6. The Modern Western

“Planes, automobiles, trains, they are great, but when it comes to getting the audience’s heart going, they can’t touch a horse.”

—John Wayne

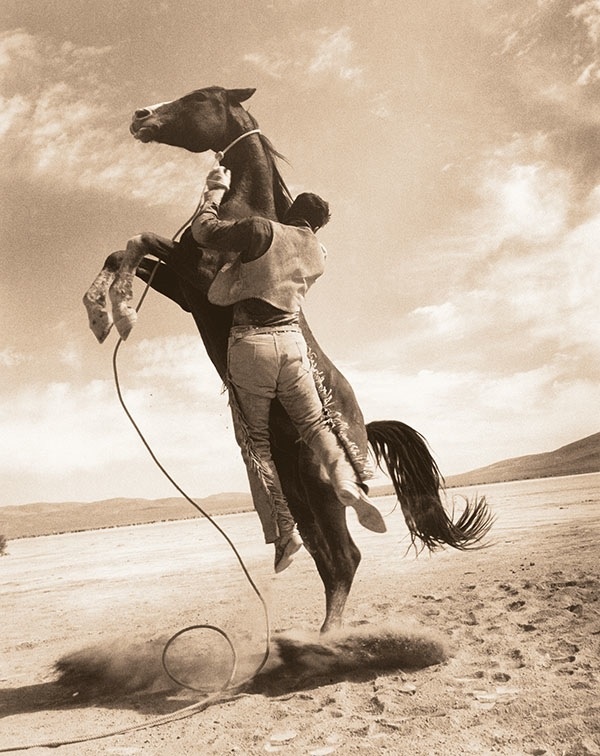

Boots gives Clark Gable’s double Henry Wills a lift in John Huston’s unflinching 1961 Western drama The Misfits.

As America entered the political and social minefield of the 1960s, the entertainment industry mirrored the public’s mood with harder-edged films. The squeaky-clean cowboy and his clever trick horse went the way of the dinosaur, and filmmaking technology advanced to embrace popular taste for pyrotechnics. Car chases replaced horse chases as the currency of action movies, while spaceships and James Bond gizmos upped the entertainment ante. The Western had to adapt or be left in the dust. Modern elements were introduced to make the genre more relevant, but good old-fashioned oaters still surfaced, usually driven by powerful directors and stars lured by romantic tales of the West and the sheer fun of playing cowboys on horseback.

Two stylized black-and-white films examined the disappearance of the good old days with an unflinching eye. In 1961, director John Huston dispelled the myth of the West with the harsh romantic drama The Misfits. The violent capturing of wild horses for slaughter, utilizing trucks in a stark landscape, represents a shocking transgression of the carnal over the spiritual. Man’s brutish domination of nature is exemplified by hard-bitten cowboy Clark Gable’s battle with the doomed horses. Like Marilyn Monroe’s character, who is forced to witness the heartbreaking scene, audiences can only watch in horror.

The disturbing action was accomplished with Hollywood horses. Boots, a gelding trained to fight by Corky Randall, worked with Gable’s stunt double. Although reportedly easy to handle when not revved up for a scene, Boots nailed Gable’s double three times with his hooves and knocked the lens shade off the camera in a close shot. Movie horses are well trained, but there are always risks involved in working with them, especially in fighting scenes.

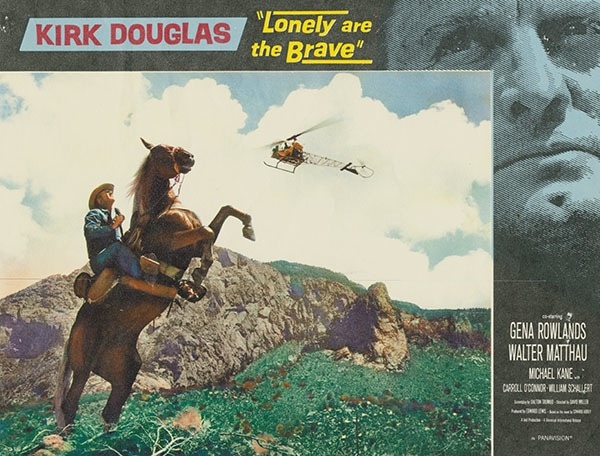

In Lonely Are the Brave (1963), Kirk Douglas plays Jack Burns, an altruistic outlaw cowboy on a collision course with the modern world. He starts a fight in order to be jailed with his best friend so he can engineer an escape. His friend prefers to do his time, and Jack goes on the run with his beautiful young mare, Whiskey. Described in the movie as “part range stock, part Appaloosa,” the trick-trained mare was actually a Saddlebred with a copper coat and a snowy mane and tail. Appropriately named Bronze Star, the gorgeous dark palomino playing Whiskey was owned by horse rancher John Phillip Sousa.

Jack dearly loves his horse, who embodies the freedom being usurped by “No Trespassing” signs, barbed wire, and other symbols of “progress.” Jack and Whiskey are pursued by Sheriff Johnson (Walter Matthau), whose closest tie to nature is a stray dog he watches through the bars of his office window. Chased by jeeps and helicopters, Jack and Whiskey make it over a treacherous mountain pass only to be struck on a rain-slicked freeway by a semitruck carrying a load of toilets. Badly battered, Jack survives, but Whiskey is severely injured and shot by the sheriff’s deputy. The look on Kirk Douglas’s face as he hears his beloved mare dying is excruciating. The heavy symbolism of Lonely Are the Brave signifies the death of the romantic Wild West.

The Western film, however, refused to die. Challenged by the legacy created by masters of the genre, many of Hollywood’s greatest talents have dared to saddle up in the past few decades. Like John Wayne, they’ve known that, despite the razzle-dazzle of technology, nothing can replace the romantic allure of the all-American cowboy and the thrill of seeing fine horses going full throttle.

The conflict between the cowboy way and technology is illustrated beautifully as Whiskey confronts a chopper on this lobby card of Lonely Are the Brave (1963).

Big Guns on Horseback

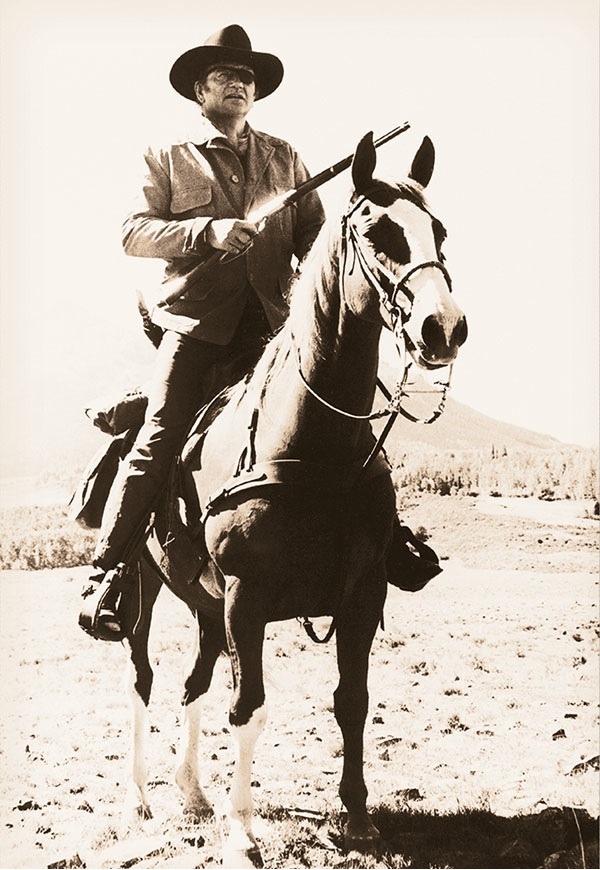

John Wayne, of course, continued to make old-fashioned Westerns into the 1970s. His performance as the salty aging cowboy Rooster Cogburn in 1969’s True Grit won Wayne a Best Actor Academy Award. One of the most endearing scenes in the movie comes at the end, when he jumps his horse over a fence to prove his virility. The horse was a wide blaze-faced sorrel Quarter Horse named Dollor. Though his name was a derivative of the Spanish word for sorrow, dolor, the sorrel gelding was a joy for Wayne to ride. In Rio Lobo, released in 1970, Wayne rode Cowboy, a dark reddish brown horse with a bald face and three stockings owned by the Randall Ranch. For 1972’s The Cowboys, Randall Ranch supplied the actor with a buckskin gelding. In 1971’s Big Jake, Wayne rode another sorrel, this one with a narrow blaze and high hind stockings. This gelding, named Dollar, belonged to Stevie Meyers, who also owned James Stewart’s favorite horse, Pie. Wayne rode Dollar in several more films, including 1973’s Cahill, United States Marshall, 1975’s Rooster Cogburn, and his final film, The Shootist, released in 1976. Because of the similarities of the names Dollor and Dollar, the two horses have sometimes been confused, but careful scrutiny of their markings leaves no doubt as to which horse is which.

