![]()

PYRAMIDS, MUMMIES, AND HIEROGLYPHICS. EGYPTOLOGY seems to be the field of archaeology that is most fascinating to the general public. It also is perhaps the most misunderstood. Everyone, from kindergarteners to grandparents, seems to be enthralled by the ancient Egyptians and knows a little something about them. Or do they? The amount of misinformation about ancient Egypt that is floating around, especially on the Internet, is astounding.

Every year Egyptologists and other archaeologists have to correct misunderstandings—“no, Hebrew slaves did not build the pyramids”—and every year their email accounts are inundated with questions after the airing of any one of the numerous television shows that claim that the pyramids were built by aliens or that they were built to store grain or that the Sphinx is ten thousand years old, or some other nonsense usually dreamed up by amateur enthusiasts. Therefore, in this chapter, we will touch upon aspects of these three topics—pyramids, mummies, and hieroglyphics—so that readers will be in a better position to sift through the often-dubious claims made about these topics.

![]()

The first archaeologists who worked in Egypt often weren’t really Egyptologists, or at least didn’t originally intend to be. Take The Great Belzoni, for example—Giovanni Battista Belzoni, who was born in 1778. He was a strong man in a circus, standing six feet, six inches tall and able to lift twelve men at a time, but he also could be considered an engineer of sorts. He first traveled to Egypt in 1815 to show the Ottoman ruler a new plan for drawing water out of the Nile and ended up becoming one of the first Egyptologists. We should use that term loosely, however, for Belzoni is remembered more for tomb robbing and mummy collecting than he is for any actual science or archaeology, though he was one of the first to explore Ramses II’s temple at Abu Simbel.

Karl Lepsius and Auguste Mariette, on the other hand, can rightly be considered giants in Egyptology, even if they were shorter than Belzoni. Lepsius was a Prussian Egyptologist who led an expedition to Egypt in 1842. The mission of the expedition was to record as many monuments as possible, which was done astonishingly well. The resulting twelve huge volumes of drawings and illustrations were published in German over a ten-year period from 1849 to 1859, as Monuments of Egypt and Ethiopia. The volumes of written material that accompanied them took another forty years or more to be published and didn’t see the light of day until more than a decade after Lepsius himself had died. Taken as a whole, the volumes of texts and plates are considered by many to be the foundations of modern Egyptology.

Auguste Mariette, who was born in France in 1821, started digging in Egypt on behalf of the Louvre in about 1850. Eight years later, he was appointed the first director of antiquities in Egypt. Among other things, he built the first national museum, whose collection still forms the basis of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo today.

Lepsius and Mariette were able to establish their careers in part because of an event that had taken place by 1823, when Mariette was only two years old and Lepsius was thirteen years old. It is one of the most famous events in Egyptology—the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphics.

In order to understand how the event took place, we must first go back to 1799 CE, a year or so after Napoleon and his troops invaded Egypt as part of a grand campaign to capture the Middle East. Napoleon had brought along more than one hundred fifty civilians as part of this campaign. Collectively known as the savants, they included scientists, engineers, and other scholars. They were charged with studying and recording the entire country, including the antiquities and monuments. Some today regard their work as really beginning the study of ancient Egypt, setting the stage immediately before Lepsius and Mariette. They also unintentionally set off a frenzy of Egyptomania in Europe, which continues today, as it does in the United States—the Luxor Hotel in Las Vegas being an obvious example.

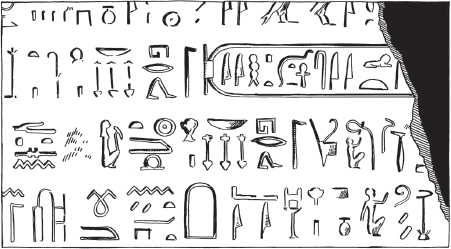

In any event, the French troops were in the village of Rosetta, in the Delta region, either rebuilding a fort or digging a foxhole—the stories differ. But in the process, they found an inscription that turned out to date from 196 BCE. It had been written to honor Ptolemy V—an Egyptian pharaoh who otherwise is not very memorable. It’s extremely important because the text of the inscription is written in three different scripts. At the top of this Rosetta stone, the text is written in Egyptian hieroglyphics. In the middle, the same text is written again, but this time in what is called demotic—essentially Egyptian cursive handwriting. And the bottom third of the stone has the inscription written once again, but this time in Greek.

