![]()

ALTHOUGH SITES IN MODERN ISRAEL AND PALESTINE ARE perhaps better known to the general public because of their biblical connections, they are not necessarily the most extensive or impressive archaeological sites in the Middle East. Other ruined cities and ancient tells abound farther north and east in Syria, Jordan, and Iraq, though western tourists visit them less frequently because of their remoteness and because of political instability in the past several decades. We have already touched on a number of the sites, including Ur, Nimrud, and Nineveh in Iraq. Here we will briefly describe three more—Ebla and Palmyra in Syria and the desert entrepôt of Petra in Jordan.

Ebla (modern Tell Mardikh) first made headlines around the world in the 1970s. Paolo Matthiae from the Sapienze University of Rome and his team began digging at the site in 1964 and continued almost until the present—nearly fifty years in all. It has taken that long to excavate because the site is absolutely huge, covering about 140 acres. The earthen ramparts that protected the city can still be seen clearly, though there is now a road through them, on which one can drive in order to gain entrance to the rest of the site. There is a huge lower city and then a citadel—a higher mound—right in the middle of the site. On the citadel are the royal palaces and administrative buildings.

Four years after starting the excavation, Matthiae’s team found a statue that had been dedicated nearly four thousand years earlier by a local man named Ibbit-Lim. In the inscription, this man said he was the son of the king of Ebla. This was quite a revelation, since previous scholars had thought that Ebla was located farther north in Syria, not here at Tell Mardikh. After further digging, they were able to confirm that they had indeed found ancient Ebla. As it turns out, we now know that Ebla is an extremely important site with a long history dating all the way back to the third millennium BCE and continuing until it was destroyed in about the year 1600 BCE.

Matthiae and his team spent the first nine years working on the portion of the mound and the buildings that dated to the second part of its occupation, from about 2000 to 1600 BCE. They were interested in this period in part because it was the time of the Amorites, who are known from the Bible, and the time of Hammurabi of Babylon, who ruled just after 1800 BCE.

It was only after 1973 that Matthiae’s team began to work on the earlier phase of occupation, which dates from about 2400 to 2250 BCE. The very next year they made a discovery that catapulted Ebla, and themselves, into the history books. That was the year when they found the first clay tablets at the site. They found more in 1975 and still more in 1976.

There may be as many as twenty thousand tablets in total, most of which were found in two small rooms within so-called Palace G, still lying on the floor where they had fallen after the shelves on which they were placed had burned and then collapsed. They mostly date between 2350 BCE and 2250 BCE. Finding this large a library from the Early Bronze Age led to headlines around the world. Soon thereafter they made headlines again, and a controversy was ignited, because the initial decipherment by the original epigrapher of the expedition, Giovanni Pettinato, suggested that Sodom and Gomorrah were mentioned, as well as figures from the Bible, such as Abraham, Israel, David, and Ishmael.

It’s hard to recall now just how excited people got, but the euphoria many felt soon dissipated when subsequent research by epigraphers showed that the tablets said nothing of the sort. No Sodom or Gomorrah; no Abraham, Israel, David, or Ishmael. The mistake in interpretation had been made because the tablets were written in a previously unknown language, now called Eblaite, which made use of Sumerian cuneiform signs. Pettinato thought he could read it, since he knew Sumerian, the earliest known written language of southern Iraq a thousand miles away, but he ended up completely mistranslating it.

Subsequently, Pettinato cut his ties with Matthiae and also resigned from the international committee that Matthiae had appointed to translate and publish the tablets. He continued to publish about them, however, in several books and articles, even though a new chief epigrapher, named Alfonso Archi, from the University of Rome, had replaced him.

The Ebla tablets are extremely important historically, even though they contain no biblical references at all. They do include lists of kings who ruled at Ebla; treaties; place names; evidence of international trade; and confirmation of the existence of a scribal school, where students learned how to read and write. They also proved that Ebla was a major center, ruling over a kingdom that we previously had no idea existed. This is an extremely good example where the textual evidence found by the archaeologists supplements and amplifies the other archaeological data that have come to light over the years.