John Wayne and his True Grit mount, Dollor, who also appeared with the star in The Undefeated (1969).

Though partial to sorrel horses, John Wayne rode an Appaloosa stallion, Zip Cochise, in director Howard Hawks’s 1969 Western El Dorado. A colorful brown with a large spotted blanket, Zip Cochise was owned by Chub Ralstin of Lapwai, Idaho. Because of his height, Wayne actually looked fairly ridiculous on the stout little Appaloosa, but Cochise, as the star called him in the movie, didn’t seem to mind. Obviously well trained, he stands patiently when Wayne takes a fall and comes when beckoned to be remounted.

El Dorado is resplendent with wonderful horses, but Wayne’s costar Robert Mitchum, portraying a drunken sheriff, doesn’t ride at all in the film. In real life, the actor was a fancier of the Quarter Horse breed. He began acquiring his own stock in 1960 and bred cutting horses on his Maryland farm until 1966, when he moved the horses to a ranch in Paso Robles, California. Although he later bred racing Quarter Horses, Mitchum kept some of his original cutting stock and rode his own buckskin, Bull’s Eye Bee (aka Buck), in the 1969 Westerns Young Billy Young and The Good Guys and the Bad Guys.

At near right, Old Grundy (Douglas Fowley) looks up to Marshall James Flagg, played by Robert Mitchum, who is riding his own Quarter Horse, Bull’s Eye Bee, in The Good Guys and the Bad Guys (1969).

Another superstar, Marlon Brando donned his spurs for 1966’s The Appaloosa. Brando plays the owner of Osaca, a prized Appaloosa stallion he plans to use as the foundation sire of a horse ranch. When Osaca is stolen by a ruthless Mexican bandit, Brando’s character, Fletcher, braves great danger to reclaim him.

Osaca was played by Cojo Rojo, a stallion originally from Lompoc, California, who had been retired from the racetrack to star in the film. Cojo Rojo was a bay with a spotted rump. Because the director, Sidney J. Furie, wanted a predominately black horse, presumably so he would be more striking on film, Cojo Rojo’s bay coloring was dyed black.

Although it took the star power of actor Kirk Douglas—in dual roles as feuding brothers—to garner international attention for 1982’s Australian production of The Man from Snowy River, it was the horse work that captivated the movie’s many fans. The movie, based on a poem by A. B. “Banjo” Paterson, was helmed by a Scottish-born television director named George Miller (not to be confused with the Australian director of Mad Max fame).

Young actor Tom Burlinson had little riding experience before being cast in the lead as Jim Craig, an eighteen-year-old who goes to work for wealthy rancher Harrison (Douglas) after his father is killed by a stampeding herd of brumbies, Australia’s wild horses. Burlinson trained intensely for six weeks with horse master Charlie Lovick. At first, the actor took lessons on the quiet, twenty-eight-year-old Cheeky. Once he mastered the basics, Burlinson rode the buckskin Denny, a mountain horse owned by Lovik’s father. Denny, making his movie debut in The Man from Snowy River, was Burlinson’s main mount. The bond he forged with the actor ahead of time during week-long trail safaris helped the two through the difficult production. “We were once eight days away,” said Burlinson, recalling one safari, “and there’s nothing like getting used to a horse in that time.”

As the more difficult riding scenes came toward the end of filming, Burlinson was able to hone his skills even more during production. “There were a couple of really dangerous stunts they wouldn’t let me try,” said the actor, “but I actually did do the ‘terrible descent’ after much convincing of the producers.” He is talking about the nearly vertical downhill run after the brumbies. Veteran Australian stuntman and wrangler Heath Harris was hired to help stage the memorable scene. Mounted on Denny’s stunt double, Burlinson followed Harris’s instructions, giving the horse rein and leaning back in the saddle like a pro. Although the filmmakers enhanced the breathtaking sequence by tilting the camera slightly, the actual incline was really quite steep. The duo made it to the bottom without mishap. Burlinson continued the rest of the lengthy chase, which concludes with his dramatic solo roundup of the wild horses aboard Denny. Said Burlinson at the end of the film, “I found great joy working with the horses, and I developed a great bond with the buckskin. I loved him.”

In addition to Charlie Lovick and Heath Harris, American trainer Denzil Cameron was contracted to train a young stallion owned by Douglas’s character in the film. The prized stallion, known from the poem as “the colt from old Regret,” was played by a black horse with a white muzzle. The stallion had been named Dollar in homage to John Wayne’s movie horse.

Superstar Kirk Douglas doesn’t do much riding in the film, but when he does it’s impressive. As Spur, a peg-legged gold miner, he drives a cart pulled by a flea-bitten gray. As Harrison, however, Douglas is mounted on a striking dark dappled gray and leads a pack of men on the hunt for his colt who has run off with the wild horses. Sixty-six at the time of filming, the regal actor looks every inch the star on the beautiful gray.

The Man from Snowy River’s “terrible descent,” executed by a stunt horse ridden by young actor Tom Burlinson.

A New Breed

In 1969, director George Roy Hill’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid ushered in a new breed of Western, presenting modern self-aware heroes—not unlike James Bond in cowboy boots. As Butch and Sundance, Paul Newman and Robert Redford are smart-aleck outlaws with sexy devil-may-care attitudes. Paul Newman rides a bay named Hud, the Thoroughbred son of Diamond Jet, star of 1966’s Smoky, while Robert Redford rides a chestnut gelding for most of the picture. Both horses were likely rented from the Fat Jones Stables in its last year of operation.

The film’s high-octane horse work is superb. In one scene, the arrival of the “super posse” tracking down Butch and Sundance sets a unique stunt in motion, one requiring their horses to make a running jump from a railroad car. The car was custom built, with the door opening 3 feet higher than usual so the stuntmen would not be decapitated on the way out. A ramp was built on the other side of the car to give the horses a running start and allow them to gallop through the car. The scene was shot with multiple cameras, including one buried beneath the open door to catch the jumps from below. With a price tag of $1,000 per jump for the stuntmen and their horses, director George Roy Hill wanted to be sure he covered the sequence only once.

Filmed away from the American Humane Association’s watchful eye, and during a time when studio compliance with animal-safety guidelines was voluntary at best, some of the stunts were extra-risky. On location in Mexico, a white mule was rigged with a Running W for a scene in which she was tied to a brown horse and Butch (Paul Newman and his stunt double Jim Arnett) hides between the two animals as they run. The mule does a painful looking nosedive into the dirt but fortunately was not seriously harmed.

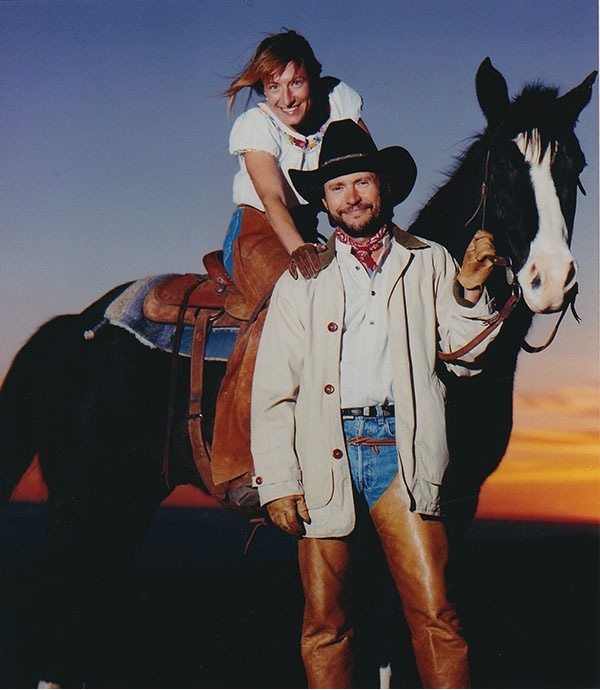

A decade later, Redford teamed up with director Sydney Pollack and wrangler Ken Lee for a Western set in more contemporary times. The Electric Horseman (1979) features a horse in a pivotal role. Redford stars as Sonny Steele, former rodeo champion turned breakfast cereal pitchman. His sidekick in the ad campaign is Rising Star, a million-dollar Triple Crown-winning stallion. Disillusioned by corporate greed, Steele kidnaps Rising Star to protest the stallion’s exploitation during a Las Vegas sales convention. Going AWOL from the convention, Steele, ridiculously resplendent in a garish purple cowboy outfit, glittering with twinkling lights, rides Rising Star through a crowded casino and outside onto the neon night street. The stallion’s tack is also lit up like a Christmas tree. The entire electric ensemble, powered by a battery pack hidden in the saddle, cost $35,000.

With journalist Hallie Martin (Jane Fonda) tagging along, Steele and Rising Star go on the run. In the final sequence, Steele releases the stallion to join a band of wild horses, reclaiming his own dignity and freedom in the process. The stirring sight of the beautiful blood bay stallion running free at last is a guaranteed lump in the throat. To make sure the stallion could be caught after filming the scene, a mare in heat was tied to an off-camera tree. Wranglers snatched the ardent stallion before romance could develop.

