Max and Marianne Weber left Heidelberg on August 17, 1904, and they returned home by train through Paris after docking at Cherbourg, France, on November 27—a journey of over three months. The Atlantic passage to the United States was aboard the Bremen of North German Lloyd, a 10.5-thousand-ton vessel built in Gdansk (Danzig) that departed from Bremerhaven, Germany, on Saturday, August 20, and proceeded to Southampton, England, for additional passengers. The ship was sighted south of Fire Island as it approached New York’s Ellis Island the evening of August 29, according to the New York Times. Passengers disembarked the following day. The Atlantic voyage took a normal 8 days, but it was well short of the record of exactly 5 days, 11 hours, and 54 minutes held by the luxury liner Deutschland. The Bremen continued its Germany–to–New York service until the outbreak of war in 1914, and after the war flew the British flag as reparations under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

Thanks to the diligence of archivists for the Ellis Island Foundation, the ship’s manifest for the Webers’ 1904 passage is available on the Internet. The manifest lists 1,679 passengers, nearly 60 percent of them immigrants from Russia and the Hapsburg lands of central and eastern Europe, including the provinces that now comprise Poland. A majority of the men and women were under twenty-five, and many were Jewish (“Hebrew” in the code of the immigration statutes), crowded into third-class steerage and the lower decks. In her letters home Marianne accurately reported five hundred Jewish immigrants. Of the other passengers, numerous German and other European travelers were headed to the International Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri. Among them were the impressionist painter Max Schlichting, who exhibited an oil painting, Strandvergnügen (Pleasures of the Beach), at St. Louis; and Professor Guido Biagi, the royal librarian in Florence, who spoke at the Congress of Arts and Science on the library as an institution of learning. Marianne noted that Schlichting, an influential member of the Kunstgenossenschaft (art association) who had affiliated earlier with the Berlin Secession, had been sent to the exposition by the German government to observe and serve as an art jurist, an important political appointment. On the first day at sea he introduced himself to Max Weber. Having just published a tract on art and the state, Staat und Kunst, that attacked his former associates in the secession and defended the official call for a “unified” presentation of German art, Schlichting’s apologetics apparently allowed him to slip through the screen of court-sanctioned disapproval of modern styles in painting. To my knowledge he was the only (former) secessionist to present his work in St. Louis. One can only wonder how his ambivalent double role would have appeared to Weber, who became increasingly critical of the strident and crude antimodern cultural policies and pronouncements of Kaiser Wilhelm II.

The names of Schlichting and Max and Marianne Weber and their traveling companion Ernst Troeltsch appear late in the complete manifest for the Bremen as passengers 1638 and 1647 to 1649, respectively. Max is amusingly misidentified as a clergyman, a title probably intended for Troeltsch. Perhaps he looked the part. Their Atlantic passage had gone well, without seasickness, Max eating his way through the lavish menu, to Marianne’s distress. She noted they were seated at dinner with two American women schoolteachers, one of whom was probably a Chicagoan named Ida Pahlman, who were glad to assist with their English. But Marianne saved her longest substantive comment for one of the enduring social policy issues that would weave in and out of their travels: immigration. It was an obvious concern, considering the circumstances on board. Having observed the cramped quarters of the eastern European immigrants, pressed together “like sheep on the heath,” she noted that the relative cost of the Atlantic crossing meant the privileged few actually lived at the expense of others—“really dreadful,” she complained, and “it should be given public attention” (August 24; MWP). The struggles of immigrants and the substandard living conditions in immigrant communities was receiving attention in some quarters in the United States, as she would soon discover.

The pattern of post–Civil War immigration should be well known, especially for New York, as it was the major port of entry and destination for many immigrant groups. By 1904 legal immigration into the United States exceeded 800 thousand people annually, topping a million for the first time the following year. The large numbers recorded in the decade before 1914 would not be seen again until the end of the twentieth century. For the five boroughs of New York City itself, approaching four million in 1904, the foreign-born percentage of the population was headed to an estimated high of 40 percent by 1910. (In recent decades the metropolitan area has once again approached such percentages.) By 1900 the surge in German and Irish immigrants had begun to subside, to be replaced by the wave of new immigrants from central, eastern, and southern Europe—Hapsburg territory, the Russian Empire, and Italy. Of the 8.2 million immigrants entering in the first decade of the twentieth century, two-thirds came from these locations in Europe. Among them were Jewish immigrants, estimated at about 950 thousand over the decade in one official report from the 1910 census. Many settled on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, served there by settlement houses and social workers the Webers would visit in November 1904.

