The journey from Boston to New York City by train followed the route through Providence, Rhode Island and New Haven, Connecticut. Writing to Hugo Münsterberg from Philadelphia, Max Weber had expressed the intention of stopping at both Brown University and Yale University, still in search of library holdings related to Puritanism and the Protestant sects. Armed with a recommendation from Münsterberg, he managed only the brief excursion to Brown, with amusing and revealing results. Weber made a point of noting that he was in “the oldest homeland on earth of freedom of conscience (Roger Williams) and the separation of state and church” (November 6; MWP). In search of documentation on this topic, he located the campus librarian who informed him that the university, though founded by Baptists and a few Congregationalists, had decided to erase any connections to its religious and “sectarian” heritage. It had retained no holdings on the history of the Baptists and avoided collecting even modern literature on the founding denominations. This exercise in forgetting the past and becoming nonsectarian and “modern” impressed Weber sufficiently to footnote it in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, mentioning that if one wanted to know about the American Baptists, then the best library was not at Brown, but at Colgate University, an institution also founded by Baptists.

While in New England the Webers had taken two days to visit another member of their Fallenstein relatives, Max’s half cousin Laura, her German immigrant husband Otto von Klock, and their eight children, residing in Wyoming, a community near suburban Medford, north of Boston. It was part of the effort to keep up with the fate of the family’s colonial children, as Guenther Roth has shown. Klock had set up a successful typewriter and translation business under Laura’s name (L. Fallenstein and Company), and had received commissions from the Astors and other established and wealthy families to conduct genealogical research. For the status conscious, recovering a personal past could sanction pedigree and anchor social prestige, a sign of “Europeanization,” Weber maintained. The brief stay turned out to be enjoyable and instructive. Max thought the native-born Klock children had become fully assimilated to American life, despite their father’s scorn for “Yankees” and his romanticized longing for a Germany that had disappeared. Secularization had set in, too, as the second generation drifted away from Protestantism, a trend Weber thought was typical in immigrant families.

Arriving for their second stay in New York City a few days before the presidential election, the Webers this time located farther uptown, past Theodore Roosevelt’s birthplace to the Holland House at Fifth Avenue and Thirtieth Street. The hotel was four blocks north of D. H. Burnham’s recently completed Flatiron Building. The next week in a cost-saving move they relocated to a boarding house at 167 Madison Avenue, closer to the Thirty-third Street Station on the subway that had opened just two weeks earlier. Operated by a Frau von Hilsen, the Madison Avenue residence housed two American couples and several young German businessmen employed in the city. The German immigrants’ accounts of life in New York gave Weber another lesson in the attractions of American clubs that found its way into his revised “Protestant Sects” essay and the seminal essay on class and status: outside the work setting, the absolute equality among “gentlemen,” regardless of differences in economic class or social status. Alexis de Tocqueville had been impressed by the same phenomenon, though he had not generalized the observation into an analysis of the essential difference between “class” defined economically and “status” defined in terms of social prestige and honor.

Among the American cities, Boston had seemed to the travelers “older, more refined, and more harmonious” than others. The Webers had been especially impressed by Copley Square, bounded by Henry Richardson’s Trinity Church on the east side and Charles McKim’s Boston Public Library to the west. The church’s bold Romanesque adaptation juxtaposed to the library’s Italian Renaissance classicism and warm interior seemed especially ingenious and aesthetically pleasing. Marianne wondered what her brother-in-law, the architect Karl Weber, would have thought about it. Now in Manhattan they returned to the sights, sounds, and rhythms of the metropolis that at first had seemed so startling, new and alien. But Marianne’s responses had caught up with Max’s initial enthusiasms, and she reported feeling “completely at home” amid the strikingly diverse human populations and the architectural variety. Her observations, like her husband’s, sometimes turned rhapsodic:

The view from the Brooklyn Bridge is marvelously fantastic with the evening glow on the illuminated skyscrapers! The mass of enormous structures at the tip of Manhattan, aglow with a million lights, rise up into the glimmering dark red and lilac sky like a strangely shaped mountain. It is as if the spirit that lives in these buildings, striving for financial gains, has embodied itself in glowing streams of gold penetrating the walls like X-rays. A vision like a fairy tale! One could believe that one is looking at the castle of the Holy Grail or some kind of magic palace (November 19; MWP).

Fantastic, magical, strange, mythic, unreal: whether as fairy tale, legend, or science fiction, the language was Marianne’s effort to capture the poetry of the modern.

The spirit of the new century had been in evidence during the fall presidential campaign, personified by Theodore Roosevelt. The election fell on November 8, 1904, offering Weber a welcome opportunity for observation. Coincidentally, James Bryce was also in the city as an observer, having just completed his Godkin lectures at Harvard University, “The Study of Popular Government.” In Manhattan Judge Alton B. Parker won easily, improving on William Jennings Bryan’s margin of victory in 1900. But Theodore Roosevelt captured Brooklyn and carried his and Parker’s home state by about 175,000 votes, and the nation with thirty-two states and more than 56 percent of the vote, leading to a comfortable electoral college margin of 336 to 140. Voter turnout in the five boroughs was astounding by today’s standards, at 93.7 percent. There was one local surprise: running for another term as a Democrat in the state senate, George Washington Plunkitt of the Tammany Hall machine, famous for his view that “honest graft” is a democratic birthright, was defeated by 344 votes, his first loss in a career spanning more that four decades. Roosevelt’s electoral “coattails” may have made the difference. Surveying the presidential results, the New York Evening Post editorialized that Roosevelt’s commanding victory was a “personal triumph,” a tribute to his “personality” that had “captivated the imagination of the American people. His immense instinct for publicity, and his perfect command of the ‘grand high pressure of bustle and excitement’ which is so powerful a political instrument in a democracy like ours, with his outstanding and taking qualities, have won the general heart and made him the victorious leader he is.” In a few lines the Post managed to announce the arrival in America of the leader with “charisma,” Max Weber’s contribution to our political discourse, whose personal qualities overshadow everything else. It is no wonder that when Weber searched for instances of charismatic politicians combating bureaucratized party machines he chose Roosevelt as one of his examples.

