The Arabian Peninsula is known for an abundance of carbon resources, acute water shortages and a fluid labor force. The excerpts in this section highlight those features of the region’s political economy. In the first, Robert Vitalis analyzes the roles of American companies and workers inside Saudi Arabia. Following that piece are three entries abridged from an issue of Middle East Report entitled “Running Dry”: an opening vignette from the introductory essay by George R. Trumbull IV, Toby Jones’s explanation of the interplay of oil and water politics inside the Kingdom and Gerhard Lichtenthaeler’s account of Yemen’s water woes, particularly those in ‘Amran in the central plateau. The collection concludes with Enseng Ho’s humorous vignette about Yemenis colonizing Mars. In light of earlier and subsequent events, these essays shed light on the material underpinnings of political struggles.

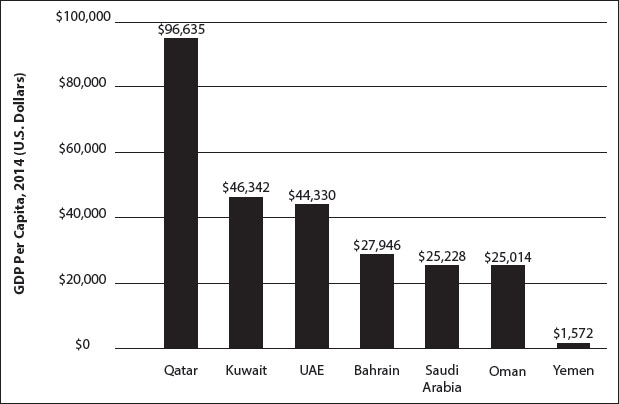

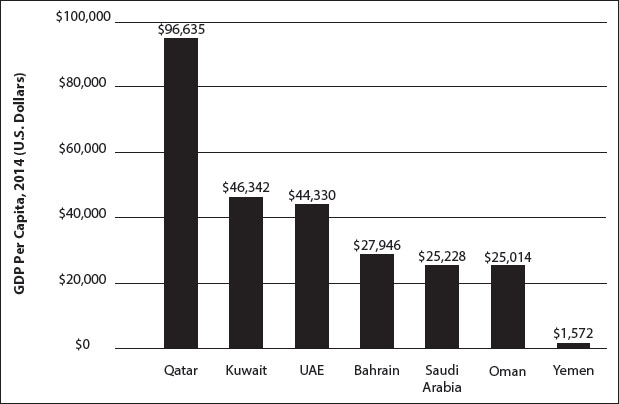

Table 1: Gross Domestic Product Per Capita of Arabian Peninsula Countries

Source: World Bank data

The Air Saudia flight approached Dhahran from the water, banking sharply above the causeway that links the Eastern Province to Bahrain. During the drive from the airport, I began to match the landscape before me to the one drawn from extant records of life and work on the early 1940s and 1950s oil frontier, which centered on the fenced-in Aramco company enclave then known as “American camp.” Recent retirees and the handful of third-generation Aramco-Americans (“Aramcons”) still working in the Eastern Province continue to refer to the sprawling expatriate housing complex and administrative offices of the state-owned oil enterprise, Saudi Aramco, as “camp.” Thus, unaware, they draw on a tradition going back more than a century to the mining communities founded on the trans-Colorado border lands, the original model for Dhahran.

It is in the world oil frontier of the Eastern Province where the American empire was made manifest. Oilmen and managers exported a system of race and caste segregation to its zone of operations in Dhahran and the satellite settlements and pipeline stations. These were institutions and norms of separate and unequal rights and privileges, of crude racism and progressive paternalism (“racial uplift”). In going to Dhahran I harbored the slim hope of adding to the archive I have been collecting of the migrant workers, Arab nationalists, communists and tribesmen who mounted the demonstrations and strikes that began the process of overturning Jim Crow in the Eastern Province.

The keepers of the official history of the Saudi-American partnership today appear zealous about preserving the myths of the oil frontier intact. The American embassy in Riyadh recently celebrated the golden anniversary of the special relationship, dating back to the 1945 meeting between ‘Abd al-‘Aziz and Franklin Roosevelt on a US destroyer in the middle of the Suez Canal. The Saudi embassy in Washington has mounted twin enlargements of the Life magazine photo of the meeting, lit from behind, on the wall of its in-house theater. Kneeling between the two frail but noble chiefs is Col. William Eddy, the Sidon-born and Princeton-bred missionaries’ son who translated for the king and FDR.

