CHAPTER 1

SOUTHWEST TOWARD HOME

The boy wears a cowboy hat and boots, his jeans tucked in. He carries a gun, and a knife, and sometimes a sword. He can’t be older than five or six. He stalks small birds, rabbits, lizards, and longs for a snake to show itself. Feral house cats, some lacking tails and ears, maintain a wary distance. The boy played no part in that mutilation, but the cats avoid all human contact. He wanders in and among dusty pens, spying on enemies, then out into the mesquite and cedar brush, wary of Indians lurking on the hilltops above.

He carefully avoids the prickly pear, lechuguilla, and other spiny desert shrubs that grow all around him. Sotol and Spanish daggers and yucca entice him with their tall woody stalks. Always looking for better guns, knives, and swords, he tests each stick with earnest concentration. He searches among fragments of chert for arrowheads, knives, ax heads, overlooking the mortar holes that pock limestone outcroppings, the stone wickiup rings and trash middens, all of which bear witness to thousands of years of human struggle in an unforgiving desert landscape.

Heat drives him back into the shade of the barn. Generators rumble, turning the long driveshafts of the shearing rig. Dusty men speaking Spanish, caked with sweat and grime, wearing dungarees black with lanolin, bend over bleating ewes, rapidly running clippers through the oily wool, over the belly, and inside the legs. They tie legs together and clip the wool from backs, haunches, necks, heads. Too fast and bright red lines appear, then blood. A foreman steps over with a needle and thread and stitches the wound. Untied, a shorn ewe leaps twice and scrambles back to her sisters just off the shearing floor. The boy watches from the shadows, sees his father deep in conversation with another man who wears a broad straw hat. They speak of breeding, stud rams, market prices, the never-ending drought. The boy slinks farther back into the barn, the crepuscular gloom broken by slashes of light glinting through old boards, and climbs a haphazard mountain of burlap sacks stuffed with wool, at least five hundred pounds each, and disappears into his game.

One afternoon a few years later the boy and his brother prowl about with their pellet guns, looking for something to shoot. They discover dozens of small birds, some brightly colored and others dull and tan but all of them lively and chattering, captives of an old wire shed that might once have been a chicken coop. They kill every one of them. When the boys finish with their game, small carcasses litter the floor of the shed; others hang upside down by their feet from wires and perches. On this ranch and others like it the boys grow used to the sight of blood. Blood from the lambs whose ears they mark, whose severed tails shower them with gore. Kid goats must be marked and calves branded and castrated. A colt’s ears might be spared but not his testicles. Varmints they hunt down without mercy, for they compete for resources. The foxes and the coyotes and the bobcats and the mountain lions. The coons and the ringtails. Rabbits perish by the hundreds; they eat the grass, which is more precious than blood.

My childhood ended when I was twelve years old. Not so much because I began sampling my father’s liquor, but because that year I went to work, in the summer after seventh grade. Of course I had labored in one way or another for as long as I could remember, because my father believed a boy’s day should be filled with chores. We lived on a little piece of land just outside the Del Rio city limits, on ten acres among a patchwork of irrigated fields and homes, adjacent to a chicken farm, a trailer park, and a private rodeo ring where older kids practiced their calf roping. The old Border Patrol station for the agency’s Del Rio sector was one road over, and the international bridge across the Rio Grande was just a few miles away. On a clear day I could see the low hills of Ciudad Acuña through my bedroom window.

My childhood chores had been simple drudge work, and I hated them. I filled wheelbarrows with rocks from the fill dirt that had been spread around our house to make a proper lawn out of what was previously a field. I was lazy, and the job seemed endless. In my young eyes the yard was vast. After a pipe fence was built on the property, I had to prime and paint the fence with Rust-Oleum and collect the heavy leftover pipe segments that the welders had left lying everywhere. Somewhat more interesting was the care and feeding of the sheep, goats, horses, and the occasional calf that populated our pens out back, on the other side of an irrigation ditch. I would much rather have been splashing about in that ditch with my dogs, catching crawdads or snakes, and so I would somehow forget about my chores and lose myself in that tiny wilderness. Until I heard my father coming up the driveway, and then I’d make a desperate run for the wheelbarrow.

But in the summer of 1980, I began to work for hire, for a boss other than my father. I can’t recall how it was decided, though I do remember sitting in the office of the Southwest Livestock and Trucking Company, before the intimidating figure of Darrell Hargrove. Darrell agreed to take me on, working in his stock pens with a motley gang of other boys more or less my age. I would make $37.50 a week.

Such work was good training for country boys who had ambitions as ranch hands. In those days I always assumed that I was destined to be a rancher, that it was my duty to carry on the family business, so I was proud of my new job. Every morning we showed up at Hargrove’s pens on the north side of the Southern Pacific railroad tracks. All day we loaded and unloaded sheep, goats, and cattle from eighteen-wheeled tractor-trailer rigs and gooseneck trailers pulled by six-wheeled “dually” double-cabbed pickups and every other imaginable vehicle that could be kitted out to haul stock so that the animals could be counted, weighed, handled, assessed, fed, watered, then sold or traded and shipped on down the line.

Sometimes the livestock went right back on the truck, destined for a buyer in Mexico or some more distant market. Other times the animals were driven into pens where they awaited their indeterminate fate, milling about and bawling in their various brutish dialects. We put out alfalfa hay for feed and washed water troughs, threw rocks and knives at lizards, swatted flies and wasps and bumblebees, tortured crickets and grasshoppers, peed on ants, and sketched diagrams of naked women in the dust with sticks. We dipped Copenhagen snuff, strutting around the pens and feeling superior to the boys who spent their summer hanging out at the pool just up the road at the San Felipe Country Club.

I suppose I showed some promise as a hand, because after a few days of such work I was chosen to help with a special project. Hargrove had leased much of the Babb ranch in Terrell County and was grazing thousands of sheep in the rough canyon lands out there along the Rio Grande. The time had come for shearing, so he sent a team of cowboys out to do the gathering. The ranch was more than an hour west of Del Rio, so Darrell’s teenage son Frank would pick me up at home every morning at 3:30 for the long drive through the outer dark. Frank had longish blond hair that emerged from under a baseball cap and covered his ears, and a large beak-like nose. He was funny and bragged constantly about his exploits with girls. I did my best to stay awake with my wad of Copenhagen lodged against my gums, but the drive inevitably blurred into a half-waking nightmare of fanfaronade, loud music, and the aroma of rank tobacco spit in nasty makeshift spittoons.

At 4:30 or 5:00 a.m. we would pull up at the ranch in front of Smokey Babb’s trailer house. I remember sitting inside around a table, visiting. Smokey was skinny with wild black hair, and his wife, whose name I’ve forgotten, was quite fat. She wore a dirty terry-cloth housecoat. I have a strong memory of being given a rubbery piece of steak to eat that was cooked in a microwave.

Then we would saddle up and ride through the predawn darkness for what seemed like hours so that we’d be in the back of the pasture by daybreak. I was given a mule to ride, and on the first morning, like a fool, I immediately drifted to the head of the group, though I had no idea where we were going. Darrell’s son-in-law, a wise young cowboy named Carl, spoke quietly to me that first day. He advised me never to ride at the front of a party, but always to hang back, where I could watch the other men and perhaps learn something. Then we had arrived, and I was sent off, taking my portion of a pasture of several thousand acres, riven by canyons and choked with brush, with little real sense of what I was supposed to be doing.

I hooted and hollered in imitation of my elders, driving sheep out of draws and off the top of what seemed like mountains, pushing them in what I hoped was the desired direction, toward a fence where they’d bunch up and settle down for the long walk to the barn. My mule, with its choppy gait, was torture to ride, but at least it was sure-footed as we climbed up and down the slick limestone outcroppings and made our haphazard way through the day. At one point, when it seemed like hours since I had seen another cowboy, I began to wail and cry out for help. I was sure that I would be lost forever in that desert. No one heard me, or if they did, they were too embarrassed by my shameful behavior to even tease me about it. Perhaps my cries of distress were indistinguishable from those we directed at the sheep. Eventually, I saw another cowboy making his way along the caprock and realized I’d never been lost at all.

I remember sitting on my mule at the cusp of an impassable jumble of rock and brush dropping down toward the thin brown ribbon of the Rio Grande, slowly carving its way in broad meanders through the stone landscape. I remember thinking how easy it would be to cross.

The morning’s gathering ended with a huge flock of sheep clumped together, balking before a gate, hesitating until one or two leaders, pressed forward by the fearful mass of their ovine comrades, leaped through the gate, as if expecting a coyote to spring out from behind the cedar picket fence. After we ran the sheep from one pen to another, carefully counting two by two, the shearing commenced. The days were long and hot, with temperatures above one hundred degrees, and at noon all work stopped. Then the men told stories in Spanish and joked about subjects I pretended to understand. One day an older man, an Anglo cowboy who seemed to dislike me, took me aside and chewed me out for some imaginary offense. He told me he’d kick my ass if I ever did it again, and then he’d kick my daddy’s ass. I took the abuse in silence and walked away, mostly because I was fighting back the urge to bawl like a baby. Carl looked on from the shadows and nodded his head in approval of my silence.

