A HUSBAND AND WIFE LIKE TO TRADE OFF HOUSEHOLD chores every now and then. From March through June, she does the gardening, planting a whole smorgasbord of vegetables. In July, he takes over. After a week, he proudly marches inside with a basket full of tomatoes, squash, green beans, and eggplant.

The dinner guests arrive that Saturday night and dig in to a meal filled with these locally grown delicacies. The husband crows: “I grew them all myself!” And then he sleeps on the couch.

In some scientific fields, just as in gardening, there is often a time lag between when seeds are planted and when the resulting bounty is harvested. Or, even if the timing is shorter, the exact underlying reasons for the harvest may be a bit unclear. That lack of clarity is a politician’s best friend.

The CREDIT SNATCH is a ploy whereby politicians claim some sort of accomplishment just because it happened “on their watch.” They don’t bother to explain the underlying, actual reasons for that accomplishment, which often is a result of a previous administration’s policies, or simply has some mechanism behind it that in no way is a result of the elected official’s specific actions.

Let’s start with former Texas governor and occasional presidential candidate Rick Perry. In a speech in February 2015, Perry listed a litany of accomplishments related to emissions of various types of pollutants over a period when both population and jobs were on the rise (and he managed to get in a jab or two highlighting his climate science denial as well):

During that same [seven-year] period of time using thoughtful, incentive-based regulation, we decreased our nitrogen oxide levels—which, by the way, is a real pollutant, it’s a real emission—nitrogen oxide levels were down by 62½ percent, ozone levels were down by 23 percent, sulfur dioxide levels down by 50 percent, and our CO2 levels were down—whether you believe in this whole concept of climate change or not—CO2 levels were down by 9 percent in that state. Isn’t that the goal of what we were working towards? . . . We put policies in place that helped remove old dirty-burning diesel engines from the fleets. We were able to transition our electrical power system to the natural gas burning.1

That’s a lot of numbers, a lot of molecules, and a lot of odd grammatical errors. All those reductions certainly sound good, and in fact Perry was correct—more or less, depending on which years he meant to include—on most (but not all) of them. The questions are, why did they happen, and just how impressive are these reductions?

Let’s take a look at nitrogen oxide first, the one pollutant reduction for which Perry’s number is actually quite misleading. Nitrogen oxides, referred to as NOx, are an entire family of highly reactive gases that form when fossil fuels are burned. That means NOx is emitted from car and truck tailpipes, from factories, and of course from power plants burning coal or natural gas.

The NOx reduction that Perry mentioned (62.5 percent) is a sort of homemade statistic by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, and it includes only emissions from “point sources”—that is, major emitters like factory smokestacks and power plants.2 Those are a big source of NOx, but so are “mobile sources”—cars and trucks. In fact, mobile sources account for more than half of Texas NOx emissions, and point sources account for only about one-quarter.3

This is notable because Perry specifically mentioned policies that had an effect on “the fleets”—mobile sources of emissions. Some of those policies certainly did help clean up the air a little bit. For example, the Diesel Emissions Reduction Incentive is estimated to cut about 161,000 tons of NOx over the lifetime of the vehicles it affects in Texas. In 2014, the program resulted in about 54 tons fewer emissions every day, or 20,000 for the year. That sounds great, until you realize that the state’s mobile-source NOx emissions topped 700,000 tons in 2011. So Perry’s policies may have put a tiny dent in total emissions, but the reduction he quoted had nothing to do with those policies.

Next up, sulfur dioxide. This noxious gas is produced almost entirely by power plants and large industrial facilities. It may sound familiar, as it is the primary culprit in the formation of acid rain, and the topic involved with Ronald Reagan’s founding “not a scientist” pronouncement. Perry is correct about the 50 percent reduction, which again sounds great . . . until you look at the entire SO2 trend for the United States. Though the years Perry was highlighting are a bit unclear, total US emissions dropped from 11.7 million tons in 2007 all the way to just under 5 million tons in 2014—a reduction of over 57 percent.4

The declines in SO2 and NOx levels also have almost nothing to do with any of Rick Perry’s policies. In fact, these declines have been ongoing for more than two decades, a result of federal policies—exactly the type of federal, top-down regulation that Perry was speechifying against.

