____________

What Now? Kindness and Refugees

“For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me.”

—Matthew, 25:35

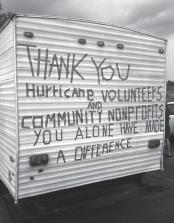

For it is in giving that we receive. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana and created hundreds of thousands of refugees, especially from New Orleans. My hometown of Austin welcomed more than 4,000 of these refugees whose homes were flooded. In Gander-like fashion, Austinites donated food, clothing, and shelter to those who were living in the Austin Convention Center. Many people helped New Orleans families who had lost everything settle in Austin. That year, the sole focus for Pay It Forward 9/11 efforts by staff was to help hurricane refugees. I also volunteered one day, signing up to help at the civic auditorium to help those with medical needs.

Austin reacted with Gander-like kindness when they helped New Orleans refugees who had been forced from their flooded homes by Hurricane Katrina. PHOTO CREDIT: MATT CURTIS

I’ll never forget meeting eighty-year-old Lysle within a few minutes of arriving at the shelter. As he was exiting the bathroom, I simply asked him how he was doing, expecting him to say, “Okay.”

Instead, he said, “Not so well, I can’t find my wife.”

I asked him to sit down in the cafeteria so I could learn more. Lysle’s wife had cancer, and she had been staying at Mercy Hospital in New Orleans when the floodwaters required all patients to be evacuated by helicopter. Unfortunately, that meant loved ones were on their own. Lysle was sent to the New Orleans Convention Center, which was hardly functioning as a working shelter. Toilets weren’t working, and power was intermittent. When Lysle went to sleep that night, he took out his hearing aids and laid them on his one suitcase. Sadly, someone stole the suitcase and hearing aids while he slept. Eventually he was rescued by the National Guard, and put on a flight for Austin. When he landed, he thought he was in San Antonio. This reminded me of when I was stranded in Newfoundland, when I first thought I was in Nova Scotia.

Using Gander-like inspiration, I took on the job of a social worker, trying to help him get information about his wife and connect him to his relatives. All Lysle knew was that his wife was being medevaced to a hospital in Baton Rouge. That was enough for me to start. After finding the phone number for hospitals in the city, I called and asked if his wife had been admitted from New Orleans. I got lucky on the first try. After a few minutes of explaining who I was, a nurse put his wife on the phone, and then I handed my cell phone to Lysle. He started to cry when he heard his wife’s voice. It had been five days since they last spoke. She didn’t know where he was, or if he was alive.

His wife reminded Lysle that he had a relative who lived in Austin. They gave me his name, so I called 411 information and was lucky enough to reach him by phone within minutes. I told him his great-uncle from New Orleans had been sent to the Austin refugee shelter. He told me that his relatives were all worried about him, not knowing where he had been sent. Within an hour, a young man had arrived at the shelter, ready to take Lysle to his apartment. The next day, I called a hearing aid company, telling them the story of Lysle and his stolen hearing aids. They said they would happily help him out by donating a new set to him. Weeks later, Lysle’s wife was discharged from the hospital. Their New Orleans home was still off limits from the flood, so she came to live with Lysle in Austin for a few weeks. I was blessed to be able to witness their emotional reunion.

Americans are truly great at helping neighbors and strangers when there is a natural disaster. We need this same type of compassion year-round. Too often we let fear get in the way.

The plane people or “come from aways” stranded in Gander were temporary refugees of war. A war begun by Osama bin Laden had broken out in New York, Pennsylvania, and Washington, DC. Canadian authorities could have treated the stranded passengers as refugees with terrorists among us, leaving us on the planes for days, perhaps sending out food and water. But they didn’t. Every person in Gander and the surrounding towns took a chance and offered us kindness and goodwill. They let us off the planes and took care of us in the most beautiful, loving ways.

In 2016, I asked Gander mayor Claude Elliott whether they had been nervous about permitting a terrorist from one of the planes to enter their community when they helped us on that tragic day.

“I don’t think we can live our life in fear. Not everybody is out to do bad things. We have to realize that not every Muslim is a terrorist. Of course there are bad people out there, but we were willing to take that chance. We weren’t going to let people suffer on those planes for four to five days. That never came into our minds. Even though we’ve received thousands of accolades, that’s not why we did it,” he said. “We just said ‘thank you’ and we were paid in full by knowing we helped people at a very difficult time.”

Ganderite Diane Davis echoes Mayor Elliott’s sentiment. “We had passengers from all over the world, but we had no conflicts or trouble,” she says. “Fear and misunderstanding lead to extreme action, but they can also lead to empathy.”

Would a small town in rural America welcome planes of international travelers, especially if some came from Arab countries? Some would, of course. Others would let fear rule the day, and might encourage somebody else, like the federal government, to handle the crisis.

At the Seattle performance of Come From Away, I was invited onstage for an audience question-and-answer session for those interested in staying longer after the show. Virtually everyone in the audience stuck around.

