Despite its being home to over a thousand medical students and a plethora of doctors, hospitals, and medical schools, Philadelphia was still a place of chaos: socially, politically, and medically.

Crushing poverty had become an everyday fixture of Philadelphia life. One neighborhood (the relatively small area between 5th and 8th Streets, from Lombard to Fitzwater) had become so crammed with the city’s most degraded classes that it earned the nickname the Infected District.

A reporter from The Evening Bulletin investigated the harrowing neighborhood and found conditions among the 4,000–5,000 people who lived there so wretched that he felt “incapable of reporting their full horrors to his readers.” This area of the city—less than a mile from where Jefferson Medical College held its classes—seemed like a different world from the rarefied circles in which the doctors of the city drank imported French wine while dining on oysters, terrapin, quail, and ice cream.

In the Infected District, it was common practice for shops to charge a penny for a meal that was made up entirely of scraps begged at the back doors of the wealthy. It was a common custom for one enterprising individual unable to afford rent at even the lowliest of flophouses to secure a room at a boardinghouse for twelve and a half cents a day, and then sublet as many sleeping spaces as could fit at a bargain price of two cents a head.

The police and fire department at the time were of little help. The police were known as watchmen because the uniformed men could—and often did—lock themselves in specially constructed “watch-boxes” to protect themselves from the same criminals from which they were supposed to be protecting the community. The watch-box method would be abandoned, however, when rioting mobs realized they could simply destroy the watch-boxes and kill the police officers.

The fire department was equally troubled. The all-volunteer companies were neighborhood-based, and just like the neighborhoods they had sworn to protect, some “were very respectable” while others “were the reverse,” as one doctor later observed.

“The more humble and gentle the name of the [firefighting] company, the more apt it was to be pugnacious,” he recalled. “For instance, ‘The Good Will’ would fight anything at any time.”

A watcher in the State House tower was tasked to be on the lookout for fires. When one was spotted, he would then alert all the fire departments en masse via taps on a bell. The disorder and chaos that would follow those bell taps was legendary.

“When there was a fire, hand engines and hose carriages were dragged by men, a shrieking crowd ran along the pavements, and quiet citizens got out of the way, as there was ‘often a fight which would have brought joy to the heart of a Comanche or Pawnee,’” a Philadelphian recalled in harrowing detail. “Great disorders and riotous demonstrations were frequent . . . the firemen fought citizens, policemen and other firemen with scrupulous impartiality. One summer, two rival fire companies fought each other instead of a fire in the neighborhood of Eighth and Fitzwater Streets and the battle lasted all day. Two weeks later, the carriage of the Franklin Hose was thrown into the Delaware by a rival company.”

One of the major challenging issues of 1840s Philadelphia was alcoholism, and the violence and death that seemed always to accompany it. By 1841, there were more than nine hundred taverns within Philadelphia County. In the Infected District, rum was commonly sold for a penny a glass, which might explain why the phrase “Rum is at the root of the trouble” was so commonly used when discussing the city’s problems.

The threat that alcoholism posed to Philadelphia was so real that, by the early 1840s, the county supported nineteen temperance societies, which proudly claimed a total of seven thousand members. Total-abstinence societies—groups that forbade their members from consuming any alcohol whatsoever—topped them with more than ten thousand members.

Still, rampant alcoholism was an issue. When it came to the lower classes, alcohol-related crimes, injuries, and deaths only served to feed the popular belief that the poor had earned their lot in life and thus deserved no charity.

Some took this idea even further, espousing the notion that there were people who were simply born to be poor, and who were actually quite happy living as they did. “He that is down needs fear no fall,” one clergyman of the time helpfully offered to explain why he thought the lower classes should be “of good cheer.”

But it wasn’t just the poor that suffered in this overflowing city. Philadelphia’s working classes were consistently brutalized under the yoke of the free market.

