Kialoa, with a small jib set to windward, rolls down the face of a wave. Louis Kruk

THE FIRST to round Fastnet Rock was the largest yacht in the fleet, Kialoa, at 12:45 Monday afternoon. Sixteen hours later, as we in Toscana prepared to make the turn and head back to England, this American seventy-nine-foot sloop was approaching the Isles of Scilly. Her passage across the Western Approaches had been quick but eventful.

When the wind built late Monday night, whipping through forces 7, 8, 9, and 10 in two hours, Kialoa’s crew shortened sail as quickly as the enormous forces on her equipment would allow. By midnight, she was sailing under triple-reefed mainsail and number-3 jib, and two-thirds of her twenty-man crew were on deck in anticipation of further changes. Soon after, they lowered the number-3 jib and raised the number 4; later they changed to the forestaysail.

Kialoa reveled in these conditions. Her owner, a Los Angeles real estate executive named John Kilroy, had had her built for offshore racing. Since her launching in 1974, she had made two circumnavigations of the world in search of hard racing, winning the World Ocean Racing Championship along with dozens of races. A man who thoroughly enjoyed the power that his wealth had provided him, Kilroy—like many owners of large yachts—had made his vessel into an extension of his own personality. He had closely supervised the designers and builders he had commissioned to create her and had gone to great lengths to evaluate her performance with computers and other sophisticated electronic instruments.

Kilroy was proud of his knowledge of both his yacht and her equipment. Therefore, he was surprised when a block on the windward running backstay broke—a fitting that had been designed to take a load of twenty-four thousand pounds. With the backstay slack, her ninety-five-foot mast was inadequately supported between its top and the deck. As Kialoa pounded over the waves at speeds of well over ten knots, the middle of her mast swayed fore and aft through an arc of four feet. Knowing it was only a matter of moments before the spar would snap, Kilroy ordered the mainsail trimmed all the way. The pressure of the sail would provide some support until an emergency backstay could be rigged. The mast steadied and held.

Kilroy himself was not so fortunate. A gust that he estimated at seventy knots in strength knocked the big sloop over on her side and, he said later, “a wave that was solid green water at least six feet above the deck picked five guys up and threw them at me.” Kilroy was pinned against a winch. In considerable pain, he extracted himself from the heap of men and went below, where he stayed for much of the remainder of the race. First thought to be broken ribs, the injury was eventually diagnosed as a ruptured chest cartilage by a sports-medicine doctor, who told Kilroy that he now had something in common with American football quarterbacks who are tackled by burly defensemen.

Kilroy suffered one more embarrassment. Kialoa was caught and beaten to the finish at Plymouth by the seventy-seven-footer Condor of Bermuda, whose crew not only sailed closer to the Isles of Scilly than the more conservative Kilroy but also set a spinnaker when the wind dropped down to forty knots. Despite a broken spinnaker sheet block and several wild broaches when she was overpowered by gusts (at one stage, she spun through 180 degrees and started sailing backward at three knots), Condor kept on under the big sail at speeds as high as twenty-nine knots until she submarined her entire forward deck under a wave. The spinnaker was then lowered.

Condor beat Kialoa to Plymouth by twenty-eight minutes and broke the Fastnet race elapsed-time record by almost eight hours. Rob James, one of her crew members and a crew and skipper in two round-the-world races, said after the finish that the waves had been worse than any he had experienced around Cape Horn or in the southern oceans—two areas famous for dangerous seas.

In the 170 miles of water between Toscana and the two leading boats—all three of whose crews were able to keep racing—there were dozens of crews whose concerns were considerably more basic than that of sailing fast. Some were able to stay on course under storm sails. One of these was the crew of Imp, an American thirty-nine-footer, who were content to sail under deeply reefed mainsail alone for several hours, averaging a speed of about seven knots—fast enough to allow good steering, yet slow enough to stay in control. Her owner, Dave Allen, figured correctly that simply being able to finish the race would assure Imp a good position in the Fastnet and Admiral’s Cup placings (of the 303 starters, only 85 finished; 41 of the 54 Admiral’s Cup yachts that started finished the race). Fast enough in the early part of the race to have reached Fastnet Rock before the wind veered to the north-west, Imp, unlike Toscana and the vast majority of other boats, never had to try to beat into the gale. Likewise with Eclipse, an English thirty-nine-footer, which, under storm jib and double-reefed mainsail, was rolled over on her side by a wave when twelve miles from the Rock, at about 1:00 A.M. Tuesday. The crew lowered the mainsail for a while, and after some discussion, the third reef was tied in and the sail was rehoisted. Once around the Rock, the crew even considered hoisting the larger, number-4 jib, but the wind strengthened to the point where they lowered the mainsail once again and sailed under jib alone relatively comfortably at seven knots. Imp, which went for stretches under mainsail alone, finished seventh on handicap in the race; Eclipse, under a different sail for the same reason, finished second. Their elapsed times differed by only seven minutes.

