3

3

DUBIOUS REMEDIES

ONE THING MOST people know about the history of medicine is that doctors used to prescribe some pretty strange courses of treatment. For millennia, they were famously reliant on bleeding—a therapy invented (at least according to the Renaissance scholar Polydore Vergil) by the hippopotamus:

Of the water horse in Nylus, men learned to let blood: for when he is weak and distempered, he seeketh by the riverside the sharpest reed-stalks, and striketh a vein in his leg against it, with great violence, and so easeth his body by such means; and when he hath done, he covereth the wound with the mud.

Some forms of bleeding were comparatively mild. Leeches, widely used across Europe for hundreds of years, removed only a teaspoonful of blood per application. More drastic was venesection, when the doctor opened a vein to evacuate larger volumes. The technique was most often used on an arm, although it could be applied all over the body. In a treatise published in 1718, the German surgeon Lorenz Heister gives instructions for taking blood from the eyes, the tongue and even the penis. One particularly enthusiastic exponent of bloodletting, the eighteenth-century American Benjamin Rush, encouraged his pupils “to bleed not only by ounces or in basins, but by pounds and by pailfuls.” The practice finally died out in the nineteenth century, although a few older practitioners were still espousing it as late as the 1890s.

If you were lucky enough to escape a thorough bleeding, taking medicine often wasn’t much fun either. Commonly prescribed drugs throughout this period included highly toxic compounds of mercury and arsenic, while naturally occurring poisons such as hemlock and deadly nightshade were also staples of the medicine cabinet. The Pharmacopoeia Londinensis, a catalogue of remedies first published in 1618, offers a fascinating insight into what used to be considered “medicinal” in seventeenth-century England. It includes eleven types of excrement, five of urine, fourteen of blood, as well as the saliva, sweat and fat of sundry animals. Other items you could routinely find in an apothecary’s shop of the time included the penises of stags and bulls, frogs’ lungs, castrated cats, ants and millipedes.

Perhaps the most bizarre items were discarded nail clippings (used to provoke vomiting), the skulls of those who had died a violent death (a treatment for epilepsy) and powdered mummy. The latter was prescribed for a variety of conditions including asthma, tuberculosis and bruising, and the premium stuff was imported from Egypt—although a cheap imitation could be prepared at home by dipping a joint of meat in alcohol and smoking it like a ham. Every bit as effective as the real thing, and a decidedly superior sandwich filling.

None of these odd remedies survived much beyond 1800, unsurprisingly, although all were perfectly orthodox in their day. As old medicines fell out of favor and new ones took their place, doctors frequently reported their experience with the new drugs in the professional journals. While some were deemed effective and gained general acceptance, others fell by the wayside. It is often the accounts of these failed remedies that make for the most entertaining reading—treatments that not only seem ridiculous today but were ridiculous from the moment they were conceived.

DEATH OF AN EARL

On a warm August afternoon, a man in his fifties is enjoying a game of bowls in the affluent English town of Tunbridge Wells. Suddenly he passes out and falls to the ground, apparently dead. If this scene were unfolding today, an ambulance would probably arrive in a few minutes, and paramedics would attempt resuscitation before whisking the poor man off to a hospital for urgent treatment. But what might have happened three hundred years ago? Thanks to an extraordinary document from the Bodleian Library in Oxford, reproduced in the Provincial Medical and Surgical Journal in 1846, we have a pretty good idea.

In 1702, the doctor Charles Goodall was staying with friends in Tunbridge Wells when his professional services were unexpectedly requested. Dr. Goodall, a celebrated medic who a few years later would be elected president of the Royal College of Physicians, described the tragic events in a letter to an eminent colleague, Sir Thomas Millington:

The most considerable accident which happened this season was the most sudden and surprising death of that great and eminent peer, the Earl of Kent, the true and full history of whose case is the following.

The deceased was Anthony Grey, the 11th Earl of Kent, then aged fifty-seven.

His Lordship came very well to Tunbridge Wells, and continued so for about twelve days. He used no manner of exercise while he stayed, but only walking after morning prayers, for one hour or two, and sometimes after evening prayers, or on the bowling green at Mount Sion. On his Lordship’s last and fatal day, I walked with him from the chapel two or three turns on the walks; he then made an appointment to meet at five in the evening to play at bowls, which he had not done before, nor drunk the waters during his continuance with us.

In the early eighteenth century, most people who stayed at Tunbridge Wells were there to take the famous mineral waters. They were discovered—according to tradition—in 1606 by Dudley, Lord North, a dissipated young nobleman who recovered from a “lingering consumptive disorder” after drinking from a spring he had stumbled across in the woods. Dr. Goodall was himself at the spa for therapeutic reasons: His daily regime involved taking the waters and playing bowls for two hours every evening.

I went at the time appointed, and found my Lord on the green before I got thither, engaged in bowls (if I mistake not), with the Lord George Howard, Lord Kingsale, and Sir Thomas Powis.

A suitably aristocratic foursome.

I gave him an account of some news of which he had not heard, which occasioned some discourse betwixt us; then he went to his bowls, and played (I suppose) two or three games. I went to the other end of the bowling green, and played one game and part of a second, when on the sudden there was a cry, “A Lord is fallen! A Lord is fallen! A surgeon! A surgeon!” upon which I left my bowls, and ran up to his Lordship, and found him dead on the ground, he having neither pulse nor breath, but only one or two small rattlings in the throat, his eyes being closed.

“Neither pulse nor breath” seems pretty final: respiratory and cardiac arrest. Today any competent first-aider would administer CPR, but this is a surprisingly modern technique, first described as late as 1958. I at first assumed that an eighteenth-century medic would realize the case was hopeless, but Dr. Goodall was not so easily defeated.

He was bled immediately on both arms to the quantity of ten or twelve ounces, as computed.

Slightly more than half a pint.

In the meantime I put up the strongest snuff and Spiritus Salis Armoniaci into both nostrils, and ordered two ounces of Vinum Benedictum to be brought with all speed. The apothecary (Mr Thornton) sent for three ounces, which he poured down his throat, not spilling one drop.

“Spiritus salis armoniaci” (sal ammoniac) is a solution of ammonium chloride, an expectorant often used to treat chest complaints. The highest-quality sal ammoniac came from Egypt and was manufactured from camels’ urine. “Vinum benedictum” is antimonial wine, wine adulterated with the toxic metal antimony and used as an emetic. The doctor’s plan, quite orthodox for the time, was to shock the earl back to life by provoking an extreme reaction: sneezing, coughing or vomiting.

