![]()

FROM DISCUS-THROWING TO DEMOCRACY

AT THE 2016 OLYMPICS IN RIO DE JANEIRO, THERE WERE competitions in forty-two sporting events, ranging from aquatics and archery to weightlifting and wrestling. But one contest from the ancient Olympics wasn’t held—the race in which the runners participated while wearing armor, including a helmet on their head, greaves on their shins, and a shield on their left arm. Similarly, there weren’t any chariot races in Rio nor was there the pankration, a no-holds-barred martial art event akin to today’s kickboxing or perhaps a combination of karate and judo, in which everything was allowed, except for biting, eye-gouging, and scratching.

The first Olympic Games took place nearly three thousand years ago, in 776 BCE. They were then held every fourth year, for more than a thousand years. Athletes came from all over the Greek world to compete, which is why we refer to the games as Panhellenic (pan meaning “all” and Hellenic meaning “Greece”). There were 293 Olympiads in all, before the Roman (and Christian) emperor Theodosius declared an end to all pagan festivals in the early 390s CE.

The search for Olympia, the site where the Olympic Games had been held, proved as big a beacon to early explorers and archaeologists as the sites mentioned by Homer. Just as Schliemann searched for Troy, Mycenae, Tiryns, and Ithaca, so too did others search for sites famous in Greek history for other reasons. Close behind the search for Olympia and its games was the hunt for Delphi and its oracle, as well as Athens for its Acropolis and Agora, birthplace of democracy.

The foreign schools of archaeology split up these sites—the Germans were excavating at Olympia by 1875; the French at Delphi by 1892; the Americans in the Agora of Athens by 1931—but Greek archaeologists also were participants in the exploration of their own heritage, just as Stamatakis dug at Mycenae after Schliemann’s initial excavations. It is on these sites that we will focus in this chapter.

![]()

The site of Olympia was not easy for archaeologists to find. After the last Olympic Games in 393 CE, the sanctuary slowly fell into disuse and was eventually abandoned. The buildings were tossed around and knocked to the ground by earthquakes in the sixth century CE, leaving the column drums from the magnificent temples fallen like parallel toothpicks. Adding insult to injury, the nearby rivers both overflowed their banks—one, the Kladeos River, had done so already in the fourth century CE while the games were still active, but the final ignominy came when the Alpheios River also flooded the area during the Middle Ages, leaving the site covered with a layer of silt and mud more than four meters deep.

It was in 1766 that the English explorer Richard Chandler first successfully located the site. By asking the locals about their discoveries of ancient ruins and using the guidebook written in the second century CE by Pausanias, just as Schliemann would do a century later at Mycenae, Chandler was able to identify the site of the sanctuary, including remains left from the Temple of Zeus, the Greek god to whom the entire sanctuary was dedicated.

When we last visited during March 2015, with a group of George Washington University students, the remains were a pleasure to behold. Small white daisies and wild red poppies mingled with ancient lichen-covered gray stones in a fresh carpet of green grass. Some of the students gave their reports about the individual monuments while wearing tiaras of woven daisy chains on their heads. Springtime in the northwestern Peloponnese region of Greece is beautiful, but the ancient Greeks came for more than just beauty. They came to honor Zeus and to win athletic competitions.

The famous games were part of the festivities that were held to honor Zeus—as much religious as they were athletic—and the temple that Chandler had identified was the most famous building at the site. It also was the largest temple discovered in Greece at the time, measuring sixty-four meters by twenty-eight meters (more than two hundred feet long by ninety feet wide). The pedimental sculptures and the metopes decorating the temple depicted a mythical chariot race, a battle involving centaurs, and the twelve labors of Heracles. It had taken ten years to build it in the mid-fifth century (466–457 BCE).

Most important, it once held the forty-foot-tall gold and ivory statue of Zeus made by the famous Greek sculptor Pheidias, which was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Alas, by the time that Chandler found the building, the statue was long gone, having been taken away to Constantinople (Istanbul) in what is now Turkey during the fourth century CE, where it was later destroyed when the building in which it was housed caught fire.

Pausanias reported that there were numerous other statues here as well, but of normal size, some of marble and some of bronze, made by some of the most famous Greek sculptors, including Praxiteles and Lysippus. It was for these famous pieces of ancient art, in part, that the first archaeologists at Olympia came, meaning that the excavations here began for much the same reason as those at Herculaneum in Italy a century earlier.

