The following selections are about the two Yemens during the 1970s and ’80s, a period defined internationally by the Cold War and within the Peninsula by the great wealth that accrued to the monarchies during the “oil boom.”

Historically labeled on European maps as “Arabia Felix” (Happy Arabia) for its verdant farmlands, by the middle of the twentieth century Yemen was anything but. It remained by far the most populous and densely populated part of the Peninsula, and Aden was still its most important seaport, drawing traders and immigrants from the Indian Ocean and beyond. Yet, or therefore, it was also the most unstable. Moreover, in a terrain of striking ecological variation, there were strong local and regional identities, with stark contrasts between towering highlands and the coasts, areas washed by monsoons and semi-arid regions, the colony and the hinterland.

The 1960s were a decade of rapid, profound changes. Secular officers unseated a 1000-year-old Zaydi Imamate in the North in 1962; in 1967 South Yemen declared its independence after over a century of British imperial rule. The upheavals left the southwest quadrant of Arabia as a Cold War fault line, and simultaneously as the increasingly impoverished corner of an otherwise prosperous Peninsula.

Between roughly 1969 and 1989, two unstable regimes each failed to establish viable states. The following selections offer some vivid glimpses into lived experiences in different cities, villages and social classes as well as analysis of the differences, similarities and convoluted interactions between the governments based in Sana‘a and Aden, respectively. Between the effects of the oil boom in neighboring counties, the geo-strategic reverberations of the Cold War and bad domestic governance, Arabia Felix became the conflict-ridden periphery of the GCC.

We first meet President ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih, whose long rule prompted the 2011 uprising, in Fred Halliday’s account of his observations and interviews in 1984 in Sana‘a and Ta‘iz in 1984. The second piece is Halliday’s reaction to the implosion of the Aden regime in 1986. A couple of years later Cynthia Myntti and I compared my notes on family life from the old city of Sana‘a with hers from a farming village between Ta‘iz and Aden. Note, in light of the sectarian rhetoric and violence in 2015, that none of us thought to mention that Sana‘a was predominantly Zaydi whereas both Ta‘iz and the people in the southern regions were Shafi’i. We noted piety but not denominational differences, which seemed utterly irrelevant; we analyzed hard power and economic forces buffeting both politics and everyday life. The South was called Socialist, although my analysis in the final selection notes more similarities than differences between the “socialism” of the People’s Democratic Republic and the “no doors” policies of the Sana‘a regime: Both underdeveloped economies were dependent on the vicissitudes of foreign aid and workers’ remittances. Halliday and I each indicate negotiations over unification, which happened years later, just as the Cold War ended.

The ethnographic observations, economic factors and regional variations in the years leading up to the unity agreement of 1990 also help explain the 1994 civil war and provide geographic perspective and political antecedents to the events of 2011–15.

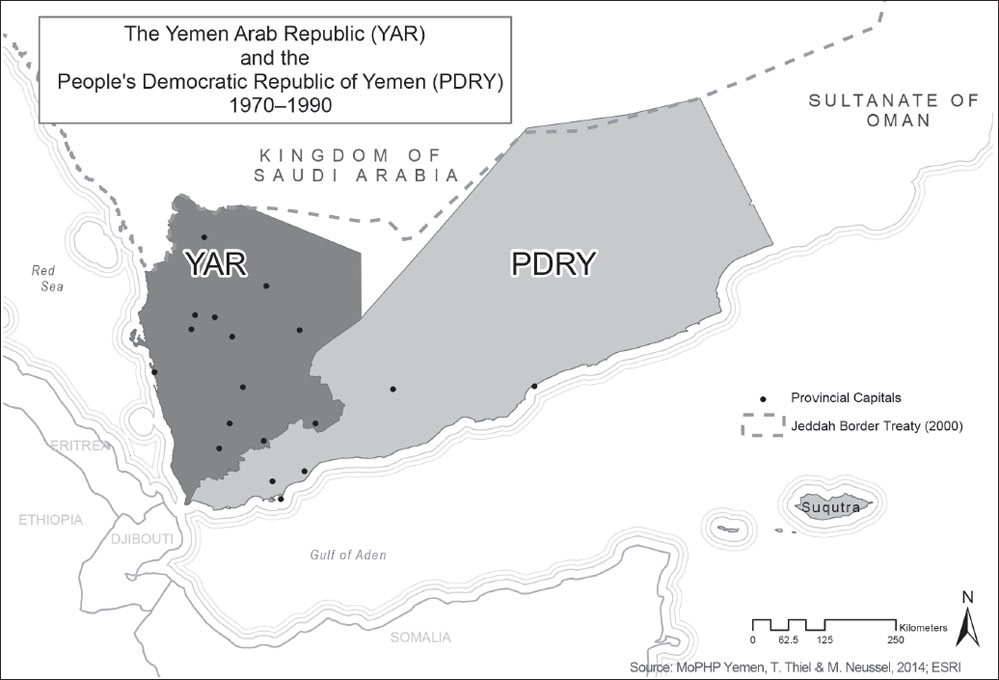

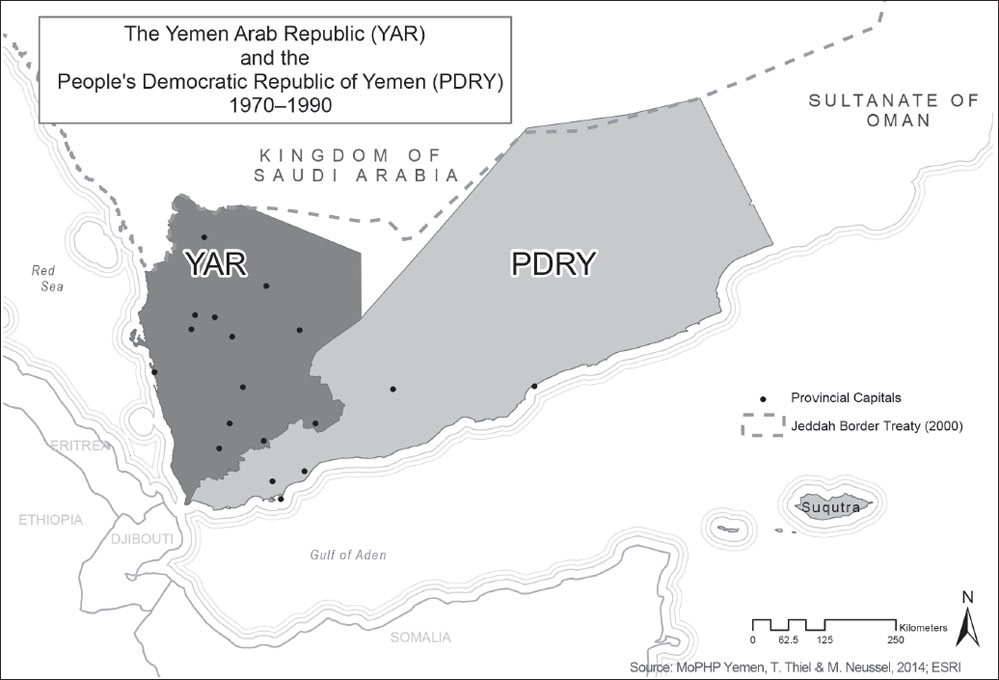

Map 2: The Yemen Arab Republic and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen. (1970–90)

Produced by the Spatial Analysis Lab, University of Richmond

The streets of Sana‘a, the North Yemeni capital, appear to condense some of the most divergent elements of Third World economic change and political upheaval. Perhaps nowhere else in the Middle East, or indeed elsewhere in the Third World, do the antinomies of combined and uneven development come so dramatically to the surface. The city is full of consumer goods brought in on the emigrants’ remittances and foreign aid that make up nearly all of the country’s foreign exchange earnings. Filipino workers in hardhats are digging up the roads to install sewerage systems. Aid agencies of many stripes are plying their wares and plans. Most men of commerce are indigenous to North Yemen, but their ranks are swollen by thousands of compatriots who have come from the People’s Democratic Republic in the south to escape state control, or from sections of the Yemeni diaspora in Ethiopia, Kenya, Vietnam or Britain. They push their goods onto the streets and sit on the floor inside their shops, chewing qat [a mildly narcotic leaf].

