Mrs. Harden nearly died today.

I know because I was there.

I saw her slumped

on her kitchen floor

looking white as an egg.

I wasn’t there

from the beginning, though.

Only from the time

my little brother, Parker,

went missing.

It seems Parker wanted to

drive somewhere

on his new trike.

He’s only allowed to go

one house up

each way.

And only if he tells someone

where he’s going.

He obeyed the first rule.

(Mrs. Harden lives next door.)

But he forgot the second rule.

He told no one.

He drove to Mrs. Harden’s.

He parked in her driveway.

He knocked at her back door.

She invited him in

for a cookie.

That’s how it started.

Before Mrs. Harden

could reach the cookie jar,

she had what grown-ups call

“a spell.”

Parker saw her collapse.

He remembered his safety lessons.

He climbed on a chair.

He reached for the phone.

He dialed 911.

This is where I come in.

I find him

shouting to the dispatcher:

“Emergency! Emergency!”

I’m here because

Mrs. Harden and I

are supposed to paint posters

for her women’s club bake sale.

Paints and rags and poster board

are sitting on her craft table.

Mrs. Harden and I do lots of

projects together.

She is sort of an honorary

grandmother to me.

(My real ones live across the country.)

I crouch on the floor

next to her.

I take her hand.

It’s cold and clammy.

I pat it.

“It’s me. Suzy,” I tell her.

“Don’t worry, Mrs. Harden. Help is on the way.”

The ambulance comes.

The EMTs wheel Mrs. Harden

off on a stretcher.

Now Dad is in the driveway

asking what happened.

Neighbors mill around

shaking their heads,

whispering.

Mrs. Capra pats Parker

on the head.

“So you’re the little hero.”

Dad calls Mrs. Harden’s nephew, Paul.

Mrs. Harden is a widow. No children.

A couple years ago she gave us

Paul’s phone number “just in case.”

Paul says for us to lock up

his aunt’s house.

He asks us to hold her mail,

take in her newspapers,

keep an eye on things

until he finds out

what’s what.

Back home,

Parker is all monkey-faced

(which is what he calls

being upset).

I give him a hug.

“Don’t worry,” I tell him.

“Mrs. Harden will be okay.

She’s in good hands now.”

(I don’t tell him

how worried I am.)

Parker sniffles.

“Yes, but Mrs. Capra

called me a little hero.

I’m not little, Suzy.

I’m four and a half.

I’m a big hero.”

Parker pumps

his (little) fist in the air.

“I’m Hero Boy!”

Wait till Mom finds out.

She likes Mrs. Harden

almost as much as I do.

Mom’s in Arizona right now,

taking care of Grandma Fludd,

who recently had a bad fall.

Gee—two people I know

in the hospital.

My best friend, Alison,

says bad things come

in threes.

Uh-oh, I think.

What’s next?

Dad puts Mom on speakerphone

so Parker and I can hear too.

She says she hopes Mrs. Harden

will be okay.

She says she is proud of

her “big boy”

for dialing 911.

She says: “Thank you, Suzy Q,

for helping out with things.”

(“Things” is code

for Parker.)

She says she is trying to convince

Grandma Fludd to move

to Pennsylvania.

Up pipes Grandma Fludd:

“What? And freeze my patootie off

in the winter? Forget it!”

Parker howls,

wiggles his little behind.

“Patootie! Patootie!

Watch me shake my bootie!”

There’s a voice mail from Alison.

She sounds all breathless:

“Sooze, I heard about Mrs. Harden.

The whole town is talking.

I hope she’s not dead.

Is she?

Is she?

Call me!

Right away!”

I call Alison.

“Tell me—quick!” she says.

I tell her: “We got a message

from Mrs. Harden’s nephew.

She’s going to be okay.”

“Whew! What a relief,”

says Alison.

“Just imagine if she died.

You’d be neighbors

with a dead person!”

I was in second grade

when Herbie Sizemore

pushed me up against

the playground fence.

“Say it!” he ordered.

“It” was a bad word.

A very bad word.

The very, very worst.

“No,” I told him.

I tried to push past him.

He wouldn’t let me.

Suddenly a girl appeared,

bracelets jangling.

She stared Herbie

right in the nose.

“Let her go,” she snarled.

I was surprised.

She was in the other

second-grade class.

We never played together.

Herbie growled: “This is

nunna your beeswax.”

“I’m making it my beeswax,”

said the girl.

She pulled a sparkly pink phone

from her pocket.

“I have the state police

on speed dial.”

“Yeah, right,” said Herbie.

The girl punched a button.

Herbie backed off.

When he was gone,

I said: “That’s a toy phone,

isn’t it?”

The girl wagged her finger.

“Nunna your beeswax.”

I laughed. “You rescued me.”

“I’m Alison Wilmire,” she said.

“I’m Suzy Quinn,” I said.

We shook hands.

We’ve been best friends

ever since.

Which is pretty amazing

since we’re so different.

Alison is curly blond wonder-hair.

I’m mousy brown ponytail.

She’s pink sandals and short skirts.

I’m red Phillies cap and jeans.

She’s hip-hop dance lessons.

I’m “Go, Phillies!”

She collects bracelets.

I collect rocks.

She wants to be an actress when she grows up.

I don’t have a clue.

Dad says Alison and I

are a perfect example of

the old saying

“Opposites attract.”

Mom says

while Alison and I

may be different

on the outside,

we are a lot alike

on the inside

where it counts most.

“You both have heart,”

Mom says.

“That’s the best thing

I can say about

a person.”

When Mom first went to Arizona,

Parker got all stubborn

about bedtime.

Dad and I tried extra bedtime stories.

Extra snacks.

New stuffed animals.

Old stuffed animals.

Blue night-light.

Glow-in-the-dark stickers.

Nothing worked—

until I came up with

Tickle Monster.

I started creeping

into Parker’s bedroom

step by step,

waving Mom’s feather duster.

“Here comes Tickle Monster,”

I’d say.

I only had to tickle Parker’s big toe

before he would giggle and beg:

“Stop! Stop, Tickle Monster!

I’ll sleep now!”

But this night

when I creep into his room,

he’s all curled up

with his stuffed owl,

snoring like

a little eggbeater.

I guess it’s exhausting

being a hero.

I’m tired too.

I get into my nightie.

I open my window wide.

There’s a cool June breeze blowing.

It feels like it might rain.

I tell Ottilie—my goldfish—about

the day’s excitement:

“Mrs. Harden nearly died today.

But Parker called 911.

And now she’s going to be fine.

And the Phillies beat the Pirates—

even though I missed watching

the whole game on TV.

And we talked to Mom and Grandma Fludd.”

Ottilie swims closer

to the glass in front of her tank.

Her tiny fish mouth sends me kisses.

I think she enjoys our nighttime chats.

Alison says

Ottilie is just a goldfish

and goldfish don’t know anything.

But I read about goldfish

before I got Ottilie.

Goldfish can recognize their owners.

They react to light and different colors.

I trained Ottilie to eat fish flakes

from my fingers.

Ottilie knows plenty.

Dad—who teaches history

at Ridgley Community College—

told me that in 1939

a fad was started by

a Harvard University student

who swallowed a live goldfish.

The fad spread to other colleges.

Eventually, Dad said,

the president of Boston’s Animal League

decreed that goldfish swallowers

should be—would be—

arrested

if they didn’t stop this behavior.

My sentiments exactly.

Ottilie’s too!

This morning Gilbert Lenhardt stops by.

He heard about Mrs. Harden.

He was supposed to weed her herb garden

and pull out a dead holly bush.

He is wondering if he should go ahead.

Dad tells him yes.

Gilbert does a lot of odd jobs around the neighborhood.

He’s thirteen. Not old enough to get a

regular job.

According to Alison, Gilbert really needs the money.

His dad drinks a lot and probably spends

his money on beer instead of his family.

For a kid with a father like that, Gilbert is always

cheery. Always whistling.

You can hear him a block away.

Dad says they are songs from the 1940s.

Odd—but nice too.

One thing I’ve learned from Dad is

to appreciate ancient history.

Ten minutes later,

there’s a knock at the door.

“Hi,” says a lady in a gray suit.

“I’m Marsha Levine, reporter for

the Ridgley Post.“

She introduces the man next to her—

“And this is Joe Perchek, photographer.

We’re here to see the little boy

who called 911 yesterday.

The little hero.”

Dad says it’s okay

for them to talk to Parker

for a few minutes.

