Sketch 15

In which I revise my views

WILLIAMSTOWN AGAIN. I suppose by its name Williamstown was intended as somehow Adelaide’s equal, as though they were intended as consorts. One difference is that prison gangs have cut and scraped and made roads. The public houses have already acquired the look of places best avoided—not so very different from the Rocks. Or as I seem to remember, Portsmouth. This is a dockyard, and the taverns that serve them are much the same everywhere, Port Misery aside. But then, it is hardly a dockyard, or not as I recollect. A port of call, and little else.

Dockyards and harbour fronts conceal, they keep an impassive and slightly belligerent face, they tell very little of what lies behind. You have no business here, they say to strangers. Move along. Which was an unnecessary admonition in the heyday of the gold rushes, as I recall from eight years ago. There is still a jostle of shipping, but no longer as extraordinary as back then.

You do not have far to walk to see a workman with his pipe in his mouth and long-handled shovel under his arm, and a pig on the end of a rope, waiting for the ferry. Move along indeed.

But Melbourne! Melbourne is now visibly wealthy. Pandemonium no longer rules here, it has consolidated. Melbourne I mean. The wide streets are lined with substantial shops and buildings; trapstone gutters and stone kerbs carry off much of the slosh that I remember, downhill to the river and so out into what sailors facetiously call the big puddle. The footpaths are raised, and paved in the better streets, and the roads are well-maintained macadam. These are much more crowded than they used to be, with gigs and cabs and carriages, and dashing coaches hurtling pell-mell through the throng, and mothers and nannies snatching their children out of the way. Consolidated pandemonium after all.

Bare-footed boys dart everywhere with a bundle of newspapers under their arm, in and out among the traffic, in and out of the saloon bars. The better streets are lined with gas lamps, a mute memorial to the unfortunate Governor Hotham. Black coats and white collars and tall hats predominate, the colourful exuberance of the diggers is much less in evidence. Wherever crowds of gentlemen assemble, at stock exchanges and banks and railway stations, the scene looks like a set of silhouettes. The people have flattened out, and it seems to me they are all coming to look like each other.

The city—for such indeed it is, now—astounds. Everywhere is built upon, and built up. Stone upon stone, shapely piles as the poets say. Everything is so very square, uniform, as if to deny that the wealth here has been a matter of random luck, a lottery. Though you still see nuggets and gold dust displayed in the banks and in gold-buyers’ windows, to excite the newest arrivals and the speculators.

Gold has made Melbourne. It has also given it heartache, for as in Sydney so here is widespread anxiety that the great Russian Czar has designs on this available wealth. Rumours abound that he wishes to make himself master of the Pacific, and will attack Britain’s dominions. The loudest rattling of sabres is of course our own; nervously.

Which agitation found a timely outlet when, utterly surprising, an American sailing ship, the Shenandoah, needing repairs, came into the bay and tied up at Williamstown. I say American, but given the current ebb and flow of their Civil War, I should be more precise. It was a warship from the Confederate side of that unending discord. The newspapers, fanning the flames as ever, note that the Russians recently anchored a part of their fleet in San Francisco, and support the Unionists against the Southerners, to whom Britain has apparently been favourably disposed. Might this not provide a pretext for sailing into our waters in large mass?

Yet even while the presence of the Shenandoah introduced much nervousness, it likewise provided a flutter of excitement. There were all those sailors and officers to entertain, balls to hold, receptions to be offered. Craig’s Hotel at Ballaarat made its ballroom available for a gala event, the Melbourne Club opened its doors to the senior officers, and the Williamstown hotels opened their arms to the crew. The visit was all too brief, alas, or so thought the young misses of the town. And likewise a party of enthusiastic young men, some forty or more, who were so taken with the engaging company of the Americans that they neglected to leave the ship when it sailed. We heard later that the captain apparently could not find a single one of them until it had reached international waters.