As to the archaeological data, a number of the palaces and buildings at Ebla were destroyed by fire, which was terrible for them, but very good for the archaeologists, because it preserved the ruins and some of the artifacts within them. The smaller objects include a human-headed bull figure made of gold and steatite and fragments of ivory that once adorned pieces of wooden furniture. The furniture is now long gone and most of the ivory fragments were burnt black by the fire, but the fragments do survive and can be somewhat reconstructed. There’s also a fragment from the lid of a stone bowl that has the name of the Old Kingdom Egyptian pharaoh Pepi I (circa 2300 BCE) inscribed on it, which implies some sort of connection, even if indirect, between Egypt and Ebla.

Matthiae and his team stopped digging at the site in 2011 because of the Syrian civil war. Since then, it has been damaged and looted mercilessly. Tunnels have been dug; burial caves full of skeletons have been ransacked, with the bones thrown away; and incalculable harm has been done. Only when the current violence racking the country has been reduced and it is deemed safe to return to the area again will we know the extent of the looting and damage.

![]()

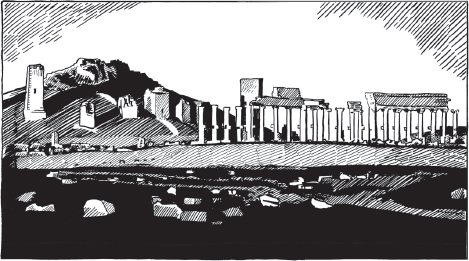

But Ebla is not the only ancient site in Syria—or elsewhere in the Middle East—to have been affected by recent violence in the region. The desert site of Palmyra also suffered damage as a result of mortar fire and other actions during the Syrian civil war, especially in 2012 and 2013. It was again in the news in May and June 2015 and suffered even more damage, when the forces of ISIS overran the site, and then again in August 2015, when ISIS killed Dr. Khaled al-Asaad, the former director of Palmyra Antiquities. Later, they also blew up two of the most famous temples as well as other monuments at the site, including the Triumphal Arch that had been standing for nearly two thousand years, sparking a worldwide outcry against their actions. They were finally dislodged and ousted from the site by Syrian forces in March 2016.

The Triumphal Arch had stretched across the main street of the city, near its eastern end. The Roman emperor Septimius Severus built it around the year 200 CE, possibly to celebrate his victory over the Parthians in Mesopotamia, an area not too far from Palmyra. Just six months after ISIS blew up the arch, it was recreated in Trafalgar Square in London, using three-dimensional technology and Egyptian marble, at two-thirds its original size. After being on show for three days, the replica was sent to be displayed in other cities around the world, including New York and Dubai.

As much of the world now knows, the ancient site of Palmyra is located in an oasis deep in the Syrian desert, to the northeast of Damascus. It is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site, having been given that designation in 1980. Known as Tadmor in antiquity, the city was active already during the Bronze Age in the second millennium BCE, but had its real heyday during the time of the Roman Empire, especially during the first through third centuries CE, when it was a major Nabataean city.

Triumphal Arch, Palmyra

Although the Nabataeans themselves are still a bit of a mystery, we know that they were major players in the international trade routes that connected the Roman Empire to India and even to faraway China. Palmyra was one of their cities, serving as a major stop on the caravan routes leading across the desert. Its architecture reflected foreign influences, especially Greco-Roman and Persian. The city rebelled against the Romans in the early 270s CE, in what is known as the rebellion of Queen Zenobia.

Zenobia was married to the King of Palmyra. He was assassinated in 267 CE, when their young son was only a year old, and so Zenobia assumed the throne as regent. Soon afterward she initiated a revolt against Rome that lasted for five years or more. Initially, she and her army had a great deal of success—capturing Egypt, taking over the rest of Syria and what today we would call Israel and Lebanon, and even portions of modern-day Turkey.

