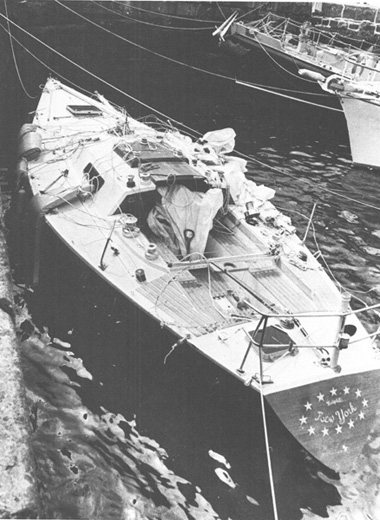

Ariadne on Friday, August 17, moments after she was towed Into Penzance, Cornwall. Cornish Photonews

THE SURVIVORS OF Grimalkin, Trophy, and Ariadne—boats that lost nine of the fifteen men who were killed during the Fastnet race—had immediate concerns other than talking to the press.

After Nick Ward and the body of Gerry Winks were lifted from the deck of Grimalkin, they were flown to Culdrose, where doctors ordered Ward transferred to Treliske Hospital, in Truro. There, he was given medication intravenously, and the doctors told him that his leg, though badly bruised, was not broken. Surgeon Commander C. W. Millar, a doctor based at Culdrose, telephoned Ward’s anxious parents with the happy news that their son had been the 122nd person rescued on Tuesday, August 14.

The last the Wards had heard from Grimalkin was a message relayed on Monday evening by David Sheahan’s wife, who reported that all was well in the boat. Having been kept awake most of Monday night by the strong winds that buffeted their house in Hamble, near Southampton, the Wards arose to the first radio reports of death and destruction in the Western Approaches. Mrs. Ward went to work, leaving her retired husband, Stanley, to worry over the radio. At 12:30 P.M., John Clothier, the Royal Ocean Racing Club rear-commodore who had not sailed in the race, telephoned from Plymouth to say that a life raft containing three survivors of Grimalkin had been found, but that Nick was not aboard. Mr. Ward picked up his wife from her job and they telephoned the bad news to another son and their daughter. With their son, Simon, and his wife, the Wards stood by the telephone and radio much (as Mrs. Ward later recalled) like wartime families waiting to hear news about relatives caught in an air raid. They attempted several times to get through to the RORC office in Plymouth, but the lines were engaged. When their daughter, Cheryl, telephoned the club’s clubhouse in London, she was told to call Plymouth, but she also encountered busy signals. Meanwhile, Mrs. Ward’s brother, who lived in Plymouth, went to the RORC office but there was no news there. The long, agonizing watch over the telephone was finally ended by Surgeon Commander Millar’s call at 9:30.

The Wards drove to Plymouth on Wednesday, where they stayed with relatives and talked to Nick over the telephone. The next day they were allowed to pick him up at the hospital. Among his visitors during his recuperation had been the bishop of Truro, a reporter from the International Herald Tribune, a representative of the Seaman’s Mission asking if Nick needed help in order to return home, Mike Doyle, and Margaret Winks. Nick told Mrs. Winks of her husband’s last moments on the heaving deck of the little sloop and of his message to her.

Several days after his release, Nick Ward joined Matthew Sheahan on a trip to Ireland to inspect Grimalkin, which a fishing boat had towed into Baltimore. Nick remembers sensing tension between them—something he had also noticed when Mike Doyle visited him in the hospital—yet their common interest in the boat seemed to smooth over any harsh feelings about the abandonment of Ward and Winks by Sheahan, Doyle, and Dave Wheeler. They knew from photographs that somebody had gone aboard and cleared away the mess of tangled rigging, and they also knew that the boat was still floating. When the bus they were riding drove down a hill to the harbor, Ward became excited: there was Grimalkin. The driver asked them if they were part of her crew, and they said they were. “Well,” he responded genially, “don’t tell anybody here or everybody in town will want to buy you a drink.” They somehow kept the news of their arrival quiet.

When they went aboard, they found that some money had been taken—possibly by salvagers as reasonable compensation for the rescue—but in most respects she was ready to be rerigged and taken to sea again. Sheahan and Ward set to work cleaning Grimalkin up and planning for future races.

