Infectious disease had always been a problem for Philadelphia—and as its population exploded, the problem only grew worse.

While the city had enjoyed a decline in the mortality rate among its citizens during the years between 1825 and 1850—a triumph considering that similar cities like Boston, Baltimore, and New York City saw increases—their good fortune had begun to run out.

An outbreak of Asiatic cholera killed 1,012 Philadelphians in 1849. An eruption of smallpox took 427 lives in 1852. Yellow fever swept into the city the following year and left 128 corpses in its wake. These numbers were in addition to the deaths caused by illnesses that had become so common in Philadelphia that people thought suffering from them was just an unfortunate, but unavoidable, part of city life.

The frequently recurring disease, typhus, struck the city throughout the 1840s, killing 205 people in 1848 alone. Dysentery terrorized the city every summer, especially the poorest neighborhoods, and would go on to kill more than 1,700 citizens between 1848 and 1851. Meanwhile, malarial fevers spread easily and frequently in the city’s low, flat lands between the rivers, and tuberculosis, often called consumption, was also a constant presence.

Ten times as many people died of malaria and tuberculosis in Philadelphia than died of the much more feared cholera, but because the malaria and tuberculosis victims passed away gradually and quietly—they died “romantically,” as it was termed—the general public took to dreading cholera more, for it was known for killing its sufferers “with terrifying speed and ugliness.”

It was not uncommon for several diseases to have devastating outbreaks at once. In 1852—the same year that smallpox killed more than 400 Philadelphians—433 died of scarlet fever, 558 more of dysentery, and more than 1,200 were claimed by tuberculosis.

Philadelphia civic leaders had finally begun to suspect that there was a connection between sanitation and disease. Starting in 1849, they began thoroughly cleaning streets, waterways, and other public spaces in an effort to discourage the constant scourge of disease. Some politicians and religious leaders still insisted that poverty was “the wages of sin” and spoke out against using public money to clean poor neighborhoods. But the practice spoke highly of the intuitiveness of the day’s leaders and would prove a blessing to all the citizens of the city that, for once, its government used sanitary measures—instead of prayer—to fight the constant epidemics.

• • •

But if there was a stubborn holdout in Philadelphia when it came to not believing in the infectiousness of diseases, it was Charles D. Meigs.

Meigs had become a star in American medicine precisely because of how deeply—and sometimes blindly—he held on to his beliefs, and the incredible lengths to which he would go to fiercely defend them.

Meigs’s career had been defined by his passion for what he considered “the right way” to do things and the bold, shamelessly theatrical style—in both lecture and print—with which he espoused these theories. His generation had held that physicians were almost all-knowing gods with whom you should never disagree, and Meigs had qualms about indulging in sentimentalism or speculation to make his point. He thought nothing of belittling his patients, or even his fellow doctors, to ensure his opinions were heard. While it was true that his vision of medicine had begun to be challenged over the course of his career, he had never truly been “one-upped.” And because of this, he had always been respected . . . and perhaps a bit feared.

But in the 1850s, the cracks began to show, and the medical community began to look more critically upon the chest-puffing, fact-refuting style of doctors like Meigs.

When the newly formed American Medical Association reviewed Meigs’s textbook Observations on Certain of the Diseases of Young Children, its criticism of the work was clear: “Acknowledging the rare merits which belong to the work as a learned contribution, enriched by the observations of a mind, well-calculated to elicit what is valuable and original in an extensive field of experience, we cannot but speak of it at the same time as presenting faults too glaring to be overlooked and of sufficient importance to merit condemnation.”

These faults included “an affected obscure style and a fondness for speculations, which, however brilliant and ingenious they may appear, are in many instances baseless”; and how Meigs took “the strangest liberties with language, apparently avoiding the simplest and most concise expressions, to extemporize terms more recondite and obscure, framed too without regard to rule or precedent, or indeed to scientific nomenclature, and which are not to be found in any accredited authority.” Additionally, “his fondness for what is speculative leads him often to prefer what is novel, ingenious, and peculiarly his own, to that which is more worthy of and sanctioned by common acceptation.”