Commercial capitalism is alive and well, at least as long as the monies from abroad pour in. For a country whose exports come to only 1 percent of its imports, the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) is doing well indeed. The politics of the city are also vigorously displayed. Much in Sana‘a is reminiscent of the period when Gamal Abdel Nasser dispatched Egyptian forces in the 1960s to save the new republic from the Saudi- and British-backed royalist rebels. The policemen direct traffic in Egyptian-style white uniforms. The slogans on the banners across the streets proclaim the YAR’s loyalty to Arab unity in tones of Nasserist enthusiasm now unheard in their country of origin. The majority of the 23,000 schoolteachers in the country are from Egypt, and these gallabiyya-clad men are numerous in the markets and squares of Sana‘a and other cities.

Ta‘iz, the southern city, has a more drab, nondescript character, and its idiom is littered with the traces of Adeni vocabulary derived from the days of British rule. Sana‘a, by contrast, retains much of its historic character: The old city remains as it was many hundreds of years ago, a spectacularly beautiful collection of stone houses with white lime wash patterns, little walled gardens, narrow streets and white minarets. It is probably the most architecturally alluring and unified city of the whole Islamic world. Most men wear the fouta, or kilt. In the afternoon, the whole city slows down considerably for the chewing of qat: This practice is limited to Thursday afternoons and Fridays in the PDRY, but no constraints apply in the more riotous north. Here, as in the south, the stimulations of alcohol have now been added.

Sana‘a is not North Yemen. The contrast between city and countryside, one that lay at the heart of the civil war in the 1960s, and which Sana‘a experienced dramatically during the siege of 1967–68, when it was saved only by a massive Soviet airlift, is still there. The majority of the country remains rural, and farming still accounts for some 85 percent of the labor force. The peasantry is dominated by tribal loyalties and is deeply suspicious of any government at the center. Adult illiteracy is extremely high—over 80 percent—and less than 40 percent of children are in school. Rural health schemes are slight. Many warn visitors against traveling outside the cities at night.

On the Chinese-built road north of Sana‘a that runs to the spectacular mountain fortress town of Hajjah, where the imam kept his opponents in dungeons, it does not take long to run into roadside vendors selling fruit, smuggled in from Saudi Arabia to circumvent a ban imposed in October 1983 to cut foreign exchange loss. On the road south from Sana‘a, past a landscape of water towers (nuba) and hillside terraces, there were eight marakiz al-taftish (roadblocks [or checkpoints]), designed both to find smugglers and their wares and to check vehicles for arms belonging to the underground National Democratic Front. (One’s bags and books are also carefully scrutinized at the airport.) The war of the 1960s and the influx of emigrants’ monies in the 1970s have not decisively weakened tribal loyalties in the countryside: They have, rather, provided new ways in which people can amass local power, bending and adapting the traditional forms of control to take advantage of the new, plentiful supplies of guns and money. For a little while now, the government has banned tribesmen from bringing arms into the largest cities. But outside Sana‘a and Ta‘iz most men carry them, and the government’s ability to control these areas directly remains limited. Such control as exists is mediated by tribal chiefs. The Saudis still give subsidies to the northern tribes, an estimated $60 to $80 million each year.

The city to which Sana‘a bears greatest resemblance is Kabul. There is the same smell of eucalyptus trees, the same sense of altitude and dust, of harsh sunlight on the sharp bare mountains around the town, of hooting cars, of an atypical, often beleaguered urban setting threatened by a counterrevolutionary, tribal world beyond. There are times in North Yemen when one wonders how the republic ever survived the onslaughts of the 1960s. Nor does the comparison with Kabul end there, for in the main square of the city, the Midan al-Tahrir, named after its Egyptian counterpart and stretching away from the former palace of the imams, there stands, as in Kabul, a Soviet-built T-34 tank, on a pedestal, with a little garden and an “eternal flame.” The tank in Kabul reportedly had burst into what was the palace of President Daud in April 1978, beginning the Great Saur Revolution; the one in Sana‘a was used to attack the imam’s palace on the night of September 26, 1962.

Despite all its conservatism and social confusion, the YAR remains a country that has gone through a revolution. The old political order was destroyed: The imam lives in exile in Kent, England, and his many relatives are in Saudi Arabia. The old ruling caste of sada [the plural of sayyid], who controlled much of the state and judicial processes in the pre-1962 period, and who presented themselves as direct descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, no longer hold power as a social group. Some, as individuals, are influential in the affairs of state, and others can be seen still walking the streets, with their jambiyas (daggers) in the sayyid position—in the middle, instead of on one side of their belts. But the monarchy and its associated caste have been destroyed. With this, North Yemen was wrenched into the capitalist market over the past two decades with a vengeance.

The legitimacy of the revolution is important in the regime of President ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih. The slogans around Sana‘a proclaim his loyalty to the “glorious September 26 revolution.” Television programs for children show the old days of the imam’s tyranny, and then picture the coming of the revolution, the expansion of education and establishment of justice. The imam’s palaces, where Imam Yahya, under the influence of morphine, would play with his imported toys and a slave would crank up the lift with a winch, are now museums of the revolution or hotels. The main street in Sana‘a is named after one of the organizers of the 1962 revolution, a man who died in the first days, ‘Abd al-Mughni. The three main streets in Ta‘iz are called September 26, Gamal Abdel Nasser and Liberation.

This proclamation of a revolutionary ideology has recently taken a new twist in the process of collaboration and rivalry with the South. Just as in the PDRY, where President ‘Ali Nasir Muhammad has three titles, dutifully repeated after every mention of his name (secretary-general of the party, chairman of the council of ministers, president of the Supreme People’s Council), so in the YAR, ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih has acquired his ritual triplet—the brother president of the republic, commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and secretary of the General People’s Congress, the 1,000-strong body equivalent of a government party.

In the competition for revolutionary legitimacy and loyalty to the values of Arab and Yemeni nationalism combined, ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih leaves little to chance. His picture is everywhere. Yet a less likely champion of revolutionary and nationalist values could hardly be found. ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih, born in 1943 of a minor sheikhly family in Sanhan, south of Sana‘a, served as an artillery officer in the armed forces, and won his reputation fighting the left-wing opposition in the 1970s. In 1977, when the Saudis and their tribal allies accused President Ibrahim al-Hamdi of increasing relations with the South much too rapidly and overtly, ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih was widely credited with personally having slain al-Hamdi. With the death in 1978 of al-Hamdi’s successor, the conservative Ahmad al-Ghashmi, Salih became president. Few people here or outside the country expected him to survive for long. He is no orator: His first speeches were, in the words of one foreign observer, “extremely painful.” Several military uprisings and assassination attempts followed in 1978–79, but he survived them all; he routed his opponents and appears now to have consolidated his position. The Eighteenth Brumaire of ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih has created a Yemeni Bonapartism. His tight security, epitomized in a sprawling and electronically fortified official residence on the hilly outskirts of Ta‘iz, leaves little to chance. His bodyguard numbers several hundred, mainly members of his own Sanhan tribe. Salih has grasped the reins of government and built a rudimentary state system below him.

The YAR state, weak as it is, is considerably stronger than it was a decade ago. Salih has expanded and strengthened the army and other security forces, relying on personnel from his tribe and on military officers close to him. One brother, Muhammad ‘Abdallah Salih, is deputy minister of interior. A national army now exists for the first time in North Yemen. In 1982, it was allocated 1,810 million Yemeni riyals compared to 580 million for health and education. At the same time, the president has brought considerable numbers of civilians, including many southerners with no tribal loyalties, into the state, and he has won the grudging acceptance of many who fought for the republic in the 1960s. The prime minister, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ‘Abd al-Ghani, is a US-educated economist who has held the post for most of the years since 1975. The foreign minister, and former prime minister, ‘Abd al-Karim al-Iryani, comes from one of the most powerful republican families. The lower echelons of the apparatus are laced with kin networks and corruption. But for many people, Salih at least offers one thing: peace, internally and with South Yemen. There is now the possibility for the YAR to catch its breath after the civil war of the 1960s, in which up to a quarter of a million people lost their lives, and the fighting and assassinations that punctuated the 1970s. Their calculation on government consolidation and a prudent Yemeni nationalism has led many Yemenis to support this hybrid regime, a fusion of tribal faction, military apparatus and civilian recruitment.

The apparent consolidation of the YAR state underlines the degree to which the politics of this region, albeit greatly influenced by external forces in the Arab world and beyond, also have their own special character and dynamic. The Yemens as a whole are a rather special part of the Middle East, separate and distinct, even as they participate in and are influenced by the turmoils of the larger Arab world.

