![]()

HEINRICH SCHLIEMANN, THE “DISCOVERER” OF TROY, IS also frequently referred to as the father of Mycenaean archaeology. The reason is simple: after he excavated at the site of Hissarlik in Turkey from 1870 to 1873 and announced to the world that he had found Troy, he decided to go looking for the other side, namely Agamemnon, Menelaus, Odysseus, and the other Mycenaeans who had supposedly fought for ten years against the Trojans.

And so, Schliemann took a break from digging at Hissarlik and tried his hand at excavating Mycenae, the city in the Greek Peloponnese where it was said that Agamemnon, king among kings and leader of the Greek invading force at Troy, had once ruled. It was a lot easier to find Mycenae than it had been to find Troy, because the modern village still had the same name—Mykēnē in Greek—and the remains of the famous Lion Gate entrance to the ancient citadel were partially visible, sticking up out of the ground.

Schliemann thought he knew where to look for Agamemnon at the site. The ancient Greek sources, from Homer down to the later fifth century BCE plays written by Sophocles, Aeschylus, and Euripides, said that Agamemnon had been killed after he returned home from ten years of fighting at Troy. He was murdered by his wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus, reportedly at the dinner table during a feast, according to Homer (Odyssey IV.524–35), but perhaps while taking a bath, according to later accounts. The men that were with Agamemnon were killed as well.

A much-later visitor to the site named Pausanias, who wrote about his travels all over Greece during the Roman period in the second century CE, said that Agamemnon and his men were buried inside the city limits of Mycenae. Pausanias didn’t give a specific location for the graves, and so Schliemann had to use his powers of deduction.

![]()

In February 1874, working without a permit as usual, Schliemann did some exploratory work at the site. He dug, as he put it, “thirty-four shafts in different places, in order to sound the ground and to find out the place where I should have to dig for them.” In other words, he was digging test pits at the site—a technique that we have discussed earlier—in order to determine where he should concentrate his efforts once the real excavation started. Several of the test pits produced interesting results, but the most important were two that he dug not far inside the Lion Gate. Here, he says, he found “an unsculptured slab resembling a tombstone” in addition to other finds, including female idols and small figurines.

When he returned in early August 1876 with an initial team of sixty-three workers, he put two-thirds of them to work in an area that was just forty feet inside the Lion Gate. They were instructed to dig in a huge square area 113 feet long and 113 feet wide. Within two weeks, after he had doubled the number of workers to 125, they found a grave circle, with five deep shafts marked at their top by fragmentary tombstones depicting warriors and hunting scenes. This is now known as Grave Circle A.

The shafts that Schliemann found led to graves with multiple burials, an unbelievable number of swords, and a tremendous quantity of gold and silver objects, in addition to other grave goods. Among these were gold masks covering the faces of several of the dead men.

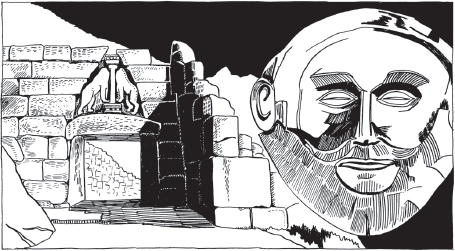

Lion Gate, Mycenae

According to the story that is now usually told, Schliemann was so certain that he had found whom he was looking for that he immediately sent a telegram to the king of Greece, George I, which read, “I have gazed upon the face of Agamemnon.” The king immediately rushed to Mycenae, where Schliemann showed him a marvelous gold mask with a kingly face engraved upon it, complete with mustache and beard. That mask now hangs front and center in a display case in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

The problem is, that wasn’t the mask at which Schliemann was gazing when he sent the telegram nor was that actually the message that he sent to the king. His telegram to the king was not quite as pithy or punchy, reading (according to one version), “With great joy I announce to Your Majesty that I have discovered the tombs which the tradition proclaimed by Pausanias indicates to be the graves of Agamemnon, Cassandra, Eury-medon and their companions.” Moreover, he had been looking at another mask at the time, of a much more cherubic and pleasant-looking fellow. When Schliemann found the more kingly-looking mask before the Greek monarch arrived, however, he showed him the new one instead. Such a move was fairly typical for Schliemann—remember that he had begun the excavations without a permit to do so. It was only in later telegrams, such as those to the minister of Germany and to members of the news media, that Schliemann began saying that he had gazed upon the face, or into the eyes, of Agamemnon.

