The fate of Max Weber’s Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism is a compelling chapter in the sociology of knowledge. The social forces affecting Talcott Parsons’s translation offer a larger lesson about the politics and sociology of the articulation, presentation and dissemination of Weber’s thought. The lesson applies to subsequent developments as well—especially the second and third crucial steps forward for Weber’s American and Anglophone readership: the timely postwar publication in 1946 of Hans Gerth’s translations, assisted by C. Wright Mills, of some of the most important texts from the Weber corpus in From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology; and in the following year Talcott Parsons’s final major investment in translating Weber, the first part of Economy and Society that was published under the ambitious Parsonian imprimatur of The Theory of Social and Economic Organization, a title connected only vaguely to Weber’s original manuscript.

While Parsons’s version of the The Protestant Ethic surely deserves a special place in the pantheon of Weber’s works, the two texts of 1946 and 1947 extended knowledge of Weber into new and uncharted domains. From Max Weber offered a concise tour of central texts on politics, science, the sociology of religion, bureaucracy, charisma, and other topics lifted from Economy and Society, while The Theory of Social and Economic Organization posed on its paperback cover as “The most extensive general exposition of Max Weber’s sociological theory and its applications to the broad empirical problems of historical structure and change.” Parsons meant every word of this promotional blurb: Behold, at last, Weber the general theorist! The claim has prospered and acquired a life of its own. When a few years ago the International Sociological Association decided to canvass opinion concerning the most important books of the twentieth century in sociology, the uncontested winner turned out to be not The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, which finished a close fourth, but Weber’s Economy and Society. It is an astonishing outcome for a treatise cobbled together mostly from manuscripts and notes never prepared for publication as a coherent whole by the author himself.

From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology arrived with the postwar American universities and the social sciences entering a new phase of unprecedented expansion. Gerth and Mills’s choice of a “reader” format for their selections, a text designed for classroom use that opened with an informative and dramatic introduction to Weber’s life and work, revealed their superior editorial savvy, supported by marketing expertise at the Oxford University Press. Even Edward Shils, who threatened to delay the project or cause it to wither on the vine, as Guy Oakes and Arthur Vidich have shown, was moved later to pen his grudging admiration. But he did so behind the scenes, so to speak, and not in a text intended for publication during his lifetime, writing, “Although I think that the translations that Gerth and Mills made from Max Weber are not very good, still, they are the works which really put Max Weber ‘on the map’ in America and England. Prior to the appearance of that miscellany, the writings of Max Weber available in English were rather peripheral, although very fine in their own way. But Gerth and Mills did make some rather important writings widely available, albeit in a very melodramatic interpretation and in a selection biased in that direction.” Even when meting out praise in a private memoir, Shils could not avoid the caustic aside, enjoying jabs at Gerth’s “incoherence” and “unintelligibility,” or in his most delicious swipe at Mills, writing that he “would have been an ordinary, vigorous, semi-literate and productive ruffian if it had not been for the civilizing influence of Gerth’s knowledge of Max Weber.” This salvo from Shils’s arsenal must rank as the most original form of praise Weber has ever received. It is understatement to say that there was little quarter given by these competitors during and after the publication of From Max Weber.

Oakes and Vidich have recorded and traced in detail the remarkable record of initial cooperation, followed by competition, concealment, bad faith, and professional jealousy that eventually ruined the relationship between Gerth and Shils. As Oakes and Vidich have concluded, agreeing with Mills’s own judgment, the new Weber reader could only have been published at the cost of the collegial friendship between Gerth and Shils. In this regard two considerations were decisive. First there was the episode they rightly call the “Shils affair” which was in its most serious aspects a struggle over “priority” claims in science. In this tangled relationship Gerth had entered onto a terrain first occupied by Shils with his mania for translating difficult Weber texts. The entry was in a sense fortuitous, for by his own account Gerth found himself in Madison, Wisconsin, a registered alien during wartime not allowed beyond the city limits without special permission. In a therapeutic effort to relieve boredom and perhaps coincidentally to improve his English, he turned to translating Weber texts. From his point of view Shils had already taken up the difficult task of translating Karl Mannheim, completing Ideology and Utopia (1936) with Louis Wirth, then moving on to Man and Society in the Age of Reconstruction (1940). In the publishing world of all the major German language predecessors it was still Weber who remained essentially untouched. From Gerth’s perspective what better task than to begin filling this gaping omission. But for Shils this apparent division of labor hardly squared with his personal sense of mission. Gerth was in the nature of things a dangerous competitor, trespassing on sacred ground. Both by education and working relationships with people like Mannheim, and importantly because of his linguistic competence, he was in a position to supplant Shils altogether.

Second, Gerth’s casual account of his entry into the Weber field concealed a disciplined pedagogical intention identical to that of Knight and Shils at the University of Chicago: providing good new texts on important subjects to his students, expanding their reading and enhancing his teaching. He also employed a similar method, enlisting graduate students as copy editors to produce a perfected and idiomatic draft, approved by Gerth after careful comparison with the original, and then mimeographed for class use and distribution. In the University of Wisconsin sociology department Mills became one of these favored students. Thus, what began as a pedagogical exercise was slowly transformed over several semesters into a local publishing venture for Weber texts, in the course of which the editorial relationship and division of labor between Gerth and Mills was defined.

As strange as it may seem, Mills’s role in the priority dispute and the management and promotion of Gerth’s talent was a major contributing factor to the promotion of knowledge about Weber and his work. Left to his own disorganized brilliance, Gerth would most likely never have compiled a set of Weber texts that would have attracted the attention of a major prestigious press. But with Mills’s entrepreneurial bent, career ambitions, feel for audience and publishing markets, and sheer chutzpah and “street smarts” the senior immigrant scholar and the erstwhile University of Texas undergraduate Charlie Mills became a formidable team.

What emerged from this collaboration, then, was exactly the kind of “Weber source book” that Ralph Barton Perry had envisioned when Parsons was translating The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism—a text that was, of course, nothing like a compendium of Weber’s thought. There was a need in Perry’s view for an inexpensive reader useful for meeting the pedagogical needs of American higher education, where the teaching function was essential and where, in the best of circumstances, the introductory lecture and the reading and analysis of texts were connected to larger purposes in a competitive environment: attracting an audience, recruiting promising students, and promoting graduate education and programs of research. It was in this sense and this context that From Max Weber was able to “put Max Weber on the map,” as Shils noted.