During the two weeks in the city the Webers had not only opportunities for observing politics but for taking in cultural and social life. They had the opportunity to feast on a rich cultural fare, starting with the American premier of Gustav Mahler’s Fourth Symphony, conducted by Walter Damrosch (negatively reviewed, as in Europe); Richard Wagner’s Parsifal; a musical version of The Wizard of Oz; the play Alt Heidelberg, transformed later by Sigmund Romberg into his musical hit The Student Prince; Henrik Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler; the melodrama Sunday featuring Ethel Barrymore, who was described in the press as the personification of “ultra-modern refinement”; classics like William Shakespeare’s Hamlet or Much Ado about Nothing; and on and on. The Webers followed the musical and theatrical scene closely, having attended performances of Ibsen in Berlin and Wagner in Paris, for example. But from this menu of choices they selected only the local Yiddish theater. In New York they had other far more important matters on their minds: the settlement houses; the immigrants on the Lower East Side; the social work of Florence Kelley, Lillian Wald, and David Blaustein; Columbia University colleagues, lectures, and the library; the churches and sects; labor relations and the trade unions; and former acquaintances and family contacts. It was dizzying itinerary. Taken in tow by Edwin and Caroline Seligman, and by the brothers Paul and Alfred Lichtenstein and their wives Clara and Hannah, the daughters of Friedrich Kapp, the result was an event-packed schedule and encounters with “as many people as during a year in Heidelberg.”

The second day in the city was a Sunday, providing an opportunity to continue the practice of observing religious services. New York offered fertile ground, so the couple divided forces: Marianne selected a Presbyterian service at the old Marble Collegiate Church next to their hotel, while Max traveled uptown to the new First Church of Christ Scientist on Central Park West at Ninety-sixth Street. With a sanctuary dating from 1854, Marble Collegiate had been chartered in 1628 as a Dutch Reformed church and could thus proclaim itself “America’s oldest Protestant Church with a continuous ministry.” It became famous later in the century through the five decades of preaching and leadership by Norman Vincent Peale, and among its best known parishioners was then lawyer Richard Nixon. The “power of positive thinking” promoted by Peale was a perfect expression of the “mind cure” at its optimistic best as analyzed by William James—a much later chapter in the adventures of worldly asceticism. The service presented Marianne with a contrast to the Haverford Friends Meeting; it was a model of a refined and distinguished denomination, offering parishioners “soft cushions and fans in the pews,” in Weber’s phrasing.

The leading turn of the century example of “mind cure” for James and Weber was, of course, Christian Science. The Upper West Side church that Max attended, completed in 1903 at a cost of over a million dollars, was designed by John M. Carrère and Thomas Hastings with the aim of capturing the spirit of the new outlook on life, emergent from a sacred past. Trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the architects modified the beaux arts style to create a monumental synthesis of the Roman basilica and the New England meeting hall. The massive, unadorned exterior of primary forms seemed modernist, possessing “a degree of force and power that is astonishing” in the words of the Architectural Record. For Hastings, the architectural theorist, the modern idiom required finding a compelling language of expression for the uniqueness of the present age while showing sympathy for historical styles of building. “In solving the problems of modern life,” he wrote, “the essential is not so much to be national, or American, as to be modern and of our own period.” The new requirements for the built environment were supposed to match the new universal message for the inner life.

During his travels Weber had puzzled over the evidence of a trend toward secularization in American society. On the one hand, there were signs of movement away from church life and religiosity among the youth, second- and third-generation immigrants, and—in the East—the older generation as well. But on the other hand, summing up impressions at the end of his stay, he found American life “full of secularized offspring of the old Puritan religiosity.” Distinguishing the “secular” from the “sacred” could be elusive. In making social contacts and forming friendships, for example, the Lichtensteins reported that the first question often was, “Which church do you belong to?”—at least in “more devout” Brooklyn where they lived, as distinct from a more secular New York City. Religious affiliation still carried weight in social relationships, as the strength of the sects even in the remote Indian Territory had demonstrated. And in contrast to Europe, there were the phenomena of religious revivals and the new religious movements, such as Mormonism and Christian Science. The opposing impressions produced “strange contradictions,” Weber concluded, as he described the Sunday event:

Today I attended a “service” of the “Christian Scientists” (faith healers) here. They have two grandiose churches here, outfitted in the finest manner for religious services. For sermons and the services generally the “Christian Science Quarterly” provides programs, texts of the psalms, passages from the Bible and from the symbolic book “Science and Life.” Their “hymnal” is compiled from different national choral works, with melodies from Handel, Haydn, Weber, Mendelssohn, German folk songs and English melodies. The “church” proper, an impressive vaulted space with rostrums and a mighty organ, was stuffed full of people: everyone from “good society” including the middle class. On a raised platform in front of the organ sit 10–12 men and women in tuxedo or white silk, and in front of them two pulpits, from which a man in a tuxedo and a woman in white—about 40, with a garland in her hair and a deep alto voice—conduct the service. First a chorus from the “Messiah” (a wonderful piece), then liturgy: Psalm 38, alternating between the woman preacher and the congregation; then 10 minutes of deep silence for prayer (for the spiritual and physical well-being of one’s neighbors), ending with an audible collective “Amen;” then a congregation hymn sung by everyone, leaving quite an impression; then a “sermon,” that is, the woman and man preacher alternate in readings: he from about 30 places in the Old and New Testament, and she from the book “Science and Life,” drawn apparently from their conception of preaching. Contents: again and again emphasis on “immortality,” metaphysically in Plato’s sense—or even better, Moses Mendelssohn’s “Phaedon”—in short, ceremonial, and slowly spoken maxims; then the sole reality of the “spirit” and the emptiness [Nichtigkeit] and transitoriness of matter; God’s limitless omnipotence over humanity and the depravity of all who seek to resist that omnipotence, thereby proving they are not protected by “spirit” and thus blessed with “immortality;” warning about “false friends” (apparently physicians)—45 minutes long, presented without much pathos until it became boring. Then an organ fugue and offertory (i.e., a collection plate covered with dollar bills passed around by men in dark suits); a soprano solo (sung with a lot of tremolo in the English style, unknown to me, probably a modern composition); a congregational hymn and conclusion; and departure to another room for Sunday school by the attractively dressed children, which is a pièce de resistance here, as it is everywhere. There were certainly 800 and perhaps 1000 people in attendance, and their behavior fell unambiguously under the concept “devoutness.” The movement hasn’t reached its peak yet, and it spreads into all the large cities in the Union (November 6; MWP).