Another, much larger, category included all the boats that were not fast enough to have reached the Rock before the wind shifted to the west. Many, unlike Toscana, were not sufficiently large and stable to carry sail while beating to windward in such a strong wind. Most of these boats were smaller than about forty feet (Imp and Eclipse were exceptionally fast for their thirty-nine-foot length), as were the majority of the boats in the fleet.

Windswept went through an ordeal that was in many ways typical of the experiences of many of these boats. Her crew was of average ability—some members widely experienced, others not much more than novices. She was handled conservatively. And she suffered two major and several minor misfortunes.

Owned by George Tinley, a very knowledgeable sailor from Lymington, Windswept was one of the boats in the new Offshore One-Design-34 Class designed by an American, Doug Peterson, and built by an Englishman, Jeremy Rogers, who also built and owned the successful Eclipse. Tinley’s crew consisted of six sailors, some old friends, others recent acquaintances. Many ocean-racing skippers prefer to take friends as crew members, not only to enjoy their companionship but also because the mutual understanding and respect of their relationship may allow for better teamwork. Others make a point of not inviting friends to crew so that personal loyalties will not intrude. Crewing for Tinley in Windswept were a small-boat-racing sailor with limited offshore experience; a man with whom the skipper had raced in small boats twenty-five years earlier (“A marvelous chap to be out with,” Tinley said of him); a young apprentice sailmaker who had sailed in Windswept in three offshore races in 1979; a young Frenchwoman with some offshore sailing experience; a knowledgeable navigator; and a sixteen-year-old boy who had sailed a great deal with his parents.

When conditions deteriorated on Monday evening, the crew quickly shortened sail until at 1:00 A. M. Windswept was sailing under storm jib alone, going fast and in control, although the mast shook violently when she was battered by the seas. As the wind continued to build, reaching sixty knots on Windswept’s anemometer, Tinley decided to lower the storm jib and let the boat lie a-hull, letting her lie with no speed on with her port side to the waves so she could bob up and down. This is an established technique for riding out storms. Two crew members kept a lookout in the cockpit, their safety harnesses securely snapped to a safety line, but they did not wear life jackets. Nobody was badly seasick, the motion was comfortable, and the deck was dry. At one stage the Frenchwoman told Tinley that the experience reminded her of sitting on a beach and watching the waves harmlessly come in. “We were just lying there like a little duck, going up and down,” Tinley said later, “which is just what all the books say should happen.”

The only problem was the cold. Sitting inactive in the cockpit, with the tiller lashed to leeward, the lookouts began to suffer. Sometime between 3:00 and 4:00 A.M., Tinley called for a change of watch, and he and the woman were replaced by two men who had been warming up below.

Soon after the watch change, with no warning, a huge wave rolled Windswept over and threw the lookouts out of the boat to the limit of their safety harness tethers. One, Alan Ford, was able to crawl back relatively easily as the boat righted herself. The other, Charles Warren, had considerable difficulty climbing up the high topsides and over the lifelines. Below, everybody was thrown onto a leeward berth. Tinley’s nose was broken, and through the dim glow of the single lamp that was lit—its globe was full of water, creating a weird effect—the others could see his blood mingling with gallons of water that had made its way into the cabin. Glass jars had broken and the interior was a mess.

Having seen that lying a-hull was not effective, Tinley decided to run out a drogue, or sea anchor, to try to keep Windswept’s bow pointed into the waves so she would not be rolled over sideways again—another traditional storm tactic. They tied lines and an anchor around a sail in its bag and threw the improvised drogue off the bow on the end of a large mooring line. The boat drifted faster than the drogue and eventually came up short against the line, which pulled the bow almost directly into the waves. The motion was considerably more comfortable, so all seven crew members retired to the relative warmth of the cabin. Every five minutes, somebody would look out the companionway hatch. A lookout soon spotted another boat gradually approaching through the waves. The navigator lit a white flare, and Tinley started the engine, put it in gear, and steered to port. The other boat drifted by, and Windswept, with the starboard side of her bow now to windward, felt even more comfortable.

Tinley lashed the tiller to port, the new leeward side, moved the uninflated life raft from its locker to the cockpit sole, where he lashed it down, and issued inflatable life jackets, one of which, though brand new, was already punctured.

Soon after, confused waves smashed the bow back across and, with the tiller now to windward, the boat’s bow continued to swing off until Windswept once again had the seas on her beam. Tinley started the engine and threw it into gear, only to feel the propeller grind to a halt as it was entangled by a line streaming overboard. There was not much that Tinley could do except relash the helm to leeward and return below.

Not long after, a wave lifted Windswept’s bow and smashed her completely upside down.

In the capsize, Tinley, already bloodied, suffered a broken wrist and was knocked unconscious. He had been sitting on sail bags on the cabin sole, eating a piece of chocolate. He has no recollection of where he ended up, but he knows that one of his shipmates was thrown from a bunk into the forward cabin, leaving footprints on the main cabin’s ceiling. Windswept remained upside down long enough for the rest of the crew to start worrying. “Never mind,” somebody shouted, “it will come up again in a minute!” For thirty seconds or more, the horrified crew sat or lay in pitch darkness, hearing water rush through the companionway hatch (one washboard had been left open to provide air below), through air vents in the deck, and through the cockpit seats. When she finally righted herself, the water was up to the level of the settee berths, at least two feet above the bilge.

