Tenacious rolls to leeward as she runs under shortened sail on Tuesday morning. Greg Shires

BY DAWN, any anemometers still functioning indicated wind speeds that averaged in the high fifties. Since most of these instruments read no higher than sixty knots, the sailors could only estimate the power of the gusts that pegged the pointers to their limits. Highly experienced men said later that the wind peaked in the seventies—force 12, or hurricane strength. It was a wind that blew down walls and trees all over Britain, killing several people; that swept a radio antenna off Toscana’s masthead; that made breathing difficult; that numbed faces. Its full blast, wrote Major J.K.C. Maclean, of the army yacht Fluter, created “a shriek of wind that I have only heard before when putting out from the shelter of a boulder on a Scottish hilltop.”

But the worst that the wind did was to be the primary cause of a huge, vicious, boat-flipping, morale-shattering seaway. The helicopter pilots, who, while hovering, had to dodge them, said the waves were as high as fifty feet. If that estimate were true, it still misses the point, for the danger of the waves lay not in their height but in their shape. “At daybreak the seas were spectacular,” remembered Peter Bruce, a commander in the Royal Navy who was navigator in Eclipse. “They had become very large, very steep, and broke awkwardly, but the boat was handling well.” George Tinley, who had been so badly beaten around in his Windswept, later said, “There were seas coming at one angle with breakers on them, but there were seas coming at another angle also with breakers, and then there were the most fearsome things where the two met in the middle.” After the gale, Major Maclean vividly described the appearance of the waves at night: “All around were white horses with their spray flurrying horizontally and slashing against us with the added impetus of the occasional rain squalls. But these white horses were just the top of some monster waves which hunched up, their tops flaring with spume, and marched on leaving us high at one minute so we could glimpse around, and then bringing us some fifty feet down into their troughs so we could appreciate the enormity of the next wave following. Some waves had boiling foam all over them where they were moving through the break of a previous wave, or, when the foam had fizzled away, they were deep green from the disturbance of the water. Otherwise the sea was black.”

The seas and not the wind gusts were capsizing boats and life rafts and smashing sailors overboard. The wind’s strength was such that smaller boats could not carry enough sail to steer around waves or to mitigate their great shocks; yet the seas were the true killers on August 14. Salt water weighs sixty-four pounds per cubic foot, and a moderately large breaker that is six feet high, ten feet across, and six feet thick carries, at a speed as high as thirty knots, twenty-three thousand pounds of water. The average boat in the Fastnet race weighed considerably less than that. When a wave of such size and velocity breaks over a boat like a breaker on an Hawaiian beach, its force overwhelms the stability provided by the hull’s shape and the keel. The unlucky vessel rolls perhaps through ninety degrees, perhaps all the way.

These waves battered even large yachts. The seventy-nine-foot Kialoa was knocked over by one, and, according to her designer and skipper, German Frers, Jr., Acadia, a fifty-one-foot American boat under charter to an Argentinian crew, was twice rolled over so far that her leeward spreaders dipped in the water. The American Admiral’s Cupper Williwaw, forty-five feet in length, was knocked down while Malin Burnham was climbing up the companionway ladder. His feet were swept out from under him with such force that a toenail was sliced off when it hit the underside of the cabin roof. The forty-six-footer Jan Pott, a member of the German Admiral’s Cup team, was dismasted when she was rolled completely over through 360 degrees. In the thirty-four-foot Innovation, a gold crown was shaken off a crew member’s tooth, and the owner, Peter Johnson, suffered a broken rib when he was heaved against a bulkhead during one of three bad knockdowns.

The best-known skipper in the Fastnet race, former British prime minister Edward Heath, did not escape problems either. His forty-four-foot Morning Cloud, a member of the British Admiral’s Cup team, rounded the Rock at 1:30 A.M. About two and a half hours later, a wave so black that nobody saw it coming out of the night smashed down from overhead and rolled her 130 degrees. The helmsman, Larry Marks, was banged first against the steering wheel and then against a stanchion, bending both. Two men were heaved so far that they ended up under the hull, on the ends of the tethers of their safety harnesses. After all were pulled back on deck, Heath decided to take in the deeply reefed mainsail and lie a-hull. Morning Cloud eventually got sailing again, but, undoubtedly discouraged by this latest bit of misfortune, after the loss of her rudder in the Channel race and vandalism to the hull during Cowes Week, Heath took it easy. “When daylight came,” Marks said later, “we thought, ‘Blimey, this is pretty bad.’ We were still pretty much dazed, and we all thought that the best thing to do was to sail home and sit by a fireside.”

This was not the first bad storm to have hit the British coast, whose reputation for rough weather was both deserved and ancient well before gales helped to destroy the Spanish Armada in 1588, but it was unusual in season and duration. In her book British Weather Disasters, Ingrid Holford describes thirty-nine natural catastrophes that have devastated Britain since 1638; only seven of them occurred during July or August. The eleventh edition of The West Coasts of England and Wales Pilot, a handbook for seamen using the Western Approaches and the Bristol and St. George’s channels, reports that there are force 8 and stronger gales 10 to 20 percent of the time in January and only 2 to 5 percent of the time in July. Eighty percent of all gales in the area blow between October and March and only 20 percent blow during the other six months. The average duration of gales, according to the Pilot, is four to six hours in winter and less in summer (the Fastnet gale blew for twenty hours). The Royal Navy hydrographers who wrote this edition of the Pilot refused to generalize, but their predecessors summarized the weather neatly in the tenth edition: “The region is very stormy.”