As he had done years earlier in Strasbourg, Weber paid attention not only to the outward forms of devotion but to the selection of appropriate texts and the substance of the spiritual message about the soul’s immortality, noticing its similarity to the philosophical attempt to reconcile reason and faith in the German-Jewish Enlightenment.

In The Varieties of Religious Experience William James had explored the psychological dynamics of Christian Science’s spirituality; he thought the sect represented “the most radical branch of mind-cure in its dealings with evil,” an assessment congenial to Weber’s views about religious responses to the theodicy of suffering. Indeed, knowledge of the church could well have come from James, who was himself in the city during the week to assist in opening a mental health clinic. James also understood perfectly well the practical effects on conduct of the “mind-cure movement” and the reasons for its popular acceptance. As he wrote in Varieties,

The deliberate adoption of a healthy-minded attitude has proved possible to many who never supposed they had it in them; regeneration of character has gone on an extensive scale; and cheerfulness has been restored to countless homes. The indirect influence of this has been great. The mind-cure principles are beginning so to pervade the air that one catches their spirit at second-hand. One hears of the “Gospel of Relaxation,” of the “Don’t Worry Movement,” of people who repeat to themselves, “Youth, health, vigor!” when dressing in the morning as their motto for the day.… The plain fact remains that the spread of the movement has been due to practical fruits, and the extremely practical turn of the American people has never been better shown than by the fact that this, their only decidedly original contribution to the systematic philosophy of life, should be so intimately knit up with concrete therapeutics.

In the last analysis it was not so much refinement of the doctrine of immortality but the therapeutic benefits for life conduct that mattered most to the receptive public. Even in James’s and Weber’s time commercial interests sensed a chance for profit, generating a self-help literature of “insincere stuff, mechanically produced,” as James observed, that might induce in avid readers at least an aura of spiritual authenticity.

The following Sunday the Webers continued this line of investigation by attending a service of the Ethical Culture Society, meeting in Carnegie Hall. The Society’s founder, Felix Adler, then a professor of social and political ethics at Columbia, delivered a lecture titled “Mental Healing as a Religion,” an exercise in coming to terms with Christian Science and similar faith cure and “positive” spiritual tendencies. Marianne found the talk “rather dull,” but the corrected manuscript has survived in Adler’s papers, so we can judge for ourselves. The German-born Adler knew both Edwin R. A. Seligman and William James—Seligman through their upbringing in German-Jewish circles and the Temple Emanu-El, where Adler’s father was rabbi and Seligman’s an important trustee; and James because of their shared philosophical interests. James even sought to recruit Adler at Harvard, though without success. Adler’s life had been and continued to be a heroic, sustained religious and spiritual quest. His views had migrated from orthodox rabbinical training, through Reform Judaism, to a position somewhere within the orbit of Immanuel Kant’s ethical rationalism, and finally to a view of life and world animated by a kind of Emersonian faith and informed by a pragmatic ideal of human perfectibility. Reflecting on Adler’s spiritual migration and core beliefs, one of his assistants called Ethical Culture a “creedless religion” that embraced a spare maxim for human conduct: “So act in all your relationships, in the family, in business, in politics, in the professions, as to elicit the best in others, and in so doing you will enhance your own worth.” Translating this morality into Benjamin Franklin’s idiom, it would have specified a concise code of conduct: helping others is the best policy, because you thereby help not only others but also yourself.

In his Sunday address Adler’s starting point was surprisingly a discussion of Lafcadio Hearn’s new book, Japan: An Interpretation (1904), though with the intention of claiming that Japanese successes in the present age had a “moral” foundation and discipline “furnished principally by their religion.” The example served to state a pragmatic criterion of truth: if a religion “manifests good results in the behavior of its followers,” then there must be, Adler held, “a certain measure of truth in it.” This served as a standard of judgment for mental healing and faith cure, from the old practices at Lourdes, which Weber had beheld with spellbinding fascination, to ancient pilgrimages of the devout, to contemporary attitudes about the treatment of cancer and diphtheria, to the new abstract principles of Christian Science. Of course, Adler objected to Christian Science’s metaphysics and science concerning the nature of matter and evil. But his chief complaint was its quiescence or inwardness: ascetic, to be sure, but too otherworldly, or, in Max Weber’s terms, insufficiently oriented toward employing religious asceticism to master and transform both nature and the world of human affairs. If Adler’s interpretation and critical assessment raised questions, then there was an occasion for follow-up, as the Webers dined with Adler and his wife at the Seligmans’ Upper West Side home the following evening.

