____________

September 11th: The Terrible News

As anxious as we were, Evan and I and many other passengers couldn’t see live TV images, hear radio, read a website, or even call anyone to verify the news we’d been told. It was clear there was a crisis in the US, but without seeing TV or reading anything, it was difficult to imagine.

The idea of airplanes purposefully crashing into buildings seemed absurd. I couldn’t picture it in my mind. I wondered if there were additional planes headed for landmark buildings across the US.

Around 3 p.m., a woman sitting in the row behind us was starting to have an argument with her husband. After five hours on the tarmac, she wanted off the plane and didn’t understand why we weren’t being told more details about what was happening in America and whether or not we were going home. She wanted a phone to call her young children in the US, but that wasn’t happening. She kept getting louder. Everyone around her could hear her anxiety and frustration. Her husband tried to quiet her, but that only made her cry harder. Evan turned around and asked if she needed some medication to ease her nerves. The husband declined.

Evan and I agreed that our friends and family would be worried because we were scheduled to fly into New York City that morning. My flip phone was useless for international calls. On our plane, the only passengers making contact with anyone overseas by phone were sitting in first class. Their seats came with satellite phones that were activated by credit card. After hours of hearing a few, uninformative updates from the captain, I walked up to first class and found a man with an empty seat next to him. He was happy to let me sit there and use the phone. I tried calling my parents in Nashville, Tennessee. I tried also calling my office in Austin, Texas. No luck, the calls never connected. I tried calling friends in other time zones. As I swiped my credit card over and over again, I kept hearing the message “All circuits are busy.” The country’s phone system was overwhelmed.

Later, I would learn that virtually everyone in America was calling everyone they knew to make sure they were okay. I returned to my seat.

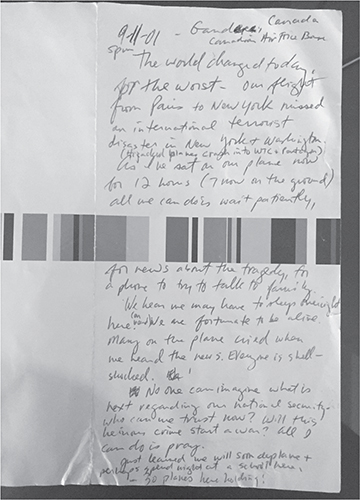

Around 5 p.m., I took out my frustration by journaling on the Air France flight menu:

I started journaling on our in-flight menu. PHOTO CREDIT: KEVIN TUERFF

9-11-01-Gander, Canada, Canadian Air Force Base

The world changed today, for the worse. Our flight from Paris to New York missed an international terrorist disaster in New York and Washington. (Hijacked planes crashed into WTC & Pentagon.)

We’ve been sitting on our plane now for 12 hours (7 now on the ground). All we can do is wait patiently for news about the tragedy, for a place to try to talk to our families.

We’ve been told we may have to sleep here overnight (on board). We are fortunate to be alive. Many on the plane cried when we heard the news. Everyone is shell-shocked.

No one can imagine what is next regarding our national security. Who can we trust now? Will this heinous crime start a war? All I can do is pray.

P.S. Just learned we will soon depart plane and perhaps spend night in a school here. At least 30 planes here waiting with stranded passengers aboard.

Around 6:30 p.m. in Gander, it was getting dark outside my window. I walked back up to first class with the idea of calling Europe, instead of the United States. It worked. I reached my high school friend Todd, who lived in Amsterdam, around 11 p.m. Netherlands time. We had just visited Todd a few days earlier on our vacation. That afternoon Todd was walking around Amsterdam with a friend from New York when they heard about the attacks. They decided to go to her house to watch the news. When I reached him, I asked, “Is it true what they’re saying?”

“It’s horrible,” he replied. “I’m watching it live on TV now.”

Todd explained that terrorists had hijacked the planes and ultimately destroyed both towers of the World Trade Center, killing thousands. Another plane crashed into the Pentagon, and yet another—which may have been headed to the White House or the Capitol—crashed into a field in Pennsylvania. Early estimates of the dead were nearly 10,000. We didn’t know about the plane in Pennsylvania. Tears welled up in my eyes. I was more scared than I could remember, and so was Todd.

I told Todd how I was stuck on the airplane and I couldn’t reach anyone in America to let them know I was safe. I asked him to try to call my parents in Nashville and my office in Austin. I also gave him the names and phone number of Evan’s parents.