Stanley Ward was not willing to forget that his son had been left for dead. Although he respected Nick’s desire to forgive the three men who abandoned Grimalkin, he made it clear that he thought the decision to leave them was unseamanlike. How strongly his feelings were influenced by his relationship to Nick may be judged from the warm, thankful letters that he wrote to Surgeon Commander Millar and to the parents of Peter Harrison, the young midshipman who had dropped down to the sloop from the Royal Navy helicopter. “It does seem to me,” Mr. Ward’s letter to the Harrisons ended, “that despite the gloom and tragedy which seems to cover our dear land, there is still bright hope for the future whilst young men like your son, and perhaps our Nicholas, flourish and prosper.”

Trophy, three of whose crew died after their life raft split apart, drifted in the Western Approaches for two days before HMS Angelesey, the Royal Navy fishery protection vessel, took her in tow during the gale that sprang up Thursday. While under tow, the dismasted Trophy capsized twice and the Anglesey finally let her go on Friday. She was soon taken under tow again by a power yacht on her way from Sweden to Portugal, which pulled her into Falmouth.

Her owner, Alan Bartlett, became an unwilling celebrity of the disaster because he was the brother-in-law of a popular English comedian, Eric Morecomb. After being interviewed by Nicholas Roe for an excellent story about Trophy’s experiences that appeared soon after the gale in the Sunday Telegraph, Bartlett tired of the attention and stopped talking to writers. Simon Fleming, the ginger-bearded man who had hauled Bartlett out of the water and was later left to drift alone in a section of the raft, shaved off his beard and went back to sailing. During a race the weekend after his ordeal, Fleming discovered two things: first, his arms were so weakened and sore that he was almost helpless in the boat; second, he was frightened, and he several times asked himself if the boat he was in would capsize. He looked forward to sailing in another Fastnet race, but, he has asserted with the same anger that may have kept him alive that cold Tuesday morning, “I’ll never get into a liferaft before the boat sinks. I’ll lay somebody out before I do that again.”

After the Nanna rescued him from Ariadne’s capsized life raft, Matthew Hunt called his mother on the coaster’s radio telephone. Mrs. Hunt was nearly frantic when she heard the news of the gale, for not only was her nineteen-year-old son out in the Western Approaches, but also her husband was aboard Morningtown, the RORC’s escort vessel. Dr. Hunt was no less worried. While Morningtown stood by such damaged yachts as Trophy, her radio blared out reports of distress, among them the deaths of four men from Ariadne. Not until Tuesday night did Dr. Hunt know that Matthew was alive and Mrs. Hunt believe that both her husband and her son were safe.

Matthew himself did not know until Wednesday morning that, as he suspected, Hal Ferris had died. On the front page of the Daily Mail was a large photograph of an airman dropping down to a comatose man floating face up in a life jacket, his hands folded across his chest. Ferris was still breathing when he was hauled into the helicopter, but his eyes were rolled back. Despite continuous mouth-to-mouth resuscitation performed by the airmen, he died during the short flight directly to Truro Hospital. He had survived in the water for over five hours, longer than anyone could have reasonably expected.

First reported sunk, Ariadne was recovered and towed to Penzance, where she lay for almost three months under the care of the Receiver of Wrecks. Apparently she was vandalized sometime between her abandonment and her arrival at Penzance, the intruders cutting through the bulkheads that separated the cabin from the cockpit, perhaps to remove electronic instruments that Hal Ferris and his crew had installed so carefully. In early November, she was hauled out of the water, placed on a flatbed truck, and taken to Plymouth to be sold.

Matthew Hunt was a sad young man when he returned to his home near Colchester, in Essex, and the public response to the race and to Ariadne’s tragedy did nothing to cheer him up. Few people knew much about the boat except that her owner had been an American and that she had lost more people than any other yacht in the race. There were nuisance telephone calls and outright criticisms in the press of the crew’s seamanship. Matthew and Rob Gilders visited with Bob Robie’s widow and sons, who were eager to know what had happened, and they attended David Crisp’s funeral. Matthew’s strong, supportive family and friends rallied around and tried to cheer him up. His friends were able to convince him to learn the exuberant sport of windsurfing, and he was made happy by the news that he had been accepted into medical school and so could follow in his father’s footsteps.

