Marilou Uy and Shichao Zhou

Recent trends in public indebtedness of developing countries are encouraging: public debt and debt service burdens have been declining on average relative to gross domestic product (GDP). Developing countries are increasingly tapping financial markets to finance their development needs. In the process, they face new creditors—sovereign and private—who have been increasing their exposure to developing countries. These trends promise improved access to external financing; at the same time, they could also raise risks for borrower countries. Understanding these new sources of risk should inform countries’ debt management policies and motivate the global community to further strengthen mechanisms for sovereign debt resolution. The objective of this paper is to provide an overview of the public debt trends of developing countries, especially over the past decade; to examine the challenges of debt management that some groups of countries face; and to discuss the different perspectives within the global community on how to strengthen the system of sovereign debt resolution.

While accelerated growth and deeper fiscal adjustments have contributed to improved debt burdens in developing countries on average, some groups of countries confront distinct challenges in managing sustainable debt levels due to unique vulnerabilities and enormous development needs. Increasing recourse to debt financing from financial markets expands access but might also lead to new sources of risk with the potential for serious consequences for some sovereign borrowers. Countries have a strong role to play in managing their debt relative to their ability to pay, but the global community has complementary responsibilities, for example, in facilitating an effective system for the resolution of sovereign debt issues that arise. Yet there is currently no clear global consensus on what such a system should involve. Even among developing countries, including G-24

1 members, there is a variety of views on how to improve the system for sovereign debt resolution. Further stakeholder consultations will be necessary to understand how best to proceed with this.

The first section of this paper discusses the trends in public debt in emerging markets and developing countries and the changing composition of lenders to sovereigns. The second and third sections discuss, respectively, the debt management challenges of some groups of countries and the diverse and evolving perspectives of countries, especially G-24 members, on options to strengthen mechanisms for sovereign debt resolution, should the need arise. A concluding section wraps up this overview.

TRENDS IN PUBLIC DEBT IN EMERGING MARKETS AND DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

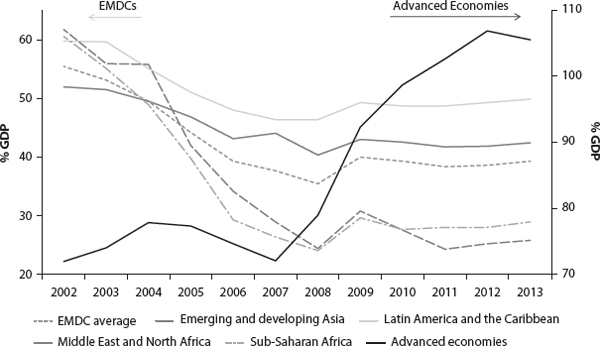

In the last decade, public debt ratios of emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs) have improved by international historical standards, while those of advanced countries have broadly weakened (

figures 2.1 and

2.2). A remarkable feature of this trend is the decline in debt ratios of low-income countries (LICs),

2 a subset of the EMDCs, especially those of heavily indebted poor countries (HIPCs),

3 which dropped considerably. External indebtedness ratios of EMDCs also lessened significantly over the past two decades. Fewer of these countries were classified as severely indebted in 2012 compared with 2000, and the number of countries classified as having low indebtedness

4 more than doubled during the same period.

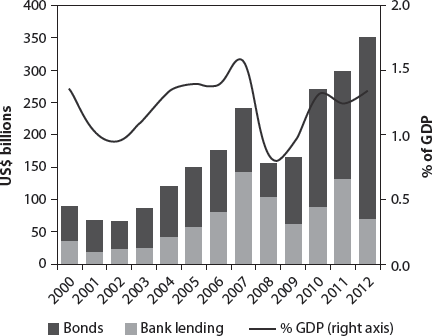

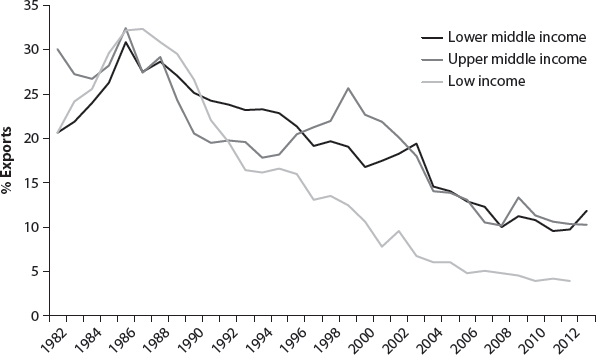

5 Furthermore, the EMDCs’ debt service burden also declined relative to exports of goods and services (

figure 2.3).

The improved debt position of EMDCs has been driven by strong growth and debt relief programs adopted by major creditors under the HIPC initiative. From 2004 to 2014, the output level of EMDCs increased, with growth rates averaging 6.13 percent, thanks to higher levels of investment made possible by an easier external financing environment and abundant global savings. LICs registered average growth of 5.2 percent, while advanced countries as a group grew by only 1.45 percent.