A dissident history, pieced together from other relics of the period, casts images of the old days in different light, beginning with Eddy, who is remembered as one of Saudi Arabia’s best friends in America, and the “only official who actually resigned” from the Truman administration in protest of its Palestine policy. The reality is that Eddy joined the CIA using the cover of Aramco “adviser” in Dhahran and Beirut in the 1940s and 1950s. More important, his own secret reporting to Washington on the famous Saudi workers’ strike of 1953 contrasted the “primitive land of low pay, slaves, eunuchs and harems to the comfortable conditions of US residents in Dhahran.”

Decades later, Saudi Aramco’s public relations staff continues to censor material that even hints at the racial discrimination and other forms of injustice that workers once faced in the Eastern Province. The reasons are clearly spelled out in the archives: The country’s own labor policies are vulnerable to similar criticisms. In private, officials with the firm recalled for me the period when they still had to drink from fountains in American camp, designated for Saudis only. Others complained that, given the way Americans once treated Saudis, the Kingdom’s labor policies receive far too much scrutiny.

The transformations in the oil market in the 1970s associated with OPEC are well known. Western multinationals gave up their control of the producing companies like Aramco, which is now owned by the Saudi state. They also were beset by the phenomenal oil rents produced by the price rises of past decades. These changes in tum altered many dimensions of the US-Saudi relationship if not the global position of the US “hegemon.” Even those dissenting theorists like Bromley, who caution against exaggerating the extent of decline of American power in the world economy, recognize these shifts. Firms lost the capacity to call out the gun-boats to protect themselves from expropriation, and geostrategists lost the means for direct control of the region’s resources. From Nixon on, US administrations have confronted the reality of sharply reduced leverage over Saudi rulers.

The story of the dismantling of the Jim Crow system in Dhahran is part of the same era of momentous change in the world economy, the equivalent of decolonization in the Saudi case, which was effectively completed with the “transfer of (Aramco’s) power” to the al-Saud and its agents. Nonetheless, the story has no place in the Kingdom’s public history today. The many Saudis and migrant laborers who built the oil industry and transformed the landscape are invisible to visitors of Dhahran’s new interactive “Saudi Aramco Exhibit.” There are no photos of the king’s visit to Aramco when he was besieged by protesting workers, or of the first Saudi oil minister, ‘Abdallah Tariki, Aramco’s greatest foe whose alliance with the Venezuelans paved the way for OPEC, or of the wild pro-Nasser demonstrations in Dammam, or of the posters of ‘Abd al-Karim Qasim that circulated throughout the Shi’a community on the heels of the 1958 Iraqi revolution.

[…]

In Riyadh, US representatives work in a fortress on the city’s outskirts, in a quarter reserved for embassies. The arms dealers, bankers, brokers and ex-CIA agents turned consultants who represent US investors in the Kingdom lease homes and live in compounds scattered across the sprawling metropolis. A handful have lived there long enough to be able to chart the capital’s remarkable expansion, decade by decade, shopping mall by shopping mall. For most Americans, however, a sense of history barely exists.

[…]

The Kingdom does subsidize jobs in the United States, through the $60 billion in US weapons and support services ordered by the house of Saud between 1990 and 1995. For the region known as the Gun Belt, the Persian Gulf represents a critical market at a time of crisis in the arms industry. These enormous orders mean more than just jobs and therefore votes for politicians or a way to cushion the pain while the Clinton administration oversees the consolidation of the new weapons and aerospace mega-firms such as Lockheed Martin and Boeing-McDonnell Douglas. Sales to Saudi Arabia and other foreign clients have kept whole production lines running—for example, the M-1 tank—which lowers the price of equipment the Pentagon needs for its worldwide forces.

American officials are candid about the weapons themselves being useless for the Kingdom’s defense. The expatriates who sell Saudis planes and tanks by the shipload say the same thing. “The Saudis can’t use and don’t need what they buy,” one executive in Riyadh said during dinner, delivering the punchline with pinpoint accuracy: “Ours are the exception, of course.” Defense industry people anchor the US business community in Riyadh today, flanked by the transnational banks and services and technology exporters such as AT&T, General Electric and Bechtel. Princes and other entrepreneurs benefit as middlemen and brokers in these deals. Meanwhile the opposition grumbles and opposition watchers in Washington wring their hands about the crisis looming on the horizon when the regime is forced to choose between guns and butter.