And to take a couple

pictures for the paper.

Parker says: “Wait!”

He runs upstairs,

comes back wearing

his Superman T-shirt

and his Count Dracula cape

from last Halloween.

He poses—arms out

like he’s flying.

Ms. Levine tweaks his cheek.

“You’re the cutest little boy ever.”

Parker squawks: “Don’t call me little!”

I head over to Alison’s.

I pass Mrs. Bagwell’s.

Mrs. Bagwell is chasing after something

with her big green flyswatter.

Mrs. Bagwell is always after something—

kids trying to retrieve balls from her yard,

beetles nibbling her roses,

the Kims’ gray cat, Shady.

This time it’s a crow.

I wave. “Good morning, Mrs. Bagwell.”

“Dang crow,” she growls.

When I get to Alison’s,

she is still getting dressed.

She dangles two bracelets under my nose.

“Which one, Sooze—garnet or charm?”

I groan. “Who cares? We’re just going

to the library.”

She rolls her eyes at me. “I repeat—garnet or charm?”

I point to the garnet bracelet.

She scowls. “You’re only saying that because it’s red.

Like the Phillies.”

She flips both bracelets into her jewelry box.

She pulls out a purple beaded one

that matches her nails.

I coaxed Alison into

signing up with me for

Tween Time at the Ridgley Library.

Every Tuesday morning at eleven.

She fought it.

She said she reads enough

during the school year.

I told her: “Tween Time isn’t

just about reading.

It’s crafts too. And games. And field trips.”

Anyway—what’s wrong with reading?

I happen to love it.

It’s in my DNA.

I get it from my mom,

who is totally addicted to books.

Nobody—

I mean nobody—

loves books

more than Mom.

She breathes books—literally.

She holds them up to her nose,

takes deep whiffs.

“Each book has a scent

all its own,” she says.

“Ink, tree bark, a hint of thyme,

summer-dust.”

Dad pipes up: “Mold!”

He’s remembering when Mom

bought six cartons of books

from someone’s half-flooded basement.

Mom sleeps books.

She keeps one under her pillow.

I’m not kidding.

She got into the habit

when she was a kid.

She used to wake up at night

and read by moonlight.

I won’t be shocked

if one morning

I come down to breakfast

and find Mom

in one of her fogs,

eating a page of a book

with a dollop of strawberry jam.

We tweens, ages ten to twelve,

meet in the Bennett Room

of the Ridgley Library.

One of the librarians—Ms. Mott—

stands in the doorway.

She’s wearing a black bonnet

and a fringed blue shawl.

She’s twirling a parasol

(which is an umbrella for sun).

“Welcome, tweens,” she says,

chirpy as a bird.

Alison gives me a dark look.

“Give it a chance,” I whisper.

There are three other

kids in the room.

Two girls and a boy.

Alison and I don’t know them.

Ms. Mott sighs.

She looks at her watch.

Sighs again.

I think she was hoping for

a bigger crowd.

Finally she closes her parasol.

She smiles

and makes an announcement:

“The theme for Tween Time

this summer is

everyday life in the 1800s.”

Alison slumps in her seat,

hisses at me:

“I hate history!”

“Any questions?” asks Ms. Mott.

No one raises a hand.

I feel bad for her.

So I raise my hand.

“Yes, Suzy?”

“Was there baseball back then?”

Ms. Mott brightens. “Indeed there was.

But the field was smaller.

And players didn’t wear gloves.

And batters were called strikers.

And runs were called aces.”

The boy raises his hand.

“Were there cars?”

“Yes,” says Ms. Mott.

“As a matter of fact, in 1895

there was a total of four cars

in the entire country.”

“Holy cow!” says the boy.

The girl in green asks,

“What did kids do for fun?”

“Simple things,” says Ms. Mott.

“Roller-skating, kite flying,

sledding, checkers, kickball,

hoop rolling.”

“What’s hoop rolling?” asks

the girl with the pigtails.

“You’ll see,” says Ms. Mott.

“We’ll be trying some of these things

in the weeks to come.”

Alison mutters under her breath:

“Whoop-dee-doo.”

By the time we are dismissed,

we’ve learned quite a bit

about the 1800s.

We know that—according to

stagecoach etiquette—

it was considered bad manners

to point out where horrible murders

had been committed.

We know that

some people in the 1800s

made toothpaste out of

honey and pulverized charcoal.

And that tomatoes were

thought to be poisonous.

And that “some pumpkins”

meant “impressive”

or “very good at.”

As we left, Ms. Mott chirped:

“When it comes to paying attention,

you kids are some pumpkins.”

Alison grabs my arm.

“Let’s skedaddle,” she says—

which in 1800s talk means

“Let’s get the heck out of here!”

Dad makes grilled cheese for lunch.

I tell him about the Tween Time theme.

Of course he’s pleased.

He waves his sandwich at me.

He says what I’ve heard

a hundred times before:

“History is life. Its purpose is a better world.”

“I know, Dad,” I say.

Parker pipes up: “I know something too!”

“What?”

“Mrs. Bagwell got robbed!”

“You missed it, Suzy,” says Parker.

“Cops came and everything.”

“Only one police officer,” says Dad.

“Seems Mrs. Bagwell wanted to report

a stolen ring.”

“There’s robbers in town!” says Parker.

“We don’t know that,” says Dad.

I get to thinking about

bad things happening in threes.

Grandma Fludd falls.

Mrs. Harden has a spell.

And now

Mrs. Bagwell is a crime victim.

Maybe Alison was right.

After lunch, I get on my bike.

Alison gave hers away last year.

“Bikes are for babies,” she told me

at the time.

“Tell that to Mr. Capra,” I said.

“He rides his bike to work every day.”

She ran her nose up the flagpole.

“Okay—babies and old people.”

It’s a bright afternoon.

I ride my bike

into the warm breeze,

away from the house,

along the bike path.

Trees ripple green.

The light is golden.

The sky is blue.

And I am a bird

flying …

flying …

Alison doesn’t know

what she’s missing.

I get back in time

to keep an eye on Parker

while Dad grades papers.

I set up Candy Land,

Parker’s favorite board game.

Parker keeps talking about

Mrs. Bagwell’s stolen ring.

Then he asks:

“Do robbers smoke?”

“What do you care?” I say.

“Just answer.”

“I guess some do.”

“Well, if we get a robber,

I hope he smokes.”

“How come?”

“So he’ll set off the smoke alarm.”

Parker is famous.

His photo—in his Superman shirt

and Count Dracula cape—

is on the front page of

the Ridgley Post.

The headline reads

LITTLE HERO DIALS 911.

Parker asks me to read it to him.

“Big Hero Dials 911,”

I say.

By late afternoon,

our living room is filled with

balloons,

cookie bouquets,

stuffed animals,

and flower arrangements.

All for Parker,

who is becoming

more obnoxious by the minute.

“Stay away from my balloons!”

“Don’t touch my cookies!”

“Hands off my animals!”

“Don’t smell my flowers!”

Little hero?

How about little monster?

The phone doesn’t stop ringing.

Mom calls.

She tells Dad to pop a copy

of the Ridgley Post in the mail

care of Grandma Fludd—

“Today!”

Mrs. Capra calls

to say she saw the article.

“Isn’t it just wonderful!”

Alison calls.

“How does it feel?”

she asks.

“How does what feel?”

I say.

“Your brother’s a hero.”

“Yeah—hero brat.”

The mayor’s secretary calls.

She tells Dad:

“Mayor Paloma would like

your son to ride in her car

in the Fourth of July parade.”

I tell Dad: “I’m going

over to the creek

to look for rocks.”

No phones at the creek.

The creek isn’t far.

I leave my bike home

and walk.

I carry an old toy beach pail.

I’m fussier about my rocks

than I used to be.

I know I won’t fill the pail.

I’ll be happy if I find

just one special rock.

I’m ankle-deep in water

when I finally see one.

Smooth. Speckled green.

Like the egg of a rare bird.

I can feel myself smiling

as I pick it up.

Sometimes I put one of my rocks

in Ottilie’s tank.

Some rocks I let Parker borrow

for when he plays with

his plastic cowboys.

Not this one.

This is one of the all-time

beauties.

This baby is all mine.

“Did you find one?”

I turn. It’s Alison.

“Your dad told me

you were here.”

“Look,” I say, all excited.

I show her the green speckled rock.

She ignores it. “Did you

hear the news?” she asks.