The grave goods that Schliemann found in those tombs included marvelous pieces of work: bronze daggers inlaid with hunting and wildlife scenes in silver and gold on the blades; objects of rock crystal and semiprecious stones; and gold, gold, gold—something like eight hundred kilograms of gold objects all told.

Excavations by the Greek archaeologist Panayiotis Stamatakis just a year or so later turned up at least one more grave within Grave Circle A and now, especially with better techniques of dating available, it is considered extremely unlikely that these are the graves of Agamemnon and his men. Their deaths would have taken place sometime between 1250 and 1175 BCE, if they even ever existed rather than being the stuff of myth and legend. We now know that the pottery and other objects in the graves date from 1600–1500 BCE, which means they are from a period three or four hundred years earlier than the time of the Trojan War.

Schliemann probably suspected as much. In his 1880 book on Mycenae, published just a few years after the excavation, he says specifically that the fragmentary tombstones likely dated to the middle of the second millennium BCE, and he even gives them a date of 1500 BCE in the table of contents for chapter 4. And so, he was fairly close to being correct in terms of the date for the tombs and their contents, even if he was completely wrong about whose bodies they contained.

In fact, it is now thought that these are most likely the graves of one of the first dynasties to rule at Mycenae, since the city rose to prominence at about 1700 BCE. These rulers would have lived within a century or two of that rise and were buried outside the city wall. At some point near the end of the Late Bronze Age, however, probably about 1250 BCE, the fortifications of the city were rebuilt to enclose a larger area than previously, which is when the Lion Gate was constructed. It was at that time that Grave Circle A came to be inside the walls.

![]()

Just down the hill is Grave Circle B, which was found in the 1950s and is now adjacent to a parking lot for tourist buses and cars. Since the burials here date to 1650–1550 BCE, some of them are earlier than those in Grave Circle A. They may have been the very first kings, and perhaps a queen, to have ruled at Mycenae. In 1995, forensic anthropologists working with the skeletal material found in Grave Circle B attempted to reconstruct what some of the individuals would have originally looked like—it could have been an episode of CSI: Ancient Greece. They decided that the remains were from one woman and six men. Even though their end results are just a “best guess,” they succeeded in bringing the long-dead people more to life than the bare bones could ever do, for they reconstructed their faces, hair, and, in several cases, beards as well.

Elsewhere on the site are a few very large beehive-shaped tombs, built from huge blocks of stone, known as tholos tombs. Several of them have names given to them in relatively modern times, including the Tomb of Clytemnestra and the Tomb of Agamemnon (also called the Treasury of Atreus). These were built about 1250 BCE, so if Agamemnon is buried anywhere, it could have been in these. They were all found completely looted and empty, however.

![]()

Schliemann excavated at Mycenae only in 1874 and 1876. He then went looking for Ithaca, home of Odysseus, after which he returned to Troy for several more seasons of digging. In 1884 he dug at the site of Tiryns, which is only a few kilometers from Mycenae, but never excavated at Mycenae itself ever again. One hundred fifteen years later, Mycenae and Tiryns were jointly named to the UNESCO World Heritage Site list, in 1999.

It was left to later archaeologists to uncover the rest of the site, most of them using much better excavation methods than Schliemann had. The site has been under almost continuous excavation since Schliemann’s day, and some very well-known Greek, British, and US archaeologists have spent many seasons there, including George Mylonas, Alan Wace, Elizabeth French, and my own professor, Spyros Iakovides.

Because of their efforts, what was left of the palace at the very top of the citadel has now been completely excavated. It turns out that its interior, and possibly the exterior as well, was covered with brightly colored plaster, with scenes of hunting and other activities garishly painted in blues, yellows, reds, and other colors on the walls. The king would have sat at one side of a large room, surrounded by such painted scenes, while a large fire blazed in a hearth that was set in the middle of the floor. It was dark in there, and smoky, and probably damp as well. Mycenaean palaces seem to have been a bit claustrophobic, with few windows or other openings; they focused inward rather than looking outward.