After a few days of this routine I called in sick. I was tired of dragging myself out of bed at 3:30 a.m. and getting home at 9:00 p.m. I lost my place in the cowboy crew and went back to the dreary monotony of work in the stock pens, where at least I could get a decent night’s sleep. One of the chores we boys performed every morning in the stockyard involved hauling out the carcasses of animals that had died overnight, from being either crushed or otherwise injured in transit, or simply from the stress and terror of the experience. Typically, we’d find a handful of dead sheep or goats every morning. We collected them using a small tractor with a front-end loader. On what turned out to be my last day working for Darrell Hargrove, a boy named Mike and I went out to fetch some dead sheep. I remember standing in the front bucket of the tractor tugging on the carcass of a dead ewe when Mike started joking around, moving the bucket back and forth. I remember laughing, and then I lost my balance. My butt slipped between the tractor’s front end and the bucket of the loader, which closed on my body with crushing force. I heard a loud crack and tumbled to the ground. As I lay facedown in sheep dung, I heard Mike ask if I was all right.

I tried to tell him he’d broken my back. Mike must have run for help, for after some time I heard voices. Someone said to just get me up and walk me around, that I’d be okay. I’m not sure what happened next, but I remember screaming with pain.

Though my back wasn’t broken, that was the end of my first summer job. After two weeks in a hospital, my broken pelvis had healed enough that I was able to hobble about on crutches. A few weeks later I went to see Darrell Hargrove. He wrote me a check for seventy-five dollars.

Six months later I enrolled at Texas Military Institute in San Antonio. I had taken to running with an unruly crowd, drinking Coors around campfires in weedy overgrown lots or out at the cliffs of Amistad Reservoir, a huge lake formed by the dammed waters of the Rio Grande, the Pecos, and the Devils River. We wore cowboy boots and Wrangler jeans hitched around our skinny waists with braided belts and rodeo belt buckles and fought with other aspiring tough boys who called themselves cholos. One day in science class the girl sitting next to me flashed a lighter, so I stuffed my desk with paper and lit it just as the bell rang. I heard later that the fire was three feet high. When the vice-principal called me into his office that afternoon, I denied everything. Why would I start a fire in my own desk? I argued. He had no evidence against me, but the teacher wouldn’t let me back in the class. I went to see him after school and assured the man that I didn’t know who had started that fire but I’d be sure to find out and tell him.

No doubt I was getting a reputation around town as a hellion. My father grew alarmed and sent me off to school. At TMI, I learned to smoke pot and drop acid and drink ever greater quantities of alcohol. The music of Rush, Cheap Trick, AC/DC, and Black Sabbath provided the soundtrack to an education in delinquency. When my friends and I were spotted smoking pot behind the science building, the school’s prefects—seniors who maintained order in the dorm—took us down into a subbasement and gave us swats with a paddle until our bottoms were black with bruises. They weren’t opposed to drugs but had no tolerance for stupidity. We were more careful from then on.

When I came home for high school, I went back to work, this time for my father, spending summers at our family ranch in Juno, along the upper Devils River, about fifty-five miles northwest of Del Rio, and weekends working at the Sycamore Creek ranch just east of town. I bunked with the ranch manager at first, a fair-haired bachelor from East Texas named Pete. He had a degree from Texas A&M in agricultural economics.

I brought my new habits home with me from military school and introduced my friends to marijuana. My friend Scott liked it too much. His parents had died in a car accident, and eventually he came into some insurance money and bought a white Chevy Camaro. We all thought he was lucky until he crashed the Camaro and damaged his brain. I went to see him at the hospital in San Antonio. He looked so small in that bed—skinny, broken, with his jaw wired shut and a catheter on his penis. His eyes were open, though he was still in a coma, and he babbled incessantly. He was never quite the same.

All of us were lucky we didn’t end up like Scott. At Juno when I was fifteen, I rolled a ranch pickup. I was driving too fast on a stretch of highway along the banks of the Devils River. It was Sunday, and Pete was away, so I decided to drive up to a nearby country store to see a girl who was staying there for the summer. One of our heifers had gotten through the fence, and I took my eyes off the road, and then I was rolling and tumbling. I kicked my way out of the vehicle and caught a ride back to the house. Somehow I never crashed when I was drinking. Pete died on that road a few years later after flipping his pickup at a low-water crossing.

When I wasn’t out at the ranch, I went to Mexico every weekend, to bars with names like Boccaccio’s and Ma Crosby’s and Lando’s. We drank flaming tequila shots, bourbon and coke, and endless beers and fought with boys from other Texas towns who we thought were invading our territory. Sometimes I made the drive to Acuña from the ranch, along the old U.S. Cavalry route along the Devils River.

Cocaine started showing up among some of my friends in 1984. I ran into my neighborhood drug dealer one night in Acuña, and he suggested we go for a ride. He directed me to a quiet spot under some trees in the shadow of Acuña’s bullfighting ring, and we shared a couple of lines. Snorting coke in a car in Mexico was probably the single stupidest thing I’ve ever done. My dealer friend later sold me a baggy of what was probably baking soda for a hundred dollars, thus ending what might have been a dangerous infatuation.

The drug war was escalating all along the border at that time, but I didn’t really have the wit to notice it or to connect it to my cravings for stimulation and release. My father began to grow more agitated about our outings to Mexico. Rumors of kidnappings and killings on both sides of the river were circulating. Bodies and body parts began to turn up in border towns. Not all the killings were drug related.

On Friday, January 27, 1984, a customs inspector named Richard Latham was abducted from the international bridge at Del Rio. He was one of my father’s best friends, practically an uncle to me. I was at home alone the next day when I got a call that Richard was dead. A man collecting firewood along the highway near Eagle Pass found his body facedown in a ditch. He had been bound with his own handcuffs, shot twice in the back with his own gun.

Richard’s killers had robbed a jewelry store in Acuña. They crossed the river at around 4:00 p.m. in a gray 1978 Pontiac Grand Prix. In those days the port of entry at Del Rio was very low-tech and casual, with just a few inspection lanes and no video cameras. Agents entered license plate numbers by hand as cars approached. They used to just wave me through when I was headed home at 1:00 a.m. The agent on duty that day had some questions about the robbers’ papers, so he pulled them over for a secondary inspection, and Richard was working secondary. No one saw what happened. It was an hour before anyone noticed that Richard was missing.

The killers were soon caught, two of them within a day. At Eagle Pass they had crossed the river into Piedras Negras, where they sold the Pontiac. Rafael Calderon and Jesus Ramirez crossed back into Eagle Pass and hired a man to drive them to Presidio, a border town about 350 miles to the west. They were west of the Pecos River, between Langtry and Dryden, not far at all from our Cinco de Mayo ranch, when a state trooper pulled them over. During the stop, Ramirez shot himself dead, perhaps by accident. Richard’s gun and a bag of jewelry were found in the car. Calderon blamed Ramirez for killing Richard.

Ricardo Cortez was arrested a week later in El Paso. He and Samuel Olguin-Mato had separated from their compadres in Piedras Negras and caught a bus to Juárez. Cortez said that Calderon had pulled the trigger. Olguin-Mato later surrendered to police on the Santa Fe bridge between El Paso and Juárez. He also testified that Calderon was the killer. Cortez and Olguin-Mato were convicted of kidnapping and sentenced to twenty-three years in prison. Rafael Calderon was convicted of murder and received a life sentence.

Richard Latham was one of my favorite people. He was funny in a way that no one else was. He teased me without mercy, about the music I listened to, about girls, and about my longish hair, but he made me laugh when he was doing it. He had big ears and a big nose and ironic eyes. He snored like a chain saw. These fragmentary impressions and decaying memories are all that remain of him, for me, that and some newspaper clippings and an episode of The FBI Files.

My father told me that Richard had never wanted to take a job that would require him to carry a gun; he was afraid of developing a lawman’s swagger. But good jobs are hard to come by along the border, so he became a lawman in the end, though he never let the gun on his hip change him.

I can’t explain why, but I have dreamed about Richard’s death off and on for thirty years. I’ve tried to imagine what went through his mind during that last hour of his life as his kidnappers drove south toward Eagle Pass. I have sought to picture the killing itself, to feel what he felt as the life drained out of him into the dry rocky ground where he lay. I guess you could say his death scarred me, because all these years later I’m still haunted by it. If you talk to Border Patrol and customs people nowadays, everyone knows who Richard Latham was. His portrait hangs in the new state-of-the-art port of entry at Del Rio. Other agents who were on the bridge that day blamed themselves for his death. Some never got over it.