As soon as this was done we carried my Lord (in a chair) off the bowling green through the dancing-room into a very sorry bedchamber, one pair of stairs. I supported his Lordship’s head (which otherwise would have fallen on one side, or backwards, or forwards) with my hands and breast, till he was placed on a bed in a little room; when this was done, I cried out for a surgeon to apply six or eight cupping glasses to his Lordship’s shoulders with deep scarification; but no surgeon or apothecary (although one of the former and one of the latter were present) had any, neither was there any to be had on the walks, (as was answered by the surgeon or apothecary present), nor could have been procured if the Queen’s life had lain at stake on Tunbridge Wells.

Scarification with cupping was a mild form of bloodletting: Small incisions were made in the skin, and the cupping glasses drew out a modest volume of blood by suction.

When I found myself thus unhappily disappointed, I ordered his head to be shaved, and a large blister to be applied to capiti raso,* as also another to the breadth of neck and shoulders.

A blister was just what it sounds like: A harsh inflammatory substance was applied to the skin, usually on a plaster, in an attempt to provoke blistering and force toxins out of the body. The doctor also administered several spoonfuls of buckthorn syrup, a laxative. He was then joined by a colleague, one Dr. Branthwait, who had heard the news and hurried to offer his assistance. He suggested giving the dying man a “proper julep” (a refreshing infusion of herbs). The two medics certainly intended to be thorough. But the treatment was about to get rather more extreme:

Then Dr West came, who advised a frying pan made red hot to be applied to the head . . .

This sounds like desperation, and probably was.

. . . however there appeared not the least breath, pulse, or life in my Lord (though one or two physicians thought that there was some little umbrage* thereof), so that in short we had very slender hopes of his Lordship’s case, or little or no encouragement from any application used.

At this point, Dr. Goodall became frustrated that the room was “crowded with lords and gentlemen,” and asked them all to leave. One, the Bishop of Gloucester, went to break the news to the earl’s daughter, who lived a mile away.

She was (as must be imagined) upon the hearing of this news in a very great passion, crying out, “Is my Lord dead? is my Lord dead? tell me, my Lord, plain truth”; which being owned by the Bishop that his Lordship was dead, and of an apoplexy, she asked him whether cupping-glasses had been applied, and resolved to go to her dear father.

Distraught, the young woman asked for her father’s body to be brought back to his own apartment. Dr. Goodall agreed,

it being my judgment that the motion of the coach, with the warmth of my Lord’s servant, who kept his body in an upright erect position by grasping him round the waist, might conduce to the operation of the vomit and purge which had been given him some hours before, if there was the least warmth or life left in his stomach or bowels, which might be so, though indiscernible to us.

This was surely a forlorn hope: It sounds as if the poor man had died within minutes of his original collapse. Nevertheless, the earl’s corpse (presumably) was propped up in a coach and taken to his own lodgings. Even now the treatments continued:

As soon as his Lordship was put into his warm bed we ordered several pipes of tobacco thoroughly lighted to be blown up the anus, which we thought might be of use, when we could not have the advantage of tobacco glysters.

A “glyster” is an enema. A liquid preparation of tobacco, which was known to be a stimulant, was routinely injected through the anus to treat a variety of conditions. On this occasion, however, they did not have any enema paraphernalia to hand, so instead resorted to blowing smoke up the dead man’s bottom. Though this may sound an eccentric thing to do, it was a standard resuscitation technique, often employed in cases of drowning.* When even this failed to work, the doctors were at their wits’ end. They tried one last desperate method, an attempt to warm the patient up:

After this was done, upon a suggestion of Sir Edmund King’s, the bowels of a sheep killed in the house were applied to his Lordship’s stomach and belly, but all without the least success, though we were reasonably encouraged to make use of all proper remedies in so great a case, many apoplecticks having come to life a considerable time after they appeared dead to all human sense.

An “apoplectick” is one who suffers apoplexy—what we would call a stroke or cerebrovascular accident (CVA). Stroke patients do indeed sometimes lapse into a coma and later recover, and three hundred years ago, medics often had great difficulty telling the difference between coma and death. Without a stethoscope, it was impossible to be absolutely sure that the heart had stopped beating; in some cases, it was safe to declare that death had occurred only once rigor mortis had set in. In that context, Dr. Goodall’s perseverance in his resuscitation efforts is quite understandable.

The letter concludes with a lengthy discussion of the possible cause of death. Dr. Goodall’s colleagues believed that the earl had died from an abscess or a “syncope”—the latter meaningless as a diagnosis, since it means simply “loss of consciousness.” An abscess is also unlikely, since one could be expected to produce signs of infection before the patient’s final collapse. There are in fact numerous things that might cause sudden death: a heart attack, cardiac arrhythmia or a burst aneurysm, for instance. But Dr. Goodall was strongly of the opinion that the fatal event had been a stroke, pointing out that when these are very severe

the patient is (as it was) planet-struck, or knocked down by a club, or butcher’s axe, never more to move hand or foot after.

Just such a blow, he argued, felled the unfortunate Earl of Kent.

THE TOBACCO-SMOKE ENEMA

Samuel Auguste André David Tissot was an eminent Swiss physician of the eighteenth century, the author of one of the first scholarly studies of migraine, and also remembered for his much-cited work on the evils of masturbation, L’Onanisme. In 1761, he published Avis au Peuple sur sa Santé, a little book aimed at the general public and translated into English six years later.

One of the early readers of this work was John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, who was fascinated by medicine and even had a small practice as an amateur physician, giving free care to those who could not afford a proper doctor. In 1769, he published his own version of Tissot’s work under the title Advices with Respect to Health. Although much of its guidance remains valid today, other sections are, well, a little outdated. Take, for instance, Tissot’s advice on first aid in the event of near-drownings, which begins sensibly enough:

Whenever a person who has been drowned has remained a quarter of an hour underwater, there can be no considerable hopes of his recovery: the space of two or three minutes in such a situation being often sufficient to kill a man. Nevertheless, as several circumstances may happen to have continued life beyond the ordinary term, we should not give them up too soon, since it has often been known that after the expiration of two, and sometimes even of three hours, such bodies have recovered.

This sounds extremely unlikely. Seven minutes underwater is usually enough to cause fatal brain damage, and after half an hour, the chances of survival are virtually nil. Extremely cold water can increase this theoretical maximum, since hypothermia reduces the body’s oxygen requirements and also triggers physiological mechanisms that effectively slow the metabolism. Even so, there are only a handful of cases in which people are known to have survived as long as an hour underwater, let alone two or three.

