The media offered conflicting narratives about the 2015 military intervention into Yemen’s civil war. Whereas the Anglophone press in Europe and North America and the Gulf media referred to the campaign of a “Saudi-led coalition,” some Yemenis, especially in the northern provinces, and some independent Arabic-language news outlets called it the “Saudi-American aggression.” Dispatches in this part of the book, predating the massive air campaign in Yemen, explain the deep American involvement in security arrangements in the Peninsula, especially for the protection of the Gulf monarchies. The opening vignette by Al Miskin (a pseudonym used by a few MERIP authors, roughly translating to “the jokester”) from 1996, mocks American indulgence of Saudi propaganda. More seriously, Charles Schmitz tracks US efforts to investigate the 2000 attack on the USS Cole in Aden harbor. Sean Yom describes American weapons sales to the GCC. Through blog posts, Toby Jones and I react to American policies toward Yemen and especially Saudi Arabia. Chris Toensing and Lisa Hajjar, respectively, criticize the Obama administration’s drone campaign in Yemen, including the assassination of US citizen Anwar al-Awlaqi and his teenage son. Given this background (and recalling Stork’s 1985 essay from Chapter One on the Carter Doctrine protecting Gulf monarchies) it is hardly surprising that the United States assisted the 2015 Saudi war effort with arms, surveillance and logistical support.

Boldly going where no one has gone before, the Clinton administration is busy renting out its broadcast studios to the Saudi king’s brother-in-law, whose new weekly call-in show, Dialogue with the West, airs inside the kingdom and in neighboring countries. The hour-long program is officially a joint venture of Voice of America (VOA), Worldnet and the London-based Middle East Broadcasting Corporation (MBC), owned by Walid al-Ibrahim, a relative of His Royal Highness, and part of the al-Saud’s increasingly visible media empire.

VOA, like other agencies of the Cold War national security state, is driven to innovate in order to protect its position in post– Cold War Washington. This has led new director Geoffrey Cowan to embrace the Saudi-controlled MBC. VOA supplies studio facilities and technical support in exchange for new non-shortwave outlets for its programming. In the case of the Dialogue program, a VOA personality fills one of the two co-anchor seats while its executives share “mutual editorial control” with their Saudi partners. This “sharing” has some VOA journalists worried that they are becoming mere propagandists for “foreign despots.” When Dialogue premiered on January 5, its opening news summary segment omitted any mention of the day’s undeniably important story, namely, the British government’s decision to deport the dissident Islamist Muhammad al-Masra’i.

Dissidents inside VOA began to circulate a petition around the office. Making good use of the State Department’s annual human rights report, the manifesto begins with a pithy account of Saudi ruling style (no political parties, torture, administrative detention and no human rights organizations) and warms that VOA’s integrity is threatened “when we partner with dictators who oppose every principle of freedom.” The crux of the matter is that VOA’s royal “affiliate” in this case is able to influence programming, ostensibly against official American journalism’s abiding respect for reporting news “without fear or favor.”

The investigation of the [October 2000] bombing of the USS Cole in Aden continues to irritate US-Yemeni relations. Last week, the agreement worked out between the Clinton White House and Yemeni authorities in November 2000, in which the FBI was allowed to submit questions to Yemeni investigators and observe interrogations, seemed to break down once again. Reports in American papers reiterated US accusations that Yemeni authorities were not cooperating with FBI investigators. “Senior bureau investigators say Yemen has denied them access to prominent Yemenis whom the Americans want to interview in their bid to link the attack to elements of [Osama] Bin Laden’s network in Yemen, which became a key base for him in the early 1990’s,” the New York Times stated. Yet this week, reports in the Washington Post and the English-language Yemen Times say that FBI agents have returned. Earlier reports, published at the beginning of August, of the FBI’s return have turned out to be false. Part of the US investigative team apparently arrived only to leave shortly thereafter. The current reports in the Post and the Yemen Times have not yet appeared in the Arabic-language press in Yemen.

Quick reversals and conflicting statements in the press are indicative of the considerable tension in current US-Yemeni relations. Hot on the trail of Osama bin Laden, its current archenemy, the FBI is treating the Cole investigation as an issue of US national security. US investigators remain convinced that the men awaiting trial in an Adeni prison were only part of a wider conspiracy that includes people in the Yemeni government. Last fall, a New York Times article on the case featured pictures of several prominent Yemeni officials and political leaders, suggesting that they had some role in the bombing or at least continuing links to Bin Laden. Yet no real evidence to support these charges has been presented. The only possible link to Bin Laden in the Cole case is a suspect now thought to be in Afghanistan. US investigators say he is the key to their claims. Yet US officials seem to believe that all political groups espousing Islamic rhetoric in Yemen are suspect, and subject to FBI interrogation. As in the Khobar Towers investigation concluded in June 2001, where US investigators insisted on keeping the case open in hopes of finding a smoking gun implicating Iran, in the Cole case the US foreign policy agenda takes precedence over the rule of law in a foreign country.

In Yemen, things are seen quite differently. The Yemeni government would like to try the suspects according to Yemeni law—which guarantees a speedy trial—and they resist giving US investigators access to high Yemeni officials based upon the FBI’s vague suspicions, or perhaps even prejudices. As Foreign Minister Abu Bakr al-Qurbi put it: “[J]ust because you have an Islamic connection does not mean that you have any relationship to the Cole bombing.” The Yemeni authorities are particularly anxious to avoid the appearance that they have surrendered national sovereignty to US investigators at a time when the confrontation in Palestine has turned public opinion sharply against US policy in the Middle East. Like the federal indictments in the Khobar Towers case, which alienated Saudi law enforcement officials, FBI actions have caused considerable resentment in Yemen.

Further complicating the issue are apparent tensions between US diplomats in Yemen and the FBI team and the repeated issuance of vague warnings about possible terrorist attacks against US interests in the Arabian Peninsula. In a series of bizarre incidents in June, following the Khobar indictments in Virginia, the FBI team in Yemen withdrew to an “unspecified” country, the consular service at the US Embassy in Yemen was closed, ships of the US Navy’s Fifth Fleet in Bahrain were sent out to sea and US Marines participating in maneuvers in Jordan were evacuated. In Yemen, American investigators announced that a group had been caught with plans to attack the US Embassy in Sana‘a and asked Yemeni authorities to round up the suspects. Yemeni authorities cooperated with American demands, but then reversed themselves when the Yemeni president said that the local religious group named by the Americans posed no security threat. US credibility was further strained at a meeting for members of the American expatriate community in Yemen where US officials could cite no new evidence of a security threat justifying the embassy closing. Officials merely listed various kidnapping incidents over the last ten years and the Cole bombing. Then reports surfaced that the FBI team in Yemen had withdrawn because of differences with the US ambassador, Barbara Bodine, over a request to carry heavier weapons. The head of the FBI team had asked for greater firepower fearing a looming attack. The ambassador refused the request, citing local sensitivities to heavily armed American investigators who were supposed to be mere “enhanced” observers, and the FBI unilaterally withdrew. Needless to say, the FBI team slated to return soon to Yemen has new personnel.

In Yemen, the constant issuance of security warnings is interpreted as political pressure on Yemeni authorities to allow US investigators free rein to pursue Yemeni officials with “links”—however tenuous—to Bin Laden. Yemeni authorities find this line of inquiry objectionable, since they share US interests in a stable security regime in the region. In recent years Yemen has normalized relations with all her neighbors, signing treaties to resolve border disputes and demarcate common borders and submitting to international arbitration to resolve a territorial dispute with Eritrea over the Hanish Islands in the Red Sea. Yemeni authorities have readily cooperated in building a military relationship with the United States. American soldiers led efforts to remove land mines after the civil war of 1994, US and Yemeni troops have conducted joint maneuvers, Yemeni personnel have received specialized training in the United States, Yemen purchased $5 million in arms from the United States and the commander of the Fifth Fleet recently traveled to Sana‘a. The US Navy chose Aden as a port of call for the Cole and other ships partly to boost the economy of the Port of Aden while further improving military relations with Yemen.

The Yemeni government also shares the particular US concerns about domestic political challenges from religiously inspired groups. After the two Yemens merged in 1990, many Yemenis who had fought—with US backing—against Soviet influence in Afghanistan returned to south Yemen to continue their cause against the godless communists in the former People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen. The trouble these “Afghani Arabs” caused for the Yemen Socialist Party (YSP) of the south was politically convenient for the leadership of the former Yemeni Arab Republic, for it both weakened the YSP and enabled the northern leadership to claim that it was the moderate center between leftist socialists and conservative Islamists. However, after the civil war of 1994 in which the YSP was defeated, the conservative groups became the sole political rival of the victorious northern Yemeni leadership.