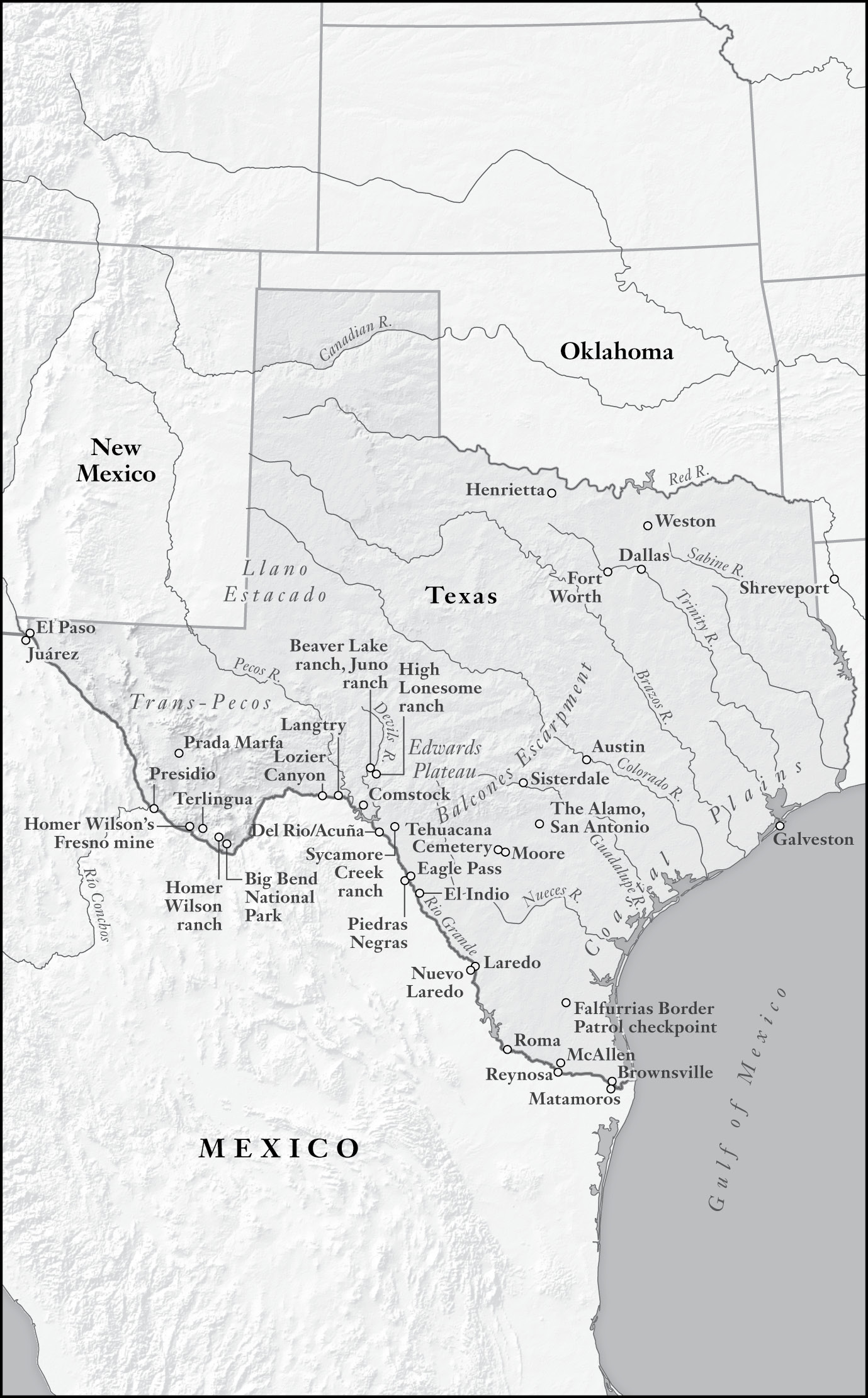

When I was eighteen years old, I packed up my car and left Texas forever. Maybe not forever, but I’m still gone. I spend as much time there as I can, and its landscapes inhabit my imagination, but since that bright sunny day in 1985 when I drove off to college in Tennessee, unconsciously reversing my family’s long-ago westward migration, I haven’t lived in my home state for more than a few months at a time. The Texas that I keep in mind is largely defined by the Rio Grande and from my hometown perspective stretches westward from Del Rio—which sits at a crossroads of Texas geography, on the northern shoulder of that intermittent stream that we insist on calling a big river, where the rolling grasslands of the Edwards Plateau give way to the great Chihuahuan Desert—through Comstock and beyond the Trans-Pecos creosote flats and the steep draws along the canyons of the Rio Grande and the wide volcanic vistas of the Big Bend to the barren sandy wastelands of El Paso. But also and especially it includes the rugged canyons of the western Hill Country that drain into the Devils River as it winds its way toward the Rio Grande. Beyond the immediate range of my boyhood domain, that long riverine landscape drops below the Balcones Escarpment to encompass the flat savannas and harsh Tamaulipan thorn brush of South Texas and the fertile lowland vegas of the lower Rio Grande valley. Beyond the Hill Country to our northwest, the Llano Estacado rises up and opens the infinite expanses of the high plains, whence the Comanches came down their raiding trails toward the rivers, where they preyed on their ancient enemies the Apaches as well as the precarious settlements and ranches of Texas and northern Mexico.

Above all, I think of Juno, now just a name on a map, a spot on a perilous winding road, no longer a town. The post office and the school, the hotels and the saloons and the old country store are all long vanished, the stones and the lovely old hardwood washed away by floods, carried off by interior decorators and “reclaimed,” or gone to dust.

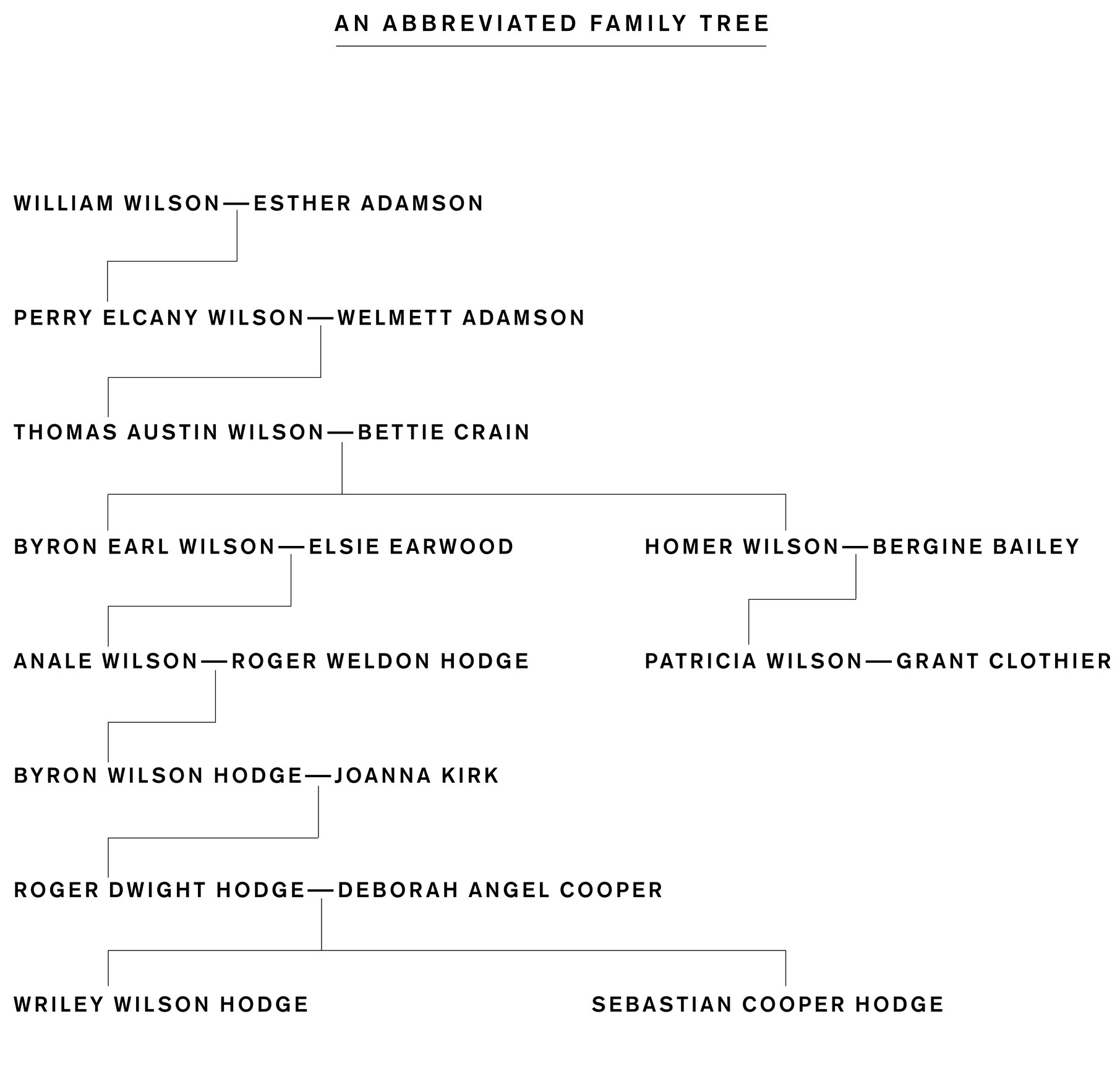

My great-grandfather B. E. Wilson, Byron Earl (called Dandy by his grandchildren), was just a young boy when his father, T.A. (for Thomas Austin), brought the family in a wagon to the Juno country. When I was a child, spending my summers working sheep and goats and cattle on my family’s ranch, the house Earl grew up in was still standing, miles from the highway, near a set of pens and a shearing barn called the Murrah Place. As I recall, it was in that barn that I sheared my first sheep, a difficult job that I did my best to avoid thereafter. Near that ruined house I shot my first deer and changed my first flat tire. I did my best to experience what it would have been like to live out there at the end of the nineteenth century, in that high lonesome country, traveling by horseback every morning to a remote schoolhouse where a teacher, in awesome solitude, taught the children of a handful of ranching families.

My ancestral home, as I’ve always thought of it, is that ranch in Juno, where an expanse of bone-white gravel marks the remnants of what we still call Beaver Lake, along a historic stretch of the Devils River. Ancient live oak trees shade the banks. Ponds covered in green scum, the remnants of flash floods that can fill the mile-wide valley, dot the old lake bed, and the gnawed leavings of a recently departed beaver colony lie scattered over the dried mud. I see it in my mind’s eye. Up the road a few miles, where the old Juno store used to be and not far from where my cousin lies buried, the beavers are still working, taking down cottonwood trees and stripping them of bark.

I never expected to be a professional Texan, one of those writers who wear the lone star like a brand, who play up the drawl and affect pointy boots or a cowboy hat with a tailored suit. Even as a child I never had much of an accent, and people still express surprise when I tell them where I’m from, for Texas to New Yorkers and other lifelong eastern city dwellers is a terrifying land of racism and violence and retrograde politics. Of course, eastern cities like Baltimore and New York and Boston can also be places of racism, violence, and retrograde politics. Yet something about Texas and the epic violence of its history continues to mystify, to attract and to repel the American imagination.