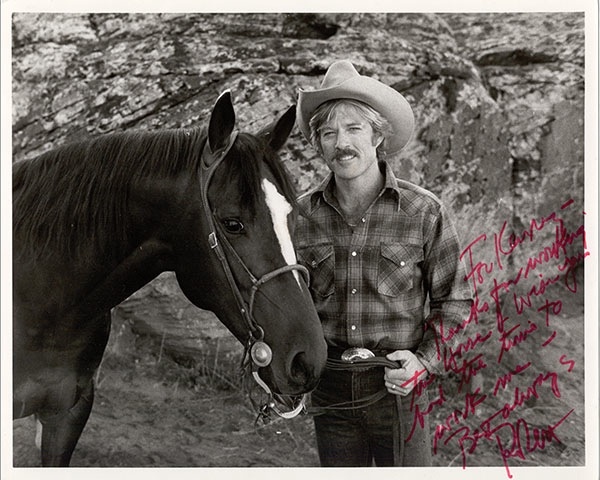

The character of Rising Star was played by Let’s Merge, a five-year-old Thoroughbred sired by racehorse Urge to Merge. He was purchased at a Pomona, California, auction as a yearling by dressage trainer Barbara Parkening of Burbank. She renamed him High Country and put him in dressage training. When Parkening learned wrangler Lee was looking for a stallion to play a racehorse, she knew High Country could do the job. Nicknamed High C by the production company, the stallion was given to Robert Redford after the film and retired to his ranch in Sundance, Utah.

Three years before The Electric Horseman, Paul Newman had saddled up to play Buffalo Bill Cody in Robert Altman’s Western comedy Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson (1976). As Cody, Newman rode a white Lippizan named Pluto from Washington State. Wrangler John Scott was in charge of the horse work. A former rodeo contender from Alberta, Canada, Scott had gotten his start in movies as a riding extra in director Arthur Penn’s acclaimed historical Western Little Big Man (1970), which starred Dustin Hoffman.

Robert Redford autographed this photograph, thanking The Electric Horseman horse trainer Ken Lee.

Action Directors Take the Reins

The same year Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid rode into movie theaters, Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch exploded on the big screen. With its own band of cocky heroes and masterfully staged stunts, The Wild Bunch utilized horses for maximum visual impact. Later, director Peckinpah teamed with superstar Steve McQueen to tell the story of an aging rodeo champion in 1972’s Junior Bonner, set largely at a rodeo in Prescott, Arizona. The horse action was coordinated by two-time All-Around World Champion Cowboy rodeo star Casey Tibbs. Ken Lee was credited as “ramrod”—a term borrowed from cattle drives to describe the outfit’s boss. In the film’s most lighthearted sequence, McQueen and his movie father, Ace Bonner (Robert Preston), ride double on Junior’s roan horse in the rodeo parade. Breaking away from the crowd, they go on a wild romp though backyards. Although the big stocking-legged roan with a T-shaped wide blaze doesn’t even have a name in the movie, he was a more important supporting character than some of the humans who received screen credit.

The roan was Ken Lee’s own Quarter Horse, Pie—not to be confused with Jimmy Stewart’s favorite movie mount. Purchased as a five-year-old, the gelding was just a good all-around saddle horse, gentle enough for Lee’s children to ride. Another of Ken Lee’s own horses, Soldier, doubled Pie in his big scene, jumping large obstacles. Pie had previously appeared in the 1968 Sydney Pollack Western The Scalphunters, starring Burt Lancaster. Pie died prematurely from complications of colic while on hiatus from movie work. It was a great loss for the Lee family as Pie was not only a great movie horse but also a beloved pet.

Nearly a decade later, director Walter Hill brought the story of the James Gang to the screen, casting real-life brothers as the legendary outlaw brothers. The Long Riders, released in 1980, starred James and Stacy Keach as Jesse and Frank James; David, Keith, and Robert Carradine as Cole, Jim, and Bob Younger, and Dennis and Randy Quaid as Ed and Clell Miller. Although authentic in its period detail, the film is a departure from staid Westerns of yesteryear, largely because of its stylish staging, hip Ry Cooder soundtrack, and crisply choreographed action—which included some dangerous stunts. Although one horse was clearly trip-wired for a dramatic solo somersault in the middle of a street, no injuries were reported.

Hell-bent for trouble, The Long Riders, LED BY James Keach, Stacy Keach, and Robert Carradine, thunder through town on their wild-eyed black horses.

One of the film’s most spectacular sequences is a slow-motion shot of the gang jumping their horses through plate glass windows—twice—as they escape through a building. Wrangler Jimmy Sherwood, who worked with head wrangler Jimmy Medearis, spent six weeks prepping the horses to build their confidence. They were trained to jump in tandem over low obstacles. To get them used to something hitting their bodies as they ran, the horses were run through tape strung between posts. They practiced jumping through the windows without glass and finally did the shots, jumping through candy glass. All the main movie horses were shipped to the South Carolina location from veteran wrangler Rudy Ugland’s California ranch. Because Hill wanted the gang’s horses to be uniformly and dramatically black, they were dyed to match one another.

Rudy Ugland served as head wrangler on Walter Hill’s Geronimo: An American Legend (1993). Gene Hackman, Robert Duvall, Jason Patric, and Matt Damon costarred, proving once again that great actors love to play movie cowboys. Matt Damon rode the sorrel gelding 101, named after the famous old Miller Brothers 101 Ranch. Gene Hackman rode a mule named Susie, who had made her movie debut in Dances with Wolves. Robert Duvall, who Rudy Ugland said is “probably the best rider of all the actors I ever mounted on a horse,” rode the sorrel Quarter Horse gelding Gino, a veteran of many films.

In the title role of Geronimo, Wes Studi rode one of Ugland’s own horses, Ajax, a white trained rearing horse. Because of his ultra-sensitive mouth, Ajax could inadvertently be pulled into a rear by a heavy-handed rider. Studi, however, had very light hands and impressed Ugland with his excellent horsemanship. Ajax had previously appeared as Gregory Peck’s mount in 1989’s Old Gringo. After Geronimo, Ajax continued to work in commercials and television movies. In his later years, he was, like many light-colored horses, vulnerable to skin cancer. Sadly, he was put down because of complications from the disease in 2003, at age twenty-three.

In 2004, Walter Hill directed the pilot episode of HBO’s series Deadwood, featuring Keith Carradine as Wild Bill Hickok. The horses for Deadwood came from Jack Lilley’s Movin’ On Livestock in Canyon Country, California. The series went on to great success, employing scores of horses who lent Western authenticity to the drama.

Hill’s most recent foray into the Old West was producing and directing the AMC television mini-series Broken Trail (2006), starring Robert Duvall and Thomas Haden Church as cowboys driving a herd of mustangs for sale. Canadian Dusty Bews supplied the horses and did a superb job wrangling not just the actors’ mounts but the “wild” herd.

Meeting the Western Challenge

Horses are integral to the plot in director Lawrence Kasdan’s slickly produced 1985 homage to the Western, Silverado. The very first sound in the movie is a horse’s soft nicker, which signals the imminent attack of vengeful villains on the sleeping hero, Emmett, played by Scott Glenn. Soon Emmett is on the trail, mounted on a husky dapple gray and ponying a bay tobiano pinto left behind by the villains. His mission is to find his brother, then join his sister in the town of Silverado. En route, he revives the nearly dead Paden (Kevin Kline), who has been robbed of everything except his red long underwear. Paden confesses that all he really cares about is recovering his stolen bay horse. Joining forces with Emmet, Paden soon recovers his bay and expresses his affection for the horse by kissing him on the mouth.

Paden lands in jail, where Emmett’s brother Jake (Kevin Costner) awaits hanging after an unjust trial. Paden and Jake engineer a clever escape, and soon Paden and the brothers are galloping off on the gray, the bay, and the pinto. The bay, however, changes from scene to scene. The first horse has a narrow blaze, another has a star and a white muzzle, and a third has a wider blaze. According to wrangler Ken Lee, the main cast horse had weak knees so although he was gentle enough to work with Kevin Kline in the “love” scene, he was not strong enough for the galloping sequences. The other two bays were doubles, and apparently director Kasdan assumed the action was so fast that no one would notice the different face markings.

A fourth man, Mal (Danny Glover), joins the heroes; he rides a big blaze-faced sorrel. All the cast horses, with the exception of the pinto and the big gray Quarter Horse ridden by Scott Glenn, were supplied by Corky Randall. The gray was a calf-roping horse owned by a wrangler from Oklahoma. The pinto was a veteran movie horse owned by supplier Denny Allen. Another pinto, Tarzan, also appeared. The most stunning stunt in Silverado occurs in the final gun battle, when Emmett, disarmed, uses the gray to leap out of a barn on top of his nemesis, who is killed.