An airman drops down to Frank Ferris, the owner of Ariadne. Mora than any other photograph, this one, published in newspapers worldwide, spoke of the horror of the Fastnet race storm. Barely alive when this was taken, Ferris died In the helicopter on the way to the Truro hospital. Royal Navy

In late August, stung by attacks on Hal Ferris’s judgment by Bob Fisher, yachting correspondent of the Guardian, Matthew Hunt wrote the following letter, which soon was published in the newspaper:

Sir: I would like to reply to an article by Bob Fisher in which he criticizes people in the Fastnet race for ignoring safety “rules.” He made particular reference to the yacht Ariadne as an example of a boat whose crew abandoned ship when it was not necessary.

I entirely agree that one should stay with the boat for as long as possible. In my opinion, however, and in the opinion of all the other people on the boat, this is what we did.

On the first roll, we lost the mast, half-filled with water, and a man was badly injured. On the next roll, we lost a man. Had we done a third roll, which was almost inevitable, we might have lost another man or been badly injured by the hard-pointed interior of the boat; we might have sunk without being able to launch the life raft; or we might have lost the life raft—who knows?

Also, having been bailing the boat for a long time, we would probably have been too exhausted to cope with another knockdown.

I also feel it is worth mentioning the terrific feeling of security once we were in the life raft, and I’m sure that the psychological boost gained from this enabled us to keep going for a few minutes longer—very valuable moments in my case.

Matthew Hunt

Colchester, Essex

Although several bodies of men thought to be Fastnet race fatalities were discovered in fishing nets pulled aboard trawlers along the Cornish and Irish coasts, the remains of Bob Robie and Bill LeFevre were not found. Neither was the body of David Sheahan, owner of Grimalkin.

Memorial services were held for the Fastnet dead in Sydney, Australia, Cowes, and, in November, the RORC’s own service at St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields church in London. The lord mayor of Plymouth established a fund for the families of men who had died in the race to which almost £21,000 (over $45,000) eventually was contributed—£12,000 ($26,000) by the Australian government. The Royal National Life-boat Institution directed a special appeal to non-British sailors who had sailed in the race. The British Yachting Journalists’ Association awarded its annual Yachtsman of the Year award not to a race winner, as is the custom, but to Alain Catherineau, skipper of Lorelei, the French yacht that had saved seven survivors from Griffin. Some Americans proposed an award that would honor the memory of those who died in the race by being given to racing sailors who display conspicuous gallantry and seamanship in rescue attempts.

After the general-audience press moved on to other subjects, the autumn issues of British, European, and American yachting magazines were filled with technical studies of the storm itself and of what might possibly have gone wrong, most of them written from a practical, what-can-we-learn-here point of view. Only in the regional news columns of an English magazine, Yachting Monthly, was the intensely human side of the tragedy replayed from month to month as local correspondents mourned the deaths of friends, repeated accounts of individual experiences aboard boats that survived the storm, described the heroism of the rescuers, and praised the warm reception provided to distressed yachtsmen by harborside towns—particularly those along the coast of Ireland.

Except in those columns, the flood of descriptions, analyses, and opinions died down in November as everybody awaited the report of an inquiry into the race that was conducted by the Royal Ocean Racing Club and the Royal Yachting Association. Apparently worried about possible government interference in their activities, and obviously desirous of learning as much as possible about the storm and the ways in which crews and boats reacted to it, the inquiry committee devised and mailed to each of the skippers three copies of a questionnaire that asked about the race in enormous detail, with more than 230 questions. The survey was about as thorough as one could hope, although it did take some things for granted. For instance, when it asked the skippers for information about barometer readings, it assumed that all boats carried barometers. Most did; this is the most basic means of evaluating weather. One boat that did not was Aries, Michael Swerdlow’s forty-six-footer that was a member of the American Admiral’s Cup team, whose crew apparently felt that weather broadcasts would tell them all they needed to know. In addition, since the questionnaire would be evaluated by a computer, many of the answers were in a “yes/no” format. There was no provision for “maybe,” which sometimes was the only possible answer.