In 2006, when I came to occupy the editor’s chair of Harper’s Magazine, I was interviewed by a colorful New York Times media reporter who was dressed head to toe in black. When he learned I was from Texas, he immediately asked whether I owned a gun. I told him I did, whereupon he asked if I was a good shot. Once more I answered in the affirmative. And so was born the fleeting public image of a cowboy editor with a “gimlet eye.”

I was a little surprised by the discovery that I was a “Texan,” yet I had to accept the judgment. As it happened, I had just published an essay on Cormac McCarthy and the puzzling reception of No Country for Old Men, his great novel of the low-intensity warfare that has been consuming the borderlands for a generation. McCarthy’s fiction had long been the primary medium through which I indulged a stubborn nostalgia for my lost Texas landscape. No other writer has so perfectly captured the sublimity of that rough country, its subtle beauty and deceptive power. McCarthy’s prose comforted me in my spiritual exile and helped make bearable the collapsed horizons of life in a small New York apartment above a troll-like neighbor who regularly protested my toddler’s heavy footsteps with broomstick blows to her ceiling.

Then, several years ago, when I was suddenly free from both the troll and, for a time, the responsibilities of running a national magazine, my thoughts quickly turned to my lost Texas landscape. My young sons required instruction in handling a rifle, and it had been too long since my soul was refreshed by the sight of a limestone countryside dotted with mesquite and prickly pear. We met up with my family in Juno, where my father taught my boys to shoot and my grandmother told my children stories of the town’s heyday, of saloons and stagecoaches, Indians and outlaws. On the hill above the rock house my grandfather built from native stone, I showed my wife and sons ancient Indian metates, bedrock mortars ground in the limestone shelves overlooking the valley, where meal was made from mesquite pods and perhaps from the acorns of those gnarled oak trees along the riverbank, over the course of hundreds if not thousands of years. Right next to the metates was a mysterious concrete receptacle, about four feet high, clearly unused for decades. I’d been on horseback in that pasture so many times, but I’d never given it any thought; there were always so many inexplicable ruins, remnants of my grandfather’s adventures farming hay or onions or who knows what in the fertile bottomlands along the river. My father told me, as we watched my sons searching for arrowheads, that the tank had been used in the fight against screwworm flies in the 1930s. When I was growing up, Rambouillet sheep and Angora goats populated the pastures of that ranch, along with Brangus cattle. Today they are all gone, replaced by Spanish goats, which are exported to places like Detroit and Brooklyn, to be eaten.

Nowadays the neighboring ranches are mostly empty of livestock, predator populations are booming, and exotic creatures like aoudads and axis deer have invaded. They aren’t the only invaders. Now we have tobacco lawyers and oil tycoons buying up land, while drug mules paid by Mexican drug cartels play cat and mouse with various armed functionaries of the Department of Homeland Security. Beaver Lake, once a stop for stagecoaches and mail riders, a refuge to overland emigrants and ragged cavalrymen harried by hostile Indians on the southern road to California, is now merely a picturesque bend in the road. Like all American landscapes, that of West Texas is a palimpsest of lost and vanishing lifeways. Yet the aura of a potent mythology lies heavily upon the land and exerts a fascination that defies easy analysis; it draws new blood, new life, to refresh the thorny countryside.

Beaver Lake

As I stood there, surveying the vistas of my birthright, standing in a place where seven generations of my family have gazed over the same hills and valleys, I realized that my knowledge of the lives of my forebears and their contemporaries, their motivations and their passions, was pathetically thin. So much had happened in this place that I was ignorant of, but even more mysterious to me was the route that had brought my people here. I wasn’t even sure what year they had arrived in the border country, or even when they had come to Texas. It’s not that I never asked. I was vaguely aware that we had come from Tennessee, or maybe it was Virginia, like many of the early Texas settlers, but that was about all I could say for sure. I was always told we were Scots-Irish, but I’d read enough nonsense about that fabled tribe to be skeptical of what it meant. So much about the history of my family and my home remained hidden. How was it that my forebears had come to settle along the Rio Grande, just beyond the 100th meridian, engaged in one of America’s most iconic vocations?

Of course I knew the official version of the settlement of Texas. Like all Texas schoolkids, I had spent a year on my state’s glorious history in seventh grade, studying the deeds of Stephen F. Austin and Sam Houston, the treachery of the dictator Santa Anna, the great tragedy of the Alamo, and the eternal victory over Mexico at San Jacinto. In the years since I moved away, I had read a long bookshelf of the standard works, of which T. R. Fehrenbach’s Lone Star stands as the most magnificent and problematic example. But such epic histories sweep high above the hard ground of lived experience. Fehrenbach and others make their grandiose arguments and synthesize the material of human history into broad streams of migration and triumphant inevitabilities. The singularities of human striving and affection, which are far weirder than an epic “rise of a people,” tend to fall by the wayside. No historian could answer my questions.

The outsized Texas of popular lore is the “Lone Star State,” the cauldron of ugly politics that spawned George W. Bush, Rick Perry, and Ted Cruz. It’s the state you don’t mess with, the land that always remembers the Alamo but maybe not so much the slaughter of peaceful Cherokee and Mexican farmers. It’s the land of longhorn cattle, bull riders, calf ropers, Aggies, the oil patch and J. R. Ewing, and the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders; the land of the big river and an even bigger sky.

This Texas was settled by genteel southern planters, whose slaves cleared the eastern forests, and conquered by fierce Scots-Irish hill men, rough-and-tumble pope haters, borderlanders from the ancient war zone in the north of merry intolerant ole England, Scots Lowlanders, and Ulster brawlers, who in a great spontaneous migration swarmed out of the British Isles like termites into Appalachia. Yet the coves and sinkholes and eroded picturesque stubs of those ancient mountains could not contain them; the Scots-Irish longed for new borderlands, for the bleeding edge of civilization, for blood and soil and conquest. They needed more room, so they pushed westward, the most warlike of all warlike tribes. To Texas! Where the most vigorous and restless and violent specimens of the Scots-Irish were drawn southward as if by geographical and temperamental gravity, leaving behind their more sedentary brothers and cousins to raise a patch of beans or maybe some corn and a couple head of cattle. GTT! Gone to Texas! That was the sign they nailed on their empty cabins by way of explanation to their creditors and forsaken wives. They didn’t know it yet, but a cattle kingdom awaited. There was a whole new country to be liberated from the red savages and effeminate Spaniards in tight pantaloons. Coahuila y Tejas was a dark-eyed beauty longing for a real man to set her free. Texas would grow to become a rich man with murder in his eyes.

As I reread the conventional histories, I remained dissatisfied by their generalizations and hoary meditations on Texas “character.” Much of it struck me as self-congratulatory nationalistic rubbish. I read those fat tomes mostly for the footnotes, the infinite forking paths of primary sources and archives. The revisionist historians, the borderlands scholars, and the ethnohistorians were far more useful, but even so I was more drawn to the first-person accounts of exploration and contact and Indian captivity; the travel memoirs of fur traders and scalpers, soldiers and profiteers and pioneer wives; the apologetics of utopian visionaries and confidence men; the letters home of sheep farmers and cowboys, the travelogues of nineteenth-century journalists and architects. I immersed myself in the stories of the first Europeans who penetrated the wilderness of the border country, and that study led me to the Native peoples who were displaced by the arrival of the Spanish, then the Mexicans, the Tejanos, and the Anglo Texians.

The official story of Texas is not false, but there is another Texas, every bit as violent but perhaps more tragic and thus far more interesting. This Texas is a land of Apaches and Comanches and Kiowas, but also the Jumano, the Ervipiame, the Bobole, and the Gueiquesale. Explored by unlucky Spanish conquistadors like sad Coronado and misfortunate Cabeza de Vaca, who walked barefoot and naked from the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of California. This Texas, sparsely populated by missionaries and lonely ranchos, menaced by American filibusters, freebooters, and buccaneers and French pirates, was invaded by the Scots-Irish, yes, but also by Quakers and German liberals and utopian Frenchmen and Poles who sought to create a New Jerusalem but instead simply added to the entrepreneurial energies of Dallas.