“Do you see my gorgeous rock?”

I ask.

Alison gives me a look.

“It’s a rock,” she says.

I give up.

“Yes, I heard the news.

Parker’s invited

to ride in the mayor’s car

in the Fourth of July parade.”

“Wow!” Alison squeals.

“That’s really something. But

it’s not the news

I’m talking about.”

There seems to be

a rumor going around

that Gilbert

is the one

who robbed Mrs. Bagwell,

took her ring.

Mrs. Bagwell says

she’s 95 percent certain of it.

Dad says Mrs. Bagwell

shouldn’t be accusing Gilbert

without proof.

Just because

Gilbert moved some boxes

from Mrs. Bagwell’s attic

and had to pass by

her bedroom

where she keeps her jewelry

doesn’t mean he took her ring.

“No more than I took it,”

says Dad, “when I fixed

her ceiling fan.”

Mrs. Harden is being discharged

from the hospital tomorrow.

I’m making a Welcome Home card

for her.

Parker wants to make one too.

He comes into my room

with his can of broken crayons

in one hand

and a fistful of cookies

in the other.

He’s still wearing

his hero outfit.

(He even sleeps in it.)

“Can you help me, Suzy?”

I give him a look. “Can you be nice?”

“I can be nice,” he says.

He holds out his fist.

“Here. Take a cookie.”

Mrs. Harden is home and

looking tired.

Her nephew, Paul,

has an important meeting today.

He asks if I will stay

with his aunt

for a couple hours—

“just to make sure

there are no problems.”

“Sure,” I tell him.

And it’s a good thing

I’m there,

because as soon as Mrs. Harden

goes up to her room

to take a nap,

the doorbell starts ringing.

It’s the mailman

with a package.

It’s the florist

with a dozen roses.

It’s Mrs. Capra

with a bowl of stewed plums.

And then Mrs. Kim

with cookies.

Last, it’s Mrs. Bagwell

with one of those

rotisserie chickens

from the supermarket.

I don’t like how

Mrs. Bagwell is blaming

Gilbert

for stealing her ring

when she has no proof.

I act polite, though.

I tell her Mrs. Harden

is resting.

I thank her for the chicken.

I feel like throwing the chicken

into the garbage.

But I don’t.

The chicken didn’t

accuse Gilbert.

Mrs. Harden is up from her nap

when the doorbell rings again.

It’s Gilbert.

He’s carrying a big planter of mint.

“Keep it in the pot,” he says,

sounding like a garden pro.

“If you plant it in the ground,

it will take over.”

Mrs. Harden smiles.

“I’ll set it on the patio tomorrow,”

she says. “For now, put it on

the coffee table

so I can smell it.”

I’m careful not to mention

Mrs. Bagwell’s accusation.

For a while I think Gilbert

is doing okay until I realize

I didn’t hear him whistling

up the walk.

I walk out with Gilbert

to the end of the driveway.

I want to say something

that will cheer him up.

“So, Gilbert. Want to do something?”

“Sure. But you’re busy now.”

“Right—so … someday?”

“Okay. Good. Someday.

Do what?”

“Right. What?”

“Well?”

“Want to collect rocks with me?”

Gilbert frowns.

“Scratch rock collecting,” I say.

“No offense,” he says. “I’m just

not into rocks.”

“I understand,” I say. “So … let’s think.

What do we both like?”

“How about food?” he says.

“Food—” I say. “Can’t go wrong

with that.”

“Ice cream,” he says.

I give him a high five. “Ice cream!”

“Someday,” he says.

“Someday,” I say. I head back

to Mrs. Harden.

Suddenly I turn and call to Gilbert:

“My treat!”

Gilbert gives a fist pump.

“Yes!”

Mom is coming home!

On Saturday.

Grandma Fludd is much stronger.

And she has lots of friends

at Sunshine Terrace

if she needs anything.

I didn’t realize how much

I missed Mom

until I burst into tears

when Dad told me.

It takes a lot of convincing,

but finally I get Parker

to accept the fact

that he can be a hero

without the Superman shirt.

I tell him it’s starting to stink.

I tell him the bad guys

will smell him coming.

He lets me pull the shirt off.

He puts on the Phillies shirt

I got him last Christmas.

I can’t talk him out of

the cape.

Alison stops by.

I tell her I’m going to Bean’s Books.

“Mom is flying home on Saturday.

I want to get her a gift card.”

Alison says she’ll come along.

On the way

Alison brings up Gilbert

and Mrs. Bagwell’s ring.

I tell her: “I don’t want to talk about it.”

“Why not?”

“It’s gossip and Gilbert is a friend.”

Alison raises an eyebrow. “Aha!”

“A friend.“

“A boyfriend,” she squeals. “Wooo-hoooo.”

I poke her. “Back off. He’s just a friend.

Who happens to be a boy.”

“Well, anyway,” says Alison. “My cousin Tara

says he probably did it.

Where there’s smoke, there’s fire.”

“That’s it,” I say. “I’m not going to

talk about it.”

Alison clamps her lips together. “Fine,” she says.

“Fine,” I say.

One thing about Alison—

she doesn’t stay in the same mood

for long.

By the time we get to Bean’s,

she’s back to being chatty.

“So,” she says, “what do you want

for your birthday?”

“Well, there’s no point asking for

my own phone or computer,” I say.

“Dad already told me. Not till I’m thirteen.”

Alison’s parents have told her the same thing.

She rolls her eyes. “Parents!”

My birthday is July 15.

I’ll be twelve.

I’ve been calling myself twelve

since school let out.

Mom says not to wish my childhood away.

But I don’t think of myself

as a child.

Parker is a child. I’m a kid.

There’s a difference.

I’ve already told my parents

what I want for my twelfth birthday.

I want to go to a Phillies game.

Citizens Bank Park—

home to the Philadelphia Phillies—

is a two-and-a-half-hour drive

from Ridgley.

Going to a game

means staying over

at a hotel in the city.

So it would be

an expensive

birthday present.

But hey—it’s the big one-two.

A person turns twelve

only once.

I tell Ottilie:

“Mrs. Harden is out of the hospital.”

Ottilie flicks her tail fin.

I think it’s her way of smiling.

“And Mom is coming home.

And I forgot to tell you before—

Parker is riding with Mayor Paloma

in the Fourth of July parade.”

Another fin flick.

“And I’m jealous and—”

The fin stops.

I stop.

My hand shoots to my mouth,

clamps it shut.

Ottilie and I boggle at each other,

both fish-eyed.

I can’t believe I said that.

I go over to check on Mrs. Harden.

She is up and dressed

and having tea.

Her cheeks are rosy.

She doesn’t look tired anymore.

She gives me a hug.

“I’m so glad you stopped by, Suzy,”

she says.

“I have something for Parker.”

Mrs. Harden goes into the hall.

She returns with a teddy bear

dressed like a doctor,

complete with a tiny stethoscope.

“I got it at the hospital gift shop.

Think Parker will like it?”

“Sure,” I say.

Then she hands me a box

tied with red ribbon.

“And this is for you, Suzy.”

“Me?” I say.

“I’m not the one who called 911.”

Mrs. Harden drapes an arm around me.

“No, but I have a nice, fuzzy memory

of you holding my hand.

I can still hear you saying,

‘Don’t worry, Mrs. Harden.

Help is on the way.’ “

I untie the ribbon

and open the box.

And for the second time

in two days,

I burst into tears.

There, nestled in tissue paper,

is a foot-long memento baseball bat.

It says

PHILLIES WORLD CHAMPIONS

2008.

Mrs. Harden grins.

“I was going to give it to you

for your birthday.”

I hug the bat to my chest.

“This is birthday and Easter

and Christmas

for the rest of my life!”

Later,

Alison and I are sitting

on the front porch.

I’m reading to her

the first chapter of

Black Beauty,

which Ms. Mott recommended to me

since it was written in the 1800s.

Reading aloud is one way

I try to get Alison into a book.

Alison inspects her nails,

flaps at a fly,

yawns.

“I’m bored,” she says.

I give a sigh.

“How can you be bored?

I just started. Besides,

don’t you want to be an actress?”

Alison shrugs. “Yeah—so?”

“So actresses have to read scripts.”

She snorts. “I know that.

When I was in the school play,

I not only read the whole play—

I memorized it.”

“I rest my case,” I say. “You do read.”

“Only plays I’m in.”

“Just let me finish this chapter.”

Alison gives me a wicked grin.