Lawrence Kasdan returned to the Old West for 1994’s Wyatt Earp, starring Kevin Costner. Head wrangler Rusty Hendrickson provided the horses. Wyatt Earp rode many horses over the course of his life in the film, but when Earp achieved legend status, Costner rode Baby, a registered Paint red roan with a blaze, a long, narrow body, a good mind, and smooth gaits. Hendrickson originally purchased Baby as a colt for Dances with Wolves and worked with him for four years to turn him into an ideal cast mount for Costner in Wyatt Earp.

The camera captures a stunt with the gray from Oklahoma in Silverado (1985).

Dancing with Costner

Rusty Hendrickson learned about horses from his dad, a rodeo contractor and racehorse trainer. Veteran wrangler Rudy Ugland handpicked Hendrickson as his protégé after working with him on the controversial Heaven’s Gate in 1980. After learning the ropes and toiling uncredited on many films, Hendrickson finally became a head wrangler on 1990’s Dances with Wolves.

Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves won a Best Picture Award for its producer-director-star. The first Western to receive the honor since 1930’s Cimarron, it also marked a victory for its equine star, the buckskin Quarter Horse Plain Justin Bar, who played Cisco. For the first time in many years, a horse received billing in the end credits, albeit next to last, just above Teddy and Buck who played the wolf, Two Socks. A strong character in the film, Cisco bonds with Costner’s character, Lt. John Dunbar, who spends much of his time without human companionship.

Costner definitely wanted a buckskin for Cisco. After looking at a number of them, Hendrickson finally found the right gelding, bred by Amy Jo and Earl Udy Warren of Heyburn, Idaho. Sired by Impressive Dan, out of Plain Pearl Bar, and foaled on May 1, 1983, Plain Justin Bar was chosen for his color, conformation, and temperament. “He had a certain presence,” Hendrickson later recalled. “He was interested in people and not afraid of things.” A soft-spoken cowboy of John Wayne proportions, Hendrickson approaches training movie horses just as he does his ranch horses—with gentleness and common sense. The result is a good all-around horse who, in Plain Justin Bar’s case, just happens to be a movie star. After production, the handsome gelding was sold to a private party in Pilot Point, Texas.

As Kicking Bird, Graham Greene rode a pure white Indian pony with blue eyes. The choice was inspired by a poster of a Lakota chief Kevin Costner gave Rusty Hendrickson. In general, blue-eyed horses don’t make good movie horses as their eyes can’t handle the lights for very long. Fortunately, this particular horse did not have to stand for many close-ups so he was fine. He was purchased from a South Dakota man with the proviso that the owner could buy his horse back at the end of the movie. After his brief career in show business, the distinctive white horse was returned to his original owner.

Kicking Bird’s white Indian pony and Cisco appear to be listening for trouble sneaking up from behind in this shot from Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves (1990).

Eastwood Goes West

After making a name for himself as a mysterious loner in Sergio Leone’s ultra-violent Italian “spaghetti Westerns,” Clint Eastwood returned to Hollywood to star in Hang ’Em High (1967). Departing from his tough-guy image to appear in the movie version of the hit Western musical Paint Your Wagon (1969), a throwback to more naïve times, Eastwood went on to contribute a fistful of Westerns as both star and director. High Plains Drifter (1973), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), Bronco Billy (1980), and Pale Rider (1985) all helped keep the genre—and the Western movie horse—alive.

Eastwood’s mount in The Outlaw Josey Wales was a well-bred Quarter Horse stallion called Parsons. The stallion had originally been purchased by wrangler Rudy Ugland to play Tom Mix’s horse Tony in a film about the silent star. Parsons, a sorrel with a blaze and stockings like Tony’s, was taught all the tricks necessary to play the famous horse. Although the Mix film never happened, Parsons would go on to be ridden by some of the world’s greatest movie stars. After working with Eastwood, he was Jane Fonda’s mount in 1978’s Comes a Horseman. Steve McQueen rode Parsons in 1979’s Tom Horn. After appearing in many more films, Parsons—who was gelded after his role in The Outlaw Josey Wales—was retired to Ugland’s California ranch.

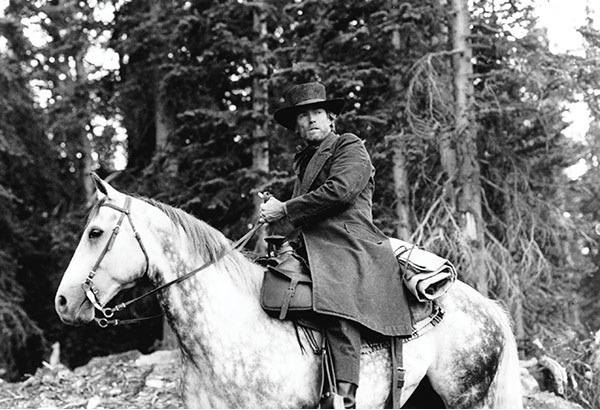

In Pale Rider, Eastwood plays Preacher, a sort of avenging angel-gunfighter. Symbolizing both good and evil with his dramatic light and dark coloring, Preacher’s mount is a beautiful dappled gray. Eastwood told wrangler Jay Fishburn, a former jockey, that he wanted the specifically colored horse to have “a lot of star quality.” Fishburn found the striking young gelding For the Moment at a Los Angeles-area racetrack. Fishburn’s friend Spud Proctor, a track outrider, was using the gelding to lead the horses to the starting gate. Although he had never worked in a movie, the gray had the requisite coloring and charisma. After working with the gelding for a few weeks, Fishburn knew For the Moment also had the right temperament. When filming wrapped, the gray resumed his career as a racetrack lead pony.

As Will Munny, a repentant gunfighter lured back into action, Clint Eastwood rides a less glamorous gray in Unforgiven (1992), a dark, gritty film about violence that won the Best Picture Academy Award for its producer-director-star. This time, Eastwood specifically wanted a flea-bitten gray to match his character’s over-the-hill demeanor. Wrangler John Scott looked long and hard for the right horse and finally found a little gelding named Jerry on the Hobem Indian reservation in Alberta, Canada. Two doubles were also acquired. All the grays were what Scott calls cold-blooded horses of no particular pedigree and thus met Eastwood’s desire to create an unromantic image for himself. The film’s only levity comes from a running gag of the rusty Will having difficulty mounting his equally rusty old horse. After filming, Jerry found a good home as a lesson horse.

For the Moment’s dark-and-light coloring reflects the dual nature of Clint Eastwood’s Preacher in 1985’s Pale Rider.

Eastwood chose the flea-bitten gray Jerry to subtly underscore his Unforgiven character’s well-worn appearance.

Best-Sellers Mount Up

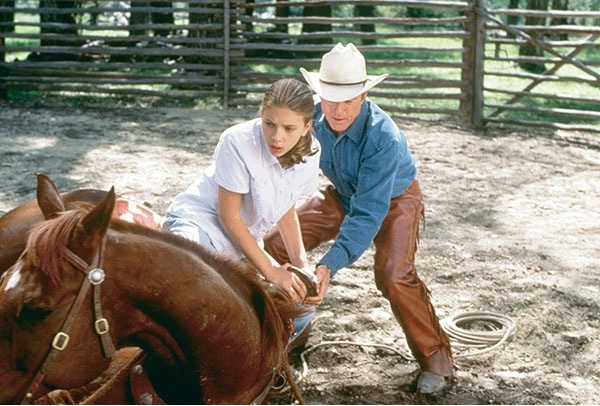

Robert Redford’s adaptation of the best-selling book by Nicholas Evans The Horse Whisperer (1998) featured seventeen American Quarter Horses provided by trainers Rex Peterson and Buck Brannaman. In addition to Peterson’s accomplished horse, Hightower, as the lead horse Pilgrim, four others were used as doubles. Top Decker Special, Whynotcash, Sierra Ghost, and Maverick all played Pilgrim during different phases of his healing process in the movie. Hightower was in the initial accident scene, the close scenes with Redford, and the final scene when Grace (Scarlett Johansson) regains her confidence to ride Pilgrim again. Peterson’s black stallion, Doc’s Keepin Time (aka Justin), played Gulliver, the horse killed in the truck accident. Robert Redford’s mount, called Rimrock in the film, was played by Rambo Roman, one of Buck Brannaman’s own horses.

In 2000, Miramax Films and Columbia Pictures released All the Pretty Horses, directed by Billy Bob Thornton and starring Matt Damon as John Grady Cole. In the screen adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s popular book, the story focuses on the adventures of the Texas teenager John Grady and his friend Lacey Rawlins (Henry Thomas), who are hired to break mustangs on a Mexican hacienda. Grady falls in love with the ranch owner’s daughter, Alejandra (Penelope Cruz), an excellent equestrienne. Their star-crossed romance is the centerpiece of the movie, yet horses play significant roles throughout.