Men of all ages and backgrounds arrived in Philadelphia daily—from Europe, Asia, and the American South—all looking for work. The population of the city exploded from less than 140,000 people in 1820 to more than 250,000 by 1842, and significant credit could be given to the city’s industrial output.

Foundries, factories, and mills of all kinds could be found within the city’s borders. There were mills for spinning cotton and weaving wool. Factories that built locomotives, fire engines, and chandeliers. The factories of Philadelphia produced, at their height, nearly one-fourth of the nation’s steel, and the city’s twelve sugar refineries made it the country’s largest single supplier of commercial sugar.

To keep this extraordinary confluence of businesses going, these factories, mills, and foundries needed workers, but the city’s exploding population always seemed to contain more eager workers than were needed. Philadelphians were often forced by circumstance to accept abysmal wages for what inevitably proved to be long hours of relentlessly grueling work.

Unskilled factory operatives, coal heavers, shipyard workers, and carpenters were paid less than a dollar a day to work fourteen hours a day, six days a week. Most factories recognized only the Fourth of July as a holiday, and vacation and sick time were, of course, nonexistent.

Men had to compete not only with each other for these backbreaking jobs, but with children as well. In a time before laws prohibited child labor, factory and mill owners were happy to put even the youngest children to work. In one dramatic case, the Dyottville Glass Works near Kensington employed 300 people in its industrial plant. Of those 300 employees, 225 were boys, “some not yet eight years of age.”

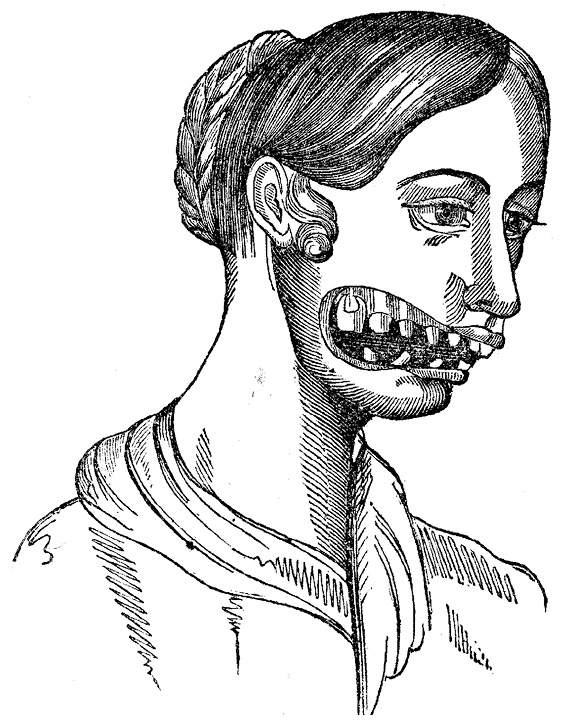

Young girls were not exempt from the furious maw of factory work. The area’s matchstick factories in particular sought them out, paying a wage of $2.50 a week. The girls happily took the work to help keep food on their families’ tables, having no idea, of course, that they were being slowly poisoned by the factories’ dangerous chemicals. The girls worked long hours in poorly ventilated rooms, licking their own chemical-coated fingers often to help in processing so many small slivers of wood, so difficult to see and keep track of in the dark factory setting. And what would start out as simply toothache and painful swollen gums would swiftly evolve into rotting tissue. Soon the girls’ jaws were covered with large weeping abscesses so deep, the bone could be seen and the wound would unremittingly leak a foul-smelling discharge.

Woman with Ulcer of the Cheek

The condition became so common it would eventually earn a nickname: phossy jaw (phosphorus being the active ingredient in matches during the mid to late nineteenth century). And if the slow disfigurement (with accompanying brain damage and inevitable organ failure) weren’t horrific enough, the chemicals the workers ingested daily caused the exposed jawbones of these now-deformed girls to glow greenish white in the dark.

Despite all the advancements of the time, the medical profession simply could not keep up with the increasingly deadly health challenges that this newly industrialized city presented. And one of its largest failings was in women’s health.