–4.

ὕϕιζ᾽ is Reiske’s correction (Animadversiones, 91), after Barnes (129), of the transmitted ὕϕιζος (V) or ὕβριζ᾽ (Λ). The verb is unique in classical Greek, except for the transitive Ionic aorist participle  in Hdt. 3.126.2 and 6.103.3. The same applies to ὑϕιζάνω (Phoen. 1382–3 ἀλλ᾽ ὑϕίζανον κύκλοις, / ὅπως σίδηρος ἐξολισθάνοι μάτην, Aristotle and late).

in Hdt. 3.126.2 and 6.103.3. The same applies to ὑϕιζάνω (Phoen. 1382–3 ἀλλ᾽ ὑϕίζανον κύκλοις, / ὅπως σίδηρος ἐξολισθάνοι μάτην, Aristotle and late).

ἴσως γὰρ ἐς βόλον τις ἔρχεται is reminiscent of Ba. 848 … ἁνὴρ ἐς βόλον καθίσταται and E. fr. 62d.29 … εἰςβόλονγὰρ ἂν πέσοι and may be a proverbial fishing metaphor (C. B. Sneller, De Rheso Tragoedia, Amsterdam 1949, 68 n. 1). Cf. Herod. 7.75–6 ὠς, ἤν τι μὴ νῦν ἦμιν ἐς βόλον κύρσῃ, / οὐκ οἶδ᾽ ὄκως ἄμεινον ἠ χύτρη πρήξει and Hdt. 1.62.4 (oracle) ἔρριπται δ᾽ ὁ βόλος, τὸ δὲ δίκτυον ἐκπεπέτασται, / θύννοι δ᾽ οἱμήσουσι σεληναίης διὰ νυκτός.

731–2. Syntax and speaker assignations were restored by Hermann (Opuscula III, 307). Most MSS read and divide ἰὼ ἰώ · / συμϕορὰ βαρεῖα Θρῃκῶν συμμάχων / τίς ὁ στένων; But συμμάχων fits better in a statement initiating the chorus’ lengthy realisation process (728–55n.); cf. 736 and 755. By the same token, ἰὼ ἰώ … Θρῃκῶν cannot belong to them (Liapis on 732).

ἰὼ ἰώ·· / συμϕορὰ βαρεῖα Θρῃκῶν: For the wording cf. especially Tim. Pers. fr. 791.187 PMG = Hordern <ἰ>ὼ βαρεῖα συμϕορά, which imitates Pers. 1043–4 ὀτοτοτοτοῖ· /  γ᾽ ἅδε συμϕορά. The resemblance to Ar. Ach. 1204 ὦ συμϕορὰ τάλαινα τῶν ἐμῶν κακῶν (Ritchie 3) and 1210 τάλας

γ᾽ ἅδε συμϕορά. The resemblance to Ar. Ach. 1204 ὦ συμϕορὰ τάλαινα τῶν ἐμῶν κακῶν (Ritchie 3) and 1210 τάλας  ξυμβολῆς βαρείας is also noteworthy (728–55n.).

ξυμβολῆς βαρείας is also noteworthy (728–55n.).

On the exclamatory nominative (as in 728b and 733b) see KG I 46 and SD 65–6; after ἰὼ (ἰώ) e.g. Pers. 1073, Sept. 994, Ai. 893, Tro. 1118–19, Ion 912.

733. δύστηνος ἐγώ is a set-phrase in anapaestic laments (Pers. 908–10, OT 1307/8, Med. 96, Hipp. 239, 1348, HF 448, Tro. 112), but here, before σύ τ᾽ ἄναξ Θρῃκῶν, it gains special significance by suggesting that the Charioteer is more concerned with his own fate than that of his master. Cf. 752 (752–3n.) χρῆν γάρ μ᾽ ἀκλεῶς Ῥῆσόν τε θανεῖν.

734–5. ‘O you who looked on Troy (that proved) most hateful (to us), what a death has taken you away!’

ὦ στυγνοτάτην Τροίαν ἐσιδών: Liapis (on 734–5) probably rightly suspects an echo of Pers. 974–6 (Xerxes speaking) ἰώ, ἰώ μοι · / τὰς  κατιδόντες / στυγνὰς Ἀθάνας. In both places στυγνός bears an anticipatory sense equivalent to that of πικρός in e.g. Od. 17.447–8 στῆθ᾽ … ἐμῆς ἀπάνευθε τραπέζης, / μὴ τάχα πικρὴν Αἴγυπτον καὶ Κύπρον ἴδηαι (v.l. ἵκηαι), Phil. 355–6 κἀγὼ

κατιδόντες / στυγνὰς Ἀθάνας. In both places στυγνός bears an anticipatory sense equivalent to that of πικρός in e.g. Od. 17.447–8 στῆθ᾽ … ἐμῆς ἀπάνευθε τραπέζης, / μὴ τάχα πικρὴν Αἴγυπτον καὶ Κύπρον ἴδηαι (v.l. ἵκηαι), Phil. 355–6 κἀγὼ  Σίγειον οὐρίῳ πλάτῃ / κατηγόμην and Hec. 772 ἐνταῦθ᾽ ἐπέμϕθη πικροτάτου χρυσοῦ ϕύλαξ (LSJ s.v. πικρός III 1 ‘… of what yields pain instead of expected pleasure’, FJW on A. Suppl. 1033 [III, p. 319]).

Σίγειον οὐρίῳ πλάτῃ / κατηγόμην and Hec. 772 ἐνταῦθ᾽ ἐπέμϕθη πικροτάτου χρυσοῦ ϕύλαξ (LSJ s.v. πικρός III 1 ‘… of what yields pain instead of expected pleasure’, FJW on A. Suppl. 1033 [III, p. 319]).

ὦ στυγνοτάτην could be a reminiscence of Hipp. 1355 ὦ στυγνὸν ὄχημ᾽  … (cf. 728–55n.), but similar apostrophes are found in Pers. 472 (ὦ στυγνὲ δαῖμον) and Phil. 1348 (ὦ στυγνὸς αἰών).

