Sketch 11

In which I am out on the town

NOW I HAD a new resolve. I arranged a meeting with my publishers, we agreed to terms, and they announced not only that I am their acknowledged lithographic artist, but that another set of my topical sketches of the diggings was shortly to be published. As it turned out, most of these were of Ballaarat. I had my own reasons for visiting there, of course, but that field also happened to be what the public was most interested in, so that the selection worked out very well in all respects. I had achieved a more or less regular income, if modest; and the benefit of sales of the originals of my published sketches, as well as the albums.

I had the publishers’ studio to work in, with good light and a bright mirror by which to reverse the image when I drew it on to the stone, for the lithographs; and space to work up those sketches for which I had only the barest outlines in my notebooks. I could safely leave all this for a brief sketching tour, not only to the diggings but to the farming country further to the west of the colony, and the little coastal ports, and wherever else took my fancy. I could afford to travel at my own pace and in my own way, on a horse and camping out as I wished; or, if the weather were adverse, I could travel by coach, as I sometimes did.

I am more comfortably off than I have been, and no longer feel quite so keenly the humiliation of having had to leave Adelaide a bankrupt. I am once more respectable. I was invited by an acquaintance to join the newly formed Garrick Club, and I was honoured to allow my name to be put forward. With its premises also in Collins Street, I am making this my end of the town. I fancy I shall be expected to sing for my supper, so to speak, and to help design if not prepare the stage scenery for some of their intended productions. Imagine me, a member of a club. I have no doubt that far exceeds any expectations my father would have had of me. Though possibly it would have confirmed his disapproval. He remained trade—he spent his last years working as an agent for a tea importer. I heard from relatives that he had passed away. We had not maintained contact with each other after his second marriage.

My father’s last flurry, canvassing orders for tea, is an oddity. That happened to be the case with Coppin too, his father giving up the stage as mine the pulpit, both abandoning the platform you might say, and looking to find their fortune in tea leaves. Coppin is back in town. Coppin is amazing the town. He had been in England for a year, and returned with a tin theatre all in pieces, which had to be puzzled together at a convenient site. It is called the Olympic Theatre, though it is more commonly known as the Iron Pot. Intolerable in the summer heat, and impossible whenever there is rain, yet given the crowds who attend it is undoubtedly meeting his expectations. He has the happy knack of hitting payable dirt in everything but the diggings; he invariably strikes it lucky.

The question for me is how he affords this kind of investment in the first place. He too left Adelaide in financial difficulties, but apparently he returned to pay all his debts in full (and, let it be said cautiously, encouraged reports of that settlement to be widely circulated). Honourable indeed; but how on earth was it managed so quickly?

Coppin of course is a clubbable man, a would-be Panjandrum like Dr Johnson. He would not miss out on the connections to be made through the Garrick Club. He has likewise carried over to Melbourne his old connections with the Freemasons. And he is much in evidence at the expensive end of all the best bars. A Snob in the making, laying out his credentials. He has hailed me out loud and shaken my hand—Ethan, dear boy—and then turned back to his new acquaintances, for he has larger fish to fry than me, a mere tiddler. The old benefit is still there however. He knows all the latest gossip and relays it in the drollest way; and in turn, other interesting snippets are fed back to him, and to anyone else near enough to hear what is hardly kept subdued. Indeed, the tight circle around Coppin is constantly in an uproar of laughter.

He it was who first advised us of the imminent arrival of the scandalous Lola Montez, and her troupe. I wonder whether he thinks he might have promoted her visit himself, though probably he would be too anxious about any connection with a woman of her notoriety. There can be no doubt that she would have earned him a fortune. Another fortune. As it is, she intends to keep that fortune herself. She has her own manager to make all the arrangements about theatres and accommodation and travel. There appears to be no need to place advertisements, as the whole of Melbourne knows of her presence in their midst, and so do the diggers, who are insisting that her tour should include the goldfields.

Madame Montez began her season at the Theatre Royal, with the standard fare of comedies and vaguely operatic plays, in which she both sings and performs, though it is not for her voice that the crowds flock to her performances. She was so daring as to perform her much-famed Spider Dance, or a version of it, about a week after opening. The first reviews were predictably outraged, but then a man called Horne set about trying to change that slant. After one performance, what the press called a frightful-looking old man jumped up on to the stage, brandishing a pistol—he intended to use that to persuade her to love him. The old spindle shanks was fortunate she did not attack him with a whip, as is reported to be her wont. I imagine she would have done so had one been to hand.