Weber had his own views about the social implications of religious faith and organization. In his work he attempted to search beneath sectarian forms, such as those observed at the Christian Science service, not just for their psychological implications but for their social reality—that is, for the rational patterns of sociation and group legitimation of the individual self. The sophisticated liturgical, metaphysical, and musical details of the New York service might seem a world removed from circuit-riding Methodist preaching, the staging of a mountainside Baptist baptism, the expressiveness of an urban African American Baptist church, or the austere silence of a Quaker meeting. In the range of religious experience, no doubt for Weber the contrast between Christian Science extravagance and the spare Haverford Friends Meeting could not have been more starkly drawn. However, these different settings and modes of spirituality were united in the search for “salvation” and the claims upon the self in the sober matter-of-factness of sociation, in the social testing and demonstration of one’s moral qualifications before one’s peers. The voluntary sects—Methodist, Baptist, Quaker, or Christian Scientist—promoted outcomes having implications for the individual’s self-identity and standing in the social order. They also had indirect “political” implications because they were the crucible, Weber thought, in which the idea and practice of democratic associational life took shape.

During these final weeks in New York the Webers moved primarily in German-Jewish and progressive reform circles. Edwin R. A. Seligman, the prominent professor of political economy at Columbia, squired Max around the campus, where he met with colleagues, attended lectures, and used the library. The professional discussions would surely have included John Bates Clark, the economic theorist, who had lectured on the same panel as Jacob Hollander at the Congress of Arts and Science in St. Louis. Caroline Seligman hosted a women’s lunch for Marianne, and on the Webers’ last day in New York a reception in her honor at the University Club, guiding her on a program of site visits, meetings, and lectures. The Seligmans were closely affiliated with the city’s main institutions of social reform and social welfare, from the Ethical Culture Society to the Educational Alliance, and they knew the participants and leadership well. Edwin Seligman’s advocacy of municipal reform obviously placed him in direct opposition to Tammany Hall and New York’s tradition of machine politics. Discussions in these circles, supported by Friedrich Kapp’s and James Bryce’s critical commentaries, would have provided a useful supplement to Weber’s thinking about political parties, corruption, and the urban political machines. Passages like those in Economy and Society about administrative and civil service reform in the municipalities, or public subsidies for parochial schools, a policy promoted by Boss Tweed’s Tammany Hall to ensure loyalty among Catholic voters, should be considered a case in point. Progressive reformers like Seligman advocated administrative reform, and they generally viewed such subsidies as a kind of abridging of the constitutional separation of church and state for electoral gain, thus yet another instance of corruption.

Marianne Weber had an especially strong interest in the settlements and women’s contributions to social welfare, evident already in her Buffalo, New York, excursion with Grete Haupt and Johannes Conrad, and the day with Jane Addams and the Women’s Trade Union League at Hull House in Chicago. In New York she and Max added three new settlements to their itinerary: University Settlement, Henry Street Settlement, and the Educational Alliance. The oldest was the University Settlement, founded in response to the influx of immigrants by Carl Schurz, Stanton Coit of the Ethical Culture Society, and others in 1886, two years after Toynbee Hall in London and three years before Hull House. It was in the settlements that they met Florence Kelley; Lillian Wald, the cofounder of the Henry Street Settlement; and David Blaustein of the Educational Alliance. Their visits and discussions in these institutions were also the vehicle by which their thoughts about sociation and group activity—the social and political functions of the clubs, orders, and sects in American life—came to a conclusion.

In Max Weber: A Biography Marianne made a point of commenting on the self-government of the young boys’ and girls’ clubs in the settlement houses, the relative freedom from authority of the youth, and the use of the clubs as the most essential “means of Americanization.” She also underscored the overriding importance of the model of the voluntaristic sect for civic education and all kinds of citizen-initiated social and political action, quoting one of Max’s most unqualified assertions:

The tremendous increase in the clubs and orders here substitutes for the declining organization of the churches—that is, the sects. Nearly every farmer and a large number of businessmen of medium and lower rank wear their “badge” in the buttonhole, as the French wear little red ribbons, not primarily because of vanity, but because it immediately legitimates the wearer as a gentleman, accepted by ballot by a specific group of people who have investigated his character and circumstances. One automatically thinks of our investigation of reserve officers. This is exactly the same service which was rendered a member of the old sects (Baptists, Quakers, Methodists, etc.) by his “letter of recommendation” that his congregation gave him for his “brothers” elsewhere. (November 19; MWP)

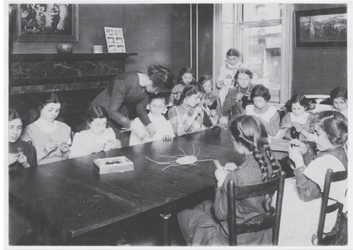

Figure 11. Jewish immigrant girls attending a Henry Street Settlement knitting class, similar to scenes the Webers encountered in the Lower East Side settlements of New York City. Courtesy Library of Congress.

While stating the claim in clear language, Marianne’s selected passages are unfortunately cobbled together and lifted from different letters and contexts, making this passage appear to come from the Webers’ Sunday afternoon in Mt. Airy, North Carolina, earlier in their trip. But it is actually one of Max Weber’s summations about New York—and, in particular, the lessons of the settlements on the Lower East Side and their educational programs for Jewish immigrants—that had for him made “the most powerful impression.”

The general idea about the sources of social engagement and cohesion that today would be called “social capital” is, of course, not Weber’s alone. Tocqueville and Bryce had made similar observations about the penchant for group activity and collective local initiative in American social and political life. Moreover, the settlement movement itself in New York was quite explicit about introducing new arrivals to American life through the self-conscious adaptation of American cultural, social, and political forms: clubs, groups, committees, meetings, voting, majority rule, the right to express one’s own opinion, public debate, representation of interests, a structure of elected offices, procedural fairness, impartial parliamentary rules of the game. To become an American was to adopt such public “values” and modes of public conduct, to learn and to internalize these forms and the norms associated with them. The new citizenship meant a turning away from traditionalism and the older sources of authority and identity, such as those rooted in custom, nationality, ethnicity, religion or language, and becoming “equal” and “modern.”