… (cf. 728–55n.), but similar apostrophes are found in Pers. 472 (ὦ στυγνὲ δαῖμον) and Phil. 1348 (ὦ στυγνὸς αἰών).

736–7. ‘Which of our allies are you? My vision is dimmed at night, and I cannot make you out clearly.’

κατ᾽ εὐϕρόνην: 91–2n.

ἀμβλῶπες αὐγαί: Photius (α 1164 Theodoridis) has given us an interesting parallel in E. fr. 397a (Thyestes) ἀμβλῶπας αὐγὰς ὀμμάτων ἔχεις σέθεν (Reitzenstein: ἀμβλωπὰς bz). He further attests ἀμβλώψ (rather than ἀμβλωπός: Eum. 955, E. frr. 155a ἀμβλωπὸς ὄψις, 386a, Critias 88 B 6.11 DK = fr. 6.10 IEG) for Sophocles (fr. 1001), Ion (TrGF 19 F 53a) and Plato the Comedian (fr. 254 PCG). Like δίβαμος (214–15n.), this form of the adjective had previously been a hapax (Ritchie 151, 210, Fraenkel, Rev. 230).

Bare αὐγαί, ‘eyes’, is paralleled in h.Merc. 361, A. (?) fr. 99.13 (Cares = Europa)486 ἀλλ᾽ οὐκ ἐν αὐγαῖς ταῖς ἐμαῖς ζόη σϕ᾽ ἔχει, Andr. 1179–80 …  487 and, figuratively, Pl. Rep. 540a6–8 καὶ ἀναγκαστέον ἀνακλίναντας τὴν τῆς ψυχῆς αὐγὴν εἰς αὐτὸ ἀποβλέψαι

487 and, figuratively, Pl. Rep. 540a6–8 καὶ ἀναγκαστέον ἀνακλίναντας τὴν τῆς ψυχῆς αὐγὴν εἰς αὐτὸ ἀποβλέψαι  πᾶσι ϕῶς παρέχον. The metaphor from the ‘rays’ or ‘beams’ of one’s eyes (LSJ s.v. αὐγή 1, 5) is clearest where ὀμμάτων (-ος) is added: Ai. 69–70 (with Finglass), HF 132, Phoen. 1564, E. fr. 397a (above), Licymn. fr. 771.2 PMG and also Hec. 1102–5 Ὠαρίων ἢ Σείριος ἔνθα πυρὸς ϕλογέας ἀϕίησιν / ὄσσων αὐγάς.

πᾶσι ϕῶς παρέχον. The metaphor from the ‘rays’ or ‘beams’ of one’s eyes (LSJ s.v. αὐγή 1, 5) is clearest where ὀμμάτων (-ος) is added: Ai. 69–70 (with Finglass), HF 132, Phoen. 1564, E. fr. 397a (above), Licymn. fr. 771.2 PMG and also Hec. 1102–5 Ὠαρίων ἢ Σείριος ἔνθα πυρὸς ϕλογέας ἀϕίησιν / ὄσσων αὐγάς.

τορῶς: 77n.

738. Τρώων: Diggle for Τρωϊκῶν (Ω), since internal correption of a long vowel or diphthong – except with comic αὑτηί, τουτῳί, ἐκεινηί and the like (West, GM 12; cf. J. W. White, The Verse of Greek Comedy, London 1912, 367) – would be unacceptable in Attic drama. Hermann (Opuscula III, 307) had already written Τρῴων, but the genitive of the people’s name is regular with ἄναξ in this sense: e.g. Rh. 406–7 μέγαν /  ἄνακτα, Sept. 39 Καδμείων ἄναξ, A. Suppl. 328, 616, S. El. 482–3, Alc. 510.

ἄνακτα, Sept. 39 Καδμείων ἄναξ, A. Suppl. 328, 616, S. El. 482–3, Alc. 510.

740. τὸν ὑπασπίδιον κοῖτον ἰαύει: Metre and syntax are almost identical with Ai. 1408 τὸν ὑπασπίδιον κόσμον ϕερέτω (the body-armour) from the difficult anapaestic ending of that play (see Finglass on 1402–20, 1416–17, 1418–20). Direct borrowing is further suggested by the general rarity of ὑπασπίδιος (Il. 13.158, 807, 16.609 … ὑπασπίδια προποδίζων / προβιβάντι / προβιβάντος, Asius fr. 13.7 GEF … ὑπασπίδιον πολεμιστήν), which here must mean that Hector passed the night fully armed under the cover of his shield: cf. 20–2, 123–4 (nn.). Likewise Od. 14.479 (of a Greek ambushing party caught in bad weather) εὗδον δ᾽ εὔκηλοι, σάκεσιν εἰλυμένοι ὤμους and, with the shields as head-rests, Il. 10.150–2 βὰν δ᾽ ἐπὶ Τυδείδην Διομήδεα· … / … ἀμϕὶ δ᾽ ἑταῖροι / ηὗδον, ὑπὸ κρασὶν δ᾽ ἔχον ἀσπίδας.

κοῖτον ἰαύει combines two other essentially epic words. κοῖτος (‘bed, sleep’) is first and extensively attested in the Odyssey (cf. Hes. Op. 574), but in other drama occurs only at A. fr. 78c.7 (Theoroi?) ]ῳ τε  καὶ

καὶ  The original sense of ἰαύω, ‘pass the night – in sleep or wakefulness’ (LfgrE s.v. B 1; cf. 519–20n.), is also still

felt here, as in Ai. 1204 οὔτ᾽ ἐννυχίαν τέρψιν ἰαύειν. At HF 1049–50 τὸν εὔδι᾽ ἰαύονθ᾽ (Reiske: εὖ διαύοντα L) / ὑπνώδεά τ᾽ and Phoen. 1537–8 δεμνίοις / δύστανος ἰαύων it simply means ‘rest in bed’.