The two Yemens have been the site of some of the most momentous upheavals of the modern Arab world. But the outside world, including the rest of the Arab states, tends to take notice of the two Yemens only when these acquire, or are invested with, broader international significance. The Egyptian intervention in North Yemen from 1962 to 1967, the turmoil of the British withdrawal from South Yemen and the growth of Soviet influence there after 1967, and the strategic implications of conflict between the Yemens—these have provided focus for external concern and attention. In fact, though, the dynamic of regional politics in southwest Arabia has a lot more to do with local issues and changes than most observers realize. The rest of the world looks very different from Sana‘a (and Aden) once this is taken into account.

Three general considerations can help to place the region in a more accurate focus. In the first place, the two Yemens form a natural and historical unity, a region of settled agriculture and civilization that has existed for over 2,000 years. Like the Nile Valley and the cities of Mesopotamia, they represent one of the historic cores around which the contemporary Middle East is built, long predating nationalism or the modern state. This is often obscured if we attend only to the divisions of recent history, especially those of colonial rule, which separated Aden from the Yemeni hinterland and later devolved into two separate, often hostile states disputing the claim to represent Yemeni legitimacy.

The degree of unity is, at the same time, overstated by contemporary nationalists. They not only underestimate the local and tribal divisions that still divide Yemeni society from within, but also the degree to which two separate and unassimilable states have now arisen in this single cultural historical region. The ratchet effects of post-colonial state formation cannot be easily reversed. The practical implications of this historic unity are still significant, though. There is, for one thing, a deep popular sense that the Yemenis are a people with a single history and identity who must seek cooperation as well as peace. There is also a popular sense of what they, as Yemenis, are not, a sense that the Arabian Peninsula has long been divided between the settled and the nomads, between the sons of ‘Adnan and those of Qahtan. In today’s political terms, this means in particular that the Yemenis sharply distinguish themselves from Saudi Arabia.

This historic division of the Peninsula has been compounded by oil, the second general factor in evaluating the regional and international position of the two Yemens. Some oil deposits have been found recently in both states, but no oil in major quantities has yet been conclusively identified. Despite the great differences in the way the two Yemens are organized, both depend to a considerable extent on income from the oil states. Both are, in a certain sense, tributary of the other Peninsula countries. This bond is maintained in two ways. One is via official aid, a vital factor in the economy and state finances of North Yemen, and a significant one in the budget of the South. In the YAR, foreign aid accounted for 17 percent of GNP in 1982. The other means by which oil wealth flows to these states is through the remittances of emigrants. More than one million Yemenis, out of a population of 7.5 million, live in the other Peninsula states (mostly in Saudi Arabia), and their earnings make up much of the two Yemens’ foreign exchange income. (According to YAR statistics, in 1981, the nearly 1.4 million Yemeni workers outside the country actually outnumbered the active male labor force of 1.2 million inside the country.) YAR remittances, at some $1 billion a year, come to around 40 percent of GNP.

This proximity and link to the oil states also has negative consequences: Needed labor is attracted by the higher wages available abroad. Local wages have risen spectacularly, as have land prices, and sections of the economy have become dependent upon foreign income or foreign imports, to the detriment of other priorities and local production. The decline of food production in North Yemen has made this potentially rich agricultural country reliant on imports for 30 percent of food supplies. This is one example of the warping effect of the link to the oil-producing economies. The abandoned terraces that litter the mountains of the interior tell their own tale.

This link is also closely related to the third common and distinctive feature of the two Yemens: In a peninsula of six monarchies, these two states are republics, a result of the revolutions both countries went through in the 1960s. No revolution makes a clean sweep of the old order and its culture, but these continuities should not obscure the fact that very widespread political and social changes did occur, involving the mobilization and combativity of significant parts of the population in both states.

As nearly always happens, these Yemeni revolutions acquired an international character. For one thing, they sought to encourage like-minded political forces elsewhere in the Peninsula. ‘Abdallah al-Sallal, the first North Yemeni president, opened an Office of the Arabian Peninsula in 1963 and called for the overthrow of the Saudi monarch and the creation of a united socialist Arabia. His republic also gave support to the guerrillas in South Yemen. The National Liberation Front in the south came to power committed to encouraging the guerrillas in neighboring Oman, and to supporting the radical republicans in the North opposed to compromise with the royalists and with Saudi Arabia.

The opponents of these revolutions were equally concerned to internationalize them, by aiding the opponents in North and South. Saudi Arabia, in particular, has sought to contain and, if possible, reverse the upheavals in the two Yemens. This internationalization of the Yemeni revolutions has had a powerful divisive effect as the two independent states differed more and more after 1967. They fought two border wars, in 1972 and 1979, and until 1982 each repeatedly gave support and encouragement to opponents of the other.

The North Yemeni revolution of September 1962 set off a process of political and social conflict in southwest Arabia that spread from the north to the south and then to the Dhofar region of Oman. It was only in 1982 that this 20-year war came to an end, with the cessation of the guerrilla war in North Yemen and the establishment of diplomatic relations between Oman and South Yemen. (The Omani guerrillas, active in Dhofar, had been effectively crushed in late 1975.) The policies of the two Yemens can therefore be regarded as located within this specific and in some ways novel environment—of consciousness of the Yemens as a distinct and regional entity, of a difficult and yet inescapable dependence on the oil-producing states, and of a revolutionary past that has, at least temporarily, given way to a new period of peace and consolidation.

The end of North Yemen’s civil war in 1970 produced a coalition government in which elements from the royalist camp joined with the republicans. Conflict emerged within the republican camp, as some left-wing groups refused to accept the peace and others on the right thought that the government was going too far in enforcing central control of the tribes. President al-Iryani was ousted in June 1974; his successor Ibrahim al-Hamdi was assassinated in 1977; and al-Hamdi’s successor, Ahmad al-Ghashmi, was killed by a bomb apparently sent from South Yemen in 1978. The left-wing forces fought a guerrilla war from 1971 to 1973, and again, after the death of al-Hamdi, from 1978 to 1982. President ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih’s consolidation of power with a more effective central state apparatus and a stronger central army, and the defeat of the left-wing National Democratic Front, has been offset by a serious economic problem. Foreign revenues have stagnated. The YAR budget deficit makes up 30 percent of GDP. The republic’s exports are minimal. Workers’ remittances have leveled off and are expected to decline in the period ahead. The crisis of October 1983, when a new cabinet was installed and stringent import controls imposed, signaled the end of North Yemen’s easy reliance on wealth from the oil states. The discovery of some oil in July 1984 by Hunt Oil may alleviate these problems, but the scale of the discovery is as yet unclear, and in any case would not be productive for at least half a decade more.

For reasons of economy, therefore, as well as because of influence which it wields within North Yemen, Saudi Arabia remains the main point of reference for YAR foreign policy. The Saudis have in the past suspended payments to YAR governments when these have pursued policies of which they disapprove. Through their direct links to the northern tribes, and in particular to the Hashid group of Sheikh ‘Abdallah al-Ahmar, they have an alternative to direct financial pressure upon the government itself. The Saudis are aware that overt pressure will only antagonize the Yemenis, and so they have kept their influence steady but indirect. The Saudis’ primary aim is to keep a friendly government in power in Sana‘a, and to prevent it from establishing too close relations with either the USSR or the PDRY. But Saudi Arabia has also to contend with other Arab influences in the YAR—Egypt in the past, and more recently Iraq and Libya have sought influence within the armed forces.

No political parties are permitted in the YAR. The official government political body is the 1,000-member General People’s Congress, 700 of whom are elected and 300 nominated by the president. It acts as a surrogate ruling party, channeling political action and patronage, and its charter is used for two-hour political orientation classes in government offices every week. Censorship is extremely tight, and none of the major upheavals of recent years—even the 1979 war with South Yemen—was mentioned at all in the government press.

Shadowy political coalitions, involving the military, tribal and urban intellectual elements, have existed since before the days of the civil war. Many believe that the pro-Iraqi Baathists still have some influence. South Yemen has, until recently, supported the National Democratic Front. In recent years, a tendency close to the Muslim Brothers, known locally as the Islamic Front, has gained influence, to a considerable extent via the 23,000 Egyptian teachers in the country. The Islamic Front has gained ground in the university, and many women now wear the nun-like headdress pioneered by Egyptian fundamentalists. This constitutes a new political force friendly to the Saudis and hostile to the PDRY and its supporters in the north. Four of the ministers in the cabinet of October 1983 are believed to be members of the Islamic Front, and the Saudis must see in it a new channel of influence. The president’s brother and deputy minister of interior, Muhammed ‘Abdallah Salih, may be a potential candidate for the loyalties of this group.

