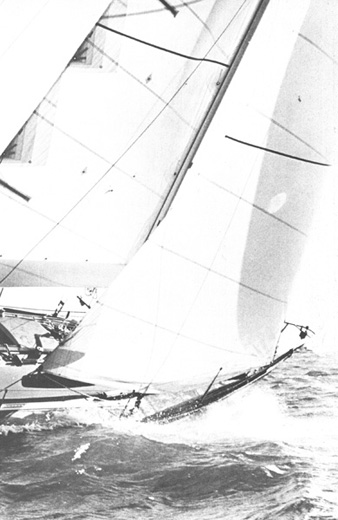

Grimalkin racing under number-2 jib and single-reefed mainsail in a force 5 (seventeen- to twenty-one-knot) breeze before the Fastnet race.

THE ABANDONMENT OF Grimalkin was also the abandonment of high hopes. David Sheahan, her owner, was one of thousands of middle-class people who were attracted to the sport of ocean racing, looking for escape from the pressures of organized, professional life ashore. Fastnet race fleets had doubled in size since the late 1960s, and the sport boomed everywhere as more disposable income and leisure time became available to an increasing number of people. Away from land for several days at a time, fighting the weather and the sea in relatively small sailboats, men and women could regain touch with the satisfactions of working together in a natural environment—satisfactions that were a part of normal everyday existence before work became stratified, individualized, and air-conditioned.

The virtues of the discomfort of an ocean-racing yacht—wet clothes, lack of sleep, bunk sharing, and the constant pressure to outrace frequently invisible competitors—are difficult to explain yet addictive. For the men and women who keep returning to the Fastnet and other long-distance races until they are on the verge of old age, the lure is not the hope of winning trophies. Perhaps the sport provides a means of rediscovering some lost part of their primitive nature, unsullied by civilized life. In the 1970s, yachting went through a technological revolution as space-age materials and electronic instruments found their way into boats that were becoming increasingly fast and difficult to sail well. Many younger sailors seemed to respond to these challenging developments with the enthusiastic delight of racecar drivers and mechanics first encountering turbocharged engines, and the satisfactions of sailing in an ocean race may have been less important in their minds to the pleasures of winning. Yet for the twenty-seven hundred or so people in the 1979 Fastnet race, the attractions of the sport were the same ones that had encouraged ninety men to sail in nine yachts in the first Fastnet race, in 1925.

Like a great many of the people in the 303 boats that started the Fastnet race on August 11, David Sheahan had only recently discovered ocean racing. An accountant in his early forties, he had raced in dinghies and other day-sailing boats for many years before buying Grimalkin. Thirty feet long, she was almost the minimum size for most of the important distance races sailed off England, but she had a pedigree. Her designer was Ron Holland, in the past five years probably the most successful architect of ocean-racing yachts. She was built of fiberglass by the distinguished English firm of Camper and Nicholsons. Her shape, construction, rigging, and equipment were as modern as those of most of her competitors. Sheahan did his best to supplement his boat’s inherent speed and strengths with careful organization for the many races he entered. Some boat owners set aside the conscious, orderly sides of their natures when they make the transition from work to pleasure, but he approached yachting with the same attention to detail that he showed in his profession.

The six-page memorandum that Sheahan sent to his crew before the Fastnet race began with a description of the course. The race would start in the early afternoon on August 11 off the Royal Yacht Squadron, at Cowes, on the Isle of Wight. The course was 605 miles long: from Cowes down the southwest coast and around Land’s End; across the Western Approaches and around Fastnet Rock, which lies eight miles off the southwest tip of Ireland; then back to England and around the Isles of Scilly and on to the finish at Plymouth. Grimalkin would sail in Class V, reserved for the smallest boats, and she might be at sea for more than six days.

Sheahan then reported that the safety gear, which included a rubber life raft inflatable by a CO2 cartridge, flares, and equipment to aid in the rescue of crew members who had gone overboard, would be examined by Camper and Nicholsons. They would also make a repair to the yacht’s rudder. He planned to carry six gallons of diesel fuel, enough to run the engine for twenty-four hours in order to charge batteries and “to give ourselves a safety margin in case of problems.” And, he wrote, “The insurance of the boat and its contents (i.e., the crew) has been extended to take in this race, which is beyond our normal cruising (sic!) limits.” Grimalkin never went on cruises, and her normal insurance applied only near her home waters, on the Solent near Hamble. Sheahan then discussed safety. Although the first-aid kit would be “upgraded to a more suitable level for this event,” each crew member was responsible for his own special medication. He recommended that each make an appointment for a prerace dental checkup, and flatly reported that nobody on board had special medical training.

The 605-mile Fastnet race course. Shown are the main headlands and turning points. On the way out to Fastnet Rock, the Isles of Scilly may be passed on either side, but on the way back from the Western Approaches, they must be passed to the south.

Since space was limited in the little boat (food would be stored in clothing lockers), everybody was expected to bring aboard only one duffel of sailing clothes. Shore clothes, Sheahan ironically noted, would not be necessary “as we will break with our normal tradition and not dress for cocktails or dinner.”

