Sheep Need a Shepherd

The gospel had come to Buffalo Flats in word, but without much power or assurance.

The circuit-riding days were over; there were regular Sunday services held in the little frame schoolhouse. But for ministers they were usually sent recent graduates of an Eastern divinity school which, to make use of the vernacular, was not onto its job. The young men who came out from it were less interested in grace and atonement than they were in molding utopian societies—they thought the Apostle Paul was all right in his own way, but rather old-fashioned, and were sure that improved methods of saving souls must have been developed over the last nineteen hundred years or so. Hence they usually began their ministry by instituting a temperance crusade, or exhorting the cowboys not to wear guns, or some other highly progressive method of putting the cart before the horse.

A man who did not (or would not) understand that .45s were not primarily for assassination, but for protecting livestock from predators, putting an injured animal out of its misery, or in the last resort shooting a horse that was about to drag you to death by your foot hung in the stirrup, was not likely to be listened to in Buffalo Flats on the subject of drink or anything else. Presently the social reformer found himself conducting services with a congregation of five women and four children, who came because he was all the minister they had. When the congregation dwindled to four women and three children, and puzzled defeat was discernible between the lines of the minister’s letters back East, he was usually recalled and another sent to take his place. Let us hope they learned something from their time in Buffalo Flats. For no one else did.

To anyone who does not believe in divine foreordination, the only explanation for Donald Matheson being sent to Buffalo Flats would be a mix-up. A spur-of-the-moment suggestion from an elderly doctor of divinity who was bothered by the run of failures in Buffalo Flats and happened to know that the grandson of an old friend was looking for a vacancy brought it about. Nobody in Buffalo Flats knew this. All they knew about Donald Matheson before his arrival was that he was twenty-six years old, that this was not his first congregation, and that he was already married with a small son, which at least sounded more settled than what they were used to. He had also bought the relinquishment of a homestead claim nearby and intended to live there with his family instead of boarding with members of his congregation as previous bachelor ministers had done.

All this was moderately interesting, but no one had any extraordinary expectations regarding him. In fact, one could describe the spiritual condition of the people living on the ranches and homesteads around Buffalo Flats as not having great expectations about anything.

Some inkling of this had already been gleaned by Donald Matheson and his wife, Marguerite, by the afternoon that they put the schoolhouse in order for Donald’s first Sunday service the next day. They had swept the floor, put spellers and slates away in the desks, and moved the teacher’s desk to make room for the small wooden pulpit that was kept in a closet during the week, and Marguerite was kneeling on a desk pushed over against the windows, her sleeves rolled above her elbows, washing a few upper panes that were not clean enough for her taste. Donald junior, eleven months old, sat on the floor in the corner by the pot-bellied stove building little towers out of satisfyingly grimy lumps of coal from the hod (Marguerite was a delightfully indulgent mother in some ways).

“Not hostile,” said Donald, senior, who was setting out the hymnals from a crate in the closet. “Everyone I’ve talked to has been as welcoming and obliging as new neighbors can be. No ridicule. Just simply not stirred in any way. It’s as if I was opening another store that they would come to, all right, but didn’t expect to get any bargains at.” He adjusted a battered hymn-book with a broken spine back into shape and put it on the next desk. “Along with an underlying assumption, I think, that coming out here as a green New Englander I should be a little scared of everyone and everything in Montana.”

“Or perhaps go to great lengths to show you’re not scared of everything,” said Marguerite over her shoulder, as she gathered up her cleaning rags and climbed down from her perch.

“No lengths,” said Donald firmly; “no lengths at all. I’ve got to simply be who I am, in church and outside it. If anybody expects me to adapt my preaching for ‘wild Westerners’—whatever that means—they’ll have to be disappointed. That’s one thing I never want to find myself doing, Marguerite: trying to tweak or tamper with the message in order to ingratiate or impress anyone. If there’s one thing I’ve been convinced of—maybe believed more strongly than anything else, ever since I first felt called to preach—it’s just that one thing: the gospel is sufficient. If I ever tried to preach in any way apart from that, I wouldn’t be any good for anything.”

Marguerite did not answer in words, but she stood on tiptoe to kiss her husband and straightened his collar, and there was a world of loving understanding and admiration in the gesture.

They moved back the desk she had used and set out the rest of the hymnals, and picked up the rags and the broom. “Is your sermon finished?” said Marguerite.

“Almost. I have an idea or two more that I want to put into it, but I got most of it sketched out yesterday and this morning.”

Marguerite collected the scattered lumps of coal and returned them to the hod, and gathered up her smudged offspring and hugged him. She had curly light-brown hair that she sometimes tried to smooth down, and an impish smile she sometimes tried to make more demure, thinking them not quite right for a minister’s wife; but she was never too successful, and people found her the more endearing when she did not. Donald loved her for these things, and many more substantial ones besides.

She said cheerfully, tickling little Donald until he giggled, “What’s the text? For your first sermon I daresay the congregation will expect something unctuously specific like ‘a stranger in a strange land,’ or ‘how beautiful are the feet of them.’”

“More likely ‘peradventure there be ten righteous within the city,’” said Donald. He swept around the stove and put the broom away in the closet. “But that’s a bit previous, as they say out here—besides predictable. No, I think I’ll shock them.”

And so on the following morning, when the new minister took the pulpit for the first time before a church about half filled, he opened his sermon with the startling text, “Let all those who put their trust in Thee rejoice; let them ever shout for joy because Thou defendest them.”

He then proceeded to explain very clearly why those who trusted in Him had a right and a cause to rejoice—and those who did came away from the service a little astonished, as if they had been shown a treasure they did not know they possessed. And as Donald Matheson was shaking hands with his new parishioners at the door after the service, a well-dressed woman of about forty-five with a faded, once-handsome face came up to him and offered her hand with a marked look of gratitude.

“I am Mrs. Glenn,” she said. “I am very glad to meet you, Mr. Matheson. And I want to thank you. It has been a long, long time since I heard a sermon like you preached today.”

They chatted cordially for a few minutes—Donald introduced his wife, and Mrs. Glenn her daughters, two nice-looking, well-mannered girls in their teens. They spoke of the township, and the church building, and Mrs. Glenn reiterated before they parted how pleased she was to welcome the Mathesons as neighbors; but Marguerite noticed, woman-like, that she did not invite them to call or to dine, as one might have expected.

She mentioned this to Donald as they were driving home afterwards.

