Sketch 10

In which I eat humble pie

I QUITE LIKE THIS NEW LIFE. I have felt more assured than I did in Adelaide, where the cold hand of the bailiff seemed ever to be hovering over me. Here, it feels as though I fit in, or at least that I am on the way there. Or better again, that I blend in, like one of the figures in my paintings—and it would not be the first time that I have figured in my own record, my paintings I mean, for I fear I am too much in these jottings. In Melbourne I feel that I am just one among the many, and that suits me very well. I do not call attention to myself, and I am not ill at ease in my surroundings. I am finding a place that is in keeping with the way of life here; I am acquiring the colour of it.

And how that phrase speaks a story. The diggers are all looking for that elusive speck of colour in the clay and gravel washing about in their pans. They do not see that on the diggings they themselves are the colour. They are unaware of themselves, so absorbed are they with what is under their feet. Whereas I have found what promises to be my own little pot of gold, and all the scratching around I have to do is with my pen or pencil. I do not endure the bitingly cold wet nights, and I can keep out of the mud, well more or less, for Melbourne’s roads still leave somewhat to be desired.

The general public continues its very welcome fascination with pictures of the diggings, and the rumbustious ways of the diggers, preferring to view them at an aesthetic distance. They do not require portraits of themselves, apparently, or not from me. Diggers are still about the streets, showing off, but they now tend to hold their wild horse races in the streets at the upper end of the town; whereas those who pretend to gentility confine themselves to the elegances of Collins Street, and avoid as best they can any unfortunate encounter with the turbulent tearaways. That is not always possible, for the successful diggers like to parade their new wealth about the town, to impress the world that they are now every whit as good as their betters—which means they go seeking those they insist on impressing. Fortunately, their loud huzzahs announce their approach, and appropriate evasive action can be taken.

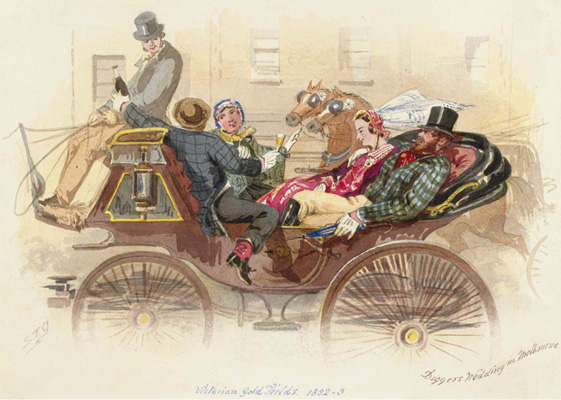

Such clamour sometimes announces the spectacle of a bridal party. A digger who has struck it rich might celebrate by getting married, and driving around the streets in the grandest carriage he can hire, even a landau, with coachman and four matching horses. Some young wag will have drawn a pair of hearts in the dust with his finger; or a prestigious coat of arms apt for the occasion in drying mud on the carriage door. A naughtier young fellow may improve it with a bend sinister. The proud new groom, the bridegroom that is, does not always remember to dress up in appropriate finery, nor his best man neither.

They lurch and sway about dangerously, waving their bottles of champagne, and the bride’s cheeks have a jolly flush. She is making the most of it; she has been made available for the occasion too, and her devoted hubby of the current few hours will be off back to the diggings at the end of the week. She will return to her work at a hotel until the next whiskery swain turns up, flushed with success, brandy and ardour. The digger is boasting that he is as good as the Nobs, and he has the money in his pocket to prove it, but alas, the effect is rather spoiled when his mate insists on offering the coachman a swig from his bottle. The driver knows how you are meant to appear in public, he knows the distinction between finesse and display.

And if he were so fortunate as to have another stroke of luck, the digger might well decide to get married all over again next time, not necessarily to the same young woman. Who is to say? Stranger things have happened.

The largest majority of those who have tried their luck at the diggings have had to come to terms with disappointment. The goldfields have not served them well, and they have had to make whatever kind of accommodation they can to altered circumstances, for the prices of everything have soared beyond all reason. With the great throngs of newcomers arriving on every tide, as it seems, food and lodging are expensive and difficult to come by, as is casual employment. And that makes for an undercurrent of anxiety and restlessness.