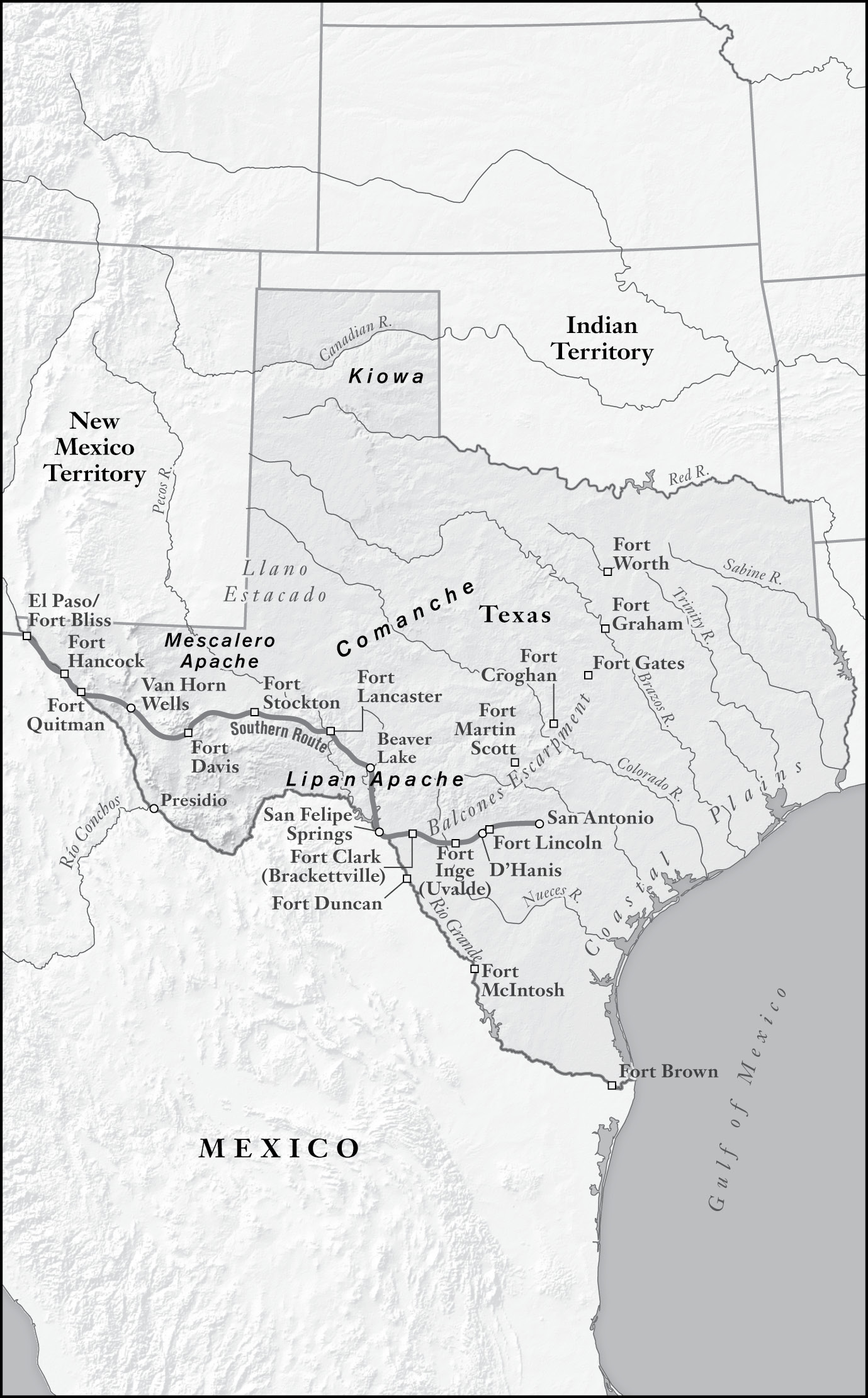

It should be obvious enough if you stare at the old maps, but it’s too often overlooked that the history of Anglo Texas up through the latter years of the nineteenth century is largely the story of East Texas, because during those early decades the Anglos were pinned down in precarious settlements along the lower reaches of Texas’s rivers in the gulf plains, with a few border settlements on the central plains and in the fringes of the Hill Country along the Balcones Escarpment. Austin was such a border town, as was San Antonio, exposed and vulnerable to the depredations of Texas’s great western neighbor, the Comanche empire. West Texas was unconquered, largely unsettled, until years after the Civil War, when the U.S. Army finally chased the last bands of Comanches off the caprock and into the dreary reservations of Oklahoma. Apaches were still raiding into the late 1880s. The military outposts farther west were mostly just primitive camps along the mail routes to El Paso and beyond.

My questions about the history of my family and how my ancestors had come to settle along the international boundary with Mexico soon broadened into an obsession with the character of the southwestern borderlands, the nature of the peculiar ranching society that had sprung up there in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and the whole history of human habitation in this hard country. But it wasn’t just the region’s past that came to preoccupy me. I felt that I was beginning to see, at least in outline, the whole arc of my particular American subculture’s life and death. There had always been something wild and dangerous about life along the border, but it seemed that a darker violence had overtaken us. Or perhaps an older darkness had returned.

THE MAIL ROUTE FROM SAN ANTONIO TO EL PASO, 1850S

I remember hearing talk in Del Rio about the bloody head that was found in a dumpster one day, and other body parts were rumored to have shown up across town. A drug-smuggling cult in Matamoros had carried out human sacrifices and made jewelry from its victims’ bones. Rising violence in Mexico, fueled by the perverse cycles of drug prohibition and insatiable market demand, had destroyed the local economies on both sides of the river. Piles of bodies, usually mutilated, often with messages carved in them, were routinely dumped in Mexican border towns. Hundreds of women had been murdered in Juárez, across from El Paso, where my mother lived for decades after she left my father. On the American side, an enormous law-enforcement presence had descended upon the region. All outbound traffic from Del Rio on Highway 90, heading both east and west, was stopped at Border Patrol inspection stations. People were routinely questioned about their destinations and private business. Helicopters and drones buzzed overhead. Sinister sedans with darkened windows raced along the highways. The border country was being transformed into an armed camp, and this militarization and the anxieties it heralded seemed to echo and recapitulate the history of the region in curious and unexpected ways. Down on the border, we were playing cowboys and Indians, cavalry and Comanches all over again.

Borderland narratives, like the water that falls so infrequently in the great Chihuahuan Desert or the mine tailings that leach into the local groundwater, all eventually flow toward the Rio Grande. That drift can lull the observer into an easy complacency, metaphorical or not. I’ve done my best to resist those complacencies, to think through the seeming inevitabilities of technological and economic determinism. Hundreds of years passed before the border solidified along the meandering and shifting course of the Rio Grande; for generations the borderlands began a few miles southwest of Independence, Missouri. Migrants, traders, mountain men, outlaws, scalpers, buffalo hunters, speculators, and prairie tourists quickly entered the Indian territories and made their overland crossings at the sufferance of the Osage, Pawnee, Kiowa, Apache, and Comanche nations.

The Spanish discovered the Rio Grande again and again, eventually finding that the Río de Nuestra Señora and the Guadalquivir and the Río Turbio and the Río del Norte and the Río Bravo were all one great river that flowed southward from the mountains of Tiguex and through the deserts and wastelands of the north to the lush valley and into the sea at Boca Chica with its palms and savage river people. Three Englishmen who came upon the river in 1568 called it the River of May and, once they had walked all the way to New Brunswick, reported the wonders they had witnessed in that land of “Furicanos” and “Turnados” and “great windes in the maner of Whirlewindes.”

Likewise, I have sought to rediscover the border and its rivers of water, people, data, and capital from different thematic and geophysical angles, sometimes journeying upriver, like the Spanish castaway and explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, and sometimes downriver, but always moving aslant, both physically and metaphorically, cutting against the currents of institutional, governmental, and industrial momentum with side trips and excursions, historical and literary and personal interludes, as well as digressions and dalliances with a broad cast of characters. Their interpretation will serve to place our contemporary strivings in a broader context of history, landscape, and memory. I can offer no definitive answers to the most existential of my questions, but my hope is that a significant pattern will rise to the surface as I sift the remnants of the vanished world that nurtured my family from the time my great-great-great-grandfather led his family into the canyon lands north of the Rio Grande.

What was it that brought my people to this particular place? Why would anyone attempt to settle in this unforgiving landscape? What were they searching for that was found here, in the devil’s own country, alongside his namesake river? My attempt to resolve these questions has resulted in many long journeys, in thousands of miles of travel all across my home state and beyond, and in untold hours of research, in archives both dusty and digital. I have followed the trails of my ancestors through six different states and at least fifteen Texas counties, tracing their habitations and professions and places of final rest. In tracking and describing my family’s migrations and peregrinations along the constantly shifting western borders of settlement in the Southwest, I have tried to create a portrait of the borderlands. Along the way I have marshaled the eloquence and insight of fellow travelers, those who followed similar paths and byways, as witnesses to my family’s passage. I have sought out the testimony of contemporary border dwellers, hoping to understand what has become of my native landscape under the watchful and unblinking stare of the border-industrial complex. Each of these journeys seeks to discover some kernel of the primordial fascination, the lure of the rough country, but also the impulse that drove people to forsake all that they had known and enjoyed and push off into the wilderness of a thousand sorrows, the Great American Desert.

No reckoning with Texas history, however personal, can ignore the foundational experience of the journey, the expedition, la entrada, the filibuster, the crossing. As with many historical adventures, digression emerges as the dominant trope, with each turning from the definitive path leading us farther afield. Growing up in Texas, especially rural Texas, entails long drives to get anywhere at all, and the longest stretch of any transcontinental road trip is always the one that passes through Texas. Whether in the nineteenth century or the sixteenth or the twentieth, Texas was far away, no matter where you were going, and getting there was always hard. Even so, my nineteenth-century ancestors and their fellow travelers never stayed in one place for long. Their lives were but a motion of limbs.

My grandmother Anale Hodge, born in 1920, and I were sitting on the front porch of her house overlooking the Devils River. We were talking about my sons, while her son, my father, was shooting with them at a range he had set up in a small pasture near the house. They fired hundreds of rounds from his elegant bolt-action Sako .22 rifles. Leelee, as we call my grandmother, had come out earlier that day and shot with us as well. She refused to sit at my father’s portable shooting bench, as we did, preferring instead to fire standing up. She wore a kerchief, knotted below her chin, to protect her hair, carefully permed and set, from the relentless wind that whipped down the canyon across an old caliche airstrip, now grown up with prickly pear and mesquite. We shot toward a large earthen berm, at targets and little steel figures of rams, pigs, quail, and turkeys. It was mid-February and the weather was warm and mild, and we were enjoying the rare pleasures of being all together, at the ranch, as a family. My sons and I had been prowling around down by the lake looking for varmints, and now Leelee was curious to know whether there was any water in the riverbed, which is obscured from the house by enormous ancient live oaks. Only a few green puddles in the gravel, I told her, not quite stagnant, home to minnows and frogs. We saw all kinds of scat along the edges.