The original sense of ἰαύω, ‘pass the night – in sleep or wakefulness’ (LfgrE s.v. B 1; cf. 519–20n.), is also still

felt here, as in Ai. 1204 οὔτ᾽ ἐννυχίαν τέρψιν ἰαύειν. At HF 1049–50 τὸν εὔδι᾽ ἰαύονθ᾽ (Reiske: εὖ διαύοντα L) / ὑπνώδεά τ᾽ and Phoen. 1537–8 δεμνίοις / δύστανος ἰαύων it simply means ‘rest in bed’.

741. διόπων στρατιᾶς: ‘(of) the army’s commanders’ (< διέπω, as in e.g. Il. 2.207  ὅ γε κοιρανέων δίεπε στρατόν). For the noun, restored here by Portus (Breves Notae, 71), cf. especially Pers. 44 βασιλῆς δίοποι (with Garvie), again in recitative anapaests. It is elsewhere attested as A. fr. 232 (Sisyphus), E. fr. 447 (Hippolytus I)488 and, of a ship’s supervisor or captain (cf. A. fr. 269 ἀδίοπον), in Hp. Epid. 5.74.1 and 7.36.1 (ca. 350 BC). Although Aristophanes of Byzantium (fr. 338 Slater) and Ero-tian (δ 2 Nachmanson) classed the word as Attic, it may have carried an epic tone, given the verb from which it is derived.

ὅ γε κοιρανέων δίεπε στρατόν). For the noun, restored here by Portus (Breves Notae, 71), cf. especially Pers. 44 βασιλῆς δίοποι (with Garvie), again in recitative anapaests. It is elsewhere attested as A. fr. 232 (Sisyphus), E. fr. 447 (Hippolytus I)488 and, of a ship’s supervisor or captain (cf. A. fr. 269 ἀδίοπον), in Hp. Epid. 5.74.1 and 7.36.1 (ca. 350 BC). Although Aristophanes of Byzantium (fr. 338 Slater) and Ero-tian (δ 2 Nachmanson) classed the word as Attic, it may have carried an epic tone, given the verb from which it is derived.

742b–4. ‘… what someone has done to us unseen and then vanished, while the misfortune he has accomplished for the Thracians is plain to see.’

οἷά … ἀϕανῆ … ϕανερὸν / … πένθος: This chiastic juxtaposition has exact parallels in Hipp. 1286–9 Θησεῦ, τί  τοῖσδε συνήδῃ, / παῖδ᾽ οὐχ ὁσίως σὸν ἀποκτείνας / ψεύδεσι μύθοις ἀλόχου πεισθεὶς / ἀϕανῆ; ϕανερὰν δ᾽ ἔσχεθες ἄτην and E. El. 1190–2 ἰὼ Φοῖβ᾽, ἀνύμνησας δίκαι᾽ / ἄϕαντα,

τοῖσδε συνήδῃ, / παῖδ᾽ οὐχ ὁσίως σὸν ἀποκτείνας / ψεύδεσι μύθοις ἀλόχου πεισθεὶς / ἀϕανῆ; ϕανερὰν δ᾽ ἔσχεθες ἄτην and E. El. 1190–2 ἰὼ Φοῖβ᾽, ἀνύμνησας δίκαι᾽ / ἄϕαντα,  δ᾽ ἐξέπρα- / ξας ἄχεα (δίκαι᾽ Murray: δίκαν L, ἄϕαντα Elmsley: ἄϕατα L), whence we should not write ἀϕανής with Dobree (Adversaria II [1833], 87 = IV [1874], 85). For ϕανερὸν … πένθος cf. also Ion 945 ϕανερὰ … κακά, Phoen. 1513 τοιάδ᾽ ἄχεα ϕανερά and 1565 τῶν μὲν ἐμῶν

δ᾽ ἐξέπρα- / ξας ἄχεα (δίκαι᾽ Murray: δίκαν L, ἄϕαντα Elmsley: ἄϕατα L), whence we should not write ἀϕανής with Dobree (Adversaria II [1833], 87 = IV [1874], 85). For ϕανερὸν … πένθος cf. also Ion 945 ϕανερὰ … κακά, Phoen. 1513 τοιάδ᾽ ἄχεα ϕανερά and 1565 τῶν μὲν ἐμῶν  ϕανερὸν κακόν.

ϕανερὸν κακόν.

ϕροῦδος: 662n.

τολυπεύσας: literally ‘wind off, unravel’ (a skein of wool, τολύπη: Ar. Lys. 586, S. fr. 1102). Except for Od. 19.137 οἳ δὲ γάμον σπεύδουσιν· ἐγὼ δὲ δόλους τολυπεύω, where we have an allusion to Penelope’s web, the metaphor is already dead in Homer (Janko on Il. 14.85–7 … οἷσιν ἄρα Ζεύς / ἐκ νεότητος ἔδωκε  ἐς γῆρας τολυπεύειν / ἀργαλέους πολέμους; cf. Il. 24.7–8 and the verse-end formula … ἐπεὶ πόλεμον τολύπευσε(ν) / -α in Od. 1.238, 4.490, 14.368 and 24.95). The verb is very rare after Homer and adds yet another epicism to the Charioteer’s

lament (740, 741, 750–1a nn.). Similarly ἐκτολυπεύω (from [Hes.] Sc. 44?) at Ag. 1032–3 οὐδὲν ἐπελπομέ- / να ποτὲ καίριον ἐκτολυπεύσειν (with Fraenkel on 1033).

ἐς γῆρας τολυπεύειν / ἀργαλέους πολέμους; cf. Il. 24.7–8 and the verse-end formula … ἐπεὶ πόλεμον τολύπευσε(ν) / -α in Od. 1.238, 4.490, 14.368 and 24.95). The verb is very rare after Homer and adds yet another epicism to the Charioteer’s

lament (740, 741, 750–1a nn.). Similarly ἐκτολυπεύω (from [Hes.] Sc. 44?) at Ag. 1032–3 οὐδὲν ἐπελπομέ- / να ποτὲ καίριον ἐκτολυπεύσειν (with Fraenkel on 1033).