Using this trilingual inscription, a brilliant French scholar named Jean-François Champollion was able to crack the code of Egyptian hieroglyphics. He did it in part by reading the Greek version, well understood by all scholars of his day, and realizing that two royal names appeared again and again: Ptolemy and Cleopatra. He looked for repetition in the Egyptian hieroglyphics that could represent those two names and was eventually able to use them as keys to his decipherment. Champollion wasn’t the only scholar working on this; a British linguist named Thomas Young very nearly beat Champollion to the translation. But it’s Champollion who got the credit for doing so in 1823, a mere twenty-four years after the inscription had been found.

It suddenly became clear that all of the “pretty pictures” painted on the walls of the tombs of nobles and inscribed elsewhere were in fact long inscriptions containing their biographies, lifetime achievements, and so on. One set of hieroglyphs that appeared frequently in these contexts is now known to be the symbols for eternity, which makes sense in a tomb setting.

It also turned out that the seven or eight hundred hieroglyphic signs could be read in various directions, but they are always consistent, because the figures always face toward the beginning of the line. The signs also could be read in various ways. For instance, a hieroglyph could be a word-sign and stand for the item being pictured, such as a bird or a bull; or it could stand for a single sound, like of the first letter of the word for the object; or it could be a syllabic sign representing a combination of consonants; or it could be used as a determinative to specify how to read the word next to it. It’s no wonder that not many people knew how to read and write in ancient Egypt—probably only about 1 percent of the population. Scribes had a respected position at the royal court, for it is quite possible that even the king and queen did not know how to read or write.

Although many of the inscriptions that we have today have survived because they are carved into stone, such as on the walls of temples and other buildings, the Egyptians more often wrote on sheets of papyrus, flattened reeds that grew along the Nile River, which was their version of paper. Though not as durable as stone inscriptions, thousands of papyrus scrolls have been preserved as a result of Egypt’s dry climate.

They used ink created from carbon and other materials. The ink could be black or it could be red, often with both colors used in the same manuscript. In those cases, the word written in red might be the first word of the new sentence, so that it was clear where one sentence ended and another one began, since there was no punctuation as we know it. Red ink also could mark the beginning of a spell, or even just a title or a heading, as determined by the context and the need.

![]()

Once Egyptian writing had been deciphered, it became possible for scholars to read the various records left on both stone and papyrus and begin reconstructing the history of ancient Egypt with confidence. In this they were both helped and hindered by the writings left by historians, travelers, and priests from the Greek and Roman periods. One was Herodotus, the Greek historian who lived in the fifth century BCE and reported on his travels in Egypt, including details—many of them highly inaccurate—about how the pyramids were built and bodies were mummified. Another was Manetho, a priest who lived in Hellenistic Egypt during the third century BCE and who attempted to construct a list of the rulers of Egypt from earliest times until his own period.

Manetho divided the history of Egypt into periods, a system that we still use today. Although he mangled many of the pharaohs’ names and got some things out of order, on the whole he was reasonably accurate, especially considering that he created this list almost twenty-five hundred years after the foundation of Egypt’s First Dynasty. So we say that the Old Kingdom Period began in about 2700 BCE, at the time of the Third Dynasty. The kingdom is known especially for the construction of the pyramids for the pharaohs of the Fourth Dynasty, from about 2600–2500 BCE.

The Old Kingdom lasted for about five hundred years, until approximately 2200 BCE, at which point it collapsed following the ninety-one-year-long reign of Pepi II. The collapse may not have been caused by the long rule of this pharaoh, who came to the throne when he was six years old, for recent studies now suggest that it may have been caused by climate change, in the form of droughts and famine that seem to have devastated both Egypt and much of the ancient Middle East at that time.

