The ordinary man looking at a mountain is like an illiterate person confronted with a Greek manuscript.

– Aleister Crowley

E dward has been a fine companion as I dictated Hag II to him. He knew it was never going to be a will-he-get-the-girl? affair. It was always more than that. This is clearing the name of a Pimpernel, while having the impossible conflict of fighting a perpetual scrap against evil, never able to wriggle free to pursue my own calm. But I know my life has been my own True Will. This always mattered more than the hundreds of love stories and thousands of afternoon entanglements.

Edward asks me, purposefully and volubly, if I am truly ready. I must not delay any more.

My son takes two phalanges of my corpulent left paw and tugs me along. I defer to his encouragement. My steps are light and elevated. I seem to float. I have felt this unblemished ecstasy before in far less angelic, far more tarnished company.

I speak as I move towards my doom.

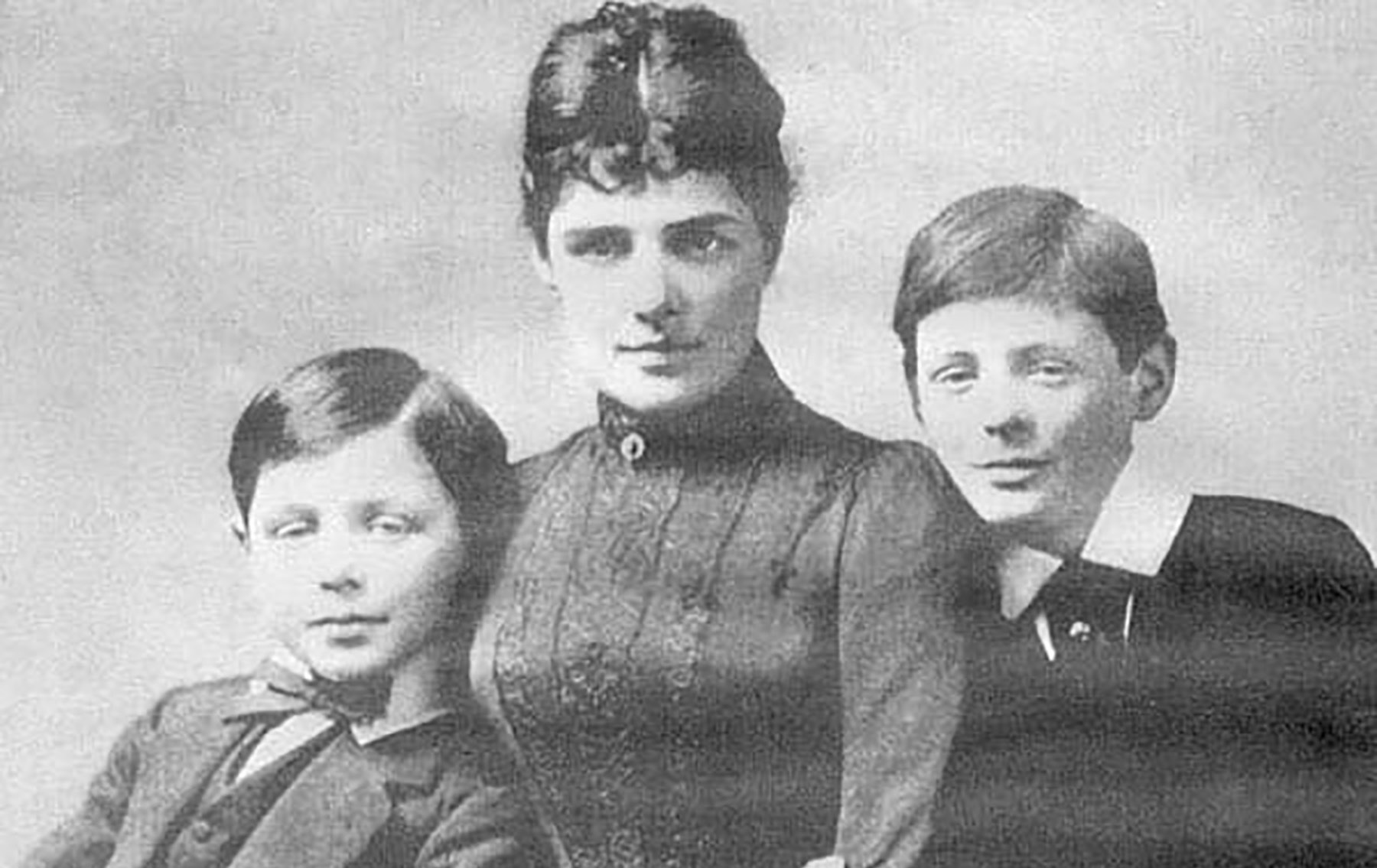

After a lengthy embrace with Orr, which might have appeared minutely comically given his huge frame, we turned to the others. I still referred (quite fondly) to Edward (now almost thirty) and Violet (in her late teens) as ‘Children’ and Zealand as ‘Dearest Papa’, but in the tone of my calling Leah, ‘Monster’ or Frog, ‘Frog’.

‘Children, Dearest Papa. My dear old collaborator, Orr. Orr, my children and friend.’

For us, the pleasantries were tinged with a euphoric relief and exhaustion from the journey, while Orr exhibited the boyish excitement that those golden midges had shown us as we had crossed the threshold in to the grounds of that Sicilian abbey many years before.

We turned and began to walk towards the outer reaches of the citadel, of which we enjoyed a full panoramic view. I thought of that sage old bull’s advice to the aroused young bull on the hillside, and I chuckled at volume. Violet nudged me in the ribs, for I sense she knew my precise thought.