That is the disadvantageous side to Melbourne’s stunning wealth. If it becomes of interest to the Russians, then that will mean dealing with just a bigger sort of bushranger when the gold is shipped off overseas; it will be another unhappy proof that might is right. But much of the wealth stays here too, and with it Melbourne is even amazing itself with the rapid transformation it is presiding over. Not only are the streets now well made, and the buildings properly aligned, there are bridges and railway lines and public buildings—no longer meaning public houses. Though of those, many are grand affairs, with dining rooms and extensive bars and billiard tables and bowling saloons. The better sort may have a bathhouse, maybe a hairdresser, and even a vaudeville theatre close by. These are in many ways as good as a gentleman’s club, without the exclusive membership.

The lesser hotels and other drinking establishments are not quite so salubrious. The bar attached to the Theatre Royal in Bourke Street, now owned by Coppin of course, is one place where patrons might expect to find an easy attachment for the evening. I remember that his theatre in Adelaide was near the naughty part of town, and Little Bourke Street is, notoriously, given over to the same sorts of nocturnal adventures. The vestibule at the Royal is sometimes spoken of, rather saucily, as a saddling paddock. Yet it is also one of the popular gathering places, convenient to all sorts of respectable business activity in the city.

I saw very little of the Americans or their ship, even though these were the talk of the town. I have been busy about my own business. I brought with me drafts of the sketches that Doyle had thought to purloin for himself; that is, my own originals, without his initials scrawled hither and thither all over them. My drawings had to be reworked for publication as coloured plates, and the sooner I could get those completed the sooner Melbourne would know that I was back in town.

Which was a proper plan of action, and had worked for me in the past; but as the reviews almost immediately pointed out to me, I had miscalculated—for even though they were published as Australian sketches, Melbourne is not so interested in scenes of Sydney and New South Wales. It won’t have helped that New South Wales won the last intercolonial cricket match, either. But at least I had been noticed.

You may be sure I did not repeat the mistake. When submissions for an Intercolonial Exhibition were called for, I worked away at a number of Melbourne scenes, as well as several of my old favourites from the gold-diggings days. Melbourne cannot get enough of Melbourne. Truth to tell, the great streets of Melbourne are now lined each side by an array of handsome and even sumptuous buildings, set out on a scale intended to impress. The people in the streets are somewhat overwhelmed by these, and in consequence the cut and quality of their coats and dresses tends to disappear as incidental detail. Really, I mean, not just in my drawings.

Not that I would dare breathe a word to that effect.

The best society converges along the middle section of Collins Street. Here towards the end of most afternoons you may see the most elegant equipage, the best-groomed horses, and the equally well-groomed ladies and gentlemen, all nodding at their acquaintances, or slighting those they did not wish to see. Fans and feathers, high collars and shiny hats, sparkling carriage and harness fittings, all are part of the passing parade. Along the footpaths a comparable measured promenade takes place, with much bowing and hat raising and swishing of skirts and flourishing of canes. And as the day wears on and night falls, the Nobs turn out in evening dress, the women in a froth of white. China white does not do it justice. Here the best people meet. This is fashion in full display, the height of colonial elegance. Or superficial detail.

One street away in either direction, or even at the far ends of Collins Street itself, alas, what a falling off is there! Mere merchandising.

This preening and posing and bustling is a long way from Sydney, where, I hear, Sir Frederick Pottinger has recently managed to shoot himself, getting into a carriage. He made a mess of that too, and lingered four or five days. Such clumsiness would not be tolerated along the Block. It occurs to me that his aim was no better than Goliath’s. Further afield, a vicious bushranger, Dan Morgan, has also been shot. There has been much less of that kind of activity, bushranging that is, but the shooting too, about the Victorian fields in recent times. The gangs seem to be more active across the border. Perhaps they felt more comfortable there while Sir Frederick was in the saddle. They will have to take fresh stock of their activities now. Perhaps they will think helpfully to forestall the Russians.