It always has been so. Richard Earl of Cornwall, a brother of King Henry II, built Hailes Abbey in Gloucestershire as thanks to God after surviving a storm off the Isles of Scilly in 1242. In The Isles of Scilly, Crispin Gill writes of how Scilly Islanders lived off ships wrecked on their rocks in winter and summer gales. (According to the etymologist Eric Partridge, “gale” is related to “yell” through the Old Norse word gala—“to sing”—and the Danish word gal—“furious.” Anybody who has stood on a Scilly hilltop during a gale knows that, like a Scottish hilltop, it endures an especially furious shriek of a song.) In his account “The Cruise of the Tomtit,” the Victorian novelist Wilkie Collins quotes a letter from a friend whom he invited on a September cruise down the north coast of Cornwall to the Scillies but who declined because the cruise was too near the autumnal equinox, a good time for a gale. “You may meet with a gale that will blow you out of the water,” the friend warns. “You are running a risk, in my opinion, of the most senseless kind.” Another friend writes, “If I were only a single man, there is nothing I should like better than to join you. But I have a wife and family, and I can’t reconcile it to my conscience to risk being drowned.” And a third friend advises, “Don’t come back bottom upwards.”

In late July 1936, a force 10 gale hit the small fleet of boats approaching Britain in a transatlantic race from Bermuda to Cuxhaven, Germany. Ben Ames, an American who sailed in the race in a German yacht, Hamburg, described the gale in an article in the October 1936 issue of Yachting:

Only when we were three hundred miles south-west of the Fastnet, scudding before another heavy blow, did we get a peep out of [the radio]: “A depression south-west of Ireland is moving rapidly toward the east. . . .” So were we.

It was this depression that dropped the barometer steadily at the rate of one millimeter [1.3 millibars] per hour for fifteen hours while the wind increased and the weather changed to the leaden dull gray of the Irish coast. By morning the seas had made up and, under a lowering sky, we ran before an angry sea, long cresting greybacks, a regular Fastnet sea. Under close reefed mainsail and storm jib, we raced before combers whose trough was as deep as our ship was long. Lifted high on the back of a wave which rose mountain high behind us, we careened dizzily down its face in a fury of foam at the speed of a surfboard. As the wave overtook us, we were brought up sharply, and the water roared under our counter, leaving us wallowing sickeningly as the bow settled, burying the length of the ship in the next wave ahead. At this moment the ship, seemingly with no headway, felt as though she had given up struggling and might be dragged down by the forces opposing her. Then, recovering, she would shake the load of water from her decks and race before the next greyback.

It was anxious work at the tiller. Twice, curling breakers crashed over the stern, filling the decks and flooding the cockpit. But we were expecting them and were securely lashed in the cockpit. They did no harm except to fill a sea boot and once catch the companionway hatch partly open and send half a ton of water below.

The sun came out for a time to light up the wind-swept seascape. A vicious wind whipped the tops off the breaking waves in a thin cutting spray that stung like hail. We were making eight and a half to nine knots before it when the slides at the top of the mainsail started to go—the marlin seizing began to part. We lowered the mainsail to repair the slides, but soon found it unwise to attempt to reset it. The wind was probably up to force 10 and, under one hundred square feet of storm jib, we ran before it, making five knots. We tried our favorite raffee [a small squaresail], but the ship rolled her decks under and we took it in again. When the wind eased a bit, we set the staysail and drove on toward our landfall.

At dusk, on the twentieth day, we climbed the rigging and found three low black humps on the horizon to the north slightly more solid than the heaving sea around them. They were islands—the Scillies. As night fell, the flashing lights showed Bishop Rock astern and the Wolf [Rock] abeam. We were in the Channel.

Written in the classic narrative style of sea stories, Ames’s account is of a boat heavier and slower than most of the yachts hit by the worst of the 1979 gale. Though Hamburg had her problems, neither she nor her crew was hurt. The seas the author described (and photographed for the article) were large and broke from time to time, but they do not seem to have been as inherently vicious as the waves that battered much of the Fastnet fleet. Hamburg’s waves were the seas that offshore sailors believe they can cope with. What most of the Fastnet sailors encountered were the nasty, curling breakers usually associated with a rocky lee shore or with the early-nineteenth-century sea battle paintings of J.M.W. Turner and Philip James de Loutherbourg, in which jawlike waves break through the cannon smoke to devour helpless sailors clinging to shattered spars.