“She wasn’t obliged to invite us,” said Donald, with a man’s practicality. “There could have been any number of reasons why she didn’t. Perhaps she’s not very well-off and isn’t able to entertain.”

“My dearest boy, did you see the stuff her dress was made of? Well, no, I suppose you didn’t. But anyway, I’ve already heard the name. Her husband owns one of the largest cattle ranches roundabout here. She didn’t mention him, either, did she?”

There was a good congregation for the second Sunday, and the one after that. In the weeks between, Donald Matheson drove into town a couple times and made some purchases of wire and lumber for repairs on his homestead. To all appearances Buffalo Flats’ new minister had settled smoothly, and in a practical sense unremarkably, into the community.

And then one day he gave them a genuine shock.

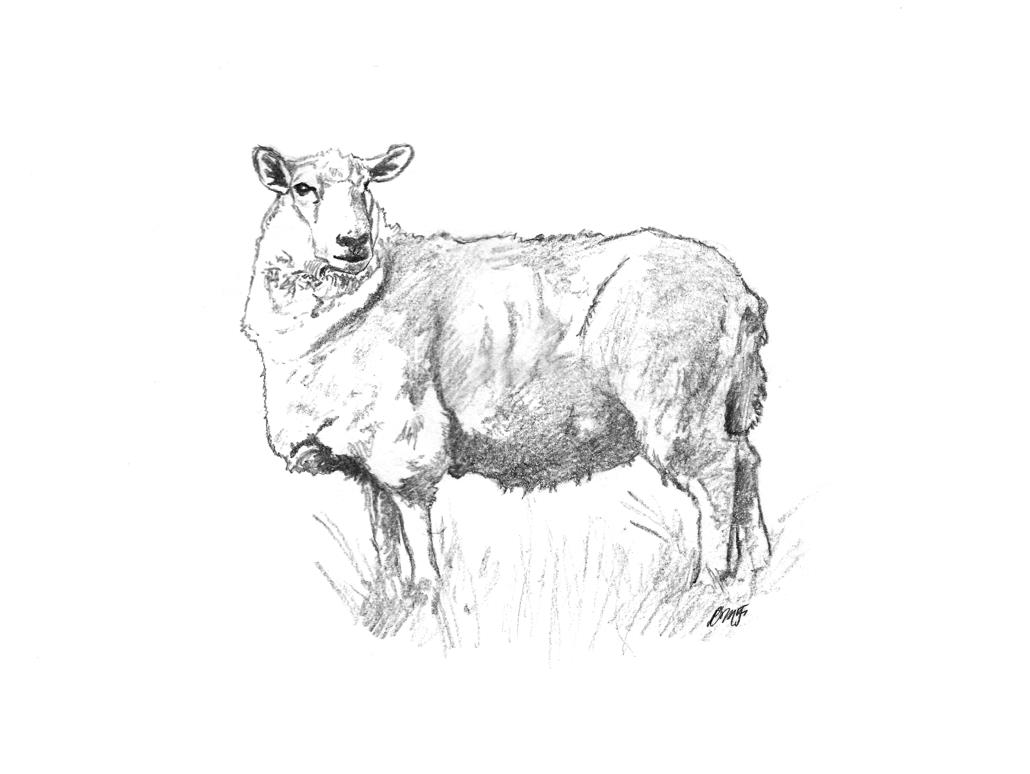

One fine morning a little over two weeks after Donald Matheson had preached his first sermon in Buffalo Flats, two cowboys from the Glenn ranch were riding in towards town. At a bend in the road where the ground sloped away on the right into a long, shallow draw, they heard a faint, discordant sound drifting up towards them that made them stop and look at each other, and then by one accord turn their horses off the road and lope in that direction. They rounded a low swell of prairie ground and pulled up. A large bunch of sheep, a flat, crawling dingy-white cloud of wool and bleating, was moving slowly along the draw, with two herders on foot bringing up the rear and a couple of dogs circling.

“By all that’s rotten,” said Bat King disgustedly. “How long’s it been since a sheepherder dared put a hoof on this range? Let’s make short work out o’ this one.”

Tom Mullen showed his teeth in grim agreement. They put spurs to their mounts and pounded down toward the flock, bits of prairie sod flying up from the horses’ hooves, and reined up just short of a collision, making the sheep shy in bleating fright like a white wave leaping back off a shore. Bat King directed a stream of profane invective toward the herders. “Hey, you flea-bitten, blankety-blank son of a lop-eared so-and-so, get your mangy critters off this range. What d’you think you—”

He choked off in confusion, for as he swung his pony around to confront the herders more directly, he had made the discovery that one of them was Buffalo Flats’ new minister.

“Uh—beg pardon, Parson,” he stammered, taken aback. “Didn’t mean to—that is I didn’t see—”

“Good morning,” said Donald Matheson equably, hiding his amusement. “We’ve met before, haven’t we? Bat King, isn’t that right?”

Bat, who had met Matheson once in town and exchanged a few commonplaces with him, acknowledged it with an embarrassed nod and gathered up the scraps of his composure. “No offense to you, Mr. Matheson,” he said. “I guess you were doing the Samaritan helping this Swede move his veal carcasses. I s’pose nobody’s put you wise yet about the poison nature of sheep. You ain’t obliged to be kind to sheepherders, though I s’pose you can pray for ’em if you like—in fact, there’s a strong policy against ’em. Now, I reckon it’ll disturb your sensibilities less if you just go on over that hill yonder while we deal with this bunch.”

Donald Matheson had listened to this speech with growing surprise and comprehension. A glance from one cowpuncher to the other showed they were quite in earnest—they could not imagine any other reason for his being there.

Tom Mullen added amiably, “Don’t worry, Parson, we won’t hurt him much. Anyways, they like being run off, else they wouldn’t come onto cattle range.”

“I’m afraid you’ve got it the wrong way around,” said Donald, with a slightly rueful smile. “I’m not helping Mr. Swenson; he’s helping me. These are my sheep. I just got them off the train at Buffalo Flats this morning, and Swenson is helping me trail them out to my place and get accustomed to working with the dogs. Don’t trouble him; he’s not responsible for them any longer.”

“Your sheep!” said Bat King, staring. He glanced incredulously at the milling creatures with their placid low-browed woolly faces, exchanged a dumbfounded look with Tom Mullen, and both of them looked at the minister again. “You mean you’re planning to run sheep on this range?”

“On the government range over beyond my homestead, yes.”