Furthermore, the Gerth and Mills partnership led to an outpouring of publications, including the collaborative work in social psychology, Character and Social Structure (1953), but mainly the popular treatises Mills assembled with the assistance of borrowings from Gerth’s fertile field of ideas, such as White Collar: The American Middle Classes (1951) and The Power Elite (1956). Reworking the theory, Mills’s masterstroke was to demonstrate the ways in which elements of Weber’s thought could be elaborated into a “Weberian” critique of social class, status, power, and organization in modern America. To be fair to Mills regarding his relationship with Gerth, however, he did strongly encourage his comrade in thought to take the next giant step forward regarding Weber’s work. “Why don’t you do the definitive intellectual biography of Weber?” he challenged Gerth. “Why in God’s name don’t you get onto it? You’re the obvious man to do it. It would be the way, the royal way, to consolidate all your work in translation. If you did decide to do it, please know that as far as the English is concerned, I should be glad to edit the manuscript with no mention of my name in any way. I mean that. Do think upon it. As far as the publisher is concerned, just now that would be no problem” (December 22, 1959). Gerth did follow up with the Oxford University Press, but he also allowed teaching and the trivia of everyday life to clutter his days, and then with Mills’s sudden death the project lost its impresario. We are, it seems, still awaiting the great definitive work.

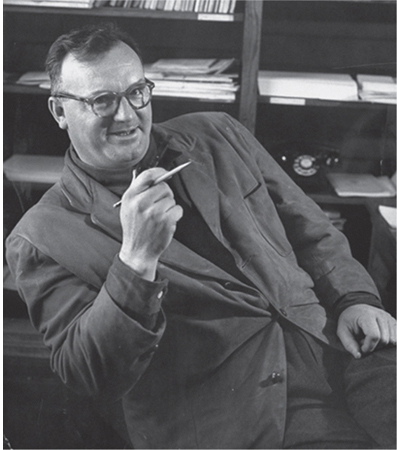

Figure 12. C. Wright Mills in his Columbia University office in 1954, with the Weber translations behind him, photographed for Life Magazine as the celebrated author of White Collar. Photograph by Fritz Gorro. Reproduced by permission from Getty Images.

The collaboration begun at the University of Wisconsin, centered around Hans Gerth, did produce the completion of the project Oskar Siebeck and Talcott Parsons had in mind in the 1920s, though not at all in their preferred form: the complete translation of Weber’s three-volume Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Religionssoziologie. At least these Collected Essays in the Sociology of Religion became available in the English language, though they were scattered out of sequence through five different books, including Gerth and Mills’s own reader. What remained unavailable still was the formidable body of work many considered Weber’s magnum opus: the collection of material known as Economy and Society. The summons to rectify that omission landed once again on the desk of Talcott Parsons.

The project of publishing the totality of Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, much less translating it, is a tangled affair. Most of the German text, drawn from unfinished manuscripts left on Weber’s desk, was published posthumously by Marianne Weber with the assistance of Melchoir Palyi. The editorial complications have only been exacerbated with the passage of time because of several factors: the disappearance of large blocks of Weber’s handwritten original; the problem of the work’s location in the Grundriss der Sozialökonomik, the multivolume basic outline of social economics that Weber himself had supervised over the last decade of his life as the general editor for Oskar Siebeck; the relationship of Weber’s contributions to that encyclopedic enterprise; and finally, the fact that Marianne Weber’s edited text, modified by Johannes Winckelmann, has come under critical scrutiny and been challenged for accuracy, even as to the very title of the work. The current reconstruction by the editors of the Max Weber Gesamtausgabe promises to bring a resolution of these difficulties, at least for the German text.

Encountering Weber in the 1920s and working on the problems of his thought in the 1930s, Parsons was oblivious to such editorial issues. He first bought and read the text of Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft while a student in Heidelberg, the 1922 edition published in the third section of the Grundriss der Sozialökonomik, the text edited by Marianne Weber and Palyi with the intention of presenting a systematic and coherent treatise. The book preserved in his papers, with the notation “Talcott Parsons Heidelberg 1925” in his own hand, contains considerable underlying (in four colors of pencil!) and numerous marginalia in both German and English. Presumably the German phrases were written earlier, though we cannot be certain. In any case, the text was well worked over—many times over.

If Parsons read The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism rapidly like a detective story, then he must have worked his way gradually through Economy and Society as a monumental epic like Homer’s Odyssey or Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, if not, as Wolfgang Mommsen has suggested, “like a Chinese book.” This was an eye-opening exercise entirely unlike the encounter with The Protestant Ethic. But Parsons continued the same practice begun previously of jotting succinct marginalia: for example, sehr wichtig and Anknüpfung an Sombart—“very important” and “in reference to Sombart”—are penned alongside the heavily underlined characterization by Weber of Henry Villard’s “blind pool” maneuver against the stock of the Northern Pacific Railroad as an example of “robber capitalism”:

The structure and spirit of this robber capitalism [Beutekapitalismus] differs radically from the rational management of an ordinary capitalist large-scale enterprise and is most similar to some age-old phenomena: the huge rapacious enterprises in the financial and colonial sphere, and “occasional trade” with its mixture of piracy and slave hunting. The double nature of what may be called the “capitalist spirit,” and the specific character of modern routinized capitalism with its professional bureaucracy [der spezifischen Eigenart des modernen, ‘berufsmäßig’ büreaukratisierten Alltagskapitalismus], can be understood only if these two structural elements, which are ultimately different but everywhere intertwined, are conceptually distinguished.

The example drawn from the Weber family chronicles and America’s Gilded Age posed a question about the “rationality” of mature capitalism, raised also by Sombart. It caught the young Parsons’s attention, for in passages like these he found not only the familiar but also a formulation of the concept of modern capitalism—the “specific peculiarity of modern ‘vocational’ bureaucratized everyday or ordinary capitalism,” when read literally. The concrete became abstract, for Parsons also saw in Weber’s text a theoretical analysis of the larger, more general problem of “rationality” as such—especially the rationality of all social action.

As we have seen, various efforts at translation of Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft involving Knight, Shils, Alexander von Schelting, and others gained headway in the 1930s. Declining earlier entreaties, Parsons finally took up the task in 1939, and only then, as he acknowledged, through an inquiry from Friedrich von Hayek, with Fritz Machlup, the University of Buffalo economist, serving as intermediary. Having left Vienna for the London School of Economics, Hayek had encouraged a young economist, Alexander Henderson, to translate the first two chapters of the text. Concerned about the quality of the translation, he then approached Parsons for advice. Parsons found the work deeply flawed and expressed his initial misgivings to the editor, James Hodge in London:

[T]his work [Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft], particularly the first chapter, presents one of the very few most difficult problems of translation which I can imagine. Some of the main reasons are the following: It is a highly technical work, and Weber is presenting the barest outline of a conceptual framework without all the detailed explanation and application which would serve to make it much more readily intelligible. Then, particularly in its methodological parts, it builds upon a development of thought, and discussions around its problems, which have had no direct counterpart in the English-speaking world. Hence many terms and references would be intelligible to the initiated German reader which have no near equivalents in English at all. Weber built upon this tradition and gave many of these terms a further specification of meaning which accentuates the problem. Then finally Weber’s own style is, apart from these considerations, peculiarly difficult. (January 26, 1939; TPP)

In view of these reservations Parsons went on to question “the advisability of even attempting a direct translation.” He thought the effort might be worthwhile, however, but only with careful editing, close attention to subject matter and conceptual language, and a comprehensive introduction—a brief for his own intervention.