The pattern is that those who arrive first on a new field have the most success. The gold quickly becomes more and more difficult to find, the diggings more and more difficult to work, and so no field lasts long—there is always another rush to the newest strike, but those fresh discoveries are themselves becoming less frequent. The South Australian contingent has begun to abandon the fields in droves. They made the most of the early months and have taken their gold back to Adelaide with them, to pick up their old lives again. Yet another beginning for them. I wonder how many more times that will happen in the story of that young colony.

Whereas Melbourne seems to be bursting to get ahead. What a difference from when I first arrived, a year and more ago. The difference between then and now is like the change of stage scenery in one of the theatres. It has happened in such a short interval, and you almost cannot believe you are in the same place. In a manner of speaking it is not the same place. Then all was draggle-tailed, ramshackle and makeshift; not so very different, when you think about it, from the diggings. But now Melbourne town is intent on consolidating, or one might say solidifying, at much the same rate as the diggers are intent on undoing the countryside. Town and country are like the two ends of a balance: as one goes up the other goes down.

In the town, the main roads now have at least a properly formed central way, and a path on each side for pedestrians. There is still a sufficiency of mud to splatter crinolines and trousers; boots might set out clean but they never arrive in that condition, regardless of where they are going. The point is that there are now in fact a number of elegant destinations—dining rooms and exhibition halls, churches and theatres, superior shops and large commodious hotels, all in well-appointed buildings. Building is going on everywhere at a prodigious pace. The foundation stone for a new public library was laid on the same day as the foundation stone for a new university, very convenient for the governor’s coachman, as the one is just further up the road from the other. And, come to think of it, convenient for the spectators, as much the same group might be expected to present themselves at each occasion. A new hospital building has been commenced, a town hall, a steam railway with a railway station for it to start from and to return to.

Which is all well and good for those of us who live in the midst of this marvellous consolidation; all paid for from the splendid profits of the gold boom. But that does not wash well with the prospectors and the diggers, and the new chums who are left to make their own way up the country as best they can, over roads still unmade, and across rivers where there are no bridges, almost never a ferry, and no access down the steep banks. When the diggings start to form into little villages, there are still tree stumps in the middle of the main thoroughfares, the roads in and out are very often undermined by surreptitious tunnels, if the gold vein looks to pass beneath, and what with one thing and another, the diggers themselves see little in return for their monthly licence. Yet pity help them if they neglect to purchase it! Melbourne has no comprehension of their bitterness at the Governor’s neglect. Out on the diggings they never get to see him in his fancy uniform, laying a little mortar on a squared and polished foundation stone. He doesn’t come anywhere near them, not if he can help it.

The diggers do not mend matters. They leave an endless waste, streams turned out of their proper channels, creek banks broken and thrown aside, the very earth itself heaved upside down and inside out. Utterly undone. The whole countryside looks as though a rampaging army has invaded it, sacking and pillaging wherever it goes, violating and devastating the forests, wrecking whatever might happen in its way, and throwing away what is no longer of use. The litter and rubbish have to be seen to be believed; and I do not mean what gets tumbled down abandoned shafts.

After the diggers, nothing is ever the same again. There can be no putting to rights here. But demanding rights, ah, that is quite another matter. The diggers have their grievances about the licence. They have to pay for it as soon as they are on a declared field, and even the storekeepers and delivery men have to possess one, almost a leave pass. Which is not so very far from the old convict ways. Anybody found in want of that precious piece of paper can be marched off to a magistrate, fined five pounds and chained to the logs until the fine is paid.

The officiousness of the inspectors is irksome enough. The superciliousness of the commissioners is even more so, young fellows mincing about in fancy uniforms with gold braid, riding about attended by a trooper, and never where they are wanted; or rogues with questionable histories endlessly soliciting and receiving bribes. The diggers can be summoned out of their holes as often as a constable passes by, perhaps up to half a dozen times a day, and having to leave off their activity to clamber up the muddy shafts becomes an infernal irritation. So they call out to each other at the approach of the traps, and one or another of them might set off in a mad dash through the scrub, hurdling over felled logs like a thoroughbred, weaving in and out of copses like a hare, leaping creeks like a kangaroo until, cornered at last, he reaches inside his shirt and produces the demanded licence. Meanwhile, those of his mates who are without one have had ample time to take evasive action on their own account.