6 By the end of 2012, the total amount of debt relief committed under the HIPC initiative had reached nearly US$57.5 billion for 36 countries (United Nations, 2012). This saw the average share of the external debt stock of all HIPCs decline to less than 30 percent of GDP.

Figure 2.1 Gross government debt as percentage of GDP for advanced countries and EMDCs.

Source: IMF WEO, 2015, April.

Note: Gross government debt refers to all liabilities that require payment or payments of interest and/or principal by the debtor to the creditor at a date or dates in the future. This includes debt liabilities in the form of SDRs, currency and deposits, debt securities, loans, insurance, pensions and standardized guarantee schemes, and other accounts payable (Government Finance Statistics Manual, 2001).

Fiscal adjustment served to improve the debt positions of developing countries as well. Broad public sector reforms were adopted in many EMDCs, including tax policy reforms, rationalization of the public sector, and containment of contingent liabilities. More specific reforms were aimed at raising tax revenues, for example, by broadening the tax base, reducing public expenditures, and improving their efficiency (Tsibouris et al., 2006). Revenue measures provided additional fiscal space, especially in countries with low initial public revenue-to-GDP ratios, though revenue mobilization from natural resources was underutilized. There was scope for rationalizing public expenditures, although concerns were raised on the sustainability of cutting expenditures on social services such as health and education.

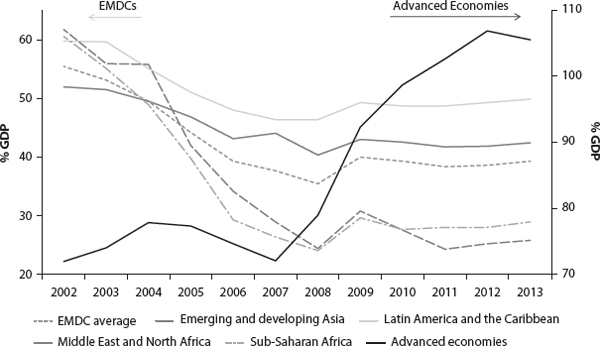

Figure 2.2 Gross government debt as percentage of GDP for G-24 countries.

Source: IMF WEO, 2015, April.

Note: Gross government debt refers to all liabilities that require payment or payments of interest and/or principal by the debtor to the creditor at a date or dates in the future. This includes debt liabilities in the form of SDRs, currency and deposits, debt securities, loans, insurance, pensions and standardized guarantee schemes, and other accounts payable (Government Finance Statistics Manual, 2001).

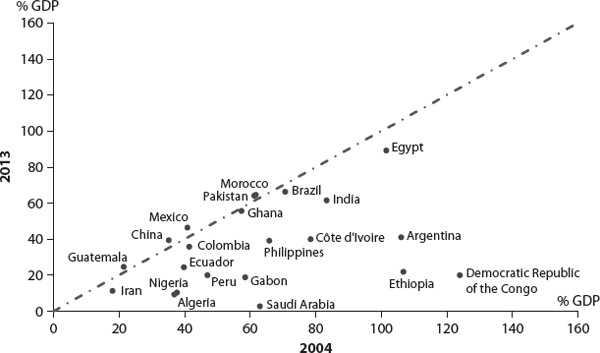

Better economic performance and a changing international financial landscape have improved developing countries’ access to international financial markets. Over the past decade, developing countries’ long-term debt

7 to the international financial market has quadrupled (G20, 2013). Financing through bonds has significantly increased: the ratio of bond financing to GDP in developing countries on average is now considerably more than that of bank financing (

figure 2.4). Between 2006 and 2013, 22 developing countries issued bonds for the first time or returned to the market after a long absence (Guscina, Pedras, and Presciuttini, 2014). Some bond issues were substantial compared to a country’s size and in a few instances amounted to almost 20 percent of GDP (Guscina, Pedras, and Presciuttini, 2014). This trend has also been evident, to a lesser extent, in LICs, which are increasingly turning to bond markets to support their development needs.

8

Figure 2.3 Debt service as percentage of exports.

Source: World Bank International Debt Statistics (2015).

Note: Debt service refers to total debt service to exports of goods, services, and primary income. Total debt service is the sum of principal repayments and interest actually paid in currency, goods, or services on long-term debt; interest paid on short-term debt; and repayments (repurchases and charges) to the IMF.

Figure 2.4 International long-term private debt versus bank lending to developing countries.

Source: G20 (2013).

Developments in domestic financial sectors have also led to the strong growth of local currency bond markets, notably in emerging countries in Asia following the financial crisis of 1997–1998. By 2010, the value of outstanding local currency bonds, most of which were sovereign bonds, had risen to 64 percent of GDP in East Asian developing countries,

9 which far exceeded the share of local currency bond financing in other regions (Baek and Kim, 2014).

