Even in the middle of the ocean, Mütter could not get her out of his mind. He excused himself early from dinner, stopped well-meaning conversationalists mid-sentence, and rushed down to his sleeping quarters just to hold her face in his hands.

To an American like him, she appeared unquestionably French: high cheekbones, full upturned lips, glittering deep-set eyes. For an older woman, she was impressively well preserved, her temples kissed with only the slightest crush of wrinkles. When she was young, Mütter imagined, she must have been very beautiful, though perhaps girlishly sensitive about the long thin hook of her nose, or the pale mole resting on her lower left cheek. But that would have been decades ago.

Now well past her childbearing years, the woman answered only to “Madame Dimanche”—the Widow Sunday—and all anyone saw when they looked at her was the thick brown horn that sprouted from her pale forehead, continuing down the entire length of her face and stopping bluntly just below her pointy, perfect French chin.

• • •

The young Dr. Thomas Dent Mutter had arrived in Paris less than a year earlier, in the fall of 1831. Even for Mutter, who had always relied heavily on his ability to charm a situation to his favor, it had not been an easy trip to arrange.

He was just twenty years old when he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania’s storied medical college. To an outsider, he may not have seemed that different from the other students in his class: fresh-faced, eager, hardworking. But he knew he was different—in some ways that were deliberate and in other ways that were utterly out of his control.

Perhaps the most obvious of these was Mutter’s appearance. He was, as anyone could plainly see, extraordinarily handsome. Having studied his parents’ portraits as a child—one of the few things of theirs he still possessed—he knew that he inherited his good looks. He had his father’s strong nose, impishly arched eyebrows, and rare bright blue eyes. He favored his mother’s bright complexion, her round lips, and sweet, open oval face. His chin, like hers, jutted out playfully.

Mutter made sure to keep his thick brown hair cut to a fashionable length, brushed back and swept off his cleanly shaven, charismatic face. His clothing was always clean, current, and fastidiously tailored. From a young age, he understood how important looks were, how vital appearance was to acceptance, especially among certain circles of society. He worked hard to create an aura of ease around him. No one needed to know how much he had struggled, or how much he struggled still. No, rather he made it a habit to stand straight, to make his smile easy and his laugh warm. He was, as a contemporary once described him, the absolute pink of neatness.

The truth was that, financially, he had always been forced to walk a tightrope. Both his parents had died when he was very young. The money they left him was modest, and thanks to complicated legal issues, his access to it was severely limited. Over the years, he grew practiced in the art of finessing opportunities so that he could live something approximate to the life he desired. At boarding school, he was known to charge his clothing bills to the institution and then earn scholarships to pay off the resulting debts. When he wanted to travel, he secured just enough money to get him to his destination and then relied on his wits to get him back home.

And now that Mutter had achieved his longtime goal of graduating from one of the country’s best medical schools, he focused on his next goal: Paris.

Paris was the epicenter of medical achievement: the medical mecca. Hundreds of American doctors swarmed to the city every year, knowing that in order to be great, to be truly great, you must study medicine in Paris. And that had always been Mutter’s plan: to be great. More than that: to be the greatest.

• • •

Getting to Paris, however, was not an easy endeavor. He knew—as all gentlemen of limited means did—that sailing as a surgeon’s mate with a U.S. naval ship in exchange for free passage to Europe was an option open to him, but competition was always considerable and fierce. Mutter spent months submitting letters and applications to the secretary of the Navy, trying to use charm, logic, and bravado to secure a position. He even implored his guardian, Colonel Robert W. Carter, to ask prominent men close to President Jackson to write letters on his behalf, explaining, “[I] am afraid that I shall not be able to obtain an order unless I can get my friends to make some exertions for the furtherance of my plan.” Despite all the effort he expended, no position ever materialized.

Mutter could only watch as the wealthier members of his graduating class departed for Europe with financial ease. Others returned to their hometowns with their new degrees, bought houses with their fathers’ money, and started their practices using their families’ connections. Mutter remained in Philadelphia, and his hopes remained fixed on Paris.

