Sketch 3

In which I start on my own account

THE NEW SETTLEMENT is at a sufficient distance inland for the inhabitants to have no sense of being connected to the sea. You leave your ship of passage and trail inland far enough to preclude any sudden change of mind, any second thoughts about whether this is where you want to be. You are committed, once you are here. That is a nice variation, perhaps not all that significant in the end, from the practice in the older Australian colonies. The key difference is that in going to those other destinations you are committed ahead of time.

However, it is not really all that far from the coast. You can still see the flat blue gulf from various places about the infant township. Here are enough glimpses of the sea to keep the experience poignant; and, I might add, enough glimpses to have teased the first planners to contemplate digging a canal all the way in from the port. It remains a puzzle how they thought to keep it filled with water.

There is so much that is interesting, though, that before long you forget those long views. What an extraordinary place this is. The town has been planned out, with regular wide streets and spaces for town squares, and the whole is surrounded by open bushland that already looks somewhat like an extensive park: stands of trees amid plenty of grass, a few shallow creeks—little more than ditches really—on a level plane, all ready made for riding about. Trees standing in the middle of where roads are to be. You have to cast further afield for hunting, for kangaroos mainly. That can be great sport, if you have a good horse to dash after your game, and a pack of dogs. The country towards the quite attractive range of hills, the Tiers as they are being called, is more heavily treed, almost a forest. There are plenty of duck along the main watercourse, and different kinds of parrots and pigeons and other birds to shoot, and fish to catch.

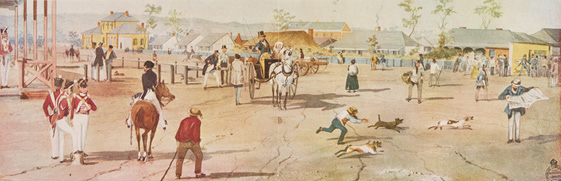

Where the streets are, or where they have been planned, inconvenient trees are being grubbed out, though the road surface has not settled back as evenly as could be wished. A few carriages are to be seen, and many more drays and wagons. Building goes on apace everywhere. Already the Governor’s house stands at one end of the main thoroughfare, in what will be extensive grounds overlooking reed beds and a rudimentary ford across the little river leading down towards where I saw the native camp. It is what one hopes might one day become picturesque, a kind of promissory note towards a view.

Along the line of the main roads are rather more fine-looking establishments and cottages than I expected to see. Some of these had been shipped out from England in bits and pieces and assembled; even the glass for the windows had survived the journey intact, though doubtless the exceptions to that are lying about among the spoil at Port Misery. Some have been built of bricks, likewise imported. Some are of weatherboard. The components of a ready-made church were thoughtfully sent out; but at its first assembly, there was a dismaying revelation. The boards did not fit together, and the struggles of the workmen to trim and cut corners put into my mind that, even in the brave new world, old Job was worth remembering: except the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it. As happens when there be too many trimmers.

We have a good many locally wrought chapels and meeting places too. The new Governor, Colonel Gawler, would like to have attended them all, being a man with a kind of religious frenzy. My father would have fancied his chance at being the Governor’s man. More to my taste is a similar plenty of drinking establishments; watering holes as the bullock drivers call them, some fifty or so, it is said. Most commonly they dispense spirits, as a direct counterpoint to those other places where the spirit gathers together, though my father would not thank me for the facetiousness. There is not yet much in the way of local brewing; in the meantime the publicans have had the foresight to ensure imported deliveries of bottled beer.

Less impressively, or impressive in quite another way, are a good many huts made of wattle and daub, mud huts really—the colony’s newspaper was at first printed in one such. Some of the cabins are rough structures, thick slabs of bark braced together by saplings. Many of the taverns are of this temporary kind, until more permanent and substantial hotels are built. Which is again to raise the question: just when is the beginning? Has the colony begun yet or is its real beginning yet to come? Those first unsteady official steps through the sand and banks of drying seaweed at Holdfast Bay were undoubtedly an inauguration, but was that the commencement or should we await some kind of colonial establishment before we proclaim we have indeed arrived? Both the Resident Commissioner and the Surveyor-General had huts made of reeds; it can be no surprise that these accidentally burned down, to the great distress of both parties. Officials without an office.

