An Interview with Jonathan Lethem

LEAH PRICE: How far back does your collection stretch?

JONATHAN LETHEM: I guess I remember books in my room as early as I remember my room. At least two of those are still with me: my mother’s Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, a beaten-up wartime edition in yellow boards, but with a lavish interior—the Tenniel illustrations each given their own page and framed with a red border, which still seems the only right way to view them, for me. And, a translation of a morose French children’s classic, Sans Famille (translated as Nobody’s Boy), about an orphan boy who picks up some dogs and a monkey on the road and becomes a street musician. Then the dogs die, one by one.

I started haunting used bookshops when I was twelve or thirteen. There were loads of good ones even in downtown Brooklyn, nice old moldering places run by bitter book veterans, who remembered better days that may or may not have existed, or foolish optimistic gambits by eager young men, like Second Hand Prose on Flatbush Avenue, or Brazen Head on Atlantic, where at fourteen I apprenticed myself and made a lifelong friend in the eager foolish young man, Michael Seidenberg, as well as forging a career as an antiquarian bookseller—the only career, I like to say, I ever had before authoring. From the very beginning I took home as much of my pay in books as in pay.

Could you say something about the books you selected for our top ten?

I picked books I thought were lovely, strange, and unexpected. Which three words pretty well encapsulates what I hope to find when I open any book, as well as gaze at its outsides. This superficial way in is often fateful for me, in my life as a book hunter—something beautiful and peculiar lures me, and my brain, and my tastes, my writing life, my sense of what’s possible, is changed by the contents of the book.

Others here are books I haven’t read yet, but hope to (I won’t say which ones). People sometimes act as though owning books you haven’t read constitutes a charade or pretense, but for me, there’s a lovely mystery and pregnancy about a book that hasn’t given itself over to you yet—sometimes I’m the most inspired by imagining what the contents of an unread book might be.

Several of these—Guide for the Undehemorrhoided, Rock and Roll Will Stand—are the kind of books you might not know even if you thought you knew the particular author’s work well. The author’s secret books, the oeuvre behind the oeuvre. I’m obviously dedicated to things that are out-of-print, left-field, dubious. I like an air of privacy between me and a book, and often feel more comfortable with the lesser-known author, or the well-known author’s lesser-known book. If I’m reading Ulysses or Moby-Dick, I’ll resort to an unusual-looking edition.

The bookshelf, literally: what are your shelves made of? How did you acquire them?

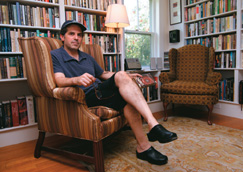

I’m a terrible aesthetic reactionary now when it comes to shelves; the only shelves, I’m tempted to say, are built-in shelves. I commissioned those that you photographed, the culmination of a lifelong materialist dream or fetish. They’re glossily painted wooden shelves, made to match the woodwork in a 150-year-old farmhouse. Or I’d ratify glass-fronted stacking cabinets, but I haven’t been able to afford to lay in a room full of those. I must be seeking security in my old age. When I was a kid my shelves were tottering Rube Goldberg structures, made of bricks, milk crates, other books, and salvaged scraps of lumber from my father’s carpentry shop.

How do you arrange, or attempt to arrange, your books? How do you know how to find them on the shelf, if indeed you do know? Does this resemble the way you arrange (or don’t) your music?

My books are always organized, arranged, and always being rearranged, too—a constant process. I tend to oscillate between alphabetical absolutism and imperatives of genre, subject, size, color, publisher—I don’t, for instance, ever like to see pocket-sized paperbacks with anything larger, and certain publishers have created spines so irresistibly lovely together that I’ve devoted sections to them, even when it busts authors I’ve got shelved elsewhere out of their alphabetical jail. And with the film and music books, I’m dedicated to clusters by subject—Orson Welles, say—alternating with clusters of favorite critics—James Naremore, say—who’ve often written on other directors who rate clusters of their own. So I end up with weird bridging continuums, like Welles/Naremore/Kubrick, or Dylan/Greil Marcus/Elvis/Peter Guralnick/Memphis soul.

Music is chaos, or strictly alphabetical, never anything in between. Chaos these days. Music also presents alphabetical problems you never encounter with books: where do you file LL Cool J? MC 900 Ft. Jesus? How about Little Walter? Does he go next to Big Walter, or nine letters away?

What proportion of the books that you read do you own? Do you lend your own books to friends?

I’ve got a lot of books I’ve never read—books I find charged and beautiful to pick up and consider, and might read some day, others I find charged and beautiful and wouldn’t ever bother. Extra copies of books I love in variant editions. Reading copies of books I’ve got in precious editions. I hate lending, or borrowing—if you want me to read a book, tell me about it, or buy me a copy outright. Your loaned edition sits in my house like a real grievance. And in lieu of lending books, I buy extra copies of those I want to give away, which gives me the added pleasure of buying books I love again and again.

Do you listen to audiobooks? Do you prefer reading aloud or being read aloud to?

Never have been able to do this. I like reading aloud to a child, or to a crowd in an auditorium (the right one, not just any), but apart from one or two stray and lovely moments with a lover, have never much sat still for being read to. I’m a hypocrite—I hate attending readings.

What do you imagine your library looking like five, ten, twenty years from now? Do you think you’ll still own objects made of paper and glue? And—with apologies for a morbid question—do you ever think about what will happen to your library after your death?

I’m almost fifty, and I doubt my library’s going to change its nature much again at this point, just grow and shrink and get tinkered with like an old car. I do think about where they’ll go after I die, constantly. I have an idea that I’ll create a marvelous specific annotated catalogue, indicating hundreds if not thousands of exact destinations for individual volumes or minicollections within the whole—but the odds are probably pretty poor that I’ll get to that, don’t you think?

Flann O’Brien At Swim-Two-Birds

Colin MacInnes City of Spades

Charles Willeford Cockfighter

Margaret Millar The Fiend

Christina Stead For Love Alone

Charles Willeford A Guide for the Undehemorrhoided

Vladimir Nabokov Lolita

Wilson Tucker The Long Loud Silence

Greil Marcus, ed. Rock and Roll Will Stand

Elias Canetti The Tower of Babel