As for provisions, Sheahan expected the crew to share equally in the cost of food, for which he and a crew member, Gerry Winks, would shop. Although he had increased Grimalkin’s water capacity to twenty-five gallons, Sheahan wrote, washing and cooking would be done in sea water, and to provide a reserve for emergencies, fresh-water consumption would be limited to three gallons a day. He asked the crew to notify him if there were special dietary problems.

Continuing with his concern about emergencies, Sheahan noted that he planned to talk daily over marine radio with his wife, who would be able to transmit any messages to families. “It might not always be possible,” he cautioned, “so make sure that your family, etc., won’t worry unduly if there is no news to pass on.”

Taking almost an entire page, Sheahan detailed the crew assignments. He would be skipper and navigator; Gerry Winks would be second in command; Mike Doyle would back Sheahan up “to ensure that in all circumstances we have a navigator”; his seventeen-year-old son, Matthew, would be in charge of the foredeck and sail changes; Nick Ward would trim the spinnaker; and Dave Wheeler would help Matthew on the foredeck. They would all take turns steering and cooking. Grimalkin’s watch system, described in the memorandum in a two-page chart, had two men on deck at all times. Each of the five men who stood watch (Sheahan would be busy navigating) would alternate four hours on deck and four hours below, and during the race each would take one twelve-hour period off the watch schedule to cook.

Sheahan ended his memorandum with instructions to be aboard Grimalkin at 8:00 A.M. on the eleventh and with a final reminder: “We have maintained a high standard of personal safety on board, let’s retain it for this event.”

Although no skipper preparing for the Fastnet race should have been unaware of the potential for bad weather—strong winds often are as much a part of sailing off the English coast as light winds are prevalent on Long Island Sound in America—Sheahan’s relative lack of experience may have made him more cautious than many Fastnet race veterans. The previous three races, in 1973, 1975, and 1977, had been sailed in light winds and calms in which the main worry had been food and water shortage, not first-aid equipment.

Safety harnesses that restrain crew members from being flung overboard, life jackets and life rafts, fire extinguishers, first-aid kits, emergency rations—all were required of Fastnet race entrants by the sponsor, the Royal Ocean Racing Club (RORC). Yet a man who worries about whether his crew will suffer toothaches is not a man to take chances. The RORC did not require Sheahan to carry a radio transmitter. A receiver capable of picking up marine weather broadcasts was the only radio that Grimalkin and most of the other Fastnet entrants had to have aboard. (The exceptions were the fifty-seven boats in the Admiral’s Cup competition, which were required to carry transmitters. In 1979, the Admiral’s Cup, an international championship for ocean racers sailed biennially in Fastnet race years, included three-boat teams from nineteen nations, among them the United States, Poland, Hong Kong, Brazil, Ireland, Australia, and Great Britain.) Even though he was not required to do so, Sheahan equipped Grimalkin with three very high frequency (VHF) marine radio transmitters and receivers, two of which were powered by the boat’s battery, and one of which could be used in a life raft if necessary.

Sheahan also went beyond the regulations to equip his boat with jackwires along the decks and in the cockpit (in nautical parlance, “jack” means “utility”). In rough weather, his crew could hook the snap hooks at the end of the six-foot tethers on their safety harnesses to these wires so they would be securely attached to the boat as they worked on deck or sat in the cockpit. The racing regulations required only that Grimalkin be equipped with lifelines running fore and aft two feet above each rail, suspended on stainless-steel posts called stanchions. Both the stanchions and lifelines were vulnerable to damage by a broken mast or by a man thrown against them, and Sheahan felt that, in the worst possible situation, the jackwires were more dependable restraints against a man’s being flung into the sea.

David Sheahan’s concern for safety may have been motivated by knowledge that his crew was, in a way, flawed. Gerry Winks, the first mate, was arthritic, and Nick Ward, the sail trimmer, was an epileptic. Neither case was serious, and with the proper medication the two men were able to lead normally active lives. Yet doctors had advised Winks not to sail. He ignored that advice. At age thirty-five, Gerry Winks aspired to being a successful yachtsman with all the eagerness of a young boy hoping to score goals in a soccer World Cup. His spare time was devoted to boats: sailing in them, reading about them in books and yachting magazines, planning for the day when he could be skipper of his own ocean racer in a Fastnet race. “The Fastnet is either the beginning or the end,” he told his wife before setting out in Grimalkin. “I’ll know myself as a racing yachtsman after this.” If he proved himself by meeting his own high standards in this race, he would try to join the crew of a larger boat, and then onwards until he could afford his own yacht—regardless of doctor’s orders. But until then, he would do his best to help David Sheahan win in Grimalkin.

When Nick Ward was sixteen, he suffered a neurological attack that left him partially paralyzed. Technically an epileptic, he had little or no feeling in his left side, although he was able, with medication, to stay active, ride his bicycle, and continue sailing dinghies. He took waterfront jobs in boatyards, marinas, and chandleries, and by the time he was twenty-four, he had helped deliver many yachts across the English Channel and the Bay of Biscay and had endured bad weather offshore. His knowledge, experience, seriousness, and intensity made him a valued member of racing crews. David Sheahan sought him out and asked him to come aboard Grimalkin for the 1979 racing season. His only failing afloat was clumsiness in the galley. While cooking during a race in the Channel, he allowed a plastic spatula to melt in a frying pan. Sheahan, who knew the importance of barracks humor to a group of men under pressure, turned the incident into a running joke, announcing in the pre-Fastnet race memorandum that Ward was scheduled to take the first tour as cook just after the start “whilst we still have a packed lunch,” and labeling the new spatula “The Nick Ward Memorial.”