The bilge pump handle had disappeared during the capsize, so two people began bailing out the cabin with buckets. On deck, other crew members found the life raft, still uninflated and dragging overboard at the end of the inflation line. Apparently planning to abandon the yacht, they hauled the raft back on board and tugged on the line until it broke at the CO2 bottle. Obviously, their only life raft would have to be Wind-swept herself, and she did not seem very fit for sea. As men below bailed water into the cockpit, loose tea bags and other debris clogged the cockpit drains until the cockpit itself filled and the water started to spill back into the cabin through the seat lockers. The engine was useless, the batteries were leaking a smelly acid, all the lights were out, and the skipper was lying unconscious in the cabin. Lying next to him, Charles Warren, who had suffered a broken nose and been stunned, assumed that the boat had split open and was sinking—he knew nothing of the capsize. When Tinley regained consciousness, he was in the cockpit, his safety harness hooked onto a line. Nobody knew how he had arrived there.

The boat rode relatively easy, yet the seven sailors were unanimous in thinking that they had to get off Windswept. “Lives being more important than boats,” Tinley later said, “we would be taken off.” But there was no getting off without the life raft and, without a radio transmitter, no way to call for help. The sailors attempted to inflate the raft with a small hand pump before giving up after six hours. They moved the drogue line aft to the transom to keep the stern square to the waves, and shot off red flares as the sky began to brighten. Soon, a mast appeared, and a sister ship named Mickey Mouse careened down the seas toward them. In those conditions, Mickey Mouse could offer little aid, although her crew did shoot off a flare to try to attract the attention of a trawler that passed a few hundred yards away. Windswept’s crew fired four red parachute flares, one of which did not function.

Alan Ford, the small-boat sailor who had the least amount of experience in offshore sailing, took the tiller and steered skillfully for the next four hours. Her speed limited by the drogue, Windswept was manageable and did not threaten to pitchpole, or somersault over her bow, while racing down the steep waves. The 360 feet of line, the sail bag, and the anchor were finally working. Tinley tied a six-gallon jerry can of fresh water to the line to increase the resistance. “We found that if she was carried off really fast on the face of a wave and the helmsman made a mistake, we were really done,” he said later. Although morale was low, the crew continued to try to improve the drogue, even hanging out loops of line to break waves before they reached the boat, an idea that they had read about in boating magazines and that they found was unsuccessful in practice.

The interior, though dry, was useless for sleeping. The lee cloths that had cocooned sleepers in the main cabin settees had broken, and the only useful bunks were the underdeck pilot berths, which nobody wanted to use for fear of being trapped if the boat capsized again. The crew huddled together on the cabin sole for warmth, and from time to time the Frenchwoman (“The good Sophie,” Tinley called her) blew warm air down their shirt fronts. All day Tuesday, Windswept’s cold, disheartened crew took turns steering and trying to rest in the cabin. They realized in late afternoon that the wind was dying and prepared to get under sail. Since they were uncertain of their position, Tinley worried about making a landfall on the unfamiliar coast of southern Ireland. At about 5:00 P.M., they attracted another racing boat by waving an SOS flag that they had prepared from a lee cloth to signal helicopters. The boat passed close by and her crew gave Tinley the compass course to Kinsale. It was dead into the wind, and Tinley decided that Windswept could reach with more comfort and speed to Cork. After using sheet winches to haul in the drogue, they set the storm jib and were under way. It was a slow, long sail until they had recovered enough from the shock of the storm to set the much larger number-2 jib at dawn on Wednesday for the last, increasingly pleasant, twenty-five miles into Crosshaven, the yachting harbor of Cork, Ireland.

“When men take up a dangerous sport some must expect to die,” a reader wrote to the English magazine Yachting World after the Fastnet race. Yet unlike mountaineers and race-car drivers, few of the people in Windswept’s crew or in the Fastnet fleet would have called their sport dangerous before the gale broke over them Monday night—frequently uncomfortable and sometimes harrowing, but rarely if ever a threat to life and limb.

Ocean racing’s record of fatalities was probably shorter than forty people in over one hundred years. From time to time, individuals had been lost off boats or had been fatally injured during races. The death of Colonel Hudson in the 1931 Fastnet race was such a fatality, and during the Southern Ocean Racing Conference series held off Florida in 1979, one man fell off the stern of a boat at night and drowned and another man died after a boom fractured his skull. During the first ocean race ever held, a transatlantic race between three one-hundred-foot schooners, in December 1866, a wave swept six men out of Fleetwing’s cockpit. This was the greatest loss of life from a racing crew until a French thirty-five-footer, Airel, went down without either a trace or an explanation during a short race off Marseilles in 1977, taking seven men with her. Forty-two years earlier, during a transatlantic race to Norway, an American named Robert Ames was washed off his ketch Hamrah at night during a gale. His son Richard dove overboard and swam to him, and another son, Henry, launched a rowboat to rescue them both. The rowboat capsized and the three men disappeared before Hamrah’s remaining three crew members could sail back to them. Frightful as they were, the Fleetwing, Airel, and Hamrah tragedies, totaling sixteen deaths, were so exceptional that most yachtsmen first hear about them as legendary examples not of the sea’s cruelty but of poor seamanship: nobody should race across the North Atlantic Ocean in December, or sail in a boat, that, like Airel, is not equipped with a life raft, or swim for a man who has fallen overboard.