745–6. ‘Some evil seems to be falling on the Thracian host, according to what I understand from this man’s words.’

κυρεῖν … / ἔοικεν: Despite Paley (on 745), there is nothing exceptional about ἔοικα with a present infinitive (LSJ s.v. II 1). The latter, though perhaps slightly surprising after the aorist and perfect forms in 735 and 742–4, here seems to emphasise the lasting effects of the recent attack (Ammendola on 745–46) and point to further trouble ahead. Cf. Cho. 13 πότερα δόμοισι  προσκυρεῖ νέον (Orestes seeing Electra and the chorus in mourning). κυρέω with a personal dative is otherwise restricted to Sophocles: Tr. 291 ἄνασσα, νῦν σοι τέρψις ἐμϕανὴς κυρεῖ, OC 1289–90 καὶ ταῦτ᾽ ἀϕ᾽ ὑμῶν, ὦ ξένοι, βουλήσομαι / καὶ τοῖνδ᾽ ἀδελϕαῖν καὶ πατρὸς κυρεῖν ἐμοί.489

προσκυρεῖ νέον (Orestes seeing Electra and the chorus in mourning). κυρέω with a personal dative is otherwise restricted to Sophocles: Tr. 291 ἄνασσα, νῦν σοι τέρψις ἐμϕανὴς κυρεῖ, OC 1289–90 καὶ ταῦτ᾽ ἀϕ᾽ ὑμῶν, ὦ ξένοι, βουλήσομαι / καὶ τοῖνδ᾽ ἀδελϕαῖν καὶ πατρὸς κυρεῖν ἐμοί.489

οἷα depends on both  and κλύων. The clause is causal-exclamatory in origin (cf. 309–10n.).

and κλύων. The clause is causal-exclamatory in origin (cf. 309–10n.).

747–9. ἔρρει στρατιά: similarly Pers. 732 Βακτρίων δ᾽ ἔρρει πανώλης δῆμος.

δολίῳ πληγῇ: The adjective suggests Odysseus’ agency (893b–4n.). Feminine δόλιος mostly stands for metrical reasons: Bacch. 17.116 δόλιος Ἀϕροδίτα, Cyc. 449, Tro. 530, IT 859 (δόλιον Hartung: δολίαν ὅτ᾽ L), Hel. 20, 238, 1589. But see Alc. 33–4 Μοίρας δολίῳ / σϕήλαντι τέχνῃ, where, as here, euphony may have played a part (cf. Kannicht on Hel. 335).

On Euripides’ fondness for using three-termination adjectives with two terminations see further W. Kastner, Die griechischen Adjektive zweier Endungen auf -ΟΣ, Heidelberg 1967, especially 95–99, 114 and Diggle, Euripidea, 167, 186, 262.

ἆ ἆ ἆ ἆ: a cry of physical anguish as in 799 ἆ ἆ (extra metrum) and, again fourfold, Phil. 732 and 739. On the different denotations of the interjection – urgent protest, astonishment (HF 629, Ba. 586, 596), mental distress (A. Suppl. 162, Ag. 1087) – see the works cited in 687n. and also Dodds on Ba. 810–12, E. Schwentner, Die primären Interjektionen in den indogermanischen Sprachen … , Heidelberg 1924, 7, Ll-J/W, Second Thoughts, 66.

750–1a. ‘How the pain of my bloody wound afflicts me deep within!’

The expression is partly repeated in 799 (n.) ὀδύνη με τείρει κοὐκέτ᾽ ὀρθοῦμαι τάλας. It recalls Il. 15.60–1  δ᾽ ὀδυνάων / αἳ νῦν

μιν τείρουσι κατὰ ϕρένας, Od. 9.440–1 ἄναξ … ὀδύνῃσι κακῇσι / τειρόμενος, Ar. Ach. 1205 ἰὼ ἰὼ τραυμάτων ἐπωδύνων, Hipp. 1351 διά μου κεϕαλῆς ᾄσσουσ᾽ ὀδύναι and 1370–1 αἰαῖ αἰαῖ· /

δ᾽ ὀδυνάων / αἳ νῦν

μιν τείρουσι κατὰ ϕρένας, Od. 9.440–1 ἄναξ … ὀδύνῃσι κακῇσι / τειρόμενος, Ar. Ach. 1205 ἰὼ ἰὼ τραυμάτων ἐπωδύνων, Hipp. 1351 διά μου κεϕαλῆς ᾄσσουσ᾽ ὀδύναι and 1370–1 αἰαῖ αἰαῖ· /  νῦν ὀδύνα μ᾽ ὀδύνα βαίνει, which is also followed by a wish for death (1372–7, 1385–8). Cf. 728–55n.

νῦν ὀδύνα μ᾽ ὀδύνα βαίνει, which is also followed by a wish for death (1372–7, 1385–8). Cf. 728–55n.

ϕονίου: a favourite of Euripides (cf. Liapis on 750–1), as Aristophanes seems to have recognised in Ran. 1337. See 41–2, 662nn. and Introduction, 29–30 with n. 36.

εἴσω should be taken absolutely (‘inside the body’), as in Pl. Rep. 407d4–5 τὰ δ᾽ εἴσω διὰ παντὸς νενοσηκότα σώματα and epic ἔνδοθι (ἐντός) of various deep feelings at Il. 1.243–4 σὺ δ᾽ ἔνδοθι θυμὸν ἀμύξεις / χωόμενος, 22.242 ἀλλ᾽ ἐμὸς ἔνδοθι θυμὸς ἐτείρετο  λυγρῷ, 10.10 τρομέοντο δέ οἱ ϕρένες ἐντός, Od. 2.315, 8.577, 19.377–8 and especially A. R. 3.761–2 ἔνδοθι δ᾽ αἰεί / τεῖρ᾽ ὀδύνη (Medea’s love-induced fear for Jason). Note also τὰ ἐντός, ‘the inner parts’ (LSJ s.v. ἐντός II with Suppl. [1996]), and Latin intus (TLL s.v. 103.52–76).