Not all that long ago, in Bendigo, the miners started to gather in large meetings to protest against the way the system is administered, and once they began to hear their own voice, stronger and stronger views were expressed, until a spirit of angry violence began to spread. Stirred up, they refused point blank to continue to pay their licence, and to show the strength of their numbers they took to wearing red ribbons as hat bands, many of them, but also tying them on the harness of their horses, or with deliberate rudeness, around their horses’ tails. They strongly resented the system where an informer could earn half the fine for pointing out those who had no licence—a temptation to some who had had no success on their own, or others’, claims. The diggers drew up a petition and all and sundry signed it, and marched in a procession to present it, in another demonstration of their united opposition.

That agitation on the Bendigo fields spread to the other diggings. Bungling Governor Bathrobe, more inept than can be believed, more gangling than Edward Longshanks, determined to double the fee for the licence, to pay for his public works in Melbourne as well as to increase salaries for all his minions; and in a panic at the outrage this stirred up, reversed his decision after just two weeks. Which might seem the action of a man who has seen reason. What in fact it showed is that he had made a severe and silly mistake, and that he could be made to back down. To the angry diggers it signalled his weakness, and though it would take some time for him to depart, that was the beginning of the end of him.

His next move was to propose to do away with the licence altogether; and then he revoked that revocation and imposed a revised schedule. He was well and truly in a quagmire. Each step he took was for the worse, and yet he was no better off if he stood still either. It looked like he did not know what he wanted. He was a ditherer.

Melbourne boasts two major newspapers, one desperately respectable in every expressed sentiment, the other forthright to the point of foolhardiness, particularly in its disapproval of the Governor. Each pretends to ignore the other, of course; between the two of them they cover most points of view. The most injudicious gossip circulates at the bars of the main hotels, just as in Adelaide and no doubt in every main town on the face of the earth. Between drinks thirsty men must empty their mouths, after all; and the more they drink the more unwisely they express their hidden thoughts, which is no little part of the pleasure of these establishments. In vino veritas, or whatever the Latin is for beer and spirits. It was at the bar of the Criterion that I heard that Governor Bathrobe had tendered his resignation, and that no one was much interested in replacing him. We were, of course. The Governor Designate apparently had much rather go elsewhere, to the Crimea if you please, than sail off to this far end of the earth, in order to take charge of a rabble of unruly diggers. He had to be persuaded to his duty.

Governor Hotham was in no hurry to arrive. He may have known something of what awaited him here; though in point of fact, the populace at large wished him well, and to demonstrate their goodwill there were floral arches across the roadways, and flags and bunting, as well as crowds lining the way to show him his route. But he had taken his time in getting here, a further two weeks later than first announced, and just as winter was settling in. So the crowds were a little less fervent than might have been the case, and a little more restive, stamping their feet and hugging themselves to keep warm. They just wished he would make his appearance. They had waited long enough.

On that day of days, when all were peeking and craning to see if he was coming yet, a sudden cheer and waving of hats and walking sticks and umbrellas began way down at the other end of the street and gradually grew louder—and then the object of all the cheering appeared, a digger on a scraggy horse galloping up well ahead of the official party and waving his hat to all and sundry. It raised a laugh, and while the new Governor was not amused when informed of it, that action had made the crowd more genial, and more inclined to a generous applause when the official carriage at last trundled into view.

The delayed arrival proved something of a feint on his part, a deceptive manoeuvre, for he is a most meticulous individual, a Navy man who insists on everything being just so, as though he is still in command of his ship. Her Majesty’s ship. Which is to say he does not make himself readily accessible; my guess is that like Hindmarsh he is too used to the exclusive privilege of his own quarterdeck. He is rigid in his adherence to the rules and regulations that have been established, and that has not boded well with the noisy demonstrations on the goldfields.

He has cut back on government expenditure, discovering that his predecessor had been spending more than could be accounted for. Shades of Grey. He will have regulation and order, which means he urges the constabulary to be more diligent than even before; and he will accept petitions only if they are formally worded memorials, following the proper procedures. Which ordinary men are not well acquainted with, usually. The leaders among the miners seem to be more capable of stirring up and inflaming strong views than of presenting a reasoned case; more given to demanding than to negotiating.

