Some optimists—I confess that in 1993, while on a Fulbright fellowship at Sana‘a University, I was one—anticipated that Yemeni unity would introduce a more viable economy with a more democratic political system. As it happened, Yemeni unification all but coincided with the Iraqi invasion and annexation of Kuwait in the summer of 1990 that, in turn, prompted a massive multilateral military operation known as Desert Storm. Kuwait’s occupation and liberation constituted a turning point in the history of the Peninsula for many reasons. For the monarchies of the Gulf, it marked a new era for the Carter Doctrine and a deepening American role in guaranteeing their longevity. For people in Yemen, it precipitated a deep economic crisis fueled by losses of both remittances and foreign aid. Comparatively free and fair elections in 1993, however free-wheeling and reflective of popular and elite demands for democratization, did not lead to a viable power-sharing agreement by two former ruling parties. Instead, within 12 months, Yemen became a case of “from ballot box to bullets.”

It has been downhill ever since.

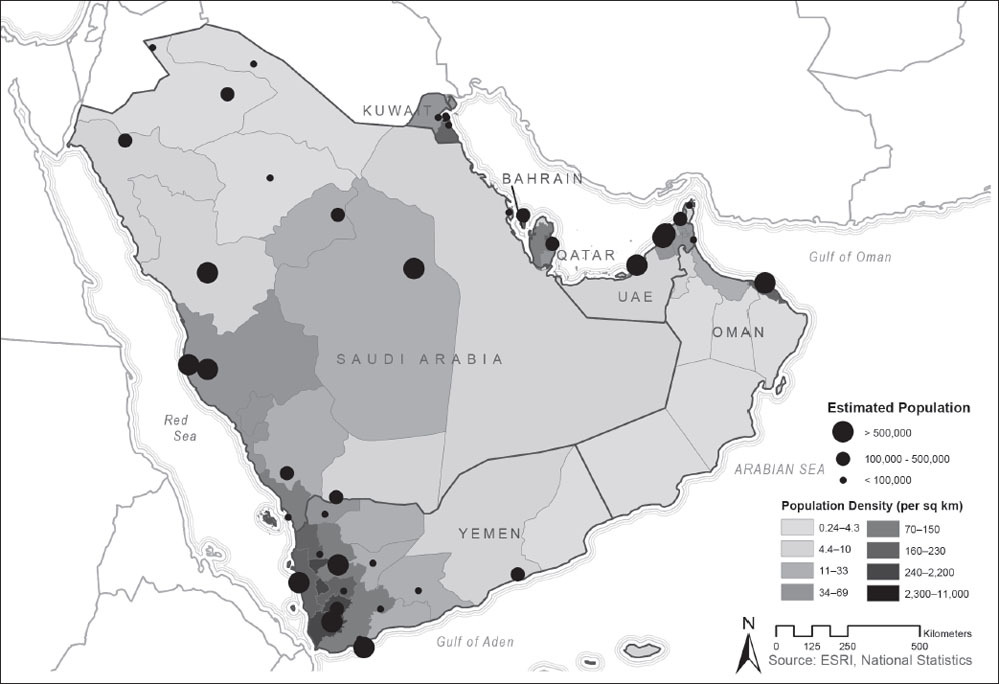

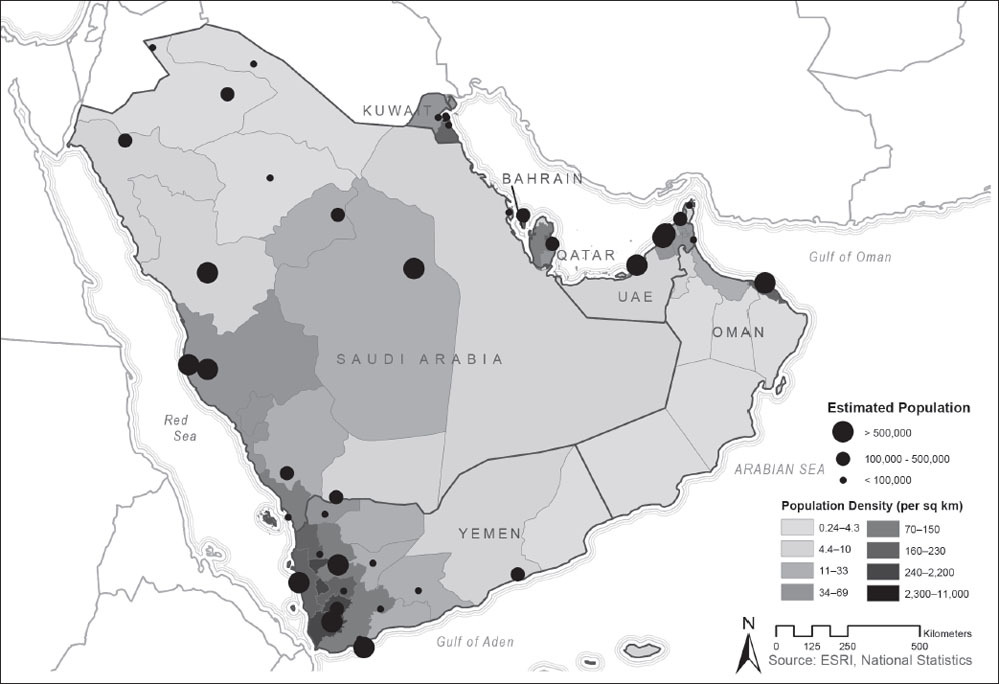

Map 3: Arabian Peninsula Population Density by Governorate and Major Cities by Population. (2014 data)

Produced by the Spatial Analysis Lab, University of Richmond

On May 22, 1990, the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (or South Yemen) and the Yemen Arab Republic joined to become the Republic of Yemen. […] Unity offered beneficial economies of scale in oil, power, administrative apparatus and tourism. It made political sense, too, reflecting the view of most Yemenis that the division into separate countries was artificial and imposed.

Formal unification heralded unprecedented pluralism and political opening. Televised debates in Parliament, dominated by the former ruling parties of the YAR and the PDRY, the General People’s Congress and the Yemeni Socialist Party, exposed bureaucratic corruption. Some three dozen new parties, of Nasserist, Baathist, liberal and religious orientations, began publishing newspapers and organizing for the May 1992 elections. Sana‘a University students demonstrated to replace national security police with student workers as campus guards. Military checkpoints virtually disappeared from Sana‘a, Aden, and the highway between them. In June and July of 1990, the mood was like that in Prague.