And of course everywhere are tents, bell-shaped and perhaps with brave little flags at their tip, and sad to see, the first scratchings of tiny gardens in front, where the women have planted the cuttings they tended so carefully on the voyage, making sure the wrappings stayed moist, priceless mementoes from their father’s cottage garden. Given that the seasons are out of kilter here, I have no great expectation that the cuttings will flourish, nor the seeds they have brought with them either. Those plantings are a mark of great faith, or optimism, or desperation, that all will be well. And in what you might think of as the back garden of these temporary residences, makeshift pens for those chickens that survived the long passage by sea, but whose days are nevertheless surely numbered, which makes their fortitude pathetic. Dogs bound about, harassing the chickens and dashing hither and thither, and I regret to say some have so far recovered from their voyaging as to begin the jolly experiment of generating new cross-breeds. It is a scandal how they defy the official principles of orderliness and regularity.

Whole families live in these tents and marquees and huts and shelters while waiting to find more permanent lodgings or—and this is the sticking point for so many new arrivals—until the surveyor has pegged out the land they were allocated. The newcomers find what accommodation they can wherever they can, and the reserved park lands around the township are in fact in common use, not as the founders might have wished but by the common people notwithstanding, living as best they can in a higgledy-piggledy fashion, amid the litter that has gradually been accumulating amongst the wattle bushes, and the abandoned spoil where some person or persons unknown has been digging up rock for their own building ventures. The Governor has appointed constables to begin shifting the people from this unsightly site. Their encampment must have been particularly uncomfortable in the warm weather, which is to say much of the time. And the exasperation of the flies! You can never be free of them.

Even those with more solid dwellings live inside or close to Adelaide, waiting for the opportunity to take up their promised land. That has been the universal dream of all who have migrated here, that was what the advertisements tempted them with. The town lots were assigned in the first months of the settlement, to those who had bought an entitlement at the inauguration of the scheme, and what little was left over was soon snapped up. Now those lots are being sold on again, subdivided, at an increase in price. Rural selections are only just starting to become available, even for those who had bought land orders, the delay being because the countryside round about the settlement has yet to be properly surveyed. These indignant owners-in-waiting live in temporary quarters, which proves an unplanned drain upon their capital. Inevitably a good many have started speculating in property in and around the town; the price of land and labour and materials all spirals upwards, and quite contradicts the intended spirit of the new settlement, of available land. Available, apparently, only to those with the deepest pockets.

That was certainly not the case with me. I have had to set about finding my living, and while like any other young man I could readily have earned good wages as a general labourer, that did not appeal. Instead, once I had found myself a suitable lodging, I looked about for somewhere to set up a studio, and found such a place in one of the little lanes and alleyways that are gradually springing up all across the township, short cuts between thoroughfares just as in the ‘old country’, as some of the local people are remembering it—those who do not think of going back. As in the towns at home, so here these back streets attract out-of-the-way activities not considered altogether appropriate to the main traffic, and those who do not particularly seek out public notice. Which is not why I made my choice, though I concede there were adjacent conveniences and obliging company as desired (I am not thinking of the Wesleyan chapel); mine are engaging neighbours.

My studio is off a respectable street, and not far from where the main business activity appears to have concentrated itself. Having settled on the terms, I hied me to the office of the newspaper, no longer I should hasten to say in a mud cottage but in somewhat improved premises—or possibly I should correct that too, and say it had only one premise. As had we all: to make a living for ourselves. And from such signs as I can see, that is not altogether a sure thing. It also occurs to me that Mother England’s interest in the colony may not be entirely the same as ours.

I placed an advertisement in the Register, announcing myself to the world, or what passes for it here, thinking that would look most seemly. But in terms of actually bringing myself to the notice of the general public, it might have been just as effective, or even more so, to nail a poster to one of the trees around the town. To save money, or to reach a wider public, notices are fixed to trees here and there about the township. This is the local custom, for those wanting labourers or looking for servants who have suddenly become both independent and invisible, or those hoping to sell off inappropriate equipment they brought out with them—though why such goods would be more suitable for anyone else is an open question. In the absence of notice boards, and with no established market place as yet, certain trees seem to have been selected for this useful role; by which I mean that of course one can nail any information to any tree, but it would not necessarily be one that the people knew to look at. The original proclamation of the colony had been displayed in exactly that way, hammered to the arch of a big old bent gum tree down by the original landing site at Holdfast Bay; I suspect that not too many people have been to look at that either, as it is somewhat out of the way.