My own preferred terrain is in the adjacent streets and lanes of Melbourne. Bourke Street, where not ten years ago diggers used to try out half-wild horses just brought in from the bush, and showed their skills in sitting tight on the bucking steed of their fancy, Bourke Street is now busy with tearooms and tobacconists, and theatres with their bars and cafés. Where a man may be tumbled from an insubstantial chair with the same end result as from a scurfed saddle.

Right along the length of the street is one hotel after another, from the Imperial and the Orient at the top end of the hill, down to the Bull and Mouth somewhere about the centre, and so to the far end if you are still thirsty. They cater to a great motley trade. More to my taste are the taverns and pothouses in Little Bourke Street, and even the shanties in the lanes, though those can get somewhat out of hand later in the evenings. Larrikins hang about in the streets thereabouts, and are inclined to heckle and shove the passing custom, topers such as myself. The lanes are dark; there are no glowing gaslights such as those near the theatres, and the paving stones are uneven. Shadows shift about. You can easily stumble in the backstreets.

Here too is where the Chinese congregate, to play at fan tan and to gamble at cards. It is curious to me that while they are such inveterate gamblers, you do not see them at the races—even though vast sums of money are turned over at the new Melbourne Cup day, for example. The celestials have their own chophouses here too, with a row of cooked ducks hanging in the window opening, and opium dens in the remoter lanes. Such a curious mixture of smells here. The street girls escort you down these dark alleys to their rooms. This is the out-of-the-way Melbourne; more concealed than Sydney’s Rocks but otherwise much the same kind of neighbourhood. Lodgings are cheaper here than elsewhere in the city.

In fact that is a curious characteristic of Melbourne, that everywhere has its concealed after-part—as each of the main streets has a corresponding diminutive lane behind it. The Melbourne Club, for example, has at the back a place called the Crib, where the young bloods can kick up a ruckus, and from which they go on sorties into the rest of the town, to rattle door knockers or even to wrench them off, and to play whatever other tricks come to mind. The more sedate members stay installed in their comfortable seats in the front rooms, and read their papers, and drink their drinks, and plot their own advancement and the downfall of their business competitors. Or so I imagine, for I have never crossed that threshold and doubt I ever shall.

I have not renewed my acquaintance with the Garrick Club. A new club has just commenced, the Yorick Club, mainly for writers as I understand. A young fellow who writes amusing pieces for the Argus is the leading luminary, a Mr Clarke. They think of themselves as Bohemians. They organise suppers for themselves at a café, and smoking evenings, and goodness knows what else. From what I can make out it is not much different from the kind of entertainment I and my friends made for ourselves in old Portsmouth. We were Bohemians and did not know it; and I have had to come halfway round the world to find it out.

What with my scenes of Australian life, and my sketches in the Exhibition, and others printed in some of the newspapers, it was very pleasing to me to receive an invitation from the trustees of the Melbourne Library to compile a volume of thirty or forty sketches depicting activities on the Victorian goldfields a decade ago. They required new drawings, but of the past. What that meant was that I should look through my old notebooks and sketch pads; and review some of my earlier pictures to see how I might adapt them or build on the original drawings. It is a handsome commission, fifty pounds no less, and they arrange all the publication details. They will even sell copies of individual sketches from the Library.

Here, by the way, is another version of what I see in Melbourne, that the façade has a draggle tail. Maybe that is always the case, and Melbourne is no different from elsewhere. Or maybe Melbourne in particular is still trying to pick itself up out of the quagmire of its founding, just as Sydney pretends to have put its convict past behind it. The invitation has come from the chairman of the board of trustees, Sir Redmond Barry, a senior judge, recently knighted and full of public office. He has a lady friend installed in a cottage; sometimes they appear together at the theatre. I wonder if she plays the piano.

But that is nothing to me. I am pleased to have the commission, with the letter from his secretary. I don’t think judges write invitations. They write judgements.