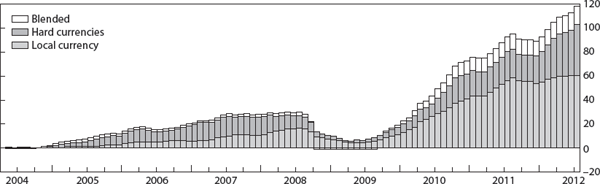

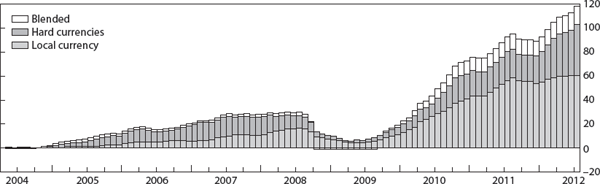

10 This coincided with a strong increase in foreign investors’ investment in emerging market local currency bonds. For the mutual fund sector in particular, the share of local currency–denominated bonds purchased by foreign investors in the emerging economies has risen from almost 0 percent of total cross-border inflows to nearly half by 2012 (

figure 2.5; Miyajima, Mohanty, and Chan, 2012).

The mix of global investors in emerging and developing countries has changed over the past fifteen years with the rise of local-currency bond finance. Compared with official creditors and commercial banks, foreign non-banks have significantly increased their stake in emerging-market sovereign debt. An analysis of developments in the investor base of emerging markets shows that between 2010 and 2012 approximately half of foreign investor inflows went toward purchasing government debt issued in both foreign and local currencies (Arslanalp and Tsuda, 2014). By the end of 2012, it was estimated that foreign non-banks

11 held about 80 percent of the total US$1 trillion worth of government debt owned by nonresidents of emerging markets (Arslanalp and Tsuda, 2014).

12 Indeed, in emerging and developing countries in general, non-residents hold an increasingly important share of government debt.

The changing investor base is a source of both opportunity and new risks. As the creditors become more diversified in terms of country origin and risk tolerance, international risk sharing can be more easily achieved (Stulz, 1999; Sill, 2001). Empirical studies have also shown that the increasing importance of foreign investors is associated with lower financing cost (Warnock and Warnock, 2009; Andritzky, 2012). However, at the same time, countries become more vulnerable to changes in global risk aversion (Calvo and Talvi, 2005) and the “sudden stops or reversals” of financial flows, as well as exchange rate depreciation, which could eventually pose challenges to the stability of local financial markets (International Monetary Fund [IMF], 2014a). Moreover, the diversified investor base has significant implications for negotiations between debtors and creditors during stress episodes. Specifically, under the current system of market-based, ad hoc debt negotiation, the growing presence of varied—and sometimes conflicting—interests can prolong discussions between parties and make resolution more complicated (Pitchford and Wright, 2010).

Figure 2.5 Cumulative net inflows to mutual funds dedicated to emerging-market bonds.

Source: Miyajima, Mohanty, and Chan (2012).

Finally, it is also worth highlighting that the corporate sector in emerging countries increased their borrowing in financial markets. Corporate debt of non-financial firms across major emerging countries grew from $4 trillion to $18 trillion between 2004 and 2014 (IMF, 2015c).

13 In the same period, the average corporate debt to GDP of emerging market rose to more than 70 percent in 2014, although the extent of the increases varied notably across countries (IMF, 2015c). The growth in corporate debt was accompanied by increased reliance on bond issuance, in addition to cross-border lending (IMF, 2015c; Brookings, 2015). These trends have been driven largely by firms taking advantage of the highly favorable global financial market conditions during this period (IMF, 2015c). Greater corporate leverage raises concerns if financial market conditions tighten

14, a lesson learned from previous financial crises in emerging countries that were preceded by rapid growth in credit and corporate leverage. Overall, both governments and firms face risks associated with increased and accelerated access to volatile financial markets.

DEBT MANAGEMENT CHALLENGES: A LOOK AT TWO COUNTRY GROUPINGS

The broadly favorable aggregate public debt trends of developing countries do not reflect the significant challenges that some countries face in managing the sustainability of their debt levels. This section discusses these challenges in two specific groups—LICs and the middle-income countries of the Caribbean.

LOW-INCOME COUNTRIES

LICs historically have had limited access to external financing and have relied mostly on official flows. Achieving debt sustainability, therefore, has depended largely on the willingness of official creditors and donors to provide positive net transfers for new financing. In the 1970s and 1980s, confronted by external debt levels that exceeded their ability to pay and that were exacerbated by vulnerability to external shocks, many LICs turned to internationally agreed debt restructuring and relief mechanisms through the HIPC and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI)

15 mechanisms to regain sustainable debt levels. Most of the debt was owed to multilateral institutions and bilateral lenders of the Paris Club.

