The lifeboat Guy and Claire Hunter, from St. Mary’s, Scilly Isles, in the Western Approaches on Tuesday afternoon. She escorted two boats to port and towed Festina Tartia (which had lost one man) and her surviving crew of six to St. Mary’s. Royal Navy

EVER SINCE NOAH, the sea has been a symbol of both salvation and destruction. When Jonah escaped to it, the sea, acting as an agent of God’s wrath, almost killed him. After parting for Moses, it drowned the Egyptians. Noah’s flood, in fact, is not unique. Among the flood myths of other cultures is that of the pre-Columbian Aztec Indians of Mexico, whose calendar stone depicted three ages of progress leading to a fourth age of destruction. In this fourth age, as Joseph Campbell writes in The Mythic Image, “water, gentle mothering vehicle of the energies of birth, nourishment, and growth, became a deluge.” Western man has learned to use the sea for pleasure, and fear of the sea’s violence may have become less conscious than faith in its powers of regeneration.

The people of the west of England are not so sanguine. An English folk tale relates how the sea off the north coast of Cornwall calls for its victims. One calm night, “when all was still save the monotonous fall of the light waves upon the sand,” a seaman—a fisherman, perhaps, or a pilot—took a walk on a Cornish beach near Porth. A voice came to him from the Western Approaches: “The hour is come, but not the man,” the voice said, and repeated the strange message three times. Looking inland, the seaman saw a dark humanlike figure standing on the top of a nearby hill. The figure paused for a moment, and then rushed down the hill and across the beach, and disappeared into the sea.

Lured by fate, profit, or pleasure, men have been rushing down the hills into English waters for centuries, and not all of them have survived. The sea is a common denominator for everybody who lives on the British Isles. Its attractions are represented by a popular BBC television show in which a pleasantly inquisitive man named John Noakes travels Britain in his small ketch, seeking out interesting people. (By contrast, in an American version of Go with Noakes, Charles Kuralt traveled in a mammoth, gas-inhaling camper.) Lifeboat stations are listed along with fire departments on pages devoted to emergency telephone numbers in local directories. Until quite recently, shipwreck and drowning on a massive scale were an accepted part of British life. In 1864, 1,741 ships and 516 lives were lost around the coastline of the United Kingdom; in 1880, 1,303 ships and 2,100 lives; in 1909, 733 ships and 4,738 lives. As the ships decreased in number, they increased in size, so every wreck killed more people than the previous one. On one day in 1859, 195 ships sank or were wrecked. During November 1893, 298 ships foundered.

One of the very worst places for wrecks is the eighty-squaremile archipelago of the Isles of Scilly, twenty-eight miles off Land’s End and almost that distance out in the Western Approaches. Gales there are bad and frequent, currents are confused, seas are wild. Until the mid-nineteenth century there was no lighthouse to protect seamen from the chain’s west and south sides, and ships searching for the Channel or the Approaches often ran aground there. Constructed on a rock not much larger than a wide boulder, Bishop’s Rock lighthouse now towers over the islands; sometimes, the spray from breaking waves seems to tower even higher. Now guarded on the south-west by the Bishop, on the north by Round Island light, and on the east by Wolf Rock and St. Mary’s lights, the fifty-odd islands and islets and many rocks of the Scilly Isles are still not much less dangerous now than they were in the 1860s, when they and other landmarks in the Land’s End area accounted for the loss of 394 ships, or in 1875, when 335 people died after the ocean liner Schiller foundered on the Retarrier Ledges. It was on the Seven Stones rocks off the Scilles that the tanker Torrey Canyon split apart in 1967, spilling a life-threatening amount of oil into the clear waters and onto sandy beaches in Cornwall, Devon, and Brittany

That no oil fouled the Isles of Scilly is not really surprising. The lucky, semitropical islands have, like the sea around them, been a haven as well as a danger since they were first settled about 3000 B.C. A reflection of this security is one of the charges brought against Thomas Seymour in 1549, when his aspirations to gain control of the crown became known. He was accused of buying “the strong and dangerous Isles of Scilly” and conspiring with pirates to use them as a refuge “if anything for his demerits should be attempted against him.” Scillonians (as the islanders call themselves; they are not Cornishmen) have always made excellent use of the chain’s isolation and natural strengths, first in Bronze Age tribes, then in medieval religious orders seeking privacy, next in fishing communities, and now in tourist associations.

Throughout, the Scillonians, like island people everywhere, have willingly accepted what the sea has provided for them, and among those gifts have been wrecked ships. From the days when church services were ended at the arrival of news of fresh wrecks, salvaging has been an important part of Scilly life. A man could win a healthy part of a year’s income during a few hours of dangerous, wet work helping to salvage a stranded vessel or her cargo.

Today, wrecking remains important but in different ways. Divers, primarily from the mainland, have found treasure in and around the wrecks of four Royal Navy ships, including HMS Association, that were blown by gales onto rocks in 1707, with a loss of almost two thousand men. Other divers have searched for vases and paintings belonging to Sir William Hamilton, the husband of Horatio Nelson’s Emma, which were lost when the Colossus sank in 1798. There are others: the Hollandia, whose recovered treasure brought nearly £100,000 in auction; the Princess Maria; and some 540 other wrecks lying within eight miles of the islands.

Competing with this revival of the salvage business is a small wrecks artifacts industry. A family named Gibson has photographed Cornish and Scilly wrecks since the 1860s, and their shop in Hugh Town, on the chain’s main island, St. Mary’s, is wallpapered with dramatic, gruesome pictures that are for sale at £1.50. Gibson photographs illustrate at least four books on Scilly wrecks. And on the nearby island of Trescoe, figureheads, trailboards, and other ornaments from wrecks are on display in the aptly named Valhalla Maritime Museum.