Parsons’s response could be considered self-serving, but he obviously had a point about Weber’s language. Conceptual building blocks like Zweckrationalität (instrumental, purposive, or means-to-ends rationality), Vergemeinschaftung (the process of forming communal relationships), Vergesellschaftung (the process of forming social relationships; sociation, or association), or even the common adjective sinnvoll (meaningful) presented special difficulties that had to be addressed. In Parsons’s view Henderson’s apparent penchant for using “end-rational” for zweckrational or “significant” for sinnvoll only added new levels of obscurity. Nevertheless, though his defensiveness cannot be surprising, Henderson was surely correct in seizing on the essential issue: as he wrote to Hodge, “Weber makes his reader think in terms of concepts which are new to the English reader and if the concepts are to be used a new terminology must come too, and it does not greatly matter whether new technical meanings are given to ordinary words or whether new words are coined, but there is no escape from the alternative” (undated, but prior to March 14, 1939; TPP). In other words, the task at hand, both men agreed, was the invention of a new conceptual language, an edifice of interconnected nouns, verbs, and adjectives that would capture the structure and content of Weber’s thinking.

In the correspondence that followed Parsons acceded to Hodge’s request to revise Henderson’s draft of chapters one and two of Economy and Society while also persuading the editor to include chapters three and four and thus complete part 1 of the text, arguing correctly that it was a conceptual whole that should not be split apart. Part 1 was in fact the “Conceptual Exposition” or the “soziologische Kategorienlehre” that Weber had written last, in 1919 and 1920, and prepared for publication himself. A decade had passed since Parsons’s struggles with Stanley Unwin and R. H. Tawney, and with the success of The Structure of Social Action (1937) to his credit, he was in a position to impose his will on the project. The roles were now reversed, with Parsons assuming Tawney’s mantle as arbiter and judge. Called to military service, Henderson faded from view, never submitting the translation of chapters 3 and 4 that Parsons had requested. Left to the field himself, Parsons completed a draft translation in about four months, adding in a note to Robert Merton that he was also finishing his “theoretical essay” or introduction to the whole (September 28, 1939; TPP).

World War II delayed publication for eight years. In the meantime Parsons had the text microfilmed, sending copies to Merton at Columbia University and Howard Becker at the University of Wisconsin for their department libraries. In preparing the text he consulted with Professor Edwin Gay, the economic historian and his Harvard University colleague, about the terminology in the lengthy second chapter on the sociological categories of economic action that has too often been overlooked, though revived recently through the efforts of Richard Swedberg. In addition, he used the earlier translation by Shils and Schelting.

Parsons’s larger purposes were twofold: first, the abstraction from Weber’s empirical interests of a theoretical point of view. Commenting on his practice as a translator to Louis Wirth, Parsons put the matter succinctly:

Weber’s theoretical analysis is most definitely bound up with the empirical interest in capitalism. It seems to me that this comes out in most striking fashion in the classification of the types of action in which the two rational types are very clearly the center and the two non-rational types essentially residual in character. The same applies to the whole typological system of Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. My careful working through of the early part of that book in connection with the translation strongly confirms this impression. At every crucial point, Weber is concerned with the problem of what constitutes rationality of action and of the conditions on which it is dependent. In the famous classification of the types of Herrschaft it seems to me quite clear that rational, legal Herrschaft is the conceptual starting point and that the other two types are formulated primarily as antitheses of this in different respects. (October 6, 1939; TPP)

If the translation laid bare the logic of Weber’s thinking and underscored his contributions as a theorist, then it also accomplished a second purpose: introducing the audience to an altogether different Weber. The aim became explicit in Parsons’s introduction to the work, for there, as he explained to Eric Voegelin,

I have dealt with some methodological problems of Weber’s work, but have given by far the largest amount of space to what might be called his institutional sociology in the economic and political spheres, with special reference to his interpretation of the modern western social order and its sources of instability. It seemed to me particularly important to lay stress on this aspect of his work since Weber is, as you know, known here either as the naïve idealist of the Protestant Ethic or the methodologist of the ideal type. This institutional aspect of his work has hardly penetrated the English-speaking world. (August 1, 1941; TPP)

Parsons’s own work had unintentionally assisted in promoting the earlier partial impressions of Weber’s thought. The new translation offered an opportunity for correction, setting forth a comprehensive theoretical vocabulary designed for institutional and structural analysis.

Parsons succeeded with the publication of The Theory of Social and Economic Organization, a title he suggested to Hodge, in presenting the scientific Weber with an appropriate conceptual terminology. He replaced the more colloquial and literal language often favored by Shils and Schelting with more abstract and generalized locutions: for example, “application to subjective processes” for innerlich (inward, inner) or “the objective point of view” for äusserlich (outer, external). He proposed the elaborate conceptual terminology for identifying the types of social action, the bases of legitimacy, the categories of social and economic action, and the system of social stratification. Almost all of it has remained in the complete text of Economy and Society that is read today, with the exception of the ill-advised and awkward choice of “imperative control” or “coordination” for Herrschaft, penciled late into Parsons’s typescript, rather than the by-now-standard terminology of “domination” or “authority.” In the rarified atmosphere of modern social theory Zweckrationalität has earned a life of its own, most often as “instrumental rationality” in the authoritative translations of Jürgen Habermas’s work. And an elusive concept like Vergesellschaftung, which Parsons rendered variously as “associative relationship” or “organized activity,” simply has no settled solution and never will. Parsons’s initial skepticism was well founded; pried loose from their linguistic matrix, some concepts lose too much of their original connotation.

Fortuitously, the four chapters Parsons translated were as close as we can come to Weber’s last words in social theory. The expansive world-historical perspective of the sociology of religion remained intact, copiously illustrated with historical examples, but now in The Theory of Social and Economic Organization there was a different ambition. These chapters offered something remarkably novel: a monumental edifice of ideal types of social action ranging from wholly formal and legal rationality to purely affective action and routine habituation, as Parsons remarked. Weber’s intellectual penchant for identifying diametrically opposed positions and extreme alternatives in order comparatively to set forth different institutional possibilities was on full display. Any evolutionary or developmental scheme that might have surfaced was dissolved in the proliferation of an apparently endless supply of pure types that could be used for empirical investigation and assessment of actual social structure and social organization. Moreover, the situation of social action was clarified: the individual was now confronted with possible choices for action and its consequences. The translation accomplished its goal: Weber’s work had acquired a new level of significance for general theory.

