![]()

GIANT HEADS, FEATHERED SERPENTS, AND GOLDEN EAGLES

AT THE SITE OF TEOTIHUACÁN, INHABITED FROM ABOUT 100 BCE to about 650 CE in a region approximately fifty kilometers northeast of Mexico City, a secret tunnel was detected in 2003. It led from one of the plazas near the edge of the city to the Temple of the Feathered Serpent and was found after heavy rains opened up a small hole about eighty feet away from the temple. Archaeologists brought remote-sensing devices—specifically radar—and then mapped it. Led by Mexican archaeologist Sergio Gómez, excavation has been going on ever since, using remote-controlled robots in some places and pure hand labor in others.

The tunnel is more than 330 feet long, ending at least forty and perhaps as many as sixty feet directly below the temple. It was sealed about eighteen hundred years ago with at least six walls deployed to block the tunnel at various points along its length. During their meticulous excavations in the tunnel, archaeologists have found more than seventy thousand ancient objects as diverse as jewelry, seeds, animal bones, sea shells, pottery, obsidian blades, vessels with animal heads, rubber balls such as were used in the Mesoamerican ball games, hundreds of large conch shells from the Caribbean, and four thousand wooden objects.

The tunnel ceiling and walls are coated with a glittery powder, perhaps ground-up pyrite or a similar substance, which would have caused them to sparkle and shimmer in the light of torches. At the bottom of the tunnel are three chambers, and offerings that include four large figurines of green stone, remains of jaguars, and jade statues. There are also significant quantities of liquid mercury, which may have represented an underworld river or lake. The area beyond has yet to be investigated and could hold the bodies of the earlier rulers of the city.

![]()

We already have discussed a few of the sites found in Central America, namely Palenque and Chichén Itza. In addition to them, some of the most recent and exciting discoveries in New World archaeology have been taking place at the Aztec site of Tenochtitlán, dating to about 1350 CE and located underneath downtown Mexico City, as well as at the site of Teotihuacán that we have just mentioned. Europeans have known about these sites since the Spanish invasion of Mexico in the sixteenth century. But those early Spanish invaders didn’t know of the Olmecs.

So, let’s start back in the 1930s and 1940s, with the discovery of the Olmec civilization. The Olmecs created the earliest known civilization in what is now modern Mexico, flourishing from at least 1150 BCE (and perhaps as early as 1500 BCE) until about 400 BCE. Ironically, they were the last of the Mesoamerican civilizations to be discovered by modern archaeologists. The general public remembers them now primarily for the seventeen giant stone heads and other sculptures that they have left us. It was Matthew and Marion Stirling, Smithsonian archaeologists, and a National Geographic photographer named Richard Stewart who first brought the Olmecs to the attention of the world.

These archaeologists were not the first Westerners to have come across evidence of this civilization. The first known sculpture that can be attributed to the Olmecs was published already in 1869. It had been discovered a few years earlier by a local worker on a farm in Veracruz, on the Caribbean coast of Mexico, near the village of Tres Zapotes (meaning “three sapodillas,” after a type of tree found in the region). The name of the village is now also used for the nearby Olmec site where the farmer found the sculpture.

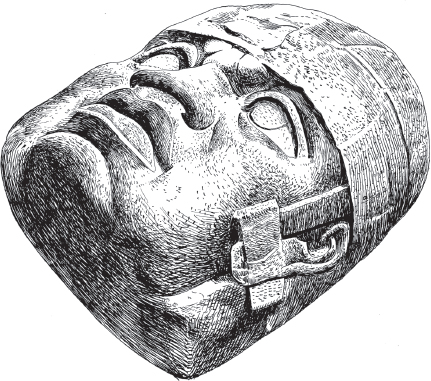

As the story goes, the farmer thought at first the object was an overturned iron cauldron, but to his surprise it turned out to be a colossal head made of volcanic stone. The face is squat, with large eyes, nose, and lips. A helmet—which looks a lot like an early football helmet made of leather—covers the top of the head and down to the eyebrows. There is nothing below the chin: no neck, no body, no arms, and no legs. There is just the head. Because it looks about as wide as it is tall, it basically resembles a large carved billiard ball, except not quite so round. It was later re-excavated by Matthew Stirling in 1939 and is now known as Tres Zapotes Monument A.