Tissot lists several measures that should be taken in order to improve the chances of recovery.

Immediately strip the sufferer; rub him strongly with dry coarse linen; put him as soon as possible into a well heated bed, and continue to rub him a considerable time together.

Before the advent of CPR, rubbing the body was thought to be the best way of restoring the circulation, even if the heart had stopped. Artificial respiration, on the other hand, was already known in the eighteenth century:

A strong and healthy person should force his own warm breath into the patient’s lungs; and the smoke of tobacco, if some was at hand, by means of a pipe, introduced into the mouth.

Imagine a paramedic giving mouth-to-mouth resuscitation while smoking a cigarette, and you’ll get the general idea. Tissot, like many eighteenth-century doctors, believed that the primary cause of drowning was not necessarily inhaled water but the froth it created with gas inside the lungs. The theory behind this intervention was that tobacco smoke would dissolve this froth, causing the air to recover its “spring” or pressure—a technical term borrowed from the experimental writings of Robert Boyle. Bleeding was, naturally, another vital component of emergency treatment.

If a surgeon is at hand, he must open the jugular vein, and let out ten or twelve ounces of blood. Such a bleeding renews the circulation, and removes the obstruction of the head and lungs.

And why stop at blowing tobacco smoke into the patient’s lungs? Two orifices are better than one.

The fumes of tobacco should be thrown up, as speedily and plentifully as possible, into the intestines by the fundament. Two pipes may be well lighted and applied; the extremity of one is to be introduced into the fundament; and the other may be blown through into the lungs.

Tissot even recommends using a pipe attached to a bladder for this purpose, much like the bag-mask ventilators used today by paramedics. Blowing tobacco smoke up the rectum was not some eccentric idea of his own: As we’ve already seen, the technique was employed in the failed attempt to revive the unfortunate Earl of Kent, and it was widely used in eighteenth-century Europe. It was known as Dutch fumigation, but the practice is believed to have been the invention of Native American tribes centuries earlier.

Tissot’s book was published just before the emergence of the humane societies, organizations dedicated to the study and practice of resuscitation. The first of these, the Society for the Recovery of Drowned Persons, was founded in Amsterdam in 1767; others soon followed in Germany, Italy, Austria, France and London. Dutch fumigation was believed to be so valuable a technique that tubes and bellows for blowing tobacco smoke “into the fundament” were installed in public places such as coffee shops and barbershops—just as defibrillators are today. But it was not just smoke that might be used:

Any other vapour may also be conveyed up, by introducing a cannula, or any other pipe, with a bladder firmly fixed to it. This bladder is fastened at its other end to a large tin funnel, under which tobacco is to be lighted. This contrivance has succeeded with me upon other occasions, in which necessity compelled me to apply it. The strongest volatiles should be applied to the patient’s nostrils. The powder of some strong dry herb should be blown up his nose, such as marjoram, or very well dried tobacco.

It’s a wonder the patient had any space left in his airways for oxygen, with all these substances being inserted into them.

As long as the patient shows no signs of life, he will be unable to swallow. But as soon as he discovers any motion, he should take within one hour, a strong infusion of carduus benedictus, of camomile flowers sweetened with honey; and supposing nothing else to be had, some warm water, with the addition of a little salt.

Carduus benedictus, also known as Holy Thistle, was believed to be a panacea by early modern medics: In Much Ado about Nothing, Margaret says to Beatrice: “Get you some of this distilled carduus benedictus and lay it to your heart; it is the only thing for a qualm.”

Notwithstanding the sick discover tokens of life, we should not cease to continue our assistance since they sometimes expire after these first appearances of recovering. Lastly, though they should be manifestly reanimated, there sometimes remains an oppression, a coughing and feverishness; and then it becomes necessary sometimes to bleed them in the arms, and to give them barley-water plentifully.

The barley water doesn’t sound too bad an idea, at least. Some of his suggestions are fairly dreadful, but Tissot concludes by condemning certain other treatments that are even worse:

These unhappy people are sometimes wrapped up in a sheep’s, or calf’s, or a dog’s skin immediately flayed from the animal: but their operations are more slow, and less efficacious, than the heat of a well-warmed bed.

Yeuch. This was, in fact, a measure often resorted to—though more usually on the battlefield, where warm blankets were sometimes hard to come by.

The method of rolling them in an empty hogshead is dangerous and misspends a deal of important time. That also of hanging them up by the feet ought to be wholly discontinued.

Probably for the best. In fact, these were venerable and widespread practices. The “hogshead” method entailed securing the patient on top of (or within) a barrel placed on its side, which was then rolled back and forth. This gentle oscillation was supposed to evacuate water from the lungs, as was the cruder expedient of suspending the patient upside down. But these techniques were already beginning to go out of fashion: fifteen years later the influential Edinburgh physician William Cullen denounced them, asserting that they were “extremely dangerous, and often destroy the small remains of life.”

Tissot concludes with another helpful tip:

The heat of a dung-heap may also be beneficial: and I have been informed by a sensible spectator of it, that it effectually contributed to restore life to a man, who had remained six hours under water.

I humbly submit that the “sensible spectator” was talking through his fundament.

SALIVA AND CROW’S VOMIT

The University of Pavia in northern Italy is one of the oldest in the world, founded in 1361. It has a distinguished history of experimental scientific research: Alessandro Volta, the pioneer of electrochemistry, was professor there for forty years beginning in 1779.

While Volta was working on his voltaic pile—the first electric battery—his colleagues in the medical faculty were also producing world-leading research. Alas, some of it has not aged well. An article in the Annals of Medicine for the Year 1797 reports a lecture given by Dr. Valeriano Brera, a brilliant young physician who had been appointed professor at the tender age of twenty-two. In later years, Brera published a number of important works, including a book about parasitic worms that correctly challenged the theory, prevalent at the time, that such organisms were generated spontaneously inside the human body. But this earlier paper, reporting a clinical trial of a novel treatment that he had conducted in the city’s hospital, is not quite in that class of scholarship:

This new method of exhibiting remedies, first proposed by Dr Chiarenti of Florence, and afterwards extended by Dr Brera of Pavia, has excited too much attention in Italy and in France, to permit us to leave it unnoticed, however little we may be disposed to coincide with its supporters in their opinion of its vast utility, and expectations of the benefits to be derived from it.