For all its popularity, Yemeni unification is anathema to Saudi Arabia. Although the YAR’s more conservative social, economic and political system appeared to dominate the new union, a unified Yemen of 13 or 14 million people posed a potential military threat, the Saudis felt, and its relative freedom of press, assembly and participation, including women’s participation, could set a dangerous example. Riyadh tersely congratulated the new republic, but covertly subsidized an opposition “reform” party of conservative tribes and fundamentalists.

Washington has traditionally dealt with North Yemen through Riyadh. Sana‘a got a modest $30 million or so annually in US development assistance. The PDRY was on the State Department’s list of “terrorist states.” Economic plans of the unified state called for freer trade and investment, and Soviet influence seemed on the wane. When ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih became the first Yemeni president to visit Washington in January 1990, two months after being designated to lead the future unified state, the [George H.W.] Bush administration approved $50 million in trade credits. YAR ambassador Muhsin al-‘Ayni stayed on in Washington, while the PDRY’s ‘Abdallah al-Ashtal remained as the new country’s UN delegate.

It was against the backdrop of this most important event in its recent history that Yemen responded to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Initially opinion was divided, but the balance shifted after Saddam Hussein, in his first major speech of the crisis, declared that Iraq had been inspired by the Yemeni example to pursue Arab unity by erasing colonial boundaries, and Saudi commentators lambasted Sana‘a for refusing to commit troops to the Kingdom’s defense. The Saudi request for US troops to confront Iraq prompted extraordinary protest demonstrations, and the consensus at many qat chews shifted decisively against Saudi Arabia. At the same time, pro-Saudi elements formed a Committee for the Defense of the Rights of Kuwait.

Mindful of both the public mood and longer-term interest in maintaining ties with the West and the Gulf, the government declared and held to a policy of neutrality. The Salih regime condemned the invasion, hostage taking and annexation, but did not support sanctions or use of force resolutions. UN representative al-Ashtal became the Security Council’s most prominent, consistent advocate for diplomacy.

The al-Saud took this neutrality as an affront. They cut aid in August. Next, they summarily revoked special residence and working privileges for over a million of the Yemenis in the Kingdom, life-long residents as well as short-term sojourners, forcing the majority to sell what they could at distressed prices and head south.

The sudden suspension of Saudi, Kuwaiti and Iraqi aid, the embargo of Iraqi oil shipments, the collapse of tourism and the decline in regional commerce cost Yemen nearly $2 billion in 1990, although a sudden infusion of migrants’ remittances cushioned the blow. While ministries struggled to pay faculty and health workers’ salaries previously financed from the Gulf, investment plans were scaled back, the riyal’s value dropped, prices rose sharply, and a half-million returnees camped outside Sana‘a.

Yemen’s refusal to join the coalition caused the deepest rift in Washington-Sana‘a relations since June 1967, but it also captured US attention. Secretary of State James Baker visited Sana‘a but failed to persuade the government to join the US-Saudi axis. President ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih repeated Yemen’s condemnation of Iraq’s invasion but observed that intervention by a massive multinational force was liable to “destabilize the entire region.”

American dependents—the Peace Corps, the US Agency for International Development (USAID), the US Information Agency—their European counterparts and business people gradually evacuated. Once the war began, the remaining 20 US diplomats and Marines moved into the embassy, and oil industry employees stayed off the streets. Yemeni media now carried Baghdad’s war coverage, along with denunciations of Voice of America and the BBC. After some demonstrations, and then a calm, someone threw grenades at the Sana‘a International School, there were small explosions at several embassies, and the heavily fortified US compound came under machine-gun fire from a passing car.

News of the US bombing of a Baghdad shelter full of civilians and of the ground assault politicized Sana‘a as never before. While the Arab League’s minority anti-war faction met at the Haddah Ramada, Tahrir Square overflowed with tens of thousands of enraged students and expelled migrants.

In the confluence of these events—a new nationalism, sudden lifting of political constraints, a war jeopardizing national and individual well-being, and a leading role at the UN—Yemenis and their government feel they have found a political voice. Popular slogans against the war and the Gulf monarchies have helped legitimize a regime which, in turn, tried to play a mediating role in the Arab League and the Security Council. Saudi and US “punishment” has so far only heightened a sense of nationalist self-righteousness. This will deepen if Yemen and other poor Arab states that declined to back the war are forced to pay.

With its moderate climate and terraced highlands, Yemen is agriculturally the most productive part of the Arabian Peninsula. Yet people, not crops, have been Yemen’s major export. Migrants from the former North and South Yemen are scattered throughout the world. During the last 20 years, the majority of Yemeni migrants have gone to neighboring oil states. With up to 30 percent of adult men abroad at a time, migration affected virtually every household. The earnings of the roughly 1.25 million expatriates, coupled with heavy foreign assistance, fueled the region’s socioeconomic transformation, particularly in the north. This era of prosperity ended abruptly when Iraq invaded Kuwait in early August 1990.

[…]

The invasion immediately forced approximately 45,000 Yemenis and dependents to flee Kuwait and Iraq. When Yemen subsequently took a neutral stance and refused to support the Saudi invitation to US forces, Riyadh rescinded the special status that had allowed Yemenis to enter Saudi Arabia without the work permits and guarantees required of other migrants. Between 800,000 and 1 million people were forced home as a result. Some 2,000 Yemenis were forced to leave Qatar, Bahrain and the UAE. This represented a population increase of about 8 percent. Yemen’s ambassador to the United Nations, ‘Abdallah al-Ashtal, compares it to the United States suddenly taking in 30 million people. For the fledgling, financially strapped government of Yemen, the crisis was compounded by the disruption of normal relations. Sana‘a claimed it lost $1.7 billion in foreign assistance (primarily from Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iraq), oil supplies, foreign trade and workers’ remittances. Lost remittances were estimated at only $400 million, although in 1987 remittances for the two Yemens amounted to $1.06 billion.

Yemen’s export of workers has been a major source of foreign exchange, and remittances a key factor in socioeconomic modernization of the country. For all Yemenis, migration to Saudi Arabia was easy. They could obtain a visa at any port of entry, often without a passport; they did not require a sponsor for work or residence permits, and could own businesses.

Many migrants used their savings to supplement household incomes in Yemen. With about a quarter of adult men from the north and a third from the south abroad, their families grew dependent on remittances. Both national economies came to rely on migrants’ earnings, which accounted for as much as 20 percent of gross domestic product in the north and 50 percent in the south.