I was asked about how my perspective of Gander has changed me, then versus now. I replied, “During the attacks of 9/11, stranded American airline passengers became temporary refugees. The Canadians didn’t have to let us off the planes, but they did. Why is there so much hysteria about helping others in our country today, especially millions of Syrian war refugees?”

· · ·

According to the US State Department, the US admitted 12,500 Syrian refugees out of the five million who fled their country due to the ongoing civil war.

By November 2016, the Canadian government had already resettled 44,000 Syrian refugees. I was not surprised to learn the town of Gander was again acting as a role model for compassion and empathy for Syrian refugees.

It was the unforgettable photo of Alan Kurdi, the young Syrian boy whose lifeless body washed up on a shore in Turkey, that galvanized people in Gander to step up and help refugees once again. Gander’s town council organized a meeting that drew more than forty people, some of whom then formed the Gander Refugee Outreach Committee.

During a 2016 trip to Gander, I met members of the Alsayed Ali family, one of the first Syrian families adopted by Gander Refugee Outreach. PHOTO CREDIT: KEVIN TUERFF

Mayor Elliott said, “We figured opponents would show up to the meetings, but we have not had one individual with a negative view, it’s only people wanting to help. We had no major objections to bringing Syrian refugees to Gander from anyone in the community. Everyone believed that if you brought in a family, we had little to fear.”

When the towns of Gander and Lewisporte decided to adopt five Syrian families, the Canadian government required that they raise $15,000 per family to receive federal funds to assist the families.

Diane Davis retired from teaching and has become a fulltime volunteer for Gander Refugee Outreach. Just as she did for the 9/11 come from aways, Diane is doing anything and everything she can to help the Syrian refugees resettle in Gander. She helps coordinate volunteers, soliciting supplies, arranging for medical care, and explaining Gander culture.

Diane explained how challenging it was to raise money for the effort.

“There was no single donor who could write a check. The Anglican Church was first in raising funds through bake sales and other small fund-raisers. The United Church was next in raising money for the second family. Each of these churches had other fund-raising needs, like paying for roof repair on the church.” She added, “But they prioritized the families in need.”

Because Gander is a small, rural town, there’s a shortage of physicians. One doctor, originally from Syria, commutes to Gander to help. He happened to be on a plane with the second of five Syrian refugee families that were being welcomed in Gander.

When they arrived in the Gander Airport terminal, he witnessed an outpouring of love similar to what I saw on 9/11. The terminal was filled with people, including dozens of children, who came to welcome their new residents.

He told CBC-TV, “The first thing we saw was their little child come out … he was stunned to see all these people at two in the morning.” He added, “The waiting children rushed toward the boy in welcome, as the rest of the family appeared and began to cry.”

The Syrian-Canadian doctor was moved. He went on, “Here I’m helping Gander, and here Gander is helping people of the same heritage as me.”

Having worked closely with the families for six months now, Diane knows a lot about Syrian refugees. She believes if more people looked at refugees as individuals and families, not statistics, they might see that we are more the same than we are different. “We both like to cook and to feed people. We both want our kids to get an education. We both want to work to support our families. If we get hurt, we cry. If we get cut, we bleed. If we tell a joke, we laugh.”

One of the Muslim refugees told Diane she was impressed how the Christian church volunteers practiced their religion through good deeds rather than just words. Diane says these new Canadian residents have one year of funding from the Canadian government to find work to support their families.

The refugees want to succeed, to live without social services from the government. Right away, they have done everything from cleaning dishes at a restaurant to mowing lawns. They want to be able to volunteer in their communities to help others. They want to pay it forward.

According to Refugees International, the number of displaced persons forced from their homes globally has risen from twenty-five million to sixty-five million people from 2011 to 2015. This is a crisis that goes beyond the Syrian civil war. Thousands of people are being displaced across the globe because of changes in climate and related ability to work. When tremendous floods or droughts hit a country, it’s impossible for farmers to provide for their families. They may migrate within their country to a suburban area, but then they face the challenge of finding jobs that aren’t in agriculture. It’s a safe bet that almost all of these refugees aren’t as fortunate as we were when we were stranded in Gander. Many live in tents without running water, food, or healthcare. These challenges aren’t going away. In fact, if we don’t sufficiently deal with the underlying causes of forced displacement, we could see more wars, more refugees, and less peace.

When the Come From Away production came to Gander for two shows, Diane Davis arranged for fourteen Syrian refugees to see the show. They received VIP seats in the front row.

Unfortunately, within days of taking office, President Donald Trump called for an immediate halt to resettlement of Syrian refugees in the United States.

The kindness of strangers in Gander inspired me in 2001 and again in 2016. My faith in God and all humanity is stronger because of my experiences with Gander. Now it’s my turn to champion the cause of immigrants and refugees. I have embraced my role as a channel of peace. Where there is hatred, let me bring love.

The famous Christian line “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” (Matthew 7:12) has almost identical teachings in Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, and Islam. My prayer is that as countries across the globe, we can work to better understand how much we have in common. Differences in gender, race, religion, political party, or sexual orientation shouldn’t draw battle lines between the human race. We need each other to coexist in peace.