Mutter felt his luck about to change when he read about the Kensington in a local Philadelphia paper. For months, the Cramp shipyard had been building a massive warship. The rumor was that it was being built for the Mexican Navy, and that upon seeing its immense size—and cost—they opted to back out of purchasing it. However, the most recent update was that the giant ship had sold after all, to the Imperial Russian Navy.

Mutter saw an opportunity. He went to the Cramp shipyard and asked if the American crew in charge of sailing the Kensington to Russia was in need of a surgeon’s mate. That he was just twenty and only a few months out of medical school was a minor detail. He hoped that being present, able, and willing would be enough. Luckily for Mutter, it was. A few weeks later, he boarded the ship (later to be renamed the Prince of Warsaw by Tsar Nicholas himself), and left America for the first time.

• • •

The ocean was like nothing Mutter had ever experienced: vast and wild and so incredibly loud. He had hoped the enormity of the newly built warship—with its four towering masts and immense spiderweb of rigging—as well as its extensively trained crew would offer him comfort during the weeks at sea, but the experience was more taxing than any book or anecdote portended.

He did not anticipate that whether he was holed up in the bowels of the ship or clinging to the aft railing, his body would be trapped in a relentless cycle of emptying itself. That his stomach would never become accustomed to the rolling blue-black swells of the sea. Nor did he realize how intimate he would become with the ship’s beastly stowaways—bedbugs and fleas, weevils and rats. He would wake to bugs crawling in his hair and mouth, and fall asleep to sounds of the rats chewing through his clothes, attempting to suss out even the smallest morsel of food. And then there were the storms, the nights when he felt certain the vessel would break in two as mountainous waves crashed over it, the ship itself painfully groaning with each hit. The ocean seemed nothing but a frothing black maw, hungry to devour him.

When the sea was calm and the sky bright and blue, he forced himself to stand on the ship’s deck and look toward what he hoped was Europe. He tried to enjoy these moments, but he didn’t know true relief until the crew pointed out birds appearing in the sky, a sign that they were approaching land, after more than a month at sea.

• • •

When Mutter finally arrived in Paris, it immediately reminded him of the ocean; it too was vast and wild and incredibly loud. Unlike at sea, however, in Paris he felt perfectly at home.

Its streets were packed, people and buildings in every direction. His world was suddenly and delightfully filled with new sounds, new scents, new music. There were colorfully dressed women sweeping the streets, and strapping men carrying enormous bundles on their heads. There were strange-looking carriages that seemed like relics of a barbarous age, which were in turn being pulled by enormous and brash horses. Even the food being eaten at street-side cafes seemed strange and exotic to Mutter. The city avenue was a vast museum of wonderful new sights to gawk at, and it seemed that the French wanted it that way. They loved to look, and to be looked at. It was true what Mutter had heard: Those French who could spare the time would flamboyantly promenade every day. And on Sundays, absolutely everyone did.

Once Mutter had secured modest student housing, he set out to promenade himself. He’d been sure to pack his finest clothes for the journey: suits cut close to his slim frame (his natural thinness being perhaps one of the only benefits he’d gained from the illnesses that had plagued him since childhood) and made from the most expensive fabrics he could afford in the brightest colors in stock. Years earlier, a schoolmaster once wrote to Colonel Carter, Mutter’s guardian, that his pupil’s “principal error is rather too much fondness for a style of dress not altogether proper for a boy his age.” Clearly, that schoolmaster had never been to Paris.

Mutter enjoyed the moment, peacocking on Parisian streets for the first time, a master of his fate. The lines between Mutter’s starting points and his destination were not often straight, but he took pride and comfort in knowing that he always got there. And the next morning, he would begin the next phase of his mission, his true goal in Paris: to learn everything he could about modern medicine until his money, or his luck, ran out.

• • •

In 1831, over a half million people called Paris their home, and by royal decree, each French citizen was entitled to free medical treatment from any of the dozens of hospitals within the city limits. The hospitals were typically open to any visiting doctors, provided one could show them a medical degree and, when necessary, place the right amount of coins into the right hands.

Studying medicine in Paris became so popular that guidebooks were written just for the visiting American doctors. Nowhere else in the world, one wrote, could “experience be acquired by the attentive student as in the French capital . . . where exists such a vast and inexhaustible field for observation . . .”