Orr now seemed to truly revel in the role of welcomer and tour guide as we walked on. He threw his arms wide to announce the work of art and majesty before us. My initial inspiration was admittedly a mixed one, for Shangri-La appeared to speak of the sadness of man that such an oasis was required, but far, far more of the quite stirring determination of the hundreds and thousands who had brought the wood, the metals, the tools, the treasures, the books and the spirit of adoration up here. It was a large plateau that spread out before us, perhaps ten miles by five. Were it to be any broader or longer, it seemed that it would be unlikely to benefit from its sheltering high mountain walls. It started with this measured perfection and this good fortune of nature, and then seemed to have that same fine fluke permeate every aspect. The results were the blessings of warmth, wind, fertility and calm onto each square foot of the place, as well as, according to Orr and everything I had read, each simultaneous second on every perfect pathway, in each chamber, on each lea or pasture and in every temple. In short, there was no hiding from bliss and serenity, the silent rapture and the beauty.

Orr’s enthusiasm in showing us all around on that day and the days that followed, introducing us to grinning kids and wise old types, barely masked the thrill he seemed to exude at knowing we would be there for a long time.

He had been alerted to our arrival by a dropped consignment from the Royal Air Force, though such sorties remained rare and reasonably perilous in those early days. Orr carried an air of authority, comported himself so that others certainly seemed aware of his vast presence. The children’s joyous pitch was lowered, almost to a hush, when they ran past us or we strolled through their outdoor classrooms. He seemed to be aware that I was noticing this deference in all we encountered.

‘You all must know of the character, Chang, from the book.127 I suppose I am his equivalent. So much of what Hilton wrote is quite accurate.’

‘It suits you well, my friend,’ I said, as we marched on along cobbled paths between tulip trees, weeping willows, trickling brooks and cultivated and encouraged weeds. We have much to catch up on. But, crikey, we now have plenty of time to do it.’

‘Yes, Aleister. We do,’ and he threw a lanky arm around my shoulder and yanked me close.

‘And the High Lama?’ asked Zealand.

Orr stopped and turned to look down benevolently and curiously at the old man. He then shifted his gaze down to me, nestled between his armpit and bicep. Each comfortable regard lasted perhaps ten seconds. He then turned back to looking at Zealand, and a soft, guttural chortle left his throat as if he had seen the future and everything was going to be fucking marvellous.

As we continued at a comfortable stroll, I was aware that we were not meandering, but instead heading in a very measured but quite determined straight line. I knew he was taking me, first and foremost, to my Scarlet Women.

We first heard their giggling through the trees, Then, as we were spewed out into four-foot daisies and half-a-dozen whoring sparrows of a voyeuristic bent enjoying a fine day, I found them on a warm meadow of soft gradient. Leah’s head was on La Gitana’s thigh. They were still young.

It was only when I was twenty feet away from them that I realised the others had withdrawn, leaving me to take the last few steps alone to my destiny. Never had solitude felt so bloody welcome.

My loves. My darlings. I am home.

And so, this old Beast, this Sir Percy Blakeney, would (sort of) now zip up his flies and take his berth in a mountain paradise, a halfway house to the heavens, free from the ravages of a mean world. My only responsibility was to enjoy my family and friends, old and new, and meditate myself towards the Godhead. I thrilled at the thought of my hours at the typewriter or dictating to my Thelemic children or pals from a fat hammock.

When one had first acclimatised there, one had adjusted to the elevated nature of the oasis. The air was thin, but as we were protected on all sides by mountains and ridges, the fair weather was almost perpetual. We were protected from winds, while receiving an adequate and well-measured rainfall. We were in an unceasingly cushioned springtime that reminded one of perfect boyhood days and also provided the finest grapes for excellent wine. The brain took a day or two to marry this most clement climate with the strong winds we had faced on those narrow ledges by thousand-foot ice-drops. Soon after having arrived there, it was quite easy to lose the concept that we were surrounded by precipitous danger. We were constantly at the gentle core of the most vicious maelstrom, but all we felt was the calm. The brain can play the most marvellous and welcome tricks, this much I had always known.

As with telling of Rasputin, Churchill, Adolf and me, it was always tough not to drift over into cliché when observing my new home. The fine Goan incense was never too strong or overpowering, the fat candles in the temples never seemed to drip wax or shrink, the white doves were persistently fluttering nearby, and the large stone Buddhas never felt a drop of their bird shit. The outdoor schoolrooms by splashing fountains aided learning of the keenest young minds behind grinning chops. After school, the scamps ran through the perennial blossoms of springtime to the hot springs and waterfalls. The knees below short trouser hems were muddied but never bloodied. The boys and girls knew no word for doctor, misery or servant.

The rare treasures from the modern world, which had been delivered by porters from below, were tokens of gratitude for the loving types the mountain loft had given to the towns and cities around there. Gold was in the earth, but carried no value.

Leah had healed quite magnificently, and we now spent our days enmeshed with La Gitana. It seemed only right.

‘We put it down to diet, climate, mountain water and, more than anything, the absence of struggle,’ Monster told me, as the three of us lit a potent reefer one dusk, still entwined.

‘Here we see the indirect suicide of our ways of life down there,’ said La Gitana.

Leah spoke the words of the much-vaunted Father Perot. It seemed that each inhabitant knew these words as we would know the national anthem or the Lord’s Prayer.