“A sheep-runnin’ preacher!” said Tom Mullen in a tone of mingled amazement and outrage; “if that isn’t the dam—the most consarned—”

Bat King cut him off with an exasperated look. He could think of nothing suitable to say himself, however, and Donald Matheson took advantage of the pause. “Well, we’d better be getting on. Good morning, boys. I’m sorry about the misunderstanding!”

He whistled to the dogs, who, with some added prompting from the Swedish herder, made a series of darts at the bunched sheep and started them moving again. The cowboys hung back, annoyed, irresolute, with no idea what else to do. Not till the rearguard of the sheep and the men on foot had moved on about twenty paces did Tom Mullen turn on his companion in irritation. “We just let them go? Let a bunch of sheep—”

“I know it’s sheep. But what you gonna do? Stampedin’ a bunch of sheep belonging to a preacher—I ain’t undertaking that on my own responsibility. Come on. Least we can do is tell the boss.”

The upshot of which was that two days later, Henry Glenn himself came riding out alone to the Matheson homestead.

Glenn was a man who looked younger than his nearly fifty years, limber of movement as he swung down from his tall bay horse, his hair still dark and the only lines in his taut tanned face the fine lines of sun and wind. His broad build would have been called stocky if it were not for the height that made it imposing. He found Donald Matheson by the sheep pens he had repaired and extended from an existing corral, where at the moment his bleating flock was confined.

Glenn introduced himself briefly. “Mr. Matheson? I’m Henry Glenn.”

Donald shook hands with him; the rancher’s grip was casual but strong as iron. “I’m pleased to meet you, Mr. Glenn; I’ve heard a lot about you.”

Glenn nodded shortly. He glanced sideways at the milling sheep in the pen. “I’ll come right to the point, Mr. Matheson. I’ve been told you intend to run a bunch of sheep on the range around Buffalo Flats. I take it that’s true?”

“Yes,” said Donald. He leaned his elbow on the slatted fence. “That’s been part of my plan since I decided to make the move out here. It’s what I was raised to, you see. I come from a long line of farmers, or farming ministers rather, back in Vermont—my father and grandfather both bred sheep and I’ve been accustomed to them since I was a boy. I knew this was grazing country, and so I decided to run some livestock myself. It’s a way for me to support my family without putting too heavy a burden on a small church congregation.”

Glenn listened with little apparent emotion. “If you knew this was grazing country, you also likely knew it was almost exclusively cattle country round about here. Were you aware that the average cattleman hates sheep like he hates poison?”

“Yes. Oh, I went into this with my eyes open. I knew raising sheep might not just be a popular choice. But I’m no cattleman, Mr. Glenn, and a man makes his living at what he’s bred to. And with my own hundred and sixty acres plus access to the government range to the south, I’ve no need or intention to encroach on any grass or water that I don’t have the right to—”

Glenn interrupted him. “I didn’t say you had. It’s not a question of how you go about this, Mr. Matheson. I’m saying I don’t want you to succeed at it in any way, shape, or form. I don’t want to see you raising sheep in the neighborhood of Buffalo Flats whether you lease, own land, or run on open range. I don’t want you to succeed because your doing so will embolden more sheepmen to move into cattle country, into an area we’ve kept them out of for a long time.”

“Well, that’s plain enough speaking,” said Donald, smiling a little.

“Yes. You understand me, Mr. Matheson, so I won’t beat around the bush with you. I didn’t come out here to drop hints or give nudges. I came here to ask you straight out to give up this idea and sell your sheep right away.”

“And I think you came expecting me to easily agree.” It was a statement, yet at the same time a slight pointed question.

Henry Glenn’s expression changed a little, as if he was trying a different approach. He leaned against the fence beside Donald and pushed his hat back, his voice taking on an ingratiating tone. “Look, Mr. Matheson, I think you may be underestimating the sentiments of cattlemen hereabouts. We’ve had sheep wars here where both men and animals were killed. That may be behind us, but the feelings haven’t changed. You may think it’s just me, but I can tell you all my neighbors feel the same, and you’ll find it out for yourself before long. You’re new here, you’re a minister who wants to make friends with these people. Don’t you think you’ll make that harder for yourself if you persist in something they’ll resent you for?”

“I’ve never seen it as part of a minister’s task to soft-soap people into church.”

“Well, maybe not, but why stack the odds against yourself? And don’t think you need to rely on this to make a living, because—”

Glenn stopped. You could be pretty sure of the cattlemen putting a bigger contribution in the collection plate if you oblige them, he had been going to say, or words to that effect; but somehow, looking into this young man’s steady, open face and the level gray eyes that did not seem to miss a word or tone, he felt in full force the offensiveness of what he had been about to say.

Stung by this recognition of baseness in himself, he reverted to his usual abrupt manner. “Don’t you think it would be more the Christian thing to do, to give this up at our asking? It seems to me that’s a pretty big part of your creed—‘love thy neighbor.’”

Donald said quickly, “‘As thyself.’ Those two little words aren’t applied very often. Loving one’s neighbor doesn’t mean doing exactly what he wants whether you think it’s right or wrong. Much of the time that would mean cheerfully seeing him off on the road to hell. To me, loving one’s neighbor primarily means wanting him to do what’s right—to have every opportunity to choose what’s right. And that isn’t what you’re asking of me, Mr. Glenn.

“Think about it: if I make a voluntary concession that benefits you, just to earn your goodwill, won’t I set a precedent for you to claim a moral right to strong-arm any other man who wants to use his range in a way that you don’t see fit? And isn’t that man equally my neighbor?”

“Listen, Matheson, who appointed you an advocate for sheep?” demanded Glenn.

“I’m not. I just think that a man who’s been blessed with the right to choose what he believes is best should consider, any time he makes a concession, how it’ll affect the ability of other men to have that choice. If you were in my place, wouldn’t you do the same?”

Henry Glenn had admittedly expected deference, had expected his own conception of ministerial meekness, had indeed expected a reasonably quick agreement to his demands; he had not expected to be faced with a philosophical or theological debate. He was ready enough to admit that he believed in preserving one’s rights, but he had always regarded a Christian as a sort of unworldly vegetable who renounced all claims to fairness and justice. The discovery that Donald Matheson was not such a one meant that he had to be careful about invoking fairness or justice to bolster his own position.

He fell back on a more well-worn argument. “It’s a more practical question we’re discussing here. And if you want my honest opinion, I think you’d do much better not to mix your religion with your ranching.”