Grimalkin’s crew members were in high spirits when they boarded her at Hamble, near Southampton, early in the warm, sunny morning of August 11. They stowed their seabags and cast off the dock lines, and as Grimalkin made her way under power out toward Cowes, they sang loudly and waved cheerily to friends on the pier. Margaret Winks, Gerry’s wife, was there to send them off, and the possibility of danger never crossed her mind as she watched the boat and her crew head off into the light south-west breeze.

Like Grimalkin and other boats in the race, Toscana was rigged with jackwiras that ran the length of each deck and a crew member could go all the way forward to the bow without having to unclip his safety harness

Since a crew member coming on deck is not sturdily supported, he should pass the tether and hook over the washboards to another crew member, who may hook it to a jackwire

The helmsman must be securely hooked to the jackwire. On many boats rolled during the night, helmsmen were thrown from the tiller or wheel right over the lifelines. This jackwire was permanently rigged in the cockpit on Innovation, whose owner, Peter Johnson, here demonstrates its use. John Rousmaniere

Class V was the first group to start from the line that extended from transits on the castlelike clubhouse of the Royal Yacht Squadron to an outer distance buoy over one mile out in the Solent, the narrow body of water that separates the Isle of Wight from the English mainland. Fifty-eight boats crossed the line in Class V, while the 245 larger boats in Classes O, I, II, III, and IV, and a flock of photographer, press, and spectator boats swarming about, somehow avoided collision. A strong tidal stream pushing the boats toward and over the starting line further confused the situation. Sheahan was not intimidated. Grimalkin had an excellent start and held her own against larger boats as she tacked to windward, working her way toward the Needles, the chalk cliffs that guard the west end of the Solent.

The south-west wind held steady for the next two days, rarely blowing less than ten or more than fifteen knots as the massive fleet of racing yachts sailed as closely as they could in its direction, first on one tack and then, after a wind shift of a few degrees, on another. The sea was calm and the only discomfort was the minor annoyance of living in a world that was tilted twenty degrees. Grimalkin encouraged her crew by continuing to sail near boats ten to fifteen feet longer and potentially much faster as most of the huge fleet sailed close along the English shore to try to avoid strong contrary currents. David Sheahan endured the bout of seasickness that often afflicts even highly experienced offshore sailors on their first day or so at sea. When he recovered, he used one of the radios to call a marine operator, who connected him to his home telephone, and he told his wife that they were comfortable and sailing fast.

Like most of the Fastnet race entries, Grimalkin’s crew depended for weather forecasts on the British Broadcasting Corporation’s four times daily shipping bulletin on the long-range Radio 4. The forecasts had been almost exactly the same since Friday: southwesterlies of force 4 to force 5, with the chance of a force 7 or force 8 gale near Fastnet Rock on Monday, the thirteenth. In the Beaufort scale of wind and sea conditions, used by most seamen and yachtsmen to describe the weather, force 4 (“Moderate Breeze”) is an average of eleven to sixteen knots of wind (one knot is equal to 1.1 miles per hour), so the lower ranges of the forecast certainly were correct; only occasionally did the fleet feel the seventeen to twenty-one knots of wind of force 5 (“Fresh Breeze”). Force 7 (“Moderate Gale”) and force 8 (“Fresh Gale”) encompass wind strengths of between twenty-eight and forty knots, which every sailor in Grimalkin and her competitors must have experienced at least once in their sailing careers, and, which, probably, they all desired for at least part of this Fastnet race.

The forecasts duly came at 12:15 A.M., 6:25 A.M., 1:55 P.M., and 5:50 P.M., and the wind and the barometer held steady at the relatively high pressure of 1020 millibars (30.1 inches), yet the thick fog that shrouded the boats most of Sunday was not evidence of the kind of stable fair weather that those indicators normally point to. The fog cleared away Sunday night and was replaced just after dawn on Monday by a flat calm. The air sat motionless between thick puffy clouds and a greasy sea undulating monotonously to the rhythms of the groundswell that rolls in soundlessly from the Atlantic. The groundswell is propelled by the southwesterlies that are ubiquitous except when a cell of low atmospheric pressure, called a depression, sweeps east from America to cancel out the effects of the great stable Azores high-pressure system. Grimalkin rolled uncomfortably in these waves as her crew looked aloft for any indication of wind in the sails. After several hours, a breeze filled in quickly from a new direction—the north-east—and her crew soon had Grimalkin decked out in a spinnaker to take advantage of the new wind from astern. As she cleared Land’s End and stuck her bow out into the Western Approaches, she was propelled at eight knots, almost twice the speed she had been making on the two-day, 210mile leg into the wind down from Cowes.

Once again, the thirty-footer was staying even with larger boats, and her crew had every reason to feel satisfied. But for those who looked up into the western sky early Monday afternoon, there were other things to think about. The clouds were darkening to the point where Nick Ward thought them “terrific.” The barometer had dropped slightly, to 1010 millibars (29.8 inches), and, with the strengthening wind that was slowly veering from north-east to east to south-east, there was reason to suspect that some bad weather was on the way. Yet the 1:55 P.M. BBC shipping bulletin for sea area Fastnet was: “south-westerly, force 4 or 5, increasing 6 or 7 for a time, veering westerly later. Occasional rain or showers.” That said only that a depression would be passing through with no more wind than had previously been forecast, but with a shift in wind direction to the west. Despite the clouds and the groundswell, which seemed to be growing higher, there was little in the wind or over the radio frequencies to cause even the most cautious sailor to consider turning back and heading for a protected harbor.