Since the war the Yemeni leadership has moved decisively to weaken Islamist political groups and gain tighter military control over its territory. When Wahhabi groups attacked mosques and other Islamic religious sites in Aden that they considered “un-Islamic” shortly after the war, the government swiftly crushed them with a large military force. Again in late 1998, when militants kidnapped foreign tourists, the government responded with force of arms, killing four hostages in the rescue mission. The leader of the militant group, the Aden-Abyan Islamic Army, was executed after his trial. Yemeni authorities also expelled thousands of non-Yemeni residents suspected of belonging to “extremist” groups after the war. In the elections of 1997, 1999 and 2001, the ruling party presented itself as the moderate center representing tolerance and justice against their erstwhile allies in the Yemeni Reform Group, Islah, whom they now painted as “extremist.”

In pursuit of the Cole bombing perpetrators, the Yemeni authorities also took the liberty of rounding up whoever they suspect has ties to any group opposing the government. Clearly, the Yemeni government is interested in promoting an image of inclusive tolerance of the widely divergent political, regional and religious groups in Yemen while at the same time increasing domestic stability and security, on its own terms. It has no interest in cooperating with, or even harboring, groups that actually do work closely with Bin Laden. As was widely noted in Sana‘a, the Cole bombing was aimed at Sana‘a as much as it was at Washington. Why US investigators insist upon their right to interrogate the upper echelons of the Yemeni regime, when the Yemenis have been very compliant in their relations with the United States, is a mystery perhaps only the FBI could solve.

On January 14, 2008, the State Department officially notified Congress of its intent to sell 900 Joint Direct Attack Munitions kits (JDAMs) to Saudi Arabia. Though some in Congress balked at transferring such advanced military technology to a country still in a formal state of war with Israel, their protests soon faltered. The transaction is just the latest phase in the Bush administration’s plan to sell at least $20 billion of high-tech weaponry to Saudi Arabia and the five other Gulf Cooperation Council states—Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the UAE and Oman. These sales are part of a massive $63 billion package of arms transfers and military aid to Washington’s chief Middle Eastern allies first announced the preceding July. In addition to the GCC sales, over the next decade the US will provide $13 billion of arms grants to Egypt and $30 billion to Israel.

The Saudi weaponry sale was announced during President George W. Bush’s January tour of the Middle East, which featured successive stops in Israel, the West Bank, most of the GCC kingdoms and Egypt. The week-long mission reprised a rare joint visit to these states undertaken by Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Secretary of Defense Robert Gates in the summer of 2007, shortly after the original $63 billion announcement. In placing huge offers of arms and aid on the table, both trips aimed at strengthening decades-long strategic relationships with these key US allies—repeatedly labeled “forces of moderation” by Rice—in order to contain the threat of regional “extremism.” To use the Bush administration’s language, the transfer of American-made weaponry will “contribute to the foreign policy and national security of the United States” by helping countries that are “an important force for political stability and economic progress in the Middle East.” As Bush colorfully warned, peace and prosperity in the region are now under siege by “violent extremists who murder the innocent in pursuit of power.”

In actuality, the ostentatious aid and arms deals signify the latest shift in US Middle East grand strategy. Since 2004, the Bush administration has watched aghast as its stated ambition to plant thriving pro-Western democracies in the arid soil of the Arab world failed to take root. The culprit blamed by the White House and State Department is a legion of extremism whose members are anyone and everyone that has refused to play by Washington’s rules—Iran, Syria, Hizballah, Hamas, Iraqi militants and the ever present al-Qaeda. With its grandiose promises of “regional transformation” looking empty, the Bush administration will leave office by falling back on a tried-and-true tactic of hard realism: Shore up client regimes with enormous volumes of aid and arms, not only reminding the world of US military hegemony but also of the benefits of being one of Washington’s “moderate” friends, as opposed to its “extremist” enemies.

But the Manichean logic behind the fresh infusions of aid and weaponry cloaks a host of more complex political issues in the recipient states, from the resilience of authoritarianism in Egypt to the rearmament of Israel’s formidable war machine to the inflated tensions in the Persian Gulf between the GCC and Iran. Because these states are linchpins of US military strategy, the aid and arms sales are being substituted for critical reflection on these problems, not to speak of the diplomatic engagement that would be required to resolve them. As such, Washington’s new arms bazaar highlights the chronic inability of US decision-makers to escape from Cold War–style thinking in which the demands of geopolitical stability outweigh all other concerns.

[…]

Overshadowing both the Egyptian and Israeli aid agreements was the declaration of intent to sell at least $20 billion of arms to Saudi Arabia and the other GCC member states. Unlike Foreign Military Financing grant-based packages, the State and Defense Departments have long transferred advanced weaponry and defense equipment to the wealthy Gulf kingdoms through cash sales, each of which has to be approved by Congress. While Congress was not circumvented, the announcement essentially preempted lawmakers by publicly committing a large block of American military resources to the GCC. Further, the $20 billion figure is considered a “floor” rather than a “ceiling”; the ultimate value of the arms sales could be substantially greater. Nonetheless, at their Jidda press conference on August 1, both Rice and Gates defended the arms sales with their familiar refrain: “There is nothing new here.” And once again, they were technically correct.

Since the Iran-Iraq war, Washington’s mastery of the oil-rich Persian Gulf has required not only repositioning its air and naval forces around the GCC but also strengthening the military capabilities of local allied regimes through arms transfers. Several decades ago, oil wealth enabled Saudi Arabia and its smaller monarchical neighbors to rank among the highest per capita military spenders in the world. The severe fiscal crises of the 1980s failed to reverse this addiction. From the end of the Gulf war through the rest of the 1990s, Saudi Arabia allocated a rough average of 40 percent of central state expenditures to its defense sector; Oman and the Emirates, 40 to 45 percent; and Kuwait, Bahrain and Qatar, 20 to 25 percent. In historical terms, through 2005 Saudi Arabia purchased almost $62 billion in US armaments, Kuwait, nearly $7.8 billion; the Emirates, over $2 billion and Bahrain, over $1.8 billion, with the majority of these sales occurring after the 1990–91 Gulf war.

Western defense firms regard the Gulf kingdoms as an especially lucrative market today, given that record oil prices have them swimming in surplus revenue. The six GCC states spent $233 billion on arms imports from 2000 to 2005, accounting for 70 percent of total armament expenditures in the Arab world. But Washington also has a political reason to boost its Gulf arms sales relative to other major suppliers, such as Britain, France and Russia. Because they lack logistical know-how and technical sophistication, when the GCC militaries acquire frontline US weaponry—in the past, centerpiece items like F-16 Falcons, AH-64 Apache helicopters and M-1A2 Abrams tanks—they typically must also purchase secondary support agreements that allow American contractors to provide repair parts, personnel training, specialized data and other vital services. By deepening the dependence of GCC armed forces on its defense industry, the US also ensures greater compliance by these regimes with its geopolitical interests.

Since the $20 billion announcement, the US has wasted little time in expanding its GCC security commitments. From August 2007 through January 2008, the Bush administration notified Congress of 14 different GCC arms sales worth nearly $14 billion. Of these transactions, only the January proposal to sell the JDAMs to Saudi Arabia elicited fierce Congressional opposition; the kits transform “dumb” bombs carried by the Kingdom’s F-15 Strike Eagle jets, themselves purchased from the US in the late 1990s, into precise satellite-guided weapons, which some fear would pose a threat to Israel. Indeed, early talk of selling the JDAMs in 2006 so disquieted Israeli policymakers and pro-Israel lobbies that the State Department promised 10,000 more sophisticated versions of the weapon (along with 36,500 other assorted munitions and kits) to Israel, a sale formally announced in early August 2007.