The roles played by Hans Gerth and Talcott Parsons and the extended arc of Weber’s gathering reputation and knowledge of his work brings us back to the third significant and somewhat dispersed grouping of scholars with a stake in the universities, the development of the social sciences, and the course of intellectual life in America: the interwar émigré generation of scholars and university professors, the “Weimar intellectuals” and exiles from Nazi Germany. They, too, had a part to play in the struggle over the mastery of Weber, the man many considered “the most important thinker in their lifetimes” who had “set the terms of debate” in the social sciences, citing the judgment of historians of the New School for Social Research. However, unlike the first two clusters of scholars discussed previously, the émigré community was hardly a cohesive grouping or network. The term cluster, implying minimal cohesion, could hardly apply. Because of its variety, dispersion, and internal tensions, this group must be approached as a complicated, multilayered, and contested patchwork of disparate and sometimes overlapping social and professional networks.

Viewed expansively, the emigration from Germany relative to the social sciences in the second, third, and fourth decades of the twentieth century actually spanned several academic generations, from Louis Wirth, who emigrated as a teenager in 1911, to one of his most important students at the University of Chicago, Reinhard Bendix, who arrived as a twenty-two year old undergraduate in 1938. But the more specific political term émigré concealed a variety of routes to American shores: a more-or-less voluntary decision to emigrate permanently under the pressure of events, forced (and perhaps temporary) exile, flight as a refugee, persecution as a Jew, or expulsion for political and ideological reasons by Nazi authorities after 1933. Whatever the individual motives and reasons, sometimes significant for social differentiation and status within the émigré community, it was most specifically those arriving in the 1930s from German-speaking Europe with careers already underway, thus suddenly disrupted and possibly ruined, who gave some sense of identity and “shared fate” to this multifaceted configuration. What they shared above all was the experience of displacement that Theodor Adorno referred to as the “damaged life.”

A sense of the nature of this disruption and the ambiguous feelings it provoked is revealed in an unusual way by one of the many postwar exchanges between Karl Jaspers, a Weber devotee, and Hannah Arendt. On April 19, 1950, two days before what would have been Max Weber’s eighty-sixth birthday, Jaspers had a dream at his home in exile in Basel. As he reported it in a letter to Arendt, “I had a remarkable dream last night. We were together at Max Weber’s. You, Hannah, arrived late, were warmly welcomed. The stairway led through a ravine. The apartment was Weber’s old one. He had just returned from a world trip, had brought back political documents and artworks, particularly from the Far East. He gave us some of them, you the best ones because you understood more of politics than I.” About to complete The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt replied, “Prompted by your dream I’ve read a lot of Max Weber. I felt so idiotically flattered by it that I was ashamed of myself. Weber’s intellectual sobriety [Nüchternheit] is impossible to match, at least for me.” She added the self-reflection, “With me there’s always something dogmatic left hanging around somewhere,” and then the parenthetical “(That’s what you get when Jews start writing history).”

In ways he could not have appreciated from his Swiss sanctuary, Jaspers’s intuition in the dream sequence proposed an unusual answer to the question, Why Weber in America? It evoked the archaic image of the mythic scholar-theoros, thrown into the alien world like the émigrés themselves, collecting and documenting, returning home as guide, mentor, observer of the unknown. The place assigned Weber lay deep within the intellectual milieu of the émigré community and what we might call the social psychology of the refugee scholar, the immigrant, and the exile in America. Weber and his work could thus function in two ways: both as a bridge to the new, to the world of capitalist modernity, and a road to an acceptable cosmopolitan “liberal” historical past, to the intellectual world Jaspers and many others had experienced in the Weber residence on the Ziegelhäuser Landstrasse in Heidelberg, the home built by Weber’s grandfather Fallenstein, the meeting place for Georg Gottfried Gervinus and the 1848 Frankfurt liberals, who had become by 1933 the outsiders, exiles, and outcasts of modern German history.

So it was Weber the cosmopolitan and self-described “outsider” who could give legitimacy and weight to the intellectual orientations and problems thought to be significant for the community in exile: the relations between politics and culture, the moral foundations of the social and economic order, the problem of “rationality” and the irrationality of action, the place for historical thinking or the “historical sensibility,” the “value” problem, the meaning of science as a vocation, the fate of the intellectual and the Jewish scholar. It was this Weber who could cushion the negative shock of what was often perceived as America’s “intellectual and cultural provincialism,” quoting Leo Lowenthal, and establish for the émigré scholar and intellectual the historical task of assisting in the development of American intellectual and cultural life. At the same time, the presence of a different Weber in America, already an established interest of scholars like Frank Knight, Talcott Parsons, and Edward Shils, created not just opportunities but difficulties for the European newcomers. The previous American reading and incorporation of Weber’s work had abstracted it from the contextualized and political Weber, the view of Weber as an “intellectual desperado,” that was so important to the émigré perspective. What would become of the work amid the contending strains of émigré thought and action?

As in Jaspers’s dream, Arendt had indeed arrived late—too late to answer this question. She never met Max Weber, only attending a few of the Heidelberg jours Marianne Weber continued to host into the 1920s and ’30s. But there were, of course, those from a more senior generation in this strikingly diverse community of émigré scholars who, like Jaspers, knew Weber personally, such as Emil Lederer at the New School, or Paul Honigsheim at Michigan State University, and Karl Löwenstein at the University of Massachusetts. There can be no doubt that their work and teaching was affected by the long shadow of Weber’s scholarship and personality, as they often acknowledged. Honigsheim is a perfect case in point, as his sociology of music is quite explicitly an extension of ideas generated in conversations with Weber. The Weber legacy obviously affected his life as a scholar and teacher in every question he pursued and in his very demeanor with students in seminars and in the classroom. Others, such as Alfred Schutz, Albert Salomon, or Arnold Brecht at the New School, had read Weber’s work and then used it for their own purposes—Schutz in phenomenology and Brecht in political theory. They also published work expounding, interpreting, or appropriating some of Weber’s ideas, always taking for granted the politicoeconomic dimension of his work. Salomon had already published on Weber in Germany, characterizing him somewhat misleadingly as the “bourgeois Marx,” a phrase that resonated in certain quarters for decades. Among his New School peers the characterization was important because it provided a kind of intellectual connection to Weber for those such as Franz Neumann, Otto Kirchheimer, and even Lederer, whose critical neo-Marxist outlook had traveled with them across the Atlantic, typically becoming modified during the exile years. In the United States Salomon’s authoritative introductory essays on Weber, published in the first two volumes of Social Research, reveal his earlier command of the philosophical and sociological underpinnings of Weber’s work but now expand the scope to the entire range of issues confronting the social sciences, as if to say, If one wants to participate in the theoretical discourse of the modern social sciences, Weber’s work is the place to begin.