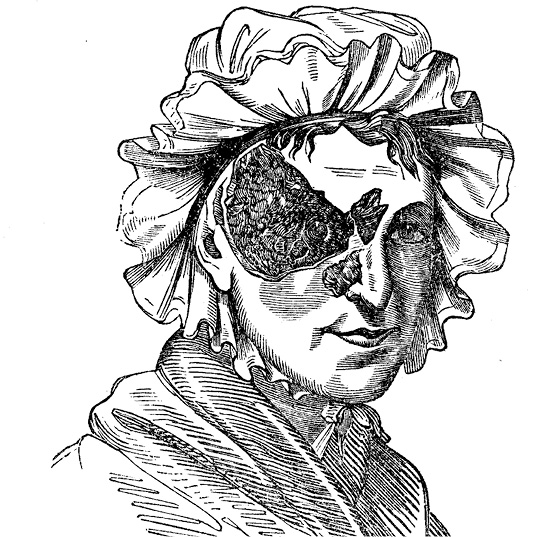

Woman with Ulcer of the Face

And it was true. Where else but Paris would there be not one but two hospitals devoted entirely to the treatment of syphilis? Afflicted women were sent to the Hôpital Lourcine, a hospital filled with the most frightful instances of venereal ravages. The men were sent to the Hôpital du Midi, which required that all patients be publicly whipped as punishment for contracting the disease, both before and after treatment.

Hôpital des Enfants-Malades was a hospital for ill children, and was nearly always filled to capacity. It had a grim mortality rate—one in every four children who came for treatment died there—but the doctors on staff assured visiting scholars that this was because most of the patients came from the lowest classes of society and thus were frequently brought to the hospital already in a hopeless or dying condition.

Doctors specializing in obstetrics could visit Hôpital de la Maternité. It served laboring women only, and averaged eleven births a day. Some days, however, the numbers rose to twenty-five or thirty women, each wailing in her own bed, as the doctors and midwives (called sages-femmes) rushed among them. New mothers were allowed to stay nine days after giving birth, and the hospital even supplied them with clothing and a small allowance, provided they were willing to take the child with them. Not all of the women were.

So the Hôpital des Enfants-Trouvés for abandoned children was founded. Newborns arrived daily from Hôpital de la Maternité from women unable or unwilling to keep their children, as well as those infants whose mothers died while giving birth, as one in every fifty women who entered Hôpital de la Maternité did.

The Hôpital des Enfants-Trouvés also allowed Parisian citizens to come directly to the hospital and hand over a child of any age. The hospital encouraged families to register and mark the children they were leaving so they might reclaim them at a later date, but the families who chose to do so were few. In fact, the vast majority of the children there had arrived via le tour.

Le tour d’abandon (“the desertion tower”) was merely a box attached to the hospital, constructed with two sliding doors and a small, loud bell. An infant was unceremoniously placed in the box, the door firmly closed behind it, and the bell was rung. Upon hearing the bell, the nurses on duty would go to le tour to remove the infant, replace the box to its original position, and wait. Every night, a dozen or so infants were received in precisely this way.

For a while, it had been in vogue for wealthy, childless individuals to adopt children from the Hôpital des Enfants-Trouvés to bring up as their own, but the practice had long since fallen out of fashion. At the time of Mutter’s visit, more than sixteen thousand children were considered wards of the Hôpital des Enfants-Trouvés, and of those, only twelve thousand would live to adulthood.

There were hospitals for lunatic women and for idiot men, hospitals for the incurable, for the blind, for the deaf and dumb, and even for ailing elderly married couples who wished to die together—they could stay in the same large room provided that the furniture they used to furnish their room became the property of the hospice upon their deaths.

And perhaps most astonishing to the visiting American doctors, Paris had the École Pratique d’Anatomie, which provided any doctor, for six dollars, access to his own cadaver for dissection. In America, cadaver dissection was largely illegal. Many doctors resorted to grave robbing to have the opportunity to examine the human body fully. In Paris, twenty doctors at a time would whittle a human body down to its bones—provided they could stand the smell and the ultimate method of disposal of the dissected corpses: At day’s end, the decimated remains were fed to a pack of snarling dogs kept tied up in the back.