Few people who go to sea for pleasure would disagree with a dogma propounded by Thomas Fleming Day, the founder of American ocean racing. “The danger of the sea for generations has been preached by the ignorant,” Day wrote some seventy years before the 1979 Fastnet race; “it has been the theme for the landsman poet and writer, until the mass of the people have accepted this gross libel of our Great Green Mother as gospel. . . . [A seaman] knows well enough that the sea never destroys purposely and malignantly. He knows that it never has or will murder a vessel; that every vessel that goes down commits suicide.”

Whether or not they got into major trouble, George Tinley and many other survivors of the Fastnet gale have good reason to be less trusting of the sea than was Day. Even small mishaps were threatening to life. On board Carina, the successor to the winner of the 1955 and 1957 races, a lurch sent a carving knife flying out of a galley drawer, across the main cabin, and, point first, into a door. When Aries’s life raft was thrown from its cockpit storage space, the inflation line tangled in the steering wheel, which, as it turned, triggered the CO2 canister. The crew watched helplessly as the raft filled the cockpit. When it threatened to jam against the wheel, they hacked the raft to pieces with knives and threw it below to be glued back together. The log of Mosika Alma read: “0600, FLIPPED UPSIDE DOWN to 180 degrees. No serious injuries. No structural or rigging damage. Skipper cracked ribs, mate smashed nose, one crew facial cuts.” As the Royal Navy yacht Bonaventure II went through a series of knockdowns just after dawn on Tuesday, her mast became progressively weaker and finally snapped during the third knockdown, hitting and breaking the left forearm of her skipper, Captain Graham Laslett, Royal Navy, and falling on top of three men who had been hurled overboard. Two of the men were quickly cut free and hauled themselves back aboard, but the third was so entangled in the mess of wire, rope, aluminum mast, and sails that his recovery from the water took well over an hour. Spotting a ship that appeared to be on a collision course with Bonaventure, Laslett fired off flares and ordered the life raft prepared for quick inflation. The ship altered course at the last moment and stopped; it turned out to be a Royal Navy fishery protection vessel, HMS Anglesey, which had been homed in on Bonaventure by a Nimrod patrol plane. Laslett decided to abandon ship. His crew inflated the life raft, climbed into it, and drifted downwind to where the Anglesey stood by.

These threatening accidents were almost trivial in comparison with the fifteen deaths that occurred on August 14. One fatality was Peter Dorey, who was steering his thirty-seven-footer, Cavale, when she was capsized at about 3:00 A.M. while running before the gale under bare poles. He and the other man on deck, Philip Bodman, were heaved overboard. Bodman’s safety harness took the strain, but Dorey’s did not and he was washed away. Dorey was fifty-one years old, a shipping executive, and the president of the States Advisory and Finance Committee of Guernsey, in the Channel Islands. Before the start of the Fastnet, he had twice put his boat and crew through man-overboard drills, but on that dark night he was out of sight of Cavale within moments. On board Cavale were one of his sons and a cousin.

Broken equipment also was responsible for the loss of two men from the Royal Naval Engineering College’s thirty-five-footer, Flashlight. The men, Russell Brown and Charles Stevenson, both Royal Navy officers, were lost when safety harnesses and a lifeline broke. When the Dutch-owned thirty-three-foot Fastnet entry Veronier II rolled while hove-to under storm jib, G. J. Williabey and another man were thrown from the cockpit. The rope tether of Williabey’s safety harness broke, and the other man, whose harness remained intact, suffered bruises to his body under the harness and to his hands and arms where he grabbed at objects. When the boat righted herself, the crew threw a man-overboard buoy with a strobe light into the water and returned to it. After searching for Williabey for twenty minutes, they decided that he was lost and that they were risking their own lives.

Festina Tertia, a British thirty-five-footer on charter, had abandoned the race early on Tuesday morning and was running back toward England under storm jib in excellent control. Her only problem was that the small cockpit drains could not dispose of water quickly enough as waves broke over her. With the cockpit full of water, the seat lockers were filling and draining into the bilge. At about 1:30 P.M., she was unexpectedly rolled 150 degrees by a cresting wave whose only advance warning was the roar of the breaker. One man was thrown so hard against the steering wheel that its supporting column broke. When Festina Tertia righted herself, another man, Roger Watts, was missing; his safety harness tether was still hooked to the boat and the harness, which apparently had snapped, was attached to the tether.

