2

2

MYSTERIOUS ILLNESSES

HAVE YOU EVER wondered how many human diseases there are? I don’t mean just the infectious ones like influenza, leprosy and bubonic plague, but also noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes and cancer and the many genetic disorders. The question is impossible to answer, since new ones are being identified all the time. The World Health Organization oversees the publication of the International Classification of Diseases, a terrifying compendium of pretty much everything that can go wrong with you. When the first edition of this document appeared in 1893, it identified 161 separate disorders; the tenth, published a century later, listed more than 12,000. By some estimates, doctors now recognize as many as 30,000 distinct diseases, although nobody can agree on even an approximate figure.

Some, such as HIV/AIDS or Ebola, simply did not exist a hundred years ago and emerged as a result of the evolution of new and particularly unpleasant pathogens. Others are being identified only because recent advances in gene sequencing make it possible to locate the precise mutation that causes an otherwise mystifying set of symptoms. Thousands of these conditions are classified as rare diseases, meaning that they affect less than 0.05 percent of the population—and are encountered so infrequently that treatment options are few, and often virtually untested.

Diagnosing a rare condition can pose a challenge to the most talented and experienced clinician, even one with the resources of a modern hospital at their disposal. So it is easy to sympathize with the eighteenth-century physician who visited a family in Suffolk and found them suffering from a strange and terrible disease that made their limbs wither and fall off. The illness was new to England, its cause was unknown and treatment impossible. He could do little more but try to relieve their pain and then set down the symptoms on paper so that his colleagues might recognize them in the future. I find these first encounters between a medic and a never-before-encountered adversary fascinating: You can often sense the doctor’s frustration as they try to work out what they’re up against.

But such descriptions of novel diseases were sometimes written for reasons less nobly scientific. In the seventeenth century, when the Philosophical Transactions and other early journals were founded, natural philosophers took a particular interest in monsters, deviations from the otherwise perfect productions of Nature. One typical article of this period was entitled “A Relation of Two Monstrous Pigs with the Resemblance of Human Faces, and Two Young Turkeys Joined by the Breast.” The desire to understand and study such anomalies was genuine, but these accounts also played to a very human fascination with the grotesque and freakish.

While the study of “prodigies and monsters” fell out of fashion in the eighteenth century, the sensationalist instincts of journal editors persisted for long afterward. A mysterious new disease with exotic symptoms (the weirder the better) almost guaranteed publicity, even if the supporting evidence was shaky. A description of a boy who apparently vomited a fetus was of little clinical value, but it made a terrific story. Most of the strange conditions documented in this chapter were probably genuine, although even the most open-minded expert might demur at the idea that it is possible for a patient to urinate through their ear.

A HIDEOUS THING HAPPENED IN HIGH HOLBORN

Little is known about the seventeenth-century physician Edward May, except that he moved in rather elevated social circles. He came from a distinguished Sussex family that produced numerous MPs, a dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral and several members of the royal household. Edward was himself apparently a regular at the court of Charles I, holding the position of physician-extraordinary to Queen Henrietta Maria. He also taught at the Musæum Minervæ, a sort of finishing school for young noblemen, whose eccentric curriculum ranged from astronomy to riding and fencing.

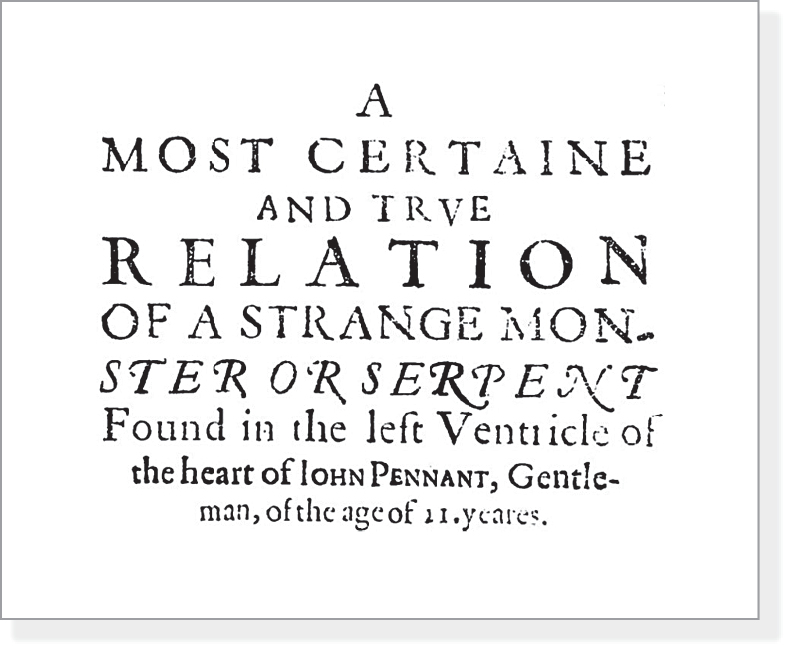

But the most notable episode of Dr. May’s life was an incident so notorious and ghastly that one contemporary, the celebrated Welsh historian James Howell, described it as “a hideous thing that happened in High Holborn.” Dr. May recorded this unsettling experience in a pamphlet published in 1639 under this rather wonderful title:

The unfortunate young patient, John Pennant (deceased), was the scion of an aristocratic Welsh family that could trace its lineage back to the Norman Conquest. Edward May sets the scene:

The seventh of October this year current, 1637, the Lady Herris wife unto Sir Francis Herris Knight, came unto me and desired that I would bring a surgeon with me, to dissect the body of her nephew John Pennant, the night before deceased, to satisfy his friends concerning the causes of his long sickness and of his death; and that his mother, to whom myself had given help some years before concerning the stone, might be ascertained whether her son died of the stone or no?

Dr. May had previously treated the young man’s mother for bladder stones, which were far more prevalent in the seventeenth century than they are today. She naturally wondered whether this was the cause of his death.

Upon which entreaty I sent for Master Jacob Heydon, surgeon, dwelling against the Castle Tavern behind St Clements church in the Strand, who with his manservant came unto me. And in a word we went to the house and chamber where the dead man lay. We dissected the natural region and found the bladder of the young man full of purulent and ulcerous matter, the upper parts of it broken, and all of it rotten; the right kidney quite consumed, the left tumefied* as big as any two kidneys, and full of sanious matter. All the inward and carnouse* parts eaten away and nothing remaining but exterior skins.

Sanious matter means bloody pus. So far, so bad; it sounds as if a catastrophic infection had wrecked his urinary system.

Nowhere did we find in his body either stone or gravel. We ascending to the vital region* found the lungs reasonable good, the heart more globose* and dilated, than long; the right ventricle of an ashen colour shrivelled, and wrinkled like a leather purse without money, and not anything at all in it: the pericardium, and nervous membrane, which containeth that illustrious liquor of the lungs, in which the heart doth bathe itself, was quite dried also.

I like Dr. May’s turn of phrase: “wrinkled like a leather purse” is a vivid description of a diseased heart. The “illustrious liquor of the lungs” is pericardial fluid, whose main function is to lubricate the outer surface of the heart as it beats. In a healthy patient the pericardium, the tough sac surrounding the heart, normally contains a few teaspoons (around 50 milliliters) of this fluid.