Donald laughed outright. “Mr. Glenn, only a minute ago you were quoting Scripture at me and saying it ought to be the grounds for my decision. Wouldn’t it be more accurate to say, you don’t really care whether I mix my religion and business or not, so long as my choices happen to coincide with your way of thinking?”

This was again a little too close to the truth. Glenn spoke shortly: “I don’t much care what you do with it. I only despise a man who uses religion as a cloak for getting and doing what he wants.”

Donald Matheson came of a long line of God-fearing Scots as well as farmers and had more than a touch of red in his hair, and there was a certain light in his eye as he replied, with all other appearance of restraint, “So do I. That isn’t what I’m doing. I didn’t choose to raise sheep because I’m a Christian—my belief in God didn’t dictate that I should cross you. But so long as I’m not breaking the law or actively harming my neighbor, my conscience doesn’t give me any reason to change my course.”

“And that’s your answer?” said Glenn, studying him. He had moved away from the fence and stood with hands on hips, his brow furrowed in displeasure.

“Yes, Mr. Glenn, that’s my answer.”

Henry Glenn nodded. His eyes swept the younger man up and down, as if measuring or estimating something. “Well, we’ll see,” he said.

He turned away to his horse without another word. He mounted and swung the bay around, checking it just long enough to take his leave with a curt nod and touch of his hat. Then he slackened the reins and the smooth-stepping bay carried him swiftly away. Donald Matheson stood for a moment and watched him go. Then, after a brief glance at his penned sheep, he went to the house to fulfill every man’s duty by reporting the conversation to his wife.

“I hope it’s principle speaking, and not my native obstinacy,” observed Donald, as he concluded, “but I never have appreciated being told what’s the Christian thing to do by people who aren’t Christian.”

“Then you think Mr. Glenn isn’t—?”

“No. It’s in his every word and look. He’s the type of man who thinks religion is a harmless fairytale that women like to play at on Sundays—harmless so long as it doesn’t interfere with him, of course.”

“That explains a good deal, doesn’t it. Poor Mrs. Glenn.”

Marguerite added, after a minute, “What do you think he’s going to do?”

“Do?” said Donald. “Oh…well, yes, I suppose he has to do something. I don’t think he wants to use the old rough methods. He’ll look for a more civilized way to force me out first. But I’m not going to spend my time worrying about it. I have sermons to write, livestock to graze, and one”—Donald paused and stooped to drag out his son who was attempting to crawl under Marguerite’s ironing-board—“one growing boy to keep out of trouble.” He swung his small namesake up on his shoulder like a sack of wool, and little Donald threw back his head and laughed before settling down to do some teething on his own stubby fingers.

Marguerite hesitated for a minute, then set down her iron and turned to look at Donald. “Do you think he’s right, at all, about putting up unnecessary barriers to reaching people? Because you should know I’d never reproach you for any practical reasons if you did decide to give up the sheep. I’ve never been afraid of living on a very little.” She studied his face earnestly. “I’d only be upset if I knew you were going against your conscience for my sake.”

“No,” said Donald, as serious as his wife. “I don’t. For one thing, I don’t set as much store by Glenn’s amateur psychology as he thinks. I don’t think the people in this country would be more inclined to respect someone who gave in at the first sign of pressure merely to curry favor.”

“It sounds as if Henry Glenn thinks they hate sheep more than they respect principle.”

“That seems to be his own view,” agreed Donald slowly. “As for the rest…I don’t know. I guess we’ll find out which of us is right.”

Over the next few weeks Donald saw no more of Henry Glenn, but from the behavior of others he met he knew the word had gone around. In town he was conscious of certain glances from cowboys who passed him and of men discussing him sotto voce behind his back, and of slight undercurrents in the church dooryard among some members of the congregation who lingered to socialize after Sunday service. One or two other cattlemen tackled him directly about the sheep, in a half-grim, half-jollying manner, as if they thought that by being more tactful they might succeed where Henry Glenn had failed; but they all found the young minister unfailingly good-humored but quietly unmoved. The way they abruptly gave up arguing at a certain point suggested to Donald that this tactic had only been a long shot anyway, and that sooner or later they would take some more tangible method of making him see reason.

His suspicions were confirmed the first time he drove his sheep out on the range beyond his homestead, bound for grazing on open land to the south. The shortest route lay through an unfenced section leased by the Glenn ranch but commonly crossed by anyone moving livestock, following the course of a creek down a shallow coulee. But when Donald Matheson reached the head of the coulee with his flock, he met an obstacle in the form of Tom Mullen, sitting easily in the saddle with a Winchester in his hand, the stock resting negligently on his knee.

“Sorry, Parson,” he said, “you’ll have to find another way. This is Glenn range, and no sheep come on it.”

“Well, that’s within your right to say,” said Donald, “but are you sure you want to enforce it? We don’t intend to take your grass or your water, merely to pass through, turning neither to the right hand or the left.”

Mullen was no Old Testament scholar, but he had a vague idea he was being laughed at. “Boss’s orders,” he said stiffly. “We’re not to let any sheep through here. Not for any reason.”

“Fair enough,” said Donald, and whistled to his dogs. They turned the sheep, who jostled and bleated protest for a moment before falling into trotting step, bearing away east toward another gap in the hills.

A few miles into this detour, a cheerful individual also equipped with a rifle dropped down from his perch in the drooping branches of a cottonwood and informed the shepherd that he rode for the Harley outfit, and that all the land east of the creek belonged to that outfit and was forbidden to sheep. Donald thanked the cowpuncher for the information, they exchanged pleasantries about the weather, and the bunch of sheep moved off on a new course yet again. The cattlemen’s strategy was clear. They were remaining strictly within their legal rights, but meant to make life as difficult for him as possible.

So perhaps to certain people’s disappointment, Donald Matheson simply settled into living by the letter of the law. The ranchers could not block him off entirely from government land, but could make him take a long circuitous route to reach it: so he did. The homesteaders around Buffalo Flats grew accustomed to the sight of the young minister tramping after his sheep across the prairie, a knapsack over his shoulder carrying his lunch and half a dozen books. For long peaceful hours on weekdays he sat on a rock or a knoll near his flock, reading and studying for next Sunday’s sermon, glancing up now and then to see that the sheep had not scattered too far and that the dogs were attending to their duty. It was a life that suited him, for so he had spent his early youth, sitting on the stone wall of a green Vermont pasture laying the foundation of his education by reading his grandfather’s Calvin and Augustine and Edwards in between farm chores.