However, more than any single hospital, what most attracted Mutter to Paris were the surgeons: brilliant and daring men who were to him living gods, redefining medicine and at the zenith of their renown.

• • •

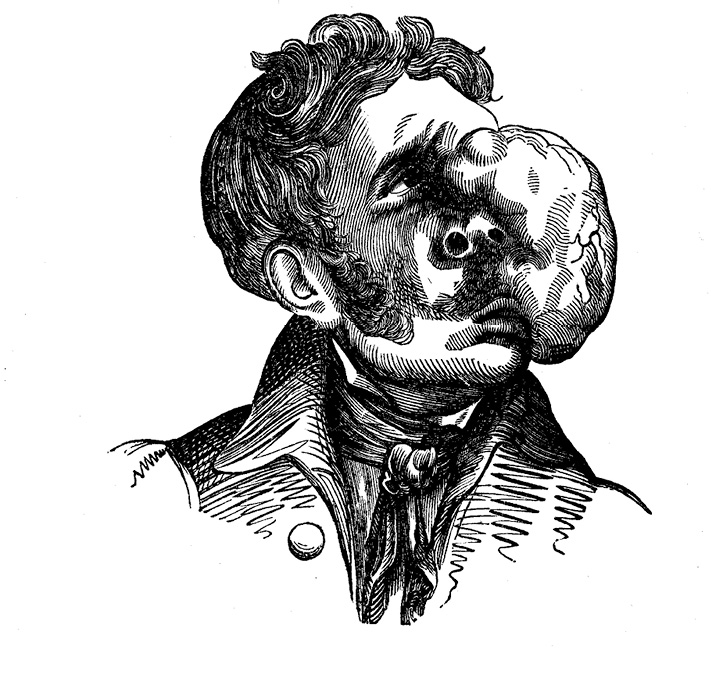

Mutter had always loved surgical lectures and made sure he secured seats as close to the front as possible. In Philadelphia, there were two great medical colleges—the University of Pennsylvania and Jefferson Medical College—and it was customary for the rival schools to hold surgical demonstrations so that prospective students could choose between them, a glorified public relations exercise. Mutter loved the daringness of the surgeries attempted during this time. The lectures were often packed, as eager established and prospective doctors thrilled at the city’s best surgeons attempting to outdo one another with their skill and showmanship. However, the combination of ambitious surgeries and unprepared young men sometimes proved disastrous. On one occasion, a Jefferson Medical College professor attempted a daring removal of a patient’s upper jaw, using marvelous speed to incise the face and rip out the bones with a huge forceps. But the surgery was perhaps too much for a public display. Doctors who were present would later recall the spectacle of it, how the partially conscious patient spat out blood, bones, and teeth, while unnerved students in the audience vomited and fainted in their seats.

But regardless of how brutal or simple the case, all surgical lectures were a challenge to watch. The anxious patient would be publicly examined and forced to listen to his surgery loudly outlined to an audience of strangers. Next, the patient would nervously drink some wine with the hope that it would dull the nerves and lessen the pain. (In Paris, the need for medicinal wine was so great, the hospital system maintained its very own wine vaults, spending more than 600,000 francs a year on an extensive collection of red and white wine housed exclusively for its patients.)

The patient was then instructed to lie on the surgical table, where he would be held down by the surgeon’s assistants and told to stay as still as possible. Everyone—the patient, the doctor, even the students in their seats—knew how impossible this command would be to follow.

The first incision usually brought the patient’s first scream—the first scream of many. Soon came the blood, the struggle, the shock. The patient would beg the surgeon to stop, plead and shout, and yell to the students to come save him, his voice cracking, tears streaming down his face. The surgeon was expected to ignore it all, to move forward swiftly and surely, and to hope that his assistants were strong men with equal resolve. Every student had heard stories of patients who were able to struggle free, who leapt off the table and attacked their doctors—often with the surgeon’s own instruments!—before running out of the room, leaving a trail of their own blood behind them.

Man with Tumor of the Jaw

To Mutter, ignoring the patient was one of the most difficult parts of surgery. He struggled to develop the ability to temporarily see past the patient’s pain—their wide and desperate eyes—and focus solely on his goals as the surgeon.