The left ventricle of the heart, being felt by the surgeon’s hand, appeared to him to be as hard as a stone, and much greater than the right; wherefore I wished Mr Heydon to make incision, upon which issued out a very great quantity of blood; and to speak the whole verity, all the blood that was in his body left, was gathered to the left ventricle, and contained in it.

A common observation in early autopsy reports was that the major vessels were empty, leading some authorities to suggest that the blood somehow “retreated” to the heart after death. In reality, in the absence of a heartbeat, the blood obeys gravity, sinking to the lowest point of the body. In forensic pathology, this can offer a useful indication as to whether a body has been moved after death. Back to Dr. May:

No sooner was that ventricle emptied, but Mr Heydon still complaining of the greatness and hardness of the same, myself seeming to neglect his words, because the left ventricle is thrice as thick of flesh as the right is in sound men for conservation of vital spirits, I directed him to another disquisition: but he keeping his hand still upon the heart, would not leave it, but said again that it was of a strange greatness and hardness.

Dr. May correctly points out that in a healthy human heart the muscle of the left ventricle, or pumping chamber, is approximately three times thicker than that of the right. This is because it operates at higher pressure, pumping oxygenated blood to the whole body, whereas the right ventricle must propel deoxygenated blood only as far as the lungs. But in this case the left ventricle was even larger than normal. This was almost certainly left ventricular hypertrophy, a thickening of the heart muscle. It has several possible causes, and its presence suggests that the man had been ill for some time, since it takes a while to develop.

Dr. May asked the surgeon to make a larger incision in the ventricle:

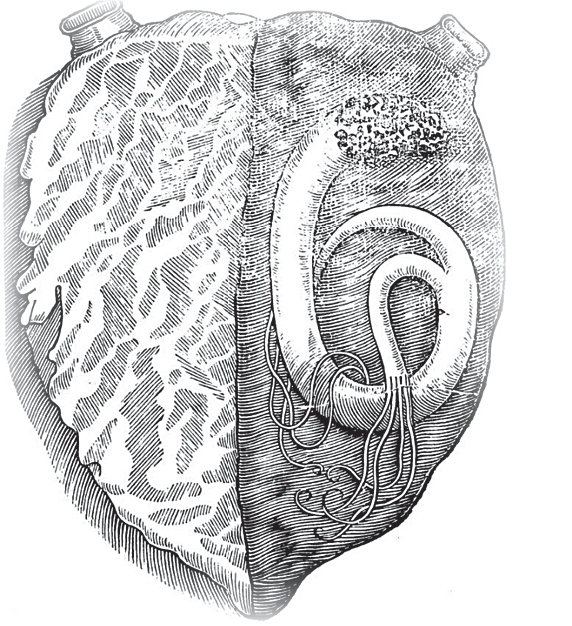

. . . by which means we presently perceived a carnouse substance, as it seemed to us wreathed together in folds like a worm or serpent; at which we both much wondered, and I entreated him to separate it from the heart, which he did, and we carried it from the body to the window, and there laid it out.

When May examined this object in daylight, he had quite a shock.

The body was white, of the very colour of the whitest skin of man’s body: but the skin was bright and shining, as if it had been varnished over; the head all bloody, and so like the head of a serpent, that the Lady Herris then shivered to see it, and since hath often spoken it, that she was inwardly troubled at it, because the head of it was so truly like the head of a snake. The thighs and branches were of flesh colour, as were also all these fibres, strings, nerves, or whatsoever else they were.

I wasn’t aware that snakes had thighs. Dr. May was at first skeptical that a human heart could contain a snake, and wondered aloud whether it might just be a “pituitose and bloody collection”—in other words, a large mass of blood and phlegm. This conjecture we will return to later. He decided to examine the strange creature more closely.

I first searched the head and found it of a thick substance, bloody and glandulous about the neck, somewhat broken (as I conceived) by a sudden or violent separation of it from the heart, which yet seemed to me to come from it easily enough. The body I searched likewise with a bodkin between the legs or thighs, and I found it perforate, or hollow, and a solid body, to the very length of a silver bodkin, as is here described; at which the spectators wondered.

Following the surgeon’s lead, the bystanders took it in turns to probe the “snake” with a metal bodkin, until they were all convinced that the object before them was a worm, serpent or other creature, with identifiable anatomical features including a digestive tract. Evidently aware that they might not be believed, they signed an affidavit confirming what they had seen.

Snake inside the heart of John Pennant, from Edward May’s A most certaine and true Relation (1639)

Was there really a snake inside the young man’s heart, or perhaps a worm? Almost certainly not. You may recall that Dr. May’s first thought was that the strange object was a “bloody collection”; in other words, a large clot. This seems far more likely, and two centuries later, a notable Victorian physician came to the same conclusion.

Benjamin Ward Richardson was a diligent and original researcher who discovered several novel anesthetic agents as well as the first effective drug for the treatment of angina pain, amyl nitrite. He also had a particular interest in the formation of thrombi, or blood clots. In December 1859, he gave a series of lectures* about the formation of “fibrinous depositions”—clots—inside the heart. Richardson noted that thrombi come in all shapes and sizes: Sometimes they form long filaments or even hollow tubes, with blood continuing to flow through a central channel. He suggested that this is precisely what Dr. May had found inside the young man’s heart: a monster clot that had grown to look like some sort of mythical serpent.

Assuming it was a clot, we can now make a tentative guess at a diagnosis. You’ll recall that the original surgeon remarked upon the unusual “greatness and hardness” of the left ventricle of the heart. Not only was the muscle hypertrophied (increased in size), but it had become unnaturally rigid. This is something often seen in the case of a rare blood disorder, hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES), which is also associated with a high risk of extensive clotting in the heart. HES can also attack multiple organs simultaneously, which would explain the state of the young man’s kidneys. It’s impossible to be sure, of course, but the symptoms certainly seem to fit.

You may be wondering what happened to the “serpent” after the postmortem had been completed. Dr. May explains that the surgeon was keen to hold on to it for further study, but the dead man’s mother had other ideas:

The surgeon had a great desire to conserve it, had not the mother desired that it should be buried where it was born, saying and repeating, “As it came with him, so it shall go with him”; wherefore the mother staying in the place, departed not, till she had seen him sew it up again into the body after my going away.

As Nietzsche’s protagonist puts it in Also sprach Zarathustra: “You have evolved from worm to man, but much within you is still worm.”

THE INCREDIBLE SLEEPING WOMAN

Sometime in the 1750s (the precise date is unknown), a group of London doctors decided to get together periodically to discuss their own cases and any novel developments in medical practice. The enterprise was inspired by the foundation in 1731 of the Edinburgh Medical Society, though the London group never acquired a formal name.* It produced an occasional journal, the Medical Observations and Inquiries, intended to disseminate the society’s research to a wider audience. Its purpose was thoroughly modern: to improve medicine through evidence-based research, as the preface to the first volume, published in 1757, explained:

The persons who formed this Society were either such as had the care of hospitals, or were otherwise in some degree of repute in their profession; and consequently had frequent opportunities of making observations themselves, and of verifying, in the course of their practice, the discoveries of others.