As was often the case, initial discussions—and even some more recent discussions—of these giant heads and of the Olmecs in general sought to link them to Egypt, Phoenicia, people from Atlantis, ancient astronauts, and even China and Japan. They are, of course, not related to any of the above but are indigenous to the region.

The name “Olmec”—or “Olmeca”—means “the people of the rubber country.” It’s not what they called themselves, but rather is what the Aztecs called their archaic descendants who still lived in the same general region at the time of the Spanish conquest in 1521. Archaeologists have taken to calling this region Olman, meaning the “Rubber Country”—basically, the hot and humid area of the lowlands that stretch from modern southern Veracruz to western Tabasco. At the moment, we have no idea what their name actually was, since the few written records carved on stone left to us by the Olmecs have not yet been translated.

The Stirlings and Stewart were also not the first archaeologists to explore the region. That honor goes to a two-person expedition from Tulane University in New Orleans, Frans Blom and Oliver La Farge, who had set out in 1925 to search for more remains of the Maya. Instead, they found the remains of the Olmecs, including at what is now one of the best-known sites, La Venta, where they discovered another colossal stone head, altars, stelae, and the remains of a pyramid completely overgrown by the jungle. Their findings were published in 1926–1927 as a two-volume set titled Tribes and Temples.

![]()

The three most important Olmec sites that have been excavated so far are San Lorenzo, Tres Zapotes, and La Venta. In almost every instance, the first archaeologists, and sometimes the later ones retracing their steps, were led to the sites by locals who had uncovered the stone heads, altars, and other remains while farming.

Tres Zapotes was the first of these to be professionally excavated, by a small team led by the Stirlings and including an archaeologist named Philip Drucker, from 1938 to 1940. They re-excavated and thoroughly documented the original Olmec head that had been found by the farmworker some eighty years earlier. It turned out that the head stands nearly five feet high and weighs approximately eight tons. They also found several other carved stone stelae and monuments, including one (Stela C) that had a date inscribed upon it, just like the Maya stelae at various sites like Copan and Palenque, which used a similar dating system. Stirling was able to quickly determine that the date on Stela C was the equivalent of our 31 BCE.

Olmec colossal stone head, San Lorenzo

In 1940, during their second season of excavating at Tres Zapotes, the Stirlings went to visit the second Olmec site, La Venta, which they knew from the published volumes of Blom and La Forge. They were looking for the eight monuments that the two earlier archaeologists had been shown by the locals and had documented in a single day, back in 1925. They found them, including the colossal head, which turned out to be eight and a half feet high and twenty-two feet in circumference, plus two stelae, and three “altar-thrones,” which generally have a carving of a seated person inside a niche on the front of the altar.

The Stirlings found other remains that the previous explorers had not discovered, including three more huge stone heads and another altar-throne on which the seated man holds a baby on his lap. There are also four more pairs of adults and babies on the same monument, which is why it is usually called the “Quintuplet Altar,” although its official name is simply Altar 5.

As a result of all these discoveries during what had simply been a visit to the site, the Stirlings and Drucker decided to return and conduct excavations at La Venta, in 1942–1943. Although World War II was raging at the time, they managed to fit in two short field seasons, during which time they excavated the mounds that could be seen at the site. Some mounds contained tombs with a few grave goods; others were covering mosaic pavements. Subsequent excavations by other scholars have yielded much additional material; La Venta has at least thirty earthen mounds that date between 1000 and 400 BCE, and archaeologist Richard Diehl estimates that approximately ninety stone monuments have now been found at the site.

In 1945, the Stirlings went to visit San Lorenzo, in southern Veracruz. There the locals immediately showed them two colossal stone heads. One was nearly nine feet tall; the other was even taller—9.4 feet tall. Each weighs approximately forty tons. Both were larger than any the Stirlings had seen or found previously at either Tres Zapotes or La Venta. They also saw about a dozen other stone monuments, all now identified as Olmec. In addition, they were shown two stone jaguars at the nearby village of Tenochtitlán (not to be confused with the larger city underneath Mexico City that we will discuss in a moment). Archaeologists frequently tie these neighboring sites together, referring to them collectively as San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán.

A subsequent field season in 1946 by Stirling and Drucker yielded a few more stone sculptures, but nothing extraordinary, and they never fully published their results. It was left to Michael Coe, of Yale University, to return to San Lorenzo in the mid-1960s and restart the excavations, which were then published. The most recent expedition, led by Ann Cyphers of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, worked at the site from 1990 to 2012.

