![]()

IN 1982, A SEVENTEEN-YEAR-OLD SPONGE DIVER EMERGED FROM the wine-dark sea off the coast of southwestern Turkey and told his captain that he had seen a “metal biscuit with ears.” When he drew a picture of it, the captain recognized it as an oxhide copper ingot, which archaeologists from the Institute of Nautical Archaeology at Texas A&M University had asked him to keep an eye out for during their sponge-diving season. He contacted the institute and by the next summer the archaeologists confirmed that it had come from a shipwreck dating to the Late Bronze Age. They had found what is now known as the Uluburun shipwreck.

The ship, which sank around 1300 BCE, is—without exaggeration—one of the most important archaeological discoveries of all time. Shipwrecks always represent a snapshot in time, from the Titanic on back, but it is unusual to find one from so early and so full of cargo. The Uluburun wreck was found stuffed with raw materials, including copper, tin, ivory, and raw glass, as well as finished goods, such as pottery from Cyprus and Canaan, that sheds light on the international trade and relations that took place more than three thousand years ago. It is extremely important as a microcosm of the interconnected world of that time. The fact that it was found in 140–170 feet of water, and that the archaeologists conducted more than twenty thousand dives for a decade without a major accident reported, makes the tale even more unusual.

![]()

The story involves George Bass, the father of underwater archaeology, and Cemal Pulak, who was first Bass’s student and now is his colleague at the Institute for Nautical Archaeology at Texas A&M University. But it begins in 1959, when Bass was a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania. He was trying to decide on a dissertation topic when Rodney Young, the curator of the Mediterranean Section of the Penn Museum, called him into his office. A shipwreck had been found off the coast of Turkey and someone was needed to excavate it. Young thought that Bass would be a good choice.

And he was. Bass went out and conducted the world’s first underwater excavation, on what is now known as the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck. This is why he is referred to as the father of underwater archaeology. The Gelidonya shipwreck lies reasonably close to the Uluburun shipwreck. Of course, Bass didn’t know that at the time. It also dates from almost the same time period, because it sank in about 1200 BCE.

On the Gelidonya wreck, Bass found artifacts that indicated it had been a small ship, and was probably tramping around the Mediterranean—that is, going from port to port, buying and selling goods as it went. It does not appear to have belonged to a wealthy merchant, or a king, but more likely to a private individual trying to earn a living. Among the objects that Bass retrieved were ingots of solid copper—the type that we call oxhide ingots because they are in the shape of a cowhide or oxhide that might hang on a wall or be used on the floor as a rug. These copper ingots each weighed about sixty pounds and are the same as the “metal biscuits with ears” that the young sponge diver would find at Uluburun in 1982.

Bronze is frequently made by combining 90 percent copper and 10 percent tin (arsenic can be used in place of tin, although I wouldn’t recommend it). It would make sense, therefore, if there were also raw tin on board the Gelidonya wreck. And indeed there was. Unfortunately, most of it now looked more like toothpaste than raw tin, because of the corrosion caused by saltwater, and some scholars doubted the identification.

Judging from the artifacts that he excavated, Bass also said that the wreck was a Canaanite ship possibly on its way to the Aegean. This went very much against the scholarly thinking of the day, especially since it was generally thought that only the Minoans on Crete might have been sailing the seas—after all, Thucydides talks about the “Minoan thalas-socracy” or “rule of the sea.” When Bass published his book on the shipwreck in 1967, it was met with derision and disdain in some scholarly quarters. As it turned out, Bass was not only correct on all counts, but he was far ahead of his time in recognizing that others besides the Minoans had been sailing the seas.

![]()

Bass was determined to find another wreck at some point that would confirm his conclusions about the Gelidonya shipwreck. In the meantime, he founded the American Institute of Nautical Archaeology in 1972 while still at the University of Pennsylvania and then moved with it to Texas A&M University in 1976, where it—and he—has remained ever since, though they long ago dropped the “American” from their name, to reflect the international nature of their work.

In 1980, the institute purchased a boat and they began doing underwater surveys, searching for other shipwrecks. Underwater surveys can be long and time-consuming, especially back then in the 1980s, when surveys were done as if on land, by following long transects and recording what was seen. At some point, they had the bright idea that instead of doing the surveying themselves, they could simply visit the villages in which the Turkish sponge divers lived and describe to them what they were looking for. That way, they could enlist the help of the professionals who were diving to the bottom of the sea every day, looking for sponges to sell.

And, sure enough, soon thereafter, in 1982, the young sponge diver spotted the “metal biscuit with ears.” Bass was on his way toward excavating another wreck that would confirm his conclusions about the Gelidonya shipwreck. What he didn’t realize at the time was that the Uluburun shipwreck was far richer and far more important than what he had found previously. The importance of his discovery can be measured by the fact that just a few years later, in 1986, and long before the completion of the excavations, Bass received the Gold Medal Award for Distinguished Archaeological Achievement from the Archaeological Institute of America, the highest honor that his colleagues could bestow.