It had always been explained to him that the most important quality of a good surgeon is confidence, born of both education and experience. You needed to know you were right and that your actions were right, regardless of what was happening around you. Mutter understood this, but in the moment, it was often still a difficult instruction to follow.

Of course, in spite of the skill and care of the surgeon, the patients often died. Sometimes they died in the middle of surgery, the trauma to their bodies becoming too much. Sometimes they would die after, because their wounds were unable to stop bleeding, or the unwashed tools of their own surgeon had given them a fevered infection that consumed their flesh from the inside out. Under the best circumstances, the patient not only lived but lived a better life.

And it was this opportunity to improve a life that caused Mutter to be deeply attracted to studying surgery. Having spent so much time as a patient when he was a child—being bled by lancet or by leech, fed tinctures and bitter weeds, left to sweat it out alone in his bed or soaked in a special bath—he was perhaps too familiar with other, nonsurgical branches of medicine, where recovery was often a guessing game. Sometimes, the relief would be almost immediate once treatment had begun, but more often, the results were undefined, his chest rattling for weeks, his body left to grow gray and thin.

Surgery, however, was not a guessing game; it was an art. People came in need of relief, and the surgeons used every ounce of their skill and knowledge to provide it.

• • •

There was one more reason Mutter revered surgery above all other medical pursuits. Surgeons, unlike other professionals of the medical field, were successes of their own creation. While other doctors found their patients—and their positions in society—based on the family they were lucky enough to be born into, surgeons earned their place through hard work, study, and skill. In fact, it seemed to Mutter that the best surgeons came from the lower or middle classes. It was a “natural consequence of this state of things,” one doctor from the era wrote, seeing that “very few persons entitled by birth or other advantageous circumstances . . . would condescend to study, much less engage in the practice of medicine,” thus “poor and ambitious young men from the provinces were induced to repair to Paris and enter upon the study of the only profession through which they could expect to obtain distinction and worldly prosperity.”

It was well known that several of the best-respected surgeons and physicians in France had risen from the lowest castes of life and many from the uttermost depths of poverty. Even the acclaimed chief surgeon of Hôtel Dieu, Guillaume Dupuytren, who was often referred to as the Emperor of Surgery, had been born poor and had struggled. Furthermore, he was not ashamed of it, but rather credited his background with his success, telling his students that “had not Monsieur Dupuytren been compelled from poverty to trim his student’s lamp with oil from the dissecting-room, he never would have succeeded in becoming Monsieur le Baron Dupuytren.”

• • •

Mutter knew that surgery was his calling, and raced through the streets of Paris to study the work of its greatest practitioners. He was aggressive in his pursuits, pushing through crowds to secure the best seats at the surgical lectures, or firmly staying as close as possible to the lecturing doctors as they made their rounds in hospital, no matter how much the other students pushed. Meals of spiced mutton and fresh bread went half-finished as he plotted the next week’s schedule. Bowls of café au lait were abandoned so he could make an early start every morning, eager to begin his day.

He had come to Paris assuming it would be the doctors themselves who would have the greatest influence on him, these men who were legends in their own time. Chief among them was Guillaume Dupuytren, who ruled over the Hôtel-Dieu, the city’s largest hospital, and single-handedly changed how surgery was done. An immensely brilliant operator, exhibiting marvelous dexterity, proceeding with almost inconceivable speed, his boorish arrogance became as famous as his accomplishments in the surgical room. Jacques Lisfranc de St. Martin was head of the Hôpital de la Pitié, the city’s second-largest hospital. He was Dupuytren’s greatest friend turned into his most bitter rival, and spent most of his life trying to escape Dupuytren’s shadow. Lisfranc was known to refer to Dupuytren as “the bandit of the river bank,” while Dupuytren frequently called Lisfranc “that man with the face of an ape and the heart of a crouching dog.” There was Philibert Joseph Roux—who so dazzled his classes with his graceful and brilliant work that it was said “his operations were the poetry of surgery,” but who had also earned Dupuytren’s scorn years earlier by winning the hand of the woman they both loved. And Alfred-Armand-Louis-Marie Velpeau, whose textbook on obstetrics was so influential, it had been translated into English by one of America’s most respected obstetricians: Philadelphia’s own Charles D. Meigs.