In 1990, Congress passed amendments to the Clean Air Act, in large part as a response to concerns about acid rain. The Energy Information Administration, a government institution that collects and analyzes energy and environmental data, had this to say about reductions in emissions:

The decline in SO2 and NOx emissions began soon after enactment of the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments, which established a national cap-and-trade program for SO2 and required other controls for NOx emissions from fossil-fueled electric power plants.5

The EIA also attributed some declines to another federal action, the 2005 Clean Air Interstate Rule. Generally speaking, SO2 reductions have occurred because of strategies implemented by power plants to reduce emissions and meet federally mandated targets. Does that sound like something the Texas governor should be taking credit for?

Finally, Perry decided to deem himself and his administration responsible for a 9 percent reduction in carbon dioxide levels, “whether you believe in this whole concept of climate change or not.” Leaving behind the fact that, if one did not believe in climate change (meaning one does not understand science in the least), then reducing CO2 levels would not be an accomplishment to be touted, Perry was again misleading in his claim of credit.

According to EIA figures that were available at the time of Perry’s comments, CO2 emissions in Texas had indeed fallen by 9 percent between the year he took office (2000) and 2011.6 The only evidence Perry offered for what might have driven down those CO2 emission levels was the clean-diesel program discussed already, and this: “We were able to transition our electrical power system to the natural gas burning.”

We can dispense with both of the arguments in his awkward sentence fragments quickly. First: The transportation sector’s CO2 emissions didn’t fall by 9 percent over this time period. They rose, by about 7 million metric tons, or about 4 percent.

Okay, what about the electric power sector? Nope, again, CO2 emissions went up about 4 percent, or about 10 million metric tons. And even if that were not true, Perry’s argument about transitioning to natural gas shouldn’t really go on his résumé either, since, as we’ve already seen, the natural gas boom in the United States was a result of improved technologies and economic factors, not some policy magic at the state level.

The decline in carbon dioxide emissions actually came from one particular source: the industrial sector. Manufacturing has declined in general in recent decades in the United States, and emissions have followed suit. In Texas, using the numbers Perry had available, CO2 from industrial sources declined from about 285 million metric tons in 2000 all the way to 204.6 million metric tons in 2011—a drop of more than 28 percent.

This is an even greater drop than the nationwide trend. According to the EPA, “Greenhouse gas emissions from industry have declined by almost 12% since 1990, while emissions from most other sectors have increased.”7 This sort of decline isn’t really the kind of accomplishment most governors are aching to take credit for; in fact, many candidate stump speeches harp on the need to bring back manufacturing jobs, not eliminate them further. And importantly, no one is blaming individual governors for industrial decline; the US State Department’s 2014 Climate Action Report explains the drop in industrial output and resultant emissions as follows: “This decline is due to structural changes in the US economy (i.e., shifts from a manufacturing-based to a service-based economy), fuel switching, and efficiency improvements.”8

We’ve already seen that the electric power sector’s emissions actually rose during Perry’s tenure, but let’s take another look at his claim of a transition toward natural gas, a fossil fuel that emits about half the amount of CO2 emitted from burning coal. The portion of Texas’s power supply coming from natural gas actually dropped while Perry was in office, from 67 percent in 2000 to about 61 percent in 2012. Coal use dropped too, from 24 percent to about 21 percent.

The big, fundamental change in Texas electricity had nothing to do with those fossil fuels, but in fact with one source of power: wind. Texas has far and away the most wind power in the country, at almost 18,000 megawatts installed capacity through the end of 2015 (California is second, at just over 6,000 megawatts).9 That’s up from only 184 megawatts at the end of 2000,10 which took the energy source from less than 1 percent up to well above 10 percent.

Wind power has helped the emissions from the power sector rise more slowly than otherwise; they have risen because of a total capacity increase, meaning more fossil fuels have burned even as their proportion of the energy supply has dwindled. Though Perry deserves some credit for helping foster the wind power industry in Texas, the growth had more to do with the potential for profit for landowners and ranchers and the simple fact that the plains of West Texas are an extremely windy place.11 Moreover, the state’s Renewable Portfolio Standard was passed in 1999,12 before Perry took office.