λυγρῷ, 10.10 τρομέοντο δέ οἱ ϕρένες ἐντός, Od. 2.315, 8.577, 19.377–8 and especially A. R. 3.761–2 ἔνδοθι δ᾽ αἰεί / τεῖρ᾽ ὀδύνη (Medea’s love-induced fear for Jason). Note also τὰ ἐντός, ‘the inner parts’ (LSJ s.v. ἐντός II with Suppl. [1996]), and Latin intus (TLL s.v. 103.52–76).

The only tragic parallel for this use of the adverb is Ag. 1343 ᾤμοι, πέπληγμαι καιρίαν  ,where scholars have long suspected corruption and Vetta (GIF 5 [1974], 162–4) in particular assumed the intrusion of a ‘didascalic’ gloss (cf. ΣB Med. 96 [II 149.16 Schwartz] τάδε λέγει Μήδεια ἔσω οὖσα). Yet with πληγῇ in 749 and another echo of Agamemnon’s death in 790–1 (n.), it is probable that our lines were also influenced by Aeschylus and that the passages hence support each other. Formulations like Il. 16.340 (~ 21.117–18) πᾶν δ᾽ εἴσω ἔδυ ξίϕος, E. El. 1221–3 ἐγὼ μὲν … / ϕασγάνῳ κατηρξάμαν / ματέρος

,where scholars have long suspected corruption and Vetta (GIF 5 [1974], 162–4) in particular assumed the intrusion of a ‘didascalic’ gloss (cf. ΣB Med. 96 [II 149.16 Schwartz] τάδε λέγει Μήδεια ἔσω οὖσα). Yet with πληγῇ in 749 and another echo of Agamemnon’s death in 790–1 (n.), it is probable that our lines were also influenced by Aeschylus and that the passages hence support each other. Formulations like Il. 16.340 (~ 21.117–18) πᾶν δ᾽ εἴσω ἔδυ ξίϕος, E. El. 1221–3 ἐγὼ μὲν … / ϕασγάνῳ κατηρξάμαν / ματέρος  δέρας μεθείς, Ion 767–8 διανταῖος ἔτυπεν ὀδύνα με πλευ- / μόνων τῶνδ᾽ ἔσω and Hel. 354–6 ἢ

δέρας μεθείς, Ion 767–8 διανταῖος ἔτυπεν ὀδύνα με πλευ- / μόνων τῶνδ᾽ ἔσω and Hel. 354–6 ἢ  διωγμὸν / αἱμορρύτου σϕαγᾶς / αὐτοσίδαρον ἔσω πελάσω διὰ σαρκὸς ἅμιλλαν are made easier by the genitive or verb of motion they contain (Denniston–Page on Ag. 1343, M. Vetta, GIF 5 [1974], 159–64, who both falsely join εἴσω with ϕονίου τραύματος here).

διωγμὸν / αἱμορρύτου σϕαγᾶς / αὐτοσίδαρον ἔσω πελάσω διὰ σαρκὸς ἅμιλλαν are made easier by the genitive or verb of motion they contain (Denniston–Page on Ag. 1343, M. Vetta, GIF 5 [1974], 159–64, who both falsely join εἴσω with ϕονίου τραύματος here).

751b. πῶς ἂν ὀλοίμην; another topos in anapaestic laments (cf. 733n.). So also Alc. 864, Med. 97 and, more expansively, E. Suppl. 795–7 μελέα / πῶς ἂν ὀλοίμην σὺν τοῖσδε τέκνοις / κοινὸν ἐς Ἅιδην  ; (Ritchie 211). For desperate ‘wish-questions’ with πῶς ἄν see 869n.

; (Ritchie 211). For desperate ‘wish-questions’ with πῶς ἄν see 869n.

752–3. The sentiment is further developed in 758–61 (n.). As in 733 (n.), the Charioteer puts himself before his master, no matter that the order μ᾽ … Ῥῆσόν τε is dictated by Behaghel’s Law of Increasing Terms.

ἀκλεῶς: likewise 761 (n.). Earlier tragic instances of ἀκλεῶς and its adjective all belong to Euripides: Or. 786 ἰτέον, ὡς ἄνανδρον ἀκλεῶς κατθανεῖν, Hcld. 623–4 ἀκλεής … δόξα, Hipp. 1028, IA 18 (if genuine). It is not clear whether fr. tr. adesp. 665.21 comes from a fourth-century or much later imitation of Euripides (Kannicht–Snell, TrGF II, 251–2).

Τροίᾳ κέλσαντ᾽ ἐπίκουρον: ‘… after he had landed in Troy as your ally’. In view of the verbal affinities with E. El. 135–9 ἔλθοις δὲ πόνων … / … λυτήρ, /… πατρί θ᾽ αἱμάτων /  ἐπίκουρος (‘avenger’), Ἄρ- / γει

ἐπίκουρος (‘avenger’), Ἄρ- / γει  πόδ᾽

πόδ᾽  (where κέλλω is uniquely transitive in tragedy: FJW on A. Suppl. 330–2), it seems preferable to take Τροίᾳ here with κέλσαντ᾽ rather than ἐπίκουρον (Kovacs, Liapis on 752–3). Elsewhere in Rhesus the verb has its regular construction with a prepositional phrase or an accusative of direction (895–8, 934–5a nn.).

(where κέλλω is uniquely transitive in tragedy: FJW on A. Suppl. 330–2), it seems preferable to take Τροίᾳ here with κέλσαντ᾽ rather than ἐπίκουρον (Kovacs, Liapis on 752–3). Elsewhere in Rhesus the verb has its regular construction with a prepositional phrase or an accusative of direction (895–8, 934–5a nn.).

