SOME ASPECTS OF SCIENCE AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH are, from a public opinion perspective, unassailable. These tend to be feel-good ideas—like, say, going to the moon—or abstractions that are simply impossible to argue with; who would try to claim that research into how cancer forms is a bad idea?

But universal appeal doesn’t mean that politicians are in lockstep support of those issues. It just means they have to be a bit more careful when they criticize them.

Here’s an example, once again turning to Texas senator and 2016 GOP presidential candidate Ted Cruz: during a Senate hearing regarding NASA’s funding in March 2015, he lavished praise on the space agency’s history, its employees, and its important position as a government entity.1 He said that “innovation . . . has been integral to the mission of NASA” and spoke about the “passion of the professionals at this fine institution.” He quoted a former astronaut, saying that “young Americans are interested in space-related STEM [science, technology, engineering, and math] careers, and see themselves as future space entrepreneurs.” He closed his brief statement by paraphrasing previous remarks about NASA: “It is time once again for man to leave the safety of the harbor and further explore the deep, uncharted waters of deep space.”

And then he tried to cut NASA’s funding for studying climate change.

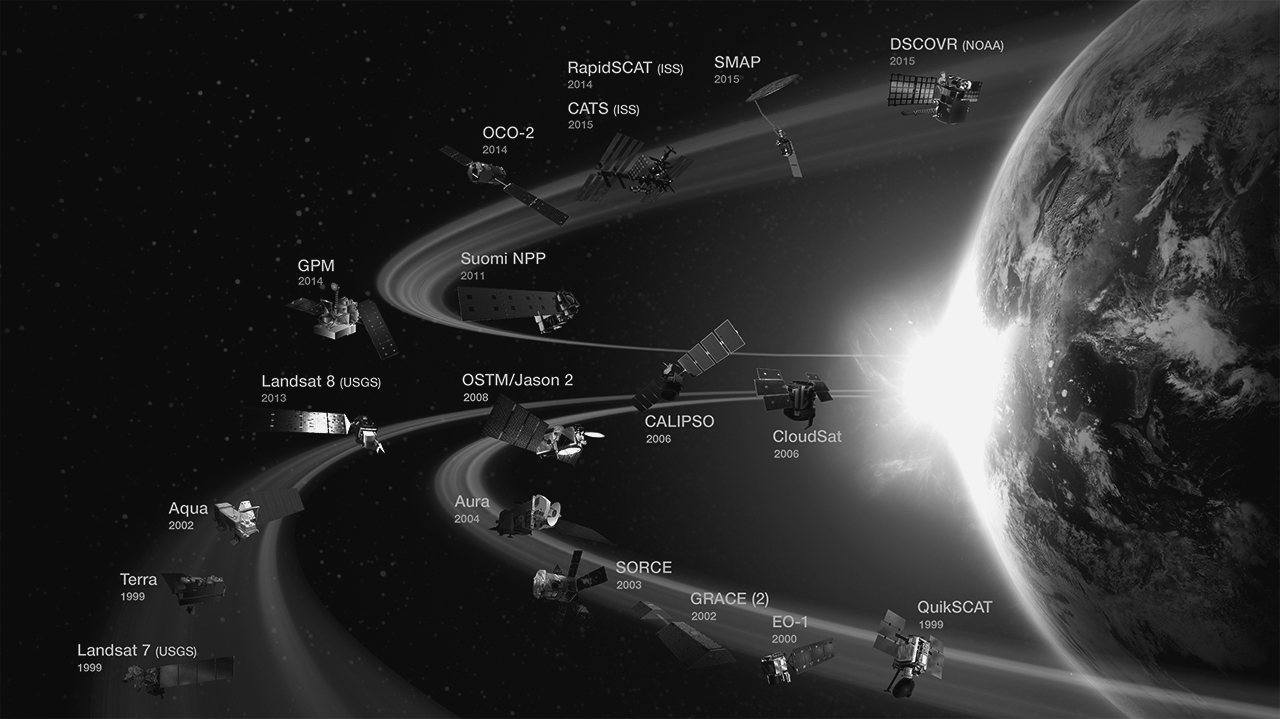

See, Cruz wasn’t there just to heap praise at NASA’s doorstep and then heartily approve the budget requests that came in from the agency and from the White House. He was there to advance his own and the GOP’s agenda as it pertains to climate change—an agenda that can be boiled down to “let’s do absolutely nothing.” NASA, though much more commonly associated with Mars rovers and moon landings, blue dots and Saturn’s rings, is actually among the most important groups in the world for understanding how the Earth’s climate is changing. It sends up satellites, monitors surface and ocean temperatures, flies missions over the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets to measure melting, and conducts a variety of other scientific functions in the field. Without NASA’s efforts, the field of climate science would be years behind where it is today.

Though climate science remains a controversial topic in certain political circles, NASA itself enjoys broad public and political support. In fact, a Pew Research Center survey in early 2015 found a 68 percent favorability rating for NASA, compared with only 17 percent unfavorable. For a government agency, that’s remarkable; only the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention scored better, showing that the public really does appreciate science in a variety of forms.2 (Yes, the IRS came in last.)

The many satellites and instruments that NASA uses to measure climate, oceans, cryosphere, and more.

Credit: NASA

Given the generally positive opinion the public has about our space agency, Cruz knew he had to be careful if he was trying to cut its funding. So he used the BUTTER-UP AND UNDERCUT, a technique that equates to a magician convincing you to look at the sparkly spectacle over on this side of the stage while he makes the elephant on the other side “disappear.” Politicians looking to make what could be an unpopular point deploy this technique as a way of distracting us—“Oh, Cruz loves NASA! I agree, how cool was the Pluto flyby thing?”—while they get to the messy work of undermining science. This ploy is often used in funding battles, as we’ll see; it’s easier to pull the money rug out from under an agency if it seems like you’re an admiring superfan of that very institution.

Senator Cruz’s version of the BUTTER-UP AND UNDERCUT also happened to be full of errors about NASA’s mission and scientific foundations. Here’s a longer quote from the hearing, in which Cruz claimed that the focus on our own planet was somehow at odds with the agency’s overarching goals:

Should NASA focus primarily inwards, or outwards beyond lower Earth orbit? Since the end of the last administration we have seen a disproportionate increase in the amount of federal funds that have been allocated to the earth science program at the expense of and in comparison to exploration and space operations, planetary science, heliophysics and astrophysics, which I believe are all rooted in exploration and should be central to the core mission of NASA. . . . I am concerned that NASA in the current environment has lost its full focus on that core mission.3

All of that is essentially code for “I don’t want NASA studying climate change anymore.” The use of “inwards” as opposed to “outwards,” the focus on the concept of a “core mission”—these choices in phrasing are all intended again to highlight the grandiosity of NASA’s space exploration, the wonder we all feel at a close-up of Jupiter, the cliché of a child wanting to grow up to be an astronaut. But Cruz couldn’t have been more wrong.

Leaving the funding questions aside for a moment, it actually isn’t difficult to find out what NASA’s core mission really is. The space agency has a rich history that is almost entirely available online; deciphering its scientific function, in terms of both original intent and evolving mission, is just a matter of doing some reading.

NASA was created by the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958. This legislation was part of a hasty attempt to respond to the Soviet launch of Sputnik, the world’s first orbiting satellite, in October 1957. The founding document actually manages to refute Cruz in the very first objective listed: “The expansion of human knowledge of phenomena in the atmosphere and space.”4

The atmosphere! That would be our atmosphere, here on Earth—the one you’re living in and breathing and from which you’re drawing protection against the sun’s rays. It’s the atmosphere that has a temperature, which is warming up dramatically thanks to the burning of fossil fuels, a phenomenon we know more about thanks to—NASA.

The act doesn’t stop there. Another objective reads: “The preservation of the role of the United States as a leader in aeronautical and space science and technology and in the application thereof to the conduct of peaceful activities within and outside the atmosphere.” Again, it was clear from the very first document in NASA’s history that this agency was designed not simply to send probes to the outer reaches of the solar system, but to advance the study of our own planet as well.

This wasn’t just foundational rhetoric either. It is true that the early years of NASA focused strongly on getting humans into space, and to the moon, but even then the agency’s leaders understood that studying our planet was of the utmost importance as well. Here’s a document from 1964, three years after President Kennedy set the goal of getting to the moon, describing the nonlunar aspirations of NASA:

The fundamental objective of the Geophysics and Astronomy Program is to increase our knowledge and understanding of the space environment of the Earth, the Sun and its relationships to the Earth, the geodetic properties of the Earth, and the fundamental physical nature of the Universe.

Knowledge of these areas is basic, not only to our understanding of the problems of survival and navigation in space, but also to the improvement of our ability to make technological advances in other fields.5

A decade later, with Neil Armstrong’s “giant leap” a few years in the rearview mirror, NASA’s budget estimates listed this as the very first of its achievements: “NASA’s programs . . . extend man’s knowledge of the earth, its environment, the solar system, and the universe.”6

In 1984, as awareness of the realities of climate change and other global changes began seeping into the scientific community’s consciousness, Congress actually revised the Space Act to include a line about “the expansion of human knowledge of the Earth.”7 In the 1990 budget request, NASA administrators set a series of goals and led off with: “Advance our scientific knowledge of Earth and of the forces and systems that shape our planet.”8 How would you define “core mission”?

Even a cursory reading of NASA history shows that studying our planet—in particular, its atmosphere—has always been central to the agency’s existence. But if you listened to Cruz, you might have been blinded by the shiny spaceships over there and missed the attempt to disappear the elephant over on this side of the room.

Cruz’s BUTTER-UP AND UNDERCUT had another couple of layers to it. Ostensibly, his point was that only a limited amount of federal money can go to NASA, and those useless Earth and atmospheric sciences are sapping the coffers of the real goals, of space exploration. As we’ve seen, Cruz was spouting nonsense in claiming that the agency had somehow shifted away from space and toward our own planet, but NASA administrator (and former astronaut) Charles Bolden pointed out some additional flaws in his argument:

We can’t go anywhere if the Kennedy Space Center goes under water and we don’t know it. That’s understanding our environment. . . . It is absolutely critical that we understand Earth’s environment, because this is the only place that we have to live.9

Though this may sound like a neat rhetorical trick on Bolden’s part, this is not exaggeration!

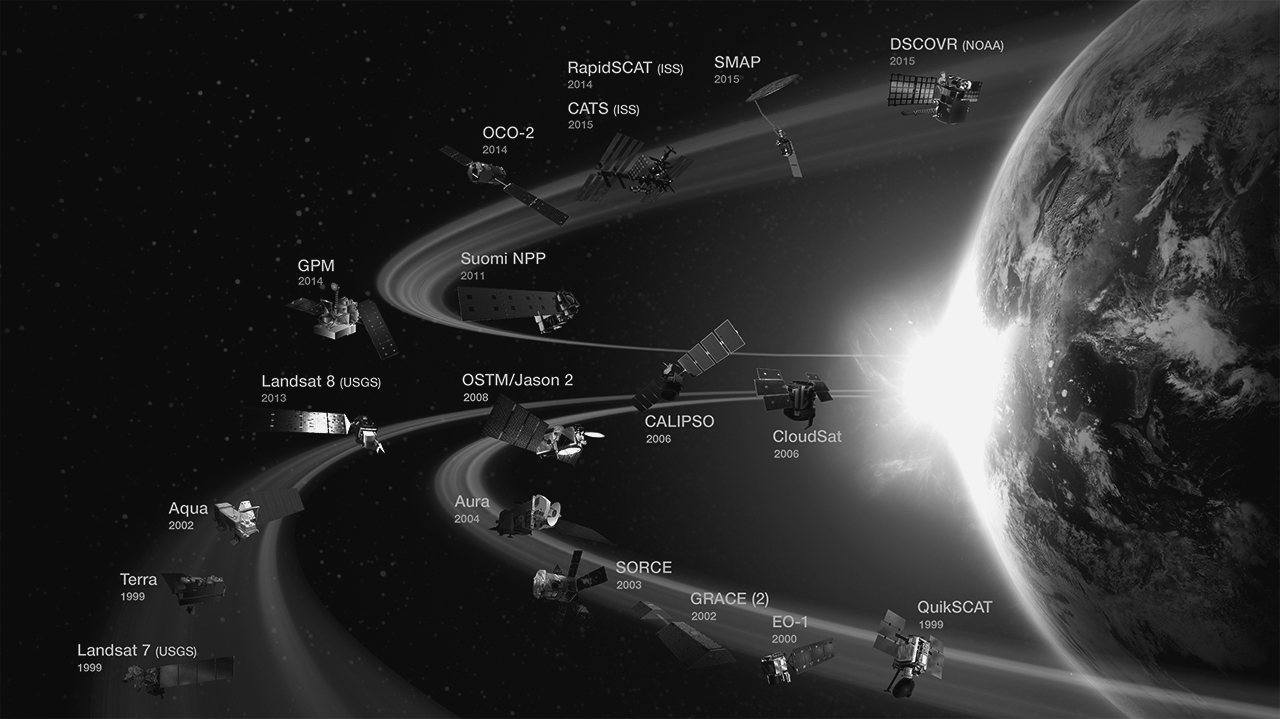

The Kennedy Space Center, where many space shuttle and rocket launches have taken place, sits on the Florida coast at Cape Canaveral. This part of Florida—well, okay, basically all of Florida—is extremely low-lying. Most of the area used by NASA is at or just above sea level. That means the warming climate, and the rising sea because of that warming climate, are a crucially important issue for the future of manned space travel.

In fact, some researchers have tried to quantify this issue. In a study published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society in 2014, NASA and Columbia University experts found that the sea has been rising at Cape Canaveral at a pace of 22.6 millimeters per decade.10 That pace, in Florida and around the world, is almost certainly accelerating11 and will continue to accelerate in the next few years and decades. What does that mean for NASA’s primary rocket launch site? Floods. Lots of floods.

A rocket lifts off from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Cape

Canaveral, Florida. Much of the center sits at or just above sea level.

Credit: NASA/Kim Shiflett

Coastal flooding at Kennedy Space Center already happens about once every ten years. By 2050, a conservative estimate is that those floods will happen every three to five years. Before too long, if we can’t slow down the warming climate and the rising sea, that site (and others like it) will be essentially unusable. Cruz wants to pull money away from climate science, but that means spending a whole lot of money later: according to the Columbia and NASA researchers, Kennedy’s infrastructure “would cost more to replace than at any other NASA site.”12 Whoops!

This is another hallmark of the BUTTER-UP AND UNDERCUT: the misdirection tends to weaken and damage the very institution or issue the speaker is admiring so breathlessly. Cruz’s version builds up NASA’s ego admirably, only to try to literally wash away its accomplishments.

There was even one more way Cruz erred during the hearing (yes, he managed to layer mistake on mistake, building an entire seawall of misleading statements, in just a few minutes of a generally positive-seeming speech). Here’s Cruz again:

That in my view is disproportionate, and it is not consistent with the reason so many talented young scientists have joined NASA. And so it’s my hope that this committee will work in a bipartisan manner to help refocus those priorities where they should be, to get back to the hard sciences, to get back to space, to focus on what makes NASA special.13

Once again, NASA is “special”; its scientists are young and “talented.” But what about that little remark about the hard sciences? Is Cruz suggesting that NASA is spending too much effort and money on “soft sciences”?

This is yet another branch of the BUTTER-UP AND UNDERCUT; the implication is that NASA’s special status arises from its focus on “hard” scientific exploits, like journeys to Mars or the study of the sun. But the agency’s earth sciences missions are a far cry from “soft” science.

The concept of hard and soft sciences isn’t exactly written in stone, but there is general agreement that “hard science” refers to disciplines including chemistry, biology, physics, or astronomy—say, anything you might use a telescope or a microscope for. Soft science, on the other hand, includes fields such as psychology or anthropology—certainly worthy areas of study for thousands of researchers around the world, though clearly they aren’t NASA’s general cup of tea.

Cruz was trying to isolate space exploration and astrophysics as the only denizens of the hard-sciences landscape, shuffling things like oceanography or atmospheric science to the land of the psychologist. Quite clearly, that’s a ridiculous distinction: NASA’s measurements of ice sheets or ocean temperatures or forest cover fall under fields that are obviously hard sciences. Even the head of the august American Geophysical Union, an association of more than sixty thousand Earth and space scientists, took issue with Cruz’s pooh-poohing of NASA’s work. In a letter addressed to the senator, the AGU’s executive director, Christine McEntee, wrote:

Earth sciences are a fundamental part of science. They constitute hard sciences that help us understand the world we live in and provide a basis for knowledge and understanding of natural hazards, weather forecasting, air quality, and water availability, among other concerns.14

She pointed out that NASA’s earth science priorities are based on reports known as decadal surveys, produced by the National Academy of Sciences. These offer a thorough examination of where the scientific priorities should lie, based on input from a wide variety of the country’s best scientists. The last such survey, published in 2007, suggested that the “U.S. government, working in concert with the private sector, academe, the public, and its international partners, should renew its investment in Earth-observing systems and restore its leadership in Earth science and applications.”15 The funding changes that Cruz is so passionately against are a direct result of NASA—horrors!—listening to scientific recommendations.

Once again, it is clear that this type of rhetorical device can be particularly devastating, as it serves to mangle the foundational nature of the topic in question. NASA is great, sure, but some of its most important research is just about useless, if you take Cruz at his word. And NASA is not the only scientific institution to get buttered up on its way to a brutal teardown.

REMEMBER BIRD FLU? Avian influenza has had a few moments in the media sun in the last decade or two, sandwiched around some swine flu hysteria. The virus spread through birds of various types—first in Asia, and later in Europe and North America. Occasionally it managed to infect humans, and it had a high mortality rate when it did, but it proved to be generally difficult to transmit between people. In other words, bird flu represents one of many near misses when it comes to the world’s next pandemic.16

Scientists have long warned that influenza in one form or another is likely at some point to pose a serious risk to humanity. The Spanish flu outbreak of 1918 killed more than twenty million people, and subsequent outbreaks in 1957 and 1968 killed many as well. Flu viruses change every year, mutate in subtle ways, and jump between animals of various types and people; it is a difficult threat to get hold of. And so, when avian influenza escaped the confines of Thailand and Cambodia and was found in birds in Turkey, Romania, Croatia, and even the United Kingdom in October 2005, the world took it very, very seriously.17

So seriously, in fact, that President George W. Bush started throwing money at the problem. Bush visited the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, in November 2005 to discuss the threat of an influenza pandemic, to advocate for a massive funding push for research and preparedness, and to praise the great work that NIH scientists do. Skepticism is the appropriate response at this point.

Yes, Bush engaged in an example of the BUTTER-UP AND UNDERCUT at the NIH, though his effort was a bit more subtle than Ted Cruz’s elephant-vanishing NASA trick. Here’s part of Bush’s speech to the NIH:

For more than a century, the NIH has been at the forefront of this country’s efforts to prevent, detect and treat disease. And I appreciate the good work you’re doing here. This is an important facility, it’s an important complex. The people who work here are really important to the security of this nation.18

The NIH is wonderful! Bush went on to outline specific goals and strategies for preventing and responding to pandemic disease outbreaks; he said he had requested $251 million from Congress to help train and equip foreign partners, $2.2 billion to purchase flu vaccines and antiviral medications such as Tamiflu, and $2.8 billion more for research into novel ways to produce those vaccines more quickly after an outbreak hits. These were good, proactive ideas, supported by most rational people. And if you listened to the entire speech, there would be no indication at all that Bush was anything but supportive of the important work done by scientists at the NIH and other institutions that receive funding from the NIH.

In this case, the misdirection was wholesale: Bush said one thing, but he spent years doing another. The NIH saw its total budget double in the late 1990s and early 2000s, which meant that scientists around the country were able to fund more projects and do more basic research on everything from Alzheimer’s to diabetes. But once that doubling was complete, Bush’s apparent disdain for science led to a stagnation in funding over several years; in fact, the NIH budget has actually declined since 2003, if inflation is taken into account.

When Bush gave his bird flu speech to the NIH, featuring his new requests for funding, fiscal year 2006 had just begun. The baseline NIH budget for that year was $28.56 billion, amazingly representing a decrease from 2005, when it was $28.59 billion.19 A year later, the budget was nudged up to just $29.61 billion—an increase that barely kept up with inflation.

During these ongoing years of stagnation, scientists around the country have expressed dismay that basic science research is being shortchanged in favor of other budgeting priorities—like, say, a couple of wars. To be clear, President Obama has obviously played a role in budgeting during this period as well, and though he has not been working with a particularly friendly Congress, he is not free from blame. Toward the end of his presidency, however, Obama has managed to inject some large increases into the NIH coffers.20

Here’s why this matters: the NIH is the primary source of funding for basic science research in the United States. There are other government agencies that fund research, such as the National Science Foundation (NSF), and individual universities certainly contribute some of their own money, but in short, as the NIH goes, so goes science in America. Scientists at every university and institute in the country submit grant applications—over fifty-one thousand of them in 2014 alone21—in the hopes that panels of experts will select their projects as worthy of funding. If you get funded, great, you’re all set to bear down and get to work. If not? Well, hopefully your university can prop you up with some funding for a while, or you can find sources of money elsewhere. But you may find your job at risk if you can’t secure an NIH or NSF grant within a few years.

There will always be some researchers whose work isn’t quite up to snuff; we can’t fund everything. But expanding the NIH budget means being able to cast a wider net, to do basic research on a whole host of topics that, though they may sound silly when described literally (as we’ll see in Chapter 6), could yield really important discoveries later on. So, keeping the NIH and NSF funded to a reasonable level is a crucial part of science and health. And if you listened to just President Bush’s speech about bird flu, it would sound like he agreed with that sentiment.

Bush, though, clearly didn’t agree. His NIH budget requests from 2003 through the end of his presidency seemed to say: “Meh.” It’s not like he proposed cutting the NIH completely or anything so drastic; again, some things, like basic research into diseases that affect all of us, are unassailable. But most people won’t notice an ostensible drop in funding for basic science research, especially if you make speeches like Bush did, touting how the NIH and its people are “really important to the security of this nation.”

He loves the NIH! Pay no attention to the cuts in funding that sent grant approval rates spiraling toward the single digits!

Bush’s version of the BUTTER-UP AND UNDERCUT is something of a long con. In public, he said all the right things about how crucial basic research is to society. But when it came down to it, he didn’t care enough about science to put the government’s money where his mouth was. This duplicity played out over almost his entire time in the Oval Office. In 2007, after several years of stagnant NIH funding, Bush vetoed a spending bill that would have added an extra $1 billion to NIH coffers22—still not even enough to match the rate of inflation. In a speech, he likened Congress to “a teenager with a new credit card.”23

The lack of support for basic research has had real, demonstrable effects. When the Ebola outbreak hit West Africa in 2014, and fear spread that this deadly disease could proliferate into Europe and North America, scientists rushed to try to find a vaccine. Francis Collins, the director of the NIH, had this to say about that effort:

Frankly, if we had not gone through our 10-year slide in research support, we probably would have had a vaccine in time for this that would’ve gone through clinical trials and would have been ready.24

Again, basic science research often isn’t the sexiest line item on a government ledger. Talking up the importance of science while cutting off the legs of the research community, though, ends up hurting all of us.

The BUTTER-UP AND UNDERCUT is among the more nefarious of the errors and rhetorical devices explored in this book. It carries an unmistakable air of intent: politicians have to try to use this technique, have to understand that they are walking a tightrope balanced between positive public opinion and negative action. By fixing our attention away from where the sneaky stuff is going on, they apply a magician’s showmanship to the act of undermining scientific progress—an ugly bit of sleight of hand.