North Yemen has been careful to cultivate relations with the various factions of the Arab world. It has been critical of the peace initiatives taken by Egypt, but has not fallen into the rejectionist camp that has severed all ties with Cairo. It has from the start supported Iraq in its war with Iran, and has supplied some of its Soviet equipment to the Iraqis in return for payment. It has received substantial aid from Kuwait and the Emirates, but it is not a candidate for membership in the Gulf Cooperation Council, the grouping of six Arab oil producers of the Peninsula set up in May 1981. As one high-ranking government official put it to me: “There are reasons why we will not be allowed to join. First, we are a republic. Secondly, we are poor. And thirdly, if they let us in, then they would have to let the Iraqis in as well.”

[…]

Both the YAR and the PDRY talk of unity at some time in the future. Both are too suspicious of each other, and have too great an investment in their separate state structures, to risk that.

The “unity process” does bring some concrete benefits to each side. It encourages a sense of non-belligerency between the two governments, and a reining in of the elements within their own states which seek to overthrow the government of the other. The National Democratic Front remains an organized force in South Yemen, and the National Coalition, a gathering of exiles from the South, maintains a position in the North. But after 20 years of conflict, a more durable coexistence between the two Yemens does seem to have emerged.

Unity involves certain forms of cooperation—in joint companies for tourism, shipping and insurance, and in collaboration between the educational ministries and writers of the two countries. A Yemeni Council, composed of the presidents of the two states and selected ministers, meets every six months to discuss “unity,” and a 136-article draft constitution has been prepared: But the meetings of the council so far have yielded no specific decisions, and the unpublished text of the constitution is being “studied” by the two presidents. Unity in the sense of a merger of the two states is almost inconceivable. Like all neighbors, the two Yemeni revolutions are condemned to living with each other.

The problem of unity between the two Yemens is nevertheless posed as sharply by the impossibility of a real unification as it would be by any prospect of a fusion of the two states. The YAR and the PDRY are locked into a relationship that is both close and conflictual, because of their shared characteristics and because of the divergent and competitive outcomes of their two revolutions and the two state structures that resulted from them. Each needs the other, and needs to sustain a politics of Yemeni nationalism, to balance their international alignments and maintain domestic legitimacy. Yet, albeit now in a more peaceful form, the competition between them continues. “Peaceful coexistence” in Southwest Arabia has all the contradictory interaction of its more global East-West version, since it is the coexistence of the two social and political systems that must continue while both have to avoid an outright war.

[…]

How can social tensions be managed and policy differences resolved by ruling socialist parties in poverty-stricken Third World states? On January 13, 1986, this question defeated the Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP) in a devastating spasm of civil war. Parallels can be drawn between the South Yemeni trauma and the equally tragic collapse of unity within the New Jewel Movement in Grenada, although the regional conjunctures were different and the geopolitical context of the Yemeni Republic precluded a Reaganite outcome.

The South Yemeni state emerged out of the victorious struggle against British colonial rule in 1967. A population of some 2 million people live in a land that is almost totally barren; only 2 percent is cultivable and only 1 percent cultivated. Expanding the agricultural area is almost impossible because of the lack of water. Two land reforms after the revolution have brought most of the land into about 60 collective farms and 50 state farms. Some private peasant plots have been allowed, but under stricter limitations than, for example, in the Soviet Union. Despite efforts to achieve self-sufficiency, only about half the country’s food requirements are met domestically. Lack of capital inputs and of trained agronomists and managers has caused severe problems, especially in the state farm sector, where a great deal of investment has been wasted. In 1984, only three of the 24 crop-growing state farms operated profitably. Since the late 1970s, fishing has developed as the one non-industrial sector able to expand successfully. Fish has become the country’s major export, both to the Soviet Union and to the Far East. Per capita income in 1982 was $460. In 1985, agriculture accounted for 10 percent of output, but 42 percent of employment; the figures for industry were 16 percent and 11 percent respectively.

For almost all of its 18 years of existence, the South Yemeni state has been a focal point of continuous war between revolution and counterrevolution in the region, but it has gained a measure of strategic security through its continuous close relationship with the Soviet Union. Politically, the Soviet view has been that it is absolutely premature to speak of a transition to socialism in a country with such a weak natural endowment, massive illiteracy, great shortage of cadres, and so on. Right from the beginning, Soviet advice has been strongly against what it sees as domestic adventurism, favoring caution, accommodation to Islam, liberalization, a conditional opening to the oil states, and the loosening of control on the peasants and fishermen. Thus, Soviet views have always been more moderate than many of the indigenous South Yemeni political currents both on internal social policy and foreign policy. The Soviets have argued that, in the long run, efforts to “normalize” relations with the Saudis and Oman would weaken the position of imperialism more than a position of support for movements against those surrounding regimes.

The Soviets have sought to avoid becoming too deeply involved in the internal politics of the country, and it is only in the last few years, under the government of ‘Ali Nasir, that Soviet and South Yemeni views of how to proceed internally and externally have drawn closer together. Moscow has given South Yemen some $270 million in aid over the past 18 years, accounting for about one-third of the total aid received since independence. The non-Soviet contributions have come from China ($133 million), other socialist states, the Arab states and multilateral agencies.

The Soviets do not maintain a military base in the sense of a sovereign area or permanent troops, but Aden is valuable as a naval port and depot more secure than any others in the region, and they no doubt maintain some intelligence-gathering facilities there.

The South Yemeni ruling party was founded in 1963 as the National Liberation Front (NLF), which carried the guerrilla war against Britain to victory in 1967. In 1978, it transformed itself into the Yemeni Socialist Party. It has a membership of about 26,000, some 20 percent of whom have been army personnel. Less than 15 percent are members of the working class (by their own criteria) and most of the rest are peasants, intellectuals or party officials of one kind or another.

Throughout its existence the organization has been marked by factionalism. First of all, the liberation struggle itself was at least as factional as that in Angola or Zimbabwe: The NLF’s victory in 1967 was won not against the British alone, but also against the Front for the Liberation of South Yemen (FLOSY), the rival, more pro-Egyptian group with whom it had been impossible to achieve unity. More people were killed in the conflict between the NLF and FLOSY—a mixture of personal, political and regional issues—than either group lost at the hands of the British.

After independence, there was an initial rivalry between a quasi-Nasserist faction under President Qahtan al-Shaabi and those regarded as the “Marxist-Leninist” left. The latter came to power in a bloodless coup on June 22, 1969. (Al-Shaabi remained under house arrest almost until his death in 1980.) The Front then began transforming itself into a “party of a new type,” following what it regarded as a Leninist model. It united with two smaller political groups—a pro-Syrian Baathist faction and a small, pro-Soviet communist party, the Popular Democratic Union (PDU). This was a fusion in some ways similar to that between Fidel Castro’s movement with the Partido Socialists Popular in Cuba, but the Cuban PSP was a much larger political force than the PDU had been.

In 1978, just before the first congress of the YSP took place, another major factional conflict broke out. On June 26, 1978, President Salim Rubai ‘Ali tried to seize power against the majority on the Central Committee. Though not a Maoist in a strict sense, ‘Ali was opposed to an orthodox party and advocated spontaneity. He believed in appointing people on the basis of political principles rather than functional competence and in the early 1970s he had tried, with catastrophic consequences, to imitate the Chinese Cultural Revolution in South Yemen. But he remained a popular leader, with a larger following than the party leaders who defeated him in 1978.

The man who emerged as president in 1978 was ‘Abd al-Fattah Ismail. After less than two years in office, he was ousted in a bloodless change of government in April 1980, on the grounds that he had promised too much from the alliance with the Soviet Union and had mismanaged the economy. His opponents dubbed him derisively with a Khomeinist label, the faqih, the interpreter of religious law, a dogmatic Marxist who buried his head in the books but was technically and administratively incompetent. In the mid-1960s, ‘Abd al-Fattah proclaimed the need for a Marxist-Leninist line, by which he meant a struggle against the “petty bourgeoisie.” This entailed combating the small traders on whom Aden’s prosperity depended, and those whom he called the “kulaks” in the countryside. This dogmatic view of economic and social development scarcely equipped him for managing the country’s affairs competently, yet many people remained loyal to him. He went into exile in the Soviet Union, but was able to return in 1985. He was a prominent figure leading the movement against the government this January, and he died in the conflict.