The reviewer continued, remarking that he “notice[d] also a disposition to exclusiveness, exhibited by taking into view some facts in the explanation of a topic to the disregard of others which would interfere with the unity of the explanation he would cherish.” The reviewer concluded that “[h]owever valuable, suggestive, and instructive these chapters by Professor Meigs may be in the hands of the matured, reflecting, experienced physician, we would hesitate to expose the impressible, theorizing mind of the student to their seductions.”

To receive such a scathing review from a lauded medical institution must have come as quite a shock to Meigs, whose professional life had always been conducted as if his opinions would never be questioned or proven wrong.

And this was just the beginning.

• • •

“Meigs was all his life a non-believer in the infectious nature of puerperal fever,” a fellow doctor later wrote of Meigs, “notwithstanding that for a time numerous facts demonstrative of the incorrectness of his belief almost daily stared him in the face.”

Puerperal fever, also known at the time as childbed fever, was a tragically common infection among new mothers. In a time before the washing of hands and tools became mandated routine, this highly communicable disease was spread easily and frequently between a doctor and his weakened female patient, whose vulnerable body was still raw, spent, and bleeding from labor.

Within a few days of giving birth, the woman would begin to feel the first symptoms. What first came on as chills and fever would quickly evolve into a “fierce and consuming” infection, which spread with shocking speed and searing pain throughout the woman’s entire reproductive system. Many times, the women’s bodies could not fight off the infection—severely weakened as they were by pregnancy, breast-feeding, and the aftermath of their long, hard birthing process. It is no wonder the disease earned the harrowing moniker the destroyer of families.

But to Meigs, this dreaded pestilence was an absolute mystery—why did it sometimes kill just one of his patients, while other times, he seemed to be in the middle of an epidemic of it, with mortality rates reaching nearly one hundred percent?

The only thing Meigs was absolutely sure about puerperal fever was that his role as doctor had absolutely nothing to do with it. And in this way, for the duration of his career, Meigs remained willfully blind to the role he played in sentencing the young mothers in his care to death.

But that was about to change, thanks to a bold and enterprising young doctor named Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

• • •

Educated in Boston and Paris, the thirty-four-year-old Holmes was just at the start of his career when he published a controversial paper titled “The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever.”

In it, he convincingly—and seemingly definitively—argued that the deadly infection was most often transmitted to the patient by her own attendants: her doctor, the nurse, or the midwife. He ended the article by advocating the best techniques for preventing the disease’s spread: promote a clean and sterile environment for the birth room; remove and/or methodically clean any clothing, bedding, or fabrics that might transmit the disease between patients; and, of course, thoroughly wash the doctor’s hands, arms, face, and tools.

The article drew much attention to the young doctor and the case he was making. He was praised for “the clarity and forcefulness” with which he addressed “both the transmission and prevention of this devastating disease.”

Strangely, Holmes’s boat-rocking realization came to him by chance. As a member of the Boston Society for Medical Improvement, he had noticed an odd coincidence in one of the society’s meeting reports. After performing an autopsy on a woman who had died of puerperal fever, a Boston-based physician died of the same infection less than a week later, apparently because of a wound he received while performing the autopsy.

As if that weren’t compelling enough evidence, in the interval between being wounded and dying from infection, that same Boston-based physician had served as the obstetrician for several laboring women: Every single one of those women went on to develop puerperal fever.

This inspired Holmes to do further research, and finally write in this paper what he saw as the obvious conclusion, doing so in the plainest language he could: “The disease, known as Puerperal Fever, is so far contagious as to be frequently carried from patient to patient by physicians and nurses.”

It was not a new concept. Holmes cited literature that supported his theory, though these articles were mainly published in British journals. However, the specificity of his evidence made his paper uniquely compelling and condemning. To many, Holmes had made the perfect case—an indisputable one.

But, of course, this did not stop the eminent obstetrician Charles D. Meigs—who was just a few years into his appointment as a chair of obstetrics at Jefferson Medical College—from publicly decrying Holmes’s conclusion. Meigs’s response was particularly horrifying to Holmes, for during the course of his research, he had uncovered a harrowing story that had taken place right in the heart of Philadelphia.