While their survival has been dependent upon opportunities provided by visitors, both intended and accidental, Scillonians are warmly generous people. Perhaps their good-heartedness and sympathy toward people in trouble is an admission of their own vulnerability. One Saturday a few months after the Fastnet gale, a “jumble,” or bake sale, was held in the tiny schoolhouse on Trescoe Island, on which the famous gardens flourish. The beneficiaries were the Cambodian refugees, whose horrible conditions had just become widely publicized. Children contributed toys, and adults brought pies and jams to the sale. The winter population on the island is not much more than a hundred people, including children, and is not wealthy, yet the sale raised £50.

Two miles and a rough thirty-minute boat ride away in Hugh Town, the Scillies’ metropolis with perhaps five hundred yearround residents, stands the great symbol of the Scillonians’ generosity of spirit—the boathouse in which rested their lifeboat, the Guy and Claire Hunter. There has been a volunteer lifeboat station on St. Mary’s continuously since 1874. The island’s lifeboat crews had, by November 1979, rescued 627 survivors of founderings.

Scillonians are not the only people to care about saving lives at sea: in Great Britain and Ireland there exist more than two hundred and fifty stations of the Royal National Life-boat Institution, over half of them on year-round duty with boats designed to withstand force 10 and stronger gales in open water. The RNLI was formed in 1824, during the first great boom of commercial sail. As ships increased in number, so too did shipwrecks and loss of life. Acting partly out of the humanitarianism that seemed to strengthen in England along with commerce and the empire, and partly out of fascination with the technical challenge of designing safe boats for difficult conditions, a wealthy idealist named Sir William Hillary founded what was then called the National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck. Among the institution’s original policies that survive are rules that it be supported by donations; that widows and children of lifeboatmen who die in service be provided for; that special gallantry be recognized with awards; and that, regardless of nationality, any person in distress be attended to.

It took a while for this internationalist, humanitarian organization to gain popular attention. The cause received a boost in 1838 after the exploits of Grace Darling were widely publicized. A lighthouse keeper’s daughter living in the Fame Islands, in north-east England, she helped her father rescue five people stranded on a wrecked paddle steamer. Fifty-four people were lost in the wreck. The contrast between the tragedy and the unassuming twenty-two-year-old heroine stimulated immense public interest in lifesaving. (Grace Darling died of tuberculosis four years later.)

As it grew, and as its vessels developed from rowboats to sailing gigs to the massive forty- to fifty-five-foot twin-screw power vessels in use today, the RNLI evolved into a large organization that stood above politics and dispute. The only large American institution even remotely like it is the Red Cross, except that the Red Cross is so ubiquitous in American life that it is all but taken for granted. Nobody takes the lifeboats for granted. On almost every shop counter in England, near the shore or inland, stands a small piggy bank with the shape of a lifeboat. Daily newspapers report lifeboat services (rescue efforts), whether successful or not, in the most respectful language. Sir Winston Churchill’s patriotic words about the typical lifeboat summarize the universally held belief that its crews are somehow superhuman: “It drives on with a mercy which does not quail in the presence of death, it drives on as a proof, a symbol, a testimony, that man is created in the image of God, and that virtue and valor have not perished from the British race.”

Whether the ten thousand or so lifeboatmen actually believe everything that is said about them is doubtful; many if not most of them are but fishermen in small communities, and the burden of personifying such an institution can be heavy. In any case, few are singled out for national attention, and the head office of the RNLI usually exerts little control over a station’s activities. For most lifeboatmen, the local station is the RNLI, and although headquarters in Poole allots them funds and equipment and periodically inspects their boats, they feel beholden to nobody except themselves. Ask a lifeboat coxswain, or skipper, how many people his boat has saved and he will point to a plaque that details every service that his station has performed. Ask him how many have been saved in the history of the RNLI, and he probably will shrug his shoulders. (The answer, provided by the organization’s headquarters, is about ninety-five thousand people.)

When the 1979 Fastnet storm struck, the coxswain of the St. Mary’s lifeboat was, and had been since 1955, Matthew Lethbridge. He succeeded his father as cox, and his father succeeded his father. The three Lethbridges had commanded the St. Mary’s lifeboat for 80 of the 123 years that there had been a station on the island. (The station was founded in 1837, abandoned in 1855, and revived in 1874.) A small, wiry man in his mid-fifties, Lethbridge was one of the few fishermen in Hugh Town who worked his traps and nets alone. He lived in a small row house with his wife and daughter, fished, mended his traps in the off-season, and waited for the call that, he knew, eventually would come from the coastguards to the station’s secretary, and then to him. The records that he kept with white paint and brush on black plaques in the boathouse testified to his activities. In some years, the Guy and Claire Hunter was called out ten or twelve times; in other years, she and her eight-man crew went out less frequently. Unless there was a service, they were required to go on a test run every two months, and once a year an inspector came down from RNLI headquarters to look the boat over.

Sometimes when they went out, the crew had little more to do than to tow a disabled yacht through the maze of unmarked rocks that protects Hugh Town’s harbor. At other times, though, there was serious lifesaving work. In 1955, his first year as cox, the institution awarded Matt Lethbridge a bronze medal, its third-highest award for gallantry, for his efforts in rescuing a crew of twenty-five from a Panamanian steamer. Twelve years later, the boat took twenty-two men off the Torrey Canyon. Also in 1967, he was awarded a silver medal (the second-highest award) and his second in command and the boat’s engineer received bronze medals for rescuing nineteen people from a large German power yacht and towing her to safety during a gale—a twenty-seven-hour service. Subsequent silver medals came three and nine years later.