In the north, remittances financed a construction boom and the rapid expansion of petty commerce. The easy escape of excess labor opened positions for, and raised wages of, workers at home. Migration from South Yemen, rather than being a safety valve for excess labor and a means of acquiring skills, led to labor shortages and skill deficits. As a result, Aden severely restricted migration after 1973. Those working abroad became, in essence, permanent migrants. Despite government attempts to encourage investment, most money and acquired skills remained abroad. Only since unification and their return have migrants from the south begun spending their savings as had those in the north.

The typical migrant was a single man who stayed abroad two to five years. By the mid-1980s, though, many had brought their families to live with them in Saudi Arabia. In 1990, an estimated one-third of the 285,000 migrant workers in Saudi Arabia were accompanied by their families. The decision to have their families join them seems to have coincided with migrants’ shifting from the volatile and competitive construction sector to more secure positions in the services sector.

Yemen’s position in the Gulf crisis may have been only one factor in the Saudi decision to expel the migrants. The Saudis were angry with Yemen’s unification and, some suggest, sought to undermine the new government, sensing that the unification dynamics made Yemeni migrants potentially more threatening to Saudi internal security.

Another speculative explanation derives from changes in the Saudi economy. In the 1980s, many migrants moved into low-status service positions—taxi drivers, storekeepers, bakers, small business contractors and farm workers—once held by Saudis. Yemenis also began to bring their families, making themselves semi-permanent features on the Saudi economic landscape. As oil revenues declined, the Saudi labor market shrank. At the same time, the number of Saudi vocational school graduates increased, but desirable service positions were no longer readily available. One way to create openings was to eliminate the Yemeni competitive advantage. This was apparently behind the Saudi attempt in the late 1980s to implement a law requiring unincorporated businesses to be Saudi-owned. North Yemeni president ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih interceded then—to secure a special exclusion for Yemenis. This exclusion was canceled on September 19, 1990, and the status of Yemenis reverted to that of other migrants. They were given 30 days to find a Saudi guarantor or majority partner for businesses, and to obtain residence permits. The deadline was subsequently extended for another 30 days.

An unknown but probably small number did arrange to comply with the new regulations. Many, perhaps the majority, seem not to have expended much effort to do so. Some were motivated by nationalist feelings; others felt they could not satisfy the requirements. The result was a rush to liquidate assets, pack or sell possessions, and prepare to return to Yemen.

Those Yemenis suffering the greatest financial loss and dislocation were those forced to flee Iraq and Kuwait, leaving everything behind. Most migrants in Kuwait were native to Hadramawt, and many returned there.

The losses of returnees from Saudi Arabia were less severe. Although there were reports that the Saudis had detained and tortured hundreds of Yemenis, no migrants with whom I spoke reported being mistreated. Most returnees, however, did accuse those who bought their property of profiting from their expulsion. Many were forced to sell their property and possessions at absurdly low prices. Hammoud Husayn, a migrant for over 30 years, owned three rental properties in Riyadh that he valued at 275,000 Saudi riyals. He was able to sell them for only 40,000 riyals. Many sellers received a fraction of their invested capital, especially those with tea shops, restaurants or bakeries. Sana‘a estimates the returnees lost $7.9 billion in assets.

For Yemen, the greatest impact came from trying to meet the needs of up to 40,000 returning migrants a day. The government sent trucks to the border to transfer returnees and their property to receiving points in Yemen. Customs rules were relaxed so most possessions were duty-free. To defray costs and aid in resettlement, government and private-sector employees were ordered to contribute one day’s pay per month for three months to a resettlement fund.

The government pledged to create jobs and provide housing, schools and health centers. The estimated cost of these programs was $245 million, but funds from the World Bank, USAID, Germany, the UN and Yemen amounted to only $60 million. Sana‘a made available 60 million Yemeni riyals. Promised programs did not get off the ground. Preliminary funds provided and administered by the UN Development Program set up an Emergency Recovery Program but not much else.

Returnees found more obstacles to resettling in Yemen than they anticipated. Most single returnees were accepted in the homes of kin, as were many returning highland families. Some 11.5 percent owned homes in Yemen. Some returnees with dependents needed assistance. The government provided temporary housing in schools and hospitals. In the hardest-hit areas, Hudayda and Aden, vacant lands were transformed into tent cities. The population of Hudayda tripled to more than 500,000 people. According to the returnees, probably between 75,000 and 100,000 families were directed to camps, where they remain.

Why did hundreds of thousands end up in camps? Many returnees, especially those from the Tihama area along the Red Sea coast, had been abroad more than ten years. They had lived for years in urban areas and were unwilling to return to the countryside.

A second factor is the returnees’ status, a key element in Yemeni culture. According to some Yemeni social scientists, many migrants were from the lowest-status group known as the akhdam (literally “servant”). Predominately from Tihama, akhdam are generally described as having African heritage. They traditionally performed tasks like street sweeping that others refused. For them, emigration was a way to shed this culturally imposed status. Having severed ties to their birthplaces intentionally, these returnees were unwilling to return to villages where their ancestry was known.

Finally, Yemen suffers from a housing shortage. This is most severe in urban areas of the former South Yemen. The 11.5 percent of migrants who owned houses they could return to in turn forced their tenants into the housing market. Some 32 percent of returnees found housing, often temporarily with kin. The majority of returnees, 56.5 percent, having limited resources and confronted with skyrocketing rents, had no place to go.

In Yemeni culture, family is central and custom demands that kin support each other. In Tihama, though, many returnees had long ago severed any such connections. In Aden, there was simply no space; some men were able to house family members with kin but had to find other quarters for themselves. People reported that their relatives’ homes were overcrowded and life stressful. Camps were the alternative.

Repatriation brought $1.36 billion to Yemen, but the remittance flow slowed dramatically. Once the returnees’ resources were exhausted, the ripple effects were many. The lack of foreign exchange drove inflation up.

Migration had created a relative labor shortage and high wages, even for day laborers. The return reversed this trend. Skilled returnees displaced less-skilled workers. The influx of returnees drove unemployment from around 4 percent to 25 percent, with 40 percent unemployment among former migrants.

Peddling and begging proliferated. In addition to adults, scores of children spend their days on the street instead of in schools, helping to support their families. Shortages and inflation pushed food prices up by more than 200 percent between 1990 and 1992. The United Nations Development Program reported the number of people living in poverty rose from 15 to 35 percent. (The official poverty line is a family income of 3,000 Yemeni riyals per month—$250 at the official exchange rate, but in reality less than $100—an amount that would permit only the most modest existence even if one had housing.) Overcrowded conditions and malnutrition became common.