The crew immediately started man-overboard procedures, rounding up to Watts, who lay face down and unresponsive in the water. On the third pass, Sean Thrower stripped off his foulweather gear and outer clothing, dove in, and swam toward the man, but a wave separated them. “Can’t you see he’s dead!” somebody shouted, and Thrower swam back to the boat. The waves had been forceful enough to rip his underwear off. Suffering from hypothermia, he was hauled into the boat, dried off, and bundled into warm clothes and a sleeping bag. His shipmates realized that he was on the verge of shock, so they radioed a Mayday, and an hour and a half later, a helicopter arrived overhead. The crew inflated the life raft, and Thrower climbed into it and pushed away. The cable pulled him up into the helicopter, and fifteen minutes later he was in a warm bath in the Culdrose sick bay.

The death of a crew member in the thirty-two-foot Gunslinger came well after the boat was rolled over. Running before the gale under storm jib early on Tuesday morning, she handled the seas well until her rudder broke. Bob Lloyd, the skipper, opened the hatch and yelled below for help, and was lowering the jib when the boat broached, skidding off sideways down the face of a wave. The succeeding wave rolled her over on her side. Lloyd was thrown overboard, to the end of his tether, and the other crew members came on the deck of the now-righted boat. The next wave rolled the boat over on her side once again, and was followed by a wave as high as forty feet, which curled high above Gunslinger, broke, and drove her all the way over. She was upside down.

Water poured through the open hatch, and when the boat finally righted herself, the cabin was flooded to the level of the lower bunks—about knee height—and seemed to be taking on more water. The crew assumed that she was leaking badly through a hole left by the broken rudder. When the water reached waist height, they decided to abandon ship. Gunslinger was now more than half filled. One crew member radioed a Mayday; the others inflated the life raft. The raft was pushed overboard, and Paul Baldwin got into it with a flashlight and other equipment as the others prepared to follow.

A breaking wave then swept over the boat and capsized the raft, throwing Baldwin out. The other men watched as he struggled to swim back to the raft, in his life jacket. The bow line of the raft tightened and broke, injuring the hand of the crew member holding it. When his shipmates last saw Paul Baldwin, the raft was drifting away from him.

Gunslinger now had to be made seaworthy. The crew bailed frantically, and after a couple of hours the water level in the cabin had dropped. She was not leaking, the crew decided; the added water had poured into the bilge from the lockers, shelves, and head liner. Able to get out a distress call, they attracted a helicopter, which picked an injured crew member, Mike Flowers, out of the water at about 5:00 P.M. The others endured the cold and rolling until 8:30 Wednesday morning, when a Dutch trawler, the Alidia, took Gunslinger under tow to Crosshaven, where she suffered some damage when she drifted onto a trawler. Aside from the broken rudder, that was the only serious damage that Gunslinger suffered during her long ordeal.

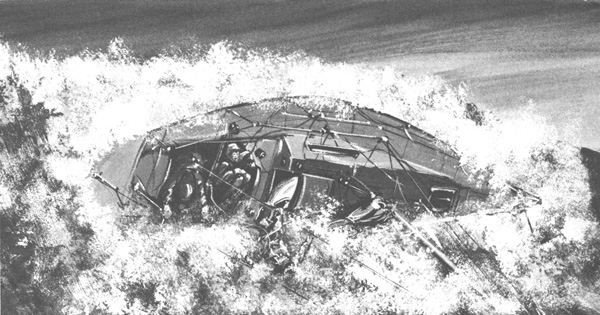

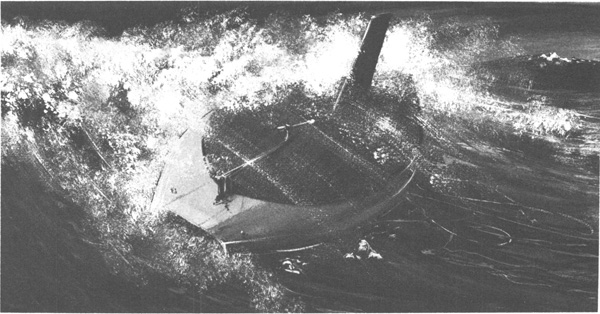

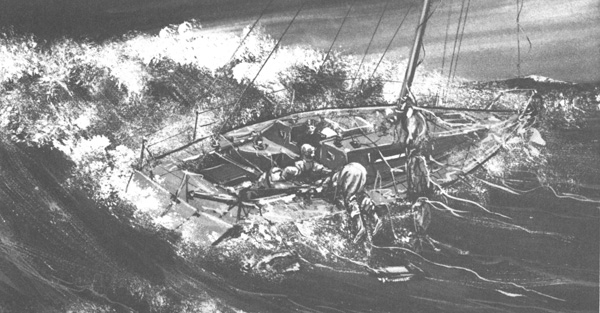

How a boat can be capsized. First, she broaches to one side while surfing down the face of the large wave. The next wave then breaks over her with thousands of pounds of water flying at speeds over thirty knots. As the breaker collapses over her, the boat is lifted over on the face of the wave, until she is rolled upside down with her mast in the water, throwing men out of the cockpit and, sometimes, breaking the mast. Here, Gunslinger, the stump of her broken rudder showing, remains capsized until a wave pushes against the keel, which rights her.

Of all the stories of boats and crews distressed during the Fastnet gale, few are more terrifying than that of Trophy.