This was all the main topic of conversation in the Criterion and other hotels I dipped into from time to time; there is always talk about gold, of course, and where the latest rush is, and whether there are deeper deposits in the worked-out fields, and what to do with the gold once it is found, and how much of that wealth should go to the colony, and what it should be invested in, and so on and so forth. Which I have to say does not much hold my attention. I am more interested in the characters, and in recording the daily events at the diggings, and to that end I have made it my business to visit the different fields from time to time, to sketch and record whatever came to notice.

I have been back to Forest Creek, now called Castlemaine but still much the same place, and beyond it to Bendigo, as the diggers know it, or Sandhurst as the officials know it; and I have taken to visiting Ballaarat, travelling by way of the road through Geelong of course, as the route through Bacchus Marsh is a marsh in the better part of the year, and an impassable swamp for the rest of it. The northerly diggings are in long winding gullies, whereas Ballaarat is on more of a plain skirted by low hills, a flat as it is poetically called, prone to flooding after heavy rains. The route from Melbourne is well marked, with hotels at convenient intervals, at just about the stretch of a man’s thirst, and with favoured camping spots each at something like a day’s steady walk. Though you can now travel by coach if you wish—at a cost. Nothing comes cheap in this colony.

Ballaarat seems to be a more extensive field than the others, although it would be difficult to tell whether this is actually so, as the others are all tucked away in the branches of gullies, and in any case the population fluctuates according to where and when the latest strike has occurred. It is certainly more easily accessible than up toward Mount Alexander, and a high proportion of newcomers head in its direction. Close on their heels, so do the storekeepers and saloon proprietors and shanty owners, the butchers and bakers, and then soon enough barmaids and entertainers and boarding-house landladies.

And artists too. I am not the only one sketching and drawing. Some of us have looked to sell our sketches to the journals and papers in Melbourne, but some have been residents, for the time being, on the field and sold their drawings to the diggers. Ballaarat has a reputation for being a successful field for artists and diggers alike; that is to say, there are plenty of diggers with a pouch of nuggets, plenty of diggers with money to burn. I never saw that myself, but it is a common enough saying, that they will light their cigar with a five pound note, just because they can.

One artist I heard of, an Englishman, had trained in France and was said to be a better than average painter, of the kind you might see in a gallery. But because that requires very slow and careful work, it did not provide his daily bread. So he also drew quick sketches, but not of the kind that is commonly shown to the public. He had lived in Paris for several years as a student, and made a special study of drawing the human body in his life classes there, particularly the male figure. Perhaps for lack of the alternative on the goldfields, he returned to this subject, and in a very short time there was a clandestine market for his sketches; with some among the younger men rather too ready to sit for him. Or should I say pose, for the drawings circulated quickly among particular groups of the men, and not, I suggest, for artistic admiration alone. He did not stay long on the goldfields. He had no need to, as he rapidly made enough to establish himself in Melbourne, though whether he continued his French ways and his interest in the young men I cannot say.

It is endlessly interesting to see what men and women will turn to, to earn a living. In Ballaarat I like to call in at John Aloo’s pie shop, at a place called of all things Bakery Hill—his mutton pies are delicious, and reasonably priced. Though it occurs to me now, as I write this, that their interesting flavours may have derived from unspecified additional sources of nutrition. I have been content to enjoy them for what they are. Or what they are said to be.

John’s English is very limited, but sufficient for him to conduct his business. Curiously, whenever we enter his shop he shoos away his own countrymen, as being bad for his business; though perhaps they come again to his back door and eat their meals somewhere out there. You learn very little from John. His conversation is not much more than saying ver’ good, and smiling and nodding and rubbing his hands together; his version of bowing and scraping I suppose.

Most of his countrymen have no English at all, and so necessarily keep to themselves, but that seems to be their preference anyway. They mostly look for specks of gold in the tailings left behind by other miners, fossicking as it is called, in the mounds of yellow clay that are left everywhere. Who can say whether they make much from this effort? They have continued on the field, and that might mean they are sufficiently encouraged to keep on, or so unlucky that they cannot afford to return to their home villages. As has often been remarked, they are enigmatic. Which makes many of the diggers uncomfortable.