754–5. ἐν αἰνιγμοῖσι … / σαϕῶς: a very common antithesis in fifth-century and later literature: e.g. Ag. 1178–83 καὶ μὴν ὁ χρησμὸς οὐκέτ᾽ ἐκ καλυμμάτων / ἔσται δεδορκὼς … 1183b ϕρενώσω δ᾽ οὐκέτ᾽ ἐξ αἰνιγμάτων, PV 609–10 λέξω τορῶς σοι πᾶν ὅπερ χρῄζεις μαθεῖν, / οὐκ ἐμπλέκων αἰνίγματ᾽, ἀλλ᾽ ἁπλῷ λόγῳ, 833–5, IA 1146–7, Aeschin. 3.121 and, conversely, A. Suppl. 464 αἰνιγματῶδες τοὔπος· ἀλλ᾽ ἁπ<λ>ῶς ϕράσον, Alexis fr. 242.6–7 PCG, Anaxil. fr. 22.23 PCG, Pl. Ep. 332d6–7. Further examples in FJW on A. Suppl. 464.

As regards tragedy, αἰνιγμός (for αἴνιγμα) is unique to our passage save for Phoen. 1353 Σϕιγγὸς αἰνιγμοῖς, which is very probably part of an interpolation (see Fraenkel, Zu den Phoenissen, 83–4 [cf. n. 267] and Diggle’s apparatus on 1308 ff.). The first unquestionably genuine instance is Ar. Ran. 61.

σημαίνει κακά: an inflectable Euripidean verse-end: Hec. 512 … σημανῶν κακά, HF 1230 … σημαίνεις κακά, Ion 945 … σημαίνω κακά.

756–803. In a movement comparable to that employed in scenes where the same situation is presented first ‘emotionally’ in lyrics, then ‘rationally’ in dialogue verse,490 the Charioteer turns from his sung and spoken trochaics (728b, 732a) and recitative anapaests (733–5, 738–44, 747–53) to regular iambic discourse. Among tragic messenger speeches, however, his account of Rhesus’ death stands out for its extreme subjectivity (728–55n. with n. 268) and narrow perspective. Himself a victim of the nocturnal slaughter, he can only speak from direct perception and, with his failure to anticipate the attack (773–9), his belated and clumsy attempts to defend the camp (792–8) and his ignorance of the actual circumstances and perpetrators of the deed (800–3), he becomes the most obvious exponent in the play of human short-sightedness and inefficiency (Strohm 271–2, J. Barrett, Staged Narrative. Poetics and the Messenger in Greek Tragedy, Berkeley – London 2002, 189).

After a lengthy reflection on failed heroism harking back to 752–3 (756–7a, 758–61, 761, 762–3a nn.), the report proper confirms the return to the substance of Iliad 10, observed previously in the adaptation of Hippocoon’s lament (728–55n.). This manifests itself in the all but exclusive interest in Rhesus’ horses, which is certainly appropriate to the faithful Charioteer, but turns the king into little more than a source of splendid booty: Il. 10.463–4 ἀλλὰ καὶ αὖτις / πέμψον ἐπὶ Θρῃκῶν ἀνδρῶν  καὶ εὐνάς, 477–81, 488–501, 520 (cf. Burnett, ‘Smiles’, 34–5, Barrett, Narrative, 173).491 The temporary marginalisation of Rhesus in favour of his servant’s more immediate pathos is clearest in 780–8 (n.), the translation of Il. 10.494–7 into the only dream related by a ‘messenger’ on stage, and 790–1 (n.), where even his final moments appear as a grisly experience of the Charioteer (Barrett, Narrative, 181–2). Moreover, by a slight change in the Thracians’ attitude towards self-protection (762–9n.), our poet manages to combine a first hint at the narrator’s resentments against his hosts with a sense that Rhesus invited his fate.

καὶ εὐνάς, 477–81, 488–501, 520 (cf. Burnett, ‘Smiles’, 34–5, Barrett, Narrative, 173).491 The temporary marginalisation of Rhesus in favour of his servant’s more immediate pathos is clearest in 780–8 (n.), the translation of Il. 10.494–7 into the only dream related by a ‘messenger’ on stage, and 790–1 (n.), where even his final moments appear as a grisly experience of the Charioteer (Barrett, Narrative, 181–2). Moreover, by a slight change in the Thracians’ attitude towards self-protection (762–9n.), our poet manages to combine a first hint at the narrator’s resentments against his hosts with a sense that Rhesus invited his fate.

When it comes to his own foiled attack and injury (792, 793–5a, 797–8, 799nn.), the Charioteer reverts to his earlier penchant for epic language (740, 741, 742b–4, 750–1a nn.), as if to corroborate the Thracian’s lack of glory (756–61) by giving an ironic commentary on Homeric prowess. In addition, his groan at 799 almost literally takes up 749–51 and so reinforces the unique juxtaposition of message and lament.

756–61. Among introductions to tragic messenger speeches (284–6n.), the length and character of this passage are matched only by the Maidservant’s reflections on Alcestis’ excellence in Alc. 152–7. Both this woman and the Charioteer act as ‘substitute messengers’ and are in their respective ways perhaps more than usually affected by the incidents they are going to recount.

756–7a. ‘We have suffered a disastrous blow and, over and above disaster, disgrace as well.’