One of the cases included in the first installment of the Medical Observations and Inquiries was this strange tale:

Elizabeth Orvin, born at St Gilain, of a healthy robust constitution, served the curate of that place for many years very faithfully, till the beginning of 1738, that she became very sullen, uneasy, and so surly, that the neighbours said she was losing her senses. Towards the month of August, she fell into an extraordinary sleep, which lasted four days; during which time, she took no manner of nourishment, neither was it possible to rouse her.

Mme. Orvin did eventually wake up, but for the next ten years, she routinely slept for seventeen hours a day, from 3 A.M. till 8 P.M., and was usually awake only at night. Dr. Brady visited her in February 1756, and found her fast asleep at five o’clock in the afternoon. She was as stiff as a board and could not be roused:

I put my mouth to her ear, and called as loud as I could, but could not wake her; and to be sure that there was no cheat in the matter, I thrust a pin through her skin and flesh to the bone.

Well, that escalated quickly.

I kept the flame of burning paper to her cheek till I burned the scarff skin,* and put volatile spirits and salts into her nose, and lastly, thrust a little linen dipped in rectified spirit of wine in her nostril, and kindled it for a moment: all this was done without my being able to observe the least change in her countenance, or signs of feeling.

Methods not—as far as I know—currently used by any reputable sleep clinic. Three hours later the woman awoke:

About eight, she turned in her bed, got up abruptly, and came to the fire. I asked her several questions, to which she gave surly answers. She was gloomy and sad, and repeated often, that she would rather be out of the world, than in such a state. I could get no satisfactory account from her, about her sickness; all that I could learn from her was, that she felt a heaviness in her head, which she knew to be the forerunner of her disorder, and which determined her to go to bed, where she lay without once turning, from the time she lay down till her sleep was over, and had, during that time, no sort of evacuation except by perspiration.

On occasions she slept for so long that she had to be fed (while still asleep) through a funnel. The local doctor told Dr. Brady about some of the enterprising, but barbaric, methods they had adopted in attempts to wake her up. These entailed her . . .

. . . being whipped till the blood ran down her shoulders, of her having her back rubbed with honey, and her being exposed in a hot day before a hive of bees, where she was stung to such a degree that her back and shoulders were full of little lumps or tumours. At other times, they thrust pins under her nails, together with some other odd experiments that I must pass over in silence, on account of their indecency.

The mind boggles. Even the mildest of these techniques arguably crosses the line separating therapy from abuse. Nevertheless, she remained, to all appearances, beyond the help of medicine.

This poor woman is now fifty-five years of age, of a pale colour, and not very lean. She never sees daylight, but sleeps out the longest day in summer; and, in winter, begins to sleep several hours before day, and does not awake till two or three hours after sunset.

This seems to have been an isolated case; but what’s interesting about the report is that the woman’s symptoms very much resemble those of Encephalitis lethargica, a mysterious illness that began to sweep across much of the globe at around the time of the First World War. Patients often fell into a deep sleep from which they could not be roused. When epidemiologists looked back through historical records, they found that several similar outbreaks had occurred in earlier centuries. Unexplained bouts of somnolence plagued the residents of Copenhagen in 1657, London in 1673, Germany in 1712 and France in 1776. What caused the illness is unknown, although it often seemed to accompany epidemics of influenza. We’ll never know what was wrong with the Sleepy Woman of Mons. But it’s just possible that she had an unusual variety of flu.

THE DREADFUL MORTIFICATION

A case published in the Philosophical Transactions in 1762 is a reminder of a world we have thankfully left behind: one in which disease could rapidly maim or kill entire families, while doctors looked on helplessly. Life was often, in the philosopher Thomas Hobbes’s phrase, “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.” Hobbes was writing about war, but disease was as formidable an enemy as the eighteenth century could muster.

This report was written by Charlton Wollaston, a twenty-nine-year-old who had just been appointed physician to the queen’s household. His promising career was cut tragically short two years later when he died from a fever. His daughter Mary later attributed his death to blood poisoning contracted when “opening a mummy, he having previously by accident cut a finger.”

John Downing, a poor labouring man who lives at Wattisham, a small village about sixteen miles from Bury, in January last had a wife and six children; the eldest a girl of fifteen years of age, the youngest about four months. They were also at that time very healthy, as the man himself, and his neighbours, assured me. On Sunday 10th January, the eldest girl complained in the morning of a pain in her left leg; particularly in the calf of the leg. Towards evening the pain grew exceedingly violent. The same evening another girl, about ten years old, complained of the same violent pain in the leg. On the Monday the mother and another child, and on the Tuesday all the rest of the family, except the father, were affected in the same manner. The pain was exceedingly violent; insomuch, that the whole neighbourhood was alarmed with the loudness of their shrieks.

Chilling. This was a rapid, insidious and deeply unpleasant complaint. Dr. Wollaston visited the family and questioned them in detail about the progress of the disease.

In about four, five, or six days, the diseased leg began to grow less painful, and to turn black gradually; appearing at first covered with spots, as if it had been bruised. The other leg began to be affected, at that time, with the same excruciating pain, and in a few days that also began to mortify.

To “mortify” means to become gangrenous: The leg discolored and then went black as the tissue died.

The mortified parts separated, without assistance, from the sound parts, and the surgeon had in most of the cases no other trouble than to cut through the bone, with little or no pain to the patient.

The summary that follows is simply written, but brutal in its impact.

Mary, the mother, aged forty. The right foot off at the ankle; the left leg mortified, a mere bone; but not off.

Mary, aged fifteen. One leg off below the knee: the other perfectly sphacelated,* but not yet off.

Elizabeth, aged thirteen, both legs off below the knees.

Sarah, aged ten, one foot off at the ankle.

Robert, aged eight, both legs off below the knees.

Edward, aged four, both feet off at the ankles.

An infant four months old, dead.

Only the father escaped relatively unscathed: A couple of fingers became stiff and useless, but his lower extremities were not affected.

It is remarkable, that during all the time of this calamity, the whole family are said to have appeared in other respects well. They ate heartily, and slept well when the pain began to abate. When I saw them, they all seemed free from fever, except the girl, who has an abscess in her thigh. The mother looks emaciated, and has very little use of her hands. The rest of the family seemed well. One poor boy, in particular, looked as healthy and florid as possible, and was sitting on the bed, quite jolly, drumming with his stumps.

A poignant image that wouldn’t be out of place in a Dickens novel. Dr. Wollaston did his best to establish the cause of this unusual complaint, but eventually had to admit defeat. A local clergyman with a bleakly appropriate name, the Reverend Mr. Bones, offered to make further inquiries. He questioned the family minutely about where they bought their food and drink, and even examined their cooking implements. But he, too, drew a blank:

I have taken all the pains I can to inform myself of every circumstance which may be deemed a probable cause of the disease, by which the poor family in my parish has been afflicted. But I fear I have discovered nothing that will be satisfactory to you.

John Downing himself attributed his family’s misfortune to witchcraft, a suggestion that the priest naturally discounted. Dr. Wollaston came closest to solving the problem when he made this observation:

The corn with which they made their bread was certainly very bad: it was wheat, that had been cut in a rainy season, and had lain on the ground till many of the grains were black and totally decayed; but many other poor families in the same village made use of the same corn without receiving any injury from it.