Meanwhile, the other announced GCC arms deals have elicited little controversy. The most prominent are multi-billion-dollar sales of advanced Patriot PAC-3 defense systems to Kuwait and the UAE, which are designed to intercept tactical ballistic missiles and cruise missiles. Lesser transactions include sales of E-2 Airborne Early Warning Aircraft to the UAE, thousands of TOW [Tube-Launched, Optically Tracked, Wire-Guided] land missiles to Kuwait, and upgrades for Saudi Arabia’s E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System planes; among the many items under future consideration are the US Navy’s new Littoral Combat warships. Notably, such hardware will not transform the kingdoms into efficient fighting machines. The 1990–91 Gulf war revealed that GCC armed forces are technologically top-heavy and lack the numbers, training and doctrine to wage effective offensive campaigns. Similarly, the GCC’s near-defunct joint defense force, “Peninsula Shield,” has proven useless in regional crises since its formation in 1984. Rather, these items are intended to protect local airspaces and shorelines from foreign intrusion. “When the kingdom gets weapons,” Saudi foreign minister Saud al-Faisal chided one reporter at the Jidda press conference, “it gets them to defend itself.” In this case, Iran is the intruder in question.

Following the intensification of Iraq’s civil war, American hawks began to focus their wrath on Tehran and fanned similar sentiments inside the regimes of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the UAE and Oman. Fueled also by perennial suspicions of their Shi’i minorities, lingering animosity from previous territorial disputes and trepidation over the looming United States drawdown in Iraq, starting in 2006 Gulf monarchies fostered a climate of anti-Iranian alarmism unseen since the late 1980s. Mainstream voices warned of a radical Shi’i crescent stretching from Tehran to Beirut, an elaborate arc of instability masterminded by Iran’s firebrand president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and his coterie of mad mullahs. Meanwhile, the Bush administration, convinced that the Iranian regime was enriching uranium for use in nuclear weapons, framed the GCC, Egypt and Jordan as the Arab world’s moderate bulwarks against Iran and its forces of Shi’i extremism. Indeed, the first stop of the Rice and Gates Middle East tour was at Sharm el-Sheikh, where there were multilateral meetings of these eight allies, dubbed the “six plus two.” This was the fifth such US-sponsored gathering. Though the front’s official goals initially seemed drenched in honey—a stable and democratic Iraq, a unified and peaceful Lebanon, a state for the Palestinians—each successive conference made clear that the group was an entente against Iran, along with Hizballah, Hamas and Sadrist elements in Iraq, which were portrayed as Tehran’s subservient proxies. In addition, in May 2006 Washington enhanced its ties to the GCC by initiating the Gulf Security Dialogue, which brought together diplomatic, intelligence and military officials from both sides for coordinated meetings. It was through this forum that the United States first hinted at the GCC arms package in October 2006.

By the fall of 2007, the containment of Iran had become the predominant theme of US Middle East policy. As one Arab analyst noted, a new regional cold war had been invented, one in which a “Green Curtain” divided the United States and its “moderate” clients from the Iranian-led “extremist” camp. Vice President Dick Cheney decried Iran’s ambitions of “dominating this region,” while Bush cautioned that a “nuclear holocaust” would result if Iran continued its uranium enrichment program. Were the United States to commence hypothetical airstrikes against Iran’s nuclear facilities, furthermore, American strategists were convinced of Tehran’s capacity to launch catastrophic reprisals. In a typical war games scenario, the Iranian intelligence services would utilize their connections with Hamas in the Palestinian territories, Hizballah in Lebanon, Sadrist militants in Iraq and even Shi’i minorities in the GCC states to incite widespread violence and instability. Iranian naval forces would interdict oil shipping and US traffic in the Strait of Hormuz with mines and attack boats. Finally, Iran would lob nuclear-armed Shahab-3 ballistic missiles at US bases, oil installations and economic targets in the Gulf countries, and perhaps, in the most excessive scenario, at Israel as well. The result, as Bush warned in October, would be “World War III.”

[…]

All claims to the contrary, the Persian Gulf monarchies have been deeply affected by the Arab revolutionary ferment of 2011–12. Bahrain may be the only country to experience its own sustained upheaval, but the impact has also been felt elsewhere. Demands for a more participatory politics are on the rise, as are calls for the protection of rights and formations of various types of civic and political organization. Although these demands are not new, they are louder than before, including where the price of dissent is highest in Saudi Arabia, Oman and even the usually hushed UAE. The resilience of a broad range of activists in denouncing autocracy and discomfiting autocrats is inspirational. As yet, there are no cracks in the foundation of Gulf order, but the edifice no longer appears adamantine.

This state of affairs poses a historic challenge to the order’s number-one guarantor, the United States. The task is not, as some might think, to reconcile the Obama administration’s professed affinity for Arab democracy with the fact of its firm alliance with the states that the activists are working to open up. Rather, it is to aid those states in managing their domestic crisis so that the regional order can remain intact.

Gulf regimes have responded harshly to the fresh challenges from below, turning quickly from efforts at cooptation to coercion. At first, when revolts broke out in Tunisia and Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar and Kuwait hiked public-sector salaries, subsidies and other forms of patronage, literally trying to spend their way out of potential trouble. But there has been a surge in state violence as well, with thousands detained, disappeared and killed. Authorities in the Gulf are not known for their soft touch, but the present repression is both measurably greater and noticeably more out in the open. Typically concerned to hide unrest from view, out of fear of seeming weak or unpopular, the Gulf monarchies now seem disinterested in masking their violent response. In part, the states have lost control; activists can broadcast details of riot police assaults over social media. But the brutality on display is also intentional. The authorities wish to send the message that they can and will crush dissent with impunity.

The repressive turn is collective. Save in Bahrain, where Saudi Arabia and the UAE dispatched troops in March 2011, there has been no obvious collaboration between Gulf militaries. There is, however, a regional pattern. Oman has arrested hundreds and sentenced dozens to jail, including prominent human rights activists, for participating in protests. The UAE has arrested pro-reform demonstrators and stripped them of their citizenship. Saudi Arabia has arrested thousands and killed a significant number of Shi’i protesters in the Eastern Province. Kuwaiti authorities have deployed force against members of the opposition, as well as the bidun, native-born residents who do not enjoy the rights of citizenship. The Bahraini state has struck hardest of all, killing dozens, torturing hundreds and terrorizing the majority of the population with tear gas and birdshot. Major opposition and human rights figures, including ‘Abd al-Hadi al-Khawaja, Ibrahim Sharif and Nabeel Rajab, have been imprisoned.

It is not just the vigor of local and wider Arab protest movements that accounts for the alacrity of the Gulf regimes’ campaign of violence and oppression. The effort is partly driven as well by anxiety, mixed with a sense of opportunity, related to the balance of power with Iran.

Arab Gulf monarchs have summoned the specter of an Iranian threat ever since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Today, however, anti-Iranian hysteria is at an all-time high, whipped up by Iran’s perceived strategic benefit from the toppling of Saddam Hussein, the rise of Shi’i Islamist parties to power in post-Saddam Iraq, Iran’s posture of “resistance” during Israel’s wars on Lebanon and Gaza, and now the Arab revolts. Riyadh and Manama have been particularly provocative, deliberately poking their rival across the Gulf. Theirs is a conscious effort to discredit Shi’i empowerment—Bahrain’s population is majority-Shi’i and Saudi Arabia’s some 15 percent Shi’i—and to undermine popular support for domestic protest. For Saudi Arabia, in particular, stoking fear of Iran is one way to keep protests from spreading from the Eastern Province, where most of the Shi’a live, to the rest of the country. No doubt the Saudis, Bahrainis and others also believe that heightened tensions with Iran help to secure the backing of their benefactors, chiefly the United States.

Here, the Gulf regimes appear to have calculated correctly, for to date Washington has paid far more attention to Iranian maneuvering, real and imagined, than to the excessive force used to grind down pro-democracy and human rights activists on the Arab side of the Gulf. Gulf Arab rulers have turned what historically has been a source of US leverage—security guarantees and military might—to their own advantage. Indeed, because containment of Iran is a strategic priority for Washington, the US military has parlayed its withdrawal from Iraq into tighter bilateral relationships with the Arab monarchies to the south, stationing 15,000 troops in Kuwait and pushing for more naval and air patrols of the vital, oil-rich Gulf. Central Command’s chief of staff, Gen. Karl Horst, labels this shift “back to the future.” And, indeed, the Obama administration’s approach in the Gulf—that its Arab allies are strategic partners indispensable to regional commerce, the war on terror and containment of Iran—is consistent with 60 years of US policy. In this regard, the Arab uprisings have changed nothing.

Washington’s clear preference for the status quo in the Gulf has come at considerable cost to activists in the region. The United States has enabled the Gulf regimes to behave badly; the regimes, for their part, have exploited geopolitical rivalries to consolidate power at home.