• • •

It had been an oppressively hot summer in the City of Brotherly Love when a particularly vicious outbreak of puerperal fever began to attack the city’s women. It got so bad that the medical community demanded an investigation to determine the possible cause of this seemingly unending epidemic. The research revealed that an overwhelming number of Philadelphia’s puerperal fever cases could be traced back to one doctor: a man by the name of Rutter.

In one three-month period, seventy-seven women whose births were attended by Dr. Rutter contracted the dreaded disease. Fifteen of the women died from it.

After witnessing so many other women under Dr. Rutter’s care fall ill and die, several of Rutter’s patients decided to seek help when they themselves began to show symptoms. And who better to help them but the city’s most renowned obstetrician, Charles D. Meigs?

So Meigs himself was brought in to meet with and consult on several of Dr. Rutter’s puerperal fever cases. Though Meigs was fully aware that Dr. Rutter had “a far greater number of such cases than any other practitioner in Philadelphia,” the esteemed Meigs waved off any notion that Rutter could be responsible, and instead chalked it up to the fact that Rutter managed such a large practice.

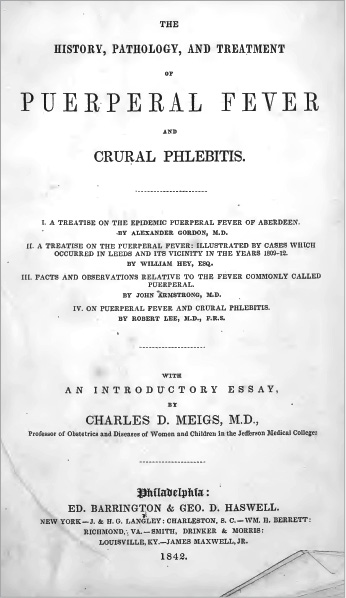

Holmes found Meigs’s failure to recognize the true nature of what was happening especially surprising since Meigs had edited a publication on puerperal fever that included the testimonies of four well-known British obstetricians, all of whom wrote about the possible communicable nature of the disease.

Holmes was outraged that the only conclusion such a lauded professor—the chair of obstetrics at the prestigious Jefferson Medical College no less!—could reach in the face of a “raging epidemic of puerperal fever,” isolated largely among the clientele of a single Philadelphia doctor, was not that perhaps the disease was clearly contagious (and furthermore was being actively spread by the one person who linked all of these suffering women together), but instead that the “grossly epidemic” proportion of victims in Dr. Rutter’s private practice was merely a “coincidence.”

Even after Holmes publicly related this story, Meigs refused to accept the contagious nature of puerperal fever and instead disparagingly attacked Holmes for what Meigs perceived as overly “sharp” criticism of his position on the matter.

Holmes followed this rancorous thrust from Meigs by issuing a terse but damning statement: “I take no offense and attempt no retort. No man makes a quarrel with me over the counterpane that covers a mother with her newborn infant at her breast! There is no epithet in the vocabulary of slight or sarcasm that can reach my personal sensibilities in such a controversy.”

Meigs and Holmes both refused to budge from their positions.

Holmes believed he had clear facts and science on his side, while Meigs felt that his own extensive career in obstetrics was more than enough evidence to back up his long-held opinion. Frustrating to Holmes was that it didn’t seem to be the case that Meigs simply didn’t believe puerperal fever could be contagious; rather, it seemed that Meigs was unable or unwilling to understand the concept that diseases could even be contagious.

“[I prefer] to attribute these cases [of puerperal fever] to accident, or Providence, of which I can form a conception,” Meigs stated, “rather than to a contagion of which I cannot form any clear idea.”

The dispute would continue for more than a decade, and even after Holmes made his clear and compelling case, some in the community still sided with Meigs. Among those who did was Hugh Lenox Hodge, professor of obstetrics at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, who taught in his classroom that the idea of puerperal fever being contagious was pure rubbish, and even went so far as to assure concerned students who wondered if Holmes could be right that they shouldn’t worry, because “as physicians, [they] could never be the minister of evil to convey a horrible virus to their parturient patients.”