The Webers stayed in New York City twice: upon arrival for about five days with Ernst Troeltsch at the Astor House on Broadway, then for a more intensive and consequential two weeks at the end of their travels. The weeks in November were reserved for some serious work, observations of numerous urban institutions, and a fast-paced social schedule. By contrast, the days on arrival offered little more than a whirlwind of first impressions: the ethnic and economic contrasts of the city, the crush of different nationalities, the mansions of the wealthy along Fifth Avenue, the noise and poor condition of city streets (confirming the warning in the Baedeker guide), the oasis of calm in Frederick Law Olmsted’s Central Park (duly noted by the Webers as a reminder of Berlin’s Tiergarten), the celebrated Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, and the Wall Street stock exchange. This last location was considered a tourist destination at the time, though it would have attracted Weber’s professional interest in any case, since he had published a few hundred pages explaining to a skeptical German public the rationale and inner workings of stock and commodities exchanges, including the futures market. He also had served in 1896 as an academic expert on the German Ministry of the Interior’s thirty-member Committee on the Stock Exchange. The transcript of the committee’s sessions shows his acute awareness of the operation of other exchanges in Europe and North America,—particularly the emerging futures market. The stop on Wall Street was an imperative: it gave him a firsthand look at one of the famous institutions of modern market capitalism.

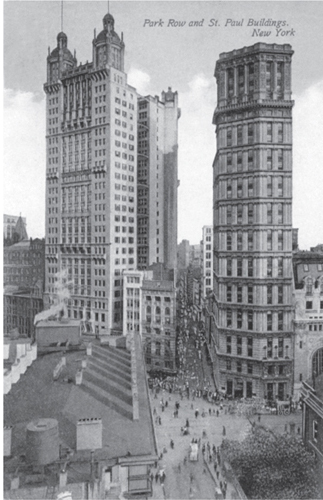

If the popular imagination of the time represented America in visible monuments, then it surely found them in the Brooklyn Bridge and the steel-frame urban skyscrapers, a distinctive new American architectural innovation and style of building. Crossing the East River, the Webers commented on the “painterly” vistas, with Max juxtaposing the impressions left by the bridge and its masses of humanity in motion with the views from a distance of the “fortresses of capital” on lower Manhattan, reminiscent of the towers of the grandi in the medieval Italian cities. Directly across from their hotel stood the St. Paul Building and the thirty-story Park Row Building, the latter recognized by Baedeker and praised by King’s Views of New York City as “the tallest structure of its kind in the world.” “Ground rent drives buildings into the heights” was Max’s dictum. Marianne captured the mood, writing, “Two of the powerful ‘beasts,’ 30-story ‘skyscrapers,’ arise directly across from us. One must see them to believe they are real. I still ask myself whether they are simply dreadful, grotesque and showy, or whether they display their own beauty and dignity. In any case, like the tower of Babel, they nullify everything else in the vicinity, such as the little church [St. Paul’s Chapel] with its gothic tower that tries to assert itself like an island of peace amid the untamed din of the streets” (September 2; MWP). Today the curious traveler can still judge for herself the outcome of this face-off between spiritual “culture” and materialistic “capitalism.” Taking sides in the debate, for his part Max announced that the new imposing structures stood beyond the usual categories of aesthetic judgment. They were symbols of a new kind of American sublime.

Figure 1. A postcard of New York City from the era shows the view across Broadway of the Park Row and St. Paul skyscrapers that provoked Marianne Weber’s ambivalent comments about the “powerful beasts directly across from us” and Max Weber’s quip about the “fortresses of capitalism.” Courtesy Archive of American Architecture.

The main encounters with American university and college life were to come later in the trip, though they began right away in September in conversations with Professor and Mrs. William Hervey. A Columbia University Germanist educated in Leipzig, Hervey with his wife provided a brief introduction to the political economy of academic life in the metropolis: small apartments, cramped offices, high rents, time-consuming commutes, expensive shopping, difficulty finding satisfactory domestic help, general constraints on “individualism” in everyday life. Little has changed in a century.