In mid-August 1970, a depression took a path similar to the one taken by the 1979 cell, swinging over Ireland during the early hours on Sunday, August 16. It poured several inches of rain on England, causing severe flooding. Although the Fastnet race was not being sailed (it is a bienniel race sailed in odd-numbered years) several ocean races were under way. A fleet of boats between twenty and thirty feet in length was racing around the Isle of Wight, and six of the twenty-one starters withdrew when the gale quickly built. Only one boat required assistance—her rudder broke. The London Times boating correspondent, John Nicholls, described the race as “one of those events that will be talked about long after the rest of the season is forgotten.” Meanwhile, several boats were missing in the Western Approaches. One, a Royal Navy yacht named Temeraire, became the focus of a search that included a helicopter, two frigates, a German ship, and two minesweepers. Twelve hours after she was reported missing, Temeraire was located and towed to port by the Penlee, Cornwall, lifeboat. One of her crew, Sublieutenant Tony Higham, was quoted by the Times as saying that “the seas were reaching the top of the mast—about thirty-five feet—certainly enough to overpower a small yacht.”

While those descriptions confirm the belief that fierce storms are no novelty, they do not prove that bad weather always precisely repeats itself. This is so even in the same storm. An extraordinary aspect of the 1979 Fastnet gale is that while many survivors agreed to a considerable extent about the wind and sea conditions, some have entirely different accounts of what happened between early Tuesday morning and late Tuesday night. One is tempted to explain these differences with the Rashomon Premise, which is inspired by the Japanese film in which several different witnesses give varying accounts of a crime, each dependent upon the social and psychological perspective of the narrator. In this case, however, we are dealing with observable data that share a constant standard: the ease with which a boat was steered under a given spread of sail. By applying this standard and evaluating these stories, we may be able to judge whether or not the conditions were the same everywhere on the course in the Western Approaches.

Looking astern from Hamburg during the 1936 transatlantic race In conditions that the photographer described as “a regular Fastnet sea.”

Taken forty-three years apart, these photographs show the waters of the Western Approaches In strong gale conditions.

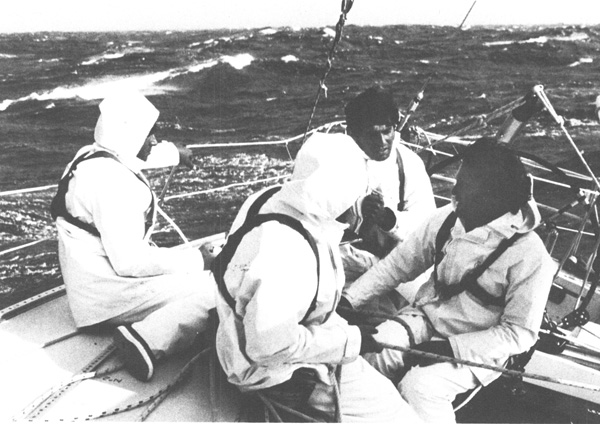

Having surfed down one wave, and having caught Its crest at the back of their necks, Eric Swenson at the wheel of Toscana, with Stuart Woods (left) and Dale Cheek (right), prepare for the next sea beginning to rise behind them. Sherry Jagerson took this picture while clinging to the mast.

The author at the helm of Toscana on Tuesday morning as Susan Noyes and John Ruch endure the cold. Toscana was making nine and sometimes ten knots under forestaysail and triple-reefed mainsail.

Ben Ames, Sherry Jagerson, and Nick Noyes

Toscana rarely experienced a sea that was much more dangerous than the ones that had driven Hamburg during the force 10 gale forty-three years earlier. We kept going at near maximum speed and under excellent control, we were able to tack into the wind and around Fastnet Rock, and the two helmsmen, Eric Swenson and myself, were able to steer for hours without losing control of the wheel. As Eric wrote later, “It was a wrestling match, but one that was never in doubt.” By comparison, the helmsmen of Aries, a forty-six-footer on the American Admiral’s Cup team, at times could not hold the steering wheel. “The boat was totally out of control,” her navigator, Dave Kilponen, remembered. Aries rounded Fastnet Rock just after midnight; by 2:00 A.M. Tuesday, she was swept by breaking waves about once every ten minutes. The farther east she sailed, the rougher the seas became. At 5:00 A. M., when she was about fifty miles east of the Rock, she was being swept once every minute. As she surfed down waves under storm jib alone, Kilponen said, “the rudder started with a low vibration and ended up a jet engine whine.” The mast shook so violently that a running backstay fell off and a spreader cracked.

Aries was a type of boat different from Toscana, light, shallow, and tricky to sail well. Yet a boat about five hours ahead of her that was very similar in concept to Toscana was having her difficulties, too. This yacht was Tenacious, a sixty-one-footer owned by the flamboyant American Ted Turner.

Tenacious rounded Fastnet Rock at 6:30 Monday evening. Assuming that she averaged nine knots as she sailed closehauled and then reached toward the Isles of Scilly, she was approximately ninety-five miles down the course at 5:00 A.M., when Aries’s worst troubles started and when Toscana turned the Rock. At about that time, when Toscana was beating to windward over the last few miles under triple-reefed mainsail and forestaysail in about fifty knots of wind, Tenacious—thirteen feet longer, more stable, and more buoyant—was reaching across at least sixty knots of wind under number-4 jib alone. Turner had ordered the mainsail lowered just after midnight. Even under this small rig she suffered knockdowns. Once she was badly rolled while her navigator, Peter Bowker, was on deck trying to fix her position with a portable radio direction finder. Bowker, who was not wearing a safety harness, was thrown heavily against the helmsman, Jim Mattingly, and their combined force dented the stainless-steel steering wheel. Gary Jobson, a watch captain in Tenacious since 1977, noticed that for the first time in his experience she was leaking.