In any case, the inquiry received back completed forms for 235 boats, plus forms for another 30 that were returned too late for evaluation. The final seventy-six-page report released on December 7, less than four months after the gale, was based on the experiences of 78 percent of the boats in the fleet. (Since the questionnaires were to be distributed by each skipper to the two most experienced crew members, a total of 669 actual questionnaires were returned; the committee did not describe how it handled differences of opinion between crew members in the same boat.)

Briefly, the report confirmed that this storm was something special. About 70 percent of the respondents estimated maximum wind speed at force 11 or above (fifty-six or more knots), and the significant (or largest average) wave height at greater than thirty feet (44 percent thought the largest waves were forty feet or more in height). The effects of this seaway were extraordinary. Forty-eight percent of the boats reported knockdowns to horizontal or almost horizontal. Thirty-three percent reported that they had experienced a knockdown beyond horizontal, including a 360-degree roll—a total of seventy-seven boats. (Unfortunately, the question was misleading and it would have been easy to indicate that a rollover had been experienced even if a boat was knocked down to just beyond horizontal. Conservatively assuming that only half of those boats—thirty-eight—were actually rolled over entirely, one-eighth of the entire Fastnet fleet still experienced the catastrophe of a complete capsize.) Of the twenty-three respondents who abandoned their boats, all but one experienced a complete rollover, and while a disproportionate number of smaller boats were rolled entirely over, six of the forty respondents in Class I (boats between about forty-four and fifty-five feet) claimed to have been rolled over.

While there was data to suggest that the lighter, shallower boats such as Grimalkin, which have become popular in ocean racing over the past two or three years, may have been more vulnerable to these catastrophic knockdowns than heavier boats such as Toscana, the inquiry committee was not able to state absolutely that a causal relationship existed between the type of boat design and ability to take the seas in the Western Approaches. Forty-three percent of those knocked over answered yes to the question, “Would any boat of similar size inevitably have suffered a knockdown?” (the same percentage did not answer and only 13 percent answered no).

Some other data: 14 percent experienced “significant” structural damage, 11 percent suffered damage to steering gear, and 18 percent suffered “significant” damage to the mast. One-third said that entry of water was a problem; 11 percent said that the amount of water in the boat affected the decisions that were made. Serious injuries occurred below in 5 percent of the boats, almost all of them during rollovers. Eleven percent of the respondents experienced at least one instance of safety harness failure. Twelve life rafts were washed overboard, and of the fifteen that were used, five capsized.

The inquiry addressed the questions of crew experience and knowledge by asking how many long-distance races of various lengths the skippers had sailed and then factoring the results against the record of knockdowns and damage. Experience levels were high. Seventy-seven percent of the skippers had sailed in seven races between one hundred and two hundred miles long, 56 percent had sailed in seven or more races between two hundred and five hundred miles long, and 55 percent had sailed in at least three races longer than five hundred miles. A slightly disproportionate number of the less experienced skippers experienced rollovers and hull or rig damage, and a disproportionate number of the most experienced skippers did not have problems—-but once again, the differences are small.

What was the greatest danger? “Steep breaking sea”—44 percent; “knockdown/capsize”—16 percent; “crew injury,” “man overboard,” and “rig damage”—6 percent each.

Answers to various questions indicated that all four traditional storm tactics—lying a-hull, running before it with warps dragging and without warps dragging, and heaving-to—worked about equally well. Three-quarters of the respondents said they would use the same tactic again. In the words of the committee, “No magic formula for guaranteeing survival emerges from those who were caught in the storm. There is, however, an inference that active rather than passive tactics were successful and those who were able to maintain some speed and directional control fared best.” That certainly was the experience in Toscana, Police Car, and Lorelei, whose skipper found that he could conduct the rescue only when he approached Griffin’s life raft at speed. The committee concluded that other factors at play in avoiding bad knockdowns included the skill of the helmsman and whether or not a boat was unlucky enough to be caught by an especially bad wave. While Britain’s Institute of Oceanographic Sciences told the inquiry that the Labadie Bank could not have influenced wave height or shape, 57 percent of the respondents to the questionnaire felt that the depth of water affected the sea conditions.