A period of anarchy called the First Intermediate Period followed the collapse of the Old Kingdom, with several dynasties vying for control of the whole country and none succeeding. The Middle Kingdom then lasted until about 1720 BCE, at which time Egypt was invaded and taken over by the Hyksos, who came down from the region of Canaan to the north and ruled over Egypt until they were expelled about 1550 BCE by Egyptian forces fighting under the leadership of two brothers, Kamose and Ahmose.

Strangely enough, even though they were brothers, Kamose is considered to be the last king of the Seventeenth Dynasty, while Ahmose is the first king of the Eighteenth Dynasty, which began a new era in Egypt known as the New Kingdom Period. It is this period that lasted until just after 1200 BCE and included rulers such as the powerful queen Hatshepsut; the militarily aggressive Thutmose III; the monotheist pharaoh Akhenaton; and the boy-king Tutankhamen; as well as ten pharaohs named Ramses. Even though Egypt survived the great collapse of the entire Bronze Age world in the years surrounding 1177 BCE and continued during the Third Intermediate Period, the Saite Renaissance, and then Greek and Roman rule, including by Alexander the Great and later Cleopatra, all dating to the first millennium BCE, it never again reached the heights of power that it had enjoyed during this New Kingdom Period.

![]()

With the translation of hieroglyphics in the early nineteenth century, scholars were able to begin reading and studying the other writings left to us by the ancient Egyptians. These range from poems and stories to economic accounts and religious texts. One thing that we frequently find written on papyrus, but also on the walls of the tombs of wealthy people, is the Book of the Dead, otherwise known as the Book of Going Forth by Day. This was essentially a manual to help the deceased person get into the afterlife right after he or she had died, because it contained the answers to the questions that would be asked before one was allowed to enter the afterworld—it was, essentially, a cheat sheet. This went hand in hand with the weighing of the heart ceremony, at which the dead person’s heart was placed on one scale and a feather representing truth and justice (ma’at) was placed on the other, to see whether the deceased had lived a good and just life. The dead person was allowed entrance to the afterlife only if the heart weighed the same or less than the feather—that is, if it was not heavy with sins and wrongdoing.

In order to stay in the afterworld, the physical body of the dead person had to remain intact, even long after the person had died. This is where the process of mummification enters the picture. Some of the earliest mummies that we have from Egypt seem to have been mummified naturally, but this was obviously not always the case. There also was the problem of making certain that a body remained buried long after its original internment and that jackals, hyenas, or other scavengers didn’t maul it later.

Two things developed, therefore. One was the process of mummification. The other was the creation of mastabas, or benches, of mudbrick that were used to protect the burial place. Many scholars suspect that these were the predecessors of the pyramids. Let’s look at the two processes one at a time.

First, mummification. Even today, many people try their hand at mummifying things, frequently as a school project in elementary school. This usually involves chickens, rather than a person or a family pet, which is fortunate (unless, of course, the family pet happens to be a chicken).

We know quite a bit about mummification, in part because we have a rather detailed description from Herodotus, who learned about the process during his time in Egypt. He wrote that one should put the body into a type of desiccating salt called natron and then leave it there for seventy days. The natron wicks the moisture out of the body and helps to mummify it. This obviously does not happen overnight, hence the need for a seventy-day-long bath in natron.

But a number of the inner organs also need to be removed. To do this, the mummifier is told to make a slit up the side of the body and reach in to remove the stomach, upper intestines, lower intestines, lungs, and the liver. These are all placed in what we call canopic jars. That’s the modern name for them, since they were first identified by early Egyptologists who thought they were associated with the Greek myth of Canopus, a Mycenaean warrior from Greece who fought in the Trojan War but was bitten by a snake and died while visiting Egypt.

Canopic jars were essential equipment for the tomb. Each set could be different, but during the New Kingdom, the lids of the jars depicted the four sons of Horus, who guarded the organs. The stomach and upper intestines would go into a jar that had a jackal head for a lid. The lower intestines were placed in one that had a falcon head for a lid. The lungs would go into a baboon-headed jar, and the liver would go into a jar with a lid shaped like a human head. Then, sweet-smelling herbs and spices would be stuffed into the body cavity where the organs had been and the slit in the side of the body would be sewn up again.