Not exactly a ringing editorial endorsement.

Dr Chiarenti recommended the gastric juice as an excellent remedy in diseases originating from debility of the stomach.

Making a patient ingest the stomach acid of another person (or animal, as it turns out) is certainly a brave clinical decision. The originator of the idea, Francesco Chiarenti, was a resourceful medical researcher who had published a book on the composition and function of stomach fluids.

In giving opium at the same time, he found that it often occasioned much uneasiness and vomiting. This he ascribed to its remaining on the stomach undigested, from the vitiated* gastric fluid not acting on it; and led him to reflect on the reasons why opium, administered externally, had so little action.

A question of huge interest to doctors of the late eighteenth century, particularly Italian ones. The anatomist Paolo Mascagni, who in 1787 published the first comprehensive description of the lymphatic system, had suggested that the quickest way of getting medicines into the circulation was not by swallowing them but through the skin. His doctrine, known as the iatroliptic* method, used ointments and unguents in place of oral medicines. But physicians who tried his method noticed that some drugs that were effective when ingested had almost no effect when rubbed on the skin. It was not at all clear why opium, for instance, was a powerful analgesic when swallowed but not when used as an ointment. Dr. Chiarenti deduced that it was not absorbed in the stomach immediately but only after it had first been altered in some way by the gastric juices. If he could replicate this process outside the body, he reasoned, maybe it would be possible to make a preparation of opium that would pass through the barrier of the skin. He decided to test this theory by experiment.

An occasion soon offered. A woman, afflicted with violent pains, refusing to take opium by the mouth, was a fit subject for commencing his trials. He mixed three grains of pure opium with two scruples of the gastric juice of a crow.

Why a crow? This is not explained, but in his book, Dr. Chiarenti observes that crows are enthusiastic devourers of putrid meat, indicating that their gastric juices may be particularly powerful—if not necessarily the sort of thing you’d want to rub into your skin.

It soon emitted a strong and penetrating smell . . .

I bet it did.

. . . which diminished gradually. In half an hour, the opium was perfectly dissolved; but it was permitted to remain twenty-four hours. It was then mixed with simple ointment, and rubbed on the backs of the feet. In an hour, the pains were entirely gone; and, never returning, the woman remained cured.

This may have had nothing to do with the foul-smelling morphine/crow’s vomit concoction, of course—faced with the prospect of a second dose, I would probably pronounce myself miraculously cured, too.

By the difficulty of procuring a sufficient quantity of the gastric fluid to enable him to carry his experiments the length he wished, he was led, by analogy, to substitute in its place saliva; and the result answered his expectations.

And why not? You may as well smear crow spit on your patients as crow vomit. Five other physicians tested the technique, using it to administer a variety of drugs, and claimed similar results. Professor Brera believed he had found what he was looking for: a way of turning an oral medicine into a topical ointment.

From all these observations, he is led to conclude, that every animalised fluid is fitted by nature to render remedies capable of being absorbed.

A number of Italian practitioners adopted Dr. Brera’s methods with enthusiasm, and one or two eminent French physicians continued his research for a decade or so. But for some inexplicable reason, the crow’s saliva ointment treatment never really caught on.

THE PIGEON’S-RUMP CURE

Eclampsia is a serious condition affecting women before, during or after childbirth. The name means literally “shining forth,” a metaphor (or perhaps euphemism) for the seizures that characterize the condition, which arrive suddenly and dramatically. The cause of eclampsia has never been identified, although it is always preceded by pre-eclampsia—a combination of symptoms including high blood pressure and protein in the urine.

Until the late nineteenth century, doctors also recognized a malady they called the eclampsia of children. This was a misnomer: Although infants can suffer seizures that look like those observed in pregnant women, the likely causes of the two are quite different. For instance, infants affected by fever often display febrile convulsions, which look serious but do not necessarily indicate any sinister underlying condition.

In a textbook published in 1841, the Handbuch der medizinischen Klinik (Handbook of the Medical Clinic), the German physician Carl Friedrich Canstatt offered a really rather odd approach to treating children with “eclampsia”:

One remedy I must mention here whose unequivocal effects I have myself witnessed, however inexplicable the phenomenon. If one holds the rump of a dove against the child’s anus during paroxysm, the animal quickly dies and the attack ceases just as rapidly.

One wonders what strange sequence of events led to this discovery. Ten years later, the Journal für Kinderkrankheiten (Journal for Childhood Diseases) picked up on this odd little aside. It reported that several physicians had been prompted to try the remedy for themselves. One of them was a Dr. Blik from Schwanebeck:

A nine-month-old child, full-bodied, healthy and alert, with no signs of teething, was attacked by eclampsia, which recurred in ever-increasing seizures, and calomel,* valerian,* musk,* baths, mustard,* and enemas were used in vain. When yet another convulsion occurred, the anus of a young dove was held against the child’s until the seizure was over. The attack was fierce, but the child survived.

Not long afterward, the journal received a communication from a reader in St. Petersburg. Dr. J. F. Weisse was the German-born director of the children’s hospital in the Russian city:

Dr. Weisse had read the earlier article with interest. He was, he explained, already familiar with what later became known mockingly (in the English-language literature) as the “pigeon’s-rump cure”:

Long before the publication of Canstatt’s Handbook I had already read—I do not remember where—about this strange method; but his approval induced me to apply it myself at an appropriate opportunity.

Dr. Weisse had, it transpires, used the magical pigeon’s bottom on two separate occasions.

On August 13, 1850, during the night, I was called to a four-month-old child, who was suddenly attacked by eclampsia. After two days of unsuccessfully treating him by the usual means, and meanwhile believing this was a suitable opportunity for the experiment, on the third day I told the mother, a Russian lady of property, about this magical agent; I added, however, that I myself had little faith in it, but believed it to be completely harmless.

Not having any faith in a treatment is not a terribly good starting point for using it, but I suppose if all else had failed, you can understand his position.

I had not been mistaken in my assumption, for the suggestion was met with approval, and they immediately proceeded to procure a pair of pigeons for the emergency. Early on the following morning, when I visited the little patient again and had almost forgotten the birds, I was received by the lady’s fourteen-year-old son who opened the door, speaking to me in broken German: “The dove is dead and the child is very healthy; come on, Mama will tell you about it.”

Certainly an arresting opening to a conversation.