Head wrangler Rusty Hendrickson provided his own saddle horse, Dollar, for Matt Damon’s mount, Redbo. In 1983, Hendrickson bought the sorrel Quarter Horse gelding, registered as Cutter Bailey, as a yearling in Montana. Dollar’s experience as Hendrickson’s ranch horse made him perfect for the role of Redbo.

Another of Hendrickson’s Quarter Horses, Ghost, is the gray ridden by Henry Thomas and called Junior in the film. A third horse was needed as a mount for Lucas Black, who plays the misfit thirteen-year-old Jimmy Blevins. After looking at Saddlebreds, Thoroughbreds, and Walking Horses, Hendrickson chose a charismatic little bay Quarter Horse who appealed to director Thornton.

Matt Damon, Henry Thomas, Penelope Cruz, and Lucas Black trained for five weeks on horseback before shooting began in Texas. Working with Hendrickson and wranglers Rex Peterson and Monty Stuart, the actors spent eight hours a day in the saddle. They also learned to care for their mounts and did their own saddling, unsaddling, and grooming. The hard work paid off: the actors look completely at ease on and around their movie mounts, about whom Matt Damon has said, “They’re better actors than we are. They’ve been in lots of movies and nothing ruffles them.”

After laying Pilgrim (Hightower) down, Tom Booker (Robert Redford) aids Grace MacLean (Scarlett Johansson) in mounting her horse for the first time since their traumatic accident in The Horse Whisperer (1998).

Young Guns Ride

More than a decade earlier, another group of Hollywood’s hottest young actors had also learned to ride for 1988’s Young Guns. Working with wrangler Jack Lilley, Emilio Estevez, Keifer Sutherland, Lou Diamond Phillips, Charlie Sheen, Dermot Mulroney, and Casey Siemaszko were transformed into a hard-riding band of outlaws. As Billy the Kid, Estevez survived to appear in the 1990 sequel, Young Guns II, along with Kiefer Sutherland as “Doc” Scurlock, Lou Diamond Phillips as Jose Chavez y Chavez, and new gang member Christian Slater as Arkansas Dave Rudabaugh. With sexy young actors, rock-and-roll soundtracks, fast-paced action, and clever dialogue by screenwriter-executive producer John Fusco, the Young Guns movies introduced the Western to a new generation of filmgoers. The horse action in both films is excellent and features registered Quarter Horses owned by Jack Lilley as cast mounts and many trained falling horses.

In Young Guns, Jack Palance, playing the villain Murphy, was assigned to a frisky horse who made it difficult for the then seventy-one-year-old actor to hit his marks and deliver his lines properly. Palance requested another horse, Tarzan, a sorrel tobiano Paint gelding on the picket line that had caught his eye. Owned by Derwood Herring of Clovis, New Mexico, where the film was shot, Tarzan had previously worked in Silverado and 1986’s Western spoof Three Amigos! The gentle veteran equine actor was brought to the set for the actor, who had no further horse trouble.

John Fusco and his wife, Richela, were also attracted by Tarzan’s striking looks and obvious intelligence. They took turns riding him between set-ups and were so smitten that they ended up purchasing him. Renamed Chato, he accompanied the Fuscos to their Vermont farm after filming wrapped. John Fusco intended to retire Chato from movie work, but the gelding was called back into action when Young Guns II was produced. In that film, Chato plays the horse who flamboyant brothel owner Jane Greathouse (Jenny Wright) rides nude, à la Lady Godiva, when do-gooders force her out of town. Twenty-three in 2005, Chato was still going strong, ruling the Fusco farm. Another of Fusco’s horses, the sorrel overo Paint mare Wakaya, played the Spirit Horse in Young Guns II.

Billy Crystal and Beechnut

Jack Lilley also provided horses for the comedic contemporary Western City Slickers (1991). Billy Crystal’s blaze-faced black horse, the 15-hand Beechnut, was about eleven years old when Lilley leased him from Oregon breeder Frank Russell for the movie. Surprisingly, Beechnut’s dam was a sorrel and white overo pinto mare. As a colt, Beechnut had been a gift for Frank’s young son Charley. Named Charley’s Surprise, the horse acquired his nickname, Beechnut, from a brand of chewing tobacco. He grew up a ranch horse, used for roping and gathering cattle, and was unfazed by the distractions of a movie set.

Beechnut’s main double for the chase scenes was Licorice, a black roping and cutting Quarter Horse. Jerry Gatlin along with Jack Lilley and his son Clay taught Billy Crystal how to ride and rope. A natural athlete with great hand-eye coordination, Crystal roped the first steer he tried.

The actor was so pleased with Beechnut in the first movie that he purchased him from the Russells. He wanted to ride him in 1994’s City Slickers II. To make it appear that Crystal was on a new mount, Beechnut’s white blaze was dyed black.

When hosting the sixty-third-annual Academy Awards in 1991, Crystal made his grand entrance riding Beechnut on stage, sending up the year’s big winner, Dances with Wolves. Horse trainer Lisa Brown, who had looked after Beechnut since City Slickers, spent three days prepping him for his Oscars appearance. Unlike most of the stars on the stage, the horse did not require any special makeup: his ears were left untrimmed and his hooves were dressed with clear oil, not hoof black. Crystal wanted Beechnut to look like the real ranch horse he was.

Beechnut was retired to an idyllic boarding ranch in Malibu to spend his golden years cruising around a large pasture with a bunch of good old horse buddies. He continued to be cared for by Lisa Brown, who has worked with many celebrity clients. She assisted wrangler Rusty Hendrickson on Seabiscuit (2003) and trainer Rex Peterson on Hidalgo (2004) and said, “I’m always thankful to share time with the glorious movie horse whose character is unmatched.”

City slicker Billy Crystal with Beechnut and trainer Lisa Brown.

With his backstage pass for the sixty-third Academy Awards around his neck, Beechnut gets his hooves painted with oil before his grand entrance with Billy Crystal at the gala event.

Far East Meets West—in the South

Chinese born director Ang Lee has proven himself adept in a variety of genres. His Civil War-era Western Ride with the Devil (1999) starred Tobey Maguire as Jake Roedel, a young man who joins the Southern loyalist Bushwackers after Union soldiers murder the father of his friend Jack Bull (Skeet Ulrich). Pounding hoofbeats fill the soundtrack in the opening moments, signaling plenty of hard riding to come.

Head wrangler Rusty Hendrickson’s horse Dollar, the gelding Matt Damon rode in All the Pretty Horses, is Skeet Ulrich’s mount. Tobey Maguire rides a bald-faced sorrel gelding named Blaze for most of the film. A former falling horse, the Arab/Quarter Horse cross was reportedly a handful in his youth. A veteran of many films, Blaze has since mellowed into a good all-around horse. Hendrickson coached Maguire, who did all his own riding in the film. According to Hendrickson, the star proved to be an excellent student. He looks completely at home galloping Blaze. As the budget was tight, horses had to do double duty, and Blaze even did some falls in the battle scenes. He was deservedly retired after the movie.

Another falling horse used in the battle sequences was Paint That Ain’t, a solid sorrel registered Paint gelding owned by Mark Warrack, Hendrickson’s longtime assistant wrangler. In addition to the veteran movie riders and stunt horses, Civil War reenactors and their horses were hired for the battle scenes. Filmmakers commonly use reenactors in historical movies, as they provide authentic knowledge and have their own period wardrobes—for themselves as well as their horses.

The Hoofbeats Go On

Thirteen years after Dances with Wolves, Kevin Costner directed another critically acclaimed Western, Open Range (2003). Starring Costner, Robert Duvall, and Diego Luna, Open Range follows two cattlemen, pushing a herd westward in the 1880s, who encounter opposition from a land baron.

In Open Range, horses are relegated to typical supporting roles, mostly as vehicles for driving and rounding up cattle and as mounts in gunfights. They also pull wagons and provide colorful atmosphere just milling around in the background of dialogue scenes.

Costner, Duvall, and Luna rode the same horses throughout the film. Although Rusty Hendrickson did not work on the film, he provided Costner with his mount. The star called his buddy Hendrickson and asked if he could find a horse like Baby, the horse Costner had ridden in Wyatt Earp. Hendrickson suggested he just ride Baby, by then in his early teens but still in great shape. Hendrickson shipped Baby from his Montana ranch to the Canadian location, and Costner was happily reunited with his former costar. Duvall and Luna rode two other veteran movie mounts, Apache and Soldier.

The horse work in Open Range was carefully monitored by the AHA, and trained stunt horses were used throughout the film. In one scene, a horse appears to be struggling to get up after being shot. The horse, named Red, was a trained “lay down” horse. After Red was laid gently down on softened ground, he was cued to get up, then cued to lie back down so he would appear to be struggling.

Kevin Costner and Baby, his favorite mount from Wyatt Earp, push cattle through a river in the 2003 film Open Range.

Remembering the Alamo

Back in 1960, John Wayne produced, directed, and starred as Davy Crockett in The Alamo, an epic Western about the historical battle for Texan independence that ends with the brutal massacre of the defenders of the Alamo fort by Mexican soldiers. The film is best remembered for its action sequences, with plenty of stunt horses.

