The first human traces on Antigua are believed to date back to the Stone Age Siboney people who migrated from South America to settle on the island around 2400 BC. They were followed by the seafaring Arawak-speaking farmers and fishermen around the first century AD, who settled in villages around the coast and also developed their skill in pottery making.

Early times

The Arawaks were the first well-documented group of Antiguans. They were a peaceful people, catching fish and growing corn and cassava, and soon introduced an agricultural system into the islands of Antigua and Barbuda. Crops were developed including sweet potatoes, chillies, guava, tobacco, cotton and the famous ‘black’ pineapple. Their tribes were ruled by a chief or cacique and their religious leader or shaman was held in great respect. From around AD 600 they suffered continuous raids from another tribe, the Caribs, a more warlike race from the Amazon region with superior weaponry and seafaring prowess.

By AD 1100 the Caribs had finally conquered all the Arawak lands and reigned supreme over the Leeward Islands. They did not, however, settle on the island of Antigua but used it as a base for gathering provisions.

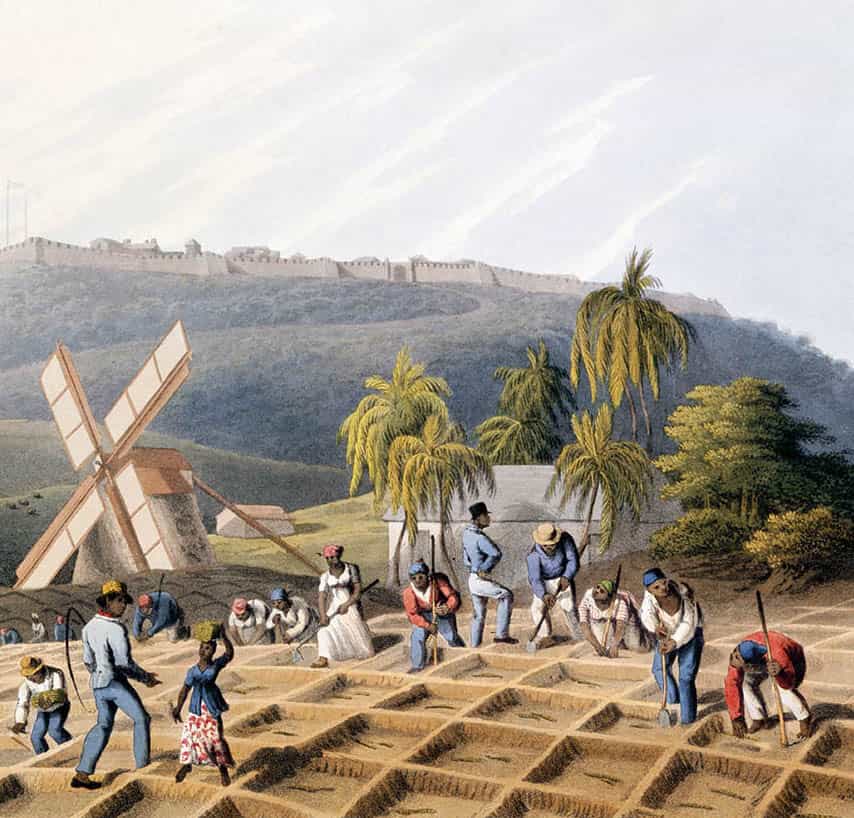

Slaves planting sugar cane, Antigua (1823 illustration)

Getty Images

European colonisation

In 1493, on his second voyage, Christopher Columbus sighted the island of Antigua and named it Santa Maria de la Antigua, after the miracle-working saint of Seville in Spain. Early settlement, however, was discouraged by insufficient water on the island and by Carib raids. Columbus was followed by the English, French and Dutch, all of whom fought for dominion over the islands. In 1632 Antigua was colonised by a British expedition from St Kitts, under Sir Thomas Warner and the first settlement was established at Parham, which became the home of the early British governors. Antigua remained under the rule of the English with only a brief takeover by the French in 1666.