Targets

Leelee told me about fishing for bass in that lake when she was a girl, about riding her horse through its shallows and swimming there in the summers. She wasn’t allowed to go in the water by herself, of course, so when she was on her own, she’d creep right up to the edge and dig a little channel, line it with rocks, and let the water trickle in to wet her toes. When she caught fish, she’d take them to the cookhouse. “Mother didn’t like to cook them, and she sure wouldn’t clean them,” she said. “There was always a cook there. He cooked for the men. And he always had camp bread that he cooked on top of the old woodstove, and I loved it.” She grew up riding these ranches with the men who worked them. She’d go out gathering livestock in the mornings whenever she was allowed.

Earl, her father, bought the Beaver Lake ranch when she was a girl of eight or ten. He was raised here in the Juno country but was born in Frio County, in South Texas, near the town of Moore. I asked her, not for the first time, how they came to settle out here. You never know when new details will emerge from a story, no matter how many times it’s been told.

“Granny always said they were passing through. They stayed in a little rock house—it’s not there anymore, it was washed away years ago in a flood—down by the lake. Granddad was a great one to want to go look at some other area. He did that,” she paused, as if weighing her words, “too frequently.”

Such understatement! Somebody told T. A. Wilson to go look at the Devils River country, and then, a few years later, in about 1891 as far as I’ve been able to determine, he packed up the family in a wagon or two and came west. My father remembers approaching our south fence through a neighbor’s ranch, along a dirt road in the 1960s, driving his father and grandfather, ascending a steep switchback, when Earl remarked that he remembered climbing that exact switchback in a wagon, when he and his family first moved out to the Juno country.

“Daddy never said this,” Leelee continued, “but Mother said that anytime a good friend or somebody that Granddad particularly liked would come to him and ask him to co-sign a note, he would do it, and then he’d end up paying for it. That happened several times.” Again, that pause. “And it broke him several times.

“He lost the Murrah ranch that way. Somebody named Murrah bought it, and Daddy bought it back.”

But they lived out at the Murrah Place for years before her grandfather—T.A.—lost it, and the children went to school at High Lonesome, another ranch just to the east of the Murrah Place that her daddy later bought as well. There were eight of them, five girls and three boys: Earl was the oldest, then Amy, Beula, Homer, Callie, Beatrice, and Edna; Ernest was the youngest, born in 1900, when Granny moved to town. “She told Mother she was tired of having babies.” T.A. never moved to town. After he lost the Murrah Place, they moved to another ranch, closer to Juno, the Cully Place. But in those early years, in the last decade of the great century of the American continental empire, the Wilson children had to travel for school. They camped for weeks at High Lonesome, where children from other nearby ranches also came and stayed with the teacher. High Lonesome is up on the divide between portions of the Devils River watershed, an uneroded remnant of the great Edwards Plateau. It isn’t flat exactly; the terrain is rolling grassland savanna, dotted with invasive cedar, bounded to the north, south, and west by the meanders of the Devils River, with steep canyons dropping off on all sides. It was, and remains, fantastically inaccessible.

While they were camping at High Lonesome, Earl watched out for the younger children. Once, when they were sitting around a fire, a little fox darted into the light from the outer dark and bit Homer. Well, that was a true emergency, for surely a fox that would invade a fire circle was rabid. Of course there was no rabies vaccine in those days, or any vaccines for that matter, but there was frontier medicine, folk medicine, and people made do with that. Back then everyone on the frontier lived in terror of rabies, which was common, and they kept mad stones as a remedy. A mad stone is an enterolith, a calcium deposit formed in the stomach of cattle and deer and other animals, that resembles a stone but is really more like a pearl that forms around a hair ball or some other indigestible object. The most desirable mad stones came from the stomach of a white deer, and a white mad stone was best of all. Usage was strict; mad stones could not be bought or sold; rather, they had to be found or received as a gift. The wounded person had to be brought to the mad stone, which was boiled in milk and then applied to the wound, which must be open and bleeding, where it would adhere and draw out the poison. When the stone was released from the wound and dropped off, its work was done, and the stone was again boiled in milk, which was supposed to turn green as the poison was released. Mad stones were also used for snakebites. The Wilsons had one back at the house, so Earl took Homer home on horseback, riding long through the dark night, to apply the remedy. Fortunately, the chances of contracting rabies from a single bite are far from certain. Homer lived.

Anale shooting

I got this story not from my grandmother but from her cousin Patricia. Leelee might have heard the story, but she isn’t one to dwell on the colorful details of frontier life. She is the most sensible person I have ever known. She is not sentimental. She does not dwell on the past. She is tough and practical, and she gets on with life when tragedy befalls her. And yet she is full of laughter and joy. In fact, she is probably the most consistently joyful person I have ever known. Her husband, Roger, for whom I am named, died in 1972, when I was five years old. Everyone called him Wally. Anale and Wally were married in 1940; she has been a widow for a decade longer than she was a wife. For those forty-four years she has remained the matriarch of our family and our family ranching business.

When I was a child, I spent countless afternoons playing in Leelee’s big yard on Losoya Street in Del Rio. My grandmother’s yard was a private world, enclosed with high tan brick walls, scarred and pocked by fig ivy removed when I was very small. Within those walls stood tall, majestic pecan trees and a building we called the party house, which contained a precious pool table. Bird feeders always hung from a pecan branch outside her big kitchen window so she could watch the little songbirds as they darted in and out, squabbling and fussing at one another as hummingbirds buzzed and hovered like huge bees. Behind the party house and my grandmother’s plastic greenhouse were corners and shadows and hiding places. Her yard seemed so vast, the walls that bounded it so high. I had my ways of scaling them, and I patrolled that perimeter endlessly, usually with some kind of makeshift weapon, a plastic rifle, a sword, or an improvised stick pistol. When I came to a wooden gate, I would leap down and scramble up again on the other side. Standing on a gate was a terrible sin, for it would ruin the hinges and earn me some grievous punishment from my father, who was likely to come striding suddenly into the yard, shattering my private world, if Leelee spotted me misbehaving and gave him a call.

Next door was my great-grandmother’s house, slightly scary, unwalled, with big white columns out front and what seemed to my young mind to be an enormous grove of magnolia trees. The magnolias were mysterious, and they could be climbed, though I was not permitted to do so. Yet climb I did, because I was a reckless child who never failed to find ways to injure himself. I never fell from those particular trees, though I climbed so high that the slender branches swayed and bent and threatened to break. The terror of falling made my body tingle. The pleasure was intensely sensual. The thrill of that fear was something I never mentioned to anyone. I could not explain it; I had no vocabulary for such feelings. When I threw rocks at hornets’ nests until the angry yellow and black demons attacked me—their stings, to which I was allergic, causing my arm to double in size with the swelling, or my cheek to balloon and sag as if I were chewing a gigantic wad of tobacco, or my eyes to swell shut like a matching pair of hairless puffy alien vaginas—or when I came running with cuts, gashes, scratches, punctures, and other bloody wounds acquired from falling off walls, falling into irrigation ditches, or stepping on rusty nails, my cautious, careful, reserved father would just stare at me and shake his head. He could not fathom such behavior. My recklessness was always a mystery to him. He was convinced early on that I possessed a death wish.

But we were not talking about my errant childhood. I was trying to coax my grandmother into reminiscence, which was never easy. I asked her when the big rock house at Beaver Lake had been built. Although I had plied her with questions about the past before, this was something that I had never asked. She had to think. Well, the house in town, by which she meant her mother’s house with its white columns and magnolia trees, was finished in 1940. She and Wally were married on November 30, and by Christmas, when they came back from their honeymoon, that house was finished. “Mother was furious with me, because we wouldn’t wait,” she said, slightly mysteriously, and did not elaborate. “There were no carpets in the house.” The house at the lake was not finished when my father was born, in 1942, but it was by 1945, when his sister Luralee came along. Leelee was eight or ten years old when my great-grandfather bought the Lake ranch, so it was probably 1930. That date brought me up short, because for me the Beaver Lake ranch had always seemed like the center of my world, but it was a relatively late addition to Earl Wilson’s country.

“Daddy started out at the Juno ranch,” Leelee said, “buying acreage a little bit at a time.” His parents’ ranch was nearby, but he went out on his own. This would have been just after he returned from Galveston, where he had enrolled at a business college. He was in Galveston during the great hurricane of 1900. Everyone thought he had died, Leelee told me once. Of course, communication was slow, and it wasn’t easy to get word about who had survived and who had perished. Eight thousand people died in that storm, which is still the deadliest in American history, and Galveston, then a major port and the largest city in Texas, was leveled. Earl just showed up one day a few weeks later, to everyone’s surprise and delight. He leased his country at first, running sheep and goats, and slowly started buying rangeland near Juno. Eventually, he was able to buy the Murrah Place, the ranch where he had been raised, and he bought the High Lonesome ranch, where he had gone to school, and the Beaver Lake ranch, a historic and beautiful site where soldiers and Texas Rangers and stagecoach passengers had sojourned in the mid-nineteenth century. By the 1930s, he was running the largest operation in the county, with more than thirty thousand sheep and more than one hundred hired men, who worked livestock, built fences, fought the brush, and farmed the fields in the fertile Devils River valley.