As a result of his work at the three sites, Matthew Stirling proposed that the Olmec civilization was older than that of the Maya, which initially met with fierce resistance from some of the old-school Mayanists, such as Eric Thompson. After all the debate, however, and with the introduction of radiocarbon dating, it was finally accepted that Stirling was correct and the Olmecs have now been placed in their proper and rightful position among the Mesoamerican civilizations, although there is still much work to be done in elucidating the details.

![]()

In contrast, the discoveries that have been made in downtown Mexico City date to the much later period of the Aztecs. These have revealed previously unknown remains of Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital city. The Aztecs were composed of a number of groups. Those who settled at Tenochtitlán called themselves the Mexica [meh-SHEE-ka]. The city flourished from about 1325 CE until its destruction by the Spanish conquistadors in 1521. Of course, it’s always been known that the Aztec capital lies underneath Mexico City, because the Spaniards destroyed much of it before building their own city right on top of the ruins.

Fortunately, the conquistadors created maps, including one supposedly drawn by Hernán Cortés himself, that show what the city looked like before its destruction. As a result, we know that it was originally built on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco, with causeways connecting it to the mainland. The space available for living was expanded by creating chinampas, or floating gardens, which eventually became firmly enough anchored and covered with enough soil that houses and other structures could be built upon them. It looks like the city was then split into four quarters and may have housed as many as two hundred fifty thousand people.

Because the modern city covers the ancient one, buildings and artifacts are constantly being discovered during various construction projects. For example, the great Calendar Stone, often called the Sun Stone, was discovered in December 1790, when the Mexico City Cathedral was being repaired. This huge stone is almost twelve feet across and weighs about twenty-four tons. It’s not quite clear what it was used for, though it may have been a ceremonial basin or altar. On it are depictions of the four periods that the Aztecs thought preceded their own time, lasting a total of 2,028 years. The face in the middle might be the Aztec deity of the Sun, which is why some people call it the Sun Stone.

The great stone was probably originally located on or in the Great Temple, usually called the Templo Mayor. Portions of the Templo Mayor itself were originally found in the mid-1900s, with more accidentally discovered in 1978 when electric cables were being laid in the area. As British archaeologist Paul Bahn notes, the excavation project that was subsequently undertaken was mammoth—several entire city blocks of houses and shops were torn down in the very center of the city so that the archaeologists could investigate the remains. An archaeologist with the wonderfully appropriate name of Eduardo Matos Moctezuma led the team.

The Templo Mayor is actually a double pyramid dedicated to two gods: Huitzilopochtli, god of the sun as well as war and human sacrifice, and Tlaloc, who is the rain and water god. In addition to the remains of the temple pyramid, the archaeologists found artifacts of gold and jade and many animal skeletons, and a rack of human skulls carved in stone. They also found that the Aztecs had buried objects from previous Mesoamerican civilizations.

In 2006 archaeologists found a stone altar depicting Tlaloc that dates to about 1450 CE. They also uncovered a monolith—a stone slab—made of pinkish andesite. The monolith depicts the earth goddess Tlaltecuhtli, originally painted with ocher, red, blue, white, and black. It was found lying flat, but would have stood eleven feet tall when vertical. It weighs twelve tons and dates to the last Aztec period, 1487–1520. The team that discovered the monolith thought that it might still be in its original position, perhaps at the entrance to a chamber or even a tomb, even though it had broken into four large pieces.

Aztec Moon Goddess, Tenochtitlán

Two years later, in a stone-lined shaft lying right beside the monolith, the archaeologists began finding additional Aztec religious offerings, including sacrificial knives made of white flint; objects made of jaguar bone; and bars of copal, or incense. Beneath the offerings, in a stone box, were the skeletons of two golden eagles, surrounded by twenty-seven sacrificial knives, most of which were dressed up in costumes as if they were gods and goddesses. And beneath these were yet more offerings; by January 2009, the archaeologists had found six separate sets of offerings in this one deep pit, which reached twenty-four feet below street level.

Back up at the eight-foot-deep mark, the archaeologists had found a second stone box. It contained the skeleton of a dog or a wolf that had been buried with a collar made from jade beads. It also had turquoise plugs—like earrings—in its ears and bracelets with little gold bells around its ankles. The archaeologists promptly nicknamed it Aristo-Canine.