The heart, however, would be left in place within the body, for the ancient Egyptians thought it was the center of intelligence and would be needed in the afterlife. The brain, on the other hand, was not understood and was simply discarded. There were two ways to get it out.

One way to remove the brain was simply to take a long piece of wire, with the end bent into a hook shape. This was shoved up the dead person’s nose until the bent end was up in the brain cavity, then it was quickly pulled out, bringing the brain with it. If not all the brain came out the first time, the process was repeated until it was completely removed.

The other way to do it was to tilt the person’s head back and put drops into their nose. The drops were made of a powerful acid, so when they ran up into the brain cavity, they melted the brain. When the head was tilted back down, the gray gooey mass would simply run out the person’s nose, and voilà—the brain cavity was now empty.

The precise method that the Egyptians used is still debated, even in scientific articles, but it all goes back to Herodotus, who was the first one to tell us that the embalmers pulled most of the brain out through the nostrils using a crooked piece of iron and then cleared out the rest “by rinsing with drugs.” In 2012 an object identified as a “brain-removal tool” was found in the skull of a twenty-five-hundred-year-old mummy. It was probably used for both liquefying and removing the brain, or so researchers think.

The embalming was done out of sight of family members, which was probably a good idea, since accidents sometimes did happen. Take, for example, one woman whose cheeks had sunken because of the embalming process. She was a priestess named Henttawy from the Twenty-First Dynasty, and so she lived and died sometime in the tenth century BCE, or about three thousand years ago. The embalmers had stuffed her cheeks with cotton pads, perhaps in an effort to make her appear more lifelike, which seems to have been the custom at the time. But they put in too much and at some point both her cheeks simply ripped off. Of course, she didn’t get to stay in the afterlife because her body had not remained intact, but nobody knew that until the mummy was unwrapped in modern times.

Other mummies in the British Museum, and in museums elsewhere in Britain, Germany, and Egypt, have been recently re-examined, using new computerized tomography (CT) scanning and three-dimensional visualization, with a number of interesting things found. The mummies, including both royals and commoners, are from a variety of periods, from 3500 BCE to 700 CE, and are of different ages, from children to adults. Some of them had tattoos, others suffered from various ailments, and almost all of them had dental problems. One investigation, of a female singer named Tamut from Thebes, who was mummified in about 900 BCE, revealed that protective amulets had been hidden inside the wrappings and that she had calcified plaque in her arteries, which may have led to her death from a heart attack or a stroke. Other investigations, of animal mummies, revealed that up to a third of them had little or no actual remains inside the wrappings, leading to speculation about why this might be.

Mummifying the body was one thing that the ancient Egyptians did, but they also had to protect the mummy from the elements. That’s why, before about 3000 BCE, we find mastabas, or low benches made out of mudbricks, above the grave into which the mummy was placed. Mastaba means “bench” in modern Arabic; hence the name given to them today. That way, even if a sandstorm hit the cemetery and all of the sand was swept away, the mastaba would remain in place and the mummy would not be exposed to the elements . . . or to the pecking beak of a bird or the jaws of a hyena or some other scavenger.

This may have been what eventually led to the pyramids, several centuries later. It is not clear exactly what triggered the idea of building the first pyramids, but it is unlikely to have had anything to do with ancient aliens. It seems to have been Djoser (or Zozer), a pharaoh who lived during the Third Dynasty, in the years just after 2700 BCE, who was first responsible for asking Imhotep, his vizier (in other words, his right-hand man) to create something a bit more majestic as his burial place. And thus, the Step Pyramid was constructed, which we identify as the first pyramid ever to be built in Egypt. Imhotep seems to have been Djoser’s personal physician as well as his architect; he was later hailed as the Father of Egyptian medicine and then eventually deified as a god of healing and, as such, was even later linked to the Greek god Asclepius.

Looking at the Step Pyramid, it appears that Imhotep simply took about six mastabas and placed them one on top of the other, decreasing in size as they got closer to the top, so that he ended up with a pyramid built in stages or steps. It was just a short hop from that Step Pyramid to the huge smooth-sided pyramids that we know from outside of Cairo today, because all that needed to be done was to fill in the missing parts and smooth out the sides.