16 Debt restructuring, therefore, took place mainly through these multilateral and bilateral channels. Smaller levels of private debt were restructured through debt swaps and buybacks through the London Club, composed of commercial banks (Brooks and Lombardi, 2014).

As already noted, LICs, broadly speaking, have achieved robust economic growth and stronger debt positions over the last two decades, and many have begun to seek out more diverse sources of financing. Maintaining higher levels of growth will require greater access to financing that is not readily available from traditional, concessional financing sources.

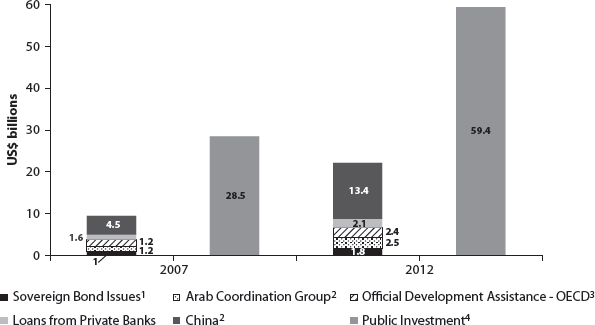

17 In recent years, a number of countries have turned to new country creditors, such as China. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, China’s share of Africa’s infrastructure financing is estimated to have tripled from 2007 to 2012 (

figure 2.6), while the region’s overall spending on infrastructure doubled in the same period (IMF, 2014b). Policy banks, such as the China Development Bank and Export-Import Bank of China, as well as commercial banks, “committed around US$132 billion of financing to African and Latin American governments between 2003 and 2011” (Brautigam and Gallagher, 2014), in addition to grants and interest-free loans made by the Chinese government.

18Some LICs have also started to take on higher-cost, nonconcessional debt from financial markets (

figure 2.7). Debt levels have been rising in many LICs, with external borrowing accounting for most of the increase, although most of these countries remain at a low or moderate risk of external debt distress.

19 A worrisome trend is that about one-third of LICs have high debt levels that are increasing significantly (IMF, 2014f). To manage their debt sustainably, these countries must ensure that borrowed funds are used in projects with appropriate levels of return and must manage challenges associated with the use of private, market-based financing, such as the bunching of repayments and rollover risk (IMF, 2014c).

MIDDLE-INCOME CARIBBEAN COUNTRIES

Middle-income Caribbean countries have unique debt challenges that are difficult to address with traditional policy prescriptions. Public debt levels in these economies are high and continue to rise, with debt burdens well above most major middle-income countries.

20 Despite their middle-income status, a number of macroeconomic characteristics stemming from size make Caribbean economies uniquely vulnerable to growth volatility and debt accumulation, including narrow production bases, higher terms-of-trade volatility, diseconomies of scale, susceptibility to natural disasters and, for some, underdeveloped financial sectors (G-24, 2014). Furthermore, their growth performance was undermined by the global economic and financial crises, and remains below that of other regions. The protracted global recovery also poses substantial risks to their future growth.

Figure 2.6 Sub-Saharan Africa: Public investment and external financing.

Source: IMF, Regional Economic Outlook, Sub-Saharan Africa: Staying the Course, October 2014b.

Notes: 1. Sovereign bonds were issued by sub-Saharan African countries between 2007 and 2012 for financing infrastructure (column 2007 equals the sum of bonds issued by Ghana in 2007 and Senegal in 2009, and column 2012 equals the sum of bonds issued by Senegal in 2011, Namibia in 2011, and Zambia in 2012).

2. Commitments reported by the Infrastructure Consortium of Africa from 2008 to 2012. Members of the Arab Coordination Group: Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development, Islamic Development Bank, Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development, Abu Dhabi Fund for Development, OPEC Fund for International Development, Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa, and Saudi Fund for Development.

3. Estimated disbursement based on the annual share of the commitments for economic infrastructure and services.

4. 75 percent of total public investment is assumed to be allocated to infrastructure each year.

Figure 2.7 Low-income countries: International bond issues.

Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor, 2014, October.

Note: The Volatility Index (VIX) is a popular measure of market’s expectations of short-term volatility. It is published by the Chicago Board Options Exchange.

Notwithstanding these considerable challenges, the middle-income status of these countries excludes them from accessing concessional lending facilities that are typically available to LICs facing debt difficulties. Therefore, these countries clearly need to explore other avenues for achieving debt sustainability. As a last resort, an effective debt restructuring mechanism would be an important option for relieving debt distress.