That proclamation happened before it was determined just exactly where the township was to be. Or more precisely, before Governor Hindmarsh accepted the recommendation that it be inland; for he had been firmly opposed to such a selection. Let me say something of the late Governor, late in the sense that he is no longer with us. He was a Navy man through and through; and as his most glorious moments had been on the quarterdeck, he had never really stumped down from that elevation, making him a little difficult to engage in conversation.

He differed very strongly from the Surveyor-General about where actually everyone was to settle. His preference of course was that he be able to step off his ship and into his new office; and perhaps conversely, that he be able to scuttle quickly right back on board again, should the need arise. As in fact proved the case, in the end. He could see no advantage in carrying goods for several miles inland, especially over such straggling unmade tracks. He had a point, as each of us in our turn has experienced. But in actual fact other discontents underlay this part of the settlement’s inauguration, which should come as no surprise, given the ambitions of so many men.

Captain Hindmarsh was not shy of being recognised as a decorated hero. He had fought at the Battle of Trafalgar, amongst other famous engagements, and had been over-zealous in imitating his hero, Admiral Nelson, by losing his sight in one eye. I have practised the effect of this. You may try it for yourself, walking about with one eye shut or with a patch over it. You keep on seeing just a bit of your nose on the edge of your field of vision. More to the point, you keep needing to screw your head about, to see what is happening off the point of your shoulder—to see, for example, what your enemies might be doing, if only sneering. For Governor Hindmarsh had his enemies. By his reputation, he all but made a point of it.

He had come out on the Buffalo with quite an entourage aboard, not just his wife and daughters and servants, but a bevy of officials and a small squad of Marines and of course a good many migrating passengers too; but as well, he had an even more comprehensive farmyard aboard than I had travelled with—mules and pigs and a cow, turkeys and geese, all his own personal property. His dogs had the freedom of the decks and made a perfect nuisance of themselves; and so concerned was the Governor for the wellbeing of his livestock, an admirable husbandman in this respect, that he reduced everybody’s water allocation to ensure his animals did not want. Not all the passengers found that action commendable. The ladies did not care for the bucolic stench, nor for the crowded conditions, nor for Captain Hindmarsh’s temper. The Governor rose to the occasion and remained impervious. Be damned to them.

His temper was not helped by the galling proximity of an equally impervious gentleman, Mr Fisher, the Resident Commissioner appointed by the South Australian Colonisation Commissioners; the one as suave as the other was choleric, one just as aware of all those capital letters as the other was of naval honours.

What a bizarre arrangement that was. The South Australian Company and the colonial government. Captain Hindmarsh, accustomed to command without question, was to be hemmed in by the Commissioners’ agent. Mr Fisher had his own authority, his own sealed orders giving him special powers, and there was a great deal of one party making a point of not getting in the other’s way all the long journey from Portsmouth, the ladies carefully twitching aside their flowing skirts, the gentlemen looking out to the sea in opposite directions. It amused Mr Fisher to take up his place on Governor Hindmarsh’s wrong side, so that the Governor could not always see where he was coming from although he could sense the hidden activity. Which is, you would have to think, a decided liability in political life. But that is the legal mind for you. The two whiled away the longueurs of travel by arguing about their respective authority—it had come as something of a shock to the Governor to find that he had serious competition.

The authorities in London may have thought this strategy would produce an effective set of checks and balances, a very desirable end, given the reported tendency to independent activity by the governors in the other Australian colonies. In fact it did nothing of the kind, or rather it delivered so many checks that the whole colony was paralysed. The council appointed to oversee the everyday affairs of the settlement, to decide on the names of streets, for example, became a venue for continuing those vigorous shipboard exchanges. The two gentlemen in question could agree about nothing. Mr Fisher, pointedly exercising his authority, had refused the Governor permission to use the Commissioner’s bullock cart to carry his effects to where the new settlement was to be, which in part explains his Excellency’s crankiness about its eventual location. Once there, the Governor extended his garden into the park lands, Mr Fisher objected, an anonymous letter appeared in the Register critical of Mr Fisher (the editor just happening to be the Governor’s secretary) and those of Mr Fisher’s party undertook to establish a second, alternative newspaper.

The Governor suspended the Colonial Secretary and along with him an emigration agent, mostly to show that he could, and to spite the council. He had taken to replacing some of those on the original council by young gentlemen who showed a partiality to any of his daughters; though as there were only three of these he failed to generate a majority. The Commissioner issued a handbill announcing that the agent, Mr Brown, still held authority as he acted for the Colonisation Committee. Captain Hindmarsh issued a proclamation refuting that announcement as stuff and nonsense, and demanding loyalty to his own office, meaning by that to himself. So much huffing and puffing, so much excited importance. And so many urgent reports back to London. It was all as earnestly ludicrous as in a novel. This was clearly no way to establish a colony.