Led by Exxon and Chevron, the old owners of the Aramco oil concession remain fixtures of the Saudi oil and petrochemicals sectors, competing for licensing and management deals. It is a far cry, however, from the 1940s and 1950s when Aramco was in effect the Kingdom’s public works agency and oil ministry and America’s private diplomatic and intelligence operation rolled into one. An American ambassador once described the firm as “an octopus whose tentacles have extended into almost every domain and phase of the economic life of Saudi Arabia.” Back then, it was also relatively easy to see through the private interests behind the sudden discovery of a strategic interest in Middle East oil, an idea that some US officials apparently came to believe in as they managed the transfer of millions in rents to Aramco’s owners. Decades later, it is virtually impossible to find dissent from this commonsense view that US security and prosperity are inextricably bound up with access to the Gulf’s oil resources. The Pentagon for one is deeply invested in defense of this interpretation of the national interest as part of its own post–Cold War survival strategy. The proposition that markets can be relied on to supply the industrial sectors of the West with their energy needs at reasonable costs, without the need for troops, is a serious threat to their interests. US forces instead remain in place in the Gulf to wage the continuing war against Iraq, deter other hypothetical invaders looming over the horizon, and not least, secure the defense budget.

Life After People, the History Channel’s plangently alarmist imagined documentary series on the vestiges of civilization after an unspecified catastrophe, forecasts an end for Dubai’s infamous Burj Khalifa, the tallest building in the world at 2,625 feet. The desert location of Dubai, coupled with the persistent engineering challenges of building there, proves the undoing of Burj Khalifa in the History Channel’s scenario: Desiccation of cables, pulleys and other such quotidian technologies causes the failure of the tower’s automated window-washing equipment, which, in the imagination of cable television, swings free, damaging the building and plunging to the ground below.

The metaphor in the History Channel’s vision for Burj Khalifa, once a symbol of Gulf wealth and economic mastery, and now of overreach and architectural hubris, comes from the plunging to earth of Dubai World, the emirate’s sovereign wealth fund, amid the global recession beginning in late 2008. Dubai’s debt crisis was both of its own making and a result of general financial drought, the drying-up of wells of cash and income in a fundamentally altered world landscape. Nevertheless, the global financial media told their audiences that Dubai could tap another source of wealth, another well, through its connections to oil-rich Abu Dhabi, the federal seat of the UAE.

The History Channel series does not explicitly link the fanciful, imagined failure of Dubai to the financial, immediate one. But, back in the real world, the blithe reassurances of Dubai’s recovery reflected an assumed tie between oil and water: Oil wealth can compensate for the hubris of building a self-cleaning “superscraper” in one of the driest regions on earth. At a deeper level, water poverty and oil wealth are assumed to be divorced, incompatible, yet nevertheless locked in to a peculiar relationship in which abundance of one resource can make up for profligacy with the other. The assumption is ill founded. At some point, the oil or the water will run out.

The definition of entire states, and indeed entire regions, as “oil economies” implies that hydrocarbon exports alone keep the economies afloat. But the oil industry—its machinery, laborers and managers—relies as much upon the steady supply of water as global industry, commerce and consumers do upon oil.

The abundance of oil in Saudi Arabia is staggering. With more than 250 billion barrels, the kingdom possesses one-fifth of the world’s oil reserves, affording it considerable influence on the international stage. At home, oil has secured the fortunes and political primacy of the al-Saud, the country’s ruling family. And it has helped cement the nature of the country’s political system, fueling autocracy and ensuring that the kingdom’s citizens remain, in many ways, subjects. Their exclusion from the political arena has been justified as part of a bargain whereby oil wealth trickles down in exchange for quiescence; patronage has served as a substitute for political and civil rights. The bargain has basically worked, although even during the 1970s oil boom, the royal family faced trenchant criticism and, at times, violent opposition. For the most part, however, disenfranchised Saudi citizens have been content with oil-funded consumption and comfort, confident that they could forever expect their social and economic welfare to be cared for by the state. Oil’s power has often appeared boundless, an engine of such considerable riches that it was capable of anything, at least as long as the political bargain remained in place.

Nowhere has this power been more apparent than in Saudi Arabia’s pursuit of fresh water. Saudi Arabia has no natural lakes or rivers. Rainfall is rare, providing only meager succor in the arid environment. Ancient underground water reserves have been tapped and relied on heavily since the 1950s. Since at least the early 1970s, efforts to provide, manage and even create fresh water, and to do so cheaply, have been important elements of the Kingdom’s attempts to redistribute its vast oil wealth. Through massive engineering works and infrastructure development, including the design and construction of dams, irrigation and water management systems, oil wealth has been used to build a modern techno-state, one of the principal aims of which has been to provide water for household, agricultural and industrial use. In 1970 a subsidiary of the Coca-Cola Company completed the first massive desalination plant near Jidda on the Red Sea coast, a facility that turned seawater into fresh water. With plenty of oil to fuel the plant’s operation and with skyrocketing revenues from the sale of oil to subsidize the cost, Saudi Arabia has effectively been turning oil into water for the last four decades. Today more than 30 desalination plants are at work, each one costing tens of billions of dollars to build and operate.