“Can’t. Here comes Gilbert,

your not-boyfriend.”

Gilbert isn’t here for me.

“Is your dad around?”

he asks.

“Mr. Kim’s lawn mower

won’t start.

I can’t figure out

what’s wrong.”

Dad loves tinkering

with lawn mowers.

There are four in our garage.

Only one works.

The others Dad got at yard sales.

They don’t run now, but they will.

And once they work,

he’ll give them away

and buy more.

Mom calls it

Dad’s “harmless addiction.”

Like hers with books.

Dad has worked on

Mr. Kim’s lawn mower before.

Mr. Kim, who recently retired

from NASA,

always jokes with Dad.

He says: “I can send a man

to the moon, but don’t ask me

to fix a lawn mower.”

Dad comes out to the front porch.

Parker too.

Gilbert gives Parker a friendly punch

on the arm.

“Nice cape, buddy,” he says.

Parker eyeballs Gilbert’s watch.

“Nice watch.”

“Thanks. I got it at Trader Bill’s.”

Parker lowers his voice to a whisper.

“Be careful with that watch.

There’s robbers in town.”

Alison shoots me a look.

I ignore her.

Gilbert tilts his head,

reads my book title.

“Black Beauty, huh?

Any good?”

“Just getting started,” I say.

“Well, you can tell me

how you like it

over ice cream,”

he says.

He winks at me.

“Someday.”

Alison jabs me

with her elbow,

hisses under her breath:

“Aha!”

I decide to clean the kitchen

for when Mom comes home.

Dad’s great with lawn mowers

and grilled cheese sandwiches

and history

and lots of other stuff.

But cleaning—forget it.

Parker wants to help.

He stands on a chair

to wash Dad’s coffee mug

and topples over.

Next he drops the sugar bowl.

Then he steps on my foot.

“Time to go play,” I tell him.

He stomps off.

“Play, play, play—that’s all I do.”

A familiar voice replies:

“What a tragic life you have, Parky.”

I scream—

“Mom!”

I race into the hall.

I throw my arms around Mom’s neck.

“I thought you weren’t coming home

until tomorrow night.”

Mom tucks a strand of hair

behind my ear.

“Oh, sweetie, I missed you all so much.”

Early Saturday morning

Dad calls:

“Who wants to

go to the Pancake Palace?”

My eyes pop open.

Chocolate chip pancakes—

one of the best foods

ever invented.

I’m dressed and ready to go

in two minutes.

The waitress hands us our menus.

They’re so big that Parker—

who can’t read but pretends he can—

totally disappears behind his.

But not before the waitress says:

“Hey—aren’t you the little boy

who called 911?

The little hero?”

Grandma Fludd has sent gifts

home with Mom:

A fountain pen for Dad.

(He uses ballpoint.)

A box of cactus candy for Parker.

(He takes one bite and spits it out.)

And for me—

oh no—

a pair of earrings.

Clip-ons

shaped like saguaros.

I roll my eyes.

Mom tells me: “Sit tight.

I’ll be right back.”

Mom comes back

with a cardboard box.

She pulls stuff out:

A Tommy Tool screwdriver.

A pair of brown mittens

as wide as waffles.

A fan with the logo

of Frawley’s Funeral Parlor

on the front.

A pin in the shape of a crab.

A pair of ballet slippers.

I gape. “I didn’t know you took ballet.”

Mom laughs. “I didn’t.”

“Then what—”

Suddenly it dawns on me.

“Grandma Fludd gave you

this junk,” I say.

Mom shakes her head.

“Not Grandma Fludd.

And absolutely

not junk.”

Mom tells me about Grandma O’Dell.

Grandma O’Dell was Grandma Fludd’s mother—

and therefore my mom’s grandmother.

My great-grandmother.

“She was wonderful,” Mom says.

“She took me to afternoon tea

at fancy hotels.

We both wore hats and gloves.

She taught me Broadway show tunes.

She took me to New York City twice

on the train.

But, oh my, she gave the oddest presents.”

“Must run in the family,” I say.

“I threw a lot of the stuff away,” Mom says.

“But some I dumped in this box.”

“I don’t blame you.”

“Then last week Grandma Fludd found the box

in her storage bin and gave it to me.”

“How come you didn’t ditch it at the airport?”

Mom’s eyes get shiny.

“Because you don’t ditch your treasures.”

Mom tells me she would give anything

“to be having tea with Grandma O’Dell again,

opening odd little gifts:

a Daffy Duck change purse,

a pig made of tiny seashells …”

I interrupt:

“A pair of clip-on earrings

shaped like saguaros?”

I take my black dress shoes

(which I hardly ever wear)

out of their box.

I line the box with tissue paper.

I put the clip-ons in the box.

Also the comb shaped like an alligator

that Grandma Fludd sent me for Easter.

And the plastic jelly beans.

“This is my treasure box,”

I tell Ottilie.

“From my grandmother.”

Ottilie swims to the surface,

puckers her mouth.

That’s Ottilie-speak for

“Where’s my fish flakes?”

After church on Sunday,

Mrs. Harden invites me over

to work on her 1,000-piece puzzle.

She’s got a card table

set up in her living room.

Puzzle pieces lie in heaps

in each corner.

“You work that side, Suzy,”

she tells me.

The picture on the puzzle box

is of three crows

sitting on a clothesline.

I tell Mrs. Harden how

Mrs. Bagwell chased after

that crow with her flyswatter.

Mrs. Harden says: “Lucky for her

that crow didn’t swoop down

and land on her head.”

Now that’s a puzzle picture

I’d like to work on!

An hour is about all we can take

of puzzle-making.

We stop for lemonade.

Mrs. Harden asks about Grandma Fludd.

I tell her Grandma Fludd is doing fine.

I tell her about the saguaro earrings

and my new treasure box.

Mrs. Harden grabs my hand.

“I have a treasure box too.

Come see!”

Mrs. Harden’s treasure box is not a box at all.

It’s a small trunk in her spare room,

and it’s filled:

Her own baby quilt, hand-stitched by an aunt.

A Little Lulu doll.

Three packets of letters tied with string.

A stack of report cards.

(Mrs. Harden was a straight-? student.

I’m straight ?—except for my A in English.)

A navy blue sweater Mrs. Harden knitted

for her husband on their first anniversary.

The wooden bird I painted for her when I was six.

Her father’s old deflated football.

A white dress with a lace collar.

“Is that your wedding dress?” I ask.

“No,” says Mrs. Harden. “I was married

in a gray suit. This dress belonged to

my mother. She wore it to her

high school graduation.”

“It’s very pretty,” I say—even though

I’m not a fan of dresses.

I can’t remember the last time I wore one.

Mom works for Dr. Ellis,

former dean of Ridgley Community College.

She’s his part-time personal assistant.

This morning she’s about to go over to his house.

Parker whines to go along.

Sometimes Mom takes him.

Dr. Ellis lets Parker build forts and firehouses

with his many hundreds of books

as long as Parker promises

to be careful with each one.

Dr. Ellis says that’s how he came

to love books,

by building walls and castles

with his own father’s collection.

Mom tells Parker: “Not today.”

Parker flops onto the floor.

He rolls.

He kicks his feet in the air

like a bug.

He shrieks.

Until I say:

“What kind of superhero does that?”

Later, Parker’s friend Franky

invites Parker over to play.

Dad has a class to prepare.

Mrs. Harden is off to

her doctor’s appointment.

Alison is at her hip-hop lesson.

I decide to wash my bike.

Gilbert walks past.

I call out: “Hey, Gilbert.”

“Hey, Suzy.”

I want to tell Gilbert

I don’t believe for one second

that he took Mrs. Bagwell’s ring.

I want to tell him I miss the whistling.

I want to tell him I snipped some

of the mint he gave to Mrs. Harden

and am rooting it in a jar

on my windowsill.

But ever since Alison

made a joke about me liking Gilbert

as a boyfriend,

I’ve gotten a little shy around him.

And neither of us has mentioned

ice cream lately.

When Mom comes home from Dr. Ellis’s,

I tell her I’ll need a bag lunch

for Tween Time tomorrow.

She tells me there’s egg salad in the fridge.

Of course I can make my own lunch.

My dinner too.

But Mom was in Arizona for weeks,

and I’m kind of in the mood

for a little pampering.

Then Parker hops onto Mom’s lap.

“I want Smileys,” he says.

Smileys are oatmeal cookies

with happy raisin faces.