The rooms around the palace were used for a multitude of things, ranging from what were probably residential quarters for the royal family to workrooms for the craftsmen. There appears to have been a cult center, possibly where religious rituals took place. Some strange idols and figurines have been found there, along with wall paintings.

Texts inscribed on clay tablets also have been found at various places in and around the palace, as they have at other Mycenaean palatial sites. They are written in Linear B, which was deciphered and translated in 1952 by Michael Ventris, an English architect, who proved that it was an early version of Greek. Most of the tablets are simply inventories of goods that were being brought to the palace or sent out from there, but they do include some of the names of their gods, who will be quite familiar to readers, including Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Artemis, and Dionysus.

There is no doubt that Mycenae was a wealthy city, with international connections. Objects imported from Italy, Egypt, Canaan, Cyprus, Anatolia, and even as far away as Mesopotamia have been found. Some of the most interesting are fragments of Egyptian faience plaques with the name of Pharaoh Amenhotep III on them, which might have been left by an official Egyptian embassy that was sent to Mycenae in the middle of the fourteenth century BCE.

Late in the Bronze Age, possibly about 1250 BCE at the same time as the Lion Gate, a well-constructed tunnel with steps of stone was built, leading down to a water source so that the inhabitants didn’t have to venture outside in times of siege. This may be an indication that they could see trouble brewing in the near future.

It is not clear why the city came to an end soon after 1200 BCE, but it did, in the general calamity that ended the whole of the Late Bronze Age in this region. Mycenae is built directly over a seismic fault line and at least one earthquake, if not more, caused destruction during this period. But it may have been drought and famine, followed perhaps by either internal revolt or external invasion that finally brought down this once-great city. There are some later remains, including a temple dedicated to Hera that was built at the very top of the citadel after the eighth century BCE, during the Archaic period, but Mycenae never regained its lost glory.

Other Mycenaean palaces at Tiryns, Thebes, Pylos, and elsewhere in Greece were destroyed or abandoned at the end of the Late Bronze Age as well. Much remains to be excavated at these and other sites, as shown by the recent discovery of the so-called Griffin Warrior grave at Pylos in 2015 by a team of University of Cincinnati archaeologists led by Jack Davis and Sharon Stocker. Dating to the fifteenth century BCE and located just next to the so-called Palace of Nestor at the site, the tomb contained more than fourteen hundred objects accompanying the single male skeleton—a man who was about thirty to thirty-five years old when he died. Preliminary announcements and media reports list some of the artifacts buried with him: gold rings, necklaces, and other jewelry; gold cups, silver cups, and bronze bowls; a bronze mirror, ivory combs, and carved seal stones; and a long bronze sword with an ivory hilt covered in gold leaf. Between his legs was an ivory plaque inscribed with a carved griffin on it, which has now given its name to the grave and its warrior. The grave was so packed with delicate artifacts that the archaeologists dug with wooden shish kebob sticks instead of metal dental tools, to be sure that no damage was done to them during excavation.

![]()

Partway across the Aegean Sea, on the island of Crete, Schliemann also tried to purchase land at a site that he thought might be the capital city of the legendary king Minos. The owner refused to sell it to him, and so it was left to another archaeologist two decades later, Arthur Evans, to excavate the site and bring the other great Bronze Age Aegean civilization, the Minoans, to light. The city that he excavated, beginning in 1900, is now known as Knossos.

Evans was a Victorian gentleman in every sense of the word. In one picture, Evans can be seen clad in a white linen suit and wearing a pith helmet, which is of course not at all the way that we dress when digging today. Born in 1851, he grew up in good circumstances in England, the son of John Evans, who was a respected scholar and a trustee of the British Museum, as well as president of the Society of Antiquaries, the Numismatic Society, the Geological Society of London, and other societies and institutes.

Evans had been searching for this city of Knossos for years, ever since he saw a few items for sale in the marketplace in Athens earlier in the decade. Known as milkstones and sold to pregnant women for help during and after giving birth, these small pieces of semiprecious stone had strange figures and engravings on them. Evans eventually traced them back to Crete, to Kephala Hill on the outskirts of the modern port city of Heraklion, the very land that Schliemann had tried unsuccessfully to buy. Evans had better luck, purchased the mound, and began excavating. Underneath the gentle hill covered by underbrush and trees, his team of workers quickly came across the ruins of what Evans identified as the palace that he was looking for. He spent the rest of his career, and virtually all his family fortune, digging at the site, publishing the results, and reconstructing the remains.