The crisis is nationwide. In October 1991, middle-class protests erupted in Sana‘a. Frustrated by high prices, lack of jobs and increasing poverty, demonstrations again broke out in mid-December 1992 in Ta‘iz, where thousands reportedly participated in looting and burning. The riots spread to Sana‘a, where they lasted four days. Smaller demonstrations occurred in Hudayda, al-Bayda and Ibb; unrest spread even to small towns. More than 60 people were killed, hundreds injured and thousands arrested. The government reportedly brought 8,000 armed tribesmen into the capital to maintain power.

[…]

There was talk of job creation schemes such as road and agricultural projects, but this has not happened. Whether it was lack of funds and resources, lack of planning or simply lack of commitment, the government has not done much to alleviate the crisis. In the end most returnees have had to rely on whatever assistance kin and friends have been able to provide.

The Yemeni parliamentary election of April 27, 1993, marks a watershed for the Arabian Peninsula. The multiparty contest for 301 constituency-based seats, and the period of unfettered public debate and discussion that preceded it, represents the advent of organized mass politics in a region where political power has long remained a closely held family affair.

[…]

Yemen’s commitment to elections accompanied the unification agreement between ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih, president of the Yemen Arab Republic, and ‘Ali Salim al-Bayd, leader of the ruling party in the People’s Democratic Republic. Following formal unification on May 22, 1990, a five-member Presidential Council headed by Salih held executive power, and the two former parliaments were combined in a unified Chamber of Deputies. Under a constitution approved by national referendum in May 1991, political parties organized openly and most restrictions on association, expression and movement were lifted. The 1991 referendum specified that the elections be held within 30 months of unification, but a combination of technical problems, procrastination and conflicts between “‘Ali and ‘Ali” (Salih and al-Bayd) postponed polling beyond the November 1992 deadline.

Arab leaders have promised free elections in the past and not delivered. What made Salih and al-Bayd—neither of whose personal histories indicates a commitment to political liberalism—follow through? The answer lies in societal pressures which took different forms: mass conferences, strikes, demonstrations, political organizations, press commentaries, academic symposia and maqiyal or “salons.”

Prior to the elections, a series of mass conferences provided outlets for articulate opposition elements. A nine-day Talahum (Cohesion) Conference in December 1991 gathered some 10,000 men; although its banner was the Bakil tribal confederation, urban intellectuals were among the organizers and authors of a 33-point resolution calling for judicial independence, strengthening of representative parliamentary and local bodies, fiscal restraint and management, revitalization of agricultural and services cooperatives, an independent media, environmental protection, free elections within the mandated time frame, peaceful resolution of tribal conflicts and other reforms. At least seven other tribe-based but civic-oriented mass conferences in 1992 each issued written demands for the rule of law, pluralism, economic development and local autonomy. The Saba’ (Sheba) Conference of Bakil and Madhaj tribes elected a council of trustees, a council of social reform and follow-up committees to ensure institutional continuity.

This activity culminated with a national conference of representatives of the smaller center and left parties and political organizations, led by ‘Umar al-Jawi. This time, the two ruling parties strove to delay, discourage, coopt and eventually offset what promised to be a major event by holding a simultaneous counter-conference and by arranging the ouster of their opponents from the Sana‘a Cultural Center to the local Sheraton. Well publicized in the opposition press but ignored by the official media, the center-left conference criticized delayed preparations for the elections and the government’s reckless printing of money, and proposed a code of political conduct for political parties. The Ta‘iz Conference in November 1992, headed by ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Jifri , went even further in attracting faculty, journalists and professionals; challenging Ta‘iz’s governor; constituting steering and work councils; and articulating explicit demands for civic and human rights, local elections and improved local services. Not to be outdone, the Islah organized a 4,000-strong Unity and Peace Conference in December under the slogan “The Qur’an and the Sunna Supersede the Constitution and the Law.”

These conferences, both tribal and urban-based, involving tens of thousands of people, were among the transition period’s most important political developments. In response, the regime felt compelled to adopt its own code of political conduct, dismiss the Ta‘iz governor, accept the principle of local elections and adopt a rhetoric of electoral rights. There were also several outbursts of popular frustration, most notably in December 1992. Outrage with the collapse of the value of the riyal, inadequate services, mounting unemployment, government corruption and postponement of the elections erupted in mass demonstrations against both the state and private merchants in all major cities. Along with strikes and threatened strikes by groups ranging from garbage collectors to judges, the near-riots reminded the government of the power of popular wrath.

On a smaller scale but a more institutionalized basis, numerous independent political organizations emerged. The Committee for the Defense of Human Rights and Liberties, established by liberal university professors, initiated the National Committee for Free Elections, in turn spurring the formation of other electoral NGOs. Although they failed on their own terms to guarantee the integrity of the balloting process, they did perform a modest watchdog function and met again after the elections to prepare for the next round. Syndicates, charities and interest groups have also been increasingly active in the political process.

The press is also significant within the political arena. More than 100 partisan and independent newspapers and magazines, mostly founded since 1990, covered these events. Although the government daily, al-Thawra, and state-run television and radio tend to dominate news coverage, a number of opposition weeklies have a strong readership among the literate, urban, politically active population: Sawt al-‘Ummal (Voice of the Workers), based in Aden, has the largest circulation of any paper. Party organs, including al-Ra’y, al-Tashih, al-Sahwa and others, provide critical commentary and information about opposition conferences and independent organizations. There has emerged a press corps of scores of men and several dozen women who more and more approximate a fourth estate, conducting interviews, attending Parliament, asking critical questions at press conferences, testing the limits of press law and defending one another against lawsuits.

Related to the mass conferences, political organizing and press activity was a trend toward academic symposia on topics such as the constitutional amendments, administrative decentralization, municipal services and the campaign experience of women candidates. Typically inviting members of each party and independent specialists, such symposia, virtually unheard of in the old North or South Yemen, provided fora for discussion, debate and refinement of ideas which were then reported in the opposition press.

More frequent and informal is an updated variation on the male qat session, or maqiyal, which approximates the “salons” of nineteenth-century Europe. Nowadays these customarily informal social gatherings may elect a chair, select a topic, establish rules of order and hold organized political discussion on topics ranging from relations with the Gulf to women’s rights to exchange rate policy.

Collectively, these civic activities applied considerable pressure on the regime to fulfill its promises, abide by a code of conduct, address its critics and respect political pluralism. Several Yemeni intellectuals have criticized international observers and reporters for presenting an unduly positive picture of the electoral experience, and many participants in the conferences and seminars are quite cynical about their own influence, insisting that they have been marginalized from the political process. By the same token, it is difficult to imagine the events of the past year taking place had they been passive.