When the wind veered into the north-west and came directly over the big white sloop’s transom, Turner’s crew set the number-4 jib and the reaching jib “wing and wing”—one trimmed to port, the other trimmed to starboard, and each held steady by a spinnaker pole that was secured to the mast. This is the classic rig for running before strong winds; boats of all sizes have sailed for weeks on end like this, dead before the wind and easily steered, since the sideways forces on the two sails tend to balance out. It is an illegal rig for racing if the mainsail is also carried. Tenacious ran this way for a period of at least two hours, according to Greg Shires, who was in her crew. Meanwhile, many other boats were difficult to steer until their skippers sailed a safer and longer course ten or twenty degrees to windward of a dead run. (Tenacious eventually won the race with best corrected time.)

If Toscana had been sailing near Tenacious, I doubt if we would have been able to carry more sail area than the larger boat did. Designed by the same man, Olin Stephens, and with approximately the same shape and proportions, the two boats probably behave similarily in rough weather, which is a way of saying that the conditions in which they were sailing were strikingly different.

Ted Turner’s Tenacious, a sixty-one-footer, was near the area of greatest distress. During one roll, her navigator was thrown Into her helmsman and the steering wheel was dented. Tenacious eventually won the race on corrected time. Barry Pickthall

Another big American boat, Boomerang, a sixty-four-footer owned by George Coumentaros, rounded Fastnet Rock about three hours behind Tenacious. When the force 10 gale swept in, her crew shortened sail until they flew only the number-4 jib—the next smallest to the forestaysail and the storm jib. At 8:00 A.M. the wind increased. The crew set the forestaysail and, during a bad knockdown, cut the sheets, halyard, and tack on the number-4 jib, allowing the sail to blow away to leeward. The waves built until, under forestaysail alone, the big yacht began surfing wildly at enormous speeds, once registering 24.6 knots on her speedometer. A major problem was avoiding other yachts. “We set a careful watch for smaller boats laboring in the troughs of waves as we raced down the crests,” a Boomerang crew member, Jeff Neuberth, wrote in Yachting after the race. “Avoiding collision was of paramount concern. We passed twenty to thirty boats with either bare poles and a skeleton crew or no crew on deck at all, and several boats hove-to with minimal canvas set. . . . The rescue helicopters, the spotter planes, and the radio traffic all indicated to us that the smallest boats were really having a rough go of it. The radio traffic to and from the Overijssel and the number of helicopters in the area indicated that the severity of the wind and sea were getting to the smaller boats.” The gale could also have been getting to the larger boats, but Neuberth, like many crew members in big boats that day, clearly had faith in his own vessel if only because of her size. If Boomerang was close enough to the area of greater problems to see the rescue helicopters and hear the guard ship’s radio transmissions, then the wind and sea that were driving her to such great speeds under so little sail must also have been experienced by the boats in distress. She was roughly one hundred miles down the course at 8:00 A. M. Fifty miles to the north-west, Toscana’s anemometer showed a steady fifty to fifty-five knots, and under considerably more sail than Boomerang was carrying, we rarely reached speeds higher than ten knots as we surfed down long, high, and manageable waves.

Another big boat ahead of Toscana was Siska, a lightweight seventy-seven-footer owned by an Australian, Roily Tasker. “I’ve never seen anything worse, and I’ve sailed in fifty-five knots before,” one of her crew members, Gerry McGarry, told a reporter from the Sydney Morning Herald. “The tops of the waves were breaking and toppling over in the wind. We could imagine what they could do to a small boat. We continued racing, but it was survival conditions, really. . . . Our thoughts were for the little boats when we started getting distress calls. We were kept busy relaying the calls.” As if to prove—despite the laws of proportion and the confidence of their crews—that even large boats were not immune from the gale, Siska’s boom broke as the wind died, and she finished the race with her mainsail awkwardly trimmed.

Meanwhile, the small yachts on which everybody was expending so much concern were coping with the gale with various degrees of success. Three or four hours ahead of Toscana, fast boats like Imp and Eclipse reached along under mainsail or small jib alone. Many crews later said that they would have preferred to set storm trysails, but because the race regulations had not required them, the weight-conscious crews had not brought these small sails along. With jibs set alone, way forward on the bow, many boats were unbalanced and difficult to steer. The helmsmen had to work hard to stay on course and to avoid broaching. In Toscana, more able to carry sail, our triple-reefed mainsail and the forestaysail were set so closely together that the center of pressure of the wind on the sails was almost directly above the center of pressure of the water on the hull. Steering the unbalanced boats was like driving a car with poor shock absorbers and a back trunk full of sandbags: the front end is light, the back end is heavy, and on every sway to one side the car wants to steer to the other side. In both cars and boats, imbalance demands extremely careful steering if the vehicle is to stay on course. Steering the better balanced Toscana was like driving a well-tuned car in which the weight is evenly distributed. Control was positive and relatively untiring.