It was only in 273 CE that the Roman army crushed the Palmyrene army and put down her rebellion, after which the Roman emperor Aurelian destroyed the city. The city was rebuilt, but it was never the same again. According to some ancient sources, Zenobia herself was taken to Rome as a prisoner and was marched through the streets in golden chains the following year as part of the triumphal parade that Aurelian staged to celebrate his victory. What happened to her after that is open to debate—marriage to a Roman, execution, and suicide are all various tales of her final days that have come down to us from ancient authors. Still, along with Boudicca, who had led a revolt against the Romans in Britain two centuries earlier (in 60–61 CE), Zenobia remains one of the best-known female military leaders from antiquity.

The first major excavations at the site, especially of the Roman-period ruins, began in 1929 by French archaeologists. The remains that they uncovered, including the Temple of Bel and the Agora, or marketplace, are very impressive, especially the parts that have been partially reconstructed. Both Swiss and Syrian archaeologists also have excavated there, but the most consistent presence has been that of Polish archaeologists, who were excavating right up until 2011, when they were forced to leave at the beginning of the civil war in Syria, before ISIS invaded the area.

In calmer and safer times, Palmyra is an amazing place to visit, especially at sunrise and sunset. A favorite shot for photographers at either dawn or dusk is the four pylons, known collectively as the Tetrapylon, which was built at an intersection about halfway down the main street, half a kilometer or so from its eastern end. Septimius Severus erected them at the same time as he erected the Triumphal Arch. Of the pylons now visible, one is original and the others are replicas of concrete that were raised in 1963 by the Syrian antiquities department.

The street itself is colonnaded and stretches for more than a kilometer, from the Triumphal Arch and the Temple of Bel at its eastern end, past the Roman theater that could seat thousands of people, to a huge funerary temple at the western end. On the columns, about two-thirds of the way up, are little ledges or pedestals on which stood statues of people. These were the donors who had paid for the construction of the street and the colonnade. The inscriptions just below the statues include details about their names and families, from which we have learned quite a bit about the inhabitants of Palmyra.

As for the huge Temple to Bel, or Ba’al, who was originally a Canaanite god from the second millennium BCE, the altar within the temple was consecrated in 32 CE. The temple as it looked until fairly recently was probably completed about a hundred years later, in the second century CE. Unfortunately, this is one of the temples that ISIS blew up in late August 2015, thereby destroying a beautiful monument that, like the Triumphal Arch, had been standing for nearly two thousand years.

Also among the ruins at Palmyra is the camp that the Roman emperor Diocletian built for his soldiers at the end of the third century and beginning of the fourth century CE, which has been a focal point of archaeological excavations. There is also a castle that a local Arab emir built high up on the hill overlooking the city in the seventeenth century CE, which is still there today and worth a visit, provided that the situation in Syria permits.

![]()

Palmyra is only the second-most-famous Nabataean site now, thanks in part to Indiana Jones. Even though he is not an accurate portrayal of a real archaeologist, the third film of the series, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, managed to bring the UNESCO World Heritage site of Petra to the world’s attention.

View of the “Treasury” at Petra

Located in the Jordanian desert a few hours’ drive south from the modern capital city of Amman, Petra was named one of the New Seven Wonders of the World in an Internet poll conducted in 2007. It is on the bucket list of many people as a place to visit, especially now that there are huge five-star hotels with air conditioning in which one can stay. The Jordanians have been careful to protect this site, which now stands in tremendous contrast to the damage done at Palmyra, where the violence in Syria made such protection of the ancient site impossible.

Although people were living in the area perhaps as early as the fifth century BCE, the city rose to prominence with the Nabataeans beginning in the fourth century BCE. It continued to flourish for more than five hundred years, including and especially during the time when the Romans were in this area, from the early second century CE on. Then, after an earthquake destroyed nearly half of Petra in the mid-fourth century CE and a second one hit in the sixth century CE, everything came to a halt—no more building activities, no more minting of coins.