Candidate registration for Yemen’s first-ever multiparty elections opened on March 29 in a climate of lively polemics against the president’s party, the General People’s Congress (GPC). The GPC’s permanent committee had approved its electoral program on March 27. That same evening it appropriated an hour of television and radio time to present its proposals, shoving aside the law which stipulated that access to the official media was subject to the provisions of the Supreme Elections Committee (SEC) in the framework of equality between the parties. The head of the SEC’s information subcommittee immediately distributed a letter condemning this violation and threatened to resign. The GPC subsequently felt compelled to play by the rules.

The biggest campaign surprise of the week-long registration period was the huge number of independent candidates—3,246 out of the 4,602 who registered—made possible by an electoral law that required candidates only to be literate, of good moral standing, religiously observant and not to have been convicted of any crime. A requirement to submit 300 voter signatures from the electoral district was dropped from the law.

The high number of independent candidates was the result of several factors. Local notables were testing their appeal. Some enlisted only in order to negotiate a rewarding withdrawal. The big parties—the GPC, the Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP) and the Islah—hoped that the distribution of votes among independents would benefit their candidates, who were supported by activists and enjoyed proximity to power. The two ruling parties also had to face candidates originally from their own ranks who ran as independents because the parties had nominated others or because as civil servants and members of the armed forces they could not have a formal party affiliation.

In putting together their slate, the GPC looked for persons well-rooted in their communities, with party affiliation taking second place. Many tribal leaders, of course, but also big merchants and high officials, ran in urban centers if they were not certain of their support at home. In the South, the GPC was able to enjoy the support of partisans of ‘Ali Nasir Muhammad, the former PDRY president ousted in 1986, by presenting a number of their candidates under its banner. Similarly, the YSP was able to count on its long-standing presence in the North through the old National Democratic Front. The YSP’s superior internal organization and activist tradition accounted for the presence among its candidates of a large number of its Central Committee members and government ministers.

The candidates of the Islah were divided between local notables, mainly sheikhs linked to Sheikh ‘Abdallah, and university-educated Islamists in the cities. Al-Haqq’s list of 67 candidates was a veritable who’s who of the sayyid families. The candidates of the League of the Sons of Yemen represented some of the most prestigious sheikhly families of Shabwa and Hadramawt. In addition to the three main parties, the League and the Baath were the only parties to put forward candidates in almost all the provinces.

Most of the parties formulated platforms which, if they had at least ten candidates, they could present on radio and TV (twice for 20 minutes) and in the official daily, al-Thawra. The GPC’s program detailed, sector after sector, all types of measures that attested to apparently liberal and democratic convictions. The YSP adopted a social-democratic line and presented itself as the champion of democracy, modernization and order. The YSP program’s priorities were to establish order and security in the country by suppressing violence and moving swiftly against those responsible for corruption via an independent judiciary. In the social domain, the YSP proposed to improve medical care, develop public housing and improve access to education. The party catered to those who accused them of irreligiosity by calling for an Islamic university which, the Socialists claimed, would be a training center for clerics under the rubric of tolerance. Like the GPC, the YSP called for decentralization and the holding of local elections.

The Islah program focused on the idea that Islam should again have the central role that, according to the party, it had lost in Yemen. Its main slogan—“The Qur’an and the Sunna Supersede the Constitution and the Law”—was manifested in various propositions for reform. So as to reassure its critics, the Islah affirmed its commitment to a peaceful transfer of power and “consultative democracy,” but it refrained from mentioning a multiparty system in its program.

The other party programs presented variations on the same key themes: denunciation of corruption, a call for strengthening the judiciary and unification of the two armies and security systems, development of services in the rural areas, and an affirmation of support for the principle of peaceful transfer of power.

The 10-day campaign officially began on April 17. Party and candidate newspapers and broadsheets proliferated, and the walls in all the large towns and even in villages were covered with posters. The Islah had already before the start of the campaign pasted up its many slogans.

Almost all the GPC’s posters carried a picture of President ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih. The independent candidates satisfied themselves mostly with posters carrying their picture and some key phrases from their program. These posters typically mentioned a person’s profession and featured the candidate’s favored attire: head covered or not, Western or traditional Yemeni dress. An independent candidate from Sana‘a, a professor of political science at the university who belonged to a sayyid family, had taken care to wear a jambiya, the curved dagger that signified his affiliation with the tribal world. A candidate from Marib showed his preferences by placing in the corner of his picture a small photograph of Saddam Hussein.

The law allowed for meetings in public spaces made available to the candidates, but it was only in large towns that huge gatherings took place. There were no debates between candidates except perhaps within neighborhoods.

In keeping with Yemeni custom, the period before the elections was marked by outpourings of generosity and hospitality on the part of the more affluent candidates. In the Jebel Yafa, in Lahij province just north of Aden, a Socialist minister candidate organized a daily banquet followed by a qat-chewing session in the late afternoon (qat generously provided). The total cost of organizing the campaign and election emptied state coffers and seriously aggravated the country’s liquidity crisis. In addition to their personal generosity and the energy of their poster pasters, the candidates from the ruling parties were able to count on the advantages offered by their control of local government. In the larger towns in particular, neighborhood chiefs, with their links to the security forces, were able to mobilize voters around their respective parties.

The day before the elections, the president and vice president addressed the voters, reminding them of the importance of the elections in closing off the period of transition and opening a new stage. The vice president took the occasion to renew offers to resume good relations with the Gulf countries. In a press conference a few days earlier, the GPC’s ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih and the YSP’s ‘Ali Salim al-Bayd had confirmed, a smile fleeting across their lips, that they intended to continue their collaboration after the elections, the results of which they undertook in advance to accept. The quiet confidence they exuded, even more than the withdrawal agreements, suggested the real stake of the elections: to measure the respective popularity of the three main parties that would comprise a coalition. The election results would determine the quotas of ministers of the parties in government, but there was hardly a question of a real transfer of power.

On the morning of April 27, all polling stations opened, a box for every 500 registered voters. Upon presenting their proof of registration, the voters received a sheet on which, in a booth if there was one, they wrote the name of the candidate of their choice. The voter then slid the sheet into the box and dipped his or her finger into ink, intended to prevent a return visit to the polls.

At first light, hundreds of voters began pushing their way into the centers. Many had to wait long hours. The turnout rate, not officially announced, was definitely more than 80 percent. A formidable military presence assured order throughout the day. In the polling stations, though, there were moments of disorder. In one place, women voters fed up with waiting forced themselves inside and cast a collective vote, some filling out a whole series of sheets for their illiterate friends in the presence of passive officials. Elsewhere soldiers at the booths filled out voting sheets for others that no one bothered to check. Multiple voting was made possible by the facility with which the ink could be washed off; more than once, a voter prepared to cast his vote only to discover that his registration number corresponded to that of someone who had already voted. Finally, the deployment of troops made it possible to modify the composition of the electorate of certain districts significantly and at the last moment.