Forty-four years later, director John Lee Hancock’s version of The Alamo (2004) was released. Starring Dennis Quaid as General Sam Houston, Billy Bob Thornton as Davy Crockett, and Jason Patric as James Bowie, the film had more than a million dollars budgeted for the horse unit. Wrangler Curtis Akin, a native Texan, was presented with the awesome challenge of finding all the main cast horses, stunt horses, and legions of army mounts. In all there were more than two hundred horses on the film, including more than fifty driving horses. Many were rodeo and ranch horses culled from spreads near the Texas location. Forty reenactors from the San Antonio Living History group were hired, along with their horses, as extras.

Curtis Akin had much of the period tack replicated for The Alamo. Carrico Leather in Kansas crafted thirty-two cavalry saddles, including a Santa Fe Hope saddle for General Houston (Quaid). Texas saddlemaker and reenactor Calvin Allen made a $12,000 replica of General Santa Anna’s gorgeous saddle, complete with a carved lion’s head saddle horn.

As General Houston, Dennis Quaid rode a registered American White named Paris. Trained to rear and fall, Paris is owned by the Anderson family of the Texas White Horse Ranch, which has more than thirty white horses. Ringo, an Arabian/Quarter Horse cross, doubled Paris. Jason Patric’s mount was a ranch horse called Gunsmoke, owned by Robert Blanford and world-champion barrel racer Kay Blanford. Mexican actor Emilio Echevarria, who plays General Santa Anna, rode the black Quarter Horse stallion, Ima Bed of Cash. The grandson of the famous racing Quarter Horse, Dash for Cash, the stallion had a brief racing career before being purchased by the Bonita Ranch in Stephenville, Texas. Curtis Akin tried him out at a youth rodeo and was impressed by the beautiful stallion’s quiet temperament. “He looks like a million dollars, and you can put your baby on him,” said Akin in a 2003 interview. “You need that kind of mentality. You want something that if a bomb blows up next to him he’s not going to go to pieces.” Cash only had to get used to having a camera crane overhead; once he stopped looking and snorting at the strange beast, he was ready for “Action!”

All the horses used in the battle sequences were equipped with earplugs to deaden the noise of cannon shots and gunfire. Since the temperatures on location often soared into the mid-90s, wranglers made sure the horses were well watered and kept on shaded picket lines when not on camera. The horses were quartered at “Wranglerville,” where Akin and his team of sixty, including several world champion rodeo stars, were housed during the filming. Akin and his crew ran what he calls a boot camp at Wranglerville, schooling the actors for two hours a day to fine-tune their riding skills.

Paris adds good guy charisma to Dennis Quaid’s General Houston.

A Woman’s Place Is in a Western

With some marvelous exceptions, such as Barbara Stanwyk as a lady rustler in 1955’s The Maverick Queen, women have usually been relegated to background or, at best, supporting roles in big-screen Westerns. However, Australian actress Cate Blanchett gives a tour-de-force lead performance as a stoic frontier doctor in The Missing (2003). Directed by Ron Howard, the film concerns the hunt for the kidnapped daughter of Maggie Gilkeson (Blanchett), who grudgingly joins forces with her long-estranged father, Samuel Jones, played by Tommy Lee Jones. The film is completely dependent on horses as Maggie and Samuel saddle up to track her daughter’s mounted abductors. Director Howard told head wrangler Tim Carroll that he wanted authentic-looking horses—not slickly groomed animals ready for the show ring. Carroll cast the lead mounts from his own movie-horse ranch in Abiquiu, New Mexico. The trainer is a big believer in taking his colts on film sets, even before they are weaned, to get them used to the commotion. By the time they are ready to be ridden, they are already movie horses.

Cate Blanchett—who had previously only ridden English, but proved to be an excellent western rider—was mounted on the brown gelding Magnum, a Quarter Horse type Carroll had raised from a colt. Magnum was doubled by his exact look-alike Jingles. The actress had difficulty telling them apart until she started riding: Magnum’s gaits were smoother. As Maggie, Blanchett is required to pony a packhorse. A mustang falling horse named Fred Red was used as he kept pace with the lead horse and would not put any stress on the actress’s arm. “If the actors worry about their horses,” reasons Carroll, “they can’t do their job, which is acting.”

Tommy Lee Jones rode the solid black eleven-year-old gelding Jamaica, a somewhat common-headed fellow Carroll calls simply a “good old horse.” As Maggie’s youngest daughter Dot, Jenna Boyd rode the bay Little Duke, a well-broke kids’ horse doubled by Josh. As the kidnapped Lily, Evan Rachel Wood rode another solid movie mount named Joe.

Although horses are treated without sentiment by the film’s characters, the filmmakers took great pains to ensure their safety in the many intense action scenes. In addition to trained stunt horses, many cinematic tricks were utilized to create suspense and drama. In one scene, a falling boulder spooks a horse during a flash flood. He rears and unseats his rider, a young girl, as the waters rise. Stunt double Julie Adair rode Carroll’s stunt horse, Ninja. A fake rock made of Styrofoam was used, and tanker trucks pumping water regulated the “flood” level so it never rose above the horses’ knees. In another scene, a flaming arrow hits a saddle during an Indian attack. The arrow, guided by a cable, never threatened the horse, and the computer-generated flame was added in the editing room: modern movie magic.

True Grit Rides Again

Joel and Ethan Coen’s 2010 remake of the John Wayne starrer True Grit features Jeff Bridges in the role of the one-eyed, alcoholic Federal Marshall Rooster Cogburn. Head wrangler Rusty Hendrickson’s Quarter Horse Apollo, a sorrel with a star and wide stripe and rear white stockings, is his mount. Similar in appearance to Wayne’s horse, Dollor, the handsome Apollo was bred to be a halter horse—one that competes in classes judged solely on good conformation and manners. Hendrickson originally purchased him for his son Scout, who is now a wrangler and stuntman on his father’s crew. Hendrickson describes Apollo simply as just a “big, quiet, gentle horse”—a perfect horse, in other words, to carry a movie star like Bridges in style. In a scene where Cogburn’s horse is shot, Apollo was doubled by Wonderbread, a trained falling horse owned by Monty Stuart who doubled Bridges for the stunt. Apollo did the lay down in the second part of the sequence, when Cogburn is pinned under the fallen horse.

Most of the horse action in True Grit is routine western fare, straightforward riding. In order to add visual interest, a red roan Appaloosa named Cowboy was chosen as the mount of Texas Ranger LaBoeuf (Matt Damon). The real horse star of the film is Little Blackie, the horse chosen by heroine Mattie Ross (Hailee Steinfeld) from a string of mustang ponies bought by her late father. Hendrickson’s black horses, Ribbon and Cimarron, portrayed Little Blackie. The more spirited and refined looking of the two, Ribbon previously starred in 2006’s Flicka. He is the horse in Little Blackie’s introductory scenes, when he is first chosen by Mattie. Cimarron, a quieter, sturdier Quarter Horse, was originally purchased to double Ribbon in 2007’s 3:10 to Yuma.

The most complicated horse work in the film comes early on, when Mattie, who has engaged Cogburn to pursue her father’s killer, swims Little Blackie across a wide river in pursuit of the Marshall, who has teamed up with LaBoeuf to collect a bounty on the murderer. Hendrickson and his crew originally attempted to prepare four horses for the challenging swim, but only two were willing and able swimmers: Ribbon and Cimarron.

The sequence took weeks of preparation. First, the river was cleared of any rocks and debris that could pose safety hazards. A ramp with cleats was built on the landing side as the underwater bank was too steep to allow purchase. Each horse swam back and forth across the river several times during filming as there was no other way across the water. Apollo and Cowboy who, along with Cogburn and LaBoeuf, appear to have made the trip across by ferry, were actually trucked four hours to the location on the opposite side of the river. Four safety boats were positioned near the action in case anything went wrong, but fortunately they were not needed. Stuntwoman Cassidy Vick-Hice doubled actress Hailee Steinfeld in the swimming scene. For close-ups with the young actress, a mechanical horse was used. Real horses move around quite a bit while swimming in such deep water, and the mechanical horse was much safer for the actress to hold on to during the close camera work.

Near the end of the movie, Mattie is bitten by a rattlesnake. Cogburn saves her life by hoisting her across his saddle on Little Blackie and galloping through the night to the nearest outpost. It is a gut-wrenching sequence, with Little Blackie literally galloping his heart out, until he can run no longer and drops to the ground. To spare the horse a prolonged death, Cogburn finishes him with a shot before carrying Mattie the rest of the way. The sequence was filmed with both hero horses over a period of three months in various locations with different terrains. The horses were sprayed with a mixture of water and horse shampoo to appear sweat-soaked, and their breathing was enhanced to sound labored on the soundtrack. A mechanical horse attached to a camera car was ridden by the actors during their close-ups.