The woman approached me with a joyful face, solemnly shook my hand and led me to her child, who was sleeping soundly. I learned that the previous day after my visit there had been several convulsions in quick succession, but at seven o’clock in the evening such a violent fit had occurred that, despairing of the boy’s life, they had resorted to the pigeon. The woman’s sister, who carried out the operation according to my instructions, told me that shortly after the bird had been applied to the child’s anus it had gasped for air several times, closed its eyes periodically, then its feet had twitched in spasm and finally it had vomited. At the same time the child’s seizures became weaker, until at the end of half an hour it sank into a peaceful sleep, which lasted for five hours. The pigeon, however, afterwards could not stand on its feet, nor did it touch the food that had been offered, and finally expired about midnight.

Net result: one healthy child, but one dead pigeon. You win some, you lose some. Dr. Weisse was encouraged by this experience but frustrated that he had not been on hand to witness the miraculous cure for himself. On the next occasion, he was more fortunate:

This case concerned a boy of one year and eight months who for a long time had been suffering from dyspeptic disorders related to dental work and had been under my medical supervision for several weeks. On the evening of the 8th of October 1850 I received a letter asking me to hurry as soon as possible to the child, which had suddenly suffered a seizure.

When he arrived at the child’s bedside, he found the boy unconscious, with trismus (a locked jaw) and half-closed eyes. Every so often, the child’s face and extremities were gripped by spasms. The lockjaw made it impossible to give medicines by mouth, so the doctor suggested the pigeon cure:

A few minutes later a pair of pigeons was brought in and I was able to put the procedure into practice myself. About ten minutes after the application, I noticed that the pigeon I was holding opened its beak several times, as if gasping for breath. The child’s spasms were now becoming more infrequent and weaker, but his pulse was also sinking more and more. After half an hour I realised that the pigeon had closed its eyes and let its head hang down; it was dead. I now had the other animal brought to me and laid it in the same way on the anus of the child, whose pulse, however, could soon no longer be felt—and after only ten minutes it lay there as a corpse. The dove, however, remained alive.

Scant consolation to the devastated parents. Dr. Weisse concludes with a mystifying appeal to his peers to continue this unusual research:

Finally, I cannot but urge all colleagues to repeat such experiments with the remedy as much as possible, for it seems clear what a great benefit to the treatment of children, especially those of the lower classes, would emerge if it were proved to happen this way.

Noting that St. Petersburg is teeming with pigeons, he also acknowledges that in other parts of the world, they are not so abundant. But he’s got that covered, too:

In the meantime, experiments with other poultry are necessary.

You may think I’m being a bit hard on poor Dr. Weisse: After all, it’s not fair to judge the doctors of two hundred years ago by today’s standards. They had their reasons for choosing the remedies they used, however odd they may seem to the modern reader. But even many of his contemporaries thought Dr. Weisse’s ideas were downright silly. An anonymous writer in the British and Foreign Medico-Chirurgical Review could barely withhold his glee, quoting Horace: “risum teneatis?” (“Can you help but laugh?”) This is his pithy verdict on the treatment:

We mentally offered . . . the advice of an old French physician, who, on being asked his opinion of a new remedy that was highly praised for its extraordinary virtues in a certain disease, very gravely replied, “Dépêchez vous de vous en servir pendant qu’il guérit!”

The Frenchman’s bon mot translates, more or less, as: “Hurry up and give it to him, while he’s still getting better!”

MERCURY CIGARETTES

Nineteenth-century medical opinion on the subject of smoking was sharply divided. On the one hand, many prominent doctors condemned the practice as unhealthy, or even suggested that it caused cancers of the mouth; on the other, plenty of physicians believed that smoking eased coughs and other respiratory disorders by promoting the production of mucus. But for a brief period, some members of the profession also saw the cigarette as the ideal drug-delivery mechanism: Medications could be easily mixed with tobacco and then inhaled with the smoke. A definite step forward from the days of blowing it up the patient’s bottom—although maybe not a very big step.

In 1851, the editor of the London Journal of Medicine gave his approval to an interesting new idea from the United States: cigarettes laced with mercury.

The inhalation of various medicines along with the smoke of cigars or cheroots has been more than once recommended in this journal. In prescribing the method, the physician must take care that the patient be clearly told that the smoke is to be drawn into the lungs; and the mode of doing this must be properly explained to him.

Quite—suck all the health-giving carcinogens into those lungs!

Mr J.H. Richards, of Philadelphia, writes as follows in the Medical Examiner for June 1851—“I have been informed by a gentleman of intelligence, who has resided for a long time in China and Manilla, that mercury, which is there regarded as a specific in the severe forms of hepatic* disorder incident to the climate (and leading to its employment to an extent that would be considered extravagant by Europeans), is constantly exhibited in the following novel and peculiar manner. The black oxide* is introduced into the Manilla cheroots, and, being inhaled, is thus presented in the form of vapour to the most absorbent surface in the body.

An absolutely horrendous notion. When heated, the “black oxide” decomposes to metallic mercury, tiny droplets of which would have coated the mouth, airways and lungs.

“It certainly is a speedy plan of producing salivation. I mention this fact, as it is interesting in itself, and may suggest other applications of the same principle.”

If you’re going to kill yourself by smoking, you might as well do it even more quickly by smoking mercury, I suppose.

Would this plan be admissible in pneumonia? Perhaps not.

Given that pneumonia is a potentially fatal infection involving the lungs, “perhaps not” does not begin to cover it.

It is right to state that the smoking of mercurialised cigars is by no means, as Mr Richards supposes, a novelty in the practice of medicine. The following formula was given many years ago by Bernard: “Cigarettes Mercurielles. Bichloride of mercury, 4 centigrammes; extract of opium, 2 centigrammes; tobacco deprived of its nicotine, 2 grammes.” These cigarettes are recommended in syphilitic ulcerations of the throat, mouth, and nose.

Mercury, opium and tobacco! But that’s just a glimpse of the possibilities. In 1863, the Canada Lancet gave a list of recipes for other “medicinal” cigarettes. In addition to the mercury cigarette, they recommended

Arsenical Cigarettes.

Yup, cigarettes containing arsenic, and made from blotting paper steeped in arsenous acid. The latter chemical is highly toxic and carcinogenic, and has been used to kill weeds, rats and mice. All things considered, smoking it is a Bad Idea.

Nitre Cigarettes. Dip the paper in a saturated solution of the nitrate of potash before rolling.

Nitrate of potash, also known as saltpeter, is potassium nitrate, a component of gunpowder. Smoke with all due caution.

Balsamic Cigarettes are made by giving the dried nitre cigarettes a coating of tincture of benzoin.