Once returned to the crown, with the Peace of Breda in 1667, the island became an important colonial naval base, with an arsenal built at English Harbour in the south of the island where the British fleet was stationed. Sugar was introduced in the 1650s and in 1674 Christopher Codrington established the first sugar estate at Betty’s Hope, which remained in the family for almost 200 years. In 1680 he leased the island of Barbuda, where he raised livestock and grew agricultural produce with slave labour for the British colonists on Antigua. Codrington and his contemporaries brought slaves from Africa’s west coast to work the plantations under brutal conditions. Meanwhile Antigua was deforested to make way for the plantations, which were devoted solely to the production of sugar. The number of slaves on Antigua peaked at 37,500 in the 1770s, but thousands more died during the crossing.

Decadent landowners

On the same island, but worlds apart, life for the white-planter classes suffered more from decadence than want. John Luffman writes in A Brief Account of the Island of Antigua (1789) that ‘men sport several dishes at their tables, drink claret, keep mulato mistresses, and indulge in every foolish extravagance’.

In 1784 Horatio Nelson arrived as captain of the HMS Boreas, which was based in English Harbour – Antigua was used as the headquarters of the British Royal Navy Caribbean fleet. The harbour provided a sheltered and well-protected deep water port. Known as the ‘gateway to the Caribbean’ the formidable base ensured Britain’s enemies gave the whole island a wide berth. Nelson’s time as commander of the fleet between 1784 and 1787 is commemorated at Nelson’s Dockyard. Nelson spent almost all of his time in the cramped quarters of his ship as he had a distinct dislike of the island calling it a ‘dreadful hole’.

In 1807 the slave trade was finally abolished but slavery on the plantations continued. With all the others in the British Empire, Antiguan slaves were emancipated in 1834 and some 29,000 slaves were freed. Many, however, remained economically dependent on their plantation owners. In fact, fair rights for workers remained a problem until the 1940s. Further problems occurred on Antigua during the 1830s and 1840s when the island was hit by earthquakes, hurricanes, drought and yellow fever. To compound all this, a fire destroyed most of the capital, St John’s. By the 1850s the sugar industry was in crisis with further hurricanes and drought, together with reduced commodity prices. The industry continued to wane and in just a century no more sugar was produced in Antigua, the last plantation closing in 1971.

Continuing enslavement

The voice of the enslaved is poignantly recounted in The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave, Related by Herself. This narrative bears witness to the ills of the age as experienced by a woman in St John’s during the early 18th century. Emancipation came in 1834, but not before a series of slave rebellions had ensured that the days of the regime were numbered. The most famous revolt occurred in 1736 and, if successful, would have altered the course of Caribbean history. Given the sugar monopoly, former slaves, once freed, had little choice of alternative work, and most remained on the plantations. For the planters, the cost of wage labour turned out to be lower than the upkeep of the slave system.

Until the development of tourism in the past few decades, Antiguans struggled for prosperity, eking out a poor agricultural existence and in 1938 the Moyne Commission for the West Indies recorded Antigua among the most impoverished of the islands. Poor labour conditions persisted until 1939 when a member of a royal commission urged the formation of a trade union movement. A short-term boost came to the economy during World War II when the US built two military bases, creating some local employment.

Vere Cornwall Bird, first Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda

Getty Images

Political development

The Antigua Trades and Labour Union (ATLU), formed in 1939, was a direct response to the miserable working conditions. It was created under the leadership of Vere Cornwall Bird (1910–1999) who had been an officer in the Salvation Army for two years, while pursuing his interests in trade unionism and politics. On seeing how the landowners were treating the local black Antiguans and Barbudans, he decided to leave the Salvation Army to follow a political career.

Under Bird’s strong leadership the labour movement – now the Antigua Labour Party (ALP) – gained momentum culminating in his victory at the first ever local elections in 1946, winning a seat in the legislature and appointed a member of the Executive Council. An imposing figure – he stood at 7ft (213cm) – he was a brilliant orator, wowed the masses and became the dominant political and economic force on the island. He led the Antiguan people into the post-colonial era with rousing rhetoric but made it clear in the 1950s and 1960s that the island still operated as two separate societies, the whites and ‘the rest’.

History of Redonda

The uninhabited island of Redonda became part of Antigua and Barbuda in 1967, despite it lying some 35 miles (56km) southwest of Antigua. Home to a large number of seabirds, the resultant deposit of guano became a viable commercial product in the mid-19th century before the advent of artificial fertilisers. From the 1860s until World War I a few hardy souls – a population of 120 were living there in 1901 – made a good living collecting and shipping bird droppings to Britain.