In Weber’s account the theme of the “cool objectivity of sociation” and social capital is developed in a distinctive way for two reasons: the introduction of the concept of the “sect,” and the treatment of the great triad of modern social theory: class, race, and gender. The latter set of issues reached its apogee with the question of the immigrant and immigration. The journey had in a way started with an awareness of immigration and the exploitation of immigrants aboard the Bremen. In the New World the social horizon had been broadened especially by the days in Chicago; in Muskogee, Indian Territory; at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama; in Knoxville, Tennessee; and in Mt. Airy, North Carolina. New York became the final social laboratory. It completed the circle: the poor Eastern European steerage passengers crossing the Atlantic had now returned in the Lower East Side settlements and tenements. What had become of them?

The most comprehensive summations of the New York settlement experience were actually Marianne’s, only partially cited in the biography, though without admitting her authorship. Max had summed up their impressions and given them “theoretical” grounding, but the details were hers. Such a division of labor was not uncommon for the couple, and it reflected their gendered roles.

As could be expected, Marianne was most impressed by the treatment of youth and young working women. Commenting on the large number of boys’ and girls’ clubs, she noted that they

already encourage children to organize themselves for common purposes. Creating good social relations may well be the main thing, but each of these small clubs also engages in social work—for example, collecting money for a hospital or Christmas gifts for poor children, handing out helpful pamphlet, or something similar. The executive committee of such clubs is always composed of the children. They have a Mr. Chairman, a treasurer and recording secretary, and they regularly vote on acceptance of members. In short, they use parliamentary forms and in this way ensure that the basic principles of self-government and cooperation are, so to speak, imbibed with mother’s milk. I think this side of children’s life here, so completely alien to us, must exert an invaluable influence on their education and upbringing. (November 11; MWP)

The comparisons with Germany were never far from her mind. In Boston, Simmons College had reminded her of the Lette Houses, the project in German cities of Wilhelm Lette to expand vocational opportunities for young women, especially those who were unmarried. The New York settlements offered an even better model of combined vocational and social support networks, as an evening at a young working women’s club illustrated:

The young women from different businesses find social contact, decent entertainment, also continuing education courses and evening discussions. In Germany the branch organization of the different professions would make it impossible. The multiplicity of status differences doesn’t exist here. The stenographer, salesperson, milliner, and factory worker feel themselves after work to be equal in terms of style and dress. During the evening there was a general discussion on a theme chosen by the chairperson (a “lady” and not a worker), very philosophical and seemingly abstract: “On Ability.” But it was quite remarkable how the chair wove the threads together and led the young people into all kinds of questions that would concern them inwardly, from religion to morality. It was even more remarkable that she knew how to get the girls to speak and to engage in a lively exchange of opinions. This woman belongs to those wealthy individuals who with genuine democratic and socially responsible feelings devote all their time and energy to the working class. (November 19; MWP)

The event seemed to Marianne not only a lesson in the leveling of class and status differences through social interaction, group affiliation and educational opportunities but also a lesson in adroitly connecting private concerns with the public persona and the public realm.

Gender differences obviously continued to play a role in the settlements, not only through the organizational structure but in terms of the content bearing on the social construction of the self. Having observed a working girls’ club in action, she sat in on a boys’ club, too. “That was a remarkable event,” she wrote,

absolutely absent from our life [in Germany] and probably quite impossible in view of our basic principles of education. The small 12-year-old boys conducted themselves entirely using parliamentary forms: there was a vote on a new member following the report of a “commission” about his character, then a literary part. One boy read a poem he had apparently written himself, and then the most priceless event: a discussion on the political question of whether it would be better to have senators elected by the “people” or, as it is now, by representatives. Two boys each had to argue the case pro and contra, and one of them spoke with gestures and every other skill, “criticizing” the weaknesses of the present system like an experienced adult. The young politicians (entirely Jewish working-class children) showed no signs of being shy around us adults. (November 19; MWP)

The boys’ club was a microcosm of the “objective” forms of sociation: the test of personal legitimation, an inquiry into character, disclosure of the self before one’s peers, public debate of a contested constitutional issue (the Seventeenth Amendment was ratified nine years later), the confident tone and gestures of modern self-reliance. In these matters class, nationality, religion, and ethnicity—and in this case, age—made no difference. Could there be any more definitive example of schooling for democracy and the institutionalization of political education? Max Weber considered it an instance of absolute self-government because all other external authorities were excluded from the group’s internal deliberations.

The only element missing, an important one encountered in the girls’ and working women’s clubs, was the connection that might have been established between the private world of inwardness, the spirit or the “inner life,” and the external world of social relations and public affairs. That connection, sometimes carefully forged and other times ignored or absent, has always haunted the American liberal constitutional project with its overlay of Enlightenment rationality.

The conversations with Florence Kelley and Lillian Wald reinforced the visitors’ views about the social and political significance of the settlements while reminding them of critical areas in need of social reform, as encountered previously in Chicago. Serving at the time as secretary of the National Consumers League, Kelley impressed them with her engaging presence, “passionate socialism,” and sharp social criticism. Attending her speech at the School of Philanthropy, recently opened with a full year program in social work—the nation’s first—the Webers heard her critique of the lack of federal labor legislation protecting men, women, and especially children from exploitation. Deploring the consequences of “state particularism” and the confusing and discriminatory patchwork of state labor laws, she also relied on her prior experience at Hull House and her work as the chief inspector of factories in Illinois to excoriate the corrupt practices and collusion of some of the unions, big business, and the state legislatures. Of course, Marianne would have identified, too, with her feminist views about the importance of extending rights to the disadvantaged and about the prospects for lasting social reform. “An ethical gain has been made,” Kelley wrote about public policy, “whenever the new intelligence of women has become available to the body politic.” Supporting evidence came from the settlement movement itself.