I saw all the nations strengthening, not in wisdom but in the vulgar passion to destroy and exalting in the techniques of murder and rage. Look at the world today, is there anything more pitiful? What madness there is, and what blindness. A scurrying mass of bewildered humanity, crashing headlong against each other, propelled by an orgy of greed and brutality. The time must come, when this orgy will spend itself, when brutality and the lust for power must perish by its own sword. When that day comes the world must begin to look for a new life and it is our hope that they will find it here, with their books and their music and the way of life based on one simple rule. BE KIND. When that day comes, it is our hope that the brotherly love of Shangri-La shall spread throughout the world. Yes, my son, when the strong have devoured each other that pure and Christian ethic will finally be fulfilled and the Meek shall inherit the Earth.

My days and the passing of time were as clichéd as the setting. But the oft-maligned cliché is sometimes just a cliché for a very good reason. It is true.

I meditated, read, wrote, taught the unblemishable children, schooled them in languages, science and art and then, with Orr’s assistance, blindfolded chess. I lectured them and took questions on the scriptures of all stripes, and lauded nature to them, not that they needed this; I just could not help myself. I walked barefoot, ate minimally from the crops of our fields, sat in shaded meadows, where I received daily visits from midges and sparrows. You know of my goats, and the presence of several old chums, with whom I would spend auspicious and shining hours, days and seasons. I was ecstatic in the knowledge that I had deserved my dotage and was able to extend it to demigod-like proportions. My stone chambers were sparse, but for the further cliché of legions of books and an unused pair of hand-woven sandals beneath a simple writing bureau of feather, sheet and ink. There were no clothes there, so the hessian sack on my back and to my knees was my sole robe.

Violet was twitchy, of course. But she was also youthful and sprightly and determined enough to visit me for six months of every year, as she challenged herself with the true familial spirit of bloody mindedness to suffer the cleanliness and the noble holiness of my lair. She was mastering that sensational bipolarity of, on the one hand, self-deprivation of one’s own desires in Shangri-La (see Sir Percy Blakeney), followed by a feast of depravity down below (see Aleister Crowley, The Great Beast, 666, Perdurabo). My, how she adored Edward and Zealand, for they were quite the contrast to my marvellous poisoned spawn of delicious malintent, my Violet.

And those fine men and best friends – one from the obverse seed of the gentle and high-born Roberta – quite marvelled at Violet’s persistent wickedness. I saw them watch her with the intrigue afforded a controlled scientific experiment or a transgressive chimp. Her impishness found favour, of course, even with or without the umbra of her father’s vastness. I wondered whether in isolation, Violet would have been brawling even in Shangri-La, but I afforded her broad latitude to err with her measured crassness and her ignoble tendency to blaspheme, curse and eye the locals with a pansexual’s glare. Forgiveness is a fine state.

But something quietly nagged at me. For decades, I had been missing my TRUE dreams by inches. I wondered now why, when in utter bliss, would this feeling persist?

Winston, like I, had resurrected himself. With typical verve and ballsiness, he had won a general election and served another four-year term128 as prime minister of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

When he finally left office, he was left scratching himself in that big house by Hyde Park Corner, bored and in need of a pastime. He wrote to me, at length. The letter took two months to reach Shangri-La. Like that castaway with his single message from a lone bottle, I reread these words many times, laughing, twitching with excitement and verve. I could imagine his face as he penned it, determined and wicked.

Should we have some fun, Beast? You and I put our aged minds to mischief? Recruit some like-minded renegades? This idea of mine, which I am about to outline, can be a fine vessel for Thelema, you know. Prudence is sitting opposite me as I scribble, and is purring at the prospect of it all. They both send their adoration, of course.

And so at my prompting, he and I from very different worlds of London and Shangri-La, on the fifteenth day – a Monday – of April 1957, launched the London Review of Passion, and therein was the editor’s playful and devilish column called ‘Six Fingers & Fat Thumbs’. For us, this general monkey business would be a new époque of perhaps sedentary, but yet quite rogue behaviour. The Sherpas in-and-out of Shangri-La now left and arrived (with our communiqués) every three weeks, instead of every two years. These intrepid couriers and then the telegram (or vice versa) were our only link between HQ and this Himalayan bureau chief.

The LRP’s arrival was greeted with intrigue, for no one in England (well, no one who was not a keen Thelemite) knew the identity of any of the owners, publishers, editor or scribes. This spectre was elusive and like smoke to hold. In the spirit of Count Svareff prodding Manhattan in the Great War, it really got the buggers talking. Imagine if they only knew it was an ex-prime minister and a dead Satanist – and a small tight unit of wordy Thelemites, who dined with Winston twice weekly – writing to them fortnightly. I worked on more philosophical and less time-sensitive articles. Winston read all of the papers daily, had a busy satellite office in that library in his Hyde Park Corner mansion, and was the lightning rod and nerve centre for the operation. He provided me briefs for editorials that might be of interest six months later. We had so much fun, and I felt, as I wrote in my solitude, as if I was still seeing him every day.

THE NIGHT I SAW RASPUTIN FIGHT A BEAR (15 April 1957)

ASTRAL PROJECTION – A GUIDE FOR CHILDREN (24 June 1957)

W. B. YEATS – NEW RUMOURS OF RAMPANT PLAGIARISM & LOW-LEVEL BESTIALITY (9 December 1957)

REDEFINING OUR WORLD (A.K.A. ALL THE -ISMS ARE NOW -WASMS) (20 January 1958)

*

In London, Winston set up and maintained a façade of mystery around the whole publication. Submissions were always delivered by hand to the magazine’s perpetually empty head office (apart from one spotty fourteen-year-old messenger lad on five shillings) in Berners Street, W1 and generally by 3 p.m. on Wednesday afternoons, close to the paper’s deadline. Of course, this was not necessary as they were sending them to themselves, but Winston reckoned that the more they could fuck with the minds of any competitors or nosy-types, the better. It worked, as column inches by the score were dedicated to us in The Times, the Manchester Guardian, the Telegraph and the Evening Standard.