Construction and wording are almost identical with 102 (102–4n.) αἰσχρὸν γὰρ ἡμῖν, καὶ πρὸς αἰσχύνῃ κακόν. But in contrast to Hector, the Charioteer is more concerned with physical suffering and, as Liapis (on 756–7) observes, foregrounds it over heroic shame. This also distinguishes him from other major characters in tragedy, such as Eteocles in Sept. 683–5 εἴπερ κακὸν ϕέροι τις, αἰσχύνης ἄτερ / ἔστω· μόνον

γὰρ κέρδος ἐν τεθνηκόσιν· / κακῶν δὲ καἰσχρῶν οὔτιν᾽ εὐκλείαν ἐρεῖς, Iolaus in Hcld. 449–50  χρῆν ἄρ᾽ ἡμᾶς ἀνδρὸς εἰς ἐχθροῦ χέρας / πεσόντας αἰσχρῶς καὶ κακῶς λιπεῖν βίον and Cadmus in Ba. 1305–7 ὅστις … / τῆς σῆς τόδ᾽ ἔρνος, ὦ τάλαινα,

χρῆν ἄρ᾽ ἡμᾶς ἀνδρὸς εἰς ἐχθροῦ χέρας / πεσόντας αἰσχρῶς καὶ κακῶς λιπεῖν βίον and Cadmus in Ba. 1305–7 ὅστις … / τῆς σῆς τόδ᾽ ἔρνος, ὦ τάλαινα,  / αἴσχιστα καὶ κάκιστα κατθανόνθ᾽ ὁρῶ.

/ αἴσχιστα καὶ κάκιστα κατθανόνθ᾽ ὁρῶ.

κακῶς πέπρακται: likewise Med. 364 κακῶς πέπρακται πανταχῇ· τίς ἀντερεῖ;

πρός after κἀπὶ τοῖς κακοῖσι is redundant and probably not more than a convenient verse-filler (Fraenkel, Rev. 238). Elsewhere this particular use of adverbial πρός is restricted to the phrases πρὸς δ᾽ ἐπὶ τοῖς (A. fr. 146a) and καὶ πρὸς ἐπὶ τούτοις (Ar. Pl. 1001, Anaxil. fr. 24 PCG).

757b. ‘And this is an evil twice as great.’

A similarly formulated question is asked by Tecmessa at Ai. 277 ἆρ᾽ ἐστὶ  δὶς τόσ᾽ ἐξ ἁπλῶν κακά; meaning that Ajax, relieved from his madness, has started to torment himself as well as his family.

δὶς τόσ᾽ ἐξ ἁπλῶν κακά; meaning that Ajax, relieved from his madness, has started to torment himself as well as his family.

καίτοι: ‘logical’, marking the transition from minor to major premise in an incomplete syllogism (GP 561–4, especially ii). The particle seems to have no adversative force here.

δὶς τόσον κακόν: 159b–60n.

758–61. The wish for a glorious death in battle, if die one must, is a heroic commonplace from Homer on (e.g. Il. 22.304–5) and often contrasted with the prospect or reality of a less favourable end that brings no honour to the family: e.g. Od. 1.234–43, 14.365–71, 24.28–34, Cho. 345–53 + 494, Andr. 1181–5 (cf. Garvie on Cho. 345–53, Liapis on 758–60). Despite Ritchie (227), there is thus nothing specially Euripidean about the sentiment here, although certain phraseological resemblances can be discerned (758, 759, 760, 761nn.).

758. εἰ θανεῖν χρεών: Versions of this conditional clause appear several times in Euripides: Hipp. 442 (~ HF 147, Ion 1120) … εἰ θανεῖν αὐτοὺς χρεών, IT 1004–5 … οὐδέ σ᾽ εἰ θανεῖν χρεών / σώσασαν, Phoen. [1745] … εἰ  καὶ θανεῖν … χρεών; cf. Cyc. 201 εἰ θανεῖν δεῖ, Hcld. 443 (~ Or. 50) εἴ με χρὴ θανεῖν. Aeschylus and Sophocles offer nothing of the sort, unless fr. tr. adesp. 626 (32 εἰ καὶ θανεῖν χρὴ … ) belongs to the latter.

καὶ θανεῖν … χρεών; cf. Cyc. 201 εἰ θανεῖν δεῖ, Hcld. 443 (~ Or. 50) εἴ με χρὴ θανεῖν. Aeschylus and Sophocles offer nothing of the sort, unless fr. tr. adesp. 626 (32 εἰ καὶ θανεῖν χρὴ … ) belongs to the latter.

759. On such strong subjective affirmations about the feelings or perceptions of the dead see K. J. Dover, Greek Popular Morality in the Time of Plato and Aristotle, Oxford 1974, 243, who quotes S. El. 400 πατὴρ δὲ τούτων, οἶδα, συγγνώμην ἔχει and E. El. 684 πάντ᾽, οἶδ᾽, ἀκούει τάδε πατήρ· στείχειν δ᾽ ἀκμή.

λυπρὸν μὲν οἶμαι: Ritchie (245–6) notes the syntactical similarity to the opening of Alc. 353–4 ψυχρὰν μέν, οἶμαι, τέρψιν,  ὅμως βάρος / ψυχῆς ἀπαντλοίην ἄν. Parenthetical οἶμαι (μέν) is more frequent in Euripides (also Alc. 565, Med. 311, 331, 588, Hcld. 511, 670,

968, Hipp. 458, El. 1124, Ba. 321, IA 392) than in all other extant tragedy together: Cho. 758 οἴομαι (spoken by the Nurse), PV 758, 968, Ant. 1051, Phil. 498, S. fr. 583.4. It mostly has a colloquial ring (Stevens, CEE 23–4, Collard, ‘Supplement’, 361).

ὅμως βάρος / ψυχῆς ἀπαντλοίην ἄν. Parenthetical οἶμαι (μέν) is more frequent in Euripides (also Alc. 565, Med. 311, 331, 588, Hcld. 511, 670,

968, Hipp. 458, El. 1124, Ba. 321, IA 392) than in all other extant tragedy together: Cho. 758 οἴομαι (spoken by the Nurse), PV 758, 968, Ant. 1051, Phil. 498, S. fr. 583.4. It mostly has a colloquial ring (Stevens, CEE 23–4, Collard, ‘Supplement’, 361).