An Oyster thirty-seven-footer designed by the British firm of Holman and Pye, Trophy was owned by Alan Bartlett, a North London pub owner who had sailed for over twenty years and who, in Trophy and previous boats, had raced in an earlier Fastnet and in several other RORC events. A genial man who cared strongly about his boat and crew, Bartlett had a steady crew of seven men, all of whom had sailed together before the 1979 Fastnet race. During 1978, Trophy’s first year, the crew had been worried by apparent structural weaknesses in the boat, and Bartlett had arranged for a boatyard to reinforce the hull—a complicated and expensive procedure that involved the removal of the entire cabin. When Trophy was reassembled in the spring of 1979, the crew installed a few special items, among them a custom-built navigator’s seat in which they stored flares and other safety equipment. Every weekend, the eight men worked on the boat at Burnham-on-Crouch, about forty miles east of London.

Once the racing season opened, the crew experienced the mix of mediocre and prize-winning performances that is the lot of most ocean-racing boats, winning their class in the ninety-mile race from Harwich to Ostend, Belgium, but doing poorly in the rough conditions of Cowes Week. Like most crews, they spent the day before the Fastnet race start storing food and clothing and checking safety equipment and racing gear. The Beaufort life raft had been inspected a month or so earlier, and now a crew member carefully examined its storage locker under a seat in the cockpit. To his surprise, he discovered that somebody had screwed down the top of the locker. In the highly unlikely event that they would abandon ship, the crew would have to locate and then use a screwdriver simply to get at the life raft. The man replaced the screws with cotter pins, or split pins, which could easily be pulled out of holes in the locker.

The first two days of the race were slow, the only excitement coming when a tug towing part of an oil rig loomed out of the fog on Sunday and passed close by. When the wind built after Monday morning’s flat calm, they were off Land’s End, and soon they were flying toward Fastnet Rock under spinnaker. The 12:15 weather forecast of force 6 to 8 did not disturb either Bartlett or his crew, most of whom had been through bad weather in Trophy or her predecessors. In fact, it was the rough return from the last race of the 1978 season that had convinced Bartlett that the hull required reinforcement, because as they had sailed across the English Channel under small jib alone, they had felt the hull twisting under them.

By Monday evening, the conditions were difficult enough to warrant something unusual on one of Alan Bartlett’s boats, a cold dinner, since the cook could not keep his footing in front of the stove. They shortened sail to keep up with the increasing wind, and by 10:30 Trophy was reaching at ten knots under number-3 jib alone. Seasickness was insidiously taking its toll of the crew, and sleep was difficult. As in many racing yachts, there were not enough bunks for the entire off-watch, so one or two men slept on the sails packed on the sole of the main cabin. Those on deck were hooked onto the lifelines and stanchions with their safety harness, and life jackets were issued.

At about 11:00 the crew on deck spotted a red flare drifting down out of the clouds. Immediately deciding to go to the assistance of the distressed vessel, Bartlett took a compass bearing on the spot from which the flare appeared to have been fired and turned on the engine. He shouted below for somebody to enter the time and position in the logbook. After the finish, he said, he would present the logbook as evidence when asking the race officials for redress for time spent in his rescue efforts. Trophy’s forty-horsepower diesel drove her well across the waves, beam-to, yet it was still over an hour before she was alongside a dismasted white sloop, whose crew told Bartlett through a series of gestures that all was well, after all. With Simon Fleming at the steering wheel, Trophy stayed on station making a bare one knot under power alone.

Also standing by was Morningtown, a thirty-nine-foot cruising ketch owned by Rodney Hill and serving as the Royal Ocean Racing Club’s official race escort vessel. Her assigned job was to monitor radio channels and to take position reports from the Admiral’s Cup yachts. In her crew was Pat Wells, who might have been competing in the race except that his own boat had run aground on the Dutch shore during the North Sea Race in May and had been filled and destroyed by breakers.

Morningtown rolled badly in the confused, wild sea, and her crew found it hard to hold her on station, since she made considerable leeway, slipping sideways downwind at over three knots. Peering through the spray-filled gloom, they saw Trophy standing by the dismasted sloop, whose crew appeared to be preparing to abandon her in a life raft that they had hauled onto the foredeck. Another flare appeared from a different direction, so Morningtown’s crew, believing that the disabled boat was being properly shepherded, headed away.

Not long after, Morningtown’s steering cable slipped off the rudder quadrant and she lay uncomfortably rolling, her beam to the seas, while her crew tried to repair the damage. Looking up, somebody saw a dismasted yacht pass by, and a life raft in the water. To their considerable surprise, the RORC representatives realized that the disabled vessel was Trophy, and that she had been abandoned by her crew, who only minutes before had seemed to be in full control.