An editor at the Philosophical Transactions then made a connection that Dr. Wollaston had missed: Half a century earlier, a French surgeon had noticed something strikingly similar. In an article published in 1719, Monsieur Noël, a surgeon from Orléans, wrote that he . . .

. . . had received into the hospital more than fifty patients afflicted with a dry, black and livid gangrene which began at the toes, and advanced more or less, being sometimes continued even to the thigh.

This aroused great interest when M. Nöel presented his findings to the members of the French Royal Academy of Sciences.

The gentlemen of the academy were of opinion, that the disease was produced by bad nourishment, particularly by bread, in which there was a great quantity of ergot.

Hitting the nail right on the head. Ergot is grain that has been infected by a parasitic fungus, Claviceps purpurea. The tainted grain takes on a dark blue-black hue and contains toxic chemicals that are unaffected by heat, so baked foodstuffs such as bread are still dangerous to eat. The toxins can even be passed from mother to child via breast milk, which explains the death of John Downing’s infant son. Dr. Wollaston’s article is a classic description of the symptoms of gangrenous ergot poisoning.

In October 1762, six months after his first visit, Dr. Wollaston returned to John Downing’s house. He was pleased to find that John’s wife, Mary, was still alive:

In my former account . . . I mentioned that one of her feet had separated at the ankle, and that the other leg was perfectly sphacelated to within a few inches of the knee, but not then taken off. Some little time afterwards the husband broke off the tibia, which was quite decayed, about three inches below the knee: the fibula was not decayed, so the surgeon sawed it off.

Cases of ergotism are still encountered from time to time, but, thankfully, such scenes of horror are long gone.

THE HUMAN PINCUSHION

In 1825, a doctor from Copenhagen published a case so incredible that he felt it necessary to point out that thirty of his colleagues could corroborate the story. Dr. Otto’s article appeared originally in a German journal, but the editors of the Medico-Chirurgical Review then translated it for the benefit of an English-speaking audience:

Rachel Hertz had lived in the enjoyment of good health up to her fourteenth year; she was then of a fair complexion, and rather of the sanguineous temperament.

At this period many physicians still believed in four “temperaments,” or personality types. This was a relic of the ancient idea of the four humors, which had dominated medicine at least since the era of Hippocrates in the fourth century BC. According to humoral theory, disease was caused by imbalance among four bodily fluids, or humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile). The “sanguineous” temperament was associated with an abundance of blood; one early-nineteenth-century doctor wrote that “people of this temperament are usually very strong, and all their functions are extremely active.”

In August 1807, she was seized with a violent attack of colic, which induced her to apply to Professor Hecholdt, and this was the first acquaintance which the Professor had with the case. From that time to March 1808 she experienced frequent attacks of erysipelas* and fever, which left her in a very debilitated state. Many symptoms of an hysterical character showed themselves, but which the ordinary remedies failed to remove. From March to May 1809, a period of fourteen months, she suffered in this way from repeated and violent hysteric attacks, accompanied with, or rather followed by, fainting, which sometimes continued so long that people considered her dead. Occasionally she was attacked with epileptic fits, at other times with drowsiness and hiccough, and sometimes with delirium.

The next development says a lot about the leisure habits of educated Danish teenagers in the early nineteenth century. I don’t suppose many modern patients are troubled by this symptom:

During the paroxysms of her madness, she delivered, with a loud voice and correct enunciation, long passages from the works of Goethe, Schiller, Shakespeare, and Oehlenschläger, just as accurately as any sane person could do, and although she kept her eyes closed, she accompanied the declamation with suitable gesticulations.

Another journal, in its report of this case, included “long fits of theatrical recitations from tragic poets” in its description. The association between Romantic literature and mental illness was quite genuine: After the publication of The Sorrows of Young Werther in 1774, young men started to dress like Goethe’s tragic hero and even emulate his melancholic behavior, causing such alarm at the possibility of copycat suicides that several countries banned the book. There is no suggestion, however, that this was what ailed poor Rachel Hertz:

The delirium continued to increase until it assumed a very alarming height; she gnashed her teeth, kicked about, and fought with whatever came in her reach, and disturbed with her ravings, not only her own household, but the whole neighbourhood.

The girl’s obvious mental distress was now compounded by physical ailments: Constipation and difficulty in urinating necessitated the daily use of a catheter. Most seriously, she began to vomit blood. The fits of mania began to retreat, and she sank into a stupor from which, apparently, nothing would rouse her.

In May 1809, Professor Collisen was consulted, who during the lethargic state of the patient recommended snuff to be pushed up her nostrils, the effect of which was so favourable that, without sneezing, she soon came to her senses. She complained of nothing during that day, and the snuff frequently produced equally good effects, for a time only. The delirium continued from May 1809 to December 1810, with little variation of importance, and then gradually subsided.

She remained in much better health for the next few years, apart from one brief relapse. Until January 1819, when

severe colic pains made their appearance, with fever, vomiting of blood, and purging of black faecal matter, from which it was considered impossible that she could recover—but recover she did. On examination of the abdomen, a large tumour was found, having three distinct elevations just below the umbilicus.

Soothing dressings were placed on this swelling, but to no avail. In desperation, Professor Hecholdt decided to open the tumor with the scalpel. And this is where things started to get really interesting.

It was expected that a copious discharge of pus would follow, but no pus came, and the bleeding was very slight. When the wound was examined with a probe, a curious sensation was communicated to the hand, just as if a metallic body had been thrust against the probe; this was repeated, a forceps was introduced, the substance was laid hold of, and, to his great astonishment, out came a needle. The extraction of this needle produced some alleviation of the sufferings of the patient, but it was of very short duration; great pain with vomiting of blood returned, another tumour appeared in the left lumbar region, the touching of which caused great uneasiness. On the 15th of February, an incision was made into it, and another black oxidised needle drawn out.

Similar lumps started to emerge all over the young woman’s body. Each time one appeared, the doctors cut it open, always with the same result:

From the 12th of February 1819, to the 10th of August 1820, a period of eighteen months, severe pains, followed by tumours, were felt in various parts of the body, from which two hundred and ninety-five needles were extracted, viz.—

From the left breast, 22; from the right breast, 14; from the epigastric region, 41; from the left hypochondriac region, 19; from the right hypochondriac region, 20; from the umbilicus, 31; from the left lumbar region, 39; from the right lumbar region, 17; from the hypogastric region, 14; from the right iliac region, 23; from the left iliac region, 27; from the left thigh, 3; from the right shoulder, 23; between the shoulders, 1; from under the left shoulder, 1.

Total—295.

Between August 1820 and March 1821, no further needles appeared; assuming his patient was cured, Professor Hecholdt wrote a pamphlet (in Latin, naturally) documenting the strange facts of the case. But this turned out to be premature:

A large tumour formed in the right axilla,* from which, between the 26th of May and the 10th of July, 1822, no less than one hundred needles were taken out! From the 1st of July, 1822, to the 10th of December, 1823, five needles were at different times extracted, making the total number of FOUR HUNDRED!!

The emphasis is in the original; the author could barely contain his excitement.

The patient has amused herself during her convalescence by learning Latin, and writing a journal of her own case. She is at present living at Frederick’s hospital, at Copenhagen, and enjoys good health.