Not even waiting for the vote count, the US Embassy issued a communiqué on the night of April 27 congratulating “the people and government of Yemen for the success of their first multi-party elections” and declaring that “the United States looks forward to working with the government to be formed as a result of these elections.” The official media never tired of quoting this and the commentaries of the Western media and of international observers and diplomats, even when the most serious incidents of fraud were taking place in the days of ballot counting. When the official results were announced on May 1, the GPC had won majorities in all the governorates in the North and three seats in the South. In the South, the YSP won an overwhelming victory, which could be interpreted as evidence of its popularity after two decades of Socialist power, but also as an indicator of an effective apparatus of control. In the southern province of Abyan, birthplace of ‘Ali Nasir Muhammad, the YSP took seven out of the eight seats, even though YSP relations with the former president have only recently begun to improve. The YSP did not elect any representatives in Sana‘a, but did well in al-Bayda and Ta‘iz provinces, even if the competition with the Nasserists in Ta‘iz allowed seats there to be picked up by the Islah and GPC. The two seats won by the YSP in the electoral district of the Sufyan tribe, in the heart of the Zaydi tribal area, and among the Bedouin of Marib, confirm the existence of a tribal challenge to the GPC that the YSP was able to exploit. But the commitment of these elected representatives to the entire YSP platform remains uncertain. Contrary to the GPC, the YSP can pride itself on a largely ideological vote. How else to explain the performance in Sana‘a and elsewhere in the North of little-known candidates originally from the South who nevertheless came away with encouraging results?

Although the Islah carried not a single seat in the South, it did well in several provinces there. It was only thanks to the withdrawal of the Socialist candidate in favor of the ‘Ali Nasir Muhammad faction of the GPC that the two parties were able to block the victory of the Islah’s candidate in Mukalla, the Hadramawt capital. This province has been a priority area for Islah proselytizing, with its proximity to Saudi Arabia and strong religious tradition.

Sheikh ‘Abdallah, who was a candidate in the province of Khamir, the Hashid capital north of Sana‘a, triumphed without difficulty; out of deference, the GPC and YSP ran no candidates against him. Al-Haqq was the only party to compete with him. One of his sons won under less glorious circumstances in Hajjah province, as his victory was offset by several deaths and the destruction, by rocket launcher, of the local Socialist headquarters.

The election results were less auspicious for the smaller parties: The Baath saved face with seven seats, one of which was taken by the son of its leader, the permanent deputy prime minister in charge of tribal affairs, Sheikh Mujahid Abu Shuwarib, who is also Islah leader Sheikh ‘Abdallah’s brother-in-law. Al-Haqq naturally carried its two seats in Sa‘dah province, the historical Zaydi stronghold. The Nasserists, who had had great hopes, could only join in the concert of complaints against fraud and ruling-party manipulations. The results of other parties were derisory, despite some very active campaigns.

The new Yemeni Chamber of Deputies remains in the hands of the large parties. The electoral struggle hardly helped the candidates representing new modernizing trends in Yemeni society. The notables prevailed, be they the great sheikhly families (al-Ahmar, Abu Shuwarib, Abu Ra’s, al-Shayif, al-Ruwayshan), the big entrepreneurs (Hayil Sa‘id and Thabit) or the new aristocracy in the South, the members of the YSP Central Committee. With only two women elected, the diversity of the Yemeni population is less well represented in the new chamber than in the old, which has lost several of its most voluble critics (al-Fusayyil and al-Sam‘i, for example).

The parties filed 113 challenges with the constitutional division of the Supreme Court. The three big parties decided, after a number of mutual accusations, to retract in a collective letter the complaints they had submitted against one another’s respective candidates, without even consulting their own membership. This locked in place the coalition in the making. Of the 20 cases remaining, the court ratified the initial results.

The various international observer groups gave their imprimatur to the results, which contrasted with the accusations leveled by the National Committee for Free Elections, a Yemeni NGO, and the smaller parties of the National Conference, which charged fraud on the part of the three big parties.

The fact that elections were held constitutes in itself a victory for a process of democratization that started after unification. Whatever one might say about the manner in which the elections took place, everyone sees this as a first step. The coalition government constitutes the best solution to maintaining political stability in the country, despite the reticence of some of the Socialists, like Jarallah ‘Umar, who had hoped that his party could regain its virginity as a member of the opposition.

The coalition, though, has left little by way of an opposition. The three big parties have made it practically impossible for opponents to enter the Chamber of Deputies (the Baath, with its seven seats, is very close to the GPC). Now that the opposition parties have been told to take a hike in the desert, they would be wise to hearken to the remark of ‘Umar al-Jawi, who lost his election bid in Aden, to “be strong in the streets, because we are not represented in Parliament.” (Al-Jawi, head of the Yemeni Union Rally and one of the most vocal critics of the ruling parties, was reputedly on President ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih’s list of people to defeat in the elections. The Socialist candidate won in his district.)

Local elections in the provinces may offer hope for the opposition. In the short term, the political agenda appears to be dominated by constitutional reform, which is supported for different reasons by all three coalition partners. The Islah wants to make the shari’a the sole source of legislation. The YSP and GPC want to alter the regime’s institutional architecture. Three years of experience have persuaded them to renounce the country’s collegial form of leadership—a Presidential Council appointed by the Chamber of Deputies. Now a vice president would be elected from a list approved by the National Assembly (YSP version) or appointed by the president (GPC version). The Assembly would consist of the current Chamber of Deputies augmented by the new Consultative Council, some of whose members would be appointed. Sheikh ‘Abdallah has already made clear his hostility to a second chamber, which might erode the prestige of the chamber over which he is currently speaker. (Many cited his selection to explain the adjustment of the Yemeni riyal vis-à-vis the dollar in May, as this would facilitate reconciliation with Saudi Arabia and the resumption of Gulf aid.) The opposition, for its part, condemned a project that would further strengthen the executive branch, while calling for a redistribution of power to the judiciary and legislative branches.

It is still too early to predict what Yemen will look like once these reforms have been adopted. It seems likely that the country will remain fixed on a path of “prudent democratization” that will not threaten the elites in power.