![]()

The French conducted excavations at Olympia in 1829 and recovered fragments of carved metopes from the Temple of Zeus. Alternating with triglyphs (three vertical bars), such metopes were architectural elements that frequently made up part of the decoration of Greek temples between the tops of the columns and the roof. These particular ones, depicting the labors of Heracles, are now in the Louvre in Paris.

It was the Germans, however, who contracted with the Greek government for exclusive rights to excavate the site from 1875 to 1881. Known as the Olympia Convention, the contract established a precedent for all subsequent foreign excavations in Greece. It stated that all the finds discovered during the excavation would remain in Greece, unless the government decided to present duplicates or facsimiles to the excavators, or their government, in thanks for their work. The Germans, in return, were required to publish the results of the excavation for the scholarly community, which they did quite promptly, including inscriptions, sculptures, and buildings. Their investigations have been hailed by Helmut Kyrieleis, a later director, as the first major excavation at a classical site to have “specific scientific objectives.” It was their detailed reports, in part, that prompted Baron Pierre de Coubertin, a Frenchman, to initiate the modern Olympic Games, first held in Athens in 1896.

Wilhelm Dörpfeld was associated with these early German excavations at Olympia, serving as an architect and learning the skills of an archaeologist. It was Dörpfeld who gave Heinrich Schliemann a tour of the site in 1881, when he came to see what they had found. Schliemann was so impressed by Dörpfeld that he invited him to come work at Troy, which Dörpfeld did a year later. This was a fortuitous pairing and a great partnership, for the two worked together not only at Troy but then at Tiryns. Dörpfeld subsequently directed excavations at Troy after Schliemann’s death, as we have already described in an earlier chapter. Arthur Evans once remarked that Dörpfeld—a meticulous, science-oriented scholar—was Schliemann’s greatest discovery.

A new team of German archaeologists resumed excavations at Olympia in 1937, capitalizing on the interest that had been generated by the Berlin Olympics the previous year. This second period of excavation lasted for nearly three decades, though that included a ten-year break (1942–1952) during and immediately after World War II. They too made use of Pausanias’s detailed description of the site, without which most of the buildings would probably have remained unidentified. Other investigations continued thereafter, but it was really only in 1985, under the direction of Kyrieleis, that the most recent campaign was begun at the site.

More than a century of excavation has exposed enough that it is now possible to walk through the site and see the buildings in the central sanctuary area, including the Great Altar to Zeus; the Temple to Hera; and buildings such as the Prytaneion and Bouleuterion where the administrators and council members in charge of the sanctuary and festival met. The Gymnasium and the Palaistra, where the athletes practiced and trained for a month before the games, are to one side of the sanctuary area, along with the swimming pool. The Hippodrome, where the chariot races were held, and the stadium where the foot races were run are on the other side. It was the excavation of the six-hundred-foot-long stadium, originally built about 350 BCE, which was the most expensive and time-consuming part of the project, since it involved the removal of hundreds of tons of earth. All the efforts by the archaeologists paid off, for they recovered a tremendous amount of information from inscriptions, statues, and buildings, as well as pottery and other artifacts. In 1989, Olympia was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site; nearly half a million tourists now visit it each year.

During the excavation in the 1950s of the dirt embankments on the sides of the stadium, where upward of forty thousand spectators would have watched the athletic races, the archaeologists unexpectedly came upon piece after piece of bronze armor and weapons, including twenty-two bronze helmets, as well as shields, greaves, and swords. Originally they were fastened to wooden poles or stakes driven into the earth of the embankments, in rows above the spectators. Visually it would have looked like flags flying at the top of the Los Angeles Coliseum or any high school football stadium today, but they were dedications to Zeus made by victorious warriors. The armor and weapons were placed here so that the citizens from various Greek city-states could admire the warriors’ individual strength and success or collectively give thanks for group endeavors like the Persian War.

Found among the trophies was a bronze helmet dedicated by Miltiades, the general who led the Greeks to victory over the Persians at the battle of Marathon in 490 BCE. It is a plain helmet, of the common type that archaeologists call Corinthian. Inscribed along the bottom edge of the cheek piece are the words “Miltiades presented this to Zeus.” There also is a Persian helmet, captured in the same engagement and dedicated afterward, according to the inscription that is engraved upon it: “To Zeus from the Athenians, who took it from the Medes.”