Eventually the Colonial Office acted because it had to, because it had failed to in the first instance. Governor Hindmarsh was recalled, and another was sent out in his place, Governor Gawler, who disapproved of the Surveyor-General, Colonel Light, just as his predecessor had, but for quite a different reason. Colonel Light maintained a mistress. And Colonel Gawler is a pious man, a very teapot of respectability, intent on being well liked of course, by the right sort of people preferably; and just as intent as his predecessor on hunting for a knighthood.

He did not approve. Rather than employ the original Surveyor-General, rather than countenance his very public private arrangements, the Governor preferred to carry out those duties himself, the public ones, until an appropriate appointment could be made. His has been a valiant if foolhardy resolve. He spends more time out and about than he could have anticipated, which cannot be comfortable, for he damaged his knee in the war with Napoleon. Which evidently is hardly as romantic as Captain Hindmarsh’s eye.

He has had a further difficulty, in that the Resident Commissioner has also been removed from his office, or perhaps it was actually the other way round and the office was removed from the Commissioner. The difficulty here has been compounded by having at close quarters a gentleman formerly accustomed to a certain kind of esteem, and likewise accustomed to arguing with the Governor, now no longer having anything much to do to keep himself from public mischief. Mr Fisher has had more than ample time to attend to a racetrack he has been clearing, using as labourers those recent arrivals who required official assistance. It would be most unseemly to suggest that his concern for them has been anything other than high minded. And there can be no doubt that we merit a Turf Club, given the popular support for his January race meetings, though the horses themselves are such a very mixed lot, some straight off the farm, some shipped bravely from Van Diemen’s Land, some still wild and rangy, having come overland with the droving mobs from New South Wales. Patently there are none here as yet that warrant their owners paying me to paint a likeness.

The solution of what to do with Mr Fisher is one which sets I believe an unfortunate precedent. He has had to be found something to acknowledge his stature, he must be provided with some apparently meaningful distraction; though he has been giving every impression that he is eminently capable of looking after his own interests and enthusiasms. He has been made the Mayor of Adelaide. That is a convenient arrangement, perhaps even one might suspect an ingenious one. He is said to be the first mayor anywhere in Australia, and it soothes him mightily to be the first of anything in all the land. Pre-eminence rests on him easily.

I must have come to official attention through my paintings of Adelaide streets, including one or two in which the approach to Government House features very prominently, and which evidently the Governor liked well enough when they were brought to his notice. Or at least I imagine that it was through some such connection that I received an invitation to an official reception, for I would by no means have thought myself among the Government House set, if I may so call them, the Nobs and Snobs of the town. For on the whole the effect of my advertising myself in the newspaper has been a great disappointment. There appears to be very little call for portraits, nor paintings of favoured dogs or horses. In the absence of custom, and with more than sufficient time on my hands, I have been turning my attention to painting a number of street scenes, some of which have been displayed in the window of a music shop, some of which I sent off back to England, to friends and relatives; and some which have been printed in the newspaper.

I am not altogether well pleased with them myself. There is difficulty in giving any sense of all this turbulence going on at the very centre of the settlement’s arrangements. So much busy jostling and competition, and yet you would never know it from the look of dazzling quietness in the streets—bullocks nodding off in the sun, the residents doffing their hats to the ladies, standing to one side and ceremoniously bowing, horses at a walking pace, having done their dash coming in through the outskirts of the town. All is sunny and sedentary, if not soporific. It looks like every day is Sunday. It misrepresents the actuality.

And a different problem I see is all those straight lines, which undeniably exist—you don’t have to inspect the town plan to realise that. They are like some kind of grid imposed on what I see as the real landscape of this place; perspective lines of awkward prominence. So that I cannot think that what I have depicted is altogether satisfactory. I have been searching for a way of softening those hard if very proper delineations.