Mr Aloo, the inscrutable piemaker—the maker of inscrutable pies—has been keen to enter as far as he is able into community activities, to be seen to be joining in. That is good for his business too. I was surprised, as well as amused, to see him with a companion, perhaps a nephew, at the theatre. What he would have made of the production beggars the imagination. It was a performance of Hamlet, of all things. None of the fireworks and crackers with which the Chinese were used to amuse themselves in their own camps. Nor fierce dancing dragons neither, nor gongs. It was as different as could be from anything he might have experienced in his own homeland.

He would not have been at all able to follow from the lead of the audience, for it was a theatre full of rowdy diggers and their mates, all in colourful jumpers or shirts, though some made an effort and wore garish check coats, those who had found female companions for the evening and brought them along, all simpering and coquetting and displaying themselves. Perhaps that was good for business too. Fellows with enormous whiskers were calling out to acquaintances, and passing along a bottle of brandy. Some were standing up on their seats to speak with friends in the improbably named dress circle above them. Against all that hubbub, the play managed only with great difficulty to get under way. The orchestra, all five members of it, was in no danger of being heard.

And the play, ah yes, the play’s the thing. The ghost looked like he was wearing his wife’s nightgown, and attracted whistles from all across the audience for his troubles. Ribald remarks were made about the fact that young Ophelia seemed of much the same age as Hamlet’s mother, and there was much loud barracking at the swordfight between Hamlet and his opponent, Laertes I think. Bets were offered and taken up on the outcome. When the Queen swooned, a digger jumped up on the stage and offered her a reviving swig of brandy from his bottle. Twice the play had to be stopped, and the leading actor stepped forward and begged for a little less competition from the audience. More applause and huzzahs all round.

The players won full attention in the graveyard scene, however. The audience watched intently, if for a brief while, and then they started calling out again, suggesting adjustments to the actor’s shovelling technique, and asking if he had bottomed out yet or how deep had he gone, and whether he had found any gold, and so on and on, to wonderful comic effect. If the intention of the management was to provide entertainment for the audience, then the evening was a triumph; but the cast could have taken very little credit for that. The diggers had entertained themselves, and the rest of us too.

In fact, Ballaarat does quite well for entertainments. As with all the goldfields, there has been from the first a racing track cleared on a convenient flat, and regular races are held in all sorts of weather. There are jumping competitions, and quoits and bowling alleys and skittle lanes. Other agreeable and convivial occasions are organised too, more enthusiastic than elegant. Victoria has yet to discover elegance. Subscription balls are held in the appropriate season—or inappropriate, as it turns out in this climate. In the old country, from time immemorial, winter is the preferred time for concerts and dances and the like, the social season; and as it is there, so shall it be here. These are noisy and jolly events, and vigorous, starting with energetic stamping to clear the mud off your shoes. Some of the gentlemen may have unearthed a pair of dancing pumps, others regrettably are still wearing their boots, to the imminent danger of their fair partners. Some unself-consciously continue to wear well-travelled top hats. The ladies of course are all in their best bonnets.

And pointedly, the price of admission for a lady and a gentleman is the price of the monthly licence. Each. That tends to keep the numbers of diggers at bay; they don’t like the reminder. Instead, those present are for the most part the storekeepers and the doctors and other professional types, with a sprinkling of those who have struck it lucky. The hall in which the dance is held is decorated with loyal flags (another discouragement to the diggers) and banners, the wooden floor fresh scrubbed though before long it shows that not everyone was meticulous about removing what they have walked through on their way to the ball. Couples push and shove for enough room to show their steps; the orchestra sits up in a balcony along one side of the hall, and the chandelier throws its charming glow over the entire proceedings.

But alas, the waiters have been circulating too well among those onlookers sitting on the benches—chairs are in rare supply—and the merriment increases to occasional evidence of tipsiness. Throughout the evening the well-meaning public generously keeps the orchestra in mind, and at frequent intervals sends up a bottle or two with compliments, and so the music becomes a little more ragged and discordant as the hour passes, but nobody notices because that is entirely in keeping with the rising voices and shifting attention of the patrons. Acquaintances are calling out across the room to each other, husbands are trying to catch the attention of a waiter, plump wives are kicking up their heels, the violinist has left his companions … everyone is having a very good time indeed. So why regret elegance?