The submitted articles were always typed on solid-stock and embossed paper. The Crowleyian and Churchillian missives often contained pencilled or green-inked amendments and margin notes, as well as red wine, cigarette burns and what the writers knew to be stains of the finest goulash outside of the Magyar kingdom,129 while rivalling many from within. The battered but precious contents came in a fine veneer, a vellum envelope, meticulous calligraphy and a lilac wax stamp on the reverse. The seal was of a Hungarian cossack, that organisation of illiberal violence so well suited to and moulded by their wholly vicious terrain. In those days, they were always signed with a single lilac T.

The editor and the publisher claimed in their copy that they did not know the identity of the supplier(s) of the editorials. The reader did not know the identity of all three: journalist, editor, publisher.

COCAINE – A GUIDE FOR PROVINCIALS (18 August 1958)

IS BENITO MUSSOLINI STILL ALIVE? – EXCLUSIVE & HARROWING PICTURES (12 January 1959)

HIGH HITLER AND THE GAME HERMAPHRODITE (9 March 1959)

All the publisher would reveal was that he/she did exactly as he/she was asked by the contributors, to deposit a cheque each week into the account of the Kensington Butterfly Zoo. The owners of the place had been pressed in each issue by the LRP to increase the size of its enclosures. Now they had the funds and would soon, they promised, possess the largest butterfly enclosure in the Western world. At that precise time, this had been the funniest thing that Sir Winston and I, just two of the new team of senior editors, had ever heard.

Yes, just two, because by the time the London Review of Passion celebrated its third birthday on April the fifteenth, 1960, in private of course and at The Gay Hussar, that number had increased. Three new executives were penning politically precise, rebellious-of-spirit and bawdy, jocular pieces in each edition. They were three pre-eminent names in the world of cinema. I really ought to thank that fine lad, Dibdin for his urgings and promptings in having delivered to Six Fingers, Marlene Dietrich, Alfred Hitchcock and Orson Welles. I began to think, for the first time, that I might even like to come down from my lair to join this renegade mob. But life up in Shangri-La was such a delight. Such a delight. The grass was literally greener up there.

And it stayed that way for over four years, during which from those leas of ragweed and grass, and the pastures of sunflowers and billy goats, I regularly told a thrumming Violet and the nodding boys of our new revolutionary front, catapulted into the consciousness by the columns of ‘Six Fingers & Fat Thumbs’. Our fight, aided by three cineastes of true stature, was not, I always insisted, unleashed against the Soviets, but, through the brave types we had recruited in Hollywood, Greek Street, a resurgent UFA Film in Berlin, and Cinecittà Studios in Rome, we now were fighting instead the meanness of McCarthyism and Cold War paranoia, which was the reaction to our own meddling of seven decades earlier. This was a quiet and dignified revolution of the mind through the movies.

And I would have stayed there forever, but in the May of 1964, Violet touched my hand as I meditated, and kissed me tenderly on the forehead. I knew something was wrong. The newspaper in her hand had been dropped by the RAF, and had been intended for me. When I saw the formation of a tear in my unshakeable girl’s eye, I knew it was as serious as it could be.

I read the headline.

CHURCHILL ON DEATHBED

At the age of eighty-nine but with the rejuvenated appearance of a fifty-year-old, heavily disguised as a lumbering and aristocratic Norseman of unquestionably sapphire-blooded lineage, and urged on by the undiminishable love of a challenge and of a mountainside, Violet and I resolved to return to London and to England to say farewell to my great friend.

The journey home was easy. We rolled down that mountain like gambolling goats, Chittagong welcomed us and spewed us out to sea. Winds were forgiving. There was no storm in which to sully myself, naked on a mast and in front of my daughter. Instead, I wrote by day and night for the magazine. The soft ocean air on one’s face was so conducive to producing a vast output. We were in Deptford in less than two weeks, and I carried an armful of typed-up articles and features.

The diatribes in the LRP were often commentaries on many aspects of London life, but, given the curriculum vitae of the contributors, ‘Six Fingers & Fat Thumbs’, now a column of length that often seemed to be ingesting the magazine, soon revelled and relished in the cinematic and artistic review. When I finally met them all, the first impression I had of their literary intent was that the three of them seemed to enjoy discussing paedophobia, whenever feasible and appropriate. Stuff like The Bad Seed and The Lord of the Flies. They, like me, knew that all of life’s wonders and horrors began in childhood.

To the average reader, the writing style seemed to change, as if the penman were schizophrenic or it were the work of criticism by committee. Both were perhaps correct as Orson and Alfred shared the joy of a direct and pedestalled platform to the citadel. And, of course, they were always polite enough to never change their bawdy ribaldry when Marlene breached their smoky and degenerate lair, bringing her unmatchable thoughts and unrivallable cassoulette to their tables at The Gay Hussar.

Our editorial, I liked to think, carried real merit to a readership that appreciated sensation; not in the cheap and tawdry and gratuitous sense of the word. Sensationalism was supremely unwelcome, for we were measured and disciplined artists. This was not to say that we were, by any stretch, conservative. I would hope this is clear by now. We were unafraid of shocking, we revelled in it, lived for it, but never without foundation and a truly deserving target. We meant sensation in the truest form of the word – whether it was the needle-like Sicilian raindrops of a summer storm on the face, the spiciest goulash at the Hussar, any part or action of that high priestess, that Marlene woman, or sitting on the Hillary Step with a young Sherpa, recently satisfied and smoking on a vast pipe of ecstatic hashish.