Oddly, the article in the Medico-Chirurgical Review does not attempt to explain the emergence of several hundred needles from different parts of the patient’s body. Incredible as it may seem, the most likely explanation is that she had swallowed them. She probably had an eating disorder called pica, in which the patient compulsively ingests inedible objects such as soil or paper. Once inside the body, needles have a nasty habit of piercing the walls of the digestive tract and then migrating all over the body. This would explain the girl’s stomachaches, her vomiting of blood, and finally the dramatic appearance of rusty needles everywhere from her armpits to her thighs. Not until the era of punk would so many dodgy piercings again be seen on a single human body.

THE MAN WHO FOUGHT A DUEL IN HIS SLEEP

If you’ve ever shared a house with a habitual sleepwalker, you may be familiar with the strange experience of having a conversation at 2 A.M. with somebody who is fast asleep. One of my sisters went through a sleepwalking phase in childhood, and we soon became used to guiding her back to her bedroom, while saving the weirdest of her utterances for gleeful quotation at breakfast the next morning.

But as somnambulists go, it turns out that she was a mere amateur. In 1816, a London medical journal told the story of a Dutch student identified only as Mr. D.:

In 1801, young Mr. D. went to stay as a paying guest at the home of the Reverend Mr. H., a respectable priest with a young family. On his arrival he warned his hosts that he sometimes walked in his sleep; they were not to be alarmed if he did so. A few nights later the clergyman was woken by an unusual noise, and went downstairs to investigate:

I found Mr D. in his sleep taking down some of his books, which had been sent him by his parents. I stayed in the room some time, not choosing to wake him on the sudden. On further examination, I perceived he was employed in making a catalogue of them quite in the dark, and with as much precision as I could have done with a light; making no mistakes with regard to the titles of the books, the names of their authors, their respective editions, and where they were printed. On letting one of the books fall, the noise appeared to have startled him, and he hastily retired to bed.

The next morning, the young man had no memory of the incident. He was capable of surprisingly elaborate tasks while asleep: He played chess and cards, and once wrote a letter to his professors—in Latin.

At another time, when he was to deliver a Latin oration in public, we heard him in his somnambulant state rehearse it aloud, as though the curators of the school were present; and as he was feeling for the desk to lay his thesis upon, Mr H. stooping a little before him, he laid it upon his neck, supposing it to be the rostrum. When he had finished his oration, he bowed to the audience and to the curators, as if present, and then retired.

On another occasion after he had gone to bed, the landlord’s daughter began to play the piano. Mr. D. arrived in the room with a score, pointed to a favorite piece and placed it on the music stand for her to play. When she had done so, Mr. D. and the family all applauded. He then left the room hurriedly, having apparently just woken up and realized that he was undressed.* For the most part, his behavior when asleep was calm and rational, although there was one notable occasion when this was not the case:

He supposed one night that he must fight a duel with one of his former fellow-students at Utrecht, and asked Mr H. to be his second; the hour was fixed, the ground measured, and when the signal was given, down fell Mr D. as mortally wounded, and requested to be put to bed, and a surgeon to be sent for immediately. As a surgeon of our acquaintance desired to see him in his somnambulant state, we sent for him. When he asked Mr D. where he was wounded, he put his hand to his left side, saying “here, here—here is the ball.” “I am come to extract it,” said the surgeon; “but before I begin the operation, you must take some of these drops which I have brought with me.” After that, making some great pressure upon the side where Mr D. said he was wounded, the surgeon said the ball was out. Mr D. felt at his side— “so it is,” he said; “I thank you for your skilful operation. Is my antagonist dead?” he asked; and when they told him he was living, joy beamed in his countenance; and it appeared as if that joy awakened him.

Quite a yarn. The editor of The London Medical Repository evidently feared it might be thought a bit too good, since he appended to it this wry little footnote:

This letter was put into our hands by a practitioner of great respectability, with the assurance that he could vouch for the authenticity of the facts it details, being personally acquainted with the writer, who is a clergyman in Holland of high character and undoubted veracity. The facts are of so very singular a description, that, notwithstanding the source from which they proceed, we conceive it proper to give them to our readers accompanied by this testimony: we leave them to the degree of credence to which they may be considered entitled.

Quite.

THE MYSTERY OF THE EXPLODING TEETH

This engaging little mystery first appeared in the pages of Dental Cosmos—the first American scholarly journal for dentists, founded in 1859. I love the title; imagine going into your local store and asking for “a pint of milk and Dental Cosmos, please.” In one of its early issues, W. H. Atkinson, a dentist from Pennsylvania, wrote to the journal to report three strange and similar cases that he had encountered over a period of forty years in practice.

The first of his subjects was the Reverend D.A., who lived in Springfield in Mercer County, Pennsylvania. In the summer of 1817, he suddenly developed an excruciating toothache.

At nine o’clock a.m. of August 31st, the right superior canine or first bicuspid commenced aching, increasing in intensity to such a degree as to set him wild. During his agonies he ran about here and there, in the vain endeavor to obtain some respite; at one time boring his head on the ground like an enraged animal, at another poking it under the corner of the fence, and again going to the spring and plunging his head to the bottom in the cold water; which so alarmed his family that they led him to the cabin and did all in their power to compose him.

This is not terribly dignified behavior for a clergyman. That toothache must have hurt a lot.

But all proved unavailing till at nine o’clock the next morning, as he was walking the floor in wild delirium, all at once a sharp crack, like a pistol shot, bursting his tooth to fragments, gave him instant relief. At this moment he turned to his wife, and said, “My pain is all gone.”

To be fair, so was his tooth.

He went to bed, and slept soundly all that day and most of the succeeding night; after which he was rational and well. He is living at this present time, and has vivid recollection of the distressing incident.

The second case took place thirteen years later; the sufferer this time was a Mrs. Letitia D., from Mercer County in Pennsylvania:

This case cannot be so clearly or fully traced as case first, but was much like it, terminating by bursting with report, giving immediate relief. The tooth subsequently crumbled to pieces; it was a superior molar.

A final example occurred in 1855, also in Mercer County (was it something in the water?), the victim a Mrs. Anna P.A.:

This had a simple antero-posterior split, caused by the intense pain and pressure of the inflamed pulp. A sudden, sharp report, and instant relief, as in the other cases, occurred in the left superior canine. She is living and healthy, the mother of a family of fine girls.

Though it’s good to know that she’s well and has a family, I doubt many readers would have been expecting a minor dental incident to be life-threatening.

Dr. Atkinson’s report seems to have presaged a mini epidemic of detonating dentine, as a number of similar cases came to light over the next couple of decades. In a book published in 1874, Pathology and Therapeutics of Dentistry, J. Phelps Hibler described one particularly striking example. His patient was a woman whose tooth was aching so badly that she felt she was losing her wits:

All of a sudden the raving pains eased up greatly; having been walking the floor for several hours, she sat down a moment or two to take some rest. She averred that she had all her senses unimpaired from the moment aching ceased; all at once without any symptom other than the previous severe aching, the tooth, a right lower first molar, burst with a concussion and report that well-nigh knocked her over.

The tooth was split through from top to bottom, the impact of the explosion “rendering her quite deaf for a considerable length of time.” It was as if a firecracker had gone off inside her mouth.