After their carbon fiber rudder snapped, the crew of Casse Tete V steers using a spinnaker pole as a rudder, as big seas still run. Ambrose Greenway

Whether or not they were unbalanced, an enormous number of boats went out of control in the seas. The postrace inquiry conducted jointly by the Royal Ocean Racing Club and the Royal Yachting Association included a questionnaire sent to all Fastnet race boats in which the skippers were asked if they were knocked down to horizontal or almost horizontal (90 degrees) and beyond horizontal (including a 360-degree roll). Of the 235 skippers who responded to the questionnaire, fully 113 (or 48 percent) said their boats had been knocked down to horizontal or almost horizontal. Amazingly, 77 skippers (or 33 percent) said they had been rolled over. In other words, 25 percent of the entire 303-boat Fastnet race fleet capsized entirely—the equivalent of one-quarter of all cars in the Indianapolis 500 crashing. In the accounts of the handful of previous capsizings of individual boats—off Cape Horn, or in Atlantic storms—the point has usually been made that the crews were extremely lucky to have survived. That the calamity occurred to so many boats in a single twenty-hour period is mind-numbing evidence of extraordinary conditions.

A boat that runs before a gale at too great a speed may capsize by going too fast down the face of a wave, pushing her bow into the back of the wave ahead, and pitchpoling over her bow onto her deck. More likely, she may broach (heel to one side and suddenly head in the other direction) on the face of one wave, end up with her side to the waves, and then be smashed amidships by several tons of water breaking off the following wave. If sailing too slowly, she may be overtaken and “pooped” by a wave that breaks over her stern and into her cockpit. Such a breaker could swamp her and eventually roll her over. Lying ahull, at about thirty degrees to the direction of the waves with no speed on, is thought by many sailors to be the best way to avoid pitchpoling, rolling, and pooping. But in massively breaking seaways, the boat may be even more vulnerable lying a-hull than she would be running before it under control or heaving-to—working slowly across the seas under a storm sail.

Police Car, a lightweight forty-two-foot boat on the Australian Admiral’s Cup team, was three times knocked over to about 120 degrees, putting her mast in the water, while running before it at what her crew thought was a safe speed of five or six knots. Apparently, she was going too slowly to allow the helmsmen to steer around bad waves. Her crew recognized the problem and increased her average speed to about eight knots by changing the trim of her storm jib (the only sail they had up, since even with four reefs the mainsail was too big; her owner had not brought a storm trysail). She sometimes surfed down waves at much higher speeds, and her helmsmen had to be alert to any bad waves that might come along or that they might plow into. Chris Bouzaid, an experienced ocean-racing sailor, was a helmsman in Police Car; later, he described the conditions in an article in Yachting:

“. . . Every sea was different. Some of them we would square away and run down the front of. Others were just far too steep to do this. One imagines a sea to be a long sausagelike piece of water moving across the ocean. However, this was not the case at all as these seas had too many breaks in them and were not uniform. We found that in many cases we could pick our way through the seas, finding a little valley between seas and ducking through, now that we had more boat speed. Once we got all of this together, we had very little trouble. We found that we were managing to avoid all the breaking seas, either by cutting through the sea and going beyond the breaks, or bearing away on the sea prior to the break to avoid having it hit the boat. During the next four hours, we were in fact only hit once by a breaking sea, and that was only because the helmsman (me) was talking to the other crew members and not concentrating on the job at hand.” Unfortunately, few helmsmen of Fastnet race boats were as skillful and knowledgeable as Bouzaid.

Another vivid description of the sea was written for private circulation by John Ellis, owner of the thirty-two-footer Kate. While his estimates of wind strength and wave height were conservative compared with those of other Fastnet race survivors—the wind, he thought, rarely got over fifty knots and “by no stretch of the imagination could the seas have been higher than twenty-five feet”—Ellis shared in Bouzaid’s belief that the shape of the waves determined their effects:

Police Car, a light, well-sailed forty-two-footer on the winning Australian Admiral’s Cup team, was rolled down several times before her crew discovered that making her go faster also made her more seaworthy. Like many boats, she did not carry a storm trysail; like many crews, they wished they had. William Payne

The frequency was much too short for comfort, giving steep wall-sided seas, streaked heavily with foam and breaking (at worst) in the top six feet. More usually, the top three to four feet would break. What seemed to happen was that three or four seas would build up into a succession of breakers, although these would not break along their whole length but in isolated cusps which, having broken along their length, would then break outwards behind the fast-moving crest in a sort of saucer of outward-breaking crestlets. At no stage did we see the force 11–12 type of spume (which we have read about but not seen) which is said to turn the whole sea surface into one coherent, blinding sheet of wind-borne spray.

Looking downwind, one could see the wave trains forming and dissipating in moderate order with, occasionally, the odd monster humping its back well above the average height—say another six feet. The occurrence of these was, as we say, occasional but not unusual and they were responsible for the number of poopings which we experienced. Turning to this phenomenon for a moment, let us confess that we could not, of course, hold our heading of 20 degrees with precision. Normally, we could hold this between 10 degrees and 30 degrees. The total maximum swing was more like 360 degrees to 45 degrees, when hit by breakers. The poopings occurred when we were close to the 45 degree heading, with a breaking sea closing. The helmsman would hear, but not see, the breaker coming: it would break cleanly up the retrousé transom . . . over the helmsman and his relief, into the cockpit, up over the washboard and hatch, and plane on over the ship, leaving cleanly by the bow.