Start of the Fastnet race at Cowes. In a force 3 breeze, Claas II beats past spectator boats. William Payne

By late Monday afternoon, the wind had shifted to the southwest and had increased to twenty knots, with occasional puffs of twenty-five. Grimalkins crew doused her spinnaker, and, heading west-northwest toward Fastnet Rock, she burst over and sometimes through the swells at exhilarating speeds, under mainsail and genoa jib. At 5:50 P.M. the precise yet sympathetic voice of the BBC announcer presented the shipping bulletin, the relevant part of which was, “Mainly southerly 4 locally 6, increasing 6 locally gale 8, becoming mainly north-westerly later.” He also located a depression two hundred and fifty miles west of the Fastnet area that the British meteorological office expected to pass to the north.

The six men in Grimalkin were not surprised by this news, for it was not the first mention of a force 8 gale. Yet a forecast two hours later from another source painted a new and much more worrisome picture. At about 8:00 P.M., a French-language broadcast anticipated a force 8 to force 10 gale, with stronger gusts. Called a “Whole Gale” or “Storm” in the Beaufort scale, force 10 conditions are considerably more severe than force 8. Force 10’s forty-eight- to fifty-five-knot winds are some twenty knots stronger, and its thirty-two- to forty-foot waves are as much as twice as high. Most significant is the violence of force 10 waves. The description in the Beaufort scale is “Very high waves with long overhanging crests. The resulting foam in great patches is blown in dense white streaks along the direction of the wind. On the whole the surface of the sea takes a white appearance. The tumbling of the sea becomes heavy and shocklike. Visibility affected.”

The maelstrom described in those five sentences and phrases is entirely more vicious than a force 8 sea, in which there are “Moderately high waves of greater length [than force 7 waves]; edges of crests begin to break into spindrift. The foam is blown in well-marked streaks along the direction of the wind.” Force 10 is to force 8 what stomach cancer is to gallstones.

David Sheahan and his crew knew the difference between force 10 and force 8, and the French broadcast worried them. Grimalkin, it seemed, was now heading straight into a major storm. Another Fastnet race boat, later remembered as Pegasus, also heard the forecast, and her crew called the Land’s End Coastguard station over her marine radio to ask if the French had been correct. By the rules of yacht racing, this was illegal, since Pegasus was soliciting outside help, but the action is understandable given the circumstances. The coastguards’ response was that the BBC forecast was the correct one. Overhearing both the question and the answer, Grimalkin’s crew breathed more easily. Yet the barometer had dropped to 995 millibars (29.4 inches), the wind had increased to thirty knots, the waves were building in size, and the boat was beginning to pound uncomfortably. The sun set at 8:26, its rays mostly hidden by low scuddy black clouds flying over water now broken by spray and whitecaps.

David Sheahan could not know that the French forecast had been accurate. Grimalkin was about to rendezvous with a compact, violent storm that had traveled over five thousand miles in four days to sweep across the Western Approaches during the precise hours when those waters would be crowded with small racing yachts.

“Depressions are born, reach maturity, and then decline and die,” the English weather specialist Ingrid Holford writes in The Yachtsman’s Weather Guide. “They travel in their youth and stagnate in their retirement; some are feeble from birth and never make a mark on the world, while others attain a vigor which makes them remembered with as much awe as a hurricane.” This storm had already made its mark.

The storm was born in the northern Great Plains of the United States, where hot air over baking wheat fields frequently tangles with cold Canadian air to produce tornadoes and violent thunderstorms. Often, these tiny, vicious depressions do their worst damage immediately and are quickly gone, their energy dissipated in wind, rain, and hail. But this storm had a force that kept it alive long after it dropped over an inch and a half of rain on Minneapolis, Minnesota, on Thursday, August 9. From there it headed east across northern Lake Michigan, upstate New York, and New England. Its greatest effects were to its south. On Friday, sixty-knot wind gusts blew the roof off a tollbooth on the New Jersey Turnpike and knocked down power lines and tree limbs, one of which killed a woman walking in Central Park, in New York City. That afternoon, severe wind and rain squalls swept across Connecticut and into Narragansett Bay, in Rhode Island, where the twelve-meter yacht Intrepid was practicing for the 1980 America’s Cup trials. One of her wire jib sheets broke and hit a crew member with such force that he thought his arm was broken. Nearby, seventy-eight boats competing in the world championship of the J-24 sailboat class were swept by unpredictable, violent gusts from the south-west and northwest. Three boats were knocked over until their masts touched the water. The boats finished the race under a black sky and made it safely into the protected harbor of Newport just before the Coast Guard issued an alert warning all sailors to seek shelter. Sheets of rain drenched the town, and a fifty-knot wind broke windows and threatened to blow over a large waterside tent. One sailor, Mary Johnstone, thought that this thirtyminute period of rain and wind was as wild as some of the hurricanes she had experienced during her many years of living in New England. That night, northwest squalls swept across the crowded harbors of the islands off southern New England, and dozens of yachts containing vacationers dragged their anchors. Moving east at speeds as high as fifty knots, the swirling cell of violent air was over Halifax, Nova Scotia, at about the time the Fastnet race started on Saturday, and was in the open Atlantic a day later.