πῶς γὰρ οὔ; ‘How could it not be?’, i.e. ‘of course’ (cf. GP 86). This is likewise at least conversational in tone and, especially in reply to a previous speaker’s words, exceedingly common in Plato. In tragedy it occurs in parenthesis at Cho. 753–4 (again from the Nurse’s speech) and S. El. 1307. Cf. also S. El. 911 πῶς γάρ; and perhaps OT 567, S. fr. 730e.5 πῶς δ᾽ οὐ(χί); (Collard, ‘Supplement’, 368).

760. καὶ δόμων εὐδοξία: For εὐδοξία with a possessive genitive cf. Sim. fr. 531.6–7 PMG = 261.5–6 Poltera ἀνδρῶν ἀγαθῶν ὅδε σηκὸς οἰκέταν εὐδοξίαν / Ἑλλάδος εἵλετο. In poetry the noun, but not its adjective, is virtually confined to choral lyric (also Pi. Pyth. 5.8, Nem. 3.40, Pae. 14.31 [fr. 52o Sn.–M. = S3 Rutherford]) and Euripides (Med. 627, Hec. 956, Suppl. 779, Tro. 643, possibly E. fr. 237.3); later only [Men.] Mon. 270 Jäkel. On εὐδοξέω see 496n.

761. ἡμεῖς δ᾽ ἀβούλως κἀκλεῶς ὀλώλαμεν: The formulation resembles Hipp. 1028  τἄρ᾽ ὀλοίμην ἀκλεὴς ἀνώνυμος and IA 17–18 ζηλῶ δ᾽ ἀνδρῶν ὃς ἀκίνδυνον / βίον ἐξεπέρασ᾽ ἀγνὼς ἀκλεής (752–3n.). Yet strictly speaking, ἀβούλως here is causal, ‘through (our own) foolishness’ (cf. S. El. 398 καλόν γε μέντοι μὴ ᾽ξ ἀβουλίας πεσεῖν), while ἀκλεῶς acquires an almost consecutive sense: ita ut inglorii simus (KG II 115, SD 414 c). The incomplete correspondence is mitigated by the unifying force of the privative prefix (Fraenkel on Ag. 412 [II, p. 217] and, for other such juxtapositions, Richardson on h.Cer. 200 [p. 221]).

τἄρ᾽ ὀλοίμην ἀκλεὴς ἀνώνυμος and IA 17–18 ζηλῶ δ᾽ ἀνδρῶν ὃς ἀκίνδυνον / βίον ἐξεπέρασ᾽ ἀγνὼς ἀκλεής (752–3n.). Yet strictly speaking, ἀβούλως here is causal, ‘through (our own) foolishness’ (cf. S. El. 398 καλόν γε μέντοι μὴ ᾽ξ ἀβουλίας πεσεῖν), while ἀκλεῶς acquires an almost consecutive sense: ita ut inglorii simus (KG II 115, SD 414 c). The incomplete correspondence is mitigated by the unifying force of the privative prefix (Fraenkel on Ag. 412 [II, p. 217] and, for other such juxtapositions, Richardson on h.Cer. 200 [p. 221]).

In view of the relative frequency of ἀβουλία and ἄβουλος (which Sophocles seems to like), ἀβούλως is surprisingly rare in fifth-century literature: Hdt. 3.71.3, Pherecr. fr. 152.6 PCG, Hcld. 152 (Kirchhoff: ἀβούλους L); cf. Hdt. 7.9β.1 ἀβουλότατα. After our passage it does not recur until Polybius and Diodorus Siculus.

762–9. The Charioteer freely admits to their neglect of basic emergency precautions, which at last betrays Rhesus’ gullibility and utter incompetence as a military leader. The somewhat reproachful tone in 767b–9a (as if the Trojans alone had failed to protect their auxiliaries) foreshadows his later accusations and probably mirrors Dolon’s misgivings at the lack of allied night-watches in Il. 10.420–2. The epic Thracians, however, have arranged their weapons and horses in perfect order (Il. 10.471–3 οἳ δ᾽  καμάτῳ ἀδηκότες, ἔντεα δέ σϕιν / καλὰ παρ᾽ αὐτοῖσι χθονὶ κέκλιτο εὖ κατὰ κόσμον, / τριστοιχεί· παρὰ δέ σϕιν ἑκάστῳ δίζυγες ἵπποι) and even the goads (766b–7a n.) are in their proper place: Il. 10.500–1 (Odysseus drives Rhesus’ team with his

bow) ἐπεὶ οὐ μάστιγα ϕαεινήν / ποικίλου ἐκ δίϕροιο νοήσατο χερσὶν ἑλέσθαι.

καμάτῳ ἀδηκότες, ἔντεα δέ σϕιν / καλὰ παρ᾽ αὐτοῖσι χθονὶ κέκλιτο εὖ κατὰ κόσμον, / τριστοιχεί· παρὰ δέ σϕιν ἑκάστῳ δίζυγες ἵπποι) and even the goads (766b–7a n.) are in their proper place: Il. 10.500–1 (Odysseus drives Rhesus’ team with his

bow) ἐπεὶ οὐ μάστιγα ϕαεινήν / ποικίλου ἐκ δίϕροιο νοήσατο χερσὶν ἑλέσθαι.

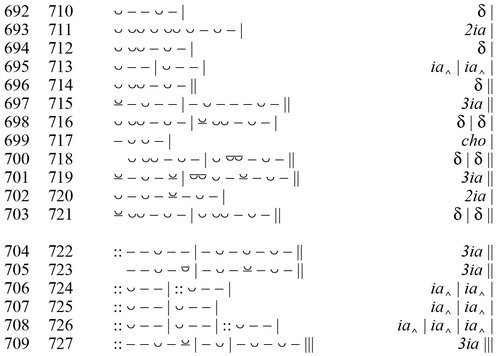

Rhesus here appears to have influenced Verg. Aen. 9.316–19 passim somno vinoque per herbam / corpora fusa vident, arrectos litore currus, / inter lora rotasque viros, simul arma iacere, / vina simul (cf. Introduction, 45).