Mutter was deeply impressed with the audacity of each of these surgeons’ talents and their seemingly inexhaustible work ethic. However, it was not any single man who ended up changing the course of Mutter’s life but, rather, a new field of surgery freshly emerging in Paris, which even the French referred to as la chirurgie radicale.

Who sought out this radical surgery?

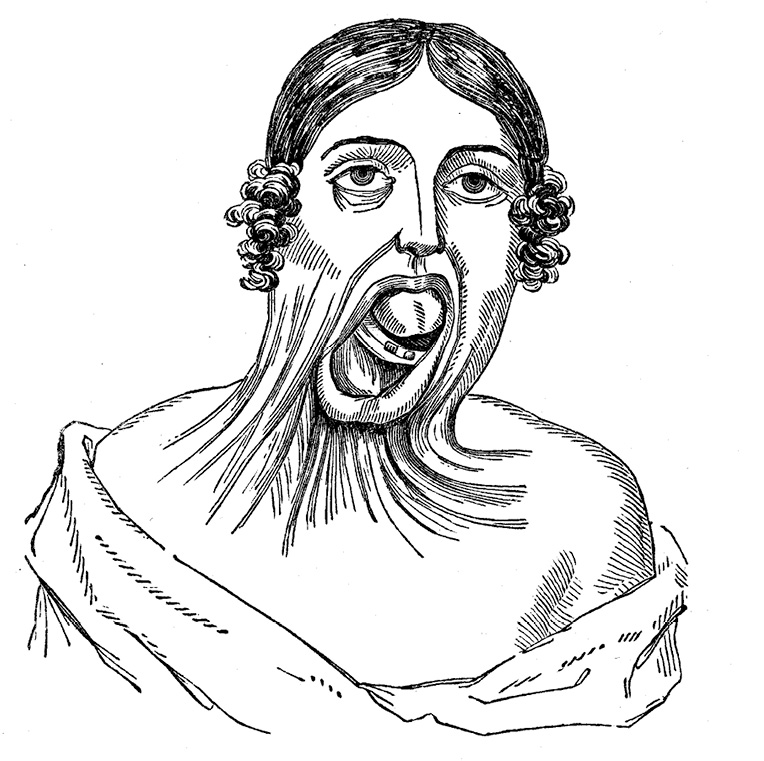

Woman with Severe Burns of the Face

Monsters. This is how the patients would have been categorized in America. Mutter was used to seeing them replicated in wax for classroom display, or hidden in back rooms away from the public eye. He had seen them in jars, fetuses expelled from their mothers, irreparably damaged. MONSTER, the label would read.

Some of these monsters were born that way: a cleft palate so severe the face looked to have been split in two with an ax. Hardly able to eat or drink, spit collected in pools on the child’s clothing as his tongue lolled around the open hole of his mouth, awkward and exposed.

Others were born “normal,” but their bodies would slowly turn them into monsters, as tumors laid siege to their torsos or limbs, swelling their legs like soaked wood, their eyes strained and nearly popping.

Other times, the monsters were man-made: men whose noses were cut off in battle, or as punishment, or for revenge, the centers of their faces evolving into a large weeping sore; women whose dresses caught fire, becoming houses of flames from which their owners couldn’t escape, the skin on their faces turned into melted wax, their mouths permanently frozen in screams.

Monsters. This is what they were called, and this was how they were treated. For such tortured people, death was often seen as a blessing.

In Paris, however, the surgeons had a solution. They called it les opérations plastiques.

Was it quackery? Mutter wondered when he first heard about it. Was it a trick? Would these unfortunates be presented like a sideshow? Were the doctors in the audience there to learn or to gape? What could surgeons possibly do to help such hopeless cases?

At the very first lecture, Mutter began to understand the difference between regular surgery and les opérations plastiques.

The patient, often greeted with gasps of horror and pity, stood stock-still and unafraid as the surgeon made his examination. These regrettables didn’t show the unease normal patients did; their eyes didn’t wander back to the door from which they entered and through which they could also escape. Gradually, Mutter grew to understand why.