In the last few years amid rising food costs and anxieties about depleted aquifers, Saudi Arabia began looking for secure sources of fertile land and water abroad. The government purchased sprawling tracts of farmland in far-flung corners of the developing world, including in places like Sudan, Pakistan, Egypt and Ethiopia. War-torn, impoverished or both, many of the countries that have emerged as objects of investment and development are hardly stable, calling into question just how much security they will be able to provide the Saudis.

The result appears to be the creation of a new kind of imperialism, in which wealthy oil producers are looking beyond their own shores to secure foreign natural resources, supporting and developing partnerships with sometimes murderous regimes, with the effect of disrupting local social and economic relations, all justified through the legal acquisition of property and through the mechanisms of the market. Just as resource scarcity served as a pretext for British imperial expansion in the Middle East in the early twentieth century and US dominance after World War II, water scarcity is being offered as justification for the projection of Saudi influence abroad. The charge of imperialism is tempting in part because of the rich irony of oil producers seeming to act the part of neo-imperialists. But it is more appropriate to see Saudi Arabia’s political and economic behavior as consistent with the rise of neoliberalism in the late twentieth century; rather than seizing and controlling territory directly, open markets and global institutions have been used to capture resources, shape political systems and establish dominance. Use of such mechanisms enables the Saudis to deny responsibility for the various material and political consequences that their adventures engender.

While the Kingdom’s quest for foreign resources seems to mark a new mode of behavior, water and agriculture have long been central to power and empire in Saudi Arabia. A look at Saudi Arabia’s past domestic agricultural and hydrological practices hints at what current ventures may have in store for those countries on the receiving end of Saudi agricultural investment.

In the early twentieth century, water and agriculture played critical roles in Saudi imperial expansion and the consolidation of the modern Saudi state.

The forces that drove the expansion of Saudi power from central Arabia in the early twentieth century were complex. Best known, and perhaps most overemphasized, was the role of religion and particularly Wahhabism, the interpretation of Islam that encouraged conquest, exhorted violence and came to serve as the official orthodoxy of the Saudi state. The clergy possessed considerable social and cultural power, helped police the public sphere and lent credibility to the ruling family’s claim to temporal political authority. But Saudi Arabia was not only an Islamic power. It was also an environmental power. Capturing natural resources and establishing centralized control over nature was a key political objective for the Saudis over the course of the twentieth century.

The connections between the environment and Saudi political power were established early on. In 1902 ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ibn Saud wrested control of Riyadh from a political rival and established the seat of what would become modern Saudi Arabia. Almost immediately Saudi leaders set to work expanding their political and territorial power. Arid and rugged, with only a few small oases, central Arabia was impoverished and isolated. There were, however, lush natural prizes on Arabia’s coasts, particularly in the east, which was home to the two large oases al-Hasa and Qatif. There, millions of date palm trees and sprawling verdant gardens were nourished by some of the largest water resources in the Peninsula. Covetous of both the water resources and the revenues generated by the date trade, the Saudis laid siege to the region in 1913, forcibly occupying it and incorporating it into their expanding political realm. Similar calculations went into Saudi conquests across Arabia, including along the Red Sea coast. The treasure was often the rich natural resources available in the targeted lands, keys to commerce and power.

The country’s imperial generation understood that their ability to recruit and maintain what turned out to be an imperial army depended in significant measure on their ability to master and manage Arabia’s scant water resources. Religious zeal went only so far in convincing those who joined the forces of the Ikhwan, the militia that laid siege to much of Arabia and helped forge the Saudi empire, to take up arms on behalf of the rulers in central Arabia. The Saudis enticed the Ikhwan with the promise of permanent and secure access to water, significant booty for the itinerant warriors. Access to water came at a cost as the Saudis dictated that the Ikhwan give up their nomadism and settle in agricultural communities called hujjar. The Ikhwan proved disinterested farmers and the hujjar ultimately failed to keep them in place. Nevertheless, the Saudis’ environmental impulse was already evident. Throughout the twentieth century, leaders in Riyadh would periodically attempt to settle other Bedouins, who through their movements sometimes troubled oil operations and even called into question the sovereignty of the state itself, by enticing them with secure water and subsidized agriculture.