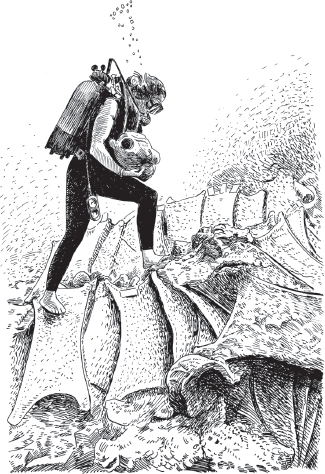

Uluburun diver

The excavation of the Uluburun shipwreck began in earnest during summer 1984, under Bass’s direction. The next year, in 1985, he turned over direction of the project to Cemal Pulak. From then until 1994, excavations were conducted virtually every summer, with a team of professional archaeologists and eager graduate students. They dove on the wreck every day, with each of them diving twice a day, but spending only about twenty minutes on the bottom each time. Decompression was a major physical danger to the divers and decompressing from that depth took a long time. To pass the time, they took to reading novels tied to a rope, once they were close enough to the surface that there was enough light to read by. They collectively worked for more than 6,600 hours while excavating the ship during those ten years, diving more than twenty-two thousand times on the wreck.

It turned out that the top part of the wreck was 140 feet below sea level, but the scatter of remains continued on down to a depth of 170 feet. Even then, they found that the front part of the fifty-foot-long ship had broken off and plunged off a cliff or ledge; it has never been recovered. Bass said that, at that depth, it felt like they had had two martinis before even beginning to work, and so they had to plan out every dive meticulously in advance. They also dove in pairs, using the buddy system, and had an ex–Navy Seal overseeing their safety, which explains the lack of reported accidents even over the course of a decade.

Bass once described, in a Nova video, what it was like to be part of the team. As soon as you get to the seabed, he said, you remove the flippers from your feet, so that you don’t accidentally excavate anything when swimming or walking close to the sand on the bottom. You grab a vacuum tube coming down from the surface in order to remove a lot of the loose sand, but then—when you move to delicate excavation—you move your hand in a continuous scooping motion in order to remove the sand carefully, because simply waving your hand back and forth does nothing but stir up the sand and cloud your vision. You are helping to map each part of the wreck—and each object found within it—meticulously, because your final plans are to be drawn within millimeter accuracy, as accurately as any plan done at an archaeological site on land. It’s hard enough to do that well on land; imagine doing it at 140 feet below the surface after having had a two-martini lunch!

The team ultimately found so many objects that the final report was still being created at the time that I was writing this book and will take up several volumes when it is finally published. In the meantime, either Bass or Pulak has published a preliminary report after the end of each season. They also have presented papers at many conferences, which have since been published.

In order to dive on the wreck, the team lived for several months each summer in wooden buildings that they constructed on the cliff face of the promontory into which the Uluburun ship had probably slammed before it sank more than three thousand years ago. There also was some living space on their dive boat, the Virazon, which was permanently moved directly above the shipwreck. With one dormitory for the men and another for the women, plus a building for the kitchen and eating area, another for the conservation and storage of the artifacts, and still one more—hanging out over the water—used as a bathroom, the team truly lived off the grid, a several-hour boat ride away from the nearest town or city.

![]()

We know when the boat sank, because of four separate pieces of evidence. First, there is a gold scarab containing the name of Queen Nefertiti that was found on board. She ruled with Pharaoh Akhenaton sometime around 1350 BCE, and so the ship cannot have sunk before that time. Second, some of the wood from the hull of the ship was recovered and dated to about 1320 BCE, using dendrochronology dating, in which tree rings are counted to provide a date for the cutting of the wood used. Third, the Mycenaean and Minoan pottery on board is of a style called Late Helladic IIIA2, which archaeologists date to the last part of the fourteenth century BCE using comparisons from other Greek sites. And fourth, they were able to use carbon-14 to date some of the brushwood that was on board. These all indicate that the ship sank about 1300 BCE, which is about thirty years after the time of King Tut’s burial in Egypt and perhaps a few decades before the time of the Trojan War.

We also now know what the ship was carrying. First of all, underneath the rest of the cargo, and spaced out along the length of the hull, were approximately fourteen large stone anchors. These were used as ballast for most of the journey, but as each one was needed, it was put into use. That way, if one of the anchors got stuck on a rock or a reef, the sailors could simply cut the rope and then retrieve another one from down in the cargo hull. Such stone anchors have been found at several sites on land, like Kition or Enkomi on Cyprus and Ugarit in coastal Syria, but none had never before been found still in place within a sunken ship from the Bronze Age.