Kate’s experienced crew gave up racing at 4:00 A.M. on Tuesday, when she was about ninety miles from the Rock. They threw over lines and doused all sails. Her owner concluded that she survived at least partly because they kept her speed low. By 10:00 A.M., he wrote, “it was beginning to be borne in upon us that we should come to no harm. Indeed, the owner confesses that during the afternoon watch, he found himself chanting inspiring songs at the wheel, exhilaration having succeeded apprehension.”

Many of the most frightening—in fact murderous—events happened within forty miles of Kate and Boomerang. Heading east in this area were Tenacious, Acadia, and Police Car. Trying to head west were Grimalkin, Trophy, Windswept, and possibly Major Maclean in Fluter. When the coastguards compiled their report on the search and rescue operations conducted by the helicopters, they provided twenty estimated positions of boats and equipment that were located, aided, or retrieved on August 14, 15, and 16. While the positions are not entirely reliable, if only because the pilots were extremely busy with rescue efforts, the trend is clear: most of the distress seen by the helicopter crews took place within a circle with a diameter of forty miles whose center was at 50° 42’ north and 7° 14’ west—a point seventy miles west-north-west of Land’s End, one hundred miles south-south-east of Fastnet Rock, and ten miles north of the rhumb line, or direct course, between the two landmarks. All of the boats located by the helicopters in this forty-mile circle were smaller than thirty-five feet in length. (See Appendix III.)

After the race, many would claim that smaller boats suffered the greatest damage simply because they were smaller boats. This argument was especially popular among crews in large yachts who neglected to see that boats such as Tenacious, Acadia, and Boomerang—each longer than fifty feet—experienced severe difficulties in the same general area. What was special about this area of the Western Approaches was not only that it was filled with small boats but that it was also overflowing with especially strong gusts and dangerous seas. Sixty miles to the north-west, we in Toscana experienced nowhere near the same extremely violent conditions. Only by sheer bad luck did so many small boats find themselves in this area, more than ten hours from shore, just as the gale swept through.

Weather can behave in strange and mysterious ways; calms and storms may be small and localized or they may cover entire oceans. Atmospheric pressure, surface and submarine land formations, and the spin of the earth can combine to create storms out of calms and maelstroms out of millponds. One part of a body of water may be safe while another is lethal. What usually makes the difference is the size and shape of the waves.

Waves often are compared with the motions of a rope secured at one end and moved up and down at the other end at a steady speed. Crests and troughs will migrate from one end to the other in a rhythmic, predictable pattern. The fibers in the rope may stretch, but they do not move. Similarily, the water at the surface of waves does not move markedly in the direction toward which the waves roll (the surface water does, however, rotate in small circular orbits, forward on the crest and backward in the trough). The length of the rope and the strength of the person moving the free end determine the height, shape, and length (distance between the crests) of the man-made waves.

The size and shape of water waves depend upon several factors: the strength of the wind, the amount of time that the wind blows from a given direction, the fetch (or distance over which the wind blows), the depth of the water, and the direction and strength of currents. Through observation and experiment, oceanographers have developed mathematical tables that can help in the prediction of wave height and length. For example, a twenty-knot wind that blows over a fetch of one hundred nautical miles of deep water for twelve hours will generate waves whose maximum height is six feet and whose length is two hundred feet, and which travel at a speed of more than twenty knots. A forty-knot wind with the same fetch and blowing for the same length of time will generate waves as large as thirty feet, with a length of six hundred feet and a speed of more than thirty-five knots. (The reason why wave size increases by a factor of five while the wind speed merely doubles is that the wind’s force is directly proportional to the square of the wind speed.) As the wind dies, so do the waves, but at a much slower rate.

When waves encounter contrary currents, they increase in size by large factors. The Scripps Institute of Oceanography, in California, estimates that wave height may be doubled by a contrary current of only two or three knots. Likewise, waves increase in height when they pass over shoal water, and changes in the contour of the sea bed, even in relatively deep water, may affect the height of waves. As the height increases, a wave may steepen to the point where the base can no longer support the top, and the wave collapses on itself and becomes a breaker. The pile of white water that falls off the top of a breaking wave may be accelerated by the wind that created the wave to begin with.

A type of wave that all seamen fear is the rogue wave, which angles across the train of normal seas and sometimes collides with one to create a breaker. The oceanographer William G. Van Dorn writes in his book Oceanography and Seamanship that 5 percent of deep sea waves are abnormally high “rogues.” They may be caused by distant winds of a force and direction different from the local wind or by some other special circumstance. Usually, these rogue waves pass by vessels with little effect. Judging from the reports of the sailors caught toward the middle of the Western Approaches during the Fastnet storm, rogue waves were more the norm there than the exception.