Power over water and agriculture meant power over space and territory, as well as over human bodies, their labor and their movements. Although the country was arid and water-poor, the vast majority of Saudi Arabian citizens derived their livelihoods from some form of agriculture or herding into the late 1960s. Starting in the 1930s, oil merchants, geologists, mining engineers, social scientists and a network of experts arrived in the Kingdom, ostensibly charged with the responsibility of exploring, prospecting, extracting and marketing Saudi oil. They did that and much more. From the Arabian American Oil Company (Aramco) to individual experts to private consulting firms, American and European investors and experts were intimately engaged in not only the oil industry, but also in exploring for water and other natural resources, in the creation of knowledge about the natural environment, its place in local and regional economies, in the social lives of cultivators and in the creation of agricultural markets, and, most importantly, in the construction of the institutions that would be responsible for overseeing and managing all of them. Science, technology, social science, expertise and knowledge of the environment all became important instruments of power, symbols of authority and a means by which to enroll millions of subjects into the orbit of the centralized state.

[…]

Saudi Arabia’s long struggle to control and remake its environment has come at considerable expense. Politically, the Kingdom’s environmental imperative succeeded in helping shore up central authority. But it also produced an array of costly failures, often destroying or depleting the very resources that scientific and technical work was supposed to secure. The ill-fated al-Hasa Irrigation and Drainage Project was but one dramatic example. There were others. While food security, agricultural self-sufficiency and resource scarcity seemed to offer reasonable justifications for environmental interventions and massive engineering efforts, the reality was that concerns about scarcity and security served more to distract from the political calculations that also went into the planning, design and engineering work.

While the considerations driving Saudi Arabia’s turn to securing farmland and natural resources abroad are different from those that drove the early consolidation of empire and the processes of state building, there are important parallels. Overcoming scarcity and the pursuit of security continue to frame and justify Saudi Arabia’s domestic environmental imperative, even as it has been transformed into a global imperative in the early twenty-first century. Oil wealth continues to make possible the pursuit of and even the creation of other natural resources. It also makes possible a range of potentially devastating political and environmental costs in those places where the kingdom is doing business.

Saudi investment in militarized authoritarian regimes will strengthen them and help secure their own political pathologies. It also threatens to displace local cultivators or bind them to increasingly global networks of investment and expertise that could relegate their personal needs and interests to those of foreign powers, businesses and states. Seen this way, Saudi Arabia has arrived as a neoliberal power, willing and able to bend the policies of impoverished states and communities to its economic will. Perhaps most worrisome, as efforts to re-engineer the largest and most verdant oasis in the kingdom itself demonstrated, foreign farmland, foreign water and other natural resources, so vital and precious locally, will almost certainly be viewed as disposable assets. They have served and will serve as sites of investment, all justified in the name of the food security of foreigners, to be dispensed with when no longer profitable or desirable. Given the potential for considerable environmental damage like that which occurred in al-Hasa, it should be a source of concern that little will be left when the Saudis decide to leave.

Yemen is one of the oldest irrigation civilizations in the world. For millennia, farmers have practiced sustainable agriculture using available water and land. Through a myriad of mountain terraces, elaborate water-harvesting techniques and community-managed flood and spring irrigation systems, the country has been able to support a relatively large population. Until recently, that is. Yemen is now facing a water crisis unprecedented in its history.

The Middle East is an arid, water-stressed region, but Yemen stands out for the scale of its water problem. Yemen is one of the world’s ten most water-scarce countries. In many of its mountainous areas, the available drinking water, usually drawn from a spring or a cistern, is down to less than one quart per person per day. Its aquifers are being mined at such a rate that groundwater levels have been falling by 10 to 20 feet annually, threatening agriculture and leaving major cities without adequate safe drinking water. Sana‘a could be the first capital city in the world to run dry.

[…]

Agriculture takes the lion’s share of Yemen’s water resources, sucking up almost 90 percent. Until the early 1970s, traditional practices ensured a balance between supply and demand. Then the introduction of deep tube wells led to a drastic expansion of land under cultivation. In the period from 1970 to 2004, the irrigated area increased tenfold, from 37,000 to 407,000 hectares, 40 percent of which was supplied by deep groundwater aquifers. The thousands of Yemenis working abroad often invested their remittances in irrigation. Other incentives to expand farmland came in the form of agricultural and fuel subsidies. Farmers began growing less of the local, drought-resistant varieties of wheat and more water-intensive cash crops such as citrus and bananas.