There is a structural weakness in the US position, however, one that has become evident over time. The United States is tied to partners in the Gulf who are politically vulnerable, as clearly demonstrated by the protest of 2011–12 and the failure of the usual buyoffs and blandishments to restore quiet. Washington has long been committed to a set of security assurances that aim to maintain a regional system that is not sustainable on its own. The consequence is a paradox: The United States is by far the strongest power in the Gulf. Its Fifth Fleet, squadrons of warplanes and pre-positioned infantry and armor hold the region together. But its clout is also limited. Neither the White House nor the Pentagon is able to dictate political outcomes, not in Iraq, not in Iran and particularly not in the Arab Gulf states. The Gulf thus becomes no more stable as a result of the heavier and heavier US deployments, the increasingly more direct interventions, in the name of guaranteeing stability. Indeed, since the close of the twentieth century, US security commitments have contributed to the exact opposite trend. The United States has helped to destabilize a region it claims to protect.

Gulf security, notably the “energy security” supplied by the region’s oil and gas, is a perennial American obsession. In the early days after the discovery of oil, it was corporate profits that placed the Gulf at the center of US strategic thinking, but commercial and political concerns had converged by the middle of the twentieth century. The US military commitment to the regional order was stepped up in the 1970s, with the closure of British bases in Bahrain and elsewhere. For most of that decade, weary of projecting power directly, the United States attempted to arm surrogates—the “twin pillars” of Saudi Arabia and the Shah’s Iran—to do its bidding. That policy collapsed in 1979, with the revolution in Iran and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

From that point on, the United States would not outsource the protection of the oil patch. In his 1980 State of the Union address, President Jimmy Carter was forthright: “An attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.” Carter’s words were directed at the Soviets in Afghanistan, but his vision has guided US strategists long after the Soviet Union’s dissolution. It has been demonstrated by the repeated use of military force since the late 1980s, in what should be considered one long war in the Gulf.

Fretting about Gulf security is tied to considerations including terrorism and Israeli military superiority, Washington’s chosen method, along with bilateral treaties between Israel and frontline Arab states, for averting another major Arab-Israeli war. Most important, however, is energy. In particular, Gulf security is often framed by the argument that the outward flow of oil, critical to both the American and global economy, demands protection and that the best way to protect it is to underwrite the regional political status quo. When in late 2011 Iran threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz, thus blocking the main oil supply route, it was hardly surprising that the United States scrambled additional planes and ships to the Gulf. Such resolve is entirely complementary, of course, with the stated objectives of the Arab Gulf states, which also insist on the primacy of security. Over time, it has become axiomatic in political and diplomatic discourse, and even in scholarship, that Gulf states are engaged in a “ceaseless quest for security.” This phrase, indeed, served as the subtitle of a 1985 study of Saudi Arabia by Nadav Safran, a Harvard scholar who resigned from his administrative job at the university following the revelation that the CIA had funded his research.

Yet while US and Gulf monarchy interests have been served—oil has flowed, the revenues are high and Washington’s allies remain in place—it is a stretch to call the Gulf secure, let alone stable. The region has been wracked by war for more than three decades, with hundreds of thousands dead, much of the natural environment laid waste and every prospect of a repeat performance. The reality is that when US leaders iterate their commitment to security in the Gulf, what they mean is that they are committed to the survival of their allies and the political systems that dominate in the region. The result—Washington’s blind eye to the Gulf states’ repression—is often criticized as inaction.

But the opposite is true. In spite of considerable Congressional opposition, the Obama administration found a way to sell more weapons to Bahrain in 2012. It has also overseen significant sales to other regional allies, including almost $30 billion to Saudi Arabia, all based on the pretense that these states are instrumental in checking a troublesome Iran. The reality, however, is that none of the Arab states in the Gulf are capable of mounting their own defense. They are entirely dependent on the United States for their security. It is something US policymakers know well: Since the beginning of 2012 the US has positioned the USS Ponce, a large floating base, in the Gulf, moved a squadron of F-22 fighters to the UAE, doubled its minesweeping presence and deployed the Sea Fox undersea drone. All these moves amount not to inaction to help aspiring democrats, but to forceful and purposeful intervention on the side of some of the most authoritarian states on the planet.

The upsurge in oppression by Gulf states in 2011 reflected their shared deep disquiet about their own weakness: They have narrow social bases and historically have sought to manufacture loyalty to governments that are corrupt and self-serving. From Riyadh to Muscat, the Arab uprisings induced a sense of looming disaster, one perhaps unprecedented in intensity. It is clear, however, that the regimes believe they have arrived at a winning formula, turning crisis into opportunity. Paradoxically, therefore, the Gulf states have thrived off the very thing—political upheaval—that they have for so very long claimed to fear above all else.

In the mid-2000s, most of the Gulf kingdoms were keen to indulge the pretense of reform. They did more talking about reform than reforming—but even the talk is now passé. Back in vogue today are the police state and the counterrevolutionary tactics that prevailed in the 1970s. Indeed, the Arab uprisings and local unrest seem to have convinced rulers in the Gulf to offer less accommodation and wield more blunt force. It is arguable that, in the Gulf of the twenty-first century, crises are no longer undesirable, but rather have considerable political utility. In fact, given the arc of history—whereby the redistribution of oil wealth has failed to ensure regime stability or political quietism—the regional system may have arrived at a moment where political survival actually requires the manufacturing of permanent crisis at home and in the region.

To be sure, the uprising in Bahrain and protests elsewhere are potential sources of revolution, but the monarchies have been successful in recasting them as threats to the system (and domestic and regional security) rather than groundswells that reflect the interests of actual subjects. Rather than engage the ruled, the Gulf states feel increasingly compelled to characterize the terms of domestic politics, and especially opposition politics, as destabilizing, inimical to the (fictional) national interest and beholden to a conspiracy of outsiders.

It may be that the embrace of crisis, at least for short-term political gain, represents the latest stage of political development in the oil-rich states of the Gulf. With new grassroots political energy and emboldened demands for change, it is apparent that old patterns of political engagement such as handing out patronage are increasingly ineffective. While the redistribution of wealth has never satisfied everyone, even in times of plenty, levels of political engagement by ordinary Gulf Arabs seem greater than ever. What has not changed, however, is the reluctance of regional authorities to part with power. They remain steadfast in preserving an antiquated and rotten political order. These contradictory vectors, the growing expectation of participation versus intensifying efforts to maintain a closed system, help to explain the power of crisis in shaping regime behavior. To the extent that the United States endorses the status quo, it is complicit not only in the Gulf regimes’ efforts to quash citizen protest, but also in the redesign of Gulf security architecture by which crisis becomes the norm.

On September 12, amid popular demonstrations in Cairo and other Muslim cities and the death of an American ambassador in Benghazi, all said to be sparked by the Innocence of Muslims film trailer released by an Egyptian-American provocateur, a couple of hundred young men stormed the US Embassy in Sana‘a. They ripped the embassy’s sign from the outer wall, torched tires and a couple of vehicles, burned the American flag and breached the outer gates of the security entrance. Yemeni guards returned fire. This gathering was no impromptu assembly of populists: Sheraton Street, a divided highway with no sidewalks or bus stops but several military checkpoints, is far off the beaten track for pedestrians or people traveling by public transportation. While thousands of men and women massed downtown demanding a just resolution to the country’s long-standing political crisis, scores of armed militants purposely converged on the embassy in an SUV convoy. There was lots of speculation about who had sent them. Salafi extremists? Loyalists of the deposed president, ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih? Was it related to what had happened in Libya?

The threat level spiked at year’s end. In late December, the al-Malahim Foundation, publisher of a irregularly issued online magazine and advertised as al-Qaeda’s media arm in Yemen, announced bounties, payable through June 2013, of some $160,000 in gold for the killing of the American ambassador to Yemen and $23,000 for the deaths of American soldiers in Yemen, in order “to encourage and inspire jihad.”

Years earlier, in 2000, a second-rate but incongruously prescient feature film called Rules of Engagement, based on a story written by Sen. Jim Webb (D-VA), and starring Samuel L. Jackson and Tommy Lee Jones, depicted a mob rioting outside a poorly defended American mission in Sana‘a. The set designers, anachronistically enough, placed the quaint diplomatic compound in a popular neighborhood. Once upon a time, US envoys welcomed American citizens and Yemeni visa seekers at an architecturally distinguished stone-and-alabaster South Arabian mansion near the city center. It featured charming enclosed gardens of indigenous flora, and opened onto a cobblestone plaza, as in the movie. But after the 1982 explosions in Beirut killed emissaries and spies, a new state-of-the-art fortress was constructed on what had been terraced fields near the upscale Sheraton (then newly built) and a new gated community to house Yemeni military officers.