—Translated from the French by Joost Hiltermann

Artillery and bombs rather than innocent fireworks marked the fourth anniversary of Yemeni unity and the first anniversary of free parliamentary elections of the Arabian Peninsula. The fight between the armed forces under President ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih and those loyal to Vice President ‘Ali Salim al-Bayd was complicated by ideological, tribal and regional politics. In the end, though, it boiled down to both military leaderships’ rejection of pluralism and dialogue. Simply put, each side wanted its maximum domain: for the southerners, either a full half of the power in a unified government or an effectively independent administration of the south; and for the north’s Salih, control of the whole country, period. Not incidentally, given the acute state of economic collapse, both also had their eye on the Shabwa and Hadramawt oil fields.

When Salih and al-Bayd signed the unity pact in May 1990 on behalf of the Yemen Arab Republic and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, a number of critical issues—not least, how to merge the two separate militaries and security apparatuses—remained to be resolved “through the democratic process.” A year later, when the constitution was ratified in a public referendum, and three years later, when national parliamentary elections partially redistributed top posts, none of these matters had been dealt with.

The results of the April 1993 elections exacerbated the stalemate over how power would be shared and exercised. If there were still essentially two camps, the north’s now included not just the president’s political machine but also his effective ally, Islah, the party alliance of Islamists, tribal leaders and some prominent merchants headed by ‘Abdallah al-Ahmar, paramount sheikh of the Hashid confederation. Although al-Bayd and al-Ahmar signed a series of reconciliation agreements, in retrospect neither camp really intended to give up its army and security forces. The competition between them opened up political space for four years of pluralist politics whose most remarkable feature was a vibrant free press and dissenting opinion, formal and informal. But this competition became polarized, and the leaderships with their respective military commands resolved to remain in power separately rather than make the compromises that unity and democracy demanded.

The tribal basis of both military commands, especially Salih’s, got much critical public attention during the crisis leading up to the civil war. Sawt al-‘Ummal, the Aden-based Labor Federation weekly, first published the names of the 33 top officers in the northern army, who all happened to be from Sinhan. A pro-regime paper, 22 Mayu, ran a counter-list of 26 southern officers from Radfan and 29 from Dalaa. Al-Shura, a weekly published by a small opposition party, then printed the two lists side by side.

In a country of about 14 million people and (reputedly) 50 million guns, degeneration of the conflict along tribal lines was one gruesome potential scenario. To date, this has not happened. Tribal divisions created rifts within the two camps, not between them. The north’s more populous Bakil tribes resented the stranglehold on military command positions by officers from Salih’s Rashid subtribe of Sinhan and the selection of ‘Abdallah al-Ahmar as speaker of Parliament. To press demands for government reform, local economic development, and the arrest of high-profile swindlers, the Bakil imposed a “quarantine” against Rashid-owned petrol and Butagaz trucks entering Sana‘a in April.

Tribal tensions also overlapped with other issues in the south, where ‘Ali Nasir Muhammad and his supporters in Abyan lost out to politicians from the Hadramawt and officers from Radfan and Dalaa in 1986. In order to fan the embers of that dissension, Salih threatened in April to replace Prime Minister Abu Bakr al-‘Attas with ‘Ali Nasir, then still in exile. While most southerners closed ranks against the advance of Salih’s army, the tribes of Shawra offered no resistance when the northerners took Ataq.

Whereas the popular culture of Sana‘a exudes religious conservatism, Aden has a more relaxed, secular atmosphere. But this is not what the fight was about either. Salih did set the religious right against both northern leftists and the Socialists, helping to propel Islah’s Islamist ideologue ‘Abd al-Majid al-Zindani—opponent of unity, democracy and constitutionalism—into one of five seats on the ruling Presidential Council. In the lead-up to war, Salih addressed mosques while al-Zindani visited army camps. No amount of prayerful public posturing makes either Salih or Islah party head al-Ahmar into fundamentalists, however. Al-Zindani had actually reached a compromise with the YSP late last year on the wording of a constitutional amendment dealing with the place of shari’a in laws and legislation. Outside Aden, the south was no less conservative than the north. Religion was part of the rhetoric of war, but Yemenis were not fighting over religion’s role in politics and public life.

The extraordinarily open political climate of the past several years unfortunately also encouraged Salih and the YSP, each still in control of a broadcast station and a daily newspaper, to air their differences in an acrimonious “war of declarations.” Salih insisted on a presidency where he can appoint the vice president and all other influential positions. Al-Bayd wanted an independently elected, virtually co-equal president and vice president. Salih’s cadre opposed independent local government; YSP Deputy Secretary-General Salim Salih Muhammad called for “confederation.” Salih was happy to merge the armies under his relatives’ command, and spoke with a straight face of the army as a “democratic” institution; the south invited “reorganization” and “appointment by merit.” The YSP, which lost over 100 cadre to assassination during the unity period, called for “law and order,” which it claimed to have provided in the former PDRY.

The public often sympathized with al-Bayd’s positions but not his tactics. After a private visit to the United States in August 1993, instead of returning to Sana‘a he went to Aden and issued “18 points” summarizing his demands. These served as the basis for some bargaining; negotiators for the president’s GPC claimed they made significant concessions. One agreement concerned the composition of the five-man Presidential Council: two from each of the ruling parties, and one from Islah. But on October 29, as compromise seemed at hand, an attack on al-Bayd’s sons and nephew scuttled the whole deal. He subsequently refused to take the oath of office, effectively depriving the country of a constitutional executive.

The elaborate electoral process to compose a new government that would in turn resolve constitutional, judicial and policy matters was unraveling. The Presidential Council, the cabinet and Parliament, all composed of the three-party coalition, were in deep constitutional and political crisis.

A lot of prominent Yemenis wanted unity and pluralism to succeed. Two leading northern figures took it upon themselves to bring together a group of personalities and then sell the feuding cliques on the idea. Mujahid Abu Shuwarib, for all his complicated past Baath, GPC and Hashid connections, was consistently considered as an “independent personality” and “acceptable to both sides.” Sinan Abu Luhum, also a veteran of the 1960s struggle to establish the republic and subsequent political contests, rose during the dialogue efforts from among many competing Bakil sheikhs to a much-admired position of mediator. Backed by an impressive array of past Yemeni leaders, exiled figures and prominent nationalists, they proposed a National Dialogue Committee of Political Forces to discuss the YSP’s 18 points, the conditions of Salih’s camp, proposals from a recently formed Opposition Coalition, resolutions of dozens of civic meetings, and recommendations of lawyers and intellectuals. The new committee was to consist of five representatives each from the three ruling parties (who sent their most thoughtful and reasonable spokesmen), five from a recently formed Confederation of National Forces, leaders of the Opposition Coalition and smaller parties, and “independent social personalities.” All significant factions and regions were represented.