The main cargo was oxhide ingots, made of 99 percent pure raw copper from Cyprus. There were more than 350 of these ingots on board the ship, stacked row upon row in the hold. We have one letter that was written from the king of Cyprus to the king of Egypt from about 1350 BCE, in which he apologizes for sending “only” 200 copper ingots (or talents, as they were called then); this ship shows that as many as 350 could be shipped at once during this time period. Such ingots may have been used as currency—bullion for international trade.

All told, there is more than ten tons of copper on board this one ship. Some of the ingots were so corroded that the archaeologists had to essentially invent a new type of glue, which they injected into the remains of the ingot and then allowed to harden for the entire year between excavation seasons. Then they carefully picked up each one and floated it to the surface before taking them all back to the museum at Bodrum. There they were conserved and cleaned of the corrosion that had accumulated over the centuries.

As for the tin that Bass had found on the Gelidonya shipwreck—which looked like toothpaste and was doubted by many scholars—the Uluburun shipwreck vindicated him here as well, for it contained more than a ton of tin, in recognizable forms this time, some as fragments of oxhide ingots, others as a smaller type of ingot called a bun ingot, yet others as plates and other vessels made of tin. The tin had traveled a long way already, for its origin was likely the Badakhshan region of Afghanistan, but its voyage wasn’t supposed to be over until it had reached the Aegean, most likely, although the sinking of the ship foiled that plan.

Ten tons of copper and one ton of tin will make eleven tons of bronze. Bass once estimated that this would have been enough to outfit an army of three hundred soldiers with swords, shields, helmets, greaves, and other necessary accouterments. Not only did someone lose a fortune when this ship went down, but someone also might have lost a war.

Other raw materials were on board as well, including approximately one ton of terebinth resin, which was used as incense and for making perfume, among other things. It comes from the pistachio tree and has never been found in such quantities in one place before.

The resin was being carried in some of the so-called Canaanite storage jars, of which there were about 140 on board. These are just what they sound like—transportation and storage jars made in Canaan (that is, modern-day Israel, Lebanon, Syria) that could hold any number of things. On the Uluburun ship, they were found to contain not only the resin, but also glass beads—thousands of them in some cases—as well as food such as figs and dates.

One jar held a small folding wooden tablet, with ivory hinges. It probably floated into the jar by accident after the ship sank. Inside the tablet, the two sides, which are recessed, would have originally held wax, colored yellow by terebinth resin. On this wax would have been written some sort of message, for this is what we call a diptych or a wooden writing tablet. Homer talks about such a tablet in book 6 of the Iliad, when he mentions a tablet with “baneful signs.”

Unfortunately, the wax in the Uluburun tablet is long gone. A second tablet also was found in the excavations, but the wax was gone there too. Thus, we don’t know what was originally written in either one. Was it the ship’s itinerary? Was it the manifest of the cargo? Was it a message from one king to another? We’ll never know.

Among the raw goods being transported on the ship the archaeologists recovered approximately 175 bun ingots of raw glass; most were dark cobalt blue, but others were light blue, and some were an amber color. The chemical analyses of these ingots of raw glass match those from objects of glass found in both Egypt and Greece during this time period, indicating that everyone was getting their raw glass from the same source, possibly in northern Syria or Egypt.

A cache of raw ivory on board the ship included both elephant tusks and hippopotamus canines and incisors. After these were discovered in the wreck, other scholars went back and re-examined ivory objects dating to the Late Bronze Age in various museums around the world. They had previously assumed that most were made from elephant ivory, but to their surprise it seems that most are from hippopotamus ivory. There also was a very small jawbone (mandible) from what seems to have been a Syrian house mouse, a stowaway who climbed on board the ship at some point, perhaps during a stop at the coastal port of Ugarit. And there was ebony wood as well, which comes from Nubia, south of Egypt in northeast Africa.

The cargo also contained many finished goods, some of them secured in a manner that was rather unexpected. The archaeologists were excavating large jars, similar to those that can be seen on the deck of Bronze Age ships, as painted in scenes on the walls of high-ranking Egyptian nobles’ tombs. It had always been assumed that these large jars were used to hold fresh water for the crew members to drink. But when the archaeologists began to lift one up and put it into a net, so that it could be floated to the surface, it tilted forward and pottery began to come out—fresh, brand-new, unused pottery. There were plates and dishes and bowls, and big jugs and little juglets, and oil lamps—all from Cyprus and Canaan. It seems that these large jars were not used to hold drinking water but were what we would call china barrels, used to pack and protect new pottery in transit.

There also is one very strange-looking stone item, which has been identified as a mace from the Balkans, as well as several swords. One seems to be Canaanite; one is of Aegean type; and one seems to be Italian. They were probably the personal possessions of the crew members or the captain, but we cannot be certain. The arrowheads and spearheads that were found, as well as various bronze tools, could all be either personal possessions or parts of the cargo.