This litany of misplaced responsibility is a wonderfully thorough example of the CREDIT SNATCH. The politician can claim that all the numbers cited are correct (more or less), and what person listening to the stump speech will bother to check the underlying mechanisms? Emissions fell; that sounds like a good thing, right? It happened on Perry’s watch; therefore Perry gets the credit. The effect is that politicians get to claim a track record they don’t have. In Perry’s case, claiming he was responsible for an improved environment in Texas is particularly galling. Here’s how the Washington Post described his record as governor (when he still had four more years to keep this up):

He filed a lawsuit against the EPA’s greenhouse gas emissions regulations on behalf of the state, a suit widely expected to fail. Perry has said that he prays daily for the EPA rules to be reversed. He has consistently defended oil and coal interests in Texas, notably dubbing the BP oil well blowout an “act of God” and opposing the Obama administration’s efforts to regulate offshore drilling in the wake of the disaster. He also fast-tracked environmental permits for a number of coal plants in 2005, cutting in half the normal review period.13

And yet there he was, claiming drops in pollution as his own grand creations.

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES ARE PARTICULARLY good fodder for a CREDIT SNATCH. Reducing pollution is a catchy and universally popular idea, even if your audience isn’t entirely sure what the pollution in question is, and the reasons for those reductions are often nebulous enough that anyone could take credit. “I was there when it happened!” is good enough for many a politician.

Energy supplies are, of course, intimately linked to emissions, and they are another prime target for credit thievery. Here’s New Jersey governor Chris Christie, talking at the Iowa Ag Summit in 2015 as he prepared for his presidential run:

In New Jersey, the northeastern states have been part of something called the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, which was essentially a regional cap-and-trade program. When I became governor, I pulled out of that; I don’t believe cap-and-trade makes sense. And what’s happened in New Jersey? We’re now the second largest solar-producing state in the country, because we’ve gone to market-based solutions on helping solar thrive in our state. And only California produces more solar energy now than New Jersey.14

Christie suggested that removing his state from the RGGI (pronounced “Reggie”), which is indeed a regional cap-and-trade program aimed at lowering carbon emissions, somehow resulted in the solar power boom. Essentially, he took one decisive action—pulling out of RGGI—and claimed it as the reason for this clear example of progress. This is about as drastic and audacious a CREDIT SNATCH as one can imagine.

First off, the specific claim: solar power is booming in New Jersey, and this tiny, northern, cloudy state is somehow among the biggest solar producers in the country. Actually true! Again, a hallmark of this technique is to base your claim on a true, verifiable, generally popular accomplishment. Christie checked that box off perfectly.

According to the Solar Energy Industries Association, New Jersey had more than 1.5 gigawatts of installed solar capacity (enough to power about three hundred thousand homes) partway through 2015, ranking it third in the country behind sunny California and very sunny Arizona (it was second until relatively recently).15

The question is, what exactly has made this cloudy state that could fit inside California eighteen times over such a solar powerhouse? The answer has very little to do with Chris Christie. Instead, it has to do with state policies implemented under previous governors. The state’s Clean Energy Program dates to 2001, and the Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), which sets a target for how much of a state’s power comes from renewable sources, actually was first adopted in 1999 and subsequently updated several times.16

Perhaps the most important policy is the Solar Renewable Energy Certificate (SREC) program. Begun in March 2004, the SREC program is essentially a market for the generation of solar power: by producing a certain amount of power from solar (1,000 kilowatt-hours, or a bit more than an average American home uses in one month17), the owner earns a single SREC. This credit can be sold for the going rate, generally to utility companies, enabling them to meet requirements set by the state for renewable energy generation.

Most experts directly credit the SREC program, along with the rapidly dropping costs of producing solar panels, with New Jersey’s solar boom. Christie only took office in 2010, and though the start of his tenure coincided with a big jump in solar installations, that wasn’t his doing, but instead was a reflection of a big jump in SREC prices. A subsequent drop in solar installations in 2013 again mirrored the market, rather than being the consequence of any executive action.