So small and fast moving was the storm that meteorologists had difficulty keeping a precise track of it, and some of the weather maps compiled every six hours by the United States National Weather Service show it only as an area of low pressure and not as a distinct depression encircled by isobars, or lines of equal barometric pressure. The weather map published in British newspapers over the August 11–12 weekend identified the depression as “Low Y” that would “move quickly east and deepen” to cause the force 7 winds predicted for Monday.

In meteorologists’ terminology, this was a “shallow” depression with an atmospheric pressure of about 1008 millibars (29.8 inches) at the lowest. A “deep” depression might have a pressure of less than 995 millibars (29.4 inches). Differences in atmospheric pressure are what create weather and, in particular, wind. Hot air and damp air are less dense than cool air and dry air. The less dense air has a lower pressure than the dense air and creates depressions in the atmosphere in the way a prolonged rainfall creates valleys and basins in a beach. Into these depressions pours cooler, more dense air from surrounding high-pressure hilltops or plateaus: the deeper the depression, the steeper the slope of the hill; the steeper the slope, the faster the air moves and the more wind there is.

Due to the earth’s rotation, this flow of air from high to low pressure is not straight. The Coriolis effect curves the flow to the right, or counterclockwise, in the northern hemisphere and to the left in the southern hemisphere. In the northern hemisphere, air flows toward the center of a depression in the same way that water drains out of a sink, spinning in a counterclockwise direction as it works its way to the center. The deeper the depression, the more rapid the spin. The flow takes a different compass direction at each point on the spiral. To the north of a depression, the wind blows from the north-east; to the west, from the north-west; to the east, from the south-east; and to the south, from the south-west.

Depressions, unlike sinks, are usually in motion, being pushed from west to east by the prevailing westerlies created by the spin of the earth. A phenomenon of depressions is that when they move slowly they are relatively benign, but when they move rapidly they may be more dangerous than the differences of atmospheric pressure indicate. To put it another way, a fast-moving shallow depression may be more violent than a slow-moving deeper depression. Another phenomenon of depressions, especially the fast-moving ones, is that the winds on their lower half—the southern part of a depression moving east—may well be more violent than those on the upper half. In fact, sailors often speak of a storm’s “dangerous quadrant,” its lower righthand area. As people in New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island already knew, the winds in the lower half of this particular fast-moving depression were exceedingly violent.

Between midday Sunday (as Grimalkin sailed down the English Channel in the fog) and midday Monday (when the northeast wind filled in after the calm), the depression traveled eastnortheast at a speed of between twenty and forty knots, covering over eight hundred miles. To its south was the great Azores high, a mass of air with relatively high atmospheric pressures in the range of 1017 to 1034 millibars (30.0 to 30.5 inches). Air flowed down the slopes of this nearly stationary mid-Atlantic mound into the valleys of the low-pressure areas around it. The Coriolis effect of the spin of the earth redirected this air to the right, so that to the north of the Azores high a southwest wind was helping to push Low Y toward the north-east.

Conspiring with the high was a large depression of low-pressure air to the north that stretched almost one thousand miles from the latitude of Greenland to the latitude of northern Ireland. The depression had left the coast of Canada on Friday morning, the tenth, and had lumbered across the Labrador Banks, absorbing along the way two smaller depressions that had moved down from Greenland. On Sunday morning, August 12, the center of this depression was located about three hundred and fifty miles south-west of Reykjavik, Iceland. Called “Low X” on British weather maps (since it had been spotted earlier than the depression called Low Y), it had an atmospheric pressure of 990 millibars (29.2 inches) and perhaps a bit less in its center. The outer isobar of Low X, 1016 millibars (30.0 inches), stretched across the mid-Atlantic Ocean between the latitudes of fifty and sixty degrees north. The wind there also blew from the south-west.

Low Y had hitchhiked east on the westerlies of the Azores high and Low X. Born at the latitude of forty-five degrees, the depression had not moved south of forty-three nor north of forty-seven degrees during its quick trip across eastern America and the western Atlantic, and it would have made its European landfall in the Bay of Biscay if another factor had not appeared.

This factor was offered by Low X. Instead of continuing on its easterly course, Low X stopped moving. While it stalled for two days off the west coast of Iceland, Low Y overtook it and moved into the quadrant where southerlies and not westerlies blew. In the predawn hours of Monday, August 13, the dangerous little depression changed course and headed northeast, at first aimed west of Ireland on the well-worn path of many previous depressions. Once weather satellites had a look at it and computers could digest the limited amount of information that was radioed from a few ships in mid-Atlantic, the British forecasters realized at around noon on Monday that Low Y, swinging around Low X, would sweep across southern Ireland and the Western Approaches that night.