But apparently the Governor has had no such reservations, or maybe he likes the Sunday look of things. Like his predecessor, he has armed himself with a wife, and a bevy of daughters aspiring to eligibility, and they require to be amused at something more sparkling than a picnic. He has been busy with a new Government residence, of twelve rooms necessarily, though his good lady still speaks of it as a pretty enough cottage. It is one of the Governor’s new public works, far superior of course to the original limestone thatch-roofed barn of a place which his predecessor’s Marines had contrived. From time to time the Governor obliges with public entertainments and issues invitations to those whom he wishes not to offend, to those young enough and enthusiastic enough to amuse his daughters, and to those like myself who cannot fail to disappoint by their awkwardness and inadequacy. Those of the Company’s persuasion and moral convictions tend, like my father, to be uncomfortable with such social engagements as dancing, whether vice-regally ordained or not. In fact, as I look back on him, there was much my father was unhappy about. Or to turn it another way, he was never happier than remembering ‘Thou shalt not’. A man of prohibitions and inhibitions. But I am diverting myself ahead of the official diversion.

I had of course to borrow a hat for no better purpose than to hand it in, together with a pair of gloves, on arrival. I had to make an appearance after all—clothes maketh the gentry. My name was called, and there was appropriate bowing and scraping, and then there in the ballroom were His Excellency’s daughters all in a tight huddle, which tended to make them somewhat unapproachable, agitated and fanning themselves vigorously, looking about the room and no doubt hoping—ah, forlorn hope!—that Mr Eyre, who is very fond of dancing, would not bother them. I have already observed Mr Eyre about the town. A gaunt beanpole of a man, he steps out through the streets at a furious pace, striding like a pair of ladders. He had won admiration for bringing a herd of cattle and a large flock of sheep overland from New South Wales, and has set up his own saleyard. Stock is now going to be much easier to acquire, and the pasture land around Adelaide can be put to more generous use.

He has just returned from stalking through the remote recesses of the northern interior, and his reports of that landscape are not encouraging. He is an excessively vertical young gentleman, very nice, if earnest and self-aware. As you would need to be when your head is in danger of knocking the wall candles out of their sconces. You can imagine the difficulty in keeping up with him as he weaves his way through the sets of dancers. He has to keep bobbing his head, to avoid the overhead lighting and decorations—he does so with aplomb, of course, but he progresses like an elongated emu. The only comfortable way to speak with Mr Eyre is to ask him to sit down. And even then, when he has balanced his tea cup on his knee, the wonder is that he can reach so far as to take it up again. I do not compete in the gallant stakes; I am better disposed to hover about the refreshment tables.

Another who was present was Mr Gilles. Mr Gilles has also previously held a Company office, as the Treasurer of the Colony, and was another whom the current Governor has had to treat very circumspectly; he too came out on board the Buffalo, and had been uniquely loyal to Captain Hindmarsh as well as to the Company. He had a vested interest in both sides; he wanted to make sure the scheme of settlement worked. But because Colonel Gawler wished to combine all powers and responsibilities under his own office, he had asked for Mr Gilles’s resignation—the Company men were all being put aside, one way or another. However, as Mr Gilles had lent the colony considerable funds from his own wealth, the government was still obliged to him. Indeed, the whisper is that the Governor himself may be indebted to old O.G., as he is known. Certain it is that nothing happens in this colony without Mr Gilles’s nod. It is not a good thing to have men who considered themselves powerful now with more time on their hands.

Mr Gilles in his first role had been well placed to develop his personal fortune; now he is amassing both land and wealth at a prodigious rate. It is all very well to be philanthropic, as from time to time he undeniably is, but first he is careful to ensure a sufficient basis of wealth from which to dispense his occasional largesse. He has his new silver and lead mine, he is importing sheep from Van Diemen’s Land, and he owns property everywhere. Because lately Wakefield and his followers have begun to turn their attention to New Zealand, the pattern of immigration and land purchase has changed, and O.G. is, so one sees, in exactly the right position to be a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles. On this occasion specifically, that means he took up his stand close to the refreshment booth.

Mr Gilles is not the sort of person you would invite if you were looking to enliven an occasion such as this. He has not a lot of conversation; he would not put himself out to make the effort. Short and rotund, the very opposite of Mr Eyre, he stands where he is with his hands in his pockets, his chin tucked into his cravat, blinking his watery little eyes and waiting impassively for others to make the conversation. He does not move very much at all. If he answers it is always in a very soft, quiet voice. With his absurdly high collar, he looks exactly like a coddled egg nestling down and being kept warm in its own cosy. You might wonder whether anything is happening inside that bland exterior, though it would be a sad mistake to do so, as several in this town can testify.