Gone were the days when Americans in Yemen could stroll over to the embassy and flash their passports or let drop a phrase of American vernacular to the guards in order to swim in the pool. Gone were the days when diplomats roamed the suq.

And yet Rules of Engagement depicted Yemenis (actually, the actors, costumes and venues seemed Moroccan), including women and children, mobbing a central destination where a hapless ambassador quivered under his desk until Marines staged a guns-blazing rescue. In the movie rendition, even a girl who appeared to be disabled pulled the trigger of an AK-47 (or Kalashnikov) semi-automatic rifle. There followed courts-martial for the Marines, who were accused of slaughtering civilians. The moral of Hollywood’s version of Webb’s story seemed to be that the tribunals were wrongheaded: All Yemenis could be crazed terrorists, and the rules meant to inhibit the Marines from gunning them down were foolhardy.

This fictional message has since been internalized as soldierly doctrine. There are few if any rules in Yemen, the theater of operations in the “war on terror.” The counter-terror campaign does not distinguish fighters from little girls or, especially, men of fighting age. On December 24, two US drone strikes killed five suspected militants in al-Bayda and Hadramawt provinces. These have been more salvos in an ongoing battle of scores of bombardments by drone or fixed-wing aircraft since 2002, most in the past few years. Several high-profile al-Qaeda operatives, some nameless armed men, and assorted family members and innocent civilians have been blown to smithereens by Hellfire missiles. In the last days of 2009 Obama authorized a strike that left at least 20 children and a dozen women dead in the southern town of al-Majala, along with one militant. Later the US-born Anwar Nasir al-Awlaqi, a preacher suspected of inspiring the perpetrator of the Fort Hood shootings and the failed “crotch bombing” aboard a Detroit-bound commercial airliner at Christmas 2009, was killed; weeks later, so was his teenage son. Even American citizens are not due trial before execution, evidently.

Most of the more than 50 recorded air attacks inside Yemen in 2012 are known or supposed to have been launched by Americans. Most dramatically, a September 2 airstrike near Rada’, a historically important but now godforsaken, flyblown town in al-Bayda province where al-Qaeda militants had encamped, exterminated three children and nine other civilians. Around Rada’ and many other towns, the maddening overhead buzz of drones is a persistent token of American surveillance. The Obama administration’s remote-controlled “signature strikes” directive posthumously deems any able-bodied men in the line of fire legitimate targets in the war on terror. This is the shoot-first-ask-questions-later opposite of the strategy depicted in Rules of Engagement.

Despite its intensifying involvement in Yemen, the United States has not formulated a Yemen policy or even a genuinely diplomatic mission there. Instead it has a policy of keeping the Saudi monarchy secure and happy—and a related counter-terrorism policy that is an extension of the post–September 11 “Af-Pak” strategy. Washington regards Yemen as a theater of counter-terrorism in Saudi Arabia’s backyard. It’s as if it isn’t a real place where real people demand decent governance or respect for human rights. The Obama administration has wasted scant breath supporting Yemen’s demonstrators for democracy and social justice. US ambassador Gerald Feierstein was tapped for his counter-terrorism credentials as well as his diplomatic experience. He works closely with intelligence and military officers. During the protracted negotiations under the Saudi-led initiative of the Gulf Cooperation Council to facilitate a transition from the rule of Salih to the presidency of his deputy ‘Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi, Washington’s envoy was a spy agency operative, John Brennan, not someone with a State Department pedigree or Hillary Clinton’s ear. The American reaction to Yemen’s prolonged pro-democracy uprising in 2011–12 was not to provide moral support to activists clamoring for social justice, much less to call for free elections or women’s rights. Rather, Obama, Clinton, Brennan and Feierstein sought to placate Riyadh by battling an enemy called AQAP.

Best known in the United States for a pathetic dildo bomb planted on a Yemeni-trained Nigerian bound by air for Detroit, AQAP is often said to constitute a grave threat to the American homeland. Local commanders and spokespersons reveled in the publicity, a boon for recruitment of jihadi wannabes from inside and outside Yemen, whose numbers swelled from a couple hundred to perhaps a couple thousand.

“AQAP” is an unconventionally bilingual neologism, neither English fish nor Arabic fowl. “AQ” stands for the Arabic-language al-Qaeda, giving extraordinary grammatical weight to the definite article “al-.” “AP” stands, in English, for the Arabian Peninsula. The Pentagon-speak acronym AQAP, adopted as if it were a proper noun by the US-based punditocracy and security wonks, evokes an image of formidable military prowess, perhaps rivaling the former USSR. The Anglophone term both does and does not convey the meaning in the Arabic phrase al-Qaeda fi al-Jazira al-’Arabiyya, which suggests a rebellion in the whole Peninsula, stretching beyond Yemen to Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf princedoms. Whereas the Arabic phrase signifies struggle against local despots, the English acronym is coded as a terrorist menace to the United States. As such, “targeted strikes” against “AQAP” suspects can be portrayed not as intervention but as self-defense—operations to preempt another September 11.

The United States is now fully yet incompletely engaged in South Arabia. In addition to surveillance and frequent bombardments, American measures to “stabilize” Yemen now include provision of light aircraft, armed vehicles, gadgetry and training; direct military cooperation with and command-and-control backing for Yemeni forces; cheerleading for Hadi’s restructuring of Yemen’s military command; some humanitarian assistance and token support for civil society initiatives; protection for the “Green Zone” comprised of the embassy and the Sheraton Hotel (fully rented for American military and civilian personnel); and extra coordination with Saudi security institutions to make sure that Yemen’s multiple conflicts do not spill across the border. Efforts to engage pro-democracy activists, Houthi rebels and/or Southern separatists are marginal compared to the escalating drone war.

Senate hearings to confirm John Brennan as the Obama administration’s appointment to be director of the CIA brought to light a heretofore clandestine American military facility in Saudi Arabia near the Kingdom’s border with Yemen. While journalistic and public attention rightly focused on extrajudicial executions of Yemenis and even American citizens, the new revelations suggest a larger covert Saudi-American war against Yemen. There’s almost certainly more to this story than what Saudi Arabia fails to confirm.

Information about the base was long withheld from the public by both the government and the media. NBC News, the New York Times and the Washington Post reported on February 5 and 6 that the United States built a secret airfield in Saudi Arabia over two years ago, primarily as a staging ground for strikes in Yemen. Both flagship newspapers acknowledged keeping this fact under wraps in deference to the Obama administration’s request for secrecy on national security grounds. Reportedly, the first operation conducted from the base was the one that killed the Yemeni-American preacher Anwar Nasir al-Awlaqi.

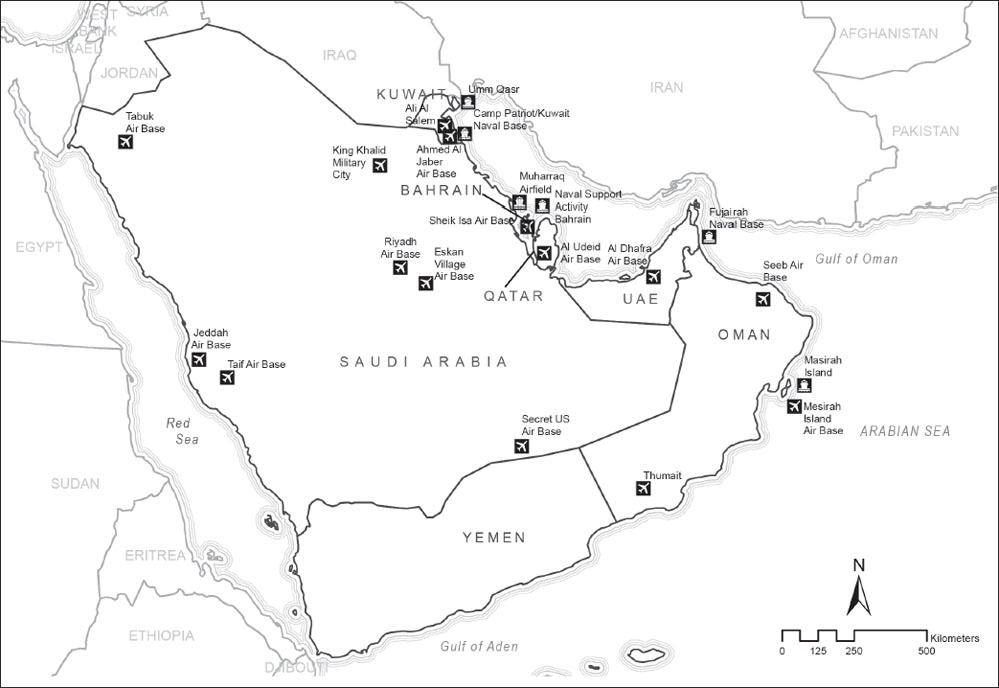

Map 4: US Military Installations and Shared Local Facilities in the Arabian Peninsula and Coastal Waters

Produced by the Spatial Analysis Lab, University of Richmond

Microsoft Bing aerial photographs from 2012 appear to show a facility in southeast Saudi Arabia, north of the Yemeni border and west of the Omani frontier, in the remote expanse of sand dunes called the Empty Quarter.