Unfortunately, the meteorological office came to this conclusion too late to provide a gale warning for the 1:55 P.M. BBC Radio 4 shipping bulletin, upon which almost all the Fastnet race sailors depended for their afternoon weather forecast. The forecasters did, however, issue for special broadcast a warning of an imminent force 8 gale for southern Ireland and the Fastnet area (“imminent” meaning within the next six hours) and for a force 8 gale expected soon at Lundy, the island at the mouth of the Bristol Channel and one hundred miles northeast of Land’s End (“expected soon” meaning from six to twelve hours after the forecast).

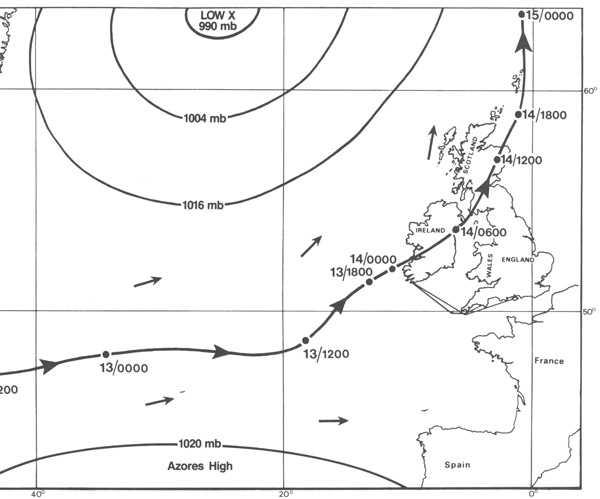

The path of Low Y from its start in Minnesota on August 10, until it died out north of Scotland on August 15. Low Y began to move north-eastwards toward Ireland only after it overtook Low X, which had stalled far to the north off Iceland. The westerlles created by Low X and by the Azores high (to the south) helped to push Low Y east at speeds as high as fifty knots. The arrows show wind direction. Times are Greenwich Mean Time.

Made even more violent by cold air sweeping down into it from Low X, the depression slowed down and deepened on Monday afternoon, and the 5:50 shipping bulletin reported that it was about two hundred and fifty miles west of Fastnet Rock with a barometric pressure of 998 millibars (29.5 inches). Again too late for the shipping bulletin, which would not come on the air again until 12:15 A.M., the meteorological office at 6:05 P.M. released a new warning of imminent force 8 increasing to force 9 gales in the Fastnet area. If they had continuously monitored BBC’s Radio 4 or if they had been within the limited range of and had been listening to one of four coastal radio stations using special frequencies, the sailors would have heard these gale warnings. But being human, they relied upon scheduled and predictable sources of information, and most of them had neither the time nor the inclination to monitor radios continuously. Furthermore, radios can be a drain on batteries that must also be used to provide power for navigation lights. (In the United States, many areas are covered by continuous marine weather forecasts, which are repeated every few minutes on special frequencies.)

At 8:50 P.M., the meteorological office issued revised gale warnings for mainland Ireland: the imminent force 9 winds would veer from south-west to west. The area that most concerned any racing sailors who heard the warnings was not mentioned again in new gale warnings until 10:45: “Fastnet: southwest severe gale force 9 increasing storm force 10 imminent.”

Satellite photographs on the following pages show the eastern North Atlantic at approximately 4:50 P.M. (British Summer Time) on Sunday, August 12 • Monday, August 13 • and Tuesday, August 14 • The Fastnet race course has been imposed. The photographs show Low X—the large swirl of clouds in the upper center—stalled off Iceland, and, to its south, Low Y approaching Great Britain and swinging across Scotland and over the North Sea. The second photograph was taken at about the time that weathermen realized that Low Y would sweep across the Fastnet fleet. U.S. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration

During its weather forecast that evening, BBC television showed a satellite picture of the Atlantic Ocean west of Ireland. The photograph was dominated by a clearly defined swirl of clouds curving north about three hundred miles south-west of Ireland. This was the front of the depression. Erroll Bruce, an experienced ocean-racing sailor who was sitting out this Fastnet race, took one look at the picture and telephoned his business partner Richard Creagh-Osborne to say, “They’re in for it.”

David Sheahan required neither a gale warning nor the satellite picture to come to the same conclusion. Between 9:00 and 10:00 P.M., the wind built rapidly while the barometer plummeted, and by 11:00 P.M. Grimalkin was sailing at six knots under her tiny storm jib alone. Even a reefed mainsail was too much sail for this force 8 wind. Soon water started to come on deck while heavy rain drove down continuous and cold. The crew sealed off the cabin by placing the wooden slats, called washboards, in the companionway hatch, and rather than go below—where equipment, food, clothing, and bedding were flying everywhere as the boat rocked and rolled—all six men sat in the cockpit, their safety harnesses firmly hooked to the jackwires that Sheahan had so carefully installed. Gerry Winks steered Grimalkin on port tack out into the blackness of the Western Approaches, holding a course about 20 degrees off the rhumb line of 330 degrees to Fastnet Rock—and (though they did not know it) almost directly into the path of the dangerous quadrant of the depression. On starboard tack, heading south instead of northwest, they would have been steering away from the storm but also from Fastnet Rock. Storm or no, this crew would continue toward their objective until the boat ceased making headway.