“I’ll make some tonight,”

Mom tells him.

“Anything for the little hero,”

I say under my breath.

The Tween Time plan for the day

is a “surprise” field trip.

Alison and I bring permission slips

and bag lunches.

Ms. Mott collects our lunches

in a big wicker basket.

She jabs at the air with

her closed parasol.

“Off we go,” she says,

still not telling us where we’re going.

Alison groans. “It’s a picnic.

I hate picnics. All those bugs.”

“It’ll be fun,” I say.

The boy asks Ms. Mott:

“Where are we going?”

“To Old Elm Cemetery,” Ms. Mott says.

Alison hisses in my ear. “Cemetery? Fun?

Did you say fun?”

I say: “Okay … interesting.”

Old Elm Cemetery

is a fifteen-minute walk

from the library.

Dad has talked about it,

but I’ve never been there

till now.

It’s pretty, really.

Old trees.

Tall hedges.

Flowering bushes.

Mossy marble stones.

Ms. Mott spreads

a red-checkered tablecloth.

We sit in a circle

eating our lunches.

Alison swats a bee

from her cupcake.

Ms. Mott tells us

how people in the 1800s

used to picnic here,

because there weren’t

many open spaces

for the public back then.

A cemetery was like a park.

She says: “Some people came

just to be near loved ones

who had died.

They found it comforting.

Some people came

just for the quiet.”

Suddenly

Alison shrieks:

“Holy tamales!

I think

I just bit into a bug!”

On the way home,

Alison hooks her arm

into mine.

“I know I’m a pain.”

I don’t say anything.

“A first-rate complainer.

Don’t deny it, Sooze.”

I don’t deny it.

“It’s in my DNA.

Blame my aunt Gertrude.”

Silence.

Alison turns, gives me

a big hug.

Right there

on the sidewalk.

“Thanks for putting up

with me,” she says.

You gotta love her!

Dad asks if we tweens

walked around the cemetery,

if we looked at headstones.

“No,” I say. “We just had a picnic.”

Dad says: “Maybe you and I

can go for a walk around Old Elm

someday. Check out

the headstones.”

The part about

looking at headstones

sounds pretty depressing.

But I do like the part about

me and Dad doing something

together.

Just us two.

Without

the little hero.

On Wednesday morning,

Mrs. Harden calls

to see if I want to

help her make

a gingerbread cake

for Gilbert.

Today is his birthday,

and gingerbread

is his favorite.

Mrs. Harden measures the flour.

I crack eggs,

pour molasses.

Ginger

and cloves

and cinnamon

go into the bowl.

I used to like licking the bowl

until Alison told me

raw batter

can kill you.

While the cake is baking,

I make Gilbert a card.

Red and white

with baseball stickers,

because Gilbert likes the Phillies

almost as much as I do.

I print HAPPY BIRTHDAY inside—

though how happy can it be

with a dad who drinks too much

and a neighbor who thinks

you are a thief.

The cake is finished.

Mrs. Harden dusts it

with powdered sugar.

She puts it in her cake carrier.

She asks me to bring

Gilbert’s present along.

It’s a Phillies T-shirt

in a Phillies backpack,

and doesn’t the card

I made for Gilbert

go perfectly.

I’d never been to Gilbert’s house.

We drive ten blocks.

I expected a small house—

maybe with Gilbert’s dad

drinking beer and slouching

on an old lawn chair.

But there’s no sign of

Gilbert’s dad.

As for the house,

I was right.

It is small.

But there’s something

I didn’t expect:

it’s also very

pretty.

I tell Ottilie

about Gilbert’s house.

About the blue shutters

and window boxes

dripping pink petunias.

I tell Ottilie

about the wind chimes

twinkling.

The brick patio

Gilbert built himself

with bricks from

the old print shop.

I tell Ottilie

how Gilbert’s mom

brought us iced tea

with fresh mint

from her herb garden.

And how she served the cake

on flowered plates—

so what if they didn’t match.

I tell Ottilie

how glad I am

that Gilbert’s life

isn’t just about

his dad’s drinking.

Or not having much money.

Or Mrs. Bagwell

saying bad things about him.

It’s also about his nice mom.

His pretty house.

And his friends sharing

homemade birthday cake

on a patio he built himself.

That I find myself

thinking about

Gilbert.

A lot.

Like a big brother?

I ask myself.

Not really.

How about a cousin?

Nope.

Or a special friend?

Getting close.

A very special friend?

BINGO!

All of a sudden

everyone is thinking about

Ridgley’s Fourth of July parade—

which will be on July 3 this year

because the Fourth falls on a Sunday.

Mr. Capra says

he and the people he works with

are putting together a bike brigade—

streamers and flags,

fancy baskets and bells.

Mr. Kim is refurbishing

his float from last year,

patching the rocket with aluminum foil,

blowing up another yellow beach-ball moon,

repainting the clay astronauts.

Ridgley High’s marching band

is practicing on the football field.

Mr. Ellis has Mom dust off

his George Washington costume.

Alison and I are signed up

to walk with the Ridgley Library group.

We’ll wear T-shirts that read

I LUV MY LIBRARY.

And Parker,

the little hero,

gets to ride in Mayor Paloma’s

cool blue convertible

with the top down.

Mom tries to take Parker’s ratty old cape.

Parker clutches it around his neck.

He howls.

“You don’t need a cape

to be a hero,” Dad tells him.

More howling.

“It’s ripped,” I say. “And it smells yucky.”

Parker holds his nose.

“You smell yucky, Suzy Poo-poo,” he says.

Mom wheedles. “Now, Parky, what if we get you

a new cape? Something really nice for the parade?”

Parker stops clutching. He sniffles.

“Will it have blue stars?”

Mom nods. “If you want blue stars.”

“When?” he asks.

“In a couple days.”

“Okay,” he says. “But I’m wearing

this one till then.”

Later, Mom sneaks it off him

when he’s sleeping.

She throws it in the trash can.

Mom gets Mrs. Capra—

a master quilter—

to make the new cape.

“Lots of stars!” says Parker.

“You got it,” says Mrs. Capra.

Next Parker decides he wants

a haircut.

Dad takes him to the barbershop.

Then Mayor Paloma’s assistant calls

with instructions:

“Bring the boy to the mayor’s office

at nine a.m. sharp on the day

of the parade.”

The parade doesn’t start till ten,

but there’s going to be

a brief ceremony first.

Parker will get a medal.

There will be photos with the mayor.

It seems as though

the whole parade

is about Parker.

Oh well—my birthday

is coming up,

and Dad is going to take me

to a Phillies game.

Good seats … hot dogs …

root beer … rally towel …

maybe even an autograph

or two.

On July 15.

At least I’ll be a star

that day.

I’m walking home from Alison’s.

She wanted us to make fancy headbands

to wear in the parade tomorrow.

Suddenly the sky goes dark.

Lightning flashes.

Fat drops of rain fall.

I start to run.

Old newspapers fly past.

A trash-can lid clatters by.

Now it’s pouring, and I’m soaked.

I can’t see ahead.

Through the howling wind, I hear my name.

I move toward the voice—

It’s Mrs. Bagwell standing at her door.

“Hurry, Suzy! Come inside!”

I make it to her doorway.

Then the whole earth shakes.

My ears pop, and it feels like

the end of the world

as Mrs. Bagwell and I leap

into her hall closet

together.

It was not the end of the world.

It was the sixty-five-foot evergreen

in Mrs. Bagwell’s backyard

uprooting and crashing down

just inches from the house.

It was not the end of the world,

but it could have been

for me and Mrs. Bagwell

if the angle of the tree-fall

had been the least bit different.

It could have been

the end.

“I heard about the tree,” he says.

“Are you okay?”

I give him a thumbs-up.

“Thanks to your friend Mrs. Bagwell.”

“So I guess it’s true.” He smiles. “There’s

good in everyone.”

“Where were you in the storm?” I ask.

“At home,” he says. “Eating ice cream.”

We both laugh.

We sit there on the porch

just talking,

being.

The trees glisten green.

I’ve never seen

trees so green.

Parker is so wound up

before the parade

that he throws up

his cornflakes.

Twice.

Mom is so excited

about meeting the mayor

that she heads out the door

with two different shoes on.

Alison does my hair

with the fancy hairband.

She keeps saying:

“I can’t believe it! You were

almost crushed to death!

By a Christmas tree!”

A zillion people

drive past Mrs. Bagwell’s

famous fallen evergreen.