Who can say whether he was not hired to create a stir? The audience was quite excited by his ardent interruption, and of course attendances went up after that—as if it would be permitted to happen again! There were predictably stern letters to the various editors, to the effect that with such indelicate dancing it could only be expected that lewd members of the audience—and unhappily there were only too many of these—would lose control of themselves. A reverend gentleman threatened a law suit, though he could not allow himself to attend any of her performances.

Coppin found the controversy irresistible, and Billy Barlow performed his own version of the dance on the stage of the Iron Pot. With his great big belly and a garland of flowers on his head, he clumped about and spun around in a taffeta skirt, and turned ridiculous somersaults; and after many comic antics he dashed out a huge stuffed tarantula from his petticoats and kicked it all about.

When famed Lola Montez for spiders did look

I took a leaf out of her very own book,

The first night she danced she something did show

Not at all like the spider of Billy Barlow.

Oho did she so, ho raggedy oh!

Not at all like the spider of Billy Barlow.

And to complete his teasing burlesque, he feigned exhaustion, and doubted whether he would be able to complete his engagement for that evening, just as, by the reports that have preceded her, Madam Montez was wont to do; for it seems she is regularly either very fatigued, or unsteady because of the surfeit of champagne with which she prepares herself.

Coppin is vastly popular with people who like to laugh at others. Parody is his forte. I have to admit to sharing something like the same sentiment when I think of the Nobs and Snobs and the bungling governors. But I do not mock the people I sketch. I do not choose characters who are unfortunate in their appearance. I once saw a man on the diggings who looked as though his ears were upside down—they had no lobes, and too much flesh at the top. I do not draw cartoons. Imagine what one could do with Coppin! Imagine what Rowlandson would have made of him, or Cruikshank.

Our own Governor has not enjoyed the season in anything of a like manner. Indeed, matters have gone from bad to worse for him ever since the Ballaarat uprising. To make some kind of amends I suppose, at least among the Melbourne folk, he decided to give a ball—over seven hundred invitations were issued. Who can say what he was thinking of? Perhaps he hoped for widespread disaffection, but the wives of the colony were not about to miss such an opportunity. Everybody turned up, and in carriages necessarily because he lives just out of Melbourne, at a village called Toorak.

Such was the demand for cabs and coaches and carriages that even miners’ carts were pressed into service, all converging on the Governor’s residence at the same time. You can imagine it. Like ants to a discarded chop. And all the ladies in their newest dresses and fanciest bonnets, crushing to get into a residence far too small for such numbers. Many were forced to wait outside at the entrance, others waited in their carriages, and the rain poured down and quite spoiled their feathers. Stoicism was in short supply.

The men were at least resolved to enjoy the supper, but at the appointed hour, when they surged in to the tables, they were astounded to find nothing better than plates of cold meats and ham set out on the sideboard, and a barrel of beer. One hopes the Governor had been mischievously ill advised, but whether or no he shows little awareness of the people here. That bill of fare smacked of contempt. The papers of course were delighted with the story of the ‘beer ball’, and have kept at it for months.

It was no great surprise to hear at both the Criterion Hotel and then the club, that the Governor had resigned—there’s another one gone, thinks I. A truer reflection than I knew. Unhappily, he did not get to leave his office. He took a chill at the official opening of a gasworks, too much wet cement about the foundation stone perhaps; and within just a matter of days he died, on the very last day of the year, meticulous and tidy to the last. I should not be so facetious, I know.

Who could not be flippant though at the accompanying news, that Captain Strutt immediately offered his services once more, as the replacement governor. The very man for a gasworks.

Another juicy morsel I picked up, from the same sources, is that Madame Montez, who had gone back up to Sydney for a month, returned from her performances there aboard the same steamer as the Reverend John Dunmore Lang and Dr Geoghegan, the Roman Catholic Vicar-General. What would one have given to witness that passage! The fiery Scot must have been almost apoplectic—he would not have been able to determine which of the two was the more pernicious. Just the sort of thing for the newly published Melbourne Punch to chortle about.

Not just Punch but all the papers delighted in Madame Montez’s next scandal. She had moved on to Ballaarat, to a large new theatre built right next to the hotel, with a capacity of two thousand, and where she would give the opening performance. The crowds turned up. There was standing room only, and she received a gratifying applause. A day or two later, though, there was an altercation in the saloon of the hotel. The editor of a local newspaper had attacked her for the immorality and unhealthiness of her kind of entertainment, and reflected on her notoriety.

That was just the sort of provocation to excite Madame Lola, as reports of her conduct in the past have shown. She spoke of horsewhipping him, but he took up a heavy whip of his own and stormed down the road to the hotel, and a famous ruckus started, each flailing and cutting away at the other, and at closer quarters pulling hair and shouting and screaming. Or bellowing, as appropriate. This piece of theatre was widely reported too, though the Melbourne Punch saw off all competitors with a whole page given over to a mock epic in quatrains.