Petra seems to have been the center of the Nabataean confederation of cities, which were focused on controlling the lucrative trade in frankincense, myrrh, spices, and other luxury goods across the Arabian peninsula, connecting Asia to Egypt. They are known for their hydraulic engineering, which allowed them to bring water from the occasional flash floods in to Petra through a series of dams, canals, and cisterns.

After the city was essentially abandoned later in the seventh century CE, it was basically lost to history and remembered only by the locals living in its immediate vicinity. It was not until 1812 that Petra was “rediscovered” by the western world. That year, a Swiss explorer named Johann Burckhardt came through the area. He was dressed in the Arab garments of the day and called himself Sheikh Ibrahim Ibn ‘Abd Allah. In this getup, and with an excellent command of Arabic, he was able to travel throughout the Middle East from 1809 until his death from dysentery in 1817. He was just thirty-two years old when he died.

Others followed in his footsteps, including the first US archaeologist. This was John Lloyd Stephens, who emulated Burckhardt in 1836 by dressing as a merchant from Cairo, renaming himself Abdel Hasis and riding down the Wadi Musa into Petra.

John Burgon’s 1845 poem “Petra” describes the buildings as “from the rock as if by magic grown, eternal, silent, beautiful, alone!” It ends with the rather immortal lines “a rose-red city half as old as time.” In fact, Burgon had never seen Petra himself. He wrote his poem solely from descriptions he had read about the site, especially the travel account published by Stephens a few years earlier, before Stephens headed off to the Yucatán and his famous Maya discoveries.

The cliff faces into which many of the remains at Petra are carved do turn rose-red at certain times of the day, but they also turn many other colors as well, at various angles of the sun. It is a veritable photographer’s paradise, in addition to being a wonderful archaeological site.

Excavations at the site first started in 1929 and are still ongoing today. Philip Hammond, from the University of Utah, led the initial US expedition to Petra, which started in the 1960s. Hammond, who died in 2008 and is usually described as a colorful character, reportedly used to ride around on a white horse during the excavations.

Riding horses, donkeys, or camels is still one of the primary ways to enter the site today. The first view of the site, after a half-hour or more of riding down the Siq, or canyon, is absolutely amazing—as anyone who has seen the Indiana Jones movie can attest, even if they haven’t yet been to the site themselves.

The formal name of the Siq is the Wadi Musa. It’s the way that most tourists enter Petra, just as Stephens did a century and a half earlier. It’s a very narrow canyon, which twists and turns through sheer rock that towers high above on both sides.

This was probably not the main entrance to the city, but rather more of a ceremonial entrance. The final view, featured on postcards and photographs everywhere, is absolutely breathtaking, for the narrow canyon walls suddenly open up onto a huge plaza or open space in front of what we now call the Treasury, which is more formally known as the Khaznah. As Stephens later wrote, “the first view of that superb façade must produce an effect which could never pass away. . . . Even now [a year later] . . . I see before me the façade of that temple; neither the Colosseum at Rome, grand and interesting as it is, nor the ruins of the Acropolis at Athens, nor the Pyramids, nor the mighty temples of the Nile, are so often present in my memory.”

The Khaznah was the focus of the Indiana Jones film. The Nabataeans carved it out of the soft sandstone of the cliff face, as they did with many other buildings and structures at Petra. Don’t believe the film, though; the interior rooms of the Khaznah, or Treasury, are actually very small and there isn’t space for too many people to be inside at any one time, even if they include a penitent man. It was probably built to serve as a tomb and was never meant to hold many people. It is called the Treasury because of local folklore that there was gold or other valuables hidden in the large urn on the façade, but the urn is solid stone—although it is now riddled with bullet marks from efforts to blast it apart and collect the treasure.