If we are to believe such accounts, these were quite dramatic explosions. So what might have caused them? In his original article, Dr. Atkinson suggested that a substance that he called “free caloric” was building up inside the tooth and causing a dramatic increase of pressure. This hypothesis can be ruled out straight away, since it relies on an obsolete scientific theory. For many years, heat was believed to consist of a fluid called caloric, which was self-repelling—although this would make a pressure increase plausible, we now know that no such fluid exists. J. Phelps Hibler had a different idea: He believed that caries (tooth decay) inside the dental pulp generated flammable gases that eventually exploded. But this is no more plausible, since we now know that caries is a process that starts on the outside of the tooth, not its interior.

Several other theories have since been proposed and rejected, ranging from the chemicals used in early fillings to a buildup of electrical charge. The most likely explanation seems to be that the patients were exaggerating symptoms that were far more mundane. Teeth do sometimes split if you bite into something hard, and the noise it makes can seem quite dramatic if it’s inside your own jaw. But even this fails to explain the “audible report” claimed by several witnesses; like the fate of the Mary Celeste, or the identity of Jack the Ripper, all remains shrouded in obscurity. For now, at least, it seems that the mystery of the exploding teeth will remain unsolved.

THE WOMAN WHO PEED THROUGH HER NOSE

Dr. Salmon Augustus Arnold, an obscure general practitioner from Providence, Rhode Island, has not left much of a mark on history. He does have one claim to immortality, however: a perplexing report that he provided for The New England Journal of Medicine and Surgery in 1825. It reads like a Rabelaisian version of The Exorcist, complete with horrifying plot twists and inexplicable bodily fluids. Dr. Arnold believed he had identified a rare illness new to science, which he called paruria erratica—a Latin phrase meaning “wandering disorder of urination.” A strange name, but curiously apt:

Maria Burton, aged 27 years, of sound constitution, generally enjoyed good health until June 1820, when she was afflicted with a suppression of the catamenia accompanied with haemoptysis.

Translated into English: She had missed her period and was spitting blood.

The physicians in attendance, irregular practitioners, bled her profusely every other day, and after the system had become greatly debilitated, injudiciously administered emetics, the operation of the last of which was succeeded by a prolapsus uteri, and a total inability to perform the function of urinary secretion. In this state she continued for nearly two years and a half without any alleviation of the disease, though for the most part of the time under the care of respectable physicians.

A prolapsed uterus occurs when the muscles and ligaments holding it in position in the abdomen weaken and stretch. The organ then slips down into the vagina. A common complication of the condition is a prolapsed bladder, causing inability to urinate, which is clearly what had happened in this case. It was now necessary to insert a catheter into her bladder once a day to draw off the urine. This is where things started to turn very . . . weird.

In September 1822, soon after I first saw her, the urine not having been drawn off by the catheter for seventy-two hours, found an outlet by the right ear, oozing drop by drop, and continued for several hours after the bladder had been emptied. The next day at five o’clock pm it again commenced and continued about as long as on the day preceding, but a larger quantity was discharged. This was thrown on to a heated shovel, and gave out the odor so peculiar to urine, indicating the presence of urea.

The “heated shovel test” is inexplicably no longer a part of conventional diagnostic practice. The discharge of urine from the ears continued, becoming more frequent each day. It was, reports Dr. Arnold,

increasing gradually in quantity, and being discharged in less time, until a pint was discharged in fifteen minutes in a stream about the size of a crow quill; then becoming more irregular, being discharged every few hours, and increasing in quantity, until eighty ounces were discharged in twenty-four hours.

That’s four pints, more than the average person urinates in a day. New symptoms then appeared: She started to suffer from spasms and “swooning.” At times she would laugh, sing and talk incoherently, though “frequently with an unusual degree of wit and humor”; at others she remained catatonic for up to twelve hours. And worse was to come.

The sight of the right eye was soon destroyed, and frequently that of the left was so impaired that she could not distinguish any object across the room, but the latter is now entirely restored. The hearing of the right ear is so much impaired that she cannot distinguish sounds, and there is a constant confused noise heard by her like the roaring of a distant waterfall.

Strangely, this imaginary waterfall soon turned into the real thing:

The next outlet the urine found was by the left ear, a few moments previous to which discharge, a similar noise is heard to that noticed in the right ear: she cannot hear distinctly for ten or fifteen minutes previously, and after the urine passes off. Soon after the discharge from the left ear, the urine found another outlet by the left eye, which commenced weeping in the morning and continued for several hours, producing considerable inflammation.

Look, this is getting ridiculous. But wait, there’s more.

On the 10th of March, 1823, urine began to be discharged in great quantities from the stomach, unmixed with its contents. On the 21st of April, the right breast became tense and swollen, with considerable pain, and evidently contained a fluid, a few drops of which oozed from the nipple. Urine has been discharged occasionally from the left breast.

So far, we have urine coming from both ears, both eyes, the stomach and both breasts. There can’t be any more orifices left, surely? There can:

May 10th, 1823: the abdomen about the hypogastric and umbilical region became violently and spasmodically contracted into hard bunches, and a sharp pain was felt shooting up from the bladder to the umbilicus, around which there was a severe twisting pain; in a few days subsequently a loud noise was heard, similar to that produced by drawing a cork from a bottle, and immediately afterwards urine spirted out from the navel, as from a fountain.

The poor woman’s experience sounds pretty ghastly, but you have to admit that a fountain of urine gushing from her navel must have been quite a sight. Incredibly, the pièce de résistance was yet to come:

Nature wearied in her irregularities, made her last effort, which completed the phenomena of this case, and established a discharge of urine from the nose. This discharge commenced on the 30th of July, 1823, oozing in the morning guttatim* and increasing in quantity every day until it ran off in a considerable stream.

Was the liquid really urine? Dr. Arnold sent several samples to a professor of chemistry, who analyzed them and confirmed that they contained a high proportion of urea, an organic waste product found in normal urine. The next obvious question: Was this phenomenon genuine, or was the woman faking it somehow?

To remove every doubt, I and my friend Dr. Webb, who at my request had occasionally attended her, remained with her four hours alternately, during twenty-four hours, and the quantity discharged during this time was as large as it had been for several days previous to, and after this period. There has never been any doubt that these fluids, which have been proved to be urine, were actually discharged from the ear and the other outlets, since the fact has been proved, day after day, by ocular demonstration.

The doctor could have written “I saw it myself” but decided that the gratuitously highfalutin “by ocular demonstration” sounded better. So what happened to her? The story has a happy ending—of a sort:

This great disturbance in the system continued to increase for nearly six months, and it was the opinion of all who saw the patient that she could not survive from day to day; after which period it gradually abated, and she is now, when the urine is freely discharged, so much relieved that she is able to walk about her room, and during the summer of 1824 frequently rode out. The discharges from the right ear, the right breast and navel continue daily, but they are not so great nor so frequent as they were a year since; from the bladder the quantity is as usual; from the stomach, nose, eye, there has for some months been no discharge.

Not ideal: A tendency to urinate spontaneously from the ear does not make one the perfect dinner-party guest. The report concludes with what Dr. Arnold calls a “diary of the discharges”: a heroic, seventeen-page document recording how much urine the patient produced each day over a nine-month period, as well as the orifice(s) from which it emerged.