While this discussion has focused on the debt management challenges confronting LICs and middle-income Caribbean countries, these groups are not the only ones vulnerable to debt distress (Roubini and Setser, 2004; Reinhart and Rogoff, 2013). As mentioned earlier, developing countries have gained increased access to international financial markets, and their broad challenge is to ensure that their debt levels are sustainable and that borrowed funds are used in ways that increase productivity and stimulate growth. In addition, financial markets and business models are evolving in ways that give rise to new sources of risk that could make a growing number of EMDCs vulnerable to debt distress, especially in light of a much more volatile international global financial landscape.

Moreover, in times of sovereign debt distress, coordinating a wider range of traditional and new creditors will pose further challenges to existing global mechanisms for sovereign debt resolution that could harm the effectiveness and timeliness of debt workouts. Countries in general have a stake in improving their frameworks for sovereign debt management and in participating in global efforts to improve mechanisms for sovereign debt restructuring.

PERSPECTIVES ON APPROACHES TOWARD SOVEREIGN DEBT RESOLUTION

While there is strong agreement on the importance of sound debt management and crisis prevention at the country level, there are diverse views on how to move forward on improving the global system for sovereign debt resolution. Within the broader international finance community, there is recognition that the existing system for sovereign debt resolution has shortcomings: collective action among creditors has been difficult to achieve, and debt restructurings have often been “too little, too late” (IMF, 2013). Recent developments in the case of NML Capital, Ltd. v. Republic of Argentina in the U.S. courts have heightened concerns about incentives that exacerbate holdout behavior, which undermine orderly sovereign debt restructuring. Reforming the system for sovereign debt resolution has been an area of long-standing debate in the international arena. It has been difficult to strike a balance between solutions that are acceptable to creditor interests and solutions that will ensure that the value of the underlying asset—that is, the prospects for economic recovery and eventual debt sustainability of the country undergoing debt restructuring—is maintained.

The different views on how to improve sovereign debt restructuring processes are reflected in the deliberations and positions taken in intergovernmental discussions on the reform of the international financial system. The key debate has revolved around the efficacy of market-based contractual approaches versus the need for complementary statutory sovereign resolution mechanisms. These discussions have evolved significantly since they began in 2002. Initially, there was broad support for focusing primarily on market-based contractual approaches that aimed to ensure more effective coordination of creditors during debt stress episodes and sought to prevent holdouts from derailing debt restructuring efforts. In their 2002 communiqué, G-24 ministers and governors expressed a preference for “voluntary, country-specific and market-friendly approaches,” noting that any proposed system for sovereign debt restructuring should not impair developing countries’ access to financial markets (G-24, 2002). The G20 subsequently supported this stance and encouraged discussions among home countries of major creditors and sovereign issuers toward a voluntary code of conduct for sovereign debt restructuring (Martinez-Diaz, 2007). In 2004, the G20 endorsed the Principles for Stable Capital Flows and Fair Debt Restructuring in Emerging Markets, which outlined a voluntary, market-based approach to sovereign debt restructuring between private creditors and sovereign debtors (G20, 2004).

The G20 further encouraged more widespread use of “collective action clauses” (CACs)

21 in sovereign bond contracts issued in foreign jurisdictions (G20, 2003). Supported by the U.S. Treasury (Drage and Hovaguimian, 2004), CACs were encouraged in bonds issued in New York, with Mexico being the first issuer to include them, followed subsequently by a majority of other emerging countries that issued bonds in the New York market. This widened the usage of CACs, which was already a long-standing feature in bonds issued in the London market (Helleiner, 2009). Debtors’ initial concerns that creditors would seek additional risk premiums because of perceived vulnerability if CACs were used have been generally dispelled (Eichengreen and Mody, 2000). The International Capital Market Association/IMF-led improvements of the CACs and clarifications of the pari passu agreements reached in 2014

22 have been broadly welcomed by developing countries and the G20.

23Nevertheless, the shortcomings of the contractual approach are widely acknowledged (United Nations, 2009; IMF, 2014d): they do not address the existing stock of debt, except through gradual reissuance of bonds to introduce CACs; they have not stopped holdout behavior among creditors in some cases of debt restructuring, including the recent experience in resolving Greek bonds that have built-in CACs. Furthermore, difficulties have arisen from differences in court rulings and interpretations on debt restructuring cases across different jurisdictions (for example, the U.S. court’s ruling on Argentina

24 and the decision by the Australian courts upholding the principle of sovereignty vis-à-vis Nauru’s debt servicing of its bonds

25) that indicate an absence, at the global level, of a consistent set of principles necessary for a functional system of sovereign debt resolution. Against this backdrop, more recent views expressed by the G-24 showed renewed concerns about holdout behavior and the losses that result from prolonged sovereign debt workouts, and there was a call for exploring further options to improve the global system of sovereign debt restructuring (G-24, 2014, 2015). The G20, on the other hand, has not in recent years aired its views on the calls for further reform in global governance of sovereign debt restructuring, beyond its support for the strengthened CACs and pari passu clauses. It has, however, hosted joint discussions with the Paris Club, engaging nontraditional official creditors and private sector representatives to foster a continuous dialogue on the future of sovereign debt restructuring mechanisms.