As for the traveling companions, in these first few days Weber established a reputation for being one step ahead of everyone, “until now better than ever since his illness” Marianne observed, an enthusiast in pursuit of the new, distinctive, and unusual. His complaints were reserved for those, like Troeltsch, who instead of engaging with the new experience quickly found “the outward symbols of the American spirit antipathetic and repulsive” in the words of Marianne’s reporting. The spirit of adventure set Weber apart from Troeltsch and other colleagues, such as Werner Sombart, and contributed importantly to the range of his personal contacts, the depth of his inquiries into the details of American life, and the sheer variety in his itinerary.

Following the first days in Manhattan, the threesome boarded a Pullman car for the trip up the Hudson Valley to Albany and on to Buffalo. Alert to the abrupt change of environment, Marianne commented that the natural spectacle “awakened completely new feelings about the new world,” as if revealing the unspoiled edenic landscape celebrated by the nineteenth-century Hudson River painters. The immediate goal for seeing the power of nature, of course, was Niagara Falls, almost an obligatory pilgrimage for the European traveler. Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont had stopped there in August 1831, donning rain gear for a dangerous exploration behind the falls. But there was another, more important destination: the German immigrant community in North Tonawanda at the terminus of the Erie Canal.

The Webers’ correspondence from North Tonawanda and Niagara Falls, where they stayed in Andreas Kaltenbach’s hotel, contains a surprising amount of detail. In her account Marianne chose to include only a few sentences from Max’s commentary, emphasizing the stark contrast between the urban metropolis they had just left behind and the modest wood-frame single-family homes of the immigrant community of about ten thousand they visited in North Tonawanda. But more was at stake than the obvious differences between the cosmopolitan metropolis and smalltown America.

First of all, the traveling party expanded to include three more university colleagues. At Niagara Falls they were joined by the Erlangen philosopher Paul Hensel, who had arrived in New York two weeks earlier, also bound for St. Louis, where he would deliver a lecture titled “Problems of Ethics.” Johannes E. Conrad, a professor of economics and then rector at the University of Halle, was also in town visiting his daughter and son-in-law, Margarethe and Hans Haupt, before continuing to St. Louis. As a prominent representative of the Historical School of economics, Conrad presented a paper at the Congress of Arts and Science titled “Economic History in Relation to Kindred Sciences.” Weber knew both scholars; indeed, some of his important early contributions to political economy, including handbook articles about the stock exchange, had been published by Conrad as editor of the Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik and the Handwörterbuch der Staatswissenschaften.

In his later reconstruction of this particular episode, Hans Rollmann has mentioned these professional connections, deftly using the alternative perspective provided by Ernst Troeltsch’s travel letters to his wife Marta. However, the circle needs to be completed, for it also included the American economist and educator, Edmund J. James, and his German-born wife and two university-age sons, both fluent in German. The James and Haupt families had known each other for years, starting in Germany. Graduating from Harvard University, James had gone on to study in Berlin and Halle, completing his doctorate under Conrad in 1877. In Halle he also had met and married Anna Lange, the daughter of a Lutheran pastor. Having taught already at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and at the University of Chicago, James had advanced quickly through the academic ranks, founding the American Academy of Political and Social Science and editing its Annals, among many other accomplishments, and then advancing to the presidency of Northwestern University. In these days in upstate New York he was in the process of accepting an offer to become president of the University of Illinois (at a salary of $8000.) James was a well-known figure in the founding generation of American economists—many of them, such as Richard Ely and Edwin R. A. Seligman, educated like James in Germany. Weber thus found himself not only in a German immigrant community with colleagues from home but also in the company of an influential educator, political economist, university president, and one of the founders of the American Economic Association.