For the first week or two, each time he moved his sheep he met near every formal or informal boundary an amiable, often sarcastic cowboy sentry with a reminder for him—but after a while, as it became clear that he had no intention of arguing the point or taking his flock where he was forbidden to go, their attentions slacked off somewhat.

Near Glenn range, though, he was aware of a persistent, almost aggressive watchfulness from riders who did not directly approach him but never let him pass unobserved. Donald sensed they were eternally waiting for him to make a false move, and their antagonism increased the longer he did not.

One afternoon as he was trailing his sheep homewards Donald became aware that he was being shadowed by a single rider moving along the top of a ridge on his left, almost parallel with the bunch of sheep. By now he was used to being watched, but this rider’s persistence in trailing him seemed more pointed than usual. He paid no notice for a few minutes, then glanced up at the ridge again. The rider was still there, holding his horse to a walk and watching the sheep narrowly. On impulse Donald waved a friendly hand and kept walking as if he had given the horseman no more than a passing thought. Almost instantly the rider wheeled his mount and dropped down from the ridge, and rode straight toward him. In a moment he caught up to the flock and pulled up alongside the man on foot—a lean dark youth whose resemblance to both parents gave Donald a good guess at his identity. There was a hostility in his look and manner that spoke of someone looking for an excuse for confrontation.

“Something you wanted?” he said.

“No…though I did wonder if there was something you did.”

“If I was to say what I really wanted, it’d be to see your sheep at the bottom of a cliff somewhere.”

“I try to avoid that,” said Donald, slinging his knapsack half off his shoulder as he stood still for a moment. “You’re a Glenn, I’m guessing?”

“Yes. Terry Glenn. You’ve talked to my father already—though I think he was even a little too soft with you.”

Donald chuckled wryly. “Well, you’re both honest; I can’t fault you for that.”

Terry Glenn caught up the words quickly: “What do you fault us for?”

“I haven’t said I faulted you for anything. I’ve never looked for a quarrel with you, you know. Perhaps that’s—what you fault me for?”

An angry flush stained the dark, resentful young face. “You hide behind being a preacher. You know you don’t have to lift a finger to fight, and what’s more cowardly than that?”

Donald Matheson shook his head. “That’s where your father was wrong, and that’s where you’re wrong. I don’t claim any special protection. I’m a man, not so much older than you; I’m a stock rancher; I’m an American citizen. Whether you choose to treat me differently because I’m a preacher is up to you.” He looked straight into Terry Glenn’s eyes. “If I wasn’t a minister, what would you do right now? Run my sheep over the nearest cliff and feel you hadn’t done wrong?”

Terry Glenn stared back, his jaw gritted in silent hostility. He had swept in intending to provoke, and if he had succeeded he would have struck back with a relish and without a trace of interference from his conscience. It had worked for him often enough before. Hot-blooded, used to his own way or a swift open fight for it, he was not accustomed to being forced by another man to take a look at himself.

Donald Matheson nodded, studying him thoughtfully. “I thought so. But I’m honestly curious, Terry: why could you bully any other Christian man with a clear conscience? Is it just human convention, or would you genuinely fear a worse punishment from God for laying a hand on a man ordained as a minister?”

“I don’t fear your God at all,” said Terry Glenn contemptuously.

“I’m sorry for that,” said Donald Matheson quietly, without a trace of humor. “I’m sorry for you. You’d do better to fear Him than the conventions of any of your fellow-men.”

“Oh,” said Terry, “so that’s it. You think because you believe in God, that puts you above the law.”

“Not a bit. I’m breaking no law. And I’m not asking for special treatment. What you folks need to get through your heads is, I’m not claiming for myself anything more than I’d defend any other man’s right to do.”

“It’d take a long, long time to convince this country that a man has a right to run sheep,” said Terry Glenn, “and a few thunderbolts from heaven besides.”

Donald shrugged lightly. “I’ve got time. And I have other work to do.”

“You’d better wait and see if you do,” said Terry Glenn a little strangely. He wheeled his horse, flicked his quirt across its flank and was off at a lope up over the ridge of the prairie.

Donald Matheson stared after the swiftly receding forms of horse and rider for a long moment before moving on. He had spoken no empty platitude when he said he was sorry for the boy who had faced him with such antagonism. Those bitter, dark young eyes were the eyes of one who did not fear God or man. And only the man who knows God can fully understand the emptiness of being without that knowledge.

“They say he’s a great trial to his mother,” said Marguerite soberly, as they sat together that night, in silence for a minute or two after Donald had related his day’s adventures. “He drinks too much and has a hot temper, and he’s been on the edge of getting in serious trouble a few times. He and a friend almost killed a man once, during that last sheep trouble a few years ago, and Henry Glenn had to spend a lot of money to get him out of it even though the man lived. And he won’t have anything to do with church or with God—I suppose he follows his father in that. Mrs. Glenn loves him terribly, of course, but that makes it so much the worse.”

“That’s the hardest position I can ever see anyone in,” said Donald. “There’s so little I can do for her.”

“You do more than anyone else can. You know how much she values hearing your preaching, and that must be some comfort to her.”

“I hope so.”

The cattlemen were not resigned to their apparent failure. Conferences were held at which tempers sometimes frayed and patience ran short. Terry Glenn and a few impatient spirits wanted action, but Henry Glenn remained firm. “No. Running his sheep or shooting them won’t do anything but make him more convinced he’s in the right. Better to make him an outcast—he won’t want that while he’s trying to grow his precious church. If it’s a choice between that and the sheep, he won’t choose sheep in the end.”

So Glenn’s prescription was followed, and before long Donald Matheson felt the effects of it. Men who had greeted him cordially when he first came to town now gave him only a cold nod in passing, or turned their backs and began talking to someone else. Most notably, half a dozen ranchers’ families stopped attending church altogether—and he knew this was where they meant to hit him hardest. Not in the collection plate; that made little difference to him; but it was hard to watch what had been a robust congregation turn to a skeleton in one Sunday, to see the empty places at the desk seats and hear the echoes of the little schoolhouse. It was hard; but Henry Glenn had again miscalculated in not realizing there was no man better fitted to endure it. He did not realize that a minister of the gospel is the last person in the world to be surprised or shaken by ostracism.