Surrounded by holidaymakers, the St. Ives lifeboat is hauled out late on Tuesday afternoon. She was at sea for nine hours, thirty-four minutes, and rescued a French yacht taking part in a single-handed race. A. W. Besley

Lethbridge’s grandfather had taken the then Prince of Wales (later the Duke of Windsor) out in a lifeboat, and he himself had shown the present Prince of Wales around the Guy and Claire Hunter during one of the Prince’s visits to St. Mary’s. “We’ve been out in the Britannia, Pat and me,” Lethbridge has said proudly, nodding to his wife. Perhaps it was the only way the Queen could have met him, since Lethbridge had visited the mainland only three times in thirty years, and on one of those occasions, when he went to London in 1976 to receive the British Empire Medal, the Queen was unable to award the medal personally.

Except for the few times when he endured London, Matt Lethbridge had never been away from the sea. During World War II, he served in Royal Air Force search and rescue boats, and returning to St. Mary’s, he stepped directly into the lifeboat under his father’s command. The second coxswain then was his uncle James; his brothers Harry and Richard now served in his own crew. In 1979, however, the family tradition was about to end, since Matt Lethbridge had no son. Finding a qualified successor for Lethbridge when he would be forced by RNLI statute to retire, at the age of sixty in 1984, might prove to be one of the handful of major crises that the people of the Isles of Scilly have had to face. His standards were high and his reputation was unsullied by any hint of error. Locating a man of Lethbridge’s character and skills would have been hard enough in the old days; the facts of life in the late twentieth century seem to discourage the kind of independence and dedication that make such men what they are. With the appearance of huge Russian factory ships and highly efficient smaller vessels, the waters around the Scillies were becoming fished out. Meanwhile, a great influx of tourists during the 1970s had made island life expensive. Some Scillonians adjusted to the new economy and thrived, or at least made do as landlords of guest houses. Others succumbed to the temptations offered by a runaway real estate market and sold their homes to vacationers and moved to the mainland. Scillonians dependent upon fishing or flower farming for their living could but look on with amazement at the way island life had changed. They survived by performing odd jobs. At one time or another, Matt Lethbridge had been a carpenter, a boatbuilder, and a butcher besides tending his nets and traps. He and men like him had stocked the lifeboat for generations, and as they aged, fewer independent, younger men seemed to be there to replace them.

Those worries were not on Matt Lethbridges mind when he was awakened by the telephone early on the morning of August 14. Before the honorary secretary, Tom Buckley, said anything, Lethbridge had guessed the gist of the message. He heard the wind whistling through the streets of Hugh Town, and he knew that it was about the time of the Fastnet race, whose boats he sometimes saw when he was out pulling his crayfish pots near the Bishop. Tom Buckley passed on a message from the Coastguard: a rudderless yacht named Magic was in distress about forty miles north-west of Round Island light.

Lethbridge pulled on his clothes. Five minutes and a fast walk later, he was in the boathouse, which stood twenty feet above the water on a point of land between Hugh Town and Porth Mellon, the old shipbuilding town. Once inside the boathouse, he walked past the tall plaques on which he, his father, and his grandfather had faithfully recorded the services of their lifeboats and past the little room with the marine radio scanner, which, like the instruments in his and every Stilly fisherman’s home, automatically searched the frequencies for a transmission. Through a door was the large shed in which sat the Guy and Claire Hunter, high and dry on a trolley. Out of the water, she looked from below like a submarine, forty-seven feet of black and red, powerfully curving in great symmetrical rounds. There was nothing squared-off or blunt to offer unnecessary resistance to waves. A Watson-type lifeboat, she had been designed especially for this duty.

Within minutes, Lethbridge and his seven-man crew were aboard and suited up in foul-weather gear, life jackets, and safety harnesses. With him were the second coxswain, Roy Guy; the mechanic, Bill Burrow, the second mechanic, Harry Lethbridge; the bowman, Richard Lethbridge; and the crewmen, Rodney Terry and Roy Duncan. With the exception of Burrow, the mechanic, whose full-time job it was to maintain the boat, they were volunteers for the first few hours on a service, after which they would receive low pay and, if they were lucky, a reward from anybody they rescued. By tradition, they would not claim salvage on a boat even if they were entitled to it.

Down under the boat, the launchers and slipmen were preparing for the launch. They opened the boathouse doors, letting in a great blast of wind, and after warning the men on deck, let the trolly go. It slid down a ramp, out of the boathouse, and into the water. The time was 3:00 A.M. When the lifeboat drifted clear of the trolly, Matt Lethbridge, standing behind the huge steel wheel in the steering cabin, started the twin engines and pulled away from the ramp. Navigating by memory and radar, he steered through the channels between the islands, islets, and rocks of the Scillies and out into the Western Approaches.

He was not at first surprised by what he saw there. Although he could boast mildly, “Unless it’s blowing about seventy, we never used to call it a gale of wind,” Lethbridge had occasionally been unsettled by bad weather. A storm in 1974 left his pots hanging off a ledge on the Bishop Rock lighthouse, seventy feet above normal water level. Once he saw spume blow entirely over Trescoe Island, which is two miles long and almost a mile wide and whose maximum elevation is more than a hundred feet. The same gale blew in a four-inch-thick door in the Round Island lighthouse and lifted a hundred-pound boulder several yards up a cliff from a beach. (Later in 1979, his normally cheerful face turned grim and he became silent when he heard that two lifeboats similar to his had capsized off Scotland.) But when he spoke about the Fastnet race gale with a survivor, he said, without heroic swagger, “That was an exceptional gale for you, but it wasn’t an exceptional gale for us.”