In North Tonawanda, Hans Haupt was pastor for the German Evangelical and Reformed Church, located centrally in a working-class neighborhood at 174 Shenck Street. Partially supported by the Johannesstift in Berlin, and called the Deutsche Vereinigte Evangelische Friedens Gemeinde at its founding in 1889, like many such congregations it was eventually absorbed into the United Church of Christ in the 1950s. Services in this Protestant congregation were conducted in German well into the twentieth century. Haupt had grown up in Halle, the son of the theologian Erich Haupt, a well-known New Testament scholar at the Martin Luther University who became caught up in some of the historicist controversies of the time over the life and teachings of the historical Jesus of Nazareth. After leaving home, Hans Haupt moved away from his pietistic background and into liberal Protestant circles that would have included people Weber knew, such as Friedrich Naumann, Paul Göhre, or Martin Rade, editor of the Christliche Welt—or later on, the American Walter Rauschenbusch, whom Haupt met during a trip to Germany. Haupt wrote for Rade’s journal, and he was primarily interested in practical ethics and the human meaning of the scriptures rather that their dogmatic or literal content. His writings on religion in America, published in German, are concerned with the relation between church and state and the nature of preaching. They reveal above all an intellect attuned to the political and social context of religious life in the United States. The practice of using Bible study to promote “character building” was one among many examples he explored.

Figure 2. The German Reform “Friedens Gemeinde” Church in North Tonawanda, New York, as seen today, a site in 1904 for considering the importance of the Protestant sects in North America. Author’s photograph.

Weber’s central interest in North Tonawanda had to do with the general relationships across the religious community, an individual’s religious or spiritual beliefs, and economic activity. This interest was expressed in a number of comments that served as the starting point for two sets of ideas: first, the formulation of an essential distinction between the religious community as either an institutionalized “church” or a voluntary “sect”; and second, a similarly crucial distinction between considerations of social “status” or socioeconomic “class” and their interplay in nascent immigrant communities that found themselves embedded within a preexisting “democratic” social order.

His informal commentary documented the political and domestic economy of North Tonawanda, starting with the made-to-order wood-frame houses, priced from $1000 to $3000, one of which was the Haupts’ parsonage that the travelers visited next to the Friedens Church. Weber’s comments also included a brief sketch of the Church’s economic and moral foundations:

The congregation consists of 125 families, and church attendance appears excellent, especially with the men. Of course the congregation itself—almost all unskilled workers in the lumber mills and on the docks—supports the church and the minister. The individual worker’s share costs him about $20–30 (80–120 Marks) annually, along with the offerings. The ministerial teaching is a quite undogmatic Christian message, freely interpreted. The congregation pays attention to the minister’s personality and talent as a preacher, and according to Haupt, if the general synod caused problems, the congregation would simply leave. The minister can be terminated with 3 months’ notice (like nearly everyone), though apparently this happens rarely. When he was on the prairie [earlier in his career in Iowa], for a salary Haupt, who reminds one of [Martin] Rade in appearance and speech, received $250 (1050 Marks) a year. The farmers would invite him for dinner on Sunday and would send him ham, etc., while the women donated rabbit pelts. According to Haupt, in [North] Tonawanda his income now is about $1000 (4200 Marks). A mason in New York earns 1½–2 times as much, and a worker in Tonawanda just as much. The 15-year-old maid (a girl from the congregation) earns $104 (422 Marks) a year.… a minister’s salary appears often to vary between $600 and $1000, except for the “stars” in the metropolis. What a contrast with the income of the president of the steel trust [a reference to J. P. Morgan] of $1 million or 4.2 million Marks! (September 8; MWP)

The Haupts’ domestic economy, supporting four children, was similarly constrained and labor intensive, resting on a kind of division of labor reminiscent of the autarkeia (self-sufficiency) of the ancient oikos, or household. Weber had difficulty understanding how they could make ends meet.