If you’re thinking the whole thing sounds too far-fetched to be true, you’re probably right. But there is just the faintest chance that Maria Burton was suffering from an exotic combination of conditions with bizarre symptoms. We know that her illness began with a prolapsed uterus, which caused an obstruction to the urinary tract. If the body can’t get rid of its waste products in the urine, the blood can become saturated with urea, a condition known as uremia. Typical symptoms include fatigue, abnormal mental state and tremors, all of which were present in this case. But the most striking feature of uremia, seen only in patients with kidney failure, is uremic frost, in which urea passes through the skin and crystallizes. When dissolved in sweat, it produces a liquid that smells and looks like urine. And if she was suffering also from edema—a buildup of fluid in the tissues—this smelly perspiration might have been quite copious.

Ah, but what of the urine that “spirted out from the navel, as from a fountain”? Astonishingly, there may be a rational explanation for that, too. The bladder is connected to the navel by a structure called the urachus, the vestigial remnant of a channel that drains urine from the fetal bladder during the early months of pregnancy. This tube usually disappears before birth, leaving just a fibrous cord, but very occasionally it persists into later life.* When the channel is very narrow, it may not be noticed, but if pressure builds up in the bladder, urine can be forced through the opening and out through the belly button.

Case closed? Not exactly. A patient with such severe uremia would be lucky to survive for six months, let alone two years. And that’s not the only problem. It is not just unlikely but physiologically impossible for urine to be discharged from the ear, or from the nose for that matter.* Either Maria Burton was the only person in medical history to have peed through her nose or she was very good at faking it. And I know which of the two is more likely.

THE BOY WHO VOMITED HIS OWN TWIN

This delightful case was originally reported in a Greek newspaper in 1834, and quickly caused a sensation in the European medical press. Pierre Ardoin, a French doctor who had settled on the Aegean island of Syros, was summoned by the worried parents of a young boy called Demetrius Stamatelli who had fallen ill. This is how one London journal reported the tale:

On the 19th July last, when M. Ardoin was called to see this youth, he found him suffering from acute pains in the abdomen. He prescribed several remedies, none of which in the least assuaged his torments, and he so far gave up all hope of saving the patient that he recommended the administration of the sacrament.

Either Dr. Ardoin detected some signs of improvement or the parents took violent exception to his giving up on their son, because he soon decided that there were more useful things he could do for the boy than arrange the last rites.

The next day he gave him an emetic cathartic, which produced at first slight vomiting.

The “emetic cathartic” was a vile-sounding concoction of castor oil, coralline* and ipecacuanha.* Its effects would not have been pretty, since it was intended to provoke both vomiting and diarrhea.

This lasted a short time, when the vomiting returned with excessive pain, and at length he vomited a foetus by the mouth.

OK. He vomited . . . a fetus?

The head of the foetus was well developed, also one arm perfectly formed; it had no inferior extremities, but merely a fleshy prolongation, thin at the extremity, and attached to the placenta by a kind of umbilical cord. Three days afterwards the patient was much better, all the morbid symptoms were diminished, and he has since continued to improve.

Dr. Ardoin took the unexpected object home and invited all the other doctors of Syros to join him in examining it, after which it was preserved in alcohol. “I made it thus public,” writes Dr. Ardoin, “so that it might not be considered a deception.”

Sure enough, there were many who doubted the veracity of Dr. Ardoin’s account. Members of the Academy of Sciences in Paris were suspicious of the “extreme zeal” with which he had publicized the case, and asked the distinguished naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire to investigate further. Saint-Hilaire had a particular interest in teratology, the study of congenital deformities, so was ideally qualified for this task. He arranged for the preserved fetus to be sent to him in Paris and, after dissecting it, pronounced himself satisfied that it was indeed a partially formed human fetus.

In the meantime, the young patient Demetrius Stamatelli had died, from causes unknown. The doctor who performed the autopsy found the boy’s digestive tract virtually normal in appearance, and concluded:

The autopsy is far from confirming that he vomited a foetus; but neither does it prove that the story was made up, because of the time that had elapsed between the appearance of the foetus and the examination of the digestive organs.

There was, however, one intriguing anomaly: A small area of the stomach lining was unusually well supplied with blood vessels. A committee of medical experts in Athens agreed that this might have been the point at which the fetus was attached by its placenta. Saint-Hilaire’s report took account of all these findings, concluding that although the case was far from proven, he could not rule it out entirely. He noted that if it was a hoax, the “simple and ignorant” parents of young Demetrius certainly had nothing to do with it.

As Saint-Hilaire knew, it is sometimes possible for one fetus to develop inside another, a phenomenon known as fetus in fetu (FIF). Demetrius may have shared his mother’s womb with another fetus—his twin—which was subsequently absorbed into his own body. This is an incredibly rare occurrence, with fewer than two hundred cases recorded in the medical literature. In one extreme example, reported in 2017, a fifteen-year-old Malaysian boy was admitted to the hospital with abdominal swelling and severe pain; surgeons found a malformed fetus weighing 1.6 kilograms inside his body. What makes Demetrius’s case unusual is the location of his “twin”: Although FIF cases have been found inside the abdomen, skull, scrotum and even the mouth, it is difficult to believe that such an object could remain intact in the highly acidic environment of the human stomach for more than a few days.

THE CASE OF THE LUMINOUS PATIENTS

The Irish medic Sir Henry Marsh began his career hoping to become a surgeon, but at the age of twenty-eight he cut his forefinger while dissecting a cadaver and it became necessary to amputate the digit to prevent gangrene. His surgical ambitions thwarted, he instead became a physician, a profession in which he achieved great eminence. In 1821, he helped to found a children’s hospital in Dublin—the first such institution in Great Britain and Ireland—and was later appointed a physician to Queen Victoria.

In an age when doctors were often imperious and forbidding, Marsh was known for his kindly and cheerful bedside manner. He was also renowned for the quality of his medical research on conditions including diabetes, fevers and jaundice. In June 1842, the Provincial Medical Journal devoted no less than ten pages to one of his essays. But what subject could be so important that a leading publication would make it the main feature of that week’s issue? Sir Henry explains:

Having obtained from an unquestionable and authentic source an account of a phenomenon of a very curious and interesting nature, not hitherto recorded or brought into public notice, I am induced to bring forward some facts I have been able to collect, illustrative of the spontaneous evolution of light from the living human subject.

That’s right: Sir Henry’s chosen subject is people who glow in the dark. It was his sincere belief that it is possible for the human body to produce its own light. Before unveiling his evidence for this startling assertion, however, he first points out that the phenomenon—known as bioluminescence—is quite common in marine organisms including plankton and deep-sea fish as well as a few insects such as fireflies.

Sir Henry reports a story told to him by a colleague who had attended the bedside of a young woman, identified only as L.A., who was dying from tuberculosis:

“It was ten days previous to L.A.’s death that I first observed a very extraordinary light, which seemed darting about the face, and illuminating all around her head, flashing very much like an Aurora Borealis.”

An indoor northern lights is not quite what a doctor expects to see when tending a patient on their deathbed.

“After she settled for the night I lay down beside her, and it was then this luminous appearance suddenly commenced. Her maid was sitting up beside the bed, and I whispered to her to shade the light, as it would awaken Louisa. She told me the light was perfectly shaded. I then said, ‘What can this light be which is flashing on Miss Louisa’s face?’ The maid looked very mysterious, and informed me she had seen that light before, and it was from no candle.”