It has been interesting for me to revisit my old sketches, as well as the goldfields themselves, briefly. I see now that I have changed my way of looking at this material, though I was not at first aware that such is the case. My new pictures show more light. The bush is not so closed up, the forests not so dark, the ranges not so louring. You can see further into the landscape than I had remembered. Even in the Black Forest itself, you would be able to see from some way off any skulking shifty fellows. The skies, as I have painted them, are not so pronounced; I notice that I have chosen again and again a soft grey or buff wash. The fields are less boggy, even though the weather is in fact just as changeable.

What my sketches show is that I am now more interested in the individual figures, the character they show—the figures are larger in the composition. I look at them as much as at what they are doing, to decipher, if I can, something about the people themselves. For example, you can see just by looking up and down the streets of Melbourne what it is they have achieved. Most of this town is no more than fifteen years old. Amazing. But what of the people themselves, what have they become? What is it in them that has led them to become whatever they have become? Is it possible to see who will succeed, and who will fail? Do the unfortunate ones carry the mark of Cain? If so, that is hardly to inspire hope.

And what of myself?

So many men and women have come to Melbourne, to Sydney, and yes to Adelaide though with somewhat different expectations, but all seeking to make their fortune. To find their fortune. To mend their fortune. How is it that some succeed, like the Baron of Beef, and not others? What is it that decides their lot? Is it all just the fall of the coin? I admit I am anxious about whether this set of my sketches will meet with favour.

The larger views do not offer the same opportunity to reflect on the people who have come here. It is curious how differently one thinks about them as individuals and as a group. For example, in my picture of the diggers lining up to buy their licences, the men are all inside a holding paddock opposite the commissioner’s tent. It shows how demeaning the process is, the men having to await the pleasure of the officers. Pairs of policemen here and there take up the foreground and middle ground, the diggers are kept further away. That is, a very distinct distance is maintained between the commissioner’s camp and the diggings, between the police and the men. The police are doing nothing, which I suppose is called being on duty; one, reading a newspaper while the pot bubbles away on a fire, has what may be the most consequential job of all. The gold is all safely out of sight. The others are all self-consciously displaying their uniforms; somewhat like Russian sailors.

In some general views of the diggings, I have designed for two or three particular details to stand out. The early onslaught gives way to a second phase, where instead of a valley pocked with holes, and the tops of ladders jutting above the ground, you notice many more windlasses, some well constructed, some dangerously flimsy, but all indicating deeper digging. The great mass of scavengers has moved on, looking for easy pickings; now the hard slog, as the men say, remains, and that means long sustained effort, and semi-permanent dwellings. So that another difference is in seeing cartloads of planks arriving on the fields, and becoming the cladding for huts. The old hands used to make do with slabs of bark, if they thought to put up anything more lasting than their tents. There is still a good plenty of those of course, almost marquees some of them, especially when they combine a business with living quarters, such as a store or a doctor’s surgery or the like. Boarding houses. You can spot those by the sheets of stringybark leaning against the side of the tent, each one a bed available for hire for the night. Bit by bit the chaos of the goldfields turns into the first makings of small villages.

Passable tracks now meander across these later diggings, with rough little bridges over some of the more awkward culverts, and those tracks become possible because a great number of the men working their claims has moved on. They have got out of the way, literally. The diggings are somehow more spacious. The bush all around has been thinned out, the valleys and gullies are open country now. Trampled and tossed about, but open, so that you can see how far and extensive the activity is, the numbers of people living and working in the locality. And with those huts you see more women and children, families, and with them perhaps a little plot of vegetables, and a chicken coop, and a cockatoo chained to a perch. The people have organised themselves. The authorities are an intrusion.

You see the unspoken antagonism whenever a policeman demands to inspect the diggers’ licences. The miner’s right. The digger has to come up out of his claim and produce the required document, and the policeman takes an inordinate length of time to study it. Possibly he is not very good at reading, or possibly he is making a point of being deliberate, for the effect on the digger is intimidating while he awaits the official nod. Waits so long that he has half finished his pipe before receiving back the all-important piece of paper.