The fracas and the scandal appear to have done little harm to the dancer’s popularity; she has lived up to the fiery component of her reputation. The editor, who had been one of the heroes of the Ballaarat uprising and had spent three months in prison (another of that governor’s political mistakes), came off distinctly the worse, with the crowd jeering him and pelting him with fruit and whatever else was at hand. And of course it gave her a brave opportunity when she next danced to shake her whip and decry such unmanly attacks on a defenceless woman. She did not appear to notice the contradiction there. Loud cheers.

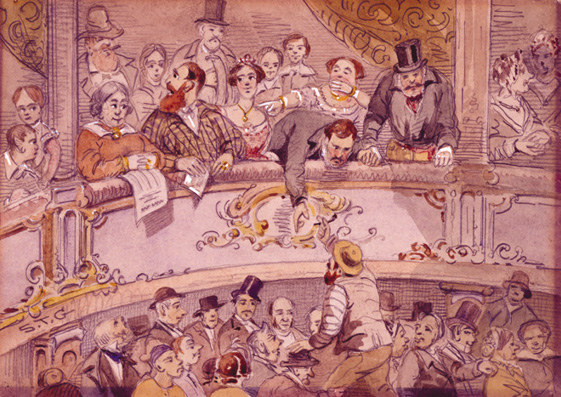

I witnessed the celebrated Spider Dance not in Melbourne but in Ballaarat. Given the likelihood of a disorderly house, I went unaccompanied, and it is well that I did. Long before the man in the green coat and white gloves had stepped on to the stage in front of the curtain to announce her act, the audience, mainly diggers, and not by the look of them of genteel background, were beginning to excite themselves, growing restless, whistling and calling out. Spider! Spider! they were chanting, and beating out a rhythm with their clapping, and calling out again, and whistling some more.

When the flunkey made his appearance, what a roar! It quite drowned him out. They didn’t need to hear what he was telling them, even though that was just what they wanted to hear. What a cheer! And when at long last the curtains opened, the roar turned into uproar. Cheer upon cheer, more whistles and more applause. Though all Madame Montez had done was pause at the back of the stage, not much more than a silhouette in the half light there. A profile. Yet that was already daring, and enticing, for her flimsy gauze skirt was short enough to show a pair of very neat legs, and nipped tightly in at the waist, and her sleeves and bodice were cut short too. While you might have been encouraged to think of Spain you were very aware of the woman.

She is, without doubt, a great beauty. She has a face made for the stage, the shapes and lines all just that bit stronger than usual, so that she looks very striking, especially with the emphasis thrown up by the footlights. She has great swathes of thick black hair, and the most extraordinary dark blue eyes. Oh, but when she came forward and began her slow dance, and then faster and faster, there was a rapt and intense silence, and then something like a deep, yearning, brutal growl, and the cries and groans came thick and fast from all parts of the theatre. For the rumour is that in America Lola Montez had not always worn stockings under her skirts, nor much else either, and so there had been ferocious jostling to take up positions close to the stage.

Wags will always have their say, to raise laughter, a kind of jeering. After him, they would say. Oooh Lola, ooh la la. Louts encouraged each other by such catcalls. There he goes, higher up, higher up, the front rows called out encouragingly. Spider, spider.

And carrying right across all the ribaldry, a voice I recognised again, only too well. Hey Miss Muffett, where’s yer tuffet, hor hor hor. Uproar again, with stamping and clapping and whistling. I cringed, not daring to let myself see him. Trumble. If it wasn’t Trumble, then an identical vulgarian.

Of course there was the usual tumult in the audience. One digger grabbed the collar of someone who had started to hiss the dancer, and knocking off his hat, poured brandy over the offender’s head. Raucous cheers from those close at hand; and he waved his bottle to all and sundry to show that there was more of that medicine should there be any repeat of the offence.

At the end of the performance, after the spider had been shaken out and immoderately trampled to death, a shower of nuggets was thrown on to the stage. Some landed in among the little orchestra. The diggers were more than ready to pay good money to see a famously immoral woman, and to throw more again at her in their enthusiasm. Just to see her at a distance was excitement enough. They could of course see other immoral women on the goldfields, in the camps, or at the back of hotels and grog shops, and did so. There would be tell-tale queues outside some of the establishments, such as the Irish Trumpet, where Doll Puckett ruled the roost. Officially her house was known as the Golden Horn. Many a husband, and not necessarily her own, had she pinioned in her massive forearms. My girls aren’t here for choir practice, dearie, she used to cackle.