A line that would not be out of place in a ghost story by M. R. James.

“I then inquired when she had perceived it; she said that morning, and it had dazzled her eyes, but she had said nothing about it, as ladies always considered servants superstitious. However, after watching it myself half an hour, I got up and saw that the candle was in a position from which this peculiar light could not have come, nor, indeed, was it like that sort of light; it was more silvery, like the reflection of moonlight on water.”

Sir Henry did not witness the phenomenon himself but had it on good authority that one of his own patients was also affected. A few months earlier, he explains, he had been treating another young woman in the final stages of tuberculosis. Shortly after her death, he had received this intriguing communication from the girl’s sister:

“About an hour and a half before my dear sister’s death, we were struck by a luminous appearance proceeding from her head in a diagonal direction. The light was pale as the moon; but quite evident to mamma, myself, and sister, who were watching over her at the time. One of us at first thought it was lightning, till shortly after we fancied we perceived a sort of tremulous glimmer playing round the head of the bed; and then recollecting we had read something of a similar nature having been observed previous to dissolution, we had candles brought into the room, fearing our dear sister would perceive it, and that it might disturb the tranquillity of her last moments.”

Sir Henry cites several other anecdotes of a similar nature, observing that in rural Ireland such occurrences were generally attributed to supernatural causes. As a man of science, he dismisses this as mere superstition, suggesting instead that as death approaches, some unidentified organic process may create phosphorescence around the human body. By way of illustration, he gives a final “luminous patient” story—this one supplied by Dr. William Stokes, an illustrious Dublin physician and one of the greatest heart specialists of the nineteenth century:

“When I was residing in the Old Meath Hospital, a poor woman labouring under an enormous cancer of the breast was admitted. The breast was much enlarged, and presented a vast ulcer with irregular and everted edges, from all parts of which a quantity of luminous fluid was constantly poured out.”

Skeptical? For reasons that will be explained in due course, I believe Dr. Stokes may have been telling the truth.

“Upon being asked whether she suffered much pain, she answered, ‘Not now, Sir, but I cannot sleep watching this sore which is on fire every night.’ I directed that she should send for me whenever she perceived the luminous appearance, and on that night I was summoned between ten and eleven o’clock. The lights in the ward having been then extinguished, she was sitting leaning forward, the left hand supporting the tumour, while with the right she every now and then lifted up the covering of the ulcer to gaze on this, to her, supernatural appearance. The whole of the base and edges of the cavity phosphoresced in the strongest manner.

Dr. Stokes walked to the end of the ward and found to his amazement that he could still see the luminous tumor from a distance of twenty feet.

“The light within a few inches of the ulcer was sufficient to enable me to distinguish the figures on a watch dial. I have no very distinct recollection of the colour of the light, but I remember that its intensity was variable, it being on some nights much stronger than on others.”

Sir Henry now attacks the most important question: What is the process responsible for this mysterious light? He speculates that when tissues begin to putrefy, they emit some luminous gas or fluid that is highly flammable. This would, he adds, explain the mystery of spontaneous human combustion: If the fluid were to ignite for some reason, perhaps the body itself could burst into flames. Sir Henry concluded that the luminescence observed in dying patients might have been caused by the presence of phosphorus, which burns spontaneously in the presence of oxygen. This theory is not tenable, because elemental phosphorus is far too reactive to be produced naturally by the human body. But there is one intriguing alternative.

In 1672, the natural philosopher Robert Boyle was thrilled to discover that a joint of veal hanging in his larder had started to glow in the dark. The luminous meat produced enough light to read by, of the same “fine greenish-blue as I have often observed in the tails of glow-worms.” Boyle’s joint had almost certainly been colonized by one of the many photobacteria, light-producing microorganisms found in seawater (and therefore in fish) all over the world. It has been known for years that poor food hygiene can result in cross-contamination if fish and meat are stored together; in a darkened room the surface of affected meat appears to be studded with points of light, like stars in the night sky. Most luminous bacteria are not human pathogens (agents of disease), but some are capable of colonizing the human body. If this is the case, it would offer one possible, albeit unlikely, explanation of the ghostly phenomena of Sir Henry’s patients who glowed in the dark.

THE MISSING PEN

You know those stories about old soldiers who suddenly develop mysterious back pain in their eighties, and discover that it’s caused by a bullet from their army days, long forgotten but still deeply embedded in tissue? They’re usually true. Foreign objects made from all sorts of surprising materials are often well tolerated by the body and can lie dormant for decades before causing any problems.

Even in that context, this tale published in The Medical Press and Circular in 1888 is something of an outlier—not least because it concerns a foreign body that remained in the brain for as long as twenty years before symptoms became apparent.

The infliction of fatal injury to the brain by the thrusting of pointed objects beneath or through the upper eyelid, through the orbital plate into the brain, has occurred a number of times. Baby-farmers have been known to procure the death of their charges by pushing needles in.

“Baby farmers” were those who looked after another person’s child for money. Since they were often paid in one (small) lump sum, many of them stood to profit if the child died. This led to many cases of infanticide: After a campaign led by The British Medical Journal in 1867, the law was reformed to introduce more rigorous regulation of fostering and adoption.

And not long since an irascible ‘fare’ thrust his stick some four inches into the brain of a cab driver in the same way.

I’ve sometimes been irritated by a cab driver, but I can’t think of circumstances in which this would be a proportionate response.

The effect of such an injury is generally very prompt, and within an hour or two—even if not at once—serious symptoms manifest themselves. A curious exception to this rule was the subject of an inquiry last week at the London Hospital, the victim being a commercial traveller 32 years of age. Until the last few weeks the deceased is stated to have been in good health, and to have kept a set of books most accurately.

The patient is identified in contemporary newspaper reports as Moses Raphael from Bromley-by-Bow in London’s East End. Because of his facility with numbers, this peripatetic young gentleman was described as a “wonderful brain worker”—a somewhat ironic description, as it turns out. Moses suddenly developed a splitting headache and complained of drowsiness. He was admitted to the hospital and, a few days later, died after developing symptoms of “apoplexy.” This word was generally used to describe a cerebrovascular accident or stroke, but his doctors were in for a shock:

On making a post-mortem examination of the brain, an abscess the size of a turkey’s egg was discovered at the base, evidently not of recent formation, inside which was a penholder and nib, measuring altogether some three inches in length. This foreign body must have been in its position for some considerable time, it being embedded in bone. No trace of injury to the corresponding eye or nostril could be detected.

His widow was amazed: She had never heard him allude to anything of the kind, and nobody could recall his having been injured at any stage of his life.

The pen and nib were of the ordinary school pattern, and there is nothing to show that the injury was not inflicted years ago when the deceased was at school. Altogether, it is a very remarkable case and demonstrates the extreme tolerance of the brain to a very serious injury, and to the presence of a foreign body under certain circumstances. It is fortunate, in one sense, that the deceased died in a hospital; in private practice his death would have been certified as due to apoplexy, or, in case of an inquest, to ‘visitation of God’.

“Visitation of God” was a verdict often returned in cases of sudden or unexplained death. In the case of this patient’s demise, it seems unnecessary to invoke a deity—even one wielding a pen.