Some try to take photos.

Some succeed.

Some she chases off

with her flyswatter.

The parade goes fine

except when

Uncle Sam on stilts

topples over into the crowd

and sprains his ankle.

Oh, and when Paco the Parrot

squawks a stream of

bad words.

It’s an odd sort of day.

Alison blames it on the storm.

“Something’s in the air,” she says.

“I can smell it.”

I give her a look. “I can smell it too.

You’re wearing too much perfume.”

Parker wears his cape

and his medal from the mayor

to church.

Pastor McCleary actually mentions

Parker in his sermon.

All day Parker flashes the medal

in our faces.

He even goes into my room

to show off

to Ottilie.

At the fireworks

Parker struts around our blanket

flashing his medal,

flapping his cape.

Twice Mom tells him

to “please sit down.”

But there’s such a smile

in her voice

he totally ignores her.

I really don’t know

how much more

of this little hero stuff

I can take.

On Tuesday

on the way to Tween Time

Alison is all bubbly with

guess-whos

and guess-whats.

“Guess who really stole

Mrs. Bagwell’s ring?”

“Guess what Mrs. Bagwell

is doing now?”

“Guess what you and I

are going to do this Friday?”

I hold my hand up. “Whoa!

One guess at a time, please.”

“A crow!” Alison tells me.

She jabs her finger at me and repeats:

“A crow!”

I think Alison is getting goofy.

“Crows steal jewelry?”

“Yes!” she says. “The tree guy

found the ring in a crow’s nest

when he was sawing off the branches

of Mrs. Bagwell’s tree.

There it was all shiny—

couldn’t miss it.”

“And he gave it to Mrs. Bagwell?” I ask.

Alison grins. “Honesty is alive and well

in good old Ridgley.”

“But how—?”

“Seems Mrs. Bagwell was wearing

the ring last spring.

She took it off to pick up a clump

of muddy leaves.

She set it on her patio table.

A crow must have spied it.”

Of course at the bottom

of it all,

I couldn’t care less about

crow, nest, or ring.

“What about poor Gilbert?” I ask.

Alison grins again.

“I’m coming to that.”

“Well,” she says, “Mrs. Bagwell was

so embarrassed about accusing Gilbert

that she drove right over

to his home and apologized.”

“Really?” I say.

“Really!

And she told Gilbert

to go to Ernie’s Bike Shop

and choose any bike he likes.”

I shake my head.

“Are we talking about

our Mrs. Bagwell?”

“You bet,” says Alison. “And

my dad heard she is going to

put an ad in the Ridgley Post

that her misplaced ring

has been found.”

“Sounds like Mrs. Bagwell

is a changed woman,” I say.

Alison snorts. “Not totally.

Earlier, I saw her chasing

the Kims’ cat with her fly swatter.”

When we get to the library,

Ms. Mott waves us through the door.

There’s no time to ask Alison

about what she’s planning for us

on Friday.

Just as well.

It’s probably something

I’m going to hate.

Like getting our nails done.

(Alison’s cousin Tara

likes to practice on us.)

Or making bracelets

with Alison’s bead kit.

Or Alison trying to teach me

her latest hip-hop routine.

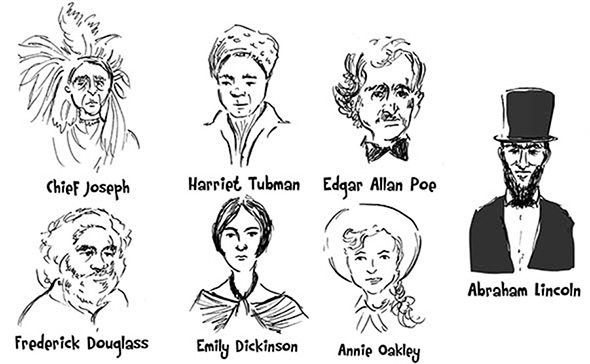

Pictures are tacked up

all around the Bennett Room,

pictures of famous people

from the 1800s.

Ms. Mott points to each one:

Abraham Lincoln—president of the United States.

Florence Nightingale—nurse.

Sarah Bernhardt—actress.

Edgar Allan Poe—author.

Harriet Tubman—”conductor” of the Underground Railroad.

Emily Dickinson—poet.

Chief Joseph—chief of the Nez Perce Nation.

Annie Oakley—star of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show.

Frederick Douglass—leader in the abolitionist movement.

Ms. Mott instructs us to choose

the person we’d like to learn more about.

Alison elbows me. “Learn,” she growls.

“What is this? School?”

“Shhh,” I say.

Ms. Mott goes on. “Once you’ve decided,

you may choose a few books from the back table

about that person.”

Alison mock-cheers. “Yippee.”

“And next week,” says Ms. Mott, “we’ll each come

dressed as our favorite, ready to share

what we’ve learned.

Alison leans over and whispers: “Next week

I’m going to be sick with one of those 1800s diseases.

What were they—typhoid fever? Gout?”

But when Ms. Mott asks Alison about her choice,

Alison replies all nice and polite:

“Sarah Bernhardt, Ms. Mott. The actress.”

Ms. Mott pats Alison on the head.

“Why am I not surprised?”

I don’t know what draws me

to Emily Dickinson.

I’m more the Annie Oakley type.

But it’s something about

Emily’s face—

her eyes, I think.

She looks so content.

And her hands—

so graceful and relaxed.

“I’ll be Emily Dickinson,”

I tell Ms. Mott.

Ms. Mott sends me a smile.

“Good choice, Suzy.”

I take three books

about Emily Dickinson

from the table.

When Alison goes

to the ladies’ room,

I skim a few pages.

I read that Emily

had a talent

for the piano.

She called it “moosic.”

As she got older,

she stopped going places.

She even hid from guests

who came to the house.

She carried on her friendships

by letter.

She wore only white dresses.

Not exactly my kind of chick.

On the way home,

all Alison does is

complain.

“No way am I going to read

an entire book

on summer vacation.”

“Just skim it,” I tell her.

She ignores that. Keeps whining.

“And a report!

Is Ms. Mott joking?

That’s homework. Homework! In July!”

“You don’t have to give a long report,”

I say. “Just a little something about

your person.”

“Let’s just quit Tween Time.”

“No way,” I tell her. “I like Tween Time.”

Then, to change the subject, I ask:

“So—what’s this about Friday?

What are you and I going to do?”

Her sour face brightens. She claps her hands.

“We’re auditioning for a play!”

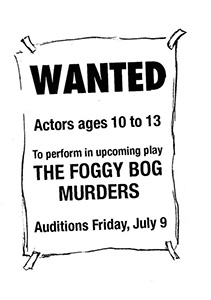

The next day,

Alison and I go to

the Ridgley Community Theater.

The sign on the door says:

WANTED:

ACTORS AGES 10 TO 13

TO PERFORM IN UPCOMING PLAY

THE FOGGY BOG MURDERS.

AUDITIONS FRIDAY, JULY 9

I tell Alison: “I can’t audition

for a play.”

“Why not?”

“I wouldn’t know what to do.”

Alison drapes her arm around me.

“I’ll tell you what to do.”

“Besides,” I say, “I don’t want to

be an actress. You do.”

“Maybe you do too,” says Alison.

“You just don’t know it yet.”

We go to Alison’s.

Up in her room

she digs through some papers

and comes up with

the script from

last year’s school play,

Snow White in the Big City.

Alison played the lead—

Snow White.

I was stage crew.

She plops on the bed

beside me.

“We’ll practice with this,” she says.

“I’ll be Snow White.”

“Of course.”

“You’ll be the witch.”

“Of course.”

So it’s set.

For the audition we will do

a scene from Snow White in the Big City.

Alison tucks her blond curls

under the old Snow White wig.

The witchiest thing she can find for me

is an old black T-shirt of her father’s.

There’s a hole under one arm.

We sit back on the bed.

We turn pages to the part where

the witch—posing as a waitress—

tries to get Snow White to order

the poison-apple Danish.

I read my line: “This Danish is delicious.

You must try it, my dear.”

Alison—as herself—screeches: “No! No! No!

You’re supposed to be a witch. You sound like

that nice waitress at Daisy Donuts.”

“Well, aren’t I a waitress and a witch?”

Alison looks at the ceiling, then back at me.

“You’re mainly a witch. You have to sound like a witch.”

Alison demonstrates. Her voice turns sinister:

“Zees Danish eez dee-lizzious. You muuuzzt try eet.”