The emerging cash economy also led to a dramatic increase in the cultivation of qat. It is estimated that qat production now accounts for 37 percent of all water used in irrigation. In the water-stressed highland basins of Sana‘a, Sa‘dah, ‘Amran and Dhammar, qat fields now occupy half of the total irrigated area. Groundwater levels in these highlands have fallen so precipitously that only the lucrative returns from qat justify the cost of operating and maintaining a well.

[…]

One-third of the 125 wells operated by the state-owned Sana‘a Local Corporation for Water Supply and Sanitation for supply of the capital have been drilled down to a depth of 2,600 to 3,900 feet. The combined output of all these wells barely meets 35 percent of the growing city’s need. The rest is supplied either by small, privately owned networks or by hundreds of mobile tankers. In recent years, as water quality has deteriorated, privately owned kiosks that use reverse osmosis—a water filtration method—to purify poor-quality groundwater supplies have mushroomed in Sana‘a and other towns.

Future supply options include pumping desalinated water from the Red Sea over a distance of 155 miles, over 9,000-foot mountains into the capital, itself located at an altitude of 7,226 feet. The enormous pumping cost would push the price of water up to $10 per cubic meter (roughly 35 cubic feet). Yemen may be willing to pay this price for household demand. For agricultural water, however, the elevated cost is out of the question since the quantity required per capita is at least one hundred times greater. Other options to supply Sana‘a from adjacent regions are fraught due to perceived water rights. Islam teaches that water is a gift from God and cannot be owned. Land, however, can. When a person digs or drills a well on his own land, he obtains the right to extract and use as much water as he can draw. The increasing awareness of the country’s water scarcity has resulted in a race to the bottom—every man for himself. Well owners are trying to capture what remains of this valuable resource before the neighbors do.

[…]

The ‘Amran basin is located 30 miles north of Sana‘a at an altitude of 6,560 feet. In 2008, the province established the ‘Amran Basin Committee, headed by the governor, to regulate water use. Other members include the directors of the districts that make up the basin, representatives of ministries and authorities concerned with water and agriculture, the local police chief and, importantly, farmers and local interest groups. Meetings are held every two months to discuss water-related issues and consider new applications for drilling wells.

Dwindling water resources are cause for alarm among both basin committee members and area farmers. Over 2,600 pumps now tap the catchment’s meager groundwater deposits. As a result, wells are being drilled to prohibitive depths, as low as 1,200 feet in places. Between 1991 and 2005, most wells had to be deepened by an average of 295 feet. At the same time, well yield—the quantity of water obtained per second—has plummeted. The period between 1991 and 2005 saw the number of wells increase by 120 percent, while the water supply rose by only 26 percent.

Villagers, increasingly aware of the need for collective action, are angered by the discovery that over 100 new wells were drilled in 2009, almost all of them without a permit. The arrival of a drilling rig sows tension between the farmer and the villagers, who raise their concerns with the basin committee. Bakr ‘Ali Bakr, the deputy governor and tribesman who handles the day-to-day operations of the committee, has been a key negotiator in defusing water crises in the ‘Amran basin.

Perched on the crest of an inactive volcanic cone is the village of Bani Maymoun. It belongs to the district of Iyal Surayh, home to the Bakil tribe and the watershed between the Sana‘a and ‘Amran water basins. The predominantly volcanic soil is ideal for growing high-value qat, cultivation of which has boomed. Bulldozers can often be seen leveling slopes for new fields, while truckload after truckload of additional soil is then hauled from afar to fill in the reclaimed terraces. With the unpredictable rainfall often not exceeding six inches per year, irrigation water has to be transported over rough tracks by Mercedes tankers. The result has been new water markets just for the cultivation of qat. Early in 2007, the price increase for irrigation water sparked a conflict that tested the community. Well owners from the village were starting to charge 5,000 riyals ($25) for a one-hour share of irrigation water. Up to that point, the commonly accepted rate paid by farmers with no well of their own had been just half that—2,500 riyals. The well owners, however, argued that new demand from water tankers queuing up at their wells justified the increase. They had become water traders adjusting to emerging markets.

The dispute soon reached the ears of Bakr ‘Ali Bakr. He called the tribal elders, who summoned the village men to reach a tribal consensus. It was agreed that well owners from the community were no longer allowed to fill up tankers for qat fields outside their immediate territory. Also, the price for a one-hour share was fixed at its previous level. “Such regulations reached by consensus are usually honored by all community members,” said Bakr. “Later, when one of the well owners tried to breach the decision, men from Bani Maymoun just aimed a couple of bullets at the tires of the water tanker. That put an end to the water business.”