In contrast, but not such a contrast really, are the evening concerts you come across in the more ambitious hotels. The main bar is sure to be well patronised in any event, but sometimes the publican arranges for an entertainer, a singer perhaps, with a repertoire of old favourites and a few amusing patter songs. The accompanist has his work cut out—he sits on an upturned keg for lack of a stool, and the piano lid might be held open by a miner’s pick. He is on a small raised stage, which he shares with several of the drinkers. Most of the men stay close to the bar, some grouping around the stove that warms the premises, and of course near to the girl who stokes it with billets of wood from time to time, though the quantities of rum consumed should soon make those contributions superfluous.

The singer holds the floor, just under the chandelier, this time a makeshift chandelier, a pair of boards at right angles hanging from the ceiling, and with candles at the four ends. He tries to avoid catching the eye of any of his audience, for they are all too ready with a clever sally, and their game is to break his concentration. Yet among the men are those touched by old memories that his songs awaken; others are too far into their own drinking to notice he is there. A cat under the piano is frozen—it dare not take its eye off a miner’s dog, which in turn is poised to leap if the cat so much as moves a whisker.

And on the wall, immediately above the piano, that universal and curiously apt reminder, almost a motto for the times: No Trust.

Sometimes the entertainers become quite well known. One young man, Charles Thatcher, has made quite a hit, not for his rendering of old favourites but for his witty ballads about topical matters. The diggers roar with approval at every arch reference to the Governor and the commissioners. In this respect he reminds me a little of Billy Barlow, though his is a much lighter voice. Pleasant, but not strong and ringing, such as might be advantageous in these premises. That comes as a surprise, for he is a big man, with a huge barrel chest and a drooping moustache, like a strongman at the circus.

So many of the memorable people I have encountered have been tall. More precisely, I notice that the people who get noticed are, as often as not, tall. It is much the same as being a Nob, really—an unearned benefit from the lottery of birth. Good luck to them. There is no point in resenting their advantage; they did not ask for it. My complaint is with the way of the world, over-impressed as it is by the incidental. For myself, I both do and do not want notice; a few extra inches would not necessarily resolve my quirkiness, but they would have been welcome.

Thatcher is admired for his pointed thrusts and ready rhymes, not for his commanding presence. He is witty where Billy is droll. Thatcher performs as the height of elegance, and it charms the rumbustious diggers that even so he is joining forces with them. Barlow parades low life in front of his audience, he is one of them, if satirically so; he is careful to keep a sufficient distance from gentility and elegance, and so does not embarrass them with imitations of themselves.

What passes for entertainment comes down a notch on other evenings, when the piano makes way for a boxing ring for example. Once again, there are as many men leaning at the bar as sitting on the benches, watching the adversaries taking wild swipes at each other, rather less elegant than Thatcher’s effortless hits. As is my wont, I like to sit to one side and watch the faces of the spectators as much as the bout. The patrons are keenly absorbed in the spectacle, swaying about and shuffling their feet as though they are in the ring too, clenching their fists or biting on the stems of their pipes. It is left to the non-smokers to lead the applause—or rather, because everyone smokes a pipe at the diggings, it is left to those not actually smoking at the time.

The boxers give of their best, but they are rarely skilful. They are novices more often than not, learning the manly art. Their feet are liable to slip from under them, for they wear their boots; the hobnails make a clunking sound on the boards. This is another occasion when it proves advisable to have scraped the mud off your boots. As the combatants wear big padded gloves, they are unlikely to do each other a mischief. They lead with their fists up, and lean back from their opponent to give themselves extra time and distance to see an oncoming punch, but that in turn means that when they want to swing one of their own they have to perform a little hop and a skip, which of course their adversary can see and so takes evasive action of his own. Which does not make for much of a spectacle, and is why the crowd tenders encouragement to get into ’im, whack ’im young-un, and the like. On the odd occasion you might see an ambitious smooth-cheeked young fellow taking on an old grizzled bullock driver, but you would have to be quick, for that would be no contest and all over far too quickly for the young cub to remember much about it.

These fights are comfortable exhibitions mainly, under the soft candlelight of the wooden chandelier, with the spectators sitting around and growing more and more mellow as the evening wears on. Much more furious are the fights that take place outside, usually in the vicinity of a contested claim, or when one digger has challenged his mate for not being meticulous in sharing out the gold that has been found deep down in the shaft or in the sluicing tub. Then matters get serious, and it is bare knuckles fighting, and no referee.