And slowly an odd thing began to happen. The congregation which had dwindled so small for a week or two began to grow again on its own. The homesteaders’ and tradesmen’s families who had no stake in the sheep quarrel remained, and as stories about the feud spread, more people began to come from miles around—some because they were just now hearing of a church nearby, and others, some of them even cattlemen whose range was too distant to be affected by the sheep, because they were curious to see the minister who had dared to defy Henry Glenn.

What they saw, as they sat crowded shoulder to shoulder at the scuffed schoolroom desks, was a young man of medium height and build with almost-red hair, rather large hands and a not handsome but pleasant face, standing up behind the little wooden pulpit in a quiet dark suit plainly cut but well-fitting (Marguerite saw to that). He looked rather like a well-dressed young farmer on a Sunday, which in many respects was exactly what he was. What they heard, after they had come to look, was the gospel of Jesus Christ straightforwardly and earnestly preached. Contrary to what some expected, Donald Matheson never once used his pulpit to criticize his adversaries outside the church, but went on steadily preaching for the handful of the elect who had long been starved for the hearing of the Word. And many who had only come to look came again to listen.

It was Almira Glenn who suffered most from the feud, though silently, as she had always done. She took no part in the ranchers’ boycott, but attended church as always, and she knew her husband and son both believed this was tantamount to taking Donald Matheson’s side in the sheep quarrel. Terry had said so openly, resentfully; Henry Glenn’s silence said it just as plainly. The atmosphere of the whole household was strained: Terry had quarreled with his sisters, Glenn had spoken harshly to his youngest daughter, who shut herself up in her room in tears. The stalemate went on, and misery reigned.

One hot, close night, the Mathesons were awakened by the dogs barking. It was an overcast night, and dead blackness wrapped the house inside and out, which made the sounds coming through it seem that much more harsh and uncanny. The sheep were bleating loud and anxiously, and there was a clattering sound as if some of them were throwing themselves against the slats of the pen.

Marguerite’s voice sounded frightened. “What is it?”

“I don’t know. Something’s after the sheep.” Donald was up, dressing hurriedly in the dark. “I’m going out to see. Don’t come out unless I call you—and keep the light low.”

Marguerite crawled out of bed and groped for her dressing-gown, dragging one sleeve on over her shoulder inside-out, and followed him to the bedroom doorway. “Donald, be careful!”

Donald pulled down a dark lantern from a shelf near the front door, lit it, and shoved the slide almost closed so it cast only a dim bar of light, just enough to see a step or two ahead. The bleating of the sheep was growing louder and more chaotic, and as he opened the door he heard the pounding of horses’ hooves, and the crack and clatter of a gate flung back. Whistles and yells mingled with the crescendo of terrified sheep’s voices, and then the thudding rumble of hundreds of small hooves told him that the sheep were spilling out of the pen. He ran toward the noise. He could see nothing except a dim cloudy mass that was the sheep’s white wool, melting away and streaming crookedly together again in their flight into the night. The dogs were still barking frantically, one voice a little distant as if it was trying to stem the tide of stampeding sheep. Closer in front of him Donald heard a horse’s hoofbeats, a quick scrabble and patter and the choked-off growl and snap of a dog nipping at its heels, a shrill neigh and a skidding break in the rhythm of the hooves and a dull thud. The horse fled past him; the dog tore after it still barking.

Donald’s mind did not immediately register the meaning of the sounds. He was making for the gate of the sheep pen, not because he thought there would be any sheep left to shut in, but as a landmark to get his bearings in the sea of darkness. A few steps from the fence he heard a footstep almost at his elbow; he jerked toward it and the strip of light from his lantern showed him a half-second’s glimpse of a man seeming to lunge at him in the dark. Neither had expected the other. Donald’s reaction was pure reflex. He swung out with the lantern—it struck with a sickening crack and there was a gasping grunt and a heavy fall.

Donald staggered and regained his balance, and stood frozen for a second, seized with a kind of horror at not knowing who he had struck in the dark or what damage he had done. The lantern had gone dark—stooping over where he thought the fallen body must be, he pushed open the slide, but the flame was out. He found a match and struck it—it took two, three tries with unsteady fingers. The lantern lit at last, he held it down to search the ground. Its sickly glow found Terry Glenn’s upturned face, the blood oozing from a jagged cut across his forehead. He was stirring slightly, turning his head slowly to one side as if just beginning to come around.

The dogs were still yelping in the distance, and the distressed deep voices of the ewes floated back like feeble old men yelling hoarse complaints. There was no sign or sound of the other horsemen, who must have decamped after scattering them. Donald hung his lantern on the gatepost and knelt down, got his arm under Terry’s shoulders and lifted him, shaking him a little to jar him further back to consciousness. With some effort Donald got him up on his feet, took Terry’s arm over his shoulders and moved toward the house, half guiding, half supporting him. His insides churned hot and quivering with conflicting emotions. He was humanly, justifiably angry at the attack on his sheep, and more unreasonably angry with himself for having been startled into injuring someone. He felt Terry had deserved it, yet bitterly regretted it.

As they neared the house he raised his voice cautiously and called to his wife. Marguerite, who had been waiting anxiously behind the crack of the door, opened it wide, and as the light from the low-burning lamp fell upon them she gave a low exclamation. She came out and took Terry’s other arm, and Donald explained in a few hurried words what had happened as between them they got him into the house and put him into a chair. He was conscious enough to sit, though still dazed and half slumped over. Donald brought him some water, while Marguerite fetched the iodine and sticking-plaster and some clean rags. By the time they finished doctoring the cut on his forehead Terry was more aware of his surroundings, enough to wince at the sting of the iodine, but sat still, breathing heavily.

“It’s a bad cut,” said Marguerite gently, the first words any of them had spoken since they entered the house, aside from a murmured exchange or two between the Mathesons over their first aid. “It may need stitching. You should see a doctor.”

“I’m all right.”

“Well, let me close it up with sticking-plaster at least. Hold still, it’ll only take a minute.”

Donald sat down on a chair opposite and watched them, his hands on his knees. His hair stuck up all awry and looked redder than usual in the lamplight; his cuffs were damp and one of them smeared with blood. Terry’s eyes met his—though too shaken and subdued for open hostility, his expression was still sullen.

“I’m sorry this happened,” said Donald.

“Don’t play hypocrite,” said Terry roughly. “If you think you’re going to get me to go down on my knees and beg pardon by pretending to be too good for this world, you better think again. Sorry!” He laughed.