There is a curious confrontation in this. The policeman wants an opportunity to find the digger in breach on some account or other, as his perquisite is one half of the fine. Yet if the digger has his bona fides the policeman is forgoing valuable time when he might catch out an unlicensed digger on the next claim. He should be getting a move on; the digger wants to get back to his work too. Time is precious. But a bird in the hand is as good as a whole flock in the bush, and if there is the slightest possibility of charging the digger, then that is what the officer will of course do.

It is no way to establish an amiable working relation. You might have thought the authorities would have learned something from Ballaarat, but no. The makings of a petty tyrant lurk in every officer’s breast.

I have arranged my album in an obvious pattern, the sequence of a digger’s experiences. So I begin with a couple of new chums, ordinary fellows, camped on the track to the goldfields, travelling light as I had done, and somewhat glum at what they have undertaken. They have lost their way. Their swags are still unrolled, the billy is on the smallest of fires, and their meal is a piece of damper on a tin plate. Their trousers and boots are still clean, their gold-washing pan is as shiny as it was when it left the store; so is their pannikin. They will need to make up a much bigger fire to fend off the chill of the coming evening.

They look quite disconsolate. Whereas the well-heeled newcomer looks less down in the dumps; but at a loss nevertheless, even though he has arrived. He is neatly dressed, in a good cut of coat and a hat that has yet to be rained on; and he does not know what to do now that he is at the diggings. He has found an old hand waist-deep in a hole, and wants to know where it is best to dig. If the digger had an answer to that, then of course that is where he would be—he wouldn’t be down his own current burrow on speculation.

The diggers will give advice to the newcomers, but of course it is a different matter when it comes to the physical labour. Not everyone is cut out for that. I wasn’t. Even less so was Coppin. And that clean-shaven look does not last long. Indeed, neither does the well-washed look. Diggers all turn shaggy and unkempt very quickly. A splash is enough for a wash; there is no point in anything more thorough, as in two shakes you are just as dirty again as you were. None of the diggers, nor the bushmen neither, is meticulous about keeping clean, though the married men might be scolded and sent off down to the creek from time to time.

There is no place for politeness on the fields. The diggers not only have to be prepared to toil hard in uncomfortable conditions, they have also to be prepared to defend their rights—as at Bendigo and Ballaarat—and to defend their claim. While the law is that a claim must be worked each day, a kind of customary understanding among the men is that leaving a tool, such as a pick or a spade, stuck into the ground marks that the claim is in fact owned. It is the means by which a digger can go off looking for another claim, or take a broken wagon to be repaired, or even to go searching for a strayed horse; the means by which it is understood he will be returning.

Sometimes what the American diggers call a ‘claim jumper’ might sneakily replace the implement by putting his own pick or crowbar into an attractive and unattended claim, and then make a big show that he is taking up his common right—and of course there is an ugly confrontation when the real owner returns. Fists as well as voices are raised, dogs start barking in all the heady furore, neighbouring diggers come running, or start calling out from their own shafts, and soon a crowd has gathered. It might be that general consensus decides the matter; or if more vigorous action is needed, they might combine to drive off an obvious usurper. On the other hand, they might form a ring and let the two parties settle the issue with their fists. That gives rise to cheering for one or the other, wagers exchanged, the crowd growing loud and excited in their encouragement; and the whole turns into a mill.

Or the fight might be arranged for the weekend, when a much larger crowd again assembles, forming a ring around the assailants, and watches them go at it toe to toe. A few of the spectators bring their sons, carrying them up on their shoulders, so that they can see what it is to be a man. I cannot imagine that is much of an inducement. Some spectators have their week’s supplies from the store in a bag up on their back. And of course there are those who come running so as not to miss the sport, and in their haste fall headlong over tools and barrows. The mill is not just contained at the centre of the crowd.