Other dedications, usually more valuable objects made of gold and silver, were housed in small buildings known as Treasuries. They were each constructed to look like a miniature temple and were built by the various Greek city-states and colonies to hold the objects sent by their citizens.

Another plain artifact with an inscription from Olympia is equally famous today, but it was not a dedication. Instead, it is a broken ceramic cup or wine jug, inscribed on the bottom with the words “I belong to Pheidias.” It is thought to have been the personal drinking cup of the sculptor himself. The Germans found it in 1958, in a building just outside the sanctuary area that must have been the workshop in which Pheidias created the colossal statue of Zeus. The building had later been converted into a Byzantine church, but its proportions exactly match the dimensions of the room in the temple where the statue stood for centuries. Two deposits of waste material excavated by the archaeologists nearby include bits of ivory, metal, and glass, terracotta molds, and tools, among which was a goldsmith’s hammer.

The games themselves grew more elaborate over the years, with new events added every so often. When the games first began in 776 BCE, they consisted of a simple footrace. Two longer footraces were added later that same century. Wrestling and boxing followed, as did the pentathlon, which involved competing in five sports—discus, javelin, jumping, running, and wrestling. Chariot races, the race in full armor, and the pankration also were added.

Not all these events were conducted as they are today. For instance, the long jumpers competed while holding weights in their hands, which they threw behind themselves while in mid-air in order to propel themselves farther. The German archaeologists unearthed some of these weights, more than two thousand years after the victors dedicated them at the site.

By about 100 BCE (and probably a good bit earlier) there were a full five days of athletics and religious festivities. The winners, of which there was only one in each competition, were each awarded a crown of laurel leaves on the last day of the games. They frequently also received much more elaborate gifts upon returning to their home city, including food and lodging for life for Athenian victors.

The popularity of the games continued even after the Romans conquered Greece in the second century BCE, until Theodosius brought them to an end more than five hundred years later. The Roman emperor Nero was especially enamored of them and even participated in the Olympics of 67 CE. While in the chariot race, he fell off before reaching the finish line but was declared the winner anyway. He also ordered that there be a public musical performance, in which he would participate, and had the town gates shut so that nobody could leave. The Roman biographer Suetonius tells us, with perhaps a bit of exaggeration, that some women faked giving birth while Nero was on stage, and other spectators jumped from the top of the sanctuary walls or pretended to be dead so that they would be carried out for their funeral, in order to get away.

Because other Panhellenic athletic competitions were held in the intervening years, the Olympic Games were held only every fourth year. In between, one per year, the Isthmian Games were held in Corinth and the Nemean Games at Nemea, and the Pythian Games were held at Delphi. At each of these sites, just as at Olympia, temples, treasuries, and athletic facilities were constructed, as were other monuments to the patron deity. At Delphi, that was the god Apollo.

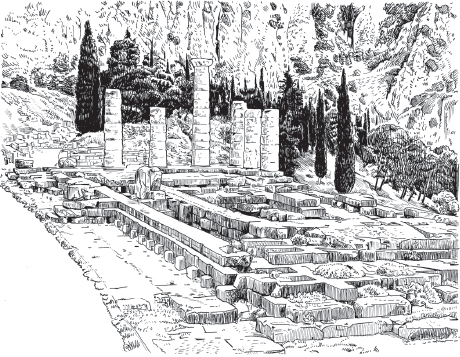

![]()

It was the Oracle at Delphi, located in the Temple to Apollo, which brought importance, fame, and wealth to the site in antiquity. Located in Central Greece among the foothills of Mount Parnassus, the oracle was personified by a sacred priestess who reportedly sat on a tripod in an inner room above a crack in the ground. Vapors oozed from this fissure, sending her into a trance and allowing the god to speak through her, giving often enigmatic answers to questions posed by the petitioners.