Gerry Winks tired quickly. At 3:00 A.M., exhausted and shivering, he went below, where dry clothes and some food took the edge off his hypothermia, the dangerous loss of body heat that comes from prolonged exposure to cold air or water. At the helm, Nick Ward thought that the high, steep waves and powerful wind were part of a scene from a surrealistic film. No sail was possible, and they were unable to stay on course under bare poles. David Sheahan wondered out loud what they should do to try to cope with the seas (“these blocks of flats but three times as wide,” Nick Ward called them). They eventually decided to run before it, effectively abandoning the race, with the wind and the waves on their stern, towing ropes overboard to try to keep their speed down. Yet even with six hundred feet of line dragging over the stern, Grimalkin was barely in control. She surfed wildly down the faces of the waves, like an elevator cut loose from its cable, and threatened to pitchpole, or somersault over her bow. She once accelerated to over twelve knots and, tilting forward until she was almost vertical, plunged down the face of a huge wave. Ward at the helm and Mike Doyle, sitting next to him, frantically looked to port and starboard for a flat spot to aim for, a landing field on which to level out, but all around was broiling white foam and ahead was a black wall—the back of the next wave rising out of the narrow trough. Grimalkin stuck her bow ten feet into the wall until her entire foredeck was buried three feet deep. The wall parted, and she shook off the tons of water and surfed off on another wave.

At least six times between 3:00 and 5:00 A.M. Grimalkin spun broadside to the faces of such waves and was caught under the curl and rolled until her mast was in the water. Each time, all six men were thrown out of the cockpit and left dangling by their safety harness tethers in the water or wrapped around the lifelines and backstay. A one-hundred-and-fifty-pound man generates a force of more than three thousand pounds when he is thrown twelve feet. The safety harnesses and jackwires withstood those loads, but the men themselves took a fearful beating.

On the fifth knockdown, Ward, who was still steering, was thrown entirely across the cockpit, over the lifelines, and into the water with his left leg tangled in the harness tether. As David and Matthew Sheahan dragged him aboard, Ward felt an unfamiliar sensation: his left leg hurt. He had not felt pain in that limb since the neurological attack eight years earlier. The leg, he decided, must have been broken when he hit the lifelines. He half sat, half lay in the cockpit while some of the men around him tensed themselves against the pounding waves and the driving wind simply to remain aboard a yacht that fell out from under them every time a wave passed.

David Sheahan slid open the companionway hatch and went below to radio for help. He reported their assumed position to Morningtown, the RORC’s escort yacht, and he hoped that she would send it on to the coastguards. He soon reported to the men in the cockpit that spotter airplanes and helicopters were on the way. Mike Doyle attempted to light flares but he was unfamiliar with the ignition procedure and they merely fizzled into the sea.

Sheahan came back on deck just in time to be slung into the lifelines when Grimalkin was knocked flat once again. When the weight of her keel rolled her back upright, he lay in the cockpit, his head badly cut. The crew helped him below, where his son, Matthew, sprayed antiseptic into the wound. Seeing that the cabin was almost totally wrecked—the radios, chart table, engine housing, and companionway ladder were destroyed—they returned to the cockpit, which, though exposed, seemed safer than the shattered interior. In their inflated life jackets and safety harnesses, the six men huddled together for warmth and protection. Nick Ward’s leg was causing him great pain, and Sheahan and Winks were dazed and frequently unconscious from their injuries and from hypothermia. Eventually, Winks was lowered to the cockpit sole where, at the others’ feet, he had some degree of refuge.

The next knockdown was the worst. Grimalkin was capsized, rolled right over by a giant breaker. David Sheahan was trapped under the cockpit as the boat lay upside down. To free him, his crew cut his safety harness tether, and when the boat finally righted herself after half a minute or more, he drifted away helplessly, never to be seen again.

Grimalkin was dismasted in the capsize and her broken mast and rigging and boom now cluttered her deck. The five survivors dragged themselves back through the lifelines and rigging into the cockpit, where Nick Ward collapsed. Gerry Winks rolled, unconscious, on top of him.

Matthew Sheahan, Mike Doyle, and Dave Wheeler talked over their situation and decided that Grimalkin was not safe. She was half full of water and wallowing dangerously, and in the gray morning light the seas seemed even more violent than they had before dawn. The skipper, Matthew’s father, had been swept away to a sure death before their eyes, and their shipmates lay unconscious at their feet. They pulled the rolled-up, uninflated life raft out from its storage locker under the cockpit sole, pulled the line that triggered the CO2 bottle, and watched the bundle of rubber raft inflate. A close look convinced them that if Winks and Ward were not dead, they soon would be, and that in either case they could never be dragged into the raft. Taking off their safety harnesses, they climbed gingerly into the life raft and pushed themselves away. The time was about 8:00 A.M.

The life raft turned out to be not much more reassuring than Grimalkin had been. Almost covered by the canopy, the three young men could barely see outside, and could only await help as they bailed out water thrown in by the waves. Yet rescue was only an hour in coming. A Sea King helicopter hovered overhead and dropped a wet-suited airman on a wire. As the airman in the water secured one man at a time in a harness, the winchman aloft let out slack in the wire and the pilot backed the helicopter downwind and rose well above the waves to stay away from the salt spray that might clog its turbines. When the airman in the water waved an “all ready,” the pilot, flying blind because he could not see the raft, moved the machine slowly forward under instructions from the winchman in the cabin. The pilot elevated and dropped his helicopter in tune with the steep waves monotonously rolling down at him from the horizon, all the while following the winchman’s instructions: “Six feet left, four forward . . . right over.” The winchman pushed a button and Grimalkin’s survivors were fished out of the sea, one by one.