‘Abd al-Fattah’s successor in 1980 was ‘Ali Nasir Muhammad, who remained in power until the January crisis. Continuing tensions during these last five years indicate that factionalism, not just a left-right conflict but various shifting alliances and currents, has been an endemic feature of the Socialist Party. One source of this factionalism has been two divergent forms of radicalism: an indigenous, Yemeni trend and a more orthodox, bookish radicalism. The revolution’s origins lie very much in the first; the second, regarding itself as orthodox “Marxist-Leninist,” flourished in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Under ‘Ali Nasir’s presidency, these contrasting trends did not apparently diverge over relations with the Soviet Union or China or the West. They clashed over two partly interrelated issues: internal economic policy and policy toward the region.

The dominant internal question was: How far does domestic economic development require the loosening of state controls? The first ten years of highly centralized economic regime did not yield many results. As state controls loosened in the late 1970s, and even more so under ‘Ali Nasir Muhammad in the 1980s, living standards rose. There was more foreign aid, private traders were given greater leeway, peasants were allowed to sell about a dozen different products at prices ranging up to 150 percent above those in state markets, and controls on fishermen’s sales were also relaxed. This was not a case of completely free markets, such as exist for peasants in the kholkhoz [collective farms] of the Soviet Union. It was a controlled liberalization, nothing more.

There was also an attempt to encourage Yemeni workers abroad to send back more money. These workers amount to perhaps one-third of South Yemen’s able-bodied young men. They send back over $300 million a year, which amounts to between 60 and 70 percent of all South Yemen’s foreign exchange earnings. In 1982, for example, exports of $21 million contrasted with imports of $747 million. The contribution of the workers abroad came not only in foreign exchange but also in imports of consumer goods. By the age of about 35 such workers are worn out and have to be replaced by younger workers going abroad in search of jobs.

Economic liberalization was a source of tensions. When the private sector began to have higher incomes, people on party salaries became nervous. The result was the classic pattern of growing party privileges: in the mid-1970s, special shops for members of the Central Committee; then privileged access to certain goods; then increased license as to what people could bring back from foreign trips, special allowances for state functionaries to buy foreign exchange goods, the provision of air conditioners, video machines and cars. This was done from the top downward. During this time, for example, the army had been completely reequipped by the Soviets, so the old leadership decided they would get rid of superfluous British arms by selling them to smugglers at the Saudi frontier in return for Toyota cars. The arms most likely ended up with the Afghan mujahidin, probably the only people in the world looking for Lee-Enfield replacements. The Toyotas were allocated to officers in the army and members of the party. In a very small and very visible society, this created rifts. When everyone had been poor, there was less tension; when more goods became available, competition became greater.

To all this must be added the dimension of class forces within the country and outside. There were clearly internal social groups who realized that such developments increased their leverage, and there were both émigrés and foreign governments who realized this was a wedge for undermining the socialist experiment. Just as people living in Havana are aware of Miami, so Adenis know the very high living standards in the Gulf. Such acquaintance comes not only from the migrant workers but also from people being able, since the late 1970s, to pick up television programs from North Yemen, with their idealized picture of North Yemeni life.

So this economic loosening certainly created social tensions and instability, as it did in Cuba in the late 1970s. And insofar as ‘Ali Nasir promoted this policy, differences within the party focused upon him. There was no doubt an increase of corruption in official circles as well.

The second broad source of policy struggles within the party concerned relations with neighboring states. In the Dhofar province of Oman there had been a decade of war from 1965 to 1975. There had been border clashes with Saudi Arabia. It is only very recently that the South Yemeni government has established diplomatic relations with neighboring states. In the cases of Saudi Arabia and Oman, there is no dispute that South Yemen has to find ways of living with its conservative neighbors. But in the case of North Yemen, the South had, until 1982, supported the National Democratic Front there, the successors of the radical republicans of the 1960s. This decision to stop supporting the rebels and to press for normal relations with the Sana‘a government involved bringing some 2,000 Northern rebels south and settling them in camps. This undoubtedly aggravated the internal situation even more, reflecting 20 years of revolution and counterrevolution in South Arabia.

Virtually every aspect of life in North Yemen has changed dramatically since 1977, including those aspects of Yemeni society which represent continuity with the past: tribalism, rural life and the use of qat. The driving force for change has been economic. By 1975, Yemen was caught up in the dramatic developments that affected all Arab countries. Rising international oil prices generated enormous surpluses in the producing countries, enabling them to initiate ambitious development plans and forcing them to import workers.

The Yemen Arab Republic was in a good position to provide those workers. In the late 1970s, one of the jokes around the capital city, Sana‘a, was that Yemen had neither an “open door” nor a “closed door” but a “no door” policy with its oil-producing neighbors. Ill-defined and sparsely settled borders allowed easy movement of Yemeni workers to Saudi Arabia and of their remittances and goods back home.

In addition to geographical proximity, Yemenis enjoyed a certain social proximity to the Saudi job market. Until August 1990, Saudi Arabia allowed Yemenis to live and work in the Kingdom without visas. Many Yemenis owned businesses in Saudi Arabia, while other foreigners were not granted such rights. In the early years of the oil boom, many older Yemeni migrants found a good market for the skills they had learned in Aden when it was a British colony: knowledge of English; and commercial, domestic or secretarial skills. These advantages placed Yemenis ahead of their competitors for jobs, at least in the years prior to the arrival of highly organized work brigades from South Korea and elsewhere in Southeast Asia.

This movement of labor had a phenomenal impact on North Yemen. Some Yemeni regions lost up to half their male labor force to the Gulf, and the national total may have reached as many as 1.23 million. By 1982, remittances reached an annual record high of $1.4 billion. It was a time when Yemeni citizens, on average, vastly increased their spending power. Yet the government, unable to effectively tax these remittances, was forced to rely on friendly countries for aid to meet its basic fiscal commitments. Officially recorded foreign aid reached $401 million in 1982, mainly from wealthy Arab states and to a lesser extent from multilateral and other bilateral donors.

[…]

These conditions affected the lives of virtually every Yemeni family over the years 1977–89. We examined the cases of two families that occupied very different positions in the old social hierarchy. The first is an urban family from the Old City of Sana‘a, members of the sayyid strata, reputedly descended from the Prophet. The second is a peasant or ra‘iyya family living in rural Ta‘iz.

Both families had prospered during the short-lived period of affluence only to find themselves now unable to maintain the same standard of living despite their hard work. Lacking the economic and political currencies needed in contemporary society, by the summer of 1989 they each found themselves in a precarious position. These cases show the extent to which family fortunes are connected to the national economy, and illustrate the replacement of old status rankings by factors related to class. Whereas in the old days a Zaydi sayyid family related by marriage to the royal family was considered part of the pampered Sana‘ani “elite” and the Ta‘iz family were smallholder peasants, both were now self-employed at the margins of a national market economy. Neither family possess the prerequisites for success or even security in this new economy: the right educational certificates, the right political connections (or “backing”) and money.

The household perspective also reminds us that through this tumultuous period women in particular held tenaciously to traditional Islamic and cultural values, modified only superficially by the introduction of new commodities into their daily lives. Living by traditional ethical values, however, seems more difficult than before.

The Sana‘ani family today includes a relatively young matriarchal figure and widow, Amat al-Karim, her son ‘Abd al-Rahman and daughter Khadija, their spouses and ten young children.

In Amat al-Karim’s eyes, Khadija and ‘Abd al-Rahman were born into nobility. Though neither rich nor politically active, they lived in a fine quarter inside the northern gate of old Sana‘a, between a mosque and its garden, just off a main street, the markets and a square with a school.

Amat al-Karim loved her husband, Muhammad, a gentle, honest scribe who traced his ancestry directly to the Prophet. She was grateful to her parents for the good match, for her sister’s marriage to a branch of the royal family, and for her own modest inheritance of several farming terraces outside town. Her son and daughter, toddlers at the time of the 1962 revolution, grew up proud and pious like their parents. She herself was able to half read, half recite the Qur’an, and so enrolled them in school. By the time of Muhammad’s death in 1970, Khadija had completed five years and ‘Abd al-Rahman had finished intermediate school.