Near the heart of Petra is the Street of Façades, which are actually tombs carved into the cliff face, and then the remains of the Roman theater, which could hold more than eight thousand people in thirty-three rows of seats. A little further on are the so-called royal tombs, which are again carved into the cliff face. The original occupants of these tombs are debated—we don’t really know whether they were royal. Even the names don’t help, since they are mostly modern designations, like the Urn Tomb, the Silk Tomb, the Corinthian Tomb, and the Palace Tomb. The only tomb whose occupant may be known is the Tomb of Sextus Florentinus, who was the governor of the Roman province of Arabia in the second century CE.

Farther down the Colonnaded Street, which gets this name from the columns lining it, is the so-called Great Temple. It might not be a temple at all, but it has been called the Great Temple ever since 1921 or so. Some think that it might be the major administrative building for the city, but nobody knows for certain. There are elephant heads on the tops of some of the columns in this structure, but they do not help in figuring out the purpose that it served.

Archaeologists from Brown University have been excavating the Great Temple, as well as other parts of Petra, for the past several decades, first under the direction of Martha Joukowsky and most recently under the codirection of Susan Alcock and Chris Tuttle. In 1998 a huge pool measuring about one hundred fifty by seventy feet and up to eight feet deep, as well as an elaborate system for filling it with water, was found and subsequently excavated by Leigh-Ann Bedal, who was a PhD student at the University of Pennsylvania at the time and now teaches at Penn State Erie, the Behrend College. She was leading a team of international, but mostly US, archaeologists. They also found the remains of what was probably an elaborate garden built in conjunction with the pool, which would have been an amazing sight in antiquity, in this dry desert region.

On the hill opposite is the Temple of the Winged Lions that—no surprise—has statues of winged lions in it. It was probably built in the early first century CE and then destroyed in an earthquake a little more than three hundred years later. It was first found in 1973 using remote sensing and has been excavated by US teams ever since.

In the nearby church, which is built over Nabataean and Roman ruins and dates to the end of the classical period—the fifth and sixth centuries CE—mosaics were found, including one that depicts the seasons. In 1993, while in the process of building a shelter to protect the mosaics and the remains of the church, archaeologists from ACOR (the American Center for Oriental Research) uncovered at least 140 carbonized papyrus scrolls within a room in the church.

Dating from the sixth century CE, the scrolls had been caught in a fire that, ironically, ended up preserving some of them, although most are now illegible. Papyrologists, experts at deciphering ancient texts, have been able to read a few dozen of them and to determine that they are written in Greek. Most of them have to do with various economic matters, such as real estate, marriages, inheritances, and divisions of property, one of them detailing a case involving stolen goods.

From this part of Petra, it is possible to proceed on a long stairway to the upper reaches of the site, where the huge temple known as the Monastery lies. It is every bit as monumental as the Treasury far below, but the climb to visit it is so arduous that it doesn’t get as many visitors. Like the Treasury, the façade of the Monastery is carved into the living face of the rock. It is approximately 130 feet high, just like the Treasury, but fully sixty feet wider.

From here, there is a commanding view over the entire area. Even though most of the guidebooks say to climb up to the Monastery in the late afternoon, I would argue that the hour-long climb is best undertaken in the early morning, before the temperature rises too high. I once was able to stay overnight in the old excavation dig house right in the heart of all these ruins and was able to wake up and begin hiking before dawn. My arrival at the top before daybreak guaranteed an amazing vista as the sun appeared over the horizon—a view that I will never forget. I was able to stop and reflect in utter silence on the long history of the region, and the remarkable city that was lost for hundreds of years to the outside world, before starting the descent back down.

![]()

Palmyra, Petra, and Ebla are just three of the incredible ancient cities that have been excavated in Jordan and Syria. I equally could have spent time describing the wonders of Jerash and Pella in Jordan, Mari and Ugarit in Syria, and a dozen other remarkable sites. The tragic consequences of the ongoing conflict in the Middle East should serve to remind us of just how precious—and fragile—these fragments of the past can be.