They had been in full control until they slowed down near the first disabled yacht. Only moments after the other crew signaled assurances, Trophy, lying almost motionless, was deluged by a huge breaking wave, the force of which spun the steering wheel out of Simon Fleming’s hands and whipped the boat around like a wind vane in a gust. When Fleming was able to get his hands back on the wheel, he could not budge it. The rudder, he guessed, had bent and was now jammed at a thirty-degree angle against the boat’s bottom. Having decided that there was little they could do, Trophy’s crew set to riding out the storm. Three men stood watch in the cockpit and the others went below to try to get some rest. Two of the three washboards were inserted in the companionway behind them to seal the cabin off from the spray and occasional solid water that came on deck. The small opening left by the absent board allowed fresh air in. Simon Fleming lay down on the sail bags and the others crawled into bunks. From his position deep in the hull, Fleming felt the boat to be safe. But very soon after, a wave that the men on deck said roared up as high as the fifty-foot mast broke on Trophy, rolling her right over.

Fleming found himself lying on the yacht’s overhead, under hundreds of pounds of sails. Robin Bowyer was shouting for help, the fluorescent lights dimmed, and the engine stopped. Fleming fought himself out from under the sails just as the boat righted herself and he was buried once again on the cabin sole under the sails, at least two feet of water, and a heap of equipment that had spilled out of lockers and the navigator’s seat. The water had poured through the small hole in the companionway where the extra washboard should have been, and when one of the men on deck pulled out another washboard to look below, more water came down.

On deck, the primary worry had been to avoid colliding with the drifting Morningtown, whose crew was out of sight, but when the great wave hit and rolled Trophy over, breaking her rigging and wrapping the mast under and around her bow, the escort boat was forgotten. As Trophy went over, Russell Smith was trapped in the water under the cockpit, and Richard Mann and Alan Bartlett were thrown clear. Smith and Mann pulled themselves aboard as the boat righted herself, but Bartlett was left dragging overboard by his tether.

Once he had dug himself out from under the sails, Fleming crawled up the companionway and into the cockpit. Without the weight of the mast aloft, the boat rolled much more quickly now, and the boom, sails, lines, and heaps of other gear that littered her deck swung back and forth across the cockpit, creating hazards for the dazed, confused men trying to keep their footing. Fleming saw Bartlett in the water on the windward side, his life jacket and safety harness entwined in sheets and halyards as he fought to keep his head above water. Fleming tried to haul Bartlett aboard, but the stocky skipper was made heavier by his water-soaked clothes and by the entangling lines. Fleming was, however, able to pull Bartlett alongside and, with Derek Morland, succeeded in hauling his skipper’s feet up over the toe rail. Lying in the water with his heels over the rail and his body being hammered against the topsides by the waves, Bartlett thought to himself, “What a silly way to die.”

Struggling desperately for a way to get Bartlett aboard, Fleming finally decided to cut him free. He found a knife and hacked away at the lines, slashing the safety harness and life jacket as well, until after ten minutes Bartlett was hauled on deck, exhausted.

Meanwhile, with their skipper over the side and for all intents and purposes out of commission, two other members of the crew took it upon themselves to decide to abandon ship—possibly these men were John Puxley and Peter Everson, who had suffered greatly from seasickness. When Fleming and Morland finally had Bartlett on board, they turned around and saw the inflated life raft in the water to leeward with the two men either in it or climbing into it.

Once inflated, the raft would either have to be cut loose or used. Keeping it on deck or alongside in a sixty-knot wind and thirty-foot seas was an impossibility. Given the situation, Bartlett and his crew had little choice: Trophy was dismasted and rolling violently; water was up to her bunks; the blackness of the night was broken only by the white crests of the great breaking waves; rescue was at hand with Morningtown nearby and—especially—with the recently inspected, inflated life raft alongside. Alan Bartlett decided to put his faith in the raft.

One by one, the men carefully climbed down into the raft, entering the canopy through the small observation port or through the flap that served as a door. One man brought along a galley knife, and when all eight were aboard, he cut the bowline. The men cautiously passed the knife from hand to hand, keeping the sharp blade away from the two inflated rings until it was dropped overboard. The raft and Trophy quickly separated.

Almost immediately, the men again saw Morningtown. The crippled ketch drifted down on the life raft from windward. Standing on the foredeck of the thirty-nine-footer, Pat Wells was ready to help them come aboard, but the ginger-bearded Simon Fleming stuck his head out of the canopy door and shouted that they wanted to stay in the raft. Wells was not surprised. Morningtown was rolling wildly as she drifted out of control, and the raft seemed to be relatively secure. Having been in a life raft earlier in the year after his own boat had foundered, Wells knew that crew transfers could be risky. His and everybody else’s main worry was whether Morningtown would run the raft over, but the two boats passed almost within two arms’ length, and were soon far apart. The time was about 2:30 A.M.

Before Morningtown was out of sight, Trophy’s crew had reason to suspect that they had made the wrong decision. Although they felt safe and secure—especially when they saw Morningtown go through a series of frightening rail-to-rail rolls—they had trouble getting settled in the raft. They could neither find handholds to which they could clip their safety harnesses, nor locate the drogue, which when thrown overboard would slow the raft as it surfed down the waves. As they settled themselves, the raft went up a particularly steep wave, an edge of the bottom was exposed to the wind, and the raft was flipped over onto its top, spilling four men out into the water. Almost immediately, the raft was blown back upright and the men clambered back aboard. The raft capsized several times more within the next few minutes.