What Evans found at Knossos turned out to be a civilization that was a little older than the Mycenaeans and that had influenced them when they were “growing up.” For instance, a number of the objects that Schliemann found in the Shaft Graves at Mycenae were either of Minoan manufacture or bore the stamp of Minoan influence. In fact, Evans thought that the Minoans had conquered the Mycenaeans, though the opposite has turned out to be true.

When we refer to the Minoans, we’re using the name that Evans gave to this people, since we don’t know what they called themselves, nor do we know where they originally came from. They had flourished at the end of the third millennium BCE and then through most of the second millennium BCE—what we now call the Middle and Late Bronze Age in this region. Around 1700 BCE, a major earthquake hit Knossos, but the inhabitants survived and rebuilt the palace. Probably sometime about 1350 BCE, the Mycenaeans from the Greek mainland seem to have invaded and taken over, bringing with them a new way of writing, new types of scenes for the wall paintings, and a more militaristic way of life that lasted for about a century and a half, until everything collapsed soon after 1200 BCE.

Evans found amazing things at Knossos, but he also made what many consider to be a fatal error, because of the reconstructions that he created from the remains. For example, he imagined that the main part of the palace had three stories, which he inferred from the remains of staircases that he found, and so he reconstructed that part of the palace with three floors. Because he used cement and other permanent materials, it is nearly impossible to undo his reconstruction today. He may well have been correct in part, but not in everything, which is why today such reconstructions are generally not permitted, unless there is a very clear indication of what is original and what has been reconstructed.

What Evans and his team of workers found was a large, essentially open-air palace, with a huge central courtyard. It was light; it was airy; it was open to the elements; it was integrated into the environment. It even had running water and a sewer system. In other words, it was a building belonging to a culture that was very technologically advanced for its time. It served not only as headquarters for the ruler, but also as a center for redistribution. Locals would bring their goods in for storage, like wheat, barley, wine, and grapes, and then the palace would redistribute them as needed. There is, in fact, an entire part of the palace that consists only of corridors packed with large storage jars, including some that are sunk into the ground, in order to keep their contents cold.

Two things remain a mystery, however. One is the fact that there are absolutely no fortification walls around the palace at Knossos. Nor are there any at the other six or seven smaller palaces elsewhere on Crete at this time, despite occasional claims to the contrary. This is strange. Why weren’t the people on Crete afraid of being attacked?

Much later, the Greek historian Thucydides said that the Minoans had a thalassocracy—that is, they ruled the sea with their navy. But that explains only why they might not have been worried about invasions by outsiders. It doesn’t clarify why they weren’t worried about an attack from just down the road. There have been many ideas put forward, but none has been completely satisfactory. One hypothesis is that it was a single family that was ruling Crete at the time, with the father at Knossos, his sons living at other palaces like Phaistos and Kato Zakro, and cousins at still other palaces like Khania. It also has been suggested that perhaps women ruled Crete, as a matriarchy, and that their peaceful rule made fortifications unnecessary. Although this could certainly be true, it still doesn’t explain why there are no fortification walls; Zenobia of Palmya, Boudicca of Celtic England, Cleopatra of Egypt, and other female leaders throughout the centuries and elsewhere in the ancient world serve as proof that women are as capable as men of fighting or leading attacks on other cities and regions.

But that brings us to the second mystery, for we have no idea whether it was a king who ruled Knossos. It might have been a queen. It might have been a priest or a priestess. It might have been community rule. We just don’t know. The archaeological remains, the artifacts, and even the written texts found at the site are all ambiguous and do not yet allow us to answer the question of who ruled at Knossos. Evans did label one room the “king’s throne room” and another the “queen’s megaron,” but those are just names that he assigned. Someone was in charge, but we’re still not sure who it was.