Step Pyramid of Djoser, Saqqara

There is a lot more to it than that, of course, and it is still very much a matter of debate how exactly the pharaohs built the pyramids. Many scholars personally favor the idea of using blocks and tackles and pulleys, just as is done when hoisting up heavy stones today, but others like the idea of pulling the blocks up into place via earthen ramps that ran in a spiral around the pyramid. If that method were used, the last thing to do after putting the final blocks into place at the top would be to dismantle the earthen ramps that would have been surrounding the pyramid at that point. There are all sorts of other hypotheses, including the suggestion that there was an internal ramp built within the pyramid that was used and that can’t be seen anymore. It is clear from replication studies conducted in recent years that, although the blocks were many and heavy, they were not beyond the technological skill of the Egyptians. There is no need to invoke alien powers.

The other thing to keep in mind, though, is that such big pyramids were not built in isolation; they were normally part of a much larger funerary complex, which also contained ceremonial courts, religious shrines, and other buildings, all dedicated to keeping the king’s memory alive. So, there is a funerary complex for Djoser, of which the Step Pyramid is just one part.

The same is true at Giza, outside modern-day Cairo, where the three greatest Egyptian pyramids were built. This is the only one from the original list of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World that still survives today. They are also one of the few cultural features on Earth that can be seen relatively easily from the International Space Station.

These three pyramids date to the Fourth Dynasty, the so-called Pyramid Age, during the Old Kingdom Period. They were built one after another, by a father-son-grandson combination named Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure, or—as the later Greeks called them—Cheops, Chephren, and Mycerinus. The first one, built by Khufu (aka Cheops) just after 2600 BCE, is the earliest and largest, so that it is known today as the Great Pyramid. We know that Khufu built this pyramid, in part because graffiti left by the workers inside mention his name. The second pyramid, the one built by Khafre (aka Chephren) is the one to which the Sphinx probably belongs, for the Sphinx sits at what was originally the entrance to the funerary complex for Khafre. The third one is also the smallest, built by Menkaure (aka Mycerinus). Going inside this pyramid is an extremely claustrophobic experience, as I can attest—I’m not the world’s biggest person, but even I had to bend my head in order not to hit the ceiling and my shoulders scraped the walls on either side as I walked the length of one of the internal corridors. Moreover, I can clearly remember the oppressive feeling of having tons and tons of rock above me.

The Great Pyramid is the most famous of the three. It probably took ten to twenty years to build, but it is unlikely that it was built by slaves (and it certainly wasn’t built by Hebrew slaves, as is sometimes said, because the pyramids were built at least eight hundred years before the date of the biblical story of Joseph that purportedly brought the Hebrews to Egypt).

Herodotus, the same Greek historian who described how to mummify bodies, says that it took one hundred thousand people working in four shifts per year to build such a pyramid. Excavations of the workers’ quarters and cemeteries in the vicinity of the pyramids since the 1990s have led to the general conclusion today that the workforce probably consisted of peasants, farmers, and other members of the lower classes who were working for pay during the off season, after the harvest had been brought in, and that they were well treated. In addition to this seasonal work force, there was a permanent contingent of several thousand professional pyramid builders who directed the work and provided the technical expertise. The pyramids were essentially giant public works projects, because building them would have pumped an incredible amount of money back into the economy from royal coffers.

It is clear that a huge workforce was needed, though, because the number of stone blocks used in each pyramid was tremendous. For example, the Great Pyramid was originally probably about 480 feet tall and about 755 feet on each side. There are 2.3 million blocks in the Great Pyramid, some of them weighing several tons. The whole pyramid is estimated to weigh almost six million tons. Originally it would have been finished off with an outer casing of white limestone, but those limestone blocks are long gone, with many of them reused in later buildings both in Cairo itself and in the villages surrounding the pyramids.

Within the Great Pyramid are a series of passageways and chambers. These are still much debated, but it seems that the original entrance and passageway led down to a chamber where the king would have been buried beneath the ground level. It is possible that the plan was changed, however, for another passageway leads upward, to what is called the Grand Gallery and then to the King’s Chamber, in which a large granite sarcophagus is still in place.