After moving to New York, Kelley had become a member of Lillian Wald’s inner circle at the Henry Street Settlement. Wald had established public health nursing as her special mission after graduating from the New York Hospital Training School and studying at the Women’s Medical College of New York Infirmary for Women and Children. Funded privately by people like Betty Loeb and her son-in-law Jacob Schiff, Wald’s nonsectarian efforts were remarkably successful, both for training nurses and in providing health care to the local population, especially the indigent poor and the working class residents of the tenements. By 1903, after ten years in operation, her Nursing Service boasted eighteen district centers, serving about 4,500 patients per year, to which were added more than 35,000 home visits. The service eventually was extended to cover the entire urban area. The arrangements reminded Marianne, who dined with the women one evening, of a “Diakonisse” like those in Europe managed by the Protestant religious orders, although with profound differences: following Wald’s prescriptions, the medical vocation became more attractive to educated women, for it allowed room for individual initiative and personal development and freedom. The Henry Street locations also turned into centers for the wide array of social activities, club meetings, and educational projects characteristic of the settlement movement as a whole. They were a center of community life, a site for sociability, a counterweight to the historical condition Max Weber called “the most fateful force in our modern life: capitalism.”

Capitalism and its beguiling spirit were never far from Weber’s consciousness. He had just written about the topic, transported to the scene of its highest development by Benjamin’s Franklin’s words. In New York there were more than enough daily visual and aural reminders. But Max and Marianne Weber wanted to know about the social and cultural responses, the contours and substance of the life world of the metropolis. The churches and settlement houses told only part of the story. In a city of millions there would always be more byways and niches to explore.

Aside from the Seligmans’ invitations and guidance, some of the Webers’ afternoons and evenings were taken up with family-related friendships. Helene Weber had suggested they look up Friedrich Kapp’s daughters Clara and Hannah, and so they did: Clara was married to Paul Lichtenstein, and Hannah to his younger brother Alfred. The Lichtensteins were successful bankers in Manhattan, residing just across the Brooklyn Bridge in Brooklyn Heights. Max seems to have enjoyed their entertaining company over two dinners, discussing religious attitudes and business affairs, while Marianne chaffed to return to her place among the women social activists. The couple also sought out Otto Weber Jr. and his bride Mabel James, and their family friend, Hermann Rösing. Another one of the cousins, Otto worked in the Wall Street financial firm of G. Amsinck and Company. Of all these connections, however, the most striking was perhaps the afternoon with the Villards—Helen Frances Garrison Villard, the activist liberal reformer and daughter of William Lloyd Garrison, and her daughter-in-law Julia Sandford, recently married to the outspoken son, Oswald Garrison Villard, editor of the New York Evening Post and its weekly supplement, The Nation. Max had known the Villards in Berlin, where Henry Villard (then Heinrich Hilgard), who had died in 1900, had moved in circles around Weber’s father and Friedrich Kapp, and the young Oswald had attended the same Charlottenburg Gymnasium as Max and his brother Alfred. The family’s unquenchable zeal and life of determined political engagement was captured best by Oswald’s later homage to his mother, writing, “Certain of the triumph of every cause to which she gave her devotion, she was incapable of compromise, without being either a bigot or narrowly puritanical.… To modify any position she took for reasons of expediency—that was unthinkable; to shift her ground in order to gain a personal advantage, or to avoid unpleasantness, was as impossible for her as for her father, the strongest lines of whose countenance reappeared, with the years, in hers.” Like father, like daughter, and like the daughter, so also the son: the rendezvous was surely a reminder of political struggles in the past, in America and in Germany, some successful and some a failure, and the fading light of the nineteenth century reformers. Helen Villard mentioned that she would still put in an appearance that week at the fashionable fall horse show in Madison Square Garden, a “high society” encomium for the Gilded Age. Max could only imagine with bemused intuition the Vanderbilts and other celebrities on display in their boxes, while the plebian interlopers ogled them and the show.

Among the forays into the city’s varied cultural life three more investigations of an entirely different order were particularly instructive. One was a lecture at the League for Political Education by Dr. Yamei Kin, the well-known physician and public speaker, addressing the timely topic, “A Chinese Woman’s View of the War in the East.” Raised by Protestant missionaries after her parents died in an epidemic, Kin had come to the United States and earned an MD from the Women’s Medical College of New York, the first Chinese woman to do so. She knew Lillian Wald and the Henry Street Settlement, sharing Wald’s concern for public health, and used the settlement as a model for her hospital work and nurses’ training in Tianjin, China. Though there was a war in Asia, “The time is coming,” she predicted in her talk, “when there will be different struggles, mind against mind, commerce against commerce, not physical force against physical force.” Marianne was charmed by her example and her frankness:

Remarkably, her sympathies were on the side of the Russians, who would pose no danger for oriental culture, as they can be fully assimilated to it, thus in time would simply become Chinese. What she said was interesting enough, but the attraction was also the charming manner in which she spoke and her petite and graceful appearance in her colorful Chinese costume, which we could use quite nicely as the basis for our reform dresses. I had to agree with her as she scolded the Western European peoples for presuming to force everyone in the world into their capitalist-industrial culture, “so that every nation becomes exactly alike the other,” just as one commodity is identical to another. This petite, smart person was at the very least a welcome example. One would not want to see her forced into our forms. (November 15; MWP)

The New York Times confirmed Kin’s message: “Would you have us all alike?” was her question; “you have done many things,” she continued, “made many machines that turn out many things—all just alike. Would you do the same with us? So far you have given us only your vices. But we would like your virtues.”