It amused me to set such a sketch alongside a different kind of mill, a Sunday preacher at an open meeting, where the assembly is of a different order entirely. Nobody comes racing across the field to attend this, nobody needs to carry his child on his shoulders, because the preacher of the day will be standing on a stump or on a barrel. Those who are in attendance listen quietly enough, but not everyone looks at him. Some gaze out across the camp, others show each other samples of what they have succeeded in fossicking out of what had been cast by the wayside, in my father’s figure of speech. Gleaned, he might have said. They are laying up their treasures in the world near at hand. Not far away, behind the preacher’s back but in line of sight of those who have gathered together, will be a customary ‘coffee’ tent, with a few sinners lining up at the back, seeking their own form of spiritual sustenance. In all my forays into and about the diggings, I do not recollect anyone ever recommending such a booth on account of its coffee.

The people on the fields are as various as any artist could wish. There are diggers who have come from a comfortable way of life, diggers of high degree I think them. Little gestures mark them out. Their claims are at a polite distance from anyone else’s. One of them might be sitting on an upturned tub, reading a newspaper with close attention. That is a more pressing concern to him than getting on with puddling in the tub. Another just emerging from the shaft wipes his brow with a remarkably clean handkerchief. You do not see many of those on the diggings. And a third member of the party is the same dapper figure who as the well-heeled new chum was asking questions of the old hand. He still has his hands in his pockets, and does not look like he is one to take them out, or not so as to handle a spade. He has his pipe too, wooden not clay. His elegantly bound sketchbook rests on a board just near where the ornate tea kettle and pannikin await the emerging worker of the three. It is all very unhurried; there is time for interesting if not very productive conversation.

By contrast is what I call diggers of low degree, wild-looking aggressive individuals, unkempt, with muddy trouser legs, always ready to perceive an affront, ever ready to put up their fists. Their faces are frequently flushed, whether from anger or from the empty black bottle lying on its side is of no particular account. They are spoiling for a fight. Axes and hammers have been thrown about their claim and lie where they fall. Their bucket is sprawled over on one side in a dirty puddle. At the first provocation it is off with their hat (which is lucky not to join the bucket) and up with their mauleys. Come on then, here’s havin’ at yer. And up pops a mate, younger but wiser, the very type of bare-faced cheek, his leather cap on back to front, taking up his place behind the fire eater and shouting defiance at all and sundry. They make enough of a racket between them to catch the attention of their neighbours, but nobody comes to see what is the matter. They have heard it all before.

Not a lot of gold gets dug out of that kind of claim either. Both sorts of fellows are bound to be disappointed, being what they are. No fault of their own.

Some diggers are successful of course. And not just in the way of those who have scraped away at the bottoms of their shafts with a knife, looking for elusive traces of gold, or little nuggets in the spoil everywhere about the diggings. That is a forlorn way of seeking a fortune; the odds are very much against it. No, a lucky few find a small seam of gold or a heavy showing in the silt along the creeks, and then they go rushing off cock-a-hoop with their gains, to celebrate their good fortune in the nearest town.

You can hardly miss them. They race off on recently purchased nags, bobtailed for the most part, hallooing and whooping and waving their bottles of beer about. They are on their way to the best champagne that money, or gold dust, will buy—and the wonder is that they ever arrive, whether in Ballaarat or Geelong or Melbourne. They are half drunk with excitement even as they set out, and before they have travelled far they are weaving about in their saddles. They make such a clamour as is sure to catch the attention of those nefarious characters who trust to a rifle rather than a pick to find their fortune. These foolhardy diggers are every bit as conspicuous as the gold escort, but without the strong defence. It is beyond credit, but in their madcap excitement at striking it rich, there is every chance they have forgotten to take a gun with them. You can only shake your head in disbelief at their absurd wildness.