There are fishhooks and lead weights too, which were undoubtedly used by the crew members to help them catch fresh fish during the voyage. The foodstuffs that have been identified from the Uluburun wreck were all products of the eastern Mediterranean, including olives, almonds, figs, and pomegranates, in addition to fish. These are pretty much the same things that a ship’s crew would be eating today in that same area.

But there are also a few fancy drinking cups, made of faience (which is halfway between pottery and glass) in zoomorphic shapes, like a ram’s head. They are usually identified as items used by royalty, which may support the idea that the ship was carrying a royal gift from one king to another. We know from textual evidence that rulers did exchange lavish gifts during this period, and so it is not out of the question that we are looking at one here, perhaps being sent from Egypt or Canaan to a Mycenaean king—maybe Agamemnon’s ancestor at Mycenae. We shall probably never know for sure.

Among the items that could be construed as worthy of a king is a single gold cup. Although pretty, it is not of much use in determining anything about the ship, its origins, or its date, because it is actually rather generic. There is an iconic photograph, now found in most archaeology textbooks, that was taken before the cup was removed from the seabed. In the picture are the gold cup, a Canaanite jar, a flask made from tin, and a rather plain-looking Mycenaean kylix. When I ask my students what the most important object in the picture is, they invariably point to the gold cup. But this would be wrong—I quote to them from the third Indiana Jones movie, telling them that they “have chosen . . . poorly.” Although the Canaanite jar is important for what it contained, and the flask is important because it is one of the few that we have that is made from tin, it is the plain-looking Mycenaean pottery vessel that is the most important piece in the picture, because its distinctive shape helped us to date the wreck.

Bass, Pulak, and their team members also found many pieces of jewelry, ranging from silver bracelets to gold pendants. One of the pendants is a marvelous piece of work, with granulated dots of gold creating a falcon or some other bird clutching a snake in its claws. Another depicts a woman holding a gazelle in each hand. Still another is a type that we can see worn by Canaanite men in Egyptian tomb paintings. There also are cylinder seals from Mesopotamia, including one made from rock crystal with a gold cap on either end, which would have been worn tied around one’s wrist or neck, and a small piece of black stone from Egypt that is inscribed “Ptah, Lord of Truth.”

Of the scarabs and other small items engraved with Egyptian hieroglyphics, the solid gold scarab of Queen Nefertiti, inscribed with her name in hieroglyphics, Nefer-neferu-aten, is the most important but also one of the smallest. This is a version of her name that she used only during the first five years or so of her reign, when her husband, the heretic Pharaoh Akhenaton, was condemning everything under the sun, except for Aton, who was the god represented by the disk of the sun. This is a rare find and one, as we have noted, that helps us date the ship, for it cannot have sunk before the scarab was made; that is prior to about 1350 BCE.

The one thing that has not been recovered from the shipwreck are bodies, or any partial skeletons at all. It may be that the survivors swam to shore or that their bodies fell victim to the fishes and other sea life while lying underwater for thirty-two hundred years.

![]()

When the wreck was first found, the excavators thought that the Uluburun ship had most likely been going from port to port around the eastern Mediterranean and Aegean regions in a counterclockwise direction, perhaps “tramping” like the Gelidonya ship would do a century later, but with a cargo that was much richer. Since then, other suggestions have been made, including the possibility that it was a cargo meant as a royal gift from one king to another, which we know occurred at the time, and that perhaps it was being sent from Egypt to Greece or from Canaan to Greece or even from Cyprus to Greece.

In every case, though, it is agreed that it was heading to Greece because, although there are objects on board that come from at least seven different cultures and that are clearly meant as cargo, the only objects from Greece are a number of Minoan and Mycenaean ceramic vessels that are used, rather than new, and two personal seals that might have been worn by someone from the Aegean. The objects found on board were probably designed to appeal to a Greek audience.

On its return trip, or perhaps on the continuation of its trip counterclockwise around the region, the ship probably would have carried a full cargo of typical Mycenaean and Minoan goods, including ceramic vessels full of wine, olive oil, and perfume destined for Egypt, Canaan, and Cyprus. Of course, it never made that return voyage because it sank at Uluburun, despite the presence of what might have been a protective deity on board the ship—a small figurine, made of bronze but covered with gold foil on its head and shoulders, hands, and feet. It was found completely corroded, but “it cleaned up nicely,” as we say in the archaeological world. The style of the figurine is typical of votive objects—that is, figures created to express both religious devotion and the desire for divine protection.

If it is the protective deity for the ship, it didn’t do its job very well. Their bad luck, though, was our good luck, because we are now able to study this ship and its cargo in its entirety and get a glimpse of what life was like during the international world of the Late Bronze Age more than three thousand years ago.