In regular surgical lectures, patients rarely understood the trouble they were in. When the knife first pierced the skin, they could come to the sudden realization that a life without this surgery might still be a happy one. Thus, escape was the best possible solution and a choice they wanted to exercise right away.

Patients of les opérations plastiques, however, were often too aware of their lot in life: that of a monster. It was inescapable. They hid their faces when walking down the street. They took cover in back rooms, excused themselves when there were knocks at the door. They saw how children howled at the sight of them. They understood the half a life they were condemned to live and the envy they couldn’t help but feel toward others—whole people who didn’t realize how lucky they were to wear the label HUMAN.

It was not uncommon for these patients to enter the surgical room fully prepared to die. Death was a risk they happily took for the chance to bring some level of peace and normality to their mangled faces or agonized bodies. The surgeries weren’t physically necessary to save their lives; rather, they were done so the patient might have the gift of living a better, normal life. That is what les opérations plastiques promised.

Plastique was a French adjective that translated to “easily shaped or molded.” That was the hope with this surgery: to reconstruct or repair parts of the body by primarily using materials from the patient’s own body, such as tissue, skin, or bone.

The surgeries, of course, were not always successful—if a patient’s problem had been so easy to fix, it would have been corrected by lesser doctors years ago. But other times—and these were the times the audience waited for, the ones that made Mutter’s hair stand on edge—the end result was nothing short of miraculous.

With a careful hand, a steady knife, and a piece of bone, a surgeon could reconstruct a man’s nose with a twisted portion of his own forehead. A burned woman’s eye could close for the first time in ten years, thanks to a surgeon’s knife cutting the binding scar tissue and replacing it with skin from her own cheek. Cleft palates were fused back together—trickier than it might seem, for the sensitivities when working on the roof of the mouth meant the patient was in constant threat of vomiting, which would tear open delicate sutures and ensure infection.

Mutter seized every opportunity to witness these plastic operations firsthand. He used his charms to become an interne at the hospital to which Dupuytren was attached so he could watch the great master at work. But he didn’t limit his focus to Dupuytren, and soon became so familiar with each surgeon—their style and flourishes, their weaknesses and strengths—that he began to view them as his friends, even though they never shared a single word. He took copious notes, drew detailed diagrams, and bought every relevant book he could find and afford. It became his happy obsession.

Mutter hadn’t been in Paris even a year when he realized his time was running out. His limited funds were being swiftly exhausted, and he still needed to fund his trip back home. His newly made friends in the Parisian medical society tried to dissuade him. They adored the dashing young doctor with the “quick, active, appropriative mind . . . readily imbued with the spirit of his distinguished [Parisian] teachers.” They implored him to stay, pointing out how much work a charming American doctor could get in a bustling city full of English-speaking tourists.

Mutter loved his time in Paris, but his desire to return to Philadelphia was even stronger. He was twenty-one years old and felt healthier than he ever had in his entire life. He felt like a new man. He had even given himself a new name. He was no longer Thom D. Mutter from Virginia.

He had reinvented himself as Thomas Dent Mütter—with a perfectly European umlaut over the u.

With the last of his money, he purchased a wax model from a shop that specialized in reproductions for doctors. It was the face of Madame Dimanche, the French washerwoman who grew a large, brown horn from the center of her forehead. At first, the old woman hadn’t known what to make of the strange brown nub that appeared like an ashy smudge in the center of her head, but she knew to hide it from view, starting a decade-long habit of avoiding eye contact. But the nub grew relentlessly, larger and larger, until it was as thick and dark as a tree branch.

When she finally allowed it to be examined, she followed a chain of doctors that ended with a surgeon who told her he could remove it if she would trust him. She did. And so it happened the surgeon—practiced in this new art of les opérations plastiques—who promised her relief was able to actually deliver it. How happy she was to walk down the streets, her head unhidden. How thrilling it was to feel the wind kiss her bare face.

Mütter purchased a replica of Madame Dimanche’s presurgery face, her long, thick horn still intact. And on the long journey back to America, he took it out often, the sea bucking the boat beneath him. He took out her face and stared into it. In it, he saw his future.