“Yes, sorry!” said Donald, coming abruptly up off his chair, his voice louder than anyone in Buffalo Flats had ever heard it. “I’m sorry my sheep have been scattered, frightened out of their wits and some of them probably injured. I’m sorry some probably halfway decent men have stooped to violence and lawbreaking, and I’m sorry I hurt you, even though you may find that the hardest thing to believe.”

He turned away and stood with his back to them for a moment, and blew out a breath of exasperation. Marguerite, standing silently in her dressing-gown behind Terry’s chair, watched him soberly. The single oil lamp filled the room with the garish brightness that any light seems to cast in the middle of the night, but Donald’s averted face was in shadow.

After a minute he turned around and faced Terry again. “I haven’t asked anything of you,” he said. “I’ve never asked you to love my sheep or to love me—or even to like me. All I hoped for was a little fairness.”

He ran a hand through his rumpled hair with a short sigh. “I didn’t expect it, I didn’t demand it, but I’d hoped my neighbors might give me the same fairness I offered them. I can at least listen to my neighbor’s different opinion, I can respect his holding it out of conviction even if I can’t agree with it—”

Terry lurched upright, catching his breath sharply as the motion sent a stab of pain through his throbbing head. “That—from you! Why, your whole business is telling other men how to live their lives!”

“You’ve got that all wrong,” said Donald swiftly, seriously. “I tell men how God says they are to live their lives, and leave them to make their own choice whether to obey or defy Him.”

“And threaten them with the consequences if they don’t!”

“Consequences from God, Terry, not from man.”

Terry made a sound of disgust through his teeth and turned his head away. Marguerite, finished with her work, quietly gathered up the odds and ends of sticking-plaster and rags and the medicine bottle and turned away with them to the cupboard. Donald stood silently for a moment with his eyes fixed on the boy’s face: a scrutiny Terry must have been conscious of, but he would not look up.

Donald started to turn away again, and then on impulse he swung back. “Why is it so hard for you to accept that I don’t hate you?”

At that the dark angry eyes snapped to his, but there was no reply. “I thought the men of this country could respect even an enemy, so long as he dealt fairly with them—but you, Terry Glenn, don’t respect anyone unless he fights with as little conscience and as much hate as you do.”

The silence in the room was like one after the explosion of a bomb. Donald, with the attitude of one who has finished with a subject, went over to the table and picked up the pitcher of water and poured himself a glass full. The hot closeness of the night, the wavering lamplight, held an almost nightmarish quality the longer the silence stretched out.

Donald broke it in a natural tone that flattened the tension in the room. “I suppose your horse is still around somewhere outside. Or if not, your friends will be looking for you.”

Terry’s voice was less harsh but still had an underlying note of belligerence. “Aren’t you going to turn me over to the sheriff?”

“No. Not tonight.”

“Why not?”

“I’ve got plenty of reasons. I’ve already given you a crack on the head; if I don’t want any more trouble with you tonight I don’t see why you should complain.”

Terry scowled, but he got slowly to his feet. He paused for a second as if to test his balance, and moved unsteadily towards the door. As he turned he met Marguerite’s eye for a second and gave the briefest nod of reluctant thanks, which she quietly returned.

By the door he halted and glanced back one more time at Donald Matheson, but this time Donald did not look toward him. He opened the door and went out into the night.

Before dawn Donald was out looking for the scattered sheep with the one dog who had come back to the house alone. He found the other dog around daybreak, limping on a hurt paw but guarding a small bunch of the sheep it had found and held against a cut bank. It took most of that day, a blazing hot Saturday, and many weary miles on foot, to find the rest, to drive them home, and with Marguerite’s help to doctor the ones hurt in the stampede and fix the broken slats on the pen. It was late by the time all this was done, and Donald sat up far into the night, by a lamp turned low so as not to keep Marguerite and the baby awake, the door and windows open to admit whatever breath of air there was in the summer night, to finish his notes for tomorrow’s sermon.

When he took the pulpit in the morning, his eyes weary and his hands scraped and bruised, he had perhaps never before been so tempted to preach a “topical” sermon bitterly denouncing such sins as obstinacy, anger, and violent dealing. But he did not. He had been preaching through the seventeenth chapter of the gospel of John, and he continued on with it today, in a voice occasionally mechanical with weariness but the same commitment he always brought to his work.

The week following, Henry Glenn, goaded to anger by both his son’s rash action and Donald Matheson’s remaining unmoved by it, told his wife that he forbid her going to church on Sunday.

It was only her attendance that had made Matheson hold out this long, he told her. She was undermining his authority by continuing to patronize the church of a man at odds with her husband, and as long as she kept it up Matheson would be emboldened to keep up his resistance. She was not to show her face in that church again.

But here he had crossed a line. In the face of her husband’s orders, in the face of his anger, Almira Glenn stood firm. She had been a loyal and patient wife in spite of the gulf that lay between them, but she could not obey him in this, and she held up her head and went—alone, since Glenn had forbidden his daughters to go and neither dared disobey him. Rumors had spread in Buffalo Flats, since the Glenn cowboys were very well aware of everything that was going on, but Almira Glenn sat quiet and poised and alone in her usual place and gave all her attention to the service, and asked sympathy of no one—and not even tender-hearted Marguerite Matheson dared to offer it.

When she returned home the storm broke again. Henry Glenn was no brute, despite his tyranny; it was not in his code to ever lay a violent hand on a woman; but in his anger at her defiance he was roused to say such bitter things as he had never said to his wife before—in the presence of their children, and in the hearing of the hired men. Before the next Sunday he turned both harness teams out on the range and gave strict orders to all the cowboys that they were not to bring in or harness a team for Mrs. Glenn if she asked, and threatened to confine his daughters to the house if they attempted it.

On Sunday morning, for the first time since the beginning of Donald Matheson’s ministry the buggy from the Glenn ranch was not in the churchyard. But as the congregation were filing into the schoolhouse, Terry Glenn rode into the yard on horseback, dismounted and tied his horse at the hitching-rail, and went inside and removed his hat and took a seat near the back, his face pale and set like flint. He did not join in the singing, and seemed almost resentful of being there at all, but he stayed through the service with an attitude of dogged resolve.

When the service was over, Donald Matheson, after shaking hands with a few people around the church door, crossed the yard to where Terry Glenn stood by his horse. Terry met his eye squarely as he approached, and Donald sensed that today the thundercloud of anger on his brow was not meant for him.

“I hate sheep,” said Terry bluntly. “I haven’t changed my mind about that. But I can respect you and I can’t respect my father. Not today. That’s why I’m here.”