Whatever is at issue gets resolved when one of the two is unable to continue; but that does not necessarily mean the matter is settled, for bad feeling follows bad blood, and it is not unknown for supplementary fights to break out among the spectators, and in no time at all there can be a wild free-for-all. If there are Irish about it might turn into a donnybrook, with sticks and axe handles and anything else ready to hand being swung around with more vigour than finesse. It does not pay to get mixed up in those encounters. And it has to be confessed that the interest in fair play is not entirely honourable. The onlookers bet nuggets of gold against each other on the outcome, and have their own best interest at heart. Not possessing a pouch of such nuggets, I am constrained to more modest wagers, in coin of the realm.

I noticed that as the constables became increasingly officious, and obnoxious too, so the diggers were beginning to take out some of their anger on each other. Some as I have said started massing together to rant and rave, and there were troublemakers as well as men of strong convictions all shaking their fists at what they felt to be oppression. Once the new governor, Governor Hotham, insisted on strict application of the law, and appointed more constables to ensure it, the men reacted as might be expected. There was a strong atmosphere of general unpleasantness abroad. The diggers especially disliked the martinet, the man who applied the regulations and paid no attention to individual circumstance. That was the Governor, and his minions followed his lead. He couldn’t have made himself more unpopular if he had tried.

By the year’s end, everything had come to an appalling head-on confrontation, at a particular field at Ballaarat called Eureka. As I heard the story, a publican had scuffled with a pair of late-night drinkers and kicked one of them to death. He was not well liked in any case, and was widely suspected of underhand arrangements with the police. An inquiry exonerated the publican, and the diggers, enraged and deeply suspicious of complicity, took matters into their own hands. The hotel was burned to the ground. The Governor would not tolerate such unlawful riotous behaviour, announced further measures to be undertaken and arrested the ringleaders.

And so it went on, back and forth, with more public meetings and mass demonstrations, and a mass burning of the repugnant licences, the diggers exciting themselves and declaring for a republic, the Governor bent upon establishing law and order; and all ended almost as quickly as it had begun, with a band of diggers behind a rough and ready stockade and with the Governor uncertain just how many of those rifles that could be heard most evenings all over the goldfields were now in the hands of the would-be revolutionaries.

He reckoned to take no chances, and ordered up a military detachment which, as one might expect, made short work of its ill-assorted opponents. It was something like one of those unequal boxing matches, where the defeat was too quick and too decisive to find anything but the tatters of glory in it.

It was nothing like those boxing matches. Men were killed. By the preservers of the peace.

I went up to Ballaarat to see for myself, and it seemed to me very curious that whereas the hotel in question had been burned to its stumps, neither the bowling salon on the one side of it, nor the premises on the other side, had been even scorched by what must have been a fierce conflagration. Which made me think the fire had been well tended, and that would have required more than just two or three ne’er-do-wells. Those charred timbers spoke most eloquently of what the diggers would not tolerate. So did the unharmed boards of the neighbouring buildings. They would take care of their own, and in quite another sense take care of those who connived with the law; and by extension, they would take the law into their own hands if and when the law failed them. No wonder the Governor recognised the danger in that threat. On the whole the diggers are, for all their occasional unruliness, a reasonable set of men. Live and let live is their motto, and if there is occasion to settle a difference then it is carried out man to man, with bare fists. And with enough of a ring of spectators to act as both witness and jury.

The other hotels all survived intact. Not that fires are unknown, for they rely on insecure stoves for heating in the chill evenings. They are the common meeting place for the diggers after their long day down a muddy hole, or standing in a flowing creek sluicing the tailings, concentrated and isolating work. The hotel is where you would meet chance acquaintances, that is, where old friends would most likely encounter each other again. As happened to me.

I was seated at a table to one side of a saloon, with my glass and bottle at my elbow and my sketch pad in front of me as was my custom, when a big heavy hand clapped me on the shoulder, and a great voice boomed out.

Corky me old mate, hor hor hor. Well I’ll be blowed, old Corky.