Neither Amat al-Karim nor her neighbors could anticipate the fantastic changes of the 1970s, as secondhand affluence from the oil boom and continuing upheaval within Yemen transformed the world around them. Through this tumultuous period, Amat al-Karim and her children held closely to the family and religious values she learned as a child, but their own choices and the changing environment left them in a very different position 25 years after the revolution. Whereas the status position of a Sana‘ani sayyid previously ranked the family among the elite, nowadays it is their economic class that situates them socially.

Amat al-Karim found spouses for her children through the network of her aunts and sister. Both literate and demure, Khadija was not wanting for suitors. In the end, Amat al-Karim accepted as her son-in-law a military man, who was often stationed in Cairo during the early years of their marriage. Because of his frequent travels, Khadija continued to live in her mother’s home. For her son, Amat al-Karim selected from their wide kinship network a bride nicknamed Ghafura, who also moved into their crowded house.

Their house in the old city consisted of three stories. Goats, chickens, fodder, fuel and grain were kept on the ground floor. Amat al-Karim shared the second story flat, containing a large diwan (sitting room), two bedrooms, a traditional bathroom and a large ordinary room used for baking, cooking and eating, with ‘Abd al-Rahman and his family. Khadija and her children occupied the smaller top flat.

In the late 1970s, the family enjoyed the benefits of Yemen’s new affluence, although none of them joined the flood of workers going to the Gulf. ‘Abd al-Rahman, whose educational qualifications were rapidly becoming insufficient, had become bored with his routine, low-paying government clerkship. Somewhat idly at first, he began painting Islamic verses on colored glass, of the sort commonly embedded in the plaster around interior windows and doors in Sana‘ani houses. With the flurry of new residential construction taking place in Sana‘a at the time, sales were soon so brisk that ‘Abd al-Rahman matched his government salary and more in his afternoons. He rented a neighborhood shopfront and quit his government post about a year before his marriage in 1977.

Through 1980 ‘Abd al-Rahman scarcely kept track of his daily earnings, but often grossed 500–1000 Yemeni rials a day ($111–221). Much of the income went toward buying appliances. As they became available on the market, the family bought a tape recorder, washing machine, refrigerator, television and video. They paid gladly for water and electricity hookups and purchased better quality meat, qat, household items, jewelry and clothing, although their tastes remained quite traditional. Their courtyard goats and chickens were replaced by milk, eggs and meat purchased from the market.

Khadija and ‘Abd al-Rahman’s wife, Ghafura, turned their attention wholeheartedly to motherhood, enjoying almost annually the 40 days of festivities and relaxation that follow childbirth. They passed their time at home with the children or celebrating the marriages and births of others. Khadija bore five children in the first decade of marriage (one of whom died); Ghafura had six. The three-story house resonated with the sounds of children.

In 1982, members of the family decided to pool their resources (Khadija’s bridewealth, savings from the men, cash traded in from jewelry and loans from relatives) to purchase a fashionable new one-story house outside the walls of the old city. It cost 220,000 riyals ($48,888 at the new, lower exchange rate). They spent a further 50,000 riyals on decoration and a Western-style bathroom. The kitchen was a separate open room in the courtyard, a more healthful arrangement than in their old house. Khadija and a widowed aunt continued to live in the increasingly decrepit house in the old city.

By the summer of 1989, the family retained neither the prestige of the old era nor the affluence of the oil-boom years. ‘Abd al-Rahman now earns less than half what he made in the peak years. The slowdown in housing construction has meant less demand for his religious verses and patriotic designs. The devaluation of the Yemeni riyal has increased the cost of his paint and glass. Many other necessities and niceties of daily life also cost more, and family demands surpass what he brings home. Ten-year-old appliances are breaking down, and need to be repaired or replaced.

‘Abd al-Rahman’s wife and sister now tell him that had he stayed in his secure civil service job, he would probably be a director by now and that surely a decent position awaits him still. He checked into the possibility of returning to the government, but learned that his intermediate education would gain him only an unskilled, entry-level position and a meager salary. The traditional familial ties that yielded good marriages in the old city are of limited value now in the world of government. In his late 30s, he is the model Sana‘ani son, husband, brother and father—loving, sober, hard-working and pious. Yet the smart Western suits of today’s successful men are not his style, and his nieces call him old-fashioned. Like his old neighbors and friends, he manufactures artifacts linked to the lifestyles of an earlier generation. His children prefer imported goods.

Khadija has by now joined her husband in Cairo. They live in a fourth-floor, four-room suburban apartment. There is no place for her children in overcrowded Egyptian schools. Ghafura, for her part, lives with her family in the one-story suburban house, now surrounded by workshops, a lumber yard and the smaller houses of recent arrivals from the countryside. Both women longingly recall the old days in the old city, with its familiar social network and the never-ending cycle of afternoon parties for new brides and mothers. They both fear that their children are not being taught the proper old city manners, respect and piety that they want them to have. They are keenly aware of the importance of school certificates, yet they remain more concerned about their children’s moral education.

Far away from Sana‘a, in a village outside Ta‘iz, the Qasir family represented the epitome of success. Theirs was an extended family in which all except Mustafa, the father, resided in the tall stone house in the village and worked in agriculture. They worked on lands they owned or rented in a sharecropping arrangement (shirka) common in that part of Yemen. Like other families with excess labor, they took in rented lands to maximize production.

The grandfather, ‘Ali, had spent his youth as a stoker on steamships moving from Aden to Southeast Asia, Suez, Europe and beyond; he returned to farming after his retirement, doing what men do in agriculture in those parts of Yemen—the plowing and threshing. Grandmother Sybil worked alongside him, and tended to the farm animals. ‘Aziza, their daughter-in-law, managed the household; she organized maintenance tasks such as shopping, cleaning, cooking and fetching water, arranged agricultural work, and helped her father-in-law decide about expenditures. In the afternoons or during agricultural slack periods, she was a seamstress. In the 1970s, ‘Aziza’s three sons and three daughters were in school but they also helped with cooking, cleaning, fetching water, running errands and shopping in the market town, and with agricultural work.

‘Aziza’s husband, Mustafa, was in Saudi Arabia, where he held down two and sometimes three jobs. As a boy he had lived with his father in Aden, where he learned some English, how to be a houseboy, cook and servant, and how to read and write Arabic. In Saudi Arabia, he worked variously as a construction foreman, a cook, a clerk and a shop attendant. To keep down costs, he shared living quarters with other Yemeni migrants, sent a small remittance to his father each month, and scrupulously saved every riyal of the rest. When he returned to Yemen after four years away, he brought with him luxurious gifts: a fake fur coat for ‘Aziza, a color television, new and fashionable ready-made clothes for his children, imitation Persian carpets, a washing machine, a Butagaz-fueled stove with oven, a blender and other household appliances. He took his parents on the pilgrimage to Mecca. The bulk of his savings went toward the cost of building a new house, a one-story bungalow, for ‘Aziza and their children.

Mustafa returned to work in Saudi Arabia, but in 1983 he lost one job after another. After an extended and fruitless search for new work, he returned to Yemen.

Since then he has drifted from one unsuccessful venture to another. At one point, he was unable to repay a bank loan he had taken out to start a small restaurant; ‘Aziza sold and pawned her jewelry to make the bank payments. It has been difficult for Mustafa to settle into business because he now needs certificates and permits for everything, and must bribe officials to get them. He has become exceedingly discouraged about the possibility of earning a decent income honorably.

He has also become disheartened about his own children, especially his sons, who do not appreciate the value of hard work, spend more than they earn, and seem ashamed by his lowly work and powerlessness. Some call the new generation the “Nido generation”—spoiled on the Nido powdered milk so plentiful in the affluent 1970s.

Mustafa’s and Aziza’s eldest son Hamud works in a civil service job in Ta‘iz. Like many other village men, he lives in town during the week and returns to the village on weekends. Nearly 30 years old, father of three, he spends more than he earns on his personal habits: smoking cigarettes and chewing expensive qat daily.