At the top of the list of “virtues” were the basic political goods—the rights of citizenship, the rule of law, equal access to a public realm of communication and action—precisely the values and aims of the settlement movement in creating a new civic life for immigrants. The difficulty, however, was that such a regimen might sit uncomfortably alongside inherited cultural forms and identities, challenging or negating them. Kin was interesting because she recognized the problem, bridging the divide in her own person and anticipating an issue for the twenty-first century.

The Webers spent a quite different evening with a secretary of the local typographical union and his wife, a dinner followed by a tour of a newspaper printing plant. Though neither Max nor Marianne mentioned their host’s name, it was probably Jerome F. Healy and his wife, Margaret Ufer Healy. At the time Healy was secretary-treasurer of the New York City Typographical Union No. 6, a biennial elected position in which he had served for eight years. The meeting could have been arranged by Seligman or by Hollander, or especially by labor economics scholar George E. Barnett, who was studying the printing industry and had become an expert on the Typographical Union, the oldest national trade union in the country. The conversation and on-site inspection would have satisfied Weber’s curiosity about the modern press and newspapers, expressed a few years later in his Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie proposal for a comparative study of newspapers, news reporting, and journalism. Marianne marveled once again at the relative absence of status distinctions, the working-class typesetter having become a “complete gentleman” and his wife a “well-read lady” of the middle class, the couple owning their own self-built home and traveling every few years to Europe. The style of life upended her notions of hardscrabble working-class existence.

For Max Weber the results came later as he reflected on the topic of political governance, administrative expertise, the progressives’ demand for civil service reform, and the problem of corruption in modern democracies. When in a wartime speech on socialism he alluded to having spoken to American workers about the topic, it is surely Healy whom he had in mind. His observations were at least colorful, if somewhat dated, noting, “The genuine American Yankee worker enjoys a high level of wages and education. The pay of an American worker is higher than that of many an untenured professor at American universities. These workers have all the forms of bourgeois society, appearing in their top hats with their wives, who have perhaps somewhat less polish and elegance but otherwise behave just like any other ladies, while the immigrants from Europe flood into the lower strata.” Weber’s firsthand statistical survey supported the conclusion about status and class differences and the embourgeoisement of the working class: unionized, skilled blue-collar workers did command higher wages than academics, notwithstanding the latter’s perceived higher status, and of course they occupied a place in society far removed from the new immigrants. “Whenever I sat in company with such workers,” Weber reflected,

and said to them: “How can you let yourselves be governed by these people who are put in office without your consent and who naturally make as much money out of their office as possible … how can you let yourselves be governed by this corrupt association that is notorious for robbing you of hundreds of millions?”, I would occasionally receive the characteristic reply which I hope I may repeat, word for word and without adornment: “That doesn’t matter, there’s enough money there to be stolen and still enough left over for others to earn something—for us too. We spit on these “professionals,” these officials. We despise them. But if the offices are filled by a trained, qualified class, such as you have in your country, it will be the officials who spit on us.” That was the decisive point for these people. They feared the emergence of the type of officialdom which already actually exists in Europe, an exclusive status group of university-educated officials with professional training.

Plunkitt’s recent defeat would have added the reminder that even the best-oiled party machines can grind to a halt in the voting booth. But there was a real issue about democratic accountability and expertise buried in Healy’s earthy assessment, one that Weber was to mull over in his critique of bureaucracy and its relationship to a democratic political order. Among Seligman’s contemporary progressives, it was especially John Dewey who struggled mightily to reconcile the demand for public accountability with the need and requirements for expert knowledge.

The Webers’ tour through the varied urban scene concluded on a high note: an evening with Dr. David Blaustein of the Educational Alliance and a tour of the Yiddish theater in the Bowery District, an institution starting to feel the effects of social change and new forms of entertainment. Like the University and Henry Street Settlements, the Educational Alliance was established as a comprehensive institution for assisting immigrants on their passage into American life. Its focus and clientele was exclusively the Eastern European Jewish population on the Lower East Side, numbering a quarter million, Marianne heard. That estimate was probably low; the U.S. Census Bureau itself recorded 359,000 “Hebrew” immigrants into the city from 1900 to 1904. Blaustein had joined the Educational Alliance as superintendent in 1898, and had quickly set about making it the center of social life for immigrant Jews. Born in Russian Poland and arriving in Boston at age twenty, Blaustein’s life story was an inspiring saga of successful “Americanization”: graduating with honors from Harvard; serving a Providence, Rhode Island, temple as rabbi; holding a position at Brown as assistant professor of Semitic languages; and then entering the top ranks of community activists and social reformers. His challenge at the Educational Alliance was to bridge the divisions in the fractious community, especially those between the orthodox and the reformed tendencies, and between the older generation and youth. His tireless efforts achieved only a mixed result.

For the evening Blaustein and the Webers were joined by Jacob Michailovitch Gordin, the prolific Ukraine-born playwright, for a performance of Di emese kraft (The True Power), with acting that Max found “so magnificent in manner that one completely understood the plot,” which he then described:

A physician who married a “woman of the common folk,” the cultural conflicts, an awakening experience, she becomes unfaithful, but a reconciliation at the death bed of his daughter from a first marriage, for whom she’s caring. The play, which is not flawless, exhibited a few character types (especially a “socialist” and a rabbinical “scholar”) who were splendidly portrayed by the Jewish actors, the best to be found in America, in the most absolute self-caricature. We were of course led behind the scenes to the actors, among them a charming 12 year-old girl, and the gathering with them in the café afterward was quite interesting. (November 19; MWP)

This discussion turned to Yiddish, the community, and Gordin’s astounding productivity: novels, short stories, seventy-three plays, eleven children, and an ambitious goal of writing ten plays for each child. Weber hoped he had persuaded Blaustein, the man he called “our special friend” and “the purest of idealists,” to write an article for the Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik, a hope that unfortunately never materialized.