Donald could not pretend to misunderstand him, nor did he find it necessary to comment. “I’m glad you came, for whatever reason,” he said, and held out his hand. Terry shook it, and their grip was firm and equal.

No one from the Glenn ranch ever said what happened there between that Sunday and the next. But on the next Sunday morning Terry Glenn was again the only member of his family in church. And when Donald Matheson got up and looked out over his congregation, he saw something else which he felt sure even Terry did not know: a handful of cowboys among the men in the standing-room that was now often filled at the back—Tom Mullen, Bat King and three or four others from the Glenn ranch, looking a little awkward and creasing their hats in their hands, but quiet and well-behaved throughout. It seemed unlikely that curiosity or conviction had finally got the better of them—he guessed that, like Terry’s, their presence was a gesture, signaling that they too felt Henry Glenn had gone too far.

Unbidden the fragments of a verse rose in his mind: “Notwithstanding, every way, whether in pretence or in truth, Christ is preached; and I therein do rejoice…” Strange things had brought some of the people here across the threshold of the little schoolhouse-church—not the things he would have chosen to bring them, but they had come, and it was for him to offer them the one thing he had to give.

It was during his closing prayer that he happened to lift his eyes for just an instant and look across the congregation again, and saw that Terry Glenn’s head was down, his bowed shoulders shaking with noiseless sobs he was struggling to restrain. What word or phrase somewhere in sermon or prayer had touched a chord, had at last broken down that angry resistance, Donald never knew—nor could he stop to marvel at it now; but instinctively he did the only thing he could for him and went on praying a few minutes longer than usual, giving him time to master his emotions before the congregation repeated the final “Amen” and opened its collective eyes.

He did not see Terry again afterwards, but in the churchyard he shook hands all around with half a dozen cowboys who might hate sheep, but could respect a man.

Two days later Henry Glenn came out again to the Matheson homestead. His bearing as he tied his horse and approached the house was not that of a man acting in anger; he had the haggard, harshly lined face of one carrying a heavy burden.

Donald was not at the house, so it was Marguerite who admitted him, asked him to sit down and offered him refreshment which he declined with a brief shake of the head, and then went to find her husband. When she had gone Glenn got up and walked the room, too preoccupied to notice little Donald making friendly faces at him around the back of the rocking-chair in the corner.

When Donald came in with Marguerite, Glenn swung about to face him and, dispensing with even his usual civilities, went straight to the point.

“I want to know what you’ve done to my son,” he said. “I’m not going to make any pretense with you. I don’t know what happened that night he was here; he wouldn’t tell me. Whatever it was, I’ll be responsible. What is it you want?”

Donald and Marguerite exchanged a baffled, slightly amazed glance before Donald’s answer. “I—beg your pardon?”

“I’m not a fool,” said Henry Glenn, his voice tight. “I can tell from the way he’s been acting. What did he do? I’ll pay whatever damages, I’ll send my family to church if that’s what you want out of it, but whatever hold it is you’ve got over him, let him alone.”

Donald Matheson stared speechlessly at him for a few seconds, then turned partly away and passed a hand over his mouth as if trying to hide his reaction. He looked at Glenn, opened his mouth to speak, then wavered and broke down into uncontrollable laughter. He leaned both hands on the table, trying to recover himself. Marguerite, very bright-eyed, somehow managed to keep her countenance, while Henry Glenn did not seem to know whether to be offended or baffled, and little Donald put his thumb in his mouth and giggled in delight.

“I’m sorry,” said Donald chokingly at last. “I’m sorry, Mr. Glenn. I didn’t mean to…well. I—I’ve seen a good deal even in my few short years in the ministry, but this is the first time I’ve ever seen the workings of the gospel mistaken for blackmail.”

Glenn’s face was hard with suspicion. Donald straightened up and managed to wipe the last traces of laughter from his face, and faced his neighbor. “I don’t have any hold over your son, Mr. Glenn. Certainly not in the way you think. Whatever happened that night he was here, there’s no hard feelings, at least on my side.”

“Then what’s the matter with him?” demanded Glenn. “The way he’s behaving isn’t natural. What is it?”

Donald did not answer at once. What would Glenn say if he told him he did not know, but could only suspect as yet the deeper changes that might be working in the boy’s heart? “Why don’t you ask your son, Mr. Glenn?”

From a flicker of expression that crossed the older man’s face, he knew his guess had been right: the real trouble lay in that Henry Glenn had discovered the difficulty in doing that, after twenty-two years with the son he believed he knew so well.

Glenn turned and walked over to the window and stood there for a minute, fingering the crown of the hat in his hands. He looked abruptly at the young minister. “I don’t appreciate you turning my family against me, Matheson.”

“I didn’t turn them against you,” said Donald. “If it had been nothing to do with me, if you had come to some other crossroads where they couldn’t in good conscience follow you, would you have acted any differently?”

There was silence for a moment, as Glenn stood looking out the window.

“I’m not proud of the man I’ve been these last few weeks,” he said. He pulled his gaze from the horizon and turned around. “You’ve withstood me, Matheson, in a fight I couldn’t win without resorting to lawlessness that I didn’t want to touch again. I’d fight you still if I could do it fairly, and I won’t say I’ll never try. But I’ve been unjust to my wife and unfair to my children, and that’s another matter.”

He added stiffly, as if it was an effort, “It seems I’ve tried to involve you in that, and for that I apologize.”

Donald said swiftly, “I accept that, and thank you. But if you can bear my speaking as plainly as you do, Mr. Glenn, I don’t think I’m the person most in need of an apology.”

“I’m aware of that,” said Glenn a bit curtly.

He moved to go. But on the threshold he stopped and shook hands with Donald Matheson, who along with his wife had accompanied him to the door. “I can’t say I appreciate you as an adversary, Matheson, but I appreciate the forbearance you’ve shown as a neighbor.”

“If we can be good neighbors and good adversaries at the same time, Mr. Glenn, I think that’s better than what we have been,” said Donald.

And it was Marguerite, even more daring than her husband, who said as Henry Glenn turned to go down the steps, “Perhaps we’ll see you on Sunday, Mr. Glenn?”

Donald gave her a wide-eyed look, equal parts amazement and admiration. Henry Glenn, at the foot of the steps, turned and eyed the young couple on the doorstep, his expression seeming to testify to a mix of feelings which might have been truculence and reluctant respect.

“You might,” he said.