There are also two narrow shafts leading up from the King’s Chamber to either side of the pyramid. These used to be, and sometimes still are, referred to as air shafts, though now some attribute a more ritualistic purpose to them. They have been put to good use in recent years, when it was noticed that the crush of tourists inside the pyramid was creating problems, namely from the moisture in their exhaled breath. Air conditioners (or extractor fans) were placed in the shafts to pull the moist air out and pull in the dry desert air, thereby solving the problem almost immediately. So, if you’re in the Great Pyramid and think that you hear the hum of air conditioners, it’s not your imagination.

As for the Sphinx, it stands at the entrance to the second pyramid, the one built by Khafre, and Egyptologists have noted the resemblance of its face to statues of Khafre. It’s not ten thousand years old, as some amateur enthusiasts have claimed, but rather dates to about 2550 BCE. It sits in one of the quarries from which the Egyptians got the blocks for the pyramids, but it was left because the core of the body was “rotten”—that is, the stone wasn’t good enough to be used as building material. So the core was shaped to look like a body and then blocks were added to form the paws as well as the head and face.

It had already been excavated once in antiquity, for the pharaoh Thutmose IV left an inscription claiming that—when he was still a young prince—he had fallen asleep in the shadow of the Sphinx, which was buried up to its neck in sand. This would have been about 1400 BCE. In a dream, the Sphinx told him that if he removed the sand, the Sphinx would make him king over Egypt. He excavated the sand away and fixed the blocks where they were crumbling. When he eventually became king, he left what is now known as the Sphinx Dream Stele between its paws, where modern Egyptologists found it.

Legend has it that the nose of the Sphinx is gone because Napoleon’s troops shot it off in 1798 or 1799. That’s simply not true. Although his troops did use the Sphinx for target practice, the nose was already long gone by that point. According to the Arab historian al-Maqrizi, who was writing in the fifteenth century, a Sufi Muslim ruler hacked off the nose in 1378 because the Egyptian peasants were making offerings to the Sphinx and treating it as a pagan idol.

![]()

These days, new technologies are being put to use in Egypt to investigate some of the most famous architectural features, including King Tut’s tomb and a number of pyramids, from the Bent Pyramid and the Red Pyramid at Dashur to the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza.

For instance, in 2015 Egyptian, Japanese, Canadian, and French scientists used infrared thermography to determine that there were some strange anomalies in several of the pyramids, including differences in temperature between different blocks of stone. The thermal data might indicate the presence of cavities or some sort of internal structure that had not been noted previously.

The scientists are also using muon radiography that might provide additional data about such possible cavities. Muon collectors, or detectors, measure cosmic particles that can pass through solid structures but also can indicate where there are hollows or voids within them. They have also been used previously at a Maya pyramid in Belize in 2013. In late 2015 forty muon detector plates, covering ten square feet, were placed in the lower chamber of the Bent Pyramid at Dashur in Egypt, built a century before the well-known Giza pyramids, and left for forty days. The results, reported in April 2016, were promising, clearly showing the known second chamber within the pyramid and ruling out the possibility of any other undiscovered chambers within the field of view that was covered by the detectors. Next up for investigation is the Great Pyramid. All this means that the pyramids, which have been there since the beginnings of archaeology and Egyptology, are once again coming to the forefront of exploration in the field.

Overall, this excursion into the world of ancient Egypt has attempted to shed some light on the remarkable achievements of this great civilization, as well as some of the recent discoveries that have been made and the new technologies that are now being used to make them. I hope that it will now be easier in the future for readers to judge some of the claims made about the ancient Egyptians—especially when it comes to the big three: pyramids, mummies, and hieroglyphics—whether online, on television, or by well-meaning friends and neighbors. But keep in mind that these popular topics are far from the only things that Egyptologists are working on; interesting papers presented by scholars at the ARCE (American Research Center in Egypt) annual meeting in 2016 included “Kingship during the Third Intermediate Period,” “New Kingdom Burial Practices on the Eastern Frontier at Tell el-Borg, Part II,” “The Mechanics of Egyptian Royal Rock Inscriptions,” and other topics that don’t always make it into the television specials.