Among the objects brought to light by Evans are two extremely well known figurines of women holding snakes. They are made out of faience and ivory, but they were very fragmentary when found and so were restored by skilled craftsmen hired by Evans. The larger one is frequently called the Snake Goddess and the smaller one the Snake Priestess, but the names also are often used interchangeably and it is not at all clear whether either of them really is a representation of a goddess or a priestess. There are now a number of such figurines in museums around the world. Unfortunately, only a few are likely to be genuine. The rest have been identified as forgeries, probably made by the very men who conserved and reconstructed the real ones for Evans.

The interior walls of the palace were ablaze with color, in the form of many wall paintings. Everywhere the inhabitants looked, there was another elaborate decoration. From these, we can tell a fair amount about the Minoans. For instance, there is one woman depicted who is so beautiful that Evans dubbed her La Parisienne. She is shown with an elaborate hairdo, makeup, jewelry, and a dress of red, white, and blue. Other frescoes show similarly dressed women. Men are pictured too, usually dressed only in a kilt; they too wear jewelry and possibly makeup as well.

There are a few frescoes, though, where the reconstructions of Evans and his team of restorers were downright wrong. One is the well-known Dolphin Fresco; another is the most famous painting at the site, the Priest-King Fresco.

In the Dolphin Fresco, Evans reconstructed a painting with five dolphins and a few flying fish on a wall in the area of the Queen’s Megaron. The painting wasn’t still on the wall, of course; Evans found the fragments lying in the dirt in front of the wall during his excavations. He only found fragments from two of the dolphins, but the area where he thought the painting had been was large enough that he needed to suggest that there had originally been five dolphins.

The philosophical principle of Occam’s razor—that the simplest solution is probably the correct one—comes into play here, though. If Evans found fragments from two dolphins, then he can only state for certain that there were two dolphins originally; everything else is a hypothesis. And since the painting could have come from anywhere in the room, or even from the one above it, we should look around for other possibilities. In 1986 Professor Robert Koehl of Hunter College suggested that the Dolphin Fresco, with only two dolphins, rather than five, was originally on the floor, not on the wall, for there is a space on the floor that is just a perfect size for the existing painting of the two dolphins—and both the Minoans and the Mycenaeans are known to have painted at least some of their floors. It is also conceivable that it was originally inlaid into the floor of a room located directly above the present one and it came crashing down after the palace was abandoned.

The other painting that Evans reconstructed incorrectly is the Priest-King Fresco, which today is reproduced everywhere, from the covers of books to placemats to plaster replicas. Here, Evans and his restorers put together a man whom they called the Priest-King of Knossos—though we should note that the title implies that they were unsure of who was ruling the city, just as we are still uncertain today. They have him walking toward the left side of the painting, with his head and his legs facing to the left, but with his body frontally facing the viewer and twisted toward the right. His right arm is cocked up against his chest, while his left arm goes off to the right, holding a rope (which they said was attached to a bull that isn’t shown).

So, what’s wrong with this? Well, just about everything. First, the pieces apparently were found in three different rooms in the building, not all together in one. Why Evans thought they were all from the same painting is beyond me. Second, the flesh of the figure is in two different colors; the head, which is facing left and has just a bit of skin visible, is painted white; the chest, which is twisted right, is reddish-brown; and the legs, which are headed to the left, are also reddish-brown. In Minoan art, they used conventions to depict males and females—males are always red or brown; females are white or yellow.

In other words, we have three different figures here, which Evans put together as a single person. We have a woman headed left, of whom we have only the top of her head; a man also headed left, from whom we have only part of his legs; and perhaps a young boy or teenager headed right, for whom we have only the torso, with the right hand cocked against the chest. Moreover, the pose of the torso looks very much like the pose adopted by two boxing boys in a painting found on Santorini. So much for the Priest-King of Knossos, but this serves as a good reminder that archaeology, and archaeological reconstructions, are always open to correction by later researchers.

![]()

Let’s now turn from Evans’s reconstructed frescoes and have a quick look at the big central court at Knossos. This was undoubtedly used for all sorts of things, as such big ceremonial areas are throughout the world and in all eras. But the court at Knossos seems to have been where a rather unusual practice took place, if we can believe what is pictured in a small wall painting in one of the buildings, where we see three people—one male and two female—leaping over a bull.