In the empirical studies of the New School faculty it is characteristic that when Weber is actually cited it tends to be the Weber of political economy or political sociology who is credited with an insight. This is no less true of Franz Neumann in his masterwork Behemoth, although his affiliation with the Institute of Social Research often put him at odds with New School intellectuals. Even émigré scholars as far apart in basic orientation as Paul Lazarsfeld and Theodor Adorno allow similar parts of Weber’s work as an inspiration. Among the faculty’s larger monograph-length research projects, Frieda Wunderlich’s late publication on the German agrarian economy shows its debt to Weber’s earliest studies on the nineteenth-century agrarian economy of Germany east of the Elbe. But as an “institutional” economist working with ideal types and a typology of rational action instead of formal models of marginal utility or mathematical models of choice, Weber had little effect on the emerging field of economic theory and the work of the professional economists, figures like Ludwig von Mises, Albert Hirschman, or Oskar Morgenstern.

Beyond the walls of the New School there were still other scholars, such as Melchoir Palyi at Southern Illinois University, Arthur Salz at Ohio State University, Erich Voegelin at the University of Alabama, or Leo Strauss at the University of Chicago who were well-versed in Weber’s thought. For Voegelin and Strauss the response to Weber’s work ranged from ambivalence to hostility. Voegelin, a Laura Spelman Rockefeller Fellow in the United States from 1924 to 1927, part of the time at the University of Wisconsin, had published an earlier positive discussion of Weber before his emigration. In The New Science of Politics (1952), however, he went on the offensive against social science, anticipating Strauss’s well-known attack on Weber in Natural Right and History (1953). Strauss’s views should be read in the context of the University of Chicago social science curriculum favored by Knight and Shils. His critique became generalized in a standpoint juxtaposing “social science” or simply “the social” with “political philosophy,” a reification of positions also found in Voegelin’s work, and in a highly individual and novel version modified by “existentialist” concerns in Hannah Arendt as well. Arendt thought Voegelin’s book was “on the wrong track, but important nonetheless. The first fundamental discussion of the real problem since Max Weber”, and she summarized her opinion of Strauss: “He is a convinced orthodox atheist. Very odd. A truly gifted intellect. I don’t like him”—a sentiment reciprocated by Strauss and his followers in this frequently contentious environment.

Conflict and hostility is sometimes the stuff of social life, now and then with interesting consequences. In the émigré community there was also what could be called a Weber “nonreception” in the 1930s, worth taking into account because of subsequent developments in postwar American intellectual life. In New York the configuration was evident early in the sometimes uncomfortable institutional (and personal) relationships among the three intellectual centers: Columbia University, the New School for Social Research, and the Institute of Social Research transported to Manhattan from Frankfurt. Edward Shils captured the essence of this situation in his inimitable politically charged style, commenting from a distance of four decades on the year he spent in the city, affiliated with Columbia. At the New School, he noted, “was a rather nice lot of refined liberal and social-democratic Germans, very unfanatical, cultivated and very pleasant to get on with” who knew Weber’s work well. On the other hand, uptown in Morningside Heights he found the “Frankfurt gang,” as he called them,

a very mean lot: terribly edel, radical, cliquish, self-promoting. They were spreading as well as they could their pernicious Kritische Philosophie, i.e., fancied-up Marxism. I used to go to their seminars at 429 West 117th Street. I never heard Max Weber mentioned there in the year 1937–38, and I cannot recall any of them writing about Weber.… Horkheimer had no interest in Weber, nor did Marcuse, nor Adorno, nor Pollock. Even Wittfogel, who was then one of them, and thus very close to communism, did not pay attention to Weber in his Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft Chinas (1927). At least, I don’t think so.

One can imagine Shils’s hyperawareness of the names “Weber” and “Weberian,” as this was the year in which, having just emerged from Knight’s Weber seminar at Chicago, he was committing a good deal of attention to a similar seminar with Schelting at Columbia, the context for their initial efforts to translate the first chapter of Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft.

Neither by temperament nor inclination could Shils have bridged the divide separating these three institutions and groups of scholars. Toward the end of the decade Franz Neumann and Otto Kirchheimer performed that function to some extent, as did Paul Lazarsfeld from an autonomous position in his Bureau for Applied Social Research. Even though he thought of himself as a “European positivist,” Lazarsfeld by the late 1930s was actually closely involved in the “empirical” work of the institute, then moving himself and his restructured bureau to Columbia. He also knew Weber’s concept of action and his empirical work, giving it credit for some of his own interests.

The reality of the relationship vis-à-vis Weber’s writings and reputation was of course much more complicated than Shils’s acerbic portrayal suggests. Furthermore, the situation within the émigré groups changed somewhat over the years. Memories faded of Weber as the “bourgeois Marx” in the European context and they were replaced even in the same minds by a Weber retooled for the social sciences in the New World. Furthermore, some “elective affinities” concerning historical and comparative perspectives emerged in the American environment of the kind that Bendix recalled in his own experience. Building on such affinities, Franz Neumann even thematized the vocation of the émigré scholar—namely, bringing to bear hard-earned historical perspective and theoretical grounding on the dangers lurking in the American outlook, as reflected in the social sciences: too much optimism about an ability to change the world, too much faith in the self-justifying value of collecting raw empirical data, and too much eagerness in pursuit of the kind of financial support that compromises intellectual integrity and independence. What the American experience offered, in return, was a bracing pragmatic lesson in reconciling or tempering theory with experience, a perfect point of entry for the fascination with Weber. As for Weber’s work itself, Franz Neumann’s judgment was prescient: “It is characteristic of German social science that it virtually destroyed Weber by almost exclusive concentration upon the discussion of his methodology. Neither his demand for empirical studies nor his insistence upon the responsibility of the scholar to society were heeded. It is here, in the United States, that Weber really came to life.” For Neumann it was as if, in the land of Benjamin Franklin and William James, Weber’s thirst for empirical and intellectual sobriety, his Sachlichkeit, had found a home.