The reason there was still such uncertainty in this debate was because it took place in a “premicrobial era”—that is, a time before the existence of microorganisms was definitively proven, thanks to the invention of the modern microscope and the late-nineteenth-century work of Louis Pasteur (whose experiments helped prove germ theory) and future Nobel Prize–winner Robert Koch (who helped established that microbes can cause disease).

Without the undeniable physical proof later generations of scientists would have, Holmes’s article and theory relied almost entirely on deductive logic, looking at the details of the cases to determine that “an unknown contagion existed in the lying-in premises, or was carried to the childbed by an attendant of the mother,” and that the presence of an “unseen, transmissible agent” caused the disease.

(When science finally caught up with Holmes, and late-nineteenth-century microbiologists confirmed the theory he had deduced nearly half a century earlier, Holmes was quoted as saying, more than a little proudly, “I took my ground on the existing evidence before a little army of microbes was marched up to support my position.”)

But Holmes wasn’t alone in his powerful belief in germ theory. At Jefferson Medical College, Mütter and chair of medicine John Kearsley Mitchell were both early proponents of the infectious nature of disease. Mitchell famously lectured that numerous diseases—scarlet fever, consumption, measles, pneumonia, and smallpox, among others—were spread through human contact. Though unable to prove these diseases were related to specific organisms, he would point the finger at “minute spores and fungi.”

In addition to his strict insistence on cleanliness before, during, and after operations, Mütter encouraged his students to view diseases as separate entities, produced by separate organisms. When challenged in class about the popular theory that gonorrhea and syphilis were caused by the same pathogen, Mütter quickly corrected the challenger, emphatically stating, “When gonorrhea and syphilis are produced in a patient at the same time, the respective virus of both have been present. One organism cannot produce the other disease.” At a time when many doctors thought that several diseases were caused by the source (and which of the diseases manifested would be based on a number of different, complicated factors), Mütter’s insistence that all diseases—including and especially their causes—must be viewed separately was incredibly forward thinking.

And by 1855—the same year that Mütter would embark on his final year of teaching at Jefferson Medical College, and twelve years after Holmes published his original paper on puerperal fever—it seemed as if the larger medical community was finally also backing Holmes’s facts over Meigs’s bombast.

In celebration of this clear change of tides, Holmes—now a professor of anatomy and physiology at Harvard University, a post he would hold for thirty-five years—decided to reprint the essay as a stand-alone publication titled Puerperal Fever, as a Private Pestilence. Importantly, even though a dozen years had passed, Holmes reprinted the work without the change of a word or syllable. The passage of time had not dimmed or diminished his findings at all, and in republishing the work, he hoped to gain a wider audience for its lifesaving message.

However, Holmes had never forgotten Dr. Meigs and his withering remarks and haughty denial of the disease’s infectiousness—a truth that Holmes felt the “commonest exercise of reason” should have illuminated.

So, prior to the publication of Puerperal Fever, as a Private Pestilence, Holmes penned a fearlessly audacious introduction, in which he called out Meigs by name more than a dozen times. He detailed and deflated Meigs’s arguments against his theory, and then warned any medical school students of the dangers of believing any professor whose views were so limited and sophomoric.

“If I am wrong, let me be put down by such rebuke as no rash declaimer has received since there has been a public opinion in the medical profession of America,” Holmes boldly declared. “If I am right, let doctrines which lead to professional homicide be no longer taught from the chairs of [Jefferson Medical College and the University of Pennsylvania]. . . .

“Let the men who mould opinions look to it; if there is any voluntary blindness, any interested oversight, any culpable negligence, even, in such a matter, and the fact shall reach the public ear,” he concluded, with a statement that would cement Meigs’s spectacular fall from power and grace, “the pestilence-carrier of the lying-in chamber must look to God for pardon, for man will never forgive him.”

Meigs never commented on the publication, and would go to the grave without ever admitting that his beliefs on the matter—which he had loudly, persistently espoused for decades—had been utterly and completely wrong.