She goes on: “Then you cackle. Like this—

HEE-HEE-HEE-HEE-HEE!”

“Do I have to cackle?” I ask.

Alison smacks her forehead.

“Yes, you have to cackle.

Witches cackle.

You’re a witch.

You cackle.“

Dad likes that I am learning

about Emily Dickinson.

At dinner, he tells a story

about Emily’s father,

Mr. Dickinson—

who left the house

in his underwear one night

and woke the entire

neighborhood

with church bells

so that the people could see

the northern lights.

“Whew!” I say.

“With a dad like that,

no wonder Emily

didn’t want to

leave the house.”

After dinner,

I practice my cackling

on Ottilie.

She hides behind

her sunken treasure chest.

Mom calls upstairs:

“Suzy Q, what’s going on?

Are you laughing or crying?”

“Neither,” I call down.

“I’m cackling.”

There was a time—

not so long ago—

when Mom was actually

interested in me

and would have walked upstairs,

poked her head in my door,

and asked me why

I was cackling.

Now

she stays downstairs,

all busy baking more Smileys

for Hero Boy.

Before bed,

I choose an Emily Dickinson poem

to read to Ottilie.

It’s the one that begins:

“Ah, Moon—and Star!

You are very far—”

Those are the only two lines

of the poem I understand.

Ottilie swims to the other side

of her tank.

I think she agrees with me.

I tell her to do

what my English teacher,

Mr. Ranft, told us:

“When you don’t understand

the words of a poem,

just let the sounds wash over you.”

Easier for Ottilie since she lives

underwater.

That night I dream

I am Emily Dickinson.

The moon is far.

The stars are twinkling.

I peek at them

through my curtain.

I am wearing a white gown.

I sit at the piano that

is in my room.

I play beautiful

“moosic.”

People from all over Ridgley

gather in the front yard.

Dad goes out on the porch

in his underwear

and thanks them for coming—

“But my daughter

doesn’t receive visitors,”

he says.

Gilbert is in Mrs. Harden’s driveway

on his new bike—

a silver Schwinn Corvette

with black trim.

I go over to admire it.

“Cool,” I say.

Gilbert grins, then says:

“Want to ride bikes over to

Ridgley Park?”

“Darn,” I say. “I can’t.

Alison and I are going to

practice our parts.”

“Parts?”

“We’re auditioning for a play

together.

On Friday.”

Gilbert gives me a thumbs-up.

“Good luck.”

He starts to pedal away,

leaving me alone with the day,

one of those perfect July days:

breeze,

smell of fresh-cut grass,

sky blue as poster paint.

I pull out my own bike,

hop on,

pedal hard.

I catch up with Gilbert in the park.

He and his new bike are leaning against a tree.

“Hey,” I say.

Gilbert looks up. “Hey, Suzy. I thought you

were going to Alison’s.”

“I’ll go later,” I tell him.

I get off my bike and sit on the grass.

Gilbert sits next to me.

“My birthday’s coming up,” I say.

“July fifteenth.”

Gilbert grins. “Thanks for the heads-up.”

I laugh. “I’m not fishing for a card or present.

I’m just saying that my dad’s taking me

to a Phillies game.”

As soon as the words are out of my mouth,

I regret them.

I’m pretty sure Gilbert’s dad

would never take him to a game.

So I’m shocked when Gilbert tells me

his dad took him last fall—

to see the Phillies play the Atlanta Braves.

What pops in my head next is:

I thought your dad had a drinking problem.

Of course I know better than to say

everything that pops into my head.

Instead I ask: “So—did you get any autographs?”

Gilbert and I sit for a while

pulling blades of grass.

Then I tell him

how annoying it is

when your little brother

is a hero.

And Gilbert tells me

how much he misses

his best friend, Luis,

who is spending the summer

with cousins in New York.

And I tell Gilbert

how nervous I am about

trying out for the play.

And he tells me

how worried he was

that Mrs. Bagwell’s ring

would never turn up.

And I tell him

how much I missed

his whistling.

And he tells me

how much he appreciated

that I never treated him

like a thief.

And we both laugh about

Mrs. Bagwell’s

dreaded green flyswatter.

And then we just sit there

on the grass

not saying much of anything.

When I finally get to Alison’s,

she is hopping mad.

“Where the heck were you?” she growls.

“Riding my bike,” I tell her. “Talking

to Gilbert.”

Alison shoots me a glare.

“I knew it!”

“Big deal,” I say. “I’m only ten minutes late.”

“Ha!” Alison snorts. “Tell that to

the director on Friday.”

“I won’t be late on Friday.”

“Well, if you are,” she says, “you can

kiss this friendship goodbye.”

I give one of Alison’s curls a tug.

“I said I won’t be late.”

“Fine,” she says.

“Fine,” I say.

Alison and I practice our lines.

I try two kinds of cackling.

“Go with the first cackle,”

Alison tells me.

Then she takes a fake bite

of the fake Danish

and fake faints

while I cackle—

over and over

and over again.

Finally

she pronounces us

ready for the audition.

She tells me to go home,

eat protein for dinner,

and get a good night’s sleep.

“Rest my cackle,” I say.

She almost grins.

Mom is in one of her fogs

this afternoon.

She started looking up a recipe

for spinach ravioli

and ended up reading

half the cookbook.

So it’s plain cheese omelets

for supper.

Protein.

Alison will be pleased.

I make my announcement

over dessert.

“I’m going to audition tomorrow.”

Mom’s spooned rice pudding

stops midair.

“Audition?”

“Me and Alison,” I tell her.

“At the Ridgley Community Theater.”

“You never said a word,” says Mom.

“Remember all the cackling?”

Dad’s eyes boggle. “You’re auditioning

to play a chicken?”

Later, Mom asks me what I’m going to wear

for the audition.

I show her Mr. Wilmire’s old black T-shirt.

She wrinkles her nose. “I can do better.”

She pulls a dress from the back of her closet.

It’s satiny black.

Mom sighs. “It’ll never fit again.

You may as well get some use out of it.”

I try it on.

I look more like a witch.

I start to feel more in character.

I start to believe the audition will go well.

I start to imagine what people will say about me

when they hear I’m in a real play.

I go to my room, stand in front of the mirror.

I practice a pose for when

the Ridgley Post photographer comes

to take my picture.

Alison and I walk into the theater.

She says her stomach is all butterflies.

She says that’s a good thing.

My stomach is more like

crows in a tornado.

Not good.

I quickly run to

the ladies’ room.

A guy in jeans and a tie-dyed shirt

writes down our names and ages.

He tells us where to sit—

row 10 with eight other kids,

three of them boys.

There are some grown-ups

in row 11.

Parents, I think.

The woman in row 3

stands up, faces us.

“Hi, everyone,” she says.

“I’m Giselle. I’m the director.”

She starts bringing kids onstage

one at a time.

Most read from a script.

One boy has his lines memorized.

A girl in purple recites a poem.

Alison and I go last.

Alison tells the director

we are going to do a scene together.

“Sure,” says Giselle. “But do the scene twice

so I can focus on one of you at a time.”

It’s hard to tell, but I think

things went better the second time around.

Especially my cackle.

I wonder which of us

Giselle was watching then.

Afterward,

Giselle gathers us all in a side room.

She applauds.

“Bravissimo!” she goes. “Good job, actors.”

Then she leaves.

The guy in jeans and tie-dye

tells us they will be casting four kids—

two girls and two boys.

“When can we expect a call?” asks a parent.

“Sometime Tuesday,” says the guy.

He thanks us. He gives us a thumbs-up.

“Good job, people.”

Alison pokes me in the ribs, whispers:

“He’s looking right at us!”

With the audition over,

I can focus on my

Emily Dickinson project.

I start reading the first book

about her.

But my mind keeps wandering

back to how it felt being onstage.

To Giselle using her first name

with us kids like we were

real theater people.

To the guy in jeans and tie-dye

looking straight at me and Alison.

The phone rings.

Even though it’s not Tuesday,

my heart does a flip.

Mom calls to me:

“It’s Mrs. Harden. She wants you to

go over for a minute.”

Mrs. Harden wants to move her desk

closer to the window.

“Think we can do it?” she asks.

“Sure,” I say. “It’s not that heavy.”

I flex my arm muscle.

After the desk is in place,

we sit down to iced tea and cookies.

(No raisins.)

I tell Mrs. Harden about the audition—

how well I think it went,

how wearing Mom’s black dress

got me more into character.