It should not be surprising that the wide range of scholarship and opinion among the émigrés and their dispersion across the vast landscape of American intellectual life produced an exceptionally complex intellectual, social, and institutional history. Notwithstanding their sometimes marginal status or the less prestigious standing of institutions such as the New School, it is nevertheless important to stress that over time the scholars in exile added a new dimension to the understanding of Weber’s work and to interest in it. Their concerns and their uses of Weber spilled over to a variety of institutionalized settings, as developments in the immediate postwar years illustrate.

One such setting was the organized discussions at Columbia University. The faculty Seminar on the State offered an important instance of the new postwar uses of Weber’s thought across different social science disciplines. Franz Neumann had joined the Columbia faculty in political science, and joined by Karl Wittfogel from the émigrés, along with Robert Merton and others, he participated in this important interdisciplinary seminar, a gathering later attended by C. Wright Mills, Daniel Bell, S. M. Lipset, David Truman, Richard Hofstadter, and Peter Gay. The émigrés had merged into the mainstream of American academia. As evidence of the way some of Weber’s ideas permeated the environment, it should be noted that by 1946 in the minutes of the Seminar’s biweekly discussions, it is commonplace to find Weber’s work on rational-legal authority and bureaucratic forms of organization serving as a shared point of departure and framework for analysis. Knowledge of Weber’s ideas from Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, just starting to appear in translation, became a common point of reference for participants. Contrasting positions on the bureaucratic rationalization of the state, past and present, East and West, democratic and authoritarian, were even articulated through commentary on Weber. The problems in these discussions had to do not with the interpretation of Weber’s work as such but with particular issues such as the workings of bureaucracy in the Soviet Union, for which Weber’s writings simply offered useful guidance and a compelling theoretical perspective.

The discourse of the Columbia Seminar on the State can be regarded as typical: the use of Weber’s work as a mode of argumentation, as a text for articulating, clarifying, and distinguishing one’s own interpretive and theoretical position. It was increasingly this use of Weber, addressing contested topics not his own, that as much as anything helped create social “carriers” for his ideas and intellectual environments in which those ideas could be restated, criticized, reinterpreted, and thus renewed.

The substantial body of translations principally considered here—namely, Parsons’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Gerth and Mills’s From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, and Parsons’s The Theory of Social and Economic Organization—became the basis for the postwar permeation of Weber’s work into the social sciences, and especially into the subfield specializations of sociology. To these we can add the three essays from Weber’s philosophy of science, the Wissenschaftslehre, published finally by Edward Shils with Henry Finch as The Methodology of the Social Sciences (1949), a supplemental text that was poorly edited. Some of its neologisms, such as the woolly “ethical neutrality” for the more precise Wertfreiheit, have bedeviled discussions ever since and obscured the intention behind Weber’s insistence that moral indifference has nothing whatsoever to do with the ideals of rational criticism and “intersubjectivity” in science. Only a few perspicacious thinkers at the periphery, such as Maurice Merleau-Ponty, have understood the existential and intellectual demands this kind of “freedom” imposes.

In the universities by the end of the 1950s, Weber’s texts had become standard fare in the sociology of religion, political sociology, studies of bureaucracy and organization, investigations of inequality and social stratification, the comparative historical analysis of social institutions, and the discussions of modernization. This diffusion of the work in sociology was only part of the story, however, for in terms of the major social science disciplines Weber’s ideas were also introduced in the same period into political science, cultural anthropology, and some areas of history, philosophy, and the humanities. They became part of the contentious disputes over “positivism,” the so-called Positivismusstreit, and the philosophical, methodological, and political debate over “value judgments” and “objectivity” in science that was gathering energy by the early 1960s. At the same time it was this somewhat improbable translation, reading, and propagation of Weber’s work in America rather than in Europe—as noted recently by Uta Gerhardt—that then made possible Weber’s equally improbable and surprising return to his place of origin. Having kept the flame burning in North America, scholars like Parsons and Bendix, even Horkheimer and Adorno, along with many others, would live to see it transported back to Germany, though not under conditions any of them might have chosen.

Nearly half a century has passed since the three conferences held on both sides of the Atlantic in 1964 to commemorate the centennial of Max Weber’s birth: those of the Midwest Sociological Society in Kansas City, the International Sociological Association in Montreal, and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie in Heidelberg. Reviewing these proceedings today, especially those in Heidelberg, is like entering the superheated, misty cultural and ideological battlefields of the 1960s, with Weber and his work serving as a stand-in for conflicting positions, agendas, and accusations, some of them from a past that was refusing to pass. These conferences represented a kind of caesura in the recovery and reconstruction of Weber’s thought. They brought into sharp focus a number of issues in the social sciences, the academic disciplines, and the universities that had concerned Weber and received attention in some of his most important texts, such as “Science as a Vocation” and “Politics as a Vocation”: the duties of the teacher and scholar; the critical assessment of political and economic power; the social and cultural effects of capitalism; the uses of scientific inquiry and human reason in an age dominated by big science, vast bureaucracies, and impersonal market forces; the prospects for social justice or socialism; and our responsibility for history. In the most visible venues, however, these issues played out as a hostile face-off between competing intellectual orientations, with orthodox “Weberians” on the one side, such as Parsons and Bendix, and proponents of a “critical theory,” such as Adorno and Marcuse, on the other. Protagonists like Raymond Aron seemed caught between contending parties in the querelles allemandes.

In the decades since then the underlying issues connected to Weber’s thought have never entirely vanished, and those defined by the problem of “rationality” and the “most fateful force in our modern life, capitalism,” have returned with a vengeance in the first decade of the twenty-first century. But from the perspective of the present, as the abbreviated twentieth century from 1914 to 1991 has come to a close, such fundamental and enduring themes have been joined by an eclectic mix of preoccupations conditioned by numerous intellectual, cultural, and political factors, including the decline of Parsons and Shils’s general theory of action, the demise of structural functionalism in the social sciences, the collapse of Marxism, the “cultural” turn in the social sciences and humanities, the end of the Cold War and its accompanying realignments, and the social tensions and confusions of the most recent fin de siècle. In the rush into our current century only a few monuments and points of reference from the mid-twentieth century have been left standing; Weber’s thought is one of them.

Figure 13. Talcott Parsons later in life in his Harvard University study, the battles in the 1960s over Weber’s legacy and the seriousness of the times etched on his countenance. Harvard University Archives, call # UAV 605.295.7, Box 3. Reproduced by permission.

Taking stock of what remains has assumed different forms. Weber’s work as a whole has at last come under scrutiny, with the laborious compilation and editing in Germany of the authoritative collected works as a critical edition, the Max Weber Gesamtausgabe, accompanied by a gold mine of unpublished correspondence and cultural landmarks from the still poorly understood Wilhelmine era. With this effort the opportunities for historical and biographical contextualization have expanded enormously. Itself a product of Cold War competition, the Max Weber Gesamtausgabe has outlived the reasons for its birth to open vistas onto deeper and richer prospects for comprehending the biography of the work.