26Discussions on addressing the shortcomings of the existing sovereign debt resolution system have gained momentum among developing countries in recent years. A notable development was the passage of a UN resolution to start negotiations toward a multilateral legal framework for sovereign debt restructuring

27 that was sponsored by the G-77 and China, and supported by most developing countries.

28 In this context, the G-24 welcomed as a positive development the creation of the UN Ad Hoc Committee on Sovereign Debt Restructuring Processes (G-24, 2015) but also called for substantive discussions on the content and nature of possible proposals. The engagement of the United Nations has been viewed as a signal of greater interest from developing countries to address the shortcomings of the existing sovereign debt restructuring regimes and broadens consultations beyond the traditional intergovernmental processes through which sovereign debt resolutions issues have been discussed.

While the role of the United Nations in broadening consultations on possible options to improve sovereign debt resolution is recognized, its role as a potential arbiter of a multilateral statutory sovereign debt resolution system is controversial. Many view the IMF as an effective arbiter in cases of debt distress, given its expertise and continuous involvement in assessing countries’ debt sustainability in the context of its lending framework. Others express concern over potential conflicts of interest, since the IMF is itself also a creditor to sovereigns (Stiglitz, 2006) and instead favor a more prominent role for the United Nations as a neutral entity to provide the oversight and management of a global sovereign debt resolution system.

Approaches discussed within a proposed multilateral statutory framework address critical issues of sovereign debt restructuring that contractual approaches have not resolved. As previously noted, countries’ issuance of bond in various jurisdictions, as well as in hard and local currencies, coupled with the increasing diversity in the investor base of sovereign bonds, will give rise to a multitude of complicated issues, such as bargaining between investors who have bought instruments in different markets and currencies and with different seniorities (see Guzman and Stiglitz, 2016). An independent and universal arbiter would be better positioned to achieve a fair, consistent allocation of debt repayment, thus preventing debt restructuring from becoming a zero-sum, or even negative-sum, game (see

chap. 1). The statutory framework proposals also include provisions to approve payment standstills, providing the time needed to bring creditors together in order to agree on possible debt restructuring solutions (Krueger, 2001; Schneider, 2012). In addition, they address incentives to obtain new financing from private creditors when countries are still in arrears. These features contribute significantly to maximize growth prospects and financial stability of developing countries (Roubini and Setser, 2004), even during times of debt distress, and prevent a debt crisis from becoming an economic crisis (Chodos, 2012).

Despite the reopening of discussions on a multilateral legal framework for sovereign debt resolution, its feasibility remains questionable without the support of major financial centers from which most of the sovereign debt has been issued. In this context, proposals for less formal solutions have emerged as pathways to effect meaningful change.

29 They are classified as “soft law” approaches, whose definition ranges from informal solutions to those that indicate weak obligations (Brummer, 2011). One of the earlier proposals, for example, is the sovereign debt forum (SDF), the objective of which is to bring together creditors, debtors, and other stakeholders so that early, proactive consultations can be made when cases of sovereign debt distress emerge (Gitlin and House, 2014). Equipped with research capacity, the forum would document best practices in sovereign debt restructuring and inform continuous discussions on how to advance reforms in the system of sovereign debt resolution that has historically elicited periodic interest in the international setting. A clear advantage of the SDF is that it could be implemented within existing legal frameworks and would not compete with any of the existing institutions. In conceptualizing the SDF, Gitlin and House (2014) drew lessons from the experience in domestic corporate bankruptcy reforms and other nonpublic forums, such as the Paris and London Clubs, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, which rely more on coordination mechanisms as a means of fostering resolution.

30 Similarly, the success of the SDF will depend on its ability to engage key stakeholders, including all creditors, in ways that would lead to orderly debt resolution.

In the discussions related to the recent 2014 UN-led resolution, options being considered include mechanisms to put into practice sound principles of a sovereign debt workout within a global setting governed by national legislation and in which coordination mechanisms are the norm (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2015). The role of national legislation is gaining more attention, following the UK’s initiative to protect HIPCs permanently from the pursuit of debt enforcement by so-called vulture funds (Government of United Kingdom, 2011) and the Belgian Parliament’s recent proposal to prevent vulture funds from seeking full repayment on defaulting sovereign bonds in Belgium (Wall Street Journal, 2015). Institutional arrangements that facilitate consensual sovereign debt workouts, such as mediation and arbitration, are also being proposed, and further discussion will be required on how to make these operational. These elements of sovereign debt workouts based on coordination and soft law are not mutually exclusive but could collectively serve as building blocks of a workable, principles-based system for sovereign debt workouts.