According to Rollmann and to Wilhelm Pauck, who asked Haupt about the scholars’ visit many years later, Weber and Troeltsch had requested beforehand that he gather as much information as possible on the moral teachings of the Protestant denominations, particularly as they bore on economic activity. Haupt reported being unimpressed by their scientific curiosity, perceiving Weber and Troeltsch to be suffering from a professorial conviction that they already had all the answers they needed. Nevertheless, in 1906 when Weber came to write his sequel to The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, the essay on the Protestant sects and the spirit of capitalism, first for the Frankfurter Zeitung under the title “Churches and Sects,” then revised for Rade’s Christliche Welt, he alluded in the introductory paragraphs to Haupt’s figures, though without identifying their source. It was the combination of voluntary support for a largely independent and self-governing congregation, substantial tithing of family income, and high rates of Church attendance that attracted Weber’s attention. The comparison with Europe became explicit in his last 1920 revision of these reflections: “Everyone knows that even a small fraction of this financial burden in Germany would lead to a mass exodus from the church. But quite apart from that, nobody who visited the United States fifteen or twenty years ago, that is, before the recent Europeanization of the country began, could overlook the very intense church-mindedness which then prevailed in all regions not yet flooded by European immigrants. Every old travel book reveals that, formerly, church-mindedness in America went unquestioned, as compared with recent decades, and was even far stronger.”

Weber may have overestimated the long-term trend toward secularization, depending on what one means by the term, and his claim about “Europeanization” raises interesting questions about “American exceptionalism” that need to be explored. But at the time his question was, How can the difference between America and Europe be explained?

The answer for Weber, supported by the conversations with Haupt and observations of his congregation, could be found in the form and quality of the personal legitimation offered by membership in the religious community. Such legitimation depended on a certain kind of social and moral dynamic made possible only in the voluntary community of believers, the “sect” form of organization, typical of reform Protestantism. The “personal” character of the attachment was evident not only in the “testing” of individual members but also, as Weber emphasized, in the attention given to the minister’s personal qualities. The ministerial position was not an “office” backed by ecclesiastical structures of authority but an appointment or “election” subject to the popular will of the membership. Thus, in Weber’s classic and widely cited formulation, so essential to the sociological understanding of religious life, the church was “a compulsory association for the administration of grace,” whereas the sect was “a voluntary association of religiously qualified persons.” In Protestantism, as Weber noted, the conflict between these two opposed organizational forms played itself out again and again over the centuries. Nowhere was this truer than in America, which for Weber was the preeminent land of sects and sectlike associations, whose strength was reinforced politically by the formal constitutional separation of the church from the state, and culturally by egalitarian or antiauthoritarian norms.

A source of continual puzzlement and misunderstanding, the generalized religiosity or “church-mindedness” found in the United States was grounded in the voluntaristic quality of the sect form of association and its social functions. In new immigrant communities, however, the exclusive nature of the religious sect could have paradoxical consequences, as Weber noted in his comments about the Haupt family:

They are limited in their efforts to get ahead by their German “accent,” which almost eliminates any opportunity for advancement by a minister. Haupt is thus already anglicized in appearance and intonation. He still preaches most of the time in German, but now and then in English. The high schools (advanced public schools or roughly the third through sixth year of a Gymnasium) are, of course, entirely in English. He must urge his children and his congregation to learn English if they don’t want to remain second rate forever. Enjoying “good company” is rendered difficult by the distances, but also by the residential situation. It is customary for people living on the same street to socialize together, but Haupt lives amid his workers. The doctor and the pharmacist two streets over don’t visit him, nor do the “first rate” families from other parts of town. For having a home in a street regarded as belonging to the “first set” is an indication of being a “gentleman” and leads to acceptance in “society,” even for the most well-to-do. This is a remarkable result of the purely mechanical characteristics according to which democratic society is ordered here. We have great respect for the Haupts (and their children), as they are faced with such conditions, and for the fact that they have stayed and become what they are. (September 8; MWP; emphasis added.)

Though he was writing in German, as if to illustrate the point about the significance of language, in this commentary Weber even used the English terms I have italicized.

Spoken native language as a badge of cultural identity is an issue familiar to immigrant communities, sometimes dividing the generations. In North Tonawanda, public opinion generally supported having German used in the schools, according to Haupt, but a New York State law required that English be used for at least half the instruction. The larger issue was not simply language, however, but the nature of the criteria according to which social status, social distinctions, exclusivity, and inequalities would be practiced in an allegedly “democratic” social and political order—and how and by whom those criteria would be recognized. Class position determined economically or by “wealth” was one obvious answer, a way of defining the structure of opportunity and privilege—that is, “life chances” in Weber’s vocabulary. But in the absence of wealth or inherited status, what else could be used to express the “passion for distinction,” as our second president, John Adams, called this human propensity? The answer implicit in Weber’s commentary is “education.”