With all three yachtsmen on board, the Sea King set off in search of another life raft. When two survivors of a yacht named Trophy had been lifted aboard, the helicopter swung east. A few minutes later, the five exhausted, cold men were in the sick bay of the Royal Naval Air Station at Culdrose.

Neither Grimalkin nor the half-dead men in her cockpit received any grace after being abandoned by the others. She was rolled over once again. Nick Ward regained consciousness to find himself under water, his arms and legs tangled in stays and lines, his head being banged by the hull. He struggled to the surface, untangled himself, and painfully crawled up into the boat through a gap left in the lifelines by the destruction of two stanchions. From the cockpit, he saw Gerry Winks dragging overboard. Wrapping Winks’s tether around a winch, he slowly winched his shipmate aboard. Winks was still alive. Using artificial respiration, Ward pumped water out of and breathed air into Winks’s lungs, but the combined effects of the cold, exhaustion, and his own physical disability were fatal. Winks whispered, “If you see Margaret again, tell her I love her,” and died.

Twenty-four-year-old Nick Ward was now alone with a dead man in a wrecked boat in a gale, without either a life raft or a functioning radio. His leg pained him and was possibly fractured and his back and shoulders ached from the beating that he had taken. His only course of action was to try to keep Grimalkin afloat and to hope for rescue. He staggered below, where everything was either shattered or afloat in the water. Even moving around in the cabin was dangerous, since the floorboards were floating, and loose food, broken crockery, and pieces of equipment continued to fly about as the boat rolled. David Sheahan had set aside four buckets for emergencies, but three had disappeared during the knockdowns and capsizes, leaving only the smallest for Ward to bail with. He established a schedule of one hour for bailing and thirty minutes off for rest in a wet and sometimes half-submerged bunk.

The bailing seemed to make no progress. He wondered if the transducer, the speedometer sensor projected through the hull, had fallen out. More likely, the gallons of water that had accumulated in shelves, drawers, sleeping bags, and clothing were now dripping down into the bilge.

Grimalkin, 8:00 P.M. Tuesday. Royal Navy

Airman Peter Harrison looks up at the helicopter from Grimalkin’s deck as Nick Ward waits to be lifted up. The well In the forward cockpit housed the life raft, which was Inflated some twelve hours earlier by the three men who abandoned the boat, leaving Ward and Gerry Winks. The large snaphooks In the bottom right-hand corner are at the ends of the tethers of two safety harnesses and are hooked to a jackwire running from the cockpit to the bow. The lifelines have been cut by the broken mast. Royal Navy

Whatever emotions he felt were focused on survival. His shock at Gerry Winks’s death and the horror of realizing that he had been left behind by his shipmates were, he decided, subordinated to the energy he needed to survive. His great frustration was that the three who had abandoned Grimalkin were not on board to help him save her and, when the storm had subsided, to sail her to port under an emergency rig. Except for the small transducer hole, the hull seemed sound enough, and, Ward thought, there was a way to step a jury mast once the wind and sea calmed. But he could never do it alone. He held no personal grudge against the three. Rather he was angry at them for giving up on the boat.

To gain better access to the bilge, he ripped out two bunks and tossed sails and equipment forward into a pile. Rummaging through the debris in the lockers, he found some milk. He could not, however, locate his medicine, which he was meant to take every four hours. The doctors had said that he could do without it for perhaps a day, but no longer. He had last taken the medicine Monday night, nearly twelve hours before.

As Ward tried to keep to his schedule, estimating time because his watch had stopped, the sky cleared to an almost cloudless cold blue. The wind had shifted into the north-west and was chilling. It continued to blow very hard until midafternoon. The waves, which more than the wind had caused the capsizes, lengthened out. They were just as high as the night before, if not higher, but they were much less steep. Where they had broken and fallen on Grimalkin with fearful regularity, they now rolled under her relatively harmlessly. Nick Ward bailed and napped, bailed and napped all afternoon.

Sometime around 6:00 P.M., he heard an airplane pass close overhead. By the time he had scrambled into the cockpit, the plane had disappeared. To avoid a recurrence of that disappointment, he remained in the cockpit, securing his weary, hurting body next to Gerry Winks’s corpse with his safety harness and the mainsheet.

Another yacht soon appeared out of the waves. Ward was able to attract her attention with blasts on a foghorn. Although they had no transmitter, her crew fired off several flares that attracted the attention of a third yacht, which radioed a request for assistance. As dusk began to fall over the Western Approaches, Nick Ward saw a helicopter come at him rapidly from the east. The helicopter swung up and hovered forty feet overhead, and a man dropped quickly from the door on its right side onto the dismasted Grimalkin’s deck. Weeping with relief, Ward helped the airman secure Wink’s body to the harness. After the corpse was hauled into the helicopter, the harness dropped down again. Talking barely coherently, Ward told the airman to wait. “I must get my clothes from below,” he said. But the airman told him it was too late, that Grimalkin was sinking. As they were hauled through the air to the helicopter, Nick Ward looked down at the now truly abandoned sloop and quietly thanked her for providing refuge. He also thought how sad it was that nobody had stayed behind to help him keep her afloat.