Sliding at nine knots across the south-westerly seas of the predawn hours, the crew saw no boats until a small cruising yacht under storm jib came by, followed by a large sloop sailing very fast under shortened rig toward the Bishop. Lethbridge guessed that she probably was one of the leaders in the Fastnet race fleet. By 9:00 A. M., when the Guy and Claire Hunter was almost fifty miles north-west of Round Island, the sea was making up with a ferocity that Lethbridge had not expected. He had experienced heavier seas, waves with larger walls of breaking water, but he had not experienced so many breaking waves in these wind conditions. The sea, he observed, was worse than the wind strength would warrant. Several times the lifeboat’s decks were awash up to her crewmen’s waists, and one wave broke through the small window in the back of the helmsman’s cabin, drenching and destroying Richard Lethbridge’s camera, which had withstood several gales. (After the race, the second coxswain of the lifeboat based at Padstow, Cornwall, said, “extreme conditions were exceptional,” in a letter about the gale to a yachting magazine.)

Lethbridge received reports from Magic but they were incomplete and he could not locate the rudderless yacht. His crew spotted HMS Anglesey, the Royal Navy fisheries protection vessel, standing by the dismasted Bonaventure II. When both the lifeboat and the ship were in the troughs of waves, they lost sight of the Anglesey; Lethbridge estimated the maximum wave height at thirty to forty feet and he overheard the Anglesey reporting sixty-footers.

Soon after, they located a Royal Navy helicopter hovering over a yacht named Victride, whose crew seemed to want to be taken off. In a dialogue over their radios, the helicopter pilot and Lethbridge agreed that the crew need not abandon the yacht, but that the lifeboat should escort her to safety. This would allow the helicopter to fly to another yacht in distress several miles away. With all the radio frequencies jammed with distress calls, Lethbridge had to concentrate hard to make out the pilot’s voice and keep track of their conversation. Told that they would be escorted to port, the crew of the thirty-five-foot French yacht appeared satisfied, and they got under way under storm jib. Victride was knocked down several times by waves, and Lethbridge noticed that her companionway hatch was open. Since they did not have the same type of radio, there was nothing much that he could do to help. By this time, Lethbridge had become aware of the extent of the disaster; seven lifeboats had been called out. Soon after beginning to escort Victride, he received a radioed request for help from another yacht, Pegasus. Lethbridge gave Pegasus the course to Round Island, where all three boats made a rendezvous late on Tuesday evening, and the lifeboat led the two yachts into the harbor.

When he docked for refueling at 8:00 P.M., Lethbridge was surprised to hear that the conditions had been as bad at St. Mary’s as in the Approaches. Several cruising boats had dragged their anchors and gone ashore; others had been rounded up by fishermen as they were blown across the harbor toward the beach. Brian Jenkins, a fisherman and slipway helper at the lifeboat boathouse, had even swum after a drifting yacht in order to get a tow line aboard her.

Although Lethbridge looked tired after his 17 hours of pounding, his spirits were high. With a sparkle in his eye, he told his friend Jenkins about the rough seas and how well the lifeboat had handled them. Once the fuel tanks were topped off, he was prepared to go out again immediately, and only after a brisk warning from the town’s doctor did he allow his crew a chance to change into dry clothes and eat a quick meal. By nine, the Guy and Claire Hunter was back in service three miles west of Round Island, where she made a rendezvous with Festina Tertia, one of whose crew had been swept away and another, suffering from hypothermia, taken off by a helicopter. Demoralized, cold, and exhausted, her crew requested a tow into St. Mary’s. The lifeboat crew threw a line, and soon they were underway through Trescoe Channel. At one stage, the line became tangled in the yacht’s keel, and the two vessels drifted alongside each other for a while until the snag was cleared. By midnight, the yacht was secured at the town quay and Matt Lethbridge and his lifeboat crew were in their homes, having been out for a total of 19 hours, 45 minutes. The thirteen lifeboats called out from English and Irish stations during the gale were in service for 169 hours, 36 minutes and towed in nine yachts and escorted nine more. Some seventy yachtsmen were aboard the yachts towed in.

The St. Mary’s lifeboat was in service for more than 19 hours on Tuesday. Twelve other lifeboats were In service for a total of more than 133 hours on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday. Fatigue shows on the faces of the crew of the lifeboat on return to its station. The man holding the cup is the coxswain, Matthew Lethbridge. Gibsons of Scilly

Yet an irony of the gale was that the lifeboats were not able to perform their primary mission—to save lives. Only when transferring a few rescued sailors from commercial vessels to shore did any lifeboats actually carry survivors; the rest of the time, they were either searching for, escorting, or towing yachts. The actual rescues of sailors from the water or from life rafts were performed by helicopters, commercial vessels, or yachts. This was true largely because the area of greatest distress was fifty to one hundred miles from the lifeboat stations that were called onto duty, a distance that a normal lifeboat powering at nine knots could cover in no fewer than five or six hours but that a helicopter could fly in less than half an hour.

A prototype of a new type of high-speed lifeboat, the fifty-four-foot Arun, was stationed at Falmouth, on the Channel side of Cornwall. Named the Elizabeth Ann, she and her crew were offshore for more than forty-three hours during the gale, at first looking for a boy missing from a beach near Falmouth, then, after a hundred-mile sprint at seventeen knots around Land’s End, searching for distressed yachts in the Western Approaches. When she towed a rudderless Swedish yacht, Big Shadow, into St. Mary’s on Wednesday, some Scillonians were mildly offended that she and not the Guy and Claire Hunter performed the service, although Matt Lethbridge paid a friendly visit to the Falmouth crew and inspected their boat. Later on Wednesday, she took the abandoned Golden Apple of the Sun under tow from HMS Broadsword. On returning to Falmouth at noontime Thursday, the Elizabeth Ann had run four hundred and fifty miles and used a thousand gallons of fuel. Her crew had eaten only what little food they could find in the yachts. Toby West, her coxswain, told a reporter that the crew of Big Shadow had been warmly grateful for their rescue. “It is hard in such circumstances,” West said, “to just say that you are a lifeboat doing your job.” West then went back to racing a sailing fishing boat in the annual Falmouth regatta.