Education and the problems of the modern university formed one of the great themes of Weber’s lifework, culminating in the well-known lecture in the last years of his life on the pursuit of science as a vocation or calling. In the figure of Edmund James he encountered a model educator enthusiastic about German scholarship and self-consciously committed to adapting German practices to American requirements. James’s Midwestern Methodist and Huguenot origins may help account for his passionate interest in educational improvements at all levels for men and women, including advocacy for the kindergarten, for coeducation, and for the free public high school, all post–Civil War innovations in American life. Weber was clearly impressed with James and the grandezza of his presence, noting that his position as an American university president represented a synthesis of the political skills of a German minister of culture, the financial acumen of a corporate trustee, and the administrative and ceremonial presence of a German university rector—an astute sizing up of this unique institution.

As an educator, James’s views were an instructive combination of what Weber later referred to as the “dual tendency” in American higher education: encouraging specialized professional training for teachers and businessmen, successfully implemented by James at the Wharton School as a case in point, while also advocating broad preparation for undergraduates across a variety of scientific and humanistic subjects. Weber surely would have had James in mind when he reflected on these issues. Writing for the Berlin press in 1911, for example, he noted that in contrast to the tendency toward specialization, which seemed “European,”

There is another quite opposite tendency found in American business circles—so I was repeatedly told, to my surprise—although I could not assess how widespread this tendency is or how enduring it will be. According to this view, the college, with its particular impact on the character—in the sense of the Anglo-Saxon ideal of the “gentleman”—and the particular type of general education which it offers, seems, according to the experience in these circles, a setting especially adapted for education towards independence—and, it should be added, for the healthy civil self-respect of the embryonic businessman, both as a human being and in his job; as such it is better than a specialized course of study.

It hardly needs to be said that the discussion of “general education,” a subject of intense scrutiny at the time by James and other educators, such as presidents Charles Eliot of Harvard University and Martha Carey Thomas of Bryn Mawr College, and typical still today of American but not European universities, has indeed endured and never abated; it has only waxed and waned in the face of competing claims on the curriculum, conflicting ideals for the educated man and woman, and uncertainties about the requirements for informed citizenship.

What about the object of these discussions, the university students themselves? Weber met many of them, starting at Niagara Falls and North Tonawanda with Anthony and Hermann, the two sons of Edmund and Anna James who were graduates of Chicago’s South Side Academy. Anthony, the older of the two, was a cadet at the Annapolis Naval Academy. The episode returned to Weber’s thoughts during World War I, in the context of a series of speculative comments about the fate of democracy in America in an age when, as he put it, “everywhere in the large states modern democracy is becoming bureaucratized democracy.” The hypothesis, in brief, was that in the large modern democratic polity, educationally certified expertise and organized bureaucracy would challenge the egalitarian status conventions embedded in the self-governing sects:

As a consequence of this war America will emerge as a state with a large army, an officer corps, and a bureaucracy. When I was there previously, I spoke with American officers who were not entirely sympathetic with the demands placed on them by the American democracy. For example, once I was with the family of the daughter of a colleague [Margarethe Conrad Haupt], and the maid was off work. (House maids could take a two-hour break.) The two sons arrived, both navy cadets, and their mother said: “You must go out and shovel the snow, otherwise I’ll be fined 100 dollars.” The sons, who had just been visiting with German navy officers, replied that wasn’t appropriate for them, provoking the mother’s response: “If you don’t do it, then I’ll have to myself.”

This story drawn from everyday life in the James family is an apocryphal but harmless falsification of the actual circumstances described in the Webers’ correspondence. But it served its purpose, not simply as a comment about the status conventions promoted by specialized training or service in the officer corps but also about the role of women in a culture promoting “democratic” norms.

Appearing early in Weber’s 1918 speech in Vienna to Austrian officers, the comment is set up provocatively by a reference to Thorstein Veblen’s sardonic critique of “predatory national policy” as a “sound business proposition” in the last pages of The Theory of Business Enterprise, a text Weber knew well. It would go too far to suggest that Weber shared all of Veblen’s iconoclastic views. But on these matters they did agree on the sources of unresolved conflict in American public life: the radical self-sufficiency and independent spirit promoted “from below” by the self-governing sects, and the status conventions and dependencies promoted “from above” by the administrative state and its orders and agencies. The modern university is caught in this vice, acknowledging the demands of collegiality on the one hand, but bound to the standards of administrative rule on the other. The microcosm of North Tonawanda provided a beginning hint of these competing possibilities.