He is as strong in his religious belief as is the Governor. Possibly, if he thought it might be a competition, stronger. Yet I gather he has quite another reputation altogether, which the Governor chooses not to be aware of. I say nothing of his notorious temper. I wished I had about me my little sketch pad, but of course it would have been considered most improper for me to resort to my pencil in such company. And of course it may well have provoked Mr Gilles for one to show his famous irritability, so that it was no doubt just as well for once to be without the tools of my trade. Instead, I kept myself strategically close to the waiters, and withdrew only when I felt brave enough to do so, and before I had started to betray my newly acquired courage.

The settlement, or the township at its centre, is called Adelaide, after the late king’s German wife. Her name ought properly to be pronounced in the German fashion, but already one hears it being spoken of as Addle-layed, especially by those who did not come out to this new country in the more comfortable circumstances. Changes are taking place here, and it is amazing to observe the rapidity with which it is becoming a place of substance, and to watch the developing behaviour of the common people. Undoubtedly something has indeed already begun. I have mentioned that those who are employed as carpenters or masons or servants are all too liable to throw down their implements at a moment’s notice, and take off to the hinterland, or perhaps to one of the other colonies. They have not crossed the world to work for their betters—they had enough of that back home in England. Their dream is to be their own master. They are as free as any man, they claim, to do as they wish; sometimes that comes out as asserting they are as good as any man, and already you see that working men no longer raise their hat to anybody as they make their way down the street or along the roads out in the countryside. They are not truculent; they just insist on their independence, including independence of inconvenient customs and manners.

The Adelaide plains are very pleasant, but in summer the hot winds coming down across them from the interior dry everything out, and the only benefit is that the washing does not hang on the line for long. And yet, in the bright sunlight, on all that level ground, some men seem to believe they cast a longer shadow than others. I have been observing these shadows—it is a curious fact, the figures they throw have no necks. The heads are shaped like large eggs. The shadows of the trees are very sharp and precise, but the trees do not in fact afford much shade.

As for what the settlers themselves have achieved, there is such accomplishment in settlement as to be wholly surprising. At the same time, there is an extravagance of making do, of temporary accommodations to circumstance. There is for example no prison, though Governor Gawler is as busily rectifying that lack as he is building his own elegant house. When Governor Hindmarsh held office, prisoners—for alas, there were such offenders—were held in irons aboard the Buffalo. Amazing to think that in this colony of free settlers we had in effect our own prison hulk! But when he was recalled, he took his ship and his Marines with him, leaving the prisoners behind and no one to guard them, and there was no better choice than to put them into a large tent. Though for the first several nights they were chained to convenient tree trunks and logs.

My friends told me a ludicrous story about this. One prisoner, a bushranger who had come across from the eastern colonies, was chained up al fresco, with broken branches littered about as is usual with the local trees. See them there branches, said he, ’tain’t safe. That could do a man some mischief. They calls these here trees widdermakers. I s’pose I’ll be orlright though, says he, I bean’t married yet; nor won’t be for some time I dare say. By which reflection it seems that even here grey-cloaked philosophy is spreading its threadworn mantle.

In this makeshift, make-do world, for all the prominent straight lines of regulation, nothing yet has become fixed. And, one might add, little has been got right. The proclamation in the wrong place, or the settlement evolving at a distance from it, was a foretaste of other such dislocations, and to say the truth, other disappointments. There is no satisfactory supply of water—water carriers fetch supplies from the tepid ponds that constitute the Torrens. Yet in truth there is no alternative site for the settlement. The large river down which Captain Sturt had floated has no ready access to or from the sea, given the substantial sand bar across its mouth. Ideally the big river should have been nearer to the Tiers; or that range of hills should have been nearer to the river, but either way this is not quite the promised land puffed up by the notices enticing investment and emigration. Whichever way I look, I see the most endearing absurdities, the most engaging nonsense. Yet one might think of all those little inconvenient details as one way by which to soften the overdetermined lines of perspective.

At the same time, Addle-layed has its own peculiar charms: the small black-and-white magpies shrilling, the pink-and-grey parrots with their chipping call, the insane hooting of the giant kingfishers. The extraordinary sunsets, a mixture of pink and salmon and apricot and mauve. And at night, the startling intensity of the countryside lit by a huge full moon, and at a distance perhaps the campfires of the native peoples flickering through the bushes, their strange chanting and clapping and dancing. I believe I will find it in me to accept this place as my home.