The crew of Casse Tete V, whose rudder had broken, secures the tow line from the lifeboat Sir Samuel Kelly, based in Courtmacsherry, Ireland. The tow to port lasted twelve hours. Ambrose Greenway

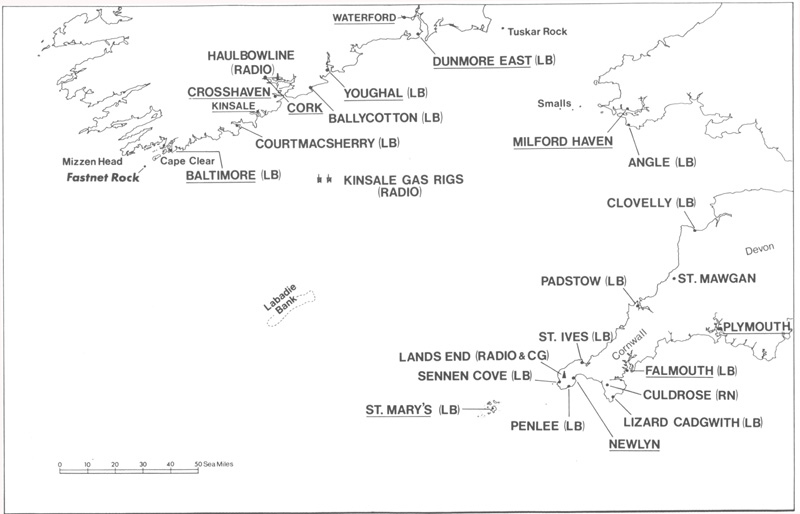

Places that feature in the search and rescue operation. Ports of refuge are underlined. “LB” Indicates lifeboat stations. Land radio stations using marine radio frequencies are indicated by “Radio.” St. Mawgan and Culdrose are military air bases.

An exhausted sailor is helped out of a van at the Cuidrose sick bay after his rescue. Royal Navy

Perhaps if the Arun had been stationed at a more western harbor, she might have been able to get to the area of worst trouble by dawn on Tuesday, but the more maneuverable, faster helicopters would still have been the major lifesaving arm of the massive, coordinated rescue effort, which eventually involved about four thousand people and cost £350,000 ($770,000)—almost 90 percent of it expended on aircraft and the remainder expended on surface vessels.

But while seventy-four people were saved by helicopters on August 14 (one-half the number saved by Culdrose-based helicopters in all of 1978), sixty-two survivors were directly recovered by various surface vessels. These craft included eight military vessels ranging in size from Royal Navy tugs to the frigates Overijssel and Broadsword, as well as six privately owned coasters and trawlers and three yachts competing in the race. Responding to flares or Maydays, or simply chancing upon life rafts, many of the commercial vessels rescued crews and either took the survivors ashore or left them with lifeboats and resumed their course. Several naval ships stayed on station or swept designated areas during the gale. At first, the Nimrod aircraft served as on-scene commander, but on Wednesday, HMS Broadsword, a new Royal Navy frigate, out on sea trials, took over that role.

A search and rescue crew Just off a Sea King helicopter on Tuesday. (Left to right) St. Fred Robertson, Lt. Charlie Thornton, Lt. Keith Thompson, and CPO Airman Dave Roles. These crews flew alternating missions, some staying in the air as long as four hours at a time. Royal Navy

Communications were a major problem. At first, the Southern Rescue Co-ordination Centre at Plymouth did not have a race entry list. The list eventually provided by the Royal Ocean Racing Club showed 336 entrants, even though the club’s officials believed that fewer than 310 boats had actually started the race. But which 310? Many boats that had officially withdrawn were seen sailing around the starting line; were they spectator boats or did they actually start? In any case, the start was so crowded that identification of actual racing boats was nearly impossible. To be safe, the searchers used the larger list, so they were actually looking for 33 boats that never started. Information about boats that were located was fed into a computer that had already been programmed to calculate the overall standings. During the three days of the search, the computer periodically spewed out long lists, which were distributed by automobile and helicopter to the various rescue centers at Land’s End, Culdrose, and Plymouth.

Of course, these lists were only as accurate as the data fed to the computer, and much of that data was misleading. Many boats had similar names: Golden Apple of the Sun and Silver Apple of the Moon; Imp and Impetuous; two boats named Pepsi and two others named Pinta. Some boats had racing numbers that differed only in one number or were identical but with different nationality prefix letters. If no sail was hoisted, no number was visible. These and other problems did not make the rescuers’ job any easier. Helicopter crews frequently wasted valuable time hovering over boats with indistinguishable names; airmen who dropped down to look for survivors returned to report that they had already inspected the boats. Yachtsmen’s radio transmissions often were wrong or misleading, and they sometimes did not provide information about courses and speed that was necessary for lifeboats and other vessels trying to intercept them. Calculated positions were not always accurate, either. Until systematic sweeps were established on Tuesday afternoon, the search and rescue crews on and above the water were dependent upon these transmissions for locating boats in distress. So it was that in many instances luck played a more important role than any other factor in finding yachts that had requested help.

The most significant cause of the confusion was that so many boats were in distress. With 303 boats taking so much punishment in an area of about twenty thousand square miles, the huge rescue effort—said to be the largest in British waters since the evacuation of Dunkirk—was greatly taxed.