Bani Maymoun is small and homogeneous, and in its case a verbal agreement on groundwater trade sufficed. In other conflicts over water resources, tribal communities increasingly resort to a written consensus-based form of regulation, known in Arabic as a marqoum. Hijrat al-Muntasir, a village located at an altitude of 9,842 feet at the western watershed of the ‘Amran basin, is one such place where drilling imperiled vital drinking water resources.

The drilling rig was blocking the narrow mountain track when I visited Hijrat al-Muntasir in 2007. Qat farmers had gathered around the heavy equipment as if to protect it. On the escarpment above, more than 50 tribesmen had positioned themselves, several with AK-47 machine guns. It appeared as if both groups had been awaiting our team’s arrival. The tension eased, and some of the tribesmen climbed down from the ridge to make their views heard. The qat farmers, desperate after yet another of their wells had run dry, were about to drill deep into the limestone. The villagers of Hijrat al-Muntasir feared that more groundwater extraction would wipe out their small spring, the sole drinking water source for the 700 inhabitants. They had mobilized their men to prevent the drilling. They accused the qat farmers and the rig owner of lacking a valid permit.

A short but bumpy drive took us to the village. Women and children with dozens of empty water containers lined the route to the nearby spring, displaying an impressive array of protest banners prepared by the school-children. “We hold you responsible for our future,” one of them read in Arabic.

A quick survey revealed the gravity of the situation. The water from the spring was carefully rationed. Salih al-Muntasiri, a village elder, brought out the document that listed the water allotments for each family—roughly ten quarts per person per day. Each quantity taken from the roofed cistern fed by trickle from the mountain spring was meticulously recorded and monitored by ‘Ali, the gatekeeper of the cistern.

Trouble for the qat irrigators had started when the people of al-Qarin, a village nearby, banned the sale and trade of groundwater from their local wells to outsiders. A marqoum, signed by the village elders, was written to regulate the details of this social contract. Groundwater levels around al-Qarin had fallen noticeably over the previous years, sparking fears about the future. At the same time, influential families from the village had been drilling new wells and were selling water to tanker owners who would then take it to new qat farms in other areas—including the fields near Hijrat al-Muntasir. As the ban came into effect, the qat farmers decided to give drilling one more try. On hearing the news, the men of Hijrat al-Muntasir sent a delegation to Bakr ‘Ali Bakr.

After several weeks of negotiations, both parties finally agreed to accept the outcome and recommendations of a government technical study. The various parties to the dispute met several times at the site of the drilling rig. Gradually, the focus of their discussions shifted from technicalities to sustainable management of the village’s water resources.

In the spring of 2009, I was invited back for the inauguration of a small village project. It was the first visit for the vice governor and other dignitaries. Hijrat al-Muntasir had slaughtered two oxen for the occasion. Banners leading up to the village welcomed the guests. There was good news—the drilling had been stopped. In addition, each household had built a cesspit to improve overall sanitary conditions. Community organizers working for the Social Fund for Development had paid the village a few visits, teaching the benefits of better hygiene.

But there was also bad news. As ‘Ali, the gatekeeper, unlocked the screechy iron access gate to the cistern, a number of village women came rushing down a steep path, each carrying a number of empty bright yellow containers. “No water today—go back home!” shouted ‘Ali. “Tomorrow morning, inshallah.” The daily flow of the spring had been reduced to a trickle—from ten to just five quarts per person per day. Whether the reduction was due to a temporary lack of rainfall or to permanent climate change, no one can say. “One thing is certain, however,” Salih al-Muntasiri told his German visitors. “Without your support in preventing the drilling two years ago, we would blame the slow drying-up of our spring on the qat farmers. There would be trouble and strife and God knows what.”

Communities such as Hijrat al-Muntasir are coping admirably with their diminishing spring. In social science terms, they retain a strong adaptive capacity, defined as the sum of social resources available to counter an increasing natural resource scarcity.

Social scientists now make a clear distinction between “first-order” scarcity of a natural resource and “second-order” scarcity of adaptive capacity. The latter, according to Tony Allan of the University of London, one of the world’s leading water experts, is much more determinant of outcomes. Developing coping mechanisms at the community level is a step in the right direction.