Chewing qat has taken on enhanced functions in Yemen in the 1980s. Nationally, consumption is on the rise because more people—men and women—are chewing daily. Average daily chews cost about 100 riyals ($10). Together with the cost of cigarettes, expenditures on this recreational drug can easily exceed a household’s income. There is new evidence that some men are inadvertently “starving their families” to support their qat consumption. That fathers like Mustafa, who in an earlier era would have reached middle age and been supported by their sons, are instead finding themselves covering their sons’ debts, means that somehow, begrudgingly, they appreciate the important social function of the qat chew for their sons. Yemen is a more complex place now than it was in their youth. To get things done in Yemen today, one needs “backing.” Backing assures individuals of jobs, certificates, perquisites, “justice” and business opportunities. If one does not have a tribe to turn to, as is the case for many of the southern districts of the country, one creates and reinforces one’s backing through daily social intercourse around qat.

It is not surprising, then, that Hamud has failed to relieve his parents of their burden of work by providing regular cash support. His irresponsibility has become the major source of conflict in the family, particularly when he runs up large debts that he expects his father to pay. Yet everyone knows that his irresponsibility is the necessary price of keeping in with friends and in the know. Men who do not chew qat are stigmatized as miserly, negative and anti-social.

In 1988 the second son, Salih, a university student, pressured his parents into coming up with enough money to allow him to marry a cousin. When Mustafa and ‘Aziza finally acknowledged that it would be impossible, he left for town and refused to visit them until a year later, after they had made arrangements to finance the marriage. When the marriage finally took place in 1989, with an installment brideprice and “no frills,” Salih only complained that things were not good enough for his bride and himself.

Other aspects of family life have changed as well. When ‘Aziza and Mustafa moved into their own house, they insisted on reducing the amount of rented lands taken in by the extended family. They would work on their patrimonial plots, but no more. ‘Aziza also looks after six sheep, but no longer keeps more demanding animals such as cows. Nor does she sew clothes for her daughters and herself; it is more economical to buy the cheap imported clothes from Southeast Asia which are now available in the village shops, the Turba market and Ta‘iz town. ‘Aziza and her daughters derive great pleasure from their leisure time, something unknown to them a few years ago. They spend their afternoons and evenings sitting in front of the television, watching Egyptian soap operas or Saudi religious programs.

‘Aziza worries about her daughters and their future marriages. She wants them to marry close so that she can keep an eye on them, but views the pool of desirable bridegrooms as distressingly small. She questions the sincerity and ultimate motivation of the youthful converts to religious fundamentalism, and wants her daughters to have nothing to do with them. “These religious men say that everything is shameful (‘ayb): We shouldn’t go out with uncovered faces, we shouldn’t educate our daughters. This isn’t real religion,” she says. Yet, as ‘Aziza has seen with her own sons, the current situation forces many ambitious young men in the direction of excesses: irresponsible financial management, corruption, and overconsumption of qat, cigarettes and even alcohol. As she puts it, “Life nowadays is unstable.”

As the prosperity and satisfaction of the 1970s gave way to the austerity and relative deprivation of the 1980s, a sense of frustration and alienation developed. We noticed it especially among these women and their friends who, always quick with a quip, grew increasingly cynical about the political order. Though both families enjoyed the security of home ownership, they each now relied mainly on the precarious earnings of one man with nothing of material value to pass on to his sons. The women worried about this, about the erosion of the moral fabric of society, and about the contradictions between what they still felt was right and the kinds of action that seemed necessary to get ahead.

Authors’ Note: Names have been changed. While the details of the families’ lives are true, the general opinions that were expressed were gathered in Yemen at large.

To the outside world, the unification of the two Yemens in 1990 resembled the German experience in miniature. North Yemen (the YAR) was considered a laissez-faire market economy, whereas the South (the People’s Democratic Republic) was “the communist one.” When, weeks ahead of Bonn and Berlin, Sana‘a and Aden announced their union, Western commentary assumed that in Yemen, as in Germany, capitalist (Northern) firms would buy out the moribund (Southern) state sector and provide the basis for future economic growth.

In theory—and in Germany—capitalism and socialism are distinguished by patterns of private and public ownership of the means of production. In North and South Yemen, however, differences in ownership patterns were largely evened out by comparable access (and lack thereof) to investment capital. Disparities in the relative weight of private and public enterprise were far more subtle than the designations “capitalist” and “socialist” indicate. Indeed, available data on private and public participation reveals common patterns of spending. The North’s state sector invested more than did the private sector, while the South’s socialist policy statements belied the increasing role of domestic and foreign private firms.

Relatively poor countries situated on the periphery of the Arabian Peninsula’s oil economy, both Yemens relied on labor remittances and international assistance. Both Yemens faced austerity when falling oil prices, compounded by a drop in Cold War–generated aid, reduced access to hard currency—until the discovery of oil in the border region in the mid-1980s attracted a third type of international capital from multinational petroleum companies. These forces cumulatively reduced the differences between the two systems and added an economic dimension to the political incentives for unification. In contrast with Germany, their marriage was more a merger than a takeover, for neither was in any position to buy the other out.

Historic Yemen was a cultural entity rather than a political unit; its formal division stemmed from British imperialism in the South. Unlike the relatively isolated, independent North, where a semi-feudal agrarian society persisted, the South developed capitalist classes, markets and enterprises. The major port between the Mediterranean and India, Aden’s modern infrastructure and services attracted a small indigenous capitalist group, a working class of stevedores and industrial labor, and a small urban middle class, including shopkeepers and intellectuals. Sana‘a, by contrast, was a center of Islamic conservatism ruled by a Zaydi Shi’a imam. Strict trade and investment restrictions protected a few monopoly importers and large landowners. Would-be bourgeoisie and working-class aspirants escaped this restricted environment for the free port at Aden. The North was ripe for a kind of bourgeois revolution, opening the door to capitalist development, just when the South’s radical anti-imperialism slammed the door to foreign investors.

After the 1962 revolution and 1962–68 civil war, the North (the YAR) became a “no doors” economy, with few legal barriers to either trade or investment. Revolutionaries in the South after 1968 nationalized or collectivized many foreign enterprises, large estates and fishing boats. Whereas the South was subsequently governed by a single Soviet-style Marxist party, in the absence of legal parties politics in the North were dominated by fluid tribal, Islamic and leftist “fronts” covertly supported by other Arab regimes.

The two Yemens shared a physical environment where household-scale cereal and livestock production employed most men and women. Both governments were unsure of their authority in the countryside, and each backed elements of the other’s opposition. The economies remained intertwined. In the early 1970s, the Southern bourgeoisie, some of them originally Northerners attracted to Aden’s port economy, moved back north to Ta‘iz, Hudayda and Sana‘a, where they established businesses and held government posts. After the rise in oil prices in 1973, worker remittances fed consumption (imported goods, residential construction) rather than productive investment, despite both regimes’ efforts to mobilize these funds for agriculture and industry.

The more affluent North enjoyed higher consumption of imports, but ran far worse current account deficits. Although the labor force was still predominantly agricultural, especially in the North, over half of gross domestic product in both systems was generated by services; the rate of new investment in services, especially government services, indicated that this trend would continue. The level of education and health services—slightly better in the South, especially for women—put both countries among the world’s least developed nations. While central planning was a goal of the leadership in the South, in the North planning was not an ideological commitment but rather part of the documentation required by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

The South, with its colonial legacy, entered the 1960s with many more capitalist enterprises than North Yemen. South Yemeni nationalizations and land reforms created a modern state sector, and dramatically equalized land ownership, but retained many features of a traditional agrarian economy comparable to that of North Yemen, which was just embarking on its first commercial and industrial projects.

Production systems in the South included subsistence agriculture on family land mixed with herding on commons, sharecropping on pre-capitalist estates, and wage labor on modern farms. In Aden and Lahij, where ownership was most distinctively class-divided, the revolutionary regime expropriated the largest holdings as well as religious endowments (waqf). The number of expropriated estates increased from 18 to 47 between 1975 and 1982 with the addition of some smaller properties of unpopular landlords. These state farms, with modern equipment and wage labor, managed most farmland in Aden governorate and nearly a third in Lahij just to the north. Redistributed land, nearly two-thirds of the South’s cultivated area, was classified as cooperative. Over a quarter, mostly in the east, remained private.

By contrast, the revolution in the North nationalized only the royal family’s prime tracts. Over half of the large farms were private and were conservatively managed, frequently employing sharecrop labor and moving only slowly toward capitalist farming. Most dry land in both systems consisted of family-cultivated parcels or open range. Well into the 1980s, at least half of Yemeni farms produced cereals and livestock for cultivation. The only popular, profitable cash crop in the highlands was the narcotic leaf, qat, outlawed in the South and discouraged by the North’s Ministry of Agriculture.