Unlike the nearly invulnerable helicopters, the ships had to endure the same seas that were damaging the yachts. HMS Anglesey and HMS Broadsword had been designed specifically for rough weather, but HNLMS Overijssel, the Dutch frigate on permanent guardship duty for the race, was badly strained by the storm. After being refueled by a tug on Monday evening, she steamed north-west through the fleet as the storm swept in. Her assigned task was to stay within very high frequency radio range of the Admiral’s Cup boats (about forty miles in good weather), in order to take their position reports, and to radio those positions back to the mainland. There was considerable press interest in the progress of the boats in the Admiral’s Cup competition, for which the Fastnet was the last and most important race.

The Overijssel began to roll badly as the wind and sea increased, until at one frightening moment before dawn, a wave swept over her deck and into her engine room, where the water short-circuited the generators. Rolling to within a very few degrees of the angle of heel at which she would lose all stability and capsize, she lay in the dark for twelve minutes while her engineers worked to start the generators. The return of power was a mixed blessing for those people who, like Peter Webster, the RORC’s representative, stood by the radio, over which was transmitted a stream of grim news. At dawn, the Nimrod airplane flew over with its lights flashing. “Can you see a life raft?” somebody asked the Nimrod over the radio.

“We can see five life rafts,” the Nimrod answered.

The Overijssel, a Dutch destroyer, here seen from a Royal Navy helicopter, was the Fastnet race guard ship and rescued sailors despite dangerous rolling. A. W. Besley

A large breaker bears down on the Overijssel on Tuesday morning. At this time, force 10 to 12 conditions predominated, with winds gusting to over sixty knots and breaking seas that were occasionally thirty to forty feet in height. The Overijssel was rolling her gunwales under, and at one stage her engines shut down when the generators were flooded. Peter Webster

A dismasted, abandoned yacht on the gray wastes of broken water. Photographs tend to diminish the apparent height of the sea, especially when taken high up (as from the Overijssel’s bridge) but the breaking crests as far as the eye can see give a clue about the severity of the conditions. Peter Webster

“It was more and more pathetic as time went by,” Webster later remembered. “There were so many messages, and we could only deal with them one at a time.”

Working off the scrambling nets slung over the side, the Overijssel’s crew recovered fifteen survivors and two bodies. The survivors were from the abandoned yachts Trophy, Callirhoe III, and Polar Bear. The last-named, like Trophy, was capsized as she stood by another yacht in distress. A wave picked up the stern of the thirty-three-footer and threw it over the bow. Polar Bear surfaced from the violent pitchpoling with her mast broken, her cabin roof ripped open by the remains of the spar, three feet of water in the cabin, and a crew member, Brigid Moreton, with a dislocated shoulder.

The injured woman’s husband, Polar Bear’s skipper, Major John Moreton of the Queen’s Dragoon Guards, decided to abandon ship. He announced the decision over marine radio, and the crew fired off a flare and inflated and boarded the life raft. They drifted without major incident for an hour until the Overijssel appeared and, rolling wildly, slid down to them. When her leeward side dipped, they stepped off the raft onto the scrambling nets and climbed a few feet up to the lower deck. Mrs. Moreton’s arm was soon treated by a doctor picked up from another yacht.

The Dutch frigate stayed on station until the two bodies she had retrieved began to decompose badly. When she docked at Plymouth on Thursday morning, the quiet ceremony of removing the coffins from her deck gave authenticity to the disaster, about which landspeople had been hearing second- and third-hand for two days.

Among the more dreadful of those stories was that of a boat named Bucks Fizz, which was one of thirty-two non-Fastnet race entrants to send out distress calls heard by the coastguards. The only boat in a race for multihulls that paralleled the Fastnet race (which is open only to monohulls), Bucks Fizz was a thirty-eight-foot trimaran owned by Richard Pendred, who was vice-commodore of his sailing club near Rye. The light, fast three-hulled boat was seen by several Fastnet race crews during the first two days of racing, but she disappeared during the storm. At dawn on Wednesday, she was found floating upside down off the Irish coast, and two days later, an airman was dropped from a helicopter to inspect her. Nobody was aboard. Two bodies were found later and the remaining two crew members were presumed drowned. In her crew were a man and a woman who had met on the eve of the race’s start in a pub in Cowes, immediately formed an attachment, and decided that it would be fun to sail together in Bucks Fizz.

A few crews of yachts in the race took enormous risks in responding to flares and Mayday calls from other crews. Some rescuers were themselves put in distress and had to be rescued by the military. But three crews—two English and the other one French—were brave, skillful, and fortunate enough to reach their objectives and to save a total of nineteen people from three boats, two of which sank. By coincidence, the two English boats saved French crews and the French boat saved an English crew.

At fifty-five feet in length, Dasher was one of the largest boats representing the military in the race. Almost every branch of the British armed forces owns yachts for leadership training or simply to allow officers to enjoy the rigors of ocean racing, and more than a dozen Fastnet race entrants represented the army, the navy, and the air force. The skipper of Dasher, Lieutenant Bob Hall, Royal Navy, decided to run before the seas when the weather deteriorated. At 4:30 A.M., the helmsman notified Hall that he had heard a cry for help. He shone a bright light out into the seas and soon saw a dismasted yacht approximately thirty yards away. Under storm sails, Dasher sailed to the yacht, which Hall identified as Maligawa III, a French thirty-two-footer. She was dismasted, and the glass ports in her cabin sides were smashed and her running lights were off—indications that she had suffered considerable damage. Hall shouted to the Frenchmen that he intended to take them in tow. After two practice runs in which he made sure that each crew member knew his job, Hall steered Dasher close alongside the French boat and a line was passed to her crew. He then headed south-east, sailing slowly under storm sails alone, with Maligawa comfortably in tow. After forty minutes of uneventful sailing, a wave knocked Maligawa over on her side, throwing two of her crew overboard and flooding her with a considerable amount of water. Their shipmates hauled the two men in by their safety harness tethers. Hall decided that they were not safe, so he told the French crew to abandon ship. As their vessel started to settle deeper into the water by the stern, the six French sailors inflated their life raft, which they boarded and cut loose. The tow line was also cut, and Hall steered Dasher back toward the raft and, on his first try, came alongside and picked the men up without further incident. The Frenchmen were given hot drinks and dry clothes, and Lieutenant Hall assigned them to watches so they could help in sailing Dasher, a Camper and Nicholson 55 sloop, back to port. Maligawa III was later confirmed as having sunk.