Hitch and I decided to expand on an old Mussolini article. We called it:

MUSSOLINI FROM BEYOND THE DUNGEON OR GRAVE

The concept was a simple one. Il Duce was still alive, being drip-fed utter malice and kept hostage somewhere in Europe by those whom he had slighted. His captors had allowed him a nib and some fine stationery once a week to beg for his tormented life and to describe his quite subhuman conditions as comfort to all those sisters, wives, daughters, sons, brothers and mothers who missed their brave Giuseppe or Benvenuto. Just what would the old Fat Head have to say to his mother, to Italy and to God? Well, the good folk of London town found out on a fortnightly basis.

We exposed oppressive governments, juntas, prime ministers and presidents, as well as pederasts and frauds of any kind. We shone a light on reactionary and turgid freemasonry, that rancid old pastime and practice from which we had syphoned off the selfish cuntery. Thelema had catapulted the finer, remaining aspects of it to marvelled heights of kindness, self-fulfilment, protest and transgression. We did all this over goulash in the Hussar, and in our own beds, from Hyde Park Corner to Dulwich, over buttered crumpets with Marmite and gut-warming Ovaltine.

Deep down, I knew that what we were doing was never going to ignite a revolution. It might provide fodder for the rebellious of spirit, but it was in those soggy Soho days that something started to take hold. It was a feeling that this might lead to something greater. Was this Samson yet again to test his biceps and take on the pillars of the temple?

And despite the sadness around Winston’s pending death, it was otherwise a marvellous and celebratory time that year with those degenerates in Greek Street, and I know our continued plotting brought them great joy between the productions of their treasured movies.

They were such mauve days, such fun and treasured days, for I knew they would end as soon as Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, KG OM CH TD PCc DL FRS RA passed away, and that day was surely coming. It was quite true that there was nothing like a funeral to concentrate the mind. Even more so with a best chum dying in a hospital bed, but my time in Shangri-La allowed for an even greater appreciation of time, down on the plane of mortals. It only went to underline Winston’s true stature, with his unequivocal greatness and his highly evolved state, that he did not seek to prolong his life in the Himalayas.

And so, we treasured each day of that sparkling year, as I took my darling Violet on a tour of the seaside piers of England, to Cambridge, and back to the place of her conception and well-stewed birth by Loch Ness and my darling Boleskine. We watched cricket at Arundel, Scarborough and The Oval. Her aching princess, now sister to the Queen of England, would sometimes abruptly arrive on a country lane or in a first-class carriage to Eastbourne without announcement or warning. And I knew to leave them alone, as any gent or father would.

As keen cineastes gladly stuck in the mountain, Zealand and Edward were keen to hear by tardy return courier of how our days and nights were spent with these stars.

I wrote to them on August the fourth, 1964. Here is a sliver of my dribble and gossip.

You know that I have been so inspired by my friend, Orson. He might be the cleverest man I have ever met. And having him on our side now shall thrust us forward, but I am too long in the tooth and have too much foresight to believe that cinema on its own can bring the revolution of which I dream.

I think we ought to seek to morph, to swell and to evolve from a basic and personal mantra of drugs, sex, freedom and personal fulfilment into a mouthpiece of the Revolution that would urge the peoples of the world to rebel.

And for this, I would require more than pamphlets, books, cumbersome newspapers and mountainside orgies in front of intrigued and nodding wildlife. It would all require even more than celluloid. And despite this suitably motivated and intellectually capable team of acolytes and mischief-makers, this is all just a preparation. But it must happen soon, for I cannot last forever down here in this gloried grime. I will have to come back, and then the chance might be shot.

I SHALL have my world of peace and love! I SHALL! I have not come this far, and foregone a comfortable life of libraries, cricket pavilions, golden retrievers, naps after breakfast, larking bairns, summers at Lord’s, eagerly fellatic weekend lads and top-notch wives for it all to end without the greatest glory of a truly transcendent planet Earth. What sort of fucking god would I be?

Lord, I love and miss you both, and all there in our treasured loft.

A month later, my beloved son quite admirably brushed off my bluster in an adorably brief letter.

Yes, Papa. But tell us of Orson? And of course, Marlene? The mothers and aunts in Halle so adored her.

On October the twenty-fifth, 1964, I indulged the nosy sods.

When I first met him, Orson had already revolutionised theatre, pulled the world’s most marvellous and heralded radio stunt and completely baffled Senator McCarthy. Welles’s whole life to date has been the most magnificent virtuoso performance. Not to mention masterpiece. He is a quite the actor too.

Citizen Kane is, after all in its simplest form, just a series of greys, but what intuitive divinity. No wonder Hayworth, Garland, Dietrich and vast squadrons of marvels have salivated over the joyously soaked hound. And he has had to put up with some of the most unlamentable and particularly uneducated louts Hollywood has ever mustered, and that is some feat. He is a colossus, who possesses, quite reluctantly, a philistine’s doubt over philosophy. I once told him, ‘You put your finger on a basic failing of all lazy people: they have to work too hard or they won’t do anything at all. You know? Once I stretch out in a hammock, you’ll never hear from me again, you know, because I like it that way.’

He has since adopted it, with my permission of course, and it seems equally applicable to us both, at the time and with hindsight. I wouldn’t have it any other way. He neither, I am sure. Anyway, Hollywood is so fond of quoting itself. It is, after all, a mirage of frauds speaking other people’s lines against false scenery with fake lighting, unless you do it all yourself like Welles does. Hollywood deals in derivatives. And death.