Christie himself has had a mixed relationship with the SREC and RPS programs. Relatively early in his administration, in June 2011, Christie proposed an energy plan that would actually cut the RPS, bringing the total of renewable energy required down from 30 percent to 22.5 percent.18 This was before the solar market peaked and bottomed out, meaning that Christie looked at the booming solar installations and decided to slow them down. To his credit, however, when the SREC market plummeted a year later, he reversed course and signed a solar “resurrection bill” designed to address the supply-and-demand imbalance in the SREC market.19 More recently, Christie vehemently opposed the EPA’s Clean Power Plan, a federal regulation designed to cut carbon dioxide emissions from power plants20—a move that anyone in favor of expanding renewable energy would not condone.

Of course, in his comments about his energy policy prowess, Christie mentioned none of this. Instead, he focused on his state’s removal from RGGI and what he termed a return to “market-based solutions.” This makes no sense at all. RGGI, as Christie himself described, is a regional cap-and-trade program. That means it creates a market in which polluters (factories, power plants, and so on) buy and sell emissions allowances in an effort to reduce those emissions. Doesn’t that sound remarkably like a market-based solution? It should! Here’s the very first sentence on RGGI’s website: “The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) is the first market-based regulatory program in the United States to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”21 Christie pulled out of the idea he professes to love so well! And it was working: RGGI estimates that in its first four years of existence, it raised about $1 billion for the states involved and prevented 10 million tons of CO2 emissions, equivalent to taking nearly two million cars off the roads entirely.22

This closer look reveals that New Jersey’s impressive solar power progress is based on groundwork laid long before Christie took office, and Christie’s tenure may have actually impeded the progress of renewable energy. But why let that stand in the way of the governor’s lovely revisionist history?

THE CREDIT SNATCH IS most commonly used by politicians running for election or reelection, as was the case with Perry and Christie. Sometimes, though, it rears its head from politicians on the way out the door. Can you guess who said the following?

By encouraging cooperative conservation, innovation, and new technologies, my Administration has compiled a strong environmental record.23

If you guessed George W. Bush, you’re right! A snapshot of his White House website from 2008, at the end of his tenure, shows a couple more specific boasts: US wind power production increased by more than 400 percent since 2001, and solar power capacity doubled between 2000 and 2007.24 Both sound great, but it is exceptionally difficult to draw a straight line from anything the Bush White House actually did to those increases in wind and solar, or really to any sort of “strong environmental record.”

Two factors are primarily responsible for the nationwide growth in renewable energy: technological progress and state policy. State policy means those Renewable Portfolio Standards, largely: a total of twenty-nine states (plus Washington, DC) had an RPS in late 2015, while another eight have a nonbinding renewable energy “goal.” Most of the renewable energy in the United States sits in states that encouraged such development with an RPS. This is not a coincidence, and all this growth has little to do with who was president at the time.