I returned to my coach seat and shared the information with other passengers. Standing up, I spoke to a few people in the row behind me, but soon, dozens of passengers seated within earshot were glued to my every word. Listening to an American confirm that what we had heard from the French pilot was true brought on a deep sense of grief around us. Nobody asked for more details, because they knew I didn’t have anything more.

There were passengers on our plane from more than twenty-five countries. Despite such an international melting pot of passengers, everyone seemed to be getting along.

Everyone wondered if they knew someone who might have been harmed.

We felt horrible for the family and friends of the people on those four domestic flights, not to mention the workers and first responders in the World Trade Center and Pentagon. Months later, we would learn that 2,996 people were killed and more than 6,000 injured.

· · ·

In all, we sat on the airplane for more than eighteen hours from the time we first boarded in Paris. The crew tried their best to reassure anxious passengers by giving out free liquor and playing and replaying movies on the overhead TV (instead of the GPS screen). For every hour that went by, we kept getting more free drinks, while someone hit rewind to watch Shrek for another, agonizing time. It felt strange to laugh at jokes in a movie while New York and Washington were burning. The Leonard Cohen song from the movie, “Hallelujah,” kept repeating in my mind in Rufus Wainwright’s beautiful voice.

I felt helpless. I wanted to help my fellow Americans, or reach out and talk to friends and family.

Meanwhile, the lack of communication was causing my family stress. My older brother Brian had gone on a Gulf Coast fishing trip with friends in South Texas that day. His boat had headed out before the attacks began, so he didn’t know about the tragedy unfolding. His wife Jana desperately tried to reach him about me, but could only call the marina manager. She told the manager to let Brian know what was happening as soon as he returned and to tell him that I was okay. When Brian’s boat arrived late that afternoon, the marina manager anxiously greeted my brother and got the story backward. He told Brian, “Your brother was on a plane. Planes crashed into the World Trade Center. But, he’s okay.”

Brian freaked out, thinking I was killed during my flight. My parents and my brother in Nashville saw the attacks on the news. Fortunately, my brother Greg was able to access the Air France website, which showed our status as having landed in Gander, Newfoundland. They had to look up on a map to see where that was in Canada.

Greg was able to contact Jana, so that later, when Brian called Jana, she clarified that I was safe in Canada. By this time, all flights were canceled, so Brian and his friends rented the last car in South Texas and drove straight home to Austin, arriving five hours later.

If I were at home in Austin, I would certainly be at the office, glued to the television. At my company in Austin, there was a lot of anxiety. Both company principals were traveling that day, one returning from a trip to the US Open in New York City, and me, returning from Europe through New York. Sara Beechner, the manager on duty, was getting ready for work when her fiancé called her into the living room to watch the attacks on live TV. She recalls, “I remember the optimist in me thought, ‘What a horrible accident. How could someone accidentally crash a plane into the tower?’ I just couldn’t compute it to be terrorism; I didn’t understand the gravity of the situation. I had to get into the office.”

Valerie Davis, the other company principal, landed safely in Austin. She had been on one of the last planes to leave New York before the attacks, and one of the last in the air before the airspace was shut down. Sara later told me, “We got word Valerie was safe, so we were just trying to figure out, ‘Where in the hell is Kevin Tuerff?’”

Staff were in shock because news reports were unfolding that other planes in the air could be potential missiles all across the country, and there was no way I could reassure them that I was okay.

Thankfully, my friend Todd was successful at contacting my friend and colleague Sara in Austin and letting her know Evan and I were safe in Gander. Sara took it from there, calling both sets of our parents. They were relieved to know we were okay, even after they had seen the flight updates.

More than eleven hours after we landed in Gander, plus the six more from when we traveled from Paris, we actually left the plane.

Our captain had no information about where we would be going except that it was a shelter. But he told us we could not take our luggage, only our carry-on bags. Authorities were fine with screening passengers, but there was fear that luggage might contain bombs.

Were we going to a refugee camp with tents and cots? Should we take pillows and blankets? I wondered. Unsure of what we were in for in this tiny town of Gander, Evan and I spotted and swiped a full, sealed bottle of Evian water from the flight attendant cart as we deplaned. In our carry-on bags, we had three cameras, two passports, and two sorely needed bottles of vodka.