Leelee couldn’t say much about Moore or why T.A. and Bettie had left Frio County. She went there as a child many times. They’d be driving to San Antonio and her daddy would take a right-hand turn at Hondo, and then she knew they were going down to Moore to see family. “There are lots of Wilsons down there,” she said. “They had the look. Big and tall.” During the Depression various Wilsons and Crains (Bettie Wilson was a Crain) came to the ranch at Juno to work. “Daddy was a great one for hiring relatives. Wylie Crain lived over in the little house over there. Jesse Crain was working at the Juno ranch. Later Daddy hired Warner, and he drove the big trucks to haul the wool to town. Daddy always said he was the best truck driver he ever had, because when something breaks, Warner doesn’t try to fix it!

“The young man that I just adored, I guess I was just in junior high, was named Dick Edwards, from down around Moore. He had graduated from high school, was a football player, and he was a big husky fella. And he wanted to come out and work. Granny’s father died, I don’t know when, and her mother remarried an Edwards. So this young man was in some way related. And he was good help. He’d been here several years, three or four, everybody liked him. He was a hard worker, and he died out here. They said he had a bad heart or something.

“On Sundays, there at Baker’s Crossing, after you pass the big house on the road, two story, on up a little ways, are lots of these big ole live oaks, and there’s a little house set back there. And at one time the Altizers had that place leased. And on Sunday, all the surrounding ranch people would go down there and everybody would take something for lunch and afterward they’d have roping. The Altizers were big ropers. Sometimes Mother would take a pie or a cake, we’d stop there and visit. Of course all the men were down in the pens watching the roping. And all the men from here would go down for the Sunday roping. We had a whole bunch who always went.

“I always wanted to go swimming. And Mother always said I couldn’t go unless someone went with me. She didn’t swim, so she wasn’t crazy about going with me, but I could always find Warner. He’d be around. He’d go. We’d walk down there, and he’d say, ‘All right, Anale, don’t drown, because I’m going to take my boots off before I come in after you.’ And I could swim. That was his favorite story. ‘If you’re going to drown, take it slow, I’m going to take my boots off.’ Oh, he was a character.

“We’d come out for the weekend, because Daddy would stay out most of the time. If he had a bank meeting or a wool house meeting or something like that, he was always in town for that. He preferred the ranch.”

Earl’s father was the same way. T.A. hated going to town and would do anything to avoid it. Earl would tell him that he needed to go to town for some reason, and T.A. would put it off and put it off until finally he would load up his wagon and set off. Today, with paved highways maintained by the state, the drive from Juno through Comstock to Del Rio takes just over an hour. In the early years of the last century, the trip might take all day. T.A. would take his time. He’d get just out of sight of the house, and then he’d stop and make camp. The rest of the family would see his fire off in the distance. That’s how I imagine him, along the bank of the Devils River, leaning up against a mesquite tree, perhaps burning an old dried sotol bush, shadows flickering on limestone. For more than ten thousand years people have been sitting by fires in that landscape.

Leelee says that she never once saw T.A. lying down, not until he was laid out dead. His allergies and asthma were so bad that he couldn’t breathe unless he was standing or sitting. So he slept in a chair, in front of a fire, covered in blankets. T.A. came by his condition honestly. His father, Perry, like so many westering emigrants, had come to Texas in 1854 searching not only for his fortune but for a healthy climate, a place where he might be able to breathe freely.

Six months later I was back, again with my sons in tow. It was a summer of floods, one year before a summer of fire. Heavy rains generated by Hurricane Alex had drenched the vast watershed of the Rio Grande and the Río Conchos in the Mexican state of Chihuahua, causing the desert to bloom and filling Amistad Reservoir, just west of Del Rio, beyond capacity. Dam officials, fearful of testing the resilience of their fifty-year-old structure, were forced to open all fifteen floodgates; the resulting floods ravaged the communities downriver, tearing up hundred-year-old oak trees and upending homes and businesses all the way to Brownsville, four hundred miles downriver, where the Rio Grande pours its liquid cargo of silt and sewage, tires and nitrogen runoff, into the tepid waters of the Gulf of Mexico. The surviving trees as well as the eternal brush and river cane would for years display countless fluttering plastic bags as a testament to the high-water mark in places like Eagle Pass and Laredo and Roma, where on a bluff far above the river, a short distance from mysterious crumbling circular ruins bounded by barbed wire, you can visit the World Birding Center to learn about Plain Chachalacas and White-Collared Seedeaters.

View of the Rio Grande and Mexico from a bluff in Roma, Texas

We flew into El Paso to see my mother, who for decades lived in that strange and historic community where the Rio Grande flows out of its rift valley, through the Paso del Norte between the Franklin Mountains and Mount Cristo Rey, and assumes its geopolitical role as an international boundary.

Traveling east through the pass, my sons and I were sticking close to the river, visiting family and ancestral landmarks along the way. We soon left behind the blasted and grassless landscape surrounding El Paso and passed quickly through the checkpoint at Sierra Blanca, a town that for years was known as the prime destination for trainloads of New York sewage sludge that were spilled without ceremony upon the barren ground. I rolled down the windows to see if my boys could catch a whiff of their hometown. “There’s a little piece of you out there!” I yelled over the roar of the wind whipping through the cabin of our rented minivan.

We were headed for a place that the Spanish used to call el despoblado, the land without people. I felt uneasy as we continued southeastward. Something was bothering me, but I couldn’t say what it was. At first I told myself it was the checkpoint and the intrusive questioning of the Border Patrol, who rarely fail to ask a driver where he might be going. My father always makes a point of answering, “I didn’t say,” but I had no desire to subject my boys to a confrontation with la migra or to endure a prolonged search of our rented minivan, so I simply answered, “Big Bend.” Still, the ever-encroaching gaze of federal law enforcement, as obnoxious as it might be, was unable to account for my psychological agitation. Finally, I realized what was bothering me: the color of the grass. It was green. It was July in the Big Bend—July in West Texas—and the grass in the Chihuahuan Desert was green.

No one could know that the next summer wildfires would sweep across that very landscape to threaten the towns of Marfa and Fort Davis, as well as our family’s ranch in Juno.

We stopped briefly at the enigmatic and quietly brilliant art installation called Prada Marfa, a modest simulacrum of a big-city boutique, patronized by scorpions and flies and flanked by barbed-wire fences extending toward the horizon. It’s really closer to Valentine than to Marfa, but nobody in L.A. or Brooklyn has ever heard of Valentine, Texas. I decided to skip Donald Judd’s austere minimalist steel boxes, on display at the Chinati Foundation, in favor of maximal exposure to the Big Bend’s infinite basin-and-range vistas.

The Marathon Basin opened before us, a large depression bounded by the Glass Mountains to the northwest and the Del Norte Mountains to the west, various ridges and escarpments rising off to the east. Poking out of twenty-five thousand feet of fossil-laden Paleozoic limestone and shale were hard sharp ridges, known as hogbacks, composed of a variety of chert called novaculite. In places this chert emerged as scalloped white outcroppings called flatirons. Geologists have matched these deposits with Arkansas novaculite, which I’ve read is traditionally used to make whetstones for sharpening knives; they believe the rocks are one and the same formation and that they and the surrounding strata, containing matching fossils of the same age, are the roots of the Ouachita Mountains, a range of Himalaya-sized mountains long ago eroded into sand. Some geologists believe that the Ouachitas were part of the original Appalachian mountain system, bringing together, in this warped, folded, compressed, stretched, and deformed landscape, the bones of the Appalachians with the southeastern vestiges of the Rockies, far younger mountains formed in a completely different episode of mountain building. Thus east meets west at the Big Bend of the Rio Grande.

Prada Marfa, near Valentine, Texas

The Ouachita formation, moreover, traces a long arc from its namesake mountain remnants in Oklahoma and Arkansas down through Texas via Austin, San Antonio, and Del Rio, to the Marathon Basin, a path that limns, through much of its route across Texas, the Balcones Escarpment, which neatly divides the coastal plains of South and East Texas from the stepped plateaus and uplifts that gradually open into the Great Plains. The Balcones scarp corresponds to a wide fault zone, both geographically and culturally. Before the late nineteenth century, when the Plains Indians were finally pacified—that is, conquered and exiled to reservations in Oklahoma—west of the Balcones was the Comanche empire; east toward the gulf lay the Anglo settlements in thin bands along the rivers. And as I was eventually to discover, that fault zone also happened to trace, with uncanny accuracy, a partial map of my ancestors’ nineteenth-century peregrinations.

Our destination was the great basin of the Chisos Mountains in Big Bend National Park, which was part of a large ranch formerly owned by Homer Wilson, my great-granduncle, who tried and failed to make his fortune there as a rancher and quicksilver miner in the 1930s and 1940s. At the time, all I really knew about Homer was that he and his family had lived up there together in a Sears, Roebuck mail-order house. I knew there was a Homer Wilson ranch exhibit in the park, but I had never gotten around to visiting it, and I quickly discovered that I was unable to answer even the most basic questions from my children about Homer’s life. I assumed that Homer had been raised on our family’s ranch near Del Rio, but I didn’t even know that for certain. I could tell my children that their great-great-grandfather Earl was Homer’s brother, but I couldn’t tell them much about his life or how he and his family came to settle and build a ranch along the Devils River, not far from the Mexican border.