Tincture of benzoin is still sometimes inhaled in steam today, to ease the symptoms of bronchitis, but . . . ! The article concludes with a list of some of the miraculous cures attributed to medicated cigarettes:

Aphonia.—A patient who could not speak above a whisper for over a year, probably due to a thickened condition of the chordae vocales, as she had no pain or constitutional symptoms, used the mercurial cigarettes for a month, and perfectly recovered.

Offensive discharges from the nostrils, with a sense of uneasiness in the frontal sinuses, was quite cured in about a month with the mercurial cigarettes. The patient held his nose after taking a mouthful of the smoke, and then forced it into his nostrils in the manner practised by accomplished smokers.

Thus coating the delicate mucous membranes with fresh mercury vapor.

Phthisis.—Trousseau long ago recommended a puff or two of an arsenical cigarette twice or three times a day in phthisis.

Smoking while suffering from phthisis (tuberculosis) is perhaps the very worst thing you could do. Especially if arsenic’s involved.

When the attention of the profession has been duly aroused to this subject, there will doubtless be found many other affections in which medicated cigarettes may be advantageously employed.

No doubt. How about lung cancer?

THE TAPEWORM TRAP

In September 1856, an American journal, The Medical and Surgical Reporter, published a chatty “letter from New York.” Their correspondent was a physician at one of the city’s hospitals who called himself J. Gotham, Jr., MD. This was almost certainly a pseudonym: Although Gotham is best known as the fictional New York City of Batman and the Joker, the nickname first appeared in Washington Irving’s periodical Salmagundi in 1807. Today, Gotham has noirish overtones, but for the nineteenth-century reader, the associations of the name were essentially farcical. Irving named his satirical version of New York after an English village whose residents had a reputation for idiotic behavior—a perfect analogy, he felt, for the incompetence of the municipal bigwigs who ran the city.

Dr. Gotham’s dispatch from the cutting edge of New York medical science is certainly not short of absurdity:

As it is my desire to keep you advised of all the improvements in medical and surgical practice which this prolific age is ushering into being, it is my happy privilege now to bring to your notice one of the most ingenious, if not successful—the most far reaching, and deep searching, if not most likely to prove profitable, invention, ever accredited to Yankee wit and skill. It is one before which the lustre of the genius which produced the new operation for vaginal fistula must wax dim, and the discoverers of catheterism of the lungs must “pale their intellectual fires.”

The “new operation for vaginal fistula” was devised by James Marion Sims in the 1840s, a surgical cure for an uncomfortable and embarrassing condition that often left women incontinent after childbirth.* “Catheterism of the lungs” was pioneered by the Vermont-born specialist Horace Green. It was a contentious treatment for tuberculosis that involved injecting silver nitrate directly into the lungs, using a rubber catheter passed down the patient’s throat. Both these procedures were perceived as major advances, and emblematic of a new spirit of surgical adventure. As you’ve probably worked out, Dr. Gotham is drawing such comparisons ironically.

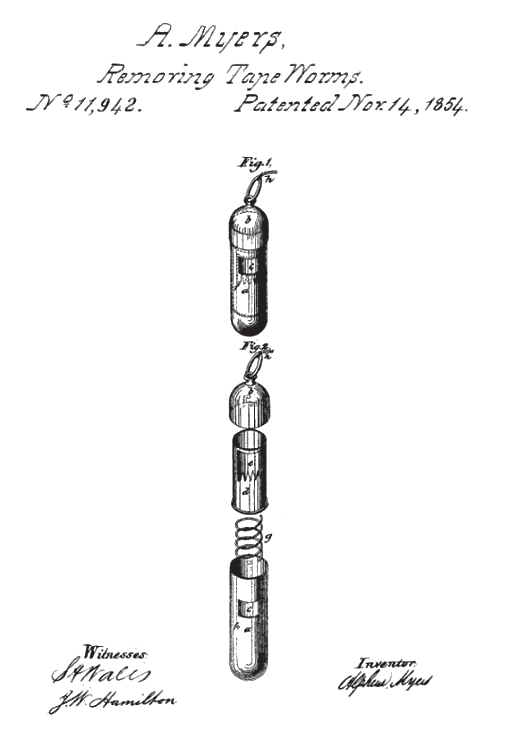

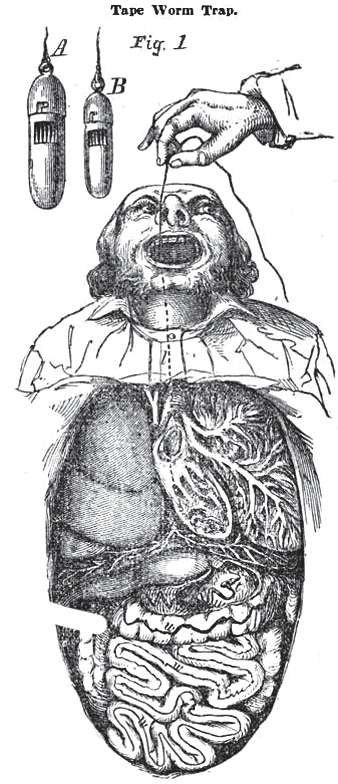

The government of the United States has immortalised its history by the issue of letters patent, securing to the inventor the exclusive right for fourteen years, of using a “Trap for Tapeworm”, a description and engraving of which are given in vol. 1 for 1854 of the Patent Office Reports.

The original patent for the tapeworm trap was filed by Alpheus Myers, a doctor from Logansport, Indiana. Dr. Myers was an exponent of Eclectic Medicine, a distinctly American school that rejected the chemical remedies and invasive procedures of conventional medicine. Instead of the poisonous laxatives and bloodletting favored by orthodox physicians, its adherents preferred plant remedies and gentle physical therapy. His invention was therefore an attempt to dispense with the toxic anthelmintic (anti-worm) agents then in use, such as powdered tin, calomel and even petroleum. Strangely, he patented not just the device but the operation for which it was designed—thus ensuring that he would be the only person in the country allowed to use it. This is not a particularly clever thing to do if your aim is to sell your invention to lots of other people.

Another article from The Medical and Surgical Reporter describes the use of this unusual contraption:

The tapeworm trap is a very small hollow tube of gold so arranged as to contain a small piece of cheese for a bait. The patient, after a fast of four or five days, is ordered to swallow the trap, with a string attached. It is claimed by the inventor that after a long-continued fast, the worm comes up into the stomach, and will then greedily seize the cheese, be caught in the trap, and can be easily pulled out.