The man is in mid-flight, doing a somersault over the bull’s back. One woman is in front of the bull, grasping his horns, perhaps to distract him, while the other is behind the bull and looks poised to catch the man when he lands. It is also possible, however, that all three are leaping over the bull; if so, one woman has just landed, the man is in the process, and the other woman is about to fling herself over. It is unclear which interpretation is the correct one. Either way, this is like doing a routine on the pommel horse at the Olympics, except that the pommel horse is alive, has horns, and is trying to kill you.

Excavators at Knossos also found an ivory figurine, which may be part of a bull-leaping group. The figure is most likely meant to have been positioned flying through the air, for it has pointed toes as well as outstretched arms.

Beyond that, there are several bulls’ heads made in stone that have been found at Knossos, some of which appeared to have been deliberately smashed, perhaps after a ritual. These stone heads were hollow, with holes at the nostrils, so that if they were filled with red wine, for instance, and then held at the proper angle, it would look like the participant was holding the head of a bull that had just been sacrificed to the gods and was still dripping blood.

![]()

And so, it seems that the Minoans were perhaps doing some bull leaping in their central courtyard as well as some rituals involving bulls in or around the palace. This in turn brings to mind the Greek myth of Theseus and the Minotaur. Back in the Bronze Age, King Minos demanded a sacrifice each year to the Minotaur, the half-man half-bull creature who was living in the basement below his palace at Knossos. The basement was a labyrinth, from which no one had ever gotten out alive. Each year the king of Athens had to send seven young boys and seven girls to King Minos, who then sent them down into the labyrinth.

One year Theseus, the son of the king of Athens, volunteered to go, so that he could try to kill the Minotaur and put an end to the annual sacrifice. His distraught father agreed. Once he got to Knossos, Theseus befriended Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos. She provided him with a sword and a ball of string. As he went through the maze, he unwound the ball of string, so that he could find his way back out. When he got to the Minotaur, he pulled out the sword and cut off the Minotaur’s head. He then retraced his steps and emerged victorious.

I have long thought that the story may have been created in an attempt by later occupants of the area to explain the ruins of the palace of Knossos, as well as to account for the vague memories that they had about their ancestors doing something with bulls, and especially the mazelike appearance of the ruined storage areas.

I may be completely wrong about that, however, and there might be another explanation entirely, because in the early 1990s, a huge wall painting was found, depicting multiple bulls and numerous bull leapers in action in front of what can only be described as a maze or a labyrinth. It is a painting that we would understandably expect to find at Knossos, except that’s not where it is. It’s not even in Crete. It is, in fact, in the Nile Delta region of Egypt, at the site of Tell el-Dab’a. And it dates somewhere between the seventeenth and fifteenth centuries BCE; that is, right in the middle of the second millennium, during the Bronze Age and the height of Minoan culture.

Therefore, it may be that the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur has some kernel of truth in Minoan practice and was not made up later to explain the ruins of Knossos. But the very fact that such a painting is in Egypt, even though it depicts a Minoan motif and was created using techniques that were quite different from those of the Egyptians at that time, is to my mind even more interesting. The excavator of the painting suggested that perhaps a Minoan princess had been brought over for a dynastic marriage. I don’t think it is necessary to have such an elaborate explanation, but certainly the presence of the painting shows that Egypt and Crete were in direct contact at that time. I suspect that it was created either by Minoan artists or by local artists who had been trained by Minoans. We already knew from other evidence that such connections existed, but it is fascinating to find such a vivid corroboration of the international connections that were ongoing across the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean during the Bronze Age, more than three thousand years ago.

![]()

Schliemann is usually given credit for discovering the Mycenaeans on mainland Greece, and Evans usually gets credit for discovering the Minoans on Crete, but there is another group that flourished in the Aegean region during the Bronze Age—on the Cycladic islands that lay north of Crete and east of mainland Greece.

These islands, including Naxos, Paros, Melos, Thera, and others, had their own Cycladic culture, albeit with many interconnections with the Mycenaeans and Minoans. They are probably best known for the marble figurines from the Early Cycladic period, during the third millennium BCE, which depict primarily women, but also figures playing musical instruments such as a double pipe and what may be a harp or lyre. At least some of them were involved in the international connections that were ongoing a bit later during the second millennium BCE, including the island of Thera, perhaps better known today as Santorini. We shall discuss those events in the next chapter.