Both regimes advocated farm mechanization, yet typical Yemeni farmers planting sorghum or millet with their own draft animals on small, scattered, often terraced parcels were unable to profitably invest in pumps, tractors or trucks, even with remittance income. Each regime turned to cooperatives around 1974, hoping to combine petty savings and remittances for investment in nurseries, equipment, repair stations, storage facilities and marketing services. Southern holders of redistributed land formed purchasing and marketing cooperatives. Sixty-odd cooperatives helped up to 50,000 members acquire inputs in the mid-1980s, but instead of moving toward full-scale cooperative farms, 29 state farms abandoned group farming and only two produced collectively.

Although Northern cooperatives built stopgap rural infrastructure, the 20-odd agricultural, fishing and craft cooperatives foundered on both credit and marketing. Voluntary participation often made no sense as an investment. While a few cooperatives profitably ran diesel stations or rented drilling rigs, most failed to mobilize and manage share capital.

After nationalization, public ventures controlled 60–70 percent of the value of industry in the PDRY, including power and water and the oil refinery (the single largest employer). Mixed companies produced cigarettes, batteries and aluminum utensils; wholly private firms were either small-scale plastic, clothing, glass, food and paper goods manufacturers or traditional carpentry, metal, pottery or weaving industries.

Whereas the South inherited modern plants and offices, the North embarked on its first modern enterprises only in 1970. Despite liberal investment incentives, private manufacturing grew slowly. An industrial complex near Ta‘iz producing sweets, soaps and plastics, owned by the Hayel Sa‘id Group, dominated large-scale private industry. The remaining large private factories were mostly food processors or bottlers. Light industry consisted mainly of repair and construction “workshops” and crafts.

Unlike in other Third World countries with a large pool of labor, the proximity to the Persian Gulf’s oil economies drove wage levels up. Roughly a third of adult males were absent for at least a year or two at a time during the oil-boom decade (1974–84). The North imported not only teachers and health professionals but construction and hotel workers. While planners and international experts were initially optimistic about the investment potential of remittances, the class that benefited most from laissez-faire were Northern-based moneychangers and importers, middlemen to the migration-and-consumption cycle. The North’s open import markets attracted a commercial bourgeoisie from the lower Red Sea region, resulting in a predominance of service sector investments. Those with cash to invest—local traders, North Yemeni migrants to the Gulf, and entrepreneurs from Aden, Asmara, Djibouti or Mombasa—were lured to the North’s currency, real estate and import markets, where they profited from the hefty share of remittances spent on consumer goods.

Extraordinarily unfettered currency and import markets worked better for the YAR during the boom than the bust cycle. Global recession and depressed oil rents slashed remittance and aid levels, undermining, postponing or eliminating private and public projects by the thousands. The Yemeni riyal, having been kept artificially high at a uniform rate of 4.5 riyals to the dollar for over a decade (stimulating imports), plummeted to 18 to the dollar in the winter of 1986–87. Facing balance of payments and currency reserve crises from 1982 onward, Sana‘a temporarily banned all imports, blocked rampant smuggling, reformed and enforced tax codes and, in late 1986, took over currency markets and halted new investment projects. The secondhand bonanza in the North was gone, and with it the “hands-off” policy of economic non-management.

Ideologies differed from plans, and plans from outcomes. At best, the North’s capitalist orientation and the South’s socialism represented tendencies or goals, for both were really “mixed” economies.

The relative contribution of private and public capital can be measured in several ways. The North experienced a trend during the oil boom away from private capital formation toward public investment. In 1975, the private sector provided two-thirds and the state only one-third, but these proportions were reversed by 1982. By 1987, the North Yemen government financed three-quarters of investments in agriculture, fisheries, transport and communications, and nearly all utilities and mining development—amounting to two-thirds of all investment. Individuals funded most new construction, trade and hotel business, and 70 percent of manufacturing. Private investors’ preference for real estate speculation over agricultural production was particularly disconcerting to planners; whereas overall growth was a healthy 6.6 percent, in agriculture it was only 2.4 percent.

Nor was the PDRY ever an entirely state-owned economy. The nationalizations of 1969 affected foreign financial, trade and services businesses. Between 1973 and 1976, consolidation of state and joint industrial ventures continued, reducing the contribution of private domestic firms to industrial production from 51 percent to 38 percent, and the contribution of foreign firms from 36 percent to 10 percent. In fishing, however, foreign investors replaced some cooperative production. By 1976, private domestic and foreign firms held about 40 percent of the construction market, and local private transportation had over half the market. Cooperatives were credited with 71 percent of agricultural output, and the state with the rest, but livestock production was over 90 percent private. This was as “socialist” as the South got.

In Aden’s plan for 1981–85 targets for private investments increased, and during the first three years of the plan private-sector participation exceeded expectations by 8 percent, mostly in agriculture and local private fishing. The 1988 census reported that of nearly 35,000 establishments, 75 percent were private, 21 percent governmental, and the remainder cooperative or joint ventures. Just over a quarter of the work force was in the government sector.

All these figures are estimates that probably understate subsistence, smuggling and some informal trade. Cumulatively the evidence is sufficient to conclude that state and private sectors each played significant roles in both economies. There is little sign of sharp contrasts between centralized public ownership in the South and private enterprise in the North. Although their revolutions committed them to divergent paths, 20 years of practice produced convergent patterns. The explanation lies in the development projects supported by foreign donors.

Before the first Yemeni oil discovery in 1984, Yemen depended on aid rather than foreign companies for capital investment. International “soft” loans to the public sector represented the largest single source of new capital formation between 1970 and 1990. International companies participated either as contractors on donor-financed or nationalized state projects, where they earned profits but committed no capital, or as minority partners in public enterprises, to which they brought both capital and expertise. Once the oil industry began to take off, foreign private and public firms competed for roles in Yemen as contractors, partners and investors.

The foreign-owned private sector in the PDRY was limited. BP and Cable & Wireless did contract work for state corporations. BP, Mobil and a joint Yemeni-Kuwaiti company supplied petroleum. Planners spoke of foreign firms as a source of capital for development, and a few Arab, Asian and Eastern European firms entered the market.

In the North, the Arab world’s most liberal foreign investment policies attracted only a few foreign ventures, which raised much of their capital locally. Canada Dry, Ramada and Sheraton were the most visible; since the hotels imported their own staffs, only the locally owned bottler was a source of significant jobs. Other companies bought shares of Yemeni public corporations: A subsidiary of British Rothman had a 25 percent partnership and five expatriate employees in the National Tobacco & Matches Company, and the Saudi al-Ahli Commercial Bank and Bank of America together owned 45 percent of the International Bank of Yemen. Citibank found an economy where two-thirds of the cash circulated outside the formal banking system to be an unprofitable market. Scores of American, Arab, Asian and European contractors were active with donor projects: In roads, for instance, American and European engineers, Lebanese contractors, and South Korean and Chinese work forces (cheaper and more skilled than Yemenis) were not unusual.

By the 1980s, the overall patterns of external financing in the two Yemens were remarkably similar. For more than a decade, the West and the conservative states of the Peninsula had shunned the South while the Soviet Union, its allies, China, and radical Arab regimes were the main benefactors of both North and South. The global and regional multilateral agencies did work with the South, however, led by the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA). After 1980 the easing of tensions on the Peninsula prompted Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Abu Dhabi to offer assistance; by the middle of the decade, Arab funds surpassed assistance from socialist countries. In North Yemen the Arab oil monarchies were the most visible donors in the 1970s, and the IDA exercised the most influence in economic policy. North Yemen’s development assistance peaked in about 1981 at over $1 billion, and declined to half that amount in 1985 and to less than $100 million in 1988.

By that time, both countries relied on a similar list of donors and creditors. Grants were normally limited to small-scale technical assistance programs from the UN or European donors, or showy “gifts” from wealthy Gulf monarchs. Most new capital formation came from “soft” loans with low-interest charges and long repayment schedules. Thus debts accumulated against the accounts of international benefactors roughly in proportion to the amount of aid provided. The extent of polarization between “socialist” and “capitalist” trends was mitigated by the fact of Arab, IDA, Soviet, Chinese and European loans for both development programs. Infrastructural projects were the bedrock of government development investment. Bilateral donors chose their own design, engineering and construction firms, and global and Arab multilaterals applied the World Bank bids and tender system.