Coping mechanisms will not be enough to solve Yemen’s water crisis, however. The structural problems—among them, the draining of aquifers to irrigate fields of cash crops like qat—must be addressed. As has been stressed by Christopher Ward, a long-time analyst of water issues in Yemen, “a decentralization and the partnership approach can only be viewed as elements of a damage limitation exercise aimed at slowing down the rate of resource depletion, to allow Yemen time to develop patterns of economic activity less dependent on water mining.” In other words, Yemen needs to demonstrate adaptive capacity at the national level. A national debate on water is planned for late 2010, involving the president as well as other top opinion and decision-makers. This conference will be a crucial test of political will: The Yemeni political class will need to place a high priority on the development of viable alternatives to agriculture in order to prevent the country from slipping into Malthusian catastrophe.

When American social scientists began conducting research in the Yemen Arab Republic in the 1970s, there was a great sense of opening and adventure. This opening up (infitah) was also part of Yemen’s national mood, as a freshly minted republic emerging from a long civil war. A key engine of this opening and newness was the mass migration of Yemeni workers to Gulf oil-producing countries. The new republic’s new mood was encouraged by shiny new cars and shiny new goods packaged in plastic. A common phrase in the 1970s summed it up: Yemen had just been catapulted from the Middle to Modern Ages. In the 1980s, after president Salim Rubai ‘Ali’s Maoist peasant insurrections, or intifadas, of the 1970s had died down, and with improved relations with the Gulf oil-producing states under President ‘Ali Nasir, the socialist People’s Democratic Republic also experienced an infitah thanks to hard currency remittances from the Gulf. It seemed a truism to both Yemenis and Yemenists that Yemen could not turn the clock back.

With the hindsight of 20 years, it now appears that the 1970s was an exceptional rather than transitional period. The 1973 Arab-Israeli war, the power of OPEC, Sheikh Zaki Yamani, Americans shooting each other at gas stations—all these have been forgotten, as America’s streets now teem with monster minivans and a gallon of gas again costs less than a dollar. Now it is Yemenis who are shooting each other at gas stations. The initial building boom in the Gulf has ceased and Saudi Arabia faces budget deficits. The impact of these changes first registered in 1986, when oil fell from $30 per barrel to $10. But this was only temporary. Then the Gulf war erupted; but while oil prices went up, Yemenis in the Gulf went home. Again, this was supposed to be a temporary problem. If the working population of Yemen at that time was 4 million people, and a million workers came back from the oil countries, and assuming Yemen’s unemployment rate was a hypothetical zero, it immediately shot up 20 percent. The rate continues to rise. The temporary situation is now permanently temporary.

Everywhere in Yemen, one hears this joke: When the Americans landed on the moon, they found Yemeni Rada’is working there. Or Ibbis. Or Hadramis, depending on where one hears the joke. Recently, when the Pathfinder went to Mars, Reuters reported that a couple of Yemenis threatened to slap lawsuits on NASA, claiming they had inherited Mars from their ancestors. They were not joking. In villages throughout Yemen, where people have long been dependent on remittances from abroad, the mahjar, or diaspora, is practically considered a birthright. Some Yemeni families are virtual matriarchies. Sons do not know their fathers working abroad, and their sons do not see them when they in turn go abroad. Migrants might as well be on Mars. One begins to see why some people think Mars is a mahjar that they have inherited from their grandfathers.

There is a poignant side to the Yemeni lawsuit over Mars. On Earth itself, Yemenis have run out of mahjars. Although Yemenis have long experienced migration, its benefits have not been as durable as one might expect. Part of the problem is that successful émigrés generally do not return home, and after a few generations they are lost to Yemen. The high-profile Osama bin Laden and his family of construction magnates are a case in point. Part of the problem is that Yemenis have not made the most of their migrations. They have succeeded most dramatically in countries which were just opening up or booming, such as Egypt and Iraq during the Islamic conquests, Christian Ethiopia besieged by Ahmad Granye in the fifteenth century, India under the Mughals, Hyderabad under Muslim rule, Java and Singapore under colonial rule and, of course, the Gulf countries in the 1970s and 1980s. Under these conditions, Yemenis excelled and developed wealthy communities in the mahjar. However, once these places settled down to normal levels of growth and the émigré communities grew and assimilated, the Yemeni homeland would inevitably lose out. But there would always be new mahjars to explore.

At the close of the century and the millennium, it is unlikely that Yemeni migrants will find any more new countries about to be colonized or opened. They will have to make do with the mahjars they already have: America, Britain, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf, as well as lingering connections with East Africa and Southeast Asia.