Filmed in separate phases, both Ribbon and Cimarron convincingly portray the valiant Little Blackie as he drops to the ground. The final portion of the sequence, when Rooster Cogburn puts the suffering horse out of his misery, was filmed on a soundstage. In reality, no horses were harmed, and Ed Lish, the American Humane Association’s representative on the set, gives the production a “Ten, absolutely a ten,” for the great care taken to protect the horses in True Grit.

Cinematographer Roger Deakins focuses on actress Hailee Steinfeld as she swims the river on a mechanical horse in the Coen brothers’ version of True Grit.

Cut to: Hailee Steinfeld’s stunt double Cassidy Vick-Hice coming out of the river on Ribbon, one of the two horses who played Little Blackie.

Tarantino Pays Tribute in Django Unchained

Quentin Tarantino won 2013’s Academy Award for his original screenplay of Django Unchained, a rollicking, blood-soaked indictment of slavery presented as a spoof of spaghetti Westerns set in the pre-Civil War American South, circa 1858. Known for referencing classic films both verbally and visually in his movies, Tarantino worked in some wonderfully fun and sly references involving horses to delight diehard aficionados.

Dentist-turned-bounty-hunter King Shultz (Christoph Waltz) liberates a slave named Django (Jamie Foxx)—a reference to the spaghetti-Western character made famous by Franco Nero—and teaches him the trade of killing wanted men for money. Shultz first appears on screen in his rickety wagon topped by a bobbling oversized replica of a molar. The wagon is pulled by a little black horse he introduces to slave traders as “Fritz.” Fritz obligingly responds to his name with a nod and a snort, a trick he repeats in the film when, teamed up with Django, Shultz introduces both their horses as “Tony” and “Fritz.” The reference is to the two most famous horses of the early silent film era, rugged cowboy star William S. Hart’s Fritz and the flamboyant Tom Mix’s Tony.

Jamie FoxX, left, as Django on his mare Cheetah, who plays Tony, and Christopher Waltz as King Shultz on Ribbon who plays Fritz, in Django Unchained.

The original Fritz was a distinctive Paint so the similarity of Shultz’s Fritz to Hart’s horse is in name only. Two of head wrangler Rusty Hendrickson’s seasoned movie horses portrayed Fritz: Cimarron, who mostly pulled the wagon, and Ribbon, who served as Shultz’s riding horse once the wagon is dispatched. Ribbon previously worked as Little Blackie in the Coen brothers’ 2010 remake of True Grit and was Russell Crowe’s main mount in James Mangold’s 2007 remake of the 1957 Glenn Ford vehicle, 3:10 to Yuma. He also starred as Flicka, in the eponymously titled 2006 remake of 1943’s My Friend Flicka. Hendrickson originally rescued Ribbon from a trip to the slaughterhouse. The traumatized horse had a violent streak, which Hendrickson eradicated with patient training. His painstaking effort paid off as Ribbon would soon become one of the most versatile equine thespians.

Tom Mix’s Tony was chestnut with a white blaze and stockings. That Django’s Tony is similarly colored adds a bit of authenticity to the reference. Jamie Foxx mostly rode his own mare, a Quarter Horse named Cheetah, in the film. Described by Rusty Hendrickson as “very athletic,” with “good balance,” Cheetah had not worked on a movie before and needed to get used to all the unusual sights and sounds on the set. Wrangler Mark Warrack, who has been a part of Hendrickson’s team on multiple films, was charged with training the mare for her role as Tony. “Mark spent a lot of time getting her acclimated,” says Hendrickson who is quick to praise his crew, “He developed her a lot.” This included teaching Cheetah to execute a 360-degree reining spin and a showy Spanish walk. Both skills are displayed in the movie’s finale when Django and his wife Broomhilda (Kerry Washington) are joyfully reunited.

In a campfire sequence, even though the horses are seen in the background, Tony’s sex is quite obviously male. In that scene and in many of the riding scenes, Cheetah was doubled by Leroy, one of Rusty Hendrickson’s reliable cast horses.

Another horse that appears to be modeled on a historical equine is the white mount of plantation owner Big Daddy (Don Johnson), who is styled to resemble Buffalo Bill Cody. He rides a white horse reminiscent of Cody’s most famous mount, Isham. Rusty Hendrickson’s horse Coconut portrayed the Isham look-alike. Hendrickson originally bought Coconut as a potential Silver for the producers of 2013’s The Lone Ranger, long before that movie began shooting. Although Coconut was not chosen for the starring role, Hendrickson liked the young white horse so much that he bought him for his own string and began developing him for movie work. Wranglers working on films often bring young horses on location to acclimate them to the experience. Such was the case with Coconut, who was learning the ropes on the set of Django Unchained. When Quentin Tarantino saw Coconut, an unusual white Appaloosa without spots, he chose him as Big Daddy’s horse.

One of the film’s most visually effective sequences involves thirty-three mounted and hooded riders, galloping en masse at night. Many of the riders are carrying burning torches. Although the charge ends with a comic punch line, the initial image is frightening. It evokes the incendiary sequence in D.W. Griffith’s 1915 The Birth of a Nation, in which scores of Ku Klux Klansmen ride to avenge the death of a white girl, allegedly killed by a black man. The Klan had yet to be formed in 1858 and the mounted men in Django Unchained are a reference to their forebears, the Regulators. The impressive bit of staging was accomplished by all stunt riders and horses kept in check by offscreen fence panels. According to the American Humane Association, the horses were given twenty-minute rest periods between takes.

Later on in this sequence, the mounted vigilantes circle Dr. Shultz’s wagon and set it on fire. Such “circles of death” with riders circling their enemies have been staples of Westerns since D.W. Griffith first staged such action in his 1912 depiction of Custer’s Last Stand, The Massacre. In Django Unchained, the action is intensified by the wagon blowing up. All the horses in the scene were sprayed with fire retardant even though the stunt horses and riders were at a safe distance from the actual explosion. Fourteen trained falling horses were cued to fall simultaneously in the beautifully choreographed scene, and special effects were added in post-production to make it appear that some of the horses were hit by the explosives.

Although the sequence lasts only a few seconds on film, it took months of preparation to realize. Trained falling horses are in short supply since so few Westerns are made these days, and Hendrickson’s team had only one in their string, the sorrel gelding Wonderbread, owned by trainer Monty Stuart. Hendrickson scoured the country for more, and in the end he and his team developed half of the horses from scratch, going though the step-by-step process of teaching each horse to safely fall.

Reminiscent of a scene in D.W. Griffith’s The Birth Of A Nation, hooded vigilantes light up the night. Although this sequence ends with a laugh, the staging of horses galloping en masse with torch-bearing riders took serious planning.

Known for his often shocking staging of violence, Tarantino did not spare horses from the illusion of bloody mayhem. In the very first sequence, Shultz casually shoots the horse of a slave trader, trapping the villain underneath the corpse. A dummy horse was rigged with fake blood squibs, creating a graphic death that was pure movie magic. “If you’re making a movie, part of the whole aspect is it’s supposed to be make-believe,” reasons Tarantino. “I don’t want to see a real death when I watch a movie, that’s just not what it’s about.”

The intense action in Django Unchained was accomplished without harming a single horse. “We do wild stuff involving horses and it’s very exciting action,” says Tarantino, “but we did it all very safely. You can actually do really amazing, eye-popping things, you just need the time to train them. It’s ultimately safe in real life but it looks gnarly on screen.”

The stuntman playing a villain in this graphic sequence reacts by pulling back on his horse when the squib explodes. Moments later, he takes a planned fall.

The director is quick to praise the American Humane Association for being “a voice for the voiceless.” Tarantino proudly placed AHA’s “No horses were harmed” statement in the first position of the film’s end credits, instead of at the end where it usually appears. “It’s wonderful to have the American Humane sticker,” he explains, “That’s why I put it so early in the credits, to relieve audience members.” Of course, other animals that appear in the film such as dogs, chickens, and a rabbit were either trained performers or, in the case of “dead” animals, either fakes acquired by production or previously mounted specimens by a taxidermist. No animal of any kind was harmed during the making of Django Unchained.

Actor Christoph Waltz, however, took a spill while learning to ride in pre-production, before Hendrickson and his team were hired. Waltz injured his pelvis in the fall and was unable to ride until it healed, hence the use of the wagon in early scenes. Waltz’s riding lessons resumed without incident during the film’s hiatus over the Christmas holidays. After working with Hendrickson and his team, the actor’s confidence was restored. Waltz later quipped that “Riding a horse wasn’t much of a challenge. Falling off was.” His costar, Jamie Foxx, presented him with a gag gift: a saddle rigged with a seatbelt.