There is no coincidence that four of his great works have ended up with his execution in a sewer, with slaughter in a labyrinthine, mirrored funhouse, murder in a no man’s land border town river and a great man fading away with secrets never to be told. He is a multitude of a man, I exalt him. He might be the most exaltable man of this pivotal century, and those studio heads, especially that primitive counterfeit scoundrel and fakery-meister Harry Cohn, simply cannot be excused for their filthy, bogus behaviour. The ever-generous Orson prefers to concentrate on those he admires: Cooper, Cagney and Garbo. General Marshall and Churchill.

I am now relishing the nostalgia. I do not move my arse as I write, nor do I give any clue that I am not luxuriating in my fondness for my friends.

We do not agree on everything. Bullfighting is a passion of his. Welles, not Churchill, you understand. (I just laughed out loud, son.)

But he is changing his mind eventually. The sign of a truly great man is one who evolves, you see. Yes, there’s stubbornness and self-belief, but that can only ever get a man so far. To really elevate oneself and crush those supernatural constraints, agility of spirit and of mind and, sadly, of foot is so very vital. He tells me that bullfighting is indefensible but irresistible. I am not averse to or unfamiliar with such lures; I once had published The Diary of a Drug Fiend, for heaven’s sake. And so, I have been very well acquainted with such ritualistic behaviour as that of the toreador, but then Orson hates that it has all become folkloric. These are his words, not mine. I guess he looks up to that matador Belmonte the way I look up to him. He has slaughtered bulls, but, weirdly, he also loves them, like I adore those perverse young goats of mine.

As for Marlene, well, she and I have become ace chums, as we often stay up all night here in the Hussar, and practise our German and smoke strong hashish. The best nights and mornings are when Orson and Hitch are here too.

Just this morning we were all so elegantly high on cocaine that we each spoke of that which excited us most, with almost little relevance to what the others were saying. There were some egos on show, boosted further by the powder, but we remained the soundest of chums. Marlene spoke of her lighting, I spoke of revolution, Orson spoke of bullying and scaring Senator McCarthy and Hitch spouted on about murder. Of course.

As a joyous and charged dawn of light drizzle broke over Soho (Violet and Margaret had slipped away, unable to keep their mitts off each other at the bar over champagne cocktails, like strutting and moody kangaroos) and three faithful Magyar waiters kept us all topped up, comfortable and supremely welcome, I could have kissed Marlene, as she leaned forward on those elbows in her girlish thigh-high cotton, lemon-yellow frock, eyeing me closely, and breathed warm and womanly rafts, flavoured by wine and tinged by desirous hormones. ‘You know, Aleister. I am able to know if my lighting needs an extra ten degrees of tilt, while I am under it. I know more than any director who has directed me, and that includes Josef.’130

‘This is a skill,’ I admitted to her.

I looked at Orson, with his handsome widow’s peak and bold eyes of serenity masking a darting brilliance.

I should have known better, for Orson, after a brief pause and fingering the loosened and drooping white bow tie around his starched collar, could simply not help himself.

‘Yes, my dear. But I am able to pull off a far trickier feat. I know when I have hit my mark and whether I am … in FOCUS!’

The head-butting of such heavyweights has been our joy for these months, as we cannot get enough of each other, all aided by hillocks of vigorous and full-bodied cocaine that allows for our hours to become days. Your father is unlikely to change now, son.

‘You know that I shall have my revenge for that, don’t you, my dear,’ she said to Orson with a chilling camaraderie. This was clear to anyone who knew her. Only my Marlene, the finest of Valkyries and so unreasonably perfect as Mata Hari, could have got away with seductively and audaciously adjusting her stockings before the firing squad as she did in Dishonored, sending grown men and women – aroused, hollow, remorseful and envious – to bed across the world, nation by nation, crying into their pillows. What a girl she remains.

Her casting as the clairvoyant in Orson’s Touch of Evil had been her own inspired off-the-cuff idea, as was being Orson’s lover, for she had executed the real-life act for the first time just minutes before the rushes on day one of shooting. Seeing into the future is easy for such women, for they always get precisely what they want.

Her line to him, ‘You should lay off those candy bars. You’re a mess, honey,’ was remarkable ad-libbing that even silenced Welles. It remains four seconds of utter genius (almost matched by Orson’s defeated and quite perfect mumble) and was just a touché in their persistent and fond battling and bating, just as was evident here at dawn today in the Hussar.

Orson nodded, acknowledged his debt, smiled at Marlene, and then, despite many bottles of Pálinka,131 spoke with an intent and measure that even I found impressive. He was in a reflective mood, as he softly crowed.

‘I know what I am doing too,’ he said, his hands quite still despite a monumental intake of powder. ‘You know that I bated that ass, McCarthy, and his thugs so much that they dared not ask me to testify in front of the House Committee. This was probably because I was constantly asking to do just that. They suspected that I might outwit them as I had been doing every day for years and for fun. Well, I clearly already had. I was the only one who was never asked to give evidence. You would have been so proud of this Thelemite, Beast.’

Son, I tingle at the thought. One can never have something like the cinema which impacts on and lectures and moulds and moralises to the population all the time, rolling through the weeks and years and decades, without it being of central interest to bastards like that senator. But it is curious that in response to those nasty malfeasants, more was done for our cause than any one person or event ever could. The mean arseholes galvanised us and mobilised us in the name of those millions of dead boys and girls in Europe, Africa and the Pacific, who fought for the freedom he threatened. I propose a toast in their honour and name.

Freedom. And our Revolution.

I shall see you soon, boys.

Your father and friend,

Beast

I suspected I knew what they would want to know of next. I was right. They asked after that lardy barrow-boy we all knew as Hitch.

The letter was dated January 17th, 1965.