From Tornillo Creek, we ascended some three thousand feet up Green Gulch, navigating the looping switchbacks of a road originally built by Civilian Conservation Corps workers in 1934, to Panther Pass and into the Chisos Basin, a very large depression eroded into the center of the Chisos Mountains, which achieve elevations up to seventy-eight hundred feet. We drove through a fog so thick we could hardly see the road or the cliffs just beyond it. Rooms had not been hard to come by at the Chisos Mountains Lodge, because the July heat tends to discourage park visitors, yet there we were, shivering in our thin jackets, sitting on the front porch of our cabin, listening to the strange catlike barks of little gray desert foxes. That night I finally read Beneath the Window, a memoir by Patricia Wilson Clothier, Homer’s daughter and my grandmother’s cousin, whom I could not remember meeting, though I must have known her when I was a child. Homer was a geologist who dreamed of mineral riches in the Big Bend; he sold his share of a sheep and goat ranch near Del Rio and in 1929 began buying land in and around the Chisos Mountains. He married the young widow of his best friend, a fellow geologist who died in an explosion at the Humble Oil Company in East Texas, and in 1930 carried his new bride, Bergine, a city girl who had never ridden a horse or shot a firearm, to live in glorious isolation in what was still the most inaccessible and remote corner of the Texas border country.

Homer ranched about forty-four sections, about half of the old G4 Ranch, a large operation that got started in 1885 with a herd of six thousand cattle ranging across fifty-five thousand acres. Some were shipped by rail to the nearest train station in Marathon. About two thousand were driven overland, more than three hundred miles, from Uvalde through Del Rio, Langtry, Dryden, Sanderson, and Marathon. By the early 1890s the G4 was running some thirty thousand head. It’s hard to imagine the Big Bend country supporting that many cattle, and in fact it couldn’t. Herds of buffalo migrated through from time to time, and the Comanches drove their stolen horses and cattle from Mexico along their great war trail, but these were sporadic and seasonal passages. Sustained heavy grazing was something else. But the grasses were abundant on the virgin pasturage, so at first the cattle thrived. Most ranchers in those days let their livestock drift, because fences were uncommon. They worked the cattle when they had to, when branding or marking calves, and when it was time to drive them to market. Drought came in 1885, and by 1895, when the G4 stock was liquidated, only about half the herd could be located.

The Window, Chisos Mountains, Big Bend National Park

Patricia and her parents lived in a two-story wood-framed Sears, Roebuck mail-order house that was purchased by the ranch’s previous owner, Harris Smith, who hauled his residence some eighty miles to Oak Creek by wagon in pieces from the train station in Marathon. Oak Creek, in Patricia’s telling, was a lovely oasis of willows and oaks enlivened with the sound of running water and the bleating of Angora nanny goats, in the lower reaches of the Chisos Mountains below the Window, an eroded pour-off gap that drains the entire basin, which is three miles across and almost three thousand feet deep at the lip of the Window, its lowest point. During wet weather the waterfall can be thunderous as boulders, carried by Oak Creek at flood, roll and bounce through the opening, dropping seventy-five feet to a jumble of debris below. Casa Grande, capped with a monumental lava formation, stands framed between the Ward and the Pulliam intrusions, two massive igneous formations that compose the poles of the Window gap and enclose the basin to the north and west with their high walls.

Homer raised sheep and goats on his ranch and prospected throughout the Big Bend. Both Ross Maxwell, the first superintendent of Big Bend National Park, and Patricia report that Homer once found a small gold nugget in the Chisos Mountains, but it turned out that the most promising mineral resource in the area was cinnabar, a red crystalline mineral containing mercury. Ferdinand von Roemer, a German scientist who traveled throughout Texas in the 1840s and published the first survey of Texas geology, once traded a rope with some Indians for a small bit of cinnabar. Commercial mercury mining in Terlingua and nearby Study Butte began in the 1880s, which just added to the strange character of the bizarre moonscape of that area. Homer was a partner in the Fresno mine, eleven miles north of Terlingua, that began production in 1940 and supplied mercury to the military during World War II.

Nothing is harder on the land than mining and smelting. The scars seem to last forever, at least in human terms, but the landscape of the Big Bend continually reminds us that even high mountains are cast down in time and deep valleys and basins fill with the eroded debris.

Mining was Homer’s passion, but he seems to have spent most of his time ranching, which was never easy in the Big Bend, or anywhere else for that matter. To reach market, cattle, sheep, and goats had to be driven almost a hundred miles to the nearest rail station, in Marathon. Ranchers like Homer spent their days, which were always too short, fighting predators and improving their property: putting up fences, building water tanks, blasting roads out of the rock with dynamite. Homer took advantage of low sheep and goat prices immediately after the crash of 1929 to stock his ranch, but prices didn’t improve for years. The 1930s were hard for ranchers all over, but they seem to have been especially hard for a sheep and goat man in the Big Bend.

Patricia spent her first fourteen years in the Chisos Mountains. She tells stories of depredations by bandits and mountain lions and coyotes, the perils of flash floods and driving along poor mountain roads. She remembers the challenges of cooking, cleaning, and homeschooling while living many hours’ journey from the nearest paved road. She records the sorrows of Depression-era agricultural economics and the joys of visiting her friend Julia Nail, who lived several miles away with her family on a neighboring ranch. The Depression dragged on; money was tight and the banks were tough on a rancher, demanding detailed accounts of every head of livestock and expense, but at least the Wilsons and their neighbors could grow fruits and vegetables and slaughter a goat or a steer for meat. Ranch work was difficult and dangerous; working horseback in rocky country could lead to death by dragging, when a man, unhorsed, cannot free his boot from his stirrup. Men fell into canyons and suffered broken bones. One man, Patricia remembers, lost an eye to a cow’s horn. Medical help was far away, and when Homer suffered his first heart attack, he was lucky his doctor, visiting for a hunting trip, was standing nearby. Homer never fully recovered.

Meanwhile, the state was forcing ranchers to sell their land for the national park. Some resisted, but Homer knew the state would take the land one way or another. He did his best to secure a fair price. Patricia found him dead on the screened sleeping porch one morning in July 1943. A small bird, trapped on the porch, was flying back and forth trying to escape. She had gone out on the porch to set it free.

Our cousin Jack Ward came home from the army and along with his brother Bill and my grandfather Wally helped Bergine gather and sell off the livestock. In 1945, Bergine left the Sears mail-order house beneath the great Window of the Chisos Mountains and said good-bye to the Homer Wilson ranch for the last time. She and Patricia and little Homer and Thomas moved to Alpine and then to Del Rio. Bergine never returned to the Big Bend.

In my family it has always been said that when the park officials came in and forced out the ranchers, they also killed off the wildlife by removing all the waterings—the header tanks and water troughs and windmills the ranchers had spent years building. Patricia tells a version of this tale in her book, and she said much the same to me personally when I spent time with her and Grant, her husband. She shook her head in disbelief at the rudeness of a park ranger who aggressively challenged her with the accusation that the early ranchers had all overgrazed the land and permanently damaged it. As Patricia remembered it, there was always much more grass on the Wilson ranch in the 1930s than she has ever seen in the park in later years, and she recalled seeing more deer and turkey and other wildlife as well. Two strikingly opposed value systems come into conflict here. The ethos of the rancher, a businessman who always seeks to improve his property and believes that wildlife is a resource that requires careful management, just like any other feature of the land, cannot easily be squared with the ideology of the modern environmentalist, with his dream of a wilderness unmodified by human culture, who seeks to heal the damage committed by thoughtless agriculturalists, miners, and others who exploit the land and seek to extract value from it. At his prudent best, a rancher is a steward of the land, a conservationist who cherishes his property and everything in it; at his worst, he is everything the earnest environmentalist, who strives to re-create an ecosystem that has not existed for more than fourteen thousand years, fears and loathes.

Wildlife thrives where water abounds and cares not whether that moisture comes from a man-made receptacle or a limestone pothole. I have spent time in the Big Bend during dry spells and hardly saw a living creature. That summer with my sons, damp and green as it was, we saw many dozens of deer and uncountable species of birds, including a magnificent black hawk perched in an old pecan orchard along the banks of the Rio Grande. My boys were hoping to see an owl, and we had heard owls haunted that abandoned farm. Driving slowly back toward the basin at sunset, bathed in the last vestiges of a light that can only be called divine, we watched in awe as a great horned owl swooped across our path and landed, wings flapping dramatically, on a thorny stalk of ocotillo, silhouetted against the pale light of the vanishing sun. The next day we hiked down from the Chisos Lodge to the Window, hoping to see either the bear or the mountain lion that were both said to be active in the area. Water alternately seeped and poured down the craggy faces of reddish-brown cliff walls, set off in striking contrast by the almost radioactive green of the grateful grasses and desert shrubs clinging to small patches of volcanic soil, and tumbled down the winding bed of the creek toward the pour off. Mist wreathed the upper reaches of the mountains, winding in and among towering hoodoos, pillars of rock carved by water and wind. One group of hikers we spoke to had seen the bear. Insects buzzed and swarmed, and lizards scrambled out of our way. No one really expected to spot the great cat, because those animals move like ghosts through this country. Spike deer, still in velvet, watched us from patches of brush. Every plant capable of flowering was bursting in a vegetal frenzy of reproduction.

Down in the lowlands, on another day, at one of the few remaining windmills in the park, we played peekaboo with javelinas as they snuffled about in a thicket of mesquite and huisache that had grown up around a water trough and an old leaky concrete reservoir. Driving one bright sunny afternoon, I spotted a coyote as it dashed across the macadam. I pointed it out to my sons, and we pulled over to take a photograph. Oddly, the coyote paused halfway up the barren hill and commenced yapping and barking. This strange behavior continued until we drove on, and that must have been fifteen or twenty minutes. No one I spoke to later, among park workers or my family, had ever seen or heard such a thing before. We could only conclude that the desert canine was calling out a warning to a litter of pups, perhaps in the care of its mate.