On the fifth capsize, incredibly, the life raft split apart, the two inflated rings detaching from each other. Morningtown’s running lights were still within sight, but the ketch was far beyond reach in the black gale. Alan Bartlett was thrown the farthest, and he swam five yards back to the upper ring. The only man without a safety harness and life jacket—which had been destroyed when he was pulled out of the water—Bartlett was tiring.

Simon Fleming yells to Pat Wells, on Morningtown’s forward deck, that Trophy’s crew wishes to remain aboard the life raft.

Moments later, a wave swept away John Puxley and Peter Everson, and they could not get back. The six men remaining with the two parts of the raft frantically tried to paddle toward the two men, but they disappeared into a wave trough and were not seen alive again. Puxley, a father of two, was a forty-two-year-old crane operator from Burnham-on-Crouch. Everson, a bachelor in his thirties, worked for an automobile agency in Billercay, about fifteen miles east of London.

Up to this point, the men had not secured themselves to the raft, but now those with harnesses clipped the tethers to the rope handholds on the outside of the top ring. The men sat in the bottom ring, which had a floor, and towed the top ring alongside with their tethers. Somebody found the sea anchor, which was so tightly wound in its line that it had not opened automatically. When they let it loose, the line twisted around Russell Smith’s hand, tangled in his safety harness, and almost pulled him away. When it was finally straightened out, the drogue slowed the raft and steadied its motion, but the line broke after but a few minutes, and the small flotilla of inflated rubber rings and people was soon being rolled over, time after time. After each capsize the six men bobbed back to the water surface in time to catch the ring with the floor before it blew away.

Soon after first light, at about 5:30, a Nimrod spotter airplane flew over their heads and dropped a yellow smoke flare. Just then, they spotted a yacht on the crest of a wave and they fired off one of the flares they had found in the life raft. To their dismay, three more flares shot up almost immediately; they were not the only crew in difficulty, and although they kept reassuring themselves that Morningtown was bound to report their position, the six men began to be discouraged. Yet by experimenting, they discovered that if they lunged forward as the raft reached the top of a wave, they would force the raft through the breaking crest rather than over it, and the chances of further capsizing were much decreased.

The Dutch destroyer Overijssel nears the ruined life raft of Trophy In heavy seas. Peter Webster

Trophy’s life raft—what was left of it—alongside the Overijssel. Peter Webster

Sometime after sunrise, perhaps as late as 9:00 a.m., a large wave swept over the men and separated the rings. Fleming, who had unhooked his safety harness, came to the surface to find himself alone next to the bottom ring. The other men were yards away, secured to the upper ring. They tried unsuccessfully to paddle toward each other, and one man even attempted to swim the other ring toward Fleming, but they drifted apart.

Alone in the ring, Fleming considered a variety of possibilities. Should he take off his foul-weather jacket and trousers to use as sails? Should he stand up, sit down, or get back in the water? Tired and suffering from leg cramps, he finally decided to sit in the raft and to try to enjoy the warmth of the sun shining through the cold spray on this crisp, almost cloudless, gale-torn morning. Still in his clothes of the night before (he had not even kicked off the sea boots, which restricted his mobility but warmed his feet), Fleming tightened the hood of his foulweather jacket around his ears, and reflected on his impending death. Though tired and numb with cold, he was angry at himself. He knew death was coming, and he did not worry about it, but he swore at himself for accepting it, for giving in. It seemed so bloody stupid, he thought, to be dying so slowly and with so little pain, slipping slowly away in this cold sea. Although he felt lucky that he hadn’t been injured—an injured man might have lived half an hour, and he had survived for six or seven hours—the whole thing seemed absurd to him.

If Simon Fleming could worry about his own attitude toward death, he still had an Englishman’s sensitivity to the comfort of his friends. They were floating around in the upper ring, no more secure than they would have been in a large inner tube. At least, he thought, he could rest his feet. He worried for them.

Fleming didn’t know it then, but one of those shipmates gave in to the inevitable at about the time these thoughts were running through his head. Robin Bowyer, a forty-four-year-old sailing instructor, weakened swiftly and died. Alan Bartlett told the others that he would be the next to go. Although physically strong, and a sailor and amateur boxer, Bartlett was fifty-three years old, and his experience had been the worst of any that night among Trophy’s crew. After his ordeal at the end of his tether before the boat was abandoned, he had been in the water without a life jacket for hours.

And then came rescue. When Simon Fleming first saw a helicopter, he swore: it seemed to be flying away from him. But it swung back overhead and dropped a man with a sling down to him on a cable, and soon he was in the cabin. A few minutes later, the helicopter hovered over the other ring and picked up Alan Bartlett. The others would soon be recovered by the Dutch destroyer Overijessel, which was standing by a few hundred yards away, her crew aghast at the sight of the broken life raft. When Bartlett was hauled into the helicopter’s cabin, he was unable to move; he had been in the water for eight hours. The same helicopter, Sea King-597, had also picked up three survivors from Grimalkin from their life raft. Bartlett recovered quickly, and the five men were able to walk off the helicopter when it reached Culdrose. The pilot told Simon Fleming that, having seen the remains of their life raft, he was surprised that any of Trophy’s eight men had survived.