I first met Hitch in the snug of The Crown pub in WC2. He was sitting with a mob of actors, whom he loved more than they would have you believe. I sat at the end of the bar opposite to him, as I heard him say, ‘That has never happened, but Aleister Crowley did appear in my bathwater once.’ The mob roared.

One of his firm, a gawky lad with veiny temples, purple pimples and championly crossed eyes, recognised me beneath my favoured fedora of the age before I removed her. He whispered quite loudly that the Wickedest Man in the World was now over by the whisky gills. Hitch carried on chatting, but allowed his company to take over as he casually doodled on a hefty tablet of heavy stock. I eventually walked over and dropped a scrap of paper onto his sketch. The two images – both shocking in their detailed nature – were absolute facsimiles. I smiled at him, he at me, and we met at my end of the bar within the hour.

The pustulous urchin eyed me with worry. In an attempt to put the boy at ease, I walked back to him later in the evening and announced his star sign to the group.

‘How did you guess?’ he stammered.

‘I didn’t guess, silly lad.’ I said. ‘I knew.’

I suppose my well-intentioned attempt to put him at ease had gone quite awfully wrong.

Hitch, who had been observing with his calm and inimitable countenance, then spoke. One always knew when it was time for Hitch to speak, because of his recently tilted torso, ready to contribute, and the sharp suck on the air in his immediate environs, the pause and then the slow, deliberate monotone that only a Great might deliver. He had a way of saying almost anything and making it seem relevant to the conversation at hand. This, too, is the sign that one is in the company of authorial greatness.

‘You are all adequately informed to know that one has to find murder funny, and execute it with a lushness. It has to be hilarious to me. There’s a fine line between tragedy and comedy. For example, how many times, years ago, have you seen the old-fashioned scene of the man walking towards the open manhole cover. Of course he has to wear a top hat, because that’s dignity, you see. That’s the symbol of dignity. And you watch him and he walks. He is reading a paper. And he’s missed seeing it and he suddenly disappears down the hole. And everyone roars with laughter. But supposing you took a second look and looked down the hole. His head is cut, bleeding. And they send for an ambulance. His wife and weeping children rush to the hospital. Think how ashamed that audience is that they laughed in the first place. And yet they do. Slipping on a banana skin is very painful. So there’s a streak of cruelty among everyone. I call it dipping one’s toe in the cold water of fear.’

And Hitch stopped. His point had been made, as far as he was concerned.

Our home is Soho. It is so marvellously mauve and grey and dank. Finely fetid, she is. The inspirational rains outside are there for us to dance in, when we need a devious and deviant plot gradient to our own immediate lives. Hitch often comes up with arcs, dialogue and directions, after having sat on the kerb, ankles deep in a brown puddle. He then walks back in towards the table by the piano, and heralds himself, in his slow and intoxicating drawl: ‘I am back.’

He is a marvel. After he has announced himself, he walks to the piano with the gusto of a broad man, oblivious to the chairs he knocks over en route. He then sits and plays, though he is, of course, quite awful. It is always a distressing and interminable episode when he approaches that abused device. But boy! He shows the right spirit, such zeal, and that is what counts. I often stroll over the river and pay homage to him at that old fleapit, the Gaumont Rialto, in Waterloo. I will watch four films back to back.

He wants to write a screenplay with your old man, son. Ours, he reckons, is a simple story around two men, foremen at an automobile factory. I must write it, he says. He wants my twisted eye on it. I want us to do the longest dolly shot in cinema history. Longer than Orson’s famous one in Touch of Evil. (By the way, Orson told me that his opening sequence, a single six-minute take, was all shot at night when he was making a different version of the film. His version would not be the dull affair that the studio execs, who clocked off at five, thought they were getting. This is the devious nature of a fine and allied Pimpernel.)

Anyway, the concept of my script with Hitch encapsulates the brilliance of the man, both technically and, through suspense and intrigue, narratively.

The idea is that the take begins with the very first stage of an assembly line, two men walking and talking. Then we gradually see the parts of the car added behind them, and all the while, the camera’s dollying for an age along with the vehicle, and then eventually there’s a completed motor, all built and it is driven off the ramp. One foreman then opens the passenger side door and out falls a dead body.

Just as Hitch explained this denouement to me, our waiter, a Hungarian lad with a face of magnificent roguishness, had come to stand by my shoulder. As I had once with Rasputin in the Urals, by the stinking well at the Abbey in Sicily, and with Edward by Boleskine in the rain, I envisioned the weightiness of what was coming.

I turned and looked him in the eye.

‘Sir, I have a message from Sir Winston. He wishes to see you.’

I rose and began to excuse myself.

‘I am truly sorry if I was unclear, sir,’ the boy said with impressive firmness. ‘He wants to see you ALL.’

A large and luxurious car hummed outside by Hitch’s favoured kerb, as the young Magyar held the door for us. Once we were all inside, he then closed it with sturdy reverence behind us. We set off to the south, left onto Shaftesbury Avenue and then down Charing Cross Road to Trafalgar Square, where the morning fruit sellers were squawking and ogling the exposed legs of office lasses, clipping their way to typewriters and subservience.

Not long now, my girls. I shall free you caged birds, I swear.

Whitehall was clear and free of the usual messy bustle. I stared at Parliament, pondering how my friend had ruled there.

I had presumed we were going to St Thomas’s hospital on the southern banks of the Thames opposite the House of Commons, but our man drove straight past and continued south down towards Kennington Park Road, when I realised where he would be.