During the eighth and seventh centuries BCE, the oracle was frequently consulted by Greek city-states wishing to send out colonists to areas from the Black Sea to southern Italy and beyond, including Cyrene in North Africa and Marseilles in southern France. How the oracle knew what to recommend is a very good question, but it seems that most of the colonies were successful, with some eventually surpassing the mother city in prosperity and prestige. The most famous question, according to the Greek historian Herodotus, was reportedly asked by King Croesus of Lydia (in Anatolia), who desired to know whether he should go to war against the Persians, led by Cyrus the Great, in the mid-sixth century BCE. The oracle replied that if he led an army against the Persians, he would destroy a great empire. Croesus took this to be in his favor, went to war, and lost. It was his own empire that was destroyed, thus fulfilling the prophecy.

None of this has left any trace, however, as the French excavators of the site have found. No tripod, no priestess, not even a crack in the ground, although two earthquake fault lines may meet somewhere near here.

The French archaeologists were granted permission to excavate Delphi by virtue of contracts signed with the Greek government in March and May 1891. First, however, they had to move the entire modern village, which was built directly on top of the ancient sanctuary. At a cost of $150 thousand at the time (which would be nearly $4 million in today’s money), they moved all three hundred owners into new houses in the fresh village that was created and then commenced digging. Even then they still faced resistance from some of the villagers, who were not happy with the money that they had been paid for their previous houses. Eventually things settled down and the French archaeologists were able to proceed with the excavation. Their results were so remarkable that Delphi, regarded by the ancient Greeks as the navel (omphalos) of the world, is today one of the most beautiful and frequently visited tourist destinations in the country. It was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987.

These French archaeologists were not the first to dig at the site, for attempts had been undertaken from time to time during the previous decades, beginning in the 1820s. Theirs, however, was an officially sanctioned and elaborate expedition, complete with an eighteen-hundred-meter-long railroad track that was set in place to take away the huge volumes of dirt that they were removing. The dig lasted for a bit more than ten years, from October 1892 until May 1903, and was dubbed the “Great Excavation.” It was indeed great, both in terms of the discoveries that were made and the number of workers that were employed—up to 220 at one point in 1893.

Since then, nothing on a similar scale has been attempted in terms of excavation at the site, although additional short-term investigations have taken place at various times in the 1920s, 1930s, 1970s, and 1980s–1990s. Thus, there is little to discuss about modern archaeological techniques or advances that have been used at the site. Much has, however, been done in terms of the conservation and preservation of what was found in that decade of excavation more than a century ago, and the publication of what was found has been nothing short of remarkable, with more than sixty volumes published to date about the various buildings, inscriptions, and other finds.

The first season, in 1892, was very brief because they had been delayed by last-minute negotiations with the villagers, and so the first major finds began coming in 1893, with more in 1894 and the years immediately following. It must have been tremendously exciting to be on the French archaeological team during those heady days. Photography was still new at the time, but the archaeologists put it to good use. Some two thousand glass photographic plates still exist at the French School of Athens (École française d’Athènes, founded in 1846), which record some of the spectacular finds at the moment of their discovery.

Several statues, in particular, were nothing short of sensational. The matching set of young men known as Kleobis and Biton of Argos, carved in marble in the Archaic style of the late seventh century BCE, came up one at a time, in 1893 and 1894. The story of these two brothers is known from Herodotus’s Histories, where he describes how “these dutiful sons” yoked themselves to their mother’s wagon and pulled it for five miles so that she could attend a religious festival. In their honor, Herodotus says, the Argives “made and dedicated at Delphi statues of them as being the best of men.” Now the proud archaeologists and their workers had recovered these statues; the black-and-white photographs show them clustered around the heads and torsos as the statues emerged from the dirt.

Another statue, perhaps the most famous to be found at the site, is known simply as The Charioteer. Made of bronze, the lower part was uncovered first by the French archaeologists, along with its inscribed stone base, toward the end of April 1896. The upper part, with the head and face still intact, complete with inlaid glass eyes, was found a few days later, in early May. Again, photographs record the moments of discovery. The inscription records the fact that Hieron of Syracuse was victorious in the Pythian Games in 478 (or perhaps 474) BCE. He was the brother (and successor) of the tyrant Gelon and owned the winning chariot—for it was the owner, not the driver, of the chariot who was declared the winner of such races. His other brother Polyzelus (who succeeded him in turn) apparently rededicated the statue later so that he could claim the victory for himself.