This sounds most unlikely, not least because tapeworms live in the intestines and are averse to jaunts into the stomach, where the strongly acidic conditions would prove rapidly fatal. The inventor, Alpheus Myers, himself explains:

The cord is fastened to some conspicuous place about the patient, who is left to his ease from six to twelve hours, and during this time the worm will have seized the bait and have been caught by the head or neck. The capture of the worm will either be felt by the patient or ascertained by the motion which will be visible in the cord. The patient should rest for a few hours after the capture, and then by a gentle pulling at the cord the trap and worm will, with ease and perfect safety, be withdrawn.

The journal’s correspondent comments, with not a little sarcasm:

Imagine to yourself the satisfaction with which a man could thus sit down and fish in his own room, without even the accompanying tub of water; the patience and complacency with which, after waiting from six to twelve hours for a bite, he would then play his prisoner some hours more before landing him! Does not Mr Alpheus Myers have good reason to believe that the shade of Izaak Walton looks down upon him in anger for this innovation upon the piscatorial art?

Fishing for worms in one’s own stomach does sound like a rather unappetizing way of spending an afternoon. In its coverage of the development, Scientific American claimed that “Dr. Myers, not long since, removed one fifty feet in length from a patient, who, since then, has had a new lease of life.” A likely story.

Back to Dr. Gotham. His letter continues with a savage attack on the US patent office for even considering this nonsense:

My object in drawing the attention of your readers to it, is simply to expose the shameful ignorance, not of Alpheus Myers, but of the officers of our government, who would take money from a man for so gross an absurdity as this. There are physicians connected with the Patent Office, men whose names stand well before the country, and how they or the commissioner, could have allowed the seal of the office to be affixed to such a document for such a monstrously ridiculous contrivance, surpasses all comprehension.

He had a point. Not until 1965, when the husband-and-wife inventors George and Charlotte Blonsky succeeded in patenting their “Apparatus for facilitating the birth of a child by centrifugal force,”* would the US Patent Office rise to quite the same ludicrous heights.

THE PORT-WINE ENEMA

Alcoholic drinks were an important part of the physician’s armory until surprisingly recently. In the early years of the twentieth century, brandy (or whiskey, in the US) was still being administered to patients as a stimulant after they had undergone major surgery. Every tipple you can think of—from weak ale to strong spirits—has been prescribed at one time or another.

But doctors didn’t get their patients just to drink booze; indeed, they were remarkably imaginative in the strange things they did with it—injecting it into the abdominal cavity, for instance, or getting patients to inhale it. But this case, published in The British Medical Journal in 1858, trumps even those examples for sheer wrongheadedness.

No, you didn’t misread the headline: This article seriously suggests a port-wine enema as an alternative to a blood transfusion. The author is Dr. Llewellyn Williams from St. Leonards-on-Sea in Sussex:

On September 22nd 1856 I was called into the country, a distance of four miles, to attend Mrs C., aged 42, then about to be confined of her tenth child. All her previous accouchements had been favourable. When about six months advanced in pregnancy, she received a violent shock by the sudden death of her youngest child, since which time her general health had become much impaired. She had a peculiar pasty anaemic appearance, and complained much of general weakness.

Shortly after the doctor’s arrival, a “fine female child” was born without much difficulty. But then:

My patient exclaimed, “I am flooding away,” and fainted. I immediately had recourse to such restoratives as were at hand, and presently she began to revive.

The poor woman’s desperate shout was a literal description of her plight: She was bleeding heavily, at such a rate that she would soon be dead unless the hemorrhage could be arrested. Any improvement in her condition was short-lived, and Dr. Llewellyn Williams became seriously concerned.

My efforts still being foiled, and the haemorrhage continuing, the powers of life manifesting evident symptoms of flagging, I introduced my left hand into the uterus, after the manner recommended by Gooch,* endeavouring to compress the bleeding vessels with the knuckles of this hand, whilst with the other I pressed upon the uterine tumour from without. This combination of external and internal pressure was equally as unavailing as any of the other plans already tried. At last, by compressing the abdominal aorta, as recommended by Baudelocque the younger,* I was enabled effectually to restrain any further haemorrhage.

The abdominal aorta—the largest blood vessel in the lower half of the body—is only a few inches from the spinal column, so compressing it by hand is a procedure as difficult as it is drastic.

The condition of my patient had now become sufficiently alarming, she having been for upwards of half an hour quite pulseless at the wrist, the extremities cold, continual jactitation being present, the sphincters relaxed, and the whole surface bedewed with cold clammy perspiration.

Jactitation is pompous medic-speak for “tossing and turning.” It was probably archaic even in the 1850s.

It now became a question what remedy could be had recourse to, which should rescue the patient from this alarming state, it being utterly impossible to administer any stimulant by the mouth. My distance from home, together with considerable objections to the operation itself, which it is not here needful to dwell upon, made me abandon the idea of transfusion of blood.

The first successful human blood transfusion was conducted by James Blundell in 1818, also for postpartum hemorrhage. But it was hideously risky: Blood types were not discovered until 1901, so it was not possible to match donor to recipient, with often catastrophic results. But Dr. Llewellyn Williams had another idea. A really rather strange one.

As a means which I believe will prove equally as powerful as transfusion in arresting the vital spirit, I had recourse to enemata of port wine, believing that this remedy possesses a threefold advantage. The stimulating and life-sustaining effects of the wine are made manifest in the system generally; the application of cold to the rectum excites the reflex action of the nerves supplying the uterus; and the astringent property of port wine may act beneficially by causing the open extremities of the vessels themselves to contract.

Applying cold liquid to arrest bleeding was at least a rational thing to do: Crushed ice was often piled on top of the abdomen after childbirth if hemorrhage was difficult to arrest. But in other respects, the use of port in these circumstances has little to recommend it.

I commenced by administering about four ounces of port wine, together with twenty drops of tincture of opium. It was interesting to note the rapidity with which the stimulating effects of the wine became manifest on the system.

After a brief improvement, the woman’s pulse began to flag, so the doctor administered a second enema.

A more marked improvement was now manifest in the patient. She regained her consciousness; the pulse continued feebly perceptible at the wrist. In half an hour I had again recourse to the enema, with the most gratifying result; and, after ten hours’ most anxious watching, I had the happiness of leaving my patient out of danger.

Whether Dr. Llewellyn Williams was in any way responsible for her improvement remains a moot point.