Despite being annexed by the British, Matthew Shiell, an Irishman from Montserrat, allegedly claimed the island as a kingdom in 1865, crowning his son, an author, the first king. The title has since passed to a succession of non-resident literary types who have created honorary peers including poet Dylan Thomas, actor Vincent Price and musician Sting.

Antigua, together with Barbuda and Redonda as dependencies, became the first East Caribbean island to be appointed an Associated State of the Commonwealth in 1967. The national flag comprising the sun rising on a black background with bands of blue, then white, narrowing to a ‘V’ for victory, bordered by red, was elaborately designed for this occasion. The sun depicts the dawn of a new era; red, symbolises the people’s dynamism; black belongs to the island’s soil and African heritage; while gold, white and blue signal the soul of tourist heritage – the sun, sand and sea.

Bird, radical in his younger days, had been shifting to the right, and in the face of severe social unrest that forced a split in the ALP in 1967 and rioting in 1968, the ALP lost its tight hold of Antigua and Barbuda politics. Out of the split, the Antigua Workers Union was formed and later the Progressive Labour Movement. In 1971 the so-called ‘Broom Election’ swept the Progressive Labour Movement and George Walter to victory, clearing out the Bird administration. But just five years later, in 1981, a 95 percent turnout returned V. C. Bird or ‘Papa’ Bird as he was known, as premier, and Antigua and Barbuda to independence. Queen Elizabeth II remains the Head of State for this constitutional monarchy to this day, and is represented by a Governor General. In June 1981 Antigua and Barbuda joined the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), which promotes economic co-operation, trade and joint action on major common problems. Since the 1960s the two islands have gradually abandoned their agricultural economy and turned their sights on becoming a tourist paradise.

In 1989 The Barbuda People’s Movement gained all nine seats on the Barbuda Council and campaigned vociferously for greater autonomy. It did not, however, gain enough votes to qualify for a seat in the national government.

The Brute Force Steel Band of Antigua in 1965

Getty Images

Independent nation

In 1992 the three opposition parties merged to form the United Progressive Party in an attempt to overthrow the Bird dynasty and the Antigua Labour Party. V.C. Bird, however, led the new state until 1994, when his son Lester B. Bird took over the reins. As times changed, the lines of power and money became more interwoven within the Bird clan and their networks of associates. Flows of large investments from abroad, without signs of obvious gain for the people of Antigua, and an embarrassing series of offshore financial scandals, lowered the tone of government business.

The colonial schemes of the past are more than matched by today’s intriguing political scene, which has thrown up corruption and money laundering matters by the bucketful. The Bird family, masterminded by the late V.C. Bird, held a stern grip on the country’s political, economic and media matters for over five decades. In 1997 a series of financial scandals and the collapse of a major Antiguan bank provoked international condemnation of the islands’ financial sector. In 2004 the United Progressive Party, led by Baldwin Spencer won the general election defeating the Antigua Labour Party and ending Lester B. Bird’s 10-year reign.

Tourism increased its monopoly of the economy. With huge investment from the US and more recently China, luxury resorts attracted more and more visitors. However, fraud and financial scandal were still rife. In 2009 Sir Allen Stanford, a financier and was arrested by the FBI for fraud, receiving a 110-year prison sentence. As Antigua’s second largest employer after the government, his demise resulted in massive job losses.

Power was returned to the Antigua Labour Party under the leadership of Gaston Browne in the election of 2014 and again in 2018. Controversy has plagued Browne’s career with his involvement with overseas investment for mega-resort developments, allegations of corruption and in his complex relationship with Barbuda. The Land Act of 2007 upheld that all land in Barbuda was held freely and in common and Barbudans had a right to self-determination and to develop their land for sustainable, small-scale tourism. Under Gaston Browne the Land Act was repealed in 2015, and since Hurricane Irma in 2017 the situation has been exacerbated, resulting in a legal battle for the rights of the Barbudan people who are anxious to retain their individuality.

Sir Rodney Williams, 4th Governor General of Antigua and Barbuda, meeting Queen Elizabeth

Getty Images