The dual challenge of the “social question” and the “woman question,” posed often in stark ways by immigration and the conditions of working-class families, elicited other responses in North America and Europe, many of which the Webers were to observe. Marianne had a particularly strong interest in the settlement movement that had sprung up in the late nineteenth century, following the lead of Toynbee Hall in London. On her last full day with the Haupts she chose to explore the situation in Buffalo, leaving Max writing letters, and Troeltsch exploring Goat’s Island with Hensel.

With a population of nearly 400,000 in 1904, Buffalo ranked eighth among American cities, and as a major urban center it had a sizable immigrant population. A large majority of the foreign-born were German. It was the site of the Pan-American Exposition in 1901, the national sequel to the Chicago’s World’s Fair, and memories at the time linked the exposition with President William McKinley’s assassination on its grounds three years previously. The Haupts had actually been present at the fair the day the shooting occurred.

Marianne was accompanied by Grete Haupt and her father, Johannes Conrad. Of the six settlements serving Buffalo’s immigrant communities, they toured only two, probably the Neighborhood House and the Westminster House, the latter close to the German Lutheran Seminary that was surrounded by homes built by German carpenters for their own families. Both of these settlements served ethnic German neighborhoods, and she found them similar to the practice in Germany of establishing “homes” for employees, offering a full range of manual training, especially for young women and men, along with entertainment, theater, and sports. Marianne’s brief observations marked the beginning of her effort to make sense of American social policy and the circumstances of women, an interest that extended well beyond the trip itself. They were supplemented by her extensive conversations with Grete Haupt, a rich source of insight into the position of women in American life that informed her feminist views and the sympathetic perspective on American women that she would articulate upon her return to Germany.

As for the city itself, Marianne was especially taken with the contrast between the downtown streetscapes, the ethnic neighborhoods, and the system of parkways and residential streets designed more than two decades earlier by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, in 1904 at the height of their magnificence:

My trip to Buffalo yesterday was very pleasant, even though all the walking around along lengthy streets was fairly strenuous. Despite the magnificent buildings, the shopping streets as a whole look no more inviting than those in New York: Everything is obscured with a black sooty haze, windows are sometimes dirty—in short, new and yet already falling into disrepair, somewhat like our own suburbs. By contrast, the residential district in the world of elegance is attractive, nothing but tree-lined green streets with charming wood-frame houses that look as if someone had just taken them out of the toy box and placed them on the velvety green lawn. They are the only completely new and original architecture that I’ve seen here so far, and aesthetically far more satisfying than the imposing stone palaces in New York. (September 9; MWP)

The reference was to two contributions from Chicago’s architectural innovators: the Prudential (Guaranty) Building designed by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan, and the Ellicott Square Building of D. H. Burnham, a fitting prelude to the modern cityscape of Chicago that the Webers were about to experience.

In later decades “progress” had its costs. Unfortunately for the city that Olmsted called America’s best planned urban space, in the 1960s his system of connected parkways and residential streets was decimated by the construction of expressways from the suburbs bulldozed through established urban parks and neighborhoods. Only recently have efforts to restore at least some parts of the original design achieved limited success.

Hans Haupt took up pastoral duties in a different German Reform church in Cincinnati in 1910, thriving in an environment with an educated congregation more congenial to him, Grete, and their children. The couple remained there the rest of their lives. When in old age Grete lay dying from cancer, Hans read to her between three and five in the afternoon from Marianne Weber’s recently released biography of her husband, “a few pages to her every day.” What would they have thought had they been able to savor all the comments from a few days in 1904 about their lives of service to the immigrant community? The community they left behind succumbed slowly to the blight left by deindustrialization and globalization. At the beginning of the twenty-first century the once-vibrant Friedens-Gemeinde Church has been converted to the Ghostlight Theater, an irony that should not be lost on those who now attend its shows and perform on its stage.