Although these proposals fall short of a legally binding multilateral agreement, they present meaningful opportunities for more concrete action to improve existing sovereign debt resolution mechanisms. Further consultations with a wide range of stakeholders will clearly be necessary. Among sovereigns, intergovernmental forums such as the G-24, which is composed of developing countries, and the G20, which includes advanced and emerging countries, will broaden consultations among national authorities. While the United Nations primarily engages foreign ministries, the G-24 and the G20—forums consisting of finance ministers and central bank governors—have the standing and expertise for developing and implementing policies for sovereign debt management and resolution. Such involvement would be enormously helpful in defining options and reaching any eventual agreement on approaches to sovereign debt resolution.

In addition, more could be done within intergovernmental forums to engage a wider group of emerging and developing countries to broaden the constituency for reform within the international financial community. While countries have divergent views in the polarized debate over a contractual versus statutory/multilateral sovereign debt resolution system, they may find common ground in defining the global principles for governing sovereign debt workouts and in identifying the institutional mechanisms for effectively achieving orderly and timely resolution.

CONCLUSION

The changing landscape of financing within developing countries has been characterized by improving trends in public debt burdens, increased access to international financial markets, and the rise of nontraditional official creditors. These new sources of borrowing present opportunities for more and better development financing, but they also introduce new sources of risk and consequent challenges to debt management at the country level. In addition, if and when sovereigns encounter episodes of debt distress, coordination between a greater and more varied range of borrowers could further complicate sovereign workout processes. Countries have a stake in addressing the shortcomings of the existing global system of sovereign debt resolution so that it can facilitate debt workout processes that will enable countries to subsequently embark on a path of economic recovery and eventual debt sustainability.

Advanced and developing countries have diverse opinions on how best to reform the global system of sovereign debt resolution. Debate has centered on whether or not there is a need for a multilateral statutory system to complement existing contractual approaches to sovereign debt resolution. In face of the evident shortcomings of existing global systems of sovereign debt resolution, developing countries have called for improvements to the system. In view of the lack of support for multilateral statutory approaches by major financial centers, options along the lines of putting in place the institutions needed to improve coordination during sovereign debt workouts and national legislation in financial centers have come to the fore. By broadening consultations between policy makers and countries, intergovernmental groups will have an important role to play in moving away from a polarized debate and finding common ground on concrete ways to improve future sovereign debt workout mechanisms.

NOTES

REFERENCES

Andritzky, J. R. 2012. “Government Bonds and Their Investors: What Are the Facts and Do They Matter?” International Monetary Fund Working Paper 12/158, Washington, D.C.

Arslanalp, S., and T. Tsuda. 2014. “Tracking Global Demand for Emerging Market Sovereign Debt.” International Monetary Fund Working Paper, Washington, D.C.

Baek, S., and P. K. Kim. 2014. “Determinants of Bond Market Development in Asia.” In Asian Capital Market Development and Integration: Challenges and Opportunities, ed. Asian Development Bank and Korea Capital Market Institute, 286–316. India: Oxford University Press.

Brautigam, D., and K. P. Gallagher. 2014. “Bartering Globalization: China’s Commodity-backed Finance in Africa and Latin America.” Global Policy 5 (no. 3): 346–352.

Brookings Institution. 2015. “Corporate Debt in Emerging Economies: A Threat to Financial Stability.” Washington, D.C.

Brooks, S., and D. Lombardi. 2014. “Sovereign Debt Restructuring: A Backgrounder.” Waterloo, ON: Centre for International Governance Innovation.

Brummer, C. 2011. Soft Law and the Global Financial System: Rule Making in the 21st Century. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Calvo, G. A., and E. Talvi. 2005. “Sudden Stop, Financial Factors and Economic Collapse in Latin America: Learning from Argentina and Chile.” Working Paper 11153, Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Carmichael, J., and Pomerleano, M. 2002. “The Development and Regulation of Non-Bank Financial Institutions.” World Bank Group, Washington, D.C.

Eichengreen, B., and A. Mody. 2000. “Would Collective Action Clauses Raise Borrowing Costs?” Working Paper 7458, Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research.

——. 2013. “Long-Term Investment Financing for Growth and Development.”

Gelpern, A. 2012. “Hard, Soft, and Embedded: Implementing Principles on Promoting Responsible Sovereign Lending and Borrowing.” Geneva: UNCTAD.

Gitlin, R., and B. House. 2014a. “A Blueprint for a Sovereign Debt Forum.” CIGI Working Paper 27. Waterloo, ON: Centre for International Governance Innovation.

——. 2014b. “The Sovereign Debt Forum: A Snapshot.” G-24 Policy Brief.