Buildings and other structures were uncovered as well. Parts of the treasuries of the Athenians, the Siphnians, the Sikyonians, and the Knidians, among others, came to light, complete with fragments of their elaborate friezes and other decorations scattered in the dirt around them. In these small but beautiful buildings the named city-states stored the precious gold and silver dedications made by their citizens, though these had long since been stolen by the Roman conquerors Sulla and Nero—Nero reportedly took as many as five hundred statues from the sanctuary as well. The remains of the Temple to Apollo also made their appearance. So too did the stadium for the races in the Pythian Games, held once every four years, like the Olympic Games, as well as the site’s Gymnasium.

Inscriptions also were found; so many that sometimes dozens appeared in a single day. Among the most famous were fragments of two Delphic hymns to Apollo from the second century BCE. They were found in 1893, inscribed on stones discovered within the Treasury of the Athenians. In between the lines of texts are symbols representing vocal and instrumental notations, so that it was possible to attempt to perform the hymns as originally intended, which was promptly done in mid-March 1894 for the Greek king and queen. Additional performances were held in St. Petersburg and Johannesburg, but it was the one in Paris that same year, at a conference organized by Pierre de Cou-bertin, that persuaded others to join his movement for the revival of the Olympic Games.

The Sacred Way also was uncovered, winding its way up the mountain from the sanctuary entrance to the stadium like a snake—as befitting the original name for the area, Pytho, before it was renamed Delphi. Today we can all climb the same serpentine path taken by pilgrims and tourists, as described by Pausanias. Taking in the views of the sacred olive groves in the valley and the view of the Peloponnese across the gulf never fails to fill me with a sense of awe and wonder, the two key ingredients for a religious experience in ancient times, and perhaps modern times as well.

Coming up from the terrace of the much-smaller Athena Sanctuary below, where the Gymnasium also is located, we cross the modern road and start out in a paved area just inside the main entrance to the site. We immediately begin walking past statues and other dedications made by individuals as well as city-states, standing on both sides of the Sacred Way. Many of these commemorate military victories, including a dedication by the Athenians marking the victory over the Persians at Marathon in 490 BCE and an entire building commissioned by the Spartans in memory of their victory over the Athenians at Aegospotami in 405 BCE as the final battle of the Peloponnesian War.

As we proceed up the path and sweep around the first bend to the right, we pass by the Treasuries erected by the various Greek city-states. All these are now long gone, as mentioned, along with the riches that they once contained. Only their foundations were left, uncovered by the French archaeologists in 1893–1894, along with pieces of their once richly painted metopes and friezes—depicting battles between gods and giants, the exploits of Theseus, and a variety of other scenes.

As we continue up the hill, we have the sheer wall of the foundations of the Temple of Apollo on our left, for we are still far below the ground level of the temple. Up against this is the Portico of the Athenians. Now bare of offerings, the portico has only an inscription, which reads “The Athenians dedicated the portico and the arms and the figureheads which they took from their enemies.” Good detective work by a French scholar in 1948 proved that the inscription refers to cables belonging to a bridge that the Persian king Xerxes had constructed when crossing the Hellespont between Anatolia and Greece during his invasion in 480 BCE. The Athenians retrieved the cables as souvenirs after they defeated Xerxes at Plataea and Salamis that year and dedicated them here in this portico at Delphi.

As we round the next bend, turning to our left, we also come around the corner of the temple and are nearing its front entrance. We can see in the distance where the Tripod of Plataia—sometimes called the Serpent Column—once stood, opposite the Altar of Apollo and the entrance to the temple.

This golden tripod, set on a base of three intertwined bronze snakes, commemorated the Greek victory over the Persians at the Battle of Plataia in 479 BCE. The tripod itself was stolen or destroyed long ago. The bronze base made of the three snakes, on which was inscribed the names of the thirty-one Greek city-states whose men fought in the battle, also was removed, but in its case we know who took it and where it went—it was the Roman emperor Constantine the Great who moved them in the fourth century CE to his new capital city of Constantinople, now better known as modern Istanbul. They are still there today and can be seen in the middle of the Hippodrome, in Sultan Ahmet Square, although their heads (or parts of them) are in the nearby Istanbul Archaeology Museum.

Venturing off the Sacred Way and into the precinct of the Temple of Apollo, we see the reconstructed ruins, with some of the original six pillars standing upright in front; six more would have been at the back. Another fifteen would have been on each side, two more than usual for this type of temple, because it had to be lengthened in order to accommodate extra space for the oracle, the most famous in all of Greece.