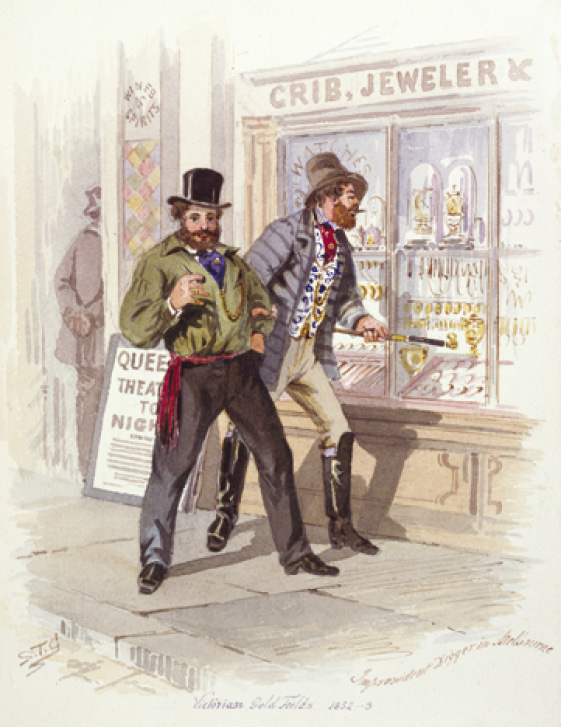

Still, enough of them survive the headlong dash to the towns, and there they set about laying waste to their recent wealth. They buy flash clothes, and large rings and jewelled pins for their cravats, though of course they would be more comfortable in their old jumpers. But for the time being they rig themselves out, as they call it, in whatever they imagine is the height of fashion—which is what they remember from before they left England. Their colourful sashes are their own contribution to the sense of style. They are a sight to behold.

And the publican makes sure they are provided not only with the drinks of their choice, but pert company to which they may find themselves attached fairly promptly. I have amended my picture of the new bride and groom going for a celebratory ride in an open coach, improving on the burlesque of elegance. The bridegroom and his best man now wear much bolder check coats, the bridesmaid’s folded fan becomes a glass of champagne, and the unblushing bride is a much more contained young miss; or was. I have given her a veil, which blows away behind her, and a scarlet dress for allegorical good measure. But chiefly I have made sure that the groom, meaning the driver, is a refined young man now wearing a waistcoat rather than tails; he is the sort of person who may once have been accustomed to riding in a landau and is now in the curious circumstance of having to drive it for the riotous wedding party. For truly, not only the landscape has been turned upside down by the diggings.

You see pairs of diggers, one with a cigar, the other with a gold-topped cane, both with more jewellery about them than is altogether advisable if they thought to step into the side lanes, but that is unlikely as they wish to make a splendid show where they will be most visible. Besides, the most glittering shop windows are in the main streets, so that they are safe from one kind of assault though not another. And it is a curious fact that they are most attracted to jewellers’ shops, to the great golden fob chains and signet rings with which they adorn themselves, and to the gold mantel clocks which would look just the thing inside their tent. They are attracted to the very gold that they have dug out of the ground. It tugs at them and will not let them go. The other distractions are temporary, like scenes at the theatre. Gold is what has drawn them from across the seas, and draws them still. It is in their bones.

I do not care to think of what I have in mine.

The more prudent diggers, nowhere near so ostentatious in their dress, but neat nevertheless, are drawn to a different kind of shop window, to where land is subdivided and offered for sale. For the price of property, especially near to the city, rises at the most extraordinary rate, and is really another kind of goldmine, one well worth the staking a claim so to speak. It grows its own wealth. The key to it all, as always, is to have sufficient wealth to enter the market in the first place. It makes me feel tired. It is exactly like the copper mine shares back in the old Adelaide days. Such investments are for them as has, and the rest of us are left out of it. The world is carved up by those with the biggest knives and forks.

And so I draw my own conclusions. The lucky digger dreams of returning to England and an easeful domestic life, with wife and children and dog, lucky dog, or perhaps he makes a version of that life for himself here, stretching out on a sofa with books and newspapers close at hand, and his wife sitting reading by the fireplace. No more campfires, no more staring into the embers. Dreams, dreams. The longer dream is that of the unlucky digger, who has laid his head down at the foot of a tree, and all that is left of his dreams are his bleached bones, and a gun useless to defend himself against the King of Terrors. Unlucky? An end to his tribulations, to the loneliness that overwhelms you here. That is how the book closes.

My dreams. My bones, my aching bones.