There also seem to be launching pads for unmanned Predator drones and/or Hellfire missiles at al-Anad Airbase near Aden. Al-Anad is an established installation on Yemen’s southern coast near the Bab al-Mandab, a crucial waterway connecting the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean. Now evidence has surfaced of yet another US base in the Hadramawt, in eastern Yemen, not far from the base in Saudi Arabia.

As more sleuths inspect more maps, we could learn of more military construction in the Peninsula, and of more Saudi engagement than has been acknowledged.

A reporter for the Guardian quoted journalism professor Jack Lule of Lehigh University, who called the media’s complicity in secrecy about the drone program “shameful.” Lule added, “I think the real reason was that the administration did not want to embarrass the Saudis—and for the US news media to be complicit in that is craven.”

Why would the Saudis be embarrassed? US-Saudi security cooperation has a history dating to the 1950s. Saudi Arabia offered facilities for the US-led Desert Storm campaign to restore Kuwaiti sovereignty after Saddam Hussein’s 1990 invasion. Yet the massive positioning of foreign forces in the land of the Islamic holy places, Mecca and Medina, later stirred controversy. When Osama bin Laden and his jihadi followers decried the presence of “infidel” armies on sacred territory, and used these boots on the ground as a pretext for the September 11 attacks on the United States, the Saudi defense minister ruled that bases inside the Kingdom could not be used for attacks on Afghanistan’s Taliban or other Muslim targets. Accordingly, American installations, including the King Sultan airbase in Khobar province, were relocated to other Gulf spots such as Qatar.

There’s more, perhaps lots more. There have been many targeted attacks purportedly conducted by the US military or the CIA against suspected militants in Yemen in the past two or three years. There have also been signature strikes. These are not aimed at persons who intelligence agencies have identified as enemies of the US. Instead, signature strikes are robotic attacks triggered by evidence of “suspicious activities” or “patterns of movement” observed, by drones, from the air, such as the loading of rifles onto pickup trucks. Although lethal targeted attacks, especially against al-Awlaqi, his teenage son, and at least two other American citizens have attracted the most attention of late, the signature attacks are even scarier. Yemenis are extraordinarily well armed, ranking alongside the US in number of firearms per capita. And gun-toting Yemenis almost certainly pack more firepower than their American counterparts: Markets in the northern part of the country sell bazookas and rocket-propelled grenade launchers. Further, Toyota pickups are ubiquitous in Yemen; four-wheel drive vehicles are a logical choice for navigating the country’s unpaved mountain roads. Grenade launchers in Yemen pose no credible threat to the American homeland. But they might, conceivably, be a menace to Saudi Arabia.

Exactly whose forces launched which attacks remains an unsolved mystery. Washington neglects to release accurate data on its forays into Yemen, while the Yemeni regime wishes to convey the impression of Sana‘a’s own prowess in counter-terror operations, and so keeps quiet about its foreign co-combatants.

There’s a third possibility. The Guardian recently suggested that some deadly bombings in Yemen were carried out not by American drones, or Yemeni counterparts, as often presumed, but rather “outsourced” to the Saudi air force. Saudi foreign minister Prince Saud al-Faisal flatly denied these reports. But there were other reports that the first US drone strike in Yemen in 2013 was assisted by Saudi fighter jets.

Saudi weapons purchases are the lifeblood of Western arms manufacturers. In 2010, the Pentagon notified Congress of $60 billion in arms sales to the Kingdom over the next five to ten years. If all goes well for the American weapons makers, this transfer will be the largest single package for any foreign country in US history. In the short term, however, according to the German magazine Der Spiegel, European nations are topping their Yankee competitors: France comes in first with 2.17 billion euros in sales, followed by Italy with 435.3 million euros and Great Britain with 328.8 million, contributing to total European sales of 3.3 billion euros or $4.4 billion. It makes sense that these armaments would be used, not merely stockpiled. True, documentation is thin. In 2010, Amnesty International said it was “extremely likely”—though difficult to verify—that Tornado fighter-bombers supplied by Britain to Saudi Arabia were used in indiscriminate attacks against Houthi rebels in northern Yemen that killed Yemeni civilians as well as militants.

The fact that America’s most prominent news organizations have not yet implicated Riyadh in the Obama administration’s war in Yemen is hardly evidence that Saudi interests and forces are not involved. The Times and the Post bury news of the Kingdom’s military affairs beneath titillating tales about women drivers, athletes and lingerie sales. Scoops about clandestine bases, collateral murder and counterrevolutionary meddling are left to intrepid investigators, bloggers and British reporters. If Saudis aren’t worried about the reports of secret bases, the story goes, then why should anyone else care?

Five corpses dangle from a bar slung between two construction cranes in Jizan in the southwest corner of the Kingdom near the Yemeni border. In several videos posted on YouTube in May 2013, the severed heads appear to be in plastic bags tied to the bodies. The sun is blazing. It looks like a busy intersection, with both vehicular and pedestrian traffic. Boys gather to gawk. Their elders either avert their eyes or snap their cell phone cameras to record the scene. According to Reuters, Al Jazeera, BBC and Amnesty International, the dead are five Yemeni gang members “beheaded by the sword” for killing a Saudi Arabian national and committing several robberies. The “crucifixion” (as it was called) was evidently imposed as additional punishment, post-execution and pre-burial.

Why did authorities arrange the macabre display? A court in Jizan must have deemed it shari’a-based justice. But maybe there was a purpose beyond giving these murdering thieves their proper deserts. Maybe stringing their bodies 25 feet off the ground was meant to send a message to others as well. Was it supposed to deter potential criminals who happened to be passing by? The Kingdom is in the process of expelling tens of thousands of Yemeni migrant workers—were authorities signaling to other Yemenis to go back south over the border where they belong?

Or—wait—are the intended audience the eyewitnesses visible in the surreptitious photographs? If so, what would be the message to apparently normal, law-abiding citizens crossing the street or driving down the road? What can they be thinking their government is telling them about the power of the state and the force of law?

What to make of the anxieties surfacing in the press in advance of President Barack Obama’s stopover in Saudi Arabia? Is the US-Saudi “special relationship” really in trouble?

Officials say no, of course. But beneath the surface, the relationship is indeed marked by uncertainty. The rulers in Riyadh have come to question Washington’s commitment to the Kingdom’s security, to Saudi primacy in the Gulf and to what has been one of the region’s most durable (and profitable) alliances.

Saudi trepidation is not entirely unfounded. Over the last three years, the two states have at least appeared to be at odds, with regard to the Arab uprisings and the resulting popular empowerment, intervention in Syria and the proper level of aggressiveness for cracking down on Islamists, especially the Society of Muslim Brothers. Given the Saudis’ thin base of support at home and their need to oppress their way to survival, it is hardly surprising that Riyadh that has led the counterrevolutionary charge in the Arab world since 2011.

Most importantly, the Saudis fear that the United States, in negotiating with Iran over the future of its nuclear research program, is cozying up to their most powerful regional rival. For years, Saudi Arabia has made Iran the target of the worst kind of sectarian opprobrium, treating the Islamic Republic as a bogeyman to be exploited in the interest of keeping American leaders sympathetic. It has not hurt the Saudi case that its most devoted supporters in the US are also closest to Israel, which shares a venomous view of Tehran. While it is unclear whether US-Iranian negotiations will yield anything meaningful, that the two are talking at all has shaken the Kingdom.