No seatbelt was in evidence in Foxx’s most challenging riding sequence in the film. Toward the end of the movie, Django is once again enslaved. While being transported to a sadistic new owner, he outsmarts his captors and liberates three Mandingo, slaves forced to fight to the death for their owners’ amusement. Django also liberates a palomino horse that had been pulling the slave wagon. He hops aboard the palomino and gallops bareback without a bridle back to the plantation where his wife is imprisoned. Tarantino specifically wanted a palomino for the sequence. Already on location in Wyoming, Hendrickson scoured the countryside for a horse that could do the job. He found the mixed-breed palomino, Silky, at Turtle Ranch, home of Robin Wiltshire, an Australian-born trainer who trains the Clydesdales for Budweiser beer commercials. A riding horse, Silky had to be trained to drive a wagon, to handle working around explosions, and to gallop alongside a camera car. The wranglers used him as a utility horse to inure him to set activity, and the sturdy palomino settled nicely into his new job. For the exciting galloping scene, he was fitted with a monofilament bridle. which gave Foxx the ability to steer and stop him, but on film is invisible. The dramatic image of Django on the golden palomino brings to mind that most famous celluloid cowboy hero, Roy Rogers, riding to the rescue on his iconic golden steed, Trigger.

Production placed traction boards under fake snow to create the illusion of riding through snow.

Quentin Tarantino recreated a classic Western image, first seen in silent films, when he staged this visually stunning “circle of death” sequence for Django Unchained.

The Lone Ranger Reimagined

The masked cowboy crime fighter known as The Lone Ranger and his iconic white horse Silver are familiar to baby boomers—and their parents—from the eponymous television series that debuted in 1949 starring Clayton Moore. The popular legend of the masked man, his fiery steed, and Native American sidekick Tonto had already been entertaining radio audiences since 1933. In 1938, a fifteen-episode Lone Ranger serial filmed in Lone Pine, California, featured the famous early equine star Silver King, who may well have been the inspiration for Silver. In 1956, Moore and his television costar Jay Silverheels (Tonto) appeared in a feature-length film version of the legend, with the Glenn Randall-trained Silver showing off his talents as a trick and rearing horse.

Several television movies and a couple feature films followed. The Legend of the Lone Ranger (1981) starred the unknown Klinton Spilsbury (whose high-pitched voice resulted in his being dubbed throughout the film by actor James Keach) in his only film role and Michael Horse as Tonto, with veteran wrangler-trainer Bobby Davenport supplying Silver.

In 2013 The Lone Ranger rode back into movie theaters with an extravagant Disney production directed by Gore Verbinski and starring Armie Hammer as John Reid, aka The Lone Ranger, and Johnny Depp as Tonto, who is a Comanche in this incarnation. The action-packed film follows the basic plotline of its predecessors but incorporates a supernatural element with the villains being such evil spirits that they have caused an imbalance in the natural world. The filmmakers also created a backstory for Tonto who is out to avenge the deaths of his tribe who were murdered by greedy white men when he was just a boy. Showcasing Depp’s flair for eccentric characters, his Tonto brings the film a quirky comedic element. Tonto’s antagonistic relationship with the mysterious white horse who will become Silver is part of the fun.

Silver is introduced in the film as a Spirit Horse, revered for his wisdom by the Comanche. This conceit is a departure from the original concept of Silver. According to the 1938 radio serial episode, The Lone Ranger Finds Silver, The Lone Ranger’s horse, reportedly a chestnut mare named Dusty, is shot dead by the outlaw Butch Cavendish. Carrying the two heroes, Tonto’s brown and white Paint, Scout, is no match for the villain’s speedy mount. The Lone Ranger and Tonto happen upon a storied wild white stallion locked in battle with an enraged buffalo. Outweighed, the valiant horse is critically injured by the buffalo that moves in for the kill. The Lone Ranger shoots the buffalo, saving the stallion’s life. He and Tonto nurse the wounded horse back to health and instead of returning to the wild when cured, the stallion voluntarily submits to The Lone Ranger’s training, not merely out of gratitude but through “some mysterious bond of friendship.” It is Tonto who notices that the stallion’s coat gleams like silver in the sun and Silver is thusly named.

In the 2013 Disney film, Tonto is about to bury John Reid, along with his brother Captain Dan Reid and their posse of Texas rangers who have been murdered by the outlaw Butch Cavendish (William Fichtner) and his gang, when the Spirit Horse appears at John’s grave, carrying his white hat in his teeth, thus designating him for resurrection. Skeptical of John’s valor, Tonto argues with the horse. Finally acquiescing, Tonto mounts up and drags John, who was not really dead, through the desert. When John revives he discovers Tonto talking to the horse in what becomes a running gag. Tonto convinces John to wear a mask made from Dan’s leather vest to disguise himself from the outlaws as they seek revenge, and thus The Lone Ranger is born. The Spirit Horse remains unnamed until the end of the film.

The Spirit Horse carries The Lone Ranger and Tonto on their quest for justice, always showing up in the nick of time to whisk them away from danger. He uses his supernatural abilities to rescue them from a burning barn by appearing on the roof and jumping off the blazing structure through the flames. He also appears in a tree, drinks beer in a lighter moment, and when the heroes find themselves buried up to their necks in sand and attacked by scorpions, the Spirit Horse licks the lethal insects from their faces and devours them. Then, in classic fashion, The Lone Ranger manages to grab the horse’s reins so he can pull him out of the sand.

In the film’s climactic action sequences, The Lone Ranger gallops the Spirit Horse across town rooftops and along the top of a speeding train. At the film’s end, when he is finally named Silver, the horse performs a spectacular rear with The Lone Ranger aboard. It is then that we hear The Long Ranger say the signature catchphrase first made famous on the 1933 radio show, “Hi-Yo-Silver! Away!” Tonto, now mounted on Scout, dryly replies, “Don’t ever say that again.”

Head wrangler Clay Lilley headed a team of wranglers, supervising the stuntmen and horses who performed the demanding action during Comanche and Calvary charges, train-to-horse and horse-to-train transfers, and battle sequences. Aerial equipment was used to assist the stuntmen as they made the exciting transfers, and special sets were built to simulate the rooftops and train that the Spirit Horse gallops upon.

The fire scene was carefully orchestrated and beautifully cut to make it appear as if the horse is jumping off the barn through flames when, in reality, he jumped from a low platform and the flames were nowhere near him. The amazing scene with scorpions was achieved through computer-generated imagery that added the scorpions to the actors’ faces after the fact. The illusion was further created by covering dummy heads with cookies shaped like scorpions that the horse was cued to eat by head trainer Bobby Lovgren.

Lovgren worked with the four white horses it took to portray Silver. The main horse who portrayed the Spirit Horse and performed at liberty in scenes with Johnny Depp is a Quarter Horse gelding coincidentally named Silver. Owned by Clay and his father Jack Lilley’s Movin’ On Livestock company, Silver had appeared in several commercials and smaller parts before stepping into his first starring role. His onscreen chemistry with Depp is a big part of the movie’s charm. Depp has ridden in several of his films and has a true affinity for horses. His ease with his equine costar is apparent in Tonto’s scenes with Silver. “Johnny was very respectful of the horses,” says Lovgren. “I was very impressed with him and how easy he was to work with. He was so conscientious of what we needed and made my life very easy!”

Lovgren spent a month fine-tuning Cloud, a rare white Thoroughbred, who was initially started by Rex Peterson when the film first went into pre-production. Lovgren taught Cloud to “drink beer” from a rubber bottle that was specially vented to give the illusion that the horse was guzzling the brew. Cloud also executed all the jumps in the sequences and is the horse who did the rooftop and train-top running scenes. Lovgren also perfected the horse’s rear, so essential to The Lone Ranger’s trademark. It is Cloud who performs the spectacular stunt as Silver in two scenes.

The two other Silvers were Caspar, a white Paint and the Quarter Horse Leroy whom Armie Hammer rode in much of the film. According to Lovgren, the handsome actor has a natural aptitude for horsemanship and spent a lot of time perfecting his abilities to portray the masked man. Hammer had previously worked with the trainer on the 2012 film Mirror, Mirror, in which he rode Lovgren’s beloved veteran movie horse Houdini.

Houdini, whose credits include Seabiscuit and 2005’s The Legend of Zorro, has a cameo in The Lone Ranger as a striking black horse the heroes follow through the desert as they track the villains. Houdini, a natural buckskin, was dyed black for the film and was directed by Lovgren to walk at liberty on top of a ridge through the sand for quite a distance. It was the most challenging sequence in the film for Lovgren, who walked off-camera at the base of the ridge in knee-deep sand. “I was very glad I had Houdini for the scene because he had had so much experience,” says Lovgren. The bond between the trainer and his horse must be very strong for a horse to work at liberty in such conditions.

At the end of the sequence, the black horse suddenly falls over, dead, in a macabre gag that sets up a joke when The Lone Ranger tries in vain to get directions on where to go next from the immobile animal. A fake horse was used for the fall and subsequent scene.

All the animal action in The Lone Ranger was monitored by the American Humane Association, which gives it an outstanding rating. Hi-Yo-Silver!

As the title character in The Lone Ranger, Armie Hammer strikes the classic pose aboard Silver, portrayed here by Cloud.

Tonto (Johnny Depp) faces off against the opinionated Silver.