The quantity of wine consumed was rather more than an ordinary bottle.

Not the most pleasurable way of consuming a bottle of port, by any means.

There’s a minor postscript to this unexpectedly happy ending: Six months after his article appeared in print, the British Medical Journal announced that Dr. Llewellyn Williams’s wife had given birth to a son. Whether she was given rectal doses of port, brandy or any other stimulating alcoholic beverage is not recorded. For her sake, let’s hope the good doctor left the delivery of his own child to one of his colleagues.

THE SNAKE-DUNG SALESMAN

In 1862, an Edinburgh-trained physician, Dr. John Hastings, published a slim volume about the treatment of tuberculosis and other diseases of the lung. It advocates the use of substances that much of the profession would regard as unorthodox, as he acknowledges in his preface:

It has been suggested that the peculiar character of these agents may possibly prove a bar to their employment for medicinal purposes.

Dr. Hastings then anticipates another likely objection—that the “medicine” he recommends is difficult to get hold of. Fear not: He can recommend some suppliers.

It may be useful to add that these new agents may chiefly be procured from the Zoological Gardens of London, Edinburgh, Leeds, Paris, and other large towns. They may also be obtained from the dealers in reptiles, two of whom—Jamrach and Rice*—reside in Ratcliffe-highway, whilst two or three others are to be found in Liverpool.

One might reasonably ask what sort of medicine can be purchased only at a zoo or pet shop. Dr. Hastings explains that he spent several years trying to find novel medicinal substances in nature, without success. Deciding that pharmacies were already “crowded with medicines derived from the vegetable and mineral world,” he resolved to investigate possible miracle cures in the animal kingdom.

It would be foreign to my purpose to detail here the various animals I put in requisition in the course of this investigation, or the animal products I examined during a prolonged inquiry. It is enough to state that I found in the excreta of reptiles agents of great medicinal value in numerous diseases where much help was needed.

Yes, Dr. Hastings’s miracle cure was reptile excrement. His book is entitled

Which reptiles, you may be asking?

My earliest trials were made with the excreta of the boa constrictor, which I employed in the first instance dissolved simply in water. A gallon of water will not dissolve two grains, and yet, strange as the statement may appear, half a teaspoonful of this solution rubbed over the chest of a consumptive patient will give instantaneous relief to his breathing.

Not just the boa constrictor either. Dr. Hastings provides a list of the species whose droppings he has investigated: nine types of snake (including African cobras, Australian vipers and Indian river snakes), five varieties of lizard and two tortoises. After his eureka moment, the intrepid physician was eager to introduce the new medicinal agents into clinical practice, and so he started to prescribe reptile excrement for his patients. Since his specialty was tuberculosis, most of the people who came to see Dr. Hastings would have been scared and desperate. In the 1860s, there was no cure for TB; although it was not universally fatal, around half of those who contracted the disease would die, most of them within two years.

Dr. Hastings includes a number of case reports. The first concerns “Mr. P.,” a twenty-eight-year-old musician who consulted him about a troublesome cough. Unexplained weight loss had eventually prompted the diagnosis of tuberculosis:

I prescribed the 200th part of a grain of the excreta of the monitor niloticus (warning lizard of the Nile) in a tablespoonful of water, to be taken three times a day, and directed an external application of the same solution to the diseased side. He was much better at the end of a week, and after a further week’s treatment I lost sight of him in consequence of his believing himself cured.

Another was “the Reverend Q.C.,” who sought treatment after he started to cough up blood, the classic presentation of tuberculosis. He was treated with two different types of lizard poo:

I applied to the walls of the left chest a lotion composed of the excreta of the boa constrictor of the strength of the ninety-sixth part of a grain to half an ounce of water. Under this treatment his amendment made rapid progress, until the month of May, when I prescribed for him a solution of the excreta of the monitor niloticus (warning lizard of the Nile) of the strength of the 200th part of a grain in two teaspoonfuls of water three times a day, and directed him to use the same mixture externally.

The clergyman’s symptoms improved dramatically, and a few weeks later, he was able to walk eight or ten miles “with ease.” But my favorite case is that of “Miss E.,” described as a “public vocalist,” which contains this magnificent paragraph:

This case is interesting, from the fact that I gave her the excreta of every serpent I have yet examined, and they all, without exception, after a few days’ use, occasioned headache or sickness, with diarrhoea to such an extent that I was obliged to relinquish their use. From the excreta of the lizards she experienced no inconvenience. She is now taking the excreta of the chameleo vulgaris (common chameleon) with great advantage, and is better than she has been at any one period during the last three years.

It’s all pretty ridiculous—a fact that the medical journals of the day did not fail to point out. A review in The British Medical Journal makes an excellent point about the nature of scientific evidence, suggesting that the “positive” results he recorded were nothing of the sort:

This doctor, unfortunately, gives his cases—his exempla to prove his thesis; and we must, indeed, announce them as such to be lamentable failures as supporters of his proposition. We verily believe, and we say it most conscientiously, that if Dr Hastings had rubbed in one-two-hundredth of a grain of cheese-parings, and had administered one-two-hundredth of a grain of chaff, and had treated his patients in other respects the same as he doubtless treated them, he would have obtained equally satisfactory results.

If The British Medical Journal was uncomplimentary, The Lancet was positively scathing. Its reviewer points out that twenty years earlier, Dr. John Hastings had published another book in which he claimed to be able to cure consumption—using naphtha.* And twelve years after that, he had decided that the cure for consumption was “oxalic* and fluoric* acids”; oh yes, and “the bisulphuret of carbon.”* Dr. Hastings had, in fact, discovered not one but five cures. The reviewer adds, with considerable sarcasm:

As regards that—to ordinary men—unmanageable malady, consumption, all our difficulties are now at an end. The public may fly to Dr Hastings this time with the fullest confidence that the great specific is in his grasp at last.

But he saves the best till last:

What can the public be thinking about, we would ask, when it supports and patronizes such absurd doings? Will there still continue to be found persons ready to allow their sick friends to be washed with a lotion of serpents’ dung?

Dr. Hastings was so offended by this article that he attempted to sue the publisher of The Lancet for libel. The matter was heard before the Lord Chief Justice, Sir Alexander Cockburn, who dismissed the case, ruling:

It might be that he had discovered a remedy, and, if so, truth would prevail in the end; but it was not to be wondered at that the matter was treated rather sarcastically when the public were told that phthisis could be cured by the dung of snakes.

Well said!