Quietly, US officials have begun to wonder about the same things. Is the US-Saudi relationship one that should remain unchanged? These Americans understand that the Saudis have set a dangerous regional course, one that has bought only temporary favor for a military regime in Cairo, won precarious “victories” in Bahrain and Yemen, and left a trail of human rights abuses and political malfeasance. There is a belief in Washington that Saudi Arabia remains at least somewhat cooperative in matters of counter-terrorism. But Saudi Arabia’s aggressive expansion of the politics of irhab, or terrorism, and its sudden acceleration of attacks on the Muslim Brothers is understood as double-edged—likely to deliver positive results in the short term but with catastrophic potential over time. After all, Saudi Arabia has been here before.

While American leaders ponder the reimagination of the “special relationship” in the distant future, the White House’s default position is to double down on the status quo, reassuring Riyadh that nothing has changed and supporting the regime by standard means—looking the other way while the regime terrorizes Saudi Arabian citizens, backs reactionary forces in Egypt and Bahrain, and abets violence in Syria. And, of course, avaricious arms merchants, with support from the Pentagon, continue to sell Riyadh billions of dollars in weapons.

Outside the circles of hawks and realists who are untroubled by Saudi Arabia’s bad behavior, more reasonable officials run up against a political inertia that claims the Kingdom is the least bad Gulf partner in challenging times, and that even while Iran sits at the negotiating table, the Islamic Republic is doing more harm than good.

Meanwhile, US and Saudi leaders have long shared antagonism toward, or at least skepticism about, the democratic potential of Saudi Arabia itself. James Schlesinger, a secretary of defense under Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford who passed away today, put it this way: “Do we seriously want to change the institutions of Saudi Arabia? The brief answer is no; over the years we have sought to preserve these institutions, sometimes in preference to more democratic forces coursing throughout the region. [The former] King Fahd [of Saudi Arabia] has stated quite unequivocally that democratic institutions are not appropriate for this society. What is interesting is that we do not seem to disagree.” While US officials are likely more open to the possibility today, there is so far little political will to encourage change in any meaningful way, and certainly not in public. The desire for autocratic stability in Arabia, embraced by old hands like Dennis Ross, has been replaced by the inertia mentioned above. Today, however, the stakes are higher, as a simultaneously emboldened and embattled Riyadh seeks to mold reactionary outcomes across the region, helping to push countries like Syria and Bahrain in terrible directions. While many observers would argue that supporting tyranny was never politically prudent for citizens in Arabia or for America, it is even more clearly the case today that the Saudis are the worst of the worst.

Among the cool heads in Washington, the prevailing view is that the United States is stuck, bound by President Obama’s minimalist approach to the region and the practical limits of American power. This is all true, of course. But these facts do not and should not mean that the United States has to remain dedicated to its historical alliance with Riyadh, particularly as the Saudis and their proxies continue to poison regional politics.

President Barack Obama plans an overnight stay in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia on March 28–29 for a rendezvous with King Abdallah. The enduring but always strange bedfellows have been quarreling of late over Saudi Arabia’s belligerent relations with neighbors Iran and Syria. Both sides hope during this visit to kiss and make up.

It’s a titillating occasion for the Saudi lobby, including the Saudi-US Information Service that churns out good news from the happy kingdom. The Service’s website filled a “special section” with feel-good links for the occasion. Johann Schmonsees, spokesman for the US Embassy in Riyadh, likewise trilled that the presidential visit “will be an opportunity to reinforce one of our closest relationships in the region and build on the strong US-Saudi military, security and economic ties that have been a hallmark of our bilateral relationship.” And erstwhile Israel-Palestine negotiator and diplomat extraordinaire Dennis Ross weighed in with an op-ed entitled “Soothing the Saudis,” advising the president to appreciate the fragile feelings and physical vulnerabilities of the royal family.

Following in the steps of predecessors from Franklin Delano Roosevelt to Jimmy Carter to George W. Bush, President Obama will ceremoniously re-consummate Uncle Sam’s semi-clandestine bilateral romance with one of the most intolerant, sadistic partners on the planet. As Anthony Cordesman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies recently observed in his essay “The Need for a New ‘Realism’ in the US-Saudi Alliance,” it is a liaison based on some common angst but few shared values. It’s an illicit affair conducted mostly behind closed doors.

As Schmonsees, Cordesman, Ross and others see it, American and Saudi concerns converge in worries about the terrorist threat to their conjoint military entanglements. The long backstory to this cooperation ranges from Saudi support for the anti-Soviet mujahidin in Afghanistan (Ronald Reagan’s “freedom fighters”) that spawned al-Qaeda to the prominent roles of Saudi Arabian citizens, including Osama bin Laden, in the September 11, 2001, attacks to ongoing real-time joint operations in Yemen.

Whether for internal political reasons or in anticipation of the Obama visit, in the past couple of months Saudi Arabia has expanded its definition of irhab beyond the post–September 11 hysteria in the American press encouraged by the Bush administration, beyond the Egyptian criminalization of the Society of Muslim Brothers under Nasser, Sadat, Mubarak and al-Sisi, and beyond even Riyadh’s own past crackdowns on dissident liberals and Islamists.

How has the Kingdom tightened the vise? Umm al-Qura, the official Saudi gazette, published a new Penal Law for Crimes of Terrorism and Its Financing on January 31, 2014, effective as of the following day. Irhab is now a sweeping term that covers not only violent attacks but also “any act” that would “insult” the reputation of the state, “harm public order,” espouse “atheism,” shake the “stability of society” or advocate any form of dissent, according to Human Rights Watch.

Going further, on March 7, the Interior Ministry issued a list of “terrorist organizations.” The criminalization of association with the Muslim Brothers rightly attracted the most attention because the Brothers are a legitimate (though illegal) political party in Egypt, and operate under other different names in other Arab countries, and because the Saudi ban on the Brothers features in the Kingdom’s spat with the spunky micro-petro-kingdom of Qatar and its media arm Al Jazeera, both accused of favoring the Egyptian branch of the Brothers.

But the Interior Ministry named not only the Society of Muslim Brothers, which is not as such an armed group, but also other guerrilla groups, some of them already on the US terrorist list, and two heretofore undesignated Yemeni entities. Several militant groups outlawed (in some cases not for the first time) were predictable enough, namely al-Qaeda and its eponymous offshoots in the Arabian Peninsula and Iraq. Two radical paramilitaries fighting in Syria, Da’ish (also known in English as the Islamic State of Iraq and Sham, or ISIS) and Jabhat al-Nusra, which not long ago looked like Saudi proxies, were also designated. All of these are Islamist militias of a Sunni salafi persuasion. Ideologically, they are distinguishable from the ruling Wahhabi doctrine in Saudi Arabia mainly by their opposition to dynastic rule. A little-known entity presumably named after the Lebanese Shi’i militia called Hizballah in the Hijaz was also declared to be a terrorist organization.

Finally, the new Saudi list named two Yemeni groups that have been engaged in mortal combat with one another for several years. Shabab almu’minin (Believing Youth) is a Zaydi Shi’i revivalist movement with a militant wing known as the Houthis who have held their own against Saudi forces, Wahhabi salafi evangelists and the Yemeni army along the Saudi-Yemeni frontier for the past decade. The Believing Youth’s nemesis, the Reform Congregation (known as Islah), is a right-wing political alliance of Sunni salafis, Muslim Brothers, tribal leaders (especially from the preeminent family of the Hashid confederation, Bayt al-Ahmar) and a segment of the Yemeni business community that for two decades received financial and moral support from Riyadh. Many Yemenis were surprised to see Islah, a legal political party represented in the Yemeni parliament, on the list. [Note: Islah was later dropped from the list.]

The broad set of criminalized activities under the Saudi Interior Ministry’s new rules include but are not limited to membership in, meetings or correspondence with, sympathy for, or the circulation of the slogans or symbols of any of these groups.

Obama’s conversations with King Abdallah and ruling family scions will not address human rights, women’s rights, democratization or social justice. The American embrace of Saudi Arabia is carnal and/or crassly materialist, not principled. Don’t expect a replay of Obama’s supposedly inspirational 2009 speech to Muslims and Arabs in Cairo, or an adversarial press conference. The White House would rather not draw attention to its dalliance with the misogynist Saudi gerontocracy. Press coverage of the visit is likely to be scant.

The two leaders are likely to discuss arms sales, the linchpin of the bilateral relationship. Ambassador-designate Joseph Westphal reiterated this realist perspective in his Senate hearing statement on March 24 about a mutually fulfilling relationship servicing both Saudi survival instincts and the American military-industrial complex. “We also have a critical security partnership,” he said. “Saudi Arabia is our largest Foreign Military Sales customer, with 338 active and open cases valued at $96.8 billion, all supporting American skilled manufacturing jobs, while increasing inter-operability between our forces for training and any potential operations.”