No doubt there was an after-theatre party at the hotel. Madam Montez is famous for these, though only select persons manage to be invited. More champagne, and smoking—she insists that the English do not know how to smoke properly, and gives demonstrations in how to fully inhale the smoke, and blow it out again after some minutes. Some say she also holds séances and sessions of table-rapping and contacting the spirit world. And enjoys opium. And that she delights in wearing male attire. I heard of this from Elizabeth, who was employed at the hotel where the actress resided.

In Bendigo, she was at the centre of an even more dramatic spectacle than usual. In the midst of her performance in a play, in the midst of the vile weather I well remember from that part of the colony, the local newspaper reported that with an enormous clap of thunder and a blazing flash, a ball of lightning smashed through the tin roof and on to the stage itself, passing close by the performers, setting light to the scenery and blasting a great hole through the timbers of the wall.

Sensation! Screams and cries from the ladies in the audience, and the actors, and the scene shifters, and a smell as of exploded gunpowder, and all was confusion. I imagine Madame Montez’s lanky young gentleman, a second-rate performer with legs like Sam Slick’s, acted the part of a croquet hoop while the lightning ball trundled through. From what I gather, he was not good for much else; though he had drawn his pistol when the Ballaarat editor pulled out a cosh towards the end of that famous contretemps with the whip-wielding harridan.

From there, she agreed to perform for several nights in Castlemaine, in the local hall there. Castlemaine, for all that it has a new name, has far to go. Trees and stumps remain impediments in the main road. Some of the new buildings look very well, and are solid structures, but the hall is less than splendid. It has, or had, only a dirt floor. So planks were laid down for this occasion, and as it held only four hundred—far fewer than the Governor had invited to his residence at the beer ball—very little space was left when the curtains parted.

There was not enough space for the usual orchestra either, and in their place my Elizabeth supplied the music on a piano! She had been heard playing in Ballaarat, and had caught Madam Montez’s attention. I was uneasy at that, at the invitation I mean, though the other did not sit altogether comfortably either. I knew what kinds of things were likely to be shouted out if the Spider Dance were performed, as undoubtedly it would on at least one of the nights. Elizabeth shrugged at my anxiety, said she was unlikely to hear anything she had not heard in the hotel, and that she would be well cared for by the rest of the company. I was not sure which grieved me the more—her exposure to such coarseness, or her casual dismissal of it.

Of course I tried to gain entrance on the first night, but was elbowed out of the way by the press of great hairy-wristed fellows—for they wear the sleeves of their jumpers pushed up—all intent on a grand time. I don’t like pushiness; I find such behaviour distasteful. When I spoke to Elizabeth the next day she insisted there had been nothing to worry about. She had enjoyed the change from her usual duties. She seemed more at ease with this troupe of theatre people than I had expected.

It was only a brief contract. Lola Montez returned to Bendigo, Elizabeth to Ballaarat, and I with her. And we talked very seriously because we had now come to an understanding with each other. This was when I was startled to learn that Elizabeth was in fact already married, or had been. Her husband had left almost immediately afterwards for the diggings in the distant rugged mountains, to revive his fortune. She had not heard from him at any time since. She was not at all like those girls who agree to be married for a week or so to a digger come to town, but who knows what her brief husband was? She had no expectation that she would ever hear of him again, and in fact would now prefer not to. She considered herself well rid of him. A widow in her wish. Nevertheless, it meant we could not ourselves marry, as I wished. What could we do? It was above all else important to preserve her reputation.

The landlady, a Scotswoman, keenly interested in our attachment, indeed keenly interested in anyone’s private life, gave us our answer. She knew Elizabeth’s story, or as much of it as she had been allowed to know, and shared her lodger’s scruples. Or so I prefer to believe. There was an old Scottish custom, she told us, handfasting. As respectable as a marriage, and just as binding. And she would show us how. And so, with her nodding and blessing, in a very short while after, we tied our hands together with a ribbon, made our vow to each other and stepped over the broom, shared a glass of sherry with the good woman, and so we went to bed. To her delight as well as our own.

But because we were not sure that everyone else understood the true binding nature of handfasting, we thought that it might do well to leave Melbourne behind, and go to Sydney, where I was sure I could establish myself anew as an artist, and where there were other goldfields for me to sketch. We too could make a new start; as seems to be the way of things in the antipodes. Which is to say, nothing much seems to last for long.

And so it is that at Williamstown we have boarded a steamer for Sydney, though in just the sort of atrocious weather you might expect in May, driving past the great dead weight of the prison hulks groaning on their anchor chains, the doleful bell clanging—shades of Portsmouth! And into squalls of rain and a severe heaving sea. The soot and smuts blow ahead of us; we are chasing our smoke to New South Wales.