“Now I need to focus on being

Emily Dickinson

for Tuesday’s Tween Time,” I say.

Mrs. Harden has an idea.

“Think of Emily as a role you’re playing.

Dress the part as you’re reading about her.

Try to get into the poet’s head and heart.”

I like that.

“But I don’t have a white dress,” I say.

Mrs. Harden grins. “I do.”

I’m a little nervous about taking

the white dress that

Mrs. Harden brings me.

It’s the one from her treasure chest—

her mother’s high school graduation dress.

Mrs. Harden says her mother would

have loved the idea—

a young friend wearing it as part of

a project on Emily Dickinson.

“Mother loved poetry,” she says.

Funny how a dress can change

how you feel.

When I wear Mom’s black dress,

I feel more like the witch in Snow White.

Now, slipping into Mrs. Harden’s white dress,

I feel kind of like Emily Dickinson,

more able to focus on her life.

I stand in front of the mirror.

I turn, swishing.

I swish over to Ottilie’s tank.

“Want to learn about Emily Dickinson?”

I say.

Ottilie swishes her tail.

That has to mean yes.

I start reading about Emily.

Aloud.

All weekend I work on

my Emily Dickinson report.

I’m down to two poems.

Which shall I read?

“I’m nobody!

Who are you?”

or

“Hope is the thing

with feathers.”

“I’m nobody” is probably

more famous, but it’s

kind of a downer.

I don’t want to depress

the audience.

I’ll go with “Hope.”

On Monday morning,

I hear Parker yelling outside.

Cape flying—he’s chasing after

Shady the cat.

I see the cat scoot under

Mrs. Harden’s porch.

“Why are you chasing the Kims’ cat?”

I ask.

Parker scowls. “I think that cat

caught a mouse.”

“That’s what cats do,” I tell him.

“But I saved Mousey!”

“You did?”

“Yeah. I scared that cat and

I helped Mousey get away!”

I pat Parker on the head. “Good for you.”

“Just doin’ my job,” he says, flapping off.

Alison comes over after lunch.

She opens her suitcase

and shows me her Sarah Bernhardt costume:

Blue dress with ruffles and puffy sleeves.

Three long strands of plastic pearls.

Her Snow White wig.

(Miss Bernhardt had dark hair.)

And a wide-brimmed navy blue hat

with a peacock feather.

“Wow!” My eyes go wide. “I know where

you got the wig—but what about the rest of the stuff?”

Alison grins. “Borrowed it from the Ridgley

Community Theater.

They have a great costume closet.”

“They actually let you take something from it?”

“I told them it was for a project—community service.”

“Bull,” I say.

“Hey, I’m part of the community.”

Dad’s in the garage

tinkering with a lawn mower.

I’m in the living room with Mom,

reading about Emily Dickinson.

Suddenly Mom screams.

Parker comes running.

Mom points a trembling finger.

“Sp-spider—”

It’s sitting on the stack of newspapers—

smack on Parker’s picture,

on his nose.

Parker puffs his little chest.

“Don’t worry, Mommy. Hero Boy

will save you.”

He lifts the top section of the paper

and carries the spider out the front door.

I hope he remembers Dad said, Don’t kill spiders.

They eat other bugs.

Parker does remember.

He dumps the spider over the porch railing

onto the grass.

Then he stands posing by the front door.

He looks up and down the block.

He says: “Today I saved Mousey.

And Mommy. And a spider.

Where’s that newspaper lady?”

I feel kind of sorry for Parker.

The newspaper lady has

more important things

to write about now.

Nobody wants to read about

spiders and mice.

Parker can flap around

in his cape

and save every mouse

and spider

in Ridgley,

but his fifteen minutes

of fame

are over.

And now it’s

my turn.

Probably a part in the play.

I bet that reporter will be there at

The Foggy Bog Murders

on opening night.

And of course—

my birthday.

Whatever Mom bakes that day

will definitely not

have raisins.

And there’s

the Phillies game.

I’m so excited

I keep Ottilie up

half the night

talking.

The phone rings.

Could it be Giselle?

Would she call this early?

Did I get the part?

Mom pokes her head

in my room.

“It’s for you, Suzy Q.”

My heart flaps.

I pick up the phone.

It’s Alison.

She has a question:

“Are we walking

to the library

as Sarah and Emily

or getting changed there?”

Alison and I carry

our outfits to the library.

We get dressed in

the ladies’ room

with the other Tween Time girls.

Besides Sarah

and Emily,

there’s a Florence Nightingale

and an Annie Oakley.

Ms. Mott greets us as

Harriet Tubman.

She carries an old railroad lantern.

The one boy is Chief Joseph.

Ms. Mott asks who wants to go first.

I raise my hand.

Ever since the audition

I’ve been feeling more

confident.

“I’m the poet Emily Dickinson,”

I tell the group.

“I was born on December tenth,

1830.

When I was a young girl,

I did regular stuff.

I went to school and to parties.

I liked to sing and draw

and play the piano.

I wore pretty dresses. All colors.

When I got older,

I stayed in my room more,

writing poems.

If I did go out,

it was only to my garden

or to visit my friend Susan

across the yard.

I helped in the kitchen.

I enjoyed baking.

Sometimes I lowered

gingerbread and other treats

from my window—in a basket—

to the neighborhood kids.

I had a dog, Carlo.

In my later years

I wore only white.

I died on May fifteenth, 1886.

Most of my poems

weren’t published until after

my death.

I’ll read one now.”

“Hope is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul.

And sings the tune without the words.

And never stops at all.

“That’s the first stanza

of the poem called Hope.

I chose this one

because I’ve been

feeling grumpy lately.

But now I’m not.

Now I’ve got hope

perching in my soul.”

Ms. Mott leads

the applause.

Annie Oakley tells

how she was the star

of Buffalo Bill’s

Wild West show.

She pulls out two

cap pistols.

She twirls them

round her fingers.

She points them

at the ceiling.

POP! POP! POP!

I expect

one of the grown-ups

in the library to hiss

SHHHHHHH!

But no one does.

The girl who is dressed as Florence

says she didn’t have much time

to prepare because

they had a house full of

out-of-town company

over the weekend.

She tells us that

Florence Nightingale’s parents

hated the idea

of her becoming a nurse.

And then the girl

opens up

a toy nurse kit

and gives each one of us

a Band-Aid.

Sarah, aka Alison,

glides to the front of the room

like she’s getting an Oscar.

She tells how Sarah Bernhardt bought

her own coffin

and sometimes slept in it

instead of her bed.

She says it helped her

to understand

her tragic roles better.

“Creepy,” says Annie Oakley.

Ms. Mott—as Harriet Tubman—

goes next.

She tells how she escaped

from slavery

and helped others escape

using the Underground Railroad.

She sings a song she loved:

“Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.”

People from other parts

of the library

come and stand in the doorway

listening.

We all get a little teary-eyed

when Chief Joseph says:

“Hear me, my chiefs; I am tired.

My heart is sick and sad.

From where the sun now stands,

I will fight no more forever.”

Ms. Mott passes around

a box of Kleenex.

Alison and I are too anxious

about Giselle’s phone call

to take time to change our clothes.

We wear our 1800s outfits

down the streets of Ridgley.

Some teenagers call out a car window:

“A little early for Halloween!”

After I leave Alison,

I start to run home.

It’s not easy running

in a long dress.

I nearly catch my foot

in the ruffled hem.

Whew! I would not

want to ruin

Mrs. Harden’s mother’s

graduation dress.

So I speed-walk instead.

When I go into the house,

I hear Mom on the phone

saying: “I’ll tell her.”

“Wait!” I yelp. “I’m here.”

But Mom has already

hung up.

The phone call

was for me—

but it wasn’t Giselle.

It was Alison

asking if I’d gotten

the call yet.

I pull up a chair.

I sit by the phone.

Dad walks past,

pats me on the head,

says: “A watched phone

never rings.”

I stop watching the phone.

It rings before dinner.

It’s Giselle.

She is saying nice things

about the audition.

“You did really well, Suzy.

I especially enjoyed your cackle.

I hope you’ll try out for us again.”

“Again?” I say.

“For another play,” says Giselle.

“Gee, everyone was so good. But

we only needed four kids.

Hard choice. Really hard choice.

I’m sorry.”

My heart crumples.

I go up to the bathroom.

I turn on the tub water full blast

so no one will hear

my stupid sobs.