In addition, Obama and Abdallah will almost certainly affirm American and/or joint operations against al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, operations which continued in a series of deadly drone strikes against targets in Yemen in early March. The king may be upset that the United States has not taken military action in Syria or Iran, but he will almost certainly take comfort from American promises to defend the House of Saud against the most proximate threat to its security and well-being.

The US government wanted to kill Anwar al-Awlaqi long before a CIA-led drone strike actually succeeded in doing so on September 30, 2011. Before and after that deadly strike, al-Awlaqi’s kill-ability was and remains a bone of contention because he was a US citizen. The cleric, who had become radicalized as the “war on terror” wore on, moved to Yemen, his ancestral homeland, in late 2004. There, he became a prolific jihadi propagandist on the Internet.

On January 27, 2010, the Washington Post reported that he and at least two other citizens had been designated for extrajudicial execution. The listing of al-Awlaqi came on the heels of two incidents to which he was reportedly linked: the November 5, 2009, armed rampage by Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan at Fort Hood in Texas that killed 13 and wounded 29 people, and the December 25 attempt by a Nigerian, Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, to detonate a bomb hidden in his underwear on a transatlantic flight bound for Detroit. Al-Awlaqi’s alleged involvement in these crimes raises the question of why the government never indicted the cleric if it actually had information implicating him.

After the publication of the Post article reporting that al-Awlaqi had been put on the targeted killing list, the American Civil Liberties Union and the Center for Constitutional Rights filed a lawsuit in August 2010 on behalf of al-Awlaqi’s father, Nasir, to challenge executive authorization for extrajudicial execution of a citizen (Al-Aulaqi v. Obama). The case was dismissed that December when the court ruled that Nasir al-Awlaqi lacked standing, since the government had no intention of killing him, just his son.

Meanwhile, on July 16, 2010, the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC), which functions as the “government’s lawyer,” produced a memorandum laying out the legal rationales for the killing of al-Awlaqi. That memo remained a closely guarded secret until last week, when the government finally released it in heavily redacted form. Among the redacted portions is the first 11 pages laying out the factual basis for determining that al-Awlaqi had gone from inspirational to operational and become an “enemy combatant” and leader of AQAP, which is at war with the United States.

Leaving aside the quality of the OLC memo’s legal arguments, the underlying premise that killing al-Awlaqi in a military operation was a legal option depended on information provided by unnamed “high government officials” who “have concluded, on the basis of al-Aulaqi’s activities in Yemen, that al-Aulaqi is a leader of AQAP whose activities in Yemen pose a ‘continued and imminent threat’ of violence to United States persons and interests.”

The phrase “have concluded” sounds so authoritative. The secrecy that guards such intelligence makes its veracity literally unarguable. But what about the “intelligence” and the “legal logic” for the October 14, 2011, drone strike that killed al-Awlaqi’s 16-year-old son ‘Abd al-Rahman, as well as his 17-year-old cousin and five others while they were dining in an open-air restaurant? In the immediate aftermath of that attack, officials claimed that ‘Abd al-Rahman was a 21-year-old militant. After his grandfather produced the boy’s birth certificate proving the lie, the administration reverted to its default position of asserting that CIA operations are classified and cannot be commented upon. Indeed, the Obama administration has never produced an official justification or explanation about the killing of ‘Abd al-Rahman (who, by the way, was also a US citizen).

The OLC memo offers nothing in the way of understanding intelligence mistakes, which are numerous, as reflected in the large number of civilians who have been killed in drone strikes. ‘Abd al-Rahman’s killing is a particularly salient example of why it behooves us to be skeptical about the assurances of “high officials” who “have concluded” that death-causing intelligence is valid.

So far, federal courts are no help. On April 4 of this year, Nasir al-Awlaqi lost a second lawsuit, Al-Aulaqi v. Panetta, challenging the government’s constitutional right to kill US citizens without trial (and, in the case of his grandson, for no stated reason). As one of his lawyers, Maria LaHood, said after hearing of the judge’s dismissal of the case: “It seems there’s no remedy if the government intended to kill you, and no remedy if it didn’t.”

Midway through Barack Obama’s second term as president, there are two Establishment-approved metanarratives about his foreign policy. One, emanating mainly from the right, but resonating with several liberal internationalists, holds that Obama is unequal to the task of running an empire. The president, pundits repeat, is a “reluctant warrior” who declines to intervene abroad with the alacrity becoming his station. The other, quieter line of argument posits that Obama is the consummate realist, a man who avoids foreign entanglements unless or until they impinge directly upon vital US interests.

As usual, the mainstream assessments are more interesting for their unspoken assumptions than their truth value. In both takes, the president of the United States is appointed ipso facto as a world policeman whose job performance is rated almost solely on the basis of how often he orders the Pentagon into action. But the dominant evaluations of Obama are incorrect as well. And, at least in the Middle East, there is no better illustration than Yemen, the terribly impoverished and perennially misunderstood country in the southwestern corner of the Arabian Peninsula.

Has Obama hesitated to use force? Not if the explosions in Yemen are any indication.

Until the fall of 2014, Yemen was the primary Arab battleground of the Obama administration’s war on terror—but a firing range rather than a front. According to the London-based Bureau of Investigative Journalism, there have been no fewer than 71 US drone strikes in Yemen since 2002, with hundreds of fatalities, including a minimum of 64 civilians. The New America Foundation estimates that US drones and warships have fired 116 missiles at Yemeni territory in the same time period, killing no fewer than 811 people, at least 81 of them non-combatants.

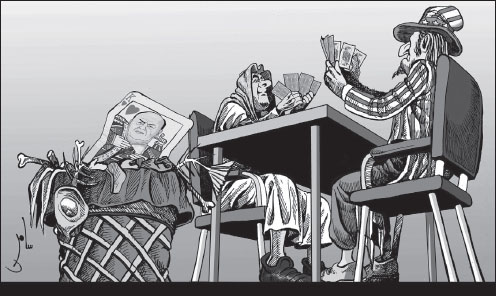

United States and Saudi Arabia at poker game seem to have discarded Hadi. (March 3, 2015)

By Samer Mohammed al-Shameeri

The actual numbers of attacks and casualties are almost certainly higher: Both of these studies rely on methodologies of cross-referencing press reports, and many of the drone strikes occur in remote locales where journalists are few and far between. And the start date of 2002 is misleading. Except for the assassination of alleged al-Qaeda figure Abu ‘Ali al-Harithi in December of that year, all of the strikes have been launched under President Obama.

The White House, indeed, views Yemen as a showcase of its approach toward al-Qaeda and sundry radical armed Islamist groups. “This strategy of taking out terrorists who threaten us, while supporting partners on the front lines, is one that we have successfully pursued in Yemen and Somalia for years,” Obama said in his September 10 speech extending the war on terror once more to Iraq and Syria. There were querulous rumbles on left and right at the notion that the statistics above constitute “success,” but from the Obama administration’s perspective, the claim is self-evident. The war in Afghanistan occasionally makes headlines, when American soldiers are killed or when the failure of US efforts to build a stable Afghan client state is further exposed. The war in Yemen is prosecuted entirely from the sky, with the odd, top-secret drop-in visit from Special Forces, so the dead bodies are all faceless and foreign and the story stays buried in the back pages.

Perception management aside, Obama’s boosters might argue that airstrikes on al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) are precisely the judicious, low-cost (to Americans) uses of force that a narrow interpretation of the national interest recommends. But this militia poses no serious danger to the continental United States. It has disavowed the so-called Islamic State, or Da’ish, that declared a caliphate in Iraq and Syria, and it has tenuous connections at best with al-Qaeda franchises elsewhere.

The immediate interest that is served with the Obama administration’s aerial campaign in Yemen is that of the “partners on the front lines,” the would-be central government in Sana‘a and its main regional sponsor, Saudi Arabia. These are the parties threatened by AQAP’s implied aspiration to ignite jihadi revolt “in the Arabian Peninsula.” In one sense, therefore, the war against AQAP is a local fight in global camouflage—like so much of the war on terror elsewhere. In a broader sense, however, the airstrikes are part and parcel of the same expansive construction of the national interest that has guided administrations of all ideological persuasions since the 1940s. The United States defers to the Saudi monarchy and its Yemeni allies in the name of “stability” in the landmass atop the world’s largest known reserves of oil and natural gas. In return, the United States gets a proving ground for its formidable firepower and an open-ended justification for its military hegemony in the Persian Gulf and beyond.