Even the present temple itself is reported by Pausanias to be the fifth iteration, though his account might not be entirely believable since he claims that the first three were built from laurel branches, beeswax, and bronze, respectively, before the fourth one was finally built of stone. More dependable, perhaps, are the findings by the archaeologists that there were at least two previous temples in this location. The first one burned down in 548 BCE, and an earthquake in 373 BCE destroyed the second one. The one visible now was built later in the fourth century; the French archaeologists found an inscription listing the benefactors who helped pay for its reconstruction and were also able to ascertain that it took almost forty years to rebuild it, in part because of the attacks on Greece by Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great, during that period.

Retracing our steps and leaving the temple, we return to the Sacred Way and turn left again, heading around the far side of the temple. Off to our right as we turn this corner are additional statues and other dedications, with a large colonnaded building known as a stoa in the distance behind them. Attalos I, a Hellenistic monarch who ruled Pergamon (in what is now Turkey) during the third century BCE, built and dedicated this stoa. His younger son, and eventual successor, Attalos II, built a similar stoa in Athens in the mid-second century BCE.

As we reach the far end of the temple, we see to our right the great theater. We see also, above it all, the stadium, excavated by the French in 1896 and in which the races were run during the Pythian Games. Overall, the same sorts of competitions and races were held here at Delphi as at Olympia, according to Pausanias, with a wreath going to the victor of each competition. These started soon after 591 BCE and were held every four years until the 390s CE, when the entire sanctuary, including the oracle and the Games, was closed by the same order of Theodosius that closed down Olympia.

![]()

Athens also has a stadium, but it is modern rather than ancient—used in both 1896 and 2004, the only two times that the modern Olympics have been held in Greece. The city did not play host to any such games in antiquity, though it too had a patron deity—Athena—just as Olympia had Zeus and Delphi had Apollo. Rather, Athens saw the birth of momentous innovations, including the invention of democracy, and was home to philosophical giants such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle.

The Acropolis, or high point of the city, is justifiably famous and was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987. Greek excavators, and Germans as well, including Wilhelm Dörpfeld, uncovered the remains of the buildings here beginning in the 1800s, including the Parthenon, the Erechtheium, and the diminutive Temple of Athena Nike, in addition to numerous marble statues and inscriptions. It is from the Parthenon that the so-called Elgin Marbles came, removed by Lord Elgin and sent to England by 1805, ending up in the British Museum a decade later. The Greeks are still trying to get them back. The archaeologists also uncovered remains on the slopes of the Acropolis, including the theater and the Odeion, some dating from as late as the Roman period but now in use again today for dramatic performances put on by local and visiting artists.

It is the Agora, or marketplace, however, that was daily visited by more Athenians, since it was downtown Athens and the heart of the city. This is where the lawcourts were, as well as some of the most important buildings in the city, including the Bouleuterion, where the senate met, and the Tholos, where the executive committee of the senate met in private; the Metroon, where the archives were kept; various stoas; and other major administrative and legislative edifices. It also was where many commercial shops were located, as appropriate for a marketplace, and served as a meeting place for the citizens, including Socrates, among others. The Hephaisteion, a major temple to Hephaistos (the god of the forge) that was excavated by the Germans in the 1890s, overlooked everything at one end of the Agora. As befits such a major downtown area, it was almost always changing, so that the Agora of the fifth century BCE looked quite different from that of the first century CE, in terms of buildings and layout, though its basic function remained the same throughout.

The Agora has been under almost continuous excavation since 1931 by the American School of Classical Studies in Athens and the activity here reflects changes in techniques and technology during the past eighty-five years. The archaeologists have uncovered all the buildings mentioned in the preceding overview, as well as the streets and paths along which Pericles and Socrates walked, with much more still to be found. The newest excavations now utilize a software program called iDig, for use on the iPad, which was invented by Bruce Hartzler, the technological guru of the excavations. With this specialized program, which moves beyond the off-the-shelf programs used by the excavators at Pompeii several years earlier, the Agora archaeologists can record the excavation data even more quickly, easily, and accurately in real time.

