The kiss wasn’t the terrible, terrible thing that happened, but it’s relevant because it makes the terrible, terrible thing even more terrible. It happened at the rehearsal.

Caramella and I were late, on account of our sleuthing activities. Kite and Oscar were already there. Oscar was lying flat on his back on Kite’s garage floor, and he was singing.

I am the walrus koo koo kchoo, koo koo koo kchoo.

But he’s not a walrus; he’s just a very tall guy with an acquired brain injury. Before he acquired the injury to his brain, you would have been likely to see him lying on his back singing koo koo kchoo because he’s naturally berserk in an artistic way. His brain injury just makes him slope when he is standing and walking, and when he talks the words come out slower. But apart from that he’s still got the same Oscar soul – it’s just harder for him to crank it out. It’s as if all the hard drive is still there but the keyboard doesn’t work as well, so if you press Control you might not get control. Oscar gave his brain an almighty whack by falling off the Hills Hoist in his backyard while practising acrobatics, so, if nothing else, take this piece of handy advice from a reckless daredevil like me:

Don’t hang upside-down on the Hills Hoist. Also, don’t try anything tricky or dangerous like a back flip without someone helping you. There are things you can do with a Hills Hoist (like hang your old teddy bear on it and then spin it around and take a photo of the bear in motion) that are still fun and tickle your brain instead of threatening it.

Anyway, Kite wasn’t warming up; he was just sitting with his back against the wall. Kite wears his body in a comfortable, lazy way, so his smile takes ages and ages to happen. He smiled at me then and the smile seemed to frisbee right over towards me in slow motion, and I didn’t have to move; it came right towards me and then it got me.

I loved being got by it.

‘Oscar’s serenading us,’ he said.

Oscar lifted his head slowly as if it was as heavy and awkward as a bowling ball.

‘Oh, you two have arrived. Did you notice the grass?’

‘No.’

‘No, neither did I. There isn’t any.’ His head clunked back to the ground.

I smiled. Caramella and I took off our shoes.

‘There could, however, have been grass and there could have been a duck on the grass and it could have had a straw in its mouth and it could have been trumpeting a song that we all recognised. It could have been singing “I am the Walrus”. But unfortunately this wasn’t the way it was. There was no grass.’

Caramella said, ‘And no duck.’

So far everything was just as it always was; nothing to suggest that something terrible was about to happen. I was swinging my arms around like an excited maypole, Oscar was giving forth on the possibility of ducks, Caramella was still taking her shoes off and Kite was standing up just as if he was about to warm up.

‘Where’s Ruben?’ said Caramella.

‘He can’t come today,’ said Kite.

My arms stopped flapping and fell to my sides. This was the first tremor.

Ruben is Kite’s dad and he is also our trainer and our director. He’s absolutely perfect for the job. So it was impossible to imagine how we would manage a training session without him. I looked at Kite. He looked at me. And then I knew something had happened. I knew it by the look that went between us, a look that seemed to thud out of his heart and drop to the floor.

‘Why can’t he come?’ I said and I squatted down to steady myself.

‘He’s in Albury.’

‘Albury?’ said Caramella. ‘You mean Albury-Wodonga? I’ve been there. It’s miles away, halfway to Sydney. There are two towns, one on one side of the river and one on the other. So one is in New South Wales and the other is in Victoria. How’s that! We’ve got cousins there. They’ve got a café. They make meatballs.’

Obviously, Caramella hadn’t yet sensed what I had sensed. She was prattling on as if it was normal for Ruben to be in Albury. Albury-Wodonga.

‘Why’s Ruben in Albury?’ I dropped into chief sleuth mode.

‘That’s an invigorating place to go,’ Oscar bellowed out from his position on the floor.

‘Invigorating?’ I said, scrunching my nose. ‘I bet it’s not. I bet it’s full of shops selling frocks and car tyres and meatballs and tea towels with native flowers…’ I was being a snob about Albury because already I was mad at the town for taking Ruben away from our rehearsal, and I was getting mighty nervous.‘Why is he there?’

Kite was rubbing his neck. Seemed to me he was feeling a bit nervous too.

‘He’s looking at a house. We’re going to live there.’

There it was. He said it. Without even a note of warning. Without even taking the moment in his arms and offering it slowly, tenderly, with some due respect for the momentous blow it could inflict. He just shot the words out his mouth, as if he was spitting out some crumb that had got stuck in a tooth. I had to look at the floor. I saw my feet and they looked like they were going pink, as if the blood was rushing downwards.

‘Why are you going to live in Albury?’ said Caramella, quietly. She looked up meekly from her sneakers.

Kite kicked at the floor. ‘Dad’s been offered the job of Artistic Director for the Flying Fruit Fly Circus. You know that one, the professional one. They do shows all round the world. It’s a dream job for Dad.’

‘But what about you?’ I said, looking directly into his eyes.

He took a deep breath in and glanced up at me. ‘Cedar, I’m going to join the Flying Fruit Flies. I’ll train with them.’

‘Oh.’ I nodded. Everything felt bad. Now even my face was reddening. I was afraid all my feelings were on show, blazing in my cheeks.

‘I have to. What else will I do up there?’ Kite shrugged, as if this was all a breezy kind of a thing that had happened. As if it was no big deal. ‘You know this wasn’t planned. Someone saw our show at the community centre and that was how the offer came through. Dad is very sorry to have to leave our circus here but this is a real opportunity for him, and the contract is only for a year initially so we’ll probably be back.’

‘You won’t be,’ said Oscar. ‘You’ll become a pro. Why would you want to come back here? You’ll be in Paris and you’ll be flying and…’

He stopped. He had lurched up to sitting, leaning on one arm in a precarious startled way, but then he lay down again and looked up at the ceiling without speaking. For a while no one said anything. I was staring at my red feet. I could hear two people walking by outside and saying things that two people walking together would be likely to say. One said, ‘It was that house, I tell you.’ And then the other said, ‘No it wasn’t, it wasn’t that house. I should bloody know…’ And then I heard Kite saying something. So I had to stop listening to the outside, which was what I preferred to be hearing.

‘I’m sorry, guys. In the end it wasn’t up to me. I couldn’t have said no to Dad.’

‘You’ll have a good time there, Kite,’ said Caramella, so sweetly that I nearly glared at her. Oh why was she being so nice to him, when suddenly I didn’t like him at all? How could he go and leave now? Just when we had everything established. Didn’t he care? What did he think we were going to do?

I stood up. I was so annoyed I had to stand. I had to do something.

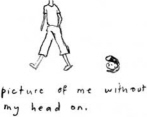

‘Well, I guess that’s the end of The Acrobrats,’ I said, brushing myself down as if I’d got creased from sitting there. I was really brushing away the last crumbs of the circus, our circus. Now it was me who was acting like it wasn’t a big deal, like oh–well-that’s-that, there we go, now who’d like a walk in the park? If Kite didn’t care then I wouldn’t either. No way was I going to let this get me. I wanted to walk out of there in one composed piece, gracefully, head held high as high. And then once I was out, I planned on utterly letting my head drop off: smash, kaput, shattering sounds, the whole thing. But you can’t do that in a garage, especially when it might betray the size of certain feelings you need to keep small.

I started walking towards the door.

‘Hey, Cedar, are you going?’ said Kite. He was walking towards me.

‘Yeah. I’m going.’ I kept backing out. Kite came close and grabbed my hand for an instant, then he let it drop.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said.