The foyer to the old fleapit, where we had spent many magically flecked hours, was as musty as always, as we were ushered in from the quiet side street. Marlene led us in. Of course, she did. Winston knew them all so well, and there he was in his hospital wheelchair three quarters towards the back in the central aisle in front of that tobacco’y screen. The projectionist must have switched off the reel, as the pictures and sound stuttered to a rough halt. We all moved in on him, each offering a lengthy hug of an old friend. He clung to Marlene noticeably longer, while she ditched her Teutonic tendency and clung back with ferocity and without any resort to acting. Winston’s frame had diminished, yet his head was still a weighty bowling ball, able to express simultaneously an obsidian humour, larking boyish mischief and deep potential menace, while gently carrying the spicy and woody whiff of a quite marvellous eau de cologne. We all sat around him.

His voice was slow, deliberate and yet stirringly urgent. Only a Great can pull this off. By God, that old fleapit had never shown such illustrious company on its screen, as sat there that drizzly winter morning.

‘My friends. Thank you for coming. I must keep this short, though it is against every fibre of my being. You all know that. I want you to come close to me one at a time, as I have something to say to each of you in private, though I know you buggers will reveal all to one another. I want each of you to know that he who reveals all later, is, of course, prone to exaggeration. She, less so.’

He chuckled to himself, and coughed uncomfortably for having done so. He spoke to the others for perhaps five minutes each, all with an exchange of love and benediction at the end. He ended each with a voluble ‘Let us not unman each other,’ even to Marlene, and thus, the parting was firm and lacking in all sentimentality. I stepped forward last, as the others moved to the curtains by the ice-cream and cigarette counter.

I moved my face close to his, and I saw eyes bold and lively, but then minutely afraid and tired.

‘Two things, old friend.’

I nodded. He continued.

‘I know I owe you a secret.’

‘Yes, Hühnerbein. Why did he hate you so?’

‘Well, he was an unmitigated arsehole. Of course. That was the foremost reason.’

He managed a chuckle that rattled in his clearly fading chest, and began to wave two pudgy fingers to the east.

‘There were all the stories you have heard from our friends about our mistaken identities, and the times I robbed him of praise or riches or lasses. And my dear Clem, come to that. These are all true. But the summer’s day he began to hate me rather than love me was one at Harrow in ’91. We were both there. We were batting together in the annual Masters versus Boys match. He was given out, when it was I who should have walked, both stuck halfway down the track in no man’s land.’

‘That was enough for him to hate you as he did?’

‘No. He was then buggered by four prefects in the cloisters, thinking they had grabbed me.’

‘Well, that might do it.’

‘But there is more, Aleister.’

Several seconds passed.

‘He was my brother. Well, my half-brother. Mother always despised the poor runt. He was a decent lad as a little one. Maybe that day turned him into the evil twin in the tower. Shortly afterwards, he was shipped off to family in Bavaria. His real mother was some nouveau Munich strumpet. And so, Hühnerbein was never his real name. It was Bertram Churchill. So, now you know.’

I held his girthy left paw. ‘Well, I’ll be damned.’

‘You thought you were the only one with a lifelong secret, didn’t you?’

There was a long pause as we stared at each other and then we exacted our synchronised and theatrical bellow. I saw Marlene, Orson and Hitch turn swiftly in unison to regard our joy from afar.

Winston then waved me back in.

‘There is one last thing. You have a final mission. From me. Not from those fuckers down the road.’

He clearly meant MI-1, as all of his mirth and joy turned to earnestness.

‘Aleister, the price I pay now in having to die is equal to the price you have paid over decades of serving England through your secrecy and the absolutely abysmal treatment you and yours have suffered for it. I did not give myself the luxury of going to Shangri-La, but then again, I was not called a pederast or a traitor or a Satanist for fifty years. I shall tell you something now, and just once. If you wish to save England for me, you must now work against Her. I beg you, I urge and implore you to do this. She is turning a dark corner. This is the tunnel at the end of the light, my friend. What I mean by this is you must now follow those instincts of yours to rebel, for only by doing this shall the England you and I adore be returned to us, though I shall not be here to relish Her. England is becoming governed by dark forces, and they will take us to Soviet horrors.’

He paused for breath, and touched the lapel of his grey-checked day suit, before resting his chilled paw on mine.

‘We were always allies against the Germans and we won, my friend. We bloody won.’

He stopped now, and allowed himself to think about this, it seemed. If he was thinking the same as I, then it was the bizarre clash of the firmest ecstasy in having saved the world from True Evil, while the absolute misery in considering the millions of poor bastards, dead, maimed, orphaned and widowed.

‘But I was a reactionary Englishman, Aleister – nothing more – while you were a revolutionary first and an Englishman second. Sometimes we must keep what we have by giving it all away. Go to Paris, for this is where your rebellion is most likely to spark. It may be time for me to say that yours is NOW the righteous and only way. Please, bring back my England. Those boys and girls who will always remember the nights in the bomb shelters, well, they want something different from their age. This is the unleashing of the most powerful energy we shall EVER have. Youth. I love you, Aleister. Let us not unman each other.’

I knew he had finished, and all I said in return was the same expression of adoration, ‘I love you.’

I withdrew, moved inches higher and put my lips to the frowns of his forehead, which slackened under my manly kiss. And that was that. I turned on him, and walked, as if going for a piss in the intermission.

And so, leaving Marlene, Hitch and Orson in the foyer with a fond embrace and farewell, it was to Paris that Violet and I would go.

24 January 1965

Goodbye, you fucking beauty.

127 Chang was a trusted official of the High Lama in Lost Horizon.

128 From 1951 to 1955.

129 The famous Hungarian restaurant, The Gay Hussar on Greek Street in Soho.

130 Von Sternberg directed her in seven films, most famously the provocatively entitled Blue Angel (1930); the Blonde Venus’s cheekbones were far more memorable than the plots.

131 A strong fruit brandy from the Carpathian Basin.