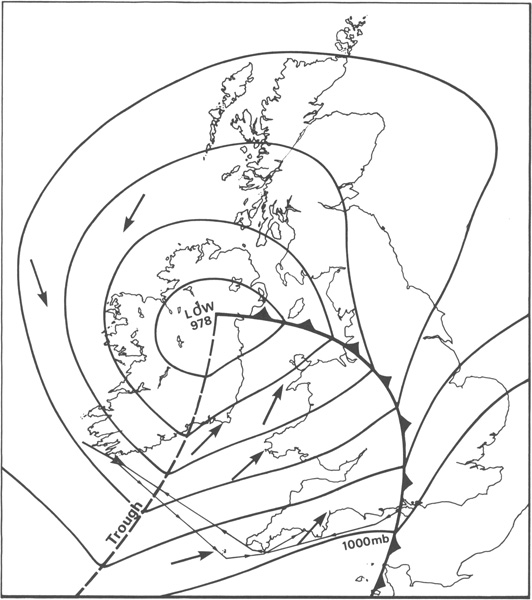

Mathematics were working against the Fastnet race crews. On the top of the long south-west groundswell was one set of waves created by the force 6 south wind that blew all Monday afternoon, plus a second set pushed up by the force 9 and 10 south-west gale that blew from 11:00 P.M. Monday until about 5:00 A.M. Tuesday. When the wind continued to strengthen and veer as the depression passed to the north, the first two sets remained, and by 9:00 A.M. Tuesday there was a third set of waves running in from the north-west. As each set of waves aged, it increased in height and speeded up, so by midmorning Tuesday there was a great clash of ten-, twenty-, and perhaps even forty-foot waves from many directions, creating a sea of breakers.

The depression itself may have contributed to the roughness of the seas. As the fast-moving deepening low (bringing on the fourth lowest barometric pressure for a British August since 1900) sped across the Approaches, it created a mound of water under its center. Before this mound was a surge that, like a big wave, pushed east, creating currents that swirled around the depression and perhaps turned back against the wind. Saltwater people tend to believe that current is caused only by the tide, but on the huge nontidal Great Lakes of North America, one and two-knot currents called seiches are created in the surge of water ahead of moving depressions. On the lakes these currents can conspire with gale-force winds to create mammoth seas that have been known to swallow up freighters and tankers. The same phenomenon may have occurred in the bay-like Western Approaches during the Fastnet gale. In addition, wind can create a current on any body of water—as much as half a knot in a force 6 wind blowing for twelve hours.

The veer in wind direction and in the direction of currents caused by the depression was particularly sudden in the southern part of the low-pressure cell, where the storm had changed its shape from that of a rough circle to a teardrop. A trough of low pressure ran from north to south down the center of this teardrop, and where the trough was deepest, the angle between the contour lines of atmospheric pressure was greatest. Since wind direction tends to be roughly parallel to the gradient lines (actually, angled in at about fifteen degrees around a depression), the wind shift at this point was more sudden than it was at the more gradual turns in the lines of equal air pressure. As well, the wind probably blew strongest in the trough. Directly in the path of this moving line of suddenly veering wind were the boats in the middle of the Western Approaches. Because the wind veer was abrupt, the angle between the old and the new waves was sharp—as much as forty-five degrees.

Apparently, the worst disturbance caused by the depression was relatively local. Later on Tuesday, when the storm swept across southern Scotland, it kicked up waves large enough to force the cancellation of the Hull to Rotterdam ferry on which several horses in the British show jumping team were booked (“Heavy seas delay British horses,” ran a headline in Thursday’s Daily Telegraph), while, 125 miles to the south, the Harwich to Hook of Holland ferry ran on schedule.

There is other evidence that the storm was more violent near the rhumb line between Land’s End and Fastnet Rock than farther south. A man from Houston, Texas, named Bill Wallace was completing a single-handed transatlantic voyage in a thirty-foot sloop when the gale broke on Monday night. By his calculation, he was then seventy-five miles west-south-west of Bishop Rock lighthouse in the Isles of Scilly, and about ninety miles south of the center of the forty-mile circle in which so many Fastnet race yachts suffered damage. Wallace told the company that built his boat (which summarized his report in a news release) that he experienced no major difficulties. He lowered the sails, set the self-steerer to keep the boat at an angle of 30 degrees to the wind, and went below. Unlike many of the boats that lay a-hull at the same angle, his was rolled down only once, to 120 degrees (“And I’ve got the coffee stains on the cabin overhead to show it”), and flying tin cans cut his scalp. Solid water never came on deck or below. His boat, an American design called the J-30, is not radically different from boats such as Grimalkin and Windswept. Wallace also reported that the night never darkened. “By nightfall in the middle of the gale, the stars were out, then the moon came up,” he said. The only light that many Fastnet race crews saw was that from a flare, and we in Toscana enjoyed the moon for only half an hour before the blackness closed back in. (Like many people who were on the sidelines, Wallace could not resist the temptation to judge the Fastnet crews. “There was a lot of panic out there,” he said. “Those people racing haven’t encountered the ocean and what it can be like. Most of them have just been sailing around bays and harbors.” What he probably did not know was that, whatever their experience, most of the racing crews probably faced exceptional conditions quite different from those that he encountered that same night.)

A synoptic chart of Low Y at 7:00 A. M. (British Summer Time) on Tuesday, August 14. The drastic wind shift in the trough was probably a major cause of the dangerous seas In the middle of the Western Approaches.