The skeleton is covered with seashells and other remains of marine life, like clams and crabs. The lead excavator of the dig, Leonardo López Luján, thinks that the six sets of offerings mark the Aztec cosmology or belief system—for example, the dog/wolf with the seashells would represent the first level of the underworld, “serving to guide its master’s soul across a dangerous river,” as Robert Draper wrote in the 2010 National Geographic story that documented this amazing find. López Luján believes that he may be close to finding the tomb of one of the last, and most feared, Aztec emperors, Ahuitzotl (ah-WEE-tzohtl), who died in 1502 or 1503.

![]()

Travel about fifty kilometers northeast of Tenochtitlán and we reach Teotihuacán. The site predates Aztec civilization, although the Aztecs gave the city its name, which may mean “the birthplace of the gods.” It was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987 and is now one of the most visited tourist sites in Mexico. It’s still a matter of debate who lived there and what they called their city. It was inhabited from about 100 BCE to about 650 CE, as noted above, and probably had a population of up to one hundred fifty thousand people when it was at its largest. In an interview published in October 2015, Professor David Carrasco of Harvard University described it as “the imperial Rome of Mesoamerica.” By this, Carrasco means that Teotihuacán influenced hundreds of other Mesoamerican communities during its period of greatness and served as a beacon for later civilizations. Extensive evidence of Teotihuacano presence is seen in the Maya regions of southern Mexico and Guatemala hundreds of miles to the south, with many scholars believing that Teotihuacán controlled this region for several centuries.

It used to be thought that the Toltecs built the site, because that’s apparently what the later Aztecs told the Spaniards when they arrived, but that doesn’t seem to have been factually accurate, because the site is earlier than the time of the Toltecs, who flourished during the tenth through twelfth centuries CE. For the moment, the inhabitants are simply referred to as Teotihuacanos.

A long central avenue dominates the site. Called the Avenue of the Dead, it runs for about a mile and a half. Along it, pyramids and temples were built. These include the Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid of the Moon, as well as the Temple of the Feathered Serpent.

The Pyramid of the Sun is the largest of the buildings—more than seven hundred feet wide at the base and more than two hundred feet tall—and has a ceremonial cave right under the pyramid, which was discovered in 1971. The Pyramid of the Moon is not far behind in size; human remains were found there in the renewed excavations that began in 1998, which revealed a burial chamber with rich grave goods, including pyrite mirrors and obsidian blades.

The Temple of the Feathered Serpent is the third-largest building at the site. It gets its name from the heads of the feathered serpents that stick out from the façade of the building, each weighing up to four tons. The building itself probably dates to about 200 CE. Beginning in the 1980s, a series of pits was found in front of the temple, which contained the bodies of nearly two hundred warriors, both male and female, and their attendants. All of them had their hands tied behind their backs and were obviously ceremonial victims, perhaps sacrificed at the time that the building was dedicated or during ceremonies held on various occasions.

It was here that the secret tunnel was detected in 2003, leading from one of the plazas near the edge of the city to the Temple of the Feathered Serpent. As mentioned, investigation of this tunnel continues today; some have suggested that it may lead to a royal tomb, perhaps holding the bodies of the earliest rulers of the city.

Extensive survey work also has been done at the site and surrounding region. Headed by René Millon, the Teotihuacán Mapping Project documented the presence of huge industrial and domestic areas, conscious city planning, and ethnic communities from different parts of Mexico. The maps and other data produced by this project by 1973 provided archaeologists with a broader picture of the city’s size, scope, and wealth, beyond just describing the pyramids and other major buildings.

![]()

It is not clear why, but Teotihuacán was eventually abandoned, probably sometime in the seventh or eighth century CE. Even so, its location was never forgotten, even after it had been lying in ruins for centuries. We know, for example, that the Aztecs used to come to Teotihuacán and were well aware of the people who had once lived there.

Of course, even these Teotihuacanos are not the oldest inhabitants of the region that we now call Mexico. As we have seen, that designation goes to the Olmecs, who built sites such as San Lorenzo, La Venta, and Tres Zapotes, not to mention the Zapotecs in Oaxaca, who inhabited places like Monte Albán from about 400 BCE to 700 CE. We also mustn’t forget the Maya, whom we have discussed in another chapter and who should be placed between the Olmecs and the Aztecs. This region has a rich history, which is only just now beginning to be fully understood and further explored.