Blaustein left a strong impression. He had made an effort to achieve the Freemason rank of “master of the chair,” but had to withdraw because of the requirement to defend Christianity. The attempt was justified, he told Weber, because of the moral legitimacy it would have conferred, which could in turn have been useful for contacts when traveling or in dealings with business clients. The story provided another “glimpse into the way in which clubs and orders function” in America, Weber thought, alluding to the episode later in a footnote added to his revised essay “The Protestant Sects.” It reaffirmed a pattern he observed repeatedly in other contexts.

Having far greater significance, however, was Blaustein’s rabbinical training and the line of thought that began to open up in Weber’s mind concerning the relationship between Puritanism or the Protestant sects and Judaism. The Educational Alliance’s program of “Americanization” presupposed a certain level of compatibility or adaptability between the moral universe of the arriving immigrants and the new host culture. Having negotiated the path of adaptation himself, Blaustein was keenly aware of the pitfalls and the practical issues. He mentioned to Weber that at the Educational Alliance “the first aim of the ‘acculturation’ process [Kulturmenschenwerdung], which it tries to achieve by means of all kinds of artistic and social instruction, [is] ‘emancipation from the second commandment’”—that is, the Mosaic Law, Thou shalt not make any graven image! Shedding the commandment seemed a presupposition for adapting to the new “American” identity. Surprisingly, however, the account of Blaustein’s remarks was recorded not in Weber’s correspondence but in the final chapter of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. The allusion to the evening with Blaustein and Gordin is in a lengthy note in which the practical issue of educational policy at the Educational Alliance becomes transposed as a theoretical question about the “characterological consequences,” using Weber’s language, of different religious ethics. Usually Weber restated the question not as one of “characterology” but as an inquiry into the kind of ethos or habitus—the dispositions and ways of conducing one’s life—encouraged by a particular spiritual and moral order. His specific concern was the vocational culture of American life and the sources of its moral legitimacy.

The question about the consequences for the habitus was woven like a bright thread through Weber’s inquiry into the relationship between religious ethics and economic action, and it was enmeshed in the tapestry of his entire sociology of religion. In the final days in New York he had another opportunity to consider the struggle between the reverence for religious tradition and the powerful allure of the “specific and peculiar rationalism” of the modern, though now in relation to the “acculturation” of the immigrant. Turn-of-the-century institutions developed an especially potent approach to forming the new identity of the immigrant citizen, consciously adopting the associational model from American experience. But even so, the practices were worked out on contested terrain in public policy. Today they serve as a reminder of one influential position in a debate about the treatment of the immigrant and cultural differences that continues to provoke debate.

The last two weeks in New York were a quite remarkable tour through the social institutions of the metropolis: Presbyterian and Christian Science churches, the Ethical Culture Society, the University Settlement, the Henry Street Settlement, the Educational Alliance, the School of Philanthropy, the League for Political Education, and the Yiddish theater. Weber had wanted to see the American cities, but he had done much more than that, amassing impressions that would create a vast panorama of a complex and varied sociocultural and political order. Summing up in the last days of their visit, Marianne found the months in the United States “surely by far our most interesting trip” because of the quantity and variety of people they had met and conversed with. Max again pronounced his enthusiasm for the Americans as “a wonderful people,” notwithstanding the social problems and political challenges they had encountered—particularly those of race and immigration.

The Webers boarded the liner Hamburg on November 18 and sailed for Cherbourg, France, the following day. Max Weber’s expectations about returning to the United States were lost in the pressures of work and then were overtaken by a world war. Had he waited a day longer in 1904, he could have heard Woodrow Wilson, then Princeton University’s president, lecturing at the Cooper Union on “Americanism.” Speaking without notes, Wilson sketched the panorama of American history in a few lines:

The processes of the development of our country in the present are not the processes of the past. Our development heretofore has been marked by century periods. Our first century was devoted to getting a foothold on the continent; the second was used up in getting rid of the French; and the third was occupied in the making of the Nation; and now we are in the fourth century of our development. We feel that we do not have to prove that we are the greatest country in the world, but, like the lawyer in the story, we admit it. Heretofore we have been in the process of making; we have just come out of our youth, and we are imbued with all the audacity of youth, and sometimes, I fear, with some of its indiscretions. We have had three centuries of beginnings, and what we need now is not the original strength, but the finished education.

“Audacity” and “indiscretion” are a revealing choice of words, signaling both delight in new energies and concern about unanticipated errors of political judgment. But with the energy and impetuousness of youth in mind, what was to be the model for the Wilsonian national project? The future U.S. president found a ready-made answer in the “typical American” as the mythical citizen who could master the frontier, subdue nature, and create social capital—represented, naturally enough, in the person of Benjamin Franklin. For this new model citizen, “I would name Benjamin Franklin rather than Alexander Hamilton,” Wilson explained, “for Hamilton, much as I admire him, was a transplanted European in his way of thinking. He was not such a man as could have formed a vigilance committee, but Franklin was the man for the frontier. If there wasn’t any way to live, he would have invented one.”

Invoking Weber’s exemplar for the “spirit of capitalism,” Wilson set forth the corollary idea of Americanism as self-reliant worldly action. It was a view of the world and America that emphasized possibility, innovation, command, initiative, self-control, a decisive break with the past. The view merged seamlessly with a “this-worldly” asceticism. For Wilson, after all, mastering the unexpected might require looking to ourselves alone and inventing an entirely new way of life. His extemporaneous message was perfectly pitched. It would be difficult to imagine a more conclusive statement of the American vision of modernity.