A problematical explanation for the extraordinary seas involves a bank of relatively shallow water that lay in the path of the trough of low atmospheric pressure and its violent winds. Called the Labadie Bank, it is about ten miles south of the Land’s End to Fastnet Rock rhumb line and is also near the forty-mile circle. This relatively shoal area has depths of between twenty-one and fifty fathoms and averages about forty fathoms (a fathom is six feet). The water in the Western Approaches is by no means deep, since it lies over the European Continental Shelf and has an average depth of about sixty fathoms. Although oceanographers have argued that a difference in depth of twenty fathoms so far under the surface is not significant enough to cause especially bad waves, the Labadie Bank has earned a reputation for rough water among the fishermen who frequent it.

At least one yachtsman has agreed with the fishermen. During the 1931 Fastnet race, the fifty-one-footer Maitenes II was swept over the Labadie Bank in a rapidly veering force 9 to force 10 gale much like the 1979 storm. Her skipper, Commander W. B. Luard, Royal Navy (Retired), later devoted a chapter in his book Where the Tides Meet to the race and the storm.

“Had we been in open waters,” he wrote, “she would have lain, as she wished, under bare poles with absolute safety; but the steepness and the irregularity of the breaking seas made it essential, in my opinion, to keep her bow or stern to them at all costs.” A drogue was thrown over the stern to slow her down, and the crew began to pour fish oil into the sea to attempt to flatten the waves, an accepted storm tactic. It was at this point that Colonel C.H. Hudson was washed overboard while adjusting one of the oil bags. He grabbed the line to the drogue, but it was torn from his hands and, weighed down by foul-weather gear and boots, he sank.

As she drifted east at six knots, Maitenes experienced increasingly vicious seas that occasionally came over the stern and pooped her. The crew, demoralized by the loss of the colonel and exhausted by their efforts, sighted a trawler and sent a message by semaphore requesting that it stand by until the gale moderated, when they could be taken off. “I estimated we were then approximately eighty miles south-east (magnetic) of Fastnet Rock,” Luard wrote. He went on:

“About an hour later, wind and sea having again increased, I semaphored that we could no longer run with safety if the weather became any worse, and the trawler replied that she had just received another gale warning. The seas now changed in character—we were on the Labadie Bank—became still steeper, still more confused and irregular, running in from all sides; and we were pooped heavily several times. Though the glass [barometer] had just started to rise it seemed likely, in view of the renewed gale warning, that it would blow harder than before from west and north-west and drive us onto a lee shore in less than eighteen hours, with, as likely as not, the trawler standing by unable to be of any assistance. On the other hand, it seemed possible that the gale might moderate in time to let us heave-to again on the starboard tack and work clear [of the Cornish coast]. I realized, however, that the ship [Maitenes] was in imminent danger of being fatally pooped, and after considering the situation from every point of view, I concluded that I was not justified in taking further risks.”

Luard fired off flares, and after great effort and some damage to the yacht and the destruction of the trawler’s dory, some fishermen came aboard. As “the ship was clearing the bank, the seas became more regular, and soon the wind started easing.” The next morning, Maitenes was taken in tow for Swansea.

“Maitenes is a magnificent sea boat,” Luard concluded. “Had we not been driven over the Labadie Bank all would have been well, and had we been off soundings [in the open ocean] there would have been no cause for anxiety; for she could have been left to her own devices, if overpowered by the weight of wind, or been put before the seas and allowed to run with perfect safety. . . . The sea this year was the steepest I have yet seen, often too steep for any boat to rise to; but it seemed, at times, as though the drogue tended to keep her stern from lifting freely. . . . I have come to the conclusion that if caught in a similar sea again I should not attempt to reduce a ship’s speed as much as possible, nor keep her running at full speed . . . but aim at striking a happy medium.”

Thus did Luard unknowingly anticipate the seamanship problems that so challenged the men and women who raced over the same waters many years later. He ended his account with a warning: “Granted that identical conditions would not be met once again in a thousand times, but it is the thousandth chance that may lead, alas, to tragedy and disaster.”

So strongly did Luard believe that the Labadie Bank was important in the creation of bad seas in the Western Approaches that he did not try to explain exactly how such a deep shoal could have such a great effect. Oceanographers might challenge his assumption as another fishermen’s superstition, and it is true that fishermen-or at least the English and French fishermen with whom I have talked-fear the bank in bad weather. It is also true that Maitenes II, and many boats in the 1979 Fastnet race, confronted increasingly dangerous seas as they approached the area of the bank. There is no question that the real culprit in both storms was the rapidly shifting force 10 to force 12 wind, which in 1979 veered through 135 degrees, from south to north-west, in a little more than twelve hours. Perhaps the Labadie Bank was disrupting an already confused sea just enough to turn it into a mess of “the most fearsome things.” Or the immense variety of winds, waves, surges of water, and currents created by the deep, fast-moving storm could have focused all their energies on the area of water that lay approximately one hundred miles south-south-east of Fastnet Rock.

Whatever the cause of the seaway, there is no doubt about its effects, and, despite the convictions of Commander Luard and several of the survivors of the 1979 storm that they had finally figured out how to survive in those waves, no single storm tactic was a guarantee against disaster. Hilaire Belloc once wrote, “The sea drives truth into a man like salt.” The truth here is that there are occasions when men can do little or nothing to help themselves.