The area is still heavily populated, of course, with modern shops, restaurants, and houses in one of the busiest parts of Athens, at the foot of the Acropolis. Before the archaeologists can excavate anywhere, therefore, they have to purchase the houses and other structures that are currently standing in the area where they intend to dig. Under the successive directorships of T. Leslie Shear Sr., Homer Thompson, T. Leslie Shear Jr., and now John Camp II, some four hundred houses and other buildings have been purchased and demolished, with subsequent excavation done beneath them. The excavators must then proceed carefully through the layers of stratigraphy, working backward through time from the Ottoman period to the Byzantine period and then the Roman period before reaching the levels of Classical Athens and eventually the Bronze Age.

Excavating every summer, the archaeologists have slowly and carefully revealed the history of this most famous marketplace. They have found boundary stones that mark the edge of the area, each inscribed quite literally “I am the boundary of the Agora,” as well as buildings known from the writings of ancient authors across the centuries, including the Altar of the Twelve Gods, the Monument of the Eponymous Heroes, the Stoa of Attalos, and perhaps even the house of Simon the Cobbler (where Socrates sometimes taught), and the prison in which Socrates was held during his trial for corrupting the youth and not believing in the gods.

This also is the birthplace of democracy, and so it is not surprising that the archaeologists have found ballot boxes and the actual bronze ballots themselves, which could be held between thumb and forefinger until deposited in the ballot box, so that nobody else could see how you were voting. They also have recovered allotment machines used to choose jurors for trials, water clocks used to time speeches, and inscribed potsherds (ostraca) that were used when voting to remove someone perceived to have grown too strong and influential in politics, thereby giving rise to our term ostracism. Many of these are now housed in the Stoa of Attalos, which was reconstructed in the 1950s, using the same type of materials as the original, and which now serves as the museum for the site.

The Agora also happens to be where I was a young and eager volunteer team member in 1982, during the summer between college and graduate school, for the policy during the past couple of decades has been to use team members who are upper-level college or graduate students intent on a career in archaeology. I didn’t know it at the time, but there were at least twelve other volunteer team members working with me that summer who are now also senior archaeologists.

I had the privilege of digging in the Stoa Poikile—the Painted Stoa—which had first been detected and identified a year or so earlier. In antiquity, this building had been famous for the large paintings with which it was decorated—they were still in place when Pausanias came through, six hundred years after they had first been installed, but are now long gone, of course.

I also had the dubious, but literally cool (and wet), thrill of excavating in an ancient well next to the Painted Stoa. This involved stripping down to only shorts and donning a bandana for my head (to keep the mud out of my hair and eyes) and then being lowered via a bucket, as if I were going down for water. Once at the bottom, I stepped out of the bucket into an ooze of muck and began to dig straight down in a very narrow and claustrophobic area into which I barely fit. I, and other similarly small diggers, spent many hours squatting in that soggy environment over the course of the season, carefully excavating intact vessels, sherds, and other artifacts that had either accidentally fallen in or been deliberately tossed in as garbage long ago, and retrieving them from the mire in which they had been preserved.

Excavating in downtown Athens is a novel experience, for at any given moment there are dozens of tourists watching your every move through the chain-link fence high above the excavation area. Revenge comes swiftly, though, for each afternoon we were able to walk through the crowds in the Plaka on our way back home and have them magically part in front of us the entire way, because we were liberally coated with dirt or mud—especially if we had been digging in the well that day. It was a summer that still ranks highly as a unique experience among the more than thirty seasons that I have been in the field.

![]()

All three sites—Olympia, Delphi, and Athens—are known to anyone who has read about ancient Greece. Because of two centuries of archaeological work, it is possible to wander through the monuments at those sites and get a sense of what it might have been like there in ancient times. Apart from a few select buildings, however, primarily in Delphi and Athens, modern archaeologists have not reconstructed most of the ruined structures, and so the modern tourist must be actively involved and engaged at the sites in order to picture them as they once were.

The three sites discussed here must suffice to represent all the others in Classical Greece. They also represent the development of classical archaeology in this region as well, as it evolved from a search for statues and the location of famous sites to a scientific endeavor focused on asking and answering questions about the lives of ancient Greeks and their accomplishments. Everything else aside, though, it is simply an amazing feeling, sending chills down your spine, to sit in the same theater as did Euripides, stand inside Socrates’s jail cell, visit the same Temple to Apollo that held the Delphic oracle and Croesus’s representatives, or run a race in the original Olympic stadium. Archaeologists, and archaeology, have made all this possible.