That started quizzical glances, as it was not a name I ever went by. This here’s Corky, Trumble announced to the world at large, him and me was shipmates. He drores pictures, does Corky, used ter drore pictures of us down below, hor hor hor, in the fo’c’sle. All hands below decks, hey Corky? Hor hor hor.

Vile insinuation! But that was always Trumble’s way, to nudge and wink to the world. This does not sound well, I thought to myself. I should have stayed the course at John Aloo’s. Trumble, more grizzled than before with ten or more years of sailing since I last saw him, still has a carrying voice, designed for announcing imminent disasters in the teeth of the howling gale; and his laugh is unpleasantly suggestive.

Yairs, says Trumble, drew pictures of each one of us, hor hor hor.

Hints of the questionable Paris-trained Englishman began to stir in the minds of the drinkers present. I could sense it. Oh and oh and oh again. I was fortunate that Trumble had a swag of associates he was drinking with, and it was not too difficult to extricate myself with much handshaking and promises of catching up very soon, and me promising myself not to frequent that particular hotel in the near future. That was not a connection I wished to renew.

And the reason for that was that I have been hoping to impress a certain young lady I had met recently, and who has become the real reason for my continuing visits to Ballaarat.

The way this came about was exactly one of those chance encounters I have just alluded to. At a rather more superior establishment, a young woman was playing sentimental numbers on a piano, in a small withdrawing room off the main bar. I was observing the busy throng as I do, out of the way and nursing my nobbler, altogether forgetful of myself and watching individual characters and the unfolding of little incidents. Tableaux you might call them; or given the loud hum of many conversations, dumb shows. I had also noticed the piano player of course, and as she was absorbed at her instrument I sketched her in profile too, and from time to time looked back to see if she had changed her pose. Her dark hair was bundled back on to her head, her chin held high and a velvet ribbon around her throat, her eyelids lowered I imagine to avoid impertinent glances. I did not think mine were impertinent.

As I was laying in the shadows, and putting in the stronger touches—the fine arch of her eyebrows, the line of her chin—I was startled by a voice close to my ear.

And what do you see, she was asking.

No, it wasn’t a question, it was a challenge.

You’re Ethan Dibble, aren’t you, the artist.

Another challenge.

This was possibly very promising. But you can see why I would not want to revert to the character of Trumble’s Corky. She took up my sketch and looked at it critically, at arm’s length—a very shapely arm too, and long hands and fingers. And after what seemed a long interval, she nodded, not at the image of herself, but in recognition of my skill in capturing it. In full face she was as attractive as her profile promised. She has a fair complexion, wide-set eyes, and a broad smooth forehead and a small determined mouth; her natural look is serene, more than thoughtful. Certainly not demure. An unusual young woman for these parts.

We began to talk of my art, and of my disappointment in not having made a success of portrait painting, for it turned out she knew of my pictures of the goldfields from those that had appeared in the papers. I suppose it was a change for her that I did not talk of claim jumpers and shicers and whatever else passed for interesting conversation with the diggers. Once started, it was easy to keep on with an exchange of pleasantries; and I was further heartened that, when she returned to the piano to resume her duties, she made a point of sending me a smile from time to time. One thing leading on to another, we bettered our acquaintance over the weeks, and indeed she it was who had accompanied me to the riotous performance of Hamlet, which had amused her heartily.

Over this time, she encouraged me to take up again my ambition to paint portraits, and once I had shown her some sketches of her that I had worked up in my studio, she agreed to sit for me. That was a challenge; for I am very rusty. I have done few serious portraits since my first arrival in Adelaide. It posed a problem too, so to speak, for it would have been improper for her to sit unattended—different of course when you hire a model. But that was not the arrangement here. In Portsmouth we had always arranged for a female shop attendant or a maid to hover discreetly in the background, to safeguard the proprieties.

I suggested that perhaps her landlady could attend the sittings, and she thanked me for being considerate of her reputation; and so we proceeded, and by the end of the year, that is to say at approximately the same time that all Ballaarat was at sixes and sevens after the Eureka Stockade affair, I was able to present the young lady with her portrait, her name—Elizabeth—neatly worked on to a folder of music she is holding. It was clear to me that she was very pleased with my gift to her, for such it was. And she could see that I had studied her face as carefully as she had herself, though I do not pretend to have read its secrets.

But dearest Ethan, says she, you haven’t signed it.

That was readily set to rights.