After virtually continuous meetings for three months, 30 respected men produced in early 1994 a Document (wathiqa) of Contract and Agreement spelling out comprehensive reforms. Among the most important of these were delineation and limitation of presidential and vice presidential power; depoliticization, merger and redeployment of military and security forces, starting with the removal of checkpoints from cities and highways; administrative and financial decentralization to elected local governments, starting with development budgets; empowerment of an independent judiciary to enforce the letter of the law, starting with the arrest of assassins; election of an upper house of Parliament modeled on the US Senate; stricter auditing procedures; abolition of the ministry of information; and a comprehensive list of other reforms.

Public response to this idealistic document was overwhelmingly positive. College professors called it a “social contract;” their students said the president would now be like the queen of England; a taxi driver in Sana‘a chuckled that the Gulf monarchies would be furious. Small wonder that the two leaderships were loath to sign a document that would, if implemented, force them to give up direct control of their armies, their purse strings and their cronies. Within hours after Salih, al-Bayd and al-Ahmar signed the agreement in Amman, Jordan, on February 20, a skirmish broke out in Abyan, where northern and southern troops, forces loyal to ‘Ali Nasir, and a small cell of Islamic Jihad zealots were all camped in close proximity. More skirmishes erupted wherever units of the two armies were positioned near one another, more than once ending with the retreat of southern soldiers into Bakil territory.

These low-intensity, low-casualty battles prompted a barrage of seminars, editorials and peace marches under the slogan “No to War, No to Separation, Yes to the Document.” Campus sit-ins in Sana‘a and Aden, a new round of mass regional and tribal conferences from Hudayda to the Hadramawt, and smaller demonstrations in dozens of locations made a powerful statement. Perhaps even more remarkably, they were covered positively by the entire media. Everybody tried to identify with what was clearly the mood of the street.

Still the two sides stalled. Each leadership group contained both compromisers who talked to the other side and military diehards who insisted that the other side fulfill its part of the bargain first. By March, Abu Shuwarib and Abu Luhum left the country in disgust after publicly condemning what they called “preparation for separation.”

Along with the remainder of the Dialogue Committee, foreign embassies and regional leaders tried to avert a war. US and French military attachés on the Military Committee went around helping to “put out fires” until artillery broke up their luncheon in ‘Amran on April 27. US Ambassador Arthur Hughes, like the Yemeni cabinet and the Dialogue Committee, shuttled between Sana‘a and Aden. Several Arab leaders met with or sent personal envoys to meet both sides. King Hussein had hosted the Document signing ceremony in Amman, physically pushing the two reluctant ‘Alis to embrace on television; at talks hosted by Sultan Qaboos in Oman in early April the cameras recorded a warmer hug. Egypt’s Mubarak had invited Salih and al-Bayd to Cairo the first week in May, and extended the invitation again and again during the fighting.

All to no avail. Public dissent, elite pressures and the other side’s taunts seemed to embolden elements in each camp favoring the bang of a military solution over the incessant din of debate. Would-be outside mediators came away appalled, especially by Sana‘a’s intransigence. As the wing of the YSP advocating secession over a merger of the armed forces prevailed within the Central Committee, Salih’s commanders showed him a battle plan “to preserve unity.” The president effectively declared war from Sana‘a’s Great Mosque on April 27. After skirmishes ignited into full-scale battle in early May, Salih dismissed the “separatists” from his government. The YSP and some smaller southern-based parties, including ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Jifri’s Sons of Yemen League, which had opposed the PDRY from Saudi Arabia throughout its entire history, declared a breakaway Democratic Republic of Yemen on May 21, 1994.

On a popular level, the Yemenis saw the “war between the two ’Alis” as recklessly squandering lives, resources, infrastructure and standards of living on crass and seemingly unwinnable power plays. Outsiders, too, saw both sides as taking unequivocal, rash positions. Both sides tried to marshal the widest possible government coalition, simultaneously silencing critics of their new policies. Salih imposed martial law, detained some critics and suspended all non-GPC newspapers, lest the northern peace forces undermine the drive to conquer the whole country. During the war, scores of rank-and-file socialists were detained in Sana‘a in each of three separate rounds of arrests. Aden, for its part, imprisoned hundreds of Islah members.

While the north quickly established military superiority and encircled Aden and Mukalla, the rump Democratic Republic showed that it had one key ally: the Saudis. While the Gulf monarchies had refused to meet Salih and only received his chief diplomat on the eve of full-scale war, King Fahd, a score of Saudi princes, and top-ranking Kuwaiti and Emirates officials granted audiences to al-Bayd and his colleagues during the immediate pre-war crisis. Once fighting began in earnest, the Saudi press reveled in the fulfillment of its predictions that democracy could only come to chaos. When the battle turned against the south, the Saudi ambassador to Washington, Prince Bandar, pressed the Security Council to call for a ceasefire, a halt to arms shipments and a UN negotiator. The Gulf Cooperation Council condemned the north’s aggression, claiming it was backed by Iraq.

Saudi support for those it had for decades called “godless communists,” after having backed al-Zindani and al-Ahmar’s northern opposition to unity a few years earlier, accentuates Riyadh’s abhorrence of unity—not to speak of democratization—and its readiness to support whomever might break it up. It also helped that the new southern government included a number of former sultans, sheikhs and other anti-communist dissidents with connections to the Gulf royal families.

While UN mediator Lakhdar Brahimi brokered a series of stillborn ceasefires, and the Military Committee reassembled, the independent half of the Dialogue Committee groped for a “national salvation” government, or at least a committee to sit down with the two sides again. But the northern command showed no readiness to compromise. After the “legitimate forces”—the northern army, ’Ali Nasir loyalists, and some irregular militias—entered Aden on July 7, virtually all government offices and public-sector enterprises were sacked and looted. The southern leadership, having fled Aden for Mukalla in advance of Salih’s army, abandoned the fight a week later to seek asylum in the Gulf countries.

On July 14, journalists and intellectuals held a well-publicized, well-attended seminar in Sana‘a, reminiscent of many similar sessions over the past couple of years, to discuss the country’s future. Three days later, at least a dozen participants were thrown into dungeons of the political security prison for two to six days.

One can already hear the apologists of authoritarian regimes in the Arab world crowing, along with the Saudi princes, that an unusual political opening has failed because even fundamental political liberties and civic participation are incompatible with Arab culture. But it is the regimes, not the cultures, that have proven to be incompatible with these goals, at great cost to society’s human, material and cultural foundations.