The crews that abandoned their boats believed that the risk of staying on board was unacceptably high, the committee reported, although two boats “were abandoned simply on the grounds that the life raft was likely to provide more security than the virtually undamaged hull of the yacht.” (The inquiry committee did not cite by name boats other than the three that rescued competitors.) The committee praised the rescue services and, while pointing out that error is inevitable in such unusual conditions, the seamanship, navigation, and courage of the yachtsmen themselves.

Neither two-way radios nor a smaller fleet nor any other single factor would have forestalled disaster, the committee appeared to conclude. This was an experienced group of sailors exposed to an exceptionally severe sea condition. Some of the boats may not have been quite as stable as they should have been, and some equipment should have been stronger, yet as elucidated in the report’s last paragraph, the lesson was: “In the 1979 race the sea showed that it can be a deadly enemy and that those who go to sea for pleasure must do so in full knowledge that they may encounter dangers of the highest order.”

Whether drawn from narratives or statistics, this lesson did not at first seem universally understood—or, if it was, it may have led some people into and not away from great risks at sea.

On September 21, five weeks after the storm, thirty-two men and women started a race from Penzance to the Canary Islands, from where they would race to Antigua. Each sailor was alone in a boat no longer than twenty-one feet. Twenty-five boats had finished at Tenerife by late October. Of the others, three sank, two quit the race because of leaks, and two more were not accounted for. Fortunately, nobody died. In the 1977 running of this race, which was called the Mini Transat, two people were lost.

While this race was under way in the autumn of 1979, a Massachusetts real estate investor named John Tuttle was preparing his boat and a crew for a sail across the North Atlantic Ocean. Desperado, an extremely lightweight 57-foot sloop, was waiting in New York City for a gale with which she could tag along as it crossed the ocean. Turtle’s goal was to break the record of a bit over twelve days for the fastest transatlantic passage by a sailing vessel, set in 1905 by the 185-foot, three-masted schooner Atlantic. When the propitious storm appeared, Desperado got under way. On December 8, her mast damaged, and several sailors injured after encounters with two gales, Desperado was abandoned in mid-Atlantic by her nine crew members, who were picked up by a British container ship. “When the mast was jammed into the trough” of a forty-foot wave, Tuttle told the New York Times, “we stopped like we had hit a brick wall. Food exploded out of the refrigerator and flew into the navigation station. Cottage cheese became a lethal weapon.”

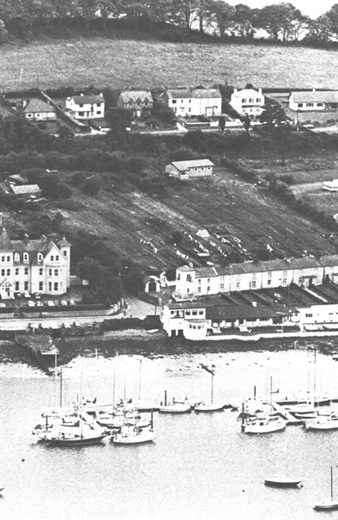

The Irish yachting port of Crosshaven. Some of the yachts which abandoned the race made fast near the Royal Cork Yacht Club. Irish Times

Later that month, during a gale off the coast of Australia, a yacht named Charleston went down with five hands while being sailed to the start of the race from Sydney to Hobart, Tasmania. Charleston was a new, untested thirty-five-footer. A few weeks after Smackwater Jack, a well-tried boat of about the same size, disappeared during a storm while she was returning to New Zealand from the finish of the race. In her four-person crew were her designer, Paul Whiting, and his wife. That same storm forced Condor of Bermuda, the huge sloop that had been first to finish the Fastnet race, to lie under bare poles for three days in seas reportedly as high as fifty feet. While nothing more may ever be known about the loss of the nine sailors, surely these victims of the sea—like the fifteen men of Grimalkin, Trophy, Ariadne, and the other unlucky yachts in the Fastnet race—had rushed willingly down the hills to the water, only to find themselves caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. Who should judge whether they were there for the wrong reason?