Helicopters and ships located and recovered several bodies of crews who had died In the water. A. W. Besley photographs

At about the same time and in roughly the same part of the Western Approaches—about fifty miles southeast of Fastnet Rock—David Chatterton’s Moonstone (like Windswept an Offshore One-Design 34) was hove-to in the traditional way, with her small storm jib backed, or trimmed to windward, and the tiller lashed to leeward. She had twice been knocked down to ninety degrees. At dawn, Chatterton saw a life raft lying approximately six hundred yards to leeward. He turned on the engine, headed toward the raft, and made three attempts to get alongside, once falling off a wave with great force. Fearing a recurrence and the possibility of the boat rolling down to and over the raft, he hove-to just to windward and let a lifebuoy down to the raft on the end of a line. When the men in the raft had secured the line, Moonstone’s crew hauled them in. The six rescued men were from the French thirty-three-footer Alvena, which, they said, had been rolled over, dismasted, and, with her windows smashed in, had probably sunk. They had been in the life raft for several hours. It had capsized twice; they had righted it each time. Now loaded down with thirteen men, Moonstone sailed east and eventually put in at Falmouth. (Alvena was later recovered.)

Griffin, a sister ship of Moonstone and Windswept, was owned by the Royal Ocean Racing Club and commanded by an experienced Australian offshore sailor named Neil Graham, who taught sailing at Britain’s National Sailing Centre, in Cowes. In his crew were two of his fellow instructors and four students from the school. All were knowledgeable, well-trained sailors. After the wind increased to force 10, they stopped racing at about 1:30 Tuesday morning. Half an hour later, Stuart Quarrie, at the helm, saw a wave whose near-vertical face was twice the height of most of the other seas. The wave fell on Griffin, rolling her over with such violence that the curved snap hook on the end of Quarrie’s safety harness tether straightened entirely as he was thrown overboard. From five yards away, he could see Griffin’s keel sticking straight into the air, and her high-intensity man-overboard light blinking from under the hull in the water. Two men were trapped under the cockpit, and they soon unhooked their harnesses and swam out. The four others were inside the cabin, where, standing on the roof, they watched the water pour in the hatch. The washboards had dropped out and the hatchcover had slid forward, leaving a ten-square-foot hole that was several feet under water. After about half a minute, a wave broke against the keel and its weight slowly levered the hull upright. When she came up, the cabin was almost full of water and the deck was only three inches above the sea’s level. The crew immediately decided that there was only one thing to do. The life raft was inflated, a man dove into the cabin to retrieve flares and a knife, a flare was ignited, the seven men slid into the life raft, and the bow line was cut.

About forty-five minutes later, the life raft capsized, and as they pulled it back upright, the canopy broke off and the raft changed shape from circular to tubular. They fired off one flare and, when they saw a light, several more. The light approached and became a yacht sailing under a deeply reefed mainsail.

The yacht was Loreleï, a thirty-six-footer owned by Alain Catherineau, from Bordeaux, one of the fifty-five French skippers who had entered the race. Built to an older and more conservative design than some of the most recent, light boats, Lorelei was a Sparkman and Stephens-designed She 36 built in England, and a smaller sister of Toscana. Lorelei was about forty miles south-east of the Rock at 2:00 A.M., going very fast under triple-reefed mainsail and number-4 jib through a group of boats that had stopped racing and were lying a-hull, when Catherineau spotted a flare about half a mile to leeward. He went forward with two of his crew to douse the jib, and under reefed mainsail alone they headed in the general direction of the flare, which was the first of several. Catherineau told the helmsman, Thierry Rannou, to steer about thirty degrees to one side of the flares, which appeared like a red halo over the waves, because he was not sure what type of craft had fired them off. Six hours earlier they had sailed near a fairly large French trawler; Catherineau thought that this might be the vessel in distress and, fearing collision, he did not want to get too close to her too quickly. Lorelei was rolling considerably, and the safety harnesses frequently offered the only support for the crew on deck. Soon the crew could make out two small lights on top of a black shape about fifty yards away: it was a life raft. They steered for the life raft and passed about ten feet to windward of it at a speed of three knots. One of the Frenchmen threw a line, but it did not reach the raft. Two of the men in the raft tried to reach the yacht, fell overboard, and were hauled back into the raft by their shipmates.

Catherineau then took the tiller because, as he later wrote in a description of the rescue, “I felt that we could recover those men, and to do that I had to take the helm of my boat and get in touch with her. I knew her well and could ask the impossible of her.” He surprised Rannou by starting the engine and ordering the mainsail dropped. Rannou said that the engine could never drive Lorelei fast enough into the seas, and after the skipper made several futile attempts to get close to the raft, he seemed to be right. Realizing that he could not develop enough speed to steer Lorelei upwind, Catherineau changed tactics and instead of heading into the waves he steered parallel to them, with the wind and his unusually powerful engine pushing the sloop at five knots. About thirty yards from the raft, when he was sure that he was on the correct heading, he put the engine into reverse and the boat slowed to a stop one yard to windward of it. Two of his crew threw lines to the raft, and the men started to come aboard. Some of the men went below, but the French skipper asked the strongest of them to remain on deck to help.