Guscina, A., G. Pedras, and G. Presciuttini. 2014. “First-Time International Bond Issuance—New Opportunities and Emerging Risks.” International Monetary Fund Working Paper 14/127, Washington, D.C.

Guzman, M., and J. E. Stiglitz. 2015. “A Fair Hearing for Sovereign Debt.” Project Syndicate. March 5.

——. 2016. “Creating a Framework for Sovereign Debt Restructuring That Works.” In Too Little, Too Late: The Quest to Resolve Sovereign Debt Crises, ed. Martin Guzman, José Antonio Ocampo, and Joseph E. Stiglitz, chapter 1. New York: Columbia University Press.

Helleiner, E. 2009. “Filling a Hole in Global Financial Governance? The Politics of Regulating Sovereign Debt Restructuring.” In The Politics of Global Regulation, ed. N. Woods and W. Mattli, 89–120. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

International Monetary Fund. 2001. “Government Finance Statistics Manual.” Washington, D.C.

——. 2002. “Collective Action Clauses in Sovereign Bond Contracts—Encouraging Greater Use.” Washington, D.C.

—— 2013. “Sovereign Debt Restructuring-Recent Developments and Implications for the Fund’s Legal and Policy Framework.” Washington, D.C.

—— 2014a. “Global Financial Stability Report: Moving from Liquidity-to Growth-Driven Markets.” Washington, D.C.

—— 2014b. “Regional Economic Outlook, Sub-Saharan Africa: Staying the Course.” Washington, D.C.

—— 2014c. “Reform of the Policy on Public Debt Limits in Fund-Supported Programs.” Washington, D.C.

—— 2014d. “Strengthening the Contractual Framework to Address Collective Action Problems in Sovereign Debt Restructuring.” Washington, D.C.

—— 2014e. “Fiscal Monitor: Back To Work: How Fiscal Policy Can Help.” Washington, D.C.

—— 2014f. “Macroeconomic Developments in Low-Income Developing Countries.” Washington, D.C.

—— 2015a. “

Debt Relief Under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative.” Washington, D.C.

—— 2015c. October. “Global Financial Stability Report: Vulnerabilities, Legacies, and Policy Challenges.” Washington, D.C.

International Development Association. 2005. “The Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative: Implementation Modalities for IDA.” Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

Krueger, A. 2001. “International Financial Architecture for 2002: A New Approach to Sovereign Debt Restructuring.” Address to the National Economists’ Club annual members’ dinner hosted by the American Enterprise Institute, Washington, D.C.

Martinez-Diaz, L. 2007. “The G20 After Eight Years: How Effective a Vehicle for Developing Country Influence?” Global Economy and Development Working Paper 12, Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C.

Miyajima, K., M. S. Mohanty, and T. Chan. 2012. “Emerging Market Local Currency Bonds: Diversification and Stability.” BIS Working Paper 391.

Morris, S. 2013. “The Paris Club Is Trying to Be Less Clubby and Maybe Just in Time.” Center for Global Development, Washington, D.C.

Pitchford, R., and M. L. Wright. 2010. “Holdouts in Sovereign Debt Restructuring: A Theory of Negotiation in a Weak Contractual Environment.” Working Paper 16632, Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Reinhart, C. M., and K. S. Rogoff. 2013. “Financial and Sovereign Debt Crises: Some Lessons Learned and Those Forgotten.” International Monetary Fund Working Paper 13/266, Washington, D.C.

Roubini, N., and B. Setser. 2004. “New Nature of Emerging Market Crises.” In Bailouts or Bail-Ins? Responding to Financial Crises in Emerging Economies. Washington, D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 70.

Shin, H.S. 2013 November 3-5. “The Second Phase of Global Liquidity and Its Impact on Emerging Economies.” Keynote Address at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Asia Economic Policy Conference.

Sill, K. 2001. “The Gains from International Risk Sharing.” Quarterly Business Review: 23–32. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Penn.

Stiglitz, J. 2006. Making Globalization Work. New York: Norton.

Stulz, R. M. 1999. “International Portfolio Flows and Security Markets.” Working Paper 99-3, Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Tsibouris, G. C., M. A. Horton, M. J. Flanagan, and W. S. Maliszewski. 2006. “Experience with Large Fiscal Adjustments.” International Monetary Fund Occasional Paper 246, Washington, D.C.

—— 2009. “Report of the Commission of Experts of the President of the United Nations General Assembly on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System.” New York.

Warnock, F. E., and V. C. Warnock. 2009. “International Capital Flows and US Interest Rates.” Journal of International Money and Finance 28 (6): 903–919.

Weidemaier, W. M., and M. Gulati. 2013. “A People’s History of Collective Action Clauses.” Virginia Journal of International Law 54: 1. World Bank Group. 2014. “International Debt Statistics.” Washington, D.C.

World Bank Group. 2015. “International Debt Statistics.” Washington, D.C.