In the academic disciplines the emphasis has often been on assimilating the work, extending it in different directions, and applying it to a startling range of contemporary problems, such as those encountered in the application of law, the administration of justice, the formation of institutions in the European Union, the operations of the modern corporation, the nature of “rationality” in modern market capitalism, the character of modernizing regimes in the developing world, or the problems of the modern habitus and living in a “disenchanted” world. Among these newer interpretations, the stylish apotheosis of the Weberian thesis of disenchantment—the phenomenonal world has become rationalized, calculable, denuded of magical and mysterious forces—and its mirror image, the promise of “reenchantment,” is a telling case in point. The specification of the “disenchanted” condition and the ensuing discussion plays out as an affirmation, argument, elaboration, explication, extension, amplification, critique, or denial of the viewpoint Weber enunciated.

Judging from numerous collections of articles that have appeared over the past decade, there has also been considerable attention directed toward specifying the basic features not just of Weber’s work but of the “Weberian” outlook or position in social theory. In America, sociological theory may still figure as the “ground zero” for such disputations, but elsewhere the conversations have migrated beyond porous disciplinary boundaries to a generalized interest in “social theory” wherever it appears. The rediscovered author has now come of age and spawned a movement of thought, an adjective before the noun, a perspective or theoretical approach, or in the words of one prominent group of scholars, a “research program” or “paradigm.”

What can Weberian “theory” or a Weberian “research program,” “paradigm” or “perspective” possibly signify? It would be an exaggeration to maintain that general agreement has been achieved on answering such a question, or that consensus exists even on the very project of abstracting a “Weberian theory” from Weber’s incomplete, exploratory, and unsystematic writings. One of the attractions and strengths of the work has always been its unrivaled scope, variety, and indeterminacy. But the contours of an emergent perspective, if not the precise contents, have become discernable amid the recent out-pouring of books, articles, collections, and commentaries. To delineate these contours is to synthesize and condense dramatically the underlying structure of Weber’s thinking—which is by its nature, we should not forget, always problem-oriented rather than oriented toward articulating a general “theory” or specifying a methodological position.

With this caveat in mind, for those in search of “theory” it seems self-evident that Weber’s central questions were always directed toward investigating developmental dynamics and understanding their consequences for the conduct of life in different sociohistorical contexts. In his work such questioning is indeed obsessive and singular. Viewed through the lens of an expository synthesis, such as that proposed by M. Rainer Lepsius, Weberian investigations thus can be thought of as displaying an interest in “dynamic processes”—that is, developmental dynamics driven by conflicting social forces that are open-ended in terms of type, duration, pace, direction, and consequences. Following Weber’s lead, developmental dynamics can be conceptualized in terms of a three-part relationship among structure, action, and meaning, to use the terminology of the moment in the social sciences. Stated somewhat more elaborately, Weberian analysis is thought to be concerned with three central problems and their relationship: the problem of the external structure or material form in which action occurs; the problem of the rationality of action and association, or the forming of social relationships; and the problem of cultural “meanings” and “significance,” including the meaning of action for both subjects and observers. This tripartite orientation seems to emerge even in the opening sections of Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft.

From the perspective of theory and the elusive “research program” or “paradigm,” to state the matter in this way is important, for it suggests that Weber’s work bridges the analytic approaches in the social sciences that are often proposed as alternatives: the structural, the institutional, the rational action or action-oriented, and the cultural modes of inquiry. Furthermore, it now becomes possible to point out that in the Weberian view the relationship among the three problem complexes is worked out at different levels of analysis: at the individual level of the actor and action orientations, at the social level of associations, institutions, and organizations; and at the cultural level of legitimation processes and disputes over “values” and the “normative” order. The entire sociology of legitimate authority or domination is filled with such variations. No single problem complex or level of analysis can claim logical priority either, for to do so would be to prejudge the relationships any investigation aims to reveal. This insistence on a configurational, “multicausal” and “multilevel” analysis, using the language of contemporary social science, amounts to a recommendation always to search for the unique particulars and the differences in any configuration of events, the “combination” or “concatenation of circumstances” Weber referenced that accounts for large-scale sociohistorical transformation.

Summarized in this way and abstracted from its concrete problematics, the Weberian project thus has been shown to be capable of suggesting modes of analysis and paths of investigation applicable to the most varied problems and problem complexes. In this view the extension of the conceptual language—from asceticism to Zweckrationalität, so to speak—is constrained only by the investigator’s imagination. From such a perspective, completing the process Parsons set in motion, Weber’s work has thus become an authoritative voice not only in the settled domains of sociology and other established social sciences, but also in the rarified atmosphere of “social theory” with all its exotic possibilities and alternatives, from the reflections of George Herbert Mead to the inquiries of Pierre Bourdieu. The identity of the “Weberian” theory, research program, or perspective has finally come of age.

Setting forth such a general and abstract claim can be intellectually satisfying. It encourages us to recognize that Max Weber did achieve an intellectual synthesis, as Parsons maintained, though not a synthesis of concepts and categories confined solely to the general theory of action. It was rather a complex synthesis formed from combining structural and institutional analysis, notions of rationality, propositions about social action, awareness of cultural particularities, and a deep appreciation for historical inquiry and evidence, or as Weber wrote in the final sentence of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, a single-minded pursuit of that elusive construction, “historical truth.” Such a synthesis was justified not by its stand-alone generality as theory but by its heuristic promise in grasping and clarifying significant puzzles, problems, and questions about the phenomena of the social and historical world. The synthesis was brought to life by its nuanced qualities, varied applications, and problem-centered specificity, not by its drive toward systematicity.

Notwithstanding their elegance, the efforts to recast Weber’s work as canonical for the social sciences and central to its current agendas must always remain radically incomplete, for it fails to capture the new edges of excitement and agitation that will always grip those kinds of inquiry notable not for their well-defended paradigms but for their “eternal youthfulness,” to borrow Weber’s suggestive phrase.

The recent struggle for the mastery of Weber has charted a double course. One direction has seen an expansion of the horizon for Weber’s ideas beyond the boundaries of sociology to the commanding vistas of the Western philosophical and political tradition, of which modern sociology is but one constituent element. From these heights of thought the partners in conversation for Weber are not so much Parsons and Mills but figures like Thucydides, Plato, Aristotle, Niccolò Machiavelli, Immanuel Kant, G.W.F. Hegel, Alexis de Tocqueville, Karl Marx, John Stuart Mill, and Friedrich Nietzsche, as well as the entire tradition of civic republicanism, liberalism, and liberal democratic thought. In this view Weber arrives very late, coming at the end of more than two millennia of reflection on matters of civic and philosophical import. The lessons of the Western tradition concerning ethics and politics receive a trenchant summation in his most consequential, penetrating, and socially engaged writing. The work circles back to the starting points in antiquity, retrieving the questions about what we should do and how we should live, though posed now in a radically different rationalized and disenchanted modern world that demands novel, complex, honest, and often unsettling answers.

The spirit animating this perspective has encouraged a subtle reorientation, a shift in focus toward Weber’s preoccupation with the human condition, with “statecraft and soulcraft.” If we ask what were Weber’s deepest concerns, then the answer from this standpoint is, in a phrase, the formation of the personality and character of the individual within the different orders of life. The Weberian concepts of Lebensführung and Lebensordnung, of “conduct of life” and the “orders of life,” are elevated to the status of master concepts. The concentrated synthesis of ideas from the sociology of religion, the highly charged “Zwischenbetrachtung,” or “Intermediate Reflection,” which Gerth and Mills retitled “Religious Rejections of the World and Their Direction,” becomes the master text, drawing together the scattered strands of Weber’s thought. It offers an unusual adventure of the mind: a guided tour, complete with historical illustrations and comparisons, through the practices of the self in Western civilization.

Weber’s relationship to predecessors in the Western tradition plays out thematically in his emphasis on the importance of moral and political judgment, the ethic of responsibility, the interaction between charisma and political education, the institutions for cultivating citizenship, and the creation of an active civil society through the power of association—precisely the themes of his American journey. The emphasis could be seen as a singular “preoccupation with ethical characterology and public citizenship in a modern mass democracy,” as an effort to retrieve the classical political tradition and breathe new life into the practice of what Machiavelli used to call civic virtù. This particular Weberian project is indeed deeply enmeshed in the political and philosophical traditions of Western thought, a reminder in the biography of the work of Weber’s admiration for the thinkers of Greek antiquity and his attraction to Rome and attachments to the civilization of the Renaissance in Italy.

The other direction in the encounter with Weber recapitulates in a very different world and under quite different circumstances the kind of enthusiasms experienced by readers like the young Talcott Parsons and Edward Shils, for today Weber’s thought has traveled beyond American sociology to other perspectives, social contexts, and modes of thought, pressing against the boundaries of the recognized disciplines. The Americanized Weber of the founding clusters of scholars in the social sciences has given way to an international dialogue of impressive scope, ranging far beyond American shores to Eastern Europe, Russia, Spain, Latin America, the Middle East, China, Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. This surprising journey of a body of thought has occurred not merely because Weber wrote in an original idiom, or because his subjects actually were the various cultures, religions, and economies of the world, East and West, but because the grammar, concepts and problematic of the thought continue to capture the drama of the times and to inspire a response. The light of the great cultural problems may have moved on, but Weber’s thought has moved with them.

Of the great cultural problems, one continues to remain central and to connect us to the past: the rationalization processes in the life orders of the world, to use Weber’s formulation—or, in more informal terms, the problem of “modernization” and the inescapable conflict between traditionalism and the forces of the modern world, the very heart of Weber’s problematic in numerous texts, including especially The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Thus, when Weber’s ideas appear amid debates in a country like contemporary Iran, it is not surprising to find the question of “legitimate domination” raised with reference to “patrimonialism,” a traditional type of rule salient there and missing or obscured elsewhere. Or when the issue is the creation of “social capital” and the relationship between civil society and the state, whether in Lithuania or Korea, Weber’s commentaries about associational life can offer a clarifying perspective and a way of confronting the conflicts caused by the grinding forces of the modern world of rationalization, especially in societies experiencing jarring dislocations and social transformations.

Nowhere has the dynamic effect of reading Weber been more evident than in Japan, where an independent reception of the work has been in progress dating from the era of Knight and Parsons. (In China, by contrast, the encounter with Weber’s work is recent, relying almost entirely not on the original texts, but on the English-language translations transcribed into Chinese.) The Japanese fascination with Weber has a compelling explanation, for in the words of one authority, the deep and lasting impact of Weber’s writings

since the 1920s should be ascribed to the fact that a large segment of social and cultural science has interpreted the modern history of Japanese society as a special case of partial modernization or, in Weberian terms, of partial rationalization. In Weber’s work scholars encountered in ideal-typical form the autonomous development of personality in civil society. They took this model out of its cultural context and applied it as a method and value to the analysis of Japanese society … and the Asian world … For Japanese “modernists” (kindaishugisha) Weber’s work and person showed a path out of the magic garden of religious and political salvation doctrines and let them see with new eyes the world from which they came and which they entered.

This different reading of Weber has little to do with a program of research, instead revealing a much more urgent search for an orientation to the world, for knowledge of how to act and what to do. In this respect it shares an aspect of the effort to place Weber’s thought within the Western political and philosophical tradition.

Max Weber in Japan offers a kind of template. The experience of Japan’s opening to the West—that is, to the forces of “rationalization” or “modernization”—continues to be repeated everywhere. There is no escape, and there are no exceptions. It is always a journey from the magical, romanticized past to the rationalized, disenchanted present and future, from the poetic to the prosaic. As in the Indian Territory of 1904, so in other times, places, and cultures: with lightening speed everything standing in the way of capitalist culture is swept aside. Then as now, the question always becomes, How will individuals respond, and how will a society and a culture adapt to the new forces unleashed by the modern project?

Weber’s work will continue to resonate in those times and places where the encounter with rationalization persists and the stresses of the transformation of tradition are keenly felt, for the work is attuned not only to the dynamics of rationalization but also to the range and types of possible responses, the allure of all manner of escape routes from the aporias of modernity: mastery of the world; flight from the world; reconciliation with opposed forces; quiescent surrender to fate; revival of old beliefs; return to venerated traditions; escape into aestheticism, intellectualism, eroticism, or some other solipsistic way of leading one’s life; transcendence through the power of the extraordinary, through charisma; the call of “revolution.” The possibilities are always renewable; there can be no final accounting of the all-too-human search for alternatives.

Max Weber in America—the journey and the dissemination of the work—contributed to launching multiple projects that are still underway and far from complete. It is thus worth remembering that the attention given to Weber’s writings and to matters Weberian will continue to depend, as it always has, upon the richness, brilliance, complexity, and open-ended quality of the thought. The context and audience for reading the work may change, but the confusions of the present will always remain, addressed in a bewildering variety of ways. In such circumstances one of the most fruitful and compelling choices continues to be, as it has been in the past, the fresh encounter with the work itself. Only in that way can the thought remain alive, connected to the great cultural problems of the times, and capable of renewal.