The last man out of the raft was extremely weak. All he had on his upper body was a T-shirt and his safety harness, and exposure obviously had sapped his strength. He was unable even to hold his head out of the water. The French sailors hauled him on deck inch by inch every time Lorelei heeled (at one stage during the rescue, she was knocked down so far that the wind vane at the top of the mast was washed away). One difficulty was that, despite his hypothermia, the man refused to let go of the handholds in the life raft; his shipmates had insisted that he hold on to them, and now his hands were so tightly clenched around them that the rescuers had to pry his fingers away. They finally were able to drag him on deck and below and, to the surprise of many, he survived. It was 4:00 A.M. The Englishmen had been in the water for almost two hours, and the rescue had taken over an hour. One of the rescued sailors came on deck to thank Catherineau, shaking his hand vigorously. Exuberant at the success of their rescue mission, the French skipper and his second in command, Rannou, exchanged an emotional embrace. Not until Stuart Quarrie told the story of Griffin’s swamping and certain foundering did Catherineau realize that he had rescued not fishermen but fellow yachtsmen.

With thirteen exhausted, wet, and in some cases seasick men on board, the French sloop was uncomfortable. The demoralized Englishmen were not the happiest of shipmates as Lorelei lay a-hull for much of Tuesday. When the wind started to die, Catherineau put up sail, and on Wednesday morning—some thirty hours after the rescue—she was running under spinnaker before a warm light breeze under an almost cloudless sky. Catherineau spent an hour below cleaning up the damp cabin, and then two of his crew followed him down to prepare a meal not usually served aboard racing sailboats, even by the French: Salade de Tomates Bordelaises, Poulet Gersois, Sauté de Veau aux Carottes, fruit, cheese, dessert, and a Médoc. Cheered by the spectacular lunch, the Englishmen finally relaxed. Lorelei docked at Plymouth late Wednesday night. The Englishmen found beds ashore, and the next day they borrowed money, bought wine and cigarettes, and returned to the French sloop to celebrate their rescue with Alain Catherineau and his crew.

Thanks to the courage and exemplary seamanship of other yachtsmen, the nineteen men of Maligawa III, Alvena, and Griffin joined the many other sailors rescued by helicopters and ships on the list of those saved during the gale. Besides Maligawa III and Griffin, three other boats sank after being abandoned. A French trawler, the Massingy, took seven men directly off the English yacht Charioteer, which went down soon after. During a capsize, Charioteers owner, Dr. J. Coldrey, had been hit on the head by the galley stove, which had come off its mountings, suffering a seven-inch cut in the scalp and a fractured cervical vertebra. Hestrul II sank after her six men were taken off by a helicopter. And Magic sank while under tow after her crew was rescued by a helicopter.

The remaining nineteen abandoned yachts were later recovered and safely towed to port by Royal Navy tugs, lifeboats, and commercial vessels. Only some of the latter claimed salvage. Claiming salvage on abandoned vessels is as legal and as encouraged now as it was a century ago, although the opportunities are fewer. Owners are happy to get their boats back, and insurance companies are always more than content to settle with the salvager for a fraction of the boat’s worth rather than cover the loss of the vessel. “People think the fishermen are like vultures or scavengers,” a spokesman for Lloyd’s Shipping told a reporter, “but really it is an accepted procedure at sea. We would be surprised if the fishermen didn’t go all out for the salvage money.”

When a Cornish seaman named Bert Smidt heard that abandoned yachts were adrift in the Western Approaches, he and several crew members took his coaster, Pirola, out into the last of the gale. They found the abandoned Polar Bear, and a man went aboard the thirty-three-footer with a towline. Soon after, The Pirola came across the empty thirty-four-foot Allamanda, the procedure was repeated, and the tow headed toward Penzance. The two yachts probably were worth £60,000 ($132,000). Since he could expect the insurance companies to cover at least one-third of the cost of the boats in salvage payments, Smidt had good reason to think the trip well worth the time and risk.

But the risk increased rapidly as a second, though less violent, gale blew in on Thursday. With the two yachts tossing wildly and threatening to capsize at the end of of the towlines, Smidt ordered Allamanda cut loose. The man aboard rode out the storm for over ten hours before the Pirola returned to retrieve her as the gale died. Three days after heading out, the coaster pulled into Penzance with the two yachts. “It’s an accepted part of making your living at sea,” a relieved Smidt told a reporter from the Western Morning News. “It was dangerous, and at times I was worried about my men. I certainly didn’t want to lose any of them, money or no money.”

Meanwhile, a strange drama involving salvage was being played out in Milford Haven, Wales. Camargue, which had been abandoned by her crew as they leapt, one by one, into the water to be retrieved by a helicopter, was taken in tow on Wednesday morning by a French trawler, the Locarec. That afternoon, the tow pulled into the estuary of Milford Haven only to be intercepted by an English yacht, Animal, whose crew had relaxed after their own ordeal and now concluded that the trawler was engaged in a criminal act. The Englishmen cut the towline, put their own line aboard the yacht, and towed Camargue up the estuary. The French claimed salvage; the local Receiver of Wrecks, a government official, reclaimed Camargue; and the Department of Trade, which has jurisdiction over salvage, said that the act of piracy in reverse was unprecedented and that it did not know what course of action to follow. As was the case with most of the rescues conducted during the Fastnet gale, the story had a satisfactory ending: the French fishermen received some compensation for their time and efforts and the owner retrieved his boat.