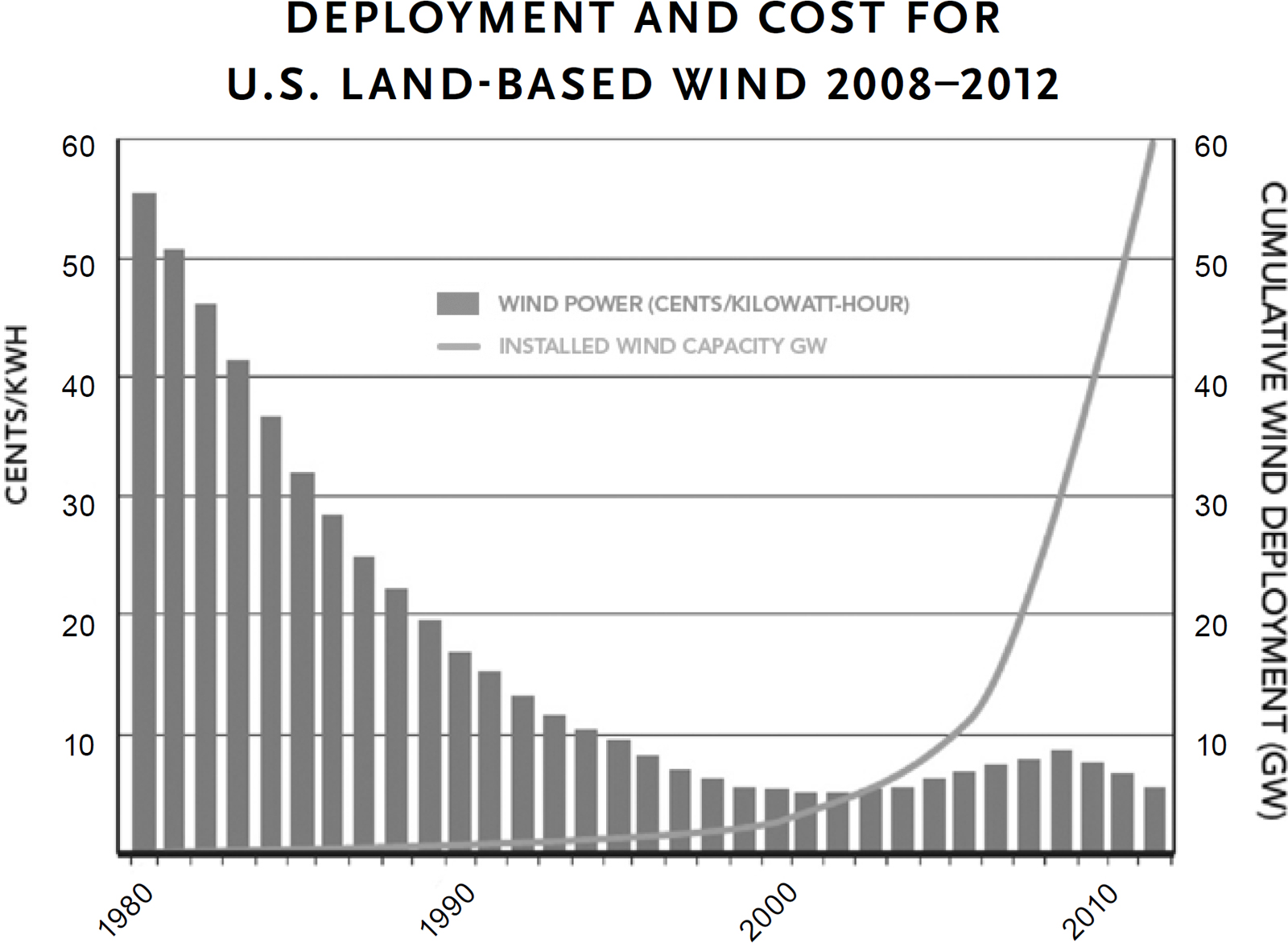

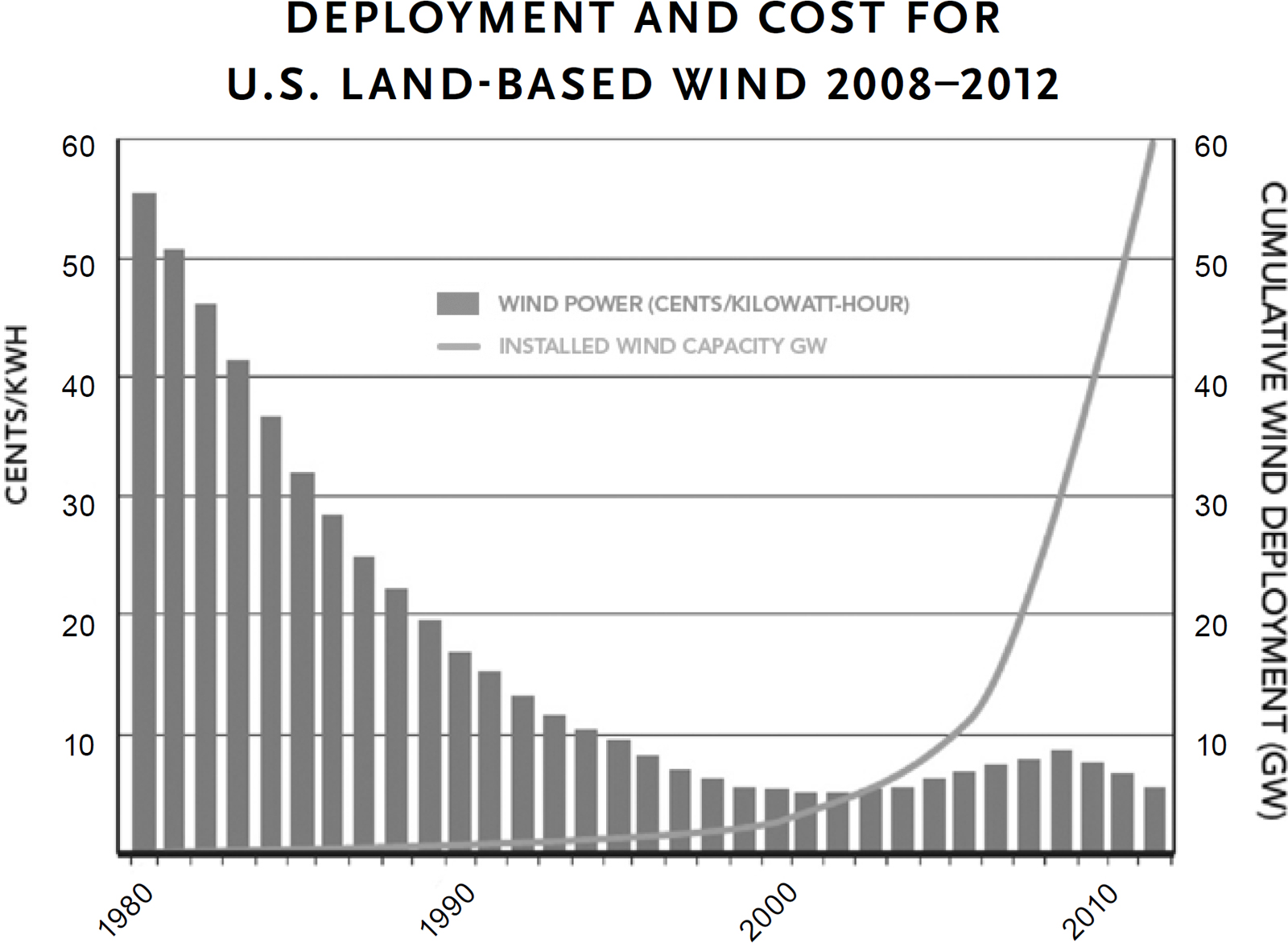

The other factor was technological innovation. Advances in the manufacturing of solar cells and wind turbines have driven costs down to a level at which these power sources can compete with coal and natural gas. Here’s a Department of Energy chart showing falling costs and subsequently rising deployment of wind power:25

Credit: US Department of Energy

Solar power has had an equally epic price drop over a couple of decades, likely with even more reductions soon to follow. In this case, the federal government actually has played a role in that drop with SunShot, a Department of Energy funding initiative specifically aimed at making solar cost-competitive with other forms of energy. But the initiative was announced in February 2011, long after Bush had left office, and after five of its ten years, the solar industry had made it 70 percent of the way to specific cost goals.26

President Bush’s actual accomplishments with regard to renewable energy are less than stellar. His 2004 budget, for example, slashed funding for wind power development by 5.5 percent and for geothermal energy by 3.8 percent.27 In 2006 he doubled down on this approach, cutting the Department of Energy’s renewable energy budget by 5.6 percent from the previous year.28 This happened yet again at the end of his presidency, with his 2008 budget. He signed the Energy Policy Act of 2005—which the New York Times said “would shower billions in undeserved tax breaks” on oil and gas companies29—only months after saying that cheap oil prices were more than enough incentive for fossil fuel companies.30 He also opposed subsidizing wind and solar power, along with energy efficiency measures, at various times.31 Not exactly the record of a solar and wind maven, is it?

The underlying lesson behind the CREDIT SNATCH is one we’ve already seen: correlation does not equal causation. The simple act of being in office when something improves or happens does not mean that a particular politician’s presence made it happen. The impact of this technique has a lot to do with its most common deployment, during elections. If voters believe a candidate has a track record on a certain issue that matters to them, it could make them more likely to put that candidate back in office. Once that happens, the lack of true support for the issue in question could rear its head in ugly ways: slowed growth in renewable energy, say, or the lack of any real effort to cut dangerous emissions. When a politician claims